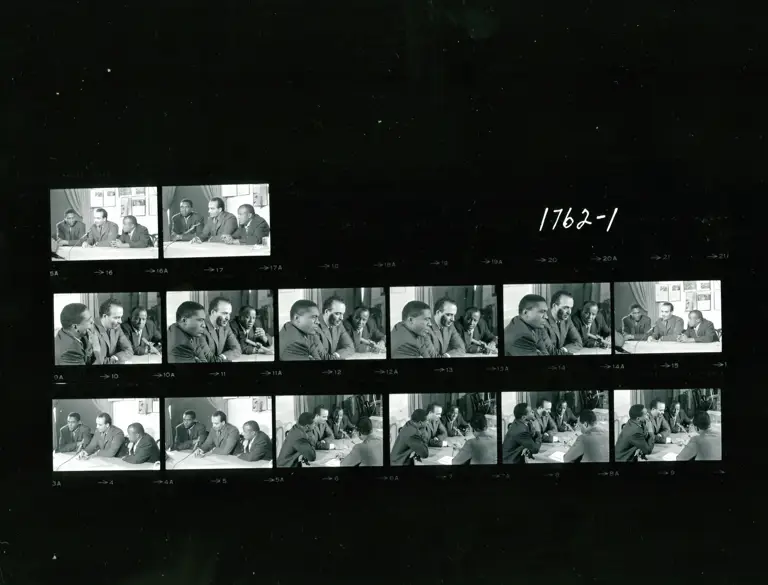

Press Conference on TV Exclusion of Black Athletes, September 1967 - 7 of 7

Photograph

January 1, 1967

Photo by News Voice International

Cite this item

-

Photograph Collection, LDF Events. Press Conference on TV Exclusion of Black Athletes, September 1967 - 7 of 7, 1967. 38075eb0-b754-ef11-a317-0022481d08e0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b85938ed-abcd-48b0-9b0b-4a5fbf8754a1/press-conference-on-tv-exclusion-of-black-athletes-september-1967-7-of-7. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

X-TIKA:Parsed-By org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser X-TIKA:Parsed-By-Full-Set org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser Content-Length 6655276 Content-Type image/jpeg