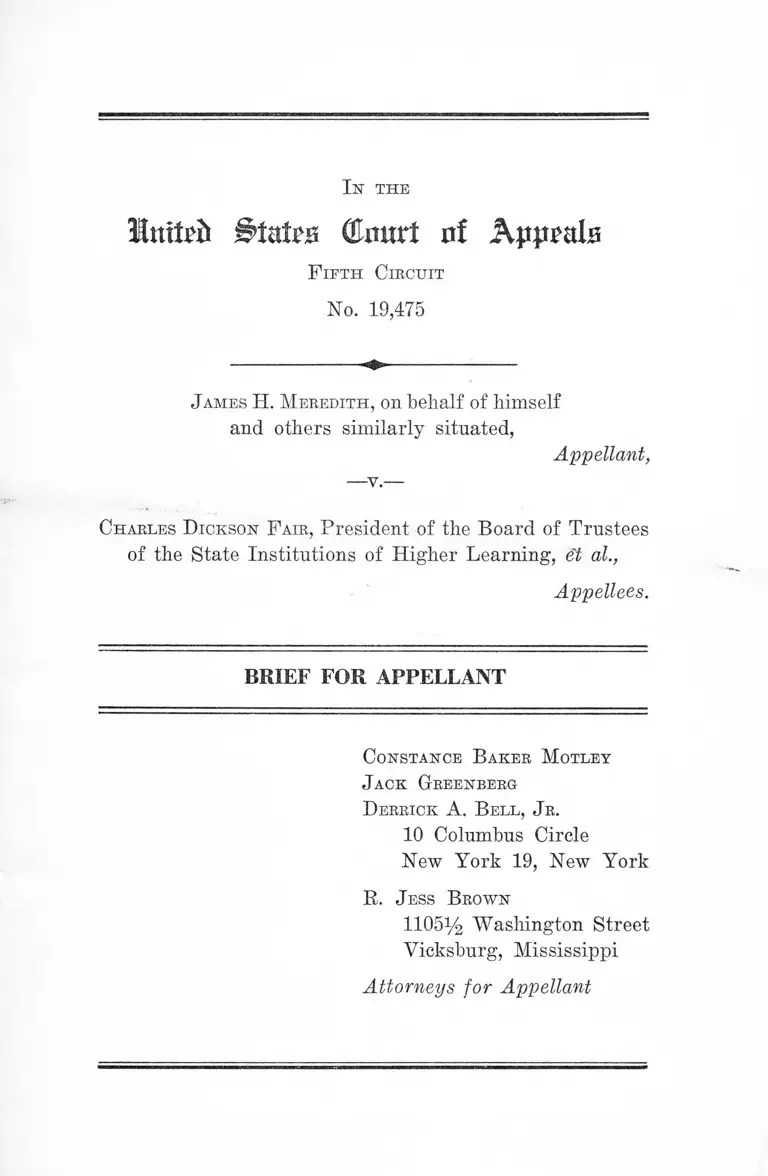

Meredith v. Fair Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Meredith v. Fair Brief for Appellant, 1962. f2548681-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b80f3014-cb77-4583-886a-bf30dff9f552/meredith-v-fair-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Intteft (Emtrt of Appeals

F ifth Circuit

No. 19,475

J ames H. Meredith, on behalf of himself

and others similarly situated,

A-ppellant,

Charles D ickson F air, President of the Board of Trustees

of the State Institutions of Higher Learning, <$t al.,

Appellees,

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Constance B aker Motley

J ack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R. J ess Brown

1105^2 Washington Street

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ........................................ ............. 1

Statement of the Facts .................................. ............... 6

1. Appellant’s Application ...................................... 6

2. Reasons for Denying Appellant’s Application

Prior to Trial ........................................................ 8

A. The University’s Policy Regarding Trans

fer Students From Non-Member Colleges

of Regional Accrediting Associations ....... 9

B. The University’s Policy Regarding Trans

fer of Credits From Non-Member Institu

tions of Regional Accrediting Associations 11

3. Reasons For Denying Appellant’s Admission

After Commencement of Suit ............................ 12

4. Mississippi’s Racial Policy Remains Un

changed ......... 17

Specification of Errors .... 23

A rgument................................................................................. 24

Appellant Has Been Denied Admission to the

University of Mississippi Solely Because of His

Race and Color and Pursuant to Rules and

Regulations and Other Criteria Applicable Only

to His Case ....................................... 24

A . Appellant’s Race Precluded His Admission

to the University by Reason of the Uni

versity’s Unchanged Racial Policy ........... 24

PAGE

B. The Rules and Other Criteria Used to Bar

Appellant’s Admission Were Applicable to

His Case Alone .................................................. 31

Conclusion................................................................................ 35

Table op Cases

Booker v. State of Tenn. Bd. of Education, 240 F. 2d

689 (6th Cir. 1957) ; cert. den. 353 U. S. 965 ........... 25

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ..5, 28

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) .............................. 29

Doremus v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 429, 434-435

(1952) ................................................................ ............ ....................................... 34

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202 (1958) .......................... 34

Frazier v. Board of Trustees Univ. of N. C., 134 F.

Supp. 589 (M. D. N. C. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 979 .... 25

G-ray v. Board of Trustees Univ. of Tenn., 342 U. S.

517 (1952) ......................................................................... 25

Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida, 347 U. S. 971

(1955); 350 U. S. 413 (1956); 355 U. S. 839 (1957);

162 F. Supp. 851 (N. D. Fla. 1958) .............................. 25

Holmes v. Danner, 191 F. Supp. 394 (M. D. Ga. 1961) .... 25

Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N. D. Ga. 1959) ..25, 34

Lucy v. Adams, 134 F. Supp. 235 (N. D. Ala. 1955),

aff’d 228 F. 2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955), cert. den. 351

U. S. 931. See also 350 U. S. 1 (1955) ........................... 25

ii

PAGE

I l l

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of L. S. U., 150 F. Supp.

900 (E. D. La. 1957), aff’d 252 F. 2d 372 (5th Cir.

1958), cert. den. 358 U. S. 819 ................................... 25

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 IT. S. 637 (1950) ....25, 29

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) 25

Parker v. University of Delaware, 31 Del. Ch. 381, 75

A. 2d 225 (Del. Ch. 1950) ....... ...... ........................ ....... 25

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936)

(Md.) .................'..................................................... ........... 25

Swanson v. University of Virginia, Civ. No. 30 (W. D.

Va. 1950). (Unreported) .............................................. 25

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) ...................... 25, 29

Tureaud v. Board of Supervisors of L. S. U., 116 F.

Supp. 248 (E. D. La. 1953) rev’d 207 F. 2d 807 (5th

Cir. 1953), vacated and remanded, 347 U. S. 971

(1954), on remand 225 F. 2d 434 (5th Cir. 1955),

on rehearing 228 F. 2d 895 (5th Cir. 1956), cert. den.

351 U. S. 924 ................................................................... 25

United States v. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303 (1946) ............... 33

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors of L. S. U., 92 F. Supp.

986 (E. D. La. 1950) aff’d 340 U. S. 909 ....................... 25

Wilson v. City of Paducah, Ky., 100 F. Supp. 116

(W. D. Ky. 1951) .......................................................... 25

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ................... 33

Other A uthorities

II Wigmore on Evidence, §437 (3d Ed. 1940) ............... 27

II Wigmore on Evidence, §1709 (3d Ed. 1940) ............. 33

PAGE

I n t h e

llxnUb Status (Enurt at Appeals

F ifth Circuit

No. 19,475

James H. Meredith, on behalf of himself

and others similarly situated,

Appellant,

Charles D ickson F air, President of the Board of Trustees

of the State Institutions of Higher Learning, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This ease involves racial segregation in Mississippi’s

institutions of higher learning.

The instant appeal is from a final judgment entered

February 5, 1962 after a full trial on the merits denying

appellant’s prayer for an injunction securing his admis

sion to the undergraduate school of the University of

Mississippi (R. Vol. Y, p. 732).

This action was originally instituted on May 31, 1961,

when appellant filed his complaint in the court below alleg

ing that the appellee Board of Trustees of State Institu

tions of Higher Learning of the State of Mississippi and

officials of the University, including the Registrar, have

2

pursued, and are presently pursuing, a state policy, state

practice, state custom and state usage of maintaining and

operating separate state institutions of higher learning for

the white and Negro citizens of Mississippi pursuant to

which appellant has been denied admission to the University

of Mississippi solely because of race and color (R. Yol. I,

p. 13). When the complaint was filed appellant sought a

temporary restraining order without notice designed to

secure his admission to the June 8, 1961 summer term of

the University. This application was denied and the case

set for a hearing on appellant’s motion for preliminary

injunction, also filed with a complaint, on June 12, 1961,

four days after commencement of the summer term.

The relief sought is, inter alia, an injunction enjoining

appellees from: a) refusing to act expeditiously on the

applications of appellant and members of his class for

admission to the University of Mississippi or any other

state institution of higher learning presently limited to

white students; b) refusing to expeditiously advise ap

pellant and members of his class of the status of their

applications for admission and of the requirements for

admission which they failed to meet; c) requiring appel

lant or any member of his class to furnish certificates from

alumni of the University of Mississippi; d) refusing to

admit appellant and members of his class to the University

of Mississippi or any other state institution of higher

learning presently limited to white students upon the same

terms and conditions applicable to white students; e) mak

ing attendance or matriculation of appellant and members

of his class in any state institution of higher learning condi

tioned upon terms and conditions not applicable to white

students similarly situated (R. Vol. I, pp. 15-16).

The motion for preliminary injunction, postponed sev

eral times, was finally heard (PI. Exh. 16, Vols. I, II),

3

in August 1961 and denied on December 14, 1961 (R. Vol.

II, p. 221).

On the same day, appellant filed notice of appeal to

this Court (R. Vol. II, p. 221) and pursuant to motion of

appellant the appeal was expedited and heard by this

Court on January 9, 1962 (E. Vol. II, p. 225). Thereafter,

on January 12, 1962 the denial of the motion for prelimi

nary injunction was affirmed and the ease immediately re

manded to the District Court for trial which had been set

for January 15, 1962 (R. Vol. II, pp. 228-247).

In denying appellant’s motion for preliminary injunc

tion the District Court had ruled: 1) Appellant was not

denied admission to the University solely because of race

and color; 2) Appellant had failed to present the required

alumni certificates; 3) Appellant was denied admission to

the February 8, 1961 term to which he first sought admis

sion due to overcrowded conditions; 4) The University

could not accept the credits which appellant sought to trans

fer from Jackson State College because of the regulation

adopted by the Committee on Admissions on May 15, 1961;

5) Jackson State College, the college from which appellant

sought to transfer, was not a member of the Southern As

sociation of Colleges and Secondary Schools, therefore,

appellant could not be accepted by the appellee Board on

February 7, 1961, barring transfer students from institu

tions whose programs are not approved by the University

and the Board; 6) Appellant falsely swore to the Deputy

Clerk of Hinds County that he was a resident of that

county when, as a matter of fact, he is a citizen and resi

dent of Attala County, Mississippi when appellant regis

tered to vote in February 1961 (R. Vol. II, pp. 210-221).

In affirming the denial of the motion for preliminary

injunction this Court ruled: 1) that the alumni certificate

requirement was unconstitutional as applied to Negroes;

4

2) that this Court would take judicial notice of the fact

that the State of Mississippi has a policy of maintaining

separate institutions of higher learning for Negro and

white students; 3) that both parties brought to the atten

tion of the Court the fact that since the hearing of the

motion for preliminary injunction, Jackson State College

had been admitted to membership in the Southern Associ

ation of Colleges and Secondary Schools; and, 4) in addi

tion, while the Registrar indicated that the application was

denied for “ other deficiencies” , the state of the record was

such, due to the leniency allowed appellees with respect

to proof and argument and restrictions placed on appellant

with respect to same, that this Court was not able to deter

mine whether the Registrar had, in fact, any other valid,

non-racial reasons for excluding appellant from the Uni

versity (R. Vol. II, pp. 228-245).

The trial of this case, set for January 15, 1962, did not

commence until January 16, 1962. It was postponed at

1:50 P.M. on that date until 3 o’clock P.M., January 17

to give appellees’ counsel an opportunity to confer with

the appellees (R. Vol. I ll, pp. 307-308). On January 17

at 3:00 P.M. the District Court heard a motion by appel

lees’ counsel for a continuance or postponement of the

trial on account of the physical inability of appellees’ chief

counsel, Dugas Shands, who had been hospitalized, and

the unpreparedness of appellees’ other counsel, Charles

Clark and Edward Cates, to proceed with trial (R. Vol.

I ll , pp. 309-359). At the end of the hearing on this motion

the court continued the trial until 2 o’clock, January 24,

1962 (R. Vol. I ll , pp. 359-360).

At the conclusion of the trial the court finally denied

all relief requested and dismissed the complaint (R. Vol.

V, p. 732). In an opinion rendered on February 3, 1962,

the court ruled: 1) That appellant failed to meet his bur

5

den by a preponderance of the evidence that he was denied

admission to the University of Mississippi solely because

of his race; 2) Facts not known to the Registrar at the time

the application was filed were not considered by the court

in reaching its decision; 3) The proof shows conclusively

that appellant was not denied admission because of his

race since every witness called by appellant testified that

the race of appellant was not discussed or considered at

all in passing on his application for admission, and each

member of the appellee Board who testified swore that the

question of race was not at any time discussed with any

of the other members of the Board concerning the admis

sion of applicants to the University of Mississippi; 4) The

proof shows, and the court found as a fact, that there is

no custom or policy now, nor was there any at the time

appellant’s application was rejected, which excluded quali

fied Negroes from entering the University; 5) The proof

shows, and the court found as a fact, that the University

is not a racially segregated institution; 6) Prior to the

decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347

U. S. 483 there was a custom of excluding qualified Negroes

from the University which was required by the statutes of

the State of Mississippi and the court takes judicial notice

of that custom as outlined by the statutes prior to the

Brown case (R. Vol. V, pp. 722-732).

Prior to the trial the court quashed that part of a sub

poena served by appellant on the Registrar requiring him

to produce at the trial student admission records at the

University for the February 1961 term. The Registrar was

required to produce only those records commencing with

the first summer term to time of trial (R. Vol. I ll , p. 294).

On February 5, 1962, the day on which the final order

was entered, appellant appealed to this Court (R. Vol. V,

p. 733) and on the same date filed here a motion for pre

6

liminary injunction pending appeal. This motion was heard

on February 10, 1962 and denied on February 12, 1962

(R. Vol. V, p. 734) (Chief Judge Tuttle dissenting). The

injunction was sought on the ground that unless appellant

was admitted to the University of Mississippi for the Feb

ruary 1962 Term, the case would become moot since appel

lant would have graduated from Jackson State College,

which he is presently attending, in June 1962 before the

appeal could be heard and determined in the normal course.

The injunction was denied on the ground that appellant

could avoid the mootness of his appeal by his non-atten

dance at Jackson State College for one quarter of the

school year or by being permitted to choose courses of

study other than those leading to his graduation. Appel

lant has pursued the latter course and is presently enrolled

at Jackson State College.

Statement of the Facts

1. Appellant’s Application

The Registrar received appellant’s application on Feb

ruary 1, 1961. On February 4, 1961 appellant received a

telegram from the Registrar advising him that applica

tions received after January 25, 1961 were not being con

sidered. In its opinion denying the motion for preliminary

injunction, the court below found as a fact that appellant

had been denied admission to the February 1961 term due

to overcrowded conditions (R. Vol. II, 215). On the trial

however, the Director of Student Personnel testified that

as of September 1961 there were approximately 3,000 male

students on the University campus at Oxford (R. Vol. I ll ,

390). During the Summer of 1961 there wrere approximately

1,000 or 1,200 male students on the campus (R. Vol. I ll,

390). In February 1961, when appellant was allegedly

7

denied admission because of overcrowded conditions, there

were only 2,500 or 2,600 male students on the campus (R.

Yol. I ll , 390). In the preceding semester, September 1960,

there were approximately 2,500 (R. Yol. I l l , 390-391).

Appellant’s counsel have never been permitted to inspect

the records of students admitted to the February 1961 term.

After receipt of the telegram, appellant requested the

Registrar on February 20, 1961 to consider his applica

tion a continuing one for the Summer Session 1961 (PL

Exh. 16, Vol. I, 22) and later requested consideration of

his application as a continuing one for the Summer and

Fall Sessions, 1961 (PL Exh. 16, Vol. I, 27-28). How

ever, after a series of letters to which the Registrar did not

reply, appellant wrote the Dean of the College of Liberal

Arts on April 12, 1961 complaining of the Registrar’s

failure to reply and requesting assurance that race was

not a factor in his inability to gain admission to the Uni

versity (PL Exh. 16, Vol. I, 43). The Dean never replied

to this letter, but on May 9, 1961 appellant received a let

ter from the Registrar advising appellant that ‘ ‘under the

standards of the University of Mississippi the maximum

credit which would be allowed (appellant) is 48 semester

hours” out of a total of 90 semester hours credit offered

by appellant. (Transcripts from colleges previously at

tended by appellant had been received by the Registrar

at that point and each showed a certificate of honorable dis

missal or certification of good standing—Pl. Exh. 16, Vol.

I, 46-47.) Subsequently, however, by letter dated May 25,

1961 the Registrar finally denied appellant’s application

for admission on the following grounds:

1. “ The University cannot recognize the transfer of

credits from the Institution which you are now at

tending since it is not a member of the Southern As

sociation of Colleges and Secondary Schools. Our

8

policy permits the transfer of credits only from mem

ber institutions of regional associations.”

2. “ Furthermore, students may not be accepted by the

University from those institutions whose programs

are not recognized.”

3. “ Your letters of recommendation are not sufficient for

either a resident or nonresident applicant.”

4. “ I see no need for mentioning any other deficiencies”

(PI. Exh. 16, Vol. I, 54-55).

2. Reasons for Denying Appellant’s Application

Prior to Trial

This Court, in its opinion affirming the denial of the mo

tion for preliminary injunction, held the alumni certificate

requirement unconstitutional as applied to Negroes.

The Court then pointed out that counsel for both parties

had called to the attention of the Court, on oral argument,

that since the hearing below Jackson State College had

been approved by the Southern Association of Colleges

and Secondary Schools, a fact having material bearing on

appellant’s right to admission (R. Vol. II, 241).

This Court also concluded that it was not clear from the

record whether the University gave any effect to appel

lant’s credits from the Universities of Maryland, Kansas

and Washburn and the 12 acceptable credits from Jack-

son State College.

Finally, this Court was unable to determine from the rec

ord whether the Registrar’s reference to Jackson State

College indicates that appellant was rejected simply be

cause he had attended that college or was rejected be

cause the University could not accept all of Jackson State

College’s credits (R. Vol. II, 241-242).

9

A. The University’s Policy Regarding Transfer

Students From Non-Member Colleges of

Regional Accrediting Associations

On February 7, 1961 (six days after appellant’s applica

tion was received), the appellee Board adopted a motion

“ that all state supported Institutions of Higher Learning

may accept transfer students from other state supported

Institutions of Higher Learning, private colleges or de

nominational colleges only when the previous program

of the transferring college is acceptable to the receiving

Institution, and the program of studies completed by the

student, and the quality of the student’s work in said trans

ferring college is acceptable to the receiving Institution

and to the Board of Trustees” (PI. Exh. 16, Yol. II, 383-

384).

The Registrar advised appellant of this policy in denying

his admission to the University on May 25, 1961:

“ Furthermore, students may not be accepted by the

University from the Institutions whose programs are

not recognized” (PL Exh. 16, Vol. I, 55).

On the trial, the Registrar testified that this meant that

appellant could not transfer from Jackson State College

because it was not a member of the Southern Association

of Colleges and Secondary Schools (R. Vol. IV, 478-480).

However, the Registrar acknowledged that in December

1961, Jackson State College was admitted to membership

in the Association (R. Vol. IV, 599) and testified that he

would now admit a qualified student from Jackson State

College (R. Vol. IV, 600).

Prior to December 1961, none of the three Negro in

stitutions of higher learning under the jurisdiction of ap

pellee Board was a member of the Southern Association

of Colleges and Secondary Schools. They were on an ap

10

proved list of Negro colleges maintained by the Association

(PL Exh. 16, Vol. II, 454-455 and R. Vol. IV, 529-531).

Moreover, at the time appellant applied for admission,

the University catalog (which was the only notice appel

lant had) simply provided that transfer students might

be accepted from another “approved Institution of Higher

Learning” (PL Exh. 42, Vol. II, 284). Jackson State Col

lege was approved at that time and still is by the Col

lege Accrediting Commission of the State of Mississippi

(Miss. Code, 1942, See. 6791.5). The Registrar testified that

he knew of his own knowledge that Jackson State College

was accredited by this Commission (Pl. Exh. 16, Vol. II,

468).

The Registrar claimed that 25 or 30 students had been

denied admission to the University as a result of the Feb

ruary 7, 1961 rule, but no such applications were produced

(R. Vol. IV, 593, 624).

At the trial, appellant’s counsel inspected 214 inactive

files of students who sought admission to the Summer Ses

sions 1961, the September Session 1961, and the February

1962 Session (R. Vol. IV, 624-625). Of this group, ap

pellant’s counsel found no student who, like appellant, had

successfully attended accredited as well as non-accredited

institutions and who had been denied admission to the

University (R. Vol. IV, 624). Only six files of students who

had been denied transfer to the University from non-ac

credited institutions were found. Five of these had at

tended only the one non-accredited school from which they

sought to transfer. One had, in addition, attended an ac

credited institution (Bucknell) but had done so poorly at

the latter institution that he could not have transferred to

the University of Mississippi from that institution for

scholastic reasons (R. Vol. IV, 630-639, Defs. Exhs. 1-6).

11

In short, the records shows that the February 7, 1961

rule operated to bar the admission of appellant although,

unlike these six, he had successfully attended accredited as

well as non-accredited institutions.

Moreover, as a practical matter, since the other students

affected by this policy had attended only a non-member

institution or had failed to receive passing grades at the

member institution as well as the non-member institution,

the policy really applied to them was the May 15th policy

which precludes the transfer of unacceptable credits. Since

these students had no credits to transfer, they could not

enter the University as transfer students.

B. The University’s Policy Regarding Transfer

of Credits From Non-Member Institutions of

Regional Accrediting Associations

On May 9, 1961, the Registrar wrote appellant that if

his application were accepted for admission to the Uni

versity, he, the Registrar, had tentatively concluded that

appellant would be entitled to 48 semester hours credit of

the 90 semester hours credit appellant offered (PL Exh.

16, Vol. I, 46). On the trial, the Registrar testified that

by this statement he meant that he could give appellant 6

semester hours credit for courses taken at the University

of Kansas, 3 semester hours credit for the work at Wash

burn University, and 24 semester hours credit for work

taken at the University of Maryland (although he had taken

more credits which could not be transferred under the Uni

versity rule limiting transfer of extension credits to a total

of 33), and could give appellant 12 semester hours credit

for work taken at Jackson State College, making a total

of 45 credits. The Registrar claimed that he could not

account for the other 3 credits which he had originally

advised appellant might be transferred (R. Yol. IV, 485-

486).

12

However, the Registrar wrote appellant on May 25, 1961

that the University could not recognize transfer of credits

from the institution which appellant was then attending

(Jackson State) since it was not a member of the Southern

Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools. This re

sulted from the fact that on May 15, 1961 (six days after

the Registrar had written appellant on May 9, 1961) the

Committee on Admissions adopted a policy prohibiting the

transfer of credits from institutions not members of their

respective regional accrediting associations or recognized

professional accrediting associations (PI. Exh. 16, Vol. II,

447-450).

On the trial, the Registrar testified that this policy did

not operate to preclude the acceptance of credits earned

at the University of Kansas, the University of Maryland

or Washburn University (R. Vol. IV, 583-586). It operated

to preclude the acceptance of credits only from Jackson

State College since it was not a member of its regional

accrediting association (R. Vol. IV, 587). The Registrar

testified that the May 15th policy means simply that he

could not “ accept the credits from institutions that are

not members of a regional accrediting association or a

recognized professional association” (R. Vol. IV, 587-588).

3. Reasons for Denying Appellant’s Admission

After Commencement of Suit

After this action was commenced in May 1961, the Regis

trar proposed bars to appellant’s admission to the Uni

versity on a number of other grounds.

A. First, the Registrar claimed, that appellant falsely

swore that he was a resident of Hinds County as a result of

which he procured his registration as a voter in that county

whereas he was in fact a resident of Attala County, Missis

sippi, as found by the court below. On the hearing of his

13

motion for preliminary injunction, appellant testified that

lie knew at the time that he registered to vote that he was

not a resident of Hinds County and explained this to the

clerk who nevertheless registered him. (PL Exh. 16, Yol.

I, 84, 86). Appellant answered in the affirmative to the ques

tion, “ You knew it was untrue” , when he swore on his poll

tax exemption receipt that he was qualified to vote in Hinds

County (PI. Exh. 16, Vol. I, 86). This receipt was given

to appellant when he explained to the clerk that he had

been in the service. However, the confusion was clarified

by the testimony of the Deputy Clerk of Hinds County who

testified that appellant was qualified to vote in that County

as he had swore on his poll tax exemption receipt since “he

had stayed there past the general election on Tuesday after

the first Monday of November which put him past one

general election, and then he would have lived there a

year before the next ensuing general election which would

be Tuesday after the first Monday in November of ’61”

(PL Exh. 16, Vol. II, 352-353). Appellant had never voted in

Hinds County he had only registered to vote (PL Exh. 16,

Vol. I, 223). Moreover, appellant’s application to register

as a voter shows conclusively that he did not falsely rep

resent his residence or the length of time he had been in

Hinds County (Pl. Exh. 29). He stated on his application

that he had lived in Hinds County beginning September

1960.

B. Secondly, the Registrar testified that he would not

now admit appellant to the University of Mississippi be

cause: “ From the deposition that was taken of Meredith,

I am convinced that he is a man that was trying to make

trouble simply because he was a Negro. From the records

which we received from the United States Air Force, there

is an indication that the man does have psychological prob

lems in connection with his race. I have seen some of the

material to which he testified that he had knowledge and

14

that he participated in the publication, which indicates to

me a man that is not trying to be a student for the sake

of learning a profession or getting an education, but a man

who has got a mission in life to correct all of the ills of the

world; so I am convinced that this man is a trouble maker

and I think he would be a very bad influence at my In

stitution” (R. Vol. V. 682-683). (Emphasis added.)

Early in August of 1961 when the hearing on appellant’s

motion for preliminary injunction had been recessed,

Charles Clark, one of the counsel for appellees secured, with

appellant’s permission, part of appellant’s Army record

(PL Exh. 16, Vol. II, 325). Excerpts from this record,

which on the whole is very good and qualified appellant

for an honorable discharge from the Air Force, were seized

upon by the Registrar as his basis for the claim that ap

pellant should be barred from the University because he

was obsessed with the question of race (R. Vol. V, 684).

However, the Registrar admitted that appellant is the only

student that he sought to bar from the University because

he believed him to be obsessed with race. White students

who may be obsessed with the question of race were not

subject to a similar bar (R. Vol. V, 684). The Registrar

also admitted that veterans are not investigated prior to

admission (unless an unusual case is brought to his atten

tion by the Veterans Administration) to determine whether

they have Army records indicating psychological prob

lems (R. Vol. V, 684-685). The Registrar could recall only

one case of a veteran who had a health record indicating

some psychological problem, the record having been sent

to him by the Veterans Administration (R. Vol. V, 686-687).

In one other case of a non-veteran, the Registrar remem

bered that there was a student who had a serious brain

injury rendering him psychologically unfit and for this

reason was not admitted (R. Vol. V, 686-688).

15

C. Thirdly, the Registrar claimed that he could not now

admit appellant to the University because he had received

a letter from the Attorney General of the State of Missis

sippi, dated January 16, 1962 (the date on which the trial

commenced), transmitting affidavits dated January 15, 1962

(the date on which the trial was to commence) from the

five Negro residents of Attala County who had signed cer

tificates of good moral character for appellant recommend

ing his admission to the University. In these affidavits four

affiants stated, in substance, that they did not know that

they were signing the certificates for the admission of ap

pellant to the University and did not know anything about

appellant’s good moral character since they had not seen

him much during the time he was in the Air Force (R. Vol.

V, 662-669). One of the affiants refused to sign the affidavit

(R. Vol. V, 708-709) which reads as follows (R. Vol. V,

669):

State of M ississippi

Cotthty of A ttala

AFFIDAVIT

Personally appeared before me Lannie Meredith,

who after being duly sworn states on oath that the

following is true and correct:

That on 29 January, 1961, James Howard Meredith

who is my first cousin, came to see me with a pre

pared certificate certifying to his moral character

which certificate I executed.

James Howard Meredith later came to see me on 26

March, 1961, with a prepared statement and requested

me to sign this statement; at the time of the signing

of this statement I knew full well and was aware of the

purpose for which such certificate was to be executed.

I am not now nor have I ever been in any serious

trouble or convicted of any crime or misdemeanor.

16

In Witness Whereof I set my hand and seal, this

the 15th day of January, 1962.

Notary Public

Sworn to and Subscribed before me this January 15,

1962.

My commission expires on

..... day of ......... ............. 19....

Seal

These affidavits were secured by one of the attorneys

for appellees, Edward L. Cates, Assistant Attorney Gen

eral of Mississippi. The affiants did not approach this

official or any other person to volunteer the information

given in the affidavits. All of these affiants are Negroes

living in a rural Mississippi County. These affiants were ap

proached (the day before the trial) by appellee’s counsel

(who was then as now representing the State in opposing

appellant’s admission to the University) and another at

torney by the name of John Clark Love, a Mississippi

State Senator and former member of the State Sovereign

Commission (Mississippi’s official pro-segregation agency).

The affidavits were drawn by appellee’s counsel and pre

sented to affiants for signature (R. Yol. V, 706-714). None

of the affidavits alleges that appellant is a person of bad

moral character. Two of the affiants claimed that appel

lant represented to them that he needed the certificate to

help him secure a job (R. Vol. V, 663-664, 666-667). One of

the affiants claimed that he did not read the certificate (R.

Vol. V, 665). However, the attorney who secured the affi

davits testified that the affiants could read (R. Vol. V,

710).

17

The Registrar admitted that normally an application is

not questioned with respect to certificates of good moral

character. “ It is only when there is some occasion to check

into it that we do” (R. Vol. V, 684). “ And offhand, I don’t

know of any that we have checked into recently” (R. Yol. V,

684). The Registrar, of course, did not check these cer

tificates. He had no reason to.

Appellees’ counsel then sought to introduce in evidence

additional affidavits signed by these same affiants on Janu

ary 20, 1962 (during a period when the trial was in recess

from January 17th to January 24th, 1962) which were

obviously intended to contradict any assertion which might

have been made by appellant’s counsel that the affiants

had been coerced into signing the January 15th affidavits.

However, the trial court would not permit these affidavits

to be put in evidence. These affidavits are copied at pages

699 to 704 of Volume V of the Transcript of the Trial.

4. Mississippi’s Racial Policy Remains Unchanged

Upon the prior appeal, this Court ruled that the state

of the record was such that it was unable to determine

whether Mississippi’s segregation policy operated in this

case to exclude appellant from the University (R. Vol. II,

240). This Court took judicial notice of the State’s policy of

operating separate institutions of higher learning for Negro

and white students (R. Vol. II, 238). The District Court,

however, construed this Court’s decision as holding merely

that the State had such a policy prior to the Supreme

Court’s decision in the Brown case in 1954 and appellant

had the burden of showing that this policy has been in

effect since 1954 (R. Vol. IV, 514-515).

On the trial, appellant’s counsel examined nine members

of the appellee Board and its Executive Secretary and

established conclusively that the policy has not changed

18

since 1954. The Executive Secretary’s testimony was

candid and unequivocal.

“ Q. After the Supreme Court’s decision in 1954,

did the Board take any action with regard to the ad

mission of Negroes to the University of Mississippi?

A. No” (R. Vol. IV, 515).

This salient fact was corroborated by the Board mem

bers who testified that the Board has never even discussed

the admission of Negroes generally to the University (R.

Vol. IV, 497, 504, 506, 533-534, 545-546, 551-552, 552-553,

555-556, 557). And after appellant applied for admission,

the Board did not even discuss his application (R. Vol. IV,

496, 504, 505, 513, 533-534, 544-545, 549, 556, 558). The

Board members neither discussed appellant’s application

with the Registrar (R. Vol. IV, 488-489) nor any other ad

ministrative official of the University (R. Vol. IV, 499-

500, 504, 509, 534-535, 546, 550, 556). The Board did not

discuss the admission of Negroes generally or the applica

tion of appellant despite the fact that appellant’s applica

tion led to front page newspaper reports to the effect that a

Negro was seeking admission to the University and trouble

was expected (R. Vol. IV, 538-539, 559-563; PI. Exhs. for

Identification 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27).

In the wake of all this publicity, a member of the Uni

versity’s Committee on Admissions claimed that this Com

mittee neither discussed appellant’s application (R. Vol.

I ll, 373) nor the admissions of Negroes generally (R. Vol.

I ll, 375) at any committee meeting or with any other Uni

versity officials (R. Vol. I ll , 379-380). Moreover, the Com

mittee never received any memorandum or any other writ

ing from any official of the University regarding appellant’s

application or the admission of Negroes generally (R. Vol.

I ll , 380).

19

Appellant’s counsel was consistently prevented from

asking University officials their understanding of the Uni

versity’s policy with regard to the admission of Negroes (R.

Yol. I l l , 380, 403, 428; Vol. VI, 522-523).

Officials who testified, in addition to Board members,

were the Dean of Women (R. Vol. I ll , 370), the Dean of

the Division of Student Personnel (R. Vol. I ll , 389), the

Dean of the School of Law (R. Vol. I ll , 411), the Chancellor

of the University (R. Vol. IV, 524), the Vice-Chancellor

(R. Vol. I ll, 423), the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts

to which appellant sought admission (R. Vol. IV, 520), and,

of course, the Registrar (R. Vol. I ll , 433).

The Dean of Women is a member of the Committee on

Admissions (R. Vol. I ll, 372). She testified that appellant’s

application was never discussed at any meeting of Uni

versity officials (R. Vol. I ll, 371-373), and that she has

never received any memorandum or other writing from any

officials of the University regarding the admission of

Negroes, generally, or this applicant (R. Vol. I ll, 380).

The Dean of the Division of Student Personnel testified

that he talked with officials in general about the application

but never with regard to its merits (R. Vol. I l l , 394). He

discussed it casually with the Dean of the College of Liberal

Arts (R. Vol. I ll, 396) and with the Chancellor (R. Vol. I ll,

396-397) but did not discuss the application with any mem

ber of the Board (R. Vol. I ll , 398). He also has neither

received any written communication from the Board or

discussed with it the admission of Negroes generally (R.

Vol. I ll, 399). He has been on the University campus in

his present position since 1949 (R. Vol. I ll, 401).

The Dean of the Law School testified that he discussed

the application with the Chancellor and the Provost and

talked to each member of the law faculty (R. Vol. I ll ,

20

411-412). He discussed the application with the President

of the Board of Trustees and Mr. Tubb, a Board Member,

in a casual manner, but not the merits. The casual talk

consisted of a discussion of the latest news regarding the

application (R. Vol. I ll , 415). This official of the University

testified that in 1952 a Negro by the name of Charles Dubra

applied for admission to the Law School and at that time

he discussed the admission of Negroes generally at a Board

meeting. However, the court below prevented any further

examination of this witness with respect to this discussion

with the Board on the ground that it occurred prior to

1954 (R. Vol. I ll, 417-418). Appellant’s counsel was also

prevented from asking this witness what his instructions

are with regard to the admission of Negroes (R. Vol. I ll ,

419). This official confirmed the fact that appellant’s ap

plication was widely publicized in February 1961 when the

application was filed (R. Vol. I ll , 420). And this witness’

testimony made clear what the policy is ; no Negro has been

admitted since his connection with the University beginning

in 1926 (R. Vol. I ll , 421).

The Vice-Chancellor learned of appellant’s application

from the newspapers (R. Vol. I l l , 426) and the Chancellor

told him the application was being handled as all other

applications (R. Vol. I ll , 425), but he has never received

any oral or written instruction from the Board or other

official of the University regarding admission of a Negro

(R. Vol. I ll , 428).

The Registrar discussed appellant’s application with Mr.

Hugh Clegg when he became “ convinced” appellant was go

ing to “ face the University with a lawsuit” (R. Vol. IV,

490-491). Mr. Clegg, the Director of Development and an

assistant to the Chancellor agreed with the Registrar’s

conclusion (R. Vol. IV, 490-491). The Registrar also dis

cussed the application with the Attorney General’s office

21

before the suit was instituted (E. Yol. IV, 491). On two

occasions he discussed the application with the Dean of the

College of Liberal Arts. First, he consulted with the Dean

on an evaluation of appellant’s credits. The Dean did not

corroborate this. He also talked to the Dean “ on the

telephone”, when the Dean received a letter from appel

lant complaining of the Registrar’s failure to reply to ap

plicant’s many letters regarding his application (R. Vol. IV,

492). The Dean could not remember this (R. Vol. IV, 521).

In addition to testifying that he had never discussed ap

pellant’s application with the Board (PI. Exh. 16, Vol. II,

323), the Registrar testified that he has never received any

instructions from the Board regarding the admission of

Negroes and has never discussed with the Board the ad

mission of Negroes generally (R. Vol. IV, 493). He has

never discussed the admission of Negroes generally with

the Chancellor (R. Vol. IV, 493), or the Dean of the Col

lege of Liberal Arts (R. Vol. IV, 493) or with the staff

in the Registrar’s office (R. Vol. IV, 493).

When the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts received

appellant’s letter dated April 12, 1961 (PI. Exh. 16, Vol.

I, 43) he forwarded the letter to the Registrar without

a word (R. Vol. IV. 521). The Dean was asked:

“Q. What else did you do? A. That closed the mat

ter. so far as I was concerned” (R. Vol. IV, 521).

He sent no memorandum or other letter with appellant’s

letter to the Registrar (R. Vol. IV, 521) and could not re

call even discussing the letter with the Registrar over the

telephone. He testified that he called the Chancellor’s Secre

tary and asked her whether he should handle this letter in

the usual manner and she replied “ Yes” (R. Vol. IV, 521-

522), but he never discussed the application with the Chan

cellor himself or any member of the Board (R. Vol. IV,

522). When appellant wrote the Dean, he asked the Dean

22

to give Mm “ some assurance that [his] race and color are

not the basis for [his] failure to gain admission to the Uni

versity” (PI. Exh. 16, Yol. I, 43). The Dean never replied

to this letter.

The Chancellor has been in his position since 1946,

long prior to the Supreme Court’s decision in 1954 outlaw

ing segregation in the public schools. He testified that he

had never seen appellant’s application until it was ex

hibited to him by appellant’s counsel on the trial (R. Vol.

IY, 526). The Chancellor was asked:

“ Q. Have you ever discussed the admission of

Negroes generally with the Board of Trustees? A.

Never have” (R, Vol. IV, 524).

In addition, he was asked:

“ Q. Do you know of any action taken by the Board

since the Supreme Court’s decision in 1954 with re

gard to the admission of Negroes to the University

of Mississippi? A. I do not know of any” (R. Vol. IV,

525).

He testified that he discussed the application, he believed,

with Dean Love (R. Vol. IV, 525), and “ indicated” to him

that since he was head of the Division of Student Person

nel, this application should be handled as all other applica

tions are handled at the University of Mississippi, but ad

mitted that he did not tell Dean Love that Negroes are

admitted to the University just as anyone else (R. Vol.

IV, 527). On cross-examination, he claimed that to the best

of his knowledge, no official of the University has the au

thority to deny the application of a qualified applicant

for admission to the University on the basis of race or color

(R. Vol. IV, 527) but then admitted that nobody has ever

even discussed the question (R. Vol. IV, 528).

23

Specification of Errors

I. The court below erred in finding as a fact that

appellant had not been denied admission to the

University solely because of race and color.

II. The court below erred in concluding that appellant

had failed to show by a preponderance of the evi

dence that the University now has a policy of ex

cluding qualified Negro applicants which operated

in this case to bar the appellant.

III. The court below erred in limiting proof of racial

discrimination to the University of Mississippi, only

one of several institutions of higher learning under

the jurisdiction, management and control of the

appellee Board.

IV. The court below erred in denying the detailed in

junctive relief prayed for and in dismissing the

complaint on this record.

24

ARGUMENT

Appellant lias been denied admission to the University

of Mississippi solely because of his race and color and

pursuant to rules and regulations and other criteria

applicable only to his case.

A. Appellant’s Race Precluded His Admission to

the University By Reason of the University’s

Unchanged Racial Policy

From the outset of this case, appellant has contended

that when the University of Mississippi received his ap

plication for admission with the word “ Negro” placed in

the blank beside the query “Race,” with his photograph

attached to the application, and with a letter stating “ I am

an American-Mississippi Negro citizen” (PL Exh. 3, Vol. I,

17), appellees invoked their unwritten but firmly fixed

policy of excluding all Negro applicants, and the denial of

his application four months later followed inevitably.

Now, the events of those intervening months, and the

subsequent history of this case documented in the 1341

pages of the record and summarized in the preceding sec

tions of appellant’s brief, show, beyond any doubt, that

the policy of excluding Negroes from the University, so

much a matter of common and historical knowledge that

this Court has taken judicial notice of it (R. Yol. II, 238)

was indeed the principle factor in the denial of appellant’s

application.

No lengthy discussion of the cases which have led to the

admission of Negroes to state institutions of higher learning

throughout the South is required to show that appellant’s

exclusion by reason of race from the University of Mis

sissippi violated his rights under the equal protection clause

25

of the Fourteenth Amendment.1 Suffice to say that these

cases hold Constitutional rights are no less infringed when

the racial policy of excluding Negroes is not expressly set

forth in any statute, Board resolution, or other writing.

Holmes v. Danner, 191 F. Supp. 394, 402 (M. D. Ga. 1961);

Lucy v. Adams, 134 F. Supp. 235 (N. D. Ala. 1955), aff’d.

228 F. 2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955), cert. den. 351 U. S. 931. See

also 350 U. S. 1 (1955). The District Court in the Lucy

case found:

“ There is no written policy or rule excluding prospec

tive students from admission to the University on ac

count of race or color. However, there is a tacit policy

to that effect.” 134 F. Sirpp. at 239.

Here, as in Alabama at the time of the Lucy case, the

policy of excluding Negroes from the University of Mis

1 Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936) (M d.);

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) ; Sweatt

v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) (Texas); McLaurin v. Board of

Regents, 339 U. S. 637 (1950) (Okla.) ; Wilson v. Board of Su

pervisors of L. S. V., 92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La. 1950) aff’d

340 U. S. 909; Parker v. University of Delaware, 31 Del. Ch. 381,

75 A. 2d 225 (Del. Ch. 1950) ; Swanson v. University of Virginia,

Civ. No. 30 (W. D. Va. 1950) (Unreported); Wilson v. City of

Paducah, Ky., 100 F. Supp. 116 (W. D. Ky. 1951) ; Gray v. Board

of Trustees TJniv. of Tenn., 342 U. S. 517 (1952) ; Tureaud v.

Board of Supervisors of L. S. 77., 116 F. Supp. 248 (E. D. La.

1953) rev’d 207 F. 2d 807 (5th Cir. 1953) vacated and remanded

347 U. S. 971 (1954) on remand 225 F. 2d 434 (5th Cir. 1955)

on rehearing 228 F. 2d 895 (5th Cir. 1956) cert. den. 351 IJ. S.

924; Lucy v. Adams, supra, (Ala.) ; Frazier v. Board of Trustees

Univ. of N. C., 134 F. Supp. 589 (M. D. N. C. 1955), aff’d 350

U. S. 979; Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of L. S. 77., 150 F. Supp.

900 (E. D. La. 1957), aff’d 252 F. 2d 372 (5th Cir. 1958), cert,

den. 358 U. S. 819; Booker v. State of Tenn. Bd. of Education,

240 F. 2d 689 (6th Cir. 1957) ; cert. den. 353 U. S. 965; Hawkins

v. Board of Control of Florida, 347 U. S. 971 (1955); 350 U. S.

413 (1956) ; 355 U. S. 839 (1957) 162 F. Supp. 851 (N. D. Fla.

1958); Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N. D. Ga. 1959)

(Georgia) ; Holmes v. Danner, 191 F. Supp. 394 (M. D. Ga. 1961)

(Georgia).

26

sissippi is unwritten. Indeed, it was the uniform testimony

of members of the appellee Board and University officials

that since 1954, when the policy of excluding Negroes was

acknowledged, the Board has taken no action with regard

to the admission of Negroes (R. IY, 515). The Board, ac

cording to appellees, has not even discussed such admis

sions (R. Vol. IV, 497, 504, 533-534, 545-546, 551-552, 552-553,

555-556, 557).

But whether discussed or not, the effectiveness of the

policy is reflected in the continued total absence of Negro

students or alumni from the leading University of a state

with a substantial Negro population. University officials,

most of whom have been connected with the University

for many years, could not recall even one student or alumnus

of the University whom they personally knew to be a Negro

(Vol. I l l , 380-381, 421, 426-427), and in all the files of

transfer students accepted at the University from the 1961

Summer term until the February 1962 Semester, not one

student gave his race as Negro.

As to appellant’s application, members of the appellee

Board report that they took no action on it (R. Vol. IV,

496, 504, 505, 513, 533-534, 544-545, 549, 556, 558), and while

the application received wide publicity (R. Vol. IV, 538-

539, 559-563, PI. Exhs. for identification 19, 20, 21, 22, 23,

24, 25, 26, 27), most officials testified that they had not even

discussed it with the Registrar (R. Vol. IV, 558-559), or

any other administrative official of the University (R. Vol.

IV, 499-500, 504, 509, 534-535, 546, 550, 556). Even the

University’s Committee on Admissions reportedly never

discussed appellant’s efforts to enter the University (R.

Vol. I ll, 373), and received no memorandum or other writ

ing from any official of the University regarding his ap

plication or the admission of Negroes generally (R. Vol.

I l l , 380). In the light of all such testimony by appellees

27

the only logical conclusion is that the pre-1954 policy of

excluding Negroes from the University remains unchanged,

and when the appellant indicated his membership in the

Negro race, the policy was applied to him.2

But appellant need not rely on the rules of syllogistic

reasoning to prove that the University’s policy of excluding

Negroes was applied to him. He has the very substantial

record in this case.

First, the University application required appellant to

indicate his race and the Registrar testified that this ques

tion is asked for “ informational and statistical purposes”

although he admitted that no statistics are maintained on

the subject (PI. Exh. 16, Vol. II, 397-398).

Next, the appellant had the problem of furnishing letters

of recommendation from University alumni wThich this

Court found to exert so great a burden as to render the

requirement unconstitutional as applied to Negro appli

cants. Significantly, as this Court has noted, the Uni

versity adopted this requirement in late 1954, a fewT months

after Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka- was decided.

After appellant submitted his application, it was not

considered for the February 1961 term because of over

crowded conditions (PL Exh. 16, Vol. II, 403-404; R. Vol. II,

214). However, the Director of Student Personnel later

testified that there were for the September 1961 term ap

proximately 3,000 male students on the Oxford Campus,

and only 2,500 or 2,600 male students for the February 1961

term when appellant’s application was submitted and not

considered (R. Vol. I ll , 390). Further, this official testified

at R. Vol. I ll , 391:

2 See Generally, II Wigmore on Evidence, §437 (3d ed. 1940).

“ Q. Did you turn any students away in February

1961 on the ground you didn’t have housing for them?

A. Not to the best of my knowledge.”

When after a determined series of letters from appel

lant, the University finally decided that he was not eligible

for admission, the exclusion was based on the appellant’s

inability to comply with the invalid alumni certificate re

quirement, various undisclosed reasons, and two new rules

governing the admission of transfer students, both of which

were applied to appellant’s application notwithstanding the

fact that they were adopted after he filed for admission.

Appellees maintain that both the February 7, 1961 rule

providing that state colleges need accept only transfer

students from colleges approved by their Regional Ac

crediting Associations (R. Vol. IV, 590-591), and the May

15, 1961 rule preventing the recognition of credits earned

by transfer students at unaccredited schools (R. Vol. IV,

582-583), were adopted solely to improve the scholastic

calibre of transfer students admitted to the University.

While neither rule is now a bar to appellant’s applica

tion because Jackson State College is now a member of the

Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools

(R. Vol. IV, 528-529), when adopted, both rules had the

effect of barring not only appellant’s application, but the

transfer of students from any of the public colleges for

Negroes in Mississippi, none of which at that time were

members of the Southern Association. As a result, Negro

college students attending unaccredited Negro state schools

were effectively barred from obtaining the advantages of

the accredited education offered white students at the Uni

versity of Mississippi, and were thereby clearly denied

rights to which they were entitled even prior to the Brown

29

decision of 1954. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950);

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 (1950).

Thus, the University policy of excluding Negro students

which, according to the testimony of University officials,

has not even been, seriously discussed since 1954, continues

effective through recently adopted rules and requirements

which, while not referring to race, have the effect of dis

qualifying appellant and other members of his race.

As indicated above, such procedures are as violative of

appellant’s rights as the direct application of the “No

Negroes” policy because the Fourteenth Amendment pre

vents appellees from denying appellant’s rights by devices

both “ ingenious and ingenuous.” Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1.

After commencement of this suit and the taking of ap

pellant’s deposition, which occupies over 100 pages of this

record (Def. Exh. 7), appellees announced several additional

reasons for denying appellant’s application, all of which

contained a strong resemblance to the no longer discussed

policy with regard to the admission of Negroes. A few

sheafs of plain surplus Army stationery used by appellant,

a veteran of nine years in the United States Air Force,

caused appellees to raise questions as to his honesty, led

to inquiries as to other government property in his pos

session and required his production of the serial number

of a typewriter purchased subsequent to his discharge.

A In addition, reasonable confusion as to the appellant’s

county of residence when he registered to vote, confusion

easily clarified by appellant’s counsel’s cross-examination

: of the Deputy Clerk (PI. Exh. 16, Vol. II, 355-358), was

I interpreted by appellees as intentional misrepresentation.

AUnervous stomach which an Air Force psychiatrist diag

nosed as due in part to appellant’s concern over racial

incidents in this country and elsewhere, and for which he

30

determined no treatment necessary, was deemed by appel

lees sufficient reason to rule appellant too unstable to be

a student.

The Registrar testified that it was his opinion that the

appellant was trying to make trouble simply because he is

a Negro and would not be a good influence at the University.

The Registrar also reported at the end of the trial that

the Board’s requirement that students have good moral

character made necessary the denial of appellant’s ap

plication in view of the affidavits obtained by state officials

from the persons who had signed letters of recommenda

tions for the appellant (R. Yol. Y, 670). Yet these affidavits

do not allege that appellant is a person of bad moral char

acter, and considering the circumstances under which they

were obtained, utterly fail to contradict the brief, simple

letters which these persons originally signed at the ap

pellant’s request.

Indeed it is submitted that the after-the-fact reasons

appellees offered to justify appellant’s exclusion from the

University only served to highlight the great disparity be

tween the liberal admission standards applied to white

applicants, and the rigorous demands made on the ap

pellant.3

3 White transfer students for the Summer Sessions are permitted

to attend classes pending the receipt of all transcripts and alumni

certificates (PI. Exh. 16, Vol. II, 299-302). But the Registrar

concluded that appellant had failed to meet requirements for ad

mission because, inter alia, he “had not bothered to keep us sup

plied or to supply us with a completed record of his credits at

Jackson State College.”

Plaintiffs Exh. 54 (PI. Exh. 16, Vol. II, 314) is the file of a

student admitted with a scholastic record so poor that he was not

eligible for readmission at the school from which he transferred.

Nevertheless, he was admitted to the University, albeit on a pro

visional basis.

31

B. The Rules and Other Criteria Used to Bar

Appellant’s Admission Were Applicable

to His Case Alone

The record is replete with evidence that appellant’s ap

plication was subjected to rules and standards which would

not have been applied to similar applications from white

students. For example, the Board rule of February 7,

1961, restricting transfer admissions to students coming

from accredited schools was allegedly intended to improve

the scholastic caliber of transfer admissions. However,

a review of approximately 214 inactive files of college stu

dents who unsuccessfully have sought transfers to the

University since the rule went into effect revealed that

none had successfully attended both accredited and unac

credited colleges as had the appellant (R. Yol. IV, 624).

Six students from nonaccredited institutions had been de

nied transfer to the University under the February 7th

rule, but five of these had attended only the one non-

aecredited school from which they sought to transfer, and

the sixth student, who had attended an accredited insti

tution, was ineligible for readmission by reason of a poor

scholastic record (R. Vol. IV, 630-639, Defs. Exhs. 1-6).

Two of the six white students denied admission under the

February 7th policy were invited to reapply after com

pleting a year’s work at a Mississippi junior college. The

other four files exhibited little evidence that the applicants

would be able to successfully do college work, and it is

likely that their applications would have been denied even

in absence of the February 7th rule.

It appears, then, that the February 7th rule, while hardly

necessary to deny applications of white transfer students

with poor academic records, served to bar appellant and

perhaps other Negro applicants in his situation who have

32

attended and done well in accredited institutions, but by

reason of situations such as that existing for so long in

his home state, found it necessary to enter a nonaccredited

institution prior to submitting an application to the Uni

versity. As indicated above, only one of 214 unsuccessful

applications for transfer to the University was made by

a white student who had gone from accredited to non

accredited institutions before applying to the University.

This student had done poorly at the accredited school and

did no better at the nonaccredited institution. The ap

pellant, on the other hand, had done better than average

work at each of the institutions he has attended. His

attendance at four different colleges prior to filing his

application with the University of Mississippi was due to

the necessity of fulfilling his military obligations rather

than an inability to perform the work offered at each of

the schools. Clearly the February 7, 1961, rule served to

bar the application of the appellant with no indication that

it would pose similar handicaps to white students. Indeed,

a similar conclusion may be reached as to the May 15th

policy since white applicants seeking transfer from non

accredited schools would likely have attended only the

nonaccredited institution and thus would not be forced to

sacrifice nonaccredited school credits to gain admission as

required by this rule.

Thus, both the February 7th and May 15th rules, adopted

by appellees after appellant filed his application with the

University, placed serious barriers in the path of appel

lant’s admission, but would not likely affect the admission

of any other transfer applicant with a scholastic record

similar to the appellant’s. Acts of Congress which infringed

upon the rights of citizens in a manner similar to the

February 7th and May 15th rules have been invalidated

33

as in the nature of Bills of Attainder. United States v.

Lovett, 328 U. S. 303 (1946). Such rules when promulgated

by public officials such as appellees should be cause for close

judicial scrutiny. Especially is this so when such rules are

drawn so as to affect only a single individual or class.

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886).

Certainly, the principle of Yick Wo v. Hopkins, supra,

was seriously strained by the appellees’ administrative

handling of the appellant’s application. The Registrar, for

example, admitted that the certificates of good moral char

acter accompanying an application are not generally inves

tigated unless there is some reason to do so (R. Vol. V,

684). In this case, the Registrar did not have reason to

check the certificates, but a special investigation was made

by the State Attorney General, and affidavits were secured

by representatives of the state from Negroes under circum

stances raising serious questions of duress. That appellees

were cognizant of this is shown by their attempt to intro

duce a second set of affidavits devoted to disclaiming any

duress in the taking of the first set (Defs. Exh. 9, Vol. V,

699-704). A far more effective method of ruling out duress,

and one more in line with the traditional rules for the

admission of evidence, would have required appellees to

produce the affidavits in court and obtain their testimony

under circumstances permitting the court to observe their

demeanor on the stand, and giving appellant’s counsel the

right to cross-examination. See, 6 Wigmore on Evidence,

§1709 (3d Ed., 1940).

The Registrar also admitted that veterans are not in

vestigated prior to admission to determine whether they

have Army records indicating psychological problems (R.

Vol. V, 684-685), and certainly there is no precedent for this

case where appellant was requested to give his written per

mission to appellees who sent one of their attorneys on a

34

special trip to St. Louis, Missouri, to review and have copies

made of large portions of appellant’s service record. As

with other aspects of the appellees’ investigation of appel

lant’s background, emphasis was placed not on the obtaining

of all information, but on the gathering of unfavorable

facts which could be used to justify his exclusion from the

University.

The Registrar and the other appellees have stoutly denied

that appellant’s application was denied because he is a

Negro. Appellant submits that the record in this case leads

to the opposite conclusion. In any event, the myriad of

reasons for rejecting appellant’s application have dwindled

during the course of this litigation to one. Appellees state

that appellant’s application for admission to the Liiiversity

of Mississippi indicates that he is trying to make trouble

simply because he is a Negro, and is not sincerely interested

in obtaining an education (R. Vol. IV, 482; V, 682-683).

A similar conclusion could be reached as to any Negro

who attempts to breach the racial barrier at the University

of Mississippi. Legally, the appellant’s motives are not

crucial to this case. Dor emus v. Board of Education, 342

U. S. 429, 434-435 (1952); Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202

(1958); Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847, 857 (N. D. Ga.

1959). Factually, appellant’s motives have been accurately

set forth by this Court: “ James H. Meredith is a Mis

sissippi Negro in search of an education” (R. Vol. II, 228).

He submits that on the record and the law, he should be

admitted to the University of Mississippi.

35

CONCLUSION

W herefore, appellant respectfully submits that the judg

ment of the Court below should be reversed with orders

to enjoin the appellees from denying appellant the right

to enter the University of Mississippi as a transfer student

at the first Summer Session 1962, on terms and conditions

no different than those applied to white students similarly

situated. Appellant prays that such order will enjoin ap

pellees from interfering with the right of plaintiff and the

members of his class to register and attend the University

of Mississippi or any other state institution of higher learn

ing presently limited to white students, and will grant what

ever other relief including costs which in this Court’s

opinion is deemed appropriate.

Respectfully submitted,

Constance B aker Motley

Jack Greenberg

D errick A. B ell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R, J ess Brown

1105% Washington Street

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Attorneys for Appellant

â mgfen 3 8

.