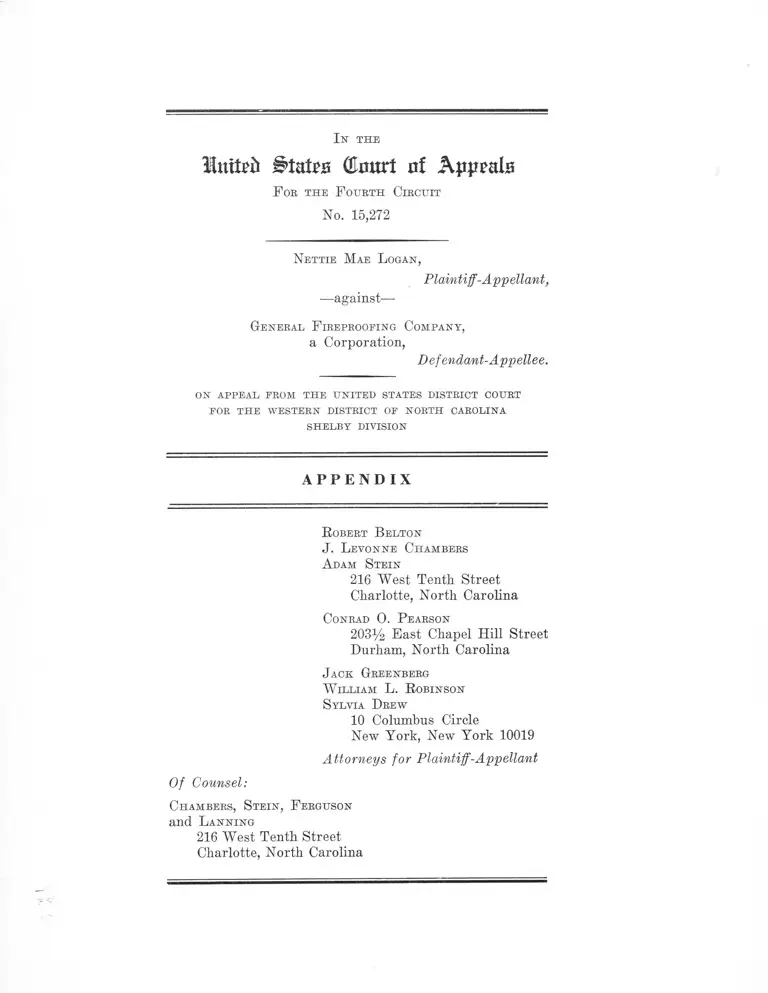

Logan v. The General Fireproofing Company Appendix

Public Court Documents

March 18, 1969 - November 26, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Logan v. The General Fireproofing Company Appendix, 1969. e0fd508b-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b8db427b-18e0-45df-b8a8-393d45e48304/logan-v-the-general-fireproofing-company-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1st the

lulled States (Emtrt of Appeals

F oe th e F o u rth C ircuit

No. 15,272

N ettie M ae L ogan,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

—against—

G eneral F ireproofing C o m pan y ,

a Corporation,

Defendant-Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SHELBY DIVISION

A P P E N D I X

R obert B elton

J . L evonne C hambers

A dam S tein

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

C onrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J ack G reenberg

W illiam L. R obinson

S ylvia D rew

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

Of Counsel:

C h am bers , S t e in , F erguson

and L a n n in g

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

I N D E X

Page

Complaint - Filed March 18, 1969 ................... 1

Defendant's Motion to Dismiss - Filed April 10,1969 7

Defendant1s Motion for More Definite Statement -

Filed April 10, 1969 ............................... 11

Memorandum of Decision - Filed September 8, 1969 . . 14

Plaintiff’s Statement Pursuant to Order of September

8, 1969 - Filed September 24, 1969 . . . . . . . . 24

Answer - Filed October 14, 1969 . . . . . . . . . . 28

Plaintiff's Interrogatories to Defendant - Filed

October 23, 1969 .................... 31

Defendant's Answers and Objections to Interrogatories-

Filed November 26, 1969 ........................... 39

Order on Objections to interrogatories- Filed January

19, 1970 .......... 53

Defendant's Further Answers to Interrogatories- Filed

April 1, 1970 60

Defendant's Motion for Summary Judgment - Filed

April 1, 1970 . .................................. . 81

Affidavit of Elizabeth Harris - Filed April 1, 1970 83

Affidavit of Fred Powers - Filed April 1, 1970 . . . 87

Affidavit of Thomas Edmunson - Filed April 1, 1970 93

Affidavit of Nettie Mae Logan - Filed April 16, 1970 100

Memorandum Decision dismissing the action - Filed

September 10, 1970 .................... 105

Plaintiff's Notice of Appeal - Filed September 24, 1970 117

Deposition of Nettie Mae Logan taken October 9,1969 120

Attachment to Defendant's Answer to Interrogatories-

Filed November 26, 1969 . ............. 179

[Filed March 18,1969]

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

"FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SHELBY DIVISION

NETTIE MAE LOGAN,

Plaintiff,

v.

GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY,

a corporation.

Defendant.

C O M P L A I N T

I

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§1343 (4); 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f) and 28 U.S.C. §§2201 and 2202.

This is a suit in equity authorized and instituted pursuant to

Title VII of the Act of Congress known as "The Civil Rights Act

of 1964", 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq. The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked to secure protection of and to redress depriva

tion of rights secured by (a) 42 U.S.C. §S 2000e et seq., pro

viding for injunctive and other relief against racial discrimina

tion in employment and (b) 42 U.S.C. §1981, providing for the

equal rights of all persons in every state and territory within

the jurisdiction of the United States.

II

Plaintiff brings this action on her own behalf and on behalf

of other persons similarly situated pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2) of

‘)

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION

) NO. 3050

)

)

)

>

)

- I "

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The class which plaintiff

represents is composed of Negro persons who are employed and might

be employed or who might seek employment by General Fireproofing

Company at its manufacturing facilities located in Forest City,

North Carolina, who have been and continue to be or might be ad

versely affected by the practices complained of herein. There are

common questions of law and fact affecting the rights of members

of their class who are and continue to be limited, classified, dis

criminated against and refused employment in which deprive artd

tend-to deprive them of equal ''■nploynent'opportunities and other

wise adversely affect their status as employees because of. race

and color. These persons are so numerous that joinder of all mem

bers is impracticable. A common relief is sought. The interests of

said class are adequately represented by plaintiff. Defendant has

acted or refused to act on grounds generally applicable to the

class.

III

This is a proceeding for a declaratory judgment as to plain

tiff’s rights and for an injunction restraining defendant from

maintaining a policy, practice, custom or usage of: (a) discriminat

ing against plaintiff and other Negro persons in this class because

of race or color with respect to hiring, compensation, terms, con

ditions and privileges of employment;and (b) limiting, segregating

and classifying employees of defendant General Fireproofing Company

in ways which-deprive plaintiff and other Negro persons in this

class of equal employment and otherwise adversely affect their

status as employees or prospective employees because of race and

color.

IV

Plaintiff Nettie Mae Logan is a Negro citizen of the United

States and a resident of Bostic, North Carolina. Plaintiff ha3

sought employment with defendant General Fireproofing Company.

- 2 -

V

Defendant General Fireproofing Company is a corporation doing

business in the State of North Carolina and the City of Forest

City. The Company operates and maintains a facility which pro

duces chairs of fabric, leather and aluminum.' .The Forest City fa

cility operated by defendant is an employer within the meaning of

42 O.S.C. §2000e-(b) in that the Company is engaged in an industry

affecting commerce and employs at least 25 persons.

VI.

On December 27, 1965, the plaintiff filed an application with

the defendant for employment. She was informed that there were

no openings for employment. Two days later, the defendant placed

an ad in the newspaper soliciting trainees for employment. The

plaintiff returned to renew her application thereafter and returned

on several occasions through June of 1966. She was never hired

by the defendant, although the defendant hired white workers

during the period her application was pending.

At all times mentioned herein, the defendant employed no

Necrroes as professionals, technicians, sales workers, office and

clerical workers or craftsmen. As of June 1967, the defendant

employed over 440 employees, only 30 of whom, were Negroes and

only 3 of the 30 Negroes employed were women. At that time,

Negroes worked only in the lower paying jobs. In addition, Negroes

doinq the same work as white employees were paid lower wages. The

defendant did not post an Equal Employment Opportunity poster as

required by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

The failure to hire plaintiff and other Negro applicants, the

limitation of the few Neqroes hired into lower paying jobs, the

failure to pay Negroes the same wages for the same work as white

employees, the failure to promote Negroes on the same basis as whites,

and the . failure to post the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion poster are all part of the defendant's long-established

policy and practice, the design, intent and purpose of which is to

contirue and preserve, and which has the effect of continuing and

- 3 -

preserving, the defendant's policy, practices, customs and usages

of limiting the employment and promotional opportunities of Negro

employees because of race or color in violation of Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 42 U. S. C. §1981.

VII

The practices herein alleged are continuing up to the present

time and the defendant has not made any efforts or attempts to cor

rect, modify or disavow the policies and practices complained of

herein.

VIII

The plaintiff has at all times been qualified for employment

with the defendant.

IX

On June 27, 1966, within ainety (90) days of the last re

fusal of employment which had continued from December 27, 1965

until June 1966, plaintiff filed a written charge, under oath, with

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission alleging denial by de

fendant of her rights under Title VII of the "Civil Rights Act of

1964", 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq. On June 27, 1967, the Commission

found reasonable cause to believe that the defendant had committed

a violation of the Act.

On or about February 17, 1969, plaintiff was advised that con

ciliation efforts had failed to accomplish voluntary compliance

with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and that she was en

titled to institute a civil action in the appropriate federal dis

trict court within thirty (30) days of receipt of said letter.

X

Plaintiff and the class she represents have no plain, adequate,

or complete remedy at law to redress the wrongs alleged herein and

this suit for an injunction is her only means of securing adequate

relief. Plaintiff and the class she represents are now suffering

and will continue to suffer irreparable injuries from the defendant's

- 4 -

WHEREFORE, plaintiff respectfully prays the Court to advance

this case on the docket, order a speedy hearing at the earliest

practicable date, cause this case to be in every way expedited and

upon such hearing to:

1. Grant plaintiff and the class she represents a per

manent injunction, enjoining the defendant General Fireproofing

Company, his agents, successors, employees, attorneys and those

acting in concert with them and at their direction from continuing

tO!

(a) discriminate against Negro applicants

for employment on the grounds of race

or color;

(b) limit Negroes to lower paying jobs;

(c) pay Negroes lower wages than whites

for the same work; and

(d) fail to post Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission posters.

2. Grant the plaintiff and the class she represents a

declaratory judgment that the policies, practices, customs and

usages complained of herein are violative of rights protected by

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 42 U.S.C. S19S1, pro

viding for equal rights of citizens and all persons within the

jurisdiction of the United States.

3. Grant plaintiff the job she was wrongfully denied

and all back pay to which she is entitled.

Plaintiff further prays that she be awarded costs, reasonable

attorneys' fees and that the Court grant such further, additional

or alternative relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable

and just.

Respectfully submitted,

Con ra d o . p e a r£6m'

203 1/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON S BANNING

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

policies, practices, customs and usages as set forth herein.

- 5 -

JACK GREENBERG

ROBERT BELTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiff

6 -

[Filed April 10,1969)

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SHELBY DIVISION

NETTIE MAE LOGAN, ]

PLAINTIFF,

1v> CIVIL ACTION NO. 3050

GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY, ]

a corporation,

DEFENDANT. ]

_________________ 1

MOTION TO DISMISS

The Defendant, the GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY moves

the court as follows:

1. To dismiss the action and complaint herein because the

complaint fails to state a claim against defendant upon

"Which relief can be granted.

2 . To dismiss the complaint for the reason that the

plaintiff does not sufficiently allege therein that

she filed a charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission within ninety days after the alleged unlawful

emplpyment practice occurred, as required by Title 42,

§2000 e-5(d), U.S.C.

3. To dismiss the complaint because the plaintiff has not

alleged that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

furnished the defendant with a copy of any charge filed

with such Commission within 30 days of the filing, as required

by Title 42, §2000 e-5(a), U.S.C.

4. To dismiss the complaint because it does not allege that

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in fact endeavored

to eliminate any alleged unlawful employment practice by

informal methods, as required by Title 42, §2000 e-5(a), U.S.C.

To dismiss the complaint because the complaint does not

^show or allege that any charge filed by the plaintiff with

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission contained

any of the accusations presented in the complaint,

or that the complaint is limited to accusations

previously presented to the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission in any charge.

To dismiss the complaint, insofar as it purports to be

brought in behalf of persons other than the individual

pla'intiff NETTIE MAE LOGAN, because it is not alleged

that any other persons sought to be included as plaintiffs

have filed charges before the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission.

To dismiss the complaint insofar as it seeks broadly

to enjoin the defendant from limiting Negroes to lower

paying jobs and from paying Negroes lower wages than

whites for the same work, because it does not appear

from the complaint that the circumstances surrounding the

different jobs of various Negro employees of defendant

are the same.

To dismiss the complaint insofar as it seeks any relief

in behalf of Negro persons who might be employed by or

might seek employment by defendant, because it is not

shown that the circumstances surrounding such applicants

will be the same in each case, and because the identity

, %

of such persons is a matter of speculation and conjecture.

9. To dismiss the complaint as to any and all plaintiffs other

than Nettie Mae Logan because the relevant statutes

which are contained in Title 42, §2000 e-5 and 2000 e-6 U.S.C.,do

not contemplate or provide that an individual person aggrieved

shall maintain any suit other than a suit to remedy the

specific unlawful employment practice allegedly committed

against that individual, and said statutes contemplate that

suits to enjoin any alleged pattern or practice of dis

crimination shall be maintained by the Attorney General of the

United States and by him only.

GLENN L. GREENE, JR. ' *

Suite 602, 1201 Brickell Avenue

Miami, Florida 33131

Forest City, North Carolina

Attorneys for Defendant

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that true and correct copies of the

foregoing Motion to Dismiss were this day served upon the

plaintiff herein by depositing the same in the United States

mails, first class postage prepaid, and addressed to each of

the following:

CONRAD 0: PEARSON, ESQ.

203-1/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON & PANNING

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG, ESQ.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

ROBERT BELTON, ESQ.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

they being the attorneys of record for plaintiff.

Dated this April 10, 1969.

ATTORNEY

[Filed April 10,1969]

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SHELBY DIVISION

1

;j

] CIVIL ACTION NO. 3050

]

]

J

MOTION FOR MORE DEFINITE STATEMENT

The defendant, the GENERAL FIREPROOFING CO., pursuant

to Rule 12(e), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, moves

the court for an order requiring the plaintiff Nettie Mae

Logan, before the defendant is required to interpose its

responsive pleadings to file a more definite statement of

certain matters alleged in the complaint, and states that the

complaint is so vague and ambiguous that the defendant cannot

reasonably be required to frame a responsive pleading at this

time.

The defects complained of and the details desired are as

follows:

1. The complaint is defective in paragraphs VI and IX in

that it does not show precisely when and how the plaintiff

last applied for or renewed her application for employment

with defendant or how and when the defendant's last refusal

to hire occurred. As the defendant's supporting memorandum

will show, these matters are jurisdictional, and the plaintiff

should therefore be required to state precise facts showing that

she filed a charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission within ninety days after a refusal to hire occurring

NETTIE MAE LOGAN,

PLAINTIFF,

V.

GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY,

a corporation,

DEFENDANT.

on a specific date. If the plaintiff is relying on the

alleged refusal to hire of December 27, 1965, as constituting

a continuing unlawful act, the defendant will wish to

frame motions accordingly.

2. The complaint is defective in paragraph IX in that it

fails to allege the details surrounding the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission's advice to the plaintiff that

conciliation efforts had failed. This matter is jurisdictional

as defendant's supporting memorandum will show, and plaintiff

should therefore be required to state precisely when her

letter from the Commission was addressed, when it was received

by her, and substantially what statements were contained

in said letter.

3. The complaint is defective in paragraph IX in that it

does not show what specific accusations the plaintiff made

against the defendant in her charge filed with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission. It is the defendant's

position that the complaint herein cannot be broader than

plaintiff's said charge, and plaintiff should be required

to allege the details of said charge so that defendant can

address appropriate motions to the complaint.

GL

Suite 602, 1201 Brickell Avenue

Miami, Florida 33131

j/T TOLIVER DAVIS, ESQ.

4O8 Florence Street

Forest City, North Carolina

J/. TOLIVER DAVIS,

4O8 Florence Stre

, ! 6 ! U ^ \ y q o ‘j v

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANT

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that true and correct copies of the

foregoing Motion for More Definite Statement were this day

served upon the plaintiff herein by depositing the same in the

United States mails, first class postage prepaid, and

addressed to each of the following:

CONRAD 0. PEARSON, ESQ.

203-1/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON & LANNING

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG, ESQ.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

ROBERT BELTON, ESQ.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

they being the attorneys of record for plaintiff.

Dated this April 10, 1969.

£

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNIT:

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH

SHELBY DIVISION

NETTIE MAE LOGAN,

Plaintiff )

vs CIVIL ACTION NO. 3050

GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY,

a corporation.

)

< Defendant

)

MEMORANDUM OF DECISION

THIS is a civil action brought by the plaintiff,

Nettie Mae Logan, against the defendant. General Fireproof

ing Company, alleging that she was denied employment on

account of her race and sex. Her complaint filed under

Section 706(e) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C.A., Section 2000e-5(e), alleges that she applied

for work with the defendant company on December 27, 1965,

and was advised that there were no jobs available, and that

within a few days thereafter the defendant published a news

paper notice seeking trainees for employment. She further

alleges that she continued to seek employment with the

defendant until June, 1966, without success, and that white

individuals were employed after her application was denied.

On June 27, 1966, she filed a charge with the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission contending that she had not been

hired because of her race. On June 27, 1967, the Commission

found reasonable cause to believe that the defendant had

committed a violation of the Act, and on February 17, 1969,

the plaintiff was advised that conciliatory efforts had failed

- 2 -

to accomplish voluntary compliance with Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, and that she was entitled to

institute a civil action in the appropriate federal District

Court within thirty days of receipt of said letter. This

action was filed on March 13, 1969, and plaintiff seeks to

represent not only herself but also all future applicants

for employment, all present employees, and all future em

ployees of General Fireproofing Company. She alleges that

the defendant is now engaged in the following discriminatory

practices;

1. Discriminating against Negro applicants

for employment on the grounds of race or color.

2. Limiting Negroes to lower paying jobs.

3. Paying Negroes lower wages than whites

for the same work, and

4. Failing to post Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission posters in its plant.

She prays that she and the class she represents be

granted a permanent injunction enjoining the defendant from

continuing such discriminatory policies and that a declaratory

judgment be entered adjudging that said policies, practices,

customs and usages complained of here are violative of the

rights of the plaintiff and her class protected by Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and 42 U.S.C.A., § 1981. She

further contends that the defendant should be required to give

/•

her the job she applied for and pay all back wages to which she

is entitled, and that she be awarded costs and attorneys fees.

The defendant filed a Motion to Dismiss and in the

alternate, a Motion for More Definite Statement. These

motions were heard by the Court on July 7, 1969, and the

1 5 "

; ?

-3-

attorneys have filed their briefs. After serious con

sideration of the arguments and the briefs, the Court

enters this Memorandum of Decision and Order,

The Motion to Dismiss is based upon the general alle

gation that the complaint fails to state a claim against the

defendant upon which relief can be granted. The motion raises

several specific reasons why the action should be dismissed

and the Court will list these reasons and pass upon them

separately.

The first specific reason given is that the plaintiff

does not sufficiently allege in the complaint that she filed

the charge with the JSgual Employment Opportunity Commission

within ninety (90) days after the alleged unlawful employment

practice occurred, as required by Title 42 U.S.C.A., 2000e-5 (e).

This section of the Act requires that it must be filed with

the Commission within ninety (90) days of the occurrence of

the alleged unlawful employment practice. Plaintiff alleges

that she filed written application for employment with the

defendant on December.27, 1965, and filed her charge with the

Commission on June 27, 1966, which is more than ninety (90)

days. However, she alleges that she returned to renew her

application on several occasions and continued to do so through

June, 1966, without success, but gives no specific date. This

allegation, though it be indefinite, is sufficient to allege

that the charge was filed within ninety (90) days from the

alleged unlawful employment practice. The Court therefore

holds that this allegation is sufficient to weather the storm

of the Motion to Dismiss but the Motion to Make More Definite

and Certain will be allowed and plaintiff will be required

Vt

-4

to allege specifically the last date she applied for work 1

prior to the filing of her charge with the Commission.

The next specific reason set forth in the Motion to

Dismiss is that plaintiff has not alleged the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission furnished the defendant with a

copy of any charge filed with the Commission within thirty

(30) days of the filing, as required by 42 U.S.C.A., 2000e-

5(a). This section of the Act provides that, "The Commission

shall furnish such employer . . . with a copy of such charge

and shall, . . . " but this Court can find no requirement in

the statute that it must be done within thirty (30) days.

Fair and just procedure would require that a copy of the

charge be served on the defendant within thirty (30) days

or less, but there seems to be no statutory requirement of

such timely service. The defendant relies upon the case of

International Brotherhood of Electric Workers, v. U.S. Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission, 283 F. Supp., 769 (W. D.

Pa. - 1967), which held that the Commission was without

authority to proceed to investigate a charge if the charge

had not been served upon the defendant. However, this decision

was reversed by the Third Circuit Court. See opinion in

398 F. 2d 248, wherein the court said, "It must be borne in

mind that the prime duty of the EEOC is to investigate and

conciliate. We perceive no time limitation imposed by the

Equal Employment Opportunities Act or the regulations of the

EEOC by which a charge must be served and proceeded with by

the Commission." This Court is of the opinion, and there

fore holds, that the service of the charge upon the defendant

is not a jurisdictional prerequisite to the institution of an

- / 7 -

' r r . • f —

1

- 5 -

action under the Act.

The next specific reason advanced by the defendant

for dismissal is that the complaint does not allege that

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in fact endeavored

to eliminate any alleged unlawful employment practice by in

formal methods as required by 42 U.S.C.A, 2000e-5 (a). The

Act specifically requires the Commission to attempt concili

ation after investigation and determination that there is

reasonable cause to believe that the charge is true. The

pertinent part of Section 2000e-5(a) provides that. “The

Commission shall endeavor to eliminate any such alleged un

lawful. employment practice by informal methods of conference,

conciliation and persuasion." This is a mandate from the

Congress and the Commission is legally bound to make the effort.

The Commission's rules now require that the effort be made.

However, the Fourth Circuit Court specifically held in the

case of Johnson v. Seaboard Airline Railroad Company, 405

F. 2d 645 (4th Cir. 1968); certiorari denied, _____U.S._____;

_______S. Ct. ______ (1969) that actual attempts to conciliate

by the Commission are not jurisdictional prerequisites to the

institution of suit. The complaint alleges that the plaintiff

was advised by the Commission on February 17, 1969, that con

ciliation efforts had failed to accomplish voluntary compliance

and that she was entitled to institute civil action within

thirty (30) days. This Court is of the opinion that that

allegation is sufficient to allege a conciliation effort even

if the defendant's contentions were correct that such allega

tion was a jurisdictional prerequisite.

1%

T ’ ?

- 6 -

The defendant next contends that the complaint does

not show any charge filed with the Commission contained any

of the accusations presented in the complaint or that the

complaint is limited to the accusations previously presented

to the Commission in the original charge. It contends that

the Court is limited to a consideration of the allegation

contained in the original charge. The original charge filed

with the Commission by the plaintiff contains only the con

tention that she was denied employment because of her race.

Defendant relies upon Cox v. U. S. Gypsum Co., 284 F. Supp. 74

(NjD. Ind. 1968)# and Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation,

393 F. 2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968). In Oatis, the Fifth Circuit

held that the plaintiff in a class action can raise only issues

to which he was aggrieved and which he had raised in his charge

to the commission. The defendant contends this to mean that

the allegations set forth in the complaint must be identical

with those contained in the original charge. Apparently, the

Fifth Circuit did not intend such a strict interpretation of

Oatis, because in a decision a few months later, it declared

in Jenkins v. United Gas Corporation, 400 F. 2d 28;

"Although there are restrictions both in time

and pre-conditions for court action this does not

minimize the role of ostensibly private litigation

in effectuating the congressional policies. To

the contrary, this magnifies its importance while

at the same time utilizing the powerful catalyst

of conciliation through EEOC. The suit is therefore

more than a private claim by the employee seeking

the particular job which is at the bottom of the

charge of unlawful discrimination filed with EEOC.

When conciliation has failed - either outright or

by reason of the expiration of the statutory time

table - that individual, often obscure, takes on

the mantel of the.sovereign. Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, 1968, 390 U. S. 400, 88 S. Ct. 964,

19 L. Ed. 2d 1263; Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach, supra.

And the charge itself is something more than the

•ingle claim that a particular job has been denied

-7-

him. Rather it is necessarily a dual one: (1)

a specific job, promotion, etc. has actually been

denied, and (2) this was due to Title VII forbidden

discrimination."

The charge filed with the Commission was apparently

prepared by the plaintiff, who as a layman, would have only

a general idea as to the contents of the statute, and to limit

the court and the Commission to the consideration of the charge

itself would result in multiplicity of litigation and a burden

upon the already overcrowded docket in the federal courts.

There is nothing to indicate that Congress intended such a

restrictive interpretation as requested by the defendant.

Defendant next contends that the complaint must be

dismissed because it is not alleged that the other persons

sought to be included as plaintiffs have filed charges before

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. This issue seems

to be well settled. In Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation.

suara. the Court said:

“Additionally, it is not necessary that members

of the class bring a charge with the EEOC as a

prerequisite to joining as co-plaintiffs in the

litigation. It is sufficient that they are in a

class and assert the same or some of the issues."

The last three contentions contained in defendant's

Motion to Dismiss deal generally with the question of class

action and have been partially briefed together and will now

be considered together in this decision. In substance, the

defendant says that the complaint does not show whether those

purported to constitute the class are in the same situation

as the plaintiff, and that since plaintiff alleges a denial

of employment only, she cannot join members of a class alleging

Other and different unlawful practices. The defendant cites and

relies upon Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation, supra, which

i

-8-

requires that there roust be questions of law and fact common

to the plaintiff and the purported class, and Jenkins v. United

Gas Corporation, 261 F. Supp., 762, which held that an action

wherein the plaintiff alleged he had been discriminated against

in promotion could not be maintained as a class action and in

clude all Negroes who have suffered, or might suffer, a wide

variety of discriminations.

The Court does not read Oatis as being as restrictive

as the defendant contends it to be. Regardless of the meaning

of Oatis, the same Court a few months later seemed to relax

the restrictions. The Fifth Circuit in the case of Jenkins

v. United Gas Corporation, 400 F. 2d, 28, not only broadened

its rule relative to class actions, but specifically overruled

the district court's holding that no common question of fact

exists as to all Negro employees of the defendant since different

circumstances surrounded their different jobs and qualifications

in the structure of the corporation. The court further held

that although the plaintiff, who alleged he had been denied

a promotion, was subsequently offered and accepted such promo

tion, that the case was not moot and the plaintiff had standing

to represent all other Negro employees of the company against

plant-wide systematic, discriminatory employment practices.

It appears Congress intended to permit class actions

under Title VII of the Act and that such actions should be

limited to that range of issues reasonably related to and

growing out of the original charge of discrimination.

. i

-9-

This Court is of the opinion that the plaintiff has

standing to raise the issues in the complaint in a class

action and the court has jurisdiction to hear them.

By way of summary, it is clear that the courts have

properlythus far agreed that before an action is/instituted under

Title VII, a plaintiff must have filed a charge of an unlawful

employment practice with the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission within ninety (90) days of the alleged violation and

must file said action in the proper United States District

Court within thirty (30) days of receiving notice of the

Commission's failure to achieve voluntary conciliation. Dent

v. Rlv. Co.. 406 F. 2d 399 (5th Cir. 1969)? Johnson v. Railroad,

405 F. 2d 645 (4th Cir. 1968)? Choate v. Caterpillar Company,

402 F. 2d 357 (7th Cir. 1968). These requirements are juris

dictional and must be specifically alleged in the complaint.

The complaint in the case at bar contains such allegations in

sufficient form to defeat the Motion to Dismiss.

IT IS, THEREFORE, ORDERED that defendant's Motion to

Dismiss be, and the same is hereby denied.

Certain inconsistencies appear in plaintiff's complaint

and in the brief filed by the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission as Amicus Curiae relative to the date of the appli

cation for employment, and the complaint is somewhat indefinite

as to the final date of application for employment and the

details relative to the refusal of employment. The defendant

i3 entitled to have these matters alleged specifically and the

inconsistencies removed before filing answer. The Court, there

fore, ORDERS the plaintiff to file a statement or an amendment

to the complaint within twenty (20) days from the receipt of

this Memorandum of Decision and Order, setting forth the details

-10-

relative to her application for employment with the defendant

and the defendant's refusal to employ her,

Except as stated above, the defendant's Motion for

More Definite Statement is hereby denied.

This the 27th day of August, 1969.

Chief Judge, Unitedsfates District Court

S

- 2 3

IN THE

u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t

FOR THE-

N2ST2SH DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SHELBY DI‘V131 OR

NETTIE MAS LOGAN,

v.

P l a i n t i f f /

GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY,

a -corporation,.

D efen d an t.

CIVIL ACTIO*

NO. 3050

S T A T E M E. 1? T

P l a i n t i f f / by h er u n d ers ig n ed c o u n s e l, r e s p e c t f u l l y nr.Roo

th e fo l lo w in g s ta tem en t p u rsu an t to th e Memorandum end O rder cf

th e C ou rt o f Septem ber C, 3.969:

1 « f.lV 1 c->i i .r s i s an a e t i on brou.ghfc by p l a i n t i f f on he r own b e -

h a l f fxnd on b aha I f o f o th e r s s i m il c r ly c i t u a t od v.ndo r T i t l e V II

o f th 13 Ci.,v i 1 pig h ts A ct o f 1964 COth in g r e l i c f £:.rcn a l le g e d

r u e ia ■?-Tly d i s c 1'3.min at o r y eruplo v e ;rmt p ra c fclC33.

2 0 On 3op tomba r 8 / 19 69/ t ho iC ourt o u te r Gd a Momorandun

o f Da /*0iof,,cn c VCr r u l in g dG Hndan. t 1 3 r o hi. one t o d i • t y.*»•■1-A. Co and c o r a.

no?1>Z% •»c o H .rJ.to <T» . / ;■»*, «-a- b» '.levent.

3. The Ccurii in its Dacia: ion and O r d e r cf S e p t o m b

1539 o r d e r e d "the p l a i n t i £ £ to file a etatome: .1 L or an a:

■i . A - ̂ ^ 3 wO Ih J Uvi.w.1 ,eiiit *./ithin t (10) day s freei t!lie

D h” ' si-^n O rd e r , s o t t in v f o r t h th e d o t a l 3a red s t i v e t o 5.

i

explication for employment v/ith the defendant ark 1 th.

refusal to employ her."

*. The above provision of the Order v?as occasioned by

"certain•inconsistencies [which] appear in plaintiff’s complaint

red in the brief filed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Cova-

niaaicn ari Amicus Curiae relative to the date of the application

jymont..."

5. Plaintiff’s memory has bacor.va som-sYJhat cloudy as to

enact dates as to events which occurred in 195G. She, thus,

originally adopted the dates cat forth in the Commission’s

Decision. Counsel for plaintiff has been supplied with the at

tached "Memorandum for the File" by the EBOC relative to tha

and i. tl ’tip

-3ion a

for CTTiplo;

5. :

da tos in quostion. Pled,

the Memorandurn as cci.rrec

cost was made in eith

She is certain that she '

of.’ June 1966 and thi,nko ■

6. It is submi’?=»i a**, \.& S*̂

veal Whoi-har1 any Gisputs

bo fewsen the parties and,

to this proc:ooding„

Respectfully submitted,

COhRAD O. PEARSOh

203 1/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON £

LAMMING

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG

ROBERT BELTON

10 Columbus Circle

Now York, Urv York

Attorneys for Plaintiff

M b '

13 OP MOMTH CP.-riOLXiTA

kU^IIEPFGRD COUIJTS

V E R X P 2 C A T 2 O N

HETXXE MJ\E LOXIM, being first duly sworn, says that oha

tho plaintiff in this action? that «ha has road t

Stator.iant end knows fcho contents thereof? that th

of her cvn- knowledge eucspt as to those matters a

upon information end belief, and as to these, ska fcoliovoc then

to bo trua.

f o r e g o i n g

'.> ̂ fnx-'hts **»r

'. t cl v>̂ 3 3 if O AT*

2U''r'2 ;\lVi

Subscribed and sworn to fcaforo me this • day of

Septonber, 2969.

My Cotrsaission Empires»

5 6

Cj~'' r T ^ P ' C C ' ' C •* J , * . - v. ,U#

1 ’a o t a d e r e h e r e b y e t a L i f i o n tiat ho he” nerved a Dpi

of th e fo rec;eJ:<; S c a t'- ''O h n.--v./ *"* * - .) *•• Uw..,vi*C U|-'Oi

a c p o r I j! CP''! > ’’ c!

1 co u n se l fo r th e dafondanh

-j in who United States Hail, peace

» •! p ... /; ~......... ..... i ,

T h i ’

Gl-cm h. Grcone, Jr „,

Sui.to 002

120•1 hrichel1 Avenuemi t Fierida 33131

and

J. Toliver D.avia, Esq

103 Florence StreetForost City, North Ca

ffz a *** loco/ V ©

\i»

A t t o r n e y fo r P l S T n i O l T

< 7 7

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COUR

FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SHELBY DIVISION

f i l e d

OCT 14 1969

NETTIE MAE LOGAN,

PLAINTIFF

* ;

V3 e

)

) Civil Action File No. 3050

GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY, )

A CORPORATION, )

DEFENDANT )

)

ANSWER

COMES NOW, the Defendant, GENERAL FIREFRCCFING COMPANY, a

Corporation, pursuant to Rules 8, 9 and 12 of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, by and thru its undersigned counsel, and

answers Plaintiff's Complaint as follows:

1. Defendant denies Paragraphs I, II, VI, VII, VIII, IX

and X and the second sentence of Paragraph V of the Complaint.

2. Defendant admits the second sentence of Paragraph IV

and the first sentence of Paragraph V of the Complaint.

3 . Defendant is without knowledge as to the allegations

contained in the first sentence of Paragraph IV of the Complaint.

U, Defendant admits to the nature of the proceedings as

described in Paragraph III of the Complaint but denies the

existence of any policy, procedure or conduct or the exercise of

same as described in Paragraph III of the Complaint.

5. Plaintiff did not file a written charge, under oath,

with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission alleging denial

by Defendant of her rights, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, within ninety (90) days of Defendant's failure or refusal

to hire her, and this Court is therefore without jurisdiction of

this cause,

WHEREFORE, Defendant prays that the Complaint be dismissed,

that all relief sought therein be denied, that it recover cf the

Defendant its costs herein expended, and that the Court award

Defendant such other relief as may be proper.

1201 Brickell Avenue

Miami, Florida 33131

--

'Forest City, North Carolina

Attorneys for Defendant

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that a true and correct copy of the

foregoing Answer was this day served on each of the following

persons, at the addresses set forth below, by depositing same

in the United States mails, Air Mail postage prepaid:

CONRAD 0. PEARSON, Esq.

203 1/3 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON and LANNINC

216 W. 10th Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG, Esq.

ROBERT BOLTON, Esq.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

RUSSELL SPECTER, Ass't. Gen. Counsel

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

1800 G Street, NW

Washington, D. C.

Dated at Miami, Florida,

this 14th day of October, 1969.

Attorney for Defendant

[Filed October 23,1969]

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

NETTIE MAE LOGAN, : .

Plaintiff, :

- vs - : CIVIL ACTION

NO. 3050

GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY, :

a corporation.

Defendant.

INTERROGATORIES

TO: TOLIVER DAVIS

108 Florence Street

Forest City, North Carolina

Attorney for Defendant.

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that plaintiffs request, pursuant

to Rule 33 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, that

defendant General Fireproofing Company answer under oath

within 15 days after service hereof, the following written

interrogatories, and identify separately and in a manner

suitable for use as a description in a subpoena, all sources

of information (whether documentary, human or otherwise) and

all records maintained by the defendant or any other person

or organization on which the defendant relies in answering

the interrogatory or which pertain to or relate to the

information called for by the interrogatory:

1. Under the laws of which state of the United States

is the General Fireproofing Company incorporated and existing

as a corporation?

2. With respect to the business conducted by the

i

General Fireproofing Company:

3 1 "

(a) Describe generally such business.

(b) State whether the Company is qualified to

do business in the state of North Carolina.

(c) Describe with particularity that part of

such business that is conducted in the State

of North Carolina.

(d) State whether in the course of such business

the Forest City plant sells or delivers products

or services to persons or places outside the

State of North Carolina.

3. State whether any work done since March 16, 1966, by

General Fireproofing Company has been done or is presently

being done pursuant to a contract with any department of the

United States Government. If the answer is "yes" state:

(a) The nature and duration i.e. dates of each

contract;

(b) The name of each contracting department or

agency of the United States Government;

(c) whether General Fireproofing Company is

required by virtue of such contracts to

maintain records which indicate the race

of its employees for purposes of Federal

contract compliance review. If so, describe

and designate each such record for its North

Carolina employees;

(d) whether General Fireproofing Company has

submitted any reports to any department of

the United States Government which includes a

racial breakdown of its North Carolina employees.

If so, describe and designate each such report,

date of which each such report, the department

- 3&

or divisions of the Company covered by such

report, and the agency to which such report

was submitted;

(e) the name or names and addresses of each person

since March 16, 1966, who has the responsibility

for the negotiation of said contracts.

4. State whether any of the Forest City facilities have

been subjected to a review by the United States Government

Office of Federal Contract Compliance at any time since July 2,

1965. If so, describe each such review in detail, particulariz

ing agencies, dates, nature of reports.

5. State whether any of the Forest City facilities have

been subjected to an investigation conducted by any division

of the United States Government Department of Labor at any

time since July 2, 1965. If so, describe in detail.

6. Are any employees of the Forest City plant classified

according to departments or areas of employment? If so, list

each department and job category within each department into

which employees are divided, and give a written job description

for each such job category. If no departments or job

classifications are utilized, describe specifically how

employees are organized.

7. Does the Forest City plant provide training courses

for any of its job classifications described in interrogatory

#6? If so, specify in detail.

8. List the name and sex of each Negro presently

employed in the Forest City plant, and indicate with respect

to each such persons - -... ------

(a) date of ̂ initial employment and stating wages;

(b) initial job category

(c) each promotion to a higher job category since

initial employment, indicating present job

- 33 -

category; date on which each promotion

occurred.

9. List the name and sex of each white person presently

employed and indicate with respect to each such person:

(a) date of initial employment and starting wages;

(b) initial job category;

(c) each promotion to a high job category since

initial employment, indicating present job

category, date on which each promotion occurred;

10. Have any persons been discharged from the Forest

city plant since July 2, 1965? If so, give for each such

person :

(a) Name

(b) Date of Hire

(c) Race

(d) Sex

(e) Last job from which fired

11. List the names of Negro employees who are foremen,

assistant foremen, and/or supervisors; the job categories

under their supervision; the number of employees working

under them; and the length date and year of time each person

has served in this capacity.

12. List the names of white employees who are foremen,

assistant foremen and supervisors. The job categories under

their supervision; the number of employees working under them;

and the length of time date and year each such person has

served in this capacity.

13. State the minimum qualifications an applicant for

initial employment must possess for each job classification,

including any differentiation based on sex. If qualifications

have been reduced to writing identify specially or attach

-

a copy of each job classification.

14. Are there any job classifications in respect to which

the Forest city plant has not since January 1, 1960 employed a

Negro female but in which white females have been employed? If

the answer is in the affirmative identify each such job

classification.

15. Are there any job classifications in respect to

which the Forest City plant had not since January 1, 1960,

employed a Negro male, but in which classification white males

have been employed? If the answer is in the affirmative

identify each such job classification.

16. Are there any job classification for which only

men are considered functionally able to perform?

17. Are there any job classifications for which only

women are considered functionally able to perform? If the answer

to either (16) or (17) is in the affirmative specify such

job classifications in detail.

18. Describe specifically all methods used in recruiting

new employees at the Forest City Plant including but not

limited to:

(a) Advertisement in local media

(b) Use of Employment agencies

(c) Word-of-mouth referrals

(d) Walk-in applications

19. If all the methods listed in (a) through (d) of

interrogatory 18 are utilized, which one has accounted for the

greatest number of new employees since January 1, 1960?

20. If advertisement in newspapers are utilized list

the names of all such newspapers, and the dates ads were placed

between July 2, 1965 and December 30, 1966.

21. If employment agencies are utilized, list the names

of all such agencies and the name, race, sex of all persons

- * 5-

referred from such agencies between July 2, 1965 and December,

1966.

22. List the names, race and sex of all referrals

listed in response to interrogatory 2l who were not hired

between July 2, 1965 and December 30,1966.

23. If word-of-mouth methods are utilized for recruiting

new employees, state whether the Forest City plant has any

method of informing, or on occasion does inform, employees of

job vacancies which occur in the plant. If the answer is "yes”

describe what method is followed.

24. Are applications for jobs as a result of any of the

methods listed in interrogatory 18 accepted:

(a) only when there is a vacancy to be filled?

(b) or are they taken at all times regardless of

present vacancies?

25. If the answer to interrogatory 24 is (a), what

disposition is made of excess applications once the vacancy has

been filed?

26. If the answer to interrogatory 24 is (b), is a waiting

list utilized? If the answer is "yes" what method is utilized

in selecting new employees from the list?

27. If a waiting list is utilized, is any differentiation

made between the sex of the applicant? Are separate lists

I

utilized on this basis?

28. With respect to the persons who have applied for

employment with the Company at the Forest City facilities

between July 2,1965 and March 16, 1969:

(a) State the number of such persons with respsct

to each job classification.

(b) List the names, race and sex of such persons who

have been employed with respect to each job

classification and date employed.

29. State the name; address; job titles or positions,

brief description of responsibility of all officials or

personnel who are involved in the consideration of persons

for employment and/promotions.

30. If tests are administered as part of consideration

of initial employment, state:

(a) names of each test and job category where

each such test used;

(b) date use of each such test initiated;

(c) passing or cut-off score for each such

test;

(d) name and address of each person who has

responsibility for the selection and administering

each such test;

(e) describe and designate any and all studies

conducted on the use of each such test, dates

and names and addresses of each such person

involved in the test evaluation.

31. If tests are administered as part of consideration

of promotion from one job category to another or from one

department to another, state:

(a) names of each such test and job category where

each such test used;

(b) date use of each such test initiated;

(c) passing or cut-off score for each such test;

(d) name and address of each person who has

responsibility for administering each such test;

(e) describe and designate any and all studies

conducted on the use of each such test including

dates, names and address of each such person

involved in the test evaluation.

-Vi-

32. Describe and designate all records maintained

pertaining to the employment history of employees and under

whose custody said records are maintained.

33. State whether following the decision of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission, finding reasonable cause

in the charge filed by plaintiff in this suit, the defendant:

(a) made any statement, oral or written to

its employees concerning the decision, and

if so, what it saidj

(b) made any statement to the press or news media

concerning the decision, and if so, what it

said.

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that a copy of such answers must be

served upon the undersigned within fifteen (15) days after

service.

This _____ day of September, 1969.

ADAM STEIN

216 West 10th Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

f'

CONRAD O. PEARSON

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG

ROBERT BELTON

SYLVIA DREW

--- 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiff

- 38-

1

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SHELBY DIVISION

;VIB MAE LOGAN,

PLAINTIFF,

]

v. CIVIL ACTION

No. 3050

THE GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY, ]

a corporation,

DEFENDANT. j

ANSWERS AND OBJECTIONS

TO INTERRO CATO RIE 5

NOW COMES the Defendant, The General Fireprooflay

Company, and makes the following answers and objections

the interrogatoreis served upon it under date of Octobc

1969, by the Plaintiff, Nettie Mae Logan. The answers

objections are numbered to correspond with the interrog

as numbered by Plaintiff.

1. Ohio.

2. (a). The manufacture and marketing of office and

business furniture and equipment.

(b). Yes.

(c)

Scaring.

Chartour

ccoapar.’'

hut « __

C.l t 1

. The manufacture of upholstered and moral

The Defendant also has a District Sales Manag

e, North Carolina, who performs sales work for

as a whole in North Carolina and in South Caro.

• The Forest City plant performs no sa.aa

regularly ship products to persons and places

m e Stare of North Carolina. The Forest Cray

althoughgenera lx'/ performs no services outside ho run Carolina,

a plant employee may on rare occasion go outside the state

to handle some special service problem.

3. and h. The Defendant states that the Forest City plant

has from time to time done work pursuant to contracts with the

United- Stares Government, a no uhau m e United States Govern

ment Office of Federal Contract Compliance, to the knowledge

of any of Defendant's personnel at the Forest City pmt, has

not conducted any review of any kind relating to the Forest

City facility. During the first quarter of each year, the

Forest City plant fills out and forwards to the home office

at Youngstern, Ohio, Equal Employment Opportunity Employer

Information Report H O —^, wme n form snows on ius face that iu

is promulgated by the Joint Reporting Committee for the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission, the Office of Federal

Contract Compliance, and the Plans for Progress Program. ' The

General Fireproofing Company at Youngstown, Ohio, in turn files

tnesa retorts ror tna company as c. w ..Oj.g , ant tor alx reporting

uni as, as racuired. Trails r o m docs contain a racial and

sexusi b r e a .w cown ox ane No ran Carolina employees.

The Defendant oi’cccs go laxing rurbner answers to

Interrogatories Nos. 3 and * * on tne ^rounci m a r the remainin5'

paras or suen inherrogaaones are non re^evanc ao ane subjset

matter involved in the pending’ acaion/ as required by Rule 26(b)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

5. No.

6. Yes. The deparaiuenas and job categories or classifications

are set forah below.

_9_

- / o -

h. Maintenance Department includes electrician? die

maintenance; machinist; millwright; woodworker; oiler &

greaser; tool crib clerk; foramen; and intermediate foreman.

B. Welding-Frocess Stock Department includes foreman;

intermediator foreman";”~steeT'welder; aluminum welder; buff

aluminum & steel paras; Xerox expediter; Xerox schedule and

repair; parts and service; welding expediter; production

expediter; resistance welder; base repair; spot welder

timekeeper; layout, contract <* repair; automatic leg welding;

automatic base welding-; -drill counters, sink & tap (auto);

Xerox packer; rougn grinder; dri^l press operator; load and

unload wash conveyor, rack Sc utility.

C. Finishine- includes foreman; intermediate foreman;

paras & service; uaia.ruy wash; touch up & wash; disc grinder;

horizontal rimsoer; polisher cosmo; saw, drill & tap; rough

a rinisn pOa.1 s.1 er; side oooun — nnxsn; wneeo. off; buff

aluminum & steel paras.

b - Anc ...1 zinn includes roreman; paras d service; lab

teenmeian; frame cleaner; beat trout & anodize operator

wash & paint operator; stationary tank man; heat treat &

anodize helper.

E. Press toe : incerrriedic.‘c0 r or or. an # prsss feeder

and/or helper; shear helper; curoof Irrko operator; saw

operator; burr opera cor; parkor di— .; milling macl.ina operator

inane) ; ni__xng maenme operaaor (sciu.g ; snear operaaor; crane

operaaor; .urge press operaaor; auco...aaic press ooeraaor;

'--te sourer; uube bender operator; oraxe render operator; bender

— u ̂-or cv j.c.yo'u a; xdVOUu/ coii ujTgC l. f raptor.

H

F groupF. Uoholstcrv: forer;lan; intermediate roreman; group

foreman; parts & service; tirucker; uoiiioy; finisher (fabric);

sewing machine operator; ut:ility & gluer; upholstery cutter;

arm puller; timekeeper; mat

upnoIstorGC; 1ayout—pattere

serial die cutter; makeup upholstery;

G. Final hssembl-: foreman; intermediate foreman;

oucuS & service;un!oc.der 2 chair bolter; final assembly

clerk; conveyor packers; forial assembler; 200 li :e case

asserubler; sideline asscrub̂ Ler; head packer (conveyor); side-

line packer; assembler - nc

repairman.

Gad operator; umekeeper; base asserio 1 e

H. V7arer.ov.ss - Sri'.::.:■ - ; foreman.- parts a service; snipper

checker; order filler; orc.<sr checker; order scenciier/checker/

warenouse ne-Lpar; .̂.̂ .p̂ >ii*g clerk-

j. Fort- r Four: ir cermadiate roreman; assembler/

inspection and pac.;; eagre;ise d drill; roach polish & oil,

curb 1 t bender cor; c.u <

weldor.

g o oraee v/o— amg; resistance & mig

L.R.?. - S.h.G. - keeaivi'. — Storeroom: rore.uan; scock

ruan; ratalr oaruc clerk; r»sceivinc,- clerk; repair parts shipper.

P# 3?Cii’.“ieinz z ore*nan; in"cer...edj-cii»G ~ô .oihc.4* f z>c\a. c.s o: service

sreel v/colcr a loader; ĉ.ss-C.v iror. uosanoier; sane. a putty

g\q//-; direr, soraver onezaeor; rouen up sprayer7 xOog a umoad

iouinu c g u/ayor, ; pc.mu u m i t y ; promar c/prc.yor au/l ; armor

hide spr-yer; finish clear sprayer.

lurches err - Fauerial C o m rcl: department head; asst.

c.e r.r'c..u..G need; ou rery c—1ass e; ûGc..coir.c.’ order c i o t k;

■ ' ■;-trial 2roc:dr.ecu: - Tiros Stacy: Industrial engineer? clerk

*” ■■ -1 -* »- * c 1.vce stuty , Cs_ass e -

-

6department head junior csiitucor, class

Traf ::h c-Shlou.i r..~: department head; traffic clerk., class 5.

p _l cx 1*1 t S c - lT r 5 u v i c. c p s, r true hl h 0 n ci 7 s 0 c u,;rity guard, class 5.

Product '\ncineerino: department head;

7 .

• draftsman, class

du uj. it''' Ccacrou- Inopeccaont r oror.ar;

inspector, c1 a ss 1 .

assasuanu io xema n 7

’roQucc..on 6 onv.ro..: department .:e<.u; <

O U O U. jV , C J. d S «—1 fc-' / d d d X O * i Gj *W d J_ d e* A. ,*

. 0 st. department head;

Accourvcinr "nar'rcnh: department hocxd; accounts payable

clerk, class 3; accounts receivable c.L o m , C la ss r ;

accountang c_.erx., c—as3 0 ; recepuronrist, class 1.

P e r s o un c..: d e pa r u vxe n u n a a d ; cisrx, c _..ass u> 7 nurse, crass d •

Or no r rrocessruo: c—o m , c _u a s s d 7 cvistomar service, class

d.D.?.: department programmer, cl._ss 7; key punch

operator, class 3; computer operator, class 5.

Plant yar.Ec.-em.vnt: Plant M-rager; sec touary, Cu.as3 d .

Factor'/ Superintendents: plant super;-nuendent.

-he wag'd rate ranges applicable \;o ail hourly paid

V.J.C. ...........-— W..O .... ...... d.L.,

bne salary ranees a pp __ a c >—b _ e uo t.alaried non-exempt

cauenouuas axro snev/n x.n une documenu cattached hereto which

hears '.. . he .drug “uor-Sxtmpt Salaries• W.-..;;o Range Scale Chart".

One m a s a nua.oer3 a * up _ a c a o j. e uo Vc.rrou Soiaraea n o n ~ e x empu

cauegoraes are arai.cauea an m e c.uove a n s\ ;e r.

Ail written job descriptions v.kic• n exx.su are a^so auuacneo

O v-C , Uv.C bG~dnd»*..a Sw*-. v-'——< '-“'•■a m<_*.,y Os. d** ose may be

ox. u o_ uaua and. m a t tnose cxaacrapuaou-S may or may not be

- H ? ~

/ . Ti'.G Forest Cxuy pj.unc ptcvicou r*o ^ro~o.pj,; oyt.'onF tuxIn—

ing courses. Froro time to tr’mo, 'the corapar;/ has permitted

people who wanted to learn the particular kind of sewing

required ao m i s p a no *co cone in on■ meir own rime sriQ

m e m e coipuy's -owing machines mid has had the supervisor

to help these persons.

The Mainten nee Department, at random intervals, has

conducted courses dor employees in the d:gnriment who

expressed a desire so learn, on the employee's cv/n time, in

blue print reading and shop theory. The purpose is to enable

existing employees to improve their skills and progress.

From time ,.o time, the company has permitted existing

employees v.mo so requested m come m on moir own time

and be taught seleesiva and limited welding operations.

c5. and 9. Tne Darenaanr. oogaoss so mese irrcerrogatories

in their enmrety, and stares that the Da rend cant, to answer

these ir.ueruogauories, would have to examine approximately

oOu seporma parsonns — riu.es m cere and oo perrom

.sD e> r o x m u i -A

JO.

corera

n g ana coxiating tne

nre Courc nas a joroad

^covery,

ana expenses

t v. . r m :, C?» Ca-. —968, 398

o n nc xco '/ - 3. , C*-- Aua. u-9d9, 4-̂ 6 F. 2d 7 o-6;

o. v. S^lk, CA Fa. 19.69, 401 P. 2d 843), considering

- - - —• — C.vĴO or

Co. v. Parana

Pk Serv 2a oc

n connection

-cular case

rsurir.cf Co.

-u -J jV V0 540).

ra t-ne -oresent ca;e, the Plaintiff has admitted on deposition

that she has no g'rour.ds wnatever rot c«ny Ot cne aj_ legtcions

contained in het c^ass action, hut merely \nsii0 3 Detenosnu

to supoiy voluminous answer- in the hope than sore violation

of the law mav perchance he found therein. in tnoso cir

cumstances , the Court should exercise its discretion to

require the Plaintiff to pay the Defendant, in advance, for

the time and effort required to answer such voluminous in

terrogatories before requiring the Defendant to answer.

10. Yes. Tne Defei *VlC* objecus to e.nswerrng

further on •the grounds sat forth with regc.ro. co Interrors

torres it as. o cine ip / nr. a ruruner on c<re ground unu t uis in'

terrogatory does not s eex rnre m u u r on v/hi ch r s re levant to

the subject matter or tne penning action, m tout there j_s

no complaint allegation tnat tne w erer.aanc uus discruninuueci

against negroes or women in the matter of discharge. Further

Derendant s—utes ttet — v/̂ u.ci i.avc uo s i f ;c through upp:roxi

mately 1,000 closet persor.net rites in oroer uo extract the

information requested, and it r.as on1V one employee who is

s\iifflcien'cl'7 rc.’i\ u.j.2-3.r wiun *cne personnel recoros co uo tnis

Y/orx. pnrener/ Z)e r endurre s re res unsc j_c r s w<. i ± do 1 0 co answer

Interrogatory 10(c) oecsuse res recorcs ro co noc iCienciry

discharged employees by race and it does not otherwise have

this information.

11. Horace Gerald Thompson has bean department foreman

in the Warehouse-Shipping Department since July 4, 1965,

o ” *, ĉ r/- * r, * —'4 d" 1 cv.c a n w» »vi Cc. wcCjUi j.c o * .a iCc* uGC j- n l.h G

. r- y.- cr r co j_n cerroc,».«. e.o—. y n v> • o»

-7-

tj .-..ici) hw — o v,y ** U *5 be O. i u 4̂ * 4 —ppa 4 . v. j 4 O .1*4 4-**0 h c* r e —

house-Shippinc; Department since :cove.v.ber 1, 1953, and he super

vises 3 employees on the second shift, who arc an order

stenciler and checker, a trucker, ana an order puli*. .

Richard wiikerson has been a Shipper-Checker in the

and he supervises 9 employees in the categories indicated

m tne c.nsweir 'co .xivcerrogsuGr y c.o. c- ag i s a;'is i s_c< nu 'co

CiOrSCG vj'-iiTv. J_ui x'-.G..peOr. 0*1 c.**vp G o*y 5**1 j. u .

12. i‘G.0 fOiu.GlTl.r.G Vv.'.i'CS CCGpGyGG3 c*GTG rOrGAGOn , 0S31S‘Cant

foreman or supervisors in ore deperuments incicared by

cGpiv.ui icGters rare nnG gig m e enswgr co 1 no e r r o g* c* u ory

a g . 6. tne liuCOcC or ervpj_oyGGo u-'.Gcr cnee r supervision is

i m c n ’CcG ccx-ov/icc m e eccr design*— roc o ̂ g ap o. rcmecc,

end. tie cere xO-xOvciGc,- is aha dare ■v/hen eacn assumed the

posit ion rn cuesu_o.-.; Proo r.c Dgv/g ̂ -4 Tu. y h a y 17, 8-5-53; Billy

A. y -j-O / d”J“G j 77 8—5—557Scras 9 s- — iid.Gu_ O. y

tiCries ii-i—58; Ac cruggs, b., 76/

ii--~63; Arl=n halacr, 3. , 75/ 1 1 - 1 -co, 3-n Schuller, C.,

c2 ; 8—5 —o^/ .\cccrc tOicS y C a/ o 2 / -ar--~3S; Brj.1 fkC.ll/ C. /

527 3-1-r b ; 51cmg s Scccc / 5. , u.5 / b-b-oo 7 arry Garable, 3.,

4 3 / 3-5- 0 0 7 ccr-. f.drric i £* • t 4 b / i —-1 — 33; Prec Logan, 2«/

4 J y -i-i—8 0 7 Pren/c CereSoy, .5. / —bo , o-a-33; Steve Carroll,

* • / 150, 11-1-55; B~y 15aachi- * S / A • / -4.0 O y - x.—x—58; Herma n

hennicy, f • / xOw ̂ ~ 5b 7 Jr. cic.v.at. . C 3 y bay -4-bOy X. 1 “ 1 “ 6 8 7

ormen x<uykendall, O' CO , 5 b; Bobby P uC G a ; CJ r a / 3 S y

9-1—55 ■’ habur.'. Carpantar, I*.y — «-> y —1-1-33; Cube,, u L' A * -L. l_G / a /

3-., ii-i-oS; Bobby bdwa— ° y G . y b G y --—— c b; Cacr 1 a arris.

i-- , oC, s—1—39; Oliver C—m e nco G., 50, 11— X. —0 0 7 OxTu

-lord, G • / b G y x — — — Oc* •

—3 —

%

As to departments not designated bv lette

a o . o / unc a.ricomaeion, in ur»G sc**r>e r o * u, is c*.

Purchasing-Material Control, Joe Brown, 5, 6-1

Jolly, 4, 6-1-69.

I'rMuS Mngrneerang — lame Study, uonn Cĉ rg

iO“x_oo•

Mstimating, Marl Durnil, 2, 8—5—5s.

Product Mngineering, Clarence Hard, 2, o—5—So.

C u a a a cy CoivcjOx-J.nbpac m o n , xjc.o..c»rci uc.Ca ^oii , j.

John Davis, 9, 11-1-S7.

Producenon Conuro— , ec.u_L .wOu-iTCciic;, o .

5 , 5 -1 -S S .

Accounting, Gene At — — ** j i 5 — oS .

Personnel, P.2. it'.V.undson, 2, 8 —’.-67.

2.D.P., Steve Padgetu, 7, 11-1-6S.

Plant Management, S.M. Lovelace, 1-15163.

Factory Superinuenuenus, Ray Meacemrocn, Day

supervises all plant foromen pj.us menu supen

e— x—56.

- 1 1

r in ansv/er

s follows :

-59; Nick

ill, 4,

0, 4-1-66;

0ernes Parker,

Superintendent,

ntendents,

Arlen Melton,

of all of

Interrogatory

be able to

not prescribe

bs. It is

nd/or the super-

ar an applicant

j oo.

O'

V)rOOUC ClOil ,

Shipping us

it. Mot in production • As to dept-rtme;vcs

the plant has employed a r.egro female in Traffic

a Traffic Clerk; in order Processing-Customer

Service as a clerk; in Accounting as an accounts payable

clerk; and in E.D.P. as a key punch operator. The plant

has not employed a negro female' in any other non-production

cla s sit ica’cion.

15. The plent has employed’ negroes in supervisory positions

ns indicated hereinabove, but not in others. The plant has

not employed any nacro males in department other than those

de sigma re a n . c n r ot g* n an answer lo. o • T.*e plant nc*s

not employed any negroes in Department A. Maintenance, since

e i*p roxrmeej_y ~j_~oo, r̂.*~ô. »— -w* w **j.c*x t..cti liciCĵ Oco v/Gxs

employee as j a n a t o r s. Tne p-uv.nt no monger jarioSiis endu.

function for itse_f. negro males nave teen emp_.oyeo an

a_̂.a c—assaracatacne an m e omer depc.r u-s deSa-̂ nc; ced

bv letters 3—M, fro.'.1; tame to tame, accorcang to tne

best recollection and belief: of Defendant:s Personnel Manager

eno. Personne_ c_m :j a_t notgn at x.i. t ; as c* ^rcxccxca ■.

matter, to a^eertevan tmas teyo-.o a..y Ov_ntc.

xo • Tne c ue^ j.o». » ̂j..o>— *o2,., a*it* .j-a i.cn»u Cv0£>uOu

have any such policy.

17. Same answer" as Lo.

j_B.. Tne riant does not aovertase ror new employees an Iocs j.

pri'va ly operated employ-

ni'tO'Cc cy Core

- 10-

’. V Y -

The plar.u accepts appliestior.s fro:.’, parsons who apply

i-‘ person a r tne p a. a nr, m e iuc m g persons who are referred

by present eraployees. •

19. | ^/arn-in cipprrcc.cro.iS.

20. Not applicable.

have this inf oit;*a r i o n, anc. ^as no

records from wm.cn r e couic, 0 0 exrracrc

*■) Sam 2 ansv/er as 21.

3. The •oronr nas no ror..ic*a. .iioCiiw

•ord of :moutn. ’ Supervisors are pe

cougn

v/hen the’ / n0 0 c sersor-O; ano, Derencanr rs s«r£ ti.xs occurs/

but is unable to be specific. Defendant is also sure that

L05 simpl'" observe ubee a ^ob rs vec&nu or tin a

m e . r n a a suer c»spx c y < i e 3 r c - 1 r c'p p - . - i . c s n c s

on their own initiative. Applicants frow rime ro time nave

stated that they were intermed of vacancies by employees

employes* >̂on

someone nas or

wno were m e n worm

;arecess or now24. App 11 canrons are acceprec

applicant c a m to apply, at any rrme.

25. Nor appmcaora.

25. No.

27. Not applicable.

rha Defendanr dees nos know the answer to Interrogatory

scores from which this information can

rrregarory 20 (b), the

rrs personnel records

s information, excepr as ro race. rfne Derendant

.s and hso no way of

Cocerraining this information. In m e attachment, the persons

m clock nrmbers from .-.COO ro 2 0 G are women and m e

23.

2d (a), an

— OU Cl J.A. ;o rnr

m o w _ u...vb-*v:

20. Dsfsadr.nt a-s Oereina^ova, a.-ran:./ identified all or

ias supervisor/ officials sad parsior...ci o cp u rmonc /crsouuCi.

Cicse persons are all involved in the consideration of persons

for ernplcprr.ont or proper ions / cxc;xoi that the personnel

elerx is not: invo-voci. in prcao'cio:■.3. Vaeir cor.rr.oa address

, OV.e Gcac.ru 1 Fire-,roc fine- Coruoa;'.v. o.S. Hichwav 74, Forest

20. do-;.. f..--a ‘--ro-rr :'aa f.C. Erployrcant Security

COS.-oo.w.. -aowi, .car;.; ror sccretariEi skills.

04. it is aot possible to sucto ;, np n 3v r a a n a rase rule

rec-ardiar- aba use of tests ia coaticcticn v/ith promotions.

imes ere erven, and ehe res*.;lua aoasidored, v/aaaever the1

supervisors invo—vac,. ana/or m e _'ermnnei Mans per, consider

1 e auVlc^jio . Go-.e-Sc--p j V. - _u,_.. uoCu, ees es are usee in

:r icns into rca intenance

-'obs or iaso office -obs. "acre ;_s no specific answer v/ith

w-1,.. —t-O.* ica ̂ __vs; C * s v/ ̂ c, c. x u u t* fci

-.. Saurary 3-10 72, cad d.3 i'cctc: reu -.pe_cue.e Series.

Defendane dees nor l:rcv/, zrid nas no recore , as uo juse

"rrt'-*° a-e r-° *S'**~-S cr iu'c cvrr nacn case

. £_ ucc^rccbiliu-- races b,.a .....napment dees not consider

siVo or

in a is acrcini sue-:ec ay uaa s.ap_oyvaonu Security

rmsorea meieuee series — 0 C»v---ix .- j- . i u C ^ c C tJ P U liS

- n - esuriw.' p~- cJ u - v“; nc Z3'm:t;'.mc rc tbs pleat, described

— 5 ^ -

Vo

CO*.

n individual personnel file for each employee

c;:" 1 o'vaent history in wriousc'ocuaents, and

: naintainod under the custody of the

udics have t o r . corbuc:od.

xl> c iTiU n o. s o n•

JVfOLIVfh DAVIS

_— . /

> ; . \ \

Vis S3 S'. HOGG A /

m ’ • ~ W.; HOGG &

1201 Drickeli Avenue

Xiarr.i, Florida

d. iOUVHH DAVIS

103 Florence Street

Foreot City, Nortn Carolina

D3?3HDAaT

\

/

f/

GOOD;

.., J3SS3 S. HOGG, reing -irsu duly sworn,

ay c;; ;itv as Etror.iey =0;

no c'-'rc

O S C< —_ V-̂ Ar-J c

ijl Fircorooang

2 ei.cent iodicc-tec

iCiV0 ir/borriroyatcG.

:j c.: go v.VxIca

i)GS"C. O i

iV/OcOT GOO o G GOSWG

ray ooov/gcog'o &r*o.

/ ui,SSoi S. **0GG ' J

day or

^mCiC v_ v_

/

/

---*

< 0

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT CF NORTH CAROLINA

SHELBY DIVISION

NETTIE MAE LOGAN,

p]aintiff.

v;.

THE GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY,

c. corporation.

Defendant.

5

)

)

)

)

)

O R D E R

CIVIL ACTj.CN NO. 30 50

jANi9t97C.

•iOS. E. RHODES, CLER.<;

THIS MATTER was before the Court on December I, 1969,

for pre-trial conference and for hearing on defendant's Ob

jections to Certain Interrogatories propounded by the plaintiff

to the defendant. The pre-trial conference calendar was pre

pared and copies of the same mailed vo the attorneys for both

parties on November 14, 1969. On November 25, 1969, the

defendant'a attorneys filed Objections to Certain Interrogatories

propounded by the plaintiff to the defendant on October 23, 1969,

and notified plaintiff's attorneys that they would move for a

hearing on said Objections at the pre-trial conference scheduled