Defendant's Response to Motion for Order Allowing Plaintiffs to Present Desegregation Plans at the Board's Expense

Public Court Documents

December 17, 1971

12 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Defendant's Response to Motion for Order Allowing Plaintiffs to Present Desegregation Plans at the Board's Expense, 1971. 7ae7868c-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b7ce5ddf-1250-4e2e-ad0b-01525818ed40/defendants-response-to-motion-for-order-allowing-plaintiffs-to-present-desegregation-plans-at-the-boards-expense. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

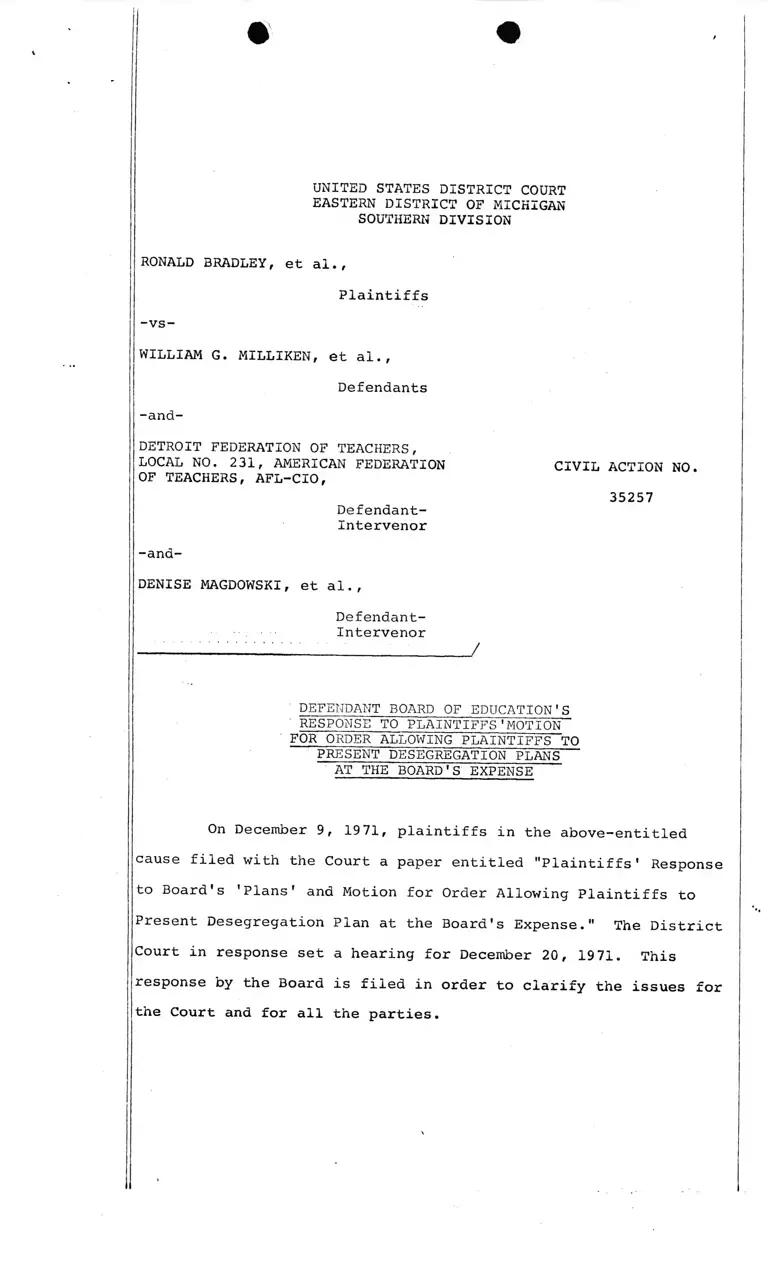

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

-vs-

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

-and-

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL NO. 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION CIVIL ACTION NOOF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

35257Defendant-

Intervenor

-and-

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendant-

Intervenor

________................................... /

DEFENDANT BOARD OF EDUCATION'S

RESPONSE TO PLAINTIFFS'MOTION

FOR ORDER ALLOWING PLAINTIFFSTO

"PRESENT DESEGREGATION PLANS

AT THE BOARD'S EXPENSE

On December 9, 1971, plaintiffs in the above-entitled

cause filed with the Court a paper entitled "Plaintiffs' Response

to Board's 'Plans' and Motion for Order Allowing Plaintiffs to

Present Desegregation Plan at the Board's Expense." The District

Court in response set a hearing for December 20, 1971. This

response by the Board is filed in order to clarify the issues for

the Court and for all the parties.

I. NOTICE

Rule IX(a) of the Rules of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Michigan provides in part:

It shall be the responsibility of the movant

to ascertain whether or not a contemplant motion

will be opposed. The motion shall affirmatively

state that the concurrence of counsel in the relief

sought has been requested on a specified date, and

that concurrence has been denied or has not been

acquiesced in and hence it is necessary to bring the motion.

The Board asks the Court to take note that plaintiffs did not

comply with Rule IX(a). Neither the Board nor, from all that

appears, any of the other defendants received any inquiry concern

ing whether plaintiffs' motion would be opposed. In fact, as will

appear later, the Board does not oppose significant portions of

the relief sought in the motion, and it would have been to the

benefit of all parties as well as of the Court if the areas of

disagreement could have been narrowed before the costly and time-

I consuming expedient of a Court hearing. It is unfortunate, in a

case like this involving the educational fate of literally hun

dreds of thousands of schoolchildren, that counsel has to learn of

a motion first from inquiring newspaper reporters, and that issues

on which the parties can agree are made to appear to the public as

; matters of spirited dispute. It is the hope of the Board that

matters of this gravity can be conducted in such a way as to mini

mize bad feeling and strident controversy in the community at

large. Plaintiffs' conduct in violating Rule IX(a) appears cal

culated to have just the opposite effect.

- 2-

II. GOOD FAITH AND THE BOARD'S RESPONSIBILITY

Plaintiffs state that they consider the plans submitted

by the Board on December 4 to have been submitted in "bad faith".

Plaintiffs' response, [hereinafter cited as PR], at 2. The

Board respectfully repeats to the Court what it stated in the

memorandum brief which was filed together with the plans, that is,

that the plans are submitted in a good faith effort to comply

with the Court's order. The Board repeats that it has attempted,

within the limited time span of sixty (60) days, to formulate

plans in accordance with the spirit indicated in the District

Court's words:

Let is be understood that I had no preconceived

notion about what the Board of Education should

do in the way of desegregating its schools nor

the outlines of a proposed metropolitan plan.

The options are completely open.

Transcript of October 4, 1971, hearing, at 27.

Reasonable men may, and do, differ over the solutions to

the problems with which we are faced. No one, to the Board's

knowledge, has provided a simple solution for desegregation of a

large central city school system located in a metropolitan area

with rapidly chaning racial population patterns. The Board

believes that the plans submitted provide a sound basis for cur

ing the ills that the District Court found existed, insofar as

they can be cured within the city limits of Detroit. The fact

that plaintiffs or the editorial writers of the Detroit Free Press

disagree with this evaluation does not change the Board's good

faith belief.

- 3-

Plaintiffs argue at some length the merits of the Board's

plans. Essentially their argument is that the plans do not pro

vide enough racial balance and, inferentially, that a plan drawn

under the auspices of plaintiffs would be so superior in this

respect that the Court would have to conclude that the Board's

plans were drawn in bad faith. But that is a judgment which can

be made only on comparison of the plans filed by the Board with

those filed by other parties. Currently, the Board's plan is the

only one before the Court.

It is the contention of the Board that the amount of

stable racial balance which can be achieved within the current

boundaries of the Detroit School District is limited by the

ineluctable facts of the racial composition of the district and

by the changing nature of that composition as found by the

District Court. (See below, The Metropolitan Context.) Plaintiffs

seemingly argue that they can do better. The only way in which

the Court can judge the accuracy of that prediction, it is sub

mitted, is to compare any plaintiffs' plan when it is submitted

with the Board's plans.

The Board therefore contends that the plaintiffs' action

here is premature. The Court is being asked to render judgment

in a vacuum. The Board, in its memorandum brief accompanying the

filing of its plans, asked the Court to hold full hearings at the

time all plans are submitted. The Board here repeats that request.

The Board submits that this is not the appropriate time for a

hearing on the merits of its plans, prior to the filing of the

State defendants' plan and those of any other party which may

wish to file plans.

- 4-

The Board wishes to make it clear that it would not object

to plaintiffs' action if plaintiffs merely were asking permission

to file a plan, although of course the Board reserves the right

to object to the plan itself, once filed, in whole or in part.

Nor does the Board object to that part of the plaintiffs' motion

which seeks cooperation from the Board and its employees and

staff in any reasonable way to the end that plaintiffs have

sufficient information and date to draw any plan they wish. In

fact, the Board during the pendency of this cause has provided

room within the School Center Building and staff cooperation to

representatives of the plaintiffs and the Board, if it had been

requested to do so prior to the filing of this motion, would have

undertaken to do the same again. The Board will continue to

offer such cooperation so long as this case is in litigation or

the Court requires.

But the prime thrust of plaintiffs' motion is not merely

that plaintiffs should be allowed to file their own plan— a propos

ition with which the Board has no quarrel. Plaintiffs also ask

that the Board of Education pay approximately $20,000 (the exact

amount is not specified) to finance the drawing of such a plan by

plaintiffs' experts.

The Board contends that such a request of the Court is

doubly premature. In the first place, it is premature to ask

the Court for a ruling on the validity of the Board's plan— which

plaintiffs' response all but demands. Secondly, it is premature

to tax costs at this stage of the case.

The Board notes parenthetically that plaintiffs do not

base their request on inability to pay, although they do mention

briefly the lack of resources of the individual plaintiffs. (They

do not mention, however, that the Detroit NAACP, one of the

- 5-

plaintiffs, has traditionally been the largest local NAACP Chapter

in the United States. Nor do they mention that plaintiffs have

been capable of financing a 41-day trial and numerous other legal

expenses.) Consequently, plaintiffs' request cannot be treated

as an in forma pauperis prayer-although even in such cases neces

sary costs are usually assessed on the Court and not on other

parties.

It is Hornbook law that the determination of costs waits

upon the outcome of the case. This is based on the common-sense

proposition that non-pauper parties (and plaintiffs do not claim

paupers' status here) should not be allowed to prolong litigation

at the expense of their adversaries.

This general principle is particularly applicable here.

To put it simply, the plans are not all in. The remedial phase

of this case, which may require substantial time of all the partiejs

and the Court, has only begun. The State defendants' plan,

required by the Court to be filed sixty (60) days after the

Detroit Board's plan, may prove fully acceptable to palintiffs—

in which case all the money and effort expended on plaintiffs'

plan will have proved a waste. Or the Court may find, for one

reason or another, the plaintiffs' plan to be wholly unacceptable-

in which case the $20,000 or so required will also have been

spent to no avail.

Furthermore, the Court, at its full hearing, may find that

defendants' Detroit School Board plan is acceptable. In addition

there is always the possibility that other parties may submit

plans and may petition the Court for the payment of fees by the

defendants Detroit School Board for plans that may be wholly

unacceptable to the Court or the plaintiffs again causing the

spenditure of funds unnecessarily to an already financially bur

dened Board of Education.

- 6-

Plaintiffs are asking for an extraordinary remedy. They

cite only one case in which it has been granted. (And even

there, if the order is read carefully, it becomes clear that the

District Court was reserving final decision on whether to impose

costs of plaintiffs' plan initially on defendants.) We further

point out that such a procedure was authorized in a system that

had a tradition of a duel system. This is not the situation here

where we do have a Board and that it is in good faith meeting the

responsibility of the Court order.

Thus, plaintiffs are asking for unusual and extraordinary

relief. They are asking the Court to make a determination as to

one of the plans filed when it is impossible to determine, by

measuring its effects against those of other plans, how relatively

well it fulfills the Court's mandate. It is the belief of the

Board that the plaintiffs' primary purpose in making this motion

is to attempt to secure a premature adverse determination on the

Board's plans before any of the parties or the Court have had the

required amounts of time and methods of comparison--including

the very existence of the other plans-necessary to make such a

determination.

The Supreme Court has recently stated, in the definitive

case in this area of the law, that the primary responsibility for

the formulation of desegregation plans lies with the local board.

Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S.1(1971), at p.12, citing Browr

Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 299, 300 (1955). And the

Court takes note of the indisputable fact that local boards are

far more aware of local particularities and have greater ability

to tailor remedies to local situations than other parties who may

not enjoy such continued acquaintance with the school district

which is the subject of the cause. Swan V. Board of Education.

402 U.S. 1 (1971).

-7

Here the plaintiffs' objections to the Board's plans

seem to show such lack of familiarity. Plaintiffs continue to

attack the magnet plan concept, belittling the number of students

involved in the program ordered into effect by the District

Court, without mentioning the crucial fact that that program was

on its own terms was a beginning pilot program. Plaintiffs, attem

to attach the "freedom of choice" label to defendants' plans with

out mentioning the crucial differences between the plans proposed

here-which employ racial balance criteria to prevent segregation—

with the freedom of choice plans forbidden in Southern schools by

the Supreme Court in cases like Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430)1968). Freedom of choice plans are not per se unconstitu

tional and these may well be instances in which they can serve as

an effective device (pp.439-41). See also, Swann v. Board of

Education 402 U.S.1(1970) at pp. 26,27.

Such hasty and misleading criticism should not be the

basis for an adjudication which would in effect determine,

before any other plans are offered, that the Board's plans are

inadequate. The Board has asked for a full hearing when all plans

are submitted, and is ready to present expert witnesses in support

of its submissions. There is no valid purpose to be served by

making determinations of this nature at this juncture, without

adequate notice of the nature of the question, on the pretext of

determining whether plaintiffs should be entitled to $20,000 of

the Board's money which they do not claim to need.

pt

- 8-

• m

III. THE METROPOLITAN CONTEXT

Plaintiffs attempt to belittle the idea that lasting

desegregation cannot occur within the Detroit School District

as currently constituted. In doing so they fly in the face of

the very District Court opinion which upheld their contentions on

the main points of this cause.

Plaintiffs note, at 9 n.6, that only 36.2% of the pupils

m the Detroit School System are white but it fails to mention

other facts cited in the District Court's opinion which are of

prime relevance in any determination of remedy. The first and

foremost of these is that the percentage of black pupils in the

Detroit Public Schools is rising rapidly— at 4.7% per year— more

rapidly than in any other large city in the nation.

Apparently plaintiffs find it inconvenient to acknowledge,

as the District Court did, that Detroit is moving rapidly toward ■

becoming an all-black school system. They argue that 36.2% is

not de minimis. The Board asks plaintiffs if 31.5% (the white per

centage for the next school year if current trends found by the

District Court continue) is de minimis? If not, what about 26.8%?

Or 19.3% (the figure found by the District Court for 1980-81 if

current trends continue)?

The point is not that the trend can be forecast with

absolute precision. No one claims that. The point is that there

is a decided and rapid trend, as the District Court found, a trend

that may accelerate or decelerate somewhat, but is highly unlikely

to cease or reverse. Some day not too far in the future a point

that even plaintiffs will have to admit is de minimis will arrive.

And plaintiffs have not yet explained how one can desegregate a

school system when all of its pupils are of the same race.

- 9-

The Board believes that the duties of the parties to this

cause cannot be properly discharged without consideration of these

facts of modern American life. A school system all of whose

pupils are black or white or oriental cannot be desegregated with

out going beyond its boundaries. We repeat the wise words of

Judge Sobeloff which plaintiffs quoted in their motion:

But school segregation is forbidden simply

because its perpetuation is a living insult

to the black children and inevitably taints

the education they receive. This is the

precise lesson of Brown.

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 426 F.2d 820, 826 (4th Cir. 1970).

greater "living insult" in Judge Sobeloff's words, than if the

Detroit school system were to contain only black pupils and the

school systems and the Detroit suburbs were to contain only white

pupils. Cf Hobson vY Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.D.C. 1967)

modified sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F. 2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969).

The Board, in preparing its plans for submission to the Court,

has attempted in good faith, within the limitations imposed by its

powers and boundaries, to respond with plans which will not lead

to such a situation. It prays that the Court will not issue a

ruling which will inferentially, on an incomplete record, deter

mine the validity of its efforts.

plaintiffs' motion which would require defendant Detroit Board

of Education to pay the costs of preparation of a plaintiffs'

plan for desegregating the Detroit Public Schools. The Board

urges the Court to reject this prayer for such an extraordinary

remedy as unwarranted and premature, for the reasons stated here

inabove.

The Board cannot imagine a more segregated system, a

IV. CONCLUSION

In summary, then, the Board opposes that portion of the

Riley and Roumell ,v

Attorneys for Defendants The

- 10-

'

Board of Education of the

School District of the City

of Detroit

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

962-8255

Dated: December 17, 1971

CERTIFICATION OF

SERVICE

STATE OF MICHIGAN )

) SS.

COUNTY OF WAYNE )

This is to certify that the copy of the foregoing has been

served upon each of the attorneys of record on the 17th day of

December, 1971 by U. S. mail, postage prepaid, addressed as fol

lows :

Louis R. Lucas, Esq.

William E. Caldwell, Esq.

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Nathaniel Jones, General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Theodore Sachs, Esq.

Rothe, Marston, Mazey, Sachs,

O'Connell, Nunn & Freid

1000 Farmer Street

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Intervening

Defendant - Detroit Federation

of Teachers

E. Winther McCroom, Esq.

3245 Woodburn

Cincinnati, OHio 45207

Alexander B. Ritchie, Esq.

Fenton, Nederlander & Dodge

2555 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

J. Harold Flannery

Paul R. Dimond

Robert Pressman

Center for Law and Education

38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

- 11-

Jack Greenberg

James N. Nabrit, III

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Bruce Miller and Lucille Watts

Attorneys for Legal Redress Committee N.A.A.C.P. Detroit Branch

2460 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Plaintiffs -

Frank J. Kelley, Esq.

Attorney General

Seven Story Office Building

Lansing, Michigan 48902

Eugene Krasicky, Esq.

Assistant Attorney General

725 Seven Story Office Building

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Gerald F. Young

Assistant Attorney General

3007 Hillcrest

Lansing, Michigan 48910

Attorneys for Defendants -

Michigan State Board of Education

In the case of Louis R. Lucas and William E. Caldwell,

the postage was sent air mail, special delivery.

Subscribed and sworn to before me

this 17th day of December, 1971

Wayne County, Michigan

My Commission Expires: 8/14/73

- 12-