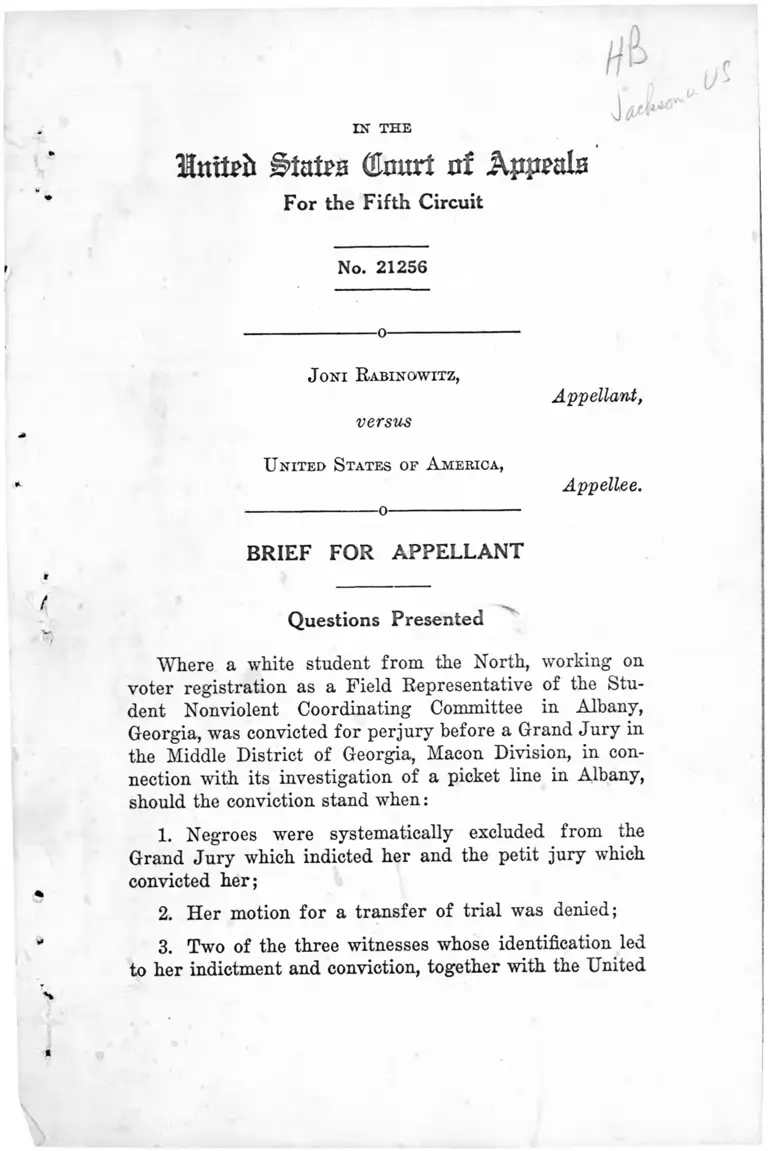

Rabinowitz v. United States Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

June 15, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rabinowitz v. United States Brief for Appellant, 1964. 7dc6c9b1-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b8bb057f-4727-4ae8-bd46-cb5972c1250f/rabinowitz-v-united-states-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN’ TH E

dkmri nx Appals

For the Fifth Circuit

t

H

No. 21256

----------------o-----------------

Joni Rabinowitz,

versus

Appellant,

U nited States of A merica,

---------------------- o-------------------

Appellee.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Questions Presented

Where a white student from the North, working on

voter registration as a Field Representative of the Stu

dent Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Albany,

Georgia, was convicted for perjury before a Grand Jury in

the Middle District of Georgia, Macon Division, in con

nection with its investigation of a picket line in Albany,

should the conviction stand when:

1. Negroes were systematically excluded from the

Grand Jury which indicted her and the petit jury which

convicted her;

2. Her motion for a transfer of trial was denied;

3. Two of the three witnesses whose identification led

to her indictment and conviction, together with the United

ft

2

States Marshal, were present in the Grand Jury room

during a portion of her testimony;

4. Her motion to waive a trial by jury was denied;

5 The United States Attorney inflamed and otherwise

improperly influeneed the Grand Jurors against her an

failed to warn her adequately as to the nature of the pro

ceedings; T

6. The trial coart quashed her subpoenas for F. R i-

and other reports which would have prodded her with

exculpatory evidence; _

7. The verdict was against the overwhelming weig

of the evidence; and

8. One of the members of the petit jury was physically

incompetent to serve 7

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from a judgment of conviction on

lhis is by tt o q <ji621) entered m the

three counts of perjury (18 U. b. ^ ) District of

United States District Court for the Middle M r .

Georgia, Macon Division, on December 2S, 1963 ttma,

812a).

On August 9, 1963, a Federal Grand Jury at Macon,

Oeoroia returned two indictments against appellant The i t fa two^counts charged that on August 5,1963, she had

t u i l l y Ind fa le ^ fasUfled before the G » d Jury

stance that she “ did not remember seeing picketing g »

on at Carl Smith’s Foodland Store, Albany, Georgia, o

on at . -r nn (r;ount 1) and that she did notSaturday, April 20,1963 (Count ai

observe the [said] picketing” (Count 2) (7a). ^ e seco

indictment, in one count, charged that on August 9, 1963

appellant had wilfully and falsely testified before the

Grand Jury, in substance, that she “ was not present at

the scene of the picketing” of said store (9a).

4

to the violation of 4 6(d) of tie Federal Kules of Criminal

Procedure (96a).

The motions were heard on October 1 4 ft ,^ th and 6

1963, and on some of ftenr te^hm y 347a).

motion was denied (178a, 2Wa, >

Several days prior to trial appellant subpoenaed the

November 12, 1963, the opening day of the

lowing proceedings took place:

A. The United States moved ̂to quash the subpoenas

and the motions were granted (357a-361a).

R Appellant moved to dismiss the venire summoned

motion was denied (361a).

c Appellant moved to waive her trial by jury. The

United States objected and the motion was denied (361a-

364a). „ ,,

D. The appellant renewed her motion to transfer the

trial. The motion was denied (364a).

The jury was impanelled and the case was tried until

the eve^ng of November 15th, when it was submitted to

the jury. The jury returned a verdict of gui y

counts (787a).

Subsequently, and within the time allowed by the

Court motions were made by appellant under Rules 29(b)

33 and 34, incorporating the matters alleged above and

other matters arising during the trial (801a) These

tions were denied on December 23, 1963 (813a).

On December 23, 1963, appellant was adjudged a youth

offender pursuant to Title 18 XJ. S. C. $o010 b) (811a

812a). On December 26, 1963, a notice of appeal was filed

(814a), and appellant was released on bond.

5

Specification of Errors

Appellant relies on the following errors in the pro

ceedings in the District Court:

1. Both the Grand and petit juries were drawn from

a jury list which was compiled and selected in violation

of law.

2. An unauthorized person(s) was present while the

Grand Jury was in session, in violation of F. R. C. P., Rule

6(d).

3. The prejudice against appellant in the middle Dis

trict of Georgia was so great that a transfer of trial should

have been ordered.

4. The court improperly denied appellant’s motion to

waive her jury trial and to try the case to a judge.

5. The conduct of the United States Attorney before

the Grand Jury was inflammatory.

6. Appellant was not advised as to the subject matter

of the inquiry before the Grand Jury, she was not prop

erly warned and the purpose of the inquiry before the

Grand Jury was improper.

7. The court erred in quashing appellant’s subpoenas

directed to the United States Attorney and the F. B. I.

8. The verdict was against the weight of the evidence

and the motion for acquittal should have been granted.

9. The petit jury was incompetent because of the physi

cal inability of one of the jurors to perform her services

as juror efficiently.

Relevant Statutes

The relevant statutes and rules will be found in an

Appendix hereto.

6

Facts

The facts will be discussed in some detail m Point VIII

below, and will be summarized here briefly.

Appellant is a twenty-two year old white girl, a student

at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and a resident

of New Bochelle, New York. On or about April 3, 19bd,

she came to Albany, Georgia, as a field representative o

the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNOG),

assigned to work on voter registration (714a, 7-la, 7-6a).

In July, 1963, she was subpoenaed to appear before a

United States Grand Jury sitting in Macon, Georgia. She

appeared before the Grand Jury on August 1st, 5th, and

9 1963 on five separate occasions. The proceedings be ore

the Grand Jury will be discussed more fully m connection

with Points II, V and VI below (318a-344a).

Appellant’s testimony before the Grand Jury was that

she did not remember having observed the picketing of a

grocery store owned by Carl Smith, in Albany, on April

20th; that she thought that if she had seen it she would

have remembered it, and therefore she concluded that she

had not in fact been present at the time of the picketing

(341a-343a). When she was asked if she would admit hav

ing been there if she were to be shown motion pictures, she

answered: “ Well, if it was me, but I don’t believe I was

there. In fact,—well, I know I wasn’t there” (32oa). On

August 9, she asked to see the pictures in the hope that she

might recall the picket line (344a). She was never shown

the pictures.*

The indictments followed.

At the trial the United States presented three wit

nesses who identified appellant as having been present

across the street from the picket line. There was only one

* The United States Attorney, at trial, denied having any

pictures.

7

white girl present (444a). They all testified that on April

20th they had seen her standing 60 to 70 feet away across

a crowded street for a short period of time. All of the

prosecution witnesses were white (425a-484a; 488a-514a).

The defense presented 12 witnesses, all Negro, who

testified that appellant was not present at the time of the

picketing, and that Joyce Barrett, another SNCC field rep

resentative was present (553a-649a). Joyce Barrett, a white

girl, testified that she had been across the street from the

picket line on April 20th (696a-713a). Appellant stated

that, having seen pictures, both motion and still, of the scene

of the picketing, she was now more certain than ever that

she had not been present (714a-733a).

Appellant also called five character witnesses who testi

fied that her reputation for truth and veracity was ex

cellent (485a-487a; 521a-553a). Other witnesses called by

appellant were the Chief of Police of Albany, the owner of

the newspaper and television station in Albany, the F. B. I.

agent in charge of the case, and the United States Attorney,

all summoned in an effort to locate the photographs to

which the United States Attorney had referred in the Grand

Jury hearing (650a-696a). She believed such photographs

would be exculpatory. At the trial no one would admit hav

ing any such photographs.

On December 23, defendant was adjudged a youth of

fender under 18 U. S. C. ̂5010(b), and was committed to

the custody of the Attorney General for treatment and

supervision until discharged by the Board of Parole (811a,

812a).

8

P O I N T I

Both the Grand and the petit jurors were drawn

from a jury list which was compiled and selected in

violation of law.

Facta

The master jury box from which both Grand and petit

juries were chosen contained 1985 names. Of these, 117,

or 5.8% were Negroes. By contrast, the 1960 census showed

that the Macon Division of the Middle District of Georgia

had a population of 211,306 persons over the age of 21,

of whom 73,014, or 34.55% were Negro (90a, 315a, 316a).

This imbalance has been true historically; to the extent

to which there has been any change in recent years, it has

been for the worse. Thus, out of a total of 1837 names

on the 1953 list, 137, or 7.45%, were Negroes. The 1957

census showed that 38.49% of the population of the Divi

sion were Negroes (93a, 289a). The 1940 census showed

that 45.11% of the population was Negro, whereas only

3.21% of the jury list was Negroes (94a).

The statistics in each county are consistent with the over

all results. There was not a single county among the eighteen

within the Macon Division in which the percentage of

Negroes on the jury list even approached the percentage

of Negroes in the population at large (90a, 315a). In Peach

County, where the population was almost 53% Negro, only

eight Negroes were on the jury list out of a total of 123

(6.5%). Twiggs County also has a population a majority

of which is Negro; only one Negro from that county is on

the jury list. Even Bibb County, in which the large city

of Macon is located, supplied only 36 Negroes to the jury

list, representing 5.4% of the total, although over 30%

of the population of the county is Negro.

Such a disparity calls for an explanation. United States

ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53, 66, 67 (C. A. 5, 1962).

The Government made no attempt to supply the explana

tion.

9

However, the appellant offered extensive evidence as to

how the jury list was compiled. The evidence did indeed

explain the disparity; it also made it abundantly clear

that the system used in the Macon Division in compiling

a jury list violated decisions of the Supreme Court and

of this Court. See, infra, pp. 17-24.

The list currently in use was compiled in 1959 by the

Jury Commissioner, the Clerk of the Court and his deputy,

all of whom are, of course, white. The 1953 list was used

as a starting point. Some names were taken off because

of death, physical disability, age, removal from the District,

or other reason (182a, 263a). Then additional names were

collected and questionnaires sent to them. Since the 1953

list was itself unbalanced, the procedure had an inherent

vice, which no one made the slightest effort to correct;

in fact, the contrary is true.

Mr. Simmons, the Jury Commissioner, secured many

additional names from among his acquaintances. They

were people active in “ civic life, a business way, some of

them came from lists of church members” (183a). An

effort was made to see that the Negro race was repre

sented (186a), but not “ to have any given percentage

represented” (187a). It did not occur to him “ to have any

percentage [of Negroes] equal to the percentage of the

population” (188a). He only “ wanted to be sure that we

had some Negroes on the jury list” (188a). He did not

use city directories, tax lists, telephone books or any other

public lists to get the names of prospective jurors (193a

209a).

He did not recall speaking to any Negroes in the school

system, or to Negro ministers, or Negro businessmen,

or Negro civil service employees outside his home county

of Bibb, except possibly in Crawford County (193a-209a).

While he considered it important to get Negroes from rural

counties, such as Butts, Crawford, Houston, Jasper and

Twiggs, he made no effort to carry out this obligation

12

Simmons, he did not know “ too many Negroes (242a).

While he was able to identify some persons as Negroes

during the hearing, he generally did so by making m er-

ences from their addresses (253a, 254a). He did contact

fraternal and church organizations for the names of

prospective jurors but only white organizations. He got

rosters of names from such organizations, but not from

any Negro organizations (267a).

Mr. Doyle, the Deputy Clerk, concentrated his efforts

on getting jurors from the rural counties. His procedure

was simple and uniform. In each county he went to the

County Courthouse and spoke to the Clerk of the Cou ,

to the Sheriff, to the Ordinary, to the tax officers and o

others “ who worked in those places” (260a). ^ each

county he spoke to half a dozen people or more ; in the 18

counties he spoke to between 125 and loO people. In two

or three counties he also spoke to businessmen and secre

taries of lawyers (261a). Not one was a Negro (.60a,

261a).

In each county he asked for the names of qualified

Negroes. Although there are Negro ministers, business

men, school teachers and doctors in many counties, he did

not know a single one nor did he speak to one (262a, 263a).

He thought it unnecessary to ask Negroes for the names

of possible Negro jurors because he thought his white

“ sources” were “ competent to give [him] the names o

qualified people” (263a).

Like Mr. Simmons, he had his “ own idea of what a

qualified juror ought to be * * *; he ought to be a person

that is of good character, a person that is intelligent that

can understand the cases that are tried m court (263a).

In Macon Mr. Doyle assisted Mr. Cowart. He contacted

the “ various civic groups, church groups” (266a). He did

not contact any Negro group. In fact, he did not com

municate with a single Negro in Macon (266a). On cross-

15

When we examine how the list was made up, it becomes

apparent that the strictures of the Supreme Court and

of this court were completely ignored. A long line of

cases has made it abundantly clear that a heavy burden

rests on those responsible for choosing a jury “ * * *

to follow a procedure—‘ a course of conduct’—which would

not ‘ operate to discriminate in the selection of jurors on

racial grounds.’ Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 404 (1942).”

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559, 561.

And as the Court said in Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 289:

“ When the Commissioners were appointed as

judicial administrative officials, it was their duty to

familiarize themselves fairly with the qualifications

of the eligible jurors of the county without regard to

race and color. They did not do so here, and the

result has been racial discrimination.”

And Chief Justice Stone, in Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400,

404, said:

“ Discrimination can arise from the action of

commissioners who exclude all negroes whom they do

not know to be qualified and who neither know nor

seek to learn whether there are in fact any qualified

to serve. In such a case discrimination necessarily

results where there are qualified negroes available

for jury service. With the large number of colored

male residents of the county who are literate, and

in the absence of any countervailing testimony, there

is no room for inference that there are not among

them householders of good moral character, who

can read and write, qualified and available for grand

jury service.”

The language of this Court in United States ex rel.

Seals v. Wiman, supra at 67, is directly applicable here.

“ Not only does the respondent fail to come for

ward with an adequate justification to explain this

long-continued, wide discrepancy between the num

ber of qualified Negroes in the County and their rep

resentation on the jury rolls, but the evidence is prac-

16

ticallv conclusive that the method of selection at the

time of Seals’ trial and during the preceding years

inevitably resulted in systematic exclusion of all but

a token number of Negroes from the jury lolls

In this case, as in Wiman the court officials followed

the oft-disapproved device of choosing persons for t e

jury list from among their personal contacts, a procedure

which made inevitable the result which we here attack.

Thus we see that the methods used by the state au

thorities in Wiman and in Supreme Court cases like

Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S. 398, Cassell v. Texas, supra,

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584, Hill v. Texas, supra,

and Avery v. Georgia,345 U. S. 559, are m essence the

methods used by the District Court authorities here, i

anything, the Commissioners in Wiman made a greater

effort to get Negro jurors—at least they asked a few

Negroes to make suggestions. United States v. Wiman,

supra, at 60, 61. In other respects the methods used here

and in Wiman were identical. See, for example, reliance by

the Commissioners on personal acquaintances almost ex

clusively white (Wiman, p. 60; this record, pp. 21oa

242a) • use of the rosters of white organizations but not of

Negro {Wiman, p. 60; this record, pp. 266a, 267a); failure

to solicit the names of Negroes beyond the “ narrow circle

of ordinary contacts of the Commissioners” {Wiman, p. 60;

this record pp. 210a, 262a). The failure of the Commis

sioners to take the necessary steps to get a balanced jury

list is easily understood; they did not understand that they

were under any obligation to do so (187a, 188a, 228a, 241a).

It was enough, they thought, that they had “ some” Negroes

(186a, 187a, 241a).

The respondent seems to rely entirely on the subjective

“ good faith” of the court officials and the learned court

below seemed to feel that the lack of “ intentional dis

crimination” was “ a factor of considerable importance

(293a). We must respectfully differ. We do not believe

17

that the subjective intent of the jury officials is a matter

of any importance at all. Reece v. Georgia, supra, Her

nandez v. Texas, supra, Hill v. Texas, supra. This court

said in Wiman, supra, at page 65:

“ # * * Those same cases, however, and others,

recognize a positive, affirmative duty on the part

of the jury commissioners and other state officials,

and show that it is not necessary to go so far as

to establish ill will, evil motive, or absence of good

faith, but that objective results are largely to be

relied on in the application of the constitutional

test * *

The court below seemed to be a bit uneasy about the

imbalance in the list and pointed out that the list would

be revised from time to time (293a). The Clerk also noted

that there had been no revision of the list since this court’s

decision in Wiman and he seemed to think that the next

revision would be time enough to give “ consideration to

that or any other case” (230a). The court urged qualified

Negroes to come forward and volunteer for jury duty

(293a) and it also evidently felt that the matter of getting

a better cross-section of the conununity was “ a matter for

the future” (293a). We have seen no suggestion in the

cases that the burden is on prospective Negro jurors to fight

their way into the jury box; every case on the subject that we

have seen, including Wiman, puts the burden on the court

officials who are charged with the duty of selecting a jury.

B. Constitutional issues aside, the method used to select

Grand and petit juries violated accepted federal

standards of jury selection as well as the

relevant statutory standards.

This case differs from Hill, Avery, Reece, Brown,

Akins, Eubanks, Wiman and other cases cited above in

that it relates to a federal jury, not a state jury. The

federal standard is determined, not only by constitutional

requirements, but also by the supervisory power of the

18

Supreme Court “ to reflect [its] notions of good policy”

(Fay v. N. Y., 332 U. S. 261, 287). Constitutional limita

tions aside, the standards set by the applicable Federal

statutes and the notions of good policy of the Supreme

Court in choosing a federal jury have been violated here.

1. The jury did not represent a cross-section

of the community.

The federal cases are clear that a federal jury in both

civil and criminal cases must represent a cross-section of

a community. In Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60,

at 86, the Court said that the jury commissioners

“ * * * nlUst not allow the desire for competent

jurors to lead them into selections which do not

comport with the concept of the jury as a cross-

section of the community. Tendencies, no matter

how slight, toward the selection of jurors_ by any

method other than a process which will insure a

trial by a representative group are undermining

processes weakening the institution of jury trial,

and should be sturdily resisted. That the motives

influencing such tendencies may be of the best must

not blind us to the dangers of allowing any encroach

ment whatsoever on this essential right. Steps inno

cently taken may one by one lead to the the irretriev

able impairment of substantial liberties.”

Thus, a system of selecting jurors which eliminates

women is invalid because it

“ * * * deprives the jury system of the broad

base it was designed by Congress to have in our

democratic society. It is a departure from the

statutory scheme. As well stated in United States

v. Roemig, D. C., 52 F. Supp. 857, 862, ‘ Such action

is operative to destroy the basic democracy and

classlessness of jury personnel.’ It ‘ does not accord

to the defendant the type of jury to which the law

entitles him. It is an administrative denial of a right

which the lawmakers have not seen fit to withhold

19

from, but have actually guaranteed to him.’ Cf.

Kotteakos v. United States, 328 U. S. 750, 66 S. Ct.

1239. TheAnjuryis nut limited to the defendant—

there is injury to the jury system, to the law as an

institution, to the- cominnnity'atr'large, and to the

democratic Ideal reflected in the processes of our

courts.11 Ballard v. United States, 329 U. S. 187,

1957

Perhaps the most comprehensive discussion by the

Supreme Court on the subject can be found in Thiel v.

Southern Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 217, where a civil verdict

was set aside because daily wage earners were excluded.

There the Court listed six groups in the community which

must be recognized and given representation on a jury,

namely, “ the economic, social, religious, racial, political

and geographical groups of the community” (p. 220). Com

pare this with the statement of the clerk of the court here,

who said that he did not recognize the Negroes as a class

who required adequate representation (228a). It is true, as

the Court pointed out in Thiel, that every jury need not

contain representatives of each of these groups. But a

method of choosing jurors is impermissible if it results in

discrimination against any of these groups.

It will be noted that in the Thiel case there may not

have been prejudice to the petitioner. But, said the Court:

“ * * * On that basis it becomes unnecessary to

determine whether the petitioner was in any way

prejudiced by the wrongful exclusion or whether he

was one of the excluded class. See Glasser v. United

States, supra; Walter v. State, 208 Ind. 231, 195

N. E. 268, 98 A. L. R. 607; State ex rel. Passer v.

County Board, 171_Minn. 177, 213 N. W. 545, 52

A. L. R. 916. It is likewise immaterial that the jury

which actually decided the factual issue in the case

was found to contain at least five members of the

laboring class. The evil lies in the admitted whole

sale exclusion of a large class of wage earners in

disregard of the high standards of jury selection.

20

To reassert those standards, to guard against the

subtle undermining of the jury system, requires a

new trial by a jury drawn from a panel properly

and fairly chosen.” (At p. 225)

As the Court said in the Ballard case, supra, “ the in ^

jury is not limited to the defendant—there is injury to. the—

jury system; * * * to the community at large an4 to the

democratic ideal * * * ” (p. 195).

The Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit faced the

same problem in Dow v. Carnegie Illinois Steel Corp., 224

F. 2d 414 (C. A. 3, 1955). The Court, sitting en banc, first

noted that it is sufficient if appellant directs his attention to

***** the general method of jury selection, with

out showing that the particular jury that tried the

case was deficient and, consequently, without estab

lishing prejudice to the particular litigant usually

prerequisite for invoking remedial action.

Presumably a particular jury of the most desirable

type might be drawn from a list that was on the

whole selected by faulty methods. But, as a practical

matter, it is so difficult to formulate and administer

a system prescribing the composition of individual

juries that the law has placed the emphasis on in-

insuring a fair system of general juror selection

which in operation will normally result in adequate

individual juries. It is consequently the general

system of selection that is susceptible to successful

attack by a litigant. See Thiel v. Southern Pacific

Co., 1946, 328 U. S. 217, 220, 66 S. Ct. 984, 90 L. Ed.

1181. Moreover, by allowing the general method of

selection to be questioned in any case, the complain

ing party serves as a helpful spur to the courts in

their supervision of the administration of justice.

See Ballard v. United States, supra, 329 U. S. at

page 195, 67 S. Ct. at page 265.” (At p. 422)

The Court then went on to point out that, whereas the

courts, in passing on a state jury, are limited to considera

tion of the constitutional requirements of the Fourteenth

23

Mr. President, we believe the amendment consti

tutes a great step forward in the field of civil rights.

We believe also that it can contribute significantly

in forwarding the cause to which most of us are

dedicated—the cause of enacting a civil-rights bill

in this session of the Congress.” 103 Cong. Rec.

13154 (July 31, 1957)

When the bill in its final version was before the Senate,

then-Senator Lyndon B. Johnson commented on this change

in the law in his summary of the important features to it.

He said:

Seventh, and finally, the bill secures without

discrimination the right of all citizens of all races,

all colors, and all creeds, to serve on federal juries.”

103 Cong. Rec. 13897. (August, 1957)

Despite the amendment of the law, it is obvious that the

court officials in the federal court at Macon continued to

apply the standards set by the Georgia statute. Georgia

requires the jury commissioners to select “ upright and in

telligent citizens to serve as jurors” (Ga. Code Ann. Title

59, ^106). And so the court officials here sought jurors

who in their opinion were sufficiently intelligent to under

stand what was going on in the courtroom. It is perhaps

not surprising that the extra-statutory qualifications were

discussed only in connection with prospective Negro jurors

(196a, 207a, 208a, 209a, 232a, 233a).

The District Court in Louisiana recently had occasion

to consider a similar test in United States v. Louisiana, 225

F. Supp. 353 (1963), where the state required that prospec

tive voters “ be able to understand and give a reasonable

interpretation of any section of [the] Constitution” . We

cannot say that the requirement imposed by Mr. Simmons

and Mr. Doyle on prospective jurors, i.e., that they be able

to understand the cases being tried in a courtroom, is any

easier to meet; many lawyers and even some judges some

times have difficulty in this regard. All of the objections

24

to the Louisiana statute (225 F. Supp. at 381, 383, 387) are

applicable here as well. As the court there said at p. 387:

“ The understanding and interpretation of any

thing is an intimately subjective process. A commu

nication of that understanding is itself subject to the

understanding or interpretation of the listener or

reader. Even in an atmosphere of mutual coopera

tion and good will, it is often very difficult for one

person to know that the other actually understands

what is being said or done. As appears from the

evidence, however, in many registration offices in

Louisiana the relation between the Registrar and

Negro applicants can hardly be described as mutu

ally cooperative. * * * ”

“ * * * the customs of generations, the mores of

the community, the exposure of the individual to

segregation from the cradle make it difficult, if not

impossible, for a registrar to evaluate objectively

what is necessarily a subjective test. We are sensible

of the registrar’s difficulties—he must live with his

friends—but we must recognize that his predilec

tions weight the scales against Negroes and hinder

fair administration of an interpretation test or a

citizenship test. When neither the Constitution nor

the statutes prescribe any standards for the admin

istration of the test, the net result is full latitude

for calculated, purposeful discrimination and even

for unthinking, purposeless discrimination.”

We need not labor the point. The application of an “ under

standing” requirement in qualifying a juror is just as

subjective as the application of such a test in registering

voters. And all of the objections found by the Court to

the Louisiana statute are equally applicable to the situa

tion here.

25

P O I N T I I

The presence of an unauthorized person(s) while

the Grand Jury was in session violates F. R. C. P. Rule

6(d) and requires dismissal of the indictment.

The appellant was subpoenaed to appear before the

Grand Jury on August 1, 1963 (716a). She was sworn

on her first appearance before the Grand Jury on that

date (82a). At 12:30, during her testimony, the Grand

Jury recessed and she was instructed to return at 1:30

(339a). Later on in the same afternoon she was twice

recalled before the Grand Jury. Each time the Marshal

ushered her to the door of the Grand Jury room. Once

Carl Smith was present in the Grand Jury room as a wit

ness; the other time James Fritz was the witness. On

each occasion appellant was asked if she was Miss Joni

Rabmowitz. On each occasion she answered in the affirma-

tive (273a-277a). Prior to her appearance Smith had not

identified appellant, but he did so when she came into

the Grand Jury room (449a-460a).

The inviolacy of Grand Jury proceedings is protected

by Rule 6(d) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure

which provides:

Who May be Present. Attorneys for the gov

ernment, the witness under examination, interpreters

when needed and, for the purpose of taking the

evidence, a stenographer may be present while the

grand jury is in session, but no person other than

the jurors may be present while the grand jury is

deliberating or voting. ”

This rule was first formulated when the Rules were

adopted in 1946. Some consideration of its history and of

the predecessor legislation is relevant.

. .The 1872 statute relating to the validity of a Federal

indictment read:

26

“ No indictment found and presented by a grand

jury in any district or circuit or other court of the

United States shall be deemed insufficient, nor shall

the trial, judgment, or other proceeding thereon be

affected by reason of any defect or imperfection in

matter of form only, which shall not tend to the

prejudice of the defendant.” (R. S. § 1025)

In May 1933 the statute was amended to read:

“ No indictment found and presented by a grand

jury in any district or other court of the United

States shall be deemed insufficient, nor shall the

trial, judgment, or other proceeding thereon be

affected by reason of any defect or imperfection in

matter of form only, which shall not tend to the

prejudice of the defendant, or by reason of the

attendance before the grand jury during the taking

of testimony of one or more clerks or stenographers

employed in a clerical capacity to assist the district

attorney or other counsel for the Government who

shall, in that connection, be deemed to be persons

acting for and on behalf of the United States in an

official capacity and function.” (48 Stat. 58, 18

U. S. C. former § 556.)

It will be noted that both statutes spoke in terms of

procedure which might “ tend to the prejudice of the

defendant” . Such language was omitted in the 1946 revi

sion. The omission was not an accident but was intentional.

As the court said in United States v. Powell, 81 F. Supp.

288, 291 (D. C. Mo. 1948), “ We recognize the law that the

presence of unauthorized persons in the grand jury room

results in a presumption of prejudice to the defendant

* # *_>> ^ ncj see jjnited States v. Carper, 116 F. Supp.

817 (D. C. D. C. 1953).

Not only was the language requiring a tendency to

prejudice omitted from the 1946 Revision, but it will be

noted that whereas the word “ interpreters” in the statute

appears in the plural, the word “ witness” in the statute

appears only in the singular. This too was not an accident.

27

It was explained by Judge George Z. Medalie, a member of

the Supreme Court Advisory Committee and then As

sociate Judge of the New York State Court of Appeals. A

few days before the rules became effective he spoke before

the New York University School of Law Institute on Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure. In discussing Rule 6(d), he

said:

“ When I first heard of Federal criminal proce

dure, I found that it was the practice to try to get

rid of indictments by proving that someone was in

the grand jury who had no right to be there, and

usually it was some deputy marshal or somebody

else, some unauthorized person, and then the great

to-do was how to get a person authorized. One of

the ways to get a stenographer authorized in those

days was to have him sworn in as Assistant United

States Attorney, when he really was nothing of

the kind.

“ Now, cases have come up on motions to quash

because of unauthorized persons in the grand jury

room, so we drew up a little list as to who is au

thorized. * * * We say * * * ‘ the witness under exami

nation’—no one has ever moved to dismiss on account

of his presence; ‘ interpreters when needed.’ Now,

here is a little touch which we picked up because of

the wide geographic distribution of the membership

of our committee. We didn’t say ‘ an interpreter.’

We said ‘ interpreters.’

* # #

“ You have the same thing right here in New York;

for example, a person who speaks only Turkish, a

person who speaks only Greek and Turkish, a per

son who speaks Greek and English. That is provided

for.”

Before the adoption of the 1916 Rules this Circuit held

that even under the 1872 statute, a nominal participation

by an unauthorized person in the proceedings was sufficient

to require the invalidation of an indictment. In Latham v.

United States, 226 Fed. 420 (C. A. 5, 1915), this Court

said at page 424:

28

“ The right of a citizen to an investigation by a

grand jury pursuant to the law of the land is in

vaded by the participation of an unauthorized person

in such' proceedings, he that participation great or

small. It is not necessary that participation should,

he corrupt or that unfair means were used. If the per

son participating was unauthorized, it was unlawful.

* * * We cannot therefore assent to the doctrine that

the presence in the grand jury room of the steno

grapher, and his participation m such proceedings

to the extent of taking testimony of witnesses before

the grand jury, is an informality, and unless pre

judice is alleged and shown, the motion should be

denied. It is in my judgment a matter of substance.

* * * We are therefore of the opinion that the assign-

ment is sustained and the motion should have been

granted, and the indictment quashed. (Emphasis

supplied).

The court specifically approved the language of the District

Court of Montana in United States v. Edgerton, 80 Fed.

374, 375 (1897) when it said:

<< * * * The Court cannot know that this sugges

tion [that there was no prejudice] represents the

fact * * * The court cannot inquire as to the effect o±

this conduct. There must not only be no impioper

influence or suggestion in the grand jury room but

as suggested in Lewis v. Commissioners, 74 C.

174, there must be no opportunity. * * *”

See also United States v. Borys, 169 F. Supp. 366 (D. C.

Alaska 1959); United States v. Rubin, 218 Fed. 245 (D.

Conn. 1914); United States v. Amazon Industrial Chemical

Corp., 55 F. 2d 254 (D. C. Md. 1931); United States v. Fall,

10 F. 2d 648 (C.C.A. D.C. 1925).

In this case the Marshal was in the Grand Jury

room together with two witnesses (Smith and the appellant

in one case; and Fritz and appellant in the other). There

is no authority in the statute for the Marshal to he present

at all and as we have seen the Advisory Committee speci

fically considered the problem in drawing the rule. Similarly,

29

there is no authority in the statute for two witnesses to be

present before the Grand Jury simultaneously.

In fact, in the only case found in 'which two witnesses

were present in the Grand Jury room at the same time, the

Court, in dismissing the indictment, cited the Federal Rule

and held:

. ,. think that historically and on principle an

indictment should be dismissed when two witnesses

have been presented together while the testimony of

one or both was heard by the Grand Jury and that

i? ^ecisl0n should not be made to depend upon

whether or not a defendant was actually prejudiced

thereby.” Peo. v. Minet, 296 N. Y. 315, 321-322.

As we have already indicated, the court below in reading

a requirement of prejudice into the rule (283a) clearly

erred. In acutal fact, however, the appellant was prejudiced

by the violation of Rule 6(d) here. The basic issue in this

trial was identification of the girl who stood across the

street from the picket line. Such identification was neces

sary, not only at the trial, but also at the Grand Jury if

an indictment was to be found. The identification was made

by having appellant appear and confront Smith and Fritz

before the Grand jury. Through that confrontation, identifi

cation was made.

The court below, recognizing that "this question is not

entirely free from difficulty” (283a) relied on those cases

which required a showing of prejudice before the indictment

could properly be dismissed.

The court relied principally on what it found to be the

■holding m United States v. Terry, 39 Fed. 355, 361 (D C

CaHfi,_ 1889), quoting the phrase “ The mere presence of

he District Attorney when the voting takes place is at

most an irregularity” . In fact, the full quotation is:

,, me,r® presence of the district attorney when

the voting takes place is at most an irregularity,

which, when there is no proof or averment of injury

30

or prejudice of the defendant, is a matter of form,

and not of substance, within the scope of ̂1025 Rev.

Stat. U. S.”

If anything, the Terry case is authority for appellant.

The court there considered the statute in California, which

was similar in purport to the present Rule 6(d). It dis

agreed with the policy of that statute and then said, at

p. 361:

“ The provisions of the Penal Code of California

are not binding on the federal tribunals * * * . The

United States Statutes contain no such provision.”

But now, the United States rules do contain such a

provision, and the appellee can gain little comfort from

Terry.

The court below also relied upon three state cases:

State v. Canatella, 72 A. 2d 507 and State v. Krause, 50

N. W. 2d 439, where those courts suggested that, in the

absence of a statute (there being none in those cases), there

must be a showing of prejudice, and Rush v. State, 45 So.

2d 761, where the court held that a defendant must show

injury. This court has before it a clear rule which by its

terms requires no showing of prejudice, and a situation in

which actual prejudice of a most substantial kind did

occur.

Finally, the court below cites Hale v. United States, 25

F. 2d 430 (C. C. A. 8, 1928) for the proposition that the

presence of a stenographer did not depart from the statu

tory rule. The stenographer in that case was in fact an

Assistant United States Attorney General, authorized by

order of the court to conduct Grand Jury proceedings, and

therefore within the letter of the statute; furthermore, the

1872 statute, requiring a tendency to prejudice, was appli

cable there.

31

P O I N T I I I

. The P^iudice against the class of which aooeliant

is a part was so great as to have required a transfer

of trial to a less hostile district.

3 h! ^ Fu°Vide f° r tte trans,cr of a trial “ otterdistrict when there exists, where the prosecution is pondim.

great prejudice against the defendant, F.R.C.P 21(a) In

actuai fact in most instances, the prejudice is not directed

at the particular defendant, but rather at a group or class

of persons with which the defendant is identified in the

minds of prospective jurors. United States v. Mesarosh,

a, ' ' 80 J i ’ D' Pa-’ 1952)—Communists; United

Mates v. Dioguardi, 28 F. R. D. 33 (S. D. N. Y. 1956)—

ra f ; Pne°Ple V' Ryan’ 123 Misc- 450> 205 N. Y. Supp

4 a925)—Cathohcs; People v. Lucas, 131 Misc. 664, 228

V w ’ ^iUe7 ' i 3A m928)~ Negroes; People v- Sanches, 181 S. W. 2d 87, 147 Tex. Cr. 436 (1944)-Mexicans.

The affidavits and testimony of each of appellant’s

twenty-one witnesses (12a-86a) in support of the applica

tion for transfer of trial to a district where the prejudice

*as not present have a common theme. Each recognized

the ccmipkx nature of the basis of prejudice in the context

ere presented, and each analyzed in detail the cultural

l n s l S0C1t v01̂ at W° rk throuShout recent Southern lstoiy which militated against the likelihood of potential

veniremen meeting the required standard of impartiality.

Without exception, the appellant’s affiants indicated that in

• er Person.and by her activities, appellant placed herself

of thhepP° Sltl0n 0ne 011 whom tlie tensions and prejudices

Thp f , T t 7 Zl™ f0Cused with greatest intensity, llie facts speak for themselves:

1. The appellant is a white student participating in

the organizational work of a group (SNCC) which is and

as been publicly vilified m the district with regularity

and intensity. One of the avowed aims of the organization

32

is to register eligible Negro voters, challenging, by this

activity, the political structure of county and state (14a,

32a, 81a, 85a).

2. The appellant is a white girl living in proximity to

Negro males as part of her daily work. The uncontro

verted testimony accurately reflects the community’s deeply

ingrained negative view of persons who violate the sexual

taboos widely prevalent in the South. The testimony is

that the reaction of a white Southerner would be to infer

that the appellant had sexual relations with Negro males

merely because of such proximity (35a, 41a, 82a, 85a).

3. The appellant is from the City of New York; this

fact alone heightens the prejudice already present towards

one who is situated as the appellant has been. The appel

lant would be:

“ * * # tried under a special handicap, because a

white person from the North who comes South to

work for racial integration becomes the object of

a powerful prejudice against ‘ outside agitators’.

This prejudice is deeply rooted in Southern history,

going back to Reconstruction days, and has been

reinforced in the recent years of racial tension. It

is well established in socio-psychological analysis

that xenophobic attitudes are intensified under con

ditions of tension. Such conditions have pervaded

the Albany area, and the South in general, in the

last few years. Suspicion and hostility directed

against the outsider are not just random in the

population, but under the particular circumstances

of the South have become embedded in the culture of

the region.” (Affidavit of Howard Zinn, 14a-15a).

See also 17a, 32a, 38a, 40a, 43a, 44a, 49a, 65a, 78a,

83a, 143a.

The affidavits submitted in opposition to the motion

for transfer of trial (100a-138a) failed to meet or even

to acknowledge the existence of this deep-seated feeling

among citizens in the district and in the South generally;

indeed they made no effort to answer appellant’s evidence.

33

This condition has been described by such illustrious

deponents as Dr. Harold J. Lief, Professor of Psychiatry

at Tulane University (34a-36a); Harry S. Ashmore, former

editor of the Arkansas Gazette and now director of research

of the Encyclopedia Britannica (84a-86a); Kenneth Clark,

Professor of Psychology at the College of the City of New

York (71a-72a); Warren Breed, Professor of Sociology

at Tulane University (66a-70a); and John Kenneth

Morland, Chairman of the Department of Sociology at

Randolph-Macon Women’s College, as an inability to

recognize the prejudicial effect of the cultural and social

environment on white Southerners for the last hundred

years.

It is not suggested that affiants for the prosecution in

any way misrepresented their understanding of the situa

tion. Rather, it is that the nature of the social-cultural

structure render them unable to perceive the effect which

the appellant or anyone else so situated has upon them.

As pointed out by Professor Breed:

“ (b) Given this tradition, and the fact that it

is found to be difficult for an individual to maintain

attitudes which oppose the views of liis parents,

friends and associates, and which are institutional

ized in the community life, one can conclude with

a high degree of assurance that any panel of

Southerners would be predisposed to reflect this

shared attitude. It is not only deeply lodged -within

the individual, but is reinforced by the attitudes of

the relevant others. Furthermore, on an occasion

such as a jury trial involving a civil rights issue

which becomes known to the public, one would expect

psychological pressures on the jury member in the

form of anticipating the consequences of a verdict

which fails to uphold this tradition, and perhaps

also certain objective pressures as well. By ‘ con

sequences’, I mean the consequences of his action

for the individual juror, that he may anticipate

would befall him in the event of a jury verdict of

34

acquittal. I wish to stress the notion of ' anticipa

tion’ ; it is quite possible that no serious harm would

come to the juror in such an event; what is signifi

cant is the kind of consequences he may imagine

while in the process of decision. Having lived among

his fellows for many years, he will consider these as

well as the pure justice of the case, and the objective

facts adduced during the proceedings.” (68a-69a)

The United States Justice Department and the Attor

ney General have time and again recognized the prejudicial

nature of juries in the race relations context, and have

made it the basis of their decision not to bring actions on

behalf of civil rights advocates (21a-30a).

The appellant does not suggest that a Negro can never

obtain a jury trial free from prejudice in this division.

In those circumstances where the mores of the community

are not placed in jeopardy by the activities of a defendant,

such as prosecutions pursuant to 26 U. S. C. 5601 et seq.

for “ moon-shining” , the paternalistic attitude toward the

Negro felt by many white Southerners might even be

helpful to a Negro defendant. It is only where, as here,

there is a direct confrontation between the social structure

of the community and the acts of an individual, that the

prejudice is so great as to warrant a transfer of trial to

a jurisdiction where the social conditions do not make

almost inevitable a finding of guilt unrelated to the facts

as presented.

Where there is presented to the court, as there was to

the court below, uncontroverted and well documented scien

tific analyses of the facts which, taken together, demon

strate substantial prejudice, the standards by which courts

determine whether the conditions exist for transfer of trial

must be enlarged to include such factors. For a court to do

otherwise would be to ignore the realistic considerations

which make a fair trial impossible here.

35

As Mr. Justice Holmes said many years ago:

“ * * * This is not a matter for polite presump

tion; we must look facts in the face. Any judge who

has sat with juries knows that, in spite of forms,

they are extremely likely to be impregnated by the

environing atmosphere. * * * ” Frank v. Mangum,

237 U. S. 309, 349 (dissent).

More recently, this was expressed in Delaney v. United

States, 199 F. 2d 107, 112 (C. A. 1,1952):

“ * * * One cannot assume that the average juror

is so endowed with a sense of detachment, so clear in

his introspective perception of his own mental proc

esses, that he may confidently exclude even the un

conscious influence of his preconceptions as to prob

able guilt* * *.”

Where it appears that community prejudice will prevent

a fair and impartial trial, relief under Rule 21a must be

granted. United States v. Rositer, 25 F. R. D. 258 (P. R.

1960); United States v. Parr, 17 F. R. D. 512 (S. D. Tex.,

1955); United States v. Florio, 13 F. R. D. 296 (S. D. N. Y.

1952).

P O I N T I V

Appellant had a right under the Constitution and

the federal rules to waive a jury trial under the circum

stances of this case.

The method of selecting petit juries, the nature of the

issues in this case, and the attitude of the community toward

“ interfering Northerners” raised substantial questions as

to the possibility of a fair trial in the Macon Division. Ap

pellant had attacked the composition of the jury list in the

pre-trial proceedings; she had also moved for a transfer

of trial. Those motions having failed, she sought to waive

her jury trial and to try the case to the court. Her counsel

36

made that proposal to the United States Attorney during

the week before the trial (361a). In return, counsel received

a telegram from the United States Attorney saying In

view of trial being set for November 12 and jury having

already been subpoenaed this office will not consent to de

fendant waiving trial by jury” (362a).

Prior to the trial, appellant moved for a waiver of jury

urging first that the right to waive a trial by jury is a con

stitutional right of the defendant (362a), and second, that

even if Government consent is required for a waiver, such

consent was here unreasonably and arbitrarily withheld

(363a). The court denied the motion, stating:

“ Well, I think I ’ll overrule that motion. We have

here the question of knowledge and intent, do we not,

in this case, intent to violate the law. That iŝ the

charge is knowingly testifying falsely. That’s a

proper issue to have 12 people pass on rather than

one, I think” (364a).

Appellant’s reasons for wishing to waive a jury are

clear enough. Jurors are more prone to bias than judges;

they are less likely to be affected by decisions of the appel

late courts in the series of cases since Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483; they are less likely to be affected

by the profound changes in our social and legal philosophy

which have taken place in the past ten years with respect

to the racial problems in the South. Therefore, with the

denial of the appellant’s motions addressed to the jury list

and to the place of trial, the appellant’s motion for a trial

by a judge rather than a jury raises problems not only

under Article III, ̂2, and the Sixth Amendment to the

Federal Constitution, but also under the Due Process

Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

The last paragraph of Article III, § 2, of the Constitu

tion and the Sixth Amendment guarantee the appellant the

right to a trial by jury in a criminal case. It is clear that

these provisions of the Constitution were adopted for the

37

benefit of the defendant in a criminal case and not for the

benefit of the Government. See Annals of Congress, 452,

458, 783-85, 787-89 (Gales ed. 1834); Rutland, The Birth

of the Bill of Rights 1776-1791 (1955), passim; 3 Story,

Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States,

^§ 1773-74 (1833). A “ trial by jury was considered solely

a defendant’s safeguard against arbitrary government

prosecution when the Constitution and the Bill of Rights

were adopted” . United States ex rel. Toth v. Qu-arles, 350

U. S. 11, 16.

Article III, § 2, as the Supreme Court has said, is not

jurisdictional in the sense that a court without a jui’y is

an incompetent tribunal. Patton v. United States, 281

U. S. 276. It “ was meant to confer a right upon the ac

cused which he may forego at his election” (281 U. S. at

298). In Adams v. United States ex rel. McCann, 317 U. S.

269, the Supreme Court said, at 275, that there is “ nothing

in the Constitution to prevent an accused from choosing to

have his fate tried before a judge without a jury” .

Since the jury trial provisions were inserted to protect

the defendant and since the court is competent to try a

person accused of crime without a jury, there is in principle

no reason why a defendant cannot waive a jury trial.

Other constitutional rights designed to protect a defendant

may be waived, such as the right to a speedy trial, Worthing

ton v. United States, 1 F. 2d 154 (C. C. A. 7, 1924); the

right to indictment, Barkman v. Sanford, 162 F. 2d 592

(C. C. A. 5, 1947); the right to be confronted by witnesses,

Diaz v. United States, 223 U. S. 442; Grove v. United States,

3 F. 2d 965 (C. C. A. 4, 1925); the right to assistance by

counsel, Adams v. United States ex rel. McCann, 317 U. S.

269; Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458; the right to trial in

the state and district of the crime, United States v. Jones,

162 F. 2d 72 (C. C. A. 2, 1947); the right to a public trial,

United States v. Sorrentino, 175 F. 2d 721 (C. A. 3, 1949);

the right to protection against double jeopardy, Trono v.

38

United States, 199 U. S. 521; and the right to protection

against self-incrimination, Powers v. United States, 223

U. S. 303. In none of these cases is there any suggestion

that the consent of either Government or court is necessary

to make the waiver effective, nor was such consent required.

The Government and the court, however, rely on Rule

23(a) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which

seems to require court approval and Government consent

before a jury trial may be waived. We urge that if this

rule gives the prosecution an absolute right to veto the

defendant’s waiver of a jury trial, it is unconstitutional,

being in violation of Article III, the Sixth Amendment and

the Fifth Amendment. Further, that the rule as applied

here operated to deprive appellant of very substantial

rights and hence did not come within the scope of the

rule-making power of the Supreme Court under Title 18

U. S. C. § 3371.

We suggest, however, that Rule 23(a) can be read con

sistently with the applicable constitutional and statutory

provisions. As so read it requires that the defendant’s

waiver of trial by jury must be respected unless und£r the

peculiar circumstances of the case such a waiver will oper-

afp to deprive the accused of a fair trial. No such circum

stances was presented here; the contrary is true.

A. Rule 23(a) as here applied is unconstitutional.

Rule 23(a) is said, by the Notes of the Advisory Com

mittee, to be an embodiment of existing practice as illus

trated by the Supreme Court holdings in Patton v. Umted

States, 281 U. S. 276, and Adams v. United States ex rel.

McCann, 317 U. S. 269. It is therefore appropriate to con

sider these cases in some detail.

The sole issue in the Patton case was the right of the

accused to waive a jury and the court held that he had that

right. No issue was raised by either briefs or record as

to approval and consent by court and Government and

39

none could have been raised since such approval and con

sent had been given. The concluding paragraph of the

Court’s decision, wherein appears the language relating to

“ the consent of government counsel and the sanction of

the court’ ’ (p. 312) is therefore dictum.

Furthermore, the language of the rest of the opinion

and the decision itself makes it obvious that the dictum was

never intended to give to either the court or the Govern

ment an absolute right of veto of a waiver of a jury trial.

Indeed, the tenor of the Court’s opinion is to emphasize the

great significance of a jury trial as a protection to and a

privilege of the accused. Thus, the Court quoted with ap

proval, at p. 295, the dissenting opinion of Judge Aldrich

m Dickinson v. United States, 159 Fed. 801, 820 (C C A 1

1908): ' ‘ ’

“ It is_ probable that the history and debates of

the constitutional convention will not be found to

sustain the idea that the constitutional safeguards

in question were in any sense established as some

thing necessary to protect the state or the commu

nity from the supposed danger that accused parties

would waive away the interest which the govern

ment has in their liberties, and go to jail.

There is not now, and never was, any practical

danger of that. Such a theory, at least in its appli

cation to modern American conditions, is based more

upon useless fiction than upon reason. And when

the idea of giving countenance to the right of waiver,

as something necessary to a reasonable protection of

the rights and liberties of accused, and as something

intended to be practical and useful in the adminis

tration of the rights of the parties, has been charac

terized, as involving innovation ‘ highly dangerous,’

it would, as said by Judge Seevers in State v. Kauf

man, 51 Iowa 578, 581, 2 N. W. 275, 277, 33 Am. Rep.

148, ‘have been much more convincing and satisfac

tory if we had been informed why it would be highly

dangerous. * * * ”

40

The Supreme Court itself, said at p. 296:

“ The record of English and colonial jurispru

dence antedating the Constitution will be searched

in vain for evidence that trial by jury in criminal

cases was regarded as a part of the structure of gov

ernment, as distinguished from a right or privilege

of the accused. On the contrary, it uniformly was

regarded as a valuable privilege bestowed upon the

person accused of crime for the purpose of safe

guarding him against the oppressive power of the

King and the arbitrarv or partial judgment of the

court. # * *

“ In the light of the foregoing it is reasonable

to conclude that the framers of the Constitution

simply were intent upon preserving the right of

trial by jury primarily for the protection of the

accused. * * * ”

None of this reasoning can lead to any conclusion ex

cept that the right of jury trial is, constitutionally, the

right of the accused and that his interest is the interest the

Constitution was meant to protect. Hence it would follow

that even if the Government and court may withhold their

consent to a waiver of jury trial, it may do so only to pro

tect the interest of the accused. The convenience of the

Government, of the jurors or of the court cannot under the

language of Patton be a ground for withholding consent.

The Adams case, supra-, involved the right of a de

fendant who was not represented by counsel, to waive a jury

trial. Here, too, the consent of the court and the Govern

ment had been given and hence the need for such consent

was not an issue in the case. The Court did not consider

the need for consent except to repeat in substance the

language of Patton. Again, the Court made it clear that

the test to be applied was the welfare of the accused, noting

at page 276 that

“ procedural devices rooted in experience were writ

ten into the Bill of Bights not as abstract rubrics in

41

an elegant code but in order to assure fairness and

justice before any person could be deprived of ‘ life,

liberty or property’

In citing Patton, the Court said, at page 278:

“ And whether or not there is an intelligent, com

petent self-protecting waiver of jury trial by an

accused must depend upon the unique circumstances

of each case.”

The Court thus delimited the scope of the authority of the

Government or the court to withhold its consent, making the

test one of the protection of the defendant. This is true

because, said the Court at page 279: “ What were contrived

as protections for the accused should not be turned into

fetters” . We are forbidden “ to imprison a man in his

privileges and call it the Constitution” (p. 280).

The dissenting judges felt that the accused in the Adams

case had not made an intelligent and competent decision

to waive a jury and that he should have had legal advice

before his waiver was accepted. No such situation is pre

sented here.

The application of the Adams logic to the case at hand

requires reversal. Here neither the court nor the Govern

ment withheld its consent because of any extraordinary

desire to protect the appellant. The Government withheld

its consent because the jury had already been subpoenaed,

a totally irrelevant consideration. It is not at all clear

whether the court exercised any independent judgment on

the matter. Its remarks, at 364a, in denying the motion,

are cryptic. At most it may be said that the court felt that

a charge of “ knowingly testifying falsely [is] a proper

issue to have 12 people pass on rather than one.” No rea

son is given for this conclusion.

Neither of these reasons for withholding consent can

be said to comport with the language of the Supreme Court

43

We cannot blind ourselves to the facts of life. The

prosecuting attorney, under normal circumstances, is anx

ious to secure a conviction. He is unlikely to consent to

any procedure which, in tactical terms, will make a con

viction less likely. Particularly is this true in a case where

the defendant is represented by counsel, thus relieving the

prosecution of whatever obligation it may otherwise have

to protect the accused. With all respect to the rules laid

down by the Supreme Court in eases such as Berger v.

United States, 295 U. S. 78 and Pyle v. State of Kansas, 317

U. S. 213, the prosecution cannot realistically be expected to

sacrifice its own chances of securing a conviction by per

mitting a mode of trial which is less likely to secure that re

sult, even if, in the informed and reasonable judgment of

the defendant’s counsel, such a trial would be more fair.

Indeed the prosecution should not be put in a position where

it may be subject to conflicting interests.

Therefore, to place under the control of the Govern

ment the determination as to whether the defendant may

waive a jury is unsound, not only as a matter of law but

as a matter of public policy as well.

As a matter of fact, on the basis of the record there is

no reason at all to believe that the prosecution was in

any degree whatsoever interested in protecting the rights

of the defendant to a fair trial when it withheld its consent.

No doubt, it was interested in securing a conviction. We

do not think that was improper; the impropriety lies in

the court’s apparent ruling that the prosecution should

have the right to veto appellant’s determination to waive

her constitutional rights.

The court in a criminal case likewise has a limited right.

It has the duty ‘ ‘ of seeing that the trial is conducted with

solicitude for the essential rights of the accused” . Glosser

v. United States, 315 U. S. 71. The judge’s own personal

desire that issues of fact be tried by a jury rather than by

44

himself is quite irrelevant to the matter at hand. The issues

at stake are considerably more important than any con

siderations of convenience or preference.

Ours is an adversary system of justice even in criminal

cases and the primary obligation for the protection of the

accused must rest, in our society, on the accused himself

and counsel. This is not an obligation which ought to be

delegated either to the court or to the Government; to do

so on this record had the effect of depriving appellant of

a fair trial.

Many state courts have faced this problem, and they

have been met in a variety of ways. The most recent deci

sion is People v. Duchin, 16 App. Div. 2d 483 (2d Dept.) 229

N. Y. S. 2d 46 aff’d 12 1ST. Y. 2d 351, 239 N. Y. S. 2d 670

(Ct. of App. 1963). The court there had before it a con

stitutional provision which permitted waiver with the ap

proval of the court. Defendant was charged with rape in

a case that had received a great deal of publicity. Feeling

that he could not receive a fair trial before a jury, and

acting through competent counsel, he sought to waive his

right to a jury trial. The prosecutor refused to consent

but gave no reasons; the court denied the waiver. The

Appellate Division held that the judge had abused his dis

cretion in denying waiver. It said:

“ The constitutional provision conferred on the

defendant the right to have trial by a jury, or with

out a jury, at his option, unless for some compelling

reason arising out of the attainment of the ends of

justice his option might not be honored. A contrary

determination would sap the force of the Constitu

tion and render it meaningless save at the uncon

trolled will of the court.” 16 App. Div. 2d at 485-

299 N. Y. S. 2d at 49.

46

there have been so many sensational newspaper

stories about cases about to be tried that a defend

ant honestly and sincerely could say that he would

prefer the judgment of a single judge and not be

tried by a jury of his peers. I don’t have to cite

instances. You’re all aware of many of these cases.

I have given some thought to the problem and bar

ring compelling authority—my judgment is that the

Rule that we presently have which requires the con

sent of the prosecution conflicts with a defendant’s

constitutional right to waive any constitutional right

accorded him by the Federal Constitution, and that

he does not require the consent of government to

give up his right to a trial by jury * * *. So my

answer to you is, and my own opinion is, that there

is no requirement, constitutionally, that a defendant

in order to give up his right to a trial by jury re

quires the consent of the prosecution—that he has

such a right, provided of course, that it be freely

and voluntarily exercised.” (34 F. R. D. 205).

An aspect of the issue presented here is now before

the United States Supreme Court in Singer v. United

States, 326 F. 2d 132 (C. A. 9, 1964); certiorari granted

April 20, 1964, No. 898, October Term, 1963. There the

accused sought to waive a jury trial “ for the purpose of

shortening the trial” , the indictment containing 29 counts.

(See Brief for the United States in Opposition to Petition

for a Writ of Certiorari, p. 6.) His application to try the

case to the court was denied by both prosecution and the

court without assigning any reason therefor.

In our view of the law the Singer case requires re

versal. Singer was represented by counsel and there is no

suggestion that he did not knowingly waive his right to a

jury trial. Similarly, there is no suggestion that his

attempted waiver was in anything other than good faith.

There seems to be no interest of the public which requires

that he be compelled to proceed before a jury and thus, as

Mr. Justice Frankfurter pointed out in the Adams case,

47

become imprisoned in his constitutional rights. The in

i^ th eT o lV t a fr F ° ne- Jt may weI1 have

nf ^ i S t° r „Genera S mmd when> in opposing a writ

of certiorari m Singer, he suggested that a different result

m;ght have followed if d e f ia n t had argued t £ “ l ? u r v

O p p o X n ^ b<5 " nfair” <Brief Sta‘ eS “

li»n0 nD S . I ™ > i ° f !hiS SU,latl0n re«uires considera-

mea’t and the l * ," ,C? rel<'d as b’ ™ g to the Govern-

ft de™ ^ ™ absokte veto over appellant's right

beetTe u k ' ^ 7 f “ S CaSe> “ is " “ constitutional because it is m excess of the power of the Supreme Court

under both the Constitution and 18 U. S. C. § 3771.

Supreme Court f t ° ' ̂3771( deleSates ‘ ° the United States supreme Court the power to prescribe “ rules of pleading

practice and procedure • • * in criminal cases” . Obviously

the power of the Court can extend only to matters of

procedure. Not only does the enabling statute so limit

e court s authority in express language, but any other

inclusion would violate the fundamental concep/of our

to p t s t w s SySte“ W“ Cl r6SerVeS ‘ ° C° n«ress ‘ ba tight

i 139 F' 2d 721 (C- a «■

Co ^ ? d i n r e 4 :“ Lfrtat ^

giv7en USrb y yiawP” CCd" ral r“Ie “ sabstakiaI tight

In Barltman v. Sanford, 162 F. 2d 592 (C C A 5 1947 \

this court said: ’

posedbv t Ct, that then Ule Was aPProved and pro- P y he Supreme Court also supplies it with an

f£ V f reat,’ but not complete, invincibility. The

act that a rule was promulgated by the Supreme

48

Court does not raise it above the Constitution, never

theless, the source of the rule is such as to suggest

strongly that all who enter into its forum of con

troversy should tread lightly even though we con

sider it merely as a congressional enactment.” (593)

And, in United States v. Sherwood, 312 U. S. 584, 589,

the Supreme Court, in considering its analogous power to

make rules in civil proceedings, said:

“ An authority conferred upon a court to make

rules of procedure for the exercise of its jurisdiction

is not an authority to enlarge that jurisdiction and

* * * 28 U. S. C. § 723b * * * authorizing this court

to prescribe rules of procedure in civil actions gave

it no authority to modify, abridge or enlarge the

substantive rights of litigants or to enlarge or dimin

ish the jurisdiction of federal courts.”

See also, Mississippi Publishing Corp. v. Murphree, 326

IT. S. 438.

It can hardly be said that the question of whether appel

lant was to be tried by a court or a jury was a mere proce

dural matter. The right of jury trial has always been

recognized as one of the foundation stones of the legal

system; the right to waive the protection of a jury trial

when exercised knowingly, with the assistance of diligent

counsel and in a setting in which such waiver is reasonable,

is equally fundamental. To hold that Rule 23(a) subjected

that right to a veto by the prosecution—a veto to be exer

cised for any reason or for no reason at all—certainly

affects appellant’s fundamental rights in this case. If

Rule 23(a) takes on the meaning given it by the court below,

it goes far beyond the right to set “ rules of procedure”

delegated to the Supreme Court by § 3771.

49

B. Rule 23(a) may be interpreted to avoid

constitutional invalidity.

The Supreme Court has held that a ruling on the con

stitutionality of a statute will be avoided “ if a construc

tion of the statute is fairly possible by which the question

may be avoided” . Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331

U. S. 549, 569.

It is implicit in everything we have said before that

such a construction is possible here. The rule may fairly

be construed to mean that the accused has a right to waive

his trial by jury and that the consent of the Government

and court are required only to protect the defendant who

has no counsel, or who may, for other reasons, be acting

unwittingly and without a full awareness of what he is

doing. Such a construction is consistent with the language

m the Patton and Adams cases, as well as with the best

reasoned of the state court cases. It is not inconsistent