Affidavit of Harry F. Garrett

Public Court Documents

August 20, 1969

11 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Affidavit of Harry F. Garrett, 1969. bbabf898-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b8daa0a6-4a71-4b66-a8d1-0e140027cda6/affidavit-of-harry-f-garrett. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Z

x A

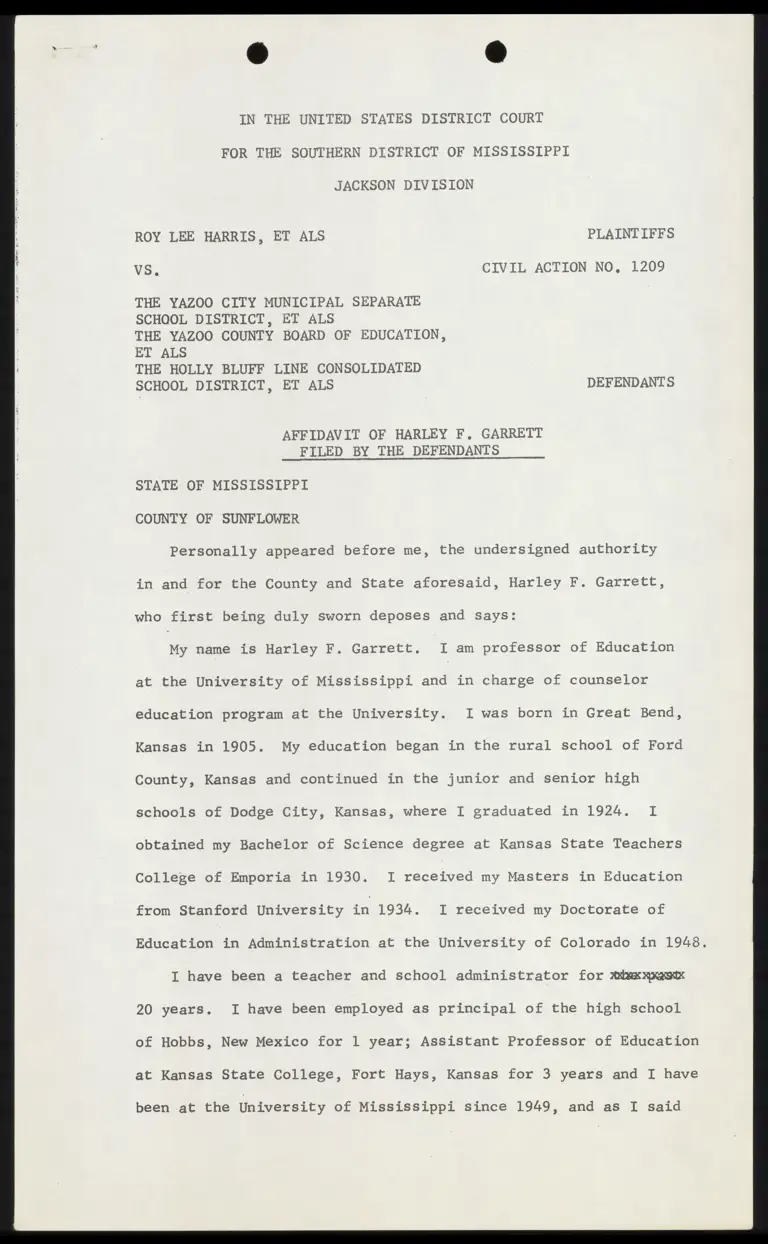

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

JACKSON DIVISION

ROY LEE HARRIS, ET ALS PLAINTIFFS

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO, 1209

THE YAZOO CITY MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET ALS

THE YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET ALS

THE HOLLY BLUFF LINE CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET ALS DEFENDANTS

AFFIDAVIT OF HARLEY F. GARRETT

FILED BY THE DEFENDANTS

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

COUNTY OF SUNFLOWER

Personally appeared before me, the undersigned authority

in and for the County and State aforesaid, Harley F. Garrett,

who first being duly sworn deposes and says:

My name is Harley F. Garrett. 1 am professor of Education

at the University of Mississippi and in charge of counselor

education program at the University. I was born in Great Bend,

Kansas in 1905. My education began in the rural school of Ford

County, Kansas and continued in the junior and senior high

schools of Dodge City, Kansas, where I graduated in 1924, I

obtained my Bachelor of Science degree at Kansas State Teachers

College of Emporia in 1930. I éceived my Masters in Education

from Stanford University in 1934. I received my Doctorate of

Education ta Administration at the University of Colorado in 1948.

I have been a teacher and school administrator for Xx¥exXasIX

20 years. I have been employed as principal of the high school

of Hobbs, New Mexico for 1 year; Assistant Professor of Education

at Kansas State College, Fort Hays, Kansas for 3 years and I have

been at the University of Mississippi since 1949, and as I said

® »

before am presently in charge of the Counselor Education program

at the University. The Counselor Education program is a part

of the graduate school at the University and consists of a sequence

of 30 hours of graduate courses leading to a masters degree in

guidance, I am professor of Education at the University of

Mississippi.

I have examined at length the proposed Order filed in this

matter by the Yazoo City Municipal Separate School District

together with the Affidavit of Harold C. Kelly, Superintendent

of Schools of such district, and the proposed Order filed in this

matter by the Yazoo County Board of Education and the Affidavit

of W. C. Martin, County Superintendent of Education of Yazoo

County, and the proposed Order filed in this matter by the Holly

Bluff Line Consolidated School District and the Affidavit of Joel

Hill, Superintendent of Schools of such district. In making this

affidavit, I have considered the facts as set forth in the

affidavits of such superintendents, but I have not considered

the expressions of opinion given by them in such affidavits.

The Yazoo County School District proposes that grades 5 through 8

be given an achievement test and the Holly Bluff Line School

District proposes that grades 1 through 4 be given an achievement

test. Both of these districts propose that those students scoring

in the top one-fourth be assigned to particular schools, and

students in the lower three-fourths of scores be assigned to the

remaining facilities of the Sistricte, The Yazoo City School

District proposes that grades 1 through 4 be so tested and that

those students scoring in the upper one-half be assigned to

particular schools and the remaining one-half be assigned to

the remaining schools.

In reviewing these proposed plans, the first point which should

be discussed, it seems to me, is this: Is an achievement test

a valid instrument by which to assign students in a school system?

“d=

First let us define achievement test. An achievement test is

a test which has been designed to measure the degree to which a

student has mastered the knowledge or the skills ordinarily found

being taught at a given grade level. It covers all the academic

areas that are usually taught at any grade level and it is so con-

structed that it reflects what is ordinarily taught at that level

in the United States. You may be interested in knowing how a test

is considered to be valid. In order to be valid a thing must have

a criterion. We have come up with three that are ordinarily used

in the validity of an achievement test. Give us an illustration.

If I were to make up a standardized achievement test in fifth grade

arithmetic in the United States, I would go to the textbooks and

pull out all the things that were taught in fifth grade arithmetic

tests. Then I would see that all those things are reflected in my

test. If I could prove that everything that is covered in the tests

is reflected, then I would have one valid criterion that my test is

valid. Next I would ask the opinion of experts, those who write

fifth grade arithmetic texts, for instance, what they think of my

test, If they all said it was good, then I would have that as a

criterion. Then I would take all the grades that the youngsters

made in fifth grade arithmetic in the United States and I would

rank the students on their grades that the teachers gave them in

fifth grade arithmetic. Then I would give them my test and see how

they ranked. Now if they ranked the same on achievement that you

just gave them and on my test I would say then that I had a valid

test because I was measuring the same thing that the teacher is

measuring. Therefore I would have the three ways of arriving at the

validity of the test. All the good tests on the market are

validated this way or in similar ways.

Now what is the standardization process? They are standardized

by giving the test to youngsters all over America at every economic,

geographic locality, big cities, rural, the poor, the rich, and the

various ethnic groups, in proportion to the degree that that

particular section represents in the total population of these

youngsters in the United States. This 1s called an adequate

sampling. This is done scientifically. They are carefully super-

vised by what I am pleased to call the consumers guide for tests,

which is Buros Mental Measurements Year Book, which is an impartial

evaluation of new tests, standardized tests, that are brought

out on the market each year and over the years. They go into

whether or not it was an adequate sampling. In order to get on

the market, just like a Chevrolet car nowadays, it has to be good.

It has to muster the approval of this evaluating group in the

Mental Measurements Year Book. Moving particularly to the

plans proposed by the Yazoo City, Yazoo County and Holly Bluff

districts, I find that the tests proposed to be used are among

the best thus validated. These tests, of course, cover the entire

curriculum of subjects taught at the grade level for which the

standardized test is intended and do not cover just one subject

such as the arithmetic for fifth grade which I previously mentioned.

Now the point at issue 1s whether or not this test is valid

for grouping students. Througout the testing movement, and 1

have been identified with the testing movement since 1924, my

first year in college, and more intimately so during my later

years using them in the public schools and as 1 teach in

counseling education, preparing counselors for the public schools.

The achievement test has always been used for grouping purposes.

The logic is this. You take a group of youngsters, let's say

all the same age, and we don't know that grade level to put them

lp

in or how to distribute them. Give them an achievement test.

This will reveal to what extent he is able, or has been taught

up to now, that is, at what level may he perform academically.

This has nothing to do with his age in many instances. All we

want to know is where does he perform, at what level. All

right, we take him at that level and put him with people who

perform at about that level. This enables him to compete against

youngsters of his demonstrated achievement level and with them he will

win and get the applause of the multitude once in a while, get the

A, and will be able to perform in class and receive the approval

of his peers and once in a while he will not make it, he will have

to take a lesser grade and the other kid will make an A, but he will

succeed enough = so that his personality will not be damaged. Now

if he is thrown in with a heterogenous group in the same building

or in the same room, and there is a cluster of very advanced

achievers at the top and he is among the slow achievers at the

bottom, he will get a steady diet of failure. He will be frust-

rated, his frustration will manifest itself in certain undesirable

personality reactions. We therefore logically conclude that it

is better to put a youngster in with youngsters that he can compete

with more or less on his level. This is not to isolate him in

general in his lifetime or throughout his or the society's life.

It is simply a matter in school work at what level is he operating.

Therefore, put him with pupils who are operating at that level

and then proceed from there, and give him all the help he needs

to progress upward as fast as he can go, and give him extra help

in the way of special education people, reading experts, enriched

curriculum, etc., the various techniques we have nowadays, helping

the youngster progress as fast as he can go. This plan is

advantageous to all students since the teacher is teaching students

who have comparable ranges or performance, Particularly a low

performance, for whatever reason he is a low performer, is

-lo

advantaged in that he is placed with students within his own

range of achievement, By such grouping, the school will be

permitted to develop remedial measures for slower learners and

to enrich the teaching content with additional materials and

suggestions to stimulate and excite the fast learners,

In the present instance, then, it is my opinion that

assigning students as proposed in the plans is valid and desireable.

Give them an achievement test, let those with the higher score be

placed together, so that they can compete with one another, either

Negro or white, and then let the students who have the lower

scores be assembled in the other attendance centers where they

will not be frustrated by having to compete with those who are

accelerated and somewhat advanced in performance. It is my belief

that when these tests are given over a period of years, there will

be considerable fluctuation up and down, both ways. Some students

will go into the superior group the next year and so be identified

with them. Others will fall from the superior group down to the

lower group because of certain personality qualities, lack of

application, or what not. But it will be an incentive for them to

work upward and they will be provided the opportunity to work

upward.

Although we are moving into somewhat of a new area because of

the uniqueness of the situation in the mid-South, it is my opinion

that there would be substantial integration both ways. A consider-

able number of white students will be in the lower achievement

groups and a considerable number of Negroes will be in the top

scoring groups. This will be increasingly true in the successive

years in the future because, as remedial teaching is provided

and the academic environment is improved, the good ones who have

it will simply gravitate towards the top, and this will give them

the opportunity to be so placed. The result will rest entirely

on them. It will not be forced by zoning or arbitrary assignment

low

by pairing. The students will be the ones who will have done

it themselves by their demonstration of performance and achieve-

ment. There will be others of both races, of course, who land

among the slow achievers through faults of their own, i.e.,

lack of motivation, attitudes, unwillingness to apply themselves,

etc., and therefore they are handicapping themselves because they

are not applying themselves up to their level,

There is another element that will affect the application

of these tests: the Head Start Program will be reflected in

the first four grades through the scores that will be made

presently and in the future, Students who come from disadvantaged

homes, because of Head Start are given a ''leg-up" that many

children from advantaged homes do not have and to this extent,

there is an advantage to the disadvantaged. The heard start

that they have gained thereby should show some affect in succeeding

years beyond the fourth grade level.

Moving to the stigma that may be felt to result, the resent-

ment that may be aroused in the child by being forced into an

arbitrarily predetermined school regardless of his achievement

level, it is my opinion that the proposed method removes that

objection. The plan will be carried forward based on the demon-

strated performance of a youngster regardless of color it is

educationally sound and recommended, it is logical and reasonable

to group them so that they can be taught at their level and the

instruments and the processes that wo use in teaching them will

be at their level, By providing a test each year, we will

give the student the incentive to so perform, and in day-to-day

performance he will be competing with those with whom he can win,

from time to time. It is my prediction there will be increasing

integration throughout all the grades in years to come by using

this method.

The psychological aspect is not necessarily my problem but

if the youngster is associated with someone with whom he cannot

Bly Jo

compete successfully, he suffers frustration, and will employ

compensations that are not desireable. Conversely, he tends to

enjoy competition when he can do so successfully, and respects

and admires his peers. It is my firm conviction that this will

be increasingly true among Negroes and whites under the plan

being proposed.

The plans I have reviewed for these districts all propose

to extend assignment by achievement testing to all grades over

a three year period. It is my opinion there are several reasons

in support of this approach. First, to test all of the students

initially would be an impossible administrative burden. Second,

there would be similar difficulty in assigning students following

the results of these tests to their proper facility and providing

proper transportation where transportation is provided. Third, by

gradual application of the assignment by achievement scores,

integration will be accepted more readily. We say this simply

because we have respect for and do not resent those who can

compete with us successfully. This goes for all of us in our

contact with other people.

The youngster will not be left in the place where he lands

through the first achievement test, He can move up next year

when he takes it again. This is democratic. It is the old

tradition of individual initative. Temporary grouping is not

permanent, In the lower achievement levels it will be like

placing a person in a hospital when he is sick where he receives

special care along with the other sick people. He recovers and

again joins the general public. The such child in the present

proposal is simply being placed where he can get well the fastest.

If children grouped in the higher achievement levels fall behind

the others, they will be placed among those who are receiving

remedial education, as a person who becomes ill is placed in a

hospital to secure medical care. In the school of the present

-8-

and the future, the offering is so broad, in order to accommodate

all children, each child can find his place, and progress with

his group. Such grouping is always temporary, the child will

move from group to group constantly in succeeding years by

virtue of his performance on the achievement test. As he progresses

through the twelve grades, eh will find his strength and weaknesses

among the subjects offered and will tend to gravitate towards the

offerings in the curriculum in which he has the most interest

and the aptitude.

There is no socio-economic bias in these tests for the

reason that this problem simply has been neutralized scientifically.

As I commented earlier the standardization process has taken

into consideration children all over America at every economic

level and in every locality in finding the norm for the tests.

These tests ascertain the then achievement level of the child

as compared to the norms established and his demonstrated progress

at the time of the test. The composite score derived from these

tests is the fairest way to ascertain such achievement level,

As a result of the grouping proposed here, the pupils in the

lower achievement group will have a better opinion of themselves

as they are competing with individuals of comparable abilities.

This prevents them from suffering fromlack of motivation, poor

attitudes, unwillingness to apply themselves, etc. The higher

groups are prevented from having an inflated opinion of abilities

as they are also competing with students of comparable achievement

levels. The youngsters not only have bettern opinions of

themselves, but of each other, because we tend to admire and

respect and get along well with people of comparable performance.

Because we can compete with them, winning sometimes and losing

sometimes, we not only have a fine time in the association with

them, but also achieve our greatest development.

Grouping according to the student, capacities of schools is

desireable as the original step and may be refined as the tests

WE» I

continues. Such grouping has permanent advantages in that it

prevents undesireable comparisions by students in different

achievement levels; it also permits the school staffs to con-

centrate their interests upon teaching students of comparable

levels. It enables the school by in-service training to teach

the staff proper methods of training such groups and permits the

assignment of such teachers with such abilities and experience.

These districts propose that the achievement tests be

administered and scored by capable, impartial outside testing

agencies. In my opinion, this is necessary and proper in order

that there be no variations in conducting and scoring the tests

and that confidence in the results be instilled in the public.

In conclusion, I find, based upon my training and experience

in the field of education, that grouping by performance levels

as proposed in the plans of these districts, by the use of the

achievement test scores mentioned in the plans or other similar

nationally recognized tests, will be helpful and desireable in

the education of school children and will produce a more beneficial

form of integration of the races by educational considerations than

indiscriminant mixing would produce, and would improve education

at all performance levels within the schools.

Harley F. Garrett

i /

t/

SWORN to and subscribed before me this the XO Day of

August, 1969.

Lor ph

Notary Public ¢

My Commission Expires:

Nay 29, (722,

10

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby cetify that copies of the foregoing instrument

were served on the plaintiffs on this 20th day of August, 1969,

by mailing copies of same, postage prepaid. to their counsel

of record at the last known address as follows:

Melvyn R. Leventhal

Reuben V. Anderson

Fred 1... Banks, Jr.

John A, Nichols

538-1/2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Jack Greenberg

Jonathan Shapiro

Norman Chachkin

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

I further certify that I have also mailed a copy of

said instrument to the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare of the United States ire588d as follows:

Mr. J. J. Jordan, Regional Director

United States Office of Education

Room 404

30 Seventh Street, NE,

Atlanta, Georgia 30323

er

0.

y au

Of Counsel Vi