Rice v Arnold Petition for Writ Certiorari

Public Court Documents

November 29, 1951

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rice v Arnold Petition for Writ Certiorari, 1951. d41e712b-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b7f1cb70-3e4a-4f11-bd03-c3483b353658/rice-v-arnold-petition-for-writ-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

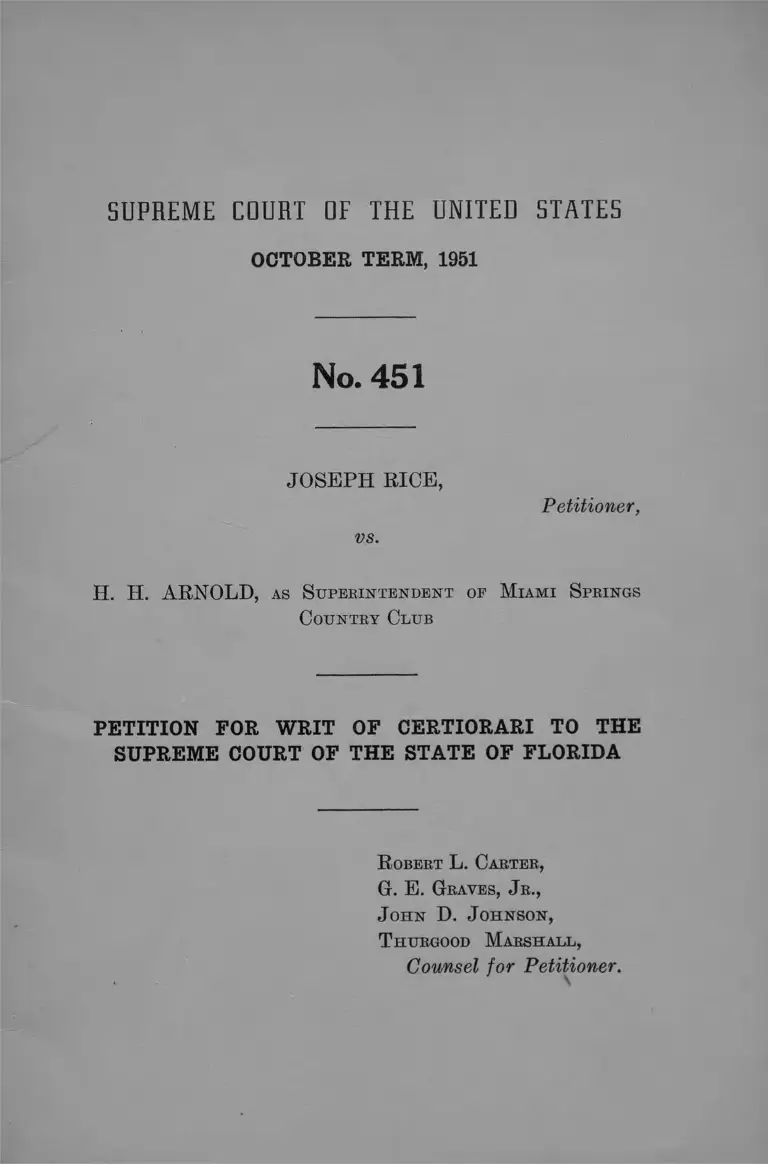

SUPREME EDURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

No. 451

JOSEPH RICE,

vs.

Petitioner,

H. H. ARNOLD, as S uperintendent op M iam i S prings

C ountry Club

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

R obert L. Carter,

G. E . Graves, J r.,

J ohn D. J ohnson ,

T hurgood M arshall,

Counsel for Petitioner.

INDEX

S u bject I ndex

Page

Petition for writ of certiorari.......................................... 1

Opinions B elow .......................................................... 1

Jnrisdiction ............................................................... 2

Question Presented .................................................. 2

Statement ................................................................... 2

Specification of Errors To Be Urged........................ 6

Reasons For Granting The W rit............................. 7

Conclusion ............................................................ 10

T able oe C ases C ited

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U.S. 637............. 2

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633.............................. 10

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U.S. 549......... 9

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 ................................... 10

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629........................................ 2

Takahashi v. Fish <& Game Commission, 334 U.S. 410. 10

—8621

S U P R E M E EDURT OF TH E U N IT E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

No. 451

JOSEPH RICE,

vs. Petitioner,

H. H. ARNOLD, as S u perin ten d en t of M ia m i S prings

C ou ntry C lub

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of Florida,

entered in the above-entitled case on August 31, 1951.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the court below, now being brought before

this Court, is reported in 54 So. 2d 114 and appears at page

23 of the record herein.

2

Jurisdiction

Judgment was entered on August 31, 1951, by the Su

preme Court of Florida (R. 32). The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under Title 28, United States Code, Sec

tion 1254.

Petitioner is here filing a petition for writ of certiorari

for a second time. On March 24, 1950, the State of Florida

entered judgment against petitioner, 45 So. 2d 195 (R.

14-19), and a petition for writ of certiorari was filed in this

Court. On August 16, 1950, the petition for writ of certi

orari was granted, 340 U. S. 848 (R. 21), the judgment

was vacated and set aside, and the cause remanded for

reconsideration in the light of subsequent decisions of this

Court in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629; and McLaurin v.

Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637.

Question Presented

May a state, in operating a public golf facility, condition,

restrict or limit the use and enjoyment of such facility on

the basis of the applicant’s race or color without violating

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

The City of Miami, Florida, owns and operates a golf

course known as the Miami Springs Country Club. It is

the only publicly-owned and operated golfing facility in the

city. Respondent is the duly appointed and acting Super

intendent of said public golf course and has the power and

duty to make and enforce rules and regulations governing

the use and enjoyment of these facilities by the general

public (R. 1).

Prior to April 27, 1949, respondent had promulgated and

was enforcing a rule and regulation under which Negro

3

citizens were permitted to use the Miami Springs Country

Club golf course only on Monday of each week, the remain

ing six days being reserved for the exclusive use of white

persons (R. 5).

On April 27, 1949, that day being a Wednesday and a day

which under respondent’s rule and regulation persons of

the Negro origin were not entitled to use of the golf course,

petitioner, a Negro, sought respondent’s permission to play

on the golf course. Such permission was denied pursuant

to the rule and regulation heretofore referred to (R. 3).

On June 3, 1949, petitioner filed in the Circuit Court of

the Eleventh Judicial Circuit of Florida in and for Dade

County, a petition for an alternative writ of mandamus to

require respondent to permit him to use the said golf course

at all times during which said golf course was open to the

general public and subject only to such rules and regulations

as were applicable to all persons (R. 1).

The alternative writ, as prayed for, was issued by the

Circuit Court of Dade County on June 10, 1949 (R. 3). In

accordance with the terms of the alternative writ, re

spondent thereupon filed his return and answer (R. 4). In

his answer, respondent sought to defend the rule and regu

lation under which petitioner was denied use of the golfing

facilities on the following grounds: (1) That the public

policy of the state and of the City of Miami required the

segregation of the races in the use of public facilities; (2)

that for a period of six days in April, Negroes were per

mitted to use the golf course without restriction; (3) that

the golf course is self-sustaining, depending upon the fees

paid by the golfers; that an average of 200 players per day

is necessary to sustain it on a paying basis; (4) that follow

ing the admission of Negro players, white players an

nounced their intention of withdrawing their patronage if

forced to share such facilities with Negroes; (5) and in

view of the small number of Negro golfers who took ad

4

vantage of these facilities it would become necessary for

the City of Miami to abandon the golf course unless an

alternative regulation for its use was adopted; (6) that the

present policy was adopted limiting Negro players to the

use of said facilities on one day of each week, reserving the

remaining six days for the exclusive use of white persons;

(7) and that since the promulgation of this latter rule, the

number of Negro golfers has not increased sufficiently to

warrant increasing the time allotted for them in the use of

these facilities (R. 4-6).

Petitioner, thereupon, moved for a peremptory writ of

mandamus on July 18, 1949, upon the grounds that respond

ent’s allegations set forth in the return and answer, if

proved, would not constitute a legal defense (R. 6-7). The

motion for peremptory writ of mandamus was denied by

the Circuit Court, the alternative writ dismissed and final

judgment granted the respondent on June 22, 1949 (R. 7-9).

An appeal was thereupon taken to the Supreme Court of

the State of Florida. On appeal, petitioner contended that

the rule and regulation promulgated by respondent whereby

petitioner, because he is a Negro, was permitted to use the

golf course only on Mondays, deprived petitioner of the

equal protection of the laws as guaranteed under the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

The Supreme Court of Florida, on March 24, 1950, affirmed

the judgment of the lower court (R. 14-19). In so holding,

the Court said:

“ . . . It does not appear by the record that the

one day allotment of the facilities of the course to the

negroes discriminated against the negro race. The

days of playing each week were apportioned to the

number of white and colored golfers according to the

record of the course kept by the respondent. If an

increased demand on the part of the negro golfers is

made to appear, then more than one day each week will

be allotted . . . ” (R. 18-19).

5

Petitioner then brought the case to this Court. Between

the time of the decision of the Florida Supreme Court and

filing- of the petition for writ of certiorari in this Court,

Sweatt v. Painter, supra, and McLaurin v. Board of

Regents, supra, were decided. On October 16, 1950, this

Court, in a per curiam opinion, granted the petition for

writ of certiorari, vacated and set aside the judgment of

the Florida Supreme Court and remanded the cause for

reconsideration in the light of the Sweatt and McLaurin

cases (R. 21). On the return of this Court’s mandate to

the Supreme Court of Florida, ordering the reconsideration

of the cause, the Supreme Court of Florida refused to per

mit the filing of briefs by counsel for either party and

refused to permit oral argument as to the effect of the

McLaurin and Sweatt decisions on the instant controversy.

Without ordering any new hearing or permitting the filing

of any new briefs, the court, on August 31, 1951, handed

down its Opinion and judgment, with two justices dissent

ing (R. 23), in which it held that the McLaurin and Stveatt

cases were not applicable to the instant controversy. The

court said:

“ It is significant that in the Sweatt case the court

was urged to hold that discrimination inevitably results

wherever the ‘ separate but equal’ doctrine is applied

with reference to public facilities furnished persons of

different races; but the court said, ‘ broader issues have

been urged for our consideration, but we adhere to

the principle of deciding constitutional questions only

in the contest of the particular case before the court’,

thereby declining to destroy the well established rule

that has been applied ever since the adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution to the

effect that where separate but equal facilities are pro

vided persons of different races, no person of either

race is thereby denied the full protection of his con

stitutional rights. Among the numerous decisions

enunciating this principle, we cite only Plessy v. Fergu-

6

son . . . because of its clarity and because tbe

Supreme Court in tbe Sweatt case expressly declined

to ‘ re-examine’ that holding, thus impliedly directing

all courts subordinate to it in the field of constitutional

construction, to continue to recognize that decision as

binding authority. We are directed to reconsider our

conclusions in the case before us in the light of the

decision in the Sweatt case. A part of that decision

was the refusal of the Supreme Court to modify Plessy

v. Ferguson.

“ In the case before us, there is no question of the

equality of the physical facilities offered petitioner

with which he may enjoy his constitutional right to

engage in the game of golf upon public property. The

facilities offered petitioner are identical with the fa

cilities offered persons of other races by the City of

Miami.” (R. 28-29)

The Court then affirmed the judgment of the Circuit

Court of and for Dade County in denying petitioner’s

motion for peremptory writ of mandamus.

Whereupon, petitioner, for a second time, brings the

cause here for review by this Court.

Specification of Errors to Be Urged

The Supreme Court of Florida erred:

1. In refusing to hold that respondent’s rule and regu

lation, under which petitioner and all other Negroes, solely

because of color, were prohibited from using the Miami

public golf course except on Monday of each week and white

persons were permitted to use said facilities on all other

days, was an unconstitutional infringement of petitioner’s

rights as secured under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

2. In refusing to hold that petitioner was entitled to un

restricted use of the Miami Springs Golf Club subject only

7

to the same rules and regulations which were applicable to

all other persons.

3. In refusing to hold that respondent’s rule and regula

tion, under which one day per week was set aside for the

exclusive use of the Miami public golf course by Negroes

and Negroes were not permitted to use the golfing facilities

on any other day, was a denial of the equal protection of

the laws as defined by this Court in Sweatt v. Painter, supra,

and McLaurin v. Board of Regents, supra.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

1. The mandate of this Court, vacating and setting aside

the initial judgment of the court below and remanding the

cause for reconsideration in the light of Sweatt v. Painter,

supra, and McLaurin v. Board of Regents, supra, in effect

has been ignored. The court below held that the McLaurin

and Sweatt cases were not applicable and decided the in

stant controversy as if those two cases did not exist.

In its original opinion and judgment, before the Court

for review last term, the Supreme Court of Florida sus

tained respondent’s rule and regulation, under which peti

tioner solely because of his color, was denied use of the

Miami golf course except on Mondays, as being consistent

with the requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment in

that the allocation of one day per week to Negroes to use

the golf course was deemed to afford petitioner substan

tially equal accommodations. On remand, the court below

found that the McLaurin and Sweatt cases had left un

changed and undisturbed its original impression of the

applicable law and that the special rule and regulation

restricting petitioner’s use of the Miami public golf course,

solely because he is a Negro, did not constitute a denial of

substantially equal accommodations required by the Four

teenth Amendment.

8

Thus, petitioner stands in exactly the same position as

when he filed his original petition for writ of certiorari last

term. It is submitted that had this been the intention or

expectation of this Court, the original petition for writ of

certiorari would have been denied or, if granted, the judg

ment of August 24, 1950, would have been affirmed.

2. This case is a phase of the same problem raised in the

Mcbcmrin and Sweatt cases, and the principles governing

disposition of those cases control determination of the in

stant controversy. Those cases dealt with public educa

tional facilities and this case deals with public recreational

facilities. The constitutional question raised, however, is

identical. Petitioner is here complaining of being set apart

by the state because of his color, of being subjected to spe

cial rules and regulations different from those applicable

to all other persons with respect to his use of a public golf

facility. He asserts that the state is without power to treat

him differently than it treats other persons solely because

of the accident of his color and that by allowing him to use

the public golf course subject to special conditions, the state

is depriving him of equal public accommodations in viola

tion of rights secured under the Fourteenth Amendment.

McLaurin and Siveatt made the same complaint and the

same assertion except that they were concerned with public

graduate and professional instruction.

In the McLatmn and Sweatt cases, the question decided

by this Court was the extent to which the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment limited “ the power

of a state to distinguish between students of different races

in. professional and graduate education in a state univer

sity.” While the specific constitutional determination

made in those cases concerned state power to make racial

distinctions among students in state graduate and profes

sional schools, the basic and underlying problem before the

Court was the extent to which the Fourteenth Amendment

9

limits state power to make distinctions among persons

based upon race or color in the use and enjoyment of public

facilities. To have spoken in terms of this basic issue in

either McLaurm or Sweatt would have involved a deter

mination of a constitutional question broader than neces

sary to dispose of the specific problem which those cases

brought before the Court, contrary to normal Supreme

Court practice. Sweatt v. Painter, supra at 631; Rescue

Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U. S. 549. Yet the constitu

tional principles enunciated to determine the narrow prob

lem at hand are subsequent guides to decisions when other

facets of the same broad question come before the Court,

such as is now presented in the instant case. Recognition

of this fact, it is submitted, caused this Court to set aside

and remand the original judgment in this case because the

decision of the court below was reached prior to, without

benefit of the reasoning in, and by application of principles

at war with those enunciated in the Mcba/urin and Sweatt

decisions.

3. The reasons wdiieh the court below advances as a basis

for distinguishing this case from the Siveatt and McLcmrin

cases are, we submit, the very reasons which conclusively

demonstrate the unconstitutionality of respondent’s rule

and regulation. Said the court:

“ Turning to the facts of the case before this court,

we take judicial notice that the game of golf is of such

a nature that it requires the maintenance of links which

cover a considerable area and that it can be played only

by persons alone or in very small groups not exceed

ing, execept in unusual cases, four persons, although

several of such groups may play simultaneously on

different parts of the course. There are of necessity

some, but limited, contacts between the various groups

so playing, particularly around the club house and

starting tees. The purpose and function of the game

is to obtain the pleasure and exercise incident to the

10

playing and the rivalry and association between per

sons who arrange in advance to play together. The

exercise, the rivalry and the association are not en

hanced by the other persons who may, on the same day

or during the same hours, elect to enjoy the facilities.”

Since contacts are limited and the purpose of playing-

golf is to obtain pleasure in exercise and in the rivalry

and association between persons who arrange to play in

advance, there is no valid or important state interest which

requires petitioner’s discriminatory treatment. The court’s

opinion demonstrates that petitioner’s unrestricted use of

the golf course is no threat to public peace, and that white

persons using the course who do not care to associate with

Negroes would not be forced into such contact against their

will. Thus, the reasons normally advanced in justification

of racial segregation are entirely absent in this case.

4. The rule and regulation here under attack are based

on race alone, and race has long been held to be an improper

basis for state action. Shelley v. Kraemer 334 U. S. 1;

Takahaski v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 TJ. S. 410;

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, this petition for writ of certi

orari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert L . C arter ,

G. E. G raves, J r .,

J ohn D . J o h n son ,

T httrgood M arsh a ll ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

Dated: November 29, 1951.

(8621)