Young Lords Party v. New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division Motion to Dismiss or Affirm

Public Court Documents

June 21, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Young Lords Party v. New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, 1973. d696b3c1-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b998a4c5-9e6f-4a5d-8a9a-2e3f5b93ed0d/young-lords-party-v-new-york-state-supreme-court-appellate-division-motion-to-dismiss-or-affirm. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

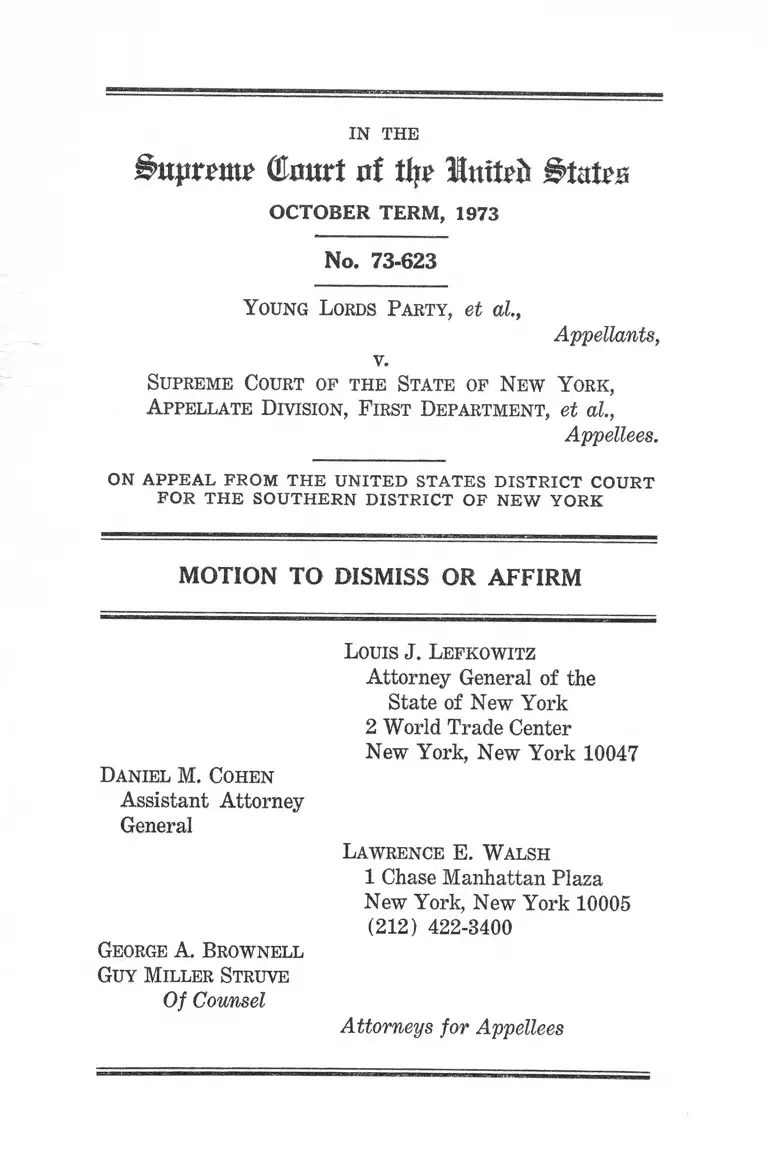

IN THE

fettjflrjwti* (tart of % Imtpfc B tatu r

OCTOBER TERM, 1973

No. 73-623

Y oung Lords Party, et at.,

Appellants,

v.

Supreme Court of the State of New Y ork,

A ppellate Division, First Department, et al.,

Appellees.

o n a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

f o r THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

Daniel M. Cohen

Assistant Attorney

General

George A. Brownell

Guy Miller Struve

Of Counsel

Louis J. Lefkowitz

Attorney General of the

State of New York

2 World Trade Center

New York, New York 10047

Lawrence E. W alsh

1 Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

(212) 422-3400

Attorneys for Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Questions Presented .................................................. 3

Statement of the C ase................................................ 3

1. Section 495(5) of the New York Judiciary

L a w ................................................................ 3

2. Part 608 of the Rules of the Appellate Di

vision .............................................................. 6

Informational Provisions of Part 608 . . . . 6

Substantive Guidelines of Part 608 ............ 8

Standards Applied by the Appellate Division

Under Section 495 (5) .............................. 9

3. The Present A ction ...................................... 11

Argument .......................................................................... 12

I. The First Amendment and the Equal Protec

tion Clause Do Not Bar State Supervision of

the Practice of Law by Charitable Corpora

tions ................................................................ 13

II. The District Court Correctly Held that Appel

lants Should First Apply for Approval to the

Appellate Division.......................................... 23

Conclusion ........................................................................ 28

11

Table of Authorities

Cases

PAGE

Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U.S. 136

(1967) ..................................................................... 25

Association for the Preservation of Freedom of

Choice, Inc. v. Shapiro, 9 N.Y.2d 376, 174 N.E.2d

487, 214 N.Y.S.2d 388 (1961) .............................. 10

Best Bldg. Co. v. Employers’ Liab. Assurance Corp.,

247 N.Y. 451, 160 N.E. 911 (1928) .................... 21

Board of Regents v. New Left Educ. Project, 404

U.S. 541 (1972) .................................................... 2

Boshes v. General Motors Corp., No. 70-244, cert.

denied, 404 U.S. 872 (1971) .................................. 22

Brotherhood of R.R. Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel.

Virginia State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1 9 64 ).............. 13, 14, 15

Carter v. Stanton, 405 U.S. 669 (1972) .................. 25

Commonwealth v. Hayden, 489 S.W.2d 513 (Ky.

1972) ....................................................................... 17

Coxy . Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559 (1 9 6 5 ).................... 15

Dombrowski V. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) .......... 26

Erdmann V. Stevens, 458 F.2d 1205 (2d Cir.), cert,

denied, 409 U.S. 889 (1972) ................................ 2, 23, 26

Gay Activists Alliance v. Lomenzo, 31 N.Y.2d 965,

293 N.E.2d 255, 341 N.Y.S.2d 108 (1973) .......... 10

Gibson Y. Berryhill, 411 U.S. 564 (1 9 73 ).................. 25

Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U.S. 167 (1 9 5 9 ).............. 24

HiettY. United States, 415 F.2d 664 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 397 U.S. 936 (1970) .......................... 17

In re Fleck, 419 F.2d 1040 (6th Cir. 1969), cert,

denied, 397 U.S. 1074 (1970) .............................. 17

In re Jones, 431 S.W.2d 809 (Mo.), cert, denied, 385

U.S. 866 (1966) .................................................... 17

Kiernan v. Lindsay, 334 F. Supp. 588 (S.D.N.Y.

1971) , aff’d, 405 U.S. 1000 (1972) ........................ 24

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 366 U.S. 36

(1961) .................................................................... 15

Lake Carriers’ Assn. v. MacMullan, 406 U.S. 498

(1972) .................................................................... 24

Law Students Civil Rights Research Council, Inc. v.

Wadmond, 299 F. Supp. 117 (S.D.N.Y. 1969),

aff’d, 401 U.S. 154 (1971) .................................... 2, 17-18

Law Students Civil Rights Research Council, Inc. v.

Wadmond, 401 U.S. 154 (1971) ............................. 19,23

Littleton v. Berbling, 468 F.2d 389 (7th Cir. 1972),

cert, granted sub nom. O’Shea V. Littleton, 411

U.S. 915 (1973) ...................................................... 2

Matter of The Associated Lawyers’ Co., 134 A.D.

350, 119 N.Y.S. 77 (1st Dep’t 1909) .................. 4, 9

Matter of Bannerman, 39 A,D.2d 894 (1st Dep’t

1972) ...................................................................... 10

Matter of CALS, 26 A.D.2d 354, 274 N.Y.S.2d 779

(1st Dep’t 1966) .................................................... 5-6

Matter of Co-operative Law Co., 198 N.Y. 479, 92

N.E. 15 (1910) ...................................................... 3,4

Matter of Prisoners Assistance Committee, Inc., 26

A.D.2d 624, 272 N.Y.S.2d 700 (1st Dep’t 1966) . . 4

Matter of Thom, 33 N.Y.2d 609, 301 N.E.2d 542,

347 N.Y.S.2d 571 (1973) ...................................... 10

Matter of Thom, N.Y.L.J., Oct. 19, 1973, p. 1, col. 5

(1st Dep’t Oct. 18, 1973) ...................................... 10

Moody v. Flowers, 387 U.S. 97 (1967) .................... 2

NAACP V. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) . . . .13, 14, 16, 20

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254

(1964) .................................................................... 15

Ill

PAGE

IV

PAGE

People V. Lawyers Title Corp., 282 N.Y. 513, 27

N.E.2d 30 (1940) ........ 21

People v. Title Guarantee & Trust Co., 227 N.Y. 366,

125 N.E. 666 (1919) .............................................. 4,21

Prentis v. Atlantic Coast Line Co., 211 U.S. 210

(1908) ..................................................................... 25

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147

(1969) ....................................................................

Speight v. Slaton, No. 72-1557, prob. juris, noted,

42 U.S.L.W. 3174 (U.S. Oct. 9, 1973) ................

State ex rel. Farber v. Williams, 183 So. 2d 537

(Fla.), cert, denied, 385 U.S. 845 (1966) ..........

State ex rel. State Bar of Wisconsin v. Bonded Collec

tions, Inc., 36 Wis. 2d 643,154 N.W.2d 250 (1967)

UMW V. Illinois State Bar Ass’n, 389 U.S. 217

(1967) ................................................................ 13,14,15

United Transportation Union v. State Bar of Michi

gan, 401 U.S. 576 (1971) ...................... 13, 14, 15-16, 23

West Virginia State Bar v. Bostic, 351 F. Supp. 1118

(S.D.W. Va. 1972).......................................... 23

Younger \. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971) .................... 26

Zuckerman V. Appellate Div’n, Second Dep’t, 421

F.2d 625 (2d Cir. 1970) ........................................ 2

Statutes and Rules

Hatch Act, 5 U.S.C. § 7324 ...................................... 8

28 U.S.C. § 1253 .......................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. § 2281 .......................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .......................................................... 2, 25

Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2701-2924 .......................................................... 5

19

26

17

17

V

Supreme Court Rule 16(1) ...................................... 1

Article 15 of the New York Business Corporation

Law, N.Y. Bus. Corp. Law §§ 1501-16 ................ 20, 21

N.Y. Bus. Corp. Law § 1503 (a) ................................ 21

N.Y. Judiciary Law § 495 .......................................... 20-21

N.Y. Judiciary Law § 495(1) .................................. 4

N.Y. Judiciary Law § 495(5) ................................ 3-6, 9-11

N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corporation Law § 404 (a) . . . . 4

L. 1848, c. 3 1 9 ............................................................ 4

L. 1909, c. 483 .............................................................. 4

Part 608 of the Rules of the Appellate Division, First

Department.............................................................. 6-11

Rule 608.2 .................................................................... 6-7

Rule 608.3 .................................................................... 7

Rule 608.5 .................................................................... 7

Rule 608.6 ........................................................................ 8, 9

Rule 608.7 .................................................................... 8-9

Rule 608.7(a) ............................................................ 8

Rule 608.7(b) ............................................................ 8

Rule 608.7 (c) .............................................................. 8

Rule 608.7(d) ........................................................... 8

Rule 608.7(e) 8-9,22

Rule 6 0 8 .7 (f) ............................................................9,22-23

Rule 608.8 ....................................................................7-8,22

Rule 608.9 ................................................................... 10-11

PAGE

VI

PAGE

Code of Professional Responsibility, DR 2-101 (A) 9

Code of Professional Responsibility, DR 2-103 (D) 9

Other Authorities

ABA, Opinions of the Committee on Professional

Ethics (1967) ........................................................ 21

Annot., Right of Corporation to Hold Itself Out as

Ready to Perform Functions in the Nature of

Legal Services, 157 A.L.R. 282 (1945) ................ 3

IN THE

&nptmz CfXxturt nf tit? In itzh States

October Term, 1973

No. 73-623

----------- — ♦----------------

Y oung Lords Party, et al,

v.

Appellants,

Supreme Court of the State of New Y ork,

A ppellate Division, First Department, et al,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

-------------------- 4.--------------------

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

Appellees, the Supreme Court of the State of New York,

Appellate Division, First Department and the individual

Justices of the Appellate Division, First Department, move

pursuant to Rule 16(1) (c) of the Supreme Court of the

United States to affirm the judgment of the three-judge

District Court (Circuit Judge Feinberg and District Judges

Tyler and Wyatt), which held that appellants’ request for

equitable relief against the Appellate Division’s rules was

premature because appellants have not yet applied to the

Appellate Division for approval pursuant to Section 495 (5)

of the New York Judiciary Law.*

* Appellees also move pursuant to Rule 16(1) (a) of the Supreme

Court to dismiss the appeal on two grounds: (1 ) The present action

2

Appellees submit that this action was clearly correct. By

applying to the Appellate Division for approval of their

practice of law— the orderly procedure prescribed by Sec

tion 495(5) of the New York Judiciary Law, which appel

lants do not attack—appellants may well satisfy most, if not

all, of their constitutional objections to the rules adopted

by the Appellate Division under Section 495(5), and any

remaining issues will be sharply focused for the District

Court. Appellants’ objection to this orderly procedure is

founded on the premise that the First Amendment and the

Equal Protection Clause absolutely prohibit any state super

vision of the practice of law by charitable corporations,

including such historically recognized potential problem

areas as solicitation, fee-splitting, referrals, and lay control.

The decisions of this Court make it clear that this extreme

position cannot be sustained.

was not one requiring a three-judge District Court under 28 U.S.C.

§ 2281, and a direct appeal does not lie to this Court under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1253_, because the rules which appellants seek to enjoin are not of

statewide_ application, having been adopted by the Appellate Division

for the First Department, which embraces Manhattan and the Bronx.

Cf., e.g., Board of Regents v. New Left Educ. Project, 404 U.S.

541, 542-45 (1972) ; Moody v. Flowers, 387 U.S. 97, 101-02 (1967).

But cf. Law Students Civil Rights Research Council, Inc. v Wad-

mond, 299 F. Supp. 117, 127-28 (S.D.N .Y. 1969), aff’d on other

grounds, 401 U.S. 154, 158 n.9 (1971). (2 ) The present action was

not within the jurisdiction of the District Court because state courts

and their justices are not “ persons” against whom an injunction suit

may be brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, and a direct appeal there

fore does not lie to this Court under 28 U.S.C. § 1253. Compare, e.g.,

Zuckerman v. Appellate Div’n, Second Dep’ t, 421 F.2d 625 (2d Cir'

1970), with, e.g., Erdmann v. Stevens, 458 F.2d 1205, 1208 (2d Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 889 (1972). See also Law Students Civil Rights

Research Council, Inc. v. Wadmond, 299 F. Supp. 117, 123-24 (S.D.

N.Y. 1969), aff’d on other grounds, 401 U.S. 154, 158 n.9 (1971) ;

Littleton v. Berbling, 468 F.2d 389, 406-08 (7th Cir. 1972), cert,

granted sub nom. O’Shea v. Littleton, 411 U.S. 915 (1973).

3

Questions Presented

1. Where a state court, charged by statute with approv

ing and supervising the practice of law by charitable cor

porations, has promulgated rules that establish an orderly

procedure for application and approval, may such corpora

tions ignore this procedure and seek an injunction against

any application of the rules on federal constitutional

grounds?

2. Do the First Amendment and the Equal Protection

Clause bar a State from supervising in any manner the

practice of law by charitable corporations, including such

potential problem areas as solicitation, fee-splitting, re

ferrals, and lay control of the practice of law?

Statement of the Case

The purpose of this statement is to summarize briefly the

facts in the record concerning the history, purpose, and

application of Section 495(5) of the New York Judiciary

Law and Part 608 of the Rules of the Appellate Division,

First Department, substantially all of which have been

omitted from the Statement of the Case in appellants’ Juris

dictional Statement.

1. Section 495(5) of the New York Judiciary Law

The common law of New York, like that of other States,

has historically barred the practice of law by corporations.*

This general prohibition was legislatively reaffirmed in

* Matter of Co-operative Law Co., 198 N.Y. 479, 483-85, 92 N.E.

15, 16-17 (1910) ; see, e.g., Annot., Right of Corporation to Hold It

self Out as Ready to Perform Functions in the Nature of Legal Serv

ices, 157 A.L.R. 282, 283-84 (1945).

4

Section 495(1) of the New York Judiciary Law, originally

enacted in 1909 as Section 280 of the New York Penal Law,

L. 1909, c. 483, which bars a corporation from practicing

as an attorney and from furnishing attorneys to others.*

The chief historical basis for this general prohibition of the

corporate practice of law in New York is the concern that

an attorney employed by a corporation may permit organi

zational goals to outweigh the interests of individual clients.

Matter of Co-operative Law Co., 198 N.Y. 479, 483-84, 92

N.E. 15, 16 (1910). A further basis is the increased dan

ger of improper solicitation, fee-splitting, and referral,

which are prohibited to individual attorneys as well as to

corporations but which are particularly difficult to regulate

effectively in the case of corporations which are permitted

to practice law. See, e.g., People v. Title Guarantee & Trust

Co., 227 N.Y. 366, 372, 378, 125 N.E. 666, 668, 670 (1919).

The common law of New York historically permitted

charitable corporations such as The Legal Aid Society in

New York City to provide legal services. See Matter of

The Associated Lawyers’ Co., 134 A.D. 350, 352, 119 N.Y.S.

77, 79 (1st Dep’t 1909). As with all charitable corporations

in New York, the formation of such corporations required

judicial approval.** With respect to legal assistance corpo

* Significantly, Section 495 (1 ) does not prevent a corporation

from providing persons with funds to engage attorneys, so long as the

corporation does not itself directly or indirectly select or control the

attorney. Matter of Prisoners Assistance Committee, Inc., 26 A.D.

2d 624, 272 N.Y.S.2d 700 (1st Dep’t 1966).

** The formation of a benevolent or charitable corporation in New

York has required the approval of a Justice of the Supreme Court

since 1848. See L. 1848, c. 319, § 1. This requirement is now con

tained in Section 404(a) of the New York Not-for-Profit Corpora

tion Law.

5

rations, this function of judicial approval was transferred

to the Appellate Division in 1909 by the enactment of what

is now Section 495(5) of the New York Judiciary Law.

Section 495(5) excepts from the general prohibition of

corporate practice of law

“ . . . organizations organized for benevolent or

charitable purposes, or for the purpose of assisting

persons without means in the pursuit of any civil

remedy, whose existence, organization or incorpora

tion may be approved by the appellate division of

the supreme court of the department in which the

principal office of such corporation or voluntary as

sociation may be located.”

From 1909 to 1966 the Appellate Division, First Depart

ment granted eleven applications for approval pursuant to

Section 495(5), including those of The Legal Aid Society

in 1909, N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. in 1940, and appellant A.C.L.U. Foundation, Inc. in

1966. During the same period the Appellate Division dis

approved four applications on the ground that they did

not come within the scope of Section 495 (5). The passage

of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which made fed

eral funds available for legal assistance corporations, stimu

lated numerous applications for approval from Community

Action for Legal Services, Inc. (“ CALS” ) and other pub

licly funded legal assistance corporations.

In Matter of CALS, 26 A.D.2d 354, 360-62, 274 N.Y.S.2d

779, 787-89 (1st Dep’t 1966), the Appellate Division unani

mously held, in an opinion by Judge Breitel, that the origi

nal CALS applications must be disapproved because they

lacked express safeguards against interference with the

6

attorney-client relationship and against improper referral,

solicitation, and fee-splitting. The CALS applications were

modified to meet the standards of the CALS decision, and

were approved in 1967. Meanwhile the number of applica

tions for approval under Section 495(5) continued to in

crease, and the Appellate Division decided to promulgate

rules embodying its general standards for approving ap

plications under Section 495(5).

2. Part 608 of the Rules of the Appellate Division

During the first half of 1970 the Appellate Division, First

Department drafted proposed rules and submitted them for

comment to The Legal Aid Society, CALS, and the major

bar associations in the First Department. After revision in

light of the comments received, the rules were promulgated

on May 20, 1970 as Part 608 of the Rules of the Appellate

Division, First Department. In December 1971 the Appel

late Division published a notice, which was also sent di

rectly to numerous interested parties, inviting further com

ments and suggestions on Part 608. Twenty-three individ

uals and organizations submitted comments, which were

given detailed consideration by the Appellate Division. On

November 30, 1972 the Appellate Division adopted amend

ments to Part 608, the main purpose of which was to mini

mize the burden of compliance with Part 608 to the maxi

mum extent compatible with the Appellate Division’s duties

of approval and supervision under Section 495(5).

Informational Provisions of Part 608. The provisions of

Part 608 are appended to the Jurisdictional Statement (J.S.

3a-14a). Several of these provisions are purely informa

tional. Rule 608.2 sets forth the information to be included

7

in initial applications. Rule 608.8 specifies the contents of

the annual reports of approved corporations. Rule 608.5

provides for an initial approval period of up to three years,

after which approval may be extended indefinitely, and

Rule 608.3 provides that applications for extension should

contain the same information as initial applications.

The information required by Rule 608.2 for initial and

renewal applications is designed to permit the Appellate

Division to determine whether the applications meet the

standards of Section 495(5) and the general criteria for

approval of a charitable corporation. In addition to the

name, address, and date of incorporation of the corporation

(Rule 608.2 (a), (b ) ), the rule seeks information concern

ing the corporation’s governing board (Rule 608.2 ( c ) ) and

the attorneys and law students employed by the corporation

to render legal services (Rule 608.2(f), (g )) . Such in

formation is intended to enable the Appellate Division to

assess the responsibility and experience of the corporation’s

governing board and attorneys, as well as the independence

of its practice of law from lay control. The rule also seeks

information regarding the benevolent nature of the legal

services to be performed (Rule 608.2 (d), (e ) ), in order to

determine whether the corporation’s activities will serve a

bona fide charitable purpose within the scope of Section

495(5).

In addition to the information required in initial and

renewal applications, Rule 608.8 specifies that annual re

ports of approved corporations shall include financial re

ports and copies of any report rendered to any state officer

or public funding body (Rule 608.8 (i), (j ) ) . It also re

quires information on referrals (Rule 608.8(f)), actions

8

brought against the corporation (Rule 608.8 (g ) ), and pub

licity concerning legal services disseminated by the corpora

tion to 100 or more persons (Rule 608.8(h)), to assist in

determining compliance with the guidelines adopted by the

Appellate Division for the solicitation, referral, and other

activities of the corporation.

Substantive Guidelines of Part 608. Rules 608.6 and

608.7 define guidelines to be followed by corporations ap

proved by the Appellate Division under Section 495(5),

unless other guidelines are approved by the Appellate Divi

sion in the case of a specific corporation. Rule 608.6 requires

that the practice of law by an approved corporation be

supervised by an autonomous and independent committee

of attorneys admitted to practice in New York, unless the

majority of the governing board of the corporation are

themselves attorneys admitted to practice in New York,

and that the autonomous committee or governing board

be responsible to the Court for the maintenance of proper

standards and ethics in the corporation’s practice of law.

Rule 608.7(a) contains guidelines for the use of law

students by approved corporations, and Rule 608.7(b)

authorizes such corporations to furnish legal services to

organizations that meet their standards of eligibility. Rule

608.7(c) provides that, unless otherwise ordered by the

Appellate Division, approved corporations shall not accept

contingent fee cases, and attorneys employed by publicly

funded corporations shall refrain from political activities

that would be prohibited by the Hatch Act. Rule 608.7(d)

restricts services rendered to officers or members of the

corporation to those that are reasonably related to the

primary purposes of the corporation. Rule 608.7(e) au

9

thorizes an approved corporation to give public notice of

its legal services (1) to its members, (2) to the general

public, if it is organized solely to provide legal services

to persons without means, and (3) by any other means con

sistent with the Code of Professional Responsibility.*

Finally, Rule 608.7(f), unless other fee and referral pro

cedures are authorized by the Appellate Division, bars the

acceptance of fees or compensation and forbids referrals

except to authorized bar referral services.

Standards Applied by the Appellate Division Under Sec

tion 495(5). Many of the standards applied by the Appel

late Division in granting approval under Section 495(5)

are implicit in the suggested guidelines of Rules 608.6 and

608.7. The remaining standards applied by the Appellate

Division stem from Section 495(5) itself, which appellants

do not attack. Section 495(5) expressly provides that a cor

poration that seeks approval under Section 495 (5) must be

organized “for benevolent or charitable purposes, or for the

purpose of assisting persons without means in the pursuit

of any civil remedy” . If the purposes of a corporation seek

ing approval do not come within these criteria, approval

must be denied. E.g., Matter of The Associated Lawyers’

Co., 134 A.D. 350, 119 N.Y.S. 77 (1st Dep’t 1909).

Moreover, by its reference to “benevolent or charitable

purposes,” Section 495(5) incorporates the standards for

approval which have been worked out by the New York

courts during the course of more than a century of approv

ing the incorporation of benevolent and charitable corpora

* DR 2-101 (A ) and DR 2-103 (D ) of the Code of Professional

Responsibility, which has been adopted by the New York State Bar

Association, contain provisions concerning the advertising of legal

services.

10

tions generally. These standards emphatically do not

include whether the court is in sympathy with the ideology

or goals of the proposed corporation. E.g., Gay Activists

Alliance v. Lomenzo, 31 N.Y.2d 965, 293 N.E.2d 255, 341

N.Y.S.2d 108 (1973); Association for the Preservation of

Freedom of Choice, Inc. v. Shapiro, 9 N.Y.2d 376, 174

N.E.2d 487, 214 N.Y.S.2d 388 (1961). They do, however,

include the responsibility of the corporation’s sponsors,

their experience and ability to attain the benevolent or

charitable goals of the corporation, and the existence of

some need for the corporation’s proposed activities. The

courts have held the same factors to be relevant in granting

approval under Section 495(5) of the Judiciary Law. E.g.,

Matter of Thom, 33 N.Y.2d 609, 610, 301 N.E.2d 542,

347 N.Y.S.2d 571 (1973) ; Matter of Bannerman, 39 A.D.

2d 894 (1st Dep’t 1972).*

Thus the standards for approval by the Appellate Divi

sion have been spelled out in Section 495(5), in Part 608,

and in decisions by New York courts approving the forma

tion of charitable corporations generally. The standards

for revocation of approval are even more sharply defined

by Rule 608.9, which provides that approval may be revoked

only after notice and opportunity for hearing, and only

“for significant violations of Part 608 of the court’s

rules, of the Code of Professional Responsibility, or

other applicable statutes and regulations, or because

the corporation, organization or association no

* Appellants criticize the Thom and Bannerman decisions at length

(J.S. 17-18) without adverting to the fact that they applied criteria

of responsibility, experience, and need that have historically been

applied to all forms of charitable corporations in New York. The

Thom application was granted by the Appellate Division on October

18, 1973. Matter of Thom, N.Y.L.J., Oct. 19, 1973, p. 1, col. 5.

11

longer meets the criteria required by Section 495 of

the Judiciary Law. . . . ”

3. The Present Action

Except for the appellant A.C.L.U. Foundation, Inc.—

which was approved by the Appellate Division under Sec

tion 495 (5) in 1966, but has not filed a renewal application

under Part 608—none of the appellants has ever sought the

approval of the Appellate Division under Section 495(5)

or Part 608. Instead, immediately after the promulgation

of Part 608 in 1970, appellants commenced the present ac

tion and sought a preliminary injunction against the ap

plication of Part 608.

Appellants expressly stated that they were not question

ing the validity of Part 608 as applied to publicly funded

legal assistance corporations like CALS and The Legal Aid

Society (March 25,1971 hearing, p. 11). Appellants argued,

however, that it is unconstitutional to apply to them any

process of supervision that goes beyond

“trivial matters like filing our name and our ad

dress and our telephone number and filing the same

kind of financial statement that we file with the tax

authorities.” (March 25, 1971 hearing, p. 12.)

On May 19, 1971 the three-judge District Court denied

appellants’ motion for a preliminary injunction, holding

that appellants should at least apply to the Appellate Divi

sion for approval:

“ That the Appellate Division invites applications

for approval and for exceptions from plaintiff Legal

Rights Organizations and that these would be con

sidered sympathetically was made clear by counsel

12

for defendants at the hearing of this motion on

March 25, 1971. It is thus appropriate for this statu

tory Court to stay its hand to permit defendants to

consider, and perhaps resolve, the constitutional

issues raised in this complaint. No harm is fore

seeable to plaintiffs since counsel for defendants

represented at the hearing that the Appellate Divi

sion will not seek to impose any sanctions on plain

tiffs until thirty days after final disposition of this

action.” 328 F. Supp. 66, 68-69 (S.D.N.Y. 1971).

Appellants did not apply to the Appellate Division for

approval. Nor did they appeal to this Court from the denial

of the preliminary injunction. Instead, secure in the Appel

late Division’s assurance that the status quo would be main

tained pending final disposition of the action, appellants

did nothing for almost two years, until the District Court

suggested during the course of a routine calendar review

that the action might be dismissed for lack of prosecution.

Appellants then moved for summary judgment. The three-

judge District Court, adhering to its earlier holding, denied

summary judgment, and dismissed the complaint without

prejudice to renewal of the action after appellants had

applied to the Appellate Division. 360 F. Supp. 581, 582

(S.D.N.Y. 1973). This appeal is taken from the judgment

dismissing the complaint.

ARGUMENT

Appellants strive to depict this appeal as one involving

fundamental substantive questions of nationwide import

ance concerning the constitutionality of state regulation of

the practice of law by organizations (J.S. 9-11). In fact,

this appeal involves no such questions. The only question

13

presented by this appeal is a procedural one: whether the

District Court correctly held that appellants should first

apply to the Appellate Division for approval and for any

exceptions from the general guidelines of Part 608 that are

appropriate for their activities, so that it can be determined

whether there are in fact any concrete disagreements be

tween appellants and the Appellate Division and, if so,

what is their nature and scope.

This holding of the District Court was plainly a judicious

and common-sense resolution of the procedural issue. In

attacking it, appellants are forced into the extreme posi

tion that the First Amendment forbids any state supervision

of the practice of law by charitable corporations (J.S. 12-

21). Appellees will first show that this extreme position is

not supported by the decisions of this Court, and will then

demonstrate that the holding of the District Court that

appellants should first apply to the Appellate Division is in

accord with the decisions of this Court.

I.

The First Amendment and the Equal Protection

Clause Do Not Bar State Supervision of the Practice

of Law by Charitable Corporations.

The decisions of this Court in NAACP V. Button, 371

U.S. 415 (1963), Brotherhood of R.R. Trainmen v. Virginia

ex rel. Virginia State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964), UMW v.

Illinois State Bar Ass’n, 389 U.S. 217 (1967), and United

Transportation Union v. State Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S.

576 (1971), establish that the practice of law by charitable

corporations such as appellants is within the right of as

14

sociation protected by the First Amendment, which is made

applicable to the States by the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. However, these decisions also

demonstrate that the First Amendment right of organiza

tions to practice law is not an absolute right which fore

closes any state supervision of the practice of law by chari

table corporations.

NAACP V. Button involved a Virginia statute that had

been construed by the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals

to prohibit the NAACP from recommending or furnishing

attorneys in connection with any litigation to which it was

not a party and in which it had no pecuniary interest. 371

U.S. at 423-26, 434-35. The Court held that such a broad

prohibition “could well freeze out of existence all such ac

tivity on behalf of the civil rights of Negro citizens.” 371

U.S. at 436. After reviewing the factual record concerning

the NAACP’s activities in Virginia, the Court concluded

that the record did not justify the complete prohibition of

the NAACP’s activities. 371 U.S. at 442-44. The Brother

hood, UMW, and UTU cases involved state court decrees

that prohibited unions from recommending or employing

attorneys to represent their members in accident cases.

Following NAACP v. Button, the Court held that the facts

before it in those cases did not justify such a broad pro

hibition.

Thus NAACP V. Button and each of the decisions which

followed it held that, on the facts before the Court, the First

Amendment did not permit the State to prohibit absolutely

the practice of law by the organizations before the Court.

Not one of the decisions stated that the First Amendment

right of an organization to practice law is an absolute right

15

which cannot be subjected to reasonable state supervision

and informational requirements.* None of the decisions

held that there is an absolute First Amendment right to

form a charitable corporation to practice law, free of the

requirements of judicial approval and state supervision

which apply to all other charitable corporations. Not one

of the decisions held a state statute or rule regulating the

organizational practice of law invalid on its face and in its

entirety—the relief which appellants demand in the present

case.

The facts of the Brotherhood and TJTU cases are equally

inconsistent with appellants’ argument that the First

Amendment bars any state regulation of the practice of

law by organizations. In Brotherhood, this Court specif

ically noted that certain portions of the Virginia decree,

which enjoined the union and its regional investigators from

fee-splitting with the attorneys they recommended, were

not challenged. 377 U.S. at 5 n.9. In UTU, the record

showed that the union had been operating since 1958 under

an Illinois court decree which enjoined the union, among

other things, from using its investigators to obtain contracts

for the employment of union-recommended attorneys, and

from splitting fees with attorneys. 401 U.S. at 589-90

(Harlan, J., dissenting). Nothing in the opinion of the

Court suggested that the Illinois decree was invalid; indeed,

the Court reversed a provision in the Michigan decree pro

* This fact is especially significant because the Court’s opinions in

the Brotherhood, UMW, and UTU cases were written by Mr. Justice

Black, who expressed with great force and conviction the belief that

other First Amendment rights are absolute. See, e.g., Cox v. Louisi

ana, 379 U.S. 559, 578 (1965) (concurring and dissenting opinion) ;

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 293 (1964) (concur

ring opinion); Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 366 U.S. 36,

60-62 (1961) (dissenting opinion).

16

hibiting fee-splitting, not on the ground that the First

Amendment required Michigan to permit fee-splitting, but

on the ground that the record in the Michigan case (as dis

tinguished from the Illinois case) contained no evidence of

fee-splitting. 401 U.S. at 582-84.

Finally, the opinions of the Court in NAACP V. Button

and the cases following it demonstrate that the hazards of

organizational interference with the attorney-client rela

tionship and of improper solicitation, fee-splitting, and

referral are genuine concerns that justify careful state

oversight of the activities of legal assistance corporations

(although the Court found that these hazards had not ma

terialized in the specific cases before it ) . Thus, for example,

the Court stated in NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 444

(1963) :

“Nothing that this record shows as to the nature and

purpose of NAACP activities permits an inference

of any injurious intervention in or control of litiga

tion which would constitutionally authorize the ap

plication of Chapter 33 to those activities.”

Mr. Justice White stated in a separate opinion:

“ If we had before us, which we do not, a narrowly

drawn statute proscribing only the actual day-to-

day management and dictation of the tactics, strat

egy and conduct of litigation by a lay entity such

as the NAACP, the issue would be considerably dif

ferent, at least for me; for in my opinion neither

the practice of law by such an organization nor its

management of the litigation of its members or

others is constitutionally protected. Both practices

are well within the regulatory power of the State.”

371 U.S. at 447.

17

Lower court decisions following the Button, Brotherhood,

UMW, and UTU decisions have consistently held that these

decisions do not foreclose state regulation of improper

solicitation, fee-splitting, and referral in connection with

the practice of law. E.g., In re Fleck, 419 F.2d 1040, 1041,

1046 (6th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 1074 (1970)

(improper solicitation and contingent fees) ; Hiett V. United

States, 415 F.2d 664, 673 (5th Cir. 1969) (dictum), cert,

denied, 397 U.S. 936 (1970) (fraudulent solicitation);

State exrel. Farberv. Williams, 183 So. 2d 537, 538 (Fla.),

cert, denied, 385 U.S. 845 (1966) (improper solicitation);

Commonwealth v. Hayden, 489 S.W.2d 513, 515 (Ky. 1972)

(improper referral by bail bondsman); In re Jones, 431

S.W.2d 809, 818 (Mo.), cert, denied, 385 U.S. 866 (1966)

(improper referral and fee-splitting) ; State ex rel. State

Bar of Wisconsin v. Bonded Collections, Inc., 36 Wis. 2d 643,

154 N.W.2d 250, 258-59 (1967) (corporate practice of

law).

The First Amendment issue in the present case is even

more limited: whether the First Amendment prohibits a

State from seeking information concerning the practice of

law by charitable corporations, and from prescribing guide

lines for such corporations in the potential problem areas

of lay control, solicitation, referral, and fee-splitting,

unless facts supporting different guidelines in the case of

a specific corporation are brought forward by the corpora

tion. As shown above (pp. 6-9), the requirements of

Part 608 amount to no more than this. Such requirements

of coming forward with evidence with respect to matters

peculiarly within an applicant’s own knowledge in the area

of admission to the practice of law were upheld against

First Amendment attack in Law Students Civil Rights

18

Research Council, Inc. v. Wadmond, 299 F. Supp. 117, 125

(S.D.N.Y. 1969), aff’d, 401 U.S. 154, 157-60 (1971).

Appellees submit that Law Students equally establishes the

validity of Part 608.

The nature of appellants’ First Amendment attack on

Part 608 is difficult to define. It is plainly not an attack

on Part 608 as construed and applied, because appellants’

very purpose in taking the present appeal is to deny the

Appellate Division any chance to construe Part 608 as

applied to appellants. However, as appellants concede (J.S.

16), appellants do not contend that Part 608 is invalid on

its face, because they admit that there are corporations to

which Part 608 may constitutionally be applied.* Despite

the difficulty of finding an analytical basis for appellants’

First Amendment attack on Part 608, their ultimate

aim is clearly defined by their statements in the District

Court: appellants’ aim is to establish that the First Amend

ment prohibits any supervision of their activities beyond

“ trivial matters” such as their name, address, and financial

statements (see p. 11 supra).

Appellants’ principal argument, made in Point I of their

Jurisdictional Statement (J.S. 12-18), is that Part 608

is invalid under the First Amendment licensing cases (J.S.

14-16). Even assuming that the licensing cases are an

alogous to this case, they do not hold that a First Amend

* Appellants have consistently conceded that there are legal assist

ance corporations to which Part 608 may constitutionally be applied.

In the District Court, appellants did not challenge the validity of Part

608 as applied to publicly funded legal assistance corporations like

CALS and The Legal Aid Society (Reply Brief dated March 23,

1971, p. 11; March 25, 1971 hearing, p. 11). Even in this Court, ap

pellants concede the validity of Part 608 as applied to “ a group formed

to provide legal services for profit in criminal or negligence cases”

(J.S. 16).

19

ment right may not be made the subject of a requirement

of application and approval, and still less that such a re

quirement may not be applied to charitable corporations

that practice law. Rather, they establish that such a re

quirement must be guided by reasonable and defined stand

ards, and must be expeditiously conducted. E.g., Shuttles-

worthv. City of Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147, 150-53 (1969).

Part 608 meets these requirements. Appellants repeat

edly stigmatize Part 608 as “ standardless” {e.g., J.S. 16),

but in fact, as shown above (pp. 9-11), the standards

applied by the Appellate Division in granting approval

under Section 495(5) are apparent from Section 495(5)

itself, from Part 608, and from the standards used by the

New York cofirts in approving the formation of charitable

corporations generally. As in the case of the standard of

“ character and general fitness” for admission to the Bar

sustained by this Court in Law Students Civil Rights Re

search Council, Inc. v. Wadmond, 401 U.S. 154, 159 (1971),

history has defined the contours of these standards.*

Point II of the Jurisdictional Statement (J.S. 18-20)

asserts that New York has no substantial regulatory

interest justifying the requirement of Appellate Division

approval and supervision of the practice of law by chari

table corporations under Section 495 (5) and Part 608. This

assertion is mistaken.

Section 495(5) and Part 608 serve three substantial state

interests. The first is the interest, which applies to all

* Appellants suggest that the Appellate Division was guilty of undue

delay in passing upon the application for approval in the Bannerman

case (J.S. 19 n.21). In fact, the lapse of time in Bannerman was due

chiefly to lengthy delays by the applicants in responding to the Ap

pellate Division.

20

charitable corporations, in assuring the responsibility and

experience of the corporation’s sponsors, their adherence

to the charitable goals of the corporation, and the existence

of some need for the corporation’s proposed activities (see

pp. 9-10 supra). The second is the strong interest in

guarding against organizational or lay interference with

the basic relationship between attorney and client in litiga

tion sponsored by the corporation, an interest whose legiti

macy was affirmed in NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 444

(1963), id. at 447 (separate opinion of White, J.). The

third is the interest in guarding against such practices as

unjustified or misleading solicitation, fee-splitting, or re

ferral (see pp. 4, 5-6, 17 supra). These potential problems

are also present in the case of individual attorneys, but

the probability of their occurrence is heightened in the case

of corporations that are permitted to solicit funds to provide

legal services to others and to advertise the availability of

their legal services.

Appellants also argue in Point II of their Jurisdictional

Statement that Part 608 violates the Equal Protection

Clause because Section 495 of the New York Judiciary

Law permits the practice of law by trust companies,

title companies, insurance companies, and professional cor

porations organized under Article 15 of the New York

Business Corporation Law (J.S. 18-19).

The fallacy in this argument is simply that none of these

organizations is permitted to engage in a business of fur

nishing legal representation to others that is in any way

comparable to appellants’. Counsel for a trust company rep

resents the trust company itself, not the beneficiaries of

the trust, so that the trust company does not furnish counsel

21

for others. A title company is permitted to practice law

only to the extent of drafting routine conveyancing in

struments, on the ground that such instruments can be as

adequately drafted by laymen as by attorneys.* In the

case of liability insurance, the furnishing of counsel by the

insurance company to the insured is ancillary to a pre

existing contract of liability insurance; the attorney’s duty

is solely to the insured,** and the performance of this

duty is buttressed by the fact that the insurance company

itself may be liable in damages for any failure to handle

a litigation in good faith for the benefit of the insured.***

Finally, a professional corporation under Article 15 of the

Business Corporation Law is simply an incorporated law

firm, and is permitted to render only those professional

services that it would be permitted to render without in

corporating under Article 15. See N.Y. Bus. Corp. Law

1 1503(a). Article 15 of the Business Corporation Law

does not authorize a professional corporation to solicit funds

to provide legal services for the charitable purposes de

scribed in Section 495(5) of the Judiciary Law or to

advertise the availability of its legal services, as appellants

seek to do. Thus an organization whose activities subject it

to Section 495 cannot, as appellants assume, escape Section

495 by incorporating under Article 15.

In Point III of their Jurisdictional Statement (J.S.

20-21), appellants attack three individual provisions of

* See People v. Lawyers Title Corp., 282 N.Y. 513, 520-21, 27 N.E.

2d 30, 33-34 (1940) ; People v. Title Guarantee & Trust Co., 227 N Y

366, 373, 377, 125 N.E. 666, 668, 669 (1919).

** E.g., ABA, Opinions of the Committee on Professional Ethics,

Formal Opinion 282, at 623 (1967).

*** See, e.g., Best Bldg. Co. v. Employers’ Liab. Assurance Corp.,

247 N.Y. 451, 453, 160 N.E. 911, 912 (1928).

22

Part 608. Appellants first argue that the annual report

requirements of Rule 608.8 violate their First Amendment

right of privacy. But, for the reasons given above (pp.

14-18), New York may constitutionally seek information

concerning the activities of charitable corporations engaged

in the practice of law. The information sought by Part

608 (set forth at pages 7-8 above) is comparable to that

required in the federal income tax returns and state reports

of any charitable organization, and would also normally

be required by a diligent board of trustees of a charitable

organization.

Second, appellants contend that Rule 608.7(e) prevents

them from discussing litigation with potential litigants;

but, as explained above (pp. 8-9), Rule 608.7(e) expressly

authorizes an approved corporation to give public notice

of its legal services to members and to persons without

means, and a corporation may secure Appellate Division

approval for even wider public information programs.

Rule 608.7 (e) thus serves to permit the Appellate Division

to supervise the public information programs of approved

corporations; and, as shown above (pp. 14-18), there is no

absolute First Amendment right to solicit potential litigants

without judicial supervision.*

Third, appellants attack Rule 608.7(f), which requires

that any program of fee-splitting and private referral be

approved by the Appellate Division. Such supervision is

plainly justified by the dangers of commercialism and

* See also Boshes v. General Motors Corp., No. 70-244, cert, de

nied, 404 U.S. 872 (1971), an antitrust class action in which the

plaintiff unsuccessfully challenged on First Amendment grounds a rule

of the Northern District of Illinois requiring prior judicial approval

of all communications with prospective class members.

23

favoritism that unsupervised fee-splitting and referral

might well generate (see pp. 15-17 supra) *

Finally, appellants suggest in a single paragraph (J.S.

11) that Part 608 contravenes the Supremacy Clause. On

the contrary, it is well established that the area of ad

mission to the practice of law is a state rather than a

federal responsibility. See, e.g., Law Students Civil Rights

Research Council, Inc. v. Wadmond, 401 U.S. 154, 167

(1971); Erdmann v. Stevens, 458 F.2d 1205, 1210 (2d

Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 889 (1972); West Virginia

State Bar v. Bostic, 351 F. Supp. 1118, 1121 (S.D.W. Va.

1972).

II.

The District Court Correctly Held that Appellants

Should First Apply for Approval to the Appellate

Division.

In Point IV of their Jurisdictional Statement (J.S.

21-24), appellants finally come to the question actually

presented by this appeal: whether the Distinct Court cor

rectly dismissed the complaint upon the ground that ap

pellants should first apply to the Appellate Division for

approval. Appellees submit that this holding was correct,

for four basic reasons.

Abstention. First, many of appellants’ objections—includ

ing any residual uncertainty appellants feel concerning the

standards embodied in Section 495(5) and Part 608— can

* In UTU v. State Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S. 576, 582-84 (1971),

the Court avoided holding that fee-splitting is protected by the First

Amendment, holding instead that the record contained no evidence

that fee-splitting had occurred.

24

be authoritatively resolved through a construction of Sec

tion 495(5) and Part 608 as a matter of New York State

law by the Appellate Division and the New York Court

of Appeals. Accordingly, under the doctrine of abstention,

the federal courts should stay their hand to permit the New

York State courts to resolve these issues of New York

State law. C/., e.g., Lake Carriers'1 Assn. v. MacMullan,

406 U.S. 498, 510-12 (1972); Kiernan v. Lindsay, 334 F.

Supp. 588, 596-97 (S.D.N.Y. 1971), aff’d, 405 U.S. 1000

(1972).

This was precisely the holding of this Court in the only

previous case in which a federal court injunction was sought

against a state statute or rule regulating the practice of

law by organizations, Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U.S. 167

(1959). In that case the Court held:

“ [N]o principle has found more consistent or clear

expression than that the federal courts should not

adjudicate the constitutionality of state enactments

fairly open to interpretation until the state courts

have been afforded a reasonable opportunity to pass

upon them. . . .

The present case, in our view, is one which calls

for the application of this principle, since we are

unable to agree that the terms of these three statutes

leave no reasonable room for a construction by the

Virginia courts which might avoid in whole or in

part the necessity for federal constitutional adjudi

cation, or at least materially change the nature

of the problem.” 360 U.S. at 176-77.

Exhaustion of State Administrative Remedies. The Dis

trict Court held that appellants should apply to the Appellate

25

Division under the doctrine of exhaustion of state ad

ministrative remedies which was enunciated in Prentis v.

Atlantic Coast Line Co., 211 U.S. 210, 226-30 (1908). 328

F. Supp. 66, 68 (S.D.N.Y. 1971). Appellants correctly

note (J.S. 22) that the present action is brought under

42 U.S.C. § 1983, and that this Court has not generally

required exhaustion of state administrative remedies in

actions brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. See, e.g., Carter

v. Stanton, 405 U.S. 669, 671 (1972). However, this Court

noted in Gibson v. Berry hill, 411 U.S. 564, 574-75 (1973),

that the doctine of exhaustion of state administrative

remedies may still apply in certain exceptional cases brought

under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

Appellees suggest that the present case is such an ex

ceptional case because it is not ripe for review by the Dis

trict Court, and will not be ripe until appellants have ex

hausted their administrative remedy by applying to the

Appellate Division. Under the standards of ripeness formu

lated in Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U.S. 136, 148-

51 (1967), the present case is not ripe for review because

the Appellate Division has not yet formulated the concrete

and definitive rules governing appellants’ activities. Part

608 is not a self-applying set of rules; instead, its purpose is

to provide a framework within which the Appellate Division

can determine what rules ought to apply to a specific cor

poration, by setting forth the information to be supplied to

the Appellate Division and the guidelines to be followed by

approved corporations unless other guidelines are approved

by the Appellate Division.

Thus appellants should be required to apply to the Appel

late Division for approval, not merely because the Appellate

26

Division may fairly be expected to respect appellants’

constitutional rights, but also because there can be no con

crete or definitive administrative determination, ripe for

review by the District Court, until the Appellate Division

has passed upon appellants’ applications.

Federal-State Comity. The principle of federal-state com

ity also supports the holding of the District Court. Appel

lants’ attempt to obliterate Part 608 without giving the

Appellate Division any opportunity to apply it runs counter

to this Court’s holding in Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37,

52 (1971), that

“Procedures for testing the constitutionality of a

statute ‘on its face’ in the manner apparently con

templated by Dombrowski, and for then enjoining

all action to enforce the statute until the State can

obtain court approval for a modified version, are

fundamentally at odds with the function of the

federal courts in our constitutional plan.”

The general question whether Younger V. Harris governs

a case in which there is no pending state criminal pro

secution is now before this Court in Speight v. Slaton, No.

72-1557, prob. juris, noted, 42 U.S.L.W. 3174 (U.S. Oct.

9, 1973). Regardless of how this question may be resolved

as a general matter, Younger v. Harris should be followed

where the appellants are attempting to use a federal in

junction suit to block the supervisory authority of a state

court over the practice of law, which has traditionally

been recognized as an area of peculiar state concern. Cf.,

e.g., Erdmann v. Stevens, 458 F.2d 1205, 1210 (2d Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 889 (1972).

27

Lack of Irreparable Injury. The fourth ground sup

porting the District Court’s action is that, although appel

lants demanded an injunction against Part 608, they failed

to demonstrate that they would suffer irreparable injury

by applying to the Appellate Division. Appellants sub

mitted to the District Court affidavits, all but one executed

by officers of the appellants themselves, stating in con-

clusory terms that Part 608 would have an inhibiting and

curtailing effect upon appellants’ operations and contrib

utors (J.S. 8-9). The District Court correctly found that

these concl usory affidavits did not establish that a simple

requirement of application to the Appellate Division be

fore proceeding in the District Court would have a meas

urable chilling effect. Instead, the District Court found in

1971 and again in 1973 that

“ No harm is foreseeable to plaintiffs since counsel

for defendants represented at the hearing that the

Appellate Division will not seek to impose any sanc

tions on plaintiffs until thirty days after final dis

position of this action.” 328 F. Supp. 66, 69 (S.D.

N.Y. 1971); 360 F. Supp. 581, 582 (S.D.N.Y. 1973).

The Appellate Division has no intention of violating the

constitutional rights of any of the appellants. The Appellate

Division sincerely respects the efforts of legal assistance

corporations to vindicate fundamental constitutional liber

ties through litigation, and Part 608 is in no way intended

to choke off such efforts. The Appellate Division should be

given an opportunity to perform its duty of review and

approval under Section 495(5) of the New York Judiciary

Law, through the orderly procedure of application pre

scribed by Section 495(5).

28

CONCLUSION

For the reasons given above, the judgment of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of New

York entered on June 21, 1973 should be affirmed or, in

the alternative, the appeal should be dismissed.

Dated: New York, New York

November 7, 1973

Respectfully submitted,

Louis J. Lepkowitz

Attorney General of the

State of New York

2 World Trade Center

New York, New York 10047

Daniel M. Cohen

Assistant Attorney

General

Lawrence E. W alsh

1 Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

(212) 422-3400

George A. Brownell

Guy Miller Struve

Of Counsel

Attorneys for Appellees