Lawler v. Alexander Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lawler v. Alexander Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1981. 82400f0b-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b71b2296-186e-42c8-a436-c9548fb19942/lawler-v-alexander-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J'

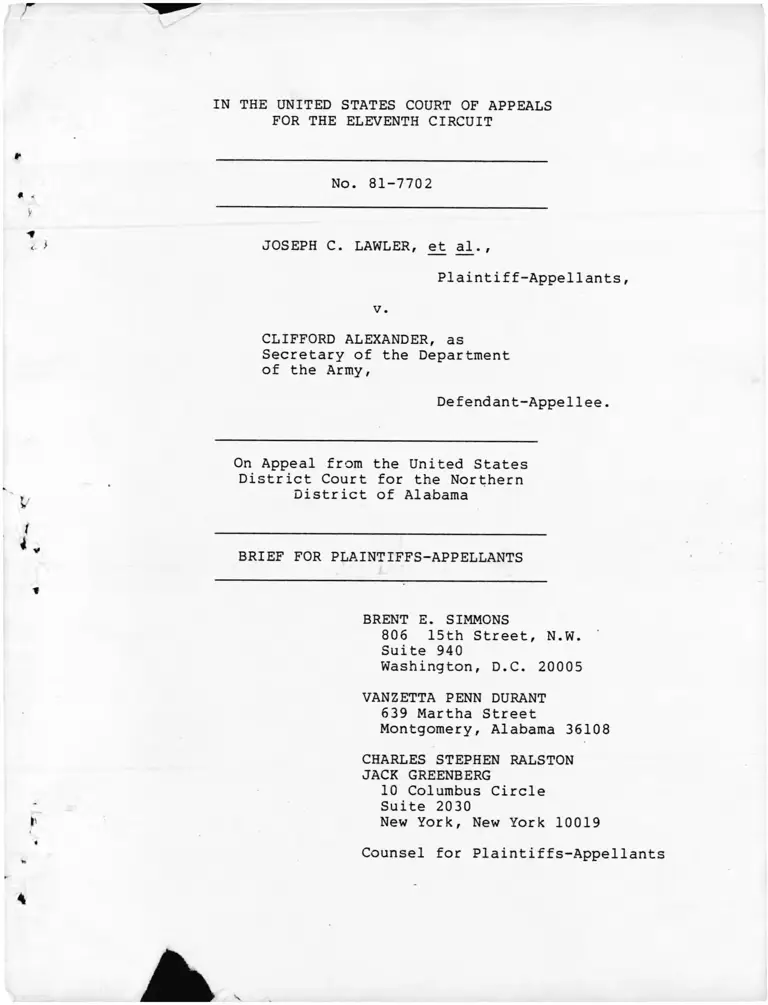

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

r

No. 81-7702« <

i. > JOSEPH C. LAWLER, et al. ,

Plaintiff-Appellants,

v.

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER, as

Secretary of the Department

of the Army,

Defendant-Appellee.

I

V

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Northern

District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

t

BRENT E. SIMMONS

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

VANZETTA PENN DURANT

639 Martha Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36108

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

JACK GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

I' New York, New York 10019

«

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

4

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

Pursuant to Interim Rule 22(f)(2) of the U.S. Court of

Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, counsel for plaintiffs-

* appellants certifies the following as a complete list of

interested parties to this action:

1. As plaintiffs-appellants:

JOSEPH C. LAWLER

TIMOTHY E. GOGGINS

CHARLES L. BRYANT

LOUIE TURNER, JR.

BETTY BAILEY

McCORDIS BARCLAY, JR.

BOBBY L. MURPHY

CLYDE WOODARD

JACK HEATH, JR.

DENNIS R. THOMAS

CHARLOTTE ACKLIN

WAYNE M . GARRETT

9 JEANETTE SIMMONS

RALPH E. DRISKELL

' * 2. As defendant-appellees:

JOHN 0. MARSH, JR., as

' Secretary of the Army

JOHN D. GRANGER, as

Commanding General, Ft. McClellan

DAVID M. PARKER, as

Civilian Personnel Officer,

Ft. McClellan, and his agents.

BRENT E. SIMMONS

Counsel of Record for

Plaintiffs-Appellants

J

1

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

The plaintiffs-appellants request oral argument of this

appeal. This action raises substantial and complex questions

of law regarding the appropriate standards of proof in pat

tern and practice class actions, brought under Title VII of

the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Notwithstanding extensive evidence of gross and increasing

racial disparities in workforce compositions and in promotions

at a federal installation, the district court found no dis

crimination on the basis of erroneous evidentiary standards,

an improperly certified class, and an unduly restrictive

factual inquiry.

Oral argument will facilitate resolution of these issues.

TABLE OP CONTENTS

Page

Certificate of Interested Persons ..................... i

Statement Regarding Oral Argument ..................... ii

Table of Authorities ................................... v

Statement of Issues .................................... 1

Statement of the Case .................................. 2

A. Course of Proceedings and Disposition

in the Courts Below .......................... 2

B. Statement of the Facts ....................... 4

Summary of the Argument ................................ 20

Argument

I. The District Court Abused Its Discretion In

Recertifying The Class To Exclude Non-

ref erred Black Applicants For Promotion ..... 21

II. Plaintiffs' Statistical Evidence Establishes

A Clear Pattern And Practice Of Racially

Discriminatory Treatment Of Blacks In The

Operation Of Defendant's Merit Promotion

System ........................................ 23

A. Plaintiffs' Statistical Evidence

Established A Prima Facie Case Of

Discrimination ............................ 23

B. The Defendant Did Not Rebut Plaintiffs'

Prima Facie Case ......................... 26

C. The District Court's Erroneous Analysis

Of The Evidence .......................... 31

III. Plaintiffs' Statistical Evidence Also

Establishes Adverse Impact In The Operation

Of Defendant's Merit Promotion System ....... 34

- iii -

Page

IV. Defendant's Failure To Take Effective

Measures To Correct The Maldistribution

Of Blacks In Its Workforce Is An Inde

pendent Violation Of Section 717 ............ 35

V. Defendant Failed To Meet The Required

Burden To Rebut The Individual Claims

Of Plaintiff Class Members .................. 42

vConclusion ............................................. 55

iv -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining

Corp., 495 F .2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974) ..... .

Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., Inc.,

500 F .2d 1372 (5th Cir. 1974) ............

Clark v. Alexander, 489 F. Supp. 1236

(D.D.C. 1980) .............................

Clark v. Chasen, 619 F.2d 1330

(9th Cir. 1980) ...........................

Coe v. Yellow Freight System, Inc.,

646 F.2d 444 (10th Cir. 1981) ............

Cross v. U.S. Postal Service,

24 FEP Cases 1603 (8th Cir. 1981) .......

*Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957

(D.C. Cir. 1977) .........................

*E.E.O.C. v. American National Bank,

652 F .2d 1176 (4th Cir. 1981) ............

★Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) ......................

★Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters,

438 U.S. 567 (1978) ......................

★Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)

★Guerine v. J & W Investment, Inc.,

544 F .2d 863 (5th Cir. 1977) .............

★Hazelwood School District v. United States,

433 U.S. 299 (1977) ......................

★International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ......

Johnson v. Uncle Bens Inc., 628 F.2d 419

(5th Cir. 1980) ..........................

42

22

25.34

36

34

44

25,30

23,31,32,35

22,43

28.34

24.35

22

26

24,26,27,30,

25

- v

Page

*Jones v. Cleland, 466 F. Supp. 34

(N.D. Ala. 1978) ................................... 40

*Loeb v. Textron, Inc., 600 F .2d

1003 (1st Cir. 1979) ............................... 44

*McDonald v. United Airlines, 587 F.2d 357

(7th Cir. 1978) .................................... 22

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535

(1974) .............................................. 36

★Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp.,

522 F .2d 333 (10th Cir. 1975) ..................... 23

Rowe v. General Motors Corp.,

457 F .2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972) ...................... 25

★Taylor v. Teletype Corp., 648 F.2d 1129

(8th Cir. 1981) .................................... 40

Texas Department of Community Affairs v.

4 Burdine, 101 S. Ct. 1089 (1981 ) ................... 43,44

★Trout v. Hildago, 25 EPD 1f 31,753

* . (D.D.C. 1981) ....................................... 23,31

★United Airlines v. Evans,

431 U.S. 553 (1971) ................................ 24

United States v. Caceres,

440 U.S. 741 (1979) ................................ 40

★Vuyanich v. Republic National Bank of

Dallas, 505 F. Supp. 224 (N.D. Tex. 1980) ........ 22

- vi

Statutes: Pa9e

Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, P.L. 92-261, § 717 et secj.................. 35,37

Executive Order No. 11246 .............................. 37

Executive Order No. 11478 .............................. 37

5 U.S.C. § 4313 ........................................ 36

25 U.S.C. § 2301 et sea................................. 36

28 U.S.C. §§ 1331; 1343(4); 1361 ...................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 et seq[............................. 2,35,37

Other

Baldus and Cole, Statistical Proof of

Discrimination (1980) ............................... 28

Fed. Rule Civ. Pro. 23 et seq.......................... 22

4

FPM Chapter 335 et seq.................................. passim

43 Fed. Register 38,310 (1978) et seq.................. passim

H. Rep. No. 92-238 (1971)

1972 U.S. Code Cong. Admin. News 2137 .............. 36

- vii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 81-7702

JOSEPH C. LAWLER, et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellants,

v.

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER, as

Secretary of the Department

of the Army

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Northern

District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1. Whether the district court, in a Title VII action,

improperly limited the scope of the class to blacks affected

by only one part of a federal agency's promotion process?

2. Whether the statistical evidence showed a pattern

and practice of discrimination so as to establish a prima

facie case of disparate treatment of blacks with regard to

promotions?

3. Whether the statistical data established that the

defendant's promotional system had an adverse impact on blacks?

4. Whether the defendant carried out his affirmative

obligation, imposed by statute and regulation, to correct

racial imbalance in work force composition and grade levels

and the underrepresentation of black employees at higher

grade levels and across occupational series?

5. Whether the distict court erred in denying the

claims of class members that they had suffered discrimination?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Course of Proceedings and Disposition in the Court

Below

This action was filed on December 20, 1977 and charges a

violation of 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16, as amended 1972 (Title

VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act). Jurisdiction was invoked

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§1331, 1343(4) and 1361. Record (R.) 1-5.

The matter was preliminarily certified on December 20,

1978 as a class action on behalf of all black employees in

competitive service positions at Ft. McClellan who, on and

after November 3, 1976, were discriminatorily denied promo

tions. The class was recertified on March 6 , 1979 to include

all black employees who "have failed to be selected for a

1/position for which they were referred,"- or who have been

misassigned duties, or who have been denied a requested

reclassification. R. 134.

]_/ On January 4, 1979, the defendants moved for decertifi

cation of the class. In the alternative, defendants sought

a redefinition of "promotion" as used in the certification

order, stating that they "would prefer to define 'promotion'

as that term is used in the civilian personnel system."

2

Trial of this action, originally set for December 15,

1980, was twice continued owing to the successive judicial

2/appointments of two of plaintiffs' prior counsel. r . 152—

159. New counsel was substituted in January, 1981. Plain

tiffs subsequently challenged the recertification order as too

restrictive on the issue of discrimination in promotions in a

3/conference with the court on March 26, 1981. Judge Pointer

ruled that he would admit evidence of prereferral discrimination

for its "circumstantial value", but did not modify the scope of

the class. The action went to trial on June 29, 1981.

During six days of trial, plaintiffs challenged various

practices and policies under Ft. McClellan's Merit Placement

V continued

Defendants Memorandum in Support of Class Decertification,

January 4, 1979, p. 6 . Defendants then recommended that the

class certified be defined as: "All black employees.... who

since (November 3, 1976) have been referred for, but not

selected for a promotion...." 1x3. , p. 9. Such a restrictive

use of the term "promotion" was intended to foreclose presenta

tion of claims of discrimination in the "prereferral" stages

of the promotion process.

Nowhere in civilian personnel system regulations is the

term "promotion" so limited as to include only those employees

who are "referred" for selection. Notwithstanding the inaccuracy

of defendant's statement^ the district court amended its

prior certification. R. 134; see also Record Excerpt 16.

2/ The Honorable U.W. Clemon, original counsel of record,

was sworn in as a federal district court judge (Northern

District of Alabama) on July 3, 1980. The case was then

assumed by his former law partner, the Honorable Oscar W.

Adams, Jr., who was subsequently appointed to the Alabama

Supreme Court on October 17, 1980.

3/ See: (1) Defendant's Response to Plaintiff's Second Set

of Interrogatories, filed February 16, 1981, R. 174-188

(noting objections to discovery of "preferral" data, policies,

etc).; (2) Plaintiff's Motion for Order Compelling Production

and Answers and Memorandum in Support, filed March 25, 1981.

R. 189, 190-191.

3

and Promotion Plan, and alleged violations of federal equal

employment opportunity and affirmative action regulations.

In support of both the class and individual claims of racially

discriminatory disparate treatment in promotions, plaintiffs

offered a variety of statistical, documentary and testimonial

evidence. At the close of trial, the court below found against

plaintiffs on all of their class and individual claims. R. 369.

The trial court denied plaintiffs' post-trial motion to

amend judgment and/or certain findings. R. 370-379. The

present appeal was timely filed on August 27, 1981.

B . Statement of the Facts

1. Makeup of the Overall Work Force

Ft. McClellan is a U.S. Army installation located north

and adjacent to the city of Anniston, Alabama. During the

six year period 1975-1980, the workforce of the Anniston

Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) was about 14%

black. See Plaintiffs' Exhibits (P.X.) 2 and 16. During

the same six year period, the Ft. McClellan civilian workforce

(appropriated fund) experienced a net increase in size, from

1,071 in 1975 to 1,343 in 1980. While the proportion of

blacks in the McClellan workforce also increased, it remained

substantially below the Anniston SMSA figure (14%) at 9.5%

4/in 1980.“ The court below so found. Record Excerpts 23-4.

4/ 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980

McClellan

Workforce 1071 1437 1390 1292 1264 1343

Number

Black 75 120 110 96 99 129

Percent

Black 7.0% 8.4% 7.9% 7.4% 7.8% 9.5%

Sources: 1975/76 Ft. McClellan EEO Plans

1977-80 U.S. Army Reports USCS-1136/SAOSA-191

(Both contained in P.X. 1)

4

2 . Relative Distribution of Blacks and White

Despite the increased proportion of blacks, they are

grossly underrepresented at the intermediate and higher grade

4.1/levels, as was also found by the court below.---- Thus, as

shown by the following table, in the years 1975, 1977, and

5/

1980, blacks were disproportionately concentrated in the

lower GS-levels, particularly when compared with white males:

6/Table 1.“

Distribution of White Males, Black Males, White

Females, and Black Females By GS levels , 1975 , 1977 f 1980.

1975

% at

Number Grade or Higher # % # % # %

GS-1 0 100% 0 100% 6 100% 0 100%

GS-2 1 100% 0 100% 10 89 3 100%

GS-3 11 99 1 100% 59 96 2 84%

GS-4 27 95 2 93 08 81 4 74%

GS-5 27 83 7 79 91 53 2 53%

GS- 6 18 70 1 29 28 29 1 42%

GS-7 40 62 1 21 34 23 4 37%

GS- 8 11 44 0 14 21 14 2 15%

GS-9 29 39 1 14 22 9 0 5%

GS-10 8 26 0 7 1 3 0 5%

GS-1 1 28 23 1 7 7 3 1 5%

GS-12 16 10 0 0 4 1 0 0%

GS-1 3 6 3 0 0 0 0 0 0%

GS-1 4 1 0.5 0 0 0 0 0 0%

Total 223 14 391 19

4.1/ See P.X. 1 and 2; also Record Excerpts 24.

5/ These three years were selected as illustrative, occurring

at the beginning, middle and end of the certification period.

Data relating to 1976, 1978 and 1979 are included in P.X. 1.

6/ Source: Derived from Plaintiffs' Ex. 1.

5

%

0 0 %

95

68

45

22

18

18

13

0

0

0

0

0

_0

%

100%

100

87

65

43

21

21

19

17

2

2

0

0

0

0

1977

Number

WM

% At

Grade or #

BM

% #

WF

%

GS-1 1

Higher

1 0 0% 0 1 0 0% 1 1 0 0%GS-2 6 99 3 100 37 99GS-3 7 97 5 88 109 93GS-4 32 94 6 69 150 74GS-5 40 82 3 46 130 47GS- 6 15 66 1 34 42 24GS-7 35 60 3 30 38 17GS- 8 15 46 0 19 19 10GS-9 45 41 4 19 22 7GS-10 8 23 0 3 1 3GS-11 42 20 1 3 16 3GS-12 3 3 0 0 1 0.3

GS-13 6 1 0 0 1 0 .1GS-14 1 0.3 0 0 0 0

Total 256

Number

WM

% At

Grade or

26

1980

#

BM

%

567

#

WF

%

GS-1 0

Higher

1 0 0% 0 1 0 0% 0 1 0 0^

GS-2 3 1 0 0% 3 100 41 100GS-3 11 98 7 90 83 93GS-4 16 95 5 67 147 78GS-5 41 89 5 51 153 53GS- 6 11 74 3 35 50 27GS-7 29 71 3 25 • 41 19GS- 8 11 60 0 16 6 12

GS-9 44 56 2 16 36 11GS-10 6 41 0 9 1 5GS-11 57 39 2 9 25 4GS-12 41 19 1 3 3 0 . 6GS-13 6 4 0 0 0 0.1GS-14 6 2 0 0 1 0.1GS-1 5 1 0.3 0 0 0 0

Total 283 31 587

6

Thus in 1975, while 44% of white male GS employees were

at grade 8 or above, only 14% of blacks, both male and female,

were. On the other hand, only 30% of white males were GS-5

and below, as compared to 71% of blacks males and nearly 64%

of all black employees.

Even if white females (whose distribution has been much

more similar to that of blacks than to white males) are

combined with white males, during the six year period 1975-

1980, blacks were becoming increasingly concentrated in the

lower grade levels, relative to white employees. As noted

above, in 1975, nearly 64% of McClellan's black general

schedule employees were GS-5 or below. By comparison, only

55% of all white GS employees were so rated. By 1980 the

proportion of blacks GS-5 and below increased to over 72%, as

compared to an increase to only 56.9% of white employees.

While the proportion of both blacks and whites in the interme

diate GS- 6 through 9 ranges declined during the six year period

the most revealing change occurred at the GS-10 level and above

While about 6.1% of blacks were GS-10 and above in 1975, only

about 5.6% were in 1980. By contrast, whites increased substan

tially - from about 10.9% in 1975 to over 17% in 1980.

The decline in the relative portion of blacks GS employees

as compared to whites is also shown by Table 2, which gives

the average grade levels for blacks, whites, white males,

and black males for each year:

7/ In 1975 30.4% of the blacks and 33.1% of the whites were

GS- 6 through 9. By 1980, blacks declined 3.1% to 22.3%,

while the proportion of intermediate level whites declined 6.9% to 26.2%.

Table 28/

Average Grade Levels of GS employees, 1975-1980

1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980

white 6 .0 0 4.83 5.83 6.06 6.16 6 .2 0

black 5.40 4.77 4.44 4.66 4.88 5.01

white (m) 7.57 7.44 6.67 8.06 8 . 1 2 8.27

black (m) 5.65 5.37 5.16 5.37 5.53 5.26

With regard to Wage Grade, or blue collar workers, the

same pattern of disproportionate concentration of blacks in

the lower grades when compared with whites, and particularly

white males, is evident.

Table 39/

Distribution of White Males, Black Males, White

Females, and Black Females By WG levels , 1975 , 1977 1980.

1975

WM BM WF BF

% At

Number Grade or # % # % # %

Higher

WG-1 1 100% 1 100% 0 100% 0 100%

WG-2 0 99 2 97 1 100 0 100

WG-3 5 99 2 92 0 97 0 100

WG-4 8 98 9 87 1 97 9 100

WG-5 15 95 6 64 1 93 9 100

WG- 6 29 91 3 49 16 90 0 50

WG-7 38 81 8 41 2 37 1 50

WG- 8 47 69 1 21 9 30 0 0

WG-9 50 53 4 18 0 0 0 0

WG-10 65 37 2 8 0 0 0 0

WG-1 1 41 16 1 3 0 0 0 0

WG-1 2 6 2 0 0 0 0 0 0

WG-1 3 1 0.3 0 0 0 0 0 0

Total 306 39 30 10

8/ Source : Plaintiffs' Ex. 1.

9/ Source : Plaintiffs' Ex. 1.

8

1977

WM

% At

BM WF BF

Number Grade or # % # % # %

Higher

WG— 1 0 100% 0 100% 0 100% 0 100%

WG-2 3 100 2 100 2 100 0 100

WG-3 2 99 5 96 0 93 0 100

WG-4 12 98 13 87 0 93 1 100

WG-5 16 94 13 64 2 93 0 66

WG- 6 29 89 6 41 16 87 1 66

WG-7 39 80 8 30 0 37 0 33

WG- 8 53 69 1 16 10 37 1 33

WG-9 47 52 3 14 1 6 0 0

WG-1 0 86 38 4 8 1 3 0 0

WG- 1 1 33 11 1 1 0 0 0 0

WG-1 2 5 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

WG-1 3 1 0.3 0 0 0 0 0 0

Total 326 56 32 3

WM

Number

% At

Grade or

1980

BM

# %

WF

# % #

BF

%

WG-1 0

Higher

100% 0 100% 0 100% 0 100%

WG-2 1 100 1 100 0 100 0 100

WG-3 4 99 6 97 0 100 0 100

WG-4 3 98 3 85 0 100 0 100

WG-5 17 96 14 79 3 100 0 100

WG- 6 17 90 5 50 10 84 0 100

WG-7 33 84 7 39 1 31 1 100

WG- 8 28 71 5 29 5 26 1 50

WG-9 50 60 2 14 0 0 0 0

WG-1 0 75 41 5 10 0 0 0 0

WG-1 1 . 27 13 0 0 0 0 0 0

WG-1 2 8 3 0 0 0 0 0 0

Total 263 48 19 2

Thus, by 1980, while more than 60% of white males were

at WG-9 and above, only 14% of black males were above WG-9.

These disparities were again reflected in the average grades of

WG workers, which demonstrate a widening of the gap between blacks

9

and whites during the period 1975-1980 similar to that ocurring

among GS employees.

10/Table 4 —

Average Grade Of WG Workers, 1975-1980.

1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980

White 8.24 7.99 8.21 8.38 8.95 8.46

Black 5.86 5.35 5.63 6 .0 0 5.94 6 .0 0

White(m) 8.42 8.14 8.38 8.55 8.50 8.74

Black (m) 5.80 5.32 5.68 6 .0 0 5.89 6.03

The pervasive pattern of white males holding the higher

level supervisory positions is most dramatic when the statistics

for wage leaders and wage supervisors are examined . In 1 975,

there were no black wage leaders out. of a total of 1 1, and only

one black: wage supervisor out of 36. Thus, of all wage board

supervisory positions, blacks held 1 of 47, or 2%, and the one

was at a low level. This was in a workforce where blacks held

10.4% of all wage board positions (50 out of 432), and 12.7% of

wage grade positions (49 out of 385), the source of wage board

supervisory personnel. By 1980 the picture had not changed

noticeably. There were still no black wage leaders (out of 13),

11/and only one black out of 33 wage supervisors.

3. The Operation of the Fort McClellan Promotion

System

Merit promotion for federal civilian employes is governed

by Chapter 335 of the Federal Personnel Manual (FPM) issued

10/ Source: Plaintiffs' Ex. 1.

11/ See Plaintiffs' Ex. 1.

10

by the Office of Personnel Management, as well as by agency

and local regulations promulgated pursuant to Chapter 335.

As a general requirement, those regulations provide:

An agency must adopt adequate procedures to provide equal opportunity in its promotion program for all

qualified employees and to insure that nonmerit

factors do not enter into any part of the promotion

process. Promotions must be made without discrimi

nation for any nonmerit reason such as race, color,

religion, sex, national origin, politics, marital

status, physical handicap, age, or membership in

an employee organization.

FPM 335, Subch. 3-9(a).

Ft. McClellan's present Merit Placement and Promotion

Plan was promulgated in October, 1974 and was last amended

in October, 1976. Since 1976, however, the U.S. Civil Service

Commission — now the Office of Personnel Management — has

issued the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

43 Federal Register 38,310 (1978), and has revised Chapter

335. Ft. McClellan's merit promotion plan does not reflect

the new guidelines.

Ft. McClellan Regulation 690-9 (in evidence as P.X. 26)

is defendant's Merit Placement and Promotion Plan, and provides

in Section I that the Regulation's purpose is to "establish

policies, procedures and guidelines for merit placement and

promotion of civilian employees." Promotions under the regula

tion, in other words, are to comport with specified merit

principles and procedures. Merit promotion procedures consti

tute, essentially, a process of elimination whereby applicants

for an announced position are, at each state of the process,

reduced in number to those few remaining candidates who are

"referred for selection" as the "best qualified. n

Briefly summarized, the process begins with the announce

ment of a position vacancy (Ft. McCl. Form 513-R). Interested

employees submit an Application for Promotion and Internal

Placement Considerations (Ft. McCl. Fm. 35). Applicants are

given performance analysis and appraisals (Ft. McCl. Fm.

424). The civilian personnel office reviews the applications

and eliminates those applicants who do not meet minimum eligibil

ity requirements prescribed by the Office of Personnel Manage

ment (OPM). The remaining "qualified" applicants are then

evaluated on performance and other locally prescribed criteria;

rated - i.e., given a point score, then ranked on the basis of

their scores. Some upper proportion of the "qualified" employ

ees are designated "highly qualified." Usually the top five

"highly qualified" applicants are then "referred" to the select

ing official by being listed on Department of the Army Form

2600 (P.X. 25) as the "best qualified" candidates. The select

ing official is then to record on the Form 2600: (1) his

selection criteria; (2 ) the candidate selected; and (3 ) the

reasons for his selection. The 2600 is then returned to the

civilian personnel office, which is to audit the form to insure

that selecting officials. Officials have complied with merit

principles. See also P.X. 28.

In addition to the foregoing competitive promotion proce

dures, certain promotions can be made as exceptions to competi

tion. See Generally FPM 335, Subch. 4. Career promotions can

occur without competition, for example, when a previously

competitively selected career intern is promoted through an

12

upgrade of the position he occupies, pursuant to a career ladder

program. Promotions can be given until the employee reaches the

top of the career ladder, the "journeyman" level. Civil service

regulations also require noncompetitive promotions for all other

incumbent employees who meet the qualification requirements for

an upgraded position, resulting from job evolution or the

v.

assumption of additional duties above those of the assigned

grade level. FPM 335, Subch. 4-3b.

While ostensibly based on objective merit and job related

principles, Ft. MClellan's Merit Placement and Promotion

Plan places heavy reliance on the subjective appraisals of

civilian personnel office staffing specialists, supervisors

and selecting officials, who are disproportionately white. In

the crucial process of evaluation and rating, for example,

staffing specialists can assign up to 20 out of 100 points

for "excess experience that is clearly related to the job

being filled." Ft. McClellan Reg. 690-9 (P.X. 26), App. C-

la(2). Staffing specialists exercise their own judgment as

to what is "clearly related" and the number of points to be

assigned. also, in violation of the Uniform Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures, up to 20 additional points

can be awarded for formal recognition and training that is

not job related. Trial Transcripts (T.T.) 180. Staffing

specialists also evaluate locally prescribed "highly qualified"

criteria for job relatedness purely on the basis of personal,

subjective judgment. T.T. 252-3; 426. Finally, staffing

specialists utilize subjective judgment in auditing the seletion

13

criteria on the DA 2600's for conformity to merit principle.

There are no standard directives or guidelines by which staffing

specialists may evaluate the selection criteria given on the

2600. T.T. 246? 426. Yet, staffing specialists bear the

primary responsibility for giving verbal guidance to selecting

officials as to appropriate selection criteria. T.T. 203.

During the five years 1976-1980, there were a total of

7,053 applications for promotions - 563 (8%) of which were

from black employees. See Part 1, page 6 of P.X. 36. 51%

of those black applicants were rated "not qualified" at the

outset, as compared to only 46.7% of the white applicants.

Among those employees found minimally qualified, blacks received

a higher proportion of non-referrable "qualified" and "highly

qualified" ratings than whites, 50% vs. 44%. Conversely,

blacks received a statistically significant lower proportion

of "best qualified" ratings that are required for referral and

promotion, — 50% for blacks as compared to 56% for whites.

Eventually, only 24.5% of all black applicants were rated "best

qualified" as compared to 30.1% of all white applicants. Thus,

black applicants for promotion are eliminated from consideration

in substantially greater proportion than white applicants during

the prereferral evaluation, rating, and ranking process.

Even among those applicants rated "best qualified",

some were precluded from further consideration because the

advertised vacancy was either cancelled, abolished, or filled

noncompetitively. Frequently, these "non-standard outcomes"

occurred after the best qualified candidate or candidates

had been referred to the selecting official. During the

- 14 -

five years 1976-1980, there were 876 applications which were

terminated by such non-standard outcomes. (See Part 3, page

6 of P.X. 36.) 82% of black applicants rated "best qualified"

were affected, as compared to only 61% of the white appli

cants rated "best qualified". In at least two instances, a

black applicant had been referred to the selecting official

as the only best qualified candidate before the selecting

official decided to abolish the position. See infra. 46-47.

Mr. David Parker, the Civilian Personnel Officer at Ft.

McClellan, testified at trial that the DA Form 2600 (P.X.

25) should be audited after a selection is made to insure

compliance with merit principles. He also stated that "being

unable to see inside the selecting official's head, the only

audit that we can make are the reasons that are provided on

the 2600 as based upon the selection, and are those reasons

based upon merit." T.T. 231.

In fact, as the testimonies of defendant's own civilian

personnel office officials clearly demonstrate, no serious

effort is made to audit effectively the Form 2600 selection

criteria for compliance with merit principle and equal employment

opportunity, particularly where the selecting official states

no more than his "belief" that the individual chosen is the

best qualified. T.T. 193; 241; 246-8. Recruitment and

Placement Branch Chief Magee testified that the Form 2600

audit is to assure that there are no "flagrant violations"

of merit principle by selecting officials, as for example

where a choice is made "because the person is white". T.T.

15

190-1. But only in an obvious violation of that magnitude

is the 2600 sent back to the selecting official for correc

tive action, and that occurs "rather infrequently," or "once

or twice a quarter." T.T. 200-1. On there other hand, "clearly

subjective" criterion, stating only a "belief" in the absence

of specific merit and job related factors, is usually accep

ted on the assumption that the selecting official's decision

"could have been based on merit". T.T. 192.

During the five years 1976-1980, there were 128 DA Forms

2600 which included one or more black candidates referred

as "best qualified". Blacks were selected from 56 2600's

and whites were selected from the remaining 72. In comparing

the selection criteria, given in these two sets of 2600's,

it is clear that in 43% of the cases where blacks were select

ed over whites, clearly objective merit and job related criteria

were specified, e.g. , "more recent up-to-date experience/

familiarity with heating systems". In only 5% of the cases were

clearly subjective criteria utilized - e.g. , "I believe/feel

this person best qualified". Conversely, in the 72 cases were

whites were selected over blacks, 39% of the cases were based on

clearly subjective criteria. In only 22% of the case were

whites selected over blacks on the basis of objective criteria

which specified merit and job related factors. See P.X.

12/ In reviewing P.X. 37, the Court below stated:

I had gone through to appraise the work product of

plaintiffs' counsel in this regard and find it

16

Under the Uniform Guidelines, federal agencies are

required to "maintain and have available for inspection,

records or other information which will disclose the impact

which its tests and other selection procedurs have upon

employment opportunities (of minorities)... in order to

determine compliance with these guidelines". Sec. 4 U.G.E.S.P.;

43 F.R. at 38297 (1978). The Guidelines provide a framework

for determining the proper use of employee selection procedures

and are "predicted on the principle that the use of a selection

procedure which has an adverse impact (on minorities) is unlaw

fully discriminatory", unless the procedure has been validated

as job related. FPM Letter 300-25 (Dec. 29, 1978), p.2.

At the trial record clearly demonstrates Ft. McClellan

officials have done nothing to comply with the guidelines or

FPM chapter 335. T.T. 1345-1346, 1372. Ft. McClellan's

promotion plan had last been amended in October, 1976 — ■ two

years prior to issuance of the Uniform Guidelines. Notwith

standing the new OPM requirements, no steps have been taken

to collect adverse impact data or to validate the installation's

promotion plan for the job-relatedness of employees selection

procedures. T.T. 1349-50; see also Record Excerpts 60. As

previously noted, Ft. McClellan's current plan utilizes a

12/ continued

generally satisfactory in terms of the attempted

characterizations of the responses and reasons

given for selection or non-selection.

Record Excerpts 33.

17

point system that gives substantial weight to non job-related

criteria in the prereferral ranking of "qualified", "highly

qualified" and "best qualifed" candidates. T.T. 180.

4. The Base's Career Development-Affirmative Action

Program

The evidence established that there has been a failure

at Fort McClellan to utilize effectively training programs

to achieve a balanced workforce or to enhance the career

advancement of blacks. As civil service regulations state,

with respect to internal promotion policy: "As a general

rule when an agency does an effective job of selecting and

training employees, it should have a pool of employees with

potential for career advancement to most positions". FPM

335, Subch. 3-3e(i). Given the foregoing undisputed statistics

of racial imbalance, it is evident that the career potential

and advancement of black employees is not being developed in

an equitable manner.

Two career development programs which are intended to

provide training and opportunity for advancement and pro

motion are Upward Mobility and Civilian Career Programs.

The Upward Mobility program is

... designed to provide encouragement, assistance

and developmental opportunities to lower-level

employees ... in dead-end jobs, in order that they

may have the change in to increase opportunities

for advancement, improve skills, and benefit from

training and education through a program of individual

career development.

Ft. McClellan Equal Employment Opportunity Plan, FY 1977,

Appendix B. During the six years 1975-1980, 23.7% of all

black applicants for Upward Mobility positions were rated

18

"best qualified", as compared to 28.4% of all white applicants

so rated. These figures indicate that the Upward Mobility pro

gram was not being utilized as an affirmative means to correct

the racial imbalance present in the McClellan workforce.

"The civilian career management system provides for

planned intakes of new employees, primarily at the GS 5/7

intern levels, and their development from entrance through

executive levels." Statement of Affirmative Support Federal

Equal Opportunity Recruitment Program (FEORP), 7 March 1980,

Appendix C (P.X.2). The statistics indicate gross underrepre

sentation of minorities in at least 12 of 20 career management

programs for the four years 1977-1980:

Career Programs - Percentage Black

(Total number of participants in parentheses)

Career Program 1977 1978 1979 1980

Civ. Personnel Ad. 7.1 (14) 6.7 (15) 7.1 (14) 6.7 (15)Compt./Financial 0.0 (36) 0.0 (34) 0.0 (35) 0.0 (32)

Safety Mangement 50.0 ( 2) 50.0 ( 2) 50.0 ( 2) 50.0 ( 2)

Supply Mangement 0.0 (10) -- 0.0 (ID 0.0 (10)

Procurement 0.0 ( 3) 0.0 ( 3) 0.0 ( 3) 0.0 ( 3)Education & Train. 2.9 (35) 2.6 (38) 3.2 (31) 9.1 (33)

Material Maint. - — - — - — 0.0 ( 1)Engin./Scientists 0.0 (16) 0.0 (18) 0.0 (16) 0.0 (21)

Intelligence 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1)Librarians 0.0 ( 4) 0.0 ( 4) 0.0 ( 2) 0.0 ( 2)Info./Editorial 0.0 ( 7) 0.0 ( 5) 0.0 ( 5) 0.0 ( 6)

Auto. Data Process 0.0 ( 6) 0.0 ( 6) 0.0 ( 6) 0.0 ( 6)Transportation -— 0.0 ( 4) 0.0 ( 4) 0.0 ( 3)Communications 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1)Manpower and Force 0.0 ( 3) 0.0 ( 3) 0.0 ( 3) 0.0 ( 3)

Housing Management -— 0.0 ( 2) 0.0 ( 3) 0.0 ( 1)Equal Employ. Opp. - — -— -— 100.0 ( 1)Records Management -— -— -— 0.0 ( 1)Commissary -— -— -— 0.0 ( 4)Equip. Specialist 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1) 0.0 ( 1)

TOTALS ALL PROGRAMS 2.1 (146 ) 2.2 (137) 2.2 (138) 4.3 (140)

Sources: 1977/80 U.S. Army Reports (notes 3 and 7, supra)

and Ft. McClellan FEORP Tables, Appendix C. (P.X. 2).

19

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In their prima facie case, plaintiffs presented extensive

statistical, documentary and testimonial evidence of gross

racial imbalances within the Ft. McClellan workforce. In

addition, plaintiffs demonstrated: (1) that defendant's merit

promotion plan is unduly subjective; (2 ) has an adverse impact

on black applicants for promotion; (3) is dominated by a dispro

portionate number of white supervisors and personnel officials;

(4) that the system utilizes racially discriminatory selection

criteria, adverse to equally qualified black candidates; (5)

that defendant has failed to perform adverse impact and job

validation studies required by federal laws and regulations; (6 )

that defendant has denied black employees equal training and

developmental, as well as promotional, opportunities; (7) that

blacks are discriminatorily underclassified; and (8 ) that defen

dant's merit promotion system operates to enhance and perpetuate

racial disparities across grade levels and job series.

Defendant failed to meet its burden to rebut plaintiffs'

prima facie case. The district court, however, ruled against

plaintiffs on the basis of erroneous legal standards and improper

analysis of the evidence. Moreover, defendant failed to satisfy

its burden to provide legally sufficient reasons, or to otherwise

rebut, evidence presented by individual class members.

20

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Abused Its Discretion In Recertifying

The Class to Exclude Nonreferred Black Applicants For

Promotion

In response to a motion filed by defendant, the court

below modified its original certification order and limited

the definition of "promotion" to include only "those employees

who have failed to be selected for promotion for which they

were referred." Record Excerpt 16. Excluded from the class

as redefined are those blacks who apply for promotion but

are discriminatorily evaluated, rated and ranked in the "pre

referral" stages of the promotion process, and are consequently

not referred for promotion. See p. 14.

In the course of pretrial discovery, plaintiffs challenged

the recertification order. See note 1, supra. The court

declined to reconsider its order, but did direct defendant

to respond to discovery requests for "prereferral" data,

since evidence of prereferral discrimination would be admitted

at trial.

Notwithstanding plaintiffs evidence of racially, discrimina

tory adverse impact in the evaluation, rating and ranking of

black applicants for promotion, the court restricted its review

of the evidence as well as its findings, to the limited issue of

discrimination against only those blacks who were referred for

selection. See Record Excerpts, 20-22; 30. Since the certifi

cation was based on an arbitrary definition of promotion, the

district court abused its discretion by improperly excluding

from the class nonreferred black applicants for promotion.

21

The general rule is that a district court's class certifi

cation order is final "unless there is an abuse of discretion,

or the court has applied impermissible legal criteria or stan

dards". Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., Inc., 500 F.2d 1372, 1380

(5th Cir. 1974). In effectuating the nature and intent of Title

VII, "a court should give a wide scope to the act in order to

remedy, as much as possible, the plight of persons who have

suffered from discrimination in employment opportunities".

Id., 500 F.2d at 1380. In the present action, the district

court's arbitrary definition of promotion is clearly an "imper

missible legal criterion", which unduly restricts the scope of

an adequate remedy for those who have been denied equal promo

tion opportunity. A district court is obligated to grant" the

most complete relief possible". Franks v. Bowman, supra, 424

U.S. at 764 (1976). The class certification in this case

violates that standard and must be set aside. See McDonald v.

United Airlines, 587 F.2d 357 (7th Cir. 1978) cert. denied 442

U.S. 934 (1979).

Moreover, "(a) decision as to class certification is

not immutable." Guerine v. J & W Investment, Inc., 544 F.2d

863, 864 (5th Cir. 1977). A court has a continuing duty to

reevaluate class status on the basis of events which develop

as the litigation unfolds," Vuyanich v. Republic National

Bank of Dallas, 505 F. Supp. 224, 233 (N.D. Tex. 1980), and

is empowered to do so under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure

23 (c) (1), up to the point of a decision on the merits.

Given the evidence of prereferral discrimination presented

at trial (see, e.g. P.X. 36), as well as the scope of represen-

22

tation afforded by the trial testi]onies of the class plaintiffs

(most of whom have been subject to the same discriminatory

evaluation, rating and ranking procedures and have been nonre-

ferred on other occasions), the court improperly excluded

nonreferred black applicants for promotion.

The improper denial of the requested class certification

foreclosed plaintiffs from proving the broad based policies of

discrimination in promotion, which formed the basis of their

class complaint. As a result, the district court's order

"curtailed plaintiffs in vindicating their rights". See Rich v.

Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333 (10th Cir. 1975). In

narrowly restricting the issue of promotion discrimination to

only that against blacks referred and not selected, the court

erroneously severed the issue and evidence of prereferral

discrimination and discrimination in the perpetuation of past

racial imbalance, from the issue and evidence of post-referral

discrimination. See also E.E.O.C. v. American National Bank,

652 F.2d 1176, 1198 (4th Cir. 1981); Trout v. Hildago, 25 EPD

31,753 (D.D.C. 1981).

The present class certification must be set aside as an

abuse of the trial court's discretion.

II. Plaintiffs' Statistical Evidence Establishes A Clear

Pattern And Practice Of Racially Discriminatory Treat

ment Of Blacks In The Operation Of Defendant's Merit

Promotion System

A. Plaintiffs' Statistical Evidence Established A Prima

Facie Case Of Discrimination

The uncontroverted statistical evidence amassed by

plaintiffs at trial reflects gross racial disparities and

imbalance within the Ft. McClellan workforce throughout the

23

six year period covered by this action. Moreover, the sta

tistics clearly indicate that the operation of defendant's

merit promotion plan itself has not only perpetuated, but

has also enhanced those disparities - all of which are greater

in 1980 then they were in 1975. A promotion system which

presently perpetuates discrimination violates Title VII.

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430 (1971); United

Airlines v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553, 558 (1977); Teamsters v.

U.S. , 431 U.S. 324, 349 (1977).

The proportion of blacks in the McClellan workforce has

been substantially below that of the local workforce through

out the six year period. See note 4, supra. As the court

below found (Record Excerpts 24), blacks are' concentrated and

overrepresented at the lower levels and grossly underrepresented

at the higher levels. See Tables 1 and 3, supra, pp. 5 and 8 .

There is also gross disparity in the average grade levels of

black and white employees - particularly as between black males

and white males. See Tables 2 and 4, supra, pp. 8 and 10. The

pervasive pattern of black underrepresentation is dramatically

illustrated with respect to supervisory positions - particularly

by Wage Leaders and Wage Supervisors. See p. 10, supra.

In operation, the McClellan merit promotion plan is a

highly subjective system which has a substantial adverse impact

on black applicants for promotion throughout the evaluation,

rating, ranking, referral and selection stages of the promotion

process. Blacks receive less favorable ratings and are elimin

ated from further consideration in greater, statistically

24

significant proportion than is true for white applicants. See

p. 14, supra. They are also subject to discriminatory

treatment in the use of clearly subjective selection criteria,

which favors selection of white applicants in for greater

proportion than blacks. See p. 16, supra; see also, Davis v .

Califano, 613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 1977); Johnson v. Uncle Bens

Inc., 628 F .2d 419 (5th Cir. 1980); Rowe v. General Motors

Corp. , 457 F .2d 348, 359 (5th Cir. 1972).

The adverse impact and discriminatory treatment inhe

rent in the operation of McClellan's merit promotion plan

has never been isolated and corrected by defendant, due to

the failure to conduct the impact analysis and validatioh

studies required by federal regulations. See pp. 17-18,

supra.

Moreover, defendant has failed to utilize career deve

lopment and training programs, specifically designed to afford

advancement opportunities for employees locked into lower grade

level positions, to correct the pervasive and endemic racial

imbalances within the McClellen workforce. See, Clark v. Alex

ander, 489 F.Supp. 1236, (D.D.C. 1980); affirmed and remanded in

part, sub. nom. Clark v. Marsh — F.2d — (D.C. Cir. Sept. 2,

1981). "(I)t would be expected that, absent discriminatory

promotion practices, the proportion of the protected group iji

each of the job classifications and grade levels would approxi

mate the proportion of the protected group with the minimum

necessary qualification for promotion in the employer's labor

force as a whole." Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d at 964 (citing

25

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977)).

Evidence of statistical disparities alone can consitute

prima facie proof of a pattern and practice of employment

discrimination. Hazelwood School District v. United States,

433 U.S. 299, 307-8 (1977). Given the findings of the court

below, that plaintiffs are underrepresented at the higher

14/grades and have lower average grade levels (Record Excerpts

23-4), plaintiffs clearly established a prima facie case

15/soley on the basis of their statistical presentation.

B. The Defendant Did Not Rebut Plaintiffs' Prima Facie

In a pattern and practice suit under Title VII, the

burden on plaintiff class is to "establish by_ a preponderance

of the evidence that the racial discrimination was the (em

ployer's) standard operating procedure - the regular rather than

the unusual practice." (Emphasis added). Hazelwood School

District v. U.S., supra, 433 U.S. at 307; Teamsters, supra,

431 U.S. at 336. Plaintiffs have more than met that burden

in the present action with their showing that defendant's

workforce has continuously reflected gross racial disparities

I V

13/ It should be noted that all blacks in the class as certi

-fied exceed minimum qualifications, having been referred as

"best qualified". Moreover, those blacks not referred generally

met qualification requirements in the evaluation stage unless

the evaluation itself was in some way discriminatory. Also,

candidates referred as "best qualified" are assumed by personnel

officials to be of equal qualification. T.T. 184; 430.

14/ The Court below noted that plaintiffs' statistical proffers

irare of significance and value in support of plaintiffs'

claims that there has been discrimination system at Ft.

McClellan." Record Excerpts 24.

15/ Plaintiffs, did of course, supplement their statistical

evidence with other documentary and testimonial evidence.

26

and imbalance and that its merit promotion plan both perpetuates

16/and enhances those disparities, as discussed above.

"The burden then shifts to the employer to defeat the

prima facie showing of pattern or practice by demonstrating

that the (plaintiffs') proof is either inaccurate or insignifi

cant." Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 360. The employer's defense

must, of course, be designed to meet the (plaintiffs') prima

facie case...." Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 360 n. 46. A review

of the trial record, however, reveals that defendant failed

to meet its burden. Indeed, as previously stated, plaintiffs'

statistical evidence was uncontroverted. The essence of

defendant's case was that once referred for selection, blacks

were selected at a higher rate than whites and that consequently

there was no adverse impact on blacks under Ft. McClellan's

Merit Placement and Promotion Plan. The district court in its

findings followed the same reasoning. See Record Excerpts 60.

Defendant's evidence, however, plainly does not rise to

meet plaintiff's prima facie case. "Affirmations of good faith

in making individual selections are insufficient to dispel a

prima facie case of systematic exclusion." International

Brotherhood of Teamster v. United States, 431 U.S. 341 n. 24

16/ Plaintiffs also presented direct proof of discriminatory

motive, including: (1) a failure to adequately montior and

enforce merit principly in the promotional process, as required

by federal regulation, resulting in adverse impact and disparate

treatment of black employees who apply for promotion; (2) a

failure to validate Ft. McClellan employee selection procedures,

pursuant to federal regualtions; and (3) a failure to support

Ft. McClellan's Equal Employment Opportunity Officer and EEO

program. Finally, plaintiffs presented individual cases of

discriminatory treatment through the testimonies of fourteen

class members.

27

(1977). Moreover, even proof that a workforce is in fact

racially balanced is insufficient alone to rebut a prima

facie showing that an employer's promotion policies were

discriminatorily motivated. See Furnco Construction Corp.

v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567, 580 (1978).

The district court placed heavy, almost exclusive, reliance

on defendant's evidence (D.X. 37 and 38) in concluding that

plaintiffs' prima facie case had been met and in its finding of

no discrimination against the class. See Record Excerpts 30-1;

33-4; 57; 60; 66. In fact, in a curious and legally erroneous

shifting of burdens, the district court states "in essence (it)

found that the results of the defendant's study (introduced

during its case) had not been undermined by PX-36 (introduced in

plaintiffs' case in chief as prima facie evidence)". Record

Exerpts 66. The premise of the prima facie case is that the

claimant presents his or her version of the case and the nature

of the violation. See, Baldus and Cole, Statistical Proof of

Discrimination, (Shepard's/McGraw-Hill, 1980) p. 192. The

burden is on defendant to meet the plaintiffs' case and not vice

versa, as the district court held. Teamsters, supra.

A similar shifting of burdens occurred in Rich v. Martin

Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333 (10th Cir. 1975), wherein the

Tenth Circuit reversed a district court's failure to consider

18/defendant's evidence only in light of the prima facie case.

18/ The Tenth Circuit noted that:

From a reading of the court's findings, it is

apparent that it was defendant's statistics and

other evidence that impressed the court that there

28

The appellate court stated that "the (trial) court's full

acceptance of the defendant's concepts of the case and its

rejection of the plaintiffs' served to curtail plaintiffs'

efforts to vindicate their rights". 522 F.2d at 349.

Similarly here, D.X. 37 and 38 purport to show that

blacks referred for promotion have a selection of rate of

39.1%, as compared to a rate of 31.1% for whites. The court

below concluded on the basis of those figures that:

Obviously such statistics give rise to no inference

of any discrimination against blacks and indeed if

one were simply on a statistical basis to draw any

inference, it would be that whites had been disfavored

in that process. (Emphasis added).

Record Excerpts 31. The proper query should have been whether

defendant's statistics rebutted plaintiffs' prima facie case.

The defendant's evidence and the district court's reliance

on it are based on an obviously misperceived and too restric

tive view of the promotion issue presented by plaintiffs in

. . 19/this case. The central issue is not simply the relative

rates of black and white promotion at one isolated point in

18/ continued

had not been discrimination.... (T)he court should

require the (employer's) evidence either to be

responsive or not to be considered....

522 F.2d at 345-6.

19/ See Record Excerpts 30.

The defendants have produced for the Court some

thing more directly tailored to the actual issues

in the case, namely the number of whites and blacks

found to be best qualified, and in turn in effect

referred for consideration. (Emphasis added).

29

the process, as defendant and the district court would have

it, but the levels and distributions at which those promotions

occur and whether or not they effectuate a proportionately

balanced and representative workforce. See, Teamsters and

Davis v. Califano, supra, p. 25. That is the issue addressed

by plaintiffs' prima facie case and the one to which defendant

offered no rebuttal.

Neither the defendant nor the court seemed particularly

concerned with the impact of the purported selection rates

for blacks on the pervasive racial disparities and imbalance

in the McClellan workforce established by plaintiffs' prima

facie evidence. Indeed, when comparing the average grade of

promotion among blacks selected in D.X. 37 and 38 to the

average grades of all black employees shown in P.X. 1, it

can readily be seen that existing disparities are not only

being perpetuated, but often exacerbated:

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

General Schedule (Blacks)

Avg. Grade Promoted

(D.X. 37/38)

4.33

4.18

4.71

3.86

4.27

Wage Schedule (Blacks)

5.73

6.00

5.29

5.58

6.86

Avg. Grade All

(P.X. 1)

4.77

4.44

4.66

4.88

5.01

5.35

5.63

6 . 00

5.94

6 . 0 0

Thus, higher selection rates at the end of the process not

withstanding, the defendant's evidence only serves to strengthen

plaintiffs' claim that McClellan's promotion system perpetuates

30

discrimination against blacks and that the discrimination is

resulting in greater disparity and racial imbalance within

the workforce.

C. The District Courts Erroneous Analysis Of The Evidence

The districts court's analysis of the evidence at trial

was legally erroneous. "Under a proper analysis, all of the

evidence, statistical and nonstatistical, tending to establish

a prima facie case should first have been assessed on a

20/cumulative basis," followed by an inquiry as to whether

or not defendant's evidence had dispelled the prima facie

case. E.E.O.C. v. American National Bank, 652 F.2d 1176,

1189 (4th Cir. 1981). As previously noted, plaintiffs'

statistical evidence was uncontroverted and defendant failed

to meet his burden under Teamsters, supra, to demonstrate

that the proof was "either inaccurate or insignificant."

21/D. X. 37 and 38 fail to meet plaintiffs' prima facie case.

The district court's analysis also "failed to assess

the evidence in the light of, and colored by, the gross underrep-

20/ See finding of the court that P.X. 37 "does not establish

a prima facie case In and of itself". Record Excerpts 33.

21/ D.X. 37 and 38 are deficient on a number of other grounds,

relating to their probative value and the weight they should

be accorded. First, the exxhibits look only at the final

stage of the promotion process - i.e., they consider only

employee referred for selection. The "disaggregation" of

prereferral discrimiation, demonstrated by plaintiffs, renders

them unreliable as measures of true promotion rates (unlike

plaintiffs' evidence, which is based on qualified applicants

for promotion) and therefore "inherently less probative."

See Trout v. Hildalgo, 25 EPD 131, 753 (D.D.C. 1981). Second,

the data is not stratified in such a way as to assess the

distribution of black promotions across all grade levels.

See argument, supra, p. 30.

31

resentation of blacks in (the) workforce already statistically

demonstrated to the district court's satisfaction." E.E.O.C. v.

American National Bank, 652 F.2d at 1198. Since statistical

imbalance in the McClellan workforce had been clearly estab

lished, it was also important for the court to assess the

operation of the merit promotion plan for its "tendency to

perpetuate an existing condition of underrepresentation." Ici.

Instead, the court approached the evidence as though no such

imbalance existed and consequently "misapplied the controlling

legal principles (see Teamsters, supra, pp. 26-27) to the evi

dence." 652 F.2d at 1198.

In addition to the district court's legally erroneous

analysis of the evidence, the court also based its findings

on highly unreliable data and engaged in improper manipulation

of other statistical data. At trial, plaintiffs' identified

a major coding error in the selection data shown on P.X. 36.

T.T. 311-12. Notwithstanding plaintiffs' argument that the

22/information was unreliable,— the court assumed that the

"relative information concerning whites and blacks selected"

in P.X. 36 is "substantially accurate" when based on a compa-

parison with the figures in D.X. 37 and 38. Record Excerpts

25-26. The Court totally ignores the fact that two different

bases are used in the two sets of exhibits, making such a

direct comparison inappropriate. More importantly, the court

improperly assumed facts that are very much at issue in this

22/ The court is inaccurate in stating that the selection data

in P.X. 36 is "incomplete." See Record Excerpts 69.

32

litigation — i.e., whether defendant's figures reflect pre-

referral discrimination and whether they accurately represent

promotional opportunity across all grade levels and job series

See also the court's improbable combination of data from plain

tiffs' and defendant's exhibits, based on the same set of

assumptions. Record Excerpts, 67.

As part of their claim of discrimination in promotions

at Ft. McClellan, plaintiffs also allege that blacks are

purposefully and discriminatorily assigned permanent duties

"out of grade" — i.e., they are underclassified and under

paid, in greater proportions than white employees, based on

their actual duties and assignments. This is effectively a

denial of promotion, given procedures for noncompetitive

upgrading based on job evolution.

Defendant commissioned a position classification audit

on random samples of black and white Ft. McClellan employees.

D.X. 20-22. The audit clearly shows greater, statistically

significant underclassification of black employees. T.T.

1108. The audit also showed an overclassification of blacks,

which led the court below into legal error:

I am convinced in this situation that the Court

must take into account not only the undergrading,

but also the overgrading, and ascertain what is

the net effect of the errors in grading, recognizing

that the error more frequently has occurred in

this sample with respect to blacks than whites...

when one in effect nets out... (n)o conclusion can

be drawn that there is any adverse impact on the

blacks as a result of the misgrading that certainly

has been shown to occur. (emphasis added).

Record Excerpts 35. Here, the primary focus of the evidence

is on the issue of disparate treatment. Whether or not some

33

blacks were favorably treated with respect to overclassifica

tion, is of no relevance to the issue of discrimination being

practiced against those blacks who were underclassified.

Furnco, 438 U.S. at 579; Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 342 n. 24.

The court's attempt to "net out" "errors" in classification

is to simply disregard the purposeful discrimination underlying

the underclassification of black employees "that certainly

has been shown to occur."

III. Plaintiffs' Statistical Evidence Also Establishes

Adverse Impact In The Operation Of Defendants' Merit

Promotion System

The district court stated at the outset of trial that

it believed this class action to be premised on a theory of

racially discriminatory disparate treatment. T.T. 30. However,

plaintiffs' counsel stated that the evidence would demonstrate

both disparate treatment and disparate (or adverse) impact.

T.T. 27.

The U.S. Supreme Court held that "(e)ither theory may,

of course, be applied to a particular set of facts". Teamsters,

supra, 431 U.S. at 335, n. 15. Consequently:

It is to be understood that these two approaches

to employment discrimination are treated not as

separate claims for relief, but as alternate

grounds for recovery. (Citing Teamster).... It

is necessary, therefore, to consider whether plain

tiff has any right to relief on either of these

theories in light of the evidence in the case.

Coe v. Yellow Freight System, Inc., 646 F.2d 444, 448 (10th

Cir. 1981); Clark v. Alexander, supra.

The evidence presented below demonstrates substantial

adverse impact in the operation of Ft. McClellan's merit

34

promotion plan. Defendant has not rebutted that evidence

with the requisite showing of business necessity or job-related-

ness. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

Given the substantial racial imbalance in the Ft. McClellan

workforce, a proper evidentiary analysis would assess the

tendency of the merit promotion system to perpetuate the

imbalance. Griggs, 401 U.S. at 430; Teamsters, 431 U.S. at

349; EEOC v. American National Bank, 652 F.2d at 1198, supra.

The trial court erroneously failed to consider the

impact of the selection rates in D.X. 37 and 38 on the existing

imbalance. As indicated at p. 30, supra, those rates do in

fact perpetuate existing conditions of underrepresentation.

Based on the substantial evidence of adverse impact

presented below and defendant's failure to rebut that evidence,

the Record clearly supports a finding of adverse impact in

the operation of McClellan's promotion system. The district

court's finding to the contrary is premised on both legal

and clear factual error and must be reversed.

IV. Defendant's Failure To Take Effective Measures To Correct

The Maldistribution Of Blacks In Its Workforce Is An

Independent Violation Of Section 717.

Section 717(b) of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972 imposes on federal agencies a positive obligation to

develop affirmative action plans which must include programs

to provide training so that all employees may advance according

to their potential. (42 U.S.C. §2000e-l6(b )). Similarly,

the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 states that its prohibi

tions against discrimination "shall not be construed to

35

extinguish or lessen any effort to achieve equal employment

opportunity through affirmative action," (25 U.S.C. §2302(d))

and mandates special minority recruitment programs to correct

an underrepresentation of minorities in any job category (5

U.S.C. 5 2 3 0 1(c)). The Act also requires that persons in the

Senior Executive Service be rated on whether they meet affirmative

action goals as well as achieve EEO requirements (5 U.S.C.

§4313). In addition, FPM Chapter 335, subchapter 1-4, provides

that in filling vacancies, agencies have an obligation to

determine and use these sources of employees that are most

likely to "meet the agency's affirmative action goals."

The reason for imposing unique affirmative action obliga

tions on federal agencies was Congress' finding in 1972

that:

[The] disproportionate distribution of minorities

and women throughout the federal bureaucracy and

their exclusion from higher level policy-making

and supervisory positions indicates the government's

failure to pursue ots policy of equal opportunity.

H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92nd Cong. 1st Sess., 1971); 1972 U.S.

Code Congressional & Administrative News, pp. 2137, 2158. H.

Rep. No. 92-238 (92d Cong., 1st Sess.), p. 23 (1971). See

also, Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 546, n. 22 (1974);

Clark v. Chasen, 619 F.2d 1330, 1332 (9th Cir. 1980) ("Congress

was deeply concerned with the Government's abysmal record in

minority employment....").

To correct "entrenched discrimination in the federal

service " (4 Rep. No. 92-238), Congress placed federal agencies

under special requirements to develop and maintain "an affirma

36

tive program of equal employment opportunity" (42 U.S.C.

§2000e-16(b) ).

To accomplish these goals, the Civil Service Commission,

already endowed with the responsibility for eliminating

discrimination in the federal government by Executive Orders

11246 and 11478, was given the duty to require that each

agency and department in the federal government establish an

affirmative action program for the recruitment and advancement

of minorities. 42 §2000e-16(b)(1). Section 717(e) provides

that the Act does not "relieve any government agency or official

of its or his primary responsibility to assure non-discrimina

tion in employment ... or his responsibilities ... relating to

equal employment opportunity ...." Section 717(b) specifically

provides that the plan "submitted by each department, agency and

unit shall include, but not be limited to —

(1) provision for the establishment of training

and education programs designed to provide a maximum

opportunity for employees to advance so as to

perform at their highest potential. ...

Further, pursuant to its obligations under Title VII,

the U.S. Civil Service Commission, now the Office of Personnel

Management (OPM), issued the Uniform Guidelines of Employee

23/Selection Procedures (U.G.E.S.P.) and completely revised

23/ The Uniform Guidelines apply "to employee selection

procedures used in making certain employment decisions,"

including promotion. FPM Letter 300-35 (Dec. 29, 1978), p.

2. They provide a framework for determining the proper use

of employee selection procedures and are "predicated on the

principle that the use of a selection procedure which has an

adverse impact (on minorities) is unlawfully discriminatory,"

unless the procedure has been validated as job related.

See 43 Federal Register 38290, (August 25, 1978) and 5 CFR

300.103(c).

37

Chapter 335 of the Federal Personnel Manual (FPM), which

governs the procedures used for competitive promotions by

all federal agencies. All federal agencies are required to

"maintain and have available for inspection records or other

information which will disclose the impact which its tests

and other selection procedures have upon employment oppor

tunities (or minorities) ... in order to determine compliance

with these guidelines." Sec. 4 U.G.E.S.P. (1978).

As the record of trial below reflects there has been a

total failure to comply with the requirements of the Uniform

Guidelines, revised Chapter 335, and Ft. McClellan's own Merit

24/Promotion Regulation 690-6 (P.X. 26). T.T. 1345-1346, 1372.—

Ft. McClellan's promotion plan had last been amended in October,

1976 — two years prior to issuance of the Uniform Guidelines.

Notwithstanding the new 0PM requirements, neither 0PM nor Ft.

25/McClellan had conducted any adverse impact study— or

24/ The court below stated:

"I can't really make a finding on (the issue of

impact analysis/validation studies) because I do

not recall enough evidence dealing, (sic) and did

not study the regulation in question with a view

to determine whether it is required that an adverse

impact study be conducted."

Record Excerpts 59-60. Again the Uniform Guidelines require

all federal agencies to conduct an adverse impact study.

The failure of the court to make a finding of this crucial

issue, in light of the admissions of defense witness Magee

on cross examination (T.T. 1344-50), is clear reversible

error.

25/ While noting that D.X. 37 and 38 were surveys showing

Favorable selection rates of blacks referred for selection,

Mr/ Magee acknowledged that the surveys were prepared for

38

validated the installation's promotion plan for the job-related-

ness of employee selection procedures. T.T. 1349-50.

Ft. McClellan's current plan utilizes a point system that

gives substantial weight to non job-related criteria in the

prereferal ranking of "qualified", "highly qualified" and "best

qualified" candidates. See p. 13, supra; see also T.T. 180.

Despite the fact that no adverse impact analysis or

validation study was ever conducted at Ft. Mcclellan, defendant

had other evidence of adverse impact. P.X. 1 and 2 (both

prepared by defendant) demonstrate the disproportionate distribu

tion and underutilization of minorities, from 1975 through 1980,

within the Ft. McClellan workforce and across grade levels and

job series. The court below so found, noting that" all of these

matters are, of course, of significance and value in support of

plaintiffs' claims that there has been discrimination in and

about the promotion system at Ft. McClellan". Record excerpts

24. The court below further noted:

The failure of Ft. McClellan to achieve many of

the goals it has set for itself in affirmative action

is not a matter about which the defendants here can

take pride.... [T]he Fort has not achieved the type

of success in its affirmative action plan that one

might hope for.

Record Excerpts 56.

25/ continued

purposes of this litigation, under the instructions of defense

counsel. T.T. 1314, 1344-5. For purposes of an impact analysis

required under the Uniform Guidelines, D.X. 37 and 38 are wholly

inadequate since they do not evaluate the impact of either the

entire selection process or all other individual components of

the total process. Sec. 4C U.G.E.S.P., supra.

39

In Jones v. Cleland, 466 F. Supp. 34 (N.D. Ala. 1978), the

plaintiff presented, as part of her prima facie case, undisputed

evidence of the defendant's knowing failure to comply with its

own affirmative action plan and regulations. The trial court

held:

Due process of law requires an agency of the govern

ment to follow its own rules and regulations. This

requirement was not met. the court is therefore

compelled to find that defendant did discriminate

against the plaintiff by its nonfeasance with

regard to the plan. Further, by evidence of such

disregard, the defendant's intentional discrimination

against the plaintiff has been made out as to her

nonselection... the knowing disregard by the defendant

and his minions of the Veteran's Administration's

own affirmative action regulations manifests intent

on their part. See, Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 (1977).

466 F. Supp. at 38. See also Taylor v. Teletype Corp., supra 648

F.2d 1129, 1135 n. 14. "A court's duty to enforce an agency

regulation is most evident when compliance with the regulation is

mandated by the Constitution or federal law". Unied States v.

Caceres, 440 U.S. 741-749 (1979). Since the Uniform Guidelines

were promulgated to enforce the Fifth Amendment and §717 of Title

26/VII ,they are mandatory and it is the duty of the court to

27/enforce them. The court below also acknowledged that

failure to comply with federal affirmative action regulations is

evidence of discrimination. T.T. 36.

The evidence at trial also reflects a failure by defendant

to support the Equal Employment Opportunity Officer and the

EEO programs. Mr. Louie Turner served as the Equal Employment

26/ As the Uniform Guidelines provide: "These guidelines

will be applied... by the Civil Service Commission and other

Federal Agencies subject to section 717 of Title VII...".

Sec. 2 U.G.E.S.P.

27/ The same line of reasoning would apply to Ft. McClellan's

40

Opportunity Officer (EEOO) at Ft. McClellan for nearly seven

28/years — from March, 1974 through January, 1981.— At trial

Mr. Turner testified concerning the failure of the installation's