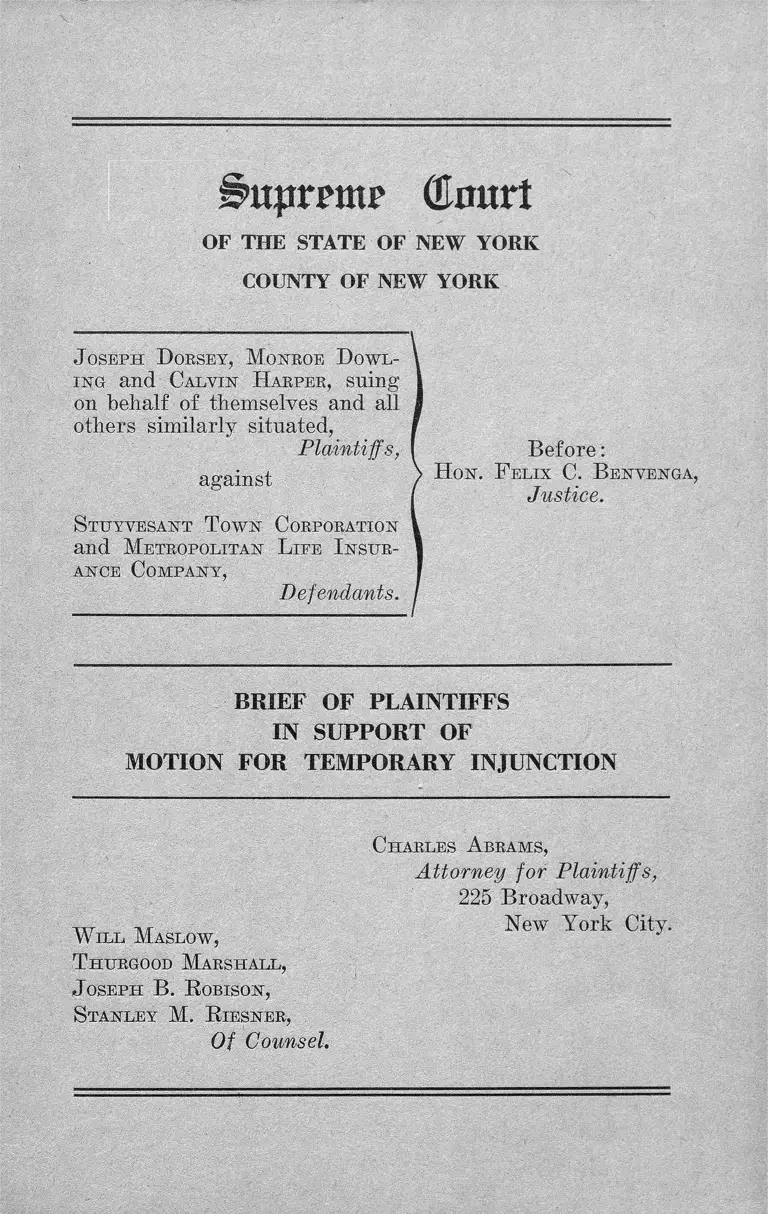

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation Brief of Plaintiffs in Support of Motion for Temporary Injunction

Public Court Documents

July 9, 1947

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation Brief of Plaintiffs in Support of Motion for Temporary Injunction, 1947. c6faf812-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b8992dd8-a366-4b86-ba03-d0a9a84e5f2f/dorsey-v-stuyvesant-town-corporation-brief-of-plaintiffs-in-support-of-motion-for-temporary-injunction. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

t t p r a n p Gkmrt

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

COUNTY OF NEW YORK

J oseph 'Dotjsey, M em os D owl

ing and Calvin Harper, suing

on behalf o f themselves and all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

against

Stuyvesant T own Corporation

and Metropolitan L ife Insur

ance Company,

Defendants.

Before:

H on. F elix C. Benvenga,

Justice.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS

IN SUPPORT OF

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY INJUNCTION

W ill Maslow,

T hurgood Marshall,

J oseph B. R obison,

Stanley M. R iesner,

Of Counsel,

Charles A brams,

Attorney for Plaintiffs,

225 Broadway,

New York City.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement .......................................................................... 1

The character of Stnyvesant Town....................... .... ..... 6

The constitutional provisions........................................ S

The statute and contract............................................ 13

Point I—The extraordinary usages to which public

powers were put affirms the public character of

Stnyvesant Town.................... 18

1. The tax power............................ 18

2. Eminent domain.................................................... 20

3. The police power.................................................. 21

Point II—The courts have restrained even private cor

porations from discriminating where they have be

come repositories of official power............................. 23

Point III—Even if Stnyvesant Town were completely

private as it contends, its very physical pattern

would bring it within the restraints of the Constitu

tion ....................................................... 30

Point IV—If the Redevelopment Companies Lav/ em

powers the Stnyvesant Town Corporation to bar

Negroes it would be unconstitutional. The Court

should, therefore, construe the law to effect a con

stitutional purpose............................... -..... -................ . 32

Point V—The Riverton project is irrelevant to the

constitutional issue here involved................................ 39

Point YrI—A. temporary injunction should be granted

to prevent irreparable damages..... .......... 40

Conclusion ....................................................................................... 42

PAGE

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

C A SE S PAGES

Adler v. Dcegan, 251 N. Y. 467........ ................................ 38

Block v. Hirsh, 256 U. S. 135............................. ............. 38

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60......................7, 33-35, 43

Clinard v. City of Winston-Salem, 217 N. C. 119—1.__ 43

Conectieut College v. Calvert, 87 Conn. 421, 88 Atl. 633 21

In re Drummond Wren, 4 D. L. B. 674......................44, 45

In re Edward J. Jeffries Housing Project, 306 Mich.

Glover v. City of Atlanta, 96 S. E. 562.......................... 43

Hardin v. City of Atlanta, 147 Ga. 248, 93 S. E. 401... 43

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668...................................... 7

Harris v. City of Louisville, 165 Ky. 559, 177 S. W. 472 43

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 IT. S. 81................................. 44

Hopkins v. City of Richmond, 117 Va. 692, 86 S. E. 139— 43

Irvine v. City of Clifton Forge, 97 S. E. 310.............. 43

Kennett v. Chambers, 55 IT. S. (14 How.) 38.................... 45

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. 2d 212...7, 27, 28

Liberty Annex v. City of Dallas, 289 S. W. 1067...... .... 43

Madden v. Queens County Jockey Club, 296 N. Y. 249... 29

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501........................... 30-31, 37

Murray v. LaGuardia, 291 N. Y. 320.............. 8, 9,11,13, 32

New York City Housing Authority v. Muller, 270 N. Y.

333 .............:............ ................................................21,29,32

Nixon v. Condon, 286 IT. S. 73.......................... - .........7, 8, 24

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418.................. -................. 7,9,11

I l l

People ex rel. Durham v. LaFetra, 230 N. Y. 429....... 38

Pratt v. LaGuardia, 182 Mise. 462, aff’d 268 A. D. 973,

leave to appeal denied 294 N. Y. 842.............. 2,12,13, 36

Shelley v. Kramer, 15 IT. S. Law Week 3478................ 42

Sipes v. McGhee, 15 17. S. Law Week 3478.................... 42

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649.................. 7,8,22,24,25

Steele v. Louisville R. Co., 323 IT. S. 192.......7, 25, 26, 27, 28

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IT. S. 303.................. 34-35

Stuyvesant Town Corporation, 183 Mise. 662, 51 N. Y.

S'. 2d 19.................................. ....................................... 20

University of Southern California v. Robbins, 37 Pae.

PAGES

2d 163............. ......... ................... .............. ...... ............... 21.

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 IT. S. 339..................................... 35

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 1.18 Ik S. 356................................. 38

STATUTES AND MISCELLANEOUS

Abrams, Charles, “ The Future of Housing”................. 42

Abrams, Charles, “Race Bias in Housing ’.................. 42

51 Corpus Juris... .............................................................. 30

Kalian, Validity of Anti-Negro Restrictive Covenants,

12 U. of Chi. L. Rev. 198................. ,.......................... 42

Local Law 45, 1947........................................................... 40

McGovney, Racial Residential Segregation by State

Court Enforcement of Restrictive Agreements, 33

Calif. L. Rev. 5... .............................. ....... :.................... 42

McQuillan, Municipal Corporations.............................. 29

IV

Myrdal, An American Dilemma....................................... 42

N. T. City Admin. Code, Section J 41-1.2.................. 4, 40

N. Y. City Charter.................................................... ........ 32

N. Y. State Constitution............................. 3, 8,11,16,19, 39

N. Y. Public Housing Law............................................. 29

Redevelopment Companies Law, McKinney, Ilneon-

solid. Laws, Sections 3401-3426.........6, 9,11,12,13-1.7, 32

PAGES

Report, 1944 Annual Conference of Race Relations

Advisors ........................................................................ 5

Senate Hearings, Senate Special Committee on Post

war Economic Planning, 79th Cong., 1st Sess., part

6 ......................................................... .............................. 4

Senate Hearings before Committee on Banking and

Currency, 79th. Cong., on S. 1592................................ . 4

Tanzer, New York City Charter..... .............................. 32

United Nations Charter.................................................... 45

United States Constitution........................... 3, 7, 9, 23, 28, 30

§>itpmttp (Eoart

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

COUNTY OF NEW YORK

J oseph D orsey, Monroe D owl

ing and Calvin Harper, suing

on behalf of themselves and all

others similar!}7 situated,

Plaintiffs,

against

Stuyvesant T own Corporation

and Metropolitan L ire I nsur

ance Company,

Defendants.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS IN SUPPORT OF

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY INJUNCTION

Statement *

The three plaintiffs are Negro war veterans. They sue

to enjoin the two defendants from withholding or denying

to them and others similarly situated any of the dwelling

units in the Stuyvesant Town project solely because of

their race or color. They allege that they have applied

for apartments in Stuyvesant Town but that the defend

ants do not intend to rent to Negroes. Their applications,

they say, therefore are doomed in advance. In view of

the public features of the project, the public aid and powers

* This brief is also filed in behalf of the American Jewish Congress, the

American Civil Liberties Union and the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People who indorse the views expressed herein.

2

that made it possible, and the fact that it is subject to

public controls throughout the life of its tax exemption,

they assert that an obligation rests upon the defendants

to extend to them the equal protection of the laws.

The defendants do not dispute that their policy is to bar

their accommodations to Negroes. They have, in fact,

gone out of their way to admit it orally and in writing.

Their current explanation is more in the nature of de

murrer than denial. The record of their position on the

question may be stated in three phases.

Phase I goes back to 1943 when the Chairman of the

Board of Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. asserted that

no Negroes would be allowed in the project. Replying to

affidavits in a taxpayer’s action citing his statements, he

admitted his position, but said that defendants’ directors

had “ thus far not adopted any renting policy and that

they will have no occasion to do so until the project ap

proaches completion” (position summarized in Opinion of

Judge Shientag in Pratt v. LaGuardia, 182 Misc. 462

[1944], aff’d 268 A. D. 973, leave to appeal denied, 294

N. Y. 842). Because there was no final renting policy and

the project was not yet under way, a suit to enjoin the

discrimination was then held to be premature.

Phase II is concerned with the period of June, 1946,

when in response to a letter from the American Civil Lib

erties Committee asking the following question: “Are

there restrictions as to race, color, religion of prospective

tenants?” , George Gove, Vice-President of Stuyvesant

Town Corporation, stated “ * * * in conformity with public

announcement made when the plans for Stuyvesant Town

were first formulated in cooperation with the City, pro

vision has not been made for occupancy by Negro fami

lies” (Letters of Foster and Gove annexed to moving pa

pers).

3

Phase III is concerned with the period immediately pre

ceding this action. Shad Polier, vice-president of the

American Jewish Congress, spoke with George Gove on

June 20, 1947. He read Mr. Gove the letter of a year be

fore to the Civil Liberties Committee. He said that he

had heard that a change in that policy was being contem

plated and that Negro applicants were being interviewed.

Mr. Gove stated that despite the interviews “ there was no

change in the Corporation’s policy as publicly announced

and as summarized in the letter to Mr. Poster” (Affidavit

of Polier). Mr. Polier asked Mr. Gove what the Corpora

tion would do, should Negroes meet “ the requirements

established by the Corporation with respect to character,

stability, manner, appearance and similar criteria.” Mr.

Gove “ stated that, nevertheless, unless there should be a

change in policy—and none was being contemplated—there

would simply be no renting to Negroes.”

Mr. Gove’s answering affidavit does not deny any of

these assertions nor does it deny the policy as set forth in

the letter of June 26, 1946 to the Civil Liberties Commit

tee. The only reference to Mr. Polier’s conversation and

to the letter to the Civil Liberties Committee is an at

tempted justification of the discriminatory policy on the

ground that the presence of objectionable persons might

“ endanger the economic success of the enterprise. This

right of selection by the management cannot be impaired

if due regard is to be had for the rights of the policy

holders of Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and

without violating the rights of Metropolitan Life Insur

ance Company and Stuyvesant Town Corporation under

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States and under Article I, Section 6 of the

Constitution of the State of New York.”

Mr. Gove insists that there is no limitation either by

contract or statute upon the defendants’ absolute right to

refuse accommodations to whomever they choose.

The issue of discrimination is thus clearly drawn and

the question presented directly for the first time*.

4

Have the defendants the right to refuse the plaintiffs,

and others similarly situated, the accommodations in Stuy-

vesant Town solely because of the plaintiffs’ race or color!

This is the question to be decided.

Resolution of the issue entails crucial consequences be

yond the project’s boundaries. Urban redevelopment laws

had been enacted in 20 states by the close of 1945 (see

Senate Hearings on S. 1592, before the Committee on

Banking and Currency, 79th Congress, pp. 485-524). With

39 percent of the dwellings in the United States substand

ard (see Statement of John B. Blandford, Jr., former

National Housing Administrator, at Hearings before the

Subcommittee on Housing and Urban Redevelopment of

the Senate Special Committee on Postwar Economic Pol

icy and Planning, 79th Congress, 1st session, part 6, Jan

uary 9, 1945, pp. 1233-37) urban redevelopment has

become a principal device for the replanning and rebuild

ing of our extensive slum areas throughout the country

and for replacing them with new neighborhoods. In the

process, it is inevitable that millions of people will be

moved from their old neighborhoods and the racial and

social patterns of our cities will be recast. In the new

areas we shall face the choice either of isolating minority

groups into segregated areas or creating new neighbor

hoods in which educational processes shall have a chance

of functioning toward interracial harmony. The local or

dinance barring discrimination in City projects applies

neither to Stuyvesant Town nor to any other project out

side of New York City (Admin. Code, Sec. J41-1.2).

If the new neighborhood patterns of New York State

and the United States are to be based on the theory of

segregation, segregation in neighborhood schools, in play

grounds, in shopping centers, in other public facilities

will result. If the nation’s neighborhoods are to be marked

off into areas for the exclusive and the excluded, the in

voluntary ghetto will have become an unalterable Ameri

can institution. For, once the racial composition of the

5

new neighborhoods is fixed, they cannot be easily changed,

particularly if they are as rigidly controlled as Stuyvesant

Town would be with all the freedom from public inter

ference it asserts it has.

Public housing projects have made great headway in re

establishing the pattern of heterogeneous occupancy in

newly-created neighborhoods and 325 of the 622 projects

throughout the nation now have mixed occupancy (see

1944 Annual Conference of Racial Relations Advisers, “Ex

perience in Public Housing Projects Jointly Occupied by

Negro, White, and Other Tenants”, p. 4). Every federal

and state-aided project in New York City has mixed oc

cupancy. The threats to the defendants’ claimed property

rights rest upon the mistaken notion that Negroes per se

cause a white exodus, for they have mistakenly applied the

theory of small scattered private ownerships to a large

self-contained area that creates its own environment. The

pattern of infiltration followed by inundation that takes

place in the former has no application to a controlled proj

ect such as Stuyvesant Town. Every instance of mixed

occupancy in the United States lias substantiated this prop

osition, including defense projects built for higher rent

tenancy (ibid, testimonials to successful mixed occupancy

in projects in Chicago, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Pitts

burgh, Los Angeles, Seattle, etc., pp. 8-49). The fear of

an invasion of defendants’ property rights rests therefore

upon an illusion.

The defendants simply choose to reverse the policy of

heterogeneous tenancy in publicly-aided undertakings and

claim their right to do so as “private” owners of a “private”

project. The plaintiffs, however, assert that the project

is endowed with certain public attributes which impose

upon its sponsors the obligation to extend the equal pro

tection of the laws to the citizens whose powers and funds

have made the project possible. The character of the

“private” undertaking therefore must be carefully analyzed.

6

The character of Stuyvesant Town

Stuyvesant Town is not merely a composite of buildings.

In many respects it is more like a principality. It consists

of 18 city blocks consisting of more than 2y2 million square

feet of land of which almost 750,000 square feet were

originally public streets. These are now enclosed and in

cluded in the site (see Chart II appended to the contract

between the City, Stuyvesant Town and Metropolitan Life

Insurance Co.). Within the enclosure will live a popula

tion of 24,000, equal to the population of one-quarter of

one of our smaller states. It will be larger in population

than 61,000 communities in the whole country and smaller

than only 400. It spans four avenues of narrow Manhattan

Island, cutting off traffic on two avenues completely. It

will have no public parks, no schools, libraries, fire, policing

or sanitation facilities. Existing public schools, a limited

dividend corporation and other public property were

demolished and the land sold to the Stuyvesant Town Cor

poration. All the streets in the area will be marked

“private” . There will be signs on those streets at their

intersections with public streets giving notice to the public

that these streets are “private” (see Sec. 211 of contract

between City, Stuyvesant Town and Metropolitan).

This strange, novel undertaking is presumably authorized

under the Redevelopment Companies Law (McKinney,

Unconsol. Laws, Secs. 3401-3426). The project, however,

cannot exist without the provision of new schools for the

children in the area, without policing and fire protection,

without welfare facilities, without the aid of the vast net

work of municipal facilities which surround the area around

the project and convert it into a community.

The very privacy and exclusiveness which the project’s

sponsors sought for it necessitated various controls. This

was no secession from the community. These were no

ordinary apartment houses differing from others only in

mass and quantity. The new development was in effect a

7

satellite city over which the public exercised legislative

and contractual controls. The wisdom of the undertaking

and the adequacy of the controls are not in issue. What

is in issue is that the whole legislative and contractual pat

tern clearly evidences an intention to confer an agency

upon the Stuyvesant Town Corporation to carry out city

and state duties—in slum clearance, in urban redevelop

ment, in replanning, in housing. To achieve these public

purposes the City gave up much and the defendants sub

mitted themselves, in return, to public regulation. The City

condemned the property for the companies. It turned

over streets equal to 19 per cent of the area. It supplied

vast facilities. It gave tax exemption on the improve

ments. The residents of the area gave up much, too. In a

period of intense shortage they were moved out to other

slums where many of them were forced to overcrowd. The

purpose, however, was public and private convenience had

to yield to the larger public interest. That public interest,

however, still acts as the check-rein to which the project

is bridled.

The law is clear that the state itself or its subdivisions

may not deny the use of public facilities to any individual

solely because of his race, color or creed {14th Amendment;

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418; Buchanan v. Worley, 245

IL S. 60; Harmon v. Tyler, 273 IT. S. 668; In re Edward J.

Jeffries Housing Project, 306 Mich. 638). Schools, parks,

public auditoriums, public hospitals and public housing, if

provided, must be provided for all on an equal basis without

distinction as to race or color.

The restraints that bind the state and its subdivisions

also bind those agencies to whom the state’s power has

been delegated {Nixon v. Condon, 286 IT. S. 73; Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U. S. 649; Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library,

149 F. 2d 212; Steele v. Louisville R. Co., 323 IT. S. 192).

The question is not whether the corporation is public or

private but whether it is operating as a representative

of the City in discharge of the City’s authority,: whether

the Board’s managers are “ representatives of the state

8

to such an extent and in such a sense that the great re

straints of the constitution set limits to their action” (Nixon

v .Condon and Smith v. Allwright, supra). The issue, there

fore, as clearly framed by the Court, involves a considera

tion of (1) the constitutional provisions under which the

project is authorized, (2) the enabling statute, (3) the

contract between the City and the defendants.

The constitutional provisions

The constitutional questions have been resolved in part

by Murray v. LaGuardia (291 N. Y. 320). The constitu

tional authorization derives from the clause providing:

“ Subject to the provisions of this article, the legis

lature may provide in such manner, by such means and

upon such terms and conditions as it may prescribe

for low rent housing for persons of low income as de

fined by law, or for the clearance, replanning, recon

struction and rehabilitation of substandard and in

sanitary areas, or for both such purposes, and for

recreational and other facilities incidental or appurte

nant thereto” * (Article XVIII, Sec. 1).

It should be noted that the purposes are in the alternative,

but that the second alternative consists of five inseparable

components, i.e. clearance, replanning, reconstruction, re

habilitation, and recreational and other facilities incidental

and appurtenant thereto. If the Constitutional Conven

tion had intended clearance alone to be a public purpose,

presumably it would not have coupled the other purposes

with it. Manifestly, the legislature knew that clearance

could be accommplished by an earthquake, a bombardment

or a fire. It was the replanning of the area, its reconstruc

tion and its rehabilitation into a completed work that was

intended as the public use for which the vast benefits, to

redevelopment companies was authorized. As Judge Lewis

* All emphasis throughout this brief is supplied except where it is indi

cated that the emphasis appeared in the original quotation.

9

said, the other purpose was “ to bring about the clearance

and rehabilitation of substandard areas as a means to

protect public health and morals.” The rehabilitation, by

the statute, has to be by supplying housing in place of the

slums (Sec. 14). The incidents of the public purpose is

the housing. The cost of that housing is contributed to by

every taxpayer, white and black. The statute does not

say that the housing shall be for whites only. As our

Court of Appeals said in People v. King, supra,

“ It is not necessary, at this day, to enter into any

argument to prove that the clause in the Bill of Bights

that no person shall ‘be deprived of life, liberty or

property without due process of law’ (Const, Art. 1,

§ 6), is to have a large and liberal interpretation, and

that the fundamental principle of free government,

expressed in these words, protects not only life, lib

erty and property, in a strict and technical sense,

against unlawful invasion by the government, in the

exertion of governmental power in any of its de

partments, but also protects every essential incident

to the enjoyment of those rights.”

The defendants seek to read into Murray v. LaGuardia,

the holding that once the clearance of the slum has been

accomplished they are as free from any restraints upon

their conduct as any private landlord. That is sustained

neither by Judge Lewis’ opinion nor by statute. The

Murray case was brought by 18 owners within the Stuy-

vesant Town area to enjoin the defendants from proceed

ing with the project. The petition alleged, among other

things, that the plaintiffs would be deprived of their prop

erty without due process of law and “allows the condem

nation of private property for the benefit of a private cor

poration and not for public use” (Petition, Sec. 27).

“ Condemnation” said the petition, “would cause the plain

tiffs irreparable injury.” It was to this point that the

Court of Appeals addressed itself saying that “If upon

completion of the project the public good is enhanced, it

does not matter that private interests may be benefited.”

10

The Court said, referring to the exercise of eminent do

main and the tax exemption provisions “ it is thus made

clear that such tax exemption, which as we have seen, is

limited to the value of improvements made within the area,

cannot occur until the project itself—the work of rede

velopment and rehabilitation within the substandard area

has been completed and the public purpose for which the

project was designed has been accomplished.”

Judge Lewis used the term “public purpose” in the emi

nent domain sense. It is clear that he did not mean that

thereafter there were no other public purposes to be

performed, for the statute and the certificate of incorpo

ration and the contract and the whole formula from begin

ning to end are replete with public purposes that weave

in and through the whole transaction. These include not

only sound neighborhood replanning and sound redevel

opment of the area but provision and maintenance of

adequate safe and sanitary housing accommodations.

Completion of the project by the statute itself means com

pletion of “a specific work or improvement to effectuate

all or any part of a plan including lands, buildings and

improvements acquired, owned, constructed, managed or

operated in an area by a redevelopment company providing

dwelling accommodations pursuant to this act and such

business, commercial, cultural or recreational facilities ap

purtenant thereto as may be approved pursuant to section

fifteen of this act.” *

The public use as clearly held by Judge Lewis included

not only reconstruction of the area but the continued oper

ation of the project in the public welfare. When the re

construction was accomplished, new rights and obligations

were set up which in 1943 the Court of Appeals was not

called upon to decide. What is involved today is whether

the product of the “ cooperation between municipal govern

* Completion o f the project is defined differently in the contract from the

statute. Completion o f the project under the contract means the date of

actual completion or three years and sixty days after certification by the

Comptroller that materials and labor are available.

11

ment and private capital to the end that substandard, in

sanitary areas in our urban communities may be rehabili

tated” (Murray v. LaGuardia, p. 832) is now completely

divested of public interest.* This would be a preposterous

interpretation. As the court pointed out in the sentence

following its allusion to public purpose, “ It should be added

that during the period of tax exemption the statute (Sec.

16) makes it unlawful for the redevelopment company ‘to

change or modify any feature of a project’ without the

approval of the municipal planning commission, except by

a three-quarters vote of the local legislative body.”

During the period of such tax exemption the redevelop

ment company “ shall not have power to sell any project

without the consent of the local legislative body” (Sec.

23). However, whether the housing be a distinct public

function under the statute or be only an incident of the

slum clearance that has already been “accomplished” the

plaintiffs are entitled to benefit equally with other citizens

{People v. King, supra).

That there was a continuity rather than a cessation of

the public purpose, is further suggested by the Court’s

statement that

“ The People by the adoption of article XVIII of

the State Constitution, and the Legislature, by the

enactment of the Redevelopment Companies Law, have

recognized that the sinister effect of substandard, in

sanitary areas, wherever slums exist, exerts a malign

influence upon the community at large and tints justi

fies public control and corrective measures. The cor

rective statute with which this proceeding is concerned

The Courts are liberal in upholding the use o f eminent domain. It has

been conferred even upon private companies such as irrigation and drainage

companies, railroads, other public utilities and cemetery corporations The

more rigid definition of public use, i.e., use by the public, has now been aban

doned and even pub he benefit today authorizes the condemnation power But

public use from the standpoint o f eminent domain is a far cry from dis

crimination m the undertaking o f a “public use” . The situation might be

compared to a utility company which exercises the eminent domain power

or may have it exercised on its behalf. What determines its actions in regard

to discrimination is not the considerations underlying the use o f the eminent

nature of its activities and * *

12

is an effort by the Legislature to promote co-operation

between municipal government and private capital to

the end that substandard, insanitary areas in our urban

communities may be rehabilitated.”

The reference to control; cooperation between municipal

government and private capital; and to the word rehabili

tated (not cleared) indicate that there was a public pur

pose in the continued operation of the project as well as in

the clearance of the slum and the construction of the build

ings.

Mr. Robert Moses confirms this for he states in an affi

davit which Metropolitan relied upon and filed in the Pratt

case, as follows:

“ I was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention

of 1938 and took a lively interest in the housing article

proposed by that Convention. After its adoption I was

appointed a member of the Mayor’s Committee to

work on legislation to make the article effective. It

soon became apparent that all present and prospective

federal, state and municipal loans and grants for pub

lic housing, including funds in hand and those which

might be expected over a period of several years after

the war, could not possibly accomplish more than 10

percent of the problem of rehabilitation in this City.

It also became apparent that, apart from the difficulty

of obtaining huge direct subsidies for public housing,

it would be wholly undesirable to have a large pro

portion of the entire city population living in superior

subsidized quarters at rentals one-half to one-third of

those charged by private enterprise, at the expense of

hundreds of thousands of people enjoying slightly

higher incomes but living in altogether inferior apart

ments.

For these reasons the Redevelopment Companies

Law was framed as an effort to enlist private capital

for slum clearance and neighborhood rehabilitation.”

(See Record on Appeal, Pratt v. LaGuardia, p. 87.)

It was thus conceded that the new housing was for the

benefit of the thousands of people enjoying slightly higher

incomes than those eligible for public housing. It was the

housing as well as the clearance that constituted the public

purpose.

Finally, in passing upon whether the issue of discrimina

tion (the third ground) was considered in the Murray case,

Judge Shientag said:

“ The third ground of objection was not presented

in any form to the Court of Appeals; it was not re

ferred to in any of the briefs. * * * The opinion was

concerned almost entirely with the question of the

constitutionality of the Redevelopment Companies

Law and the legality of the project sought to be under

taken pursuant to that statute. * # # As the defendants

forcefully point out in their briefs, Stuyvesant will

have to perform its contract with the City in obedience

to the fundamental law of the State and of the United

States. If it adopts an illegal renting policy any per

son thereby aggrieved will have his remedy in the

courts.” (Pratt v. LaGuardia, supra.)

13

The statute and contract

If there is any doubt as to the public nature of the

completed operation, that doubt should be resolved by a

reading of the enabling statute. Section II of the statute

declares:

“ that there is not in such areas a sufficient supply of

adequate, safe and sanitary dwelling accommodations

properly planned and relating to public facilities;

# % m # # m

that modern standards of urban life require that hous

ing be related to adequate and convenient public facili

ties ; ̂ # #

that the public interest requires the clearance, re

planning, reconstruction and neighborhood rehabilita

tion of such substandard and insanitary areas together

with adequate provision for recreational and other

facilities;

14

that in order to protect the sources of public revenues,

it is necessary to modernise the physical plan and con

ditions of urban life;

# # # # # #

that these conditions cannot be remedied by the ordi

nary operations of private enterprise;

*= # * * =* *

that provision must be made to encourage the invest

ment of funds in corporations engaged in providing

redevelopment facilities to be constructed according

to the requirements of city planning and in effectuation

of official city plans and regulated by law as to profits,

dividends and disposition of their property or fran

chises; * # & # * *

that provision must also be made for the acquisition

for such corporations at fair prices of real property

required for such purposes in substandard areas and

for public assistance of such corporations by the grant

ing of partial tax exemption;

# # # # # *

that the cooperation of the state and its subdivisions

is necessary to accomplish such purposes;

# # # # # #

that the clearance, replanning and reconstruction re

habilitation and modernization of substandard, and in

sanitary areas and the provisions of adequate, safe,

sanitary and properly planned housing accommoda

tions in effectuation of official city plans by such cor

porations in these areas are public uses and purposes

for which private property may be acquired for such

corporations and partial tax exemption granted;

* # # # # #

that these conditions require the creation of the

agencies, instrumentalities and corporations herein

after prescribed for the purpose of attaining the ends

herein recited; # # # % * #

the necessity in the public interest for the provisions

hereinafter enacted is hereby declared as a matter of

legislative determination. ”

15

The statute then defines the nature of a redevelopment

company by requiring in the Certificate of Incorporation

. “a declaration that the redevelopment company has been

organized to serve a public purpose and that it shall be and,

remain subject to the supervision and control of the super

vising agency except as provided in this act, so long as this

act remains applicable to any project of the redevelopment

company; that all real and personal property acquired by

it and all structures erected by it shall he deemed to be

acquired or created for the promotion of the purposes of

this act” (Sec. 4). Would it not be preposterous to assume

that a corporation that binds itself to remain subject to

the supervision and control of the supervising agency and

whose structures erected by it are created to promote the

numerous public purposes above stated, can escape its

public obligations to extend the equal protection of the

laws—and do it with the acquiescence or consent of the

municipal agency that controls it!

If the defendants’ contention is correct, i.e., that follow

ing clearance there is no longer any public purpose and

no longer any public obligation in connection with the

ownership and operation of the project, the certificate

of incorporation becomes meaningless. The continuing con

trol also becomes meaningless.

The whole formula contained in the act is shaped to

protect the public interest in the continued operation of the

undertaking:

(1) the project cannot be sold except as permitted by

law (Sec. 23).

(2) profits are limited to 6 percent for interest and

amortization (Sec. 8).

(3) a supervising agency is set up which must con

sent to the method of incorporation, to the method of

financing, to the use of the project (Secs. 5 and 15).

(4) the City’s approval must be obtained to any

modification of the project (Sec. 15).

16

(5) the project must be designed and used primarily

for housing purposes (Sec. 14).

(6) upon dissolution, any cash surplus belongs to the

City (Sec. 24).

(7) the rents must be regulated and any increases

must have the approval of the City (Sec. 15 and See.

307 of contract).

(8) rigid controls are imposed over the financing

of the corporation (Secs. 9, 10, 11 and 12).

(9) preliminary approval of a plan or a project is

provided for (Sec. 15).

(10) the state, municipalities and all public bodies

and public officials are authorized to sell, lease or

transfer property to a redevelopment company and

hold its stock, income debentures or other securities,

secured, or unsecured (Sec. 17).

(11) the planning commission and the supervising

agency are empowered to make rules and regulations

to carry out their powers and duties pursuant to the

act and to effectuate the purposes thereof (Sec. 15).

If this urban redevelopment company, this chameleonl'ike

creature that freely alters its shape from a public to private

instrumentality is at this moment private, its continued

tax exemption and other benefits would be in violation of

Article 8, Section 1, of the Constitution. It is more logical

to assume that its functions are still public, with all the

restraints applicable to the exercise of such public func

tions.

It would he idle to assume that these regulations had

no purpose. If clearance were the only “public purpose”

there would have been no reason for the statute requiring

the construction of housing. If clearance and the construc

tion of housing were the purpose with nothing more, there

would have been no reason for the continued regulation

17

of profits, limitation upon rents, restrictions on sale, finan

cial supervision, visitation by the Controller and the numer

ous other regulations that weave through the statute.

Finally, if the intention were not “ cooperation between

municipal government and private capital” in the rehabili

tation of the area and its continued operation in the gen

eral interest, there would have been no purpose to the

payment of the cash surplus to the City upon dissolution

of the corporation.

That its obligations are public is clear from the condi

tions under which tax exemption is given and the circum

stances under which public regulation ends. Section 26

of the statute provides that the redevelopment company

receiving tax exemption may elect to pay the municipality

the total of all accrued taxes with interest. Thereupon

the tax exemption ceases and Section 24 dealing with dis

solution applies. It is only after the payment of the arrears

of taxes that the company is free of regulation. By the

contract (Sec. 601),. however, the City and the defendants

agreed that the taxes could not be paid up for a period of

at least five years from the completion of the project.

By Section 702 all supervision and restrictions cease after

payment of the accrued taxes, except the covenants against

change in the plan of the project. It was thus the inten

tion of the law, as well as of the contract, that the grant

of tax exemption be linked to the continued control by

the City of the project and the continuity of the public

obligations to the citizenry. If that obligation ceases at

any time, one thing is clear: it does not cease during the

period when the City is granting the corporation $2,000,000

annually in the form of a tax subvention,

18

POINT I • ! .

The extraordinary usages to which public powers

were put affirm the public character of Stuyvesant

Town.

Not one, hut all three of the trinity of public powers were

or are being utilized in this project in a unique and un

precedented manner.

1. The Tax Power.

The cost of the project is conceded to be 90 million dol

lars (Gove affidavit, paragraph 20). The cost of the land

was about 17 million dollars (see application of Stuyvesant

Town Corporation to New York Board of Estimate for

an increase in rent, dated April 24, 1947). The total tax

exemption over a 25-year period granted to Stuyvesant

Town Corporation is thus about 3 percent on the improve

ment cost (90-17 millions) or well over 50 million dollars,

which is about three times the cost of the land. There is no

limitation upon the income group that may occupy the

project in the statute or in the contract though the inten

tion as set forth by Mr. Moses is to house a low-income

group. Two conclusions are suggested by the calculation:

(1) Here was a benefit resulting from a vast tax exemption

which the City desired its citizens to have. Largely as

the result of the exemption, housing, precious housing, was

being made available at considerably less than market

value. All citizens, not a select few, were entitled to reap

that benefit. The defendants, however, would say that

they want only the Caucasians in our city to have it and

they and they alone have the right to determine who shall

be the beneficiaries. This, the plaintiffs argue, deprives

the plaintiffs of the law’s equal protection. (2) If it was the

intention of the statute or the contract to clear the slum,

and nothing more, after which the project was to revert

to its private status, the City could have been 33 million

19

dollars better off by taking the land and presenting it as

a gift to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company on

the condition only that it build a project. It should be

remembered that Metropolitan has built Parkchester on

the extremities of the City on land for which it paid. In

fact, simultaneously with the building of Stuyvesant Town,

it is building Cooper Village, on land for which it paid,

and which is not tax-exempt. In other words, it is reason

able to assume that if the City wanted only the slum

cleared and was not interested in housing for its citizens,

it could have written down the land cost or even •written it

off completely and turned it over to Metropolitan. That

the City has contributed more than half of the cost in tax

exemption is proof of the cooperative and public nature of

the undertaking and of the additional public benefits it

expected from the undertaking. The public dividend was

in the form of lower rental apartments, not necessarily

“ low-rent housing” as used in the Constitution. This must

be made available not merely to Metropolitan’s selected

clientele. If, for example, Metropolitan had announced

that the project’s facilities would be for Metropolitan’s ex

ecutives only, the people would never have granted the tax

exemption, the streets and the condemnation benefits nor

would the court have sanctioned the grant. The presump

tion was that there was to be good housing for the people.

Many citizens have eagerly looked forward to the oppor

tunity of getting one of these low-priced apartments.

Metropolitan may not therefore act arbitrarily in the se

lection of tenants as it contends, for its conduct must be

reasonably related to the duties which it has assumed when

it accepted the benefits of the public powers and aid. That

duty carries with it an undertaking not to discriminate

arbitrarily because of race or color. If it wishes to win

release from the contract’s and the law’s restraints, it

might do so perhaps by paying off the equivalent of the

tax exemption five years from the completion date. But

until then, and so long as it receives benefits, it must as

sume all the corresponding obligations attaching to those

benefits.

20

2. Eminent Domain.

The grant of eminent domain is also unique. The City

is permitted to acquire the property for Metropolitan Life

Insurance Company, a privilege not shared by other cor

porations engaged in performing public purposes. Real

property in the area needed or even convenient may be

acquired. Property devoted to a public use may be ac

quired, too, notwithstanding that such property may pre

viously have been acquired by condemnation or may be

owned by a public utility corporation. Public property

may be sold to Metropolitan without any requirement of

public bidding. Increase in value due to assembly or re

construction is not to be considered in making the award.

Moreover, the use for which property is acquired for re

development companies becomes a “ superior public use” .

Presumably, therefore, should the City ever wish to con

demn Stuyvesant Town for another public use, a serious

question would arise as to whether the State might not

have to declare the future use to be a “ superior, superior

public use”. There is even a question as to whether it

could reacquire the land at all for ordinary public uses.

In any event, so public is the use, i.e., the clearance, re

development and reconstruction of the project, that schools,

parks, streets and other simple public uses may be taken

for this extraordinary and superior public undertaking.

In fact, a. limited dividend corporation in the area for

families of low income was actually condemned (Stuyvesant

Housing Corporation v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation, 183

Misc. 662, 51 N. Y. S. 2d 19). Thus the Legislature and the

City conferred the benefits of a condemnation power

greater in some respects than those granted to its own

housing authority, a city agency also engaged in slum clear

ance. The use was considered more public than public

hospitals, courts, water supply. Yet defendants now con

tend that the use has reverted not only to a private use,

but to a “ superior private” use, more immune from public

obligations than even a wholly-owned company town.

21

3. The Police Power.

Streets equalling 19 percent of the area have been turned

over to Stuyvesant Town Corporation and the police power

normally possessed by the municipality over these streets

is now under the corporation’s control. Responsibility for

accidents is assumed by the redevelopment company. The

disposition of public property is not what normally takes

place in the ordinary private large scale development.

There, streets are dedicated to the City; here, the streets

are dedicated by the City to the corporation. If the defend

ants are correct in their contention, no one has a right to

enter those streets except the Comptroller (See. 506 of

contract). If Negroes have no equal rights to receive ac

commodations, they have no rights to walk upon the streets

either. This could not have been the intent of the Legisla

ture. The only inferences which can be drawn from this

unusual arrangement is that the streets, though owned by

the company, are operated under a public trust for a public

use. It need not be for the use of the whole public any

more than a public housing project (New York City Hous

ing Authority v. Muller, 270 N. Y. 333), or a poorhouse,

but it cannot be employed for a special class or for a

corporation that discriminates as to race (Connecticut

College v. Calvert, 87 Conn. 421, 88 Atl. 633 [1913]; Uni

versity of Southern California v. Bottoms, 37 Pae. 2nd 163

[Cal. App. 1934]).* By undertaking to carry out these

extraordinary public purposes, the defendants have assumed

the public obligations to abide by the same restraints that

bound the public grantor of the powers and benefits.**

* In Connecticut College v. Calvert, supra, an effort was made to condemn

land for the benefit o f a privately-owned college. There was no evidence,

however, that the college was prohibited from rejecting applicants for racial

or religious reasons. The Court consequently felt compelled to deny the

benefits o f the eminent domain power. University o f Southern California v.

Robbins, supra, was a similar proceeding. There, the Court upheld exercise

o f the power o f eminent domain, but only after satisfying itself that the

charter of the college prohibited discrimination on racial or religious grounds.

* * I f the City were to have no interest in the completed project it would

have not been careful to forbid a mortgage on the property. Presumably,

the City did not want this public development to fall into the hands o f a

mortgagee vrho would not be bound by the public purposes to which Stuyvesant

Town is obligated by the contract terms.

22

The danger of lending public controls without holding

the beneficiaries accountable for compliance with the Con

stitution was recognized by the Supreme Court at the 1943

term in Smith v. AUwright, supra, as follows:

“ The United States is a constitutional democracy.

Its organic law grants to all citizens a right to par

ticipate in the choice of elected officials without re

striction by any state because of race. This grant to

the people of the opportunity for choice is not to be

nullified by a state through casting its electoral process

in a form which permits a private organization to prac

tice racial discrimination in the election. Constitu

tional rights would he of little value if they could he

thus indirectly denied. (Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268,

275, 59 S. Ct. 872, 876, 83 L. Ed. 1281.)”

What applies to the electoral process applies as cogently

to the use of the eminent domain, police and tax powers.

If the defendants are correct in their contention that

theirs is a strictly private operation, free of any require

ments to observe equality under the law, then we have

surely set a dangerous precedent. We will have declared

that government itself, enjoined against discrimination and

abuse of the essential freedoms, may divest itself of its

powers and prerogatives to aid private corporations which

may then openly refuse to abide by the restrictions to

which government itself is subject when it exercises those

powers and prerogatives. The electoral process at least

restrains the public agency against abuse of the individual’s

rights and the people can exercise these restraints at the

polls, but it cannot curb a corporation that is controlled

by a private board. Here in the name of slum clearance

would be a device for the evasion of the troublesome Bill

of Rights with all its cumbrous insistence oil equality and

due process. If the precedent is carried over from urban

redevelopment to other enterprises as well, we will have

opened the door toward a perilous innovation in our gov

ernmental institutions. It would mean that private com

panies operating under the color of public purpose or gen

23

era! welfare may draw upon the arsenal of governmental

powers and employ them as arbitrarily as they choose.

If this is permitted it would soon make a skeleton of the

body politic and reduce democratic safeguards to a shell.

These are no sweeping generalizations; they are the in

evitable sequence of the formula as the defendants seek

to interpret it. Fortunately, the Courts still have the

opportunity to guide and shape that formula into the

framework of the Constitution. They can superimpose

public obligation and constitutional limitations upon every

grant of governmental power to private enterprise.

POINT II

The Courts have restrained even private corporations

from discriminating where they have become reposi

tories of official power.

In the last few years the Supreme Court, noting the in

creased use of private instrumentalities for the perform

ance of governmental functions has subjected them to

corresponding duties, particularly by requiring them to

abide by the requirement for the equal protection of the

laws. Thus, a private labor union and a political party

were enjoined against discriminating because of race. In

another case, a privately-owned “ company town” was held

subject to restraints embodied in the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution. In a Cir

cuit Court case, a library with a private board of trustees,

but publicly as well as privately subsidized, was restrained

from discriminating. These corporations are far more

“private” than the Stuyvesant Town Corporation through

which public obligations, public subsidies and public powers

■weave from the inception of the enterprise to the day of

its final termination. If the Supreme Court’s test is applied,

the determining factor wrould be only wfhether the defend

ants are acting by virtue of the statute and as delegates of

24

the state power under it. If under color of that power

they discriminate against any particular race, the dis

crimination would be held to derive its force and virtue

from state action, i.e., from the statute and would therefore

be voided (Smith v. Allwright, supra).

The test is not whether the private corporation is the

representative of the state “ in the strict sense in which

an agent is the representative of his principal. The test

is whether they are to be classified as representatives of

the state to such an extent and in such a sense that the

great restraints of the Constitution set limits to their

action” (Mr. Justice Cardozo, Nixon v. Condon, supra, p.

487). In the case above cited the Legislature authorized a

political party to prescribe the qualifications of its own

members. The executive committee of the party adopted a

resolution qualifying only white Democrats. The argu

ment was made that the political party was merely a volun

tary association aloof from the impact of constitutional

restraint, as is a Masonic lodge. Mr. Justice Cardozo held

as follows:

“ The pith of the matter is simply this, that, when

those agencies are invested with an authority independ

ent of the will of the association in whose name they

undertake to speak, they become to that extent the

organs of the state itself, the repositories of official

power. They are then the governmental instruments

whereby parties are organized and regulated to the

end that government itself may be established or con

tinued. What they do in that relation, they must do in

submission to the mandates of equality and liberty that

bind officials everywhere. They are not acting in mat

ters of merely private concern like the directors or

agents of business corporations. They are acting in

malters of high public interest, matters intimately con

nected with the capacity of government to exercise its

functions unbrokenly and smoothly. * * * Delegates of

the state’s power have discharged their official functions

in such a way as to discriminate invidiously between

white citizens and black. Ex parte Virginia, supra ;

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 77, 38 S. Ct. 16, 62

L. Ed. 149, L. R. A. 1918C, 210, Ann. Cas. 1918A, 1201.

25

The Fourteenth Amendment adopted as it was with

special solicitude for the equal protection of members

of the Negro race lays a duty upon the court to level

by its judgment these barriers of color.”

Smith v. All/w right, supra, applied the same rule though

recognizing that membership in a political party was no

concern of the state.

“ The privilege of membership in a party may be, as

this Court said in Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45,

55, 55 S. Ct. 622, 626, 79 L. Ed. 1292, 97 A. L. R. 680,

no concern of a state. But when, as here, that privi

lege is also the essential qualification for voting in a

primary to select nominees for a general election, the

state makes the action. # * We think that this statu

tory system for the selection of party nominees for

inclusion on the general election ballot makes the party

which is required to follow these legislative directions

an agency of the state in so far as it determines the

participants in a primary election. The party takes

its character as a state agency from the duties imposed

upon it by state statutes; the duties do not become mat

ters of private law because they are not performed by

a political party.”

The reasoning is analogous. Whom Stuyvesant Town

chooses as tenants may be no concern of the state just as

who are the members of the political party is no concern

of the state. When effective exercise of the franchise is

denied because of race or color by act of a political party

acting pursuant to state law or where participation in a

public benefit is denied because of race or color by a pri

vate organization having governmental functions, the de

nial of the franchise or the benefit is an act of the state

and comes within the restraints of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

A far smaller degree of state regulation was involved

in Steele v. Louisville, supra, than in the case at bar. There,

a labor organization enjoyed under the Railway Labor Act

the exclusive power to negotiate contracts with a railroad

covering employees in a specified craft, including non-mem

26

bers. Its power to execute contracts binding on the non-

members was purely statutory. It executed a contract

which discriminated against Negro members of the craft.

It was argued that if the Railway Labor Act empowered

unions to execute such contracts, it was unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court, at the outset of its discussion of

the legal questions involved, ruled that “ If, as the state

court has held, the Act confers this power on the bargain

ing representative of a craft or class of employees without

any commensurate statutory duty towards its members,

constitutional questions arise” (323 IT. S., at p. 198).

After reviewing the provisions of the statute, the Court

held that it imposed on the union “ at least as exacting a

duty to protect equally the interest of the members of the

craft as the Constitution imposes upon a legislature to give

equal protection to the interests of those for whom it legis

lates” (ibid., at p. 202). This included “ the duty to exer

cise fairly the power conferred upon it in behalf of all

those for whom it acts, without hostile discrimination

against them” (ibid., at p. 203).

The Court went on to point out that the union could

make contractual distinctions among the employees affected

based on legitimate economic considerations (just as Stuy-

vesant Town may here choose its tenants on proper

grounds). It concluded, however, that “ discriminations

based on race alone are obviously irrelevant and invidious.

Congress plainly did not undertake to authorize the bar

gaining representative to make such, discriminations”

(ibid., at p. 203).

The Court in the Steele case recognized that the labor

organization had “ the right to determine eligibility to its

membership” (ibid., at p. 204), but again held that that did

not permit it to discriminate on account of race. If Metro

politan chooses to discriminate on the basis of character,

responsibility or other qualifications comparable to the

criteria for membership in a labor union or other private

organization, it may do so but it may not do so on the

27

basis of race alone. As was said in Mr. Justice Murphy’s

concurring opinion in the Steele case:

“ Nothing can destroy the fact that the accident of

birth has been used as the basis to abuse individual

rights by an organization purporting to act in con

formity with its Congressional mandate. Any attempt

to interpret the Act must take that fact into account

and must realize that the constitutionality of the stat

ute in this respect depends upon the answer given.

The constitution voices its disapproval whenever

economic discrimination is applied under authority of

law against any race, creed or color. A sound democ

racy cannot allow such discrimination to go unchal

lenged. Racism is far too virulent today to permit

the slightest refusal, in the light of a Constitution that

abhors it, to expose and condemn it wherever it ap

pears in the course of a statutorv interpretation” (ibid.,

at p. 209).

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. 2d 212 (C. C.

A. 4, 1945), involved a situation even closer to that of the

case at bar. The defendant library barred the plaintiff

from its school for librarians because she was a Negro. It

appeared that the library was founded by Pratt with a

grant of more than a million dollars, on condition that the

City contribute $50,000 a year and that the library would

be run by a board of trustees appointed by Pratt with the

power to fill vacancies in its own ranks. The gift was

accepted by state statute and municipal ordinance. Later,

the library fund was greatly expanded by the state and

City until at the time of the case most of the funds came

from the state. But the independent and self-perpetuating

board of trustees retained control with City supervision

as to fiscal and other details. Summarizing these facts,

the Court said (149 F. 2d, at pp. 216-217):

“ The donor could have formed a private corporation

under the general permissive statutes of Maryland

witlr power both to own the property and to manage

the business of the Library independent of the state.

He chose instead to seeh the aid of the state to found

28

a public institution to be owned and supported by the

city but to be operated by a self-perpetuating board

of trustees to safeguard it from political manipulation;

and this was accomplished by special act of the legis

lature with the result that the powers ‘and obligations

of the city and the trustees were not conferred bv Mr,

Pratt but by the state at the very inception of the en

terprise.”

The Court found in these facts “ so great a degree of

control over the activities and existence of the Library on

the part of the state that it would be unrealistic to speak

of it as a corporation entirely devoid of governmental char

acter” (ibid., at p. 219). Accordingly the Court concluded

that since “ the authority of the state was invoked to create

the institution and to vest the power of ownership in one

instrumentality and the power of management in another” ,

it was necessary to hold that “ the special charter of the

Library should not be interpreted as endowing it with the

power to discriminate between the people of the state on

account of race and that if the charter is susceptible of

this construction, it violates the Fourteenth Amendment

since the Board of Trustees must be deemed the repre

sentatives of the state” (ibid., at p. 218).

Stuyvesant Town is not “ a corporation entirely devoid,

of governmental character” (Enoch Pratt case, supra).

“ The powers and obligations” of Stuyvesant Town Corpo

ration were “conferred 41 * * by the State at the very in

ception of the enterprise” (Enoch Pratt case, supra). Its

discriminatory policies “based on race alone are obviously

irrelevant and invidious” (Steele case, supra). Although

the defendants could have built a housing project inde

pendently, as indeed they did in Cooper Village adjoining

Stuyvesant Town, they “ choose instead to seek the aid of

the state to found a public institution to be # * sup

ported by the City but to be operated by a self-perpetuat

ing.board of trustees” (Enoch Pratt case, supra).

It is not easy to christen the Stuyvesant Town Corpora

tion. It is definitely not private.*' In many respects it

is more like a public corporation for it resembles in most

respects the limited dividend corporation or housing com

pany (Public Housing Law, section 170, et seq.). The

main differences are that the housing company may oper

ate on vacant as well as slum land, and is regulated as to

rents, occupancy and operations by a housing commissioner

instead of by the Comptroller. Both have their dividends

limited and the general structural pattern of the corpora

tion is in most respects the same. The limited dividend

corporation has been likened to the New York City Hous

ing Authority as a public corporation (New York City

Housing Authority v. Muller, supra, p. 342). Assuming,

however, that the clearest classification for the Stuyvesant

Town Corporation is that of a quasi-public corporation

such as a railroad or public service corporation, no dis

crimination could be practiced (Madden v. Queens Coun

ty Jockey Club, 296 N. Y. 249). But whether this creature

be public, quasi-public or even private, by drawing its

power from a statute, the inhibition against its right to

bar Negroes stands firm.

* McQuillan, on Municipal Corporations, Vol. 1, Sec. 125, defines the three

classes o f corporations as either “public, quasi-public or private * *

First, public corporations, variously styled public, political, civil and municipal

created by the sovereign power for public or political purposes, having for

their object the administration o f a portion o f the power o f the state, as

counties, townships, parishes, schools, reclamation, irrigation, road, levee,

drainage, sanitary, fire and taxing districts, cities, towns, villages and bor

oughs, or municipal corporations, full or quasi-corporations, invested with

certain subordinate powers to be exercised for local purposes connected with

and designed to promote the public good. Public corporations are not only

creations, but instrumentalities o f the state and are subject to visitation and

control.

Second, corporations technically private, but yet o f quasi-public character

having in view some public enterprise in which the public interests are in

volved to such an extent as to justify conferring on them important govern

mental powers, for example, the right of eminent domain. Such corporations

include railroad, turnpike, canal, telegraph, telephone, gas, water, and other

public service companies.

Third, corporations strictly private, the direct object o f v/hich is to pro

mote private interests as banking, insurance, trading and manufacturing.

.' ^ public utility is obligated by the nature of its business to furnish its

service or commodity to the general public, or that part o f the public which

30

POINT III

Even if Stuyvesant Town were completely private as

it contends, its very physical pattern would bring it

within the restraints of the Constitution.

Stuyvesant Town resembles in many respects the town

of Chickasaw, a suburb of Mobile, Alabama, owned by tlxe

Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation (see Marsh; v. Alabama,

326 U. S. 501 (1946)). Like Stuyvesant Town “ the prop

erty consists of residential buildings, streets, a system of

sewers, a sewage disposal plant and a ‘business block on

which business places are situated’ # # in short the town

and its public district are accessible to and freely used

by-the public in general and there is nothing to distinguish

them from any other town and shopping center except the

fact that the title to the property belongs to a private cor

poration.” A Jehovah’s Witness who was arrested for

distributing religious literature contended that her right

to freedom of press and religion guaranteed by the First

and Fourteenth Amendments had been abridged. The

Court stated the question as follows:

“ Can those people who live in or come to Chickasaw

be denied freedom of press and religion simply be

cause a single company has legal title to all the town?

For it is the state’s contention that the mere fact that

the property interests to the town are held by a single

company is enough to give that company power, en

forceable by a state statute, to abridge these freedoms.

We do not agree that the corporation’s property in

terests settle the question. The State urges in effect

it has undertaken to serve, without arbitrary discrimination, and it must, to

the extent of its capacity, serve all who apply, on equal terms and without

distinction, so far as they are in the same class and similarly situated. A c

cordingly, a utility must act toward all members o f the public impartially,

and treat all alike; and it cannot arbitrarily select the persons for whcta it

will perform its service or furnish its commodity, nor refuse to one a favor

or privilege it has extended to another, since the term ‘public utility’ pre

cludes the idea o f service which is private in its nature and is not to be

obtained by the public. Such duties arise from the public nature of a utility,

and statutes providing affirmatively therefor are merely declaratory of the

common law” (51 Corpus Juris, p. 7 ).

31

that the corporation’s right to control the inhabitants

of Chickasaw is coextensive with the right of a home-

owner to regulate the conduct of his guests. We can

not accept that contention. Ownership does not al

ways mean absolute dominion. * # * Whether a cor

poration or a municipality owns or possesses the town

the public in either case has an identical interest in

the functioning of the community in such manner that

the channels of communication remain free. As we

have heretofore stated, the town of Chickasaw does not

function differently from any other town. The ‘busi

ness block’ serves as the community shopping center

and is freely accessible and open to the people in the

area and those passing through. The managers ap

pointed by the corporation cannot curtail the liberty

of press and religion of these people consistently with

the purposes of the Constitutional guarantees * # #.

Since these facilities are built and operated primar

ily to benefit the public and since their operation is

essentially a public function, it is subject to state reg

ulation.”

Whether the restriction be a denial of free press or re

ligion or whether it be a denial of the equal protection of

the law, the principle is the same. If Stuyvesant Town

cannot deny access to a Jehovah’s Witness who will insist

upon distributing her literature within its walled city,

then by similar token Stuyvesant Town may not bar Negro

citizens from the benefits of its facilities solely because of

their race. Of course, the public visitation is of a wider

order in Stuyvesant Town than in Chickasaw. Not only

will the public enter as servants, visitors, friends of ten

ants, delivery men, etc., as they entered the company town,

but all sewers, water mains, electrical conduits and all

other city facilities are to be relocated, the City consenting

to the reconstruction by the corporation of the City’s pub

lic facilities under the streets (Sec. 403-404 of the Con

tract), Moreover, as previously stated, the eminent do

main power was utilized for what are public uses, not

private uses, and tax exemption is extended to the project

for twenty-five years.

32

POINT IV

If the Redevelopment Companies Law empowers the

Stuyvesant Town Corporation to bar Negroes, it would

be unconstitutional. The Court should, therefore, con

strue the law to effect a constitutional purpose.

One of the main purposes of the Urban Redevelopment

Law is the replanning of slum areas and as such represents

an exercise of the police power (New York City Housing

Authority v. Muller, supra, Murray v. LaGuardia, supra).

The replanning was to be accomplished “ in effectuation of

official city plans including the master plan” (Redevelop

ment Companies Law, Secs. 2 and 15). The City Planning

Commission is to approve the project prior to its accept

ance and actually did (City Planning Commission Report

No. 2765, adopted May 20, 1943). The City Charter Re

vision Commission outlined the primary duty of the City

Planning Commission to be the making of the master plan.

“ The Commission in preparing the plan should consider

not only the distribution of the population but its com

fort and health and the beauty of the surroundings in

which they live. The development of residential areas and

the location of such housing projects as are to be under

taken are important parts of intelligent planning * * *.

Zoning is an important element in planning and must al

ways be related to the growth and development of the

City and to the master plan” (Report of the City Charter

Revision Commission in Tanzer, New York City Charter,

pp. 496-497). The charter itself incorporates the recom

mendation and directs the commission to prepare a master

plan “ as will provide for the improvement of the City and

its future growth and development and afford adequate-

facilities for the housing, transportation, distribution,

comfort and convenience, health and welfare of its popu

lation” (New York City Charter, Sec. 197).

33