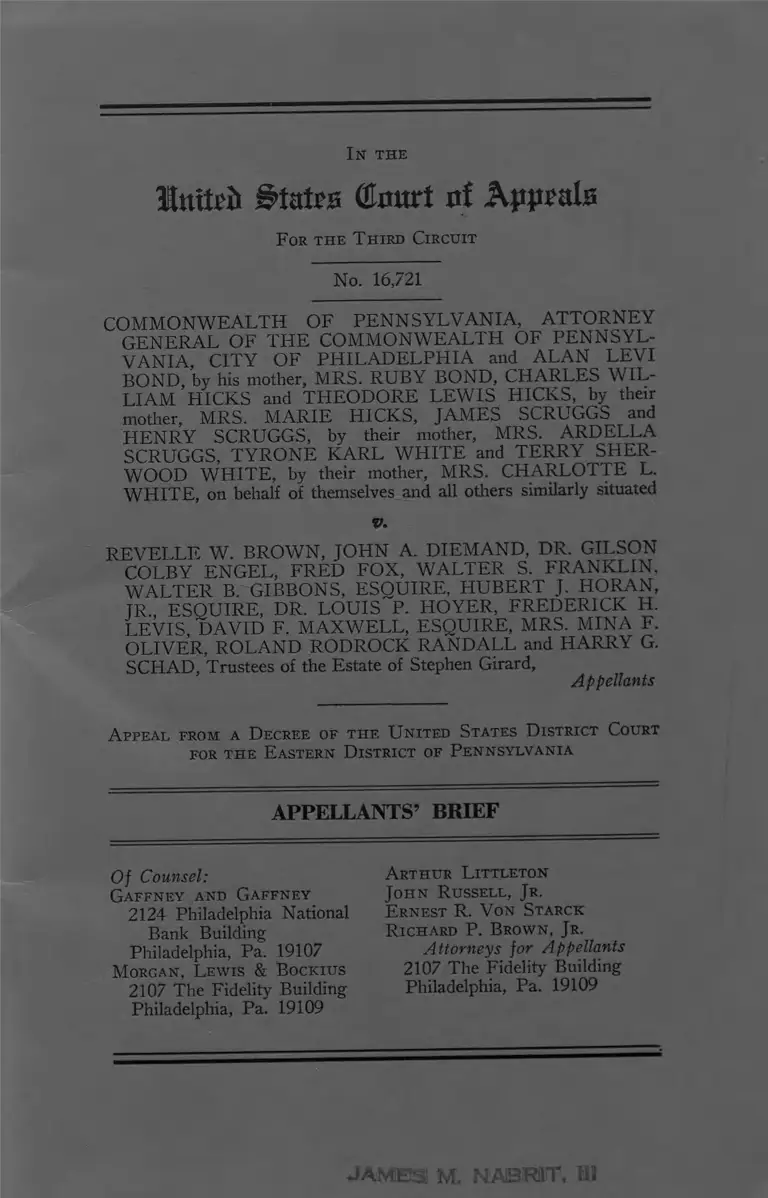

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Brown Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

August 22, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Brown Appellants' Brief, 1967. d13764f5-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b7dde3f7-2b80-473e-a3ac-448004061cac/commonwealth-of-pennsylvania-v-brown-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Ittitefr 0tat£is (tort uf Kppmh

For the T hird Circuit

No. 16,721

C O M M O N W E A L T H O F P E N N S Y L V A N IA , A T T O R N E Y

G E N E R A L O F T H E C O M M O N W E A L T H O F P E N N S Y L

V A N IA , C IT Y O F P H IL A D E L P H IA and A L A N L E V I

B O N D , by his mother, M RS. R U B Y BO N D , C H A R LE S W IL

L IA M H IC K S and T H E O D O R E L E W IS H IC K S, by their

mother, M RS. M A R IE H IC K S, JA M E S SCRUGGS and

H E N R Y SCRUGGS, by their mother, M RS. A R D E L L A

SCRUGGS, T Y R O N E K A R L W H IT E and T E R R Y SH E R

W O O D W H IT E , by their mother, M RS. C H A R L O T T E L.

W H IT E , on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated

v .

R E V E L L E W . B R O W N , JO H N A. D IE M A N D , D R. G ILSO N

C O L B Y EN G EL, FRE D F O X , W A L T E R S. F R A N K L IN ,

W A L T E R B. GIBBO N S, E SQ U IR E, H U B E R T J. H O R A N ,

TR., E SQ U IR E , DR. L O U IS P. H O Y E R , F R E D E R IC K H.

L E V IS , D A V ID F. M A X W E L L , E SQ U IR E , M RS. M IN A F.

O L IV E R , R O L A N D R O D R O C K R A N D A L L and H A R R Y G.

SCH AD , Trustees of the Estate of Stephen Girard,

Appellants

A ppeal from a Decree of the U nited States D istrict Court

for the Eastern D istrict of Pennsylvania

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

O f Counsel:

Gaffney and Gaffney

2124 Philadelphia National

Bank Building

Philadelphia, Pa. 19107

Morgan, Lewis & Bockius

2107 The Fidelity Building

Philadelphia, Pa. 19109

Arthur L ittleton

John Russell, Jr.

Ernest R. V on Starck

R ichard P. Brown, Jr.

Attorneys for Appellants

2107 The Fidelity Building

Philadelphia, Pa. 19109

J A M E S M . N A B R ilT , Ml

TABLE OF CONTENTS

S t a t e m e n t of Q u e s t io n I n v o l v e d ............................. vi

S t a t e m e n t of t h e Ca s e ...................................................... 1

A. Nature o f the P roceedings................................... 1

B. Background History o f Girard C ollege ............. 1

C. Prior Related L itiga tion ........................................ 2

D. The Present L itiga tion .......................................... 5

E. Description o f Girard College and Its Operation 7

A r g u m e n t

T h e D e f e n d a n t s H ave N ot V io lated t h e

E q u a l P r o te c tio n C l a u se of t h e F o u r t e e n t h

A m e n d m e n t b y D e n y in g A d m is s io n to I n d i

v id u a l s B eca u se of T h e ir C o l o r ........................... 9

A. No Individual Has a Right to Share Under the

Girard W ill Unless He is Included Within the

Limited Class of Beneficiaries............................... 9

B. The Plaintiffs Have Not Been Denied Any Con

stitutional Right Since the State Is Not Signifi

cantly Involved in Girard C ollege ........................ 11

C. The Lower Court’s Reliance Upon Evans v.

Newton Is M isplaced.............................................. 16

D. The Relationship Between the Orphans’ Court

and the Girard Estate Since the Appointment of

Private Trustees Does Not Constitute Signifi

cant State Involvement .......................................... 20

E. There Are No Other Relationships Between the

Girard Trust and the State Which Separately or

Together Constitute Significant State Involve

ment ........................................................................... 23

F. All o f the Insignificant and Customary Contacts

Between the State and the Girard Trust Cannot

Be Combined to Total Significant State Involve

ment ............................................................................. 26

G. Girard College Is Not “ Municipal in Nature” . . 30

PAGE

11

H. The Lower Court Correctly Held That the A p

pointment o f Private Trustees Did Not Consti

PAGE

tute State A c t io n ..................................................... 34

C o n c l u s io n ......................................................................... 40

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases :

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953) . . . 15, 34, 39

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226 (1964) .................. 40

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

( 1 9 5 4 ) ..............................................................2, 12,32,37

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294

( 1 9 5 4 ) ........................................................................... 36

Brown v. Hummell, 6 Pa. 86 ( 1 8 4 7 ) ........................ 9

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 (1961) ............................................ 13, 14, 16,17, 27

Cascade Natural Gas Corp. v. El Paso Natural Gas

Co., 386 U. S. 129 (1967) ..................................... 37

Cauffman v. Long, 82 Pa. 72 (1 8 7 6 ) ........................ 9

City of Philadelphia v. Girard’s Heirs, 45 Pa. 9

(1863) ......................................................................... 2

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ( 1 8 8 3 ) .................... 11

Commonwealth v. Brown, 373 F. 2d 771 (3d Cir.

1967) ....................................................................... 6 ,15 ,30

Commonwealth v. Brown, 260 F. Supp. 323 (E . D.

Pa. 1966) ......................................................................6,15

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ...................... 32

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corp. et al., 299 N. Y.

512, 87 N. E. 2d 541 (1949) ................................. 14

Dulles’s Estate, 218 Pa. 162, 67 Atl. 49 (1907) . . . 10

Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F. 2d 710 (4th Cir. 1964) . . . 29

Erie R. R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64 (1 9 3 8 ) . . . 39

Everson v Board of Education, 330 U. S. 1 (1946) 31

Ill

Ervine’s Appeal, 16 Pa. 256 (1 8 5 1 ) .......................... 9

Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. 296 (1966) . . 13, 14, 16, 17,

18, 19, 27, 28 ,31,32, 34,40

Ex parte Virginia 100 U. S. 339 ( 1 8 8 0 ) .................. 12

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control 347

U. S. 971 ( 1 9 5 4 ) .............................................. 37

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control 350

U. S. 413 (1956) ....................................................... 37

Girard College Trusteeship, 391 Pa. 434, 138 A .2d

844 (1958) ........................................................... 4, 10,38

Girard Estate, 4 Pa. D.&C.2d 671, 708 (Orphans’

Ct. Phila. County 1956) ..........................................3, 22

Girard Estate, 7 Pa. Fiduc. Rep. 555 (Orphans’ Ct.

Phila. County 1 9 5 7 ) ......................................... 4

Girard v. Philadelphia, 74 U. S. (7 W all.) 1 (1868) 2

Girard Will Case, 386 Pa. 548, 127 A. 2d 287

(1956) .................................................................3 ,9 ,2 1 ,3 8

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 (1965) . . . 30

Hampton v. Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th Cir.

1962) ............................................................................. 13

Harrison’s Estate, 322 Pa. 532, 185 Atl. 766 (1936) 10

Henry Estate, 413 Pa. 478, 198 A .2d 585 (1964) . . 10

Johnson Will, 370 Pa. 125, 87 A .2d 188 (1952) . . . 10

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 255 F. Supp. 115 (E .

PAGE

D. Mo. 1966) ........................................................... 40

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. 2d 212

(4th Cir. 1 9 4 5 ) ........................................................... 14

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 ( 1 9 6 3 ) ......... 13

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946) . . . . 14, 19, 34

McCabe v. Atchinson, Topeka & Sante Fe Ry., 235

U. S. 151 (1914) ....................................................... 13

McCown v. Fraser, 327 Pa. 561. 192 Atl. 674

(1937) ......................................................................... 1°

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184 (1964) . . . . 12

IV

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts,

353 U. S. 230 (1957) ................................... 3 ,9 , 12, 35

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts,

357'U. S. 570 (1958) .............................................. 5 ,10

Philadelphia v. Fox, 64 Pa. 169 (1 8 7 0 ) .................... 2

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925) 30

Public Utilities Comm’n v. Pollack, 343 U. S. 451

( 1 9 5 2 ) ........................................................................... 34

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U. S. 369 (1967) ............. 13

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) . . . 15, 34, 39, 40

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 211

F. Supp. 628 (D . C. N. C , 1962) ........................ 28

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323

F. 2d 959 (4th Cir. 1 9 6 3 ) ..................................... 14, 28

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 336 F. 2d

630 (6th Cir. 1964) ................................................ 14, 29

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ( 1 9 5 0 ) .................. 36

Sweet Briar Institute v. Button, (C . A. No. 66-C-

10-L W . D. Va., July 14, 1967) .......................... 15, 39

Sweet Briar Institute v. Button, 35 U.S.L. W k .

3419 (M ay 29, 1967) . ....... ................................... 39

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 ( 1 9 5 3 ) .................... 14

Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17

U. S. (4 Wheat.) 518 (1819) ................................. 31

United States v. Guest, 383 U. S. 745 (1966) . . . . 11

Vidal v. Girard’s Executors, 43 U. S. (2 H ow .)

127 (1844) ................................................................... 2,41

Wetzel v. Edwards, 340 Pa. 121, 16 A .2d 441

(1940) ......................................................................... 10

Wiltsach Estate, 1 D.&C. 2d 197 (Orphans’ Ct.

Phila. County 1954) ............................................ 21

Wimbish v. Pinellas County, 342 F.2d 804 (5th Cir.

1965) ...........................................................................

PAGE

13

V

C o n s t it u t io n of t h e U n it e d S t a t e s :

Fourteenth Amendment, Section I ............................. 11

S t a t u t e s :

Act o f June 30, 1869, P. L. 1276 (53 P. S.

§§ 16365-16370) ....................................................... 2

Administrative Code

Section 2302 (71 P. S. § 592) ........................ 25

Section 2303 (71 P. S. § 593) ......................... 25

Fiduciaries Act of April 18, 1949, P. L. 512, §§ 921,

981 (20 P. S. §§ 320.921, 3 2 0 .9 8 1 )........................ 21

Pennsylvania Public Accommodations Act o f 1939,

Pennsylvania Penal Code o f June 24, 1939, P . L.

872, § 654 (18 P. S. § 4654) ................................. 1, 30

Private Academic Schools Act o f June 25, 1947,

P. L. 951 (24 P. S. §§ 2731 et seq.) .................... 24

Public School Code o f 1949 (24 P. S. §§1-101

et seq.)

Section 1327 (24 P. S. § 13-1327) ................. 25

Section 1332 (24 P. S. § 13-1332) ................. 25

Section 1333 (24 P. S. § 13-1333) ................. 25

Section 1511 (24 P. S. § 15-1511) ................. 25

Section 1605 (24 P. S. § 16-1605) ................. 25

28 U. S. C. § 1331 ......................................................... 5

§ 1343 ................................................ .. • • • 5

PAGE

STATEMENT OF QUESTION INVOLVED

Did the District Court err in holding that defendants

violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment by denying individuals admission to Girard

College because o f their color?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Nature of the Proceedings.

This is an appeal by the Trustees o f the Estate of

Stephen Girard, deceased, defendants in the court below,

from a Decree (R . 870a) entered July 5, 1967 by the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsyl

vania, per the Honorable Joseph S. Lord, III, permanently

enjoining the defendants from denying admission to Girard

College to any poor male orphans who would otherwise be

qualified on the sole ground that they are not white. The

District Court based the injunction on its present conclusion

that the denial o f admission on the ground o f color is

“ unconstitutional state action” (R . 851a). In a prior appeal

to this Court, an injunction by Judge Lord entered solely

on the ground that Girard College is a place o f public accom

modation under § 654 o f the Pennsylvania Penal Code of

June 24, 1939, P. L. 872, 18 P. S. § 4654 (commonly called

the Pennsylvania Public Accommodations A ct), was

vacated for the reason that the Pennsylvania courts had

already held that the Act is not applicable to Girard College.

Commonwealth v. Brown, 373 F. 2d 771 (3d Cir. 1967).*

B. Background History of Girard College.

Stephen Girard died December 26, 1831 (R . 8a). By his

Will dated February 16, 1830 and two codicils (R . 33a-67a)

dated December 25, 1830 and June 20, 1831 he left his re

siduary estate to the City o f Philadelphia, its successors and

assigns, in trust to construct a “ college” (the codicil of

June 20, 1831 referred to it as an “ Orphan Establishment” )

for the purpose o f providing “ for such a number o f poor

male white orphan children, as can be trained in one insti

tution, a better education as well as a more comfortable

maintenance than they usually receive from the application

o f public funds.” (W ill, Clause X X ; R. 44a). He further

directed (W ill, Clause X X I ; R. 45a) that as many “ poor

white male orphans, between the ages o f six and ten years,”

as the income should be adequate to maintain, should be

*For convenience this opinion and dissenting opinion have been

reproduced in the Appendix, starting at p. 524a.

2

admitted to the institution, preference being given first to

orphans born in Philadelphia; secondly, to those born else

where in Pennsylvania; thirdly, to those born in New York

City, and lastly, to those born in New Orleans (R . 53a).

The institution opened in 1848 (R . 10a). Later, pur

suant to the Act o f June 30, 1869, P. L. 1276, 53 P. S.

§§16365-16370, the administration o f the college was trans

ferred, together with that o f other charitable trusts for

which the City was Trustee, from the City to a Board of

Directors o f City Trusts created by the Commonwealth.

Although Girard’s will was subjected to other unsuccess

ful attacks,1 his testamentary direction restricting admis

sion to Girard College to poor white male orphans was fol

lowed without challenge for more than a hundred years.

However, in 1954, not long after the decision o f the Su

preme Court o f the United States in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), proceedings were com

menced in the Orphans’ Court o f Philadelphia County to

attack the validity o f the exclusion o f nonwhite male orphans

from admission to the institution. Because o f the close rela

tion between those proceedings and the present litigation

a review o f the earlier proceedings is essential to an under

standing o f this case.

C. Prior Related Litigation.

On September 30, 1954 six Negro boys whose applica

tions had been rejected because the applicants were not

white, filed a Petition for Citation in the Orphans’ Court of

Philadelphia County2 to the Board of Directors o f City

Trusts to show cause why they should not be admitted to

Girard College without discrimination as to race or color.

They were subsequently joined by the City and the Com

1Cases involving the W ill of Stephen Girard include Vidal v.

Girard’s Executors, 43 U. S. (2 H ow .) 127 (1 8 4 4 ) ; Girard v. Phil

adelphia, 74 U. S. (7 W all.) 1 (1 8 6 8 ); City of Philadelphia v.

Girard’s Heirs, 45 Pa. 9 (1 8 6 3 ); Philadelphia v. Fox, 64 Pa. 169

(1870).

2Estate of Stephen Girard, docketed at No. 10, July Term, 1885.

3

monwealth. A fter answer and trial, all the petitions were

dismissed, Girard Estate, 4 Pa. D. & C. 2d 671 (1955),

and exceptions were later dismissed by the Orphans’ Court

en banc on January 6, 1956. 4 Pa. D. & C. 2d 708.

On appeal to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court the

Decree of the Orphans’ Court was affirmed. Girard Will

Case, 386 Pa. 548, 127 A. 2d 287 (1956). The Pennsyl

vania Supreme Cort held that in acting as a Trustee under

Girard’s Will the City was not exercising a governmental

function, but merely acting as a fiduciary, and therefore the

denial o f admission to the applicants on the ground of their

color was not prohibited “ state action” under the Four

teenth Amendment. The court also stated that if it should

be held that the City, because of an inhibition imposed upon

it by the Fourteenth Amendment, could not carry out

Girard’s requirement that the poor male orphans be white,

then the proper remedy would be for the Orphans’ Court

to appoint another Trustee who could do so, since Girard’s

dominant purpose was the creation of an orphan establish

ment for poor male white orphans. 386 Pa. at 566, 127

A. 2d at 295.

The Commonwealth, the City and the applicants ap

pealed to the United States Supreme Court. That Court,

without oral argument, dismissed the appeal for want of

jurisdiction, but treating the appeal papers as a petition for

writ o f certiorari, reversed on the ground that the Board

o f Directors o f City Trusts was an agency o f the Common

wealth and that, even though the Board was acting as a

Trustee, its refusal to admit the applicants because they

were Negroes was discrimination by the State and there

fore forbidden by the Fourteenth Amendment. It re

manded the cause to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court for

further proceedings not inconsistent with the Opinion.

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts, 353

U. S. 230 (1957). Pursuant to that mandate, the Pennsyl

vania Supreme Court vacated the decrees o f the Orphans’

Court and remanded the cause to that Court for further

4

proceedings not inconsistent with the Opinion of the United

States Supreme Court as set forth in its said mandate.”

7 Pa. Fiduc. Rep. 554 (Sup. Ct. 1957).

The Orphans’ Court thereupon entered a decree “ in

obedience to the mandate o f the United States Supreme

Court . . . and the order o f the Supreme Court o f Penn

sylvania” , first, dismissing the petitions for admission and

removing the Board as Trustee o f the Girard Estate,

Girard Estate, 7 Pa. Fiduc. Rep. 555, 558-59 (1957), and,

second, substituting thirteen private citizens as Trustees,

7 Pa. Fiduc. Rep. 606 (1957).

Again there was an appeal to the Pennsylvania Su

preme Court, which affirmed on the ground that the Or

phans’ Court, had properly construed the mandate o f the

United States Supreme Court. Girard College Trusteeship,

391 Pa. 434, 138 A . 2d 844 (1958). It was there held

that the constitutional inability o f the Board to apply the

testator’s criterion o f color affected the Trustee and not

the Trust. The court further found that since the United

States Supreme Court had not held that there was any

constitutional barrier to the removal o f the Board as

Trustee, it was the duty o f the Orphans’ Court to proceed

as it had, in order that the orphan establishment could be

administered in accordance with Girard’s specific directions.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court expressly rejected the

argument that, aside from the participation o f the Board

o f Directors o f City Trusts, the establishment had taken on

such a “ public character” that it must be administered in

accordance with the restrictions o f the Fourteenth Amend

ment (391 Pa. at 443, 445-447, 138 A. 2d at 848-849). The

court also held that the action o f the Orphans’ Court in

substituting Trustees capable of administering the orphan

age in accordance with Girard’s directions did not con

stitute “ state action” which denied the applicants equal pro

tection o f the law, since the applicants who did not come

within the designated beneficiary class had no constitution

5

ally guaranteed right to share in this private charity’s bene

fits. 391 Pa. at 334-456, 138 A.2d at 851-854.

The Commonwealth, the City and the applicants once

more appealed to the United States Supreme Court. That

Court, again without oral argument, dismissed the appeal

and, treating the appeal as a petition for certiorari, denied

certiorari without opinion. Pennsylvania v. Board of Di

rectors of City Trusts, 357 U. S. 570, rehearing denied,

358 U. S. 858 (1958).

D. The Present Litigation.

On December 16, 1965, the Commonwealth o f Penn

sylvania, its Attorney General, the City of Philadelphia,

and seven poor male orphans between the ages o f six and ten

whose applications for admission to Girard College had

been rejected because they are not white, filed this Complaint

to enjoin the defendants from further refusing to admit

the minor plaintiffs and other applicants to Girard College

solely because o f their race. The minor plaintiffs sued on

behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated

(R . 6a). The jurisdiction of the District Court was as

serted under 28 U. S. C. §§1331 and 1343(3), and 42

U. S. C. §§ 1981 and 1983 (R . 4a).

The Complaint contains three counts, which may be

summarized as follows:

I. The first count is based on the theory that the

denial o f admission to the minor plaintiffs because they

are not white, and therefore not within the designated

beneficiary class, is a violation o f their constitutional

right to equal protection of the laws (R . 11a).

II. The second count asks for the application o f the

doctrine o f cy pres on the theory that Stephen Girard’s

dominant purpose in establishing the orphan establish

ment was to benefit the City o f Philadelphia, that the

City now has a great need for facilities for the educa

tion and training o f Negro children, and that Girard’s

6

basic purpose can only be achieved by the admission of

Negro applicants (R . 22a).

III. The third count is based on the theory that

exclusion from the orphan establishment on the basis

o f race is contrary to the Pennsylvania Public Accom

modations Act, supra, and the public policy o f the

United States and the Commonwealth o f Pennsylvania

(R . 27a).

On January 4, 1966 defendants filed a motion to dis

miss the Complaint on the grounds that (1 ) the District

Court lacked jurisdiction over the subject mater, (2 ) the

issues were res judicata by reason o f the prior related pro

ceedings, (3 ) the Complaint failed to state a claim upon

which relief could be granted, and (4 ) the Commonwealth,

the Attorney General and the City o f Philadelphia lacked

the requisite standing or capacity to bring the action (R .

126a).

On September 2, 1966 the District Court filed its

Opinion and Order (R . 132a) (a ) denying the motion as

to Counts I and II, but without prejudice to the defendants’

rights to renew the motion at the appropriate time; (b )

granting the motion as to Count III on the ground o f res

judicata insofar as the Commonwealth o f Pennsylvania,

the Attorney General o f Pennsylvania and the City of

Philadelphia are parties-plaintiff; and (c ) denying the mo

tion as to Count III insofar as the seven minors are parties-

plaintiff. Commonwealth v. Brown, 260 F. Supp. 323 (E . D.

Pa. 1966) (R . 132a et seq.). In his Opinion of September

2, 1966, Judge Lord held, inter alia, that the Pennsylvania

Public Accommodations Act applied to Girard College as

suming the truth o f the averments in the Complaint.

On September 21, 1966 defendants filed their answer

(R . 197a) to the Complaint, denying all o f the principal

allegations but acknowledging that the minor plaintiffs had

been refused admission to Girard College solely on the

ground that they are not white (R . 197a-221a).

7

After filing the Answer to the Complaint, and on plain

tiffs’ insistence, hearings were held on Count III only. On

November 2, 1966 Judge Lord entered an opinion and final

injunction under that Count. On February 28, 1967, how

ever, this Court vacated that order on the ground that the

Pennsylvania Courts had already held that the Pennsylvania

Public Accommodations Act does not apply to Girard Col

lege and remanded the case to the District Court (R . 524a).

Commonwealth v. Brown, 373 F. 2d 771 (3d Cir. 1967).

The District Court then held hearings on Count I in

April, 1967, and on July 5, 1967 it ordered that the action

be maintained as one for a class consisting of “ all poor male

orphans who would be eligible for admission to Girard Col

lege except for the fact they are not ‘white’ ” and perma

nently enjoined the defendants from denying admission to

any members o f that class on the ground they are not white

provided they are otherwise qualified for admission (R .

870a). It is from this order that the appeal is taken.

E. Description of Girard College and Its Operation.

Girard College is located in North Central Philadelphia

on a tract of ground approximately 43 acres in extent, which

at the time o f Girard’s death was a farm outside the then

city limits. There are about 25 buildings on the campus and

the whole is surrounded by a stone wall 10 feet in height,

as prescribed in the Will of Stephen Girard. There are only

two gates in this wall, one being a service gate for deliveries

only and the other being a main gate at which a watchman

is constantly stationed. The public is not permitted in and

the children are not permitted out except by special per

mission (R . 479a; Ex. D1 an aerial photograph).

No orphan boy is admitted into the institution until

after the mother or guardian has made a formal written

application and the boy has been examined by the resident

doctor, the institution’s psychologist, and tested for both

intelligence and achievement. The mother, if any, is also

interviewed by the institution’s field representatives, or

8

social workers. The Admissions Committee makes its rec

ommendation as to each applicant to the President of the

College who in turn makes his recommendation to the Trus

tees. Only the Trustees can approve final admission. From

25% to 30% of the applicants are rejected for psychologi

cal, intellectual or educational reasons (R . 479a).

Upon introduction into the institution the mother or

guardian o f the orphan executes a document under which

the legal custody and control o f the orphan is transferred

to the Trustees so long as the orphan remains in attendance

at the institution. Ordinarily the boys go to their homes for

holidays, but if the boy’s home has not been approved by

the institution, he remains there continuously (R . 480a).

The institution provides elementary school and second

ary school teaching on the premises (R . 246a). Admissions

are accepted throughout the year up to March 31st (R .

254a).

The number of children attending the College is con

trolled by the amount o f income available from Girard’s

residuary estate, as Girard directed (R . 52a, 55a). It now

costs about $3,000 per year to maintain and educate each

child (R . 318a), so that the present enrollment is about 720

(R . 404a), whereas in 1933 when costs were much less the

enrollment was as high at 1739 (E x. P -38).

The College is supported entirely by the income from the

trust. It has never received funds from any governmental

unit.

The thirteen Trustees are divided into appropriate com

mittees which meet monthly, and the Trustees as a whole

also meet monthly. Their duties have been described as

being more onerous than those of a corporate director

(R . 673a). No governmental official, city, state or federal,

participates with the trustees, or even advises the trustees,

in the administrations o f the trust (R . 761-762, 794).

9

ARGUMENT

THE DEFENDANTS HAVE NOT VIOLATED THE EQUAL

PROTECTION CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH AMEND

MENT BY DENYING ADMISSION TO INDIVIDUALS BE

CAUSE OF THEIR COLOR.

A. No Individual Has a Right to Share Under the

Girard W ill Unless He Is Included Within the

Limited Class of Beneficiaries.

In Pennsylvania a testator has the right to dispose of

his property as he see fit, including the right to select the

beneficiaries of his charity in accordance with his own

personal desires. Moreover, a testator’s right to dispose of

his estate as he sees fit “ is a property right entitled to the

full protection o f our laws.” Harrison’s Estate, 322 Pa. 532,

534, 185 Atl. 766, 767 (1936) (refusing to terminate a

spendthrift trust with charitable remainder).

Speaking for the Court in Girard Will Case, 386 Pa.

548, 556, 127 A .2d 287, 290 (1956), rev? d and remanded on

other grounds sub nom. Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors

of City Trusts, 353 U. S. 230 (1957), Chief Justice Stern

stated:

“ Subject, o f course, to compliance with all ap

plicable laws, it is one o f our most fundamental legal

principles that an individual has the right to dispose

of his own property by gift or will as he sees fit;

indeed this right is so much protected that a testa

tor’s directions may be enforced though contrary to

the general views o f society, (see, for example,

Higbee Will, 365 Pa. 381, 75 A. 2d 599), and how

ever arbitrary, unwise, intolerant discriminatory, or

ignoble his exercise of that right may be. He is en

titled to his idiosyncracies and even to his preju

dices.”

T o the same effect are the following cases cited and

quoted by Chief Justice Stern in Girard Will Case, supra:

Brown v. Hummed, 6 Pa. 86 (1 8 47 ); Ervine’s Appeal,

16 Pa. 256 (1 8 51 ); Cauffman v. Long, 82 Pa. 72 (1876) ;

1 0

Dulles’s Estate, 218 Pa. 162, 67 Atl. 49 (1907 ); McCown

v. Fraser, 327 Pa. 561, 192 Atl. 674 (1 9 37 ); Wetzel v.

Edwards, 340 Pa. 121, 16 A. 2d 441 (1940) ; Johnson Will,

370 Pa. 125, 87 A . 2d 188 (1 9 52 ); Henry Estate, 413 Pa.

478, 483, 198 A. 2d 585 (1964). See also Girard College

Trusteeship, 391 Pa. 434, 138 A . 2d 844, appeal dismissed

and cert, denied sub nom., Pennsylvania v. Board of Di

rectors of City Trusts, 357 U. S. 570 (1958).

Pursuant to the foregoing right to dispose of his prop

erty and select the objects of his charitable bounty as he

saw fit, Stephen Girard expressly provided in his W ill that

the persons to be admitted to the orphan establishment

should be “ poor white male orphans” between the ages

o f six and ten years. Will, Clause X X I (3 ) (R . 52a). This

followed an earlier declaration in the Will that he was

“ particularly desirous to provide for such a number o f

poor male white orphan children, as can be trained in one

institution, a better education as well as a more comfortable

maintenance than they usually receive from the application

of public funds.” Will, Clause X X (R . 44a).

Stephen Girard did not exclude anyone from the Col

lege. Pie merely did not include everyone. Thus, he did

not see fit to designate as a beneficiary of his great charity

anyone over the age of ten years, any female, anyone who

is not poor, anyone who is not white, or anyone with a

living father no matter how poor.

No one who for any reason is outside the large, but

nonetheless limited, class of beneficiaries has any right to

attend Girard College. As Chief Justice Jones stated in

Girard College Trusteeship, supra, 391 Pa. at 455, 138

A. 2d at 853: “ What keeps such a charity, so created and

restricted, from constituting a violation o f the ‘equal pro

tection’ clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment is that no one

who does not come within the settlor’s definition o f benefi

ciary has a constitutionally protected right (or any right

for that matter) to share in the charity’s benefits.”

11

B. The Plaintiffs Have Not Been Denied Any Consti

tutional Right Since the State Is Not Significantly

Involved In Girard College.

In an effort to cure the patent defect in their claim that

nonwhite male orphans have a right to be admitted to Girard

College, plaintiffs’ counsel have striven to make it appear

that “ state action” , not the testator or his Will, is presently

responsible for the denial o f their admission.

The lower court has rejected many of the arguments

advanced in support o f this contention, but, on the basis of

its own concept o f state involvement, has concluded that

“ racial exclusion at Girard College is so afflicted with State

action, in its widened concept, that it cannot constitutionally

endure.” (R . 869a). In so doing it has extended the state

action concept beyond any point heretofore judicially

reached and, indeed, beyond the realm of logical reality.

To appreciate the extreme nature o f the lower court’s

decision it is necessary to consider the presently existing

judicial perimeters o f the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

That clause provides, “ Nor shall any State . . . deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of

the laws.” Read literally, it prohibits only discrimination by

States, not individuals. This was early decided in the Civil

Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 11 (1883) where Mr. Justice

Bradley, speaking for the majority, said “ It is State action

o f a particular character that is prohibited. Individual in

vasion o f individual rights is not the subject-matter o f the

amendment.” This distinction was recently affirmed in

United States v. Guest, 383 U. S. 745 (1966) where it was

said (p. 755) :

“ The Equal Protection Clause ‘does not . . . add

any thing to the rights which one citizen has under

the Constitution against another.’ United States

v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542, 554-555. As Mr.

Justice Douglas more recently put it, ‘The Four

teenth Amendment protects the individual against

1 2

state action, not against wrongs done by individuals.’

United States v. Williams, 341 U. S. 70, 92 (dis

senting opinion). This has been the view o f the

Court from the beginning. United States v. Cruik-

shank, supra; United States v. Harris, 106 U. S.

629; Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3; Hodges v.

United States, 203 U. S. 1; United States v. Powell,

212 U. S. 564. It remains the Court’s view today.

See, e.g., Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. 296; United

States v. Price, post, p. 787.”

It is perfectly clear that neither the state nor any agency

o f the state, such as a municipality, may directly or actively

discriminate along racial lines. For example, a state mis

cegenation law is unconstitutional, McLaughlin v. Florida,

379 U. S. 184 (1964), segregation in public schools is

unlawful, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

(1954) ; and even in 1880 it was held that a state judge

who excludes Negroes from jury service does so unconsti

tutionally, E x parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1880). The

first Girard case, Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of

City Trusts, supra, is merely another illustration of direct

municipal participation in discrimination— the only new ele

ment in the case being that the prohibition applies even when

the state agency is not acting in its governmental capacity

but solely as a trustee.

These are the obvious cases of state action. However,

where the discrimination on its face appears to be private,

the so-called “ nonobvious” cases, the perimeters become

indistinct; and, while it is possible to create categories of

decisions, it is fruitless to attempt, as has the lower court,

to distill out of one or all of the many decisions a single

basic rule which, when applied to a new factual situation,

will provide the correct answer. The Supreme Court, speak

ing through Mr. Justice Clark, has denied that such a rule

can or should be formulated by saying “ . . . to fashion and

apply a precise formula for recognition of state responsi

bility under the Equal Protection Clause is an ‘impossible

13

task’ which ‘this Court has never attempted.’ ” Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715 (1961).

However, the opinions do disclose that certain specific

types of governmental involvement will be held to convert

otherwise private decisions into “ state action” .3 All o f the

major cases in this field may be placed in one or more of

the following categories:

1. Cases in which the private discrimination has

been encouraged or compelled by the state. See McCabe

v. Atchinson, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry, 235 U. S. 151

(1914) (a state law permitted railroads to supply sleep

ing cars for white passengers o n ly ); Lombard v.

Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 (1963) (statements by city

officials interpreted to mean that the city would not

permit Negroes to seek desegregated service in restau

rants) ; the concurring opinion of Mr. Justice White

in Evans v. Newton, 383 U. S. 296 (1966) (a chari

table gift of a public park for whites only was possible

solely because of enabling state legislation), and Reit-

man v. Mulkey, 387 U. S. 369 (1967) (adoption of a

constitutional amendment permitting private discrimina

tion in housing which was said to encourage such dis

crimination).

2. Cases in which the place of discrimination, such

as a golf course, has been owned and operated as a

public facility by a governmental unit and either sold

or leased to private parties under agreements in which

the governmental unit retained control over usage. See

Hampton v. Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th Cir. 1962) ;

Wimbish v. Pinellas County, 342 F. 2d 804 (5th Cir.

1965).

3In this field of law distinctions between the facts in cases are of

the greatest importance. Mr. Justice Clark emphasized this in Burton

by saying (365 U. S. at 726) : “ Owing to the very largeness of gov

ernment, a multitude of relationship might appear to some to fall

within the Amendment’s embrace, but that, it must be remembered,

can be determined only in the framework of the peculiar facts or cir

cumstances present.”

14

3. Cases in which the institution involved has re

ceived and is receiving financial support from govern

mental sources. See Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial

Hospital, 323 F. 2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963), cert, denied,

376 U. S. 938 (1964) (a private hospital receiving

massive federal aid under the Hill Burton program );

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. 2d 212 (4th

Cir. 1945), cert, denied, 326 U. S. 721 (1945) (a free

library supported almost wholly by municipal fu n d s);

Evans v. Newton, supra, (a park which was “ swept,

manicured, watered, patrolled and maintained by the

city as a public facility” ).

4. Cases in which a private body is operating what

is normally a public place or exercising what is normally

a public function. See Marsh v. Albama, 326 U. S. 501

(1946) (a “ company-owned” town similar in all extern

al respects to any ordinary town) ; Terry v. Adams, 345

U. S. 461 (1953) (a county political organization which

conducted its own prim ary); and Evans v. Newton,

supra (a public park in the center of a city).

5. Cases in which the governmental unit is involved

in the establishment through having planned it, financed

it, retained some control over it, or is profiting from it.

See Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra,

(restaurant in a publicly owned parking garage) and

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 336 F. 2d 630

(6th Cir. 1964) (a motel in a redevelopment complex

planned and created by a Housing Authority).4

6. Cases in which a state agency has compelled or

or has threatened to compel discrimination by an un

willing individual. See Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1

4Compare Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corp. et al., 299 N. Y .

512, 87 N. E. 2d 541, cert, denied, 339 U. S. 981 (1949) in

which the court refused to order integration of a huge housing pro

ject which had been built with private funds by a private developer

but on land acquired by eminent domain and which was partially tax

exempt.

15

(1948) and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953)

(judicial enforcement of restrictive racial covenants

against persons who were willing to sell to N egroes);

and Sweet Briar Institute v. Button (C . A . No.

66-C-10-L, W. D. Va., July 14, 1967) , threatened en

forcement by an Attorney General o f a testamentary

provision limiting attendance at a college to white

women despite willingness o f the Trustees to ignore

this limitation in order to obtain federal grants).

It is readily apparent that the present case does not fall

factually within any o f these classes. There was no legis

lation which compelled or even encouraged Girard not to

include nonwhite children in his g ift; the College was con

ceived and planned solely by Girard; the land on which the

College is built was never owned by the State and was

acquired privately by Girard in his lifetime; the funds

which have been used to build and operate the College have

been only those derived from the estate left by Girard;

there is no contingency in Girard’s Will under which the

State or City could become the owner o f the College; the

College is not licensed by the State; and there is no element

o f state compulsion since the defendant trustees are volun

tarily and conscientiously admitting into Girard College

only the specific class which Girard intended to benefit.

Finally, it has never been held that the providing of an

education to children at private expense is the performance

o f such a public function that it is “ state action.”

The lower court said in its opinion denying the motion

to dismiss the Complaint that the constitutional questions

presented “ are on the frontier o f the Fourteenth Amend

ment.” 5 This has proven to be an understatement. Only

by exploring beyond the existing frontier was it possible

for the lower court to hold Girard’s color limitation in his

gift to be unconstitutional.

5Commonwealth v. Brown, 260 F. Supp. 323, 332 (E . D. Pa.

1966).

16

C. The Lower Court’ s Reliance Upon Evans v. Newton

Is Misplaced.

No one should disagree with the lower court’s state

ment that the specific question involved in this case is

whether, following the removal o f the City as trustee, “ the

College could have been and in fact was subsequently dis

associated from the organs o f state control, direction, and

supervision. . . (R . 854a). Evans v. Newton makes such

a question peculiarly pertinent since it was held there that

the appointment o f private trustees in substitution o f the

City did not “ ipso facto” dissipate the momentum the park

had acquired as a public facility, and that “ if the munici

pality remains entwined in the management or control o f

the park it remains subject to the restraints o f the Four

teenth Amendment.” It was concluded that “ the mere sub

stitution o f trustees” did not instantly transfer the park

from the public to the private sector.

In attempting to answer this inquiry, however, the

lower court “ distilled” from Evans a certain “ underlying

principle” , despite Mr. Justice Clark’s warning in Burton

that the Supreme Court neither has nor wishes to have any

yardstick o f universal application. Even more strangely,

there seems to be absolutely no basis, either in the facts of

Evans or in the reasons advanced in the majority opinion,

for this particular distillation. The principle o f universal

application discerned by the lower court was stated as fol

lows (R . 859a) :

“ The purpose of that inquiry is to ascertain

whether the institution (here Girard College) is

presently associated with the State in a manner

which tends to suggest to the community that the

institution’s policy o f racial discrimination is either

practiced by or approved by public authority. This,

we think, is the essence o f Evans v. Newton.” (E m

phasis supplied.)

There is nothing in Evans, or in any other case decided

by the Supreme Court, which would lead one to believe that

cases involving the Equal Protection Clause are decided on

17

the basis o f appearance rather than substance. In Evans

the park was a park actually maintained by the municipality

and in fact open to all members o f the public. In Burton,

the other case relied upon by the lower court to buttress its

conclusion, the only part o f the entire public garage com

plex owned by the Parking Authority which was not open

to Negroes was the restaurant; the lease rentals the Author

ity received from the restaurant were essential to the financ

ing o f the public parking facilities; and the discriminatory

policy o f the restaurant which added to its revenues made

these rentals possible. State involvement was factual, not

merely such as to “ suggest to the community” that the

racial discrimination was approved by public authority.

Indeed, the concept o f community viewpoint does not

appear in either opinion.

However, it would be to the advantage of the defend

ants to adopt this test which the lower court has read into

Evans. Since the removal of the City as Trustee (the

critical time adopted by the lower court) the public could

not possibly have been misled into believing that Girard’s

wishes with respect to color were “ either practiced by or

approved by public authority” . It was well publicized that

the City and the State actively sought to break Girard’s

W ill in the prior litigation and that it was as a result o f

that litigation that private trustees were appointed. It has

been a matter o f the widest public knowledge that since

that time the City and the Governor have endeavored to

persuade the private trustees to ignore Girard’s directions,

and o f course, it is a matter of record that the Common

wealth and the City instituted the present litigation.

Moreover, the very appearance o f the College, con

sisting as it does o f handsome buildings and large playing

field completely surrounded by a high stone wall, would

never suggest to the community that the institution is

public. Indeed, it is a matter of national knowledge that

Girard College is one o f the oldest and finest private

charities of its kind.

18

Thus, by the very test posited by the lower court, the

policy o f Girard College as expressed in the W ill o f Stephen

Girard is not subject to the prohibition o f the Fourteenth

Amendment. But this is not really the test, as the lower

court impliedly admits, since it never pursues the inquiry

to its obvious answer.

Although the only fact in common between Evans and

the present case is that in each private trustees had been

substituted for a municipality because a municipality could

not constitutionally carry out the testator’s intent to benefit

only members o f the white race, the lower court nonetheless

said that the Evans decision is controlling in this case

(R . 852a). The factual differences are much greater than

the one point o f similarity.

In Evans the majority based its decision on two grounds.

The first was that the City had for years maintained the

park as a part o f its public park system— “ it was swept,

manicured, watered, patrolled and maintained by the city

as a public facility for whites only” — and the court would

not assume that the mere appointment o f new trustees would

change that situation. As the court said: “ The momentum

it acquired as a public facility is certainly not dissipated

ipso facto by the appointment o f ‘private’ trustees. So far

as this record shows, there has been no change in municipal

maintenance and concern over this facility” . 382 U. S. at

301.6

The record in this case is totally different. Girard Col

lege was never maintained as a part o f the public school

system. No city funds have ever been used to operate

Girard College. There can be no doubt that Girard College

is divorced from its former city relationship. No State or

City officer or appointee has participated in the operation

6It is inherent in the Evans opinion that a long history of state

participation through municipal trustees, and even through municipal

maintenance, does not constitute present state involvement. If this

were not so, there would have been no need for the Court to have

considered the nature of the park and the future role of the city.

19

o f the College since the removal o f the City as trustee almost

ten years ago (R . 761a-762a, 794a, 783a). Not a penny

o f City or State money has been used for its support (R .

847a, 869a). None o f its property is now or ever was owned

by the City or State. No State or City legislation fosters,

protects or directs it. As a private school and as an orphan

age its relationships with the City and State are only those

applicable to every unlicensed private or parochial school

and all other charitable child care agencies. The separation

was and is complete.

The second ground for decision, which Justice Harlan

in his dissent says “ ultimately emerges as the real holding”

is that a park such as Baconsfield is in the “ public sector”

or “public domain” and, like the company town in Marsh

v. Alabama, 326 U. S. SOI (1946), must be operated under

constitutional restrictions. The court was careful to say that

it was not equating private schools with parks; and it is

obvious that the court would never liken Girard College to

Baconsfield Park. The United States Brief in Evans shows

that the park is approximately 100 acres in extent, that it

is located in the center of Macon, that it is open on all

sides, that public streets and one major highway pass

through it, and that it may be visited freely by all members

of the public except Negroes.7 With that one exception,

it is to all intents and purposes an ordinary public park

maintained by the municipality just as all its other public

grounds. Girard College, on the other hand, is surrounded

by a high stone wall, only about two-thirds of the applicants

are approved for admission; members of the public are not

even permitted on the campus without special permission,

and, in short, it is totally dissimilar to a public school or

any other public facility. Girard directed that it should be

private and it not only is, but it looks it.

7 Similarly in Marsh the company town was described as a “ sub

urb” of Mobile, Alabama, consisting “ of residential building, streets,

a system of sewers, a sewage disposal plant and a ‘business block’ on

which business places are situated.” 362 U. S. at 502.

2 0

There is no reason to believe that the Supreme Court

would see any similarity between an open city park avail

able to all except Negroes and Girard College, the gates of

which have been closed to the public from its very inception.

D. The Relationship Between The Orphans’ Court and

The Girard Estate Since The Appointment of Private

Trustees Does Not Constitute Significant State Invol

vement.

While the lower court held that the substitution of pri

vate trustees for the city agency did not involve constitu

tional implications (see infra, pp. 35-41) and that “ some

thing more” is required, it found that additional something

in the suggestion o f “ a very special interest” , or “ the im

plied approval” , or “ the appearance o f continuing interest”

of the Orphans’ Court “ in a trust which is, on its face, dis

tinguishable from most other trusts only in its racial exclu

sivity” . (R . 862a). This finding is immediately followed by

a disavowal of any suggestion that the Orphans’ Court “has

consciously and purposefully promoted or sponsored the

discriminatory design at Girard College” ; but this dis

avowal, if given full credit, negates the legal effect of the

finding, since if there has been no such purpose, there would

seem to be no logical basis for holding that there is uncon

stitutional state action. If mere involvement with a govern

mental unit, without governmental purpose, property or

profit, is sufficient to constitute “ state action” , the asserted

right o f individual choice becomes a hollow pretense.

Moreover, the actions o f the Orphans’ Court which are

said to create the appearance of “ implied approval of de

fendants’ discriminatory conduct” do not do so. There is

nothing unusual in the conduct of the Orphans’ Court to

one who understands the practice of that court and the

extraordinary responsibilities imposed upon the trustees.

The lower court thinks that because the private trustees

are required to file an account with the Orphans’ Court

2 1

every three years and may be removed “ at will” , that court

has shown an abnormal interest in the trust which can be

explained only by reason of the fact that Girard limited

his gift to white beneficiaries.8 This is not so. The City

and its agent, the Board o f City Trusts, were perpetual and

immortal trustees9 so that no need for an accounting would

ever arise except in the event of some unusual circumstance

such as a charge o f mismanagement. On the other hand a

private trustee, or any one o f several private co-trustees,

in order to be discharged of liability, must file an account.

To accomplish the same purpose after the death o f a trustee,

his executor or administrator must do likewise. Fiduciaries

Act o f 1949, Sections 921, 981 (20 P. S. §§ 320.921,

320.981). In view o f the fact that there are thirteen

trustees, all appointed in their maturity, deaths and

resignations were to be expected with some frequency,

so it could have been anticipated that a triennial ac

counting would not only be desirable but essential10 The

period also coincides, as it should, with the period o f ap

pointment which, contrary to the lower court’s finding, is

not “ at will” but also for a term of three years. (7 Pa.

Fiduc. Rep. 606). Although the Orphans’ Court has not

explained the reason for this particular period, it can be

surmised that it was based on the judgment o f the court

that it would be better for the administration o f the trust,

8There is no support in this record for the lower court’s assump

tion that the Orhpans’ Court does not treat other large charitable

trusts having multiple appointed trustees in a similar manner. Mr.

John Diemand’s testimony that as a trustee of a small estate of a

deceased friend he does not account every three years, was not sworn

in, and has received no certificate of appointment hardly proves the

court’s point (R . 658a-659a).

9The City was selected as trustee because its existence is perpetual.

See Girard Will Case, 386 Pa. 548, 569, 127 Atl. 2d. 287, 296 (1956).

The death or resignation of a member of a city board acting as a

trustee does not require an accounting. Wiltsach Estate, 1 D. & C.

2d. 197 (Orphans’ Ct. Phila. County 1954).

10The latest triennial account approved by the Orphans’ Court,

merely supplemented by a “ bring-down” , will always be available for

the prompt discharge of a trustee or his estate.

2 2

which involves far more onerous duties than does a corpo

rate directorship (R . 673a-674a), if the appointments were

for a limited period rather than for life. There is no justi

fication whatsoever for drawing an inference that the O r

phans’ Court limited the term to make certain that its

appointees would be under the court’s control.

Again the lower court looks with suspicion on the fact

that the Trustees who were substituted for the Board

o f City Trusts were formally sworn in before the Orphans’

Court and several years later presented with certificates

o f appointment. There is no evidence that other trustees

have not been sworn in or presented with such certificates;

but, assuming this procedure was unusual, so is the stature

and historical significance o f the Girard Trust. The

Orphans’ Court has said that Girard’s W ill “ has become

a legend in Pennsylvania and the United States” , Girard

Estate, 4 D. & C. 2d 671 (1955). The trustees who have

been selected from the leaders o f the community and who

give freely o f their time and energy, are deserving of

recognition even if it consists only o f a brief ceremony

and a simple certificate.

Finally the lower court’s reliance upon the fact that

members o f the Orphans’ Court visited the College two

times during ten years as evidence of constitutionally

significant governmental involvement shows the extremes

to which that court has gone. On each o f these occasions the

members had been invited by the Trustees, the visits in

volved nothing more than a brief physical inspection, and

no member o f the court even stayed for the regular meeting

o f the trustees which followed immediately thereafter (R .

444a, 793a, 794a).

No member of the Orphans’ Court has ever involved

himself in the administration o f the College (R . 674a).

The docket entries o f that Court show that the only matters

upon which it has taken action since the appointment of

private trustees in 1959 have been petitions for the sale of

properties, petitions for rental of properties for more than

23

five years and petitions for the approval o f accounts (E x .

D - l l ) . Aside from this limited information, that Court

knows no more about the trust and the college, than do

members of the public.

Under these circumstances the relationship o f the Or

phans’ Court to the trust is such that the Court is not

involved in, nor even appears to be involved in, the execu

tion o f Girard’s admission policy. The only differences

between the administration o f this trust and any other are

the natural ones arising from the amount o f dollars in

volved, the number o f necessary trustees, and the onerous

nature o f the trustees’ duties which they perform without

compensation. To hold that the natural role o f the Orphans’

Court under these circumstances has created unconstitu

tional state action is either to manufacture a fiction or to

create a rule of law that would make all trusts, or at least

all large charitable trusts, subject to the Fourteenth

Amendment.

E. There Are No Other Relationships Between the

Girard Trust and the State Which Separately or

Together Constitute Significant State Involvement.

Although the lower court has placed its finding that the

College is “a governmentally sanctioned center o f racial

bias” primarily on the relationship o f the Orphans’ Court

since the substitution o f private trustee, it has also found

that there are “ further grounds for inferring a proscribed

involvement in the disciminatory design” (R . 863a). Each

o f these, however, is either too insignificant to involve the

state or so broad that it involves the state dangerously in

private education and even religion.

The first such additional ground is the fact that the legis

lature of the Commonwealth receives an annual report on

the investment and applications o f Girard’s residuary estate

and the condition o f the College. The making o f this re

port by the City trustee was required by Girard in his Will

(R . 64a). No legislation o f the Commonwealth or City

24

calls for this report. Nor is there any evidence that the

legislature has ever taken action with respect to any of

these reports, or that any representative o f the legislature

has even visted the College (R . 453a, 761a, 794a).

Inasmuch as Girard and not the Commonwealth re

quired these annual statements it can hardly be said, let

alone “ fairly” said, that the state has thereby involved itself

in the administration o f the College. The lower court has

rejected this point, however, on the ground that the trustee

ship of the City was also o f Girard’s making and that the

first Girard College case demonstrates that the source of the

involvement is immaterial. This ignores the nature o f the

involvement. When the City was acting as Trustee, it was

directly participating in the execution o f the policy and

therefore the source o f its authority was unimportant. In

merely receiving the reports, however, its role is completety

passive. It is neither logical nor realistic to say that there

has been “ state action” when in fact there has been no

action and no duty to act.

The lower court has also found support for its conclu

sion in “ the general supervision o f the State Department

of Public Instruction, the State Department of Welfare,

and other agencies concerned with the education and welfare

of the young” (R . 864a). Since there are no agencies

concerned with the education and welfare o f the young

other than the two named, we need consider only them.

Private schools in Pennsylvania are of two types. There

is the private school which is licensed under the Act of

June 25, 1947, P. L. 951 (24 P. S. § 2731 et seq.) and

which is subject to inspection by the State Board of Private

Academic Schools. Its license can be revoked for many

reasons. The private schools which are exempt from this

Act, notably schools which are accredited by recognized

accrediting associations and schools operated by bona fide

religious institutions, make up the second class. Girard is

a member o f this latter group since it has been accredited

by the Middle Atlantic States Association o f Secondary

25

Schools and Colleges (R . 273a).11 The only statutory re

quirements directed at these unlicensed private and religious

schools are that they should teach certain rudimentary sub

jects and the history o f the United States and Pennsylvania.

Public School Code of 1949, Sections 1511 and 1605 (24

P. S. §§ 15-1511, 16-1605). The Department o f Public

Instruction has no power even to compel compliance with

the minimum curriculum standards. Instead, the directives

all run to the child or the parent. Public School Code,

Sections 1327, 1332, 1333 (24 P. S. §§ 13-1327, 13-1332,

13-1333). Under these circumstances, it can no more be

said that the state is involved through the Department o f

Public Instruction in the selection of children to attend

Girard than it can be said to be involved in the selection

policies o f parochial or other religious schools.

The same final conclusion must be reached as to the

Department of Public Welfare, although it does have cer

tain powers of inspection and supervision at Girard. Under

Sections 2302 and 2303 of the Administrative Code (71

P. S. §§ 592, 593) that Department is given supervisory

power over all institutions which receive and care for

children, persons of unsound mind, expectant mothers, in

digent adults, the blind, and other handicapped persons.

The concern o f the Department, however, is the welfare of

the inmates and not their qualifications for admission on

the basis of race, creed or color. T o say otherwise, would

be to draw within the orbit o f the Fourteenth Amendment

all such charitable institutions.

The lower court also refers to “ tax exemptions and

other special concessions from public agencies” ; but again

these are common to almost all charities and the implica

tions of creating such a broad rule o f law are obvious.

These implications were equally apparent to the lower

court. To avoid them, it was said that “ standing alone” the

supervision and special benefits do not involve state action,

11This is a non-governmental association supported entirely by

contributions from schools which are members (R . 320a).

2 6

but they do so in this case when combined with the history

o f direct state operation and “ the not wholly unambiguous

manner in which that control was sought to be terminated.”

(R . 865a). It is strange indeed that having found that

the substitution of private trustees was merely in perform

ance of the Orphans’ Court’s traditional administrative

duties and “ standing alone” does not involve constitutional

implications (R . 856a), the lower court then finds the sub

stitution becomes “ not wholly unambiguous” when joined

with other state relationships, which also “ standing alone”

do not constitute state action, and then concludes that the

chemical reaction between all of these inert elements has

created an unconstitutional mixture.

In the next section we will deal with the invalidity of

the lower court’s technique o f adding together a number of

state relationships, each o f which is acknowledged to be

insignificant, to obtain a total which, contrary to the

principles of both arithmetic and logic, that court chooses

to call significant. For the present it should be sufficient to

say that not even all of these relationships taken together

tend “ to suggest to the community that the institution’s poli

cy o f racial discrimination is either practiced by or approved

by public authority” , the very test established by the lower

court. Even the most uninformed member o f the community

must be aware of the fact that public authority, while

performing the duties and according the privileges which it

owes by law to every private charitable institution for

children, officially disapproves of Girard’s personal selection.

F. All of the Insignificant or Customary Contacts Be

tween the State and the Girard Trust Cannot Be

Combined to Total Significant State Involvement.

The lower court’s opinion suggests that sheer quantity

o f instances o f State involvement, no matter how trivial or

peripheral each may be, can establish “ state action” . The

conclusion that the State is so involved in the individual’s

27

choice that the Constitutional prohibition has been violated

should not and cannot be based on a foundation o f straws,

no matter how many there may be. On the contrary, that con

clusion can only be reached if the State has so encouraged,

compelled or participated in the discrimination, or has pro

vided such support for the establishment, or has such a

property interest in the establishment that it can be said

fairly that the State has a significant measure o f respon

sibility for the discrimination.

The nature of the state involvement— and not the mere

volume— determines “ state action.” This is what was meant

in Burton by the much-quoted expression, “ sifting facts and

weighing circumstances” — all o f the contacts between the

establishment and the state must be examined, that is

“ sifted,” and those that are found to be unusual are

“ weighed” to determine if the state is involved “ to some

significant extent” (365 U. S. 722). In that case, the sift

ing of many facts disclosed that the governmental authority

owned the public parking structure and leased a portion

as a restaurant in order to obtain additional necessary

revenues to service its bonds, “ the restaurant constituted a

physically and financially integral and, indeed, indispensable

part o f the State’s plan to operate its project as a self-

sustaining unit” , the building is maintained by State funds,

and “ the profits earned by discrimination . . . are indispens

able elements in the financial success o f a governmental

agency.” (365 U. S. at 723-724).

In Evans Solicitor General Marshall argued that

there were many elements o f involvement between the

State and the park, that there is “ no need to decide

in this case whether any single one of them would,

if present in sufficient strength, require a finding that the

State is responsible for racial discrimination” , and that “ The

totality o f circumstances showing the State’s close partici

pation” compels the conclusion that the new trustees could

not constitutionally exclude anyone from the park on the

28

ground o f color (United States Brief, p. 11).12 There is

no echo o f this argument in Mr. Justice Douglas’ majority

opinion. Instead he relied upon the significant facts that

the park had been maintained by public funds, that there

was no evidence that it would not be so maintained in the

future, and that a park like Baconsfield is in the public sec

tor. Mr. Justice White, in concurring, relied solely upon his

conclusion that the state had encouraged the establishment

o f segregated parks by making them legally possible. The

totality argument was in fact rejected.

This totality concept adopted by the lower court was

also specifically rejected in Simkins v. Moses H. Cone

Memorial Hospital, .211 F. Supp. 628 (D . C. N. C., 1962).

There the District Court reviewed the many points o f con

tact there were between the government and two hospitals

which discriminated against Negro patients and physicians.

That court held that there was no constitutional state in

volvement, saying, in part (p. 639) :

“ While the plaintiffs argue that each o f the con

tacts defendant hospitals have with governmental

agencies is important, and each has a material bear

ing on the public character o f both hospitals, the

main thrust o f their argument is that the totality of

governmental involvement makes the hospitals sub

ject to the restraints o f the Fourteenth Amendment.

For this argument they mainly rely upon Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 81

S. Ct. 856, 6 L. Ed. 2d 45 (1961). But a careful

reading o f this case does not support plaintiff’s

argument.”

Although the District Court was reversed by the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit (323 F. 2d 959), it did not

12It is interesting to observe that in the same brief the Solicitor

General also speculated that the Supreme Court’s denial of certiorari

in the Girard appeal following the appointment of private trustees

was probably due to the fact that it was not clear then to the Supreme

Court that the new trustees would discriminate in view of the require

ments o f the Pennsylvania Public Accommodations Act. That Act

had never been cited to the United States Supreme Court as the

Jurisdictional Statement shows (Court Ex. A , Item 9 ).

29

disagree with the conclusion “ that ‘zero [the quantum of

each separate factor] multiplied by any number would still

equal zero.’ ” (323 F. 2d at 966). Instead, it found among

all those points of contact one significant relationship— the

hospitals were participating in and receiving funds under

the federal Hill-Burton program.13 That court said (p.

967 ):

“ Our concern is with the Hill-Burton program,

and examination o f its functioning leads to the

conclusion that we have state action here. Just as

the Court in the Parking Authority case attached

major significance to ‘the obvious fact that the

restaurant is operated as an integral part of a public

building devoted to a public parking service,’ 365

U. S. at 724, 81 S. Ct. at 864, 6 L. Ed. 2d 45, we

find it significant here that the defendant hospitals

operate as integral parts of comprehensive joint or

intermeshing state and federal plans or programs

designed to effect a proper allocation o f available

medical and hospital resources for the best possible

promotion and maintenance o f public health.”

In place o f this judicial technique o f sorting out the

many points o f contact with the government to determine

if there is any which can fairly be said to involve the

government to such an extent that it shares responsibility

for the discrimination, the lower court has intermingled all

o f the usual minor points of contact to form a heterogenous

mixture which it terms unconstitutional. But if it had

followed the proper course, it could not have entered the

injunction.

13See to the same effect, Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F. 2d (4th Cir.

1964). Also see Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 336 F. 2d

630, 634 (6th Cir. 1964) (in a case which involved discrimination

in a motel which was part of a redevelopment project, the court said:

“ The single pervasive fact . . . is that this motel is part and parcel

of a large, significant and continuing public enterprise— Capitol Hill

Redevelopment Project.” (emphasis added)).

30

G. Girard College Is Not “ Municipal In Nature” .

The lower court attempts to buttress its conclusion that

the state is still constitutionally involved in the administra

tion of Girard College by seeking to make it fit within the

framework o f Mr. Justice Douglas’ statement that, “ The

service rendered even by a private park of this character

is municipal in nature . . . Like the streets o f the company

town in Marsh v. Alabama, supra, the elective process of

Terry v. Adams, supra, and the transit system of Public

Utilities Comm’nw. Pollack, supra [343 U. S. 451 (1 9 52 )],

the predominant character and purpose o f this park is

municipal.” (382 U. S. at 301-302).14

This Court has already concluded that the Pennsylvania

Courts have held that Girard College is not a place o f public

accommodation under the Act o f June 24, 1939, P. L.

872, § 654 (18 P. S. § 4654) which includes schools but

which excludes establishments which “ are in their nature

distinctly private” . Commonwealth v. Brown, 373 F. 2d

771 (3d Cir. 1967). It seems inconsistent that it should

now be held that the College is performing a “ public

function” and is therefore constitutionally barred from dis