Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Jack Greenberg Re: New Voting Rights Case in Alabama

Correspondence

December 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Jack Greenberg Re: New Voting Rights Case in Alabama, 1983. 58aafad3-e492-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b7a3fbd5-4673-40f3-894a-a0034620f2d1/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-jack-greenberg-re-new-voting-rights-case-in-alabama. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Copied!

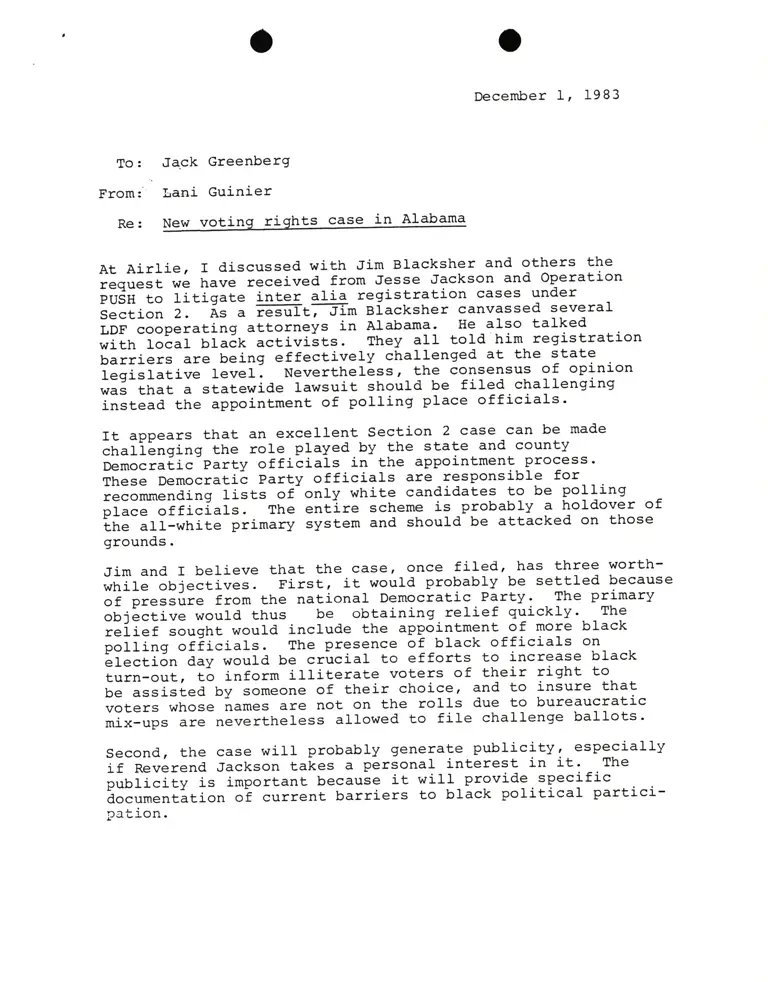

December 1, 1983

To: Ja.ck Greenberg

From: Lani Guinier

Re: New voting rights case in Alabama

At Airlie, I discussed with Jim Blacksher and others the

iequest we frave-received from Jesse Jackson and Operation

pUdi-t" litigaie inter alia registration cases under

Section 2. As a ffitlTm Biacksher canvassed several

iOf cooperating attorneys in Alabama. He also talked

with 1oca1 Ufa6f< activiits. They aII told him registration

barriers are being effectively challenged at the state

i;;i"Iative leve1. Nevertheless, the consensus of opinion

was that a statewide lawsuit should be filed challenging

instead the appointment of polling place officials.

It appears that an excellent Section 2 case can be made

.n"fil"ging the role played by the state and county

Democraiic party officials in the appointment process'

These pemocratil Party officials are responsj-b1e for

i".o**".ding ii=t= of only white candidates to be polling

ai;"" officiafs.

-

The entire scheme is probably a holdover of

the all-white prj.mary system and should be attacked on those

grounds.

Jim and I believe that the case, once filed, has three worth-

*rrir" "bjectives.

First, it would probably be settled because

of pressire from the national Democratic Party. The primary

objective would thus be obtaining relief quickly. The

r"ii.f sought would include the appointment of more black

p"if:-"g ofiicials. The presence of black officials on

Ltecti5n day would be crucial to efforts to increase black

turn-out, to inform illiterate voters of their right to

be assisted by someone of their choice, and to insure that

voters whose names are not on the rol1s due to bureaucratic

mix-ups are nevertheless allowed to file challenge ballots '

second, the case will probably generate publicity, especially

if Reverend Jackson takes a personal interest in it. The

p,-,uri.ity is import,ant because it wilI provide. specif ic

documentation of current barriers to black political partici-

pation.

Third, if the case does go to trial, the facts are good for

;;ki;; new law under seciion 2' since the case will be

filedinUontg"*"ry,w€haveagood.chanceofgettinga

fair judge. irri= i" a ground-bieaking case because it will

expand the typ"" of ele;tion 1aw procedures that can be

Iitigated under Section 2'

Jim and I anticipate that the case can be resolved prior to

Lrial for SZOOO.'If it is necessary to try the case' I

propose a budget of $15,000'

I strongly recommend that we take this case. It is backed

by blacf,s at a1l leve1s in Alabama; it is a great case

I;g;lit--""a i.i-riii h"rr" important repercussions both in

terms of the =p..iiic refiei sought as well as the precedential

value.

LG/x