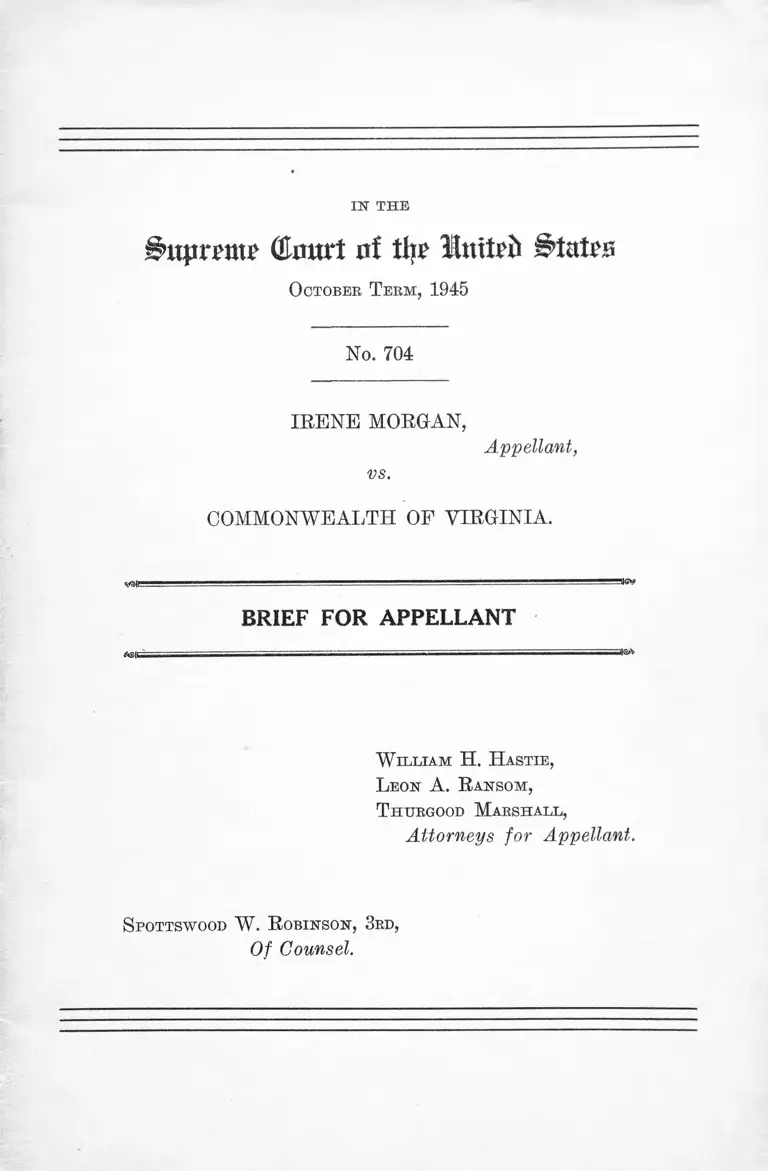

Morgan v. Virginia Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1945

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morgan v. Virginia Brief for Appellant, 1945. 331eafba-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b8c14a93-d127-46fc-a069-b15d51f13bd7/morgan-v-virginia-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN' THE

(Emtrt of tlie United States

October T erm, 1945

No. 704

IRENE MORGAN,

vs.

Appellant,

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA.

^a){l . i --------- ............................................................................................................ -LL'Ul^ a S *

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

<f.g|r—••—~~r~~7T — ------------------------------ — - - — - t—- ... . . . ...... - . ■ ■ -= : -~ j= r r r = = r = » i!,A

W illiam H. H astie,

L eon A. R ansom,

T htjrgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Appellant.

Spottswood W . R obinson, 3rd,

Of Counsel.

I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion Below ____________________ 1

Jurisdiction ________________________________________ 1

Summary Statement of Matter Involved_____________ 2

1. Statement of the Case____________________ 2

2. Statement of Facts___________________________ 3

3. The Applicable Statute and Its Construction___ 4

Errors Belied Upon__________________________________ 6

I. __________________________________ 6

II. ______________________________________________ 7

Summary of Argument______________________________ 7

Argument

I This Court Has Consistently Asserted That States

Do Not Possess the Authority Which Virginia Now

A sserts______________________ 1___________________ 8

II Regulations Concerning Racial Segregation in Inter

state Commerce Fall Within the Area of Exclusive

National Power as Judicially Defined___...________ 14

A. State Statutes in This Field Are So Numerous

and Diverse That Their Imposition on Interstate

Commerce Would Be an Intolerable Burden_____ 17

B. The Racial Arrangement of Interstate Passen

gers Within a Vehicle in Transit Across a State

Is Not a Matter of Substantial Local Concern.... 26

Conclusion _____________________ 28

Appendix A __________________ .______________________ 29

11

Table of Cases.

Anderson v. Louisville & N. Ry., 62 Fed. 46 (C. C. Ky.) 12

Bowman v. Chicago & N. W. Ry. Co., 125 U. S. 465.....11,15

Brown v. Memphis & C. Ry., 5 Fed. 499 (C. C. Term.) .. 12

Buck v. Kuykendall, 267 IJ. S. 307-.._____ ____________ 15

Carrey v. Spencer, 36 N. Y. Supp. 886________ ______.... 12

Chesapeake & 0. Ry. Co. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S. 388.... . 9

Chesapeake & 0. Ry. Co. v. State, 21 Ky. L, 228, 51

S. W. 160____ ____________________________________ 20

Chicago B. & O. Ry. Co. v. Railroad Commission of

Wisconsin, 237 U. S. 220__________ _______ ..._____ 15

Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71.___ 9

Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 125 Ky. 299, 101

S. W. 386__________ i____________________________ 20

Cleveland, C. C. & St. L. Ry. Co. v. Illinois, 177 U. S.

514___________ ..... .. .________ ........_______ ................ 11

Covington & C. Bridge Co. v. Kentucky, 154 U. S. 204 ... 11

Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. 35______________ _______ . 17

Di Santo v. Pennsylvania, 273 U. S. 34_______________ 16

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160____ _________ ...__ 17

Erie R. R. v. Public Utility Commissioners, 254 U. S.

394 ______________ 15

Gentry v. McMinnis, 33 Ky. 382—_________________ 25

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1___ _________________ ____ 14

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 IJ. S. 485___________ 8, 9,11,12,14, 20, 28-

Hanely v. Kansas City Southern Ry. Co., 187 U. S. 617 11

Hare v. Board of Education, 113 N. C. 10, 18 S. E. 55..... 26

Hart v. State, 100 Md. 596, 60 Atl. 457_______________ 12,14

Huff v. Norfolk-Southern R. Co., 171 N. C. 203, 88 S. E.

344 _______________________________________ 12

Illinois Central Ry. v. Redmond, 119 Miss. 765, 81 So.

115______________________________________________ 12

Kelly v. Washington, 302 U. S. 1_____________________ 15

Lee v. New Orleans G. N. Ry., 125 La. 236, 51 S. 182___ 24

Louisville, N. O. & T. Ry. Co. v. Mississippi, 133 U. S.

587 __________________________ _________ i__________ 9

Louisville & N, R, Co, v, Eubank, 184 U. S. 27_________ 11

PAGE

I l l

McCabe v. Atcheson, Topeka and Santa Fe Ry. Co., 235

U. S. 151_________________________________________ 9

Minnesota Rate Cases, 230 U. S. 352----------------~--------- 11

Missouri v. Kansas Natural Gas Co., 265 U. S. 298._....... 11

Moreau v. Grandieli, 114 Miss. 560, 75 S. 434---------- ---- 24

Morgan’s L. & T. R. R. & Steamship Co. v. Louisiana,

118 IT. S. 455_____________________________________ 15

Mullins v. Belcher, 142 Ky. 673, 143 S. W. 1151________ 25

Ohio Valley Ry.’s Receiver v. Lander, 104 Ky. 431, 47

S. W. 344 ____________________________________ 20

Pennsylvania v. West Virginia, 262 U. S. 553— ------- 15,16

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537------------------------------- 9

Rhodes v. Iowa, 170 IT. S. 412------------------------- __1.------ 11

Smith v. State, 100 Tenn. 494, 46 S. W. 566__________ 12, 21

South Carolina Highway Dept. v. Barnwell Bros., Inc.,

303 IT. S. 177____________________________________ 15

South Covington & C. St. Ry. Co. v. Covington, 235

U. S. 537 ____________________________________ -...11,15

South Covington & C. St. Ry. Co. v. Commonwealth, 181

Ky. 449, 205 S. W. 603__________ ______ _______—10, 20

South Covington & C. St. Ry. Co. v. Kentucky, 252 IT. S.

399 _____________________________________________ 10, 11

South Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 IT. S. 761__________ 11,14

State ex rel. Abbott v. Hicks, 44 L. Ann. 770, 11 So. 74 . 12

State v. Galveston H. & S. A. Ry. Co. (Tex. Civ. App.)

184 S. W. 227______ ________ -_________________ ____ 12

Theophanis v. Theophanis, 244 Ky. 689, 57 S. W. (2d)

957 _______________________________________-______ 25

Tompkins v. Missouri, K. & T. Ry., 211 Fed. 391 (C. C.

A. 8th) ________ -______________ _______ _________ _ 12

Tucker v. Blease, 97 S. C. 303, 81 S. E. 668 — -------24

Veazie v. Moor, 14 How. 568__________________________ 14

Wabash, St. L. & P. Ry. Co. v. Illinois, 118 U. S. 557___ 11

Washington, B. & A. Ry. v. Waller, 53 App. D. C. 200,

289 Fed. 598_____________________________________ 12

Western Union Tel. Co. v. Pendleton, 122 U. S. 347—- - 11

PAGE

IV

Table of Statutes.

PAGE

Alabama—-

Code, 1923, Sec. 5001_________________________ 19, 23, 24

Acts, 1927, p. 219 __________ ..._____,.___________..._ 24

Statutes, 1940—

Title 1, Sec. 2_____________________ 23

Title 14, Sec. 360________________________ 23

Title 48, Secs. 196-197___________ ...____ 21

Title 48, Sec. 268_____________._________________ 20

Arkansas—

Statutes 1937 (Pope)—

Secs. 1190-1207 ----------------------------------------19,22,23

Sec. 3290 _________________________ 23

Secs. 6921-6927 J l _____________ ..._____ 20

Acts, 1943, pp. 379-381____________________________ 20

Florida—•

Constitution, Article XVI, Sec. 24___________ _____ 23

Statutes, 1941—

Sec. 1.01__________________________ 23

Secs. 352.07-352.15 _____________________..____ 19,20

Georgia—

Code, Michie (1926), Sec. 2177____________ 25

(1933)—

Secs. 18-206 to 18-210____________________ 19

Secs. 18-9901 to 18-9906 _______ ...__________ 19

Sec. 68-616 _______________________________ 20

Laws, 1927, pp. 272-279______________..._______ ...____ 23

Supplement 1928, Sec. 2177—______________ ...______ 23

Indiana—

Statutes (Burns), 1933—

Secs. 10-901, 10-902 __________ 19

Secs. 44-104 ___________________________ ...____19 23

Iowa—

Code, 1939, Secs. 13251-13252______________________ 19

Kansas—

General Statutes, 1935, Sec. 21-2424_______________ 19

V

K entucky-

Revised Statutes 1942 Sec. 276.440________________ 19

Statutes (Carroll) 1930, Sec. 801__________________ 22

Louisiana—

Acts, 1910, No. 206_____________________ _________ 25

Criminal Code (Dart) 1932, Arts. 1128-1130_______ 25

General Statutes (Dart) 1939—

Secs. 8130-8132, 8181 to 8189___________________ 19

Secs. 5307-5309 _____________________________ 20

Maine—

Revised Statutes, 1930, Ch. 134, Secs. 7-10_____ ___ 19

Maryland—•

Code (Flack) 1939, Art. 2 7 -

Sec. 445 ________________________________ 21,23

Secs. 510-516 ______________ 19

Secs. 517-520 ......___ ________________________ ...... 20

Art, 27, Sec. 438______________________________ 22

California—

Civil Code (Deering), 1941, Secs. 51-54____________ 19

Colorado—•

Statutes, 1935, Ch. 3, Secs. 1-10___________________ 19

Connecticut—-

General Statutes (Supp. 1933) Sec. 1160b__________ 19

Massachusetts—

Laws (Michie) 1933, Chap. 272, Sec. 98, as amended

1934 ________ 19

Michigan—

Compiled Laws (Supp. 1933) Secs. 17, 115-146 to

147 ______________ ____ ______ - _______________ 19

Minnesota—•

Statutes (Mason), 1927, Sec. 7321------------------------- 19

Mississippi—-

Code, 1942-

Sec. 459 ______________________________________ 23

Sec. 7784 _________________ _______ ,__________ 19

Sec. 7785 ____________________ 20

Sec. 7786 _____________________________________ 19

Constitution, Sec. 263__________________ _________ 23

PAGE

VI

Missouri—

Revised Statutes 1939, Sec. 4651._______________ .... 23

Nebraska—

Comp. Statutes, 1929, Ch. 23, Art. 1____________ ___ 19

New Hampshire—

Revised Laws, 1942, Ch. 208, Secs. 3-4, 6__ ________ 19

New Jersey—

Revised Statutes, 1937, Secs. 10:1-1 to 10:1-19_____ 19

New York—■

Laws (Thompson) 1937 (1942, 1943, 1944 Supp.),

Ch. 6, Secs. 40-42______________________________ 19

North Carolina-—

Constitution, Article XIV, Sec. 8 _______ ___________ 23

General Statutes, 1943—

Sec. 14-181 __________________________________ 23

Sec. 51-3 _______________________ ...____ ________ 23

Secs. 60-94 to 60-97___________________ 19, 20, 21, 22

Secs. 60-135 to 60-137 _______________________ . 19

Sec. 62-109 ________________________________ 20

Sec. 115-2 _____:_____________________________23, 25

North Dakota—

Revised Code, 1943, Secs. 14-0304 and 14-0305______ 23

Ohio—

Code (Throckmorton) 133, Secs. 12940-12941......... 19

Oklahoma—

Constitution—

Art. XIII, Sec. 3__________________________ 23

Art. XXIII, Sec. 11_____ 23

Statutes, 1931—

Sec. 13-181 ___________ 19,23

Sec. 13-187 ________________________________ 22

Sec. 13-189 ____________________________ 22

Sec. 43-12 __________________________________ 23

Sec. 70-452 ______________________ 23

Secs. 47-201 to 47-210--,.™_____________..._______ 20

PAGE

Oregon—

Compiled Laws, 1940, Sec. 23-1010________________ 23

Pennsylvania—•

Statutes (Purdon)—

Title 18, Sec. 1211 ______________________ ____ 19

Title 18, Secs. 4653-4655 ______________________ 19

Rhode Island—

General Laws, 1938—

Ch. 606, Secs. 27-28____________________________ 19

Ch. 612, Secs. 47-48____________________________ 19

South Carolina—-

Code, 1942-

Sec. 8396 ___________________________ -_______ 19, 20

Sec. 8399 ___________ _________________ __21,22

Secs. 8490-8498 ...___________ ______ ___________ 19

Secs. 8530-8531 ______________2_____ _ _ _______ 20

Constitution, Article III, Sec. 33-------- ------------------- 23

Tennessee—

Code (Michie) 1938—

Secs. 5518-5520______________________________19, 22

Secs. 5527-5532 ______________________________ 19

Sec. 8409 _____________________________________ 23

Sec. 8396 _________________ -..... .......... ..... .... . .. 23

Constitution, Article XI, Sec. 14------------------1------..... 23

Texas—

Civil Statute (Vernon) 1936—

Sec. 2900 _____________________________________ 23

Sec. 6417 _______________________19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 26

Sec. 4477 ____________ 26

Sec. 4607 ____v,______________ ________— ......... 23

Penal Code (Vernon) 1936—

Sec. 493 ______________________________________ 23

Secs. 1659-1660 __________________________ 19,21,22

Sec. 1661.1 __________________________________ 20

V ll

PAGE

PAGE

viii

United States Code, Title 48—

Sec. 344(a) _____________._____________________ 1

Sec. 861(a) ____________________...._____________ 1

Constitution—

Art. I, Sec. 8_________________________________ 3, 6

Amendment X IV __________________________ .... 3

Amendment X _______________________________ 7

Virginia—

Acts, 1930, Chap. 128

Code (Michie) 1942-

Sec. 67 _________

Sec. 3928 _______

Secs. 3962-68 ......

Secs. 3978-83 ___

Secs. 4022-26 ......

Secs. 4097z-dd

Sec. 4097z ______

Sec. 4097aa _____

Sec. 4097cc _____

Sec. 4097dd ____

Sec. 5099a ______

Washington—

Rev. Statutes (Remington) 1932, Sec. 2686________ 19

Wisconsin—

Statutes, 1941, Sec. 340.75____________________ 19

-__________ 4

L _~ ______ 23

__________ 26

18,19, 21, 22, 26

_____ __ 18,19

_________ 18, 20

__________4, 20

_____ _____ 4,18

_____________ 4,18

__________ 5,18

______2, 3, 5,18

---------------- 25

IN THE

C o u r t o f tl|£ S t a t e s

October T erm, 1945

No. 704

I rene M organ,

vs.

Appellant,

Commonwealth oe V irginia.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

appears in the record (R. 56-68) and is reported in 184 Va.

24, 34 S. E. (2d) 491.

Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdic

tion to review this case on appeal under the provisions of

Section 344 (a) and 861 (a) of Title 28 of the United States

Code because the highest court of the State of Virginia

has rendered final judgment in this suit sustaining the

validity of a criminal statute of the State of Virginia after

the validity of the statute had been drawn into question by

the appellant prosecuted thereunder, on the ground of its

being repugnant to the Constitution of the United States.

2

The date of the judgment of the Supreme Court of Ap

peals of Virginia which is now being reviewed was June 6,

1945 (E. 68). Appellant filed a timely Petition for Rehear

ing (R. 69), and this Petition was denied on September 4,

1945 (R. 69). Application for Appeal was duly presented

on November 19, 1945 and allowed on the same day (R. 72).

Probable jurisdiction was noted by this Court on January

28, 1946 (R. 76).

Summary Statement of Matter Involved

1. Statement of the Case

The appellant was tried in the Circuit Court of the

County of Middlesex, Virginia, upon an amended warrant

charging that on the 16th day of July, 1944, she did “ unlaw

fully refuse and fail to obey the direction of the driver or

operator of the Greyhound Bus Lines to change her seat

and to move to the rear of the bus and occupy a seat pro

vided for her, in violation of Section 5 of the Act, Michie

Code of 1942, Section 4097dd” * (R. 27). She was found

guilty by the trial judge sitting without a jury and on

October 18, 1944, was sentenced to pay a fine of $10.00 (R.

54-55).

In the trial court, appellant duly raised and preserved

by appropriate exceptions her objection that the statute in

question is invalid because it is repugnant to the Constitu

tion of the United States. Specifically by motion to strike

the evidence of the Commonwealth (R. 39, 48), by motion

to set aside the decision and arrest the judgment of guilt

(R. 50-51), and by motion for a new trial (R. 52), appellant

duly asserted her claim that the statute in question could

not be made applicable to this case without violation of

* The statute is set out in full in the record (R. 7-9).

3

Section 8 of Article I of the Constitution of the United

States, and that the conviction of appellant under the cir

cumstances of this case constituted a violation of her rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States.

On writ of error to the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia the assignment of errors again set forth appel

lant’s claim that the statute under which she was convicted

could not be applied to her without violating Article I, Sec

tion 8 of the Constitution of the United States (R. 1-2). The

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia affirmed the judg

ment of the trial court and in its opinion considered and

adjudicated the issues raised in favor of the validity of the

statute in question as applied to appellant.

2. Statement of Facts

On July 16, 1944, appellant, who is a Negro, was a

passenger on a bus of the Richmond Greyhound Lines, Inc.,

traveling from Hayes Store in Gloucester County, Virginia,

to Baltimore, Maryland (R. 31, 40), on a through ticket pur

chased by her from said company (R. 33, 34, 40). The bus

was traveling on a continuous and through trip from Nor

folk, Virginia, to Baltimore, Maryland, via Washington,

D. C. (R. 32-33). During this journey, at Saluda, Virginia,

the driver of the bus, a regular employee of the bus com

pany in charge and control of the bus, directed appellant

to move from the seat which she was occupying (in front

of the rear seat) to the rear of the bus pursuant to a design

to enforce the segregation of white and colored passengers

in accordance with the requirement of the Virginia segrega

tion law and particularly Section 4097dd of Michie’s Code

of Virginia (R. 31, 32, 40-41). Appellant refused to move,

whereupon the driver procured a warrant and caused her

4

to be arrested upon a charge of violating the above statute.

There is no dispute concerning the above facts.

3. The Applicable Statute and Its Construction

In 1930, the General Assembly of Virginia enacted a

statute described by its title as “ An Act to provide for the

separation of white and colored passengers in passenger

motor vehicle carriers within the State; to constitute the

drivers of said motor vehicles special policemen, with the

same powers given to conductors and motormen of electric

railways by general law.” (Acts of Assembly, 1930, Chap.

128, pages 343-344.)

This statute, now appearing as Sections 4097z to 4097dd

of Michie’s Code of Virginia, 1942, requires all passenger-

motor vehicle carriers to separate the white and colored

passengers in their motor busses, and to set apart and desig

nate in each bus seats or portions thereof to be occupied,

respectively, by the races, and constitutes the failure or re

fusal to comply with said provisions a misdemeanor (Sec.

4097z); forbids the making of any difference or discrimina

tion in the quality or convenience of the accommodations so

provided (Sec. 4097aa); confers the right and obligation

upon the driver, operator or other persons in charge of

such vehicle, to change the designation of seats so as to

increase or decrease the amount of space or seats set apart

for either race at any time when the same may be neces

sary or proper for the comfort or convenience of passengers

so to d o ; forbids the occupancy of contiguous seats on the

same bench by white and colored passengers at the same

time; authorizes the driver or other person in charge of the

vehicle to require any passenger to change his or her seat

as it may be necessary or proper, and constitutes the fail

ure or refusal of the driver, operator or other person in

charge of the vehicle to carry out these provisions a mis

demeanor (Sec. 4097dd); constitutes each driver operator

or other person in charge of the vehicle a special police

man, with all of the powers of a conservator of the peace

in the enforcement of the provisions of this statute, the

maintenance of order upon the vehicle and while in pursuit

of persons for disorder upon said vehicle, for violating the

provisions of the act, and until such persons as may be

arrested by him shall have been placed in confinement or

delivered over to the custody of some other conservator of

the peace or police officer, and protects him against the con

sequences of error in judgment as to the passenger’s race,

where he acts in good faith and the passenger has failed to

disclose his or her race (Sec. 4097cc).

Section 4097dd upon which the prosecution in this case

was based, provides that all persons who fail to take seats

assigned to them by the driver or other person assigned to

take up tickets or who fail to obey the directive of the

driver to change seats pursuant to rules and regulations of

the company designed to accomplish the segregation of the

races as required by the statute, having been first advised

of the rule or regulation, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor ;

it is also provided that such person may be ejected from

the bus by any driver or other conservator of the peace

without return of fare paid, and neither the driver nor the

bus company shall be liable for damages for such ejection.

The statute is set out in full in Appendix A to this brief.

The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia in affirming

the conviction of appellant decided that the statute in ques

tion applied to both interstate and intrastate passengers

(E. 56, 68). The statute involved requires all motor vehicles

to segregate passengers according to race regardless of the

effect upon interstate commerce or hardship to carrier and

passenger.

6

Carriers of passengers are precluded by this statute

from exercising judgment or discretion in seating arrange

ments. The rules and regulations of the carrier involved

were required by the statutes of Virginia. The lower court

in its opinion., expressly stated: “ The statute, when read

in its entirety, clearly demonstrates that no power is dele

gated to the carrier to legislate and determine what conduct

shall be considered a crime. The statute simply describes

conditions which must first be found to exist before it be

comes applicable. There is no uncertainty about the con

ditions that must exist before the offense is complete. The

statute itself condemns the defendant’s conduct as a viola

tion o f law and not the rule of the carrier” (E. 67). (Italics

ours.)

In this view of the case it is understandable that the

appellee made no effort to justify the rules and regulations

of the bus company on the basis of reasonableness or ne

cessity other than the requirements of the statutes of Vir

ginia. For all intents and purposes this case stands as if

the rules and regulations adopted pursuant to the statute

became a part of the statute itself.

Errors Relied Upon

I

The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia erred in

rendering judgment affirming the judgment of the Circuit

Court of the County of Middlesex, Virginia, holding that

the statute of the State of Virginia, known as Chapter 128,

Acts of Assembly of 1930, pages 343-344, as applied to

appellant, a passenger traveling on an interstate journey

in a vehicle moving in interstate commerce, is not repug

nant to the provisions of Clause 3 of Section 8 of Article I

of the Constitution of the United States.

7

II

The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia erred in

rendering judgment affirming the judgment of the Circuit

Court of the County of Middlesex, Virginia, holding that

the powers reserved to the States under the Tenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States include the

power to enforce a state statute compelling the racial segre

gation of passengers on public carriers against a person

traveling on an interstate journey in a vehicle moving in

interstate commerce.

Summary of Argument

For seventy years the decisions and pronouncements of

this Court have consistently condemned state statutes at

tempting to control or require the segregation of Negro

passengers moving- in interstate commerce on public car

riers as unconstitutional invasions of an area where na

tional power under the commerce clause is exclusive. Un

less the reasoning of those cases was or is unsound, they

should be followed.

The nature of the subject matter, the direct impact of

segregation statutes on the interstate movement of persons

in commerce, and the burdensome and disruptive effect of

numerous and conflicting local enactments in this field all

indicate the correctness of the doctrine which places this

aspect of interstate commerce beyond state control. The

transitory status of the interstate passenger and the lack

of any uniform or consistent coverage of Negro travelers

in the segregation laws of the several states, including Vir

ginia, show the unsubstantial character of the State’s claim

of legitimate concern with this matter. Such capricious

application of provincial notions beyond substantial local

needs affords no valid basis for the regulation of interstate

commerce which Virginia is attempting.

s

ARGUMENT

I

This Court Has Consistently Asserted That States

Do Not Possess the Authority Which

Virginia Now Asserts

That a state statute seeking to impose a local policy con

cerning racial segregation upon the interstate transporta

tion of passengers on public carriers contravenes the com

merce clause was clearly and decisively established by this

Court in Hall v. DeCuir.1 The state statute there challenged

was construed as guaranteeing to passengers in interstate

commerce equal rights and privileges in all parts of public

conveyances without discrimination on account of race or

color. This Court concluded that state regulation of this

subject matter was inconsistent with the commerce clause.

Great emphasis was placed upon the burdensome effect of

diverse regulations in states with conflicting notions of

racial policy.

The considerations which determined the invalidity of

the statute in Hall v. DeCuir operate equally to render in

valid legislation which seeks to compel a separation of inter

state passengers upon a racial basis. It was the very fact

that one state may attempt to segregate interstate passen

gers in some fashion while an adjoining state may prohibit

such segregation which compelled the Court to declare this

entire subject matter beyond the reach of local law.

Analysis of the cases which have brought various aspects

of racial segregation in commerce before this Court since

1 95 U. S. 485,

9

Hall v. DeCuir reveals consistent recognition and applica

tion of the doctrine of that case. Louisville, N. 0. & T. Ry.

Co. v. Mississippi,2 involved the 1888 statute of Mississippi

which required railroads operating within the state to pro

vide separate but equal accommodations for white and

colored passengers. The Supreme Court of Mississippi had

construed the statute as applying only to intrastate com

merce. This Court discussed and reasserted the principle

of Hall v. DeCuir and made it plain that, had the statute

before it been held applicable to interstate commerce, it

would have been invalid.

The 1890 Louisiana statute, requiring separate but equal

accommodations for the white and colored races on rail

roads, was in question in Plessy v. Ferguson.3 4 The state

court had limited the operation of the law to, intrastate

commerce, and the argument centered around constitutional

provisions other than the commerce clause. The Court dis

cussed Hall v. DeCuir, and pointed out that in the latter

case the vice of the statute was that it affected interstate

commerce, thus indicating that the decision in the Plessy

case would have been different had the statute involved

extended to interstate passengers.

In more recent cases concerning segregation in trans

portation, Chesapeake & 0. Ry. Co. v. Kentucky * Chiles v.

Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co.,5 6 and McCabe v. Atchison,

Topeka and Santa Fe Ry. Co.,3 this Court discussed Hall

v. DeCuir and reaffirmed and restated with approval the

reasoning of that case.

2 133 U. S. 587.

3 163 U. S. 537.

4 179 U. S. 388.

5 218 U. S. 71.

6 235 U. S. 151.

1 0

In South Covington & C. St. Ry. Co. v. Kentucky? de

fendant, a Kentucky corporation, had been authorized by

its charter to operate a street railway in and around Coving

ton, Kentucky, and to acquire and operate any other street

railway in that vicinity which included the City of Cincin

nati, Ohio. Defendant became the owner of all of the stock

of another Kentucky corporation, herein designated as the

“ C” Company, authorized to construct and maintain an

electric railroad between Covington and Erlanger, Ken

tucky, and beyond. Both companies were operated under

the same management and under the <(C” Company’s name.

A fare of five cents was charged for passage upon any point

on the road of the “ C” Company to any point on the system

of the defendant, and transfers were given for all connect

ing lines. Many persons taking passage on the line of the

“ C ” Company in Kentucky were transported without

change of cars into Cincinnati over defendant’s line. Each

terminus, as well as each of the stations, of the “ C” Com

pany, was in Kentucky. Defendant was indicted and con

victed for failure to comply with the Kentucky statute re-

quiiing sepaiate but equal accommodations for the races,

in a car which operated out of Cincinnati but continued

through and beyond Covington, with its Kentucky run over

the “ C” Company route. The defense was that the prin

cipal business of defendant was interstate in character, and

that the statute could not validly apply to it. However,

the Court of Appeals of Kentucky held that the defendant’s

operation over the line of the “ C” Company was a distinct

enterprise within Kentucky to which Kentucky law applied,

pointing out at the same time that the statute had no appli

cation to the transportation of interstate passengers,7 8 and

on this basis affirmed the conviction. This Court made a

7 252 U. S. 399.

8 181 Ky. 449, 205 S. W . 603.

11

similar analysis of the situation and affirmed the judgment.

In the majority opinion it was made plain that the Justices

regarded the subject matter upon which the statute oper

ated as intrastate rather than interstate commerce.9 Mr.

Justice Day, writing for the three dissenting Justices,

pointed out explicitly that

“ It is admitted that this regulation would not ap

ply to interstate passengers, and colored passengers

going from Kentucky to Cincinnati, or going from

Cincinnati to Kentucky on a through trip would not

be subject to the regulation.” 10 11

Not only has Hall v. DeCuir been approved upon those

occasions where this Court has been faced with state laws

concerning racial segregation of passengers, but the deci

sion has frequently been relied upon arguendo in cases

wherein some analogical application of doctrine seemed ap

propriate with respect to other types of state legislation.13

Most recently, in Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona,12 decided

June 18, 1945, this Court stated that “ the commerce clause

has been held to invalidate local ‘ police power’ enact

ments—regulating the segregation of colored passengers in

interstate trains, Hall v. DeCuir

The decisions of other courts likewise reflect substantial

agreement that state laws of the kind involved in the in-

9 252 U. S. at 403, 404.

10 252 U. S. at 407.

11 Missouri v. Kansas Natural Gas Co., 265 U. S. 298, 310; South

Covington & C. St. Ry. Co. v. Covington, 235 U. S. 537, 548; Minne

sota Rate Cases, 230 U. S. 352, 401; Hanley v. Kansas City Southern

Ry. Co., 187 U. S. 617, 620; Louisville & N. R. Co. v. Eubank, 184

U. S. 27, 40; Cleveland, C. C. & St. L. Ry. Co. v. Illinois, 177 U. S.

514, 518; Rhodes v. Iowa, 170 U. S. 412, 424; Covington & C. Bridge

Co. v. Kentucky, 154 U. S. 204, 215 ; Bowman v. Chicago & N. W . R.

Co., 125 U. S. 465, 486; Western Union Tel. Co. v. Pendleton, 122

U. S. 347, 357; Wabash, St. L. & P. Ry. Co. v. Illinois, 118 U. S.

557, 565.

12 325 U. S. 761.

12

stant case cannot constitutionally be applied to passengers

traveling in interstate commerce. This conclusion lias been

reached in all of the inferior federal courts which have

considered the matter,13 and in a majority of the state

courts as well.14 Analysis of these cases reveals consistency

in recognition of the basic considerations underlying the

decision in Hall v. DeCuir, that the national interest in the

freedom of interstate commerce from diverse and conflicting

requirements as to rearrangement of passengers must pre

vail over local notions of racial policy.

The rationale of this entire line of decisions is so clearly

spelled out in Hart v. State, that quotation from that opinion

seems appropriate:

“ Although the state has power to adopt reason

able police regulations to secure the safety and com

fort of passengers on interstate trains while within

its borders, it is well settled, as we have seen, that

it can do nothing which will directly burden or im

pede the interstate traffic of the carrier, or impair

the usefulness of its facilities for such traffic. When

the subject is national in its character and admits

and requires uniformity of regulation affecting alike

all the states, the power is in its nature exclusive,

and the state cannot act. The failure of Congress

to act as to matters of national character is, as a rule,

equivalent to a declaration that they shall be free

from regulation or restriction by any statutory en

actment, and it is well settled that interstate com

13 Washington, B. & A . Ry. v. Waller, S3 App. D. C. 200, 289

Fed. 598; Tompkins v. Missouri, K . & T. Ry., 211 Fed. 391 (C. C.

A. 8 th ); Anderson v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 62 Fed. 46 (C. C. Ky.) •

Brown v. Memphis & C. R. Co., 5 Fed. 499 (C. C. Term.).

14 State g* rel. Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770, 11 So. 74; Hart

v. State, 100 Md. S9S, 60 Atl. 457; Carrey v. Spencer, 36 N. Y.

Supp. 886; State v. Galveston H. & S. A . Ry. Co. (Tex. Civ. App.)'

184 S. W . 227; Huff v. Norfolk-Southern R. Co., 171 N. C. 203, 88

S. E. 344. Contra: Illinois Central R, Co. v. Redmond, 119 Miss. 765

81 So. 115; Smith v. State, 100 Tenn. 494, 46 S. W . 566.

13

merce is national in its character. Applying these

general rules to the particular facts in this case, and

bearing in mind the application of the expressions

used in Hall v. DeCuir to cases involving questions

more or less analogous to that before us, we are

forced to the conclusion that this statute cannot be

sustained to the extent of making interstate passen

gers amenable to its provisions. When a passenger

enters a car in New York under a contract with a

carrier to be carried through to the District of Co

lumbia, if when he reaches the Maryland line, he

must leave that car, and go into another, regardless

of the weather, the hour of the day or the night, or

the condition of his health, it certainly would, in

many instances, be a great inconvenience and pos

sible hardship. It might be that he was the only

person of his color on the train, and no other would

get on in the State of Maryland, but he, if the law

is valid against him, must, as soon as he reaches the

state line, leave the car he started in, and go into

another, which must be furnished for him, or sub

ject himself to a criminal punishment. Or take, for

illustration, the Cumberland Valley Railroad from

Winchester, Va., to Harrisburg, Pa. In Virginia a

law of this kind is in force, while in West Virginia

and Pennsylvania there is none, as far as we are

aware. On a train starting from Winchester the

passengers must be separated according to their

color for six or eight miles, when it reaches the West

Virginia line, then through West Virginia they can

mingle again until they reach the Potomac, when

they would be again separated, and so continue until

they reach Mason and Dixon’s line, when they are

again permitted to occupy cars without regard to

their color. If the railroad company did not deem

it desirable or proper to have separate compartments

throughout the journey—and oftentimes it might be

wholly unnecessary for the comfort of the passengers

on said trains, as there might be very few colored

persons on them—there would be at least three

14

changes in that short distance. We cannot say, there

fore, that, as applied to interstate passengers, such

a law as this would be so free from the objections

pointed out in the cases above mentioned as to be

sustained under the police powers of the states.” 15 16 17

The Commonwealth of Virginia is now asserting that

the decision in Hall v. DeCuir and the impressive line of

decisions and pronouncements following that case for

seventy years and as recently as June, 1945, were ill con

sidered.

II

Regulations Concerning Racial Segregation in Inter

state Commerce Fall Within the Area of Exclu

sive National Power as Judicially Defined

Underlying Hall v. DeCuir and the cases which follow

it is the conception that the free movement of persons in

interstate commerce may not be obstructed or interfered

with by state legislation predicated upon provincial notions

of social policy. It was the very design and object of the

commerce power “ to prevent unjust and invidious distinc

tions, which local jealousies or local and partial interests

might be disposed to introduce and maintain.” 18 This is

sound doctrine consistent with judicial exposition and

analysis of the commerce power as developed over more

than a century.

From Gibbons v. Ogden17 in 1824 to Southern Pacific

Co. v. Arizona18 in 1945, this Court has made it clear that

15 100 Md. at 612-613, 60 Atl. at 462-3.

16 See Veazie v. Moor, 14 How 568, 574.

17 9 Wheat. 1.

18 325 U. S. 761.

15

an obvious and basic purpose of the commerce clause is to

prevent the interruption or disruption of the actual move

ment of persons and property across state lines by local

obstacles and impediments. Except where the local imposi

tion is a reasonable corrective of a clear and substantial

hazard to the local community created by the interstate

movement itself,19 this Court has consistently disapproved

such local interference.20 The language of the court in

Kelly v. Washington is apposite and reflects a point of view

which characterizes the decisions:

“ In such a matter [insuring the safety of tug

boats] the State may protect its people * * *. If,

however, the State goes further and attempts to im

pose particular standards as to structure, design,

equipment and operation which in the judgment of

its authorities may be desirable but pass beyond

what is plainly essential to safety and seaworthiness,

the State will encounter the principle that such re

quirements, if imposed at all, must be through the

action of Congress which can establish a uniform

rule.” 21

In this connection, it seems important to note that while

this Court on occasion has questioned certain of its own

earlier distinctions between direct and indirect impositions

upon commerce, the fact that exercise of control over inter

19 E. G .: South Carolina Highway Dept. v. Barnwell Bros., Inc.,

303 U. S. 177; Erie R. R. v. Public Utility Commissioners, 254 U. S.

394; Morgan’s L. & T. R. R. & Steamship Co. v. Louisiana, 118

U. S. 455.

20 Buck v. Kuykendall', 267 U. S. 307; Pennsylvania v. West Vir

ginia, 262 U. S. 553; Chicago B. & Q. R. Co. v. Railroad Commis

sion of Wisconsin, 237 U. S. 220; Bowman v. Chicago & N. W . R.

Co., 125 U. S. 465; South Covington & C. St. Ry. Co. v. Covington,

235 U. S. 537; Wabash St. L. & P. Ry. Co. v. Illinois, 118 U. S. 557.

21302 U. S. 1.

16

state commerce is the very purpose and object of a ques

tioned state statute and that its enforcement is achieved

by interference with interstate movement itself, militate

strongly against the validity of the statute. This is because

such impact necessarily involves some invasion of the na

tional interest in maintaining the freedom of commerce

across state lines. If this fact alone is not conclusive, it

at least suffices to establish the impropriety of the state

regulation until and unless it is shown that urgent con

siderations of local welfare take a particular case out of

the general rule.22

This aspect of the present case is especially noteworthy.

Not only does the statute require a particular arrangement

or rearrangement of interstate passengers while traveling

through Virginia, but it accomplishes this result by a crimi

nal sanction, the invocation of which completely interrupts

the interstate movement and brings about the seizure and

incarceration of the person who insists upon the peaceful

and uninterrupted progress of his interstate journey. Thus

the very analysis of the incidence and effect of the statute

reveals so direct and serious an imposition upon interstate

travel as to place upon the State an extremely heavy burden

of justification which it is submitted the State has not met

and cannot meet.

Beyond the foregoing considerations, the free movement

of citizens of the United States throughout the nation is a

22 p or such approach and analysis see Pennsylvania v. West Vir

ginia, 262 U. S. 5S3, particularly at 596-7. In Di Santo v. Pennsyl

vania, 273 U. S. 34, it is believed that the divergence of majority and

dissenting opinions is essentially whether the at least prima facie case

of invalidity arising from the direct impact of the regulation on inter

state commerce may be rebutted by a showing that there is grave

local need for such regulation.

17

matter of special concern to the national sovereign. The

privileges and immunities clause of the 14th amendment

elevates this right of free movement to the dignity of a

constitutional guaranty.23 Where a subject matter is of

such primary national concern, its involvement in a particu

lar local interference with commerce makes it doubly im

perative that national authority over this aspect of com

merce be held exclusive. While the majority opinion in

Edwards v. California did not allude to the constitutional

privilege and immunity of free travel under the Fourteenth

Amendment, it is believed that the incidence of the statute

upon conduct in the area of this privilege is a fundamental

consideration leading to the result reached in that case and

a like result here.

A. State Statutes in This Field Are So Numerous

and Diverse That Their Imposition on Inter

state Commerce Would Be an Intolerable

Burden

The impact of the present statute should properly be

considered in the light of the cumulative effect of similar

statutes in Virginia and elsewhere upon interstate passen

ger travel. The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

properly and correctly pointed out in its opinion in the

present case that not only motor vehicles but other public

carriers and the passengers thereon passing through the

State are affected by similar statutory requirements of

racial segregation:

“ The public policy of the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia, as expressed in the various legislative Acts, is

23 Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. 35; cf. concurring opinion in

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 177.

18

and has been since 1900 to separate the white and

Negro races on public carriers. As to railroads, see

Acts of 1906, pages 236 and 237, carried in Michie’s

Code of 1942 as secs. 3962-3968; as to steamboats,

see Acts of 1900, page 340, carried in Michie’s Code

1942 as secs. 4022-4025; as to electric or street cars,

see Acts of 1902-03-04, page 990, carried in Michie’s

Code 1942 as secs. 3978-3983, and as to motor vehicles

see Acts of 1930, pages 343 and 344, carried in

Michie’s Code of 1942 as secs. 4097z, 4097aa, 4097bb,

4097cc, and 4097dd.” (R. 60).

It is believed that this Court will take judicial notice of

the fact that the State of Virginia extending from the

Atlantic Ocean to the western mountain barrier of the

Atlantic coastal plain is so located geographically as to

require the entire body of north and south travel along the

populous eastern seaboard to pass through that State. It

is also to be noticed that all persons traveling south and

southwest from the National Capital or traveling to the

Capital from those directions must pass through Virginia.

Thus a very substantial proportion of interstate passenger

travel in America is necessarily affected by the attempted

exercise of local policy which is here challenged.

Moreover, the variety and contrariety of policies and

enactments of the several states with reference to segrega

tion or non-segregation, as well as the variety and uncer

tainty of local rules determining the race of an individual

make it clear that the burden imposed upon and the con

fusion introduced into interstate travel by the enforcement

of multitudinous and uncertain regulations in the course of

a single journey are tremendous.

Legislation affecting these questions is widespread and

diverse in language and construction and the subject of

19

frequent change. Eighteen states have adopted so-called

“ Civil Bights Acts” prohibiting segregation on account of

race or color against persons using certain public facil

ities, including public carriers.24 On the other hand, other

states have enacted laws requiring the segregation of races

upon railroad trains,25 26 * street cars,28 motor vehicle car

24Cal. Civ. Code (Deering), 1941, Sec. 51-54; Colo. Stats., 1935

Ch. 35, Sec. 1-10; Conn. Gen. Stat. (Supp. 1933) Sec. 1160b; 111.

Rev. Stat., 1941, Ch. 38, Sec. 125-128g; Ind. Stat. (Burns), 1933,

Sec. 10-901, 10-902; Iowa Code, 1939, Sec. 13251-13252; Kan. Gen.

Stat., 1935, Sec. 21-2424; Mass. Laws (Michie), 1933, Chap. 272,

Sec. 98, as amended 1934; Mich. Comp. Laws (Supp. 1933), Sec.

17, 115-146 to 147; Minn. Stat. (Mason), 1927, Sec. 7321. Neb.

Comp. Stat., 1929, Ch. 23, Art. 1; N. J. Rev. Stat., 1937, Sec. 10:1-1

to 10:1-9; N. Y. Laws (Thompson), 1937, ,(1942, 1943, 1944

Supp.), Ch. 6, Sec. 40-42; Ohio Code (Throckmorton), 1933, Sec.

12940-12941; Pa. Stat. (Purdon), Tit. 18, Sec. 1211, 4653 to 4655;

R. I. Gen. Laws, 1938, Ch. 606, Sec. 27-28, Ch. 612, Sec. 47-48;

Wash. Rev. Stat. (Remington), 1932, Sec. 2686; Wis. Stat., 1941,

Sec. 340.75. See also Me. Rev. Stat., 1930, Ch. 134, Sec. 7-10;

N. H. Rev. Laws, 1942, Ch. 208, Sec. 3-4, 6.

25 Ala. Code, 1940, Tit. 48, Sec. 196-197; Ark. Stat.. 1937

(Pope), Sec. 1190-1201; Fla. Stat., 1941, Sec. 352.03-352-06; Ga.

Code, 1933, Sec. 18-206 to 18-210, 18-9901 to 18-9906; Ky. Rev.

Stat. (Baldwin), 1942, Sec. 276.440; La. Gen. Stat. (Dart), 1939,

Sec. 8130-8132; Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 510-516;

Miss. Code, 1942, Sec. 7784; N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943, Secs. 60-94 to

60-97; 13 Okla. St. Ann. 181-190; S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8396 to

8400-2; Tenn. Code (Michie), 1938, Sec. 5518-5520; Tex. Rev. Civ.

Stat. (Vernon), 1936, Art. 6417; Tex. Pen. Code (Vernon), 1936,

Art. 1659-1660; Va. Code (Michie), 1942, Sec. 3962-3968.

26 Ark. Stat., 1937 (Pope), Sec. 1202-1207; Fla. Stat, 1941, Sec.

352.07-352.15; Ga. Code, 1933, Sec. 18-206 to 18-210, construed to

include street railways; La. Gen. Stat. (Dart), 1939, Sec. 8188-

8189; Miss. Code, 1942, Sec. 7785; N. C. Gen. Stat., 1943, Sec.

60-135 to 60-137; 13 Okla. Stat. 181-190; S. C. Code, 1942, Sec.

8490-8498; Tenn. Code (Michie), 1938, Sec. 5527-5532; Tex. Rev.

Civil Stat. (Vernon), 1936, Art. 6417; Tex. Penal Code (Vernon),

1936, Art. 1659-1660; Va. Code, 1942, Sec. 3978-3983.

2 0

riers 27 and steamboats.28 If all these laws can validly be

applied to interstate commerce, the very prophesy in Hall

v. DeCuir becomes a realty.

Furthermore, there is no uniformity even as respects

the applicability of the several existing segregation laws to

interstate transportation. Before the Virginia decision in

the instant case, only two states, Tennessee and Missis-

sippi, had held that their laws could affect interstate trav

elers; elsewhere they had been construed, in appropriate

cases, as limited in their operation to passengers in intra

state commerce. Assuming a trip from the District of

Columbia to Louisiana through Virginia, Kentucky, Ten

nessee, Alabama, and Mississippi, within the District of

Columbia all passengers have the free run of the vehicle.

But when Virginia is entered, passengers must move to

comply with the statute under consideration. As soon, how

ever, as Kentucky is reached, the interstate passenger

regains his power of choice as to seats.29 When the vehicle

27 Ala. Code, 1940, Tit. 48, Sec. 268; Ark. Stat., 1937 (Pope),

Sec. 6921-6927, Laws 1943, p. 379; Fla. Stat., 1941, Sec. 352.03-

352.08; Ga. Code, 1933, Sec. 68-61£; La. Gen. Stat. (Dart), 1939,

Sec. 5307-5309 ; Miss. Code, 1942, Sec. 7785; N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943’

Sec. 62-109; 47 Okla. Stat. Ann., 201-210; S. C. Code, 1942, Sec.

8530 (1 ) ; Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. (Vernon) 1936, Art. 6417; Tex. Pen.

Code (Vernon) 1936, Art. 1661.1; Va. Code, 1942, Sec. 4097z-

4097dd.

28 Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 517-520; N. C. Gen.

Stat., 1943, Sec. 60-94 to 60-97; S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 8396; Va

Code, 1942, Sec. 4022-4026.

29 The Kentucky statutes have consistently been construed as

limited in operation to intrastate passengers. South Covington & C. St.

Ry. Co. v. Commonwealth, 181 Ky. 449, 205 S. W . 603; Chiles v.

Chesapeake & O. Ry. Co., 125 Ky. 299, 101 S. W . 386; Ohio Valley

Ry.’s Receiver v. Lander, 104 Ky. 431, 47 S. W . 344; Chesapeake &

O. Ry. Co. v. State, 21 Ky. L. 228, 51 S. W . 160.

2 1

passes into Tennessee, the interstate passenger is again

segregated.30 When the vehicle crosses the line into Ala

bama, he is not subject to the segregation statute in

Alabama which expressly excepts from its interdictions

passengers in interstate commerce who started their jour

ney in jurisdictions not having segregation statutes.31 32 In

Mississippi, segregation is again invoked, but entering into

Louisiana the local segregation statute is once more inap

plicable. The consequence of these numerous shifts, of the

precedent arrangements which must be made to bring them

about, and the administration of the details in accomplish

ing them, cannot be otherwise than burdensome to the

national commerce and those engaged therein. It is also

to be noted that the mechanics of segregation may differ

greatly among the states requiring it.

There is no uniformity as to the type of transportation

affected by the regulations of the individual states. Vir

ginia and three other jurisdictions except express trains ;33

two except narrow gauge and branch lines;33 one excepts

relief trains;34 35 one excepts excursion trains;85 one permits

special trains for the members of either race where regular

30 The Tennessee statute was construed to apply to interstate pas

sengers in Svrith v. State, 100 Tenn. 494, 46 S. W . S66.

31 Ala. Code, 1940, Title 48, Sec. 197.

32 Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 516; N. C. Gen. Stat,

1943, Sec. 60-94; S. C. Code (1932) Sec. 8399; Va. Code Ann.

(Michie, 1930) Sec. 3968.

33 N. C. Gen. Stat., 1943, Sec. 60-95 (consent of Utilities Com

mission necessary) ; S. C. Code (1932) Sec. 8399.

34 N. C. Gen. Stat., 1943, Sec. 60-94.

35 Tex. Ann. Rev. Civ. State. (Vernon, 1925) Art. 6417, Tex.

Ann. Pen. Code (Vernon, 1925) Art. 1660.

2 2

schedules are not interfered with ;* 37 38 and Virginia and seven

other states except freight trains and cabooses.37

Unlike the antithetical Civil Rights Acts, segregation

laws require, as a condition to their operation, a division

of peoples upon a basis of race and, as a necessary con

comitant thereof, a means whereby the division may be ac

complished. Dissimilarity in definition of the persons to be

affected by the law produces in turn a geographical dis

similarity in the operation of the several laws to the extent

that carrier and passenger alike are seriously burdened,

confused and embarrassed. An examination of the law

of the states where legislative or judicial efforts in this di

rection have been made reveals that there is much diversity

and conflict in the rules governing the proportion of “ Negro

blood” necessary to classify a person as a “ Negro” or

“ colored person” .38

The terms “ colored person” and “ Negro” have been

variously defined as including all persons in whom there is

38 13 Okla. Stat. Ann. 189.

37 Ark. Stat., 1937 (Pope), Sec. 1201; Ky. Stat. Ann. (Carroll,

1930) Sec. 801; Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 516; 13 Okla.

Stat. Ann. 187; S. C. Code (1932) Sec. 8399 (applies to freights

with one passenger coach attached for local travel) ; Tenn. Code

(Michie), 1938, Sec. 5518 (if passenger coach is carried, the races

must be separated) ; Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. (Vernon, 1936) Art. 6417,

Tex. Pen. Code (Vernon, 1936) Art. 1660; Va. Code Ann. (Michie^

1930) Sec. 3968. In North Carolina the Utilities Commission may

allow certain lines that run mixed trains to disregard the statute

because of the small number of Negro passengers. N. C. Gen Stat

1943, Sec. 60-95.

38 Some states have defined the terms by a general statute. Others

have defined them only with respect to particular subjects. In some

states, the definition varies according to the subject under considera

tion, so that a person may be classified as a colored person or Negro

for one purpose and as a white person for another. In states where

no statutory definition has been attempted, the courts are faced with

the difficulty of deciding the query as best they can.

23

ascertainable any quantum of “ Negro blood’ ’ whatever,39

or all persons of Negro or African descent,40 or only those

persons who are of “ Negro blood” to the third generation

inclusive,41 or the fourth generation inclusive,42 or who have

one-fourth43 or one-eighth44 * * or more “ Negro blood” . The

range is so great that the same person making an inter

state trip may be a Negro or colored person in one state

through which he passes and a white person in another and

consequently may find himself faced with a criminal prose

cution because of a noncompliance with local laws necessi

tating a change of accommodations to conform to his chang

ing legal status.

Moreover, the definitions within the same state are fre

quently conflicting. Aside from those states which have a

39 Ala. Code, 1940, Tit. 1, Sec. 2 and Title 14, Sec. 360; Ark. Stat.

(Pope), 1937, Sec. 3290 (concubinage statute) and Sec. 1200 (sep

arate coach la w ); Ga. Laws, 1927, p. 272; Ga. Code (Michie Supp.)

1928, Sec. 2177; N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943, Sec. 115-2 (separate school

law ); Tenn. Code (Michie) 1938, Sec. 8396; Va. Code (Michie),

1942, Sec. 67.

40 Okla. Const., Art. X X III, Sec. 11; Art. X III, Sec. 3; 43 Okla.

Stat. Ann. 12 (inter-marriage law) ; 70 Okla. Stat. Ann. 452 (sep

arate school law) ; 13 Okla. Stat. Ann. 183 (separate coach law) ;

Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. (Vernon), 1936, Art. 2900 (separate school

law) ; Art. 6417 (separate coach la w ); Art. 4607 (inter-marriage

law ).

41 Md. Code (Flack), 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 445 (intermarriage);

N. C. Const., Art. X IV , Sec. 8 (marriage) ; N. C. Gen. Stat., 1943,

Sec. 51-3 and 14-181 (marriage law) ; Tenn. Const., Art. X I, Sec.

14 (miscegenation) ; Tenn. Code (Michie), 1938, Sec. 8409 (mis

cegenation) ; Tex. Pen. Code (Vernon), 1936, Sec. 493 (miscege

nation).

42 Fla. Const., Art. X V I, Sec. 24 (marriage).

43 Ore. Comp. Laws, 1940, Sec. 23-1010 (intermarriage).

44 Fla. Stats., 1941, Sec. 1.01 (6 ) ; Ind. Stat. (Burns), 1933, Sec.

44-104 (intermarriage) ; Miss, Const., Sec. 263, Miss. Code, 1942,

Sec. 459 (intermarriage) ; Mo. Rev. Stat. 1939, Sec. 4651 (inter

marriage) ; N. D. Rev. Code Secs. 14-0304 and 14-0305 (inter

marriage) ; Ore. Comp. Laws, 1940, Sec. 23-1010 (intermarriage) ;

S. C. Const., Art. I l l , Sec. 33 (intermarriage).

24

general statute defining the terms, only three have been

found wherein the legislative definition is specifically ap

plicable to the transportation segregation laws.45 Assum

ing that the definition in an act covering another field of

activity may be used as a pointer to show the general mean

ing of the terms in that jurisdiction, this course has not

always been followed.48 Besides, in some instances, two

conflicting definitions are to be found in the law of a single

state,47 in each of which instances the applicable criterion

as to transportation segregation is speculative. Since one

cairier may follow one rule, and another carrier the other,

and a third carrier a third rule with equal justification in

the light of the ambiguous character of the law, the harmoni

ous flow of interstate traffic can never be assured.

4" Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas. See ante, footnotes 39 40. See

also Lee v. New Orleans G. N. Ry., 125 La. 236, 51 S. 182.

48 Compare Tucker v. Blease, 97 S. C. 303, 81 S. E. 668 with

Moreau v. Grandich, 114 Miss. 560, 75 S. 434.

Alabama. The Constitution, Sec. 102, formerly prohibited mar

riages of whites and persons of Negro blood no matter how remote

the strain, while the marriage law (Code, 1923, Sec. 5001) only pro

hibited marriages ̂of whites with persons of Negro blood to the third

generation inclusive. This conflict was not removed until 1927 bv

Acts, 1927, p. 219. y

Tennessee: Two statutes define the term “ Negro” or “ a person

of color” as including every person who has any Negro blood in his

veins (footnote 39) while the constitutional provision and the stat

ute forbidding interracial marriages (footnote 41) only prohibit the

union of whites and persons who have Negro blood to the third

generation inclusive.

1 exas: The separate school law, separate coach law, and inter

marriage law all define the terms as including any descendant from

Negro ancestry (footnote 39), but the penal statute punishing mis

cegenation defines the term “ Negro” as including only those persons

who are of Negro blood to the third generation inclusive.

Kentucky: See footnote 48.

Florida : See footnote 48.

25

Furthermore, the definitions are subject to change at

any time and have frequently been changed in the past.48

48Alabama: Prior to 1927, the marriage law forbade marriages

of whites with persons of Negro blood to the third generation in

clusive. Ala. Code, 1923, Sec. S001. This rule was changed in 1927

(footnote 47, supra) in order to conform the statute to the consti

tutional provision.

Florida: Two statutes define the word “ Negro” in such manner

as to embrace only those who have one-eighth or more Negro blood

(footnote 44), but the constitution (footnote 42) prohibits inter

racial marriages to the “ fourth generation inclusive.”

Georgia: Until 1927, a person was classified as colored only if

he had one-eighth or more Negro blood. Ga. Code (Michie), 1926,

Sec. 2177. In that year the definition was changed to include any

person having any ascertainable portion of Negro blood (see foot

note 39).

Kentucky: This State has no statutory definition. It was early

held that the old Virginia law providing that all persons having one-

fourth or more Negro blood were to be classified as colored persons

has been carried over into Kentucky at the time that State was

carved out of territory belonging to Virginia. Gentry v. McMinnis,

33 Ky. 382. However, in Mullins v. Belcher, 142 Ky. 673, 143 S. W.

1151, it was held that a child having one-sixteenth Negro blood

could not attend a white school, the court holding that any child

having an appreciable amount of Negro blood is colored. Never

theless, it has been decided that a person who looks white, has straight

hair, is of a copper complexion, and has other characteristics of a

white person is not a mulatto within the statute prohibiting the mar

riage of whites and Negroes or mulattos. Theophanis v. Tlieophanis,

244 Ky. 689, 57 S. W . (2d) 957.

Louisiana: It was first held in this state that all persons, includ

ing Indians, who were not of the white race were “ colored.” Adelle

v. Beaugard, 1 Mart. 183. In 1910, it was held that anyone having

an appreciable portion of Negro blood was a member of the colored

race within the meaning of the segregation law. Lee v. New Orleans

G. N. Ry., 125 La. 236, 51 S. 182, supra footnote 45. In the same year,

however, it was decided that an octoroon was not a member of the

Negro or black race within the meaning of the concubinage law (La.

Act, 1908, No. 87). State v. Treadaway, 126 La. 300, 52 S. 500.

Shortly after the latter decision, the present concubinage statute was

enacted substituting the word “ colored” for “ Negro.” La. Acts,

1910, No. 206, La. Crirn. Code (Dart), 1932, Art. 1128-1130. The

effect of the change is yet to be determined.

( Continued on page 26)

26

Commerce is thus subjected to additional harassment at

the hands of state legislatures whose every attempt at re

definition produces an increased burden upon passenger

and carrier alike.

Involving, as it did, a statute forbidding segregation,

this additional hazard was not drawn into issue in Hall v.

DeCuir. Legislative definition of the terms in question is

a later and comparatively modern development. However,

the ever-increasing danger to commerce stemming from the

unstable meaning of a vital factor in the general segrega

tion plan adds mightily to the conclusion there reached.

B. The Racial Arrangment of Interstate Passengers

Within a Vehicle in Transit Across a State Is Not

a Matter of Substantial Local Concern

The burden of the statute here upon interstate commerce

as hereinbefore elaborated is to be contrasted with the un

substantial character of the state’s claim of interest in the

subject matter. We are concerned here merely with persons

in transit through a state in a vehicle. Such persons are

in no sense integrated into the local community. Their

mere passage through the state does not menace any legiti

mate local interests. It is to be remembered that the peace

and good order of the passengers does not make the statute

inoperative. There is no reason to apprehend that the

normal power of the state to enact and enforce criminal

(Continued from page 25)

North Carolina: _ On the issue of what children of mixed blood, if

any, should be permitted to attend white schools, it was held in Hare

v. Board of Education, 113 N. C. 10, 18 S. E. 55, that the definition

employed in the marriage law would be determinative. This was

changed in 1903 by a statute providing that no child with Negro blood

m his veins should attend a white school. N. C. Pub Laws 1903

Ch. 435, Sec. 22; N. C. Gen. Stats., 1943, Sec. 115-20.

Virginia: Va. Code, 1887, Sec. 49, provided that those who had

one-fourth or more Negro blood were to be considered colored This

was changed in 1910 (Acts, 1910, p. 581) to read one-sixteenth or

more. It was again changed in 1930 by Acts, 1930, p. 97, to its pres

e t form. See footnote 39. Virginia also has a race registration act.

Va. Code, 1942 (Michie) Sec. 5099a.

27

laws concerning breaches of the peace is inadequate to con

trol the behavior of travelers. Indeed the very tendency of

enforced rearrangement of passengers as they travel from

state to state is to create disorder and dissension.

In this connection it is particularly noteworthy that in

Virginia itself and throughout the southern states where

segregation statutes are in force so many situations are ex

cepted from their operation as to make clear that there is

no pressing need for them.

The Virginia statute requiring segregation in railroad

coaches expressly exempts sleeping cars and chair cars.49 50

Thus on a single train some Negroes are segregated and

others are not. The Virginia statutes are silent concerning

any racial arrangements on dining cars. The entire field

of transportation by air is free of racial regulation.

Exceptions in other states are even more striking. The

very group of persons now under discussion, those traveling

in interstate commerce, is beyond the reach of state seg

regation laws in most southern states either by specific

statutory exclusion or judicial construction .so There is no

evidence that domestic order or well being has suffered

thereby.

The exemption of first-class passengers from segrega

tion is of frequent occurrence.51 In Texas those riding on

excursion trains need not be segregated.52 Thus, neither

those occupying the most expensive accommodations nor the

cheapest have required segregation to preserve local tran

quility.

Provincial notions thus capriciously applied cannot be

founded on any basic local need. Their imposition upon

interstate commerce is wholly without justification.

49 Va. Code (Michie), 1942, Sec. 3968.

50 See notes 13 and 14 supra, p. 12.

51 Md. Code (Flack) 1939, Art. 27, Sec. 510; N. C. Gen. Stats.

1943, Sec. 60-94; Texas Rev. Civ. Stats. (Vernon, 1936), Art. 6417,

4477; Virginia Code (Michie), 3928, 1942.

52 See note 35.

28

Conclusion

Hall v. DeCuir was decided seventy years ago, and many

of the cases following it are also precedents of past gener

ations. Today, commerce is vastly increased. It has far

greater need than ever.before for freedom from obstacles

bred of provincialism. Moreover, Hall v. DeCuir was de

cided when the Civil War and the racial antagonisms

attendant to it were fresh in the minds and emotions of

men. Even then this Conrt was quite sure that the nation

to the exclusion of the states, must have control of this

aspect of interstate travel. Today we are just emerging

from a war in which all of the people of the United States

were joined in a death struggle against the apostles of

racism. We have already recognized by solemn subscrip

tion to the Charter of the United Nations, particularly

Articles One and Fifty Five thereof, our duty, along with

our neighbors, to eschew racism in our national life and to

promote “ universal respect for, and observance of, human

rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction

as to race, sex, language, or religion.” How much clearer,

therefore, must it be today, than it was in 1877, that the

national business of interstate commerce is not to be dis

figured by disruptive local practices bred of racial notions

alien to our national ideals, and to the solemn undertakings

of the community of civilized nations as well.

It is respectfully submitted that the judgment

appealed from should be reversed.

W illiam H. H astie,

L eon A. R ansom,

T hurgood Marshall,

Attorneys for Appellant.

Spottswood W. R obinson, 3rd,

Of Counsel.

29

APPENDIX A

Michie— Virginia Code

4097z. Segregation of W hite and Colored P assengers.—

All passenger motor vehicle carriers, operating under the

provisions of chapter one hundred and sixty-one (a) of the

Code of Virginia, shall separate the white and colored pas

sengers in their motor busses and set apart and designate in

each bus or other vehicle, a portion thereof, or certain seats

therein, to be occupied by white passengers, and a portion

thereof or certain seats therein, to be occupied by colored

passengers, and such company or corporation, person or

persons that shall fail, refuse or neglect to comply with the

provisions of this section shall be guilty of a misdemeanor,

and upon indictment and conviction, shall be fined not less

than fifty dollars nor more than two hundred and fifty dol

lars for each offense. (1930, p. 343.)

4097aa. D iscrimination P rohibited.—

The said companies, corporations or persons so operat

ing motor vehicle carriers shall make no difference or dis

crimination in the quality or convenience of the accommoda

tions provided for the two races under the provision of the

preceding section. (1930, p. 343.)

4097bb. D river May Change D esignation of S eats.—

The driver, operator or other person in charge of any

motor vehicle above mentioned, shall have the right, and he

is hereby directed and required at any time when it may be

necessary or proper for the comfort and convenience of

passengers so to do, to change the designation so as to in

crease or decrease the amount of space or seats set apart

for either race; but no contiguous seats on the same bench

30

shall be occupied by white and colored passengers at the

same time; and said driver, operator or other person in

charge of the vehicle, may require any passenger to change

his or her seat as it may be necessary or proper; the driver,

operator or other person in charge of said vehicle who shall

fail or refuse to carry out the provisions of this section shall

be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction

thereof shall be fined not less than five dollars nor more

than twenty-five dollars for each offense. (1930, p. 343.)

4097cc. D rivers are Special P olicemen W ith P owers

op Conservators of the P eace.—

Each driver, operator or person in charge of any vehicle,

in the employment of any company operating the same,

while actively engaged in the operation of said vehicle, shall

be a special policeman and have all of the powers of con

servators of the peace in the enforcement of the provisions

of this act, and in the discharge of,his duty as special police

man, in the enforcement of order upon said vehicles; and

such driver, operator or person in charge of said vehicle

shall likewise have the powers of conservators of the peace

and of special policemen while in pursuit of persons for dis

order upon said vehicles, for violating the provisions of

this act, and until such persons as may be arrested by him

shall have been placed in confinement or delivered over to

the custody of some other conservator of the peace or police

officer; and, acting in good faith, he shall be for the pur

poses of this chapter, the judge of the race of each pas

senger whenever such passenger has failed to disclose his

or her race. (1930, p. 344.)

31

4097dd. V iolation by P assengers; M isdemeanor;

E jection.—

All persons who fail while on any motor vehicle carrier,

to take and occupy the seat or seats or other space assigned

to them by the driver, operator or other person in charge

of such vehicle, or by the person whose duty it is to take up

tickets or collect fares from passengers therein, or who fail

to obey the directions of any such driver, operator or other

person in charge, as aforesaid, to change their seats from

time to time as occasions require, pursuant to any lawful

rule, regulation or custom in force by such lines as to as

signing separate seats or other space to white and colored

persons, respectively, having been first advised of the fact

of such regulation and requested to conform thereto, shall

be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction

thereof shall be fined not less than five dollars nor more

than twenty-five dollars for each offense. Furthermore,

such persons may be ejected from such vehicle by any

driver, operator or person in charge of said vehicle, or

by any police officer or other conservator of the peace; and

in case such persons ejected shall have paid their fares upon

said vehicle, they shall not be entitled to the return of any

part of same. For the refusal of any such passenger to

abide by the request of the person in charge of said vehicle

as aforesaid, and his consequent ejection from said vehicle,

neither the driver, operator, person in charge, owner, man

ager nor bus company operating said vehicle shall be liable

for damages in any court. (1930, p. 344.)

"€lSls“212 [5038]

L awyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C .; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300