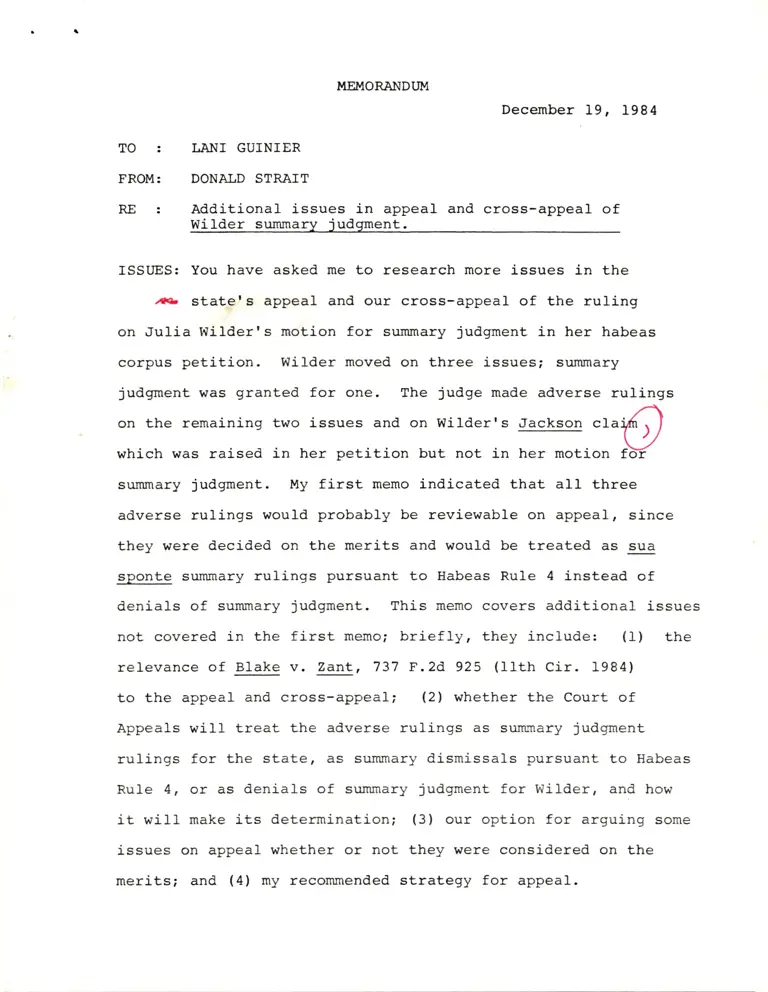

Memorandum from Strait to Guinier

Working File

December 19, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Memorandum from Strait to Guinier, 1984. dab50d55-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b836524d-f128-4643-8bc0-a9ce2aedba32/memorandum-from-strait-to-guinier. Accessed February 09, 2026.

Copied!

TO:

FROM:

RE:

IT{EIUORANDT'I\,1

December 19, 1984

I,ANI GUINIER

DONAID STRAIT

Additional issues in appeal and cross-appeal of

Wilder summary iudcrment.

ISSUES: You have asked me to research more issues in the

Alb stater s appeal and our cross-appeal of the ruling

on Ju1ia Wilder's motion for sunmary judgment in her habeas

corpus petition. wilder moved on three issuesi sunmary

judgrment was granted for one. The judge made adverse rulings

on the remaining two issues and on Wilder's Jackson "f.+()

which was raised in her petition but not in her motion tJ

sunmary judgment. ltly first memo indicated that all three

adverse rulings would probably be reviewable on appeal, since

they were decided on the merits and would be treated as sua

sponte srumary rulings pursuant to Habeas RuIe 4 instead of

denials of summary judgment. This memo covers additional issues

not covered in the fj-rst memo; briefly, they include: (1) the

relevance of Blake v. Zant,737 F.2d 925 (llth Cir. 1984)

to the appeal and cross-appeal i l2l whether the Court of

Appeals will treat the adverse rulings as surunary judgrrnent

rulings for the state, dS summary dj-smissals pursuant to Habeas

Rule 4, or as denials of sunrmary judgment for Wilder, and how

it will make its determination; (3) our option for arguing some

issues on appeal whether or not they were considered on the

merits; and (4) my recommended strategy for appeal.

SHORT AI.ISWERS: (r)

1984)

B1ake v. Zant, 737 t.zd 925 (t1th Cir.

, holds that Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b) applies

by Habeas RuIe 4 to summarily dismiss the habeas

to habeas proceedings and that absent an appropriate determirTrr

\

tion, final rulings must be made on aI1 claims before a" ora(y'( iS

)

appealable. However, it indicates that in our situation, wfrele- )

the prisoner has been ordered releasedr Bn entry of final

judgrrnent and a Rule 54 (b) determination of "rD just reason for

de1ay" may render the order appealable.

l2l Courts approach questions concerning

the nature of a ruling with a fair amount of practicality,

looking at the nature of a courtrs analysis and the effects of

its rulings to determine the type of ruling it has made. Thus,

it seems likely that the Court of Appeals will treat the district

courtrs adverse rulings as final, appealable rulings on the

merits. Whether it treats the rulings as granting the staters

motion for summary judgrment or as sunmary rulings pursuant to

Habeas Rule 4 will not affect the appealability of the issues.

(3) An appellee in a habeas case can urge

as a basis for affirmance any issue that would not expand the

relief afforded by the district court. Thus, Wilder can argue

that the Court should uphold the judgrment because of other

claims in her habeas petition. However, since success on the

Jackson issue would expand Wilder's rights, she cannot argue

that issue without cross-appealing.

(4) We cannot argue that the district court

have reached the Jackson cIaim, since it wasshould not

authorized

-2-

petition without any notice to the n:t.t;;.

url;T""t,

we can

attack the order's lack of specific AEisieO4of the record,

arguing that it is nonreviewable and should therefore be

remanded. An appellate court faced with such an inadequate

order might review the issue on the merits; therefore, we

should also argue that the issue was decided wrongly.

tAe

/ (ll Blake v. Zant and Finalitv ofrn'istriet

I

t ry ,rRule 54 (b) Provides:

DISCUSSION: ';'#;r^"

t/t1UQ. ttl$,*.*,.t

/iWf 4,'^/'

tttruQ. ha,,**

\,n

When more than one claim for relief is

presented in an action, . the

eourt may direct the entry of a final

judgment as to one or more but fewer

than aII of the claims or Parties

only upon an express determination

that there is no just reason for delay

and upon an exPress direction for the

entry of judgment.

In Blake v. zant, 73;\F.2a, 925 (IIth Cir. 1984), the court

/\

dismissed the Statf'5 /nn""I of an order granting habeas relief

\,/

because the order di-d not dispose of all claims in the petition.

The Court said "Application of rule 54 (b) to require that all

claims presented in the habeas petition be finally determined

before an appeal may lie will vindicate long-standing policies

/gdtihst piecemeal Iitigation and will not confli-ct with any

\-/

hJbeas statute, rule or policy." 737 F.2d at 928. The Court

said that the state should "move the district court to stay the

grant of the writ pending determination of the remaining claims-

If the district court, when the lack

of fjZrST\ty in its order is Pointed

out,(i,4 lrders that the Prisoner be

releAsed/pending resolution of the

remaining claims, the interlocutory

character of the order will be plainly

established. At that time, the state

could attempt to have the district court

make the necessary determinations to

render the order appealable under rule

s4 (b)

-3-

737 F.2d at 928-29. In our case, the writ was ordered issued

unless wilder was re{i6Ea within 90 days of the districtU

courtrs order. This places our case in the posture the

Blake v. Zant court considered might be appealable.

The holding and dictu:n in B1ake v. Zant accord with

the general view that RuIe 54 (b) applies to habeas proceedings

to allow appeal only upon final adjudication of all Ou10r*"

U

or final adjudication of some claims and an appropriate

determination. See, 9:g., Gray v. Swenson, 430 F.2d 9, 1I

(8th Cir. 1970). While it is not entirely c1ear, ds I noted

in my first memo, that this is the "infreguent harsh case"

where an appeal should be allowed upon determination of fewer

than all of the claims in a petition, it is certainly possible

that the Court of Appeals will a119w it. Indeed, the panel in

s/- Zant indicated its amenddb

ll,rtw r-t. Incleecl, trre Pane

4rfability to an appeal in a

\-,

si-tuation similar to ours. (ft is important to note that

the court is duty-bound to consider the jurisdiction issue

whether or not it is raised by the parties. Seel Gray v.a\

Swenson , 430 F.2d g, 1I (8th Cir. 1976))) t

r l,!

l2l Like1v Treatment dP'the Adverse Rulinqs

bv Appellate Court.

In my first memo, I expressed my opinion that the

adverse rulings on the two notice issues and the Jackson

issue would be treated by the Court of Appeals as potentially

appealable rulings on the merits. I based my opinion on the

language of the judge's order, which clearly indicated rulings

on the merits against Wilder, and on my implicit asssumption

that the court's discussion, rather than the motion pending

-4-

when the ruling was made, is determinative of the nature

of the decision. Further research gives credence to this

assumption, and indicates that the rulings will probably be

treated as rulings on the merits.

In Rubin v. United States, 488 r.2d 87 (5th Cir.

L9731, the Court held that an appeal was out of time when filed

four months after entry of an order which was "c!:arply a final

(r( )

denial of the requested relief." The Court said)-r{hen the_{

trial judge acts in a manner which clearly indicates his intention

that the act sha1I be the final one in the case, and a notation

of the act has been entered on the docket, the time to appeal

begins to run." 488 F.2d at 88 (quoted with approval in

Broussard v. Lippman , 643 F.2d 1131, 1133 (5th Cir. 1981) ) .

Although Rubin considered the finality of an order for the pur-

pose of determining the timeliness of an appeal, its analysis

seems applicable here. The time for an appeal begins to run

only when an order is appealable. Since the order in our

case "cIearly indicates Ithe judge's] intention that the act

is the final oner" it would seem to be final and appealable.

onlv

Rubin does have,I{mited application to our case, especially

A

since it speaks of the courtrs final act in the case, not

just on some issues. But its language indicates that courts

look to a court's actual discussion and holding to determine

whether an order is final.

Other cases indicate a practical

determination of the finality of orders.

Director, Department of Corrections, 434

attitude toward the

In Browder v.

-5-

u.s. 257, 265-66,

r L,

' F' l4?8/

54 un/.za 521 f rsZfif , rhe Court stared rhe somewhat obvious

principle that a srumnary determination of a habeas petition is

a final order even when it is made without an evidentiary hear-

ing and it is based on the habeas petition, the respondentts

motion to dismiss, and the state court record. The court herd

that finality was present because the district court had

discharged its duty under 28 u.s.c. 2243 to summariry hear and

G\

det{qinlne the facts. And in Schlang v. Heard, 691 F. .2d 796,\v

797-98 (5th Cir. 19821, cert. denied, 103 S. Ct. 24L9 (1983),

the court stated the generally held view that a courtrs ruling

will be treated as a grant of srunmary judgrnent when its written

findings clearly indicate that it considered matters outside

the pleadings in reaching its decision, even where it describes

its ruling as a dismissal for failure to state a claim on

which relief could be granted. See also Georgia Southern a

F. R. Co. v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., SZS f,-.Za 4g3, 496 (5tfr

I

Cir. 19671. Although Browder and Schlang are clearly distinguish-

able from our case, they do indicate that courts will consider

practical matters in determing the nature of orders and rulings.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 41 (b) provides:

Court

Unless the Et*, in its order for dismissal

otherwise sp"c'if ies, a dismissal under

this subdivision and any dismissal not

provided for in this ruIe, other than a

dismissal for lack of jurisdiction, for

improper venuer or for failure to join

a party under R 19, operates as an

ad-iudication on the merits.

(Emphasis added. )

<- Although "dismissal" in Rul-e 41 means "dismissal- of

actions" (the rule is so titled), the language lends furtherL^'*\

-6-

weight ;pi41t to the proposition that the adverse rulings

will be treated as rulings on the merits. See Keenan v.

Bennett, 613 F.2d 127 , L28-29 (5th Cir. 1980) (where not

specified otherwise, dismissal of habeas petition operated

as adjudication on the *#,6) and not as dismissal for nonex-tu/

haustion of remedies). rYus, it is likely that the district

courtr s adverse rulings will be treated as final dispositions

of those issues, since the court's discussions clearly indicate

that they are rulings on the merits.

Whether )he Court treats the rulings as grants of

b

sunmary judSlnentf for the state or as sunmary dismissals under

Habeas Rule 4 will not affect their appealability, since they

are rulings on the merits either way. See Ardoin y.. J, Ray

-TMcDermott & Co. , 64L f.2d 277 , 278 (5th Cir. 198I).

(3) Option to Argue Issues Not Considered by

District Court

Wilder is entitled to defend the judgrment on any ground

in her petition that would not expand the relief given by the

district court.

The prevailing party fray, of course,

assert in a reviewing court any ground

in suport of his judgment, whether or

not that ground was relied upon or even

considered by the trial court. ICitations

omitted.l . " [I]t is likewise settled

that the appeIlee mdy, without taking a

cross-appeal, urge in support of a decree

any matter appearing in the record,

although his argument may involve an attack

upon the reasoning of the lower court or an

insistence upon matter overlooked or ignored

by it. ..."

Williams, 3g7 U.S. 471, 475 n. 6, 25 L'Ed'2d 491Dandridge v.

-7-

tq>0

(l>(I) (quoting United States v. American Railway Express Co. r

265 U.S. 425, 435-36, 58 L.Ed. 1087 lt.924ll. This principle

.applies to habeas cases to allow argument of any issue in the

habeas petition and holds even where a district court attempts

to limit the issues to be reviewed in its certificate of probable

cause. See , 571 F.2d 762, 766

(3rd Cir. 1978) (Court of Appeals can consider any issue

previously considered by state courts and presented to habeas

court, notwithstanding fact that certificate of probable cause

was limited to one issue). See also Eyman v. Alford, 448

r.2d 306, 309 (9qh Cir. 1959); Yount v. Patton, Tl0 F-2d 956,

@rat,ffi-il2(nyT-

977 n. 4 (3rd Cir. 1985I; Houston v. 4f4lq9-q,722 g, -2d 290, 293

,A

(6th Cir. 1983). Courts apply the principle when reviewing a

grant of summary judgrment. See Liberty G1ass Co-, Inc. v-

Allstate rnsurance Co., 607 F.2d 135, 138 (5tn Cir. 1979).

Therefore, without #==-"npealingr

we can argue that the judgrment

should be affirmed on the basis of any claims in Wilderrs

petition that would not expand the relief given by the district

court.

\ The Jackson claim would probably be held to expand

A

Wilderb's relief. The district court ordered that the writ

r.{,

would issue unless she were retried within 90 days. Success

on her Jackson cIaim, however, would result in Wilder's release

931 (7th Cir. 1975), ttre /ourt ruled in an appeal from an order

I

directing renewed commitment proceedings that it could not consider

the appellee's challenge, without cross-appeal, to a statuters

without trial. In U.S. ex rel. Stachulak v. Coughlin, 520 F.2d

/ c,

-8-

constitutionality, since success on the issue would entitle the

appellee to his freedom without a renewed cormnitment proceeding.

tiI(, t , The pourt said:rl

If Stachulak were to prevail on

his contention that the statute is

unconstitutional he would be entitled

to his freedom instanter and could

not be subject to a renewed commit-

ment proceeding. It is plain there-

fore that he is not merely attempting

to support the judgment but rather to

expand his rights under the decree.

520 F.2d at 937. The facts of our case are guite similar to

those of Stachulak. Because success on the issue would result

/t0 t

;:,."',:,ffi":,x-']l";"":'::::"':.:]:nrobab1vnconsider

,o, *rU, however, consider arguing other cl-aims in

the habeas petition to support the judgrment. Arguing the

additional claims could bring useful information to the court's

attention. If the Court of Appeals felt that presentation of

additional claims would be more appropriate in the distri-ct

court, it would simply remand. see Dandridgg_ll,_witliams, 397

U.S. at 475 n. 6i Liberty Glass Co., 607 F.2d at 138.

-9-

( 4 ) Recommended Strateqv for Cross-Appeal of

Jackson Issue

The district court was authorized to rule sua sponte

on the Jackson claim. Habeas Rule 4 provides:

If it plainly appears from the face

of the petition and any exhibits annexed to

it that the petitioner is not entitled to

relief in the district court, the judge

shall make an order for its summary dismissal

and cause the petitioner to be notified.

In the civil context, a judge may be prohibited from summarily

dismissing a claim without providing notice beforehand

to the parties. But such a prohibition would probably originate

from the parties' right to notice and opportunity to be heard

in civil proceediDgs, not from the court's lack of authority to

rule on a motion not before the court. See l0A Wright and

MiIIer, Federal Practice and Procedure 52720, p. 27. In habeas

proceedings, the petitioner has no such right to notice, since

Habeas RuIe 4 allows summary dismissal of the petition. Thus,

district courts frequently dismiss habeas petitions on the

f the petitions alone. Wherer ds in our case, a habeas

court dismisses a petition after examining both the petition

and the State trial court record, the Court of Appeals will

uphold the dismissal when the record shows that the petitioner's

claims are without merit. See U.S. ex rel Bennett v. Pate,362

F.2d 89, 9I (7th Cir. 1966); Cronnon v. State of Alabama,587

F.2d 246, 249 (5th Cir. 1979); Penninston v. Housewriqht, 666

F.2d 329, 331-33 (8tfr Cir. I981), cert. denied, 456 U.S. 918

(1982). Since the Jackson claim involves only an examination

of the trial court record, see Jackson v- Virqin-la, 443 U.S.

-10-

307, 322,51 L.Ed. 2d 560, 575 (1979)("rhis tyPe of claim can

almost always be judged on the written record without need

for an evidentiary hearing" ), it would be very difficult to

convince the Appellate Court that the district court should

not have ruled sua sponte on our claim.

Howeverr w€ can attack the order on the basis that its

findings were inadequate to support the judgment. Reviewing

the evidence of Wilder's guilt, the court said:

The Court has thoroughly reviewed the record

of Wilderrs trial. Given that the Alabama Court

of Criminal Appeals set out the testimony at

Wilder's trial in its opinion, and given that this

Court finds that the evidence clearly was suffi-

cient under Jackson to convict Wilder, there is

no need for this Court to 9o beyond the Court of

Criminal Appeals' review of the evidence.

Order at 3. After summarizing the Jackson standard, it said

The evidence was sufficient for a rational

jury to find Wilder guilty. A significantff\unt

oi Lvidence indicated that ballots were ca$frln

the names of people who denied casting themYand

sufficient evidence linked wilder to those ba110ts.

Wilder picked up numerous applications, she took

them to the Persons whose votes were purportedly

"stolenr" she had access to many of the ballots,

and she was in the group that took them to Rollins

to be notarized. A jury could reasonably find

beyond a reasonable doubt that Wilder must have

filtea in the ballots herself and cast them with

the intent of voting more than once-

Order at 9. The opinion makes no other mention of the record

of Wilder's trial. It never specifically refers to any part

of the record, and never acknowledges that the witness' prior

statements were not admissable as evidence-

In Gray v. Lucas, 677 F.2d 1085 (5th Cir. L982),

- 11-

cert. denied, l03 S. Ct. 1885 (1983) the court held that the

district courtrs summary dismissal of the habeas petitioner's

claims was error where the court's opinion discussed the claims

in a conclusory manner. The district courtrs opinion said

"[I]t is the considered judgment of this court . that

every one of the petitioner's constitutional rights Ihas] been

respected in every phase of this entire case [and] tfrat the

petition . is without merit . . " In holding that the

summary manner with which the district court dismissed the

claims was improper, the court said that a district court "is

required to offer some explanation of its ruling on each ground

of retief raised. . . ." 677 F.2d at 1102. The Fifth Circuit

similarly ruled in Wer-h-l-!-9ton v. SlfieE-Iand,.673 F-2d 879

,nuuvl on Y)_

_(5th cir. Lg82), that azl-?tStrict court shotild have separately

addressed each sround #Sljref ief raised by the petitioner. The- tu I

court sa id V'

We emphasize that this does not reguire that

the court write the definitive lega1 treatise on

each point so raised; to the contrary, in many if

not most instances, no more than a sentence or two

and a citation to a case or a record reference will

enable this court to give meaningful review to the

district court's factual and legal conclusions-

. [a]n articu]ation of the court's reasons for

rejecting a habeas claim is obviously important

for stare decisis purposes, as welI as for

considerations of judicial economy on appeal.

at go7. see also whittaker v. overholse_lf I 299 F.2d 447,673 F.2d

449 (D.C.

F.2d 364

Cir. L962); U.S. ex rel Sleishter v. Bafnmiller, 250

(3rd Cir. 1957). Success on this ground would be

-L2-

difficult; but we could at the Ieast make a reasonable argument

and show the Court of Appeals that the district court was not

generally disposed favorably towards Wilder.

Although we can argue that the Court of Appeals should

remand because of the insufficiency of the findings, the

court might decide to consider the merits of the Jackson claim even

if it finds that the findings were insufficient. After the court

in Grav v. Lucas ruled that the district court's findings were

insufficient, it said

[r]he issues posed by the . claims raise

questions onty of law which do not require

fact development to resolve. Because we are

in as a good a position as the district court

to answer these inquiries, the interests of

justice indicate we should pass on them here

ind now rather than remand the cause and delay

their ultimate disPosition -

677 F.2d at I103. Because the Jackson claim similarly does not

require fact development for its resolution, the Court of Appeals

might review the Jackson claim on its merits after concluding

that the district court's findings were inadequate. Therefore,

we should fu1ly argue the Jackson claim on our cross-appeal.

The Court of Appeals wilI probably conduct an independent

review of the merits of the Jackson claim. Where the district

court,s decision is based only on the record of the state trial

and other documentary evidence, the reviewing court is not

required to give deference to its findings. See Johnson v.

llabrv, 60 2 F .2d L67 , 170 ( 8th Cir. L9791 i McFarlane v. Devounqt,

II98 (9th Cir. 1970); SuIIiV ,431 F.2d 1197,

- 13-

qq^to

665 F.2d 478, 482 (llth Cir. 1982). Thus the court should

consider de novo the question whether the evidence, excluding

the prior statements used by the prosecutor to impeach his

witnesses, was sufficient to convict I{ilder. (For a statement

of the Eleventh Circuit interpretation of the Jackson standard,

see Cosbv v. Jones, 682 F..2d I373, 1383 (llth Cir. I982).)

CONCLUSION: I recommend cross-appealing the Jackson c1aim, and

possibly arguing other claims in the petition as grounds for

affirmance. The court will probably allow our cross-appeal if

it allows the staters appeal. We can argue that the court's

findings on the Jackson claim are both insufficiently specific

to permit review, and wrong on the merits. Since the court

might review the merits even after concluding that afr. finaings .!.'C'

are insufficient, w€ should not challenge the sufficiency of

the findings without also arguing the merits.

-r4-