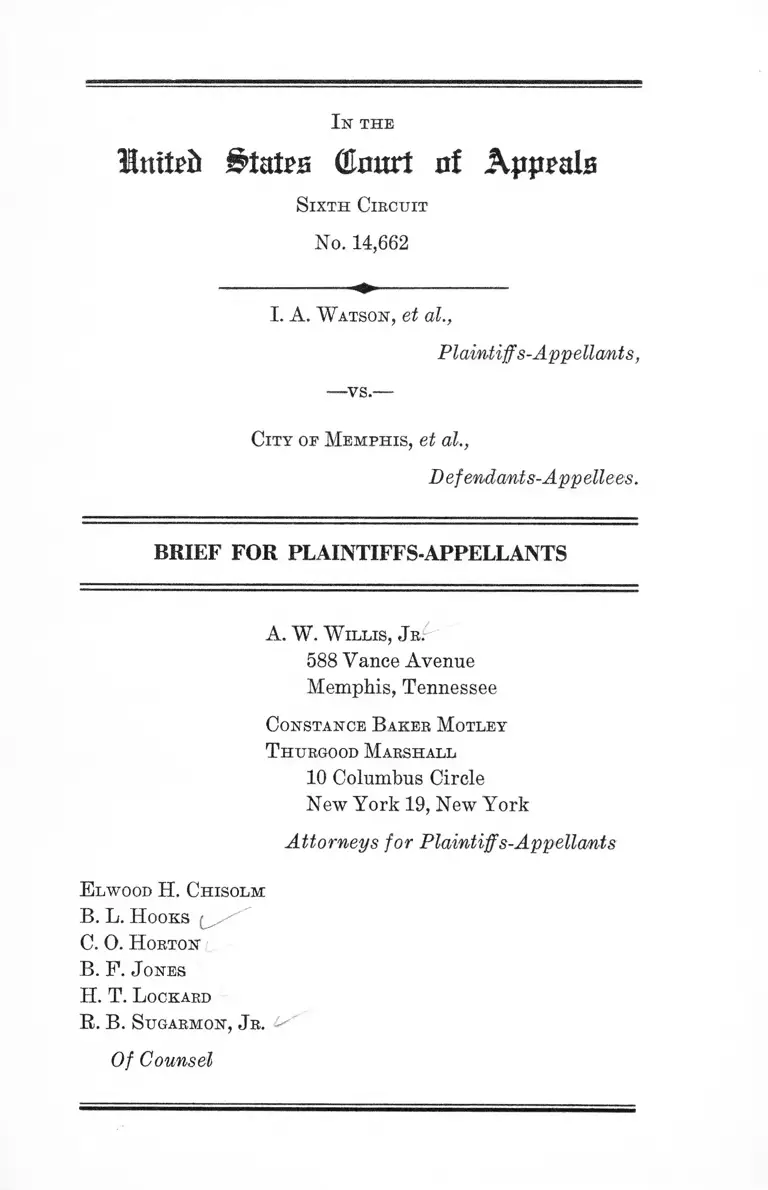

Watson v. City of Memphis Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Watson v. City of Memphis Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1961. 60f7f9bb-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b652e364-42f4-4060-b716-5fd5661ff9d0/watson-v-city-of-memphis-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

TUnxUh States GJmtri of Appeals

S ixth Circuit

No. 14,662

I. A. W atson, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

—vs.—

City of Memphis, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

A . W . W illis, J r .

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Constance B aker M otley

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiff s-Appellants

E lwood H. Chisolm

B. L. H ooks

C. O. H orton

B. F. J ones

H. T. L ockard

R. B. Sugarmon, Jr.

Of Counsel

Statement of Questions Involved

1. Whether, considering the facts established, as plaintiffs

alleged and the District Court substantially found, that

defendants maintain and operate a racially segregated

public recreational system, plaintiffs are entitled to a

permanent injunction and declaration as prayed for in

their complaint.

The District Court answered “ No.”

Plaintiffs-appellants contend that the answer should

be “Yes.”

2. Whether the decision in the Second School Desegrega

tion Case, Broivn v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294

(1955), which contemplates allowing a delay in the

desegregation of public elementary and secondary

schools, is applicable in an action involving public rec

reational facilities.

The District Court answered “ Yes.”

Plaintiffs-appellants contend that the answer should

be “ No.”

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of Questions Involved.... ..... ............. .............. a

Statement of Facts ............................................................ 1

A rgument :

I. Whether, considering the facts established, as

plaintiffs alleged and the District Court sub

stantially found, that defendants-appellees

maintain and operate a racially segregated

public recreational system, plaintiffs are en

titled to a permanent injunction and declara

tion as prayed for in their complaint ........... 6

II. Whether the decision in the Second School

Desegregation Case, Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), which contem

plates allowing a delay in the desegregation

of public elementary and secondary schools,

is applicable in an action involving public

recreational facilities ........................................ 9

R elief ............................. ..................... ................................ ....... . 13

T able of Cases

Bailey v. Smith, Civ. No. W649, D. Ivan., June 30, 1954 7

Booker v. State of Tennessee Board of Education, 240

F. 2d 689, 692-693 (6th Cir. 1957) ..... .......... ...... 7,10,11

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ....a, 5, 9,

10,11,12

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81 (1917) ............... 9

i i

Charlotte Park and Recreation Commission v. Bar

ringer, 242 N. C. 311, 88 S. E. 2d 114 (1955), cert,

denied, sub nom. Beeper v. Charlotte Park and Recre

ation Commission, 350 U. S. 983 (1956) ....................... 9

City of Miami v. Prymus, 288 F. 2d 465 (5th Cir. 1961) 7

City of Montgomery v. Gilmore, 277 F. 2d 364, 369-370

(5th Cir. 1960) .............................. ..... ............................. 10

City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830 (5th Cir.

1956) ............................ ........ ...... ...................................... 6-7

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d

853, at 857-858 ................ ......... ........................................ 8

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 16 (1958) ........................... 9

Cummings v. City of Charleston, 288 F. 2d 817 (4th Cir.

1961) ................. .......................................................... 7,10,11

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180,

184-185 (6th Cir. 1955) ..................................................... 10

Draper v. City of St. Louis, 92 F. Supp. 546 (E. D. Mo.

1950), appeal dism’d 186 F. 2d 307 (8th Cir. 1950) .... 7

Fayson v. Beard, 134 F. Supp. 379 (E. D. Tex. 1955) .... 7

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U. S.

413 (1956) ....................................................... 10-11

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 176 F. Supp. 776 (M. D.

Ala. 1959), afPd 277 F. 2d 364 (5th Cir. 1960) ........... 7

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, Civ. No. 436-J, S. D.

Fla., December 10, 1960 (5 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1145,

1146) ........................................ 7,10

Harris v. Daytona Beach, 105 F. Supp. 572 (S. D. Fla.

1952)

PAGE

7-8

Ill

Hayes v. Crutcher, 108 F. Supp. 582 (M. D. Tenn. 1952),

vacated 137 F. Supp. 853 (M. D. Tenn. 1956) ........... 7

Holly v. City of Portsmouth, Va., 150 F. Supp. 6 (E. D.

Va. 1957) ......... ................................................................ 7

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 124 F. Supp. 290, aff’d 223 F.

2d 93 (5th Cir. 1955), rev’d 350 U. S. 879 (1955) ....... 6

Jackson v. McDonald, Civ. No. 3172, E. D. Tex., July 30,

1956, appeal dism’d sub nom. Lamor State College of

Technology v. Jackson, No. 16,443, 5th Cir., May 10,

1957 ....................................................... .................. ......... 7

Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville, Civ.

No. 2094, M. D. Tenn., Sept. 6, 1957 (2 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 970, 973), 159 F. Supp. 272, 274, 278, 279 (M. D.

Tenn. 1958), aff’d 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959), cert,

denied 361 U. S. 924 (1959) ......... ...... ............ ...... ...... 7

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S. D. W. Va.

1948) ................................................. ................ ............... 7

Leeper v. Charlotte Park and Recreation Commission,

Sup. Ct., 26 Jud. Disk, Mecklenburg Co., N. C., Feb.

4, 1957 (2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 411-412) .... ............... . 10

Lonesome v. Maxwell, 123 F. Supp. 193 (D. Md. 1954),

rev’d sub nom. Dawson v. Mayor and City Council

of Baltimore City, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d

350 L. S. 877 (1955) ..... .................................................6,11

Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 679 (S. D. Cal. 1944) .... 7

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637

(1950) .............. ........... ...................... ................. ............. 8

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350

U. S. 877, aff’g 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955) ....10,11,12

Moorhead v. City of Fort Lauderdale, 152 F. Supp. 131

(S. D. Fla. 1957), aff’d 248 F. 2d 544 (5th Cir. 1957) 7

PAGE

IV

PAGE

Shipp v. White, Civ. No. 2789, N. D. Tex., Feb. 11, 1960 7

Simkins v. City of Greensboro, 149 F. Supp. 562 (M. D.

N. C. 1957), aff’d 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir. 1957) ........... 7

Sweeney v. City of Louisville, 102 F. Supp. 525 (W. D.

Ky. 1951), aff’d sub nom. Muir v. Louisville Park

Theatrical Assn., 202 F. 2d 275 (6th Cir. 1953),

Vacated 347 U. S. 971 (1954) ....................................... 6

Tate v. Department of Conservation and Development,

133 F. Supp. 53 (E. D. Va. 1955), aff’d 231 F. 2d 615

(4th Cir. 1956), aff’d 352 U. S. 838 (1956) ............... 6

Ward v. City of Miami, Fla., 151 F. Supp. 593 (S. D.

Fla. 1957) ........... .................. ............................................ 7

Williams v. Kansas City, 104 F. Supp. 848 (W. D. Mo.

1952), aff’d 205 F. 2d 47 (8th Cir. 1953), cert, denied

346 U. S. 826 (1953) ........... ............... ........................... 8,9

S tatutes and Constitutional P rovision

Constitution of the United States

Fourteenth Amendment ........................................ .... 1, 6

Civil Rights Law

28 U. S. C. §1981.......................................................... 1

Other A uthorities

McKay, “ Segregation and Public Recreation” , 40 Va. L.

Rev. 697, 724 (1954) .................... ................................... 12

Nicholson, “ The Legal Standing of the South’s School

Resistance Proposals,” 7 S. C. L. Q. 1, 59 (1954) ....... 7

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF APPENDIX

PAGE

Docket Entries ......................................................... la

Complaint ................................................... 2a

Answer .............. 10a

Excerpts From Testimony on T ria l.... ....... .................. 15a

By Plaintiffs’ Witnesses:

Dr. William 0. Speight, Jr................ 15a

Dr. A. E. H orne....................................... 18a

Curtis King, Jr............... 20a

Melvin Kobertson ................................... 21a

Joseph Willie Lane, Jr............................................. 23a

Dr. I. A. Watson, Jr................................................. 28a

Alma Bonds ............................................... 30a

Harold Gholston ...................................... 32a

Alfred Haynes, Jr......................................... 34a

By Defendants’ Witnesses:

Harry Pierotti ..................................................... 37a

Harold S. Lewis ........................... 72a

James C. Macdonald ........ 100a

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of L a w ........ .......... 105a

Judgment 118a

Statement of Facts

This appeal is from a final judgment entered June 20,

1961, whereby the United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee, Western Division, per

Hon. Marion S. Boyd, Chief Judge, which denied plaintiffs’

application for a permanent injunction restraining the

Memphis Park Commission and others from operating and

maintaining certain public recreational facilities on a ra

cially segregated basis and which approved a plan pro

posed by defendants for a gradual desegregation thereof

(App. 118a-121a).

The proceedings in the court below began May 13, 1960,

when plaintiff Negro citizens of Memphis, Tennessee, filed

their complaint as a class action for declaratory and in

junctive relief against defendant officers and agencies or

departments of the City of Memphis. The gravamen of

the complaint is that defendants operate and enforce the

maintenance of a system of public recreational facilities

on a racially segregated basis; that plaintiffs and other

Negro citizens have attempted to use certain facilities

which defendants have restricted to use by white persons

and have been barred therefrom on account of their race

or color; and that defendants’ maintenance and enforce

ment of such system violates rights guaranteed under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and the Civil

Eights Law, 28 U. S. C. §1981 (App. 2a-9a).

On July 1, 1960, defendants filed their answer (App. 10a-

14a) which, aside from presenting procedural and juris

dictional objections not material to this appeal, did not

deny the operation and enforcement of segregated public

recreational facilities. However, they pleaded as justifica

tion that the quantum and quality of recreational facilities

provided for Negro citizens is equal to those provided for

2

white citizens; that “problems” are likely to flow from

court-ordered desegregation; that certain park areas were

acquired by wills or deeds which restrict, condition, and

limit such areas to use by white persons; that “ defendants

have the duty of exercising the Police powers vested in

such a way as to prevent riots, violence, and disharmony

of all kinds among the races; that historically and tra

ditionally, riots and violence have frequently occurred in

areas where races are mixed in large numbers in places

of amusement. Therefore, these defendants, in discharging

their duties as public officers and in exercising the Police

powers vested in them, have prevented the assembly of

mixed groups in large numbers in some of the parks in

the City of Memphis in order to maintain harmony be

tween the races and in order to prevent violence, bloodshed

an civil commotion” (App. 12a).

Trial on the merits was held on June 14-15, 1961. The

facts there established, as plaintiffs alleged and the Dis

trict Court substantially found, were that the City of

Memphis through its Park Commission operates and main

tains a public recreational system on a racially segregated

basis (App. 88a, 105a, 106a-107a-108a); that this system

consists of 131 parks and facilities, of which 108 are

“developed” and 25 are “ undeveloped” ; that 25 of the

developed facilities are restricted to Negroes, 25 are open

to both races and Negroes are barred from 58; that the

facilities operated on a racially segregated basis include

40 “neighborhood” playgrounds for white persons and 21

for Negroes, 8 white and 4 Negro community centers, 5

white and 5 Negro swimming pools, 5 white and 2 Negro

golf courses, plus 2 “ city-wide” white stadiums (PI. Ex.

3, 4, 5, 6; App. 44a, 46a, 73a, 77a, 78a, 80a, 81a, 91a-92a) J

1 The Park Commission also operates 56 playgrounds and facilities

on property not entirely controlled by it ; 30 of these are designated

and maintained as “white” while the rest are restricted to Negroes

(PI. Ex. 5; App. 44a, 73a, 80a-81a, 91a-92a).

3

that it has been the policy of the Park Commission over

the years to designate parks and playgrounds as “ white”

or “ Negro” according to the racial character of the neigh

borhood and, pursuant to this policy, six facilities will be

changed from white to Negro use “ in the near future”

(App. 78a-79a) and, accordingly, e.g., the racial ratio for

community centers will be changed to 7 white and 4 Negro

and that for swimming pools to 4 white and 6 Negro (App.

80a, 81a); that plaintiffs and other Negroes attempted to

enjoy or use certain white facilities and were refused ad

mission thereto or ousted therefrom because of their race

(App. 15a, 17a, 18a, 19a, 20a-21a, 23a, 26a, 28a, 29a, 30a,

32a, 35a); and that, pursuant to instructions issued by the

Park Commission with respect to Negroes who do not

depart from a white facility when denied admission (App.

88a-89a), agents or employees of the Park Commission

have caused plaintiffs and others to be arrested (App.

22a) or chased off by the police (App. 30a).

Evidence adduced at the trial tended also to support,

as defendants pleaded in justification and the trial court

invariably found (App. 107a, 108a-109a, 110a-113a), that

the Park Commission recently removed the racial restric

tions voluntarily, at three “ city-wide” facilities (Overton

Park Zoo, the Art Gallery in Overton Park and the Mc-

Kellar Lake Boat Dock) as a part of the Commission’s

gradual desegregation plan (App. 47a, 50a); that the Com

mission’s plan proposes to desegregate Fairgrounds Amuse

ment Park, at the end of 1961 and, beginning in January,

1962, to desegregate all seven public golf courses on a

three year stair-step schedule (Def. Ex. 3; App. 47a-48a,

50a, 51a); that the Commission plans to desegregate all

public recreational facilities “ eventually” and does not

have any idea when that will be done (App. 65a, 66a, 98a-

99a); that the Commission’s stair-step plan for desegre

gating the golf courses and Fairgrounds Amusement Park

4

was formulated after discussion with the Memphis Police

authorities and a Negro minister (App. 54a, 65a, 75a,

101a), study of nonsegregated golf courses and a zoo in

Atlanta, Dallas, Nashville and New Orleans (App. 75a,

92a-94a), consideration of the “peculiar” geographical

location of the City and characteristics of the adjacent

counties in Arkansas and Mississippi (App. 56a, 63a, 64a),

discovery of a reverter clause in the conveyance of Pink

Palace, conditioned on the use of the property by persons

other than white people,2 and realization of the possibility

of similar provisions in other grants of land for park

purposes (App. 36a, 42a, 45a, 69a); that officers of the

Park Commission and the local chief of police were of

the opinion that any desegregation in public recreation,

other than that covering golf courses and the Fairgrounds

in the Commission’s three year stair-step plan, would

produce turmoil, confusion and probably bloodshed in the

City of Memphis (App. 49a, 54a, 74a, 102a).3

Upon the pleadings and evidence summarized above, the

District Court on June 20, 1961, entered the judgment from

which this appeal is taken (App. 118a, et seq.). Thereafter,

on June 27, the Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

were filed (App. 105a-117a), the meat of which is given in

the following paragraph which the District Court cap

tioned “ CONCLUSIONS OF FACT AND LAW ” (App.

117a):

Defendants have shown by a preponderance of the

evidence that additional time is necessary to accom

2 Pink Palace Museum has been open to Negroes on a one-day-

a-week basis (App. 20a-21a, 59a) without objection from the cor

porate grantor or its successors (App. 58a, 59a-60a).

3 No racial confusion, turmoil or violence has occurred on the

recreational facilities which are open to both races (App. 61a-62a,

96a) and Memphis has not had the “ agitators” that have been in

other places (App. 103a).

5

plish full desegregation of all facilities operated by

the Memphis Park Commission, and defendants have

further shown that their plan and program for gradual

desegregation is necessary, in the public interest, and

is consistent with good faith implementation of the

governing constitutional principles as announced in

Brown vs. Board of Education [349 U. S. 294 (1955)],

taking into account all of the local conditions and

problems hereinabove set out; and the Court has con

cluded, in the exercise of its discretion, that the prayer

for declaratory judgment and injunctive relief should

be denied.

On this appeal, plaintiffs-appellants contend that sub

stantial errors were made by the court below in :

1. Holding that plaintiffs are not entitled to the in

junctive and declaratory relief prayed for in their com

plaint; and 2 *

2. Holding that the decision in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), which contemplates allowing a

delay in the desegregation of public elementary and second

ary schools where certain conditions exist, is applicable in

an action involving public recreational facilities.

6

ARGUMENT

I.

Whether, considering the facts established, as plain

tiffs alleged and the District Court substantially found,

that defendants-appellees maintain and operate a racially

segregated public recreational system, plaintiffs are en

titled to a permanent injunction and declaration as

prayed for in their complaint.

The District Court answered “ No.”

Plaintiffs-appellants contend that the answer should

be “ Yes.”

Under the record in this case there is beyond a doubt

racial segregation decreed and enforced by defendants in

their official capacity against plaintiffs and others sim

ilarly situated, solely because of race or color, in the en

joyment or use of recreational facilities maintained and

operated by public funds. See Statement of Facts, supra,

pp. 2-3. Neither defendants’ evidence nor the District

Court’s findings gainsay this conclusion. The record, there

fore, clearly establishes that plaintiffs and others in like

situation in the City of Memphis have been deprived of their

rights under the Fourteenth Amendment : this is now

settled beyond legitimate debate.4

4 See, Sweeney v. City of Louisville, 102 F. Supp. 525 (W. D. Ky.

1951), aff’d sub nom. Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 202

F. 2d 275 (6th Cir. 1953), Vacated 347 U. S. 971 (1954) ; Lonesome

V. Maxwell, 123 F. Supp. 193 (D. Md. 1954), rev’d sub nom. Dawson

v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th

Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877 (1955) ; Holmes v. City of Atlanta,

124 F. Supp. 290, aff’d 223 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1955), rev’d 350 U. S.

879 (1955); Tate v. Department of Conservation and Development,

133 F. Supp. 53 (E. D. Va. 1955), aff’d 231 F. 2d 615 (4th Cir.

1956), aff’d 352 U. S. 838 (1956) ; City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup,

7

Moreover, the public policy enforced by defendants in

the use of public facilities cannot constitutionally be bot

tomed on the existence of some facilities which are open

to both races on a nonsegregated basis at the same time

that other facilities are only open to Negro and white

citizens on a segregated basis: this, too, is well-settled.5

So, however blameless defendants believe they are, and

however proper defendants may consider the present policy

and the course laid before the District Court for the future,

none of this can override the law on the subject.6

238 F. 2d 830 (5th Cir. 1956) ; Simkins v. City of Greensboro, 149

F. Supp. 562 (M. D. N. C. 1957), aff’d 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir.

1957) ; Moorhead v. City of Fort Lauderdale, 152 F. Supp. 131

(S. D. Fla. 1957), aff’d 248 F. 2d 544 (5th Cir. 1957) ; Gilmore v.

City of Montgomery, 176 F. Supp. 776 (M. D. Ala. 1959), aff’d 277

F. 2d 364 (5th Cir. 1960); City of Miami v. Prymus, 288 F. 2d 465

(5th Cir. 1961); Cummings v. City of Charleston, 288 F. 2d 817

(4th Cir. 1961). See also Hayes v. Crutcher, 108 F. Supp. 582

(M. D. Tenn. 1952), vacated 137 F. Supp. 853 (M. D. Tenn. 1956) ;

Fayson v. Beard, 134 F. Supp. 379 (B. D. Tex. 1955) ; Holly v.

City of Portsmouth, Va., 150 F. Supp. 6 (E. D. Va. 1957); Ward

v. City of Miami, Fla., 151 F. Supp. 593 (S. D. Fla. 1957) ; Bailey

v. Smith, Civ. No. W649, D. Kan., June 30, 1954; Hampton v. City

of Jacksonville, Civ. No. 436-J, S. D. Fla., December 10, 1960.

5 Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville, Civ. No. 2094,

M. D. Tenn., Sept. 6. 1957 (2 Race Rel. L, Rep. 970, 973), 159 F.

Supp. 272, 274, 278, 279 (M. D. Tenn. 1958), aff’d 270 F. 2d 209

(6th Cir. 1959), cert, denied 361 U. S. 924 (1959); Jackson v. Mc

Donald, Civ. No. 3172, E. D. Tex., July 30, 1956, appeal dism’d sub

nom. Lamor State College of Technology v. Jackson, No. 16,443, 5th

Cir., May 10, 1957; Shipp v. White, Civ. No. 2789, N. D. Tex.,

Feb. 11, 1960. See Nicholson, “ The Legal Standing of the South’s

School Resistance Proposals,” 7 S. C. L. Q. 1, 59 (1954). Cf.

Booker v. State of Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d 689

692-693 (6th Cir. 1957).

6 This, indeed, was true with respect to public recreation when

“ separate but equal” was not the rubric of a dead era. See, e.g.,

Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 679 (S. D. Cal. 1944); Lawrence

v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S. D. W. Va. 1948) ; Draper v. City

of St. Louis, 92 F. Supp. 546 (E. D. Mo. 1950), appeal dism’d 186

F. 2d 307 (8th Cir. 1950) ; Harris v. Daytona Beach, 105 F. Supp.

8

Therefore plaintiffs say, as Judge Allen, speaking for

this Court said in Clemons v. Board of Education of Hills

boro, 228 F. 2d 853, at 857-858:

It follows that the judgment of the District Court

is contrary to the rules of equity and constitutes an

improvident exercise of judicial power. It is generally

held that the trial court abuses its discretion when

it fails or refuses properly to apply the law to con

ceded or undisputed facts. Union Tool Co. v. Wilson,

259 U. S. 107, 112, 42 S. Ct. 427, 66 L. Ed. 848. Mis

application of the law to the facts is in itself an

abuse of discretion. Hanover Star Milling Co. v. Allen

& Wheeler Co., 7 Cir., 208 F. 513, 523. Such abuse of

discretion requires reversal. Bowles v. Simon, 7 Cir.,

145 F. 2d 334. Here the allegations of the complaint

were sufficient, the evidence was undisputed, and it

was undisputed that defendants ignored the statutory

and constitutional rights of these plaintiffs.

572 (S. D. Fla. 1952); Williams v. Kansas City, 104 F. Supp. 848

(W. D. Mo. 1952), aff’d 205 F. 2d 47 (8th Cir. 1953), cert, denied

346 U. S. 826 (1953). Cf. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

U. S. 637 (1950), involving a situation not without analogy in this

context.

9

Whether the decision in the Second School Desegrega

tion Case, Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294

(1 9 5 5 ) , which contemplates allowing a delay in the

desegregation of public elementary and secondary

schools, is applicable in an action involving public rec

reational facilities.

The District Court answered “ Yes.”

Plaintiffs-appellants contend that the answer should

be “ No.”

Faced with facts which spell segregation in the operation

of the system of public recreation, defendants produced a

plan for gradually desegregating the Fairgrounds Amuse

ment Park and the seven public golf courses over a three

year span, beginning at the end of 1961, and for “ even

tually” desegregating all facilities at some unannounced

times, apparently to be determined when the possibility of

tumult or confusion ceases to exist7 and the legality of the

reverter provision in the Pink Palace deed has been

litigated.8 See Statement of Facts, supra, pp. 3-4. The

7 Violence and tumult, actual or imagined, have been advanced

with equal vehemence in opposition to ending or delaying segre

gation in housing, educational facilities and public recreation; but

preservation of the public peace cannot be accomplished by state

action which denies personal and present rights created or pro

tected by the Federal Constitution. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S.

60, 81 (1917); Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 16 (1958); Williams

v. Kansas City, supra, n. 6, 104 F. Supp. at 852.

8 A similar provision has been held to be a valid determinable

fee with a possibility of reverter in the grantor. Charlotte Park and

Recreation Commission v. Barringer, 242 N. C. 311, 88 S. E. 2d 114

(1955), cert, denied, sub nom. Beeper v. Charlotte Park and Recre

ation Commission, 350 U. S. 983 (1956). However, thereafter, the

Recreation Commission was “perpetually restrained and enjoined

from depriving plaintiffs, or either of them, or other Negroes simi

larly situated because of their race from the right and privilege of

admission to and use of the Bonnie Brae Golf Course [which had

II.

10

plan and the considerations which underlie it were ap

proved by the District Court, without modification save for

submission of a proper plan for integration of playgrounds

and community centers within six months (App. 120a).

Plaintiffs contend that the law permits of no such delay

in the protection of their constitutional rights to non-

segregated public recreational facilities.

The District Court predicated approval of the plan, as

amended, on the second decision in the School Segregation

Cases, Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955)

(App. 114a, 115a, 116a, 117a), which condoned or contem

plated delay only in connection with public elementary

and secondary schools. To so apply that decision in a

case which doesn’t involve such public elementary and

secondary schools is not permissible.9 Florida ex rel. Haw

been built on the lands affected by the reverter p r o v is io n ]Deeper

v. Charlotte Park and Recreation Commission, Sup. Ct., 26 Jud.

Dist., Mecklenburg Co., N. C., Feb. 4, 1957 (2 Race Rel. L. Rep.

411-412).

9 True, there are cases in this Circuit and others which seem to

look the other way. See Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226

F. 2d 180, 184-185 (6th Cir. 1955); City of Montgomery v. Gilmore,

277 F. 2d 364, 369-370 (5th Cir. I960) ; Cummings v. City of

Charleston, 288 F. 2d 817 (4th Cir. 1961). But none in fact do,

especially in view of the narrow domain of concrete facts in which

the application or contemplation of gradual desegregation was

made in each:

In the Detroit Housing case, this Court did not have the ad

vantage of the later adjudications of the Supreme Court in Florida

ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U. S. 413, and Mayor and

City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877, aff’g 220 F. 2d

386 (4th Cir. 1955). Compare Booker v. State of Tennessee Board

of Education, 240 F. 2d 689 (6th Cir. 1957). In the Montgomery

Parks case, all the facilities had been closed pendente lite and a

modification of the injunction entered below was directed merely to

permit the District Court to consider a plan in the event that the

City desired to reopen its already closed parks and playgrounds

in the future on a nonsegregated basis. See Hampton v. City of

Jacksonville, Civ. No. 436-J, S. D. Fla., December 10, 1960 (5 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 1145, 1146). And in the Charleston Golf Course case,

delay of two months in the effective date of the injunction was

11

kins v. Board of Control, 350 U. S. 413 (1956); Mayor

and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877

(1955), aff’g 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955), which rev’d

Lonesome v. Maxwell, 123 F. Supp. 193 (D. Md. 1954).

In Hawkins, supra, the Supreme Court specifically ruled

that the second Brown decision could not be applied in

litigation which doesn’t involve public elementary and

secondary schools, saying at 350 U. S. 313, 314:

We directed that the case be reconsidered in the light

of our [first] decision in the Segregation Cases decided

May 17, 1954, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483. . . . In doing so, we did not imply that decrees

involving graduate study present problems of public

elementary and secondary schools. # * * Thus, our

second decision in the Brown case, 349 U. S. 294, . . .

which implemented the earlier one, had no application

to a case involving a Negro applying for admission

to a state law school. * * * As this case involves the

admission of a Negro to a graduate professional school,

there is no reason for delay.

See Booker v. State of Tennessee Board, of Education, 240

F. 2d 689 (6th Cir. 1957).

Lest doubt linger as to the narrow confines of the second

Brown decision, the Court’s affirmance in the Dawson case,

supra, is most compelling here. Involved there were cer

tain public recreational facilities maintained on a racially

segregated basis by the State of Maryland as well as the

City of Baltimore, both of which operated other such

facilities on a nonsegregated basis. Moreover, the State

allowed only because “plaintiffs’ counsel had tendered to the Dis

trict Court a suggested form of final order which contained the pro

vision that the injunction should not be operative until six months

following the date of entry of the order.” 288 F. 2d, supra at 818.

12

and City put squarely in issue the question presented here,

arguing:

There is here involved not only a question of whether

the State’s statutes should be denounced as violative

of constitutional guarantees, but also the nature of

the relief which should be granted. As this Court

demonstrated by its approach in the School Segrega

tion Cases, moderation and steady progress are more

desirable than abrupt change which may redound only

to the injury of citizens of both races. The issue has

also been posed in this case whether, if this Court

deems the School Segregation Cases applicable to pub

lic recreation, the remedy should be immediate desegre

gation or some other form of relief under the equity

jurisdiction of the local courts, who are familiar with

conditions as they exist in the State. We submit that

no further authority to sustain the desirability of this

sensible approach need be cited than this Court’s second

opinion in the School Segregation Cases.10

This question was manifestly so unsubstantial that the

Court did not require a plenary hearing thereon and af

firmed the judgment below per curiam.

Therefore, plaintiffs submit that the District Court mis

applied the principles articulated in the second Brown

decision, 349 U. S. 294 (1955),11 for that decision and its

proper application alike are plain.

10 Jurisdictional Statement, p. 19, Mayor and City Council of

Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 887 (No. 232, Oct. Term 1955).

u Logic as well as law requires limiting approval of delay to liti

gation involving public elementary and secondary schools, for

attendance in such schools is compulsory almost everywhere whereas

no one is compelled to utilize public recreational facilities. Dawson

v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d 386, 387 (4th

Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877. See McKay, “ Segregation and

Public Recreation” , 40 Va. L. Rev. 697, 724 (1954).

13

RELIEF

Under the foregoing circumstances, plaintiffs say that

they are entitled to a declaration vindicating their con

stitutional rights to be admitted to those recreational facil

ities from which they are nowT barred because of their

race or color; that they are entitled to an order setting

aside the postponement of their relief pursuant to the

gradual desegregation plan of the Park Commission of

the City of Memphis; and that they are entitled to a fur

ther order requiring their admission to the facilities main

tained and operated by the Commission, subject only to the

same rules and regulations applicable to all other persons

without delay.

W herefore, fo r the reasons hereinbefore set forth , it

is respectfully submitted that the judgm ent o f the court

below should be reversed with directions to grant the above

requested relief.

A. W . W illis, J r.

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

C onstance B aker M otley

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiff s-Appellants

E lwood H. Chisolm

B. L. H ooks

C. 0 . H orton

B. F. J ones

H. T. L ockard

R. B. Sugarmon, Jr.

Of Counsel

33