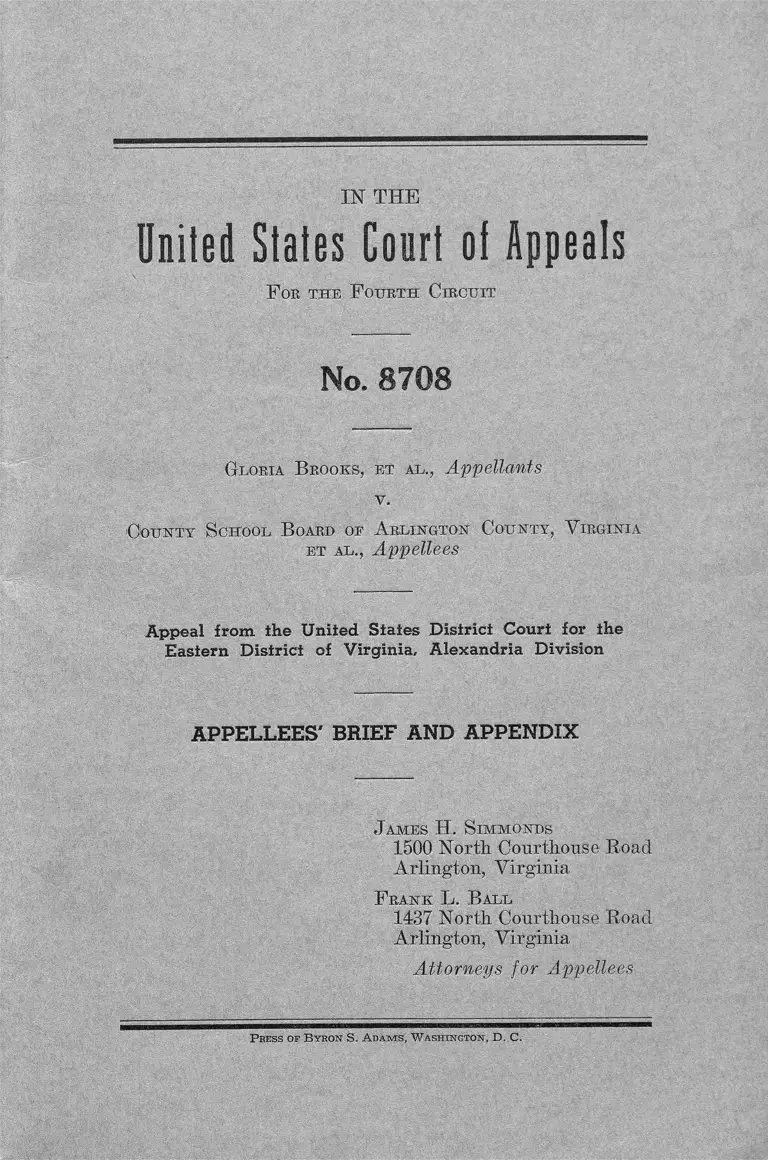

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington County, Virginia Appellees' Brief and Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington County, Virginia Appellees' Brief and Appendix, 1962. 58807599-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b91c2c6a-34ad-43f2-b742-fa2e36742d81/brooks-v-county-school-board-of-arlington-county-virginia-appellees-brief-and-appendix. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

U n ite d S ta te s C ourt ot A p p e a ls

F or the F ourth Circuit

IN THE

No. 8708

Gloria B rooks, et ah., Appellants

v.

County S chool B oard of A rlington County, V irginia

et al., Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Alexandria Division

APPELLEES' BRIEF AND APPENDIX

J ames H. Simmonds

1500 North Courthouse Road

Arlington, Virginia

F rank L. B all

1437 North Courthouse Road

Arlington, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellees

P ress of B y r o n S. A d a m s , W a sh in g t o n , D. C.

INDEX TO BRIEF

Page

Statement of the Case ..................................................... 1

Questions Involved ........................................................... 5

Argument on Sub-question (a) of Question 2—Legality

of Hoffman-Boston D istr ict...................................... 6

Argument on Sub-question (b) of Question 2—-Legality

of Right to Transfer to Schools Having Racial

Majority of the Transferee............................... 11

Argument on Action of Court in Dissolving the Injunc

tion Issued in 1956 and Dismissing the Case from

the Docket ................. 16

CASES CITED

Allen v. School Board of Charlottesville, 203 F. Supp.

225 ........................................................................... .12 15

Briggs v.’ Eliiott’ 132 F. Supp.’ 776 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! i l l ’ 14

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 139 F. Supp.

468 ....................................................... 10,11,12,13,14,15

Goss v. School Board of Knoxville, 301 F. 2d 1 64 ........13,14

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville,

270 F. 2d 209, certiorari denied, 80 S. Ct. 293 . . . .13,14

Maxwell v. County Board of Education of Davidson

County, Tenn., 301 F. 2d 828 ................................... 14

CASES CRITICIZED

United States v. Swift, 286 U.S. 1.06, 52 S. Ct. 460, 76

L. Ed. 999, cited on page 15 of Appellants’ B r ie f.. 18

VIRGINIA STATUTES CITED

Regular Session 1956

Statute Abolishing Elected School Boards, pages

949, 950 ......................................................................... 3

Special Session 1956

Chapter 68, Providing for Closing of Schools in case

of Integration ............................................................. 4

Chapter 70, Setting Up a State Pupil Placement

Board with Exclusive Authority to Assign Pupils 4

Chapter 71, Cutting Off the Expenditure of Funds

to Schools in Case of Integration............................ 4

IN THE

U n i t e d S t a t e s Court of A p p e a l s

P oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 8708

Gloria Brooks, et al., Appellants

v.

County School B oard of A rlington County, V irginia,

et al., Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Alexandria Division

APPELLEES' BRIEF

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The facts in this case are very simple and taken in their

due course are not difficult to comprehend and construe.

Prior to the Supreme Court’s decisions of 1954 and 1955 in

the integration cases, Virginia operated a racially segre

gated school system, and the school authorities in the

County of Arlington, as a school district, were under legal

obligation to follow the laws of the state under which they

held office and consequently, of course, the school system in

2

Arlington was administered on what is commonly referred

to in this case as a dual system of separate and distinct

schools for the white and Negro races.

For the purpose of administering the educational system

of the County, the area was divided into school attendance

districts. One of the districts set up has been referred to

in these proceedings from the beginning as the Hoffman-

Boston District. It was divided into two parts, to-wit, the

northerly district and the main district. The main Hoff

man-Boston District had been originally laid out, the nec

essary building had been erected and the schools were

operated for the benefit of a large community, mostly pop

ulated by Negroes in the southerly part of the County. The

Northerly part of the Hoffman-Boston District included

what is generally known as Hall’s Hill, a very much

smaller Negro section in the northern part of the county.

There are also some scattered Negro residents in other

areas. The main Hoffman-Boston District contained

the only Negro junior and senior high schools and

also an elementary school, and the buildings within the

northern part of the district were for elementary pupils

only. As a result for administrative purpotses, the Negroes

throughout the County entitled to enter junior and senior

high schools attended the facilities in the southern or main

Hoffman-Boston District and the elementary scholars of

the Negro Race attended the Negro school nearest to

their residence.

The schools for white children were at first established

in very definite well knit residential communities. The

population began its great increase in the 30’s and has

proceeded at a very rapid rate ever since and, consequently,

there have been many new attendance districts established

for the white schools. The community for which the main

Hoffman-Boston District had originally been laid out to

serve also showed some considerable growth in residents

but they were generally contained in the same geographical

3

area. Consequently there have been practically no changes

in the main Hoffman-Boston District. It still serves a

well knit community with facilities to take care of the

students in the neighborhood for which it was originally

designed. The Negro children in all of the remainder of

the County now attend the Langston Elementary School

which serves the Negro settlement at Hall’s Hill and for

merly white schools which are set up in the geographical

school attendance districts in which their homes are located.

After the Supreme Court’s decision of 1955, a commis

sion was set up in Virginia, known as the G-ray Commis

sion, to study and report on a state policy. Assuming

that the recommendations of this Commission would be

followed by the Virginia Legislature, the Arlington County

School Board on January 14, 1956, adopted a resolution

providing that integration would be permitted in elemen

tary schools in the County in the fall of 1956 and in

high schools in the fall of 1957.

This action of the School Board created a furor in the

Legislature and the latter by an Act approved March

31, 1956, (Acts of Assembly of Virginia 1956, pages 939-50)

took away from the County of Arlington its authority

to elect its school board and provided that thereafter

counties in the Arlington classification should select the

school trustees by the governing body, to-wit, the County

Board and provided that no school board for any county

or city should be elected by popular vote.

Before the resolution passed by the County School Board

in January 1956, could be put in force to govern the school

session of 1956-1957, the Legislature was called into special

session and passed a number of acts, the most severe of

which provided for the closing of the public schools in any

county in which a Negro was actually admitted to a for

merly all white school; for the cutting off of public funds

to any county in which any integration took place; and

for setting up a State Pupil Placement Board in which

4

all the power of enrollment or placement of pupils in

and the determination of school attendance districts for

the public schools in Virginia was vested. The local

school boards and the division superintendents of schools

were thereby divested of all authority then or at any fu

ture time to determine the school to which any child should

be admitted. (Acts of Assembly, Special Session 1956,

Chapters 68, 70 and 71).

From this time on until the above enactments were de

clared illegal by the courts, the County School Board

was operating with two swords over its head, to-wit, (1)

the injunctive order issued by this Court to the effect

that no child should be forbidden to enter a school strictly

because of his race or color and (2) the provisions of the

law to the effect that the local school boards were entirely

devoid of any power or authority to admit pupils and the

other enactments closing schools and cutting off the reve

nues under the conditions stated. I f they had admitted

the students as ordered by this Court at any time prior

to 1959, the schools would have been closed and they would

have been acting in violation of the state law which they

had sworn to obey and, on the other hand, if they refused

to obey the injunction which required them to do the thing

which state law forbade, they would have been subject to

penalties by this Court. As soon as these state laws were

out of the way, the Legislature in its extra session of

1959 by enactments becoming effective March 1, 1960, pro

vided for the placement of pupils by the local boards under

rules and and regulations promulgated by the State Board

of Education. It was sometime before these rules were

promulgated by the State Board, but promptly after that

promulgation the School Board in Arlington County

adopted placement rules putting the attendance areas

strictly on a geographical basis providing that students

should be placed and assigned to the school districts in

which they reside with the single exception that a child

should be permitted to attend a school in which his race

is in the minority but not compelled to do so, (See Ex

hibit B, Appellants’ Appendix 91a)

From the date of the adoption of the said Exhibit B

forward, the schools of Arlington County have been on a

completely integrated basis and no person has been denied

entrance in any school because of his race or color.

The Appellants’ statements on page 19 o f their brief to

the effect that the School Board had a long prior history

of disobedience to the July 31,1956 injunction during which

the courts were compelled to strike down “ a sophisticated

series of evasive schemes and maneuvers designed to frus

trate the original desegregation order” are not supported

by facts. At no time has the court failed to recognize

that the County School Board was acting in good faith

under extremely trying conditions.

With the passage of the rules and policies as to ad

missions and procedures for placement or assignment of

pupils set out in said Exhibit B, the transition period from

a desegregated school system to an integrated system in

the County of Arlington was completed.

QUESTIONS INVOLVED

1. The main question involved is whether the permanent

injunction granted by this Honorable Court in 1956 against

racial discriminations was porperly dissolved by this Court

in view of the fact that the transition period has elapsed

and the schools of Arlington are now fully integrated.

2. Subordinate to the main question but necessarily em

bodied therein are the two further questions (a) whether

the Hoffman-Boston District is a proper geographical pupil

placement area and (b) whether the provision permitting

pupils in a racial minority in any school to transfer out

side of that school district where the same provision applies

to all races and colors is valid.

6

We believe that the simplest method of presenting these

questions is not to follow the above order of statement

but discuss the Hoffman-Boston District first, the racial

minority rule second and the main rule third. These

questions are, of course, interrelated.

HOFFMAN-BOSTON DISTRICT

The Hoffman-Boston District was established prior to

1948. Because of the segregated system that was then in

force, another small district covering the Negro community

of Hall’s Hill was considered for administrative purposes

to be a part of the Hoffman-Boston District. This small

district which we have heretofore referred to as the north

ern end of the Hoffman-Boston District was eliminated

during the pendency of these proceedings, and the children

of high school age in that district are now assigned to

formerly all-white schools. The validity of the Hoffman-

Boston District as at present constituted has been the sub

ject of investigation in this litigation and its present boun

daries have been approved and accepted by the trial court

as a proper geographical layout.

In the hearing of February 5, 1962, now appealed from,

Mrs. Campbell, who was then Chairman of the School

Board and had also served previousi terms as a member,

stated that the criteria for setting up the school attend

ance district were the capacity of the school, the accessi

bility, transportation, and safety of the pupils (Appellees’

Appendix, p. 17).

Mr. Joy, a former Chairman and still a member of the

School Board, stated that the district lines were laid out

to include “ all or none” of a natural neighborhood within

the area of a particular school and that among the criteria

was the capacity of the school, the walking safety, the

accessibility and the avoidance of unnecessary change.

(Appellees’ Appendix pp. 3-4). At another hearing in this

case, Mr. Joy stated, “ We feel very strongly, however, that

7

in tlie interest of maintaining equivalent balance among

the schools within the community, of providing the best

possible education, that the south Hoffman-Boston Dis

trict was, as set up, is a logical ungerrymandered district

which represented the best judgment on the matter of at

tendance areas.” (Appellees’ Appendix, p. 15) Again

Mr. Joy said, “ The south Hoffman-Boston area, as was

established, is a logical attendance area for the Hoffman-

Boston School.” (Appellees’ Appendix, p. 15) (See also

Dr. Joy, Appellees’ Appendix, pp. 2-4, etc.)

In its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law filed on

September 17, 1958, by the trial court herein, the Court

commented on the Plaintiffs’ contention that the Hoffman-

Boston District was illegally maintained as follows:

“ Plaintiffs urge that invalidity of the assignments

is conclusively established by the result, that is, that

all Negro pupils remain in the Hoffman-Boston School.

Though plausible, the argument is not sound. Actu

ally, the principal reason for the result is the geo

graphical location of the residences of the plaintiffs,

indeed of the entire Negro population in Arlington

County. It is confined to two sections, the Hoffman-

Boston area and the previous, small northern division

of the Hoffman-Boston, several miles apart. Hoffman-

Boston is by far the larger Negro area. This situa

tion seemingly would be frequently found in areas,

like Arlington County, urban in character.

“ It occurs, too, from the relatively small Negro popu

lation in the County. The condition now does not differ

greatly from that noted in this court’s opinion of Sep

tember 1957. Then there were 1432 Negroes in all

of the County’s schools. This compared to some 21,000

white students. The latter are scattered throughout

the County. The concentration of Negro population

is confirmed in this case by the fact that only one white-

school parent was available to testify as a resident of

Hoffman-Boston district.”

And later on:

‘ ‘ The court is of the opinion that Attendance Area,

Overcrowding at Washington and Lee, and Academic

Accomplishment clearly are valid criteria, free of

taint of race or color. It concludes also that these

criteria have been applied without any such bias. It

cannot say that the refusal of transfers on these

grounds is not supported by adequate evidence.” (Ap

pellants’ Appendix 56a, 57a)

In the Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law filed by

the trial court on July 25, 1959, the Court states:

“ The criteria used by the School Board in 1958, and

then for the most part approved by the court, have

been employed by the Board in the present assign

ments. The criteria are still approved.” (Appel

lants Appendix 68a)

In the same statement of Findings of Fact and Conclu

sions of Law, the Court ruled that the applications of

pupils 2, 3, 4, 9, 14, 15, 18, 23, 24 and 25 were all being

denied because they live outside of the districts of the

schools they sought to enter. All of them lived within the

Hoffman-Boston School area. The Court in approving

the Hoffman-Boston geographical attendance district then

said:

“ Considering school bus routes, safety of access and

other pertinent factors, it cannot be found that the

School Board’s assignments are arbitrary or predi

cated on race or color. The bounds of Hoffman-Boston

district do not deprive those within it of any advantage

or privilege.” (Appellants’ Appendix 71a)'

Again in the Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

filed September 16, 1960 (Appellants’ Appendix 80a, etc.),

the Court comments upon the attendance districts.

Judge Lewis in his Memorandum Opinion at the hearing

on which this appeal is based stated as follows:

8

9

“ Originally, school boundaries were established by

taking into consideration the size and location of the

physical plant, the number of pupils to be accomodated,

the distance between the residence of the child and

the school, the traffic encountered en route, together

with the purpose of carrying neighborhoods into the

schools intact. These criteria have been followed in

the establishment of attendance areas for new schools

as erected and in the amendments1 of old attendance

areas when and as necessitated.

“ There is no evidence in this case to sustain the charge

that the geographical boundaries of the Hoffman-B os-

ton and Langston schools were either established or

are being maintained to perpetuate segregation. ’ ’ (Ap

pellants ’ Appendix 157a)

We do not admit that the question of the validity of the

Hoffman-Boston District is still open. Judge Bryan and

Judge Lewis have both held that the district is a proper one.

All of the testimony of members of the School Board is to

that effect. The decisions of Judge Bryan have been con

sistently appealed and consistently approved by this Hon

orable Court. The question of the legality of this district,

therefore, has already been litigated in these proceedings,

has been sustained and the finding of the Court has been

approved on appeal.

We have every reason to believe that the actual residents

of the Hoffman-Boston District are satisfied with its boun

daries. This is very strongly evidenced by other facts

indicated in the record. In the spring of 1961, pursuant

to state law, the School Board considered an attendance

area map for the distribution of the pupils1 in the County

system. Public hearings were held after due notices in

the local newspaper and also distributed through the

pupils of tlhe schools. Citizens were notified that they

could come and look at the maps. The maps were dis

played. Many citizens did come, some of whom were

Negroes. The number included Mrs. Hamm who is one

of the Plaintiffs in this case (erroneously referred to in

10

the transcript as Mrs. Hume). No Negroes raised any

objection to the Hoffman-Boston District. Apparently the

district has not only the approval of the Court but the very

definite approval of the community which is not denied

by any evidence herein. This type of a hearing has been

held every five years when the regular decennial national

census is taken and at the midway break between the same

when there is an estimated or local census taken. Thereis

no evidence whatever that there has ever been any objec

tion raised at any of these meetings concerning the l lolT-

man-Boston District. (Testimony of1 Elizabeth B. Camp

bell, Appellees’ Appendix, pp. 19-20, 25-26).

In the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

139 F. Supp. 468, the District Court of Kansas reviewed a

somewhat similar situation and said:

“ It was stressed at the hearing that such schools as

Buchanan are all-colored schools and that in them there

is no intermingling of the colored and white children.

Desegregation does not mean that there must be in

termingling of the races in all school districts. It

means only that they may not be prevented from inter

mingling or going to school together because of race

or color.”

Every time the District Court in the instant case has re

fused on geographical grounds to transfer an applicant

from the Hoffman-Boston District to another district, it

has upheld the layout of the Hoffman-Boston District as

a valid attendance district; and each time this Honorable

Court has approved the action of the lower court as above,

it, too, has approved the district as a proper one. This

question, therefore, which has either been passed upon

directly by the Court at former hearings and the ap

proval o f which has been inherent in each of the decisions

regardless of whether the question was specifically dis

cussed in the opinion, is in our opinion no longer an open

question but has been definitely decided in previous steps

in this case. No change of conditions has been shown by

11

tihe Appellants to warrant this Honorable Court in chang

ing the ruling on this question.

We submit, therefore, that the Hoffman-Boston District

is a proper geographical pupil placement area laid out

with due regard to the boundaries of the natural com

munity which it serves and with effect being given to the

questions of accessibility, transportation, safety and con

venience of the people served within its boundaries.

IS THE RIGHT TO TRANSFER BECAUSE OF RACIAL

MINORITY A VIOLATION OF THE APPELLANTS'

CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS?

This question is not a new one in litigation in various

sections of the country concerning application of the Su

preme Court’s decision in the Brown case. This rule of

transfer has been definitely upheld by the United States

District Court for the Western District o f Virginia and by

the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in several cases.

As a preliminary, the attention of the Court is directed

to the per curiam opinion in Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp.

776, mentioned by the learned District Judge in his Mem

orandum of Opinion in this case. Mr. Justice Parker, in

commenting upon the Brown case, stated that the Supreme

Court had not decided that the states must mix persons of

different races in the schools or must deprive them of the

right of choosing the schools they attend. He goes on to

say that what the Supreme Court had definitely decided

was that a state may not deny to any person on account

of race the right to attend its schools and that the Con

stitution did not require integration but merely forbids

discrimination. Especially apropos of the present situ

ation was Mr. Justice Parker’s statement:

“ It does not forbid such segregation as occurs as

the result of voluntary action. It merely forbids the

use of governmental power to enforce segregation.”

12

“ The Constitution forbids the use of governmental

power to enforce segregation. The 14th Amendment

is a limtiation upon the exercise of power by the

state or state agencies, not a limitation upon the

freedom^ of individuals . . . Nothing in the Constitu

tion or in the decisions of1 the Supreme Court takes

away from the people freedom to choose the schools

they attend.”

The difference between using the power of the state to

forbid a person to enter its schools on account of his race

on the one hand and the voluntary act of an individual

pursuant to his own wishes in seeking a transfer is very

marked. In the Brown case the Court was dealing entirely

with the question of the state or one of its agencies saying

to a child you shall not enter here because of your color,

while in the rule under consideration the child is not being

denied any right but is simply being allowed to exercise

his own choice without compulsion or duress.

In Allen v. School Board of Charlottesville (Western

District of Virginia), 203 F. Supp. 225, Judge Paul had

under consideration a school plan that provided that all

students (white and Negro) would be enrolled initially

in the school district in which they lived and that pupils

of either race being in the minority could transfer to a

school where their race was in the majority. In Charlottes

ville at that time Jefferson District was heavily populated

by Negroes and the other districts of the city had a ma

jority of whites. One hundred forty white pupils living

in Jefferson District were transferred to other schools

under this rule and fifty Negro students living in districts

where the prevailing majority were wThite were transferred

to Jefferson where the Negro race predominated. The rule

provided that this type of transfer would be made by the

Superintendent of Schools upon the application of the

child involved or its parents.

The Court mentioned as an alternative to this policy all

children could be assigned strictly on a geographical basis

13

with no transfers allowed which would result in enforced

integration of all schools and commented that “ it is not

believed that the law requires this, nor, apparently is it at

present desired by a majority of either race.” The Court

proceeded to hold that this type of a rule would not violate

the decision in the Brown case or the Constitution and that

the rule itself wTas permissible and not discriminatory.

In Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville,

United States Court of Appeals, 6th circuit, 270 F. 2d 209,

228, 229, 230, certiorari denied, 80 S. Ct. 293, the rule under

review was practically word for word identical with the,

one at issue in the instant case. The Appellants charge

there, as the Appellants do here, that this was an evasive

scheme to circumvent the Brown decision and perpetuate

segregation. The Court upheld the rule and stated that

where a free choice was provided it was proper and not

forbidden by the Supreme Court decisions and mentioned as

many others have that the courts have not held that there

must be intermingling of the races in all school districts.

In its opinion the Court said:

“ There is no evidence before us that the transfer

plan is an evasive scheme for segregation. If the

child is free to attend an integrated school and his

parents voluntarily choose a school where only one

race attends, he is not being deprived of his constitu

tional rights.”

The above ruling has been passed on twice since the

Kelley case by the 6th Circuit -Court of Appeals. The first

case is that of Goss v. School Board of City of Knoxville,

301 F. 2d 164. The Court upheld the rule and reaffirmed

its ruling in the Kelley case on a similar provision with

the additional comment:

“ This transfer provision functions only on requests

with the students or their parents and not with the

Board.”

14

A similar rale was before the same court in Maxwell v.

County Board of Education of Davidson County, Tenn.,

301 F. 2d 828, the Court expressly adhered to its ruling in

the Kelley rase and the Goss case and upheld the rule.

In the instant case Judge Lewis has gone very carefully

into this question and has called attention to the fact that

the evidence in this case indicates that a substantial num

ber of both Negro and White parents desire the right to

send their children to a school in which a majority of their

race attend. (Appellants’ Appendix 164a). He reaches

the same conclusion that Judge Paul does in very similar

language and soundly applies the holding of Justice Parker

in the Briggs case and the decisions of the 6th Circuit

Court of Appeals above cited.

The Brown case and the present case are dealing with

denial of rights. It is now very definitely the law of the

land that discrimination cannot be exercised by a public

body in dealing with the civil rights of the people. The

only civil right involved in these proceedings is: the right of

the Negro to enter a public school of Arlington County

which under the appropriate and legal rules he would be

entitled to enter and the power of the Court is in

voked to enjoin a public body infringing upon his

civil right to do so. We are dealing entirely with

inhibitions. The rules laid down by the County School

Board and now in force provide for a completely integrated

system and under those rules any Negro child can enter a

school in his geographical district in exactly the same man

ner as any white child can. Before the rule is called into

play, the child who desires a transfer must already be in an

integrated school. There must be both white and Negro

pupils. Having asserted his right to enter that school

and that right having been recognized, accomplished and

his entrance permitted, this rule then gives him the free

dom if he so desires, to transfer to a school in which his

race is in the majority. There is no attempt here to

15

perpetuate segregation for the schools o f Arlington County

are already completely integrated under the rules laid

down by the County School Board. I f it so happens that

white families move into the Hoffman-Boston District

(and there is nothing to prevent it) their children would

be definitely assigned to the Hoffman-Boston School. If

colored children are reared in the Washington-Lee Dis

trict (as they are), they would be assigned to Washington-

Lee High School. Likewise, in all the other districts in

the County. This freedom of choice, therefore, only arises

after the civil right to enter a school without restriction

as to race is recognized.

In the Brown case the Court states that the denial of

a Negro’s right to enter a school simply because of his

race or color gave to the Negro applicant an inferiority

complex, the bad effect of which could hardly be

estimated. There is no such inferiority complex in

volved in this rule of transfer. He is already given

an equal position in the school in his original assign

ment to an integrated school. There is nothing humili

ating to him in the situation. Having satisfied his

demand or his civil rights, the rule then opens it up

to his1 free choice as to whether he shall stay in that

school or move to one in which his race prevails.

No right, therefore, is denied to him. His freedom of

choice under these circumstances is simply held open to

him to exercise if he so desires.

This same choice is open to everyone without regard

to race or color, and so long as the school authorities

keep the current of free choice clear and uncontaminated,

the rule is proper and legal and by no means discrimina

tory.

That the rule is a wise one is shown in the Charlottesville

case where it has been used widely by both races apparently

to the satisfaction of all. That no one has appeared

and testified in this1 case, either parent, student or

16

expert, against this rule indicates that it will be wisely

used here. Judge Lewis specifically points out that

“ there is no evidence in this case indicating the voluntary

transfer provision of the Arlington rules of admission

either has been or will he used to perpetuate racial dis1-

crimination. ’ ’

We, therefore, submit on this particular question that

it is not in any wise in conflict with the decisions of the

Supreme Court; that it is a fair rule; that it does not deny

anyone any civil right; that it is not discriminatory; and

that it is in keeping with the freedom of choice which is

one of our fond traditions; and that, therefore, it is legal

and was properly approved by the lower court.

THE LOWER COURT WAS PLAINLY RIGHT IN DISSOLV

ING THE INJUNCTION ISSUED IN 1956 AND DIS

MISSING THIS CASE FROM THE DOCKET

We will not labor the Court with a long discussion on

this question. The Supreme Court recognized there would

be many local questions arising in the enforcement of its

decision. On these questions it held that the school author

ities have the primary responsibility of elucidating, assess

ing and solving these problems and that the governing

constitutional principle involved is that a student shall

not be denied because of his color the right to attend any

school which he is otherwise entitled to attend.

The function of the courts is to consider whether the

action of the school authorities constitutes good faith im

plementation of the governing constitutional principles.

With regard to the jurisdiction of the district courts,

the Supreme Court very wisely states that it would be

limited to the period of transition from a segregated

system to an integrated system. When this period of

transition is completed, there is no need of retaining the

cases upon the docket or exercising any further jurisdiction

over the matter and, in fact, the Supreme Court contem

17

plates a definite restriction to the period of transition

only.

Judge Lewis in his opinion (Appellants’ Appendix 166a)

stated:

“ None of the plaintiffs in this case are now asserting

a denial of any constitutional right. All issues raised

by the pleadings have been adjudicated. All pupils

residing in Arlington County are assigned to the school

district in which they reside, regardless of race or

color. All of the facilities and activities under the

control of _ the Arlington County School Board are

being administered on a non-diserkninatory basis—

education, athletic, dramatic, social.”

All of the evidence in this case supports this conclusion

of the trial judge and there is not a scrintilla of proof

to the contrary.

In this case the dismissal is justified for two reasons

(1) the transition period has elapsed and (2) the condi

tions have completely changed and neither the injunction

nor the pendency of the case is any longer needed.

The Appellants in their brief maintain that the only

changed condition relied upon by the Defendant in support

of its motion to dismiss “ is a claim of obedience to the

injunction” . The facts do not at all support this state

ment. When this case began, Arlington was operating

under a segregated system. As it proceeded, the state

laws were changed so as to forbid the local school board

to make any placements or assignments in the schools.

Statutes were enacted to cut off school funds and close the

schools in case of any integration. All of these things

are now passed. Segregation has faded into integration,

the school fund provision has died of illegality and the

school closing enactment has passed away from the same

malady. The only change sought in this litigation was

a change from the segregated to an integrated system.

It has been completed. It was started before this suit

18

was even filed by tlie county school board when they had

authority to make placements. It was completed as soon

as the authority was returned to the county school board,

and today the plan of integration as spelled out in the

school board regulations for admissions and transfers is

free of any racial taint or any discriminatory provision

and this case is totally lacking in proof of any discrimina

tion whatever since the plan was adopted.

The case of United States v. Swift (Appellants’ Brief

15) which seems to be wholly relied upon by the Appellants

is not at all in point. That case was brought because of

anti-trust violations and was a continuing decree relating

to a matter over which the jurisdiction of the courts had

no limit in time. Here we have, however, the question of

transition of certain functions of a public body with the

time limited in the jurisdiction of the courts strictly to

the period of transition. In other words, the transition

having taken place, the whole matter over which the courts

have jurisdiction is complete and ended. There is no

need for the case to remain on the docket because there

is nothing else to do. There is no need for the injunction

because the transition sought by the injunction has been

completed.

The fact that the Arlington School Board has acted in

good faith has been observed by the Court in the memo

randa filed with its conclusions. There is not a single one

of the Plaintiffs asserting any denial of any constitu

tional right. In short, questions involved in the litigation

have been resolved and the limitation placed by the Su

preme Court on the district courts has expired with the

completion of the transition. The policy, custom, usage

and practice of segregation on which the injunction of

July 31, 1956, was issued has vanished into history and

there is not a vestige of it left. It is plain, therefore, that

the continuing supervision of the Federal Court by reason

of said injunction constitutes an unnecessary and undesir

19

able interference by the Federal government with officials

of the sovereign State of Virginia in the conduct of a

purely local, non-federal activity.

It is, therefore, respectfully submitted that the District

Court was plainly right in terminating the injunction and

striking the case from the docket.

Respectfully submitted,

James H. S immgnds

1500 North Courthouse Road

Arlington, Virginia

F rank L. B ale

1437 North Courthouse Road

Arlington, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellees

APPENDIX

Page

Excerpt from Testimony of Thomas Edward Ratter .. 1

Excerpt from Testimony of Barnard J o y ......................1-12

Excerpt from Testimony of Elizabeth B. Campbell .. 12-21

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Excerpts from Testimony of Thomas Edward Rutter

September 11,1957

Questions By Mr. Robinson:

Q. Mr. Rutter, you gave some testimony before the last

recess as to how you would formulate for white and

Negro students respectively just to districts. Now the

processes that have been employed for formulating school

districts for both elementary and secondary students, for

both whites and Negroes, of the present processes that

you have used, have been used for the—isn’t something

brand new—they have been used for some period of time,

have they1? A. That’s correct.

Q. iSay during the entire term of office that you have

occupied the office? A. I think it antedates that.

Q. Beg pardon? A. It goes beyond that.

Q. Goes back beyond that. Thank you very much. That

is all.

APPENDIX

Excerpts from Testimony of Barnard Joy

July 21, 1960

Questions By Mr. Siramonds:

Q. Now, Dr. Joy, you mentioned that on each data sheet

there was item marked school district. Will you, please,

explain somewhat in detail to the Court how these school

districts or attendance areas are arrived at? A. In any

large school system it has the problem of equitable dis

tribution of its students among its school buildings. With

out attendance areas the teacher in one school might have

40 pupils, while the teacher in the nearby school might

have only 20. The establishment of attendance areas in

the means by which teaching loads and educational op-

2

portunity are equalized. In the case cited an attendance

line between these two schools should be drawn so that

there is a class size of abont 30 in each of the two schools.

Attendance areas have been used in Arlington for many

years and there have never been dual areas. One criteria

in their establishment is to keep them as constant as pos

sible. There are some educational readjustments and to

parents and children very disturbing, family and social

disruptions when even though their place of residence re

mains the same, the children are moved from one school

to another before graduation.

The basic procedure in establishment of attendance areas

is to determine total enrollment. Twelve thousand, for

example, to determine the number of classrooms available,

400 for example, and divide enrollment by classrooms to

determine average class size. In the examples cited,

12,000 divided by 400 gives 30. Each school is then assigned

a quota. By multiplying its number of classrooms by the

average class size for the system. In our example a

6-classroom building would have a quota of 180. A

12-classroom school a quota of 360, and a 20-classroom

school a quota of 600. Location of each school building

and its quota is put on the map. The number of students

in each block is put on the map. Alternative lines between

schools are tried to get a total map on which each school’s

quota and the number of students living within the attend

ance area are the same. Distance from the school is the

first but not the only criteria in drawing attendance area

lines between schools.

The 6-room school must have a smaller area, not to

exceed its quota of 180. The 20-room school will have a

much larger area to include' its quota of 600. It is in

evitable that the line drawn between these two would be

closer to the small school. This means; that some students

living 6 blocks from the small school and 10 blocks from

the large school will be in the attendance area of the

large school. Some of the more important considerations

3

other than size and distance are walking safety and natural

neighborhoods. To avoid having children cross major

streets or highways, such streets or highways are fre

quently used as the lines between two schools. I f this

were not done, Arlington would need many more school

crossing guards than it has today. Small children living

in a suburban area associate themselves with other chil

dren in the neighborhood play groups. As they go to

school they feel more secure and undertake school work

more readily if they attend the same school as their

playmates.

A criteria in establishing lines is, therefore, to include

all or none of a natural neighborhood within the attendance

area of a particular school, determining which neighbor

hood goes to which school is a matter of judgment, but is

usually determined by one or more of the other criteria

which are size, distance, walking safety and avoidance of

unnecessary change.

While size of -the area in terms of pupil population is

the major criteria, the application of the other criteria

results in minor deviations which in some cases give one

20-room school an enrollment of 640 or 32 per class and

another an enrollment of 560 or 28 per class.

In summary, let me say that the establishment of at

tendance areas is an absolute essential in providing rela

tively equal educational opportunity for all children in

a large school system, that many months of work assem

bling and analyzing data on alternatives precede the estab

lishment of areas, that changes in one school area affect

other schools, that changes from year to year should not

be made without good reason and that selection among

possible alternatives is a matter of judgment that requires

careful consideration of several important criteria.

Questions By Mr. Beeves:

The Court: Well, that was my error in following your

testimony.

4

Now let me ask you one more question. How long

have the school districts been in effect which are now

represented on these four charts, exhibited on the board!

The Witness: Well, school attendance areas have been

in effect since I have been on the Board for twelve and a

half years.

Looking at the senior high chart, this school attendance

here for the Yorbtown Senior High School is on the map

for the first time in 1960-61 because the Yorktown Senior

High School is just now being completed and is the school

which will be occupied for the first time. Prior to this

the map was divided into three school districts. When

I came on the Board twelve years ago we had a much

larger district for Swanson which then existed.

The Court: Let me stop you right there on the senior

high school. How long had the three areas been in effect,

leaving out the Yorktown!

The Witness: The three areas had been in effect about

six or seven years because Wakefield was occupied about

six or seven years ago. I t ’s been newly built during this

period.

The Court: Now, the condition of Yorktown District,

does not diminish the Wakefield District as it existed prior

to Yorktown’s coming into being, does it!

The Witness: I think it does. I can’t be 100 per cent

sure, but whenever you get a new school in the picture,

it tends to affect the lines for all the other schools.

The Court: Now will you tell me about the junior high

school.

The W itness: The junior high schools when I came on the

Board, we had a much larger area for Stratford. We had

some junior high school pupils attending Washington-Lee.

We had a much larger area for Jefferson. We had a Hoff-

man-Boston area. Since coming on the Board, why, we have

had new schools at iStratford, Williamsburg, Kenmore and

Glunston which have changed the shape of the lines and the

attendance areas because the enrollment during this period

5

in the junior highs has grown from about 2,000 when I

came on the Board in ’48 to about 6,000 now. And the

setting up of these attendance areas, it has been a process of

first of all building new schools to keep up with the in

creasing enrollment, trying to locate them as best we can

to serve that enrollment. But then when yon had a new

school and a certain capacity, you put down the capacities

for all of your schools, plotted all of your pupils, and tried

to give to each school the number of pupils that it was

equipped to handle so that they would all have equal loads.

The Court: Well, then, the junior high school plats as

it appears on the board is effective for the first time in

the next session1?

The Witness: No, this as it appears, I believe, is un

changed from last year. We, and I think maybe unchanged

from the year before—we occupied Gfunston Junior High

School in the fall of ’58 or ’59. I think this has been in

effect about two years. Our last junior high school was

this one and in ’58—now there have been similar changes

on the elementary map and they are much too numerous

to try to explain because we have had during this twelve-

year period that I have been on the Board, this school is

new, and we could go down, the list; this school is new,

this school is new, this school is new.

The Court: Well, then, it is correct to say that there are

numerous changes that will be effective for the first time

this session in the elementary schools?

The Witness: No, there have been no, no elementary

schools this year. There were some changes in the chart

in this map, I blieve, in the fall of ’59 because we had an

addition here. But this is—were minor. The changes in

the elementary schools in -the last three or four years have

been very minor, because our problem and what this in

volves is that the increasing enrollment grew out of the

war babies, who first came into the elementary schools, so

that our markedly increased enrollment in the elementary

schools were in the years ’48 to ’56. Then our enrollment

6

since then has stayed level. It is, during the [period when

you’re building new schools, take care of increasing enroll

ment, that you have to change these attendance areas.

Once your enrollment becomes level and your school planned

adequate, then your attendance areas essentially remain the

same so that these haven’t changed much in four years.

Then the load moved on into the junior high where it is

at the present time. This hasn’t changed much in the two

years, and the senior high which has not yet received the

brunt of the war babies was changed this year as we got

the new school in preparation for that big increase that

comes at that time.

Questions By Mr. Beeves:

Q. Dr. Joy, referring to the school districts on the senior

high map, that is, Exhibit 1960-E, as I understand it, there

are presently or at least for the forthcoming school year

there are four high schools serving the Arlington County,

is that correct'? A. That is correct.

Q. Yorktown, Wakefield, Washington and Lee and Hoff-

man-Boston? A. That is correct.

Q. And the geographic boundaries of these school dis

tricts, if I understood you, are relatively the same as they

were except for the boundary which now encompasses York

town, which will he in operation for the first time this com

ing school year? A. That is right.

Q. Now I am pointing to what is the Hoffman-Boston

Senior High District which appears to be something of an

irregular-shaped island in the middle of Wakefield District.

Would that he an apt characterization of this? A. It is

at one side of the Wakefield District.

Q. Well, what I am—let me refer to it another way. A.

There are—this is Government property over here.

Q. Well, there is, there appears to be on this map an

area which would be southeast of the Hoffman-Boston Dis

trict? A. That is right.

7

Q. Which is a part of the Wakefield District? A. That is

right.

Q. So that now would it also be correct to say that the

Hoffman-Boston Senior High School District is the only

high school district which exists within another high school

district? A. Because of the fact that this, this is non

residential property, it is not within another high school

district. In other words, this is essentially unzoned area

here because it is nonresidential area.

Q. But all of the other high school districts including

Wakefield have a dividing line which is contiguous to two

districts. In other words, the dividing line, there is a divid

ing line between Wakefield and Washington and Lee? A.

Yes.

Q. There is a dividing line between Washington and Lee

and Yorktown? A. Yes.

Q. But Hoffman-Boston, all of its boundaries' are within

the Wakefield District? A. There is a dividing line between

Hoffman-Boston and Wakefield; this portion over here is

a nonresidential portion.

Q. Well, at least, as these lines are drawn on the map,

all of the boundaries of Hoffman-Boston are within the

Wakefield area; at least, there are no other lines which

would indicate to the contrary? A. That is right.

Q. Now can you tell us, sir, what is the high school class

size pupil-teacher ratio, whichever standard you use for

Hoffman-Boston? A. The expected pupil-teacher ratio for

Hoffman-Boston next year will be one teacher per 18.7

pupils.

Q. And what is the ratio for Wakefield? A. One teacher

per 20.9 pupils. In other words, class size is smaller in

Hoffman-Boston.

Q. Well, now I think you told us previously that in de

termining school districts one of the standards, or one of

the criteria that was used was an effort to equalize pupil

distribution among the several schools that might be af

fected, is that correct, sir? A. That is correct.

8

Q. Well, now can yon tell ns when the Hoffman-Boston

District as it now exists was first created insofar as yon

know! A. Insofar as I know it was created prior to my

becoming a member of the Board in 1948 on generally its

present lines.

Q. Well, now, as it is presently created, then, or as it

was created then at the time yon first knew it, has there

been any adjustment of this district to reflect an effort to

equalize the pupil-teacher ratio between this district and

Wakefield? A. The adjustment in this area has been that

of building additional classrooms at Hoffman-Boston to

take care of the attendance within the area.

Q. I see, so that you have made, there has been no effort

to, let’s say, redraw the line in such a way as it might

include pupils from Wakefield in order to reduce the pupil-

teacher ratio at Wakefield in comparison with Hoffman-

Boston? A. One of the basic criteria used in establishment

of attendance areas is that of avoiding change, if possible.

And in this particular case we avoided change by building

classrooms. This is something we try to do everywhere.

Q. And you do that, notwithstanding the pupil-teacher

ratio at Wakefield apparently has not been able to keep

pace, that is, the reduction in that with additional class

rooms that you have built at Hoffman-Boston? A. I think

it was earlier pointed out in my testimony that frequently

the application of other criteria would give a range as much

as from 28 to 32, around 30. In other words, 4. Here are

maximum range on the junior and senior high schools, a

range of 18.7 to 21.7 which exists at Kenmore Junior High,

and is well within the concept of relatively equal situation.

Q. Well, now isn’t it also a fact, Dr. Joy, that the bound

aries of the Hoffman-Boston District as they originally

existed were set or established in order to include sub

stantially, the substantial bulk of the Negro population as

it then existed under our separate school system? A. I

assume that those lines were set in line with the important

criteria of neighborhood groups.

9

Q. And the neighborhood group factor involved with

Hoffman-Boston. School at that time was the factor of race,

isn’t that correct, sir? A. The play group, the neighbor

hood group does sometimes break down on that basis.

Q. Now since 1954, or since 1956, when the Arlington

County School Board has been under injunction by this

Court to eliminate race as a factor in school assignments,

has ithe Board reconsidered the existing boundaries of the

Hoffman-Boston School District in any formal action? A.

In no f ormal action.

Q. So that the boundaries as they existed at the time

when they were established to conform to neighborhood

or racial patterns and as they exist today are substantially

the same? A. They are substantially the same.

Q. With no reconsideration in eliminating that possible

factor? A. Well, of course, the observation would be true

in that we always try to observe the neighborhood relation

ship factor.

Q. Now we speak of the neighborhood relationship fac

tor. Let’s take the Hoffman-Boston School which is here,

on a neighborhood-factor basis, let’s assume we have a

Negro student living in this area. Now would the neigh

borhood-factor basis relate that student more closely to this

school or to, say, Wakefield School, which ;is here? A. I

explained that the neighborhood-relationship factor was

one in which, in a particular neighborhood, we would like

to send a neighborhood to a single and a particular school.

Now every school draws to several neighborhoods. Some

of which are unrelated to each other, but within a single

neighborhood, a neighborhood being a much smaller unit

here. I don’t know how many neighborhoods you would

find here but possibly 10 or 15 and we don’t like to break

up any one of those and send part one place, part another.

Q. Well, now may I ask you, Dr. Joy, for your knowl

edge and observation of the population and its distribution

in Arlington County, would it be fair to state that that

characteristic of description most common to the neighbor-

10

hood which encompasses or which is encompassed within

the Hoffman-Boston School District would he that of racial

identification! A. This is a common factor, yes.

Q. That is the most common factor; wouldn’t that be

true, for school purposes, play purposes! In other words,

within the Hoffman-Boston District, going back now to the

fact that the—it originally was created to serve the sep

arate but equal school system—that the neighborhood

factor most common to those pupils or students still living

within that district would be that of race! A. Well, I

don’t know as you can say one factor is more common than

another. This was a common factor.

Q. Could you suggest any other that might be, that might

distinguish, let’s say, the Hoffman-Boston School District

neighborhood from the other neighborhood adjacent to it!

A. Well, the common factor in all neighborhoods is prox

imity of residence of the group.

Q. Well, on the basis of proximity of residence I think

as we indicated on the map there would be some residences

within the Hoffman-Boston School District which would be

closer, let’s say, to Wakefield than it would to the Hoffman-

Boston! A. Proximity of residence to each other is the

factor in development of the neighborhood.

Question By Mr. Beeves:

Q. Now with reference to the junior high school map,

and here we have a Hoffman-Boston Junior High School

which I assume is in the same building, is that correct, sir!

A. This is in the same building.

Q. Bight. Now here again your testimony generally with

respect to the history of the school district boundaries

which appear to be substantially the same on both maps,

would be the same! A. That is right.

Q. In other words, that this was the school district orig

inally created under the separate-buit-equal system, and

that there has been no substantial change! A. There have

been some but no substantial.

11

Q. No substantial change, and here again I believe we

have the Hoffman-Boston School District actually cutting

across or truncating the Guns ton Junior High District, is

that correct, sir! A. Yes, that is the Gunston Junior High

District.

Q. So that this area here which represents the City of

Alexandria and was not in your school system would indi

cate that the western extremity of the Hoffman-Boston

District, the Hoffman-Boston School cuts into and cuts

aeros the Gunston Junior High District dividing it—well, I

suppose this would be east and west. In other words, the

Hoffman-Boston School District actually divides the Gun

ston Junior High School District east and west down to

the line of the Alexandria schools ! A. Seems so on the map

more than in actual case because the main thoroughfare, of

course, is Shirley Highway and, of course, this situation is

not unusual if one will look at the elementary map where

one sees a school district like Page surrounding a school

district like Cherrydale which grows out of the fact that

the capacity of this building is small and, therefore, you

draw an area big enough to take care of the capacity of

this building, is large, and so it has a different-shaped dis

trict to take care of enough pupils to fill the school’s quota.

Question By Mr. Beeves:

Q. The Hoffman, the South Boston, the South Hoffman-

Boston area district as it presently, as it exists up until the

present time, has been used solely for the purpose of making

assignment of Negro students! A. The South Hoffman-

Boston area as was established is a logically attendance

area for the Hoffman-Boston School.

In answer to question by the Oourt:

We feel very strongly, however, that in the interest of

maintaining equivalent balance among the schools within

the community, of providing the best possible education,

12

that the South Hoffman-Boston district was, as set up, is

a logical ungerrymandered district which represents the

best judgment on the matter of attendance areas.

* * * * * * * * * *

Excerpts from Testimony of Elizabeth B. Campbell, Chairman

of the School Board, at the Hearing on February 5th, 1982

Direct Examination

By Mr. Simmons:

Q. Will you please state your name and address? A.

Elizabeth B. Campbell, 2912' North Glebe Road, Arlington,

Virginia.

Q. You have some position with the School Board of

Arlington County? A. I am the Chairman of the School

Board.

Q. Have you served on the School Board prior to your

most recent term? A. Yes.

Q. Will you please tell the Court the years that you have

served on the Arlington County School Board? A. From

1947 to 1955, and then I was returned 3 years ago. This

is my third year.

Q. Mrs. Campbell, calling your attention to your first

term during the year 1949, were there any maps as such

which set forth the attendance areas in the schools of

Arlington County? A. Not that we could find.

Q. You don’t know what occurred before that time as

far as going to school? A. No, sir.

Q. What was done at that time and why with respect to

making attendance area maps? A. Well, we needed the

attendance area maps because though there were attendance

areas, Mr. Kemp seemed to be the person who knew where

they were and we were increasing the staff and getting

ready to build new schools to take care of the increased en

rollment and needed the map for reference so the attendance

maps were made.

13

Q. What were the principal purposes of making those

attendance areas or what were the criteria used in arriving

at attendance areas ? A. Our first criteria was the capacity

of the school. It had to he. And the second consideration

was the accessibility of the school. There was no bus trans

portation at that time, no school bus transportation and

then we tried to consider the safety of the pupils. There

were in many instances no sidewalks. There were some

main highways to be crossed. Those were the chief consid

erations.

Q. Calling your attention to that first map, isn’t it true

that the Hoffman-Boston District, School District as shown

on that map for the southern part of the county is almost

identical with the Hoffman-Boston High School Area that

is shown on the present map? A. As far as I know. There

have been no actions of the Board to change any of these,

so they must have been related. Any changes would have

been related to land.

Q. Was it necessary to have put all the colored high

school students within an attendance area in 1949 if you

want to do it for the purpose of segregation? A. Tes, sir.

We had segregated schools in Virginia.

Q. I mean the colored children would have had to go to

colored schools regardless of whether they were in attend

ance area, would they not? A. Yes, because we had segre

gated schools.

Q. Isn ’t it true that the attendance area around the

Hoffman-Boston High School was made with respect to the

capacity of that school and the safety of the children at

tending the school?

Mr. Reeves: Objection, if Your Honor, please. I think

this is a leading question.

The 'Court: I will admit it is a trifle leading.

Mr. Simmonds: Yes, sir.

The Court: Frame it otherwise, Mr. Simmonds.

14

By Mr. Simmonds:

Q. Mrs. Campbell, can yon tell us to what extent, if any,

the actual lines around Hoffman-Boston were drawn insofar

as any segregation requirement was concerned?

The Court: You mean in 1949?

Mr. Simmonds: 1949.

The Witness: We had a segregated school system, Mr.

Simmonds.

The Court: That was not the question, in 1949, was it?

Mr. Simmonds : That is the point I am bringing out.

The Witness : We had a segregated school system.

By Mr. (Simmonds:

Q. But, nevertheless, in 1949 you did draw lines around

Hoffman-Boston to indicate the capacity and safety ele

ments? A. Oh, yes.

Q. That has remained fairly constant since, has it not?

A. Yes.

Q. Now, Mrs. Campbell, was Mr. Rudder with the Arling

ton School (System in 1949 when these attendance areas

were first made up? A. No, sir.

Q. And do you recall when he first came with the school

system? A. I don’t recall the year. Mr. Early was our

first superintendent after Mr. Kemp and then Mr. Rudder

succeeded Mr. Early.

Q. But, Mr. Rudder was after that first attendance map

was gotten up, was he not? A. Oh, yes.

Q. So, he would not be in a position to know of his own

knowledge the reasons why the area was set up, would he

not?

Mr. Reeves: Objection, if Your Honor, please. I do not

think this witness can tell what Mr. Rudder knew.

The Court: Objection sustained. It is obvious if he

were not there he could not have participated in it.

Mr. Simmonds: All right.

The 'Court: Objection sustained.

15

By Mr. Simmonds:

Q. Mrs. 'Campbell, in the spring of 1961, pursuant to

state law did the Board consider an attendance area map

for the distribution of pupils in the County? A. Yes.

Q. And do you know what was done prior to the' time the

School Board adopted that attendance area map? A.We

held public hearings. These were advertised as public

hearings so that the citizens could come and look at the

maps. The maps were there. We had many citizens who

came in and talked about it because people do not like to

change their attendance areas.

Q. Do you know whether there was any objection at any

of these public meetings to the Hoffman-Boston attendance

areas? A. There was not to my knowledge.

Q. Were you present at those meetings? A. I was

present.

Q. Now, in connection with making changes in the at

tendance area maps, what is the policy with respect to

changing those lines or not changing them, Mrs. Campbell?

A. First of all, we change as few as possible because people

don’t like to change their schools. Most of them don’t. So,

we make as little change as possible and that has always

been the policy.

Q. But, at that meeting there was no objection to making

the Hoffman-Boston District as it is shown on the map as

it is in evidence today? A. No, sir.

Mr. Simmonds: That is all the questions we have at the

present time.

Cross Examination

By Mr. Beeves:

Q. You say that you were a member of the School Board

in 1949, that was your first term? A. Yes, I was elected

to the School Board.

Q. Do you recall, Mrs. Campbell, how much personal

knowledge or personal participation you had in the drawing

16

of the school zones at that time? A. Well, I had a great

deal.

Q. You did. You worked with the superintendent? A.

The superintendent had the map of the schools that were

then located. When we began to talk about building the

new schools for increased enrollment then the new school

board had participation.

Q. Who did the actual drawing, the Board or the super

intendent? A. The superintendent.

Q. He did the drawing merely submitted to the Board

for approval? A. That is right.

Q. So that you personally did not draw any of the lines?

A. No, sir.

Q. Do you know of your own personal knowledge whether

the lines as drawn in 1949 represented any change between

then and as they were originally conceived and drawn? A.

I wouldn’t know because Mr. Kemp, the superintendent,

had all of these district lines in his head and we ask him

to put them down.

Q. So, you don’t know whether they represented any

change from the time they were originally drawn? A. No,

sir.

Q. You stated, I think, that in drawing the lines or im

proving or approving the drawing of lines— A. Yes.

Q. —that the members of the school board had in mind

these criteria of capacity of school, accessibility, transpor

tation and safety of pupils? A. Yes, sir.

Q. You also stated, I believe, that in addition to these

criteria as applied to the Negro schools there was a neces

sity of course that Negro students where they live attend

the schools? A. We were in an integrated, segregated

system, Mr. Reeves, as you know, so the question was not

raised.

Q. So, then the question of whether or not these schools

were also accessible to the Negro student was not in issue

either? A. No, sir.

Q. Or whether capacity— A. Capacity in the elementary

schools was quite an issue.

17

Q. But, not in the Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High?

A. Yes, that was issue there, too.

Q. Under the segregated system, did you. discuss any

alternatives in the event there was not adequate capacity?

The Court: Are you talking about 1949?

Mr. Beeves: 1949, sir.

The Witness: No.

By Mr. Beeves:

Q. So, then the Hoffman-Boston was in whether or not

in the light of the segregated system so far as Negro stu

dents were concerned, Negro high school and junior high

school? A. Mr. Beeves, if you knew the story in Arlington

you would know one of the first things that we did was to

improve the facilities at Hoffman-Boston and to make Hoff

man-Boston the right capacity for the number of Negro

students. This was one of the first things that the Board

did.

Q. Whether they lived within the boundaries or not?

A. Yes. Well, the Hoffman-Boston School was the school

that was the high school for the Negroes in the segregated

system.

Q. Whether they lived within the lines drawn around

that school or not? A. Oh, yes. Actually there was only

one Negro high school.

Q. As a matter of fact, the area in which it was located

and around which the lines were drawn was also with the

exception of this North Hoffman-Boston District the area

in which the majority, if not all the Negroes in Arlington

County, resided at that time, is that correct? A. No, sir.

I live in North Arlington and as I remember it, there was

a large community in Halls Hill because we have the Lang

ston School there.

Q. I am saying with the exception of the area that pre

viously was called North Hoffman-Boston which was Halls

Hill area the line as drawn around Hoffman-Boston School

itself encompassed the geographical area in which most of

18

the Negroes in Arlington then lived with the exception of

those in this other? A. I think so.

Q. Do you know whether Mr. Rudder was with the school

system in any capacity in 1949? A. No, he was not.

Q. Do you know when he came? A. I just don’t know

the year, but—

Q. Was it while you were still on the Board? A. Yes,

I was still on the Board, I think it was 1955, 56.

Q. 'Could it have been 1952 as he testified? A. Well, he

was the superintendent. He was the superintendent—I

mean the principal of Washington and Lee High School,

you see.

Q. iSo, he was in the school system? A. He was in the

school system hut the principal of Washington and Lee

High 'School is the principal of Washington and Lee High

School.

Q. Agreed. But, he is an officer in the school system?

A. Yes.

The Court: As principal, he has no responsibility inso

far as the administrative policy is—of the school are con

cerned, isn’t that correct?

The Witness: No, indeed.

By Mr. Reeves:

Q. But, as principal he would not have knowledge of the

administrative policies? A. Not necessarily. Of certain

ones. Not in the general lines that the school hoard and

the superintendent of schools have.

Q. Would he have knowledge of them? A. No, sir.

Q. As it applied to him in the administering of one of

the schools? A. He would have knowledge of what was

necessary for his administration, Mr. Reeves.

Q. This notice that you say went out prior to the 1961

meeting, do you know by whom that notice was sent out?

A. It was advertised in the papers. It was sent out to the

P T A ’s.

Q. My question is: Do you know by whom? A. It was

authorized as a public meeting.

19

Q. My question is do you know by whom in the school

administration the notice was sent out?

The Court: You mean who authorized it?

Mr. Beeves: No. Who actually sent it out.

The Witness: The School Board sent it out.

By Mr. Beeves:

Q. Do you know by whom it was sent out?

The Court: You mean the individual person?

Mr. Beeves: That is right.

The Witness: I couldn’t.

By Mr. Beeves:

Q. Do you know by whom it was prepared? A. Yes.

Q. By whom? A. It was prepared by Mr. Bogy in Beed’s

office I imagine. That is the way all our notices are done.

I can’t say specifically, Mr. Beeves. There was no differ

ence between this notice and any other notice.

Q. Do you know what the notice stated? Do you know

it stated that one of the considerations to be determined at

these public hearings was approval of attendance areas, do

you not? A. That was the purpose.

Q. That was included in the notice? A. That was the

only purpose of the hearings.

Q. Did you see such a notice in any publication yourself?

A. I think that I could say that I saw it in the Northern

Virginia -Sun, Mr. Beeves.

Q. As you recall seeing it, did it include reference to

the fact that the attendance areas would be— A. That was

the only purpose.

Q. I am asking if you recall what you saw that was in

there. A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know whether it was a paid advertisement?

A. No, sir.

Q. You don’t know? A. It was not.

Q. It was not. Was this then, so far as you know, just

a story based on an announcement by someone in the school

20

board? I am trying to get the form of this notice, Mrs.

Campbell, if you know. A. Yes.

Q. The reason I am asking that is because some of the

people associated with this case have no recollection of

having seen it. A. I see. I can tell you that Mrs. Hume

was there at the meeting and protested that she did not