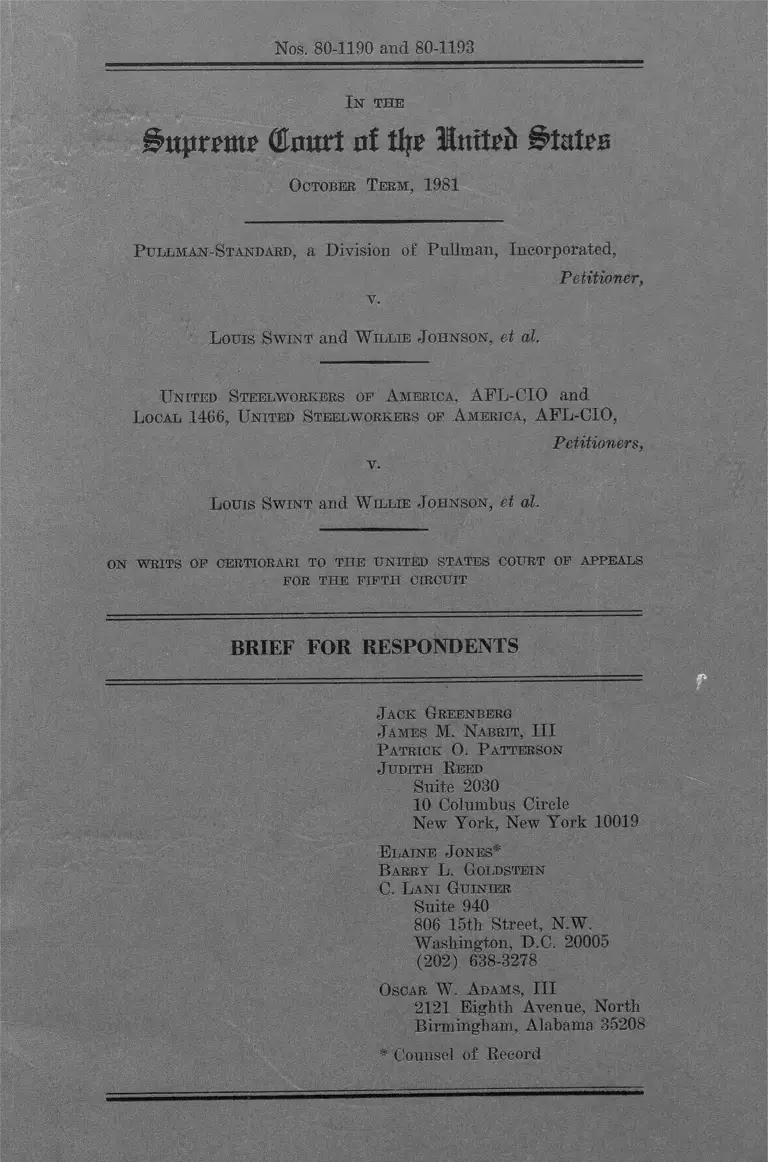

Pullman Standard Incorporated v. Swint Respondent's Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pullman Standard Incorporated v. Swint Respondent's Brief for Respondents, 1981. 6824a4ab-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b9353368-8c71-4c3b-addb-be7b1f40dd06/pullman-standard-incorporated-v-swint-respondents-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 80-1190 and 80-1193

In the

l$uprem£ (Emul nf tlj? lutteft States

October Teem, 1981

Pullman-Standard, a Division of Pullman, Incorporated,

v.

Petitioner,

Louis Swint and W illie Johnson, et al.

United Steelworkers of A merica, AFL-CIO and

L ocal 1466, United Steelworkers of A merica, AFL-CIO,

Petitioners,

v.

L ouis Swint and W illie Johnson, et al.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

■ ■ ...... — - ^

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Patrick O. Patterson

Judith Reed

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Elaine Jones*

B a r r y L. G o l d st e in

C. L ani O u in ie r

Suite 940

806 loth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-3278

Oscar W. A dams, III

2121 Eighth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35208

* Counsel of Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities ............... iv

STATEMENT OF CASE .................. 1

A. Proceedings .............. 1

B. Facts ................. 11

1. Racial Policies of the Company and

Union, ................ 12

a. Pullman-Standard .. 12

b. Steelworkers ...... 14

c. Machinists ....... 20

2. Recognition of Unionsand Plant Division .... 24

a. Structure Prior to

Union Certifica

tion ............. 24

b. Certification of theBargaining Units .. 25

3. Development of the

Seniority System ..... 34

Page

l

Page

a. Division of Bargain

ing Units ........

b. Application of the Seniority System With

in the Steelworkers'Bargaining Unit , . . 37

4. Operation of the Senior-

ity System After 1956 4~5

5. Racial Impact ... 49

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ......... . 57

64

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT CORRECTLY HELD THAT THE SENIORITY SYS

TEM WAS INTENTIONALLY DISCRIMINATORY AND THEREFORE WAS

NOT PROTECTED BY § 703(h) ..

A. Section 703(h) must be interpreted and applied in a

manner which is consistent

with the history and pur

pose underlying Title VII ..

B. The seniority system was notbona fide, and differences in

treatment thereunder were the

result of intentional dis

crimination ............ * •

11

Page

1 . Burden of Proof ...... 85

2. Racial Practices ofDefendants ............. 87

3. Development and Maintenance of the Senior

ity System ............. 91

4. Application of the Senior

ity System and its

Effect ............ 108

5. Rationality of the Seniority System NLRB ... 119

II. THE FIFTH CIRCUIT PROPERLY EXERCISED ITS APPELLATE FUNCTION

TO CORRECT ERROR BY A DIS

TRICT COURT ................ 136

CONLCUSION ........................... 152

Appendix A, Tables -1-3

Appendix B

- iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Page

Abbott Laboratories v. PortlandRetail Druggists Ass'n., 415

U.S. 1 ( 1 976) .............. 76

Aetna Iron and Steel Co., 35

NLRB 136 (1 941) ........ . 129

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,422 U.S. 405 (1 975) ......... 79,85

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

Company, 415 U.S. 36

(1 974 ) ................ . 125

Arlington Heights v. Metropoli

tan Housing Development

Corp., 429 U.S. 252(1977) ............. 59,82,84,88,92,93,105,106,112

Barnes v. Jones County SchoolDistrict, 554 F.2d 804 (5th

Cir. 1 977 ) .................. 93

Baumgartner v. United States, 322U.S. 665 ( 1 944 ) ............. 137

Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S.

Brashear Freight Lines, Inc.,13 NLRB 191 (1939) ....... 151,127

IV

Cases:

Page

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 583 F.2d 243(6th Cir. 1 978) .......... 149

Brown v. Gaston County DyeingMachine Co., 457 F.2d 1377

(4th Cir.), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 982 ( 1 972) ........ 84

California Brewers Association v.Bryant, 444 U.S. 598

( 1 980) ...................... 58,75

Carter Manufacturing Co., 59

NLRB 804 (1944) ............ 131

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S.482 (1977) ............ 51,52,90,109,113

Christopher v. State of Iowa,

559 F.2d 1135 (8th Cir.1 977) ..................... 137, 141

City of Mishawaka, Ind, v. Am.Electric Power Co., 616

F.2d 976 (7th Cir. 1980) --- 142

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446U.S. 55 ( 1 980) ............. 93

Coleman Co., 101 NLRB 120(1 952) ..................... 129

Columbus Board of Education v.Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) .............. 88,93,105,113

v

Page

Corning Glass Works v. Brennan,417 U.S. 1 88 (1 974 ) ...... 86

County of Washington v. Gunther,49 USLW 4623 (1981) --- 60,74,77,86,87

Dayton Board of Education v.Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526( 1 979 ) ............. . 93 , 105, 1 13,1 50

Detroit Police Officers Ass'n v.Young, 608 F.2d 671 (6th Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 101 S. Ct.783 (1 981) ........... ...... 66,141

District of Columbia v. Pace,320 U.S. 698 ( 1 944 ) ......... 140

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,424 U.S. 747 (1976) ..... 58,73,77,78

Galena Oak Corp. v. Scofield,218 F.2d 217 (5th Cir.

1 954 ) ....... ............... 137

Georgia Power, 32 NLRB 692(1941) ..................... 130

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401U.S. 424 ( 1 971 ) ............. 81 , 85

Group Life and Health Insurance Co. v. Royal Drug Co.,440 U.S. 205, (1979) --- 76

vi

Page

Hazelwood School District v.United States, 433 U.S. 299

( 1 977 ) .................. 50

Handy-Andy, Inc., 228 NLRB 447(1977) .....................

Hughes Tool Co., 147 NLRB 1573 (1 964) ................. .

International Brotherhood ofTeamsters v. United States,

321 U.S. 324 (1977) ........

James v. Stockham Valves and Fittings Co., 559 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert,

denied, 434 U.S. 1034

(1978) .....................

Jennings v. General Medical Corp., 604 F.2d 1300 (10th Cir.

1979) ......................

Karavos Compania, etc. v.Atlantic Export Corp.,

588 F.2d 1 (2d Cir. 1 978) . .

Kelley v. Southern Pacific Co.,419 U.S. 318 (1974) .....

Keyes v. School District No. 1,413 U.S. 189 (1973) .... 61,88

Kunda v. Muhlenberg College,621 F.2d 532 (3d Cir.

1980) ......................

,51,52,

109,113

130

130

passim

68

141

137,140

136,145

,93,113

142

Vll

Larus and Brother, Co,, 62 NLRB1075 (1945) ............... 127,129

Lee v. Washington County Boardof Education, 625 F.2d 1235

(5th Cir. 1 977) ............ 93

Levin v. Mississippi River Fuel Co., 386 U.S. 162

(1 967) .............. . 151

Manning v. Trustees of ufts

College, 613 F.2d 1200

(1st Cir. 1 980) ............ 142

Matter of U.S. Bedding, Co., 52NLRB 382 ( 1 943 ) ............ 1 28, 1 29

Norfolk Southern Bus Corp. 76NLRB 488 (1 948 ) ............ 129, 130

Orvis v. Higgins, 180 F.2d 537(2d Cir. 1950) ............. 141

Pacific Maritime Association,112 NLRB 1280 (1956) ........ 128

Piedmont & Northern R. Co. v.ICC, 286 U.S. 299 (1932) --- 76

Personnel Administrator ofMassachusetts v. Feeney,

422 U.S. 256 (1979) ...... 82,112,121

Peyton v. Rowe, 391 U.S. 54,( 1 968 ) ................. 76

Page

viii -

Page

Poyner v. Lear Siegler, Inc. 549F.2d 955 (6th Cir. 1976) --- 141

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc.,279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va.

1 968 ) ...................... 69

Resident Advisory Board v.

Rizzo, 564 F.2d 126 (3dCir. 1 977 ) ........... ..... 93, 1 05

Schultz v. Wheaton Glass Co.,

421 F.2d 267 (3d Cir.1 970 ) ...................... 137, 141

Sears v. Atchison, T. & S. F.Ry., 645 F.2d 1365 (10th

Cir. 1981) ................. 67

Sears, Roebuck and Co. v. Johnson,

219 F.2d 590 (3d Cir.

1954) ...................... 141

Sidney Blumenthal & Co. v.Atlantic Coast Line R. Co.,139 F.2d 288 (2d Cir. 1943),

cert, denied, 321 U.S. 795

( 1 944 ) ........'............ 136

Stewart v. General Motors Corp.,542 F.2d 445 (7th Cir.

1 976 ) ........... 141

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100U.S. 266 (1 880 ) ........... 93

IX

Page

Sweeney v. Board of Trustees of Keene State College, 604

F.2d 106 (1st Cir. 1979),

cert, denied, 444 U.S.

1045 (1980) ................

Taylor v. Armco Steel Corp., 429F.2d 498 (5th Cir. 1970) --- 125

Terrell v. U.S Pipe & Foundry Co.,

644 F.2d 112 (5th Cir.

1981 ) ....................... 69

Union Envelope Co., 10 NLRB1 147 (1 939) ................. 130

United States v. Bd. of School Commr's of Indianapolis,

573 F.2d 400 (7th Cir. )

dert. denied, 439 U.S. 824

(1 978) ..................... 83,84

United States v. City of Chicago,549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir.),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 875

( 1 977) .............. ....... 1 41

United States v. First CityNational Bank, 386 U.S. 361

(1 967) ..................... 86

United States v. General Motors

Corp., 384 U.S. 127(1 977 ) .............. . 10,136,139,150

x

Page

United States v. Georgia Power Co.

634 F.2d 929 (5th Cir.1981), cert. pending

Electrical Workers Local No.

84 v. United States, 50 USLW 3080 (Aug. 25, 1981) ...

United States v. Jacksonville

Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971 ) ,

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 906 (1 972) ........ .............

United States v. Oregon StateMedical Society, 343 U.S 326

(1952) ..................

United States v. Parke, Davi: 362 U.S. 29 (1960) .........

United States v. Public Utilities

Commission, 345 U.S. 295

(1953) .....................

United States v. Singer Manufac

turing Co., 374 U.S. 174

(1963) ...................

United States v. Texas Education

Agency, 564 F.2d 162 (5th

Cir. 1977), cert, denied,

443 U.S 115 (1979) .........

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S 364

(1948) ............... ....

69

47

146

& Co., 63,136

77

138, 139

121

138,140

xi -

Page

United States v. Yellow Cab Co.,338 U.S. 338 ( 1 949) ......... 146

United Steelworkers of America

v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193(1979) .................. 21,65,71,77

Utah Copper Co., 35 NLRB1295 (1 941 ) ................. 129

Veneer Prods, Inc., 81 NLRB 492

(1949) ......*..............

Washington v Davis, 426 U.S 229(1 976) ............. 62,84, 1 1 2, 1 13

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S 49(1 949) ..................... 135

Statutes and Rules:

National Labor Relations Act, 29

U.S.C. §§ 151, et. seg......

42 U.S. C. § 1981 .........

Title VII of the Civil Rights Actof 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e, et

seg. ...

§ 703(h)

3,4,74,76,80

.... 64,80

Rule 52(a), Fed. R. Civ.

P. .................. 135,137,138,142

xii -

Page

Legislative History:

110 Cong. Rec.................. 72,73,82

Legislative History of Titles

VII & XI of Civil Rights

Act of 1 964 ............... 70

Hearings on Equal EmploymentOpportunity Before the Sub

c omm • on Employment and Man-

power of the Senate Comm.

on Labor and Public Welfare

88 Cong.,

(1963) ..

1st Sess. 70

Hearings on equal Employmentopportunity Before the General

Subcomm. on Labor of the

House Comm, on Education &

Labor, 88 Cong., 1st Sess.

(1 963) ..................... 70

Hearings on Civil Rights Before Sub omm. No. 5 of the House

Comm, on the Judiciary, 88th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) .... 70

Annual Reports - Federal Agency;

7 NLRB ANN. REP. (1942 ) ... 127

8 NLRB ANN REP. (1943) ...... 127,132

9 NLRB ANN. REP. (1944) ...... 127

xiii -

Page

Other Authorities

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority andTesting Under Fair Employment

Laws: A General Approach to Ob

jective Criteria of Hiring

and Promotion, 82 HARV. L. REV.

1598 ( 1 969) ........................................ 78

Cox, The Duty of Fair Representation,

2 v i l l . L. Rev. 151 ( 1957) . . . 130

Gould, Black Workers in White Unions 81977) .........

Harris, The Black Worker (Atheneum ed. 1974) .............................................

Hill, Black Labor and the American Legal System: Race, Work and

the Law ( 1977) .................................

Karson and Radosh, The American Federation of Labor and the

Negro Worker, 1894- 1949 in

J.Jacobson, ed. The Negro

and the American Labor

Movement (1 968) .................... ..

King and Risher, The Negro in the Petroleum Industry

( 1969) .................. ..................................

Marshall and Briggs, The Negroand Apprenticeship ( 1967) . . .

15 , 65

65

65 , 68

21

68

65

- xiv -

Page

R. Marshall, The Negro and Organized

Labor ( 1 965) .......... .......

Myrdal, An American Dilemma(Harper & Row ed.

1962 ) .......................

Northrup, Organized Labor and the

Neqro (1944) ............ . 21 ,65

Northrup, The Neqro in the PaperIndustry (1969) .............. 68

H. Northrup, The Neqro in theRubber Industry (1969) ..... 68

H. Northrup. The Neqro in theTobacco Industry (1970) .... 68

Note, Discrimination in Union Membership, 12 Rutgers L. 130

Rubin, The Neqro in the Ship-building Industry at 115-16

( 1 979 ) ...................... 68

Sovern, Legal Restraints on Racial Discrimination in Employment

11 966) ..................... 70

Sovern, The National Labor Relations Act and Racial Discrimination,

62 Colum. L . Rev. 563

(1 962) ........................ 130

xv

Page

Spero and Harris, The Black

Worker (Atheneum ed.

( 1 974 ) ................. . 67

Weaver, Negro Labor, A NationalProblem (1946) .............. 65

xvi

Nos. 80-1190 and 80-1193

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

PULLMAN-STANDARD, a Division of Pullman, Incorporated,

Petitioner, No. 80-1190,

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO and LOCAL 1466, UNITED STEELWORKERS OF

AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

Petitioners, No. 80-1193,

v.

LOUIS SWINT and WILLIE JOHNSON, et al.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals

For The Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

STATEMENT OF CASE

A. Proceedings

This employment discrimination case

2

was filed as a class action against

Pullman-Standard, the International Asso

ciation of Machinists and its Local 372 and

the United Steelworkers of America and its

Local 1466. The Bessemer, Alabama plant of

the Pullman-Standard Company, the plant

which is the focus of this lawsuit, has1/been closed permanently.

This case has been tried three

times and has resulted in three district

court and two appellate court decisions.

Only the third trial concerned the issue,

the bona fides of the seniority system,

before this Court.

The original complaint was filed on

October 19, 1971, pursuant to Title VII

_]_/ Accordingly, the issue of appropriate injunctive relief in this case is now moot,

since no employee works at the plant. The

case is not entirely moot since the class

of black workers seeks monetary relief for

earnings lost as a result of the discrimi

natory seniority system.

3

of the Civil Rights Act of 1 964 , 4 2

U.S.C. §§2000e et seq. and the Civil Rights

Act of 1 8 66 , 4 2 U.S.C. §1981. App.

2/1-2. In the original complaint, the

claims of discrimination were made against

the Pullman-Standard Company and the United

Steelworkers of America and its Local 1466,

the bargaining representative of the

majority of production and maintenance

employees at the Bessemer plant. The

complaint was amended in order to name the

International Association of Machinists and

its Local. JA 14-25.

At the pre-trial conference on June 4,

1974, the district court granted leave to

add the Machinists as a defendant -'inso

far as the relief requested may involve or

2/ References are made to the opinions of the lower courts reproduced in the Appendix

to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

submitted by the Steelworkers.

4

infringe upon the provisions of such

Union's collective bargaining agreement, it

being noted, however, that no request for

monetary relief is being sought against

3/said Union." JA 29. The pre-trial

Order further included as a trial issue the

plaintiffs' claim that the seniority system

unlawfully perpetuated discrimination

because, inter a 1 i__a, the "rights of

transfer do not apply to jobs . . . repre-

1/ .sented by the IAM. " Id_. At the

3/ Also, the district court determined "that this action may hereafter be main

tained on behalf of all black persons who

are now or have (within one year prior to

the filing of any charges under Title VII)

been employed by defendant Company as

production or maintenance employees rep

resented by the United Steelworkers." JA

28; see App. 124, n.20. The first EEOC

charge which alleged a discriminatory

operation of the seniority system and

discriminatory job assignments was filed on

March 27, 1967. App. 50 n.5.

4/ The Company erroneously maintains

that the district court limited the senior

5

opening day of trial, the district court

noted that Local 372 of the Machinists "is

the certified labor union at Pullman-Stan

dard" and granted leave to add Local 372

as a defendant "for the limited purpose

that a part of the relief sought by

the plaintiffs may involve some modifica

tion to the collective bargaining agreement

between the Machinists and the defendant

company." JA 31. The I AM and Local 372

were represented by counsel throughout the

5/district court litigation.

4/ Continued

ity issue to "the system ... in the Pull

man USW contract." Brief 3. The Steel

workers wrongly state that the issue

before this Court is "that the system

maintained by the Company and USW violated

these [fair employment] laws." Brief 3.

5/ In the district court, Mr. Falken-

berry, formerly a member of one of the firms representing the Steelworkers

before this Court (JA 28, 41), represented

the I AM and its Local 372 as well as the

6

The initial trial, covering 16 days in

1974, proceeded "on the theory ... that a

violation of Title VII could be shown by

proof of a neutral seniority system which

perpetuated the effects of pre-Act dis

crimination. Trial was conducted on such a

limitation of issues, w_i t h consequent

t._ioji by_ plaintiffs to possible

evidence showing the seniority system to

have been instituted or maintained contrary

to Section 703(h)," (emphasis added). App.

46-47. In its September 1974 decision,

the district court held that "[w]ith the

limited exception of expanding somewhat

eligibility to transfer rights ... the

various claims and items of relief sought

5/ Continued

Steelworkers and its Local 1466. The IAM and its Local 372 were joined for injunc

tive relief only? apparently because this

issue is now moot, these defendants have neither filed a brief nor entered an

appearance in this Court.

by plaintiffs are due to be denied." App.

153-154.

In a unanimous opinion, the Fifth

Circuit (Coleman, Clark, Gee, JJ.) held

that the district court had misapplied the

appropriate legal standards and had commit

ted "patent inaccuracies" in its factual

analysis. App. 89. The Court defined

the nature of the "prima facie inquiry" on

remand in order "to eliminate the likeli

hood" that "[ejrrors apparent in prior

proceedings" would "recur on the recon

sideration we now mandate." App. 90.

In February 1977, the district court

held a two-day remand proceeding devoted

primarily to the introduction of additional

evidence regarding the assignment of

employees, promotion of supervisors and

statistics. The district court delayed

ruling "in anticipation" of the Teamsters

- 7 -

8

decision. App. 48. Before the parties

had an opportunity to present evidence

pursuant to the standard for defining a

bona fide seniority system prescribed by

Teamsters, the district court held that the

seniority system was lawful pursuant to the

Teamsters standard. App. 51-58. The

district court also ruled that Pullman-

Standard had not discriminated in its

selection of supervisors and, reversing

its own 1974 finding, that after December

1966 the Company had not discriminated in

making job assignments. App. 53-66.

Having had no opportunity to present

evidence relevant to the standard estab

lished by Teamsters, the plaintiffs

6/moved for a new trial. After grant-

6/ The plaintiffs also requested that the district court produce a "chart" which

it had developed and upon which it relied.

App. 53. The district court refused,

App. 124, and the chart remains secret.

9

ing the motion, the court heard two wit-

nesses at a short hearing lasting less than

2/three hours. However, voluminous docu-

6/ Continued

While the district court stated that the chart need not be produced, inasmuch as it

merely summarized evidence already in the

record, App. 45, the court of appeals

found that there were unexplained and

unexplainable inconsistencies between the

district court's factual statements based

on the secret chart and the record exhibits

upon which the chart was supposedly con

structed. App. 7.

7/ Only the plaintiffs called witnesses. Mr. Samuel Thomas, a black employee

at the company since 1946, testified as

to segregation in seating at the union

hiring hall and at union-sponsored social

activities as well as the racial composi

tion of union officers and negotiators.

The other witness Mr. Willie James Johnson, also a long-time black employee, testified

regarding the segregation at the Company

and union hall, the racial identity

of various International Representatives

and the handling of grievances regarding

racial discrimination. Neither witness was

subjected to extensive cross-examination

and neither petitioner attacks the credi

bility of these witnesses. Transcript

1-67 (1978 Trial).

1 0

mentary evidence” was introduced regard

ing the development and maintenance of the

seniority system from 1940 through the

1970s. After reviewing this "paper"

1/record the district court held that the

seniority system "is ’bona fide' and

that the difference in terms, conditions or

privileges of employment resulting there

under are 'not the result of an intention

to discriminate' because of race or color,"

App. 44.

The Fifth Circuit (Wisdom, Roney,

Hatchett, JJ.) once again unanimously

reversed the district court. The appel

late court ruled that the lower court had

improperly applied legal standards, and

8/ The respondents introduced 112 exhibits and the Company and Unions intro

duced 27 exhibits.

9/ See United States v. General MotorsCor£. , 3 8 4 U . S . TTT, TTT n 71 "6 (1 966).

that "[a]n analysis of the totality of the

facts and circumstances surrounding the

creation and continuance of the depart

mental system at Pullman-Standard leaves us

with the definite and firm conviction that

a mistake has been made," (footnote omit

ted). App. 15. The Fifth Circuit also

reversed the lower court's rulings that the

Company had neither discriminated in the

selection of supervisors nor in post-1966

job assignments, App. 7-8, 16-21. The

Company's petition for a writ of certiorari

was denied insofar as it sought review of

the Fifth Circuit's ruling regarding the

selection of supervisors and the assignment

of employees.

B. Facts

Overview. The proper presentation of

the legal issue in this case requires a

description of the general racial policies

12

of the defendant Company and Unions, the

accumulated racial impact of the decisions

made by the defendants in developing the

seniority system, and the specific racial

impact of particular decisions made by the

defendants. The evidence demonstrates that

each of the defendants had blatantly racist

policies, that the overall impact of the

seniority system had substantially adverse

consequences for black workers, and that

specific decisions made by the Company and

Unions tended to segregate further the

plant and to limit the job opportunities of

black workers.

1 . Racial Policies of the Company

and Unions

a. Pullman-Standard. The evi

dence is undisputed that the Company

considered the race of an employee in

practically every decision which it made in

its Bessemer plant:

13 -

Both in 1941 and in 1954, racial segregation was extensively practices

at the Company's Bessemer plant

.... Bathhouses, locker rooms, and

toilet facilities were racially

segregated. J_0/ Company records --

including employee ^rosters, 11/internal

correspondence,12/ records of negotia

tion sessions ,J_3/ list of persons

picketing 14/ included racial designa

tions. In 1941 some of the "mixed"

jobs even had different wage scales

for whites and blacks. 15/ All company

officials, supervisors and foremen

were white ... (Footnotes added).

App. 39, 13.

10/ The facilities remained segregated

until 1967. JA 97.

1 1 / Employee identification numbers

between 100 and 199 and between 300 and

1 999 were given to black employees and

employee identification numbers between 200

and 299 and 2000 and above, were given to white employees. JA 104? see Record,

plaintiffs' exhibit 1 (1978 Trial).

12/ See e.g., JA 209-11, 220-11, 220-21,213-27.

U / See e.g., JA 208, 212-13, 222, 254,256, 268, 270.

14/ See e.g., JA 219, 224-27, 255.

15/ JA 216-17, 220, 223, 252-53.

14

The jobs at the plant were segre-

16/gated: "Most of the jobs at the plant

were by custom treated as 'white only' or

'colored.'" App. 39. At least until 1971

the Company maintained its discriminatory

I Vjob assignment policies. App. 162 63.

b. Steelworkers. As did the

Company, the Steelworkers operated on

16/ "Pullman's old records, quite incom

plete, do reflect a mixing of the races in

some of these jobs in the 1920's and 30's.

Nonetheless, it is clear that by the late

40's many of the jobs had become racially

segregated ...." App. 121 n .12 , 71.

17/ As a result of an arbitration decision

in March 1965 the practice of job segrega

tion was breached. App. 55. This decision

applied to one job, rivet driver. While it

provided a "ground breaker" for ending

strict job segregation, JA 53, the discrimination in job assignments did not

end, as the Steelworkers allege, with the

March 1965 arbitration decision. Brief 6, nn.9, 15. Both the district court in its

1974 decision and the Fifth Circuit in its

most recent decision concluded that dis

criminatory job assignments continued after

the March 1965 decision. App. 54-55.

15

1 8/a segregated basis. "[R]acial segrega

tion was extensively practiced ... in the

local union hall . . . Union meetings were

conducted with different sides of the hall

I Vfor white and black members, and social

18/ The Steelworkers stress that their

"performance in general" was supportive of

the economic rights of black workers.

Brief 10 n.20. But see, W. Gould, Black

Workers in White Unions at 397 (1977). It

is not the general performance of the

Steelworkers that is at issue in this case?

rather, it is their practices at the

Bessemer plant. As shown in the discussion

in this section, the practices of Local

1466, Steelworkers, divided and segregated

the membership during the period of the

development of the seniority system.

19/ The Union maintained segregated seating at meetings until the first trial

in this case in 1974. JA 92-93. The Union

president, Mr. Henn, "said [the black

workers] there is a white side and a black

side." JA 94. The Steelworkers' assertion that "the record is not clear" as to

whether [the segregated seating was] by

mandate or personal choice," is error.

Brief 12, n. 21.

16 -

functions of the union were also segre

gated." (Footnote added) App. 39. The

Union maintained segregated restroom

facilities in the meeting hall until

20/1967, and only integrated its facili

ties at the same time that the Company

integrated its facilities. JA 96-97.

Since 1940 blacks have constituted

a significant proportion of the membership

of Local 1466 and blacks have served in

certain officer positions. However,

it is apparent that until 1970 black

workers occupied only two elected posi

tions, Vice-President and Financial Secre

tary, while white workers occupied the

other three positions, President, Trea-

20/ The Steelworkers concede that there were "separate washrooms at the local union

hall into the 1960's." Brief 12.

surer, and Recording Secretary. More

importantly, during the the 1950s and early

1960s white union officials dictated that

racial grievances would not be prosecuted,

and black union officials would acquiesce

by agreeing that "it wasn't time for

12/

it."

- 17 -

21/

21 / Company Exhibit 309 shows this division of positions from 1965 through

June, 1970. JA 69-80. Furthermore,

uncontested testimony makes clear that

the same racial allocation of positions

existed in 1946, JA 51-52, that "in the

fifties there were blacks who served as

vice president and secretary", JA 94, and

that the first black served as President in

1970. JA 98.

22/ Willie Johnson, a black steward in the Paint Department from 1967 through 1973

testified as follows:

"A. In '63. And we had questioned

the president about segregated job assign

ments at the plant. And he would always tell us, well, we have got white [32] jobs

because you're going to stay on the black

jobs, and the whites are going to maintain

the white jobs. So about March of 1963,

1 8

The Steelworkers

"the 1940's the Union

assert that during

maintained the ob-

22/ Continued

thirteen black employees were dropped, laid off, I mean, and thirteen junior whites

remained in the plant. So we thirteen

black employees filed a thirteen grievance

saying the company was discriminating.

And when we came to the union meeting

that Tuesday night, the president, when

he called the meeting to order, he had

the thirteen grievances. And he held

them up in his hand, and he said, I have

thirteen grievances here, racial grievances

that have been filed by thirteen black

employees out in the plant against the

company. And he criticized those thirteen

black employees for filing such grievance.

And I want the rank and file to tell me

whether or not to tear these grievances

up or process them. Well, one white man

got up and made a motion that he tear

them up. But we had the majority that

night of blacks, and we voted it down,

and made a motion to process the griev

ances. And we did win the vote. But the president did not process the grievances.

And later we went to the National Labor

Relations Board and filed discrimination

charges there. At that same night the

secretary was Gus Dickerson. [33],

Q. Was Gus Dickerson a black man?

ject of removing the inequity of black

workers being paid less than whites for

the same job." Brief 12, n. 21. This

objective was advanced at one meeting, JA

216-17; the Company's documents make clear

however that it was the black workers in

Steelworkers Local 1466 who were advancing

this matter with little support from the

22/ Continued

A. Yes, he was a black man. But he

got up and told us he was not going to

process a racial grievance. It wasn't time

for it, and he wasn't going to do it.

Q. In your occupation as a member of

the union during the fifties and early

sixties, Mr. Johnson, did the black union

officials press racial grievances or

complaints of racial grievances at this

time?

A. No. They would always say there

wasn't time for it." JA 97-98.

The evidence contradicts the Steelworkers' assertion that "on no occasion did the vote on contract proposals divide along

racial lines." Brief 12, n. 21.

20

white union members. For example, a 1945

Company memorandum indicates that

there is now a very active movement

on the part of the colored to push

themselves to a point of doing the

same job as the white man. This has

been confirmed to me by the fact that

representatives of the C.I.O. have

stated to me [W. C. Sleeman, a company

official] that they are having trouble

all over the district with their

colored membership to the extent that

in some of the plants numbers of the

colored have walked off the job.... We also know that in numerous meetings we

have had recently the colored represen

tation always inject negro differen

tials and that they should be permit

ted to have negro leaders over the negro

man. JA 216-17. 23/

c. Machinists. During the period

when the Machinists' bargaining unit was

defined at the Bessemer plant, 1940 through

23/ Similarly, in a 1951 Company Memorandum, a manager observes that " [w]e are

inclined to think that the committee as a

whole, with the exception of the colored,

are not so interested in the wage inequity

program as much as they are in a good

21

1944, see section 2. b, infra, the Machin

ists through their Ritual limited member

ship to "qualified white candidates." JA

24/348, 350. At the 1941 NLRB hearing

regarding union representation at the

Bessemer plant, a representative of the

23/ Continued

substantial increase in money." JA 223. Also another Company Memorandum indicates

that after a Company offer was made during negotiations for the 1 947 agreement "sev

eral of the colored objected to it, stating

that they wanted certain inequities correct

ed." JA 220.

24/ The plaintiffs had requested the district court to take judicial notice of

this adjudicative fact. JA 346-50.

The district court declined the request.

App. 24 n .1. In United Steelworkers

of America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 1 93, 1 98 n.

2 (1979), the Court took judicial notice

of discrimination by craft unions. See M.

Karson and R. Radosh, The American Federa

tion of Labor and the Negro Worker, 1894—

1949, in J. Jacobson, ed. The Negro and the

American Labor Movement at 155-159; (1968);

H. Northrup, Organized Labor and the Negro

at 2-3, 9-10, 254 (1944).

22

Steelworkers stated that "it is my informa

tion that they [black workers] cannot

25/

belong [to the Machinists]." JA 145.

Colon Clemons, a white employee who had

progressed from a laborer to a machinist

and then to a supervisor in the Tool and

Die Department represented by the Machin

ists, testified that he joined the Machin

ists in 1941, that there were no black

members of the Union at that time, and he

could not recall ever seeing a black at a

Machinists' meeting. JA 339-40. In 1941,

25/ The Trial Examiner halted "this line"

of questioning regarding race. The repre

sentative of the Machinists had asserted at

the hearing that the Union "claim[ed]"

"negro cranemen", JA 149, see Company

Brief 5. In fact, the only crane operator

position was located in the Steel Miscel

laneous Department, which was staffed

by a black employee, see plaintiffs'

exhibit 109 (1978 Trial), JA 243-51;

see also plaintiffs' exhibit 1 (1978

Trial). The Machinists did not seek to

have this crane operator position included

in their bargaining unit.

23

the Machinists did not petition the NLRB to

represent any jobs that were staffed by

blacks, despite the functional relationship

of such jobs to other jobs included in

their petition. Then they entered into a

series of agreements that removed all jobs

staffed by blacks which had been included

in their bargaining unit by the NLRB. See

section 2. b, infra. After this job

switch, a black worker did not enter

the Machinists' bargaining unit until

26/1970. App. 7.

26/ It appears that after 1943 four blacks

were assigned to the welder helper job in

the IAM unit. JA 255; Plaintiffs' Exhibits

2, 62 (1978 Trial). This position was not

staffed at the time of unionization, and no

blacks were in the IAM unit. JA 247.

However, in May 1 944 the job was ceded to

the Steelworkers as part of the acquisition

of three IAM departments by the Steel

workers. See n. 41 infra.

24

2. Recognition of Unions and

Plant Division

a . Structure Prior to Union

Certification. Pullman-Standard opened its

©

Bessemer plant in 1929. Until the plant

closed in January 1981, the Company built

railroad cars in Bessemer. Production of

the cars was based upon the receipt of

special orders, which could range from a

few cars to several thousand. Depending

upon the size of the orders, the number of

workers at the plant varied from several

hundred to several thousand. App. 118-19

nn.3-4, 68 nn. 2-3.

In 1941 four unions sought to repre-

27/

sent employees at the Bessemer plant.

27/ The Steelworkers sought to represent

all the production and maintenance employ

ees, while the Machinists and the Interna

tional Brotherhood of Electrical Workers

(IBEW) sought to represent specified units.

2 5

At this time the Company had approximately

1300 employees divided into twenty depart-

28/ments. Of these departments, five

contained employees of only one race.

The Lumber Yard, Welding, Template and

Plant Protection had only white workers,

and the Truck Shop had only black workers.

JA 103.

b. Certification of the Bargain

ing Units. The major focus of the 1941

NLRB hearing concerned the proposed

unit which the Machinists sought to repre-

27/ Continued

The Federal Labor Union sought to represent those production and maintenance employees

excluded by the Machinists and the IBEW.

JA 155.

28/ The "voting list" which was submitted to the NLRB listed 21 departments. JA 103.

However, one department, Sand Blast, had no

employees and does not appear on subsequent

seniority lists. The voting list racially

identifies employees. JA 104, plaintiffs'

exhibit 1 (1978 Trial).

26

sent. See JA 1 05-49. There are two

critical aspects to IAM's representational

claim: the Union sought to represent

30/production as well as craft workers

and the Union selected jobs on the basis of

the race of the job incumbents. For ex-

29/

29/ Although the district court stated that "the objective facts are not greatly

in dispute," the court failed to describe

these facts since it determined as a matter

of law that the motivation of the IAM was

irrelevant to the bona fides of the system.

App. 42. The Fifth Circuit disagreed;

"[T]he motives and intent of the IAM in

1941 and 1942 are significant in considera

tion of whether the seniority system had

its genesis in racial discrimination. The

IAM was one of the unions which unionized

the company in 1941 and the evidence

reflects that the IAM manifested an intent

to selectively exclude blacks ...." Id. ,

14. See Argument, sections B. 2 and

5. infra.

30/ The Company mistakenly claims that the IAM only sought a "craft" unit of skilled workers and apprentices and helpers ...."

Brief 3. The Steelworkers implicitly

concede that the 1941 bargaining unit

of the IAM included production jobs.

Brief 24-25 n. 39.

27

ample, the IAM petitioned for the inclu

sion of cranemen in the Die and Tool and

the Wheel and Axle departments, staffed

only by whites, but not in the Steel

Miscellaneous department, staffed with a

M /black, JA 149, 155, 170, 247, 249, 251,

and for the inclusion of handyman in the

Die and Tool department, staffed only by

whites, but not in the Maintenance depart

ment, staffed with a black, JA 1 55 , 1 70 ,

249, 250. Also, the IAM requested that the

following production jobs, as distinct from

craft jobs, be included in its unit:

"production ... welders" JA 155, 170,

31/ Plaintiffs' exhibit 109, (JA 243-51)

lists the racial composition of each job at

the time of the certification decision.

This exhibit was prepared from plaintiffs'

exhibit 1 (1978 Trial). (The cover page of

Plaintiffs' exhibit 1, a summary of the

exhibit, contains some numerical inaccu

racies, and the specific department list

ings should be examined.) The IAM did not claim all cranemen positions which were

staffed by whites. JA 241, 246, 248.

28

117, production pipe fitters, JA 155, 170,

11/see 127-29, "wheel borer", JA 136-37,

1 55, 1 70 , "tool grinder," id., and "axle

11/finisher", id. All these positions

32/ The IAM sought to represent "employees

in the air-brake department," JA 155 or, as

later amended, "air brake production

employees classified as pipe fitters, pipe

fitter helpers, and air brake testers," JA

170. The plant manager, Mr. Sleeman, testified that these air brake production

employees are "just a part of [the] ...

production line," that they are part of the

Steel Erection department, and that

"[the Company does] not classify them as

maintenance pipe men." JA 127-29.

33/ Mr. Howard, the Machinists' represen

tative, JA 106, stated that "we claim" the

employees in the borer, grinder and axle

finisher positions in the Wheel and Axle department. JA 134-37. These were

production workers. When asked whether

these employees "are machinists," the plant

manager replied "[a]bsolutely not, because

we have taken a man right from the farm,

and he is the best production man we ever

had there...." JA 137. In reply Mr. Howard admitted that the jobs being

sought by the I AM were not highly skilled:

"I also appreciate the fact that you can

take a chimpanzee and show him the opera-

29

were staffed exclusively by white workers.

JA 246-47. The IAM did not seek to include

in its unit other machine operator posi

tions, like those in the Punch and Shear

Department, JA 245, which were staffed with

black employees.

Despite the attempts of the IAM

to exclude from their bargaining unit any

jobs to which blacks were assigned, the

NLRB certification decision included jobs

staffed by black workers within the Machin

ists' unit. Since the IAM had expressly

requested some production jobs and express-

34/ly excluded only one job in the Wheel

33/ Continued

tions in some of these departments and then put him on a chain where he cannot run

away, and probably he can do that [the

job]...." Id♦

34/ Mr. Howard, the IAM representative, stated "I don't claim the hookers any-

30

and Axle department, the NLRB included in

the I AM unit all jobs in that department

and in the Truck department, JA 165-66,

which were functionally related to the

Wheel and Axle department. JA 119,

130-31. As a result 24 blacks, 14 in the

Truck department and 10 holding four jobs

in the Wheel and Axle department, JA 247,

35/

were placed in the IAM unit.

Within a month of the NLRB November

1941 certification, the Steelworkers and

34/ Continued

where." JA 149. The hooker assists

cranemen, JA 125. The Machinists sought

to represent several craneman positions,

yet they rejected inclusion in the unit

of the functionally related job of hooker.

The job was generally staffed, as in the

Wheel and Axle department, with black

employees. JA 247.

35/ The Machinists made clear to the

Company that "they do not want [these

employees]" but if necessary "they will

accept them." JA 207.

31

the IAM agreed to a swap of jobs which

removed all jobs staffed by black employees

from the I AM unit and transferred two jobs

staffed by two whites from the Steel

workers' to the Machinists' Unit. Compare36/

JA 170-71 with JA 165-66.

pany endorsed the agreement,

included in the April 1942

bargaining agreements between

and the IAM, JA 167-71, and

Company and the Steelworkers,

The Com-

and it was

collective

the Company

between the

plaintiffs'

36/ The agreement excluded crane hookers,

wheel rollers and laborers and the Truck

Shop from the IAM unit. All the 24

black employees in the designated IAM unit

were in wheel roller, wheel roller helper

or laborer positions or in the Truck

Shop. JA 247 . In return, the jobs of

toolroom man and toolroom helper in the

Steel Erection department, which were

staffed by two white employees, JA 246,

were transferred from the Steelworkers'

to the Machinists' unit.

32

Exhibit 33 (1978 Trial).

As a result of the gerrymandering of

the plant between the Machinists and

the Steelworkers, the number of one-race

departments increased from five to ten.

Of the five all-white IAM departments, Tool

and Die, Wheel and Axle, Air Brake, Mill

wrights (Maintenance), and Welders, JA 167,

all, except Welders, had included employees

37/

37/ The Steelworkers claim that this

transfer "contract[ed] ... the IAM unit

to craft and highly skilled jobs." Brief

24-25, n. 39. In fact, (1) the jobs remaining in the IAM unit were not all

"highly skilled" or "craft," see nn.32, 33,

supra; (2) the jobs removed from the IAM

unit were functionally related to those

that remained and required equal skill (see

JA 119; 130-31 describing the Truck shop

and Wheel and Axle department); and (3) the Steelworkers transferred two jobs in a

production department, Steel Erection, to

the IAM's unit, see n.36, supra. In

keeping with their policy of limiting their

membership to "white males," the Machinists

simply "did not want" the black employees,

see n.35, supra.

33

of both races prior to unionization.

In addition, to these four new one-race

departments, an all-black Die and Tool

department was created in the Steelworkers'

unit. The district court stated with

respect to the creation of two Die and Tool

and two Maintenance departments that "[n]o

similar situation exists at Pullman's

Butler and Hammond plants, and indeed there

was no such division at Bessemer prior to

unionization and seniority." App. 35. The

38/

38/ Die and Tool: The jobs staffed by

blacks, hooker, and laborer were excluded

from the IAM unit. JA 166, -1 70, 249.

Maintenance: All the jobs selected for

inclusion in the IAM unit from the Mainte

nance department were staffed by whites.

JA 166, 170, 250. Air Brake: The jobs

of pipefitter and pipefitter helper in the

heavily black Steel Erection department and

of air brake tester in the Shipping Track

department, which were staffed by whites,

were joined to form the Air Brake depart

ment in the IAM unit. JA 166, 170, 245-46,

see n.32, supra. Wheel and Axle: Jobs

staffed by whites were included in the IAM

unit; those staffed by blacks were exclu

ded. JA 237, n.36, Appendix A, para. A.

34

same observation is equally true with

respect to the creation of separate all-

white Air Brake and Wheel and Axle depart

ments.

3 . Development of the Seniority

System

a • Dî v o n_o A aH £ aiHiH£_

units. Both the Steelworkers and the

Machinists entered into initial collective

bargaining agreements with Pullman-Standard

on April 7, 1942. Plaintiffs' exhibits 17,

33 (1978 Trial). The seniority agreements

applied only to departments or jobs

within the bargaining unit for which those

unions were "recognized as the exclusive

collective bargaining agent." The agree

ments did not provide any "seniority"

rights for employees who transferred from

one bargaining unit to another bargaining

unit. An employee who transferred from

the Steelworkers' to the Machinists' unit

35

would start

worker who

as a "new man"? in effect, the

transferred bargaining units

39/

forfeited

sion of

seriously

nities of

a worker

unless he

all job security. The divi-

the plant into bargaining units

affected the employment opportu-

workers. As a practical matter,

would spend his entire career,

progressed to management, in the

40/jobs of one bargaining unit.

39/ The 1956 agreement between the Steelworkers and Pullman-Standard made this

forfeiture provision explicit and clearly

applicable to all transfers, even those

instituted by Management: "An employee

hereafter transferred to a position outside

of the bargaining unit . . . shall lose his

seniority in the bargaining unit at the

time of such transfer." JA 194. See also

n. 45, infra.

40/ For example, white employee Colon

Clemons testified that he entered the

IAM's Die and Tool department as a laborer

and progressed to craneman and machinist. JA 339. The seniority lists introduced

into evidence show other similar job

36

Since the Machinists and the Steel

workers continued to represent employees

in separate bargaining units until the

plant closed in January 1981, the effects

of the 1941 racial gerrymandering of

bargaining units continued for four dec

ades. Although the IAM bargaining unit

11/was modified in 1944, the IAM con

tinued to represent employees in two

departments, Maintenance and Die and Tool,

until the plant closed. These departments

remained all-white until 1970. App. 7.

40/ Continued

progressions and the general restriction of employees to one bargaining unit. See

plaintiffs' exhibits 2-8 (1974 Trial),

plaintiffs' exhibits 2-12 (1978 Trial).

41/ The IAM agreed to the transfer of the jobs in three departments, Welding, Air

Brake, and Wheel and Axle, to the bargain

ing unit of the Steelworkers. JA 174-76.

37

A final change in the 1941 bargaining

unit division at the plant occurred in

1 946 when the jobs originally represented

by the IBEW, were transferred into the

baraaining unit represented by Local 1466

42/Steelworkers. App. 41, JA 298 304.

b . Application of the Sen

iority System Within the Steelworkers' Bar

gaining Unit. Initiated in the proceedings

to unionize the plant in 1941, the senior

ity system continued to develop until 1954

when it reached the form it retained until

the plant closed. "The division of the

plant's work force into twenty-eight

separate seniority units - 26 USW Units and

42/ The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers had been certified as

the representative of two small groups of employees, electricians and powerhouse

operators. App. 36, JA 165.

38

2 IAM units - has remained essentially un-

43/

changed since 1954," (footnote omitted).

App. 31. The importance of seniority with

in the Steelworkers' unit increased sub

stantially after 1954 because (1) the scope

of seniority was broadened from "occupa-

44/

tional" to "departmental;" (2) the dis

cretion of the Company to transfer an em-

43/ Since blacks were excluded from the Machinists' bargaining unit, the exercise

of seniority rights of employees within

that bargaining unit are not directly

relevant to the issue before the Court.

However, obstacles to transfer into the

bargaining unit are directly relevant.

See section a, supra.

44/ The first collective bargaining

agreement between Pullman-Standard and the

Steelworkers, signed in April 1942, provid

ed for "departmental" seniority: "No

employee shall hold seniority in more than

one department ...." JA 181. In 1947 the

seniority criterion was changed to "occupa

tional": "Occupational seniority within a

department will prevail for all employees

...." JA 189. In 1954 the parties reverted

to the use of departmental seniority. JA

1 94.

39

ployee of the Company to transfer an

employee without any loss of seniority to

45/the employee was restricted; and (3) the

use of seniority was extended from the

determination of layoff or recall during an

"increase or decrease of forces," JA 180,

182, 184, 188, to the determination of

promotions. JA 201-02.

The expansion of seniority rights was

preceded in 1953 and 1954 by numerous

departmental readjustments, which, like the

45/ in 1944, the collective bargaining

agreement was modified to provide that if

the Company transferred an employee because

of "exceptional ability" he could continue

to accumulate seniority in two departments.

JA 185-86. The provision also applied

during the period, 1947-1954, when occupa

tional seniority was used. JA 189-90. In

1954 the provision was severely limited by,

inter alia, requiring Management to "re-

turn" the transferred employee "within a

period of one (1) year from date of transfer to his original department ...." JA

194-95. See also n.39, supra.

40

departmental changes during unionization,

increased the number of one-race depart

ments. Since 1952 the negotiation posi

tions of the parties had indicated that a

return to departmental seniority was

likely. In August 1952, the Steelworkers

proposed that they negotiate a company

wide, master contract with Pullman-Stan

dard. JA 286. At that time the Company

had four plants where employees were

represented by the Steelworkers, two had

departmental seniority, one had plant

seniority, and one (Bessemer) had occupa

tional seniority. App. 33; 189, 278-85.

The "company ha[d] established by ...

contemporaneous studies made by it at the

time of contract negotiations -— [that]

seniority by departmental age . .. was the

modal form of agreements generally. ..."

App. 33.

41

Several earlier departmental changes

had little effect upon the seniority

or employment opportunities of the workers

who were protected at the time by occupa-

46/

tional seniority only.

46/ The Electrical and Powerhouse departments were moved in 1946 from the

defunct IBEW Unit to the Steelworkers.

Three departments, Air Brake, Welding,

and Wheel and Axle were transferred in

1 944 from the Machinists to the Steel

workers. By 1947, Air Brake, Electrical,

Powerhouse, and Wheel and Axle depart

ments were reabsorbed in the departments

they had been in before unionization.

Plaintiffs' exhibits 1 and 2. (1978

Trial). The Welding department remained

separate. Id_. In the "late 1 940's" the

Company created a separate Inspection

department staffed by white workers only.

App. 32.

The record contains the departmental

seniority lists from 1947 through 1954,

plaintiffs' exhibits 2 through 9 (1978

Trial). From these lists it is possible to

ascertain the departments, the jobs in the

departments and the race of the employees

in those jobs and departments. The race

can be determined because the employee's

number indicated his race, see n.11,

supra. It is not possible to ascertain

42

In 1 953 and 1 954 , just before the

switch from occupational to departmental

seniority, seven new one-race departments

were created within the Steelworkers'

bargaining unit: Air Brake Pipe shop,

Boilerhouse, Die and Tool, Janitors,

Plant Protection, Powerhouse, and Steel

47/Miscellaneous. Four of the depart-

46/ Continued

from the record whether from 1 944 through 1 946, the three former I AM departments or

whether in 1 946 the two former IBEW

departments remained separate departments

within the Steelworkers' unit or were

reabsorbed into other departments in the

Steelworkers' unit. The district court's

assertions as to the status of the depart

ments at this time, see App. 41, 37 n. 19,

do not have record support. The chart

prepared by the company and introduced as

exhibit 27, JA 336, which purports to show

the departmental changes at the plant, is

riddled with errors. See Appendix A to

this brief.

47/ Six of these departments were created

in June 1954 -- just two months prior

to the return to departmental seniority.

Compare plaintiffs' exhibits 8 and 9.

43

merits contained only white employees: Air

4_8/Brake Pipe shop, Boilerhouse, Power-

49/house, and Plant Protection. Three

of the departments contained only black em-

50/ _ 5J_/ployees, Die and Tool, Janitors, and

48/ Jobs in the Air Brake Pipe shop were

functionally related to jobs in the inte

grated Steel Erection department, see n. 32,

supra. Nevertheless, several jobs, staffed

by white employees only, were removed from

this department in order to form the Air

Brake Pipe shop. Compare plaintiffs'

exhibits 8 and 9.

49/ The Boilerhouse and Powerhouse depart

ments were removed from the Maintenance

department. The Powerhouse jobs had

been in the Maintenance department prior

to unionization and during the period when

occupational seniority prevailed in the

Steelworkers' unit. The Boilerhouse had always been located in the Maintenance

department. See n.46, supra; JA 243-51.

50/ The Die and Tool (CIO) department was

staffed entirely by black employees after

unionization, see p. 33, n.38. However, by 1947 the position of Welder, staffed by

[Continued]

[51/ on next page]

44

52/

Steel Miscellaneous. Therefore,

dentally with the establishment of

coinci-

depart-

50/ continued

whites, had been added to this department. Plaintiffs’ exhibit 2. In 1953 there

were two whites, Moreland #2448 and Thomp

son #2447 , in the Welder job. In 1954 these positions had been moved to the

Welding department and the Die and Tool

(CIO) department was resegregated. Plain

tiffs' exhibits 8 and 9.

51/ The court of appeals correctly summar

ized the history of the Janitors depart

ment: "between 1947 and 1952, the all-white

watchman and all-black janitors were both

in the Safety department. The 1953 senior

ity list carries both jobs under a Plant

Protection department. The 1954 seniority

list shows the janitors in an all-black

Janitors department and the watchmen

in an all-white Plant Protection depart

ment." App. 12; see plaintiffs' exhibits

2-9.

52/ In 1953 the Steel Miscellaneous

department was separated from the Steel

Stores department. Plaintiffs' exhibits 7 and 8. See also Appendix A, paragraph G.

The district court finding that the

two units "had roughly comparable racial

compositions" is misleading. App. 31-32.

In 1953 the Steel Stores department

contained 5 white and 26 black workers.

- 45

mental seniority and with the increase in

the importance of seniority and the depart-

mental structure, a substantial number of

one-race departments were created in the

Steelworkers' unit.

4. Operation of the Seniority

System After 1956. The departmental

and bargaining unit structure which had

evolved by 1954 remained "essentially11/unchanged." App. 31, 3. The depart-

52/ Continued

Plaintiffs' exhibit 8. However, all the

production employees in the Steel Miscel

laneous department were black. While the

seniority list shows 2 whites out of the 54

workers in the Steel Miscellaneous depart

ment, it is critical to note that those two

white workers were "leaders" or "foremen

A." Plaintiffs' exhibits 8, 11. Inkeeping with the policy of placing only

whites in supervisory positions, see section B. 1. a, supra, the two supervisors

in the department were white.

53/ The Boilerhouse department in the Steelworkers' unit was closed in 1 964 .

46

ments and their racial composition in 1956

and 1 964 are listed in Appendix B to this

brief. Apart from a limited order entered

by the district court in 1974, see n.62,

infra, the application of seniority re

mained essentially the same as established

in the mid-1950s. In brief, there was no

provision for transfer between bargaining

units and an employee forfeited seniority

if he transferred between bargaining

units or between departments within the

Steelworkers' unit. App. 119-20, 26,

see also section 3, supra. The district

court correctly characterized the effect of

the seniority forfeiture provision as a

53/ Continued

App. 31, n. 5. Also by 1964 the Shipping Track and Paint departments had been

merged. See Tables 1 and 2, Appendix

B.

"no-transfer rule." App. 30; see also

App. 3.

In 1968 the Company entered into

negotiations with the Office of Contract

Compliance, Department of Labor. These

negotiations led "to a conditional memoran

dum of understanding designed to enhance

opportunities for blacks," (footnote

omitted). App. 122. The conditional

memorandum included "transfer rights with

seniority carryover for black employees"

from certain "low-ceiling" departments

to "formerly all-white departments." App.

- 47 -

54/

54/ While there was no express bar to

interdepartmental transfer, because of the seniority forfeiture provision,

the system in effect "locked" employees

into the department or bargaining unit to

which they had been assigned. "In any

industry loss of seniority is a critical

inhibition to transfer," United States v.

Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418,

453 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 406

U.S. 906 (1972).

48

122 n. 15. The memorandum was rejected by

the unions and never went into effect.

App. 122, 136 n. 32; JA 41-42. In 1972 the

Company once again entered into negotia

tions with the Office of Contract Compli

ance. On this occasion Pullman-Standard

signed an agreement which was "to serve as

a corrective action program." App. 6. The

agreement provided limited transfer rights

55/

to certain black employees. Once again,

the Steelworkers and Machinists failed to

sign the agreement, App. 123 nn.17-18.

Although the district court concluded that,

55/ "Black employees with employment dates

prior to April 30, 1965, are given prefer

ence for vacancies arising in the five

traditionally all-white departments ...

and those hired before April 30, 1965, who

had been assigned to four 'low-ceiling'

departments are given preference for

vacancies arising in any of the depart

ments." (Footnote omitted). App. 123.

49

despite their failure to sign, the Unions

"apparently" agreed to accept its terms,

id. , the court issued an order declaring

the agreement "binding upon the union

56/

defendants." App. 154.

5. Racial Impact. The district

court concluded "that for each of the years

1967 through 1973 there were variations in

the racial composition of the departments

beyond that expected from random, 'color-

blind' selection." App. 52. The court

attributes this disparity to actions taken

"prior to Title VII |[enacted in July 1 964,

57/

effective as of July 1965]." 21 •

56/ The district court vacated this 1974

older when in 1977 it ruled that the

seniority system was lawful and entered

judgment for the defendants. App. 148.

57/ In order to support its conclusion,

the district court stated that it had

prepared a chart regarding post-1966

50

The district court never evaluated the

severity of the "variations in the racial

compositions of the departments." In fact,

as of 1964 the overwhelming majority of

employees at the Bessemer plant were

located in racially identifiable depart

ments: departments where there was a

"serious disproportionality" in the racial

5_8/ 59/

composition of employees. In 1964

57/ Continued

departmental assignments. The court did

not reproduce the chart in its opinion,

App. 53, and refused the plaintiffs'

request, made in a motion to amend the

judgment, to produce the chart. App. 45.

The conclusion based upon this secret

chart, that post-1966 departmental assign

ments were not being made in a discrimina

tory manner, was reversed on appeal, App.

78,and this issue is not before this Court.

58/ The determination of "serious dispro-

portionality" is based upon this Court's

analysis in Hazelwood School District v.

United States, 433 U.S. 299 , 3 1 1 n. 17

[59/ on next page]

[Continued]

51

there were 3875 employees in 28 departments

in the Bessemer plant. Of these employees,

3727 or 96% were located in racially

identifiable departments; 1274 or 96% of

58/ Continued

(1977). A detailed description of the

methodology is incuded in Appendix B.

59/ The source for the distribution of

employees in 1964 is the seniority list for

that year which was introduced in the

1974 trial as plaintiffs' exhibit 2. The

district court relied on this exhibit

in constructing a chart for the year 1965.

App. 1 2 7-2 8 n. 27. As the district

court observed, there was no seniority list

introduced for the year 1965, but the

court determined that the "functional

equivalent" of the 1965 list could be

determined "by taking account of the

additions and deletions" to the 1 964 list.

App. 120 n. 10. In this brief, the respon

dents used the same source as the district

court, plaintiffs' exhibit 2 (1974 Trial),

but we have indicated that the employment

totals are for " 1 964 ," the year by which

the seniority list is designated. Regard

less of whether a designation of "1964" or

" 1 965" would be more correct, the data

reflects the employment composition at the

plant on or near the effective date

of Title VII.

52

the 1325 black employees and 2453 or 96% of

the 2550 white employees were in racially

60/

identifiable departments. Appendix

B, Table 1. The same analysis for 1 956,

the date when the seniority system had

fully evolved, shows that the racial impact

of the system was firmly established at

that time — over 85% of the employees were

in racially identifiable departments.

Appendix B, Table 2.

Despite the substantial racial alloca

tion of employees by department, the

60/ Nineteen of the twenty-eight ^depart

ments in 1964 were racially identifiable,

according to the statistical analysis in

Castaneda and Hazelwood, since there was a

"serious disproportionality" in the

racial composition of these departments.

See Appendix B. In addition to these 19

departments, there were an additional

three departments which had historically

been staffed entirely by white employees,

Boilerhouse, Powerhouse and Template.

See n.87, infra.

53

Steelworkers and the Company repeatedly

assert that the "vast majority" of employ

ees were in "racially mixed" or "integrated"

departments. Steelworkers 6-7, 14-15,

27-28, 8a-11a, 20a-22a; Company Brief 10,

14, 42. The petitioners’ use of the term

"integrated," regardless of the dispropor-

tionality of the racial composition in a

department, distorts the actual racial

staffing of departments.

The racial staffing of departments and

the "lock-in" effect of the seniority

system had a serious adverse impact on the

earnings of black employees. In 1964, 8 ofii/

the 28 departments had a median job class

61 / In the collective bargaining agree

ments between the Steelworkers and Pullman-

Standard, jobs are placed within "job

classes." The job classes range from 2

through 2 0, with 20 being the highest paid.

The base hourly wage, incentive and non-

54

of 10 or above, thirteen departments had

median job classes between 5 and 7, and

seven departments had median job classes

below 5. Appendix B, Table 3, Of the 2545

white employees, 1959 or 76.9% were in the

eight departments with a job class median

of 10 or above, whereas only 230 or 17.3%

of the black employees were in these

departments. In the "low-ceiling" depart

ments, those with a job class median below

5, the racial proportion was reversed: 433

or 2 1.9% of black employees, whereas only

177 or 5.7% of white employees were in

these departments. Id.

61/ Continued

incentive, for a job is determined by its

job class, see e.g., 1965 Collective

Bargaining Agreement, Company exhibit 263

(1974 Trial). The "job class (JC) level

... determines [a job's] relative ranking

in base pay in comparison to other jobs,"

although piece-rate scales may play a role

in the actual earnings potential of a

particular job. App. 119 n. 8 .

55

The continuing economic effect of the

seniority system is illustrated by the

disparity in the job class levels of black

and white employees who were employed in

1973 in the Steelworkers' bargaining unit

and who had more than 6 years of seniority:

551 or 74% of all black employees as

compared to 119 or 16% of all white

employees earned less than $4.25 an hour,

job class 8 or below. JA 65. Moreover,

634 or 81% of all white employees as

compared to 192 or 20% of all black

employees earned more than $4.40 an hour,

job class 10 or above. I_d. The average

hourly base rate for black employees in the

Steelworkers' unit was $4.14 as compared to

$4.45 for white employees. Id.

The historical exclusion of blacks

from the IAM bargaining unit had a substan

tial adverse economic impact on blacks.

56

The two IAM departments, Maintenance

(IAM) and Die and Tool (I AM) provide some

of the greatest earnings opportunities

at Pullman-Standard. Appendix B, Table 3.

Of the 139 employees in the IAM unit as of

June 1 , 1 972, 1 1 were black. No black in

the unit had a seniority date earlier than

1971. The average hourly base rate of all

6_2 /

employees was $4.57 an hour. In the

62/ Plaintiffs' Exhibits (1974^Trial)

includes a seniority list of the two

IAM departments as of June 1 , 1 972, from

which can be computed the number of

employees in each job. The above employee

totals include only those employees who

were in the IAM bargaining unit as of the

date of the seniority list, June 1 , 1 972.

For each of the jobs in the IAM unit,

the wage rates used were those in effect

from October 1972 until October 1973.

Those rates appear in the IAM 1971 collec

tive bargaining agreement with Pullman-

Standard. Plaintiffs' Exhibit 31 (1978

Trial). The 1 972 IAM wage rates are used

since the last complete IAM seniority list

is a 1972 list. Where the hourly rates

57

Die and Tool (IAM) department where there

were 67 whites and 5 blacks, the average

hourly base rate was $4.52; in the Mainte

nance (IAM) department where there were 61

whites and 6 blacks the average hourly base

rate was $4.62. The average hourly base

rate of employees in the IAM bargaining

unit exceeded that of blacks in the USW

63/

unit by at least $.43 per hour.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

A. "[I]n enacting Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress intended

62/ Continued

indicate a pay range for a particular job,

the median rate for that 50b was used which

rate was then multiplied by the total

number of employees in that job.

63/ This figure understates the dispar

ity in wage rates between blacks in the USW

unit and workers in the IAM unit because

1 973 wage rates are used for the USW unit

and 1972 rates for the IAM unit.

58

to prohibit all practices in whatever form

which create inequality in employment

opportunity due to discrimination on the

basis of race, religion, sex, or national

origin." Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. 747, 763 (1976). In Pullman-

Standard's Bessemer plant, as in other

plants, particularly in the South, prac

tices of racial gerrymandering and manipu

lation of seniority systems were common.

The protection in Section 703(h) for "bona

fide seniority systems" must not "be given

a scope that risks swallowing up Title

VII’s otherwise broad prohibition of

'practices, procedures, or tests' that

disproportionately affect members of those

groups that the Act protects." California

Brewers Association v. Bryant, 444 U.S 598,

608 (1980).

59

B. Section 703(h) "does not immunize

all seniority systems. It refers only to

'bona fide systems'...." Internat ional

Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 at 353 ( 1 977 ). A senior

ity system is not bona fide and thus not