Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Joint Appendix Vol. II

Public Court Documents

March 26, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Joint Appendix Vol. II, 1990. b941bf45-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b704d59c-8999-40d9-898b-1c1de2101308/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-joint-appendix-vol-ii. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

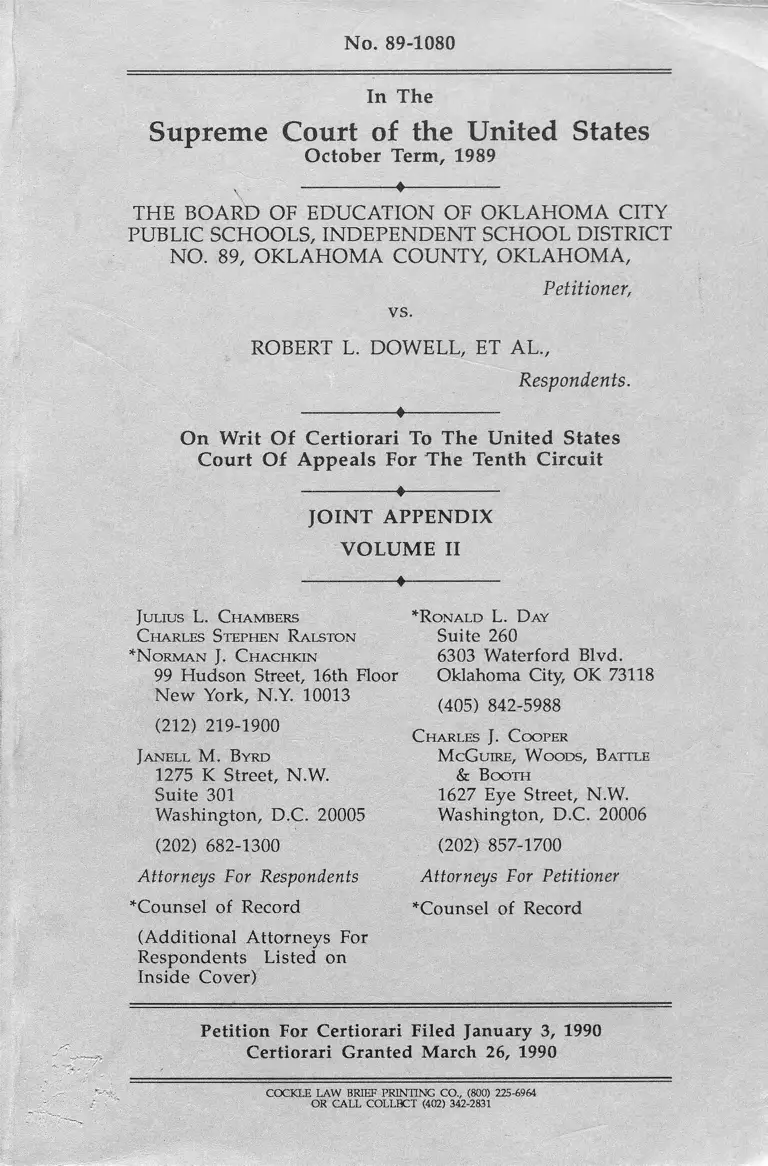

No. 89-1080

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1989

--------------4--------------

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF OKLAHOMA CITY

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT

NO. 89, OKLAHOMA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA,

vs.

Petitioner,

ROBERT L. DOWELL, ET AL.,

Respondents.

--------------4------ --------

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Tenth Circuit

--------------4--------------

JOINT APPENDIX

VOLUME II

----------------- 4-----------------

Julius L. C hambers

C harles S tephen Ralston

* N orman J. C hachkin

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Janell M . B yrd

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys For Respondents

"Counsel of Record

(Additional Attorneys For

Respondents Listed on

Inside Cover)

"'Ronald L. D ay

Suite 260

6303 Waterford Blvd.

Oklahoma City, OK 73118

(405) 842-5988

C harles J. C ooper

M cG uire, W oods, Battle

& B ooth

1627 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 857-1700

Attorneys For Petitioner

"Counsel of Record

Petition For Certiorari Filed January 3, 1990

Certiorari Granted M arch 26, 1990

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLHCT (402) 342-2831

J o hn W. W a lk er

J o h n W. W a lk er , P.A.

1723 So. Broadway

Little Rock, AR 72201

(501) 374-3758

L ew is B a r ber , J r .

B a r ber / T raviolia

1523 N.W. 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, OK 73111

(405) 424-5201

Attorneys For Respondents

1

VOLUME I

Relevant Docket Entries................................... 1

Motion to Close Case.............................................................29

Letter Opposing Motion (June 2, 1975)......................... 32

Opposition to Motion to Dismiss and Memo Brief

(June 30, 1975)................................................................... 34

Transcript of Proceedings at Hearing on Novem

ber 18, 1975.................................... .................. . ............. 38

Order Terminating Case (January 18, 1977)........... 174

Opinion of the United States District Court For

the Western District of Oklahoma, 606 F. Supp.

1548 [1985]...........................................................................177

VOLUME II

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals For

the Tenth Circuit, 795 F.2d 1516 [1986]..................... 197

Final Pretrial Order (May 29, 1987) (Excluding

Witness and Exhibit Lists)............................................. 215

Excerpts from Transcript of Proceedings at Hearing

Conducted June 15-24, 1987

Record, Volume II

William A.V. C lark ....................... 235

Finis Welch....................... 262

Record, Volume III

Finis Welch (continued).............................................. 274

Belinda Biscoe.................................................... 305

Susan Hermes................................................................321

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Record, Volume IV

Susan Hermes (continued)............................. . 330

Clyde M use............... 334

John Fink ...................... 344

Betty H il l ....................... 347

Maridyth McBee........................................................... 354

Vern M oore..................... 359

Betty Mason................... 370

Record, Volume V

Betty Mason (continued).............................................375

Alonzo Owens, Jr. .. .............. 379

Tommy B. W h ite .......................................................... 381

Carolyn Hughes............................................................ 389

Arthur W. Steller............................. 395

Karen Francis Leveridge......................... 401

Odette M. Scobey................. 402

Linda J. Johnson............................................................ 410

VOLUME III

Record, Volume VI

Gary E. Bender..............................................................418

Robert A. Brow n........................................................ 424

Billie L. Oldham.................................................. 428

John J. Lane.......................... 430

Herbert J. Walberg. ............ 436

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

Record, Volume VII

Robert L. Crain...............................................................452

Yale Rabin............... 463

Record, Volume VIII

John A. Finger, Jr.......... ................................................ 482

Mary Lee Taylor. ............................ ........... ................ 487

Gordon Foster............................... 501

Record, Volume IX

Gordon Foster (continued).........................................515

Clara Luper ............................. 516

Melvin Porter .................... 521

William Alfred Sampson............................ 524

Arthur Steller ......................................................... 531

Selected Exhibits Admitted Into Evidence at

Hearing Conducted June 15-24, 1987

Record, Supplemental Volume I

Plaintiff's Exhibit 48

Racial Composition of Elementary School Facul

ties, 1972-73, 1984-85, 1985-86, 1986-87 .............. 539

Plaintiff's Exhibit 50

1984- 85 Elementary Enrollment and Faculty -

Percent Black........................... 543

Plaintiff's Exhibit 52

1985- 86 Elementary Enrollment and Faculty -

Percent Black........................................................ 546

IV

Plaintiff's Exhibit 54

1986-87 Elementary Enrollment and Faculty -

Percent Black. ......................................... 549

Plaintiff's Exhibit 56

Minutes, December 10, 1984, School Board Meet

ing. . . . . . ....... 552

Record, Supplemental Volume II

Defendant's Exhibit 5D

Population Change in East Inner-City Tracts,

1950-1980 ...................... ..................... .............. .......... 561

Defendant's Exhibit 5E

Black Population Turnover in East Inner-City

Tracts ........................ 562

Defendant's Exhibit 6

Population Growth/Change in Oklahoma City 563

Defendant's Exhibit 10

Abstract, Clark, Residential Segregation in Ameri

can Cities................................................. 566

Defendant's Exhibit 11

Oklahoma City Public Schools, Percent Black in

Residential Z o n es................................... 568

Defendant's Exhibit 21

White Population in Oklahoma City SMSA,

1970-1980 ............................................................ 571

Defendant's Exhibit 24

Black Population in Oklahoma City SMSA,

1970-1980 ........................................................................ 572

Defendant's Exhibit 38

School Districts in Comparably Sized SMSA's .. 573

Defendant's Exhibit 40

Indices for Residential Zones............... 576

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

V

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

Defendant's Exhibit 45

Indices for All Schools................. 578

Defendant's Exhibit 63

Racial Composition of Elementary Schools (K-4),

1985-86.................................. 580

Defendant's Exhibit 67

Student Population by Race, 1970-1986............... 584

Defendant's Exhibit 76

Minutes, July 2, 1984 School Board Meeting... . 586

Defendant's Exhibit 79

Minutes, November 19, 1984 School Board Meet

ing. ............................................................................... 602

Defendant's Exhibit 108

Majority-To-Minority Transfers............................ 609

Defendant's Exhibit 119

Extracurricular Activities Report - High Schools 611

Defendant's Exhibit 120

Extracurricular Activities Report - Middle

Schools..................................................... 612

Defendant's Exhibit 140

Parental Organization Statistics............................... 613

Defendant's Exhibit 142

Adopt-A-School Statistics ............................................614

Opinion of the United States District Court For

the Western District Of Oklahoma, 677 F. Supp.

1503 [1987] (Reproduced in Petition for Writ of

Certiorari at App. IB; not reproduced in Joint

Appendix)

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals For

the Tenth Circuit, 890 F.2d 1483 (1989) (Repro

duced in Petition For Writ of Certiorari at App.

1A [majority], 46A [dissent]; not reproduced in

Joint Appendix)

197

[795 F.2d 1516 (10th Cir.1986)]

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

TENTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-1886

R o bert L. D o w ell , an infant under

the age of 14 years who sues by A.L.

Dowell, his father as next friend,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

V ivia l C. D o w ell , a minor, b y her father,

A.L. D o w ell , as next friend, et ah,

Intervening Plaintiffs-Appellants,

S teph en S. S a n g er , Jr., on behalf of himself

and all others similarly situated, et ah,

Intervening Plaintiffs,

and

Y vo n n e M o n et E llio t and D o n n o il S.

E llio t , both minor children, by and

through their parent and guardian,

D o n a ld R. E llio t , et al.,

Applicants in Intervention-Appellants,

vs.

T he B o a r d o f E du ca tio n o f th e O klahom a

C ity P u blic S ch o o ls, In d epen d en t D istrict

No. 89, O kla h o m a C ounty , O kla h o m a ,

A Public Body Corporate, et a l,

Defendants-Appellees.

[Filed June 26, 1986]

Appeal From the United States District Court

for the Western District of Oklahoma

(D.C. No. CIV-9452)

198

Theodore A. Shaw (Julius LeVonne Chamber and

Napoleon B, Williams, Jr., with him on the briefs), New

York, New York; John W. Walker, Little Rock, Arkansas;

and Lewis Barber, Jr., of Barber/Traviolia, Oklahoma City,

Oklahoma; for Plaintiffs and Applicants in Intervention-

Appellants.

Ronald L. Day of Fenton, Fenton, Smith, Reneau & Moon,

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, for The Board of Education of

the Oklahoma City Public Schools, Independent District

No. 89, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, Defendant-Appel

lee.

William Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney General,

Walter W. Barnett, Mark L. Gross, and Michael Carvin,

Attorneys, Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., filed

an Amicus Curiae brief for the United States of America.

Before MOORE and ANDERSON, Circuit Judges, and

JOHNSON, District Judge/

MOORE, Circuit Judge.

This appeal is the latest chapter in the odyssey of the

desegregation of the public school system in Oklahoma

City, Oklahoma. After many years of litigation, in 1977

the trial court found that the school district had achieved

^Honorable Alan Johnson, United States District Judge for the

District of Wyoming, sitting by designation.

199

unitariness and entered an order terminating the court's

active supervision of the case. The parties are now before

this court after an unsuccessful attempt to enjoin the

school district from altering the attendance plan previ

ously mandated by the district court. The district court, in

part relying on its 1977 termination order, not only

denied the petitioners' motion to reopen the case, but also

decided the issue of the constitutionality of the new

attendance plan. Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City

Public Schools, 606 F. Supp. 1548 (W.D. Okla. 1985). In this

appeal, we address only the precise question of whether

the trial court erred in denying the motion to reopen. We

hold, under the facts present here, that the court erred

and remand for additional factual determinations.

I .

This case was filed in 1961, and the history of the

litigation is extensive.1 In the ensuing years, the parties

struggled through the difficult task of desegregating the

public schools, each proffering plans to accomplish that

goal. Finally, after finding the district had "emascu-

Iate[d]" a previously approved plan, the district court

ordered the implementation of the so-called "Finger

Plan." Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 338 F. Supp. 1256, 1263 (W.D. Okla.), aff'd 465 F.2d 1

1 See Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools,

219 F. Supp. 427 (W.D. Okla. 1963); Dowell v. School Board of

Oklahoma City Public Schools, 430 F.2d 865 (10th Cir. 1970);

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools, 338 F.

Supp. 1256 (W.D. Okla.), aff'd, 465 F.2d 1012 (10th Cir.), cert,

denied, 409 U.S. 1041 (1972).

200

1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1041 (1972). That

plan, which was instituted during the 1972-1973 school

year, restructured attendance zones for high schools and

middle schools so that each level enrolled black and

white students. At the elementary level, all schools with a

majority of black pupils became fifth grade centers which

provided enhanced curricula. All elementary schools

with a majority of white students were converted to serve

grades one through four. Generally, the white students

continued to attend neighborhood schools while black

students in grades one through four were bused to

classes. When white students reached the fifth grade,

they were bused to the fifth grade centers, while black

fifth graders attended the centers in their neighborhoods.

Schools which were located in integrated areas qualified

as "stand alone schools," and the students in grades one

through five remained in their own neighborhoods.

In June 1975, the school board moved to close the

case on the ground that it had "eliminated all vestiges of

State-imposed racial discrimination in its school system,

and [that it was] . . . operating a unitary school system."

Although the motion was contested, the court terminated

active supervision of the case because it found the Finger

Plan had achieved its objective. Dowell v. School Board of

Oklahoma City Public Schools, No. CIV-9452, slip op. (W.D.

Okla. Jan. 18, 1977). See Dowell, 606 F. Supp. at 1551

(quoting the unpublished order in part). The order was

not appealed. The 1977 order did not vacate or modify

the 1972 order mandating implementation of the Finger

Plan.

In February 1985, the plaintiffs sought to reopen the

case, claiming the school board unilaterally abandoned

201

the Finger Plan and instituted a new plan for school

attendance. The Student Reassignment Plan, which has

already been implemented, eliminates compulsory busing

of black students in grades one through four and rein

stitutes neighborhood elementary schools for these

grades. Free transportation is provided to children in the

racial majority in any school who choose to transfer to a

school in which they will be in the minority. The racial

balance of fifth grade centers, middle schools, and high

schools is maintained through mandatory busing. As a

result of this plan, thirty-three of the district's sixth-four

elementary schools are attended by students who are

ninety percent, or more, of one race.

The district court denied the motion to reopen.2 The

court held that the Student Reassignment Plan was not

constitutionally infirm and, therefore, no "special circum

stances" were present that would justify reopening the

case. Dowell, 606 F.Supp. at 1557. The court concluded as

a matter of law: (1) The principles of res judicata and

collateral estoppel prohibit the plaintiffs from challenging

2 Plaintiffs contend that the district court erred in not

specifically granting their motion to intervene. Nevertheless,

the court held those who sought intervention were within the

ambit of the orginal [sic] plaintiff class, and those persons,

through their counsel, actively participated in the hearing to

reopen. They were clearly treated as party litigants even

though a formal order granting them intervention was not

entered. Indeed, at the outset of the hearing, the court stated

that the parties "did meet the requirement to be a plaintiff." As

a practical matter,the appealing parties were allowed to inter

vene despite the order denying all relief prayed for; therefore,

within the peculiar context of this case, we conclude the issue

is moot and the appealing persons are proper parties.

202

the court's 1977 finding that the school system was uni

tary. (2) The 1985 school district displays all indicia of

unitariness. (3) Neighborhood schools, when impartially

maintained and administered, are not unconstitutional.

Moreover, the existence of racially identifiable schools,

without a showing of discriminatory intent, is not uncon

stitutional. (4) The Student Reassignment Plan is not dis

criminatory and was not established with discriminatory

intent.

On appeal, the plaintiffs contend the trial court erred

in arriving at these conclusions without reopening the

case and without giving them as adequate opportunity to

present evidence on the substantive issues. We agree and

hold that, while the principles of res judicata may apply

, in school desegregation cases, a past-’finding of unitari-

j ness, by itself, does not bar renewed litigation upon a

j m andatory;:^ wherHt is alleged tha t

l-j significant changes have been made in a court-ordered

J school attendance plan,'any party for whose benefit the

| plan was adopted has a right to be heard on the issue of

whether the changes will effect the unitariness of the

system. In such circumstances, it is not necessary for the

/ party seeking enforcement of the injunction to prove the

changes were motivated by a discriminatory intent.

Accordingly, we conclude the trial court erred in not

reopening the case. II.

II.

A.

Any analysis of the legal principles governing this

case must start with the procedural framework in which

203

it was postured when the plaintiffs sought to reopen.

When the defendant board adopted the Student Reassign

ment Plan, the 1972 order approving the Finger Plan and

ordering its immediate implementation still governed the

parties. That order was in the nature of a mandatory

injunction, and the effect of that order was not altered by

the 1977 order terminating the court's active supervision

of the case.

Perhaps the members of the present school board

acted upon the belief that the 1972 order was no longer

effective; if so, their belief was unwarranted. Indeed, the

1972 order specifically provided:

The Defendant School Board and the indi

vidual members thereof, both present and future,

together with the Superintendent of Schools,

shall implement and place [the Finger Plan] into

effect . . . .

The Defendant School Board shall not alter

or deviate from the [Finger Plan] . . . without the

prior approval and permission of the court. If

the Defendant is uncertain concerning the

meaning of the plan, it should apply to the court

for interpretation and clarification.

Dowell, 338 F.Supp. at 1273 (emphasis added).

Nothing in the 1977 order tempered the 1972 manda

tory injunction. In fact, the 1977 order states:

The Court has concluded that . . . [the Finger

Plan] was indeed a Plan that worked and that

substantial compliance with the constitutional

requirements has been achieved. The School

Board, under the oversight of the Court, has

operated the Plan properly, and the Court does

not foresee that the termination of its jurisdic

tion will result in the dismantlement of the Plan

204

or any affirmative action by the defendant to

undermine the unitary system so slowly and

painfully accomplished over the 16 years during

which the cause has been pending before the

Court.

. . . The Court believes that the present

members and their successors on the Board will

now and in the future continue to follow the

constitutional desegregation requirements.

Dowell, No. CIV-9452, slip op. at 1 (W.D. Okla. Jan. 18,

1977) (emphasis added).

In light of these statements reinforcing the impor

tance of the remedial injunction and the lack of any

specific or implied alteration of that remedy, we must

conclude the court intended the 1972 order to retain its

vitality and prospective effect. Therefore, the competing

interests of both parties must be assessed first within the

penumbra of the outstanding 1972 order. To do otherwise

renders all of what has occurred since 1961 moot and

mocks the painful accomplishments of sixteen years of

litigation and active court supervision.

As amicus, the government argues that once a find

ing of unitariness is entered, all authority over the affairs

of a school district is returned to its governing board, and

all prior court orders, including any remedial busing

order, are terminated. According to the government, the

defendants could not be compelled to follow the Finger

Plan once the court determined the district was unitary.

We find the contention without merit. The parties cannot

be thrust back to the proverbial first square just because

the court previously ceased active supervision over the

operation of the Finger Plan.

205

While there are sound reasons for courts to seek the

earliest opportunity to return control of school district

affairs to the local body elected for that purpose, those

reasons do not require abandonment of the inherent equi

table power of any court to enforce orders which it has

never vacated. The court's authority is not diminished

once the original case has been closed because the via

bility of a permanent injunction does not depend upon

this ministerial procedure. See Ridley v. Phillips Petroleum

Co., 427 F.2d 19 (10th Cir. 1970). Therefore, termination of

active supervision of a case does not prevent the court

from enforcing its orders. If such were the case, it would

give more credence to the ministerial function of "clos

ing" a case and less credence to the prospective operation

of a mandatory injunction.3 See Berman v. Denver Tramway

Corp., 197 R2d 946 (10th Cir. 1952).

3 The Fourth Circuit has taken a different view with which

we cannot agree. In Riddick v. The School Board of the City of

Norfolk, No. 84-1815, slip op. (4th Cir. 1986), the court seems to

treat a district court order terminating supervision as an order

dissolving a mandated integration plan, despite the absence of

a specific order to that effect. The court makes a bridge

between a finding of unitariness and voluntary compliance

with an injunction. We find no foundation for that bridge. It

also appears inconsistent with Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, 584 F.2d 78 (5th Cir. 1978), in which the court held

that a finding by the district court that the school system was

"unitary in nature" did not divest the court of subject matter

jurisdiction of a petition to amend the desegregation plan

where the court had not dismissed the case. A finding of

unitariness may lead to many other reasonable conclusions,

but it cannot divest a court of its jurisdiction, nor can it convert

a mandatory injunction into voluntary compliance.

206

The government's position ignores the fact that the

purpose of court-ordered school integration is not only to

achieve, but also to maintain, a unitary school system.

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo., 609 F. Supp.

1491, 1515 (D. Colo. 1985).4 When the district court termi

nated active supervision over this case, it acknowledged

that the original purpose of the law suit had been

achieved and that the parties had implemented a means

for maintaining that goal. Dowell, 606 F. Supp. at 1551

(1977 termination order). However, without specifically

dissolving its decree, the court neither abrogated its

power to enforce the mandatory order nor forgave the

defendants their duty to persist in the elimination of the

vestiges of segregation.

We therefore see no reason why this case should be

treated differently from any other case in which the bene

ficiary of a mandatory injunction seeks enforcement of

the relief previously accorded by the court. See Swann,

402 U.S. at 15-16. When a federal court has restored

unsupervised governance to a board of education, the

board must, like any other litigant, return to the court if it

wants to alter the duties imposed upon it by a mandatory

4 See also Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 584 F.2d

78, 81 (5th Cir. 1978) (after full responsibility for educational

decisions has been returned to public school officials by the

court, they "are bound to take no actions which would rein

stitute a dual school system"); Graves v. Walton County Board of

Education, 686 F.2d 1135 (11th Cir. 1982), aff'g in part, rev'g in

part, 91 F.R.D. 457 (M.D. Ga. 1981) (despite an earlier finding

that desegregation had been accomplished, the courts reject a

modification of the 1968 desegregation plan which would

effectively resegregate the system).

207

decree. Vaughns v. Board of Education of Prince George's

County, 758 F.2d 983 (4th Cir. 1985). See also Pasadena City

Board of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976). It^is

only_when the order terminating active supervision'also

dissolves the mandatory inmncBonH^

board regains total independence from the previous

injunction.

B.

The record in this case indicates that the defendants,

unilaterally and contrary to the specific provisions of the

1972 order, have taken steps to avoid the duties imposed

upon them by a continuing decree. By implementing the

Student Reassignment Plan, the defendants have acted in

a manner not contemplated by the court in its earlier

decrees. The Plaintiffs now are simply attempting to reas

sert the validity of the 1972 order and to perpetuate the

duties placed upon the district.

When a party has prevailed in a cause for mandatory

injunction, that party has a right to expect that prospec

tive relief will be maintained unless the injunction is

vacated or modified by the court. See W.R. Grace and Co. v.

Local 759, International Union of United Rubber Workers of

America, 461 U.S. 757 (1983). See also GTE Sylvania, Inc. v.

Consumers Union of United States, 445 U.S. 375 (1980). To

make the remedy meaningful, the injunctive order must

survive beyond the procedural life of the litigation and

remain within the continuing jurisdiction of the issuing

court. E.E.O.C. v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 611 F.2d 795 (10th

Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 952 (1980); 11 Wright &

Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure § 2961 (1973). This

208

binding nature of a mandatory injunction is recognized in

school desegregation cases. Pasadena City Board of Educa

tion v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 439 (1976).

Thus, the beneficiary of a mandatory order has the

right to return to court to ask for enforcement of the

rights the party obtained in the prior litigation. To invoke

the court's authority, the part seeking enforcement must

establish that the injunctive decree is not being obeyed.

Northside Realty Associates, Inc. v. United States, 605 F.2d

1348 (5th Cir. 1979).

C.

Although prospective orders must be obeyed, federal

courts are also empowered to alter mandatory orders

when equity so requires. United States v. United Shoe

Machinery Corp., 391 U.S. 244 (1968); System Federation No.

91, Railway Employee's Department v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642

(1961); United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932). We

have previously adopted the rationale behind these cases

in establishing guidelines "applicable in all instances

where . . . the relief sought is escape from the impact of

an injunction." Securities and Exchange Commission v. Jan-

dal Oil & Gas, Inc., 433 F.2d 304, 305 (10th Cir. 1970).

Given the mandatory nature and prospective effect of

an injunctive order, changes in injunctions must not be

lightly countenanced but must be based upon a "substan

tial change in law or facts." Securities and Exchange Com

mission v. Thermodynamics, Inc., 464 F.2d 457, 460 (10th Cir.

1972), cert, denied, 410 U.S. 927 (1973). A change in atti

tude by the party subjected to the decree is not enough of

a change in circumstances to warrant withdrawing the

209

injunction. Id. Therefore, when a party establishes that

another has disregarded a mandatory decree or has taken

action which has resulted in a deprivation of the benefits

of injunctive relief, the court cannot lightly treat the

claim. Having^ once determined the necessity to impose a

remedy, the court should not allow any modification of

that remedy unless the law or the~uhderlying facts have

so changed that the dangers prevented by the injunction

"have become, attenuated to a shadow," Jan-dal, 433 F.2d

at 305. and the changed circumstances have produced

" 'hardship j>o extreme and unexpected' as to make_ the

decree oppressive." Safeway, 611 F.2d at 800 (quoting

Swift & Co.), see also United States v. United Shoe Machinery

Corp., 391 U.S. at 251-52. Indeed, this "difficult

and . . . severe requirement" is necessary to be consistent

with res judicata principles. Thermodynamics, 464 F.2d at

460.

D.

The court's 1972 order requiring implementation of

the Finger Plan was binding upon both sides. More point

edly, the order specified that the defendants were not to

"alter or deviate from the [Finger Plan] . . . without the

prior approval and permission of the court." Dowell, 338

F.Supp. at 1273. While defendants unilaterally could not

take action contrary to the plan, plaintiffs also could not

expect more than the approved plan provided. When, five

yeargjater, the court determined that the implementation

of-IhgJElnger Plan had resulted in unitariness within the

district, that finding became final, and it, too, is binding

upon the parties with equal force. Yet, that historical

finding does not preclude the plaintiffs from asserting

210

a that a continuing manda.tQ.ry._Qrder is not being obeyed

j and that the consequences of the disobedience have

destroyed the unitariness previously achieved by the dis- J trict. .....

Thus, while the trial court properly refused to permit

the plaintiffs to relitigate conditions extant in 1977, it

erred in curtailing the presentation of evidence of

changes that have since occurred. Consequently, plaintiffs

were deprived of the opportunity to support their peti

tion for enforcement of the court's prior order.

r—- In reaching this conclusion, we are not traveling new

trails. We contrast this case with the Spangler line of

cases5 in which (&§.aggrieved party sought remedial relief

in addition to the previous decree. Here, the plaintiffs do

not seek the continuous intervention of the federalxourt

decried by the SupremeJIpurt. We are not faced with an

attempt to achieve further desegregation bas_edjapon

minor demographic changes not "chargeable" to the

board. Spangler, 427 U.S. at 435. Rather, here the allega

tion is that the defendants have intentionally abandoned

a plan’ which achieved unitariness and substituted one

whichlippears to have the same segregative effect as the

l attendance plan which generated the original lawsuit.

Given the sensitive nature of school desegregation

litigation and the peculiar matrix in which such cases

exist, we are cognizant that minor shifts in demographics

or minor changes in other circumstances which are not

5 Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 375 F. Supp.

1304 (C.D. Cal. 1974), aff'd 519 F.2d 430 (9th Cir. 1975), vacated,

427 U.S. 424 (1976), on remand, 549 F.2d 733 (9th Cir. 1977).

211

the result of an intentional and racially motivated scheme

to avoid the consequences of a mandatory injunction

cannot be the basis of judicial action. See Spangler, 427

U.S. at 434-35; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971). However, when it is asserted j *

that a school board under the duty imposed by a manda

tory order has adopted a new attendance plan that is

significantly different from the plan approved by the

court and when the results of the adoption of that new

plan indictate a resurgence of segregation, the court is

duty bound either to enforce its order or inquire whethe

a change of conditions consistent with the test posed i

Jan-dal has occurred.

Therefore, consistent with traditional concepts of

injunctive remedies in federal courts, plaintiffs have the

right to a full determination of whether and to what

extent their previously decreed rights have been jeopar

dized by the defendants' actions subsequent to the entry

of the mandatory decree. Moreover, we hold the plain

tiffs' assertion that the defendants abandoned the Finger

Plan without court approval constitutes the "special cir

cumstances" the trial court found absent from the case.

The existence of these circumstances should have been

recognized by the trial court as a basis for relief under

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b), and the court's failure to do so

results in manifest abuse of discretion which requires

reversal. See Security Mutual Casualty Co. v. Century Casu

alty Co., 621 F.2d 1062 (10th Cir. 1980). III.

Having concluded the district court erred in not

granting plaintiffs' motion to reopen, we must decide

III.

212

whether the error is significant in light of the court's

factual findings on the board's new plan. After review of

the evidence, which led the district court to hold the new

plan was not constitutionally infirm, we conclude that

reversal will not be futile.

The record indicates that the hearing from which the

court's findings were drawn was called for a narrow

purpose. The order setting the hearing provided:

[T]he motion to intervene and reopen and the

defendants' response join the issues, and the

matters in them are set for evidentiary hear

ing . . . at which time the question of whether the

case shall be reopened and the applicants allowed to

intervene shall be tried and disposed of.

j (Emphasis added.) From the outset, then, the only issues

the parties were notified to..present to the court dealt with

reopening and intervention. The court did not indicate

that it intended to hear evidence upon or determine the

substantive constitutional issues relating to the plan or its

11 effects.

i

Plaintiffs now argue they were unprepared to be

heard on the ultimate issues. Indeed, on two occasions

plaintiffs' counsel inquired whether the only issue to be

heard was that of reopening, and the court replied affir

matively. Hence, plaintiffs argue their understanding of

the limited scope of the hearing curtailed their cross-

examination of the defendants' witnesses and prevented

them from introducing evidence of alternative plans. Our

review of the record supports this assertion. While evi

dence bearing on the substantive issue was presented, it

focused on the underlying reasons for reopening the case

rather than on the ultimate constitutional issue.

213

In reaching the substantive.Issues,, the.jdistr.ict court

also improperly recast the burden of proof. As we have

already noted, the plaintiffs, as the beneficiaries of the

original injunction, only have the burden of showing the

court's mandatory order has been violated. Northside

Realty Associates, Inc. v. United States, 605 F.2d 1348 (5th

Cir. 1979). The defendants, who essentially claim that the

injunction should be amended to accommodate neighbor

hood elementary schools, must present evidence that

changed conditions require modification or that the facts

or law no longer require that enforcement of the order.

See E.E.O.C. v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 611 F.2d 795 (10th Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 952 (1980).

Thus, by placing the burden on the plaintiffs to show

the school district was not longer unitary, the court

changed the usual course of what in reality is a petition

for a contempt citation. The Plaintiffs were required not

only to prove the mandatory injunction had been vio

lated, but also that the violation contravened the constitu

tion. In the framework of this case, the latter element was

beyond the scope of the hearing and certainly never the

plaintiffs' burden.

Accordingly, we believe the trial court reached the

merits prematurely. We applaud the court's effort to bring

speedy resolution to a difficult issue, but fairness and our

understanding of the procedures governing federal

injunctive remedies require us to conclude the court did

not give the moving parties ample opportunity to

develop substantive issues.

We have confined our analysis to the narrow issue of

the plaintiffs' right to reopen; therefore, our holding

214

should not be construed as addressing, even implicitly

the ultimate issue of the constitutionality of the defen

dants' new school attendance plan. The judgment of the

trial court is reversed and the case is remanded for fur

ther proceedings to determine whether the original man

datory order will be enforced or whether and to what

extent it should be modified.

215

[RECORD, VOLUME I, doc. 17]

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA

ROBERT L. DOWELL, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, et a l,

Defendants.

CIV-61-9452-B

FINAL PRETRIAL ORDER

Date of Conference: June 4, 1987

Appearances: Lewis Barber, Jr., Oklahoma City, Okla

homa, for plaintiffs

John W. Walker, Little Rock, Arkansas, for

plaintiffs

Theodore M. Shaw, New York, New York,

for plaintiffs

Norman J. Chachkin, New York, New

York for plaintiffs

Ronald L. Day, Oklahoma City, Okla

homa, for defendant

Laurie W. Jones, Oklahoma City, Okla

homa, for defendant

I. Preliminary Statement

This case is before the Court pursuant to the remand

directions of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Tenth Circuit, 795 F.2d 1516 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 93 L.

Ed. 2d 370 (1986).

In 1972 this Court granted plaintiffs injunctive relief

designed to dismantle the dual school system in Okla

homa City. 338 F. Supp. 1256 (W.D. Okla.), aff'd 465 F.2d

216

1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1041 (1972). On

January 18, 1977 the Court entered an Order finding that

the Board had carried out the injunction and has "slowly

and painfully accomplished" the goal of establishing a

"unitary system." The Order dissolved the Biracial Com

mittee previously created and directed that "Jurisdiction

in this case is terminated . . . " but it did not by its terms

vacate or dissolve the injunctive relief granted in 1972.

From the 1972-73 school year through the 1984-85

school year, the public schools of Oklahoma City were

operated consistent with the 1972 decree. Although

changes in pupil assignments were made from time to

time during those years (for example, as schools were

closed due to declining system-wide enrollment), the

school system continued to utilize the techniques of pair

ing, clustering, and compulsory transportation at the ele

mentary level that had been the essential feature of the

assignment plan approved and ordered into effect in

1972.

Effective for the 1985-86 school year, the Board of

Education adopted a new plan for pupil assignment in

grades 1-4 which eliminated pairing and clustering, sub

stituting a "neighborhood school" assignment plan which

eliminated compulsory transportation at those grade

levels and utilized zone lines similar to those employed

for elementary school assignments prior to 1972. Under

this method of pupil assignment, some K-4 elementary

schools in the district became predominantly Black for

the first time since 1972. (Fifth-grade centers were relo

cated throughout the school district rather than being

placed only in the northeastern section of the city and

217

these schools, like those serving grades 6-12, remain

desegregated.)

The plaintiffs sought to intervene new class represen

tatives and to reopen this action in 1985, to challenge the

decision of the school board to alter the basic method of

pupil assignment at grade levels 1-4. This Court denied

relief, but the Court of Appeals has remanded for a

determination whether the school board can establish

sufficient justification for the Court to dissolve or modify

the 1972 injunctive decree. See 795 F.2d at 1521-22. On

February 5, 1987, the Court granted the Petition for Inter

vention and plaintiffs' Motion to Reopen, and set the

matter down for hearing on the merits.

In these remand proceedings, the burden of proof

rests with the school board. "The defendants, who essen

tially claim that the injunction should be amended to

accommodate neighborhood schools, must present evi

dence that changed conditions require modification or

that the facts or law no longer require the enforcement of

[1972] order." Id. at 1523.

II. Stipulations

A. All parties are properly before the Court.

B. All parties have been correctly designated.

C. After exchanging and reviewing the exhibits,

although there are some objections the parties

have agreed to stipulate as to the admissibility of

many exhibits. These stipulations are detailed in

Part IV of the Pre-Trial Order infra.

F. Legal Issues:

218

The primary legal issues presented in the current

posture of the case are:

1. Have conditions or circumstances so changed

since entry of this Court's 1972 decree that it should

be dissolved or modified to permit use of defendants'

"neighborhood school" assignment plan for school

attendance in grades 1-4?

2. If such dissolution or modification is war

ranted, is the school board's 1985 plan constitutional?

3. Has the school district maintained a unitary

school system since 1977?

4. May plaintiffs seek modification to alter the

form of relief provided through the 1972 decree, and

what showing must plaintiffs make to justify such

relief?

G. Factual Issues*:

1. Are the elementary schools with enroll

ments greater than 90% Black under the school

board's 1985 student assignment plan for grades 1-4

vestiges of the prior dual school system?

2. Is the residential segregation which exists in

Oklahoma City today a vestige of previous unlawful

state-compelled segregation?

3. How has white student enrollment in the

Oklahoma City Public Schools changed since 1972,

* The parties have attempted to identify major factual

issues. However, it should be noted that the parties are not in

agreement about the significance of each. Plaintiffs believe

that, with respect to some of the these areas, the facts articu

lated in support of the decision to adopt the 1985 plan, even if

true, are insufficient as a matter of law to justify that plan. The

school board believes that each of the factual issues is material

to the legal determinations which the Court must make. Both

parties agree that no single factual issue is necessarily out

come-determinative.

219

and what further changes would result from resump

tion of the Finger Plan for elementary schools or from

implementation of the plans proposed by plaintiffs?

4. Did the school board adopt the 1985 student

assignment plan without the intent to discriminate

on the basis of race?

5. Did the school board adopt the 1985 student

assignment plan for legitimate non-discriminatory

reasons?

6. Did parental and community involvement,

including PTA membership and participation, decline

in the Oklahoma City Public Schools after 1972?

7. What effect has the school board's 1985 plan

had, and what effect will it have in the future on

parental and community involvement?

8. Did elementary school students' participa

tion in extra-curricular activities decline in the Okla

homa City Public Schools after 1972?

9. What effect has the school board's 1985 plan

had, and what effect will it have in the future on

elementary school students' participation in extra

curricular activities?

10. What had been the pattern, if any, of faculty

assignments to elementary schools since 1977?

11. Are present teacher assignment practices a

vestige of previous unlawful state-compelled seg

regation, or are they motivated by discriminatory

intent?

12. Did the Finger Plan result in placing a dis

proportionate share of the burdens of desegregation

upon young Black Children in grades 1-4, and did

demographic changes after 1972 increase those bur

dens?

13. Did the "stand-alone" feature of the Finger

Plan, in combination with demographic changes after

220

1972, result in placing further burdens on Black chil

dren?

14. Are plaintiffs' proposed plans logistically,

financially and educationally feasible?

15. Does the racial composition of public

schools affect the academic and social achievement of

black students?

16. Does parental and community involvement

in the public schools affect the academic and social

achievement of all students?

17. Is the 1985 student assignment plan being

implemented in a uniform, equitable and non-dis-

criminatory manner?

18. What are the attitudes of the school admin

istration and the community with respect to the 1985

student assignment plan?

19. Is the implementation of the 1985 student

assignment plan accomplishing the objectives of the

plan?

III. Contentions

The contentions of the plaintiffs and defendants are

attached hereto as Appendices "A" and "B" respectively. IV.

IV. Exhibits

1. Attached hereto as Exhibits "C" and “D" respec

tively are the Exhibit Lists of the plaintiffs and defen

dants. Exhibits not listed will not be admitted by the

Court unless good cause be shown and justice demands

their admission.

221

2. The parties stipulate that the following exhibits

may be received in evidence without objection (the par

ties reserve the right to argue to the Court concerning the

weight properly to the accorded to any exhibits):

Plaintiffs' Exhibits 1-29, 36-40, 47, 55, 56, 58

Defendants' Exhibits 1-6, 20-21, 24, 28, 34-37,

41-48, 57, 60-84, 88,

90-109, 111-121, 123-132,

134-137, 141-148, 151-160,

162-164, 172-174, 179-184,

187-196, 201-210

3. Plaintiffs agree to the introduction into evidence

of the following exhibits subject to defendants' willing

ness to stipulate as indicated:

a. Defendants' Exhibit 7, if it is stipulated

that the exhibit is based upon Defendants'

Exhibit 28; and if it is stipulated that the exhibit.

is a demonstrative representation of only selected

Black population relocations in the Oklahoma

City School District in the years indicated, that

is, Black students, living within the area indi

cated who were enrolled in kindergarten in the

district during the 1974-75 school year; and if it j

is stipulated that the exhibit does not indicate

the number of students who, according to the

records of the district, resided at the same \

address in 1977-78; and if it is stipulated that the

figure "209" labelled "to Non-ISD" on the

exhibit represents the number of 1974-75 Black

Kindergarten students whose names were not

found on the district's enrollment records in the

1977-78 school year or for whom the district's

enrollment records did not indicate an address, J

rather than the number of 1974-75 Black Kinder- '

garten students for whom the district had an

out-of-ISD 89 address in the 1977-78 school year.

222

b. Defendants' Exhibit 8, subject to the

presentation of an adequate foundation explain

ing the manner in which the data from which

the exhibit was prepared were gathered and

analyzed, if stipulations sim ilar to those

described above for Defendants' Exhibit 7 are

made concerning the selective character of the

population movements analyzed, the fact that

the exhibit does not include an indication of the

number of students who did not move, and the

meaning of the label "To Non-ISD."

c. Defendants' Exhibit 9, subject to the pre

sentation of an adequate foundation explaining

the manner in which the data summarized in

part (b) of the exhibit were gathered and

analyzed, and if it is stipulated that the data

summarized in part (a) are from Defendants'

Exhibit 28; and if it is stipulated that the

numbers indicated as being "no longer in dis

trict" represent students whose names did not

appear on the district's enrollment records for

the later year, or for whom the district had no

address on its enrollment records for the later

year, rather than students for whom the district

had an out-of-ISD 89 address for the later year.

d. Defendants' Exhibits 12 and 13, if it is

stipulated that the exhibits are demonstrative

representations of the proportions of students in

grades K-12 now living within each of the

"attendance areas" into which the school district

has been divided who are Black, rather than

representations of school enrollments.

e. Defendants' Exhibits 15-19, if the source

of the data represented in these exhibits is stipu

lated.

f. Defendants' Exhibits 58 and 59, if it is

stipulated that the term "population" on each of

these exhibits refers to the trial number of K-12

223

students enrolled in the public schools of Dis

trict 1-89 for the years indicated.

4. Plaintiffs do not intend to offer into evidence

their proposed Exhibits 42-45, 49, 51 or 53. At this time

plaintiffs do not expect to offer Exhibits 59, 61 or 63.

5. Defendants do not intend to offer into evidence

their proposed Exhibits 149 or 150.

6. The parties are unable to stipulate to the admis

sion into evidence of the following exhibits in the absence

of presentation of an adequate foundation, and they

reserve the right to object to the exhibits based upon

information developed during the presentation of foun

dation; unless otherwise indicated in this Pre-Trial Order,

however, the parties are not at this time aware of other

bases for objection to these exhibits:

Plaintiffs' Exhibits 41, 46, 48, 50, 52, 54

Defendants' Exhibits 11, 14, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29-33,

38-39, 40, 56, 56A, 85-87,

89, 110, 133, 138-140,

165-171, 175-178, 197-200

7. Plaintiffs object to the following exhibits on the

ground of relevancy: Defendants' Exhibits 38, 39, 49-55,

186.

8. Defendants object to the following exhibits on

the ground of relevancy: Plaintiffs' Exhibits 30-35, 48, 57.

9. Plaintiffs object to the following exhibits on the

ground of hearsay: Defendants' Exhibits 10, 27, 186.

10. The parties reserve the right to object to the

following exhibits which have not yet been completed or

224

withdrawn from the Clerk's Office and been made avail

able for inspection:

Plaintiffs' Exhibits 3, 60, 62

defendants' Exhibits 122, 161, 185

V. Witnesses

Attached hereto as Exhibits "E" and "F" respectively

are the witness lists of the plaintiffs and defendants. No

unlisted witness will be permitted to testify as a witness

in chief except by leave of Court when justified by excep

tional circumstances.

VI. Trial Briefs

The parties are submitting trial briefs simultaneously

with the filing of this Pre-Trial Order.

The Court has ordered that proposed Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law be submitted within two

weeks of the conclusion of the trial herein.

VII. Estimated Trial Time

Five to ten days. VIII.

VIII. Possibility of Settlement

Good __ F a ir___ Poor X

All parties approve this Order and understand and

agree that this Order supersedes all pleadings and shall

not be amended except by Order of the Court.

225

Norman J. Chachkin

LEWIS BARBER, JR.

Barber/Traviolia

1528 N.E. 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, OK

73111

(405) 424-5201

JOHN W. WALKER

John W. Walker, RA.

1723 Broadway

Little Rock, AR 72206

(501) 374-3758

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

/ s / Ronald^L. Dâ y

LAURIE W. JONES

Fenton, Fenton, Smith,

Reneau & Moon

Suite 800

One Leadership

Square

211 North Robinson

Oklahoma City, OK

73102

(405) 235-4671

Attorneys for Defendants

APPROVED this __ day o f ____________________ , 1987.

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS / s /

THEODORE M. SHAW

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

99 Hudson Street,

16th floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

LUTHER BOHANAN

UNITED STATES

DISTRICT JUDGE

226

APPENDIX "A"

Plaintiffs' Contentions

1. Circumstances and conditions have not changed

since entry of the Court's Order in 1972 so as to provide

legal justification for the modification or dissolution of

the decree sought by the school board.

The purpose of the 1972 Order was to eliminate pupil

segregation at all grade levels from the Oklahoma City

Public Schools. The Court explicitly found that a system

of geographic zoning (often referred to as "neighborhood

schools") for pupil assignments was insufficient to

achieve that purpose in Oklahoma City because of the

pattern of intense racial residential segregation and the

deliberate location of schools for students of each race in

areas of racial residential concentration.

Moreover, the Court has found in this case that the

pattern of residential segregation, and specifically the

overwhelming concentration of Black residents in north

eastern Oklahoma City, was the result of deliberate dis

criminatory policies enforced and maintained as the

public policy of the State of Oklahoma and of school

authorities' actions.

These underlying conditions have not been altered

since entry of the Court's 1972 decree:

(a) Although the public schools of the district were

desegregated between 1972-73 and 1984-85, all of the

demographic exhibits to be introduced at the hearing

indicate clearly that the northeastern portion of Okla

homa City is today as nearly exclusively Black as it was

in 1972.

22 7

(b) At the 1985 hearing, the President of the school

board testified that the attendance zones adopted for K-4

pupil assignment in 1985-86 and 1986-87 were "the same

neighborhood boundaries as have existed for years" (Tr.

336). A comparison of the attendance zones used by the

district for elementary schools in the early 1960's, in 1970,

and currently, confirms this statement.

(c) As the enrollment figures demonstrate graph

ically, reimposition of those zoning patterns on the

unchanged areas of minority residential concentration in

the school district results in precisely the consequences

which the 1972 Order was intended to prevent: the cre

ation of a set of virtually all-Black elementary schools,

enrolling a substantial proportion of all Black students in

the district at grade levels K-4 or 1-4. Thus, the 1985-86

assignment plan for grades 1-4 uses the same pre-1972

attendance technique (geographic zoning) and many of

the identical pre-1972 zones (modified principally by

school closings) and produces the same segregated, vir

tually all-Black facilities (except for those which were

closed) with which the Court was confronted in 1972.

2. Although the district's schools were desegregated

between 1972-73 and 1984-85, the method of pupil assign

ment was not fully equitable.

The author of the plan embodied in the 1972 decree,

Dr. Finger, testified without contradiction that a lack of

adequate time and information accounted for his place

ment of only a single grade in formerly all-Black schools.

As a result, all young Black children were transported out

of Black residential areas for the first four years of school

228

(after kindergarten), without exception, while white stu

dents in the elementary grades were transported only for

a single year, in the fifth grade.

This inequity was never alleviated, despite the fact

that between 1972-73 and 1984-85 the school board made

numerous modifications to the plan for reasons such as

school closings.

Additionally, the "stand-alone school" feature of the

original Finger Plan, over time, increased the burdens

borne disproportionately by Black children. As new areas

of the district qualified for "stand-alone" status the dis

tances which Black students in grades 1-4 would have to

be transported increased and the likelihood that schools

in Black residential areas would be closed increased.

If, as plaintiffs contend, the school board is unable to

meet its burden of demonstrating adequate legal justifica

tion for returning to a system of geographic zoning to

assign pupils in grades 1-4, a new plan of pupil assign

ment for these grades consistent with the Court's 1972

decree must still be developed by defendants, since the

board has voted to close 7 schools at the end of this year.

Plaintiffs contend that the Court should require that such

a new plan avoid the inequities of the disproportionate

busing of younger Black students, and the threatened

discontinuation of schools in Black residential areas

which results from the Finger Plan's "stand-alone school"

feature.

Even if a new plan of assignment taking account of

the additional school closings did not have to be drawn,

plaintiffs would be entitled to seek modification of the

pupil assignment plan to allocate its burdens more fairly

229

between Black and white students. Such a modification

would facilitate the central purpose of the decree: pre

serving desegregated schools and eliminating discrimina

tory treatment of Black students. The standard for

modifying a decree so as better to achieve its goals is

quite different from that which governs a defendant's

request for the effective dissolution of the decree. Thus,

plaintiffs' right to more equitable means of student

assignment does not imply that the criteria for making

the much more drastic change in the decree sought by the

defendants have been established.

APPENDIX "B"

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA

ROBERT L. DOWELL, et ah, )

Plaintiffs, |

vs. ) CIV-61-945 2-B

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION Of J

THE OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT '

DISTRICT NO. 89, et al., j

Defendant. )

230

DEFENDANT'S CONTENTIONS1

1. The objective in this desegregation case was to

dismantle the dual school system which existed in Okla

homa City. The purpose of the 1972 desegregation decree

was to correct the condition that offended the Constitu

tion. No child was to be excluded from any school on

account of race. The remedy was designed to operate

during the interim period when remedial adjustments

were being made to eliminate the dual system. The need

for the remedy extended until it was clear that state-

imposed segregation had been completely removed.

When the Board's affirmative duty to desegregate was

accomplished and racial discrimination through official

action was eliminated, the Court found the school system

unitary. The Court's unitary finding in 1977 signified the

purpose of the litigation had been achieved. The dual

system had been dismantled. The School District's contin

ued adherence to fundamental tenets of the Finger Plan at

all grade levels through school year 1984-85 further

insured that all vestiges of prior state-imposed segrega

tion had been removed. Today, after 13 years of imple

mentation, the dangers prevented by the 1972 decree

have become attenuated to a shadow. Now, the particular

1 Defendant's contentions, as well as the legal and factual

issues stipulated to in the Pretrial Order, are framed in light of

the mandate of the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Defen

dant Board does not want to be misunderstood as waiving its

previous position in this case. With all due respect to the Court

of Appeals, the Board continues to believe the analysis applied

by this Court in 1985, and applied by the Fourth Circuit in

Riddick v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 784 F.2d 521 (4th Cir.

1986), is the correct one.

231

school a child attends is not determined by race. The

purposes of this litigation as incorporated in the 1972

decree have been fully achieved. The achievement of the

purposes of the litigation constitutes a substantial change

in conditions which warrants dissolving the 1972 decree.

2. The Finger Plan appropriately served its purpose

during the interim period when remedial adjustments

were being made to dismantle the dual school system.

However, the plan was never intended to operate in

perpetuity. After 13 years, demographic changes in Okla

homa City rendered the "stand alone" school feature of

the Finger Plan inequitable. The greater the number of

"stand alone" schools, the greater the busing burden

placed on young black children. More "stand alone"

schools meant less fifth year centers. With demographic

change, the "stand alone" school feature produced hard

ship so extreme and unexpected as to make the decree

oppressive. Such a substantial change in conditions is

additional justification for dissolving the 1972 decree. At

the very least, it warrants modifying the decree to

accomodate [sic] the Board's 1985 plan.

3. The Board of Education's 1985 Student Assign

ment Plan, which calls for neighborhood schools in

grades K-4, does not offend the Constitution. Nor does it

affect the unitary character of the School District. The

Constitution does not mandate that a certain degree of

racial balance be maintained in public schools. Rather, it

prohibits the assignment of students to schools on the

basis of their race. The mere existence of some predomi

nantly white or predominantly black schools in a commu

nity, w ithout m ore, is not u ncon stitu tional. A

neighborhood school policy violates the Equal Protection

232

Clause only when its adoption is motivated by discrimi

natory purpose. The 1985 Student Assignment Plan was

not adopted with discriminatory intent. It was adopted

by a unitary school district for the purpose of avoiding

the progressive inequity of the "stand alone" school fea

ture, and for the purpose of enhancing academic achieve

ment through increased parental and community

involvement in the schools. The faculties at the K-4 neigh

borhood schools are racially mixed. The "majority to

minority" transfer policy insures that no student is com

pelled to attend any school where children of the stu

dent's race constitute a majority. Today, the particular K-4

elementary school a student attends in Oklahoma City is

determined by the housing grades 5 through 12.

5. Any residential segregation which presently

exists in Oklahoma City is not a vestige of previous state-

compelled segregation. The barriers which prevented

black people in the past from living in many sections of

the community have long since been removed. Today,

blacks are free to move, and in fact have moved into most

neighborhoods in this community. Where black families

live in Oklahoma City is now determined by their prefer

ences and socioeconomic status, not by the color of their

skin. The same is true with other minorities. In 1987,

Orientals, Indians, Spanish and blacks are dispersed

through most sections of the Oklahoma City School Dis

trict. They all have the freedom to live and attend school

where they choose. Oklahoma City in 1987 is remarkably

will integrated. The numbers of black people who con

tinue to reside in previous unlawfully segregated neigh

borhoods have decreased over the years. The fact that

233

some of the previous unlawfully segregated neighbor

hoods continue to have a high percent of blacks living

there today is not the result of any action taken by the

Oklahoma City Board of Education. Those people live

where they do by choice. State action, past or present,

does not restrict them from living elsewhere. If it were

not for certain pockets of residential segregation pres

ently existing in Oklahoma City, Plaintiffs would not

have the Board engaged in the present contest. Plaintiffs

would not contest the neighborhood school plan if all

neighborhoods were integrated. Yet, no compulsory

desegregation plan implemented by a public school sys

tem can eliminate residential segregation regardless of

the_Jength of time it is in operation. Under Plaintiffs'

rationale, this Court should continue to order the busing

of young students in Oklahoma City indefinitely, until

such time as racial balance exists in all neighborhoods in

the city. Such action would be oppressive and totally

unrelated to the objective of this desegregation case,

which is to insure that no child of a racial minority is

excluded by school authorities from any school on

account of race.

6. Plaintiffs are not asking this Court to enforce the

Finger Plan. Rather, Plaintiffs are impermissibly asking

this Court to award additional remedial relief, which, for

the first time in the history of Oklahoma City, would

require the compulsory, busing of young white children

in grades 1-4. Plaintiffs' contention that white children

should share the busing burden now because blacks car

ried the burden in the past does not square with princi

ples of equity. In light of the unitary status of the

Oklahoma City School District, it is clear that Plaintiffs

234

may not seek this relief. Since this school district is uni

tary, it no longer has the affirmative duty to desegregate.

Granting such relief would be impermissibly aimed at

eliminating a condition which does not offend the Consti

tution. The Court of Appeals noted that as most Plaintiffs

were limited to seeking the enforcement of the Finger

Plan. The Board of Education contends that implementa

tion of Plaintiffs' busing proposal would: (1) work

extreme financial hardship upon the School District, (2)

adversely affect its "Effective Schools" Program, (3) bring

about another substantial wave of white flight which

would tend to resegregate the School District, and (4)

constitute an abuse of the Court's remedial authority.

7. The School District was declared unitary 10 years

ago, and it remains unitary today. After more than 25

years of litigation, control over the schools in Oklahoma

City should be returned to its Board of Education. Its [sic]

time to turn our attention to effectively educating the

children in this community.

EXCERPTS FROM TRANSCRIPT OF

PROCEEDINGS AT HEARING CONDUCTED

JUNE 15-24, 1987

RECORD, VOLUME II

235

WILLIAM A.V. CLARK

* * *

[p. 45] Q. Were there any changes between 1960 and

1950 that's revealed in these maps?

A. Yes. The area of concentration, the area in which

blacks were concentrated has increased, and there are a

number of tracts with lighter tones in the school district,

but perhaps most obvious was the increase in the north

eastern areas of the school district in which the propor

tions of blacks had increased during this period.

But, in general, between '50 and '60, although there

was some spread, some diffusion, there was still a signifi

cant concentration of black households in the inner city -

the east inner city area.

Q. In your study of this district, were you able to

determine why such a large percentage of blacks were

living in these tracts that are shown on the map in the

dark olive color?

A. Well, in Oklahoma City, as in many other metro

politan areas, there are a complex set of explanations.

We know that blacks settled near the central cities,

the [p. 46] downtowns, where there were jobs available,

and certainly the downtown of Oklahoma City was very

different in 1950 - in the 1950's than it is today when it

was much more of the center of the city. The downtown

has changed a great deal in the last 30 years. And there

were jobs available, so that was one element of explaining

that concentration.

236

Another, of course, is what we do know related to the

preferences and information networks that black house

holds moving to Oklahoma City would have other con

tacts and would tend to find housing nearby. The housing

was less expensive in those central areas, often having

been vacated by other families who had moved out.

And we must, of course, also note that in the 30's

there were ordinances which had the - attempted to

concentrate black households in certain parts of the city.

* * *

[p. 52] DIRECT EXAMINATION (CONTINUED)

BY MR. DAY:

Q. Doctor Clark, you mentioned that the concentra

tion of blacks in the 50's and 60's was, in part, responsible

for the state compelled dual school system being imple

mented in Oklahoma and also ordinances which required

blacks to live within these tracts; is that correct?

A. I'd like that read back. I'm not sure that's exactly

what we were talking about when we ended. We were

talking about the ordinances and the effect of the ordi

nances.

Q. All right. Well you are also aware that there was

a state compelled-dual-school-system -

A. Yes.

Q. - In Oklahoma City for many years?

A. Excuse me. If that's your question, I am aware of

that.

237

Q, Now, after 1970, in your study did you note any

changes in the demographic movement of black people in

this community?

A. Yes. When you look at the maps for 1970 and '80,

you notice considerable change from the maps in 1950

and '60.

Q. Okay. Now, in your investigation, did you

review any local ordinances or state statutes which, in

you opinion, affected where black people could live in

the Oklahoma City area?

A. Yes.

Q. Would you briefly tell us about those local laws?

[p. 53] A. Well, when I found that there had been

these ordinances in the 30's; 1933 and '34, which had been

promulgated, even though I think they were unconstitu

tional, given other court rulings, I was interested to know

what specific responses there had been. So I looked at

some of the other material, and, of course, I think those

ordinances were actually declared - I think "unconstitu

tional" would be the correct word - in the 30's.

But during the 70's, we - beginning, of course, in

1968 with the Federal Fair Housing Rules; these were

followed, specifically, in Oklahoma in 1970 with the Fair

Housing decision and that was followed with a number

of ordinances during the 70's which were designed to

make sure that blacks had access to public accommoda

tion, that there couldn't be discrimination in the housing

market, and these - there were several of these ordi

nances through the 70's, culminating in 80, I think, with

238

the Human Rights Commission that was set up there in

Oklahoma City.

* * *

[p. 55] One of the reasons, if I may just give a little

background, that I do so much of my research in Europe

is that Europe keeps very detailed records on population

relocation. They actually have information on point-to-

point moves. The U.S. does not have very much of this

data.

So when I found some of the data available in a

report that had been done for the school board on actual

relocations of black households, I was interested in map

ping it to see whether or not it would tell us something

about the patterns of change over time for this period in

the 1970's.

Q. Well, tell us a little bit about that study that you

found.

A. I found a study by Steven Davis, a study done by

the - for the school administrative group. I don't know

whether he did it for the school board or whether he did

it for the research group. I think he was a member of

research staff at that time.

And he laboriously took the printed records, - we

didn't have at that time computerized material - he took

the printed records for kindergarteners who lived in the

area of the so-called fifth-grade centers, and he wanted to

know, for the attendance areas of those fifth-grade cen

ters, what had happened to those pupils that were being

bused out of there over time. So he was interested in

knowing three years later, in 1977/78, where were those

239

people that were in those [p. 56] attendance areas in

1974/5, where were they living three years later.

So he actually looked at the matrix of their moves

between attendance areas. He asked, "can I find a name

and address in the attendance area in the center, and now

where were they three years later?"

And I was able to plot that data and present the

record.