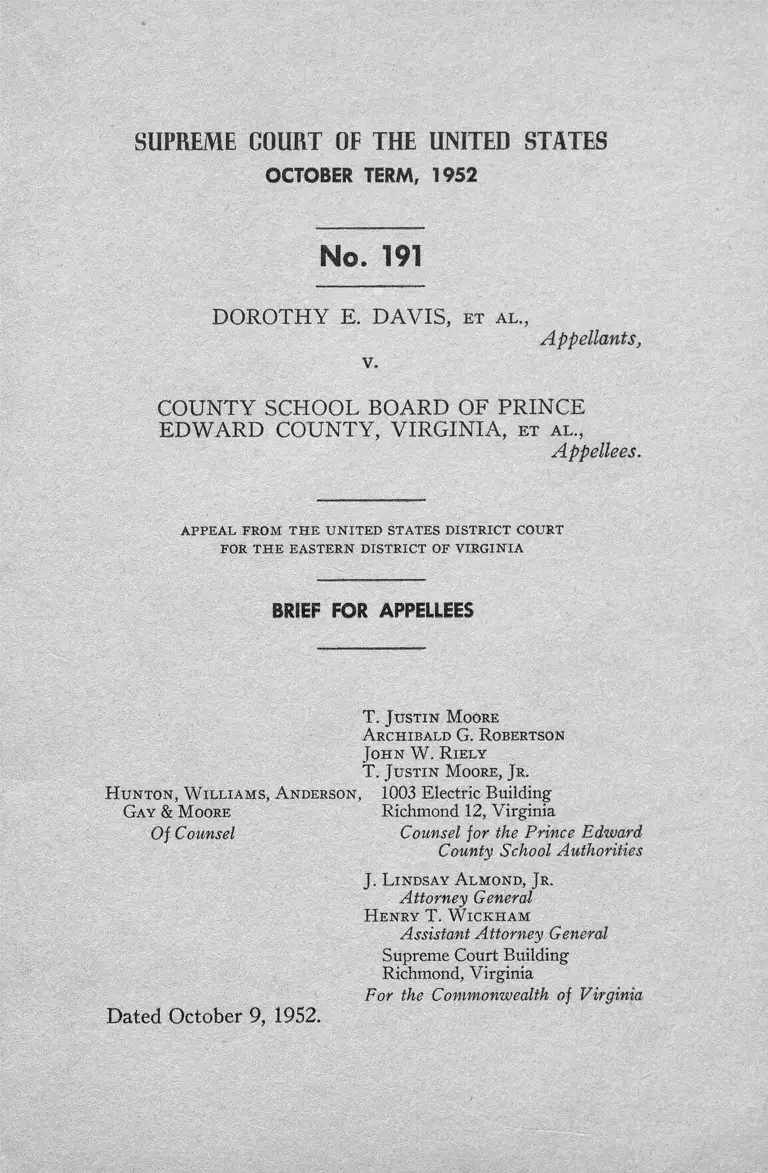

Davis v. Prince Edward County, VA School Board Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 9, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Prince Edward County, VA School Board Brief for Appellees, 1952. 42b99a40-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b6b1c061-aa6f-43e4-ae3a-f5fe82d8e780/davis-v-prince-edward-county-va-school-board-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1952

No. 191

D O R O TH Y E. D AVIS, et a l „

Appellants,

v.

CO U N TY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE

E D W A R D COU N TY, VIRG IN IA , et a l „

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

T. Justin M oore

A rchibald G. Robertson

John W . R iely

T. Justin M oore, Jr.

H untqn, W illiams, A nderson, 1003 Electric Building

Gay & M oore Richmond 12, Virginia

Of Counsel Counsel for the Prince Edward

County School Authorities

J. L indsay A lmond, Jr.

Attorney General

H enry T. W ickham

Assistant Attorney General

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

For the Commonwealth of Virginia

Dated October 9, 1952.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. Preliminary Statement ..................................................... 1

II. O pinion Be l o w ..................................... .................................- 2

III. Jurisdiction ......... 2

IV. Q uestions Presented .............................................................. 2

V. Constitution and Statute Concerned............................ 3

VI. Statement of the Ca s e ....................................................... 3

1. The Parties ........................... -................ -.............................. 3

2. The Locale and Its Schools............................ .................... 4

3. The Su it.................................................................................. 5

4. The Trial ................ 6

5. The Decision ..................... .................................................... 7

VII. Summary of A rg u m en t ........................................................ 8

V III. A rgument ......................................................................... -...... 12

A. Segregation Does Not of Itself Off end the Constitution .. 12

1. Introduction..........................—...........-........................... 12

2. The Guiding Legal Principles.................................. —- 12

3. The Virginia Background ........................................... 17

4. The Psychological Issue — .................- ......— ............. 21

5. The Effect of Amalgamation.......... ............................... 29

6. Conclusion .... ........... ....................... ............................. - 32

B. The Constitution Does Not Require Precipitate Action .. 33

1. The Issue.......................................................................... 33

2. The Facts.......................................................................... 34

3. The Wisdom of the Court B elow ......... ........................ 36

IX. Conclusion 39

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Briggs v. Elliott, 98 F. Supp. 529 (E.D.S.C. 1951) .................. 28, 37

Carr v. Corning, 182 F. 2d 14 (App. D. C. 1950) ...................... 12, 22

Corbin v. County School Board, 177 F. 2d 924 (4th Cir. 1949) ..... 34

Cumming v. Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528 (1899) .................. 37

Eccles v. Peoples Bank, 333 U. S. 426 (1948) .......................... 11, 36

Gebhart v. Belton,..... Del......... , ......A. 2 d ....... (Sup. Ct., August

28, 1952) ................................................................. ........................ 37

Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464 (1948) ................. ................... 9, 16

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927) .......................... .......... 8, 14

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th Cir. 1951), cert,

denied 341 U. S. 951 (1951) ....................................................... 29

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 (1950) .... 9, 15

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) ........ 8, 15

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896) .................... 8, 9, 13, 15

Railway Express Agency, Inc. v. New York, 336 U. S. 106 (1949)

9, 16

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ............................................. 13

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 (1938) ..................... 8, 15

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) .............................. 9, 15, 28

Tigner v. Texas, 310 U. S. 141 (1940) ......................................... 9, 16

CONSTITUTIONS AND STATUTES

28 U. S. C. § 1253 ...................... 2

28 U. S. C. § 2101(b) ................................. 2

28 U. S. C. §2281 .................................................................................. 4

Constitution of Virginia (1902), §1 4 0 ................ 3

Constitution of Virginia (1869), Art. V I I I ...................... 18

Virginia Code (1950), §22-221 ........................................................... 3

Acts of Assembly of Virginia:

1952, p. 1258.......................... ........................................................... 20

1952, p. 1262........................ ............ ................................................. 19

1950, ch. 1 4 ........................................................................................ 19

PRELIM INARY STATEMENT

I.

This case presents to the Court for decision the forth

right contention that segregation of the races in high

school is unconstitutional even though the facilities for

the education of both races are as equal as they can be

made. Two companion cases1 present substantially the

same contention. In each, the Court is asked to overrule

established authority and to outlaw the fixed policies of

the several States which are based on local social condi

tions well known to the respective legislatures. The con

tention is based on a proposal to revise the established inter

pretation of the Fourteenth Amendment and on testimony

given in disregard of the way of life in the localities con

cerned.

The Appellants, who were plaintiffs below, assert also

that, even if their primary contention fails, a court of

equity must require immediate amalgamation of the

schools even though substantial equality of education now

exists in all respects except as to a school building and

even though a new school building, better than that of the

whites, will be in use when the next school year begins.

They urge a strange contradiction: the application in

equity of a harsh and unyielding rule to be applied without

discretion.

These cases, therefore, present questions of immediate

importance to great numbers of persons in a field where

science is not yet reliable and individual feeling is strong.

1No. 8, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, and No. 101,

Briggs v. Elliott.

2

II.

O P IN IO N BELO W

The opinion of the three-judge District Court below (R.

617-23) is reported in 103 F. Supp. 337.

III.

JU R ISD IC T IO N

The final decree of the Court below was filed on March

7, 1952 (R. 623). The Petition for Appeal was filed on

May 5, 1952 (R. 625).

The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U. S. C. §1253

and2 8 U. S. C. §2101 (b ).

IV .

Q U E S T IO N S PRESENTED

The questions presented are tw o :

1. Where equality exists between high schools for

white and Negro as to all physical and essential ele

ments, including buildings, equipment, transporta

tion, curricula, quality of instruction and the like, and

where the Court below has found as a fact that the

evidence does not show that separate education is

harmful to either race, does the Fourteenth Amend

ment require this Court to strike down Virginia’s

laws which for 80 years have provided for segregated

education?

2. Where equality now exists between high

schools for white and Negro as to all elements except

the building and where the Court below has found as

a fact that local and State authorities are moving

with speed to complete a new building for the Negro

which, the evidence shows, will be completed before

3

the next school session begins, does a court of equity

lack the discretion to refrain from requiring imme

diate interracial schooling?

W e submit that both of these questions should be

answered in the negative.

V .

C O N S T IT U T IO N A N D ST A T U T E CO N CER N ED

The Appellants seek, in the circumstances of this case,

to invalidate Section 140 of the Constitution of Virginia

and Section 22-221 of the Code of Virginia of 1950, as

follow s:

“ §140. Mixed schools prohibited.— White and col

ored children shall not be taught in the same school.”

“ §22-221. White and colored persons.— White and

colored persons shall not be taught in the same school,

but shall be taught in separate schools, under the

same general regulations as to management, useful

ness and efficiency.”

V I.

ST A T E M E N T OF TH E CASE

1.

The Parties

The Appellants are Negro pupils of high school age (or

their representatives) living in Prince Edward County,

Virginia. The Appellees are the school authorities of the

County and the Commonwealth of Virginia which inter

vened below in support of the validity of its Constitution

and the statute under attack.

4

2.

The Locale and Its Schools

Prince Edward is a small county in south-central V ir

ginia (R. 303). Its population is about 15,000. Almost one-

third of these live in Farmville, the only incorporated

community (R. 362). Roughly half of the population is

white and half Negro (R. 305). The County is poor; it

ranks among the lowest fifth of Virginia counties in aver

age wealth per school child (R. 432; D. Ex.2 94).

There are 3 high schools in the County (R. 56, 361).

Two are for white children and 1 for Negro. The white

schools are Farmville, in the town on the northern bound

ary of the County, and Worsham located near the geo

graphical center of the County (R. 361).3 The Negro

school is Moton now located in Farmville (R. 82). White

children attend either Farmville High School or Worsham,

according to their place of residence; all the Negro chil

dren attend Moton (R. 57). In 1951, 405 children were

enrolled at the 2 white schools and 463 were enrolled at

Moton (D. Ex. 102).

These enrollment figures have shown a complete change

in relationship in a very short period of time. In 1941, only

10 years before, there were more than twice as many white

high school students as there were Negro. The figures

were 540 white and 208 Negro. It was only in 1947 that

the Negro students equalled the white in number (D. Ex.

102).

Faced with this upsurge in Negro enrollment, the local

authorities did everything possible to keep up with the

tide. A survey of school needs by State authorities was

2 Exhibits introduced by the Appellees are referred to as D. E x.......

3Worsham is a small school combining- elementary and high school

grades admittedly inferior to Farmville (R . 59; D. Ex. 97).

5

instituted by the local board in 1947 just after the war

(R. 293). Since immediate permanent building was impos

sible, two temporary buildings were erected at the Negro

school (R. 295). Later another was added (R. 296). These

doubled the available floor space (R. 146). In 1949, an

overall school building plan was adopted with a new

Negro high school given first priority (R. 297-8).

Construction of a proper Negro high school out of cur

rent funds was beyond the financial ability of the County.

Two alternatives were possible. The first was a loan from

the State Literary Fund. But in 1949 and 1950 that was

impossible for all the money in that fund had already been

allocated to loans (R. 298-9). The School Board then

planned to follow the other alternative, a bond issue

requiring approval by the voters. This program was

pushed along as rapidly as possible (R. 303-4). In the

meantime, a site for the new school was selected and

proceedings for its acquisition initiated (R. 301).

The Negro pupils, however, blocked this attempt at

financing by a 2-week strike (R. 304-5) which their princi

pal testified that he was unable to control (R. 134, 147). The

local authorities persisted, however, in their efforts at fi

nancing and by June, 1951, had obtained all the funds

required for the construction of the new Negro high school

(R. 309-10; D. Ex. 4).

3.

The Suit

The Appellants, however, disregarding the substantial

efforts of the School Board in their behalf, filed their

lengthy complaint in this suit in May, 1951. In essence,

the complaint asserted that facilities for the Negro pupils

were not equal to those for the white and that, even if

6

they were, segregated education was per se unconstitu

tional (R. 1-30).

The Appellees promptly filed their answer and admitted

that the school facilities were inferior, but pointed to their

building program which “ is under way” and will result in

equal facilities “ as rapidly as can be done” (R. 33). Since

the case was of State-wide or, as the Court below noted

(R. 44), even broader importance, the Commonwealth

intervened as a defendant and is now here as an Appellee.

4.

The Trial

The trial was before a specially constituted District

Court of 3 judges as required by 28 U. S. C. §2281. Evi

dence and argument were heard for the 5 days, February

25-29, 1952.

The Appellants produced two types of evidence. First,

they presented testimony as to physical inequalities among

the 3 high schools. This was done through photographs,

statistics and a survey by an educator. They rested their

main case on the evidence of an educator and 3 psycholo

gists, none of whom had ever been in Prince Edward County,

but all of whom testified that educational segregation is, in

the abstract, bad.

The evidence for the Appellees related directly to the

setting in which this case is presented. It first disclosed

the history and background of education in Prince Edward

County. This was followed by a survey of present condi

tions and an explanation of future plans. Next, since this

case is primarily an attack upon segregated education

throughout the Commonwealth, a similar review was

given to the Court as to Virginia as a whole. Finally, the

7

Court was offered the views of educators, psychologists

and a psychiatrist that, in the circumstances existing in

Virginia and in Prince Edward County, education of the

races in separate high schools is better for the Negro and

the white.

5.

The Decision

On the first question here presented, the Court below

was very clear in its decision. Two bases were found.

First, the Court held that, as a matter of law, separate

education is not unconstitutional. Its words w ere:

“ . . . Federal courts have rejected the proposition, in

respect to elementary and junior high schools, that

the required separation of the races is in law offensive.

. . . W e accept these decisions as apt and able prece

dent.” (R. 619)

Secondly, and perhaps more important, the Court found,

as a matter of fact, that separate education did not con

stitute discrimination. Its words were :

. . the facts proved in our case . . . potently demon

strate why nullification of the cited sections is not

warranted.. . . ” (R. 619)

“ . .. we cannot say that Virginia’s separation of white

and colored children in the public schools is without

substance in fact or reason. W e have found no hurt

nor harm to either race.” (R. 621-2)

W e ask this Court’s particular attention to that finding.

Unlike the two companion cases, where little expert evi

dence was available to the defendants, here the factual

8

case for segregation was fully presented by experts and

the Court below found as a fact that segregation caused

no harm.

On the second issue, the Court found that disparity

extended beyond buildings and equipment. It found

inequality to exist also as to curricula and transportation.

It restrained continued inequality in these fields at once.

It ordered the Appellees to proceed with diligence to

complete the new Negro high school which will be ready

by September, 1953. It refused further relief:

“ Both local and State authorities are moving with

speed to complete the new program. An injunction

could accomplish no more.” (R. 623)

A final decree was entered accordingly and from that

decree this appeal was taken.

V II.

S U M M A R Y OF A R G U M E N T

A.

Segregation Does Not of Itself Offend the Constitution

Segregation in education existed at the time when the

Fourteenth Amendment was adopted and had the approval

o f the Congress that submitted the Amendment and a

majority of the States in the Union at the time of its ratifica

tion. Thereafter it was approved by this Court in Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896), and Gong Lwn v. Rice,

275 U. S. 78 (1927). Later decisions of this Court are

not in point, since they concern either situations where the

State provided no instruction for the Negro but did so for

the white ( Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337,

1938; Sipuel v. Board o f Regents, 332 U. S. 631, 1948), or

9

situations where the Court found factual inequality to exist

in circumstances which do not exist here ( McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637, 1950; Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 1950).

The equal protection of the laws requires only that the

State be reasonable in establishing the classifications in

which its policy is to function. If Plessy v. Ferguson is to

be re-examined, principles established by this Court for the

equal protection determination must be followed. These

include a consideration of the significance of the historical

background (Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464, 1948) and

of the practical setting in which the case arises ( Tigner v.

Texas, 310 U. S. 141, 1940; Railway Express Agency, Inc.

v. New York, 336 U. S. 106,1949).

For this purpose, Virginia history and present Virginia

conditions are important. The basic historical facts are so

familiar as not to require repetition. In education, Virginia

lagged until 1920 but has since made great strides, high

school enrollment having increased 5 times. Fifteen years

ago, education for the white was better than for the Negro.

For example, salary scales and average teacher training then

were lower for the Negro ; now salaries are equal and aver

age Negro teacher training is higher. Increasing sums are

being spent on schools, a larger proportionate amount going

for the Negro.

School facilities for the Negro equal the white in half of

Virginia’s school districts and are better in one quarter.

Future construction plans are large with more to be spent

for the Negro than his proportionate share.

These facts indicate that the Virginia people overwhelm

ingly believe that segregated education is proper, are willing

to provide equality and are completely prepared to bear the

burdens o f a dual school system.

The evidence of the Appellants disregards this Virginia

10

background. It is presented by experts unfamiliar with

Virginia conditions or even, in general, with conditions

existing in any segregated State. It is not based on sound

scientific knowledge; their purported scientific “ tests” are

obviously unreliable. Constitutional determinations cannot

be based on speculations which, they admit, are “ on the

frontiers of scientific knowledge.”

On the other hand, the Appellees presented testimony of

witnesses at least equally expert and, in addition, o f broad

experience not only in Virginia but throughout the nation.

Their conclusions are that, with conditions in Virginia as

they are today, school amalgamation would do harm to the

children of both races. They are firm in their views that the

Negro high school child is better off in his own school than

he would be in a mixed school. They point out that the high

school level, with children not yet mature and the influence

of parents strong, involves entirely different considerations

from those at the graduate or professional level.

High school amalgamation would bring on further dif

ficulties. All administrative opinion was that Virginia

schools would deteriorate due to reduced financial support.

Furthermore, the opportunities o f Negro teachers for

employment would be drastically reduced.

In the light of all these facts, the Court below found that

segregation in Virginia high schools was not “ without sub

stance in fact or reason.” Its finding of fact was that segre

gation caused “ no hurt or harm to either race.” Its conclu

sions were amply justified by the evidence of record and

should be affirmed.

B .

The Constitution Does Not Require Precipitate Action

This is a narrow issue. The Court below ordered the

Appellees to equalize curricula and transportation; that has

11

been substantially accomplished and, if the Appellants have

any complaint, it should be addressed to the Court below

which is fully equipped to enforce its decree.

The Court below also ordered the Appellees to proceed

as quickly as possible with their plans to equalize buildings

and facilities. The Appellants urge that, since the building

will not be ready until after the end of the present school

session, this Court should as a matter of law order amalga

mation now in the middle of a school session, although

segregation would then be required next year. As a sub

sidiary argument, they urge that the Court below would have

such difficulty enforcing any equalizing decree that segrega

tion should be outlawed.

A new Negro high school building is in the course of

construction in the County. It will provide better facilities

than any provided for the white. It w'ill be ready for

occupancy by September, 1953.

The contention of Appellants violates fundamental equita

ble principles (Eccles v. Peoples Bank, 333 U. S. 426, 1948).

I f adopted, it would mean chaos in the County schools, just

for the remainder of this school session. It would hurt the

children of both races and help no one. The Constitution

does not require such fruitless action.

The decree of the Court below is now being given substan

tial compliance. There is nothing to indicate impossibility

of enforcement. It is only when that is indicated that the

Appellants may seek to destroy segregation on this novel

ground.

The determination of constitutional limitations is a prac

tical matter. The Court below acted wisely. The Appellants

have no cause for complaint.

12

A R G U M E N T

A.

Segregation Does Not of Itself Offend the Constitution

1 .

I ntroduction

The issue so sharply presented to the Court in this case

has come before it so often in recent years that the Court

is quite familiar with the authoritative decisions. The Appel

lants have pitched their case to a minor degree on the due

process of law provision of the Fourteenth Amendment; but

that is not a serious contention: they seek primary support

in the clause requiring equal protection of the laws. W e shall

look first to the specific authorities and then briefly at guid

ing principles which this Court has held, without variance,

to control the equal protection determination. With those

principles in mind, we shall review the factual setting in

Virginia and expert opinion based on those facts to show

that segregation at the high school level provides equal pro

tection. For it is only when the whole picture is viewed that

the Court may reach a conclusion as to the constitutional

reasonableness of the State action.

2.

T h e G u id in g L egal P r in c iple s

The Congress that submitted the Fourteenth Amendment

to the States enacted laws dealing with segregated schools in

the District o f Columbia (where, under the scrutiny of

Congress, segregated education still exists).4 A majority

of the States in the Union when the Amendment was ratified

4See Carr v. Corning, 182 F. 2d 14, 17-18 (App. D. C. 1950).

VIII.

13

had segregated schools. It is inconceivable that, at that time,

a serious contention could have been made that the Amend

ment outlawed segregated schools.

These precedents are important. As the Chief Justice said

in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) :

“ The historical context in which the Fourteenth

Amendment became a part of the Constitution should

not be forgotten.” (p. 23)

But they have been presented so often to this Court and are

so ably presented now5 that no detail is required here. Nor

need we dwell long on the cases decided by this Court relating

directly to the issue.

It is idle to say that Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537

(1896), does not support the position of the Appellees here.

The Court’s opinion there gives direct support here:

“ The most common instance of [laws requiring segre

gation] is connected with the establishment o f separate

schools for white and colored children, which has been

held to be a valid exercise of the legislative power even

by courts o f States where the political rights of the

colored race have been longest and most earnestly

enforced.” (p. 544)

Indeed, the Court then faced and decided the fundamental

issues that this case presents. The exact contentions made

by the Appellants here, such as the “ badge of inferiority”

argument, were presented to this Court in that case. But

this Court dismissed those contentions in language as apt

now as it was 50 years ago:

“ W e consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s

argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced

separation of the two races stamps the colored race with

*Brief for Appellees, Briggs v. Elliott, No. 101, pp. 15-16.

14

the badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason

of anything found in the act, but solely because the

colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.

The argument necessarily assumes that if, as has been

more than once the case, and is not unlikely to be so

again, the colored race should become the dominant

power in the state legislature, and should enact a law

in precisely similar terms, it would thereby relegate the

white race to an inferior position. W e imagine that the

white race, at least, would not acquiesce in this assump

tion. The argument also assumes that social prejudices

may be overcome by legislation, and that equal rights

cannot be secured to the negro except by an enforced

commingling of the two races. W e cannot accept this

proposition. If the two races are to meet on terms of

social equality, it must be the result of natural affinities,

a mutual appreciation of each other’s merits and a

voluntary consent of individuals.” (p. 551)

It is equally idle to say that Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S.

78 (1927), provides no support for the Appellees. The Court

there said:

“ The question here is whether a Chinese citizen of

the United States is denied equal protection of the laws

when he is classed among the colored races and fur

nished facilities for education equal to that offered to

all.........we think that it is the same question which has

been many times decided to be within the constitutional

power of the state legislature to settle without interven

tion of the federal courts under the Federal Constitu

tion.” (pp. 85-6)

Nor are the cases relied on by the Appellants in point.6

«The cases cited by the Appellants on pp. 9-11 of their Brief are

irrelevant to the determination to be made here. They concern situa

tions where the parties seeking relief were wholly denied the right in

question without being afforded “ separate but equal” treatment. Where

coordinate facilities or opportunities are provided, different considera

tions must be taken into account to reach the proper result.

15

Where the State has provided no facilities for the Negro in

a certain field of instruction, he is entitled to admission to

the institution in his State offering that instruction to the

white. That is all that was decided in Missouri ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938), and Sipuel v. Board of

Regents, 332 U. S. 631 (1948). McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 (1950), was a case of manifest

harshness, and the facts there presented provide adequate

distinction here. Only in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629

(1950), was the issue presented here to any degree raised,

and that case is no authority here for two reasons: first, as

we shall show below, the considerations relative to education

at the graduate level are entirely different from those bearing

on the high school, and secondly, the Court there found

inequality because of circumstances which have no substan

tial bearing here and, having found inequality, did not

. “ . . . reach petitioner’s contention that Plessy v. Fergu

son should be reexamined in the light of contemporary

knowledge respecting the purposes of the Fourteenth

Amendment and the effects of racial segregation.” (p.

636)

The contention that the petitioner made there, the Appel

lants make here. To uphold their assertion that segregation

at the high school level is unconstitutional purely on psycho

logical grounds would be to hold that equality can never be

attained. The doctrine of “ separate but equal” would lose all

force. Plessy v. Ferguson would not only be re-examined; it

would be effectively overruled.

W e assert that the doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson has

today the vitality here that it had 50 years ago. W e believe

its doctrine sound. W e believe that it will withstand re-exam-

ination. But if it is to be re-examined, that should be done

16

in the light of the guiding principles which this Court has

established to determine what is the equal protection o f the

laws.

The equal protection o f the laws does not mean that all

men at all times must receive the same treatment. The State

is entitled to protect its people against the lunatic and the

leper. One basic standard is established: if, in making its

classifications, the State acts reasonably, its action meets

the constitutional test.

The difficulties of application come with the determination

of reasonableness. But 2 rules are clear. As Mr. Justice

Frankfurter has said:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment did not tear history up

by the roots. . . .” (Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464,

465, 1948)

Thus the historical background is significant; it cannot be

disregarded.

Similarly, classifications to be measured against the equal

protection standard are not measured in a vacuum:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment enjoins ‘the equal pro

tection of the laws,’ and laws are not abstract proposi

tions. They do not relate to abstract units A, B and C,

but are expressions of policy arising out o f specific diffi

culties, addressed to the attainment of specific ends by

the use of specific remedies. The Constitution does not

require things which are different in fact or opinion

to be treated in law as though they were the same.”

( Tignerv. Texas, 310 U. S. 141, 147, 1940)

Or again:

“ It is by such practical considerations based on ex

perience rather than by theoretical inconsistencies that

17

the question of equal protection is to be answered.”

(.Railway Express Agency, Inc. v. New York, 336

U. S. 106,110, 1949)

Thus the action of the State must be viewed in the light

of the historical background and of the present practical

problem before the question of reasonableness can be de

termined. When the history and the practicalities in regard

to educational segregation in Virginia are examined, the

reasonableness of the Virginia action is clear. The record

abounds in evidence on these points and we shall now briefly

review it.

3.

T h e V ir g in ia B ackground

Any problem involving the races in Virginia can be un

derstood only in the light of the history of the last century.

Violence breeds resentment in both races. The passage of

time has removed violence and substantially removed re

sentment in Virginia. But it would be idle to say that Vir

ginians of both races— despite scientific tests (R. 181)— do

not recognize that differences between them exist. Virginia

has established segregation in certain fields as a part of her

public policy to prevent violence and reduce resentment. The

result, in the view of an overwhelming Virginia majority,

has been to improve the relationship between the different

races and between individuals of the different races.

One field in which segregation is basic Virginia policy is

that of education. Public education at the secondary level

does not have a long history. By the end of the War between

the States, free schools existed but they were called the

“pauper” schools, the number in attendance was few and the

facilities were miserable (R. 453). General public educa

18

tion was initiated about 18707 Its development lagged. In

1920 there were only 31,000 students in the Virginia public

high schools (R. 454).

The last 30 years have been a period of phenomenal

growth. There are now 155,000 students in Virginia’s pub

lic high schools (R. 454). This growth has placed a severe

strain upon the State’s economy. Conditions today are far

from ideal, but the testimony is that Virginia has met the

challenge.

It is true that in the early years the Negro and the white did

not receive equal treatment. But no complaint was made to

this Court then. When complaint is made now, substantial in

equality no longer exists; in many cases the Negro has better

educational facilities than the white. The record is full of

statistics which make that clear. A review of a few of them

may be helpful.

Fifteen years ago, the white school term was longer than

the Negro; today they are the same (R. 466). Then the

average Negro high school teacher received a salary only

70% as large as that of the white (D. Ex. 110, p. 2). Salary

scales are now equal (R. 409, 428) and are based in part on

training and experience. The average pay for a white high

school teacher slightly exceeds that for the Negro. But on

the elementary level that differential is reversed and the

Negro receives more on the average than the white (D. Ex.

110, p. 2; cf. D. Ex. 108, Table V I ). In 1940, 53% of the

white teachers had 4 years of college training while only

36% of the Negro teachers had that training; in 1950, 77%

of the Negro teachers had 4 years of college training while

only 62% of the white teachers met that standard (R. 442).

The Negro teachers on the whole have better training than

the white (R. 450). 7

7 See Constitution of Virginia of 1869, Art. VIII.

19

Virginia’s population is 77.8% white and 22.2% Negro;

its school population is 74.3% white and 25.7% Negro (R.

440). The total amount spent in Virginia for instruction in

1950 was divided 76.4% for white and 23.6% for Negro

(D. Ex. 108, Table II (a ) ) . The amount spent for instruc

tion has in the last 7 years increased 161% for the Negro

as compared with 123% for the white (R. 426). Total an

nual expenditures for public education in Virginia had

grown from 59 millions of dollars in 1946 to 120 millions 5

years later (D. Ex. 108, Table IX ).

After all these expenditures, the result is that today

general instruction for the Negro is as good as or better than

that for the white. As far as facilities go, no two buildings

are identical. A survey was made, however, and it was de

termined that in 63 of Virginia’s 127 cities and counties

facilities for Negro high school education are equal to those

for the white and in 30 of these counties and cities they are

or soon will be better than those for the white (R. 341-3,

349, 621; D. Ex. 10). This the court bekw found (R.

621).8

This tremendous program has hardly more than got under

way. A major source of construction money for Virginia’s

schools is, as we stated above, the State Literary Fund.

Loans from this fund made or approved are 48 millions of

dollars for white projects and 16.5 millions for Negro (D.

Ex. 108, Table X X ). In addition, in 1950, the General As

sembly of Virginia appropriated 45 millions of dollars

(known as the Battle Fund) as State grants for a school

construction program (R. 430; Acts, 1950, ch. 14).9 This

8There were in Virginia at the time of the hearing below 100 counties

and 27 cities. The cities are not included within the counties in Vir

ginia, but are separate and coordinate parts of the State government.

9An additional 15 million was appropriated in 1952 (Acts, 1952,

p. 1262).

20

law required localities to prepare overall 4-year plans for

school construction to be submitted to the State Department

of Education. These reports indicate plans to spend 189

millions of dollars on white projects and 74.5 millions on

Negro projects (D. Ex. 108, Table X V I ). Specific projects

included in these programs were divided 168 for the white

and 73 for the Negro (R. 431). These statistics assume

significance when related to each other:

W kite Negro

Population _____________ __ :......... ..... 77.8% 22.2%

School Population_______ _____—..... 74.3 25.7

Literary Fund Loans .... .......... ..... ...... 74.4 25.6

Battle Fund Plans (Dollars) ------ ...... 71.7 28.3

Battle Fund Plans (Projects) ..... .... . 69.7 30.3

The conclusions which must be drawn from those facts

are these:

1. Virginia has for the past decade been engaged in a

program designed to improve its school system both as to

physical plant and as to quality of instruction. In connection

with this program a very substantial and successful effort

has been made to eliminate inequalities between the races.

As a result, the general level of instruction in the Negro

schools exceeds that in the white.

2. Virginia has undertaken and is actively engaged in

carrying out a well-developed plan for the further improve

ment presently and in the immediate future of its school

system. This program involves the expenditure of funds

which, while not comparable to expenditures by the Federal

government, are enormous by Virginia standards.10 In

“ Appropriations from the general fund for the operation of Vir

ginia’s State government approximate 100 million dollars a year (Acts,

1952, p. 1258).

21

carrying out this program Virginia is giving to the Negro

more than his proportionate share.

3. The people of Virginia overwhelmingly believe that

segregated education is best for all the people. This must

be so. It is crystal clear that segregation is more expensive

than amalgamation. Yet Virginia citizens are willing to

pay the cost. They are firmly determined to root out factual

discrimination; they are equally determined to follow the

segregated course.

This was the finding of the Court below, amply supported

by the evidence:

“ It indisputably appears from the evidence that the

separation provision rests neither upon prejudice, nor

caprice, nor upon any other measureless foundation.

Rather the proof is that it declares one of the ways of

life in Virginia. Separation of white and colored ‘chil

dren’ in the public schools of Virginia has for genera

tions been a part of the mores of her people. To have

separate schools has been their use and wont.” (R. 620)

When the great majority of the people feel so certain that

segregated schooling is desirable in the circumstances under

which they live, in what way is it irrational or arbitrary ?

4.

T h e P sychological I ssue

The Appellants ignore the Virginia background; they

say that it is immaterial (Brief, p.. 25). They thus disregard

this Court’s admonitions that matters to be decided under

the Fourteenth Amendment must be decided in the light of

history and in the practical setting in which the conflict

arises.

The testimony they presented in the Court below like the

22

tract they now offer to this Court as an Appendix to their

brief11 discussed segregated education in the air. No definite

facts and no particular location affect the vista of the perfect

life to come.

They avoid the Virginia situation. That can be quickly

demonstrated.

The Appellants presented as their principal expert wit

nesses Drs. Brooks, Smith, Chein and Kenneth Clark. Dr.

Brooks is the administrator of an experimental school in

New York City (R. 170). He has had some experience in

Georgia but none in Virginia (R. 154, 169-70). Dr. Brooks

admitted that different localities and social conditions might

result in different answers (R. 159), but he never thereafter

throughout his testimony distinguished between localities.

He concluded that segregated education was harmful and

contrary to principles established by Virginia’s Department

of Education (R. 157-61), although those principles were

established with segregated education in view (R. 439-40).

Dr. Smith, a professor o f psychology at Vassar College

(R. 179), has never lived in the South and his conclusions

were based on “ some personal experience” and “general

reading” (R. 194). Without any knowledge of or regard to

Virginia conditions, he condemned segregation because it

cut down “ on the variety of experiences” (R. 185). He

thought the “ official insult” o f segregation by law worse

than the “ informal insult” of segregation in fact (R. 199).12

11 This is fundamentally a patent attempt at the rehabilitation of their

witnesses repudiated by the Court below. It is expert testimony given

unsworn and without opportunity for cross-examination. The Appen

dix is improper and should not be considered by this Court. Cf. Carr

v. Corning, 182 F. 2d 14, 21 (App. D. C. 1950), for a proper holding

where the situation was less blatant than here.

12 This conclusion was described by a witness for the Appellees as

the statement of an “ idealistic person” “ strongly prejudiced on the

side of abstract goodness” not tempered with “ common sense.” (R.

552-3)

23

Dr. Chein was another psychologist. He has never had

any experience in the South (R. 214, 218-9, 261-2). He sent

out a questionnaire, called a “ comprehensive study” , to 849

Social Scientists (R. 204) of whom there are at least 6,000

in the United States (R. 224), and received 517 replies (R.

204). O f these only 32 came from the 13 Southern States and

apparently none from Virginia (R. 232). The main ques

tion presented could be answered in only one way (R. 226);

it was a “ shotgun” or “ blunderbuss” question (R. 554). He

submitted his questionnaire to a group obviously too small to

give reliable results (R. 554-5). He testified that he was

“ n ot. . . an authority on Virginia” (R. 217). His conclusion

was that segregated education breeds “ feelings of inferiority

and of insecurity” and “ a sense of guilt” (R. 208-9).

Dr. Clark, a third psychologist, is a native of the Panama

Canal Zone. His background included 6 months at Hampton

Institute in Virginia and a number of years as a student and

teacher at Howard University in Washington, D. C. (R.

245-6). His experiences at Howard so warped his judgment

that, because o f segregation alone, his entire career was

changed (R. 267-8).

Dr. Clark’s testimony deserves somewhat less abbreviated

treatment than his co-witnesses for he based his conclusions

on “ tests” . The first was the doll test; Negro children (not in

Virginia) were asked to choose between dolls of different

colors (R. 248-53). From the reactions he obtained, he con

cluded that segregated education was psychologically evil

(R. 253). The record in this case shows that another expert

thinks that the test is “a very variable one” in which the

administering psychologist can obtain “ a slightly controlled

answer” (R. 519). But we need not linger on the dolls; the

identical testimony has been proved unreliable on expert

authority in a companion case.13

13Brief for Appellees, Briggs v. Elliott, No. 101, pp. 20-23.

24

Dr. Clark conducted one “ test” on the Virginia scene. He

questioned 14 of the plaintiffs who were brought from

Prince Edward County to Richmond especially for the in

terview (R. 273). He gave to the Court an example of the

interview with ludicrous results (R. 280-2). The answers

given by the children were critical of their school (R. 255-

60). These reactions were similar to those among children

in New England (R. 278). He concluded that the plaintiffs

have “ an excessive preoccupation with matters of race” (R.

260).

This is certainly far from remarkable. The plaintiffs had

engaged in a two-week strike 10 months before and the

pendency of this suit was a matter of intense interest in

the County. If answers such as Dr. Clark received had not

been given, “you should be very much surprised” (R. 555).

Neither of Dr. Clark’s “ tests” forms a reliable basis for the

firm scientific opinion on which constitutional issues must

be decided.

These witnesses, basing their opinions on a lack of knowl

edge of Virginia and in a field which, they have now so well

stated, “ is admittedly on the frontiers of scientific knowl

edge” (App. to Brief for Appellants, p. 18), are the Appel

lants’ case.14 But they were by no means the only experts

who testified before the Court below. The Appellees pre

sented 4 educators, a psychiatrist and 2 psychologists. Here

are their conclusions:

Dr. Howard, Virginia’s Superintendent of Public In

struction, with 30 years of experience as a teacher and

administrator in Virginia schools (R. 438): “ It has been

my experience, in working with the people of Virginia, in

cluding both white and Negro, that the customs and the

14The testimony of Dr. English (who found jokes depressing), Dr.

Mamie Clark and Dr. Lee given in rebuttal is fragmentary, insubstan

tial and need not be discussed.

25

habits and the traditions o f Virginia citizens are such that

they believe for the best interests of both the white and the

Negro that the separate school is best. . . (R. 444)

Dr. Lancaster, former State Superintendent of Public

Instruction, now President of Longwood College, Farmville,

Virginia (R. 463) : “ I have no evidence that segregation in

the schools per se has created warped personalities, and so

forth. . . .” “ But there is certainly nothing to indicate that

[Negro students] are thwarted in their development or

affected adversely.” (R. 472) If segregation be stricken

down, “ the general welfare will be definitely harmed.” (R.

472) . . there would be more friction developed.” (R. 468)

“ . . . the progress of Negro education . . . would be set back

at least half a century. . . .” (R. 469)

Dr. Darden, former Member of Congress and Governor

of Virginia, now President of the University of Virginia

(R. 452) think the races separated, if given a fairly

good opportunity, are better off.” (R. 458) “ . . . given good

schools and good teachers, the children in separate schools

in Virginia would be better off than in mixed schools.” (R.

459)

Dr. Stiles, Dean of the Department of Education of the

University of Virginia, not a native Virginian and with wide

experience in States where schools are not separate (R. 486-

9) : In mixed schools, the Negroes “ keep to themselves” ,

“may become very aggressive . . . or . . . very submissive.”

(R. 489-90) The Negroes are not accepted by the white

students (R. 490) or by teachers. “ The teacher’s acceptance

of a child . . . is a vital factor in her ability to teach him, or

the child’s being accepted in a group . . . is a vital factor in

how well he learns.” (R. 500-1) If the Negro children were

placed in the same schools as the white, “ . . . I think they

would be worse off at the present time.” (R. 504) “ The

Negro child gets an opportunity to participate in segregated

26

schools that I have never seen accorded to him in non-segre-

gated schools. He is important, he holds offices, he is accepted

by his fellows, he is on the athletic teams, he has a full place

there.” (R. 512)

Dr. Kelly, child psychiatrist, a native of Michigan with

national experience and 6 years in Virginia (R. 515-6) : “ I

think that the abrupt termination of segregation [by law]

would make for some very vicious and very subtle forms of

segregation. . . .” (R. 523) “ When the two groups are

merged, the anxieties of one segment of the group are quite

automatically increased and the pattern of the behavior of

the group is that the level of group behavior drops. . . . ”

(R. 524) “ . . . given equal opportunities o f physical equip

ment and teacher background, I could visualize no great

harm coming to either group.” (R. 525 )

Mr. Buck, clinical psychologist educated in Philadelphia’s

mixed public schools and with a broad Virginia experience

(R. 530-4) : “ I don’t think that any thoroughly objective

and sufficiently large study [of the effect of segregated

schools] has ever been done.” (R. 539) “ I do not” think it

would be possible for the Negro child to obtain general

acceptance by white teachers and students (R. 537-8). “ I do

not know of any instance in history where a social ill was

corrected by coercion or by a dramatic or sudden change,

where the results were beneficial to either group or both

groups.” (R. 536)

Dr. Garrett, Chairman of the Department o f Psychology

of Columbia University, a leading national authority under

whom Dr. Chein and Dr. Clark studied, a native Virginian

and a graduate of a Virginia College (R. 545-8) : “ So long

as the facilities which are allowed are equal, the mere fact

of separation does not seem to me to be, in itself discrimi

natory.” (R. 550) “ It seems to me that in the State of

Virginia today, taking into account the temper of its people,

27

its mores, and its customs and background, that the Negro

student at the high school level will get a better education

in a separate school than he will in mixed schools.” (R. 555)

It will not do to say, as the Appellants do (Brief, p. 23),

that the witnesses for the Appellees admitted that segrega

tion is harmful. They did not do so in the overall Virginia

surroundings. Dr. Garrett made his position completely clear

on this point:

“ What I said was that in the state of Virginia, in the

year 1952, given equal facilities, that I thought, at the

high school level, the Negro child and the white child—

who seem to be forgotten most of the time— could get

better education at the high school level in separate

schools, given those two qualifications: equal facilities

and the state of mind in Virginia at the present time.

* * *

“ If a Negro child goes to a school as well-equipped

as that of his white neighbor, if he had teachers of his

own race and friends of his own race, it seems to me he

is much less likely to develop tensions, animosities, and

hostilities, than if you put him into a mixed school

where, in Virginia, inevitably he will be a minority

group. Now, not even an Act of Congress could change

the fact that a Negro doesn’t look like a white person;

they are marked off, immediately, and I think, as I have

said before, that at the adolescent level, children, being

what they are, are stratifying themselves with respect

to social and economic status, reflect the opinions of

their parents, and the Negro would be much more likely

to develop tensions, animosities, and hostilities in a

mixed high school than in a separate school.” (R. 568-

9)

Like the witnesses for the Appellants, these experts pre

sented by the Appellees are eminent men. They do not stand

alone; they are quite representative of a great number of

experts not available for presentation to the Court below.

28

This Court is now presented with the conclusions of other

outstanding scholars who give unquestioning support to

their views.15

The Court below was plainly justified in its finding that

the Appellants’ evidence did not overbalance that for the

Appellees on this phase of the case (R. 619). That is almost

all that need be said. But one further facet of the expert

testimony should be mentioned. Here, as in Briggs v. Elliott,

it is urged that the factors which this Court found determi

native in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950), are

equally determinative here (Brief, p. 22).

Judge Parker disposed o f this contention in a most ad

mirable manner in his opinion in Briggs v. Elliott (98 F.

Supp. 529, 535, E. D. S. C. 1951; Record on appeal, pp.

185-6). In this case, his views are supported by expert

testimony:

Dr. Stiles: “ I think as people are more alike in their adult

status and in their cultural attainments there is a greater

chance of . . . mutual acceptance.” . . the problem in the

high school level is accentuated by the attitudes of parents.”

“ I think [the high school] would be the most difficult level

at which to bring about the abolition of segregation.” (R.

493)

Dr. Lancaster: “ I think it has been pretty clearly brought

out that we have a state of maturity that is obtained, cer

tainly on the graduate and professional levels, where there

is far more tolerance than there is among children. . . .”

(R. 468)

Dr. Garrett: “ . . . I think that graduate students . . . are

mature enough to meet their own responsibilities and to

decide for themselves who their friends will be . . . so that

it is no longer on a strictly racial basis.” (R. 565)

These expert opinions support from a psychological point

of view the obvious fact that different sets of values obtain

15Brief for Appellees, Briggs v. Elliott, No. 101, pp. 27-35.

29

at the high school level from those in graduate schools or

even in colleges. People do not mature with a high school

diploma; maturity comes gradually. But nowhere is the level

of maturity more important than in the field of race relations.

The testimony of the expert witnesses presented by the

Appellees that, in the Virginia situation, segregated educa

tion at the high school level is best for the individual students

of both races is not a suggestion that Virginia may properly

deny constitutional rights by an ex parte determination of

what is best for the individual students. See McKissick v.

Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949, 953-4 (4th Cir. 1951), cert, de

nied 341 U. S. 951 (1951). The police power is designed for

exercise in the general welfare. The State may not, where fa

cilities are unequal, declare that segregation is still required,

for such a requirement offends the Constitution. But where

facilities are equal the State is not exercising any arbitrary

paternalism in requiring segregation for there is no dis

crimination and where there is no discrimination State action

must be upheld.

W e conclude therefore that psychology, a “ new science”

(R. 547), cannot provide any satisfactory basis for a deter

mination that segregated schooling in the Virginia back

ground is unreasonable The consensus of social scientists,

despite the statement of Appellants (Brief, p. 22) and their

remarkable polemic (App. to Brief), is not as they say it is.

At most, there is a conflict. The social traditions of half the

nation should not be overthrown on such surmise and specu

lation.

5.

T h e E ffect of A m a lg a m a tio n

W e do not seek here to threaten or to coerce. We seek

simply to show that the end of segregation by law will not

be the millennium. W e say this with expert backing.

30

Let it be noted at the beginning that there is no precedent

that, if high schools in Virginia are amalgamated, inter

racial difficulties will not arise. The graduate school cases

are not in point. As Dr. Garrett said:

“ Whenever there are just a few members of a differ

ent racial group, they are . . . not regarded as a distinct

minority group— there are too few of them.” (R. 565)

So far in Southern graduate institutions, the Negro is a

rarity; it is only when the number becomes a substantial

proportion, as it would be in high school, that the problem

will become acute.

The main difficulty with amalgamation is that it will result

in all children receiving a worse education. The views of

the witnesses for the Appellees, the only ones at all familiar

with the Virginia problem, were unanimous on this point.

Virginians, as Dr. Howard said, would no longer permit

sizeable appropriations for schools on either the State or

local level; private segregated schools would be greatly

increased in number and “ the masses of our people, both

white and Negro, would suffer terribly.” (R. 444) Mr.

Buck said that, in that event, he thought many white parents

would withdraw their children from the public schools and,

as a result, the program of providing better schools would

be abandoned (R. 536-7). Dr. Darden was equally specific:

“ You are dealing with people who are now aware of

the necessity of carrying the double burden to a greater

extent than they have ever been aware in Virginia. In

my belief, they are not o f the opinion that they are going

to support mixed schools, and I don’t think they are

going to appropriate the money for them.” (R. 459)

31

So with the demise of segregation, education in Virginia

would receive a serious setback. Those who would suffer

most would be the Negroes who, by and large, would be

economically less able to afford the private school.

Strangely enough, the Negro would suffer in another way.

There are approximately 75,000 Negro teachers in the

United States but only about 5,000 of them are employed

in unsegregated States, a percentage, of course, much less

than the percentage of Negroes living in those States (R.

494). Virginia employs 22,241 teachers of whom 5,243 are

Negro, roughly the same percentage as in the school popula

tion (R. 450, 440). If segregation be outlawed, a great

many Negro teachers will lose their jobs (R. 450, 456-7,

470-1, 493-6, 537). Dr. Stiles stated the reasons very

clearly: school superintendents in the non-segregated states

employ Negro teachers to teach Negro children but they will

not employ Negro teachers to teach white children (R. 494-

5). He stated that, if segregation were to be abolished in

Virginia, he could not recommend Negro teachers for mixed

schools:

“ . . . it would be foolish to ignore the practical reality

of how people feel and make a recommendation that

you know would not work.” (R. 496)

If constitutional determinations were made on a theoreti

cal basis, these considerations might be irrelevant. But they

must be made, as this Court has said, on the practical basis

of existing conditions. These factors serve to highlight the

reasonableness of the Virginia decision under present cir

cumstances to favor segregated high school education.

32

6.

Co n clu sion

The Court below recognized the practical considerations

that it faced in this case and decided the case in their light.

It said:

“ So ingrained and wrought in the texture of their

life is the principle of separate schools, that the presi

dent of the University of Virginia expressed to the

Court his judgment that its involuntary elimination

would severely lessen the interest of the people of the

State in the public schools, lessen the financial support,

and so injure both races. . . . With the whites compris

ing more than three-quarters of the entire population

of the Commonwealth, the point he makes is a weighty

practical factor to be considered in determining whether

a reasonable basis has been shown to exist for the con

tinuation of the school segregation.

“ In this milieu we cannot say that Virginia’s separa

tion of white and colored children in the public schools

is without substance in fact or reason. W e have found

no hurt or harm to either race. This ends our inquiry.

It is not for us to adjudge the policy as right or wrong

— that, the Commonwealth of Virginia 'shall determine

for itself.” ’ (R. 621-2)

It is difficult to add to these findings. The decisions of this

Court support segregation in schools. The sole legal ques

tion is whether such segregation constitutes a reasonable

classification. In the Virginia background, expert opinion

is that segregation at the high school level is better for the

children of both races. If the schools were amalgamated,

the result would be that the children would not be helped but

hindered in their attempt to gain an education for living.

Segregation at the high school level is thus clearly reason

able.

33

W e submit, therefore, that segregation of children be

tween the races in Virginia high schools does not of itself

offend the Constitution.

B.

The Constitution Does Not Require Precipitate Action

1 .

T h e I ssue

W e assume for this portion of our argument that this

Court holds, as it rightly should, that segregation of the

races in high school does not without more violate constitu

tional limitations. W e pass then to the question whether,

since facilities which are to be equalized in the immediate

future are, however, presently unequal, the Court below as

a court of equity could not in its discretion refuse to order

immediate school amalgamation.

This issue is a narrow one. The Appellees admitted be

low that the buildings and related facilities for the Negro

were not as good as those for the white, though they pointed

to their building plans to equalize (R. 32-3). In addition,

the Court below found inequality as to curricula and trans

portation (R. 622-3) and ordered immediate equalization in

these two fields.

The Appellees assert here as a fact, although not of course

with the support of the printed record, that equality now

exists for all practical purposes as to curricula and transpor

tation. But even if that were not true, this is not the forum

in which that question should be argued. The Court below

retains plenary power to deal with it; if the Appellees still

offend, and they do not, the Appellants may obtain quick and

effective redress from the Court below and that is the place

for them to seek it.

34

The only question left before this Court is present in

equality as to buildings and facilities. This inequality, unlike

that as to curricula and transportation, cannot be corrected

overnight. It is important that the Court understand the

facts in this regard before a decision is reached.

2.

T h e F acts

The Appellees admitted that the building and facilities at

the Moton High School for the Negro children are not as

good as those at the Farmville High School for the white.

They are, however, better at least in some respects than

those enjoyed by the white children at the third high school,

Worsham. The expert witness for the Appellants admitted

this (R. 59).

This simply points up the problem for the local school au

thorities. It is manifestly undesirable to build 2 buildings

every time that one is built. Even if 2 were built, the teachers

could not be identical. Identity is therefore impossible; all

that is possible and what meets constitutional obligations is

“ substantial equality” , for absolute equality is “ impractical”

( Corbin v. County School Board, 177 F. 2d 924, 928, 4th

Cir. 1949). Obviously, under any dual system, schools for

one race may at any particular time be slightly better in un

important and incidental ways than schools for the other,

the position to be reversed shortly thereafter. The same is

equally true as between 2 schools for the same race.

The problem in Prince Edward County has been a serious

one. As we stated above, Negro high school enrollment has

grown out of all expectation in comparison with the white.

In 1951, Negro high school enrollment was 223% of what

it had been in 1941; in the same period white enrollment de

clined 25% (D. Ex. 102). Tax collections in the County

35

have doubled in that period (D. Ex. 5), yet the true wealth

per child in the County is substantially below the average

for the counties of the State even without regard to the

cities (D . Ex. 108, Table X IX ) . But in local effort, the

percentage of local wealth applied to the support of local

government, the County ranks ninth among the 100 counties

of the Commonwealth (R. 432; D. Ex. 108, Table X IX ). In

the past 5 years, while methods of financing a new school

were being actively investigated and plans for it brought to

a head (see pp. 4-5 above), the County added 3 temporary

buildings for the Negro school and doubled the number of

Negro high school teachers (R. 142; D. Ex. 102).16

The Appellants must admit that the future for Negro

high school students in Prince Edward County looks better

than the future for white students. The County now has in

hand almost $900,000 for the construction of a new Negro

high school ( R. 309-10). The School Board has acquired 63

acres of land in an advantageous location for the construc

tion of the school (R. 301-2; D. Exs. 1-3). Architects had

been employed and were in the course of preparation of de

tailed plans and specifications at the time of the hearing be

low (R. 311,330).

The new school will be a good one. It will have class

rooms, agricultural and other vocational facilities for both

boys and girls, auditorium, library, music rooms, gymna

sium, locker rooms and showers, cafeteria, clinic and ad

ministrative suite (R. 331-4; D. Exs. 8 and 9). The fa

cilities to be provided in this building will be better than

those provided anywhere in the County for white children

(D. Ex. 97) and the uncontradicted testimony is to that

effect (R. 337,383,386).

“ This tremendous growth in number of teachers over such a short

period of course accounts for the fact that average teaching experience

is less for the Negro than for the white (R. 388).

36

This building, providing these facilities, is not a dream

of the future; it is now under construction. It will be ready

for use by the time that school opens in September, 1953,

less than 12 months from this time (R. 311, 329, 338).

3.

T h e W isdom of t h e Court B elow

Despite these facts, the Appellants urge that the Court be

low, having determined that the Constitution and statutes

o f Virginia did not infringe upon rights guaranteed by the

Constitution of the United States, had no discretion except

to adopt the Draconian solution of immediate temporary

amalgamation. They urge further that amalgamation

should be required on a permanent basis because it may be a

burden to the Court below to have to hear contempt proceed

ings in connection with the enforcement of its own decree.

The Appellants seek a harsh and unyielding rule. This

Court sits here as a court o f appeal to review the action

taken below by a court o f equity:

“ A declaratory judgment, like other forms of equita

ble relief, should be granted only as a matter of judicial

discretion, exercised in the public interest. . . . It is

always the duty of a court of equity to strike a proper

balance between the needs of the plaintiff and the con

sequences of giving the desired relief.” Eccles v.

Peoples Bank, 333 U. S. 426, 431 (1948).

The consequences of giving the Appellants the relief de

sired by them in this case would be chaotic. If segregation

is not per se unlawful, in September, 1953, separate educa

tion in Prince Edward high schools will be constitutionally

permissible and will be required in accordance with valid

provisions of Virginia law. What the Appellants seek is

37

amalgamation in the middle of a school year to last only for

the rest of that year.17 Such action could not result in edu

cational benefit. Cf. Cumming v. Board of Education, 175

U. S. 528, 544 (1899). It would mean either that the high

schools of Prince Edward County would have to be closed

for the remainder of this school session or that the educa

tional process there would be thrust into such confusion that

schooling would become practically impossible. Revolutions

in social structure, if ever justified by court decree, must be

o f a permanent nature. What the Appellants ask the Court

to do will not help the children o f either race but will hurt

the children of both races. Such useless tumult is incon

ceivable.

These consequences are undesirable and needless. The

same plea was made in Briggs v. Elliott and Judge Parker

met the issue squarely:

“ In as much as we think that the law requiring segrega

tion is valid, however, and that the inequality suffered

by plaintiffs results, not from the law, but from the

way it has been administered, we think that our in

junction should be directed to removing the inequalities

resulting from administration within the framework

of the law rather than to nullifying the law itself. . . .

In directing that the school facilities afforded Negroes

within the district be equalized promptly with those

afforded white persons, we are giving plaintiffs all the

relief that they can reasonably ask and the relief that

17 This is apparently substantially the result reached in Gebhart v.

Belton, ...... Del........ , ...... A. 2d........ (Sup. Ct., August 28, 1952).

There, the Supreme Court of Delaware, affirmed as not an abuse of

discretion a chancellor’s order requiring school amalgamation but “ the

defendants may at some future date apply for a modification of the

order if . . . the inequalities . . . have then been removed.” W e have

been advised by the Attorney General of Delaware that a petition for

a Writ of Certiorari is being prepared on this particular point in that

case and will be promptly filed in this Court.

38

is ordinarily granted in cases of this sort. . . . The court

should not use its power to abolish segregation in a

state where it is required by law if the equality de

manded by the Constitution can be attained otherwise.

This much is demanded . . . if our constitutional system

is to endure.” (98 F. Supp. 529, 537; Record on appeal,

pp. 189-90; 103 F. Supp. 920, 922-3; Record on appeal,

pp. 304-5)

Nor is anything to be gained by urging that the Court

below cannot properly enforce its decree. The Federal

courts are entirely competent to handle complex problems of

human relations; in the comparable field of labor relations,

the reports are full o f cases where courts have been con

cerned with the detailed enforcement of decrees dealing

with complicated arrangements between employer and em

ployee.18 But the best answer to the contention of the Ap

pellants is that there is no evidence that strict adherence to

the decree is not now being given; the finding of the Court

below on that point is clear:

“ Both local and State authorities are moving with

speed to complete the new program. An injunction

could accomplish no more.” (R. 623)

There may be cases where it is apparent that a court is

so powerless to control a condition that it may destroy the

condition. That is not true here and argument that segrega

tion must be destroyed because it cannot be controlled is

irrelevant.

The consequences of giving the relief desired here by the

Appellants would harm everyone and help no one. It would

particularly hurt the children in school. It would result in a

“ Judge Parker made this point explicit in colloquy with counsel

in Briggs v. Elliott, Record on appeal, p. 281.

39

lost year. Even if the constitutional principle abstractly ap

plied suggested what the Appellants urge, practical con

siderations show the absurdity of its application here.

The Court below wisely and constitutionally adopted the

practical course. The Appellants have no cause for com

plaint.

IX .

CONCLUSION

This case concerns an area where traditions and customs

have long been fixed, where science has not yet replaced

experience. Evolution is desirable and is occurring; revolu

tion is not desirable and can only breed new and aggravated

resentments more difficult to control. The law is now settled

in accordance with principles designed for the solution of

an intensely practical problem and the constitutional issue

cannot be redetermined in disregard of those principles.

The Court below properly did not do so. Its decree should

be affirmed.

Dated October 9, 1952.

Respectfully submitted,

T. Justin M oore

A rchibald G. Robertson

John W . R iely

T. Justin M oore, Jr.

H unton, W illiams, A nderson, Counsel for the Prince Edward

Gay & M oore County School Authorities

Of Counsel

J. L indsay A lmond, Jr.

Attorney General

H enry T. W ickham

Assistant Attorney General

For the Commonwealth of Virginia