Bell v. Maryland Brief of Respondent

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bell v. Maryland Brief of Respondent, 1963. 14517ba3-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b93fbc80-f4fc-4edd-8146-078612a791bf/bell-v-maryland-brief-of-respondent. Accessed February 02, 2026.

Copied!

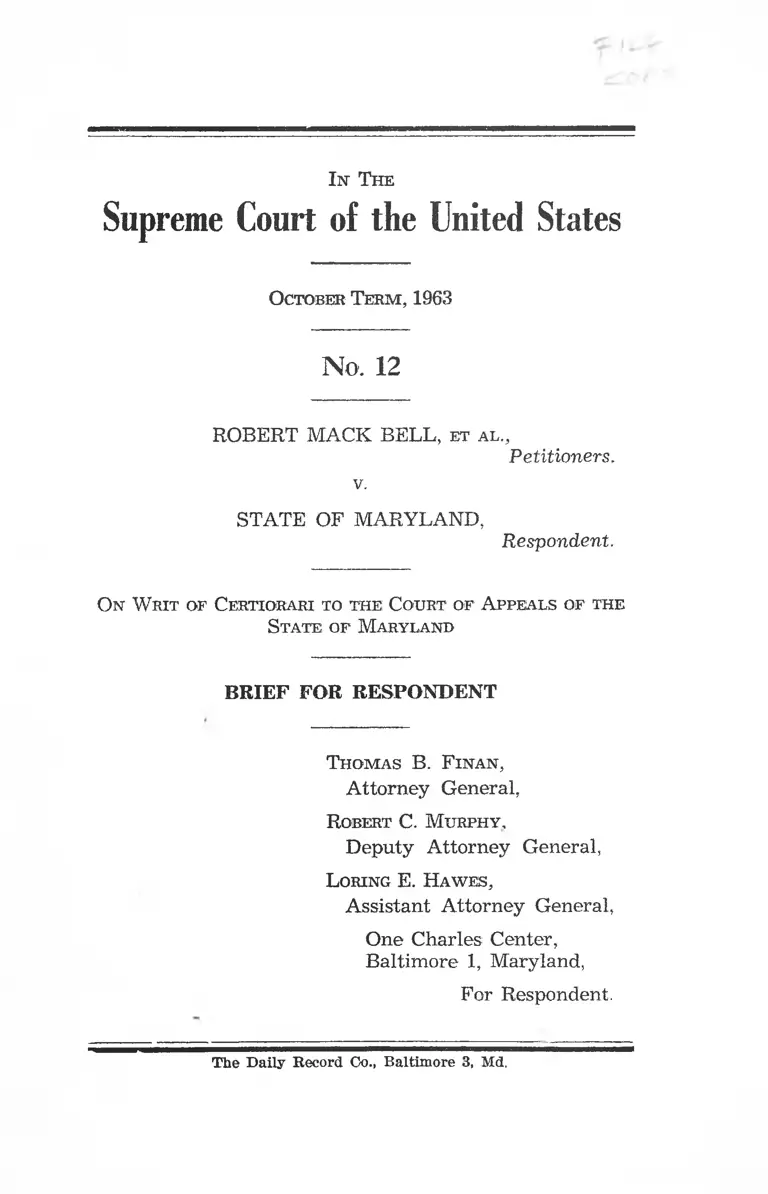

In T he

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term , 1963

N o. 12

ROBERT MACK BELL, et a l .,

v.

Petitioners.

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Respondent.

O n W rit of Certiorari to th e Court of A ppeals of the

S tate o f M aryland

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

T h o m a s B. F in a n ,

A ttorney General,

R obert C. M u r ph y ,

D eputy A ttorney General,

L oring E. H a w e s ,

A ssistant A ttorney General,

One Charles Center,

Baltim ore 1, M aryland,

For Respondent.

The Daily Record Co., Baltimore 3, Md.

I N D E X

T able of Co ntents

page

O p in io n B elow .......................................................................... 1

J urisdictio n .................................................................................... 1

Q u estio n s P resented ................................................................. 2

Co n stitu tio n a l P rovisions and S tatute Involved 2

S tatem ent of F a c t s .................................................................. 2

A rg um ent :

I. A S tate crim inal trespass conviction of Negroes

protesting a racial segregation policy in a pri

vate restau ran t does not constitute state action

proscribed by the Fourteenth A m endm ent in a

m unicipality w here neither law nor local cus

tom require segregation.......................................... 4

II. Petitioners w ere not denied due process of law

since the ir convictions under the M aryland

Crim inal Trespass S tatu te w ere based upon evi

dence of the proscribed conduct, or, in the a lter

native, because the statu te gave fair w arning of

the prohibited conduct 10

Co n clusio n 14

Table of Cita tio n s

Cases

Alford v. U nited States, 274 U.S. 264 12

A vent v. N orth Carolina, 373 U.S. 375 12

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249, 97 L. Ed. 1586, 73

S. Ct. 1031...................................................................... 7

Bell v. State, 227 Md. 302, 176 A. 2d 771 1, 2, 5,12

ii

PAGE

B urton v. W ilmington Parking A uthority, 365 U.S.

715, 6 L. Ed. 2d 45, 81 S. Ct. 856................................ 8

Civil Rights Cases. 109 U.S. 3............................................ 9

Eastm an v. State, 131 Ohio St. 1, 1 N.E. 2d 140, appeal

dismissed 299 U.S. 505................................................ 13

G ardner v. Vic Tanny Compton, 182 Cal. App. 2d 506,

87 A.L.R. 2d 113.......................................................... 9

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374................................ 4

Greenfield v. M aryland Jockey Club, 190 Md. 96, 57

A. 2d 335........................................................... 8

Griffin v. Collins, 187 F. Supp. 149, 152 (D.C. Md.

1960) ............................................................................... 7

Griffin v. State, 225 Md. 422, 171 A. 2d 717................... 12

K rauss v. State, 216 Md. 369, 140 A. 2d 653.................... 11

Lom bard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267.............................. 4

M adden v. Queens County Jockey Club, 296 N.Y.

249, 72 N.E. 2d 697; 1 A.L.R. 2d 1160, 332 U.S. 761 8

McGowan v. M aryland, 366 U.S. 420, 428................... 13

M arrone v. W ashington Jockey Club, 227 U.S. 633. 8

M artin v. S tru thers, 319 U.S. 141, 87 L. Ed. 1313....... 7

McKibbin v. Michigan Corp. & Securities Commis

sion, 369 Mich. 69, 119 N.W. 2d 557......................... 8

Omaechevarria v. Idaho, 246 U.S. 343........................... 12

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244............................. 4

Reed v. Hollywood Professional School, 169 Cal. App.

2d 887, 338 P. 2d 633.................................................... 9

Shelley v. Kraem er, 334 U.S. 1........................................ 7, 9

Slack v. A tlantic W hite Tower System, Inc., 181 F.

Supp. 124, 126, 127 (D.C. Md., 1960), aff’d 284

F. 2d 746 (4th Cir., 1960).......................................... 5, 7

Spencer v. M aryland Jockey Club, 176 Md. 82, 4 A.

2d 124, app. dismissed 307 U.S. 612....................... 8

U nited States v. Harriss, 347 U.S. 612, 617................... 13

Williams v. H oward Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d

845 ( 4th Cir., 1959).................................................... 7

Ill

Statutes

PAGE

A nnotated Code of M aryland (1957 E d itio n ):

A rticle 27—

Section 576 .......................................................... bi

section 577 (M aryland Crim inal Trespass

S tatu te) ................................................ 2 ,3 ,10,12,14

A rticle 43—

Sections 200-203 .................................................. 8

A rticle 56—

Section 8 .............................................................. 8

Section 178 ............................... 8

Constitution of the U nited States:

Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1 2, 4, 9

Laws of M aryland, 1900:

C hapter 66 ............................................................ 2

U nited States Code, Volume 28:

Section 1257(3) .................................................. 1

Miscellaneous

American Jurisprudence, Volume 4, Assault and Bat

tery, Section 76, page 167 7

American Law Reports:

Volume 1 (2d), page 1165 9

Volume 9, page 379 ?

Volume 30, page 651 9

Volume 33, page 421............................................ 7

Volume 60, page 1089 9

Restatem ent of the Law of Torts:

Section 77 ............................................................ 7

I n T he

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober Te r m , 1963

N o. 12

ROBERT MACK BELL, et a l .,

Petitioners.

v.

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Respondent.

O n W rit of C ertiorari to' the Court of A ppeals of th e

S tate of M aryland

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of th e Court of Appeals of M aryland (R. 10 )

is reported in 227 Md. 302, 176 A. 2d 771 (January 9, 1962).

The M emorandum Opinion of the Crim inal Court of Balti

more, Byrnes, J., March 23, 1961 is unreported (R. 6).

JURISDICTION

The Petitioners allege th a t the Suprem e Court of the

U nited S tates has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

1257(3).

2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does a sta te crim inal trespass conviction of Negroes

protesting a racial segregation policy in a private restau

ran t constitute sta te action proscribed by the Fourteenth

A m endm ent in a m unicipality w here neither law nor local

custom requ ire segregation?

2. W ere Petitioners denied due process of law because

the ir convictions under the M aryland Crim inal Trespass

S ta tu te w ere based upon no evidence of the proscribed

conduct, or because the sta tu te gave no fair w arning of the

prohibited conduct?

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND

STATUTE INVOLVED

1. Section 1, Fourteenth A m endm ent to the Constitu

tion of the U nited States.

2. Section 577, A rticle 27, A nnotated Code of M aryland

(1957 E dition); C hapter 66, Law s of M aryland, 1900 (see

Amended Brief for Petitioners, Pages 4 and 5).

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The facts in Bell v. M aryland differ considerably from

the facts in the sit-in cases previously before this Court.

Here, the dem onstrators entered a private restau ran t in

a privately-ow ned building in Baltim ore City (R. 30).

N either the m unicipality in w hich the restau ran t was

located nor the S tate had a restau ran t segregation law.

Nor was there any evidence of a local custom of segrega

tion in the community (R. 50). The dem onstrators, who

passed through the street-level lobby of the restaurant,

w ere m et a t the entrance to the private dining area of the

restauran t by the hostess, who norm ally seats customers

3

(R. 23). She was standing a t the top of four steps (R. 23 ).

Petitioners w ere barred from fu rth er en try into the dining

room by the hostess and the A ssistant M anager on the

sole ground tha t th e ow ner of the restau ran t feared a

loss of clientele if Negroes w ere perm itted to ea t in the

private dining areas, of th e restau ran t (R. 24, 32, 43). In

spite of this notice not to enter, the dem onstrators never

theless pushed by the hostess and took seats a t tables

throughout the dining room, one or tw o at a table, and

in the grille in the basem ent (R. 25, 47). M eanwhile a

long conversation took place betw een the leader of the

group and the m anager and owner of the restau ran t (R.

32). The Petitioners w ere requested to leave but refused

to do so (R. 28). The police w ere summoned. W hen they

arrived the m em bers of the Negro group w ere the only

persons rem aining in the restau ran t (R. 39). The Trespass

Statute, Section 577, A rticle 27, A nnotated Code of M ary

land (1957 Edition) was read to' the group in the presence

of the police (R. 28, 39). Some of the group left, bu t the

rem ainder refused (R. 39). Employees of the restau ran t

took down the names and addresses of those rem aining

(R. 39). Since the police refused to arrest the Petitioners

w ithout a w arrant, Mr. Hooper, the owner, w ent to the

Central Police Station to obtain w arran ts (R. 39). The

m agistrate spoke w ith the leader of the group on the te le

phone; and the Petitioners agreed to come down to the

police court on Monday morning and subm it to tria l (R.

40). One and one-half hours after the ir initial entry, P eti

tioners left the restauran t (R. 41). The leader of the

demonstrators: la te r testified tha t the group rem ained on

the premises even though they knew they w ere going to

be arrested; and th a t being arrested was a part of their

technique in dem onstrating against segregated facilities

(R. 49).

4

ARGUMENT

I .

A STATE CRIMINAL TRESPASS CONVICTION OF NEGROES

PROTESTING A RACIAL SEGREGATION POLICY IN A PRIVATE

RESTAURANT DOES NOT CONSTITUTE STATE ACTION PRO

SCRIBED BY THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT IN A MUNICIPAL

ITY WHERE NEITHER LAW NOR LOCAL CUSTOM REQUIRE

SEGREGATION.

Conspicuously absent from the facts in th is case is S tate

action. In order to be constitutionally prohibitive, S tate

action m ust “coerce,” “command”, and “m andate” the

racial discrim inatory practice leading to conviction of the

petitioners. Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267. There

is neither such command, coercion, nor m andate here. The

S ta te’s involvem ent is not to a degree tha t it m ay be held

responsible for the discrimination.

M aryland a t the tim e of the arrest of the Petitioners did

not have a sta tu te requiring segregation of restaurants and

other places of public accommodation. Cf. Peterson v.

Greenville, 373 U.S. 244. Nor did the City of Baltimore,

the situs of th e subject restauran t, have an ordinance pro

hibiting equal access to restaurants. Ibid. The evidence

adduced a t the tria l did not reveal th a t the proprietor

refused service on the basis of any express official S tate

or municipal policy. Cf. Lombard v. Louisiana, supra. I t

was not unlaw ful for the restau ran t ow ner to serve the

dem onstrators; nor was it unlaw ful for them to eat in the

restauran t if the ow ner had served them. Cf. Peterson v .;

Greenville, supra; Gober v. Birm ingham , 373 U.S. 374.

The neutra lity of the S tate here is im plicit in the acts

of its officers. The police, when summoned by the pro

prietor refused to a rrest the Petitioners (R. 40). The

police insisted tha t the ow ner sw ear out w arran ts before

a Police M agistrate. The arrests w ere never made by

5

the police even though one and one half hours after their

initial entry, the Petitioners w ere still in the restauran t

refusing to leave. The proprietor, nevertheless, had ad

vised the Petitioners th a t they would be arrested if they

failed to leave and he read the trespass sta tu te to them.

(R. 29, 48). The Petitioners w ere not placed in custody.

In fact, they made arrangem ents w ith the M agistrate by

telephone to come to the court the following Monday,

voluntarily, to subm it to tria l (R. 40, 50).

Comm unity custom did not dictate the resu lt in the

Bell case. No evidence was produced before the tria l

court to show the existence of an overriding custom or

“clim ate” of segregation in the community causing un

equal enforcem ent of otherwise innocuous State laws

solely to exclude Negroes on the basis of their race. In

fact the evidence reveals exactly the opposite conclusion.

Quarles, leader of the dem onstrators, testified tha t in a

num ber of other restaurants w here the dem onstrators had

sought service, they sat, w ere served and ate (R. 50). In

such a fluid situation in the im mediate community, it could

hardly be concluded now by the m ere recitation of em pty

statu tes not even before the tria l court (Bell brief, p. 31,

n. 13), th a t Jim Crow ruled the roost. Furtherm ore, over

th ree years ago, a considerable period considering the

rapid evolution of race relations, Chief Judge Thomsen

of the U nited States D istrict Court of M aryland found,

as a m atter of fact, th a t in February of 1980 there was no

“custom, practice, and usage of segregating the races in

restaurants in M aryland.” Slack v. A tlantic W hite Tower

System , Inc., 181 F. Supp. 124, 126, 127, aff’d Fourth Cir.,

284 F. 2d 746. In th a t decision, after reviewing facts pre

sented by both sides on the question of custom and usage,

Chief Judge Thomsen stated:

“Such segregation of the races as persists in restau

ran ts in Baltim ore is not required by any statu te or

6

decisional law of M aryland, nor by any general custom

or practice of segregation in Baltim ore City, bu t is

the resu lt of the business choice of the individual

proprietors, catering to the desires or prejudices of

th e ir custom ers.” Ibid, pages 127, 128.

The reason given by th e ow ner of th e restau ran t for re

fusing service to Petitioners was th a t in his opinion his

particu lar clientele did not w ish to eat w ith Negroes.*

“I tried to reason w ith these leaders, told them th a t

as long as m y custom ers w ere deciding who they

w ant to eat w ith, I ’m a t the m ercy of m y customers.

I ’m try ing to do w hat they want. If they fail to

come in, these people are not paying m y expenses,

and m y bills. They didn’t w ant to go back and ta lk to

m y colored employees because every one of them are

in sym pathy w ith me and th a t is w e’re in sym pathy

w ith w hat the ir objectives are, w ith w hat they are

try ing to abolish, bu t w e disapprove of their methods

of force and pushed th e ir w ay in” (R. 32, 33).

This statem ent was corroborated by Petitioner Q uarles’

own statem ent:

“I was asking him, well, w hy w asn’t it these Negroes

he thought so m uch of w eren’t capable of sitting a t

his tables to eat? He said, well, i t’s because my cus

tom ers don’t w ant to eat w ith Negroes” (R. 43).

Petitioners’ argum ent tha t the S tate of M aryland has

denied to Petitioners equal protection of its laws is based

upon the erroneous theory th a t the S tate of M aryland

has caused the Petitioners’ convictions of a crime from

which persons other than Negroes would be immune. In

the absence of legislation to the contrary, the State is not

* Although the nominal owner of the restaurant is a corporation,

of which Mr. Hooper is President, he is referred to herein as the

owner of the restaurant in the same manner as he is referred to as

the owner in the testimony (R. 30, 31).

7

charged w ith the positive duty of prohibiting unreason

able discrim ination in the use and enjoym ent of facilities

licensed for public accommodation. W illiams v. Howard

Johnson’s Restaurant, (4th Cir.) 268 F. 2d 845; Slack v.

Atlantic W hite Tower System , Inc., 181 F. Supp. 124, a il’d,

(4th C ir.) 284 F. 2d 746. The ow ner of a restaurant, having

the legal righ t to select the clientele he w ill serve, may, to

enforce this right, use reasonable force to repel or eject

from his place of business any person whom he does not

w ish to serve for w hatever reason. See cases collected in

9 A.L.R. 379 and 33 A.L.R. 421; also 4 Am. Jur., Assault

and Battery, Section 76, page 167; Restatem ent of the Law

of Torts, Section 77; M artin v. Struthers, 319 U.S. 141.

So long as such righ t of the proprietor exists, to leave,

as his sole remedy, the application by him of force would

surely offend the principles of an ordered society. Cf.

Griffin v. Collins, 187 F. Supp. 152. However, in calling

upon a peace officer of the S tate to eject any person, the

owner m ay employ only such means involving the S tate

as do not single out and enforce sanctions against a par

ticular racial class of persons. This is the gist of the S tate

action argum ent.

Petitioners’ theory is incorrect because w here the appli

cation of the crim inal trespass sta tu te operates equally

against all persons whom the proprietor wishes to exclude

or eject, and the S tate is not significantly involved in the

ow ner’s selection, then the neutra l use of the State law

enforcem ent process to enforce the proprietor’s selection

of clientele is not prohibited by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Cf. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1; Barrows v. Jack-

son, 346 U.S. 249.

Petitioners fu rther contend tha t licensing of restaurants

by the S tate is a significant factor. However, S tate action

w ith respect to licensed facilities depends upon w hether

8

interdependence betw een S tate and its licensees is to an

ex ten t tha t the S tate participates in and can regulate deci

sions of its licensees relating to private discrim ination on

the basis of race or color. Burton v. W ilm ington Parking

A uthority, 365 U.S. 715; M cK ibU n v. Michigan Corpora

tion & Securities Commission, 369 Mich. 69, 119 N.W. 2d

557 (1963). W here the statu to ry fee, imposed by the State

upon a business enterprise operated for a profit, is a m ere

tax on the business and not a regulatory license, there can

be no S ta te involvement in the decisions of the internal

m anagem ent of the business, Spencer v. M aryland Jockey

Club, 176 Md. 82, 4 A. 2d 124, app. dismissed, 307 U.S. 612.

W here the licensing is regulatory in th e exercise of the

police power, however, the Legislature m ay prescribe rea

sonable rules w ith in the scope of the regulation. Any

restau ran t operated for profit in M aryland m ust obtain a

license w hether it operates as an exclusive club or is open

to the public generally. M aryland Code (1957 Edition),

A rticle 56, Section 178. This license is a sta tu tory fee or

tax. The distinction betw een those food service facilities

th a t m ust pay the statu tory fee and those tha t are exem pt

therefrom , is w hether or not the business operates for

profit. Ibid, Sec. 8. There is no statu to ry exem ption for

facilities tha t operate as exclusive clubs or place restric

tions upon clientele. The police and health statutes apply

to all establishm ents regardless of profit or selection of

clientele. M aryland Code, A rticle 43, Secs. 200-203.

I t is settled law in M aryland and in other jurisdictions

th a t the licensing of a place of public am usem ent does not

constitute a franchise requiring the owner to furnish en

terta inm ent to the public or adm it everyone who applies.

Greenfield v. M aryland Jockey Club, 190 Md. 96, 57 A. 2d

335; Marrone v. W ashington Jockey Club, 227 U.S. 633;

Madden v. Queens County Jockey Club, 296 N.Y. 249, 72

N.E. 2d 697; 1 A.L.R. 2d 1160, cert. den. 332 U.S. 761; cases

9

collected in 1 A.L.R. 2d 1165, 60 A.L.R. 1089, 30 A.L.R. 651.

Nor does the refusal to contract, based solely upon the

race of the p arty seeking the bargain, offend the guaran

tees of the Fourteenth Amendment. Reed v. Hollywood

Professional School, 169 Cal. App. 2d 887, 338 P. 2d 633;

Gardner v. Vic Tanny Compton, 182 Cal. App. 2d 506, 87

A.L.R. 2d 113.

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, has no application here. In

tha t case the constitutional righ t violated by the S tate’s

enforcem ent of restrictive covenants was a property right—■

the righ t to the use and enjoym ent of property already

purchased. In the case before this Court, Petitioners w ere

denied no rights or property. U nder the present status of

the law they had none. Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3. This

C ourt’s holding th a t each person in the community has

a righ t to rem ain on private premises of another operated

as a business, licensed or otherwise, w ithout the permis

sion of the owner, would be tantam ount to conferring

upon ever person an inchoate property righ t in the busi

ness premises, becoming vested at the mom ent of entry.

In the absence of legislation creating or taking away prop

erty rights involved here, such a holding would not be

proper exercise of the judicial function.

In conclusion, in order to m ake Shelley v. Kraemer

logically consistent w ith the resu lt in the case a t bar urged

by these Petitioners, this Court m ust hold th a t these

Negroes had an inalienable righ t to enter and receive food

service in Hooper’s Restaurant, which righ t could not be

denied them by Mr. Hooper on the basis of their race

alone. A nything short of such a holding would be begging

the question; for if this Court holds tha t Petitioners’

rights w ere m erely dependent on the existence of notices

posted upon the door, the basic civil rights issue will

m erely be shifted to the street.

10

II.

PETITIONERS WERE NOT DENIED DUE PROCESS OF LAW SINCE

THEIR CONVICTIONS UNDER THE MARYLAND CRIMINAL TRES

PASS STATUTE WERE BASED UPON EVIDENCE OF THE PRO

SCRIBED CONDUCT, OR, IN THE ALTERNATIVE, BECAUSE THE

STATUTE GAVE FAIR WARNING OF THE PROHIBITED CONDUCT.

There are am ple facts in the record showing violation

of the M aryland trespass statute. Petitioners entered the

lobby of Hooper’s R estaurant through a revolving door.

Petitioners w ere notified by the hostess; (R. 24, 42) and

A ssistant M anager (R. 43, 47) of the restau ran t th a t they

would not be perm itted to en ter and be seated in th e

private dining areas of the restaurant. Nevertheless, p a rt

of the group of dem onstrators ascended the four steps

separating the lobby from the dining room and pushed by

the hostess to gain en try to the dining room. P a rt of the

group, also ignoring the m anagem ent’s w arning, descended

the steps from th e lobby to the grille on the low er floor

(R. 43, 47).

Clearly, under the facts of this case, Petitioners, a fte r

notification by the ow ner’s agent not to do so, entered and

crossed over the prem ises and private property of another

in violation of the M aryland Crim inal Trespass S tatute.

That Petitioners w ere so notified was adm itted by Quarles,

leader of the group, in his testim ony (R. 42, 43). As to the

dem onstrators who w ent to the grille downstairs, Quarles

stated:

“Q. W hy did some of the students go downstairs?

D idn’t you say they w ent downstairs because they

couldn’t be seated upstairs? A. A fter they w ere

blocked forcibly by the m anager and hostess, they pro

ceeded downstairs to seek service” (R. 46, 47).

Judge Byrnes, who presided a t the trial, in his Memo

randum Opinion (R. 6, 7) found as a m atter of fact th a t

11

th e testim ony disclosed th a t the defendants entered the

restau ran t and requested the hostess to assign, them seats;

bu t she refused, inform ing Petitioners tha t it was not the

policy of the restau ran t to serve Negroes. She said she

was following the instructions of the owner of the restau

rant. Commenting on th e evidence, Judge Byrnes stated:

“Despite this refusal, defendants persisted in the ir

dem ands and, brushing by the hostess, took seats a t

various tables on the m ain floor and at the counter in

the basem ent” (R. 7).

I t is subm itted th a t the evidence before the tria l judge

in th is case goes fa r beyond the m ere refusal to leave after

law ful entry, the basis of the attack on the application of

th e M aryland statute. On the basis of the foregoing refer

ences to the testimony, and Judge Byrnes’ comments

thereon, it is clear th a t there was evidence of notice to

the Petitioners by the owner; and th a t such evidence was

considered by the tria l judge. Cf. Krauss v. State, 216 Md.

369, 140 A. 2d 653 (1958).

I t should be noted th a t the M aryland sta tu te refers both

to “entry upon” and “crossing over” such premises. The

Petitioners in this instance w ere notified by the ow ner’s

agent not to enter the dining areas of the premises. If the

Court should construe the statu te to require notification

of entry, as to those portions of the premises, such notifi

cation was given. B ut here, under the M aryland statute,

it is unnecessary to go th a t far. The M aryland statu te

m erely requires tha t the owner notify the potential tres

passer not to “cross over” his property. Implicit in such a

w arning is the command to halt and advance no fu rther

on the ow ner’s premises, when so notified.

The construction of the statu te advanced here is con

sistent w ith the fact th a t M aryland has tw o crim inal tres

pass statutes. The second count of the indictm ent was

draw n pursuant to Section 576 of A rticle 27 of the Mary-

12

land Code (1957 E d .). This Section of the crim inal trespass

act prohibits the en try of “posted” premises. Clearly, such

statu te pertains to notification by means of posting signs

a t the boundary of such property. However, by the addi

tion of the words “crossing over”, Section 577 surely refers

to the failure of the trespasser to continue beyond the

point where, upon discovery, the ow ner had notified him

to halt. The words of the sta tu te are clear and a reasonable

construction is called for. I t should be noted th a t the

sta tu te proscribes either en try upon or crossing over.

However, even if the Suprem e Court, in reviewing the

record before it, finds no evidence tha t the Petitioners w ere

duly notified not to enter or cross over the dining areas

of the restaurant, it has before it am ple evidence tha t P eti

tioners refused to leave the premises w hen so requested.

The M aryland Court of Appeals, in construing the M ary

land Trespass Statute, has stated th a t sta tu to ry references

to “en try upon or crossing over”, cover th e case of rem ain

ing upon land after notice to leave. Bell v. State, 227 Md.

302, 176 A, 2d 771 (R. 11); Griffin v. State, 225 Md. 422,

171 A. 2d 717 (1961). See also, State v. A ven t, 253 N.C.

580, 118 S.E. 2d 47, vacated and rem anded on other grounds,

A ve n t v. North Carolina, 373 U.S. 375.

The M aryland Trespass S tatu te is neither void for vague

ness nor unconstitutionally applied because the term s used

are clear and have well-settled meanings. In Alford v.

United States, 274 U.S. 264, this Court upheld the convic

tion of a person under a sta tu te penalizing the building of

a fire “near” any forest in the public domain. The Court

said th a t the word “near” taken in connection w ith the

danger to be prevented, laid down a plain enough rule of

conduct for anyone who seeks to obey the law. Sim ilarly

in Omaechevarria v. Idaho, 246 U.S. 343, this Court held

th a t men fam iliar w ith range conditions and desirous of

13

observing the law would have little difficulty in knowing

w hat was prohibited by a statu te forbidding the herding

of sheep on any cattle “range,” “usually” occupied by any

cattle grower. I t has been held fu rther tha t a crim inal

sta tu te penalizing a bank employee for receiving money,

checks, or other property as a deposit in the bank when

he has knowledge th a t it is insolvent, is not unconstitu

tionally vague although “insolvent,” which has several

meanings, was not denned in the statute. Eastman v. State,

131 Ohio S tate 1, 1 N.E. 2d 140, appeal dismissed 299

U.S. 505.

This Court has said in effect th a t persons of ordinary

intelligence engaged in an activity coming w ithin the pu r

view of a crim inal sta tu te are in a position to know w hat

th a t sta tu te proscribes. McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S.

420, 428; United States v. Harriss, 347 U.S. 612, 617. The

Petitioners here fall w ithin this rule. Petitioners were en

gaged in an activity — namely, dem onstrating against

segregation in private establishm ents — which was, to say

the least, risky. One of the risks of which they w ere aw are

was a rrest (R. 49). I t was testified tha t one or two of the

group had been arrested previously for dem onstrating in

Hooper’s R estaurant (R. 35, 56, 57); and the Trespass

S ta tu te was read to them at th a t tim e (R. 58). On tha t

occasion the owner had to use physical force to keep

dem onstrators from entering the outside door (R. 59).

Additionally in the present case the Petitioners arrived at

the restau ran t carrying picket signs which some of the

group proceeded to display outside the door after P eti

tioners w ere refused service (R. 44). Under these cir

cumstances, it could hardly be said Petitioners w ere mis

lead by the application of the M aryland Trespass S tatu te

here. In fact, it is quite apparent tha t they knew, prior

to entering, tha t they w ere not welcome in Hooper’s Res-

14

tau ran t; and the ir arrest, trial, and attendant publicity

thereof, w ere an intrinsic p a rt of the ir m ethod of express

ing protest (R. 49). Furtherm ore, if Petitioners had really

been ingenuously ignorant of the proscriptions of the M ary

land statute, they would certainly have raised the issue

a t their tria l in their defense. The record does not show

th a t Petitioners did not know they would subject them

selves to crim inal penalties for rem aining on the private

premises of another after having been w arned to leave.

In conclusion, Petitioners w ere not denied due process of

law because the ir convictions under the M aryland Crimi

nal Trespass S ta tu te w ere based upon some evidence tha t

(1) they entered the dining areas of the restau ran t after

w arning not to do so; (2) they crossed over a portion of the

premises after w arning not to do so; or (3) they had actual

notice prior to en try th a t they would be in violation of the

M aryland Crim inal Trespass S ta tu te if they sought food

service in Hooper’s Restaurant. Further, the M aryland

Crim inal Trespass S ta tu te gave fair w arning, and they

had actual knowledge, th a t to rem ain on the private prem

ises of another after w arning was proscribed by the statute.

CONCLUSION

I t is respectfully subm itted, for the reasons set forth

herein, th a t the judgm ents below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

T h o m a s B. F in a n ,

A ttorney General,

R obert C. M u r ph y ,

D eputy A ttorney General,

L oring E. H a w e s ,

A ssistant A ttorney General,

For Respondent.