Alexander and Dennis v. AVCO Corporation Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

November 19, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alexander and Dennis v. AVCO Corporation Brief for Appellees, 1975. e9266d6d-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b7fe5ec0-157e-43dd-8588-34beec1711b9/alexander-and-dennis-v-avco-corporation-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

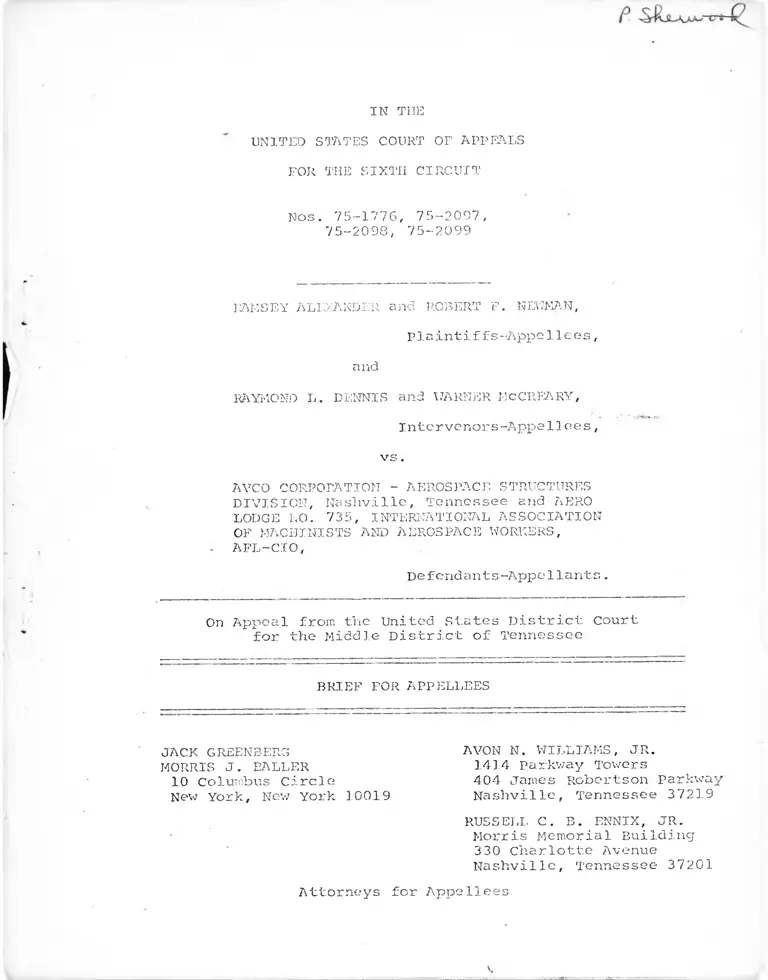

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 75-1776, 75-2097,

75-2098, 75-2099

RAMSEY ALEXANDER and ROBERT F. NEUMAN,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

RAYMOND L. DENNIS and WARNER McCREARY,

Intervenors-Appellees,

vs.

AVCO CORPORATION - AEROSPACE STRUCTURES

DIVISION, Nashville, Tennessee and AERO

LODGE NO. 735, INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION

OF MACHINISTS AND AEROSPACE WORKERS,

AFL-CIO,

Defendants-Appe Hants.

On Appeal from the united States District Court

for the Middle District of Tennessee

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

JACK GREENBERG

MORRIS J . BALLER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkw

Nashville, Tennessee 3721

RUSSELL C. B. ENNIX, JR.

Morris Memorial Building

330 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

for AppelleesAttorneys

m

£>

I N D E X

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................

STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED ......

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ................. 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS .................... 7

A. The Historical Framework of

Discrimination ................ 7

B. Structure and Nature of Employment

Opportunities at Avco Since 1965 9

lv Avco's operations and jobs ... 9

2. The structure of job

opportunities ........... 11

C. Discrimination in Job Opportunities 13

D. The Globe-Wernicke Incident ...... 19

E. The Individual claims of Alexander,

Newman and Dennis ............. 22

ARGUMENT"

Introduction ......................... 24

I. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ERR IN

ALLOWING THIS CASE TO PROCEED AS

A CLASS ACTION FOR REDRESS OF CLASS-

V7IDE DISCRIMINATION............... 2 5

A. This Case Is Maintainable As

A Rule 23(b)(2) Class Action

For The Relief Plaintiffs

Seek ...... ................. 25

B. The Timing of class Certifica

tion and Notice in This Case

Does Not Preclude Class Action

Treatment ................... 28

I N D E X [cont'd]

Page

II. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT

ABUSE ITS DISCRETION IN FRAMING

AN APPROPRIATE INJUNCTIVE REMEDY

FOR APPELLANTS' DISCRIMINATORY

JOB OPPORTUNITY PRACTICES ..... 36

A. The District court's Remedia].

Approach Was Appropriate and

Necessary .................. 36

B. The Remedial Measures Granted

By the District Court are Ap

propriate and Necessary ..... 40

1. Plant Seniority ......... 40

2. Partial elimination of

job equity......... 42

3. The bidding system. 45

4. Evaluation of qualifications 46

5. Special training rights for

black employees ........... 47

: 6. Special racial grievance

procedure.......... 47

7. Summary.... ............... 49

III. THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY HELD

THAT APPELLANTS UNLAWFULLY DIS

CRIMINATED AGAINST BLACK EMPLOYEES

IN THE GLOBE-WERNICICE INCIDENT..... 50

IV. THE COURT BELOW CORRECTLY DETERMINED

THAT THE NAMED PLAINTIFFS WERE VICTIMS

OF INDIVIDUAL DISCRIMINATION ........ 55

A. The Ramsey Alexander Claim ..... 56

B. The Robert Newman Claim ....... 59

C. The R. L. Dennis Claim ......... 62

-ii-

I N D E X [cont'd]

Page

D. The District Court Correctly

* Decided The Individual Claims 64

V. THE AWARD OF ATTORNEYS' FEES TO

PLAINTIFFS WAS A REASONABLE EXERCISE

OF THE DISTRICT COURT'S DISCRETION 66

1. The time and labor required..... 68

2. The amount involved and the result

obtained ........... 68

3. The contingency of any recovery 69

4. Novelty and difficulty of issues 69

5. Experience, reputation and

ability of counsel .............. 70

CONCLUSION...... 73

REPORT OF AVCO CORPORATION PURSUANT TO PARAGRAPH

10 OF ORDER OF FEBRUARY 11, 1975

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

-111-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Cited

Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. , 13, 25, 27,

45 L.Ed. 280 (1975) ............. ..... 39, 67

Alexander v. Avco Corp., M.D. Tenn. 2, 20, 29,

C.A. No. 4338 ...... .................. 70, 71

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1974) ................. 39, 48

Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d

543 (4th Cir. 1975) ................ . 55

Bijoel v. Benson, 513 F.2d 965

(7th Cir. 1975) .... .................. 33, 35

Blonder-Tongue Labs v. University Foundation,

402 U.S. 313 (1971) .................. 34

Blue Bell Boots, Inc. v. EEOC, 418 F.2d

355 (6th Cir. 1969) ...... ............ 65

Boles v. Union Camp Corp., ___ F.Supp. ___

(S.D. Ga., C.A. No. 2604, Sept. 17, 1975) 73

*

Bowe v. Colgate Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d

711 (7th Cir. 1969) ................... 26

Brotherhood of Railroad Signalmen v. Southern

Railway Co., 380 F.2d 59, (4th Cir. 1967) 72

Bryan v. Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co.,

59 F.R.D. 616 (W.D. Pa. 1973),

aff*d 494 F.2d 799 (3rd cir. 1974) ..... 73

Burns v. Thiokol Chemical Corp., 483 F.2d

300 (5th Cir. 1973) .................... 66

Bush v. Lone Star Steel Corp., __, F. Supp.___

(E.D. Tex., C.A. No. 1420, August 6, 1975) 73

-iv-

Page

City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp.,

495 F .2d 448 (2nd Cir. 1974) .......... 69, 70

Dewey v. Reynolds Metals Co., 429 F.2d

324 (6th Cir. 1970), aff'd by equally

divided Court 402 U.S. 689 (1971) ...... 70

EEOC v. Detroit Edison C.o., 515 F.2d 26, 29, 37,

301 (6th Cir. 1975) ................... 44, 49, 55

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 30, 31,

156 (1974) ............................ 32, 35

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 391 F.2d

555 (2nd Cir. 1968) ................... 31, 35

Electronics Capital Corp. v. Shepherd,

439 F.2d 692 (5th Cir. 1971) .......... 67

Elliot v. Weinberger, ___ F.2d ____,

44 U.S.L.W. 2175 (9th Cir. 1975) ...... 33

Foster v. City of Detroit, 405 F.2d 138

(6th Cir. 1968) ........................... 34

■Franklin v. Troxel Mfg. Co., 501 F.2d

1013 (6th Cir. 1974) ...................... 65

Franks/v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

495 F.2d 398 (5th Cir. 1974), cert.denied

419 U.S. 1050 (1974), cert, granted on

other issue 420 U.S. 989 (1975) ....... 26, 39, 47

Frost v. Weinberger, 515 F.2d 57

(2nd Cir. 1975) ....................... 31, 32

Garrett v. City of Hamtramck, 503 F.2d

1236 (6th Cir. 1974) .................. 29

•'Glover v. St. Louis-San Francisco Rwy. Co.,

393 U.S. 324 (1969) ................... 48

Goss v. Bd. of Educ., 373 U.S. 683 (1963) 70

—v—

Page

Graniteville Co. (Sibley Div.) v. EEOC,

438 F.2d 32 (4th Cir. 1971) ........

Gregory v. Hershey, 311 F.Supp. 1

(E.D. Mich. 1969) ....... -..........

Gregory v. Tarr, 436 F.2d 513

(6th cir. 1971) ....................

Griggs v. Dube Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971) ..........................

Hall v. Werthan Bag Co., 251 F.Supp. 184

(M.D. Tenn. 1966) ............. .

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) ....

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co.,

486 F.2d 870 (6th Cir. 1973) ........

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d

28 (5th Cir. 1968) ..................

Jersey Central. Pov;er & Light Co. v. Local

327, IBEW, 508 F.2d 687 (3rd Cir. 1975)

.Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.

488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) .........

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974) ............

Kelley v. Board of Education, 463 F.2d

732 (1972), cert, denied 409 U.S.

1001 (1973) ..........................

Lea v. Cone Mills corp., 467 F.2d

277 (4th Cir. 1972) ..................

66

35

35

13, 43

52, 53,

27, 70,

71

31

26, 40,

46, 52,

27, 55

44, 54

67, 68

70, 71

26

44

53

69

71

67

-vi-

Page

Lindy Brothers Builders, Inc. v. American

Radiator & Standard Sanitary Corp.,

487 F.2d 161 (3rd Cir. 1972) ............ 67, 69

Local 189, United Papermakers & paperworkers

v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir.

1969), cert, denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970) .. 44, 45

Long v. Sapp, 502 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1974) .... 55

McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ................................... 65

McFerren v. Board of Educ., 455 F.2d 199 (6th

Cir. 1972), cert, denied 407 U.S. 934

(1972) ................................... 70

McSwain v. Anderson County Board of Educ.,

138 F. Supp. 570 (E.D. Term. 1956) ...... 70

Mapp v. Board of Education, 477 F.2d 851

(6th Cir. 1973), cert, denied 414 U.S. 1022

(1974) ................................... 71

Meadows v. Ford Motor Co., 510 F.2d 939 (6th

Cir. 1975) ...............................

26, 40,

44, 54

Monroe v. Board of Educ., 391 U.S. 450 (1968). 70

Mullane v; Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co.,

339 U.S. 306 (1950) ..................... 31, 32

Newman v. Avco Corporation,(M.D. Tenn.) C.A.

No. 5258 .................................

2, 29,

70, 71

Newman v. Avco Corporation, 451 F.2d 743

(6th Cir. 1971).......................... 2, 3

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S.

400 (1968) ............................... 67

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968) ......................... 27

Pasquier v. Tarr, 444 F.2d 116 (5th Cir.

1971) .................................... 35

-vii-

Page

Pettway v. American cast Iron Pipe Co.,

F. Supp. ___ (N.D. Ala., C.A. No.

66-315, June 12, 1975) .................. 73

Pettway v. American cast Iron Pipe Co., 26, 39,

494 F. 2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974)............. 45, 49

Ramey v. Cincinnati Enquirer, Inc., 508 F.2d 67, 68, 69

1188 (6th Cir. 1974)..................... 70, 71

Reed v. Arlington Hotel, 476 F.2d 721 (8th

Cir. 1973), cert, denied 414 U.S. 854

(1974)............ ....................... 55

Rice v. Gates Rubber Co., 521 F.2d 782 (6th

Cir. 1975) 71

Rich v. Martin-Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333

(10th Cir. 1975) 66

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S.

1006 (1971) 26

Rock v. Norfolk & Western Rwy. Co., 473 F.2d 1344 (4th Cir. 1973), cert, denied 412

U.S. 933 (1973)...................... 39

Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505

F. 2d 40 (5th Cir. 1974) 29

Rolfe v. Board of Educ. of Lincoln County,

391 F. 2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968) ............. 70

Schrader v. Selective Service System, 470

F. 2d 73 (7th Cir. 1972) 35

Smith v. Holiday Inns, 336 F.2d 630 (6th Cir.

1964) 70

Smith v. South Central Bell Telephone Co.,

518 F. 2d 68 (6th Cir. 1975) ............. 71

Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393 (1975) .......... 30, 32

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F. Supp. 87

(E.D. Mich. 1973) .................... 46

-viii-

Thornton v. East Texas Motor Freight,

497 F.2d 416 (6th Cir. 1974) ....

Page

40

United States v. Georgia Power Co., _

7 EPD <j[ 9167 (N.D. Ga. 1974)

F.Supp.

entering decree on remand from 474 F.2d

906 (5th Cir. 1973) ......... *........ 49

United States v. Hayes International corp.,

456 F.2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972) ..........

United States and v. united States Steel

Corp., 520 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975) ...

United States v. IBEW Local 38, 428 F.2d

144 (6th Cir. 1970) ...................

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86,

315 F.Supp. 1202 (W.D. Wash. 1970),

aff'd 443 F- 2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied 404 U.S. 984 (1971) ••••*••

United States v. Local Union No. 212,

472 F.2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973) ...........

United States v. Masonry Contractors Assn,

of Memphis, Inc., 497 F.2d 871

(6th cir. 1974) .......................

United States v. United States Steel Corp.

6 EPD 51 8790 (N.D. Ala. 1973) .........

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of Inter

national Harvester Co., 502 F.2d

1309 (7th Cir. 1974) ..................

Watkins v. united Steelworkers of America,

Local No. 2369, 516 F.2d 41

(5th Cir. 1975) .......................

Weeks v. Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph

CO., 467 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1972) ......

47

40

15, 40

73

44, 53

54, 55

44

67

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., _

508 F.2d 239 (3rd Cir. 1975), cert, denied

421 U.S. 1011 (1975) ........... ........

28, 30,

32, 33

Zeilstra v. Tarr, 466 F.2d 111 (6th Cir. 1972) 35

-ix-

Statutes, Rules, and other Authorities

* Page

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ........................... 1, 55

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. (Title VII,

Civil Rights Act of 1964) .............. passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (II) (Title VII,

§ 703 (h) ) ............................ 44, 54, 55

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (g) (Title VII,

§ 706(g) .............................. 38, 39

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (Title VII,

§ 706 (k) ............................. 66

Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure —

Rule 23 (a) ............. .................. 55

Rule 23(b) (2) .......................... 2, 26, 27, 28,

30, 31, 32, 34,

73

Rule 23(b) (3) .......................... 5, 27, 28, 30,

31

Rule 23 (c) (1) .......................... 28, 29

Rule' 23 (c) (2) 28, 30, 31

Rule. 23 (d) (2) .......................... 31

Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. 66

Advisory Committee Note to 1966 Amendment 26, 27,

of Rule 23, 39 F.R.D. 69, 102 (1966) ___ 31, 32

American Bar Association Code of Professional

Responsibility, Ethical Consideration

2-18 (1961), enforced by Disciplinary

Rule 2-106 ............................. 68

3B J. Moore, Federal Practice 5[ 23.50

(ed. 19 ) ............ ................ 29

118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972) ................. 39

-x

Statement of Questions Presented

Where“the District Court correctly found, upon a massive

evidentiary record, that the appellant Company and. Union had

engaged in a continuing comprehensive scheme of discrimination

against black employees:

1. Did the District Court err in certifying the case as

a class action upon the evidence presented at trial and in direct

ing notice to class members at the stage of proceedings when their

individual rights were to be determined?

2. Did the District Court abuse its broad remedial dis

cretion in ordering temporary modification of those current

employment practices which the court identified as responsible for

exclusion of black workers from equal job opportunities?

3. Did the District Court err in concluding that appellants

discriminated in the Globe-Wernicke situation by granting white

employees extra-contractual rights resulting in displacement of

a group of black employees who were contractually entitled to

retain their jobs?

4. Was the District Court clearly erroneous in its deter

mination, based upon a detailed record and specific findings of

fact, that the named plaintiffs-appellees were victims of indi

vidual discrimination?

5. Did the District Court abuse its discretion in determin

ing the amount of attorneys' fees for the prevailing plaintiffs?

-xx-

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 75-1776, 75-2097,

75-2098, 75-2099

RAMSEY ALEXANDER and ROBERT F. NEWMAN,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

.- RAYMOND L. DENNIS and WARNER MCCREARY,

Intervenors-Appellees,

vs.

AVCO CORPORATION - AEROSPACE STRUCTURES

DIVISION, Nashville, Tennessee and AERO

LODGE NO. 735, INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION

OF MACHINISTS AND AEROSPACE WORKERS,

• AFL-CIO,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Tennessee

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement of the Case

These appeals arise from two employment discrimination

class actions under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. and 42 U.S.C. § 1981, consolidated,

tried, and decided by the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Tennessee, Hon. L. Clure Morton, J. The

1/appeals are taken from several Orders (A. ) granting

various measures of relief to the plaintiff black employees,

appellees here, pursuant to the Court's Memorandum Opinion

(A. ) finding that the defendant Company and Unions,

appellants here, had been long engaged in a comprehensive scheme

of racially discriminatory employment practices. The Newman

2/case has previously been the subject of a significant decision

of this Court, 451 F.2d 743 (1971). Because the earlier-filed

Alexander case" involves the same subject matter as Newman, the

District Court consolidated the two actions for all purposes

after this Court's remand of Newman (A. ).

Both the Newman and Alexander complaints (A. /A. )

alleged that defendants were engaged in across-the-board

practices of discrimination in every aspect of employment at

Avco's Nashville plant. Both complaints properly pleaded that

class action proceedings and class-wide relief were appropriate

(A. , A. ). in denying an early motion to dismiss in

Alexander, the District Court held that "the action is a proper

class action" (A. ). Subsequently, this Court, in remanding

Newman for trial, noted:

As to these latter charges [of violations of

Title VII by Avco], appellant [Newman] is an

appropriate representative of the class

T T Citations in this form are to pages of the single Appendix

filed in these appeals. Citations to "Tr." are to the transcript

of trial proceedings.

2/ Newman v. Avco Corporation, et al., C.A. No. 5258, filed

December 20, 1968.

3/ Alexander v. Avco Corp., et al., C.A. No. 4338, filed January

13,’1966.

- 2-

__________________ s : s : i ____________________________________________________________________________________________ i • • - :__________________________________________«________________________

described in the complaint and the class action

aspect of this suit must likewise be the subject

of hearings, findings and conclusions. 451 F.2d

at 749.

Plaintiffs filed a Rule 23 motion for class determination prior

to the start of trial (A. ). Likewise, the pre-trial

orders entered before trial specify that plaintiffs seek full

relief, including back pay, on behalf of their class (A. ,

A. ) .

After voluminous discovery and procedural litigation

1/(see A. ), the District Court conducted a trial of 11 days

in June and.July-August, 1972. After receiving extensive post

trial briefs, the District Court entered a Memorandum comprising

its decision on December 18, 1973 (A. ). The Court found

a pattern of racial discrimination in employment as pervasive,

virulent, and tenacious as any this Court is ever likely to

review. Specifically, Judge Morton held (A. ) :

The court concludes that subsequent to the

effective date of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, July 2, 1965, the defendant Avco

racially discriminated, in violation of the Act,

against the class of Avco employees represented

by plaintiffs as follows:

(1) by preserving through the seniority

and promotion systems past discrimination in

the areas of classification as to the types of

employment available to black employees,

training, working conditions, promotions,

transfers, compensation and terminations;

(2) by failing, through its supervisory

personnel, to afford black employees the same

training afforded to white employees, thereby

4/ Notably, intervening plaintiffs Dennis and McCreary were

allowed to file complaints in intervention on July 29, 1971

(A. ) .

-3-

effectively excluding black employees from

opportunities for advancement to semi-skilled

and skilled occupations;

(3) by considering subjective and

racially discriminatory evaluations of its

foremen and other supervisory personnel, in

determining qualifications for advancement

without ascertaining whether or not such eval

uations were affected v/ith racial bias; and

(4) by discriminating against black

assembler bench and jig employees in the Globe-

Wernicke incident.

As to defendant Aero Lodge No. 735, the court con

cludes that defendant union has acquiesced and par

ticipated in these discriminatory practices of Avco,

and has represented the interests of its black members

unfairly, inadequately, arbitrarily, discriminatorily,

and -in bad faith in violation of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Court also found that Avco, after the effective -date of Title

VII, racially discriminated against plaintiffs Alexander (by

denial of promotions, A. ), Newman (in job classification,

working conditions, refusal to transfer, and discharge, A. ),

and Dennis (by pretextual discharge, A. ). The Court

further found that Alexander and Newman had each been subjected

to racial discrimination by Aero Lodge 735 (by its provision of

unfair, inadequate, arbitrary, discriminatory, and bad faith

5/

representation of their interests, A. , ). The District

Court also concluded that plaintiffs could properly maintain the

cause as a broad class action under Rule 23(b)(2), Fed.R.Civ.P.

w The Court also found that Avco and Aero Lodge 735 had discrim

inated against the other intervening plaintiff, McCreary, in at

least 7 different ways while he worked at Avco, but denied his

claim of unlawful discharge (A. ).

-4-

6/

(A> )# but did not order notice to class members.

Extensive proceedings to determine the remedy followed

the Court's Memorandum decision. During these proceedings the

Court, apparently because of concern about the failure to give

earlier notice to class members, decided in an August 20, 1974

Memorandum to terminate the class action (A. )• Thereafter,

on plaintiffs' motion for reconsideration of this ruling and

their motion to give notice to class members (A. ), the

Court on February 11, 1975 reinstated the class action and

ordered individual mailed notice to class members as well as

newspaper publication notice (A. , )•

In its August 20, 1974 Memorandum, the Court had outlined

its intentions with regard to injunctive relief for the class

and the individual plaintiffs' remedy (A. ). On February

11, 1975, it entered an Order embodying and implementing (and

somewhat modifying) the injunctive remedy previously outlined

). m this Order the Court enjoined further discrimina

tion by defendants and decreed fundamental changes in Avco's

practices in order to eliminate the effects of defendants'

discrimination. The Court ordered: (1) applications to be

updated to reflect blacks' qualifications and exclude subjective

supervisory opinions (A. ); (2) blacks to be given full

6/ The court defined the class to include "past, present, and

prospective black employees of the defendant Avco Corporation

and past, present and prospective members of Aero Lodge a l l ' d

who allegedly have suffered or may suffer by reason of the all g

discriminatory practices of the defendants" (A. ).

7/ The court nevertheless ruled that the approximately 52 black

employees discriminated against in the " G lo b e -V Je r n ic k e i n c i d e n t

(see page 21, infra), would be invited to intervene much as m a

Rule 23(b)(3) class action (A. ) •

-5-

bidding opportunities (A. ); (3) plant wide seniority to

govern black-white job competition for promotion, transfer, and

layoff purposes (A. ); (4) special "job equity" preferences

held by white employees to be limited (A. )‘ (5) increased

qualifying periods and training to be made available to black

employees seeking betterment (A. ); (6) a special racial

grievance procedure to be established (A. ); (7) cutbacks

and layoffs to be governed by plant seniority for six months

). The same Order provided for individual relief to

the plaintiffs and set a hearing for determination of amounts due

them and of'attorneys' fees (A. ). Following a hearing

devoted to evidence on back pay due the individual plaintiffs

and attorneys' fees for their attorneys, the Court on June 3,

1975 entered an Order fixing the amounts due to the named plain-

8/

tiffs and their attorneys (A. ).

Both' Avco and the Union have appealed from all the findings

and orders entered against them (A. , , )• Defen

dants' position before this Court is apparently that they never

committed any actionable discrimination against any black

employee.

w The Court awarded Newman back pay in the amount of $7,822.52,

Alexander $6,876.62, and Dennis $6,246.32. Of plaintiffs

attorneys, Mr. Williams was awarded $81,000, Mr. Ennix $15,00 ,

and Mr. Bailer $1,000. By a supplemental Order filed June 20,

1975, the Court also awarded $4,500 to Mr. Robinson and denied

other requested attorneys' fees (A. ).

- 6 -

9/Statement of Facts

A . The Historical Framework of Discrimination

Before the effective date of Title VII, July 2, 1965,

both Avco and Aero Lodge No. 735 were dedicated to the ideal of

total segregation of employees. In an area with a 14.7% black

10/

workforce (A. ), Avco in 1961 had only 1.3% black employees

11/(A. ). By 1965 its workforce was still only 3.6% black (id_. ) .

Traditionally these few blacks were allowed to serve only as

janitors, porters, and charwomen (id.). Avco candidly recognized

in a 1961 "Self Analysis Form (Plans for Progress)" that it had

no black foremen, no black skilled or semi-skilled employees, and

11/no black administrative employees (A. ). The first

exception to this pattern of rigid exclusion came in 1962 after

a group of black employees, including plaintiffs Alexander and

Newman, filed a complaint of discrimination with the Committee on

Equal Employment Opportunity of President John F. Kennedy (A. ).

1/ Appellees are constrained to set out a detailed Statement of

Facts because, in their view, neither appellant has complied with

the admonition of Rule 28 (a), f .R.A.P. , that it fully and fairly

state the pertinent facts of record.

10/ The figures are based on U. S. Census Bureau 1970 data. The

population of the Nashville labor area is approximately 17%-18%

black (A . ) .

11/ Avco employed only two black "charwomen" before 1965; after

their departure it employed no black women at all until 1967; as

late as October 1968, its workforce was 0.04% black female (A. ).

12/ When asked to explain Avco's pre-1965 hiring practices, the

official in charge of hiring during that period responded, "We

just didn't [hire blacks]. There weren't many companies in town

that did hire a great number of blacks during that period of time"

(Tr. 887).

-7-

Avco thereafter promoted a token few blacks to the most dangerous

and nerve-wracking of its formerly white jobs (A. ). The

totality of Avco1s job segregation was complemented by the

13/

totality of its segregation of personal facilities.

Aero Lodge No. 735 demonstrated similar commitment to

apartheid. It rigorously excluded blacks from membership until

14/

1957 (A. ). Thereafter it accepted a token few black members

(and their dues) but required them to sweep out the union hall,

discouraged their attendance at union meetings, and barred them

from participating in picket lines (id_. ) . The District Coxirt.

found that, "The union acquiesced in and encouraged segregation

... at Avco. Union leadership felt that it was proper and not

wrongful discrimination to hire blacks only as janitors and

laborers" (A. ), and that the union either refused to process

or arranged to lose grievances by black members complaining about

15/

racial exclusion by Avco (A. ).

H 7 ~ The District Court found (A. ):

Avco did not permit black employees to eat with

the white employees. Also, Avco maintained

segregated toilet facilities and segregated water

fountains. As a matter of practice, blacks were

required to step aside and yield to white employees

when the employees were lined up for whatever

reason, such as to punch the time clock.

14/ The single exception was deemed "a curiosity and a showpiece"

(A. ) .

15/ Avco, for its part in this tidy arrangement (which this Court

has characterized as an alleged "long-standing conspiracy," see

451 F.2d at 747), discouraged blacks from seeking union membership

and advised them that "it was to their interest not to so join"

(A. ) — an injunction which, in the racial atmosphere of the

time, must have been full of foreboding.

- 8 -

*

With this bleak background in mind, we turn to a description

of defendants 1 pertinent employment practices during the period

most relevant to this action — July 2, 1965 to the time of trial.

B. Structure and Nature of Employment Opportunities at Avco

Since 1965

1. Avco1s operations and jobs

Defendant Avco's Nashville facility is primarily devoted

to aircraft parts manufacturing and assembly (Tr. 922-3). At

pertinent times in the recent past, Avco has also manufactured

appliances and furniture on contract for brand-name distributors

(Tr. 915-7). Most aircraft-related jobs require some degree of

skill and/or experience; applicance-related jobs are mostly

unskilled (Tr. 917-22, 927-8, 986-8). Total employment at Avco

has fluctuated widely, owing to the nature of government or

private sub-contract work on aircraft projects (A. );

total employment rose from 2335 iiJ*. 1966 to 3391 in 1970 (A. );

1§/

thereafter it declined markedly (Tr. 142).

Job classifications at Avco are grouped into departments

and occupations. Departmental lines, which prior to 1968 had

great significance for employee movement and job opportunities,

are no longer of primary importance (see p. 12, infra). At trial,

great attention was centered on the maintenance department, which

is responsible for preventive and plant maintenance, repairs, and

n 7" Post-decree reports by Avco show that this decline has

continued. Only 1509 persons were employed as of November 15,

1975. Report of Avco Corporation filed November 19, 1975,

U. S. District Court, M.D. Tenn., Nos. 4338, 5258.

-9-

custodial services, and contains a large number of high-paying

and coveted craft jobs (A. ). Occupations consist of

several related job classifications such as "A", "B", and "C"

17/categories in a particular craft or operator position, or

journeyman and helper/trainee in such a position (A. ).

Many occupations are found in different departments or throughout

the plant. The basic aircraft-manufacturing occupation, known

as "assembler-bench and jig," has the largest number of employees

in the plant (nearly half the total), appears throughout the

aircraft side of the operation, and is subject to special seniority

transfer, and layoff provisions (A. /A. , Tr. 901, 928,

954, 981-2). This occupation was a focus of trial testimony. In

1971, defendants' collective bargaining agreement abolished the

"B" and "C" classifications of all occupations and substituted a

system of varying pay levels within each occupation, with auto

matic progression through the pay levels over time (Tr. 1014-15,

w . . .PX 5, p.85). Occupations and classifications carry pay rates

keyed to an hourly wage rate system of labor grades from 11 (the

lowest) to 1 (the highest) (A. , A. ). certain tradi

tionally black positions such as janitor are not in the labor

grade system and pay less than grade 11 rates (A. , , ).

Many jobs' pay rates vary according to individual or group

production output under an "incentive" system; these jobs

Xz7~ These initials refer to skill and pay levels; progression

is from "C" to "A".

18/ That contract also grouped occupations into related job

families. This concept is not pertinent to the issues now on

appeal. See PX 5, pp.87-97, Tr. 1016-18.

- 10 -

generally include many of the higher paying occupations and

their rates vary according to a formula that assures extra pay

above comparable non-incentive jobs for employees who perform

at an average level (see A. , ).

2. The structure of job opportunities

The formal conditions and opportunities for employee

movement between occupations and departments have changed twice

in recent years. At all times, any job change— promotion,

transfer, bump-back, or recall— is subject to determination of

an employee's qualifications and ability to perform the job he

seeks to obtain. Qualifications are initially determined by

management, subject to challenge under the grievance procedure

established by the collective bargaining agreements (Tr. 961,

979-80). Prior to 1968, Avco entrusted its virtually all-white

and frequently bigoted (see A. ) supervisory personnel with

full authority to make these determinations (which higher

management did not question or review) according to subjective

standards and without guidelines (Tr. 961-2, 966-7, A. ).

Since 1968, the Avco personnel department has assumed responsi

bility for determining qualifications, but supervisory personnel

in other departments still play a considerable role in this

process (Tr. 961, 967, A. , A. ).

Subject to the determination of qualifications, job

opportunities at Avco depend on seniority rights defined in

defendants' collective bargaining agreements. The District Court

succinctly but accurately summarized the changes in seniority

and related procedures since 1965 (A. ). Until 1968, Avco and

- 11-

Lodge 735 maintained a "strictly departmental" seniority system

except for the assembler—bench and jig occupation, which in

effect formed a separate department company-wide (A. , see A.

, Tr. 882-3, Tr. 906, Tr. 1253-56). Under this system,

employees within a department had absolute priority for promotion

to vacancies in the department ahead of all other employees

(A. , A. , A. ). Recall of laid off employees also

followed departmental lines (A. ). In layoff situations

employees could bump back only within their department or to

another department in which they had previously worked (A. ,

Tr. 1255-56). There was no system of posting or bidding on vacan

cies; rather, departmental supervisors hand picked employees,

19/

supposedly in accordance with the seniority rules (A. ).

The 1968 collective bargaining agreement fundamentally

altered these procedures. It established a bidding procedure for

vacancies and required that the successful bidder be chosen on

the basis of plant seniority (Tr. 959-962). An employee could

submit up to three bids at a time, valid for one year, by filing

a job request card for each bid (Tr. 959, A. , A. ) .

Avco would post jobs for plant-wide bidding only if no qualified

bidder had a job request card on file (A. ). The successful

bidder was chosen according to plant seniority within his occupa

tion and classification (A. ). Occupation seniority rather

than department seniority also governed retention of jobs during

w ~ An employee could request consideration for a job by filing

an "AVO" (avoid verbal orders) preference card. Such request did

not, however, entitle him to priority (Tr. 1254).

- 12 -

reduction in force, bumping, and recall (A. ). The pro

cedure for determining qualifications under the bid system

included extensive use of employment tests. Avco's top personnel

officials agreed that blacks fared less well than whites on these

tests and that the tests were non-job-related, were never vali

dated, and were abandoned in about 1970 (Tr. 962-65, A. ,

19a/

, ). The 1971 collective bargaining agreement

modified the 1968 bid system by allowing submission of up to six

bids and substituting other ill-defined "selection criteria" for

testing requirements (A. ).

Under all the procedures in effect since 1965, defendants

recognized the absolute priority of employees holding "job equity"

rights to vacancies in those jobs (A. , , , Tr. 1124).

Job equity is simp]y prior service in a particular occupation

and classification (Tr. 1124). Thus, in recall situations, an

employee with job equity would always be recalled before a more

senior employee who lacked such equity, and job equity gave its

possessor substantial right to transfer or bump into another job

if displaced from his own.

C. Discrimination In Job Opportunities

The procedures described above lend themselves to abuse

along racial lines and were so abused by defendants.

Statistical summaries of black and white employment at

Avco bear witness to the devastating effects of defendants'

discrimination. On February 11, 1966, job segregation within

the hourly-rated jobs was almost total — with whites holding all

the better jobs. Not a single black employee held a position in

19a/ uSe of these tests was unlawful, see Griggs v. Duke Power Co

401 U.S. 424 (1971), Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. ,

45 L.Ed.2d 280 (1975).

-13-

any of the top four labor grades which were occupied by 397

whites (A. )• Over a third of blacks (33.9%) held jobs at

grade 11 or lower; only 3.6% of whites were in those categories

). Only 5.3% of black employees worked in grade 5 or

higher jobs, compared to 58.2% of whites (A. )• BY JulY 9'

1971, this disparity, while lessened, was still clearly evident.

Of workers in the top two labor grades, 258 were white and none

were black; 702 whites and only 26 blacks worked in the top four

grades; while the lowest three grades had as many blacks as

whites (39 vs. 40) (A. ). Of white employees, 77.5% were in

grades 5 or higher, compared to only 49.7% of blacks; 25.2% of

blacks fell into grades 7 or lower, compared to only 5.5% of

whites (A. ). At the time of trial, June 26, 1972, the same

disparities were still clearly apparent (see A. - ). For

example, Avco still had never employed a single black mechanic

(A. ) .

Statistical evidence of the continuing exclusion of blacks

from salaried jobs is equally clear. As late as July 9, 1971,

blacks held only 9 of 734 salaried positions — 4 of 463 exempt

jobs and 5 of 271 non-exempt positions (A. , A. ). This

pattern cannot be explained as a simple residue of past discrimi

nation. The data indicates that after October 27, 1969 and

before April 21, 1972, Avco added 268 new white salaried employees

but only 9 new blacks (A. ).

Disparities in average pay reflect thepattern of contin

uing job segregation. For calendar year 1970, white employees

20/ The earnings data for this year were selected for study as a

representative year of full employment.

-14-

consistently and dramatically out-earned their black contempo

raries in seniority terms (see A. ). Of 16 seniority-year

groups for which comparisons were possible, whites averaged higher

earnings in 15 (A. ); in 13 of these 15 cases,.the disparity

was 10% or more of the average black income and in 6 cases 20%

or more (hd.) . These figures translate to an earnings loss, for

this year alone, of hundreds or even several thousand dollars for

each black employee (id.). And even these figures do not account

for economic loss suffered by reason of Avco's refusal to promote

blacks to supervisory positions since only hourly-paid employees'

incomes were compared.

None of these striking racial disparities can be explained

by an objectively measurable difference in qualifications. A com

parison of average educational attainments for white and black

workers hired between 1952 and 1970 shows that blacks had, on

the average., more years of school (A. ). Blacks averaged

11.42 years of school, compared to 10.67 years for whites (id.) .

The district judge correctly identified a variety of

discriminatory employment practices as the root cause of the

21/

racially-tainted picture painted by the statistics. His findings

were compelled by a record showing numerous instances of dis

crimination by and against particular individuals, making out a

strong pattern of overall discrimination.

21/ The defendant union would have this Court disregard these

statistical indicia of discrimination (U.Br. 39-41). The Court's

practice, however, is to accord statistical proof considerable

weight in employment discrimination cases. United States v.

Masonry Contractors Assn, of Memphis, Inc., 497 F.2d 871, 875

(6th Cir. 1974).

-15-

The District Court found (A. ):

From July 2, 1965 to 1968, black employees at

Avco were subjected to discriminatory treatment by

Avco. It was only through rumors and informal word

of mouth that black employees could learn of job

openings, while Avco supervision regularly’informed

white employees of openings. As is obvious, black

employees were competing with white employees for

those jobs. It is pertinent that Avco foremen and

supervisory personnel, almost all white, ascertained

that white employees had qualifications which did not

appear on company records. However, these same fore

men and supervisory personnel considered black appli

cants solely on what was listed on their applications.

Some of these applications had been on file for many

years.

Avco supervisory personnel stated that they could

not give informal on-the-job training to non-qualified

employees. However, Avco supervisory personnel did

give this type of informal training to white employees.

Whites with less seniority than blacks were promoted

to maintenance jobs even though some of those promoted

were no more qualified than the blacks ....

As a requirement of the collective bargaining

contract effective August 12, 1968, an Avco official

in the personnel Office, industrial Relations Depart

ment, began to interview all applicants for promotion.

In some instances the applicants were given tests.

However, in many instances, significant reliance was

still placed on the evaluations of Avco foremen,

assistant superintendents, and superintendents. These

supervisory personnel insisted that there was no racial

bias in their evaluations; however, the majority of

these individuals thought the segregation practiced at

Avco was not racial discrimination. Despite grievances

and complaints alleging racial discrimination, both in

on-the-job training and in promotions, Avco did not

make an inquiry into whether or not the subjective

evaluations of the black employees by the white Avco

supervisory personnel were affected by racial bias.

Avco is bound by the knowledge and actions of its

supervisory personnel. These Avco personnel both knew

of and participated in practices, policies and condi

tions of racial discrimination. Numerous oral and

written complaints about the racial discrimination at

the plant were made to Avco officials and supervisory

personnel. However, the Avco officials and supervisory

personnel generally took no effective affirmative

action, either before or after the effective date of

Title VII, to correct valid complaints of discriminatory

treatment.

- 16-

The key to the discrimination that infected this system

was Avco's supervisory and managerial personnel. The first

black supervisor at. any level was not appointed until about 1965

(A. ; Tr. 56-7). The lower-level supervisors— foremen and

assistant foremen— remained nearly all white thereafter, and by

1972 none of the 12-14 superintendents had ever been a black

2 2/

(A. , ). Even while testifying at trial in 1972,

these white supervisors exhibited attitudes of surprising racial

23/

insensitivity (to say the least).

Avco's white supervisors made certain that black employees

could not be hired or transferred to better-paid and higher-

skilled jobs. The 1968 rejection of Glenn Beard, a highly quali-

24/

fied black electrician, is illustrative. The ordeal that Avco

forced on Charles Haddox, a black industrial plumber who got a

22/ There was credible testimony that Avco reached its "high

point" of perhaps six black foremen at a time (A. ) in prep

aration for a contreict compliance inspection visit by civil right

officials on the Lockheed project; thereafter, the black foremen

were returned to hourly ranks (Tr. 745-748).

23/ For example: Avco's maintenance superintendent denied that

pre-1965 practices were racially discriminatory; he felt them

fair because they allegedly provided for "separate but equal"

conditions (Tr. 1136-38). See also supervisors' testimony appear

ing at Tr. 1377-8, Tr. 1438-39. The district judge made addi

tional pertinent findings about overt supervisory prejudice

toward blacks, see A.

24/ Mr. Beard, a high school graduate with three years' further

training plus Navy experience in electronics and electricity (Tr.

175-78, 180-82, 193-201), who had been hired as a laborer in 1954

and in 1959 (Tr. 176-8), was refused a maintenance electrician

job in 1968. After first trying unsuccessfully to screen him out

by testing, Avco simply pronounced him unqualified (Tr. 180-186).

Meanwhile, Avco continued to hire whites off the street (Tr. 186-

187). (Mr. Beard subsequently demonstrated his qualifications

by becoming an aircraft mechanic, Tr. 187-88.)

-17-

plumbing job in 1967 only after three years of trying and several

25/

grievances, provides another example. Leon McClain, a black

man with a strong mechanical background, was able to get a job

in 1966 only because of the intervention of a white woman whose

26/

black maid was McClain's mother-in-law. The record shows that

many whites of inferior qualifications were hired and where

necessary trained in maintenance and other desirable jobs, as

27/

the District Court found (Op. p.19). One non-black master

craftsman candidly testified that, in his 20 years at Avco,

management had continually told him that blacks did not have the

ability to be craft workers and that there was "no way under the

sun" for a black to get such a job (Tr. 298-99).

The evidence also showed a wide variety of discriminatory

practices relcited to job assignments and working conditions.

26/ Mr. Haddox, despite extensive plumbing experience which he

described in applying to Avco, was hired as a laborer in 1964

(Tr. 205-07, 209-210). He then applied for promotion to plumber

but was bypassed by two whites, one of whom had "kinfolks" at

Avco (Tr. 212-216). Only after pursuing his grievances tenaciously

did he convince Avco to find him "qualified" — and even then was

placed in an inferior "C" category created especially for his

occupancy (Tr. 217-224). He too is now a satisfactory "A" plumber

(Tr. 224).

26/ See Tr. 726-733. When Mr. McClain first applied to Avco in

1953, he was told that only a "housekeeping" job was available

(for blacks), and rejected it (Tr. 727-28). After he was finally

hired as an assembler trainee, McClain proved more educated, more

experienced, and faster to learn than most of the white employees

(Tr. 733-35).

27/ The bulk of the testimony on this point concerned maintenance

department craft jobs. There, the pattern was to pass over black

incumbents working as janitors, laborers, or general helpers, many

of whom had mechanical experience and sought promotion, to bring

in whites from other departments or off the street, often as "C"

or trainee mechanics. See Tr. 1171-1237, Tr. 300-306. Compare,

e.g., the qualifications of successful white applicants and bidders

with those of blacks as cited in nn. 24, 25, 26, supra.

- 18 -

This evidence supplements the strong evidence presented on the

28/

individual claims of Newman, Alexander, Dennis, and McCreary,

which the District Court after elaborate trial on these issues

believed and found as true (A. ), and the individual

histories of discrimination referred to elsewhere in this section.

For example, one witness testified that the better jobs were

posted so as to attract primarily white applicants (Tr. 751);

that blacks continue to be promoted with difficulty and into less

desirable positions (Tr. 748, 752); that blacks receive the most

unpleasant positions where whites do not wish to work (Tr. 755);

that supervisors continue to abuse blacks with racial epithets

(Tr. 756). The record is replete with corroborating testimony

as to such problems.

D . The Globe-Wernlcke Incident

Late in 1971, while Avco's aircraft workforce in the

assembler-bench and jig classification was expanding, its opera

tion of a furniture manufacturing line for the Globe-Wernicke

2 9/

Company was ended (Tr. 1027-28, 2072). Under the collective

bargaining agreement's provisions (PX 5, p.53), the laid off

Globe-Wernicke employees had no contractual right to recall in

the assembler-bench and jig occupation. This was because recall

rights could only be exercised in occupations for which the laid

28/ See pp. 56-64 , infra.

29/ It was not unusual for Avco to be laying off employees in

some areas while hiring in others (Tr. 2078, 2025). Indeed,

this was one reason for adoption of the general recall provisions

of collective bargaining agreements between defendants (see A.

; A . ) .

-19-

off employee was qualified (id_.) and, as every witness who

testified on this subject admitted, the Globe-Wernicke employees

were not qualified and had no prior experience in aircraft work

(Tr. 1028-29; Tr. 2027-28). The District Court so'found (A. ).

Nevertheless, the union pressured Avco to recall these employees

under the inapplicable general recall provisions of the union

contract (Tr. 1032, Tr. 2084). That provision could only become

operative after the laid off employees had become qualified

through training on the bench and jig job, and Avco was under no

contractual obligation to provide them with such training (Tr.

30/

1033, Tr. 2073). Nevertheless, defendants concluded an ad-hoc

deal after the layoff had occurred, by which laid off employees

would train without pay and then be recalled to the bench and jig

classification with their full seniority (Tr. 2066-67, 1029-30).

All 73 Globe-Wernicke employees thus "recalled" were white and

of long seniority (A. , Tr. 1776-77, Tr. 1026).

The assembler-bench and jig occupation was, by Avco's

standards, heavily black (177 of 898 employees), and most of the

31/

black employees in it had very little seniority (A. ). The

effect of placing long-term whites into the occupation under

Avco's system of layoff by plant seniority within the occupation

-12/ Although both Avco and Aero Lodge No. 735 now make the

imaginative argument that Avco was required by law to train and

recall the Globe-Wernicke employees, the record is contrary.

Avco's own Manager of Personnel and the IAM Business Representa

tive for Lodge 735 both testified flatly that the laid off

employees had no recall rights and Avco had no training responsi

bility under the contract. See Tr. 1033, Tr. 2073.

31/ Most of Avco's hiring of blacks after 1965 was into this low

level occupation. This "loading up" of blacks was clearly one

result of the Alexander suit. See Tr. 981-82, 1031; A.

- 2 0 -

was to doom junior blacks to elimination when one of the

32/

predictable downturns in aircraft work occurred. Avco's

Personnel Manager conceded that the foreseeable effect of the

recall would be the elimination of many black employees "somewhere

down the road" (Tr. 1033) and explained how, under the contract,

the displacement of these blacks could be required once the

Globe-Wernicke whites had entered the same occupation (Tr. 1030).

Ttfo to three months after the "recall," in early 1972

(A. ), a cutback occurred in aircraft work and 124 employees—

52 of them blacks— lost their jobs (A. ). Avco concedes and

the court found that, but for the Globe-Wernicke whites' recall,

these blacks would have retained their jobs (A. ). This

reduction in force eliminated 29% of the 177 black bench and jig

employees, but only 10% of the 721 white employees; moreover, at

that time nearly two-thirds of Avco's entire black workforce

worked in that occupation and the layoff eliminated nearly one-

fifth of that force (A. , A. ). The court below concluded

that;

The sum and substance of [defendants'] joint

action was to state that white employees are

entitled to preference over black employees

in the areas of job classification, working

conditions, transfers, compensation and

termination (A. ) .

See A. ; and see p. 9, supra. There was sharply

disputed evidence as to whether defendants had, at the time of

the Globe-Wernicke recall, specifically projected a layoff in

the bench and jig occupation in the near future; the weight of

evidence was that they had (PX 51, Tr. 2050), and the District

Court so found (A. ) .

- 21 -

E. The Individual claims of Alexander, Newman and Dennis

The individual claims of plaintiffs Ramsey Alexander,

Robert Newman, and R. L. Dennis were exhaustively tried and

carefully decided below on a specific factual basis (see A.

33/

). The District Court entered detailed findings of specific

facts in support of its conclusion that all three plaintiffs

had been victims of many-faceted discrimination directed against

them as individuals, as well as in their status as class members.

While we defer discussion of the factual record supporting theIVcourt's determinations to the argument section of this brief,

a few general observations are pertinent here.

Alexander, Newman, and Dennis were among the most active

and aggressive of a small group of black employees who courage

ously fought defendants' racism. Rather than standing quietly

by to wait for times to change, they made the times change.

The class and indeed the defendants owe much to their determina

tion to bring Avco's operations into some semblance of compliance

with law. Alexander and Newman were among the five signers of

the original complaint of discrimination to the President's

Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity in 1962 (Tr. 26, 42,

Tr. 352-53, 383). Within 100 days after Title VII became effective,

Alexander filed his EEOC charge initiating the process that has

led here (Tr. 27-28, A. ). Newman filed his EEOC charge in

W ~ Also fully treated below, but not briefed here because not

appealed, was the discriminatory discharge claim of plaintiff

McCreary, see A.

34/ See pp. 55-66 , infra.

- 22 -

May, 1966, within days after denial of his discharge grievance

by the arbitrator (A. , Tr. 383). Dennis, who was hired

after Newman's discharge (Tr. 459), became one of the first,

black local union committeemen (Tr. 461), and made it his par-

concern to defend the rights of black union members (Tj. .

478, A. ). Dennis was an organizer and principal staff member

of a blade employees' self-help organization formed in 1970 and

known as the "Cause-Find-Commission" (Tr. 480, A. , Tr. 233-36).

Virtually every halting step taken by defendants in the

direction of racially fair employment practices can be traced to

the complaints of black employees, led by Alexander, Newman, and

Dennis (A. ). The 1962 charge resulted in the plant's desegre

gation of physical facilities and a beginning of token desegrega

tion of job opportunities (Tr. 42, 134, 352-53, A. ). The

1965-1966 EEOC charges and filing of suit resulted in the first

progress toward opening the door to black job opportunities more

than a tiny crack (Tr. 27—8, 137) . While concedl.ng as little

equality as they thought they could get away with, defendants

also established a pattern of harassment and retaliation against

those black leaders who forced their waiting game. The events

giving rise to the three named plaintiffs' claims are the clearest

possible evidence of this pattern. See pp. 56-64 , infra; see

also Tr. 238, Tr. 230-31. Those claims must be evaluated in

light of these general observations.

-23-

ARGUMENT

Introduction

The appeal of this employment discrimination case brings

this Court face to face with a shocking and comprehensive scheme

of racial oppression. The District Court recognized appellants’

practices for what they are and granted appellees their remedy.

Yet the Company's appeal brief repeatedly attacks the district

judge's integrity and judicial temperament, implying that he was

thoroughly befuddled and so blinded by his allegedly erroneous

view of the ■. Globe-Wernicke incident as to be incapable of impar-

35/

tially evaluating the evidence. Nothing could be farther from

the truth, as Judge Morton's careful, detailed Memorandum opinion

and subsequent orders prove. By representing the court's opinion

as the product of injudicious reasoning provoked by a misreading

of a single, small part of the record, Avco apparently hopes to

357“ Avco asserts that the Globe-Wern.icke incident became, "in

the Court's mind, the dominant issue in the case to which all

other issues were now subordinate" (Co. Br. 6); that the Court

resolved "all factual issues in plaintiffs' favor ... because

Avco's credibility had been destroyed by the Globe-WTernicke inci

dent" (id. 7-3); that the district judge "had a closed mind" (id.

11); that the "central and determinative issue in this case is

the correctness of the holding of the District Judge in connection

with the so-called Globe-Wernicke incident which ... resulted in

the decision of other disputed issues in favor of plaintiffs" (id.

22); that "the Globe-Wernicke findings are the crucial premise for

all of the adverse findings and conclusions from which Avco appeals"

(id. 29); that the findings on the individual claims "were so

clearly devoid of evidentiary basis as to compel the inference

that the issues were prejudged by the District Judge" (icl. 45).

The simplest refutation of these charges is a reading of the

district judge's opinion (A. - ). Its care, detail, and

bailance— and the relatively minor part devoted to the Globe-

Wernicke incident— thoroughly belie Avco's allegations.

-24-

divert attention from the massive proof of systemic discrimination

that permeates this record.

Appellants would have this Court "see no evil" in their

racial policies and vacate every element of relief granted below7.

An appellate position more stubbornly defiant of the strong

national policy expressed by Congress's enactment of Title VII

or more intractably hostile to the thrust of its interpretation

by the federal courts is difficult to imagine. To adopt appel

lants' position, the Court would have to blind itself to a history

of severe discrimination preceding, surrounding, and finally

36/

dwarfing the Globe-Wernicke episode, as massively documented in

the record (see pp. 19-21 , supra) and carefully found by the

District Court (see pp. 4, 21, supra). This Court must reject

appellants 1 invitation to reverse, not only to do justice in this

case, but also to remind such defendants as these that this nation

turned an historic corner in 1964 and will never turn back.

I. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ERR IN ALLOWING

THIS CASE TO PROCEED AS A CLASS ACTION FOR

REDRESS OF CLASS-WIDE DISCRIMINATION.

A . This Case Is Maintainable As A Rule 23(b)(2) Class Action

For The Relief Plaintiffs Seek.

There can no longer be any question that the federal courts

are authorized, and indeed encouraged, to permit class action

treatment of Title VII employment discrimination claims, including

claims for class-wide back pay. See Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

H T The Globe-Wernicke incident is properly viewed as only a par

ticularly egregious example of appellants' racial policies in

action — but essentially of a piece with the larger record of

discrimination. This was the lower court's perspective.

-25-

422 U.S. ___ , 45 L.Ed.2d 280, 294, n.8 (1975); Bowe v. Colgate-

Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711, 719-720 (7th Cir. 1969); Pettway v.

American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 256-7 (5th Cir. 1974);

Johnson v, Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364, 1375 (5th

Cir. 1974). This Circuit has repeatedly approved class back pay

awards, Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870, 876 (6th

Cir. 1973); Meadows v. Ford Motor Co., 510 F.2d 939, 948 (6th Cir.

1974) ; EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co. , 515 F.2d 301, 314-5 (6th Cir.

37/

1975) . The fact that individual back pay is sought as one element

of the equitable remedy for class members does not preclude class

38/

action treatment under Rule 23(b)(2). Robinson v. LoriHard

Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 801-2 (4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404

U.S. 1006 (1971); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d

398, 422 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied 419 U.S. 1050 (1974), cert.

granted on other issue 420 U.S. 989 (1974); United States and Ford

v. United States Steel Corp., 520 F.2d 1043, 1057 (5th Cir. 1975).

nr In Detroit Edison, this Court stated:

We recognize that every Title VII action is in effect

a class action and that a liberal construction should

be given to the requirements of Rule 23(a)(2) and (3)

.... It is recognized that one purpose of Title VII

is to root out an underlying policy of discrimination

of an employer or a union regardless of how it is mani

fested. 515 F.2d at 311.

38/ As the Advisory Committee Note to the 1966 amendment of Rule

"23 (b) (2) states :

The subdivision does not extend to cases in which the

appropriate final relief relates exclusively or pre

dominately to money damages. 39 F.R.D. 69, 102 (1966)

(emphasis supplied)

But the courts have uniformly held, as illustrated by the above-

cited decisions, that back pay is incidental to other equitable

relief, so that Title VII cases are not "exclusively or predomi

nately" for "damages."

- 26 -

Appellants cannot and do not seriously dispute any of the

foregoing authorities. Rather, they seek to avoid the clear

meaning of Albemarle Paper Co. and the other cases cited by

opining that this very typical Title VII back pay case is proced-

urally different from all others because the class determination

and notice to class members was not ordered until the court below

decided the case on the merits. Because this argument must

39/

clearly fail under the law' governing 23(b)(2) actions, Avco

proposes that all class actions for back pay must be deemed Rule

23(b)(3) actions (Co. Br. 40-42). This contention ignores the

text of the Rule, the Advisory Committee Note to the Rule and all

pertinent authorities.

There is no support for the assertion that a back pay claim

renders a case ipso facto a Rule 23(b)(3) class action. On the

contrary, Rule 23(b)(2) and its Note specify that the dispositive

factor is whether

the party opposing the relief has acted or refused to

act on grounds generally applicable to the class,

thereby making appropriate final injunctive relief or

corresponding declaratory relief with respect to the

class as a w’hole.

Race and color are, of course, such "grounds generally applicable

40/

to the class." The court below specifically found that this case

met the (b)(2) requirement (A. ), and appellants did not— and

could not— directly attack this finding. The instant case cannot

H 7 ~ See Part B, pp. 28-36, infra.

40/ Hall v. Werthan Bag Co., 251 F. Supp. 184, 186 (iVLD.Tenn. 1966);

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28, 34 (5th Cir. 1968); Qatis

v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir. 1968).

-27-

plausibly be likened to a class action of the type denominated

"spurious" before the 1966 amendments to Rule 23; the class is

not fundamentally heterogeneous and joinable solely for conven

ience (cf. Co. Br. 41-43). This Court must reject the sweeping

— 41/

principle suggested by Avco as without legal foundation and

again squarely hold back pay available in an appropriate Rule 23

(b)(2) case.

B. The Timing of Class Certification and Notice in This Case

Does Not Preclude Class Action Treatment.

Appellants' main argument against the class action centers

on the timing of the District court's formal order of certifica-

42/

tion and its order providing for notice to class members. Appel

lants urge that the class action must be dismissed because the

court failed to comply with the admonition of Rule 23(c)(1) that

class actions be determined "as soon as practicable" and with the

43/

notice requirement of Rule 23(c)(2) (Co. Br. 37-44, U.Br. 44-46).

HZ' The one appellate court which has specifically considered the

same argument held that, where an action is maintainable under

either (b)(2) or (b)(3), the (b)(2) vehicle should be chosen as

superior. Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., 508 F.2d 239,

252-253 (3rd Cir. 1975), cert.~denied 421 U.S. 1011 (1975).

As to the argument that fairness requires (b)(3) type notice

before adjudication of individual back pay claims, see p. 30, n.46,

infra.

42/ Both the District Court and this Court plainly stated early in

these proceedings that the case would be a class action, see p. 2,

supra. A formal class action certification pursuant to plaintiffs'

pre-trial motion (A. ), was not issued until the decision on the

merits, however (A. ). The court directed individual notice to

class members on plaintiffs' motion (A. ) in its February 11,

1975 order (A. ) .

43/ The District Court's August 20, 1974 decision to dismiss the

class action (A. )— which it subsequently reconsidered and

reversed (A. )— was based entirely on its concern about lack of

- 28 -

The appellants' arguments are a melange of wishful thinking and

erroneous legal principles.

The obligation imposed by Rule 23(c)(1) to determine

whether a class action may be maintained "as soon as practicable"

rests on the court. "The language of this provision is mandatory

and the court has a duty to certify whether requested to do so or

not. 3B J. Moore, Federal Practice, ^ 23.50 at 23-1001," Garrett

v. City of Hamtramck, 503 F.2d 1236, 1234 (6th Cir. 1974); EEOC

v. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d 301, 310 (6th Cir. 1975). The

absence of an early certification is thus not ultimately attribut-

44/

able to any wrongdoing on the part of any party and does not

give any basis for dismissing the class action, as the Fifth Cir

cuit has held. Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F.2d

45/

40, 49-50 (5th Cir. 1974). Plaintiffs' failure to seek formal

certification here until June, 1972 is particularly understandable:

both the District Court in Alexander and this Court in Newman had

clearly announced at an early stage that the class actions could

go forward (see p. 2 , supra). In these circumstances, appellants

could be neither surprised nor prejudiced by the lateness of the

certification.

4 3/ (cont' d)

earlier notice to class members. The district judge made this

absolutely clear in colloquy at the hearing held January 17, 1975

on plaintiffs' motion to reinstate the class action (A. ).

44/ Indeed, the District Court shouldered the blame for the failure

to provide early certification and notice, at the January 17, 1975

hearing (see A. ).

45/ The Court of Appeals in Rodriquez held squarely:

A class action may not be dismissed because the class

representatives fail to ask for a ruling on the pro

priety of the class nature of the suit. That respon

sibility falls to the court. "The court has an

independent obligation to decide whether an action

- 29 -

Rule 23(c)(2) does not require any notice to class members

in a (b)(2) class action. The mandatory notice requirement of

subsection (c)(2) applies by its terms only to (b)(3) class

actions, as the Supreme Court has twice recognized. In Risen v.

Carlisle & Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156, 177 n.14 (1974), which closely

scrutinized the class action notice issue, the Court noted,

We are concerned here only with the notice requirements

of subdivision (c)(2), which are applicable to class

actions maintained under subdivision (b)(3). By its

terms subdivision (c)(2) is inapplicable to class

actions for injunctive or declaratory relief maintained

under subdivision (b)(2).

And in Sos na v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393, 397 n.4 (1975), the Court,

after finding that a (b)(2) action was contemplated, stated,

"Therefore, the problems associated with a Rule 23(b)(3) class

action, which were considered by this Court last Term in Eisen v.

Carlisle & Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156 (1974), are not present in this

46/

case."

45/ (cont'd)

brought on a class basis is to be maintained even if

neither of the parties moves for a ruling under sub

section (c) (1)." Wright & Miller, Federal Practice

and Procedure, Civil §1785 (1972).

505 F.2d at 50.

46/ The policy behind the different notice standards for (b) (2)

and (b)(3) actions was articulated in Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Ins.

Co., supra, 508 F.2d at 249:

Binding all members of a (b)(3) class, however, was

not thought by the Advisory Committee to be as fair

as binding all members of a (b)(2) class. By the

very nature of a heterogeneous (b)(3) class, there

would be many instances where a particular individual

would not want to be included as a member of the class.

'To respect these individual interests, Rule 23 (c) (2)

was-written to afford an opportunity to every potential

class member to opt out of the class. (emphasis supplied)

-30-

Notice in (b)(2) class actions like this one is given,

47/

if at all, pursuant to Rule 23(d) (2), which provides:

In the conduct of actions to which this rule

applies, the court may make appropriate orders

... requiring, for the protection of the

members of the class or otherwise for the fair

conduct of the action, that notice be given in

such manner as the Court may direct to some or

all of the members of any step of the action

.... (emphasis supplied)

The terms of subdivision (d)(2) are broad and flexible by design

of the rule's drafters. See Advisory Committee Note, 39 F.R.D.

69, 106 (1966). The notice given class members in this case must

be evaluated in light of this rule and its principal concern—

fairness to absent class members. ;

Appellants argue that due process requires the issuance of

notice to all class members in any Rule 23 class action. The

Supreme Court pointedly refused to adopt this sweeping principle

48/

in Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, supra. As Eisen recognized,

the due process principles expressed in Mullane v. Central Hanover

Bank & Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306 (1950), Ilansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S.

32 (1940), and related cases are satisfied by the mandatory

notice requirement of subdivision (c)(2) for (b)(3) class actions

plus the discretionary notice provision of subdivision (d)(2),

see 417 U.S. at 173-4. The Advisory Committee Note demonstrates

H 7 ~ We do not suggest that some form of notice at some stage is

necessarily inappropriate in (b)(2) actions. But we do maintain

that the more inflexible (c)(2) standards are inapplicable.

48/ At an earlier stage of the same case, the Second Circuit had

held that due process requires notice in all representative actions

391 F.2d 555, 564 (2nd Cir. 1968). But see Frost v. Weinberger,

515 F.2d 57, 65 (2nd Cir. 1975), discussed at p. 32, infra.

-31-

that the drafters of the rule were sensitive to due process con

siderations and believed the provisions of the rule consonant

with these considerations, 39 F.R.D. 69, 106-07 (1966). The

Advisory Committee noted that "In the degree there is cohesiveness

or unity in the class and the representation is effective, the

need for notice to the class will tend toward a minimum," 39 F.R.D.

at 106. This focus on practical aspects of the notice question

and the nature of the class involved assures fundamental fairness

and is consistent with proper due process analysis.

The most careful application of these principles in the

Title VII context is found in Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Ins. Co.,

508 F.2d 239 (3rd Cir. 1974), cert, denied 421 U.S. 1011 (1975).

The Third Circuit reasoned that the motivating force behind

Mullane and like cases was the heterogeneity of the class, making

it likely that some class members* interests would be prejudiced

unless they, received notice and an opportunity to opt out or to

appear individually, 508 F.2d at 255-7. But in a (b)(2) employ

ment discrimination action, due to the homogeneity of the class—

all of whom are victims of a common discrimination based on a

class characteristic (sex or race)— such early notice would "add

nothing, " _id. at 256-7. The court concluded that "notice to

absent members of a (b)(2) class is not an absolute requisite of

due process," id_. at 257. Two other circuits have, following

the Supreme Court's Eisen and Sosna footnotes, held that due

process does not require notice in all (b)(2) class actions. See,

49/

e.g., Frost v. Weinberger, 515 F.2d 57, 65 (2nd Cir. 1975);

The Second Circuit's decision in Frost is particularly signif

icant, since the court recognized therein that its earlier dicta

in Eisen, 391 F.2d at 564-5, are now untenable in light of Sosna.

-32-

, 44 U.S.L.W. 2175 (9th Cir.Elliot v. Weinberger, ___ F.2d