Appeals Court Hears Detroit Housing Bias Base

Press Release

April 20, 1955

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Appeals Court Hears Detroit Housing Bias Base, 1955. 5b7e0209-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b69cec2d-2ac9-4d72-a9a7-e1ca4d4b9f69/appeals-court-hears-detroit-housing-bias-base. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

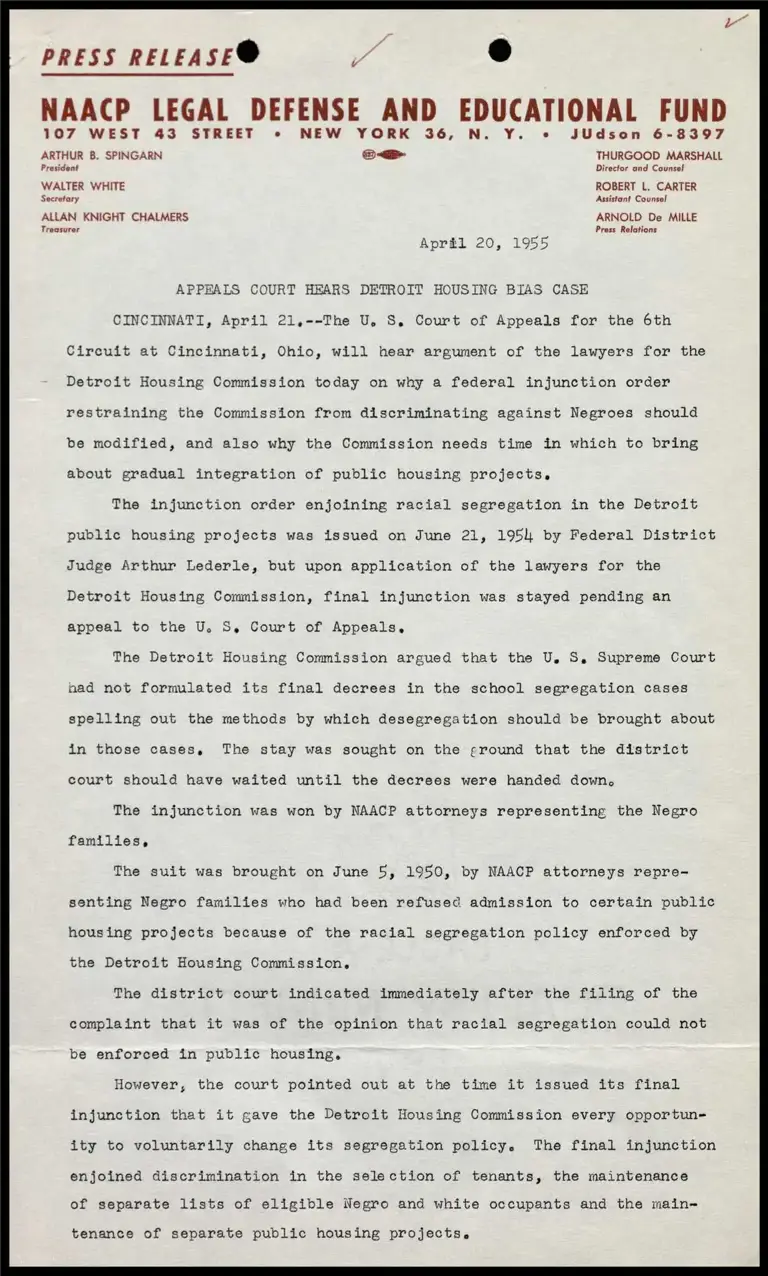

PRESS RELEASE® ed e

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET *+ NEW YORK 36, N. Y. © JUdson 6-8397

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN oa THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director and Counsel

WALTER WHITE ROBERT L. CARTER

Secretary Assistant Counsel

ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS ARNOLD De MILLE

Treasurer Press Relations

Aprtl 20, 1955

APPEALS COURT HEARS DETROIT HOUSING BIAS CASE

CINCINNATI, April 21,--The U, S, Court of Appeals for the 6th

Circuit at Cincinnati, Ohio, will hear argument of the lawyers for the

Detroit Housing Commission today on why a federal injunction order

restraining the Commission from discriminating against Negroes should

be modified, and also why the Commission needs time in which to bring

about gradual integration of public housing projects,

The injunction order enjoining racial segregation in the Detroit

public housing projects was issued on June 21, 195) by Federal District

Judge Arthur Lederle, but upon application of the lawyers for the

Detroit Housing Commission, final injunction was stayed pending an

appeal to the U. S. Court of Appeals,

The Detroit Housing Commission argued that the U. S, Supreme Court

nad not formulated its final decrees in the school segregation cases

spelling out the methods by which desegregation should be brought about

in those cases, The stay was sought on the ¢round that the district

court should have waited until the decrees were handed down.

The injunction was won by NAACP attorneys representing the Negro

families,

The suit was brought on June 5, 1950, by NAACP attorneys repre-

senting Negro families who had been refused admission to certain public

housing projects because of the racial segregation policy enforced by

the Detroit Housing Commission.

The district court indicated immediately after the filing of the

complaint that it was of the opinion that racial segregation could not

be enforced in public housing.

However, the court pointed out at the time it issued its final

injunction that it gave the Detroit Housing Commission every opportun=

ity to voluntarily change its segregation policy. The final injunction

enjoined discrimination in the selection of tenants, the maintenance

of separate lists of eligible Negro and white occupants and the main-

tenance of separate public housing projects.

In 1952, following a preliminary hearing in the case, the Commis-

2

sion adopted a resolution which purported to do away with the racial

segregation policy in public housing. Pursuant to this resolution, two

new public housing projects which opened in Detroit since 1952, the

Douglass Homes and the Jeffries Homes, have been integrated and a third

project presently under construction is designated for interracial

occupancy. However, four older permanent projects remain segregated.

With respect to integration of these older projects, the Detroit

Housing Commission contends that it is necessary to first condition

both the adult occupants of public housing and the home owners in areas

surrounding public housing units, Such conditioning is more difficult

and more acute in housing than in schools where the integration of

children alone is involved, the Commission argued.

NAACP attorneys argue that it is not necessary to grant time in

which to integrate since integration in public housing is necessarily

gradual, Eligible Negro families cannot be admitted to vacancies in

white projects any faster than vacancies occur in these projects.

The attorneys argue that the district court has already allowed the

Detroit Housing Commission four years in which to integrate, They say

also that the district court has given consideration to the possibility

of racial conflicts arising from integration of public housing projects

and from his personal knowledge of the situation has concluded that race

relations in Detroit have advanced to the point where it is apparent

that Negroes are able to move not only into white projects without fric-

tion, as in the case of Douglas and Jeffries Homes, but are also able to

move into formerly all-white private residential areas without conflict,

Attorneys for the Negro families in this case are Thurgood Marshall

and Constance Baker Motley of NAACP Legal Defense staff in New York,

and Francis M. Dent, Willis M. Graves and Edward Turner of the Detroit

Branch of the NAACP,

=30—