Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Virginia Cooper Re Whitfield v. Clinton

Correspondence

January 8, 1988

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Virginia Cooper Re Whitfield v. Clinton, 1988. 8780d94f-ec92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b77b5a45-ed61-4efb-ad30-69302aa0c6e3/correspondence-from-pamela-karlan-to-virginia-cooper-re-whitfield-v-clinton. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

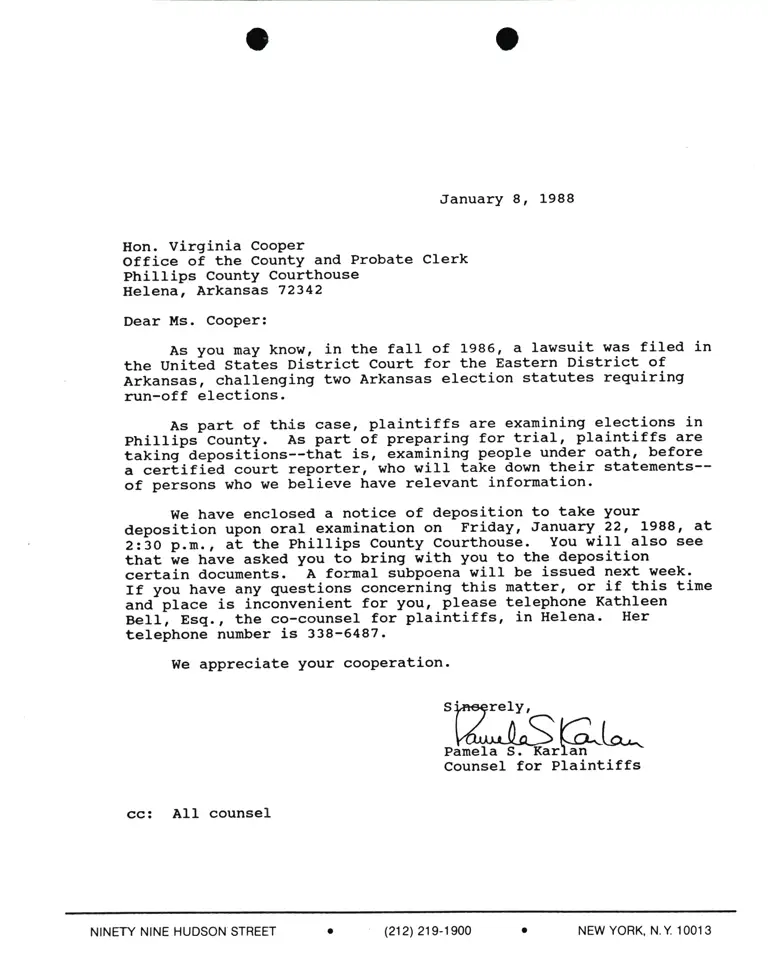

JanuarY 8, 1988

IIon. Virginia CooPer

office of the County and Probate Clerk

Phillips CountY Courthouse

He1ena, Arkansas 72342

Dear Ms. CooPer:

As you may know, in the faIl of L986, a lawsuit was fited in

the UnitlA StaLes District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas, challenging two Arkansas election statutes reguiring

run-off elections.

As part of this case, ptaintiffs are examining elections in

Phillips County. As part of preparlng for trial, plaintiffs are

taking depositions--that is, exam!ning people unfeS oath, before

a cerfifiad court reporter, who will take down their statements--

of persons who we believe have relevant infortnation.

we have enclosed a notice of deposition to take your

deposition upon oral examination on Friday, January.22, 1988, dt

ZziO p.m., aL the Phillips County Courthouse. You will also see

that we have asked you to bring with you to the deposition

certain documents. A formal subpoena wiII be issued next week.

If you have any questions concerning this matter, or if this time

and place is inconvenient for you, please telephone Kathleen

BeIl; Esq., the co-counsel for plaintiffs, in Helena. Her

telephone number is 338-5487.

We appreciate Your cooPeration.

l,/,*l^SAt^

Pamela S. Karlan

Counsel for Plaintiffs

cc: All counsel

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET (212) 219-1 900 NEW YORK, N.Y 10013