Thomie v. Dennard Reply Brief for Defendant-Appellees

Public Court Documents

December 2, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thomie v. Dennard Reply Brief for Defendant-Appellees, 1970. ac61ad0a-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b754e7fa-123f-41f7-bb7f-7f9edbf6fd11/thomie-v-dennard-reply-brief-for-defendant-appellees. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

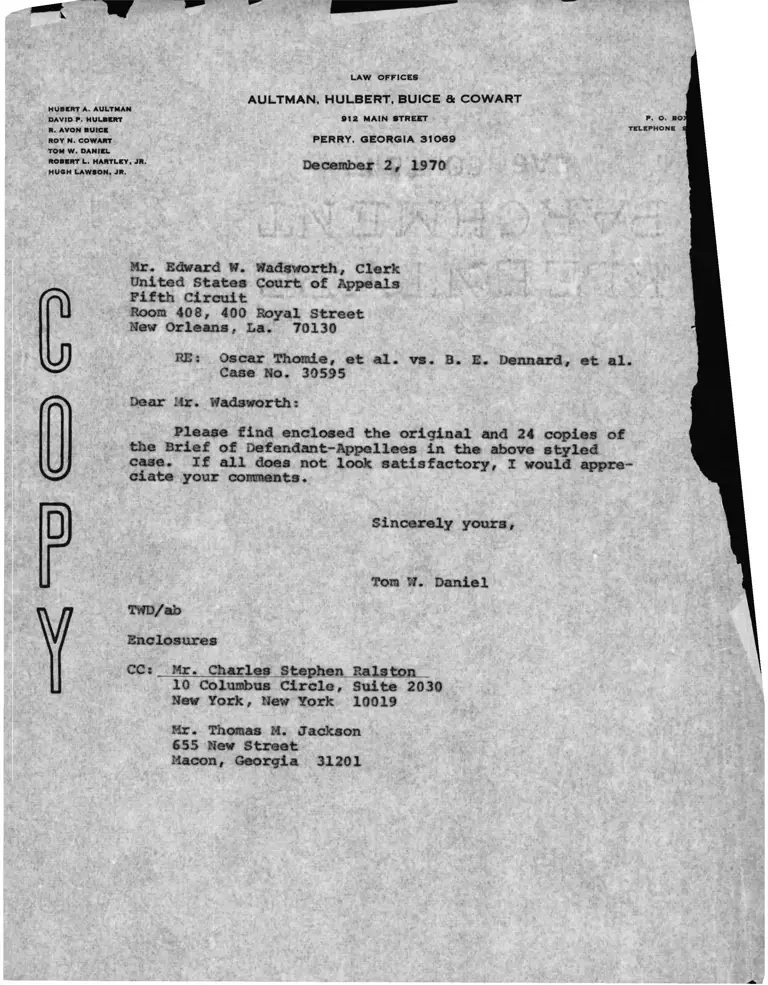

L A W O F F IC E S

H U B E R T A . A U L T M A N

D A V ID P . H U L B E R T

R . A V O N B U IC E

R O Y N . C O W A R T

T O M W . D A N IE L

R O B E R T L . H A R T L E Y , J R .

H U G H L A W S O N , J R .

A U L TM A N , H U L B E R T , B U IC E 6c C O W A R T

912 MAIN STREET

P E R R Y , G E O R G I A 3 1 0 6 9

December 2, 1970

P . o . B O

TELEPHONE

Mr. Edward W. Wadsworth# Clerk

United States Court of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

Room 408, 400 Royal Street

New Orleans, La. 70130

RE: Oscar Thomie, et al. vs. B. E. Dennard, et al.Case No. 30595

Dear Mr. Wadsworth:

Please find enclosed the original and 24 copies of

the Brief of Defendant-Appellees in the above styled

case. If all does not look satisfactory, I would appreciate your comments.

Sincerely yours,

Tom V. Daniel

TWD/ab

Enclosures

CC: Mr. Charles Stephen Ralston

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Mr. Thomas M. Jackson

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

I N D E X

Page

STATEMENT OF FACTS....................................... 1

ARGUMENT ............................................... 4

A. The Court Below Did Not Err In Holding That

It Was Barred From Issuing A Declaratory Judg

ment Regarding the Constitutionality of the

City Ordinance................. 4

B. The Court Below Did Not Err in Not Holding the

Perry Parade Ordinance Unconstitutional On Its

Face............................................. 8

C. The Court Did Not Err In Finding There Was No

Use of Violence By Law Enforcement Officers

Against the Arrested Demonstrators.............. 14

CONCLUSION............................................ 15

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE.................................. 19

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Amalgamated Food Employees vs. Logal Valley Plaza,Inc.391 U.S. 308, 88 S.Ct. 1601............................10

American Federation of Labor vs. Watson, 327 U.S. 582,66 S.Ct. 761, 90 L.Ed. 873 (1946)...................... 6

Carter vs. Gautier, 305 F.Supp. 1098 (M.D. Ga. 1969). . . . 5

Cox vs. The State of New Hampshire, 312 U.S. 569, 574,

85 L.Ed. 1049, 1052 (1941).............................. 10,11

Dombrowski vs. Pfister, 380 U.S. 491, 85 S.Ct. 1116 . . . .5,6,11,15

Douglas vs. Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157, 87 L.Ed. 1324(1943). . 5

Hague vs. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496, 59 S.Ct. 954.............. 11

LeFore vs. Robinson, F.2nd. 5th Cir....................... 8,9

McLucas vs. Palmer, 38 Law Week 2665...................... 5

Poulos vs. The State of New Hampshire,345 U.S.395 ........ 11

Shuttlesworth vs. The City of Birmingham, 394 U.S.152,

89 S.Ct.935 ............................................12,13

Wells vs. Hand, 238 F.Supp. 799 ..........................6

Wells vs. Reynolds, 382 U.S. 39, 86 S.Ct.160.............. 6

Statute

Ga. Code §64-107 9

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 30595

OSCAR THOMIE, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

B. E. DENNARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The Appellants in their statement of facts alleged as if

undisputed that on a number of occasions the prisoners after

being arrested were sprayed with some type chemical, both while

on the buses used to haul them to the jail and while in the

jail. Throughout the lengthy testimony none of the Appellants

could specifically state what type chemical they were supposedly

-1-

sprayed with or specifically what officer or person sprayed

them. Chief of Police Dennard in his testimony categorically

denied the use of chemicals or any type of spray or chemical

agent on any person or persons. (A, 316-318)* Likewise,

State Trooper John W. Wright, who was present during the

arresting and transporting of the Appellants, denied using

any chemical or seeing any chemical being used or having

any chemical substance in his possession or knowing of

anyone who had any chemical substances in their possession.

(A, 359)* State Trooper John Hammock likewise testified that

he did not use nor did he see anyone use any chemical agent

or agents against any of the Appellants and likewise that

he did not see any chemical agent or agents present that

could have been used. (A, 363)* In the statement of facts,

Appellants likewise set out as being uncontested that the

prisoners were in some manner mistreated at the prison.

State Trooper John Hammock, who was one of the troopers who

unloaded the buses and made a search of the male prisoners

prior to incarceration, denied any mistreatment or wrongful

treatment of any of the prisoners by himself or anyone

present. (A, 365)*

Appellants' statement of facts does not set out that

during the period of time when the arrests were being made

jV A-Refers to Appellants' Appendix A.

-2-

the merchants and stores in downtown Perry were being boy

cotted and the boycott continued up until the time of the

hearing without incident, with no arrests being made and

no harassment of the persons doing the boycotting. Likewise,

the statement of facts does not make reference to all the

testimony given by the Appellants that they were not afraid

to participate in the boycott or the marches and should they

decide to march again each of them would march with or with

out a permit and each had no fear of reprisals against them.

(A 123, 161, 178, 187, 197)

Appellants' statement of facts would lead one to believe

the testimony concerning the tense situation which existed

between the races at the time of the parades was of little

or no importance. However, the testimony of all persons

clearly shows a very tense situation did in fact exist

between different segments of both races during the time

following the immediate integration of the schools along

with the continuing boycotts. In fact the governing author

ities recognize the situation as being so tense that they

felt it necessary to ask for and did receive additional law

enforcement support in the form of State Troopers.

-3-

A R G U M E N T

THE DECISION OF THE COURT BELOW DOES NOT CONFLICT

WITH THE LAW OF THIS CIRCUIT AS ENUNCIATED IN

LeFORE VS. ROBINSON

The statement of facts along with the evidence presented

in this case before the District Court establish that there

are great differences between this case and other cases which

have been before this Court and that this case should be de

cided on the law and facts as presented here and not as if it

were just another in a series of cases as set out in Appellants

argument.

A. The Court Below Did Not Err In Holding That It

Was Barred From Issuing A Declaratory Judgment

Regarding the Constitutionality of the City

Ordinance.

The decision of the District Court does, not state that it

could not, but rather that it should not grant the declaratory

relief requested. Directing the court's attention to the decision

of the Federal District Court (A, 427) , the Lower Court recog

nizes that the declaratory judgment must be considered indepen

dent of the propriety of the issuance of an injunction. Likewise

the Court realizes that a declaratory judgment must not be

granted just because one is requested but in fact must

be one felt necessary by the court in its discretion. The

court basing its decision on McLucas vs. Palmer, 38 Law Week

2665, quoting:

"This important rule of federalism cannot be cir

cumvented by seeking a declaratory judgment in

addition to or in lieu of an injunction. That_

has been squarely held with respect to the anti

injunction statute, 28 U.S.C. §2283.*** A declara

tory judgment would create the same opportunity

as an injunction for delay and disruption of the

state criminal proceeding and the same danger of

having federal courts plunge themselves into the consideration of issues that may prove academic

or at least may appear in a different light after

trial."

This principle of federalism is discussed further

in Carter vs. Gautier, 305 F.Supp. 1098 (M.D. Ga.

1969) (three judge court), and in Wells vs. Hand,

238 F.Supp. 779 (M.D.Ga. 1965) (Three judge court),

affirmed 382 U.S. 39, 15 L.ed. 2d 32 (1965). And

see Douglas vs. Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157, 87 L.ed.

1324 (1943)”

In the arguments before the lawer court, Dombrowski vs.

Pfister, 380 U.S. 491, 85 S.Ct. 1116, was the case most

heavily relied on by Appellants. However, the court in

handing down the decision realizing the serious step which

it was taking stated:

"Since that decision, however, (Ex parte Young, 209

U.S. 123, 28 S. Ct. 441, 52 L.Ed. 714) considera

tions of federalism have tempered the exercise of

equitable power, for the court has recognized that

federal interference with a State's goodfaith ad

ministration of its criminal laws is peculiarly

inconsistent with our federal framework. It is

generally to be assumed that state courts ̂ and

prosecutors will observe constitutional limitations

as expounded by this court, and that the mere

possibility of erroneous initial application of

constitutional standards will usually not amount

-5-

to the irreparable injury necessary to justify a

disruption of orderly state proceedings."

Because of the particular facts in Dombrowski the court

recognized that if the federal court did not intervene, the

plaintiffs would suffer great and irreparable injury. Second,

the court recognized that should it not intervene there would

be a "chilling effect" upon the exercise of the first amend

ment rights. That the court intended strict limitations and

interpretation should be placed on Dombrowski is clearly in

dicated by the U. S. Supreme Court's per curiam affirmance

after Dombrowski, of Welds vs. Hand, 238 F.Supp. 799, and

Wells vs. Reynolds, 382 U.S. 39, 86 S.Ct. 160. In these

cases the district court denied injunctive relief from

criminal prosecution of a Georgia law. The district court

in Wells vs. Hand, addressing itself to this question stated:

"There has been no showing that these plaintiffs

will not be afforded adequate protection with

respect to their contentions in the state court.

As already noted, the alleged invalidity of a

state law is not of itself grounds for equitable

relief in a federal court. The controlling

question is whether the plaintiffs have made a

sufficient showing that the need for equitable

relief by injunction is urgent in order to pre

vent great and irreparable injury. American

Federation of Labor vs. Watson, 327 U.S. 582, 66

S.Ct. 761, 90 L.Ed. 873 (1946). The injunctive

relief sought in this complaint against the en

forcement of a state penal statute, even if that

statute is contrary to the federal Constitution,

-6-

must be measured by the extraordinary circumstances

rule and considerations of whether the danger of

irreparable loss is both great and immediate. The

mere fact that the plaintiffs may be convicted in

the state court does not create such extraordinary

circumstances as would justify an injunction and

it has been frequently held that a federal court

should not ordinarily interfere with state officers

charged with the duty of prosecuting offenders

against state laws."

The facts in the case before this court clearly indicate

that there has been no "chilling effect" upon the exercise

of the plaintiffs' first amendment rights. Plaintiffs have

been issued permits several times for parades and have pic

keted undisturbed from the time of the first arrest in ques

tion to the present date.

The record also shows that all of the plaintiffs who

are defendants in the Mayor's court are presently out on

bond and the court has continued the prosecution of all the

cases with the exception of the first ten who were tried and

convicted so the attorney for the plaintiffs could take the

proper steps to test the constitutionality of the ordinances

in question in the state courts.

Therefore, under Domb row ski the federal district court

in this case should not intervene and issue an injunction in

the criminal prosecutions of the persons charged with viola

ting the municipal ordinances of Perry.

-7-

B. The Court Below Did Not Err in Not Holding The

Perry Parade Ordinance Unconstitutional On Its

Face.

The Appellants in the Lower Court argued that the

ordinance was unconstitutional on its face in that it was

overbroad and vague and, therefore, unconstitutional. It

is only since the appeal that the que.stion has been raised

concerning the constitutionality of the ordinance for lack

of a prompt commission initiated judicial review. The trial

court did not pass on the point that the Appellants have

presently brought before this court., T.herefore the constitu

tional question raised in the Lower Court is not presently

for review and the question that the Appellants have brought

before this court on constitutionality being first raised on

appeal should not be considered.

Appeallants rely heavily on the recent case of LeFore

vs. Robinson, F.2nd. 5th Cir., Nov. 12, 1970, attacking the

ordinance in question as failing to provide for immediate

court review of a denial of the permit. LeFore is distin

guished in that the District Court did not conduct an

evidentiary hearing, whereas in this case the District Court

held a very lenghthy two-day evidentiary hearing in which

Appellants and Appellees were given an opportunity to present

all the evidence they so desired.

-8-

In LeFore there was no provision for immediate judicial

review.

In this case immediate review is provided for by state

statute.

Ga.Code §64-107 - Upon the presentation of an

application for mandamus, if the mandamus nisi

shall be granted, the judge shall cause the

same to be returned for trial not less than 10

nor more than 30 days from said date; the de

fendant to be served at least five days before

the time fixed for such hearing. If the answer

to said mandamus nisi shall involve no issue

of fact, the same shall be heard and determined

in vacation, unless court shall then be in

session, when it may be determined in the superior

court. (Acts 1882-3, p.103)

This statute clearly provides for a speedy hearing by

the judiciary should the decision of the City Council ne

cessitate review. There is no need for the ordinance to

contain a section establishing judicial review when such a

law is in existence and readily available to Appellants.

Therefore, both the facts and the law in the LeFore

case are totally and completely different from the facts of

the ]aw that exist in this case and have no bearing whatsoever

on this case.

Notwithstanding the above argument and without any con

cessions, Appellees feel that the constitutionality of the

ordinance on the original ground raised before the District

Court should be discussed.

-9-

The courts throughout have recognized that municipalities

are entitled, within limits of equal enforcement, to establish

a means of control over its public highways and the traffic

thereon and the people using the same.

"Civil liberties, as guaranteed by the Constitu

tion, imply the existence of an organized society

maintaining public order without which liberty

itself would be lost in the excesses of unres

trained abuses. The authority of a municipality

to impose regulations in order to assure the safety

and convenience of the people in the use of public

highways has never been regarded as inconsistent

with civil liberties but rather as one of the means

of safeguarding the good order upon which they ul

timately depend. The control of travel on the

streets of cities is the most familiar illustration

of this recognition of social need. Where a

restriction of the use of highways in that relation

is designed to promote the public convenience in

the interest of all, it cannot be disregarded by

the attempted exercise of some civil right which

in other circumstances would be entitled to pro

tection. One would not be justified in ignoring

the familiar red traffic light because he thought

it his religious duty to disobey the municipal

command or sought by that means to direct public

attention to an announcement of his opinions. As

regulation of the use of the streets for parades

and processions is a traditional exercise of

control by local government, the question in a

particular case is whether that control is exerted

so as not to deny or unwarrantedly abridge the

right of assembly and the opportunities for the

communication of thought and the discussion of

public questions immemorially associated with

resort to public places." (emphasis added) Cox

vs. New Hampshire, 312 U.S. 569, 574, 85 L.Ed.

1049, 1052 (1941).

The Supreme Court in a most recent case, Amalgamated Food

Employees vs. Logal Valley Plaza, Inc., 391 U.S. 308, 88 S.Ct.

-10-

1601, recognized the right of a municipality to control parades

and picketing stating:

"Even where municipal or state property is open

to the public generally, the exercise of first

amendment rights may be regulated so as to pre

vent interference with the use to which the property is ordinarily put by the state. . . . "

"In addition, the exercise of first amendment

rights may be regulated where such exercise will

unduly interfere with the normal use of the pub

lic property by others of the public with an

equal right of access to it. Thus, it has been

held that persons desiring to parade along city

streets may be required to secure a permit in

order that municipal authorities be able to

limit the amount of interference with use of

sidewalks by other members of the public by

regulating the time, place and manner of the

parade. Cox vs. The State of New Hampshire,312

U.S. 569: Poulos vs. The State of New Hampshire,

345 U.S. 395."

The U. S. Supreme Court stating:

" . . . the privilege of a citizen of the United

States to use the streets and parks for communi

cation of views on national questions itiay be

regulated in the interest of all: it is not

absolute but relative and must be exercised in

subordination to the general comfort and conven

ience and in consonance with the peace and good

order; but it must not in the guise of regula

tion be abridged or denied." Hague vs. C.I.0.,

307 U.S. 496, 59 S.Ct. 954.

again recognized the right of a municipality to control its

streets and sidewalks for the general comfort and convenience

of all the people so long as such control was not being used

as a guise to prohibit the enjoyment of first amendment rights.

-11-

Plaintiffs attack the ordinances involved as being over

broad and vague to such an extent as to render said ordinances

unconstitutional. Shuttlesworth vs. The City of Birmingham,

394 U.S. 152, 89 S.Ct. 935, must be distinguished from the case

at hand in that the discretion to issue or not issue a permit

was vested not with the City Council and Mayor as in the pre

sent case, but was delegated to some lesser officials of the

City of Birmingham. Secondly, the city officials of Birmingham

had stated openly that they did not intend to allow any parades

or demonstrations. The court took judicial notice of the

evidence offered in a prior case since both cases arose out

of the same question of facts and stated the following:

"Uncontradicted testimony was offered in Walker

to show that over a week before the Good Friday

march petitioner Shuttlesworth sent a represen

tative to apply for a parade permit. She went

to the City Hall and asked "to see the person

or persons in charge to issue permits, permits

for parading, picketing, and demonstrating."

She was directed to Commissioner Connor, who

denied her request in no uncertain terms. "He

said, 'No, you will not get a permit in

Birmingham, Alabama to picket. I will picket

you over to the City Jail,' and he repeated

that twice." 388 U.S., at 317, N. 9, 325,335,

339, 87 S.Ct., at 1830, 1834, 1839, 1841.

Two days later petitioner Shuttlesworth himself

sent a telegram to Commissioner Connor request

ing, on behalf of his organization, a permit to

picket "against the injustices of segregation

and discrimination." His request specified the

-12-

sidewalks where the picketing would take place,

and stated that "the normal rules of picketing"

would be obeyed. In reply, the Commissioner

sent a wire stating that permits were the re

sponsibility of the entire Commission rather

than of a single Commissioner, and closing with

the blunt admonition: "I insist that you and

your people do not start any picketing on the

streets in Birmingham, Alabama." Id., at 318,

N. 10, 325, 335-336, 339-340, 87 S.Ct., at 1830,

1834, 1839-1840, 1841-1842.

These "surrounding relevant circumstances" make

it indisputably clear, we think, that in April

of 1963, at least with respect to this petitioner

and his organization, the city authorities thought

the ordinance meant exactly what it said. The

petitioner was clearly given to understand that

under no circumstances would he and his group be

permitted to demonstrate in Birmingham, not that

a demonstration would be approved if a time and

place were selected that would minimize traffic

problems. There is no indication whatever that

the authorities considered themselves obligated

as the Alabama Supreme Court more than four years

later said that they were— to issue a permit

"if after an investigation [they] found that the

convenience of the public in the use of the

streets or sidewalks would not thereby be unduly

disturbed." Shuttlesworth vs. The City of

Birmingham, Alabama, 89 S.Ct. 935.

Comparing Shuttlesworth with the present case, it will

be noted that the right to issue a permit rests solely with

the Mayor and City Council of Perry who are likewise the body

that enacts the ordinances and, therefore, any detailed guide

lines that they might enact, could likewise be changed at any

time. The requirement for the issuance of a permit that a

request be made at least two weeks prior to the intended date has

-13-

on a number of occasions been waived by the Mayor and City

Council allowing the plaintiffs and other members of the

black community to have a permit to parade per their request.

There is no evidence that the Mayor and City Council refused

to issue a permit arbitrarily. There is no evidence to show

that the Mayor and City Council refused to issue plaintiffs

a permit in order to deny them any of their constitutional

rights.

C. The Court Did Not Err In Finding There Was No

Use of Violence By Law Enforcement Officers

Against the Arrested Demonstrators.

It is assumed by the Appellants that violence was used

by the law enforcement officers against the arrested demon

strators and that the trial court ignored the use of said

violence. However, the facts are that the lower court heard

all the testimony of both the Appellants and Appellees and

the assumption must in fact be that the lower court found as

a matter of fact that there was no use of violence by the law

enforcement officers rather than the assumption the Appellants

would have the court believe it made no finding whatsoever.

It was certainly in the District Court's sound discretion

after hearing the facts as presented by both sides to make a

finding of fact and I believe that it goes without saying that

had the District Court found the use of violence it would not

have ignored such but would have addressed itself to the same.

-14-

The testimony was certainly contradictory as to whether

or not any violence by the police officers occurred and it

was clearly in the court's discretion as the finder of fact

to make such a decision.

CONCLUSION

The plaintiffs in their complaint alleged they had no

plain, adequate or complete remedy at law to redress the

violations of their constitutional rights other than a suit

for injunctive relief and declaratory judgment in the federal

district court. The plaintiffs failed to introduce one

scintilla of evidence in support of this claim. The evidence

showed they have a complete and adequate remedy within the

State Courts. The municipal court has even agreed to con

tinue the prosecution of all the cases with the exception of

the first ten until such time as the plaintiffs have been

able to test the constitutional question raised. The require

ments set down in Dombrowski allowing the federal court to

intervene and enjoin criminal prosecutions are not met by

the facts in the present case. Plaintiffs will suffer no

injury by the refusal of the federal district court to inter

vene in the present case; therefore, no irreparable injury.

Without exception, plaintiffs' witnesses testified they would

-15-

have no hesitation whatsoever in requesting a permit from

the city to parade. Clearly from this testimony there has

been no "chilling effect" upon the plaintiffs' first amend

ment rights. Likewise, there is no evidence to indicate

that any remedy other than intervention by the federal court

would be unavailing to the plaintiffs. It cannot be assumed

that the state courts would fail to hold the ordinance un

constitutional if the same were in fact unconstitutional.

The valid presumption is that the outcome in the state court

would be the same as the outcome in the federal courts.

The evidence is clear that the Mayor and City Council

at no time delegated their authority to anyone to decide

when and when not to issue permits. Likewise, the discretion

exercised by the Mayor and City Council under the evidence

shows that at no time was an arbitrary decision made but

that each decision on whether to issue a permit or not and

what route to be allowed was based on a sound, logical and

reasonable basis. Plaintiffs themselves testified that the

parades were in the size of 600 to 1500 persons and they

expected the parades to continue in that size. The testimony

of one plaintiffs' witness was that a parade of that size

would take approximately 2 hours to complete. Under such

circumstances, there can be no doubt that the city has not

-16-

only the right but the duty to its other citizens to exercise

control over its streets and sidewalks. Without a doubt

every person has an equal right to use the streets and side

walks and likewise every person has an equal responsibility

not to block or interfere with the streets and sidewalks in

such a manner as to deprive other persons of their right to

use the sidewalks.

The first amendment rights that plaintiffs assert are

strictly individual rights. When the individuals become

groups or mobs, certainly the first amendment rights must

give way in some degree to the rights of other individuals

who are protected by the municipality. Clearly if a group

or mob of individuals numbering in the hundreds obstructs

the sidewalks and streets in such a manner that other indi

viduals, regardless of their color, are thereby prevented

from using the streets and sidewalks then the group would

have encroached upon the individual the same as the plaintiffs

contend the municipality has encroached on their rights.

The testimony before the court, without contradiction,

proves that there was a great deal of tension and hostile

feelings between the two racial groups in the City of Perry

and only through restraint on both sides, coupled with the

excellent job done by the local law enforcement officers, was

violence abated.

-17-

In conclusion, Defendants-Appellees urge that this

appeal be dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

Tom W. Daniel

OF COUNSEL:

Aultman, Hulbert, Buice & Cowart

Attorneys at Law

912 Main Street

Perry, Georgia 31069

-18-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

ihj.s is to certify that I have this day served counsel

for tne opposing party in the foregoing matter with this

pleading by depositing in the United States Mail a copy of

same in a properly addressed envelope with adequate postage

thereon.

T^ls ^ daY °f December, 1970.

Tom W. Daniel

Attorney for Defendant-Appellees