Wilder v. Lambert Motion for Leave to Proceed in Forma Pauperis

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1983 - January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Wilder v. Lambert Motion for Leave to Proceed in Forma Pauperis, 1983. 23559aca-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b7608952-b1f7-4604-8c95-09b729697dfb/wilder-v-lambert-motion-for-leave-to-proceed-in-forma-pauperis. Accessed February 09, 2026.

Copied!

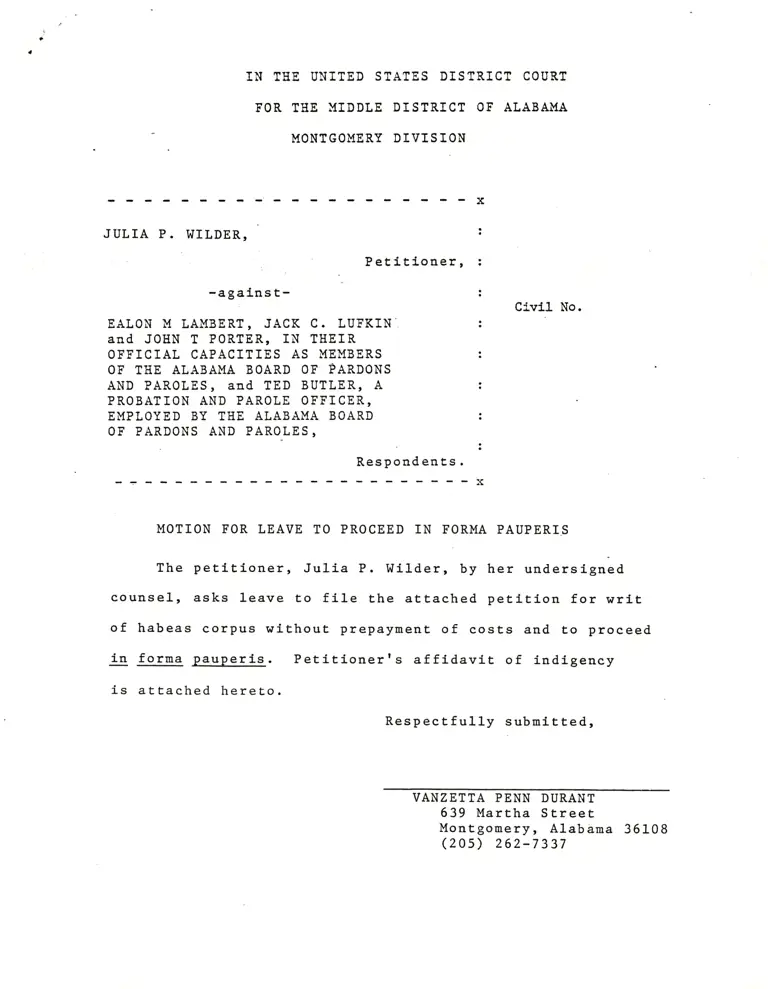

IN TEE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR TEE UIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

MONTGOMERY DIVISION

JULIA P. WILDER,

Petltlooer, :

-agalnst- :

Clvl1 No.

EALON M LAMBERT, JACK C. LUFKIN', :

aud JOEN T PORTER, IN TEELR

OFFICIAL CAPACITIES AS MEMBERS :

OF TEE ALABAMA BOARD OF PARDONS

AND PAROLES, AAd TED BUTLER, A :

PRoBATToN AND PARoLE OFFTCER,

EMPLOYED BY TEE ALABAMA BOARD :

OF PARDONS AND PAROLES,

- = - -:"-":":t-":':: :

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO PROCEED IN FORMA PAUPERIS

The petltioner, Julia P. W11der, by her underslgned

counsel, asks leave to file the attached petltion for wrlt

of habeas corpus without prepayment of costs and to proceed

ln forma pauperis. Petltionerrs affldavit of indigeney

is attached hereto.

Respectfully submitted,

VANZETTA PENN DURANT

639 Martha Street

Mootgom€ty, Alabana 36L08

(20s) 262-7337

JACK GREENBERG

LANI GUI,NIER

JA}TES S. LIEBUAN

SIEGFRIED KNOPT

10 Columbue Clrcle

Sulte 2030

New York, New York 10019

(2L2) s86-8397

Attor[eys for Petitloner

0f Couaeel:

ANTEONY G. AMSTERDAU

New York Uulverelty School of Law

40 Washlngton Square South, Room 327

New York, New York 100L2

(2L2) Sg8-2638

Dated: May , 1983

-2-