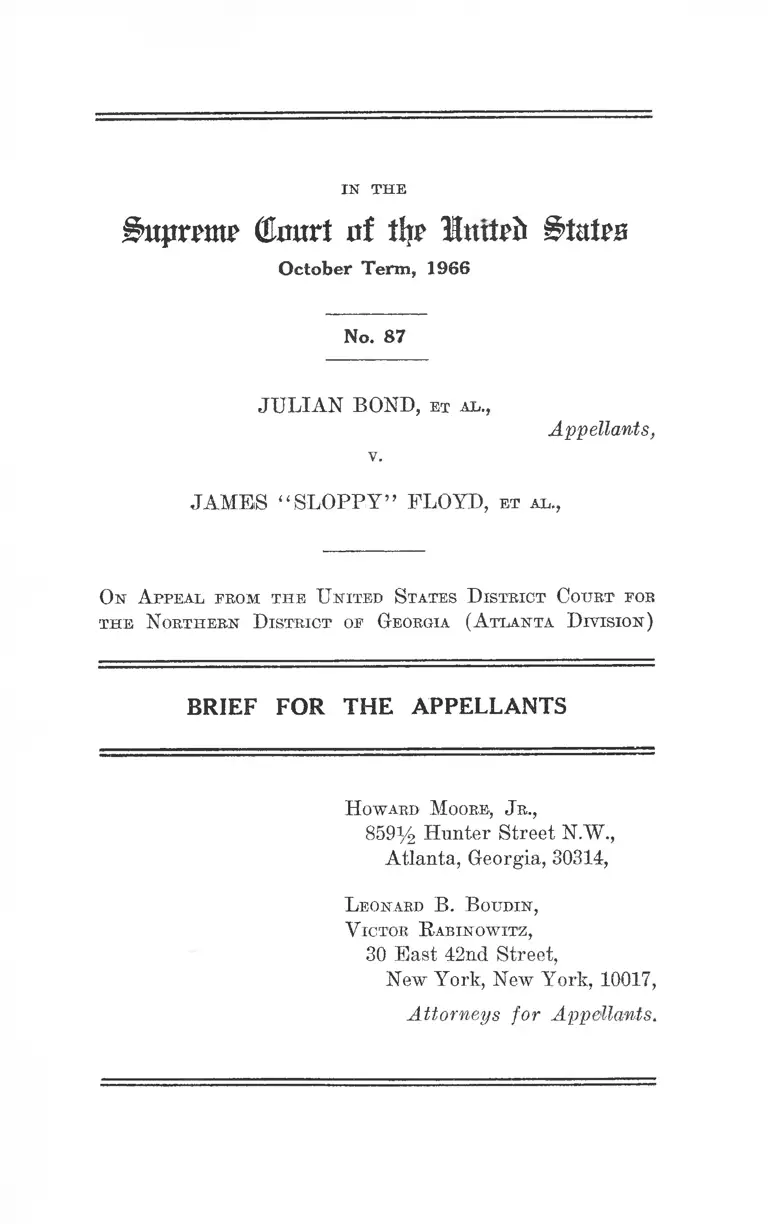

Bond v. Floyd Brief for the Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 24, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bond v. Floyd Brief for the Appellants, 1966. 28d3b916-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b6619634-01de-40c8-9cea-9c83271872d4/bond-v-floyd-brief-for-the-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

frtpnw (Emtrt ot tljp Inttpfr States

O ctob er T erm , 1966

N o. 87

JULIAN BOND, et ah.,

Appellants,

v.

JAMBS “ SLOPPY” FLOYD, e t a l .,

On Ap p e a l from t h e U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourt for

t h e N o r th er n D ist r ic t of G eorgia (A tlanta D iv is io n )

BRIEF FO R TH E A PPELLANTS

H oward M oore, J r .,

859% Hunter Street N.W.,

Atlanta, Georgia, 30314,

L eonard B . B o u d in ,

V ictor R a b in o w itz ,

30 East 42nd Street,

New York, New York, 10017,

Attorneys for Appellants.

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below.................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ........................................... 1

Questions Presented ................................................. 2

Constitution and Legislative Acts Involved . . . . . . . 2

Statement of the C ase............................................... 3

Summary of Argument ............................................ 9

A r g u m e n t :

I. The House did not have power under Georgia

law to bar Mr. Bond from office.................... 13

II. The oath provision of the Georgia Con

stitution, as interpreted below, is uncon

stitutionally vague under the Fourteenth

Amendment .................................................. 25

III. Mr. Bond’s exclusion from elected legislative

office solely because of his opinions and public

statements on national issues violated the

guarantee of freedom of speech and his immu

nities and privileges under the First and

Fourteenth Amendments ............................. 27

IV. Mr. Bond’s constituents have been disen

franchised in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment .................. 38

V. The disqualification of Mr. Bond was a bill

of attainder and an ex post facto law . . . . . . 42

Conclusion ................ 46

Appendix ......................................... 47

11

Citations

PAGE

C ases :

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 IT. S. 500 . . . . 27

Ashby v. White, 2 Lcl. Raym. 938, 14 S. T. 695

(1702) ................................................................ 18

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 ........................... 11, 26

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186.................................. 39

Barr v. Matteo, 360 U. S. 564 ................................ 27

Barry v. United States, 279 U. S. 597 ................... 23, 38

Beatty v. Myrick, 218 Ga. 629, 129 S. E. 2d 764

(1963) ................................................................. 17

Calder v. Bull, 3 Dali. (3 U. S.) 386 ....................... 45

Carrington v. Bash, 380 U. S. 8 9 ........................... 41

Chaplinsky v. State of New Hampshire, 315 U. S.

568 .............................................................. 33

In re Chapman, 166 U. S. 661................................ 23

Coleman v. MacLennan, 78 Kan. 711 (1908)......... 30

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 ............................. 27

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S.

278 ...................................................................... 11,26

Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. (73 U. S.) 3 6 ............. 29

Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. (71 U. S.) 277 . . . . 43

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ....................... 27

Dennis v. United States, 341 U. S. 494 ................ 34

De Veau v. Braisted, 363 U. S. 144....................... 45

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 .................. 31

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 ............ 34

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315........................ 34

Fowler v. Bostick, 99 Ga. App. 428, 108 S. E. 2d

720 (1959) ........................................................... 17

Ex parte Garland, 4 Wall. (71 U. S.) 333 ............. 43

C a s e s (Cont’d)

m

PAGE

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157....................... 33

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 64 ............ 27,30,31,33

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U. S. 368 ............................. 18, 39

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U. S. 496 ......................... . 29

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ........................... 34

Hiss v. Bartlett, 3 Gray 468 (1855) . ......... ........... 23

Kent v. Dulles, 357 U. S. 116....... ........... ............. 25, 27

Kingsley Pictures Corp. v. Regents, 360 U. S. 684. . 27, 28

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 366 U. S. 36 33

Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 TJ. S. 301 . . .27, 30, 31

Martin v. City of Struthers, 319 U. S. 141............ 30

Mishkin v. New York, 383 U. S. 502 .............. . 33

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 IT. S.

254 ................ .................... - ..................... 27,28,30,31

Noto v. United States, 367 IT. S. 290 .................... 37

Pennsylvania v. Nelson, 350 U. S. 497 ....... . 12

Rainey v. Taylor, 166 Ga. 476, 143 S. E. 383 (1928) 17

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533 ....................... 39, 40, 41

Schenk v. United States, 249 U. S. 4 7 .................... 32

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 ....................... 41

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U. S. 398 ...................... . 33

Slaughterhouse Cases, 16 Wall. (83 U. S.) 36 . .. . 29

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 .......................... 39, 41

Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U. S. 1 ..................... . 23

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513 ......................... 26

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ................ 27

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 ............. 31

Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U. S. 367 .................... 18

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 .................... . 27, 31

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 ............................. 41

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516........................... 33

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 . . . . . . . . . . 33

Toombs v. Fortson, 241 F. Supp. 65 .................... 3,4

Cases (C ont’d)

iv

PAGE

United States v. Brown, 381 U. S. 437 ......... 42, 43, 44,45

United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304 U. S.

144 ......................................... ............................ 32

United States v. C.I.O., 335 U. S. 106....... ........... 27

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 .......... 41

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542 ............. 29

United States v. Dennis, 183 F. 2d 201 (2d Cir.

1950) ................................................................... 33

United States v. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303 ................ 43, 45

United States v. Midwest Oil Co., 236 U. S. 459 . . . . 22

United States v. Miller, 249 F. Supp. 59 (S. D.

N. Y. 1965) ........................................................ 36

United States v. Mitcliell, 354 F. 2d 767 (2d Cir.

1966) ................................................................... 36

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 4 1 .................. 25

United States v. Seeger, 380 U. S. 163........... 35

Uphaus v. Wyman, 360 U. S. 72 ........................... 33, 36

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U. S. 1 ....................... 39

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barn

ette, 319 U. S. 624 .......................................... 32,33,35

White v. Clements, 39 G-a. 232 ................................ 16,17

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 .................... 27

Wilson v. North Carolina, 169 U. S. 586 ................ 23

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U. S. 375 ............................. 30, 32

Yates v. United States, 354 U. S. 298 .................... 37

U. S. Constitution:

Article I, Section 2 ............................................... 38

Article I, Section 1 0 ............................................... 13, 45

Article IV, Section 4 ........................................... 38

First Amendment -----2,8,11,12,26,27,28,31,32,33,37

Fourteenth Amendment ..................2, 8,13, 22, 29, 33, 38

Fifteenth, Amendment ........................................... 38

V

PAGE

F ederal and S tate S t a t u t e s :

Interposition Resolution (March 9, 1956) H. R.

185, Georgia Laws, 1956 Session ...................... 26

28 U. S. C. §1331 ....... ....................................... 1

28 U. S. C . § 1343(3) and (4) ....................... 1

28 U. S. C. § 2201 ............................................. . 1

28 U. S. C. § 2281 ............................... . . . . . . . . 1,8

42 U. S. C. § 1971................................................. 1

42 U. S. C. § 1983 ........................................ 1

42 U. S. C. § 1988 .................................................. 1

50 U. S. C. App. § 456(j) ..................................... 35

50 IT. S. C. App. § 462(a), (b) .............................. 44

Ga. Code Ann. § 89-101, subd. 5 ..................................17

G eorgia C o n st it u t io n :

Article II, Section II, Paragraph I (§ 2-1801, Ga.

Code Ann.) . .................................... • • 3,14, 24, 25, 48

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph V (§ 2-1605, Ga.

Code Ann.) ....................... - .........................3,11,23,47

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph VI (§ 2-1601,

Ga. Code Ann.) .............. . • • • ■ ................ 3,14, 25, 48

Article III, Section VI, Paragraph I (§ 2-1801, Ga.

Code Ann.) ....... ............................ . 2,10,14, 24, 25, 47

Article III, Section VII, Paragraph I (§2-1901,

Ga. Code Anil.) ...................2, 3,15,17, 47

Article VII, Section III, Paragraph VI (§ 2-5606,

Ga. Code Ann.) ................................................3,15, 49

VI

PAGE

R u les and R eso lu tio n s oe t h e G eorgia H ouse op

R epr esen ta tiv es :

House Rule 6 1 ........................................................ 3, 49

I n ter po sitio n R eso lu tio n (March 9, 1956),

G eorgia L aws 1956, No. 130 ............................... 26

House Resolution 19, January 10, 1966 ................ 2, 3,

8,13, 45, 49-50

C ongressional M aterials :

88 Cong. Rec. 2859 ............................................... 23

93 Cong. Rec. 15, 1 6 ............................................... 23

Senate Election, Expulsion and Censure Cases

from 1789 to 1960, S. Doc. No. 71, 87th Cong.

2d Sess.................................................................. 23

M iscella n eo u s :

4 Annals of Congress (1794) .............................. 28

Beloff, The Debate on the American Revolution,

1761-1783 (2d ed. 1960) ...................................... 19

Brennan, The Supreme Court and the Meiklejohn

Interpretation of the First Amendment, 79

Harv. L. Rev. 1 .................................................. 28

32 C. F. R. §§ 1160, et seq....................................... 35

Chafee, Free Speech in the United States (1964)

18,19, 34, 37, 39, 40

Commager, Can We Control the War in Viet Nam,

Saturday Review, S'ept. 17, 1966 ..................... 34

1 Cooley, Constitutional Limitations (8th ed. 1927) 44

DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America............ 42

2 Farrand, The Records of the Federal Convention

of 1787 ................................................................ 21

The Federalist, No. 60 (Cooke ed. 1961) .............. 21

vn

PAGE

M is c e l l a n e o u s (Cont’d ) :

Gellhorn, American Rights (1960) . .................... . 34

Hand, The Spirit of Liberty, Papers and Ad

dresses of Learned Hand (Dilliard ed. 1953) . . . 37

10 Holdsworth, History of English Law (1903) . . 18, 19

House of Commons Journal, XXXVIII ............... 20

House of Lords Journals, XVIII, 534 (1704)....... 18

Journal of Georgia Constitutional Convention,

Jan., May, 1789 . ................................................. 16

Journal of the Georgia Constitutional Convention

of 1798, 36 The Georgia Historical Quarterly,

No. 4, Dec. 1952 . ............................................... 16

May, Constitutional History of England, I (1863) 18

May, Treatise on the Lawr, Privileges and Pro

ceedings and Usage of Parliament (17th ed.

1964) .................................................................. 20

McCall, History of Georgia, II (1816) ................ 22

McElreath, A Treatise on the Constitution of

Georgia (1948) ................ 16

Meiklejohn, Political Freedom. (1948) .................. 28

Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (1943) 19

New York Times, Jan. 5, 1966, p. 1 ....... ............... 5

Note, The Right of Congress to Exclude its Mem

bers, 33 Va! L. Rev. 322 (1947) ......................... 22

Parliamentary History, Vol. XVL, 587 ................. 19

Parliamentary History, Vol. XVII, 131 .............. 20

Postgate, That Devil Wilkes (1930) .................... 19

Pusey, Charles Evans Hughes (1951) .................. 37

V l l l

PAGE

M isc ella n eo u s (Cont’d ) :

Rude, Wilkes and Liberty .................................... 19

Saye, A Constitutional History of Georgia (1948) 16

Schlesinger, Prelude to Independence (Vintage ed.

1965) ................................................................... 19

A Stenographic Report of the Proceedings of the

Georgia Constitutional Convention (1877) . . . . 16

Story on the Constitution (6th ed. 1891) .............. 21

Thompson, Reconstruction in Georgia (LXIV

Studies in History, Economics and Public Law,

Columbia University, 1915) ............................... 42

Ware, A Constitutional History of Georgia (1947) 16

Williams, The Eighteenth Century Constitution

(1960) .................. 18,19,20

Warren, The Making of the Constitution (1928) .. 20, 22

Willoughby, The Constitution of the United States,

I (2d ed. 1929) 22

IN' THE

Stqjrrpm? dmtrt nf % lutteb BtnUs

O cto b er T erm , 1966

No. 87

------------ o------------

J u l ia n B ond , et al .,

v.

Appellants,

J am es “ S l o p p y ” F loyd, e t al .,

On A ppe a l from t h e U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourt for

t h e N o rth ern D istr ic t of G eorgia (A tlanta D iv is io n )

-------------------------- — ....... — o ---------------------------------------------

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANTS

O pin ions Below

The opinions below (R. 132, 154) are reported at 251 F.

Supp. 333 (N. D. Ga. 1966).

Ju risd ic tio n

The judgment below (R. 178) was entered on February

16, 1966. Appellant filed a notice of appeal in the court

below on the same day (R. 180).

The District Court had jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C.

§§ 1331, 1343, subds. 3 and 4, 2201 and 2281, and under 42

U. S. C. §§ 1971, 1983 and 1988. The appellees moved to

dismiss the appeal or to affirm the judgment below. On June

20, 1966, the Court noted probable jurisdiction (R. 186).

2

Q uestions Presented

1. Did the Georgia House of Representatives exceed

its authority under the Georgia Constitution in excluding

Mr. Bond from his elected office as representative to the

House solely because of the opinions he expressed on issues

of national concern.

2. Are the provisions of the Georgia Constitution, as

interpreted by the court below, unconstitutionally vague

under the Fourteenth Amendment.

3. Did the exclusion of Mr. Bond from legislative office

solely because of the opinions he expressed impair freedom

of opinion and speech as well as his privileges and immu

nities under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

4. Did his exclusion from office disenfranchise Mr.

Bond’s constituents in violation of the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

5. Does House Resolution 19 disqualifying Mr. Bond

from his elected office constitute an ex post facto law or a

bill of attainder in violation of Article I, Section 10 of the

United States Constitution.

Constitution and Legislative A cts Involved

The provisions of the Georgia Constitution involved

in this case are as follows:

Article III, Section VII, Paragraph I (§2-1901,

Ga. Code Ann.), making the House “ the judge of

the election, returns, and qualifications of its mem

bers” , infra, p. 47.

Article III, Section VI, Paragraph I (§ 2-1801,

Ga. Code Ann.), setting forth the members’ qualifi

cations, infra, p. 47.

3

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph V (§ 2-1605,

G-a. Code Ann.), specifying the oath of office of rep

resentatives, infra, p. 47.

The following provisions of the Georgia Constitution

setting forth the disqualifications for office are also involved

in this case:

Article II, Section II, Paragraph I (§ 2-801, Ga.

Code Ann.), infra, p. 48.

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph VI (§ 2-1606,

Ga. Code Ann.), infra, p. 48.

Article VII, Section III, Paragraph VI (§ 2-

5606, Ga. Code Ann.), infra, p. 49.

The legislative actions involved in this ease are as

follows:

House Eule 61 of the Georgia House of Repre

sentatives adopting the provisions of Article III,

Section VII of the Georgia Constitution, infra, p. 49.

House Resolution 19 of January 10, 1966, exclud

ing Mr. Bond from office, infra, pp. 49, 50.

Statement of the Case

This case arises from the refusal of the Georgia

House of Representatives to seat the appellant Julian

Bond, the duly elected Representative from the 136th

House District, Atlanta, Pulton County, Georgia. The

events which led to his exclusion from the Georgia House

are as follows:

A . H ow Mr. Bond A cq u ired th e R igh t to be Sw orn

and S ea ted as a M em ber o f th e G eorg ia H ouse

o f R ep resen ta tives

The United States District Court for the Northern

District of Georgia in Toombs v. Forison, 241 F. Supp. 65

4

(N.D. Ga. 1965), ordered the Georgia House of Rep

resentatives reapportioned on the basis of population. As

a result, Fulton County, Georgia, gained 21 seats in ad

dition to the three seats it already held, making a total of 24

Representatives from that county, one for each of the 21

newly created House Districts and three Representatives

at large. Pursuant to legislation enacted in compliance

with the order in Toombs v. Fortson, supra, House District

136 was created and a primary election was held on May

5, 1965 to nominate a candidate for this office (R. 4, 105).

Appellant Bond, a 25-year-old Negro pacifist and communi

cations director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating

Committee (hereinafter SNCC) entered and won the Demo

cratic nomination. He received 1,243 votes, and the Rev.

Howard Creecy Sr., his opponent, a Negro also, 522 votes

(R. 4, 105, 106).

In the general election held on June 15, 1965, appellant

Bond defeated his Republican opponent, Malcom J. Dean,

Dean of Men at Atlanta University and a Negro, by a

vote of 2,320 to 487 (R. 4, 106). Eighty-two per cent of the

eligible voters voted, more than in any other House District

(R. 106). House District 136 is predominantly Negro. Of

the 6,500 voters, 6,000 are Negroes (R. 4, 106).

Appellant Mrs. Arel Keyes voted for Julian Bond in

both the primary and in the general election. Appellant

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Nobel Peace Prize laureate

and noted civil rights leader, is a resident of House District

136 (R. 4, 120).

B. E vents o f Jan u ary 6 , 1966 G iving R ise to the

D em and to E xclu d e Mr. Bond

On January 6, 1966 SNCC issued a statement to the

press critical of American policy with respect to Viet

Nam and with respect to equal rights for Negroes within

the United States (R. 135, 136). The statement placed

5

responsibility for the murder of Samuel Young 1 in Tus-

kegee, Alabama, upon the federal government and equated

the failure of the Administration to protect Samuel Young

with the death of Vietnamese peasants emanating from an

aggressive foreign policy conducted in violation of interna

tional law (R. 136, 137). SNCC charged the United States

with deception in its concern for freedom for the Viet

namese people and for the freedom of colored people in the

Dominican Republic, Africa, and in the United States (R.

136, 137).

Scoring the unpunished acts of violence and false im

prisonment to which its members and others engaged in the

struggle for equal rights in the South had been subjected,

the SNUG statement questioned both the ability and the

desire of the federal government to guarantee free elections

abroad and labeled declarations to “ preserve freedom in

the world”, a hypocritical mask behind which the United

States suppresses liberation movements (R. 137).

The statement expressed SNCC’s support for men in

this country unwilling to respond to a military draft.

SNCC questioned, “ where is the draft for the freedom

fight in the United States?” (R. 137). The statement, after

noting the disproportionate number of Negroes serving

in Viet Nam, concluded:

“ We therefore encourage those Americans who

prefer to use their energy in building democratic

forms within this country. We believe that work in

the civil rights movement and with other human re

lations organizations is a valid alternative to the

draft. We urge all Americans to seek this alterna-

1 Samuel Young, a SNCC worker, was a Navy veteran. He

lost one of his kidneys from a wound he had received in the ill-fated

Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961 off the coast of Cuba. Young was

shot and killed in January, 1966 near a gasoline service station in

Macon County, Alabama as he approached the station to use the

rest-room. New York Times, Jan. 5, 1966, p. 1, col. 2.

6

tive, knowing full well that it may cost their lives—

as painfully as in Viet Nam.” (R. 137).

Later in the afternoon, a newsman employed by a state-

owned radio station called Julian Bond, who had not parti

cipated in drafting the statement, at his residence in

Atlanta and inquired whether Bond endorsed the SNCC

statement (R. 36, 45, 48). Bond said that he did, adding

that as a pacifist he opposed all wars and was “ eager and

anxious to encourage people not to participate in it [war]

for any reason that they choose” (R. 111). He further

stated that he agreed with the statement for the reasons

set forth because he thought it was “ sorta hypocritical for

us to maintain that we are fighting for liberty in other

places and we are not guaranteeing liberty to citizens in

side the continental United States” (R. 111). He saw no

conflict between his endorsement of the SNCC statement

and the performance of his duties as a legislator or his

ability to take the oath of office (R. 111).

C. P roceed in gs in th e H ouse o f R ep resen ta tiv es

to E xclu d e Mr. B ond

On the morning of January 10, 1966, when Mr. Bond

arrived at the House of Representatives to he sworn in as

the Representative-elect from the 136th House District, the

Clerk of the House ordered him to stand aside as the oath

was administered to the other Representatives. Challenges

to Mr. Bond’s right to he sworn and seated, based upon his

statement to the press, were filed by at least 75 white mem

bers of the House. The petitions charged, inter alia, that

Mr. Bond’s actions and statement gave aid and comfort to

the enemies of the United States, violated the Selective

Service laws, and tended to bring discredit and disrespect

on the House of Representatives (R. 13-15) ; that he had

stated that he “ admires the courage of those persons who

burn their draft cards” (R. 13). It was also charged that

the statements and views of Mr. Bond disqualified him

7

from taking the oath to support the Constitution of the

United States and the Constitution of Georgia required of

a member of the House of Representatives (R. 14, 18, 19),

The petition charged that Mr. Bond’s “ full endorsement”

of the SJNTCC policy statement “ is totally and completely

repugnant to and inconsistent with the mandatory oath

prescribed” for members (R. 19).

Mr. Bond tiled a written response to the challenge peti

tions, denying that he was disloyal, disqualified, or that he

had committed treason, or violated any law. His response

alleged, inter alia, that the challenges, contests and petitions

were filed against him to deprive him of his rights under

the First Amendment (R. 21).

A Special Committee composed of the Rules Committtee

and three additional members, two of whom were Negroes,

was appointed to hear the challenge. Three of the persons

challenging Mr. Bond’s right to be seated served on the

Special Committee (R. 9).

A hearing was then held on the challenge petitions for

the purpose of deciding “ the substance of what Mr. Bond

said” before offering himself for membership in the House,

“ and the intentions behind what he said” (R. 29). For evi

dence, the challengers introduced a tape of the telephonic

interview on January 6, 1966, a tape of an interview with

Mr. Bond in the hallway of the State Capitol immediately

after the Clerk refused to administer the oath to him (R.

115), and the testimony of Mr. Bond (R. 81). Mr. Bond was

asked at the hearing whether he admired “ the courage of

persons who burn their draft cards” (R. 40). He replied:

“ I admire people who take an action, and I admire

people who feel strongly enough about their convic

tions to take an action like that knowing the conse

quences that they will face, and that was my original

statement when asked the question.” (R. 41).

8

Mr. Bond called four witnesses who urged his seating

and stated that he deserved the right to he seated (R. 58, 61,

65, 69).

The Special Committee then recommended that Mr.

Bond not be seated (R. 88). The two Negro members dis

sented along with a white legislator from Fulton County

(R. 89, 92). The House then adopted House Resolution 19

not to seat Mr. Bond in accordance with the majority recom

mendation of the Special Committee (R. 99).

D. P roceed in gs in th e Court B elo w to R em ed y

th e E xclusion

Mr. Bond and his constituents thereupon instituted this

action for injunctive relief and a declaratory judgment that

the legislature’s action was unauthorized by the state Con

stitution and violated their rights under the federal Consti

tution. A three-judge court was convened under 28 U. S. C.

§ 2281, and conducted a trial of the issues.2

On February 14, 1966, the Court rendered final judg

ment against the appellants. It unanimously held that it had

jurisdiction because the plaintiffs had asserted substantial

First Amendment rights (R. 140). The Court, Chief Judge

Tuttle dissenting, struck from the complaint the names of

the appellants other than Mr. Bond on the ground that they

lacked “ such a direct interest in the litigation as would

give them standing to bring the complaint” (R. 141).

On the merits, the Court was also divided. The majority

agreed that “ [t]he substantial issue in the case rests on the

guaranty of freedom of speech or to dissent, under the First

Amendment as the amendment has long been applicable

to the states under the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment” (R. 142). Nevertheless, it held that Mr.

Bond’s “ statements and affirmation of the SNC'C state-

2 At the trial, in order to avoid adding the State Treasurer as a

party defendant, the parties stipulated that the State of Georgia

would pay Mr. Bond’s legislative salary should he prevail upon this

appeal (R. 185).

9

ment as they bore on the functioning of the Selective Serv

ice System could reasonably be said to be inconsistent with

and repugnant to the oath which he was required to take”

(E. 153).

Chief Judge Tuttle, dissenting, was of the view that

since substantial federal constitutional issues of freedom

of speech were involved, the Court was under a duty to con

strue the Georgia constitutional provisions “ with an eye to

the avoiding of the constitutional question if possible” (R,

166). He concluded that Mr. Bond had met the qualifica

tions for legislative office explicitly set forth in the Consti

tution and that it could not be construed to authorize

rejection from elected office for a reason not specified, viz.,

for making a lawful public statement upon foreign affairs.

E. S u b se q u e n t A c tio n s b y t h e E le c to ra te

While this appeal was pending the Governor of Georgia

called a special election to fill the vacancy created by Mr.

Bond’s exclusion. Mr. Bond entered the election on protest

and won it on February 23, 1966. He wTas again prevented

from taking his seat by a decision of the Rules Committee

authorized by the House to act during the legislative recess.

The decision was made after a hearing in which lie declined

to recede from the earlier position which had. led to this

litigation.3 On September 14, 1966, Mr. Bond again won the

Democratic primary and will be the Democratic candidate

in the November 1966 election.

Summary of Argument

I

In excluding Mr. Bond from the office to which he had

been elected, the Georgia House exceeded its authority

3 See appellees’ motion to affirm or dismiss, appellants’ brief in

opposition and motion to advance, and appellants’ memorandum of

June 14, 1966.

10

under the clear language of the Georgia Constitution. This

conclusion is further supported by the lessons of Anglo-

American history, by Georgia case law, and by the need to

avoid the substantial constitutional problems otherwise pre

sented by this case.

The Georgia Constitution is explicit on the subject of

the qualifications and disabilities for office in the House.

Article III, Section VI, Paragraph I sets forth the qualifi

cations, infra, p. 47. Three succeeding articles set forth

in precise terms the reasons for disqualifications or in

eligibility, infra, pp. 48, 49. The court below agreed that

Mr. Bond met these constitutional requirements. The case

does not present the different and broader power of the

House to punish its members “ for disorderly behavior or

misconduct,” infra, p. 49.

The constitutional provision that the House “ be the

judge of the election returns, and qualifications of its mem

bers” authorizes it to determine whether the constitutional

qualifications have been met, not to add new ones. This view

is epitomized by the Middlesex election case of John Wilkes,

infra, p. 19 which was reflected in the language of the

federal Constitution and in many of the succeeding state

constitutions prescribing qualifications for legislative office.

The oath required of a legislator that he will support

the federal and state Constitutions, and will “ so conduct

myself, as will, in my judgment, be most conducive to the

interests and prosperity of this State”, infra, p. 47 does

not authorize the House to impose additional qualifi

cations. Such a construction of the oath is a distortion of

language raising serious constitutional problems of vague

ness, impairment of freedom of speech, denial of the fran

chise, and gives rise as here to a bill of attainder and an ex

post facto law. It also violates the salutary rule that courts

should, if possible, seek a construction which would avoid

constitutional problems.

11

II

There is nothing vague about the provisions of the

Georgia Constitution which explicitly set forth both the

qualifications and disqualifications of members of the

legislature. However, the finding below in the constitutional

requirement of an oath of office, Article III, Section IY,

Paragraph Y, of an implicit substantive qualification for

office makes the oath unconstitutionally vague. In terms,

the oath is a promise that its taker will support the federal

and state Constitutions and conduct himself in his judg

ment in the state’s best interests. The court below has

changed this promissory oath into a representation as to

the past, giving a legislative majority the authority to

determine whether the oath can be sincerely taken. The

required assessment of the legislator’s past behavior, state

ments and opinions finds no standard in an oath as to what

is “ most conducive to the interests and prosperity of this

State . . . ” in his judgment. Such an oath is unconstitution

ally vague under this Court’s decisions in Cramp v. Board

of Public Instruction, 368 II. S. 278 and Baggett v. Bullitt,

377 U. S. 360. The vice of vagueness is aggravated since the

oath as applied admittedly touches upon sensitive First

Amendment freedoms.

III

It is not disputed that Mr. Bond was excluded from

office solely because of his opinions and statements on

national issues. This exclusion strikes at the “ national com

mitment” for debate on public issues embodied in the

First Amendment. It does violence to the guarantee in

the privileges and immunities clause of the right to as

semble, debate and petition on issues affecting the federal

government. An elected legislator has as much right as his

constituents under the First Amendment to have these

beliefs and to state his opinion on the subject. Indeed, he

has a special duty to state his views to his constituents who

12

are entiled to have a basis for evaluating him. He also

carries out his responsibilities by expressing their views.

Neither the principle of separation of powers nor that

of federalism justifies a diminution of First Amendment

protections. It is a judicial function to restrain illegal action

by the other branches of government, and the federal courts

have the responsibility of protecting federal constitutional

rights against state action. The test applied below of a

‘ ‘ rational evidentiary basis ’ ’ has been held to be appropriate

in cases of economic regulation, not where First Amendment

freedoms are involved. An elected representative has an

absolute right to express his opinions on public issues

without being declared ineligible for office.

But even under the lower court’s own test, there was no

rational basis for believing that Mr. Bond’s statements

“ could reasonably be said to be inconsistent with and repug

nant to the oath which he was required to take.” The SNCC

statement which he endorsed was a vigorous expression of

opinion on national affairs and protected by the First

Amendment. Mr. Bond’s approval of it and his admiration

for the courage of persons who were prepared to act

in accordance with their conscience was not inconsistent

with his oath of office. There was no substantive state

interest here comparable to those found in cases involving

conspiracies to overthrow the government, obscenity and

disorderly conduct in the street. The state has no legitimate

interest in the suppression of dissenting views in its legisla

ture; indeed, the policy of Georgia, constitutionally estab

lished, is not to disqualify legislators even for criminal con

duct until after a judgment of criminal conviction. The very

subject under discussion, national conscription for military

service, is beyond state jurisdiction. Pennsylvania v.

Nelson, 350' U. S. 497. But there is a real state interest

inherent in a democracy in the expression of dissenting-

views by the members of the Legislature, and in obedience

to the choice of the electorate.

13

IV

Mr. Bond’s constituents have been deprived of repre

sentation in the House. Mrs. Keyes’ right to cast a

meaningful vote and Dr. King’s right to be represented

are as important as Mr. Bond’s right to take office. To

deprive them of these rights because the legislature dis

approved of Mr. Bond’s political views is to violate the

due process and the equal protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment. The court below was therefore in error

in holding that they lacked a direct interest in the litigation.

V

House Resolution 19 is a bill of attainder under the

tests established by history and by this Court and violates

Article I, Section 10 of the United States Constitution.

It named Mr. Bond as the object of the resolution and it

punished him for his expressions of political opinion.

The House Resolution is also an ex post facto law, viola

tive of the same constitutional provisions. The Georgia

Constitution afforded no notice that a legislator’s opinions

and public statements would disqualify him from office.

It is an ex post facto law because it is punishment for acts

innocent at the time of occurrence.

ARG UM ENT

P O T N T I

The H ouse did not have power under Georgia law

to bar Mr. Bond from office.

Chief Judge Tuttle, dissenting below, correctly stated

that “ the House exceeded its authority [under the Consti

tution and laws of Georgia] in voting to reject Bond”

(R. 154, 176). This conclusion was required by the clear

14

language of the Georgia Constitution, the absence of con

flicting state court decisions, and the need to avoid the

substantial constitutional problems otherwise presented by

this case.

The Georgia Constitution is explicit on the subject of

the qualifications of and the disabilities for office in the

House of Representatives.

Article III, Section VI, Paragraph I provides:

“ Qualifications of representatives.—The Repre

sentatives shall be citizens of the United States

who have attained the age of twenty-one years, and

who shall have been citizens of this State for two

years, and for one year residents of the counties from

which elected.” (§2-1801, Ga. Code Ann.)

The disqualifications appear in three other provisions of

the same Constitution.

Article II, Section II, Paragraph I, entitled “ Registra

tion of electors ; who disfranchised ’ ’, provides that:

“ * * * the following classes of persons shall not

be permitted to register, vote, or hold any office, or

appointment of honor, or trust in this State, to-wit:

1st. Those who shall have been convicted in any court

of competent jurisdiction of treason against the

State, of embezzlement of public funds, malfeasance

m office, bribery or larcency, or of any crime involv

ing moral turpitude, punishable by the laws of this

State with imprisonment in the penitentiary, unless

such persons shall have been pardoned. 2nd. Idiots

and insane persons.” (§ 2-801, Ga. Code Ann.)

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph YI, entitled “ Eligi

bility; appointments forbidden”, denies a seat in either

House to persons “ holding a military commission, or other

appointment, or office having an emolument, or compensa

tion annexed thereto, under this State, or the United States”

(with certain exceptions) and to “ any defaulter for public

money, or for any legal taxes”. (§2-1606, Ga, Code Ann.)

15

Article VII, Section III, Paragraph VI, entitled “ Profit

on public money” , makes it “ a felony, and punishable as

may be prescribed by law, a part of which punishment shall

be disqualifications from holding office” for a member of the

General Assembly to receive “ any interest, profits or per

quisites, arising from the use or loan of public funds in his

hands or moneys to be raised through his agency for State

or county purposes.” (§2-5606, Ga. Code Ann.)

The precision of these qualifications stands out in con

trast to the broader power of the House to punish its mem

bers “ for disorderly behavior, or misconduct, by censure,

fine, imprisonment, or expulsion” Article III Section VII

Paragraph I (§ 2-1901, Ga. Code Ann.). The breadth of this

latter power is appropriately balanced in the Georgia Con

stitution as in most others by the requirement that “ no

member shall be expelled except by a vote of two-thirds of

the House to which he belongs ’ ’, ibid.

The majority below did not disagree with the Chief

Judge’s view that Mr. Bond could not be excluded under

any specific provision of the Georgia Constitution. Instead,

it denied that the “ qualifications and disqualifications of

legislators in the Georgia Constitution are all-inclusive” (R.

148), and it found in the principle of separation of powers

an implied right in the Georgia House to reject the majority

choice of the voters. It said that the Chief Judge’s “ re

strictive ” view was “ unfounded in recognized authority and

not in keeping with our history or the principle of separation

of powers” (R. 144).

It is not clear from the decision below which of the au

thorities and facts it sets forth was intended to be covered

by the terms “ authority” , “ history” and “ separation of

powers” . Regardless of how they are categorized, they do

not support the conclusion of the court below.

Every Georgia Constitution, including the first Consti

tution of 1777, has specified the qualifications of representa-

16

lives.4 The frequent changes which have been made in these

qualifications suggest that close attention has been paid to

the problem, and that the drafters of the Constitutions have

always sought to make the qualifications explicit and to

keep them politically meaningful. There is no indication in

the journals or reports of the conventions5 or in the schol

arly discussions of Georgia constitutional law8 that qualifi

cations for legislative office existed outside those specified in

the Constitution.

No state court in Georgia has ever held that the House

has the power to impose qualifications. The Supreme

Court of Georgia held directly to the contrary in 1869

when the results of an election for Clerk of the Superior

Court were challenged on the ground that the victor had

‘‘one-eighth or more of African blood” and hence was

ineligible under the Georgia code. In White v. Clements,

39 Ga. 232, 265, the court definitively held that “ if the

Constitution prescribes a qualification for an officer, it by

necessary implications denies to the legislature the power

to fix new and other qualifications.”

The court below cited three Georgia state cases for

the proposition that its courts “ have consistently refused

to take jurisdiction over controversies having to do with

qualifications of legislators. The Senate or House, as hap

pened to be the case, was deemed to have exclusive juris-

4 The constitutions are cited at R. 143.

5 See, e.g., Journal of the Georgia Constitutional Convention,

January 4, 1789, May 4, 1789; Journal of the Georgia Constitutional

Convention of 1/98, ed. Saye, 36 The Georgia Historical Quarterly,

No. 4, Dec. 1952, 350, 356, 365; A Stenographic Report of the

Proceedings of the Georgia Constitutional Convention, 1877, 374.

6 See McElreath, A Treatise on the Constitution of Georgia

(1912); Saye, A Constitutional History of Georgia (1948); Ware,

A Constitutional History of Georgia (1947).

17

diction under the Georgia Constitution. Rainey v. Taylor,

1928, 166 Ga. 476, 143 S. E. 383; Fowler v. Bostick, 1959,

99 Ga. App. 428, 108 S. E. 2d 720; and Beatty v. Myrick,

1963, 218 Ga. 629, 129 S. E. 2d 764” (R. 143-144). None

of those cases, as Chief Judge Tuttle pointed out, gives

the House or Senate jurisdiction “ to judge whether the

contesting parties lacked qualifications which are not ex

pressly stated as ‘qualifications’ or rules of ‘eligibility’ in

the Georgia Constitution” (R. 167). In Rainey, the Gen

eral Assembly was held solely authorized to determine

whether the successful candidate was disqualified under a

constitutional prohibition against one holding another state

office. In Fowler, the same issue was raised with respect

to the position of court clerk. Beatty involved not quali

fications but the judging of the election results.

Those cases were correctly decided under the constitu

tional provision that “ each House shall be the judge of

the election, returns and qualifications of its members . .

Article III, Section VII, Paragraph I (§2-1901, Ga. Code

Ann.). That provision does not authorize the House to

establish qualifications other than those set forth in the

Constitution, nor did the court below7 so hold. It means

that the House is to determine whether the members meet

the qualifications specified by law7.

The lower court’s statement that “ there is at least

one disqualification in the Georgia law which is not con

tained in the Constitution” (R. 147) is not apposite. It is

not clear that the statute making “ persons of unsound

mind” ineligible for “ civil office” refers to the legislature

(Ga. Code Ann. §§ 89-101 subd. 5), cf. 17 Op. Atty. Gen.

(U. S.) 420 (1882) interpreting Art. 2, Section 4 of the

United States Constitution; if so, it would violate the

Georgia Constitution, White v. Clements, supra. In any

event, the establishment of qualifications by statute is very

different from a House Resolution adopted pursuant to

quasi-judicial powers.

18

Chief Judge Tuttle’s conclusion that the qualifications

must he specified by law, not promulgated on an ad hoc

basis, is supported by the 18th century parliamentary

history of England and by the debates and actions of the

Federal Constitutional Convention of 1787. The former is

important because of the close relationship between John

Wilkes and the Revolutionists, the latter because the United

States Constitution was followed by the Georgia Constitu

tion which like it made the qualifications for legislative office

quite specific.

Significant English history on this point goes back to

Ashby v. White (1702), 2 Ld. Raym. 938, 14 S. T. 695,

where Chief Justice Holt, dissenting, expressed the view

that “ since the privileges of Parliament were a part of the

law, they must be defined by the law, and not by the resolu

tions of the House” . 10 Holdsworth, History of English

Law, 543.7 As Mr. Justice Frankfurther has said, “ The

House of Commons’ claim of power to establish the limits of

its privilege has been little more than a pretense since Ashby

v. White, 2 Ld. Raym. 938, 3 id. 320”, Tenney v. Brandhove,

341 U. S. 367, 376-377.®

The principle was established most dramatically by

the Middlesex election case of John Wilkes 9 who is known

in Anglo-American constitutional history for more than

his successful assault upon general warrants employed to

ferret out opposition to the Crown,10 or legislative im-

7 Holt’s opinion was adopted by the House of Lords. See, H. L.

Jour. XVII, 534 (1704) ; Williams, The Eighteenth Century Con

stitution (1960) 221, 224-228.

8 Ashby is also cited in Gray v. Sanders, 372 U. S. 368, 375, n. 7.

9 The Middlesex election case is described at length in May,

Constitutional History of England, I, 364-384; Chafee, Free Speech

in the United States (1964) 242-247; 10 Holdsworth, History of

English Law, 540-549; Williams, The Eighteenth Century Con

stitution (1960), 222-223, which includes significant parliamentary

resolutions on the subject, id. at 242-244.

10 Chafee, op. cit. 242.

19

munity from arrest11 or Ms insistence upon the reporting

of parliamentary debates.12

Wilkes was elected to the House of Commons as a

member for the County of Middlesex in 1768 and was ex

pelled from it on account of “ seditious libel” , viz., his at

tack upon George III. He was re-elected, re-expelled and

declared incapable of being elected to serve in that Par

liament. On his third re-election the House declared his op

ponent to have been elected. “ The crux of the matter

was whether the House had power to incapacitate Wilkes

from being elected.” 13 This issue was bitterly contested

in England, with financial and other support from the

American colonists, whose cause was identified with that of

Wilkes.14 It was recognized in both countries that the

right of the people to choose their representatives was at

stake. Thus, in the House of Commons serjeant Glyn

stated:15

‘ ‘ The disqualification of Mr. Wilkes not being

the law of the land, the freeholders of Middlesex

were not obliged to take notice of it. That the

disqualifications of bodies of men, as clergy, aliens,

etc., were all either by express laws, or by implica

tion from the common law, and that the votes of

the House to that effect were only declaratory, but

not enacting. That undoubtedly the House had a

jurisdiction over its own members, and were judges

of the rights of electors, but such judgments must

be according to law, a natural consequence of every

11 Ibid.

12 E. N. Williams, op. cit. 223.

13 Ibid.

14 Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (1943) 201, 305,

317, 321-325, 425, Rude, Wilkes and Liberty, Beloff, The Debate-

on the American Revolution, 1761-1783 ( 2d ed. 1960 ) 21, 27; Post

gate, That Devil Wilkes (1930) 150, 186, 234-235; Schlesinger,

Prelude to Independence (Vintage ed 1965) 35-37 and passim.

15 Pari. Hist. Vol. XVI, 587 in; Holdsworth, op. cit. at 543.

20

court of judicature in this kingdom. That the rights

of the freeholders of Middlesex, as well as the right

of every citizen or burgess, was an inherent right

in them, not derived from the House of Commons,

and therefore could not be taken away from them

by the House, except in cases when, offending against

law, they had forfeited a right to such privileges.”16

In 1782 the House of Commons expunged the prior

exclusions “ as being subversive of the Rights of the whole

Body of Electors of this Kingdom”.17 Since then it has

been established law in England that there may be no dis

qualification for office except for reasons established by

law, see Erskine May’s Treatise on the Law, Privileges and

Proceedings and Usage of Parliament (17th ed. 1964)

60-63.

It was quite natural that the draftsmen of the various

American Constitutions should take pains to ensure that

the legislative bodies be selected by the people in accord

ance with prescribed conditions of office. Thus, on the floor

of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 James Madison

successfully led the opposition to a proposal “ to give to

Congress power to establish qualifications in general . . .

and it also defeated the proposal for a property qualifica

tion. . . .” Warren, The Making of the Constitution (1928),

420-422. As the Journal of the Federal Convention of

1787 states:

“ Mr. Madison was opposed to the Section as

vesting an improper and dangerous power in the

Legislature. The qualifications of electors and

elected were fundamental articles in a Republican

Govt, and ought to be fixed by the Constitution. If

the Legislature could regulate those of either, it can

by degrees subvert the Constitution. A Republic

may be converted into an aristocracy or oligarchy

is See also Pari. Hist. Vol. XVII, 131-134.

n H. C. Tour. XXXVIII, 977 (May 3, 1782) ; William, op. cit,

244.

21

as well by limiting* the number capable of being

elected, as the number authorised to elect. In all

cases where the representatives of the people will

have a personal interest distinct from that of their

Constituents, there was the same reason for being-

jealous of them, as there was for relying on them

with full confidence, when they had a common inter

est. This was one of the former cases. It was as

improper as to allow them to fix their own wages, or

their own privileges. It was a power also which

might be made subservient to the views of one fac

tion agst. another. Qualifications founded on

artificial distinctions may be devised, by the stronger

in order to keep out partizans of a weaker faction.

# # *

Mr. Madison observed that the British Parliament

possessed the power of regulating the qualifications

both of the electors, and the elected; and the abuse

they had made of it was a lesson worthy of our

attention. They had made the changes in both cases

subservient to their own views, or to the views of

political or Religious parties.” 2 Farrand, The

Records in the Federal Convention of 1787 (Aug. 10,

1787), pp. 249-50.

Authoritative contemporary discussion was to the same

effect. Alexander Hamilton wrote:

“ The qualifications of the persons who may

choose or be chosen . . . are defined and fixed by the

constitution; and are unalterable by the legislature. ’ ’

The Federalist, No. 60 (Cooke ed. 1961) 409.

And Mr. Justice Story wrote:

“ It would seem but fair reasoning, upon the

plainest principles of interpretation, that when the

Constitution established certain qualifications as

necessary for office, it meant to exclude all others as

requisites. From the very nature of such a provi

sion, the affirmation of these qualifications would

seem to imply a negative of all others.” Story on

the Constitution, § 625 (6th ed. 1891) 461.

Mr. Warren is correct in concluding that, “ The elimi

nation of all power in Congress to fix qualifications clearly

22

left the provisions of the Constitution itself as the sole

source of qualifications” , Warren, op cit. at 422.18

Significantly, a constitutional amendment was appar

ently deemed necessary to exclude persons from Congress

who, contrary to their oath, had “ engaged in insurrection

or rebellion” or “ given aid or comfort to the enemies”

of the United States (Const., Amendment XIV, § 3).

It is reasonable to assume that the views of the dele

gates to the Federal Constitutional Convention were known

and accepted in Georgia. John Wilkes was strongly

supported in Georgia as elsewhere in the United States.19

The Georgia Convention of May 1789 adopted the state’s

second Constitution, some 16 months after Georgia had

ratified the federal Constitution, containing language

similar to that in the federal Constitution.20

The plain language of the Georgia Constitution, rein

forced by English and American constitutional history is

not refuted by the occasional partisan claims in Congress

to a greater power over qualifications. This is very dif

ferent from the administrative implementation of a statute

in which Congress by failing to amend is deemed to

acquiesce. Cf. United States v. Midwest Oil Co., 236 U. S.

459. For every claim of a legislative body’s power to fix

qualifications there is an equally firm claim to the contrary

18 The same conclusion was reached after a detailed study of the

convention proceedings. Note, The Right of Congress to Exclude its

Members, 33 Va. L. Rev. 322 (1947). Another commentator

relied upon by the court below concerning Congressional practice

(R. 146-47) agrees that “neither House may impose qualifications

additional to those that are mentioned” I Willoughby, The Con

stitution of the United States (2d ed. 1929) § 340.

19 See, e.g., McCall, History of Georgia (1816) II, 299-300.

20 Georgia’s first Constitution, that of 1777, contained a statement

of qualifications. Its second, that of 1789, was the first to authorize

the legislature to judge the “election, returns and qualifications” of

members.

and inconsistency of position by the most judicious of Sen

ators is not unknown.21 It is more significant that on a

subject so fraught with polities the attempt to impose extra

constitutional qualifications has been so rarely asserted.

The ‘ ‘ historical precedents ’ ’ cited by the court below are

illusory (E. 146). The Senate never decided the case of

Senator Bilbo who died before action could be taken. The

principal charge against him related to his conduct of his

election campaign, a legitimate subject of inquiry (see

Senate Election, Expulsion ancl Censure Cases from 1789 to

1960, S. Doc. No. 71, 87th Cong. 2d Sess., 142-143). As for

Senator Smoot, the Senate refused to exclude him “ for

alleged disqualifications other than those specified in the

Constitution”, id. at 97-98; even the attempt to expel him

failed.

The federal cases relied upon by the majority below are

equally inapposite (E. 145-148). Two of them, In re Chap

man, 166 TJ. S. 661, and Barry v. United States, 279 U. S.

597, involve the federal power of investigation. Wilson v.

North Carolina, 169 U. S. 586, involved a state governor’s

suspension of a state commissioner. Snoivden v. Hughes,

321 U. S. 1, did not involve a legislative imposition of new

qualifications, but a challenge of election results.22

The court below finally sought to find in the “ oath of

members” provision of the Constitution (Article III,

Section IV, Paragraph V) some authority for the action

of the House:

“ Each senator and representative, before taking

his seat, shall take the following oath, or affirmation,

21 See, for example, the views of Senators Taft and George on

the qualifications of Senator Langer, 88 Cong. Rec. 2859 (1942)

and Senator Bilbo, (93 Cong. Rec. 15, 16).

22 The single state court case cited by the majority was Hiss v.

Bartlett, 3 Gray 468 (1855), a case involving the broader right of

expulsion (R. 145).

24

to wit: ‘ I will support the Constitution of this State

and of the United States, and on all questions and

measures which may come before me, I will so con

duct myself, as will, in my judgment, he most con

ducive to the interests and prosperity of this State’.”

('§ 2-1605, Ga. Code Ann.)

Nothing in this oath authorizes the House to bar from

office a person who meets the qualifications of Article III,

Section VI, Paragraph I of the Constitution, and who is

not disqualified by the explicit provisions for disqualifica

tion. The Constitution requires an elected member to take

the oath before he takes his seat; it does not authorize his

fellow members to prevent him from taking the oath, which

is promissory in character and not a standard for judging

past conduct. There is nothing more subjective and hence

incapable of use as a test of qualifications than the agree

ment that the oath-taker will support the state and

federal Constitutions and that he will conduct himself

as will in his judgment “ be most conducive to the interests

and prosperity of this State. ’ ’

The determination of loyalty is not to be found in the

manipulation of this oath of office. The state Constitution

has made explicit provision elsewhere for such a determin

ation which disqualifies persons “ convicted in any court of

competent jurisdiction of treason against the state,” Arti

cle II, Section II, Paragraph I, infra, p. 48.

The attempt to turn the oath provision, a solemn ap

peal to the conscience of a member, into a qualification for

office is a plain distortion of language and of the purpose

of an oath of office. Constitutional questions aside, it

should be rejected, simply because words should be given

their plain meaning and not used to achieve purposes rad

ically different from those intended by the draftsmen.

Moreover, the construction adopted belowT does raise a

host of constitutional problems: vagueness (infra, p. 25),

25

effect upon the franchise (infra, p. 38), effect upon free

dom of speech (infra, p. 27) and the prohibition against

bills of attainder and ex post facto laws. These problems

are so familiar that, even before studying them closely,

the wisdom of Chief Judge Tuttle’s admonition is ev

ident : a court should first construe the statute with an eye

to the avoiding of the constitutional question if possible

(R. 166). See Kent v. Dulles, 357 U. S. 116; United States

v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41, 46.

P O I N T II

The oath provision of the Georgia Constitution, as

interpreted below, is unconstitutionally vague under

the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Georgia Constitution on its face contains an explicit

statement of (i) the qualifications of Representatives,23

(ii) disqualification after conviction of specific crimes and

of “ idiots and insane persons”,24 (iii) disqualification of

persons holding other state offices, receiving other state

benefits, or in default of their financial obligations.25 There

is nothing imprecise about any of these provisions.

But the court below as we have seen, supra, p. 23, has

found that there is an implicit qualification for office—

namely that a member-elect’s past conduct indicates that

he will support the state and federal Constitutions and

that “ on all measures which may come before me, I will

so conduct myself, as will in my judgment be most con

ducive to the interest and prosperity of this State.”

The Court below has changed the promissory oath into

a representation as to the past. As thus construed, the oath

23 Article III, Section VI, Paragraph I, infra, p. 47.

24 Article II, Section II, Paragraph I, infra, p. 48.

25 Article III, Section IV, Paragraph VI, infra, p. 48.

26

provision authorizes a legislative majority to evaluate

the oath-taker’s opinions, past behavior and public state

ments to determine whether he is capable of taking the

oath with sincerity. There are absolutely no standards

for this judgment by the legislature.

In Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278,

the Court doubted that the words “ aid, support, advice,

counsel or influence” to the Communist Party were “ sus

ceptible of objective measurement”, supra, at 285-286; con

versely, there is no more precision in evaluating Mr. Bond’s

“ support” of the Constitution. Indeed, a recent Georgia

legislature, whose members had taken this very oath, ac

cused this Court of treason for its decisions protecting con

stitutional rights. Interposition Resolution, (March 9, 1956)

H. R. 185, Georgia Laws 1956, No. 130, at 642.

Every legislator may have a different view as to

whether the past behavior of a colleague indicates that his

future behavior will ‘ ‘ support the Constitution of this State

and of the United States” . Further, a promise to “ conduct

myself as will in my judgment, be most conducive to the

interests and prosperity of this State” is no more precise

than the promise to “ promote . . . undivided allegiance to

the government of the United States” which this Court held

invalid in Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360.

It is apparent that the measuring rod found by the

court below in the constitutional oath of office is vague

enough when applied to conduct. It becomes absolutely

meaningless when it is applied to public expressions of opin

ion, which are protected by the First Amendment, as the

court below recognizes in the case of the ordinary citizen

(R. 151). Where an oath “ abut[s] upon sensitive areas of

basic First Amendment freedoms” the vice of unconsti

tutional vagueness is aggravated since, as applied here, it

would require all candidates for office to eschew clearly

lawful activities. Baggett v. Bullitt, supra, at 372.

27

P O I N T I I I

Mr. Bond’s exclusion from elected legislative office

solely because o f his opinions and public statem ents

on national issues violated the guarantee o f freedom

of speech and his privileges and immunities under the

First and Fourteenth A m endm ents.

Mr. Bond was denied his seat because of his public ex

pression of opinion on domestic and foreign affairs. This

is manifest from the charges filed against him (R. 13-20)

and from the hearings in the committee and the House

(R. 28-99). This action, endorsed by the court below,

strikes at the First Amendment’s imperative of a govern

ment based upon the consent of an informed citizenry.

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536, 552; Stromberg v.

California, 283 U. S. 359; New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,

376 U. S. 254, 270; Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U. S.

64; DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 365; Terminiello v.

Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 4; Whitney v. California, 274 U. S.

357, 375; United States v. C. I. 0., 335 U. 8. 106.

This Court has recognized the importance to the public

of securing information and knowledge in a wide variety of

cases involving travel (Kent v. Dulles, 357 U. S. 116;

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U. S. 500), freedom

to receive information through the mail (Lamont v. Post

master General, 381 U. S. 301), newspaper commentaries

and advertisements (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,

supra), criminal libel against public officials (Garrison v.

Louisiana, supra), immunity of government officials from

libel (Barr v. Matteo, 360 U. S. 564) and the arts and litera

ture (Kingsley Pictures Corp. v. Regents, 360 U. S. 684).

These cases have emphasized the central meaning of the

First Amendment, namely,

“ the profound national commitment to the principle

that debate on public issues should be uninhibited,

robust, and wide open, and that it may well include

vehement, caustic and sometimes unpleasantly sharp

attacks on government and public officials.” Neiv

York Times Co. v. Sullivan, supra, at 270.

The exclusion from office of Mr. Bond cannot be squared

with the principle that “ the censorial power is in the peo

ple over the Government, and not in the Government over

the people,” 4 Annals of Congress 934 (1794) quoted by

Mr. Justice Brennan in The Supreme Court and- the Meikle-

john Interpretation of the First Amendment, 79 Harv. L.

Rev. 1, 15.

The SNCC statement was a vigorous criticism of

American foreign and domestic policy. It was entitled to

constitutional protection regardless of whether or not one

agrees with it. As Professor Meiklejohn says, “ The vital

point . . . is that no suggestion of policy shall be denied a

hearing because it is on one side of the issue rather than

another. . . . These conflicting views may be expressed, must

be expressed, not because they are valid, but because they

are relevant,” Meiklejohn, Political Freedom, 26-28 (1948).

And in Kingsley Pictures Corp. v. Regents, supra, at 688-89,

Mr. Justice Stewart stated:

“ It is contended that the State’s action was justi

fied because the motion picture attractively portrays

a relationship which is contrary to moral standards,

the religious precepts, and the legal code of its citi

zenry. This argument misconceives what it is that

the Constitution protects. Its guarantee is not con

fined to the expression of ideas that are conventional

or shared by a majority. It protects advocacy of the

opinion that adultery may sometimes be proper, no

less than advocacy of socialism or the single tax.

And in the realm of ideas it protects expression which

is eloquent no less than that which is unconvincing. ’ ’

The First Amendment protection given to the SNCC

statement is enhanced by the fact that it related to the

functioning of the federal government. This is a subject

29

upon which the citizens’ views are protected also by the

privileges and immunities clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Such is the teaching of Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall.

(73 TJ. S.) 36; The Slaughterhouse Cases, 16 Wall. (83

U. S.) 36, 79, and Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U. S. 496. In United

States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542, 552, this Court said:

“ The right of the people peaceably to assemble

for the purpose of petitioning Congress for a redress

of grievances, or for anything else connected with

the powers or the duties of the National Government,

is an attribute of national citizenship and, as such,

under the protection of and guarantied by, the United

States.”

This was applied in Hague v. C .1.0., supra, at 512 where

the Court held that

“ freedom to disseminate information concerning the

provisions of the National Labor Relations Act, to

assemble peaceably for discussion of the Act, and

of the opportunities and advantages offered by it, is

a privilege or immunity of a citizen of the United

States secured against State abridgement by Sec

tion 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment . . . ”

The opinion below does not challenge the constitutional

right of SNCC to make the statement. Rather, it empha

sizes the fact that Mr. Bond “ was more than a private

citizen; he was an officer and employee of SNCC and was

about to become a member of the House of Representatives

of Georgia” (R. 152). The court below was of the opinion

that an elected member of the House was entitled to less

constitutional protection than the average citizen. Under

lying the opinion is the unarticulated view that Mr. Bond’s

elected position imposed upon him the obligation to sup

port “ national policy” or to be restrained in his criticism

of it.

This is a conception of second class citizenship for a

legislator, totally without support in logic or in the con-

30

stitutional history of legislative bodies. It is completely

inconsistent with the duty which the office itself imposes

upon the incumbent to engage in a continuing dialogue on

public affairs with his constituents. This court has repeat

edly recognized the critical importance of exposing the

views and conduct of government officials to the view of

their constituents and the public at large, New York Times

Co. v. Sullivan, supra; Garrison v. Louisiana, supra.

The argument of the court below was rejected by this

Court in Wood v. Georgia, 370 U. S. 375, where a sheriff

was held in contempt for issuing a press release criticizing

a judge’s charge to a grand jury. The State had argued

that “ because the petitioner is sheriff of Bibb County and

therefore owes a special duty and responsibility to the

court and its judges, his right to freedom of expression

must be more severely curtailed than that of an average

citizen.” (Id. at 393.) The Court’s response was:

“ The petitioner was an elected official and had

the right to enter the field of political controversy,

particularly where his political life was at stake.

Cf. In re Sawyer, 360 U. S. 622. The role that elected

officials play in our society makes it all the more

imperative that they be allowed freely to express

themselves on matters of current public importance.”

Id. at 394-95.

The court below also assumed that freedom of speech

is solely for the benefit of the speaker. The contrary is of

course true; indeed, the larger interest is that of the public,

Lamont v. Postmaster General of the United States, supra;

Martin v. City of Struthers, 319 U. S. 141, 143. There is a

“ paramount public interest in a free flow of information to

the people concerning public officials, their servants. To

this end, anything which might touch on an official’s fitness

for office is relevant” , Garrison v. Louisiana, supra. If

aspirants for public office are to be discreetly silent, how

can the people intelligently “ discuss the character and

qualifications of candidates for their suffrage” , Coleman

31

v. MacLennan, 78 Kan. 711, 724 (1908), quoted in New York

Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 281.

The lower court’s novel distinction between the rights of

a citizen and those of a legislator led it to disregard the

established principles applicable to the First Amendment.

Thus, it began by stating that First Amendment rights

could he impaired constitutionally “ in the context of two

fundamental principles of government: separation of pow

ers and state government under our system of federalism”

(R. 142). But there is no logical connection between “ fed

eralism” and the need to restrict speech. The First Amend

ment protects speech whatever the source of limitation:

federal legislation, Lamont v. Postmaster General, supra,

a state legislative body, Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354

U. S. 234, a state judge, Garrison v. Louisiana, supra or

a state criminal prosecution, Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380

U. S. 479.

Nor is there, any logical connection between the separa

tion of powers doctrine and the need to restrict freedom

of speech. That doctrine is not violated when the judicial

branch protects First Amendment rights against impair

ment by either of the other two branches of state govern

ment. See, e.g., Stveezy v. New Hampshire, supra.

The Court below further deviated from the now estab

lished method of testing the impairment of First Amend

ment rjghts when it applied what it called a “ rational evi

dentiary basis test” (R. 151). For it treated this case as

if it involved, not the freedoms of speech and franchise,

but the regulation of business or property calling for

deference to the legislative judgment (R. 150). But this

is a case involving both freedom of speech and of franchise

(infra, p. 38). It directly affects the “ vitality of civil and

political institutions in our society” , Terminietto v. Chicago,

337 U, 8. 1, 4, and the rights of the appellants and the

public are not subject to so narrow a test.

32

When the rational evidentiary basis test was applied in

1938 to a purely economic issue, Mr. Justice Stone inti

mated in a famous footnote the distinction between eco

nomic regulation and the restriction of First Amendment

rights, United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304 U. S.

144, 152, n. 4. This was fully articulated by Mr. Justice

Jackson’s opinion five years later in West Virginia State

Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624, 639:

“ In weighing arguments of the parties it is im

portant to distinguish between the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment as an instrument for

transmitting the principles of the First Amendment

and those cases in which it is applied for its own

sake. The test of legislation which collides with the

Fourteenth Amendment, because it also collides with