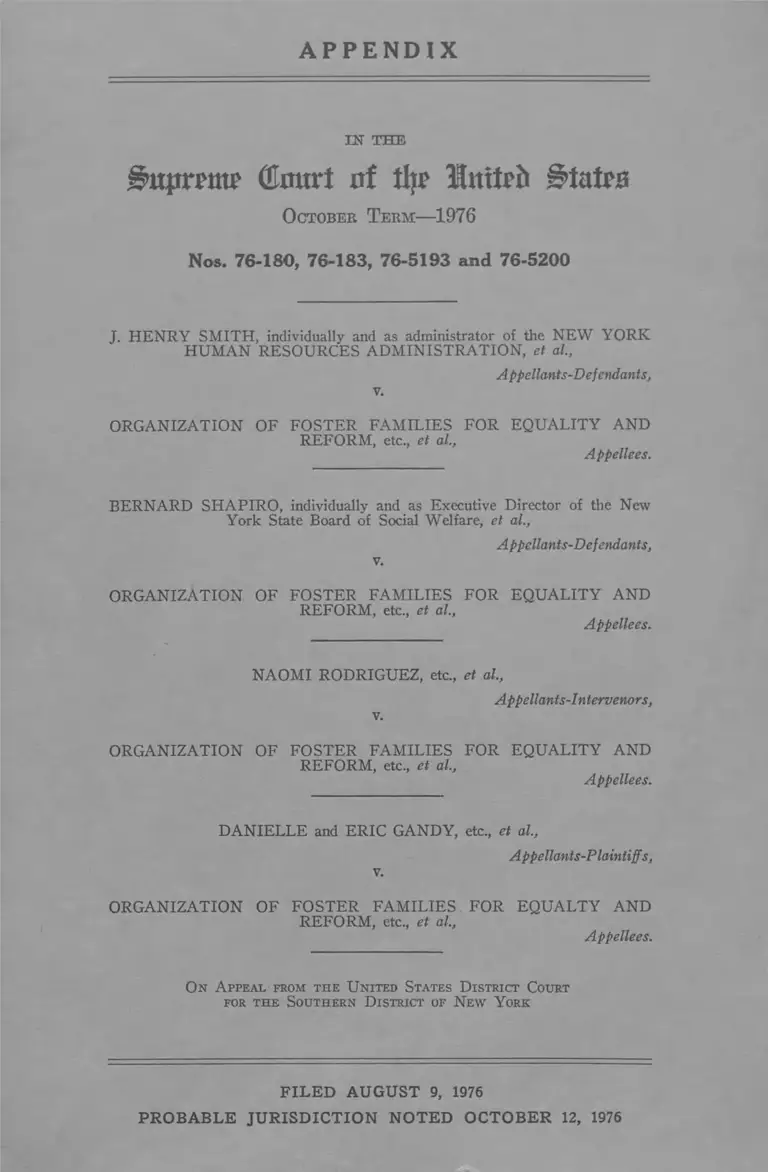

Smith v Foster Families for Equalities and Reform Appendix

Public Court Documents

October 12, 1976

322 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Foster Families for Equalities and Reform Appendix, 1976. c9302eb5-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b9129bc3-b7bc-4be4-b57e-d4285fe7a19d/smith-v-foster-families-for-equalities-and-reform-appendix. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

A P P E N D I X

IN THE

gutprpm? (Emtrt of tip Umfrfc §>tata

O c t o b e r T e r m — 1976

Nos. 76-180, 76-183, 76-5193 and 76-5200

J. HENRY SMITH, individually and as administrator of the N E W YORK

H UM AN RESOURCES ADM INISTRATION, et al.,

v.

Appellants-Defendants,

ORGANIZATION OF FOSTER FAMILIES FOR EQUALITY AND

REFORM, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

BERNARD SHAPIRO, individually and as Executive Director of the New

York State Board of Social Welfare, et al.,

v.

Appellants-Defendants,

ORGANIZATION OF FOSTER FAMILIES FOR EQUALITY AND

REFORM, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

NAOM I RODRIGUEZ, etc., et al.,

Appellants-Intervenors,

v.

ORGANIZATION OF FOSTER FAMILIES FOR EQ U ALITY AND

REFORM, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

DANIELLE and ERIC GANDY, etc, et al,

Appellants-Plaintiffs,

v.

ORGANIZATION OF FOSTER FAMILIES FOR EQUALTY AND

REFORM, etc, et al.,

Appellees.

On A ppeal from the U nited States D istrict Court

for the Southern D istrict of N ew Y ork

FILED AUGUST 9, 1976

PROBABLE JURISDICTION NOTED OCTOBER 12, 1976

I N D E X

PAGE

Relevant Docket Entries ................................................ 3a

Second Amended Complaint* .......... ......... ....... ........... 13a

Exhibit A ...................................................................... 37a

Order Convening Three Judge Court ........................... 39a

Answer of New York State Defendants*..................... 41a

Intervenor Defendants First Amended Answer and

Cross Claim* .................................................................. 49a

Trial Exhibit “A ” .................................................... 63a

Trial Exhibit “ B ” .......... - ................. ............... ...... 65a

Affidavit of Naomi Rodriguez ....... ........ _...... *..............- 68a

Affidavit of Sara Ruff .............................................. ..... 73a

Exhibit “ A ” .......... ................... ........._______ 76a

Exhibit “ B ” ................ 79a

Answer o f New York City Defendants* ..................... 82a

Affidavit of Carol J. P a rry ....... .................. ... .......... . 87a

Child Caring Agency Request For Approval Of:

(Form W-853, 8 pages) ............................ .......... 95a

Excerpts from Deposition o f:

Dr. Shirley Jenkins ................................ 96a

Eugene A. Weinstein, Ph.D............................ 105a

* Indicates Affidavit of Service omitted in printing.

n I N D E X

PAGE

Excertps from Deposition of:

Robert Catalano ............ - ......—- ................. - ......... 114a

Dr. Stella Chess ............— .... ............................. 119a

Mary Jane Brennan .................................. - .......... 132a

Agreement to Remove Child From Foster

Family Care ...... ..............— ..................— 138a

Peter Mnllany .... .......... ........... ..... ......... ............... 141a

Curriculum Vita—David Fanshel ................. 147a

David Fanshel ........... .......... ..................... ....... ..... 158a

Joseph Goldstein ......................... - .......................... 191a

Albert J. Soln it.......................................................... 207a

Exhibit No. 1, Resume of Henry Ulmann

Grunebaum M.D....................................... 236a

Dr. Henry Uhnann Grunebaum ........................... 247a

Excerpts from Transcript of Trial on March 3, 1976 - 262a

Dr. Marie R. Friedman ....... ................................. 262a

Florence Creech ........................... ........................— 272a

Jane Edwards ..................................... 286a

Christiane Goldberg ........... 293a

Dorothy Lhotan ..................... 300a

Cheryl Lhotan ........ .............. .............. ......... ...... H 304a

Naomi Rodriguez .............. 307a

IN THE

i>ujrnmt? (Emtrt nf i\}% lultrii

October Term— 1976

Nos. 7S-180, 76-183, 76-5193 and 76-5200

--------------------- _♦-----------------------

J. H enry Smith , individually and as administrator of the

New Y ork City H uman R esources A dministration, et al.,

Appellants-D ef endants,

—v.—

Organization of F oster F amilies for E quality and

R eform, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

Bernard Shapiro, individually and as Executive Director

of the New York State Board of Social Welfare, et al.,

Appellants-Defendants,

—v.—

Organization of F oster F amilies for E quality and

R eform, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

2a

Naomi R odriquez, etc., et al.,

Appellants-Intervenors,

- y . —

Organization of F oster F amilies for E quality and

R eform, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

Danielle and E ric Gandy, etc., et al.,

Appellants-Plaintiffs,

-v.-

Organization of F oster F amilies for E quality and

R eform, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

A P P E N D I X

3a

Docket #

1 5- 9-74

2 5-13-74

3 5-23-74

5 5-31-74

3 6- 5-74

Relevant Docket Entries

Filed Complaint and issued summons.

Filed pltf’s affdvt. and Order to Show

Cause for a T hree-JuDGE-Court and why

defendants should not he enjoined. De

fendants are temp, restrained from remov

ing Eric and Danielle Gandy from the

home of Madeline Smith. Posting of Se

curity is waived.— ret. 5-17-74 at 2 PM in

Room 512— Carter, J.

Filed pltfs. affdt. and notice of motion for

an order j o in ing Ralph and Christine Gold-

bert (sic.) on their own behalf and as next

friend for Rafael Serrano as pltfs. in this

section (sic.) ret. on: May 31, 1974.

Filed stip. and order that the T.R.O. issued

on 5-9-74 he continued until determination

of pltf’s motion to convene a three-judge

court and if motion is granted until the

hearing before such a three-judge court:

counsel for deft. Dumpson, Beine & Dali

to not appose pltfs’ motion to join as plain

tiffs Ralph and Christine Goldberg on

their own behalf and as next friend of

Rafael Serrano—the return of pltfs’ mo

tion is adj. to 6-5-74— Carter, J.

Filed memo endorsed on pltf’s motion to

join parties: Motion granted by consent.

So ordered— Carter, J. m/n

4a

12 7- 5-74

14 7- 9-74

Docket #

9 6-25-74

16 7-15-74

31 8-14-74

Relevant Docket Entries

Filed affdvt. and notice of motion on be

half of Naomi Rodrignez, Rosa Diaz, Mary

Robins and Dorothy Nelson Shabazz to

intervene—ret. 7-24-74

F iled Second A mended Complaint

Filed order designating in addition to

Judge Carter, to hear and determine said

cause as provided by law: Edward Lum-

bard, C.J. and Milton Pollack, D.J.—Kauf

man, Ch.J., C.A. m /n

Filed pltf’s affdvt. and Order to Show

Cause why an order should not be entered

granting pltf. preliminary injunction

against defts. Order that pending the hear

ing and determination of tiffs motion, that

Joseph D’Elia be temporarily restrained

from removing Cheryl, Patricia, Cynthia,

and Cathleen Wallace from the home of

Dorothy and George Lhotan, and it is fur

ther ordered that posting of security is

waived—personal service by 7-8-74 at 12

noon.— ret. 7-18-74 at 10 AM in Room 310—

Carter, J.

Filed pltfs affdvt. and notice of motion

for class action.*

* All motions were contested unless otherwise noted.

5a

Relevant Docket Entries

33 8-19-74 Filed order that plaintiffs’ motion for the

convening of a three-judge court pursuant

to 28: 2281 and 2284 is granted; ordered

that pltfs’ motion to join Dorothy and

George Lhotan, and Cheryl, Patricia, Cyn

thia and Cathleen Wallace as parties plain

tiff, and Joseph D’Elia, Commissioner of

the Nassau County Department of Social

Services, Bernard Shapiro, Executive Di

rector of the N.Y. State Board of Social

Welfare, and Abe Lavine, Commissioner

of the State Department of Social Services

as parties defendant is granted; ordered

that deft. Joseph D’Elia he restrained from

removing Cheryl, et al. from the home of

Dorothy and George Lhotan, pending hear

ing before the three-judge court and a de

termination of pltfs’ motion for a prelim

inary injunction. Further ordered that the

motion of Naomi Rodriguez, Rosa Diaz,

Mary Robins and Dorothy Nelson Shabazz

to intervene as defendants is granted solely

for the purpose of litigating the issues

contained in pltfs’ 2nd amended complaint;

. . . — Carter, J. m /n

36 9-24-74 Filed A nswer of defendants Bernard Sha

piro, indiv. and in his capacity as Execu

tive Director of the N.Y. State Board of

Social Welfare and Abe Lavine, indiv. and

in his capacity as Commissioner of the

N.Y. State Dept, of Social Services.

Docket #

6a

42 10-17-74

43 10-17-74

46 10-25-74

51 11- 8-74

59 12-11-74

Docket #

37 10-15-74

62 12-31-74

Relevant Docket Entries

Filed plaintiff’s affdvt. and notice of motion

to declare N.Y. Social Services Law §§

383(2) and 400 and Title 18, N.Y. Codes

Rules and Regulations §450.14 (now re

numbered §450-10) unconstitutional, etc.—

ret. 10-29-74 at 4:00 PM.

Filed Notice of Motion for leave to join

as additional party intervenor deft, and to

amend Answer.

Filed Motion of Intervenor Defendants to

certify class.

Filed Defts Lavine and Shapiro’s Affdvt.

& Notice of Motion for judgment on plead

ings.

Filed Plntfs Affdvts. and Order to Show

Cause for hearing on plntfs Rule 17(c)

Motion.

Filed Opinion 41563 of Carter, J., denying

motions to continue N.Y.C.L.U. as counsel

to foster children or to appoint Dr. Ken

neth Clark as guardian ad litem to chil

dren. Court affirms Ms. Buttenwieser as

independent counsel to children.

Filed by Attorneys Marcia Robinson

Lowry and Peter Bienstoek notice of ap

peal to the IJS'CA for the 2nd Circuit from

7a

Docket #

64 1- 3-75

73 2-28-75

74 3- 5-75

84 6-25-75

Relevant Docket Entries

order of 12-11-74, disqualifying counsel to

the plaintiffs herein from further repre

sentation of plaintiffs Rafael Serrano,

Danielle and Eric Gandy, and Cheryl, Cyn

thia, Patricia and Cathleen Wallace, copies

mailed to Helen L. Buttenwieser, Esq., Stan-

ler Kator, Esq., Elliot Hoffman, Esq., Jack

Olchin, Esq., Louise Ganz, Esq.

Piled by pltfs’ Foster Children Danielle

and Eric Gandy, Raphael Serrano and all

other children similarly situated for an

order (a) desolving restraining order (b)

terminating the effect of a stip. entered

into in lieu of a stay which presently pre

vents the Catholic Guardian Society and

the N.Y. City Department of Social Serv

ice from making a determination concern

ing the named plaintiff children who are

their responsibility, etc.— ret. 1-10-75.

Filed order that the trial of the T hree-

Jtjdge Court be held on 3-3-75 at 10 AM—

Carter, J. m /n by chambers.

Piled true copy of USCA stip. and order

that the appeal dated 12-31-74 is hereby

withdrawn without prejudice.

Filed Transcript of record of proceedings,

dated March 3, 1975.

8a

Relevant Docket Entries

Docket #

89 10- 1-75 Filed deposition of deft, by Eetta Fried

man—dated 4-1-75 m/n.

90 10- 3-75 Filed deposition of Dr. Joel Kovel on

April 2, 1975.

91 10- 3-75 Filed deposition of Eugene A. Weinstein,

Ph.D. as a witness on March 18, 1975.

92 10- 3-75 Filed deposition of Henry Grunebaum on

April 10, 1975.

93 10- 3-75 Filed deposition of David Fanshel on April

8, 1975.

94 10- 3-75 Filed continued deposition of David Fan-

shel on May 12, 1975.

96 10- 9-75 Filed examination of defts Mary Jane

Brennan dated 4-9-75. m /n

98 12-22-76 (sic) Fid Deposition of Joseph Goldstein

taken on 4-1-75.

99 3-22-76 Fid Opinion No. 44102. . . . From TJ.S. Dis

trict Court. . . . In summ., therefore, we

conclude that N.Y. Social Services Law S S

383(2) and 400, and N.Y.C.R.R. S 450.14, as

presently operated, unduly infringe the con

stitutional rights of foster children. Defts

are enjoined from removing any foster chil

dren in the certified class from the foster

homes in which they have been placed un

9a

Relevant Docket Entries

less and until they grant a pre removal

hearing in accord with the principles set

forth above. Of course, our decision today

does not in any way limit the authority of

the State to act summarily in emergency

situations. Family Court Act S 1021. . . .

So Ordered. . . . Lumbard, C.J. & Carter, J.

mn

100 3-22-76 Fid Dissenting Opinion No. 44104. . . . I

would dismiss the complt. . . . Pollack, J.

mn Amended 3-25-76

101 3-22-76 Fid Opinion No. 44103. . . . In sum, the

motions to certify a class of pltff foster

parents, pltff foster children, and inter-

venor-deft. natural parents are granted. In-

tervenors’ motion to amend their complt is

granted except for affirmative defenses 14 &

15 and the cross-claim, which are not al

lowed; and the intervenors’ motion to join

an addl pty is granted. So Ordered. . . .

Carter, J. mn

102 3-29-76 Filed amended Opinion No. 44102 conclud

ing that N.Y.S.S.L. §§ 383(2) and 400 and

N.Y.C.R.R. •§ 450.14 as presently operated,

unduly infringe the constitutional rights of

foster children and enjoining defts from

removing foster children unless and until

preremoval hearing is granted.

Docket #

10a

Docket #

103 4-14-76

107 5-25-76

110 5-26-76

115 6-10-76

116 6-17-76

117 6-10-76

118 6-9-76

Relevant Docket Entries

Filed Order & Judgment holding N.Y. Soc.

Services Law §§ 383(2) and 400, and N.Y.C.

R.R. § 450.14 unconstitutional; stay of effec

tive date of Order and Judgment for 30

days to permit application to Justice of

Supreme Court of U.S. for further stay

pending appeal to the Supreme Court.

Filed plntfs’ Notice of Motion for order

substituting new counsel for plntf foster

children, w/memo endorsed.

Filed order from Supreme Court of U.S.

that judgment of U.S.D.C. of 4-14-76 be

stayed pending referral to and further or

der of the county.

Filed L.J. Lefkowitz, Atty. Gen. of State

of N.Y., atty. for defts Shapiro & Lavine’s

Notice of Appeal to the Supreme Court of

U.S. from 4-14-76 to Order and Judgment.

Filed Infant plntf’s Notice of Appeal to

U.S. Supreme Court, from 4-14-76 U.S.D.C.

Order.

Filed Intervenor Defts’ Notice of Appeal to

the Supreme Court of U.S. from 4-14-76

U.S.D.C. Order.

Filed Deft New York City’s Notice of Ap

peal to Supreme Court of U.S. from 4-14-76

U.S.D.C. Order.

11a

125 9-27-76

126 9-27-76

127 10-19-76

128 10-19-76

129 10-19-76

130 10-19-76

131

133

134

Docket #

119 7-16-76

Relevant Docket Entries

Filed plantiff’s Notice of Appeal to U.S.

C.A. from opinion & order ent. 6-29-76 de

nying plaintiff foster parents’ motion to

substitute new counsel for foster children.

Filed true copy of Order from U.S.C.A.

granting Intervenor Defts’ motion to dis

miss appeal from U.S.D.C. and to stay

briefing schedule.

Filed true copy of State Defendant’s Order

from U.S.C.A.

Filed true copy of Order from Supreme

Court of U.S. re: Consolidation from Ap

peal.

Filed true copy of above Order.

Filed true copy of above Order.

Filed true copy of above order.

Stipulation to replace items filed but miss

ing from docket and/or record

Deposition of Laura Mae Thomas filed Sep

tember 22, 1975

Deposition of Seymour Shapiro filed Sep

tember 22, 1975

135 Deposition of Dr. Stella Chess, with exhibit

filed September 22, 1975

12a

Docket #

136

137

138

139

142

143

144

146

148

149

151

Relevant Docket Entries

Deposition of Sydney Smerzak filed Sep

tember 22, 1975

Deposition of Albert Solnit filed September

22, 1975

Continued Deposition of Albert Solnit filed

September 22, 1975

Deposition of Shirley Jenkins filed October

3, 1975

Order to Show Cause of March 26, 1976

Defts Shapiro Notice and Proposed Order

and Judgment

Deft Smith’s Proposed Order and Judg

ment with Affidavit of April 8, 1976 includ

ing motion to reargue.

Intervenor-defts’ proposed order and Affida

vit of April 5, 1976 including motion to re

argue.

Deposition of Robert Catalano taken April

14, 1975

Deposition of Peter Mullaney taken April

14, 1975

Clerk’s Certificate

13a

Second Amended Complaint

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Southern D istrict of New Y ork

74 Civ. 2010 RLC

Class A ction-

Organization of F oster F amilies for E quality and Re

form; Madeline Smith , on her own behalf and as next

friend of Danielle and E ric Gandy; and R alph and

Christiane Goldberg, on their own behalf and as next

friend of R afael Serrano, on behalf of themselves and

all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

— against—

James Dumpson, individually and as Administrator of the

New Y ork City H uman Resources A dministration;

E lizabeth B eine, individually and as Director of the

New Y ork City Bureau of Child W elfare, and as Act

ing Assistant Administrator of New Y ork City Special

Services for Children; A dolin Dall, individually and

as Director of the D ivision of Inter-A gency R elation

ships of the B ureau of Child W elfare; and James P.

O’Neill, individually and as Executive Director of

Catholic Guardian Society of New Y ork,

Defendants.

■4 >

14a

1. This is a class action for declaratory and injunctive

relief pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and 28 U.S.C. $§ 2201

and 2202 to protect and redress rights guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment. In this action, plaintiffs and

members of their class seek a declaration that New York

Social Services Law §§ 383 (2) and 400 on their face and

as applied violate the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment and an injunction

against their continued application, and a declaration that

the procedures for removing children from foster homes

as contained in 18 NYCRR 450.14, and as applied by de

fendants, violate the rights of plaintiffs and members of

their class to due process of law and equal protection of

the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, and

an injunction against the removal of children from the

homes of foster parents in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Second Amended Complaint

J urisdiction

2. This being an action to redress the deprivation under

color of -state law of rights, privileges and immunities

guaranteed by the United States Constitution, jurisdiction

is conferred on this court by 28 U.S.C. § 1343 (3) and (4).

T hree-judge Court

3. A three-judge court should be convened in accord

ance with 28 U.S.C. $ 2281 et seq. since plaintiffs seek to

enjoin defendants from acting in accordance with New

York Social Services Law §-§ 383 (2) and 400, statutes of

state-wide application, and 18 NYCRR 450.14, a regulation

of state-wide application, on the ground that said statutes

15a

and regulation are unconstitutionally vague on their face

and, both on their face and as applied, deny plaintiffs and

members of their class due process and equal protection

of the law in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Class A ction Allegations

4. Plaintiffs bring this action as a class action under

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 23(a), 23(b) (1) (A ),

23(b) (1) (B ), and 23(b) (2). Defendants have acted on

grounds generally applicable to the class, thereby making

injunctive and declaratory relief appropriate with respect

to the class.

5. There are four sub-classes represented by plaintiffs.

All of them involve foster families which have been to

gether for more than one continuous year, and which are

in jeopardy of being separated and the children moved

elsewhere in violation of their rights to equal protection

and due process of law, as guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

6. Plaintiff Madeline Smith represents the sub-class of

foster parents who are under the supervision of authorized

child-care agencies. Plaintiffs Ralph and Christiane Gold

berg represent the sub-class of foster parents who are

under the direct supervision of a public welfare district.

Plaintiff Organization of Foster Families for Equality and

Reform represents both of these sub-classes, which on in

formation and belief contain well over a thousand mem

bers, viz., all those foster parents who have had continuous

care and custody of foster children for more than one

year, either through an authorized agency or under the

direct supervision of a public welfare district.

Second Amended Complaint

16a

7. Plaintiffs Danielle and Eric Gandy, who appear in

this action by their foster mother and next friend Madeline

Smith, represent the sub-class of foster children under the

supervision of authorized child-care agencies, and who

have lived in one foster home for more than one year.

Plaintiff Rafael Serrano who appears in this action by his

foster parents and next friends Ralph and Christiane

Goldberg, represents the sub-class of foster children under

the direct supervision of a public welfare district. Both

of the sub-classes contain, on information and belief, well

over a thousand members, viz., all those foster children

who have lived in one foster home for more than one year,

either under the supervision of an authorized agency or

under the direct supervision of a public welfare district.

8. The number of individuals in each of these sub

classes is too numerous to make joinder practicable.

9. Plaintiffs will fairly and adequately represent the

interest of the class in the present action. All plaintiffs

are represented by attorneys associated with the New

York Civil Liberties Union, a privately funded organiza

tion, with resources and experience in the area of consti

tutional litigation.

10. Plaintiffs’ claims are typical of the claims of the

class. Plaintiffs Madeline Smith, Ralph and Christiane

Goldberg, and O.F.F.E.R. represent all those foster par

ents who have taken homeless, dependent children who

are in the custody of public welfare officials, either di

rectly or through authorized agencies, into* their homes,

who have brought up these children for years, and who

are in jeopardy of having these children summarily re

moved pursuant to statutes and a state regulation, New

Second Amended Complaint

17a

York Social Services Law §§ 383 (2) and 400, and 18

NYCRR 450.14, which violate their constitutional rights

to due process and equal protection of the law. Plain

tiffs Eric and Danielle Gandy and Rafael Serrano repre

sent all those dependent New York children who are the

legal responsibility of public welfare officials, either di

rectly or through authorized agencies, who have been

placed in stable, loving foster homes, and who are in

jeopardy of losing what has become their family through

the arbitrary, standardless procedures authorized by New

York Social Services Law §§ 383 (2) and 400, and 18

NYCRR 450.14, in violation of their constitutional rights

to due process and equal protection of the law.

11. There are questions of law and fact common to all

members of class in this action, in that defendants Dump-

son, Beine, Dali and O’Neill have the statutory authority

to and do remove foster children from the homes of fos

ter parents in violation of both of these groups’ rights to

due process and equal protection of the law as guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment.

12. The questions of law and fact common to the mem

bers of the class predominate over any questions affect

ing only individual members and an adjudication with

regard to plaintiffs’ constitutional claims would as a prac

tical matter be dispositive with regard to other members

of the class. A class action is superior to other available

methods for the fair and efficient adjudication of the con

troversy. Plaintiffs know of no interest of members of

the class in individually controlling separate actions.

Plaintiffs know of no difficulties likely to be encountered

in the management of a class action.

Second Amended Complaint

18a

Second Amended Complaint

P laintiffs

13. The Organization of Foster Families for Equality

and Reform is a downstate New York organization of

foster parents with a membership of approximately 250

persons. It is a member of the New York state-wide

coalition of parent organizations which includes over 2,000

persons. O.F.F.E.R. was organized to provide forums for

foster parents to discuss common problems with respect

to their relationship with the public officials and child

care agency representatives under whose authorization

they receive foster childem, and to gather and present

information with regard to foster parents’ rights.

14. Plaintiff Madeline Smith is a 53-year-old widow

who lives in East Elmhurst, New York. She became an

approved foster parent under the supervision of Catholic

Guardian Society of New York in 1969. On February 1,

1970, she took Eric and Danielle Gandy into her home as

foster children, where they have lived and been cared for

continually for the past four years.

15. Plaintiffs Eric Gandy, who is eight years old, and

Danielle Gandy, who is six years old, appear in this

action by their foster mother and next friend, Madeline

Smith. Both Danielle and Eric were placed in the cus

tody of the Commissioner of Social Services on April 26,

1968. They were placed in Mrs. Smith’s home on February

1, 1970, by Catholic Guardian Society of New York, and

have not seen their natural mother at least since that

date. Both Danielle and Eric call Mrs. Smith “ Mommy.”

16. Plaintiffs Ralph and Christiane Goldberg own their

own home in Brooklyn. Mr. Goldberg is a hospital ad

19a

ministrator. As authorized foster parents directly under

the supervision of the Bureau of Child Welfare, they took

Rafael Serrano into their home on July 11, 1969, where

he has lived as a member of their family for the past

five years.

17. Plaintiff Rafael Serrano, who is 11 years old, ap

pears in this action by his foster parents and next

friends, Ralph and Christiane Goldberg. On information

and belief, he has been in the custody of the Commis

sioner of Social Services since 1968, when his parents

signed a voluntary consent for placement after an abuse

report had been filed against him. He has lived with Mr.

and Mrs. Goldberg longer than he has lived any place

else in his life.

18. Defendant James Dumpson is the duly appointed

Administrator of the Human Resources Administration of

the City of New York and as such is responsible for the

administration of the New York City welfare district.

New York Social Services Law § 395 et seq. specifically

mandates that the official in charge of the local public

welfare district is responsible for all children within his

district who are in need of care and assistance.

19. Defendant Elizabeth Beine is an agent of defend

ant Dumpson and was at the time this action was filed

Acting Assistant Administrator of Special Services for

Children, an agency within the New York City Human

Resources Administration responsible for providing serv

ices for all children in need of care in New York. She

is also Director of the Bureau of Child Welfare, a divi

sion within Special Services for Children.

20. Defendant Adolin Dali is an agent of defendants

Dumpson and Beine and is Director of the Division of

Second Amended Complaint

20a

Inter-Agency Relationships of the Bureau of Child Wel

fare which, upon information and belief, is directly re

sponsible for the supervision of all authorized child-care

agencies which serve New York City children.

21. Defendant James P. O’Neill is Executive Director

of Catholic Guardian Society of New York, a child-care

agency authorized by the New York State Board of Social

Welfare to provide services for children and to receive

children for placement from the public welfare district

administrator. Upon information and belief, Catholic

Guardian Society of New York receives over 90 percent

of its funding from the City of New York, is subject to

state and city regulations and supervision, and acts under

color of state law.

Second Amended Complaint

Statement of Claim

Mrs. Smith and Eric and Danielle Gandy

22. Upon information and belief, in 1969, plaintiff

Madeline Smith became approved as a foster parent by

the Catholic Guardian Society of New York, a child-care

agency operated by defendant O’Neill under the super

vision of defendant Dumpson and liis agents.

23. At that time, upon information and belief, Mrs.

Smith told the Catholic Guardian Society social worker,

Mrs. Armstrong, that she wanted foster children who had

no family at all, because she would like to adopt them.

Mrs. Smith told Mrs. Armstrong that she had arthritis,

which made her unable to work, but she said, upon infor

mation and belief, that she was capable of caring for

children and was anxious to do so because her own daugh

ter had died.

21a

24. Upon information and belief, Mrs. Armstrong told

Mrs. Smith that Catholic Guardian Society had two chil

dren they would like to place with her, Eric and Danielle

Gandy. Upon information and belief, Mrs. Armstrong

told her that only Danielle was adoptable because Eric

was retarded, but that the agency was anxious to keep the

children together because they were the only family each

of them had. Mrs. Smith said she would take both children.

25. On February 1, 1970, Eric and Danielle Gandy went

to live with Mrs. Smith, where they have lived ever since.

26. Upon information and belief, Eric and Danielle

Gandy are legally free for adoption. Upon information

and belief, Danielle has never seen her natural mother,

Eric does not remember her, and both of them regard

Mrs. Smith as their mother.

27. Upon information and belief, Mrs. Smith has re

peatedly made known her desire to adopt the children to

workers at the Catholic Guardian Society.

28. Upon information and belief, defendant O’Neill and

his agents have arbitrarily decided to remove Eric and

Danielle Gandy from Mrs. Smith’s home. On information

and belief, defendants Dumpson, Beine, Dali and their

agents have approved defendant O’Neill’s decision to re

move Eric and Danielle Gandy from Mrs. Smith’s home.

29. Upon information and belief, Mrs. Smith has been

notified of this decision, but has not received any notice

of the reasons upon which the decision has been based.

Nor has Mrs. Smith been given an opportunity to chal

lenge these reasons in a hearing.

Second Amended Complaint

22a

30. Upon information and belief, Mrs. Dillon, an em

ployee of Catholic Guardian Society and an agent of de

fendant O’Neill’s, brought Mrs. Smith a letter dated March

29, 1974, a copy of which is annexed hereto as Exhibit

A, notifying her that Eric and Danielle would be removed

from her home on April 24, 1974. The only reason for

the pending removal stated in the letter is: “ To continue

to plan for Eric and Danielle, it is now in their best inter

ests to leave your home on or about April 24.”

31. Upon information and belief, the letter given to

Mrs. Smith is a printed form letter routinely used by

defendant O’Neill as the only notice to foster parents of

the pending removal of foster children from their foster

homes. The only blanks to be filled in on the form are

the names of the foster parents and the children, the date

of the letter and the date on which the children are to

be removed. The statement quoted in paragraph 30 is

part of the printed form, Avith the exception of blanks

for the children’s names and the removal date.

32. Upon information and belief, the only opportunity

for a hearing that has -been afforded to Mrs. Smith was

contained in the folloAving statement in the form letter:

“ In the event that you wish to waive the ten days’ notice

usually given to a foster parent before removing a child

just check this box, sign below, and return this letter to

me. However, if you have have serious questions about

this plan, it is your right to request a conference with

a public official. The Public Official will review Avith you

the reasons for the decision; and you can give your rea

sons for requesting the conference.”

33. Upon information and belief, the conference re

ferred to in the letter does not satisfy the most minimal

Second Amended Complaint

23a

due process rights, in that there are no written standards

or guidelines concerning the conference itself, there are

no written standards or guidelines by which to judge the

appropriateness of the agency’s removal decision, the fos

ter parent is not entiled to a written statement specify

ing the basis for the agency’s decision, the foster parent

is not entitled to confront and question those persons sup

plying the facts, if any, upon which the agency decision

has been made, and the foster parent is not entitled to

bring her own witnesses.

34. Upon information and belief, Mrs. Dillon brought

Mrs. Smith the letter, told her to check a box and sign

the letter, and told her that she had not waived any rights

to a review of the agency’s decision to remove the chil

dren. Upon information and belief, Mrs. Smith was de

nied even this legally insufficient conference since her al

leged waiver of the conference was an uninformed waiver.

35. Upon information and belief, defendants O’Neill and

his agents, and defendants Dumpson, Beine, and Dali have

decided to and plan to remove Eric and Danielle Gandy

permanently from Mrs. Smith’s home on May 10, 1974.

36. Upon information and belief, the procedure followed

by defendant O’Neill and his agents, with regard to noti

fication to Mrs. Smith of the planned removal of her foster

children is regularly followed by defendant O’Neill’s

agents with regard to other foster parents and children

over whom they have control.

37. Upon information and belief, this procedure is fol

lowed and carried out with the full knowledge and co

operation of and acting in concert with and under the au

Second Amended Complaint

24a

thority of defendants Dumpson, Beine, and Dali and their

agents.

38. All actions of defendant O’Neill and his agents al

leged in this complaint are and have been carried out un

der color of state law. Catholic Guardian Society of New

York, of which defendant O’Neill is Executive Director,

is a child-care agency authorized, approved and regulated

by New York state law, and supervised by state and city

public officials. Upon information and belief, it receives

over 90 percent of its funding from the City of New York,

and the acts as an agent of the city with regard to those

children including Eric and Danielle Gandy, whom the city

has referred to Catholic Guardian Society for placement.

Upon information and belief, a substantial portion of the

money Catholic Guardian Society receives from the City

of New York is reimbursed to the city from the federal

government as Aid to Families of Dependent Children pay

ments under Title IY-A of the Social Security Act.

39. Upon information and belief, this procedure, or pro

cedures substantially similar, are followed and carried out

by other child-care agencies under the control and super

vision of defendants Dumpson, Beine, and Dali and their

agents with the full knowledge and cooperation of said

defendants.

40. Upon information and belief, notification of the

availability of an administrative conference, held pursu

ant to 18 NYCRR 450.14, is frequently carried out by de

fendant O’Neill and waivers obtained, without said waivers

being informed waivers, and without the notified foster

parents being fully informed of and aware of their rights.

Second Amended Complaint

25a

41. Upon information and belief, notification of the

availability of an administrative conference held pursuant

to 18 NYCRR 450.14 is made in a substantially similar

way by other child-care agencies under the control and

supervision o f defendants Dumpson, Beine, and Dali and

their agents, and with their full knowledge and coopera

tion.

Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg and Rafael Serrano

42. Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg are authorized foster par

ents under the direct supervision of defendants Dumpson

and Beine. They took Rafael Serrano into their home on

July 11, 1969, when he was six years old.

43. On information and belief, Rafael had lived in sev

eral other homes before he came to live with Mr. and Mrs.

Goldberg in 1969, and had been severely abused by his

parents during the time he lived with them.

44. Upon information and belief, when Rafael was

placed with Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg by the Bureau of

Child Welfare in 1969, the worker told them that he was

brain damaged, retarded and hyperactive. Upon infor

mation and belief, they were told that if they didn’t take

the six-year-old boy at that time, the Bureau of Child

Welfare would place him in a state hospital.

45. Upon information and belief, when Rafael first came

to live with Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg, he was a very dis

turbed, unhappy child who threatened to tear apart their

home and their own three-year-old daughter. A doctor

who saw Rafael at that time described him as being para

lyzed by anxiety.

Second Amended Complaint

26a

46. Upon information and belief, the Bureau of Child

Welfare worker told Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg shortly after

they took Rafael that they should not feel bad about re

turning him to the agency since his record showed an

inability to adjust to a family setting. Upon information

and belief, the agency worker said the alternative to the

Goldbergs’ home for Rafael would be an institution.

47. Rafael has lived with Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg and

their daughter for the last five years as a member of their

family. He is now doing well in school, and has made

friends in their community.

48. Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg have been commended re

peatedly by employees and agents of defendants Dumpson

and Beine for doing an admirable job in raising Rafael.

49. Rafael’s parents have not -seen the boy in well over

a year and, upon information and belief, have made no

attempts to have their son returned to them. Upon in

formation and belief, all of their six children are in foster

care and the Bureau of Child Welfare has recommended

adoption for two of them.

50. Upon information and belief, the Bureau of Child

Welfare worker in charge of Rafael’s case, Robert Tobing,

has recommended that Rafael be taken from his home

with Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg within the next few months

and given to an aunt whom Rafael has visited only once.

51. Upon information and belief, the aunt to whom the

agency plans to give Rafael does not want to take him

from the Goldbergs’ home and does not want to bring him

u p .

Second Amended Complaint

27a

52. Upon information and belief, Mr. and Mrs. Gold

berg have not been notified directly of the Bureau of Child

Welfare’s decision to remove Rafael from their home, nor

do they know any reason why such an action should be

taken.

53. Upon information and belief, the Bureau of Child

Welfare is working toward removing Rafael from his

home with Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg, by attempting to set

up visits between Rafael and his aunt so they can get to

know each other before Rafael is to be moved. Such

visits in the context of a planned move are subjecting

Rafael and Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg to severe anxiety and

uncertainty.

54. Upon information and belief, these actions of de

fendants Dumpson, Beine and their agents, to begin to

effectuate a plan to remove a child from a home he has

made with his foster parents, without adequate notice of

the planned removal and without stating the reasons for

such a removal, are carried out in a substantially similar

way with regard to other foster parents and children un

der the direct supervision and control of the Bureau of

Child Welfare, and with the full knowledge and coopera

tion of defendants Dumpson and Beine.

55. Under 18 NYCRR 450.14, Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg

are only entitled to notification that Rafael is to be re

moved from their home 10 days prior to the date of the

actual removal.

56. When they are thus notified, they have a right to

request a conference with an agent and employee of the

Bureau of Child Welfare, prior to the removal, pursuant

to 18 NYCRR 450.14.

Second Amended Complaint

28a

57. Upon information and belief, the costs of the foster

care program under the direct supervision of the Bureau

of Child Welfare, in which Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg are

authorized foster parents, are substantially reimbursed by

the federal government as Aid to Families of Dependent

Children payments under Title IY-A of the Social Security

Act.

Second Amended Complaint

New York City Revised Procedure

58. Subsequent to the filing of this action, defendant

Dumpson and his agents promulgated a document entitled

“ Human [Resources Administration Inter-Office Memoran

dum, Subject: Administrative Removal of Foster Chil

dren,” dated June 25, 1974, setting forth procedural

changes with regard to the removal of New York City

foster children from foster homes under certain circum

stances.

Causes of A ction

59. The notification procedure described above in para

graphs 29 through 41 violates the right of plaintiff Smith

and foster parents who are members of her class not to

be deprived without due process of law of the fundamental

right to establish a home and bring up children and to

enjoy those privileges long recognized as essential to the

pursuit of happiness and liberty encompassed within the

Fourteenth Amendment.

60. The notification procedure contained within the New

York City procedure referred to in paragraph 58 above

violates the rights of plaintiffs Smith and Ralph and

29a

Christiane Coldberg and members of their class not to be

deprived without due process of law of the fundamental

right to establish a home and bring up children and to

enjoy those privileges long recognized as essential to the

pursuit of happiness and liberty encompassed w ithin the

Fourteenth Amendment.

61. The plan and the attempts by agents of defendants

Dumpson and Beine to begin implementation of their de

cision to remove Rafael Serrano from his home with Mr.

and Mrs. G-oldberg, prior to notification that the child is

to be removed, violates the right of plaintiffs Ralph and

Christiane Goldberg not to be deprived without due proc

ess of law of the fundamental right to establish a home

and bring up children and to enjoy those privileges long

recognized as essential to the pursuit of happiness and

liberty encompassed within the Fourteenth Amendment.

62. New York Social Services Law $ 383 (2), which

authorizes defendant O’Neill and his agents, with the

knowledge, authorization and encouragement of defend

ants Dumpson, Beine and Dali, to remove Eric and

Danielle Candy from Mrs. Smith’s home and which au

thorizes defendants Dumpson and his agents to remove

Rafael Serrano from Ralph and Christiane Coldberg’s

home provides:

“ The custody of a child placed out or boarded

out and not legally adopted or for whom legal

guardianship has not been granted shall be vested

during his minority, or until discharged by such

authorized agency from its care and supervision, in

the authorized agency placing out or boarding out

such child and any such authorized agency may in

Second Amended Complaint

30a

its discretion remove such child from the home

where placed or boarded.”

63. Said statute is unconstitutionally vague and fails

to set standards in violation of the rights of plaintiffs

Smith and Ralph and Christiane Goldberg and foster par

ent members of their class not to be deprived of their

fundamental rights to establish a home, bring up children

and to enjoy those privileges long recognized as essential

to the pursuit of happiness and liberty encompassed within

the due process guarantee of the Fourteenth A m endment.

64. Said statute is unconstitutionally vague and fails to

set standards in violation of the rights of plaintiffs Eric

and Danielle Gandy and Rafael Serrano and other foster

children in their class to those fundamental rights and

privileges long recognized as assential to the pursuit of

happiness and liberty encompassed within the due process

guarantee of the Fourteenth Amendment.

65. The statute, New York Social Services Law § 400,

which authorized defendants Dumpson and Beine and their

agents to remove Rafael Serrano from the home of Ralph

and Christiane Goldberg, provides:

“ When any child shall have been placed in an in

stitution or in a family home by a commissioner of

public welfare or a city public welfare officer, the

commissioner or city public welfare officer may re

move such child from such institution or family

heme and make such disposition of such child as is

provided by law.

“Any person aggrieved by such decision of the

commissioner of public welfare of city welfare of

Second Amended Complaint

31a

ficer may appeal to the department, which upon

receipt of the appeal shall review the case, shall

give the person making the appeal an opportunity

for a fair hearing thereon and within thirty days

render its decision. The department may also, on

its own motions, review any such decision made

by the public welfare official. The department may

make such additional investigation as it may deem

necessary. All decisions of the department shall

be binding upon the public welfare district involved

and shall be complied with by the public welfare

officials thereof.”

66. Said statute is unconstitutionally vague and fails

to set standards in violation of the rights of plaintiffs

Ralph and Christiane Goldberg and foster parent mem

bers of their class not to be deprived of their funda

mental rights to establish a home, bring up children and

to enjoy those privileges long recognized as essential to

the pursuit of happiness and liberty encompassed within

the due process guarantee of the Fourteenth Amendment.

67. Said statute is unconstitutionally vague and fails

to set standards in violation of the rights of plaintiff

Rafael Serrano and members of his class to those funda

mental rights and privileges long recognized as essential

to the pursuit of happiness and liberty encompassed with

in the due proceses guarantee of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

68. The facial constitutional infirmity of New York

Social Services Law §§ 383(a) and 400 is further com

pounded by the absence of any state regulations which

set standards by which these statutes are to be applied,

Second Amended Complaint

32a

in violation of the due process rights of plaintiffs and

members of their class.

69. The facial constitutional infirmity of Social Services

Law § 383 (2) is further compounded by the fact that

this unfettered discretion, which is exercised in the ab

sence of any state regulations setting standards, is given

to employees and agents of voluntary child-care agencies,

who act under color of state law but are not under the

control of public officials, in violation of the right of plain

tiffs Madeline Smith and Eric and Danielle Gandy and

members of their class to due process and equal protec

tion of the law.

70. New York Social Services Law § 400, which pro

vides a foster parent aggrieved by a decision to remove

a foster child from his or her home with the right to a

fair hearing subsequent to the removal of the child, ex

tends only to foster parents under the direct supervision

of a public welfare official. On its face, this statute de

prives plaintiffs Madeline Smith and Eric and Danielle

Gandy and members of their class, who are foster parents

and foster children under the direct supervision of a vol

untary child-care agency, of equal protection of the law

in violation of their constitutional rights.

71. On its face, 18 NYCRR 450.14(a) (b) and (c) in

sofar as it provides an administrative conference without

mandating even minimal due process safeguards and

standards, prior to the removal of foster children from

foster homes, violates the constitutional rights of plain

tiffs Madeline Smith and Eric and Danielle Gandy, and

Ralph and Christiane Goldberg, and members of their

Second Amended Complaint

33a

class not to be deprived of liberty or fundamental rights

without due process of law.

72. As applied by defendants, 18 NYCRR 450.14 (a)

(b) and (c) insofar as it provides an administrative con

ference prior to the removal of foster children from fos

ter homes without constitutionally adequate due process

safeguards, violates the constitutional rights of plain

tiffs and members of their class not to be deprived of

liberty or fundamental rights without due process of law.

73. The internal procedure enacted by defendants

Dumpson and his agents, dated June 25, 1974, and re

ferred to in paragraph 58 above, is unconstitutionally

vague, fails to set standards, and does not provide con

stitutionally adequate due process safeguards prior to

the removal of foster children from foster homes, in vio

lation of the rights of plaintiffs and members of their

class not to be deprived of liberty or fundamental rights

without due process of law.

74. New York Social Services Law § 400 and 18 NY

CRR 450.14(c) provide that a foster family aggrieved by

a decision to remove a child from its home may request

a fair hearing to review the decision subsequent to the

time the child is actually removed from the home.

75. The absence of a fair hearing prior to the termina

tion of participation in a program funded by the federal

government, under its Aid to Families of Dependent Chil

dren, while other recipients and beneficiaries of federal

funds under Aid to Families of Dependent Children are

entitled to a fair hearing prior to such a termination,

under 18 NYCRR 358.8, violates the rights of plaintiff

Second Amended Complaint

34a

foster families and foster children to equal protection of

the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

76. The absence of any hearing procedure which satis

fies due process standards prior to the removal of foster

children from homes in which they have lived for more

than a year violates the rights of Eric and Danielle

Gandy and Rafael Serrano and members of their class

not to be subjected to irreparable harm and denied lib

erty and fundamental rights without due process of law

as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

77. The absence of any hearing procedure which satis

fies due process standards prior to the removal of foster

children from homes in which they have lived for more

than a year violates the rights of Madeline Smith and

Ralph and Christiane Goldberg and members of their

class not to be subjected to irreparable harm and denied

liberty and fundamental rights without due process of

law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Second Amended Complaint

P rayer eor R elief

W herefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court:

(a) Grant a temporary restraining order restraining

defendants O’Neill, Dumpson, Beine and Dali from re

moving Eric and Danielle Gandy from the home of Mrs.

Madeline Smith;

(b) Convene a three-judge court pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§$ 2281 and 2284;

35a

(c) Enter a declaratory judgment that New York Social

Services Law § 383(2) is unconstitutional on its face and

as applied as a violation of the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment;

(d) Enter a declaratory judgment that New York

Social Services Law § 400 is unconstitutional on its face

and as applied as a violation of the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment;

(e) Enter a declaratory judgment that the practice of

defendants Dump son and Beine and their agents of fail

ing to provide a due process hearing prior to the re

moval of children from foster homes in which they have

lived continuously for over one year violates the rights

of foster parents and children to due process and equal

protection of the law;

(f) Enter a declaratory judgment that 18 NYCRR

450.14 is unconstitutional on its face and as applied as a

violation of the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment;

(g) Enter a declaratory judgment that the New York

City Human Resources Administration internal procedure

for removing foster children from foster homes is uncon

stitutional on its face and as applied as a violation of

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment;

(h) Preliminarily and permanently enjoining defend

ants from removing foster children from foster homes in

which they have lived continuously for a period of over

one year pursuant to New York Social Services Law § 383

( 2 ) ;

Second Amended Complaint

36a

(i) Preliminarily and permanently enjoin defendants

from removing foster children from foster homes in which

they have lived continuously for a period of over one

year pursuant to 18 NYCRR 450.14;

(j) Preliminarily and permanently enjoin defendants

from removing foster children from foster homes in which

they have lived continuously for a period of over one

year pursuant to the New York City Human Resources

Administration internal procedure;

(k) Preliminarily and permanently enjoin defendants

from removing foster children from foster homes in which

they have lived continuously for a period of over one

year without the due process safeguards of adequate and

specific notice and a prior hearing which satisfy the due

process requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment;

(l) Such other and further relief as this Court deems

just and proper.

Second Amended Complaint

Respectfully submitted,

Marcia R obinson L owry

Children’s Rights Project

New York Civil Liberties Union

84 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10011

(212) 924-7800

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

37a

Exhibit A

CATHOLIC GUARDIAN SOCIETY

1011 F irst A venue

New Y ork, New Y ork 10022

Telephone: 371-1000

September 21, 1973

Telephone # 478-0945

Date: 3/29/74

Re: Eric & Danielle Gandy

Mrs. Madeline Smith

23-15 101st Street

East Elmhurst, N.Y.

Dear Mrs. Smith

The care and attention yon have given to the foster

child(ren) in your home is greatly appreciated. This has

been a service not only to the child, but to your com

munity.

To continue to plan for Eric & Danielle, it is now in

(their) best interests to leave your home on or about

April 24. Should you desire any additional information,

please feel free to contact me.

In the event that you wish to waive the ten day’s notice

usually given to a foster parent before removing a child

just check this box [ / ] , sign below, and return this letter

to me.

However, if you have serious questions about this plan,

it is your right to request a conference with a public offi-

38a

Exhibit A

cial. The Public Official will review with you the reasons

for the decision; and you can give your reasons for re

questing the conference. I f you wish, you can bring a

representative to the conference. Please let me know

immediately if you wish me to arrange such a conference

for you and whether you plan to bring a representative.

Otherwise, I shall assume you are in agreement that the

plan should be carried out.

Once again, may we thank you for your service to the

New York City’s children.

Sincerely yours,

Jane-Ellen D illon

Caseworker

(ILLEGIBLE)

(ILLEGIBLE)

Madeline Smith

39a

Order Convening Three Judge Court

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Southern D istrict of New Y ork

74 Civ. 2010

Organization of F oster F amilies for E quality and

R eform, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

—against—

James Dumpson, et al.,

Defendants.

------------------ »----------------------

This cause having come on to he heard on plaintiffs’

motion pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 2281 and 2284 for the

convening of a three-judge court, plaintiffs’ motion to join

parties pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 21, plaintiffs’ motion

for a temporary restraining order pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 2284(3), and the motion of Naomi Rodriguez et al. to

intervene in this action pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a)

and (b), and papers having been submitted and a hearing

having been held on all the motions listed above on Au

gust 5, 1974, before the Hon. Robert L. Carter, it is

Ordered that plaintiffs’ motion for the convening o f a

three-judge court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 2281 and 2284

be and hereby is granted, and it is further

40a

Ordered that plaintiffs’ motion to join Dorothy and

George Lhotan, and Cheryl, Patricia, Cynthia and Cath-

leen Wallace as parties plaintiff, and Joseph D’Elia Com

missioner of the Nassau County Department of Social

Services, Bernard Shapiro, Executive Director of the New

York State Board of Social Welfare, and Abe Lavine,

Commissioner of the New York State Department of So

cial Services as parties defendant be and hereby is

granted, and further

The court having made a finding that irreparable injury

will result to Cheryl, Patricia, Cynthia and Cathleen Wal

lace through the disruption in their lives caused by their

removal from the home of Dorothy and George Lhotan,

and in order to maintain the status quo with regard to

these children and their foster parents, it is further

Ordered that defendant Joseph D’Elia be restrained pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. § 2284(3) from removing Cheryl, Patri

cia, Cynthia and Cathleen Wallace from the home of

Dorothy and George Lhotan or in any way interfering

with or interrupting their stay with these foster parents

pending a hearing before the three-judge court, and a

determination of plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary in

junction and it is further

Ordered that the motion of Naomi Rodriguez, Rosa

Diaz, Mary Robins and Dorothy Nelson Shabazz to inter

vene as defendants in this action pursuant to Fed. R.

Civ. P. 24(a) and (b) is granted solely for the purposes

of litigating the issues and causes of action contained in

Plaintiffs’ Second Amended Complaint, and it is further

Ordered that the cross claims of Naomi Rodriguez, Rosa

Diaz, Mary Robins, and Dorothy Nelson Shabazz asserted

Order Convening Three Judge Court

41a

in Intervenor Defendants’ Answer and Cross Claim are

stricken and the intervenor defendants’ cross claims are

disallowed.

Dated: New York, New York

August 15, 1974

Order Convening Three Judge Court

R obert L. Carter

United States District Judge

A True Copy

R aymond F B urghardt,

Clerk

B y : Gr. Harbison

Deputy Clerk

42a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Southern District oe New Y ork

74 Crv 2010 RLC

Answer of New York State Defendants

-----------------------«----------------------

Organization of F oster F amilies for E quality and

R eform; Madeline Smith, on her own behalf and as

next friend of Danielle and E ric Candy; and R alph

and Christiane Goldberg, on their own behalf and as next

friend or R afael Serrano, on behalf o f themselves and

all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

—against—

James Dumpson, individually and as Administrator of

the New Y ork City H uman R esources A dministration ;

E lizabeth Beine, individually and as Director of the

New Y ork City B ureau of Child W elfare, and as

Acting Assistant Administrator of New Y ork City

Special Services for Children; A dolin Dall, individu

ally and as Director of the D ivision of I nter-A gency

R elationships of the B ureau of Child W elfare; and

James P. O’Neill, individually and as Executive Direc

tor of Catholic Guardian Society of New Y ork,

Defendants.

Defendants Bernard Shapiro, individually and in his

capacity as Executive Director of the New York State

43a

Board of Social Welfare and Abe Lavine, individually

and in his capacity as Commissioner of the New York

State Department of Social Services, by their attorney,

Louis J. Lefkowitz, Attorney General of the State of

New York, for their answer to the second amended com

plaint herein, on information and belief, respectfully:

First: Deny each and every allegation contained in

paragraphs 2, 4, 5, 59, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70,

71, 72, 73, 75, 76 and 77 of plaintiffs’ second amended

complaint.

Second: Admits each and every allegation contained in

paragraphs 3, 18, 19, 20, 21, 31, 55, 56, 57, 58, 65 and 74

of plaintiffs’ second amended complaint.

Third: Deny knowledge or information sufficient to

form a belief as to the truth of each and every allega

tion contained in paragraphs 1, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14,

16, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 34, 36, 37, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43,

44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 and 57 of plain

tiffs’ second amended complaint.

Fourth: Deny knowledge or information sufficient to

form a belief as to the truth of each and every allega

tion contained in paragraph 7 of plaintiffs’ second

amended complaint, except denies so much of the allega

tions in said complaint as alleges or implies that Danielle

and Eric Gandy, may be permitted to or properly ap

pear by and be represented by their “ foster mother and

next friend Madeline Smith, and further deny so much

of the allegations in said paragraph as alleges or im

plies that plaintiff Rafael Serrano may be permitted to

or properly appears by Ms foster parents and next

friends Ralph and Christians Goldberg.”

Answer of New York State Defendants

44a

Fifth : Deny knowledge or information sufficient to

form a belief as to the truth of each and every allega

tion contained in paragraph 15 of plaintiffs’ second

amended complaint, except deny so much of the allega

tions in said paragraph as alleges or implies that plain

tiffs Eric and Danielle Gandy may properly appear or

be permitted to appear in this action by their foster

mother and next friend, Madeline Smith.

Sixth: Deny knowledge or information sufficient to form

a belief as to the truth of each and every allegation con

tained in paragraph 17 of plaintiffs’ second amended

complaint, except deny so much of the allegations con

tained in said paragraph as alleges or implies that plain

tiff Eafael Serrano1 may properly appear or be permitted

to appear in this action by their foster parents and next

friends Ralph and Christiane Goldberg.

Seventh: Denies knowledge or information sufficient

to form a belief as to the truth of each and every allega

tion contained in paragraph 29 of plaintiffs’ second

amended complaint, except denies so much of the allega

tions in said paragraph as alleges that plaintiff Smith

has been denied an opportunity to challenge the basis for

the decision:

Eighth: Admit each and every allegation contained in

paragraph 30 of plaintiffs’ second amended complaint,

except deny knowledge or information sufficient to form

a belief as to the truth of so much of the allegations in

said paragraph as alleges that letter dated March 29,

1974 was delivered by a Mrs. Dillon and that Mrs. Dillon

is an employee of the Catholic Guardian Society and an

agent of defendant O’Neill, and each such allegation.

Answer of New York State Defendants

45a

Ninth: Denies so much of paragraph 32 of plaintiffs’

second amended complaint as alleges or implies that the

only mode of review and hearing is contained in the form

paragraph of the conference with the public official, but

admits that the form letter received by Mrs. Smith does

contain the statement quoted in said paragraph.

Tenth: Deny so much of the allegations in paragraph

33 of plaintiffs’ second amended complaint as alleges or

implies that plaintiff has a right to due process prior to

the removal of the foster child, that due process in any

event mandates the use of a written statement specifying

the basis for the agency’s decision, or the right to con

front and cross-examine witnesses or the right to present

her own witnesses, or the use of written guidelines. Fur

ther deny so much of the allegations in said paragraph

as alleges that there are no written standards or guide

lines concerning the conference itself.

Eleventh: Deny knowledge or information sufficient to

form a belief as to the truth of each and every allega

tion contained in paragraph 38 of plaintiffs’ second

amended complaint, except deny that defendant O’Neill

and his agent are acting under color of state law.

Answer of New York State Defendants

As AND FOR A F lR S T SEPARATE AND COMPLETE

A f f i r m a t i v e D e f e n s e :

Twelfth: Under state law, children placed with agencies

for placement in foster care families, remain in the cus

tody of the agency so placing them, and are merely placed

into these homes and with the parents as, in effect em

ployees of the agency, as caretakers.

46a

Thirteenth: At no time prior to the completion of

adoption proceedings do the children so placed become

permanent members of the foster family. At all times

prior to the completion of adoption proceedings, if any,

the placement agency is responsible for the health, safety

and well-being of the children, and continues to maintain

supervision over the foster families and custody of the

children.

Fourteenth: A t no time prior to the onset of formal

adoption proceedings is it contemplated that the foster

parent relationship is anything more than a temporary

caretaker relationship.

As and for a Second Separate and Complete

A ffirmative Defense:

Fifteenth: Upon information and belief, in none of

the situations involving any of the named plaintiffs does

the removal of the children from the homes of the foster

parents, reflect adversely upon the quality of the care

provided by the foster parents or foreclose them from, in

the future, again being foster parents.

Sixteenth: Upon information and belief, the foster par

ents are in no way deprived of either the liberty to en

gage in familiar relationships or is there any informa

tion of the freedom to raise their children in a manner

they deem fit.

Seventeenth: There is therefore, on behalf of the fos

ter parents no deprivation of either liberty or property

and therefore no violation of their constitutional rights.

Answer of New York State Defendants

47a

As AND FOR A TH IR D SEPARATE AND COMPLETE

A f f i r m a t i v e D e f e n s e :

Eighteenth: Neither by way of statute or court rule

do plaintiff foster parents have any standing to assert

the claims, if any of the foster children, as they are

neither the parents or legal guardians of the children.

Moreover, such representation in an action of this kind

is particularly inappropriate as the parents are inter

ested parties who may have an interest adverse to those

of the foster children.

As AND FOR A FO U R T H SEPARATE AND COMPLETE

A f f i r m a t i v e D e f e n s e :

Nineteenth: The complaint fails to state a claim for

which relief can be granted.

Answer of New York State Defendants

As AND FOR A F lF T H SEPARATE AND COMPLETE

A f f i r m a t i v e D e f e n s e :

Twentieth: The court lacks subject-matter jurisdiction.

W h e r e f o r e : Defendants Shapiro and Lavine, respect

fully pray this Court enter a judgment:

(a) Denying each and every prayer for relief in

plaintiffs’ second amended complaint and either

(b) Dismissing the complaint; or

(c) In the alternative, entering a declaratory judgment

declaring New York Social Services Law § 383(2) con

stitutional both on its face and as applied; and

48a

(d) Enter a declaratory judgment declaring New

York Social Services Law § 400 constitutional both on its

face and as applied; and

(e) Granting such other, further and different relief

that as to this Court appears just and proper.

Answer of New York State Defendants

Respectfully submitted,

Louis J. L efkowitz

Attorney General of the

State o f New York

Attorney for defendants Shapiro

and Lavine

B y: Stanley L. K antor

Assistant Attorney General

Office & P.O. Office Address

Two World Trade Center

New York, New York 10047

Tel. No. (212) 488-5168

49a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Southern District of New Y ork

74 Civ 2010 RLC

Intervenor Defendants First Amended Answer

and Cross Claim

---------------------_♦-----------------------

Organization of F oster F amilies for E quality and R e

form : Madeline Smith, on her own behalf and as next

friend of Danielle and E ric Gandy; and Ralph and

Christiane Goldberg, on their own behalf and as next

friend of Rafael Serrano, on behalf o f themselves and

all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

—against—

James Dumpson, individually and as Administrator of the

New Y ork City H uman R esources A dministration;

E lizabeth Beine, individually and as Director of the

New Y ork City B ureau of Child W elfare, and as Act

ing Assistant Administrator of New Y ork City Special

Services for Children; A dolin Dall, individually and

as director of the D ivision of Interagency R elation

ships of the B ureau of Child W elfare and James P.

O’Neill, individually and as Executive Director of

Catholic Guardian Society of New Y ork,

Defendants,

50a

----------------------------- _ * ---------------------------------

Naomi R odriguez, R osa Diaz, Mary R obins, Dorothy

Nelson Shabazz, on behalf of themselves and all other

persons similarly situated,

Intervenor Defendants

and Cross Claimants.

Intervenor Defendants First Amended Answer

and Cross Claim

Intervenor-defendants, by their attorney Marttie Louis

Thompson (Toby Golick, Ira S. Bezoza, Louise Gans of

Counsel), answering the Second Amended Complaint

herein, on their own behalf and on behalf of all other

persons similarly situated, allege:

1. Deny the allegations in paragraphs 10, 11, 12, 33, 59,

60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 75, 76 and 77.

2. Deny the allegations in paragraph 9 of Second

Amended Complaint except admit plaintiffs are repre

sented by attorneys from the New York Civil Liberties

Union with resources and experience in constitutional liti

gation.

3. Lack knowledge or information sufficient to form a

belief as to Paragraphs 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 22,

23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39,

40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55,

56, 57 and 74.

51a

As a F irst A ffirmative Defense

4. The complaint fails to state a claim against defend

ants and intervenor-defendants upon which relief can be

granted.

Intervenor Defendants First Amended Answer

and Cross Claim

As a Second A ffirmative Defense

5. Plaintiff foster parents and the class they purport to

represent have no constitutional right to raise and care

for foster children who have been boarded with plaintiff

foster parents by State, City and County Social Service

officials or other authorized agencies pursuant to contract

and license.

As a T hird A ffirmative Defense

6. Under State law, foster parents must be licensed by

the local commissioner of social services before children

may be boarded in their homes; such licenses are of one

year’s duration but may be renewed.

7. On information and belief plaintiff foster parents

and the class they purport to represent board children

pursuant to such foster care license.

8. On information and belief said license does not give

to plaintiff foster parents, or to members of their pur

ported class, the right to board any specific children.