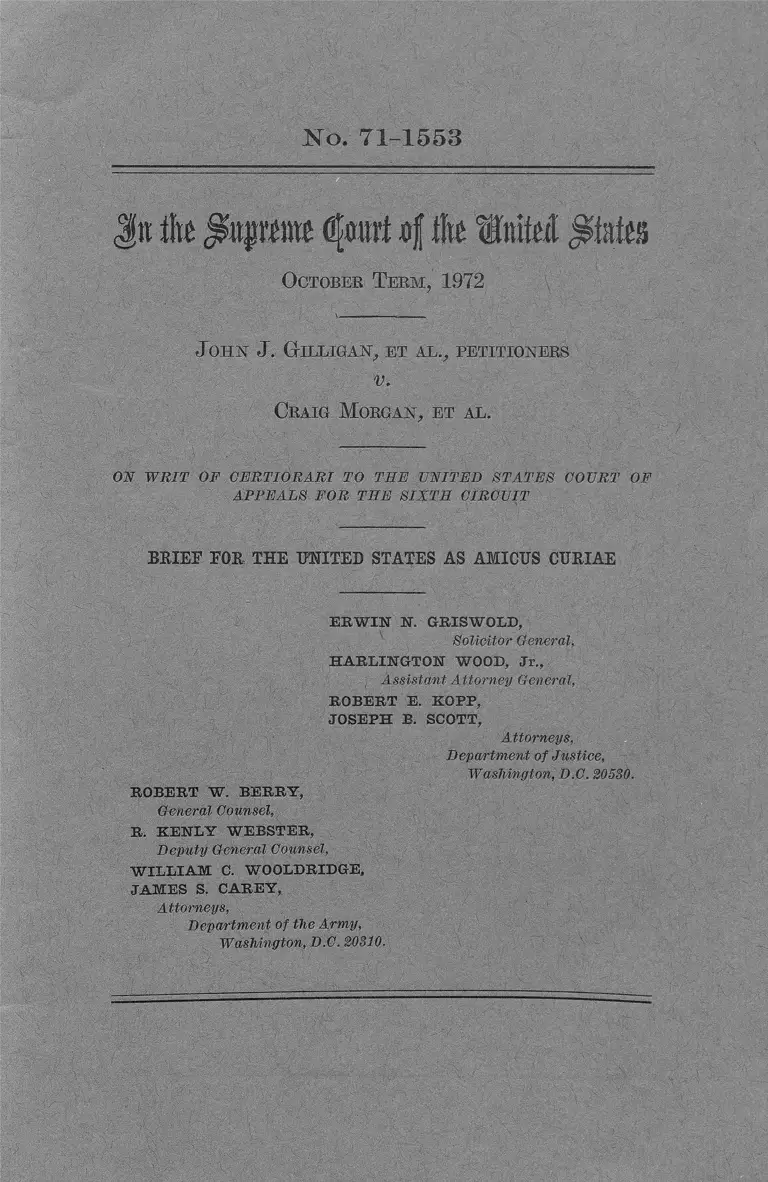

Gilligan v. Morgan Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1972

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gilligan v. Morgan Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1972. 9e382f5f-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b99fb18e-9619-41e3-835b-526ad94cebc6/gilligan-v-morgan-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

N o. 71-1553

i t j&tjrtmt d̂ iu't 4 i t $itts

October T erm , 1972

J ohn J . G illigan, et al., petitioners

v.

Craig M organ, et al.

ON W R IT OF C E R T IO R A R I TO T H E U NITED S T A T E S COURT OF

A P P E A LS FO R T H E S IX T H C IRCU IT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

ERW IN N. GRISWOLD,

Solicitor General,

HARRINGTON WOOD, Jr.,

A ssistan t A ttorney General,

ROBERT E. KGPP.

JOSEPH B. SCOTT,

Attorneys,

D epartm ent o f Justice,

W ashington, D.C. 20530.

ROBERT W. BERRY,

General Counsel,

R. KENLY WEBSTER,

D eputy General Counsel,

WILLIAM C. WOOLDRIDGE,

JAMES S. CAREY,

Attorneys,

D epartm ent of the Arm y,

W ashington, D C. 20310.

I N D E X

Page

Opinion below___________ 1

Jurisdiction. _____________________________ 1

Statute and regulations involved_____________ 2

Questions presented____________ 2

Interest of the United States________________ 3

Statement------ ---------------------------------------- 3

Summary of argument_____________________ 4

Argument:

I. Introduction: the statutory and regu

latory context___________________ 5

A. The National Guard_________ 6

B. The role of the Federal Govern

ment in training the Army

National Guard___________ 9

C. Rules pertaining to the use of

force_______ 12

1. Army use-of-force rules __ 13

2. Ohio use-of-force rules__ 14

II. Respondents’ claim—that the training,

weapons, and orders of the Ohio Na

tional Guard deprive or threaten to

deprive them of their constitutional

rights—is not justiciable___________ 15

III. Respondents have no standing to main

tain this suit____________________ 20

A. Respondents have not identified

a sufficient threat of specific

future harm to justify invoking

the judicial process________ 22

a)

497- 185— 73-------------1

II

Argument—Continued

III.—Continued

A. —Continued

1. The single incident at

Kent State in May 1970

does not pose a sufficient

threat of repetition to

warrant judicial interven- Page

tion________________ 22

2. Respondents have no

standing for the further

reason that the Na

tional Guard practices

and policies on which

their case is based no

longer exist_________ 22

B. Respondents’ suggestion of a

“chilling” effect on their First

Amendment rights is insub

stantial_________________ 27

Conclusion_______________________________ 28

Appendix A______________________________ 29

Appendix B______________________________ 41

CITATIONS

Cases:

Arrow Transportation Co. v. Southern R. Co.,

372 U.S. 658_______________________ 17

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186_____________ 5, 21

Belknap v. Leary, 427 F. 2d 496_______ 23, 24, 25

Cottonreader v. Johnson, 252 F. Supp. 492___ 23

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83______________ 21, 24

Gomez v. Layton, 394 F. 2d 764___________ 23

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496____________ 22, 23

Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1___ 5, 17, 21, 25, 27, 28-

I ll

Cases—Continued page

Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F. 2d 197------------- 23

Levitt, Ex parte, 302 U.S. 633------------------- 22

Lewis v. Kugler, 446 F. 2d 1343---------------- 23

Linda R. S. v. Richard I)., No. 71-6078,

decided March 5, 1973________________ 21

McAbee v. Martinez, 291 F. Supp. 77_____ 19

Moose Lodge No. 107 v. /m s, 407 U.S. 163___ 21

Orloff v. Willoughby, 345 U.S. 83__________ 19

Poe v. Ulbnan, 367 U.S. 497_____________ 22

Schnell v. City of Chicago, 407 F. 2d 1084___ 23

Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727_______ 21

Tileston v. Ulhnan, 318 U.S. 44_.__________ 24

United States v. Fruehauf, 365 U.S, 146____ 17

Constitution and statutes:

United States Constitution:

Article I, Section 8, cl. 15____________ 2, 6

Article I, Section 8, cl. 16____________2, 6, 9

Article III_______________________ 21

First Amendment__________________ 5, 27

Army Reorganization Act of 1901, 31 Stat.

748_______________________________ 7

Dick Act of 1903, 32 Stat. 775___________ 7

National Defense Act of 1916, 39 Stat. 166

as amended, now 32 U.S.C. 101, et seq__ 7

10 U.S.C. 511(d)__________________ 10

32 U.S.C. 105_________ 8

32 U.S.C. 108____________________ 8

32 U.S.C. 109(c)__________________ 8

32 U.S.C. 110_____________________ 2, 8

32 U.S.C. 502____________________ 8

32 U.S.C. 502(a)(1)________________ 11

32 U.S.C. 502(a)(2)________________ 12

32 U.S.C. 502(d)(3)________________ 11

32 U.S.C. 510(b)(2)________________ 11

IV

Constitution and statutes—Continued

Ohio Revised Code:

§ 5923.1 (1971 Supp.)_______ _

§ 5923.21_________________ „______

§ 5923.22 (1971 Supp.)______________

§ 5923.28 (1971 Supp.)______________

Miscellaneous:

Army Subject Schedule 19-8, “Control of Civil

Disturbances”_______________________ 10

53 Cong. Rec. 4356____________________ 8

Field Manual 19-15, “Civil Disturbances and

Disasters”, dated March 25, 1968_______ 13

H. Rep. No. 297, 64th Cong., 1st Sess_____ 7

Weiner, Militia Clause of the Constitution, 54

Harv. L. Rev. 181(1940)______________ 7

CO

f

fl

CO

(

O

J t t M Gjmtrf of {ft 1 1 ' n M S ta te s

October Term , 1972

No. 71-1553

J ohn J . Gjlligan, et al., petitioners

v.

Craig M organ, et al.

ON W R IT OF C E R T IO R A R I TO T H E U NITED S T A T E S COURT OF

A P P E A L S FO R T H E S IX T H C IRC U IT

BRIEF FOR TEE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (Pet. App. 11-35)

is reported sub nom. Morgan v. Rhodes at 456 P. 2d

608.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered

on February 15, 1972. On May 15, 1972, Mr. Justice

Stewart extended the time for filing the petition for

a writ of certiorari to May 22, 1972. The petition was

filed on May 20, 1972, and was granted on October 24,

1972. The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C.

1254(1).

(i)

2

STATUTE A M REGULATION INVOLVED

32 U.S.C. 110 provides:

The President shall prescribe regulations, and

issue orders, necessary to organize, discipline,

and govern the National Guard.

The pertinent federal and state regulations are set

forth in the Appendix, infra pp. 29-45.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether respondents’ claim—that the training,

weapons, and orders of the Ohio National Guard

deprives or threatens to deprive them of constitutional

rights—is justiciable.

2. Whether respondents have standing to bring this

suit.

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

Pursuant to its authority under Article I, Section

8, els. 15 and 16 of the Constitution and 32 U.S.C. 110,

the United States, through the Department of the

Army, trains members of National Guard units for

civil disturbance control duties. I t is therefore the

Army’s training policies and practices which the court

of appeals has ordered the district court to review.

Furthermore, while operational decisions, such as the

kind and amount of force to be used in controlling

civil disturbances, are left to the states, the Army and

the State of Ohio now observe the same rules per

taining to the use of force in civil disturbances. The

policies and practices of the Army with respect to

the use of force therefore would be implicated in

the review the district court has been directed to

3

undertake. Accordingly, the United States has a sub

stantial interest in this case.

STATEMENT

Respondents, on behalf of themselves and all other

students at Kent State University, filed a complaint in

the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Ohio, seeking declaratory and injunctive

relief. The complaint, which seeks generally to enjoin

the Ohio National Guard from suppressing any future

civil disturbances on the Kent State campus until its

training and its operating policies have been changed,

was dismissed by the district court for failure to state

a claim for which relief could be granted (App. 14).

The court of appeals App. 22).

Although the complaint (which is set forth at App.

3-13) is discursive, the court of appeals construed it

as attempting to state three related causes of action.

The court unanimously affirmed the dismissal of two

of those causes of action, and respondents have not

sought certiorari with respect to those claims. How

ever, a divided court reversed the dismissal of the

third cause of action, which the court read as raising

the following question (Pet. App. 18) :

Was there and is there a pattern of training,

weaponing and orders in the Ohio National

Guard which singly or together require or make

inevitable the use of fatal force in suppressing

civilian disorders when the total circumstances

at the critical time are such that nonlethal force

would suffice to restore order and the use of

lethal force is not reasonably necessary? [Italics

omitted.]

4

The court in effect held that this question fairly stated

a claim that the actions of the Ohio National Guard

threatened to deprive respondents of life without due

process of law, that the claim so stated was justiciable,

and that if the claim were sustained, appropriate

injunctive relief could be fashioned (Pet. App.

18- 21).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

For two separate reasons, respondents’ contention—

that the training, weapons and orders of the Ohio

National Guard deprives or threatens to deprive them

of constitutional rights—does not create a justiciable

controversy: (1) respondents’ complaint does not state

a justiciable claim and (2) respondents have no stand

ing to maintain this suit.

1. Respondents seek judicial review of the pro

piety of the training, weapons and orders of the Na

tional Guard. That issue lacks the specificity required

for adjudication and would involve the judiciary in

inquiries which call for specialized knowledge and

skills which it does not possess. The determination of

the proper way in which to prepare members of the

National Guard for the performance of their military

duties must be made by the military. Moreover, judi

cial prescription, through the use of injunctive

powers, of the manner in which the Guard should

deal with civilian disorders is singularly inappro

priate. The military authorities should not be placed

within the constraint of a judicial order telling them how

to operate in the midst of the stress, confusion, and

unexpected crises which characterize civil dis

turbances.

5

2. Respondents have not shown “a personal stake

in the outcome of the controversy.” Baker v. Carr,

369 U.S. 186, 204. Respondents claim that the “rules,

procedures and operating methods followed by the

Ohio National Guard” (Br. 2) subject them to a con

tinuing threat of future deprivations of their con

stitutional rights. But their claim of future harm is

wholly speculative. The May 1970 shootings at Kent

State, tragic as they were, do not by themselves justify

fears of a recurrence of such incidents. Moreover,

since that time there have been substantial revisions

in the rules employed by the Guard with respect to

the use of force in civil disorders, and these revisions

eliminate the source of much of respondents’ ex

pressed concern for the future. Furthermore, respond

ents’ suggestion that the practices and policies of the

Guard intimidate them in the exercise of their First

Amendment rights has no objective basis. According

ly, respondents fail to show “ specific present objective

harm or a threat of specific future harm * * * [and

therefore] * * * on this record the respondents have

not presented a ease for resolution by the courts.”

Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1,14-15.

ARGUMENT

I. INTRODUCTION : THE STATUTORY AND REGULATORY

CONTEXT

The pertinent federal and state statutes and regula

tions are of crucial importance, and we discuss them

below in detail, since in our view they deserve more

emphasis than has been given them by the court below,

and by the parties and amici here in their briefs.

6

In order that the full setting may be before the

Court, we will first describe the constitutional basis

for the National Guard system and the pertinent

statutes, federal and state, which provide the basic

structure for the system. We then discuss the federal

government’s responsibility for training the National

Guard, and, in particular, the training that guardsmen

receive for civil disturbance control duty. Finally, in

connection with the Guard’s civil disturbance control

responsibilities, we explain the rules observed by the

Army and the Ohio National Guard with respect to

the use of force.

A. T H E NATION AL GUARD

The Army National Guard and Air Force National

Guard are the “Militia” referred to in Article I, Sec

tion 8, clauses 15 and 16 of the Constitution:

The Congress shall have Power * * *

To provide for calling forth the Militia to ex

ecute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insur

rections and repel Invasions;

To provide for organizing, arming, and dis

ciplining, the Militia, and for governing such

Part of them as may be employed in the Serv

ice of the United States, reserving to the States

respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and

the Authority of training the Militia according to

the discipline prescribed by Congress; * * *.

In first exercising the militia power, Congress pre

scribed only the organization and discipline of the

militia; subsequently, it also supplied arms and equip

7

ment.1 Since the beginning of this century, when the

term “ National Guard” came into use, Congress has

also provided funds for the compensation of militia

members. The basic structure of the National Guard

as it is known today was established by the National

Defense Act of 1916, 39 Stat. 166, et seq., as amended,

now 32 U.S.C. 101, et seq.

The 1916 Act embodied a fundamental decision to

use the organized State militia, rather than a standing

army or national force of volunteer reserves, as a

basic source of reserve military strength. H. Sep. No.

297, 64th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 2-9, 14 (1916). Congress

not only xirovided for the arming, organization and

discipline of the National Guard, but authorized the

use of federal funds for the compensation of its offi

1 For a comprehensive discussion of the origins of the Na

tional Guard, see Wiener, The Militia Clause of the Constitution,

54 Harv. L. Rev. 181 (1940). In the late Eighteenth century the

militia was “a home-defense force, composed of most able-bodied

men.” Wiener, supra, 54 Harv. L. Rev. at 182. Most of the nation's

military problems during the late Eighteenth and early Nine

teenth centuries were dealt with by the militia and not by a

standing army. During this time, however, the deficiencies of

the militia became notorious—for example, many militiamen

refused to fight outside their own state—and an expansion of

the regular army gradually took place. The first modern in

stitutional reforms were introduced by the Army Reorganiza

tion Act of 1901, 31 Stat. 748, which established a regular army

“suited to the requirements of the United States as a world

power” (54 Harv. L. Rev. at 193), and the Dick Act of 1903, 32

Stat. 775, which “provided for an Organized Militia, to be

known as the National Guard, which should conform to the

Regular Army organization, be equipped through federal funds,

and be trained by Regular Army instructors” (54 Harv. L. Rev.

at 195).

8

cers if members of the Guard units and their officers

met federally-prescribed standards. See, e.g., 53 Cong.

Bee. 4356.

The 1916 Act contemplated that the Rational Guard

would be both a state militia under the command

and direction of the state except when called into fed

eral service, and a reserve component of the national

armed forces which, when ordered into active federal

service, would constitute an integral part of the na

tion’s regular military force. The Act made it clear

that the states are to retain command and operational

control over the Rational Guard when it is not in ac

tive federal service, and that the state retains its tradi

tional power to use its militia “ within the jurisdiction

concerned, as its chief executive * * * considers nec

essary * * 32 TT.S.C. 109(c).

Despite the large measure of autonomy which Con

gress gave the states, the Act provided that Guard

units could qualify for federal financial support only

if they maintained “federal recognition” by partici

pating in federally-prescribed drills and training and

by passing inspections designed to assure that their

members, organizations, training, instruction and

property meet prescribed federal standards. 32 U.S.C.

105, 108, 502. The Act empowered the President to

“prescribe regulations, and issue orders, necessary to

organize, discipline, and govern the Rational Guard.”

32 U.S.C. 110.

The laws of Ohio illustrate the dual function which

the Rational Guard performs. The state recognizes

that its militia is an integral part of the nation’s

9

overall military program; state law provides that

“ [t]lie military laws of this state shall conform to all

laws and regulations of the United States affecting

the same subject and anything to the contrary shall

be void so long as the subject matter has been acted on

by the United States.” Ohio Revised Code, § 5923.28

(1971 Supp.). On the other hand, the state also pro

vides that the militia is to exercise its traditional role

as a residual state police force which can be used in

times of emergency or exceptional stress to aid in quell

ing civil disturbances. State law provides that “ [t]he

organized militia may be ordered by the governor to

aid the civil authorities to suppress or prevent riot

or insurrection * * Ohio Revised Code, § 5923.21.

See, also, Ohio Revised Code, §§ 5923.22, 5923.1 (1971

Supp.).

B. T H E HOLE OF T H E FEDERAL GOVERNMENT IN T R A IN IN G T H E ARMY

NATION AL GUARD

Article I, Section 8, cl. 16 of the Constitution gives

Congress the power to provide for “organizing, arm

ing, and disciplining, the Militia” and reserves to the

states “the Authority of training the militia according

to the discipline prescribed by Congress.” The con

gressional prescription of a uniform training regimen,

or discipline, ensures that—should the need arise—the

militia can be effectively integrated into the regular

Army. But while the Constitution contemplates that

the federal government will prescribe the training pro

gram, the state, as long as the Guard has not been

federalized, actually administers the training.

10

In prescribing the training of the national Guard,

the Army naturally is primarily concerned with insur

ing that the Guard is qualified to serve as part of the

Army if called to active federal duty. But the Army

has also promulgated detailed instructions for civil

disturbance control training.2 This training program

is for national Guardsmen as well as members of the

regular Army.

Members of the Army national Guard receive train

ing at three stages of their enlistment—an initial tour

of active duty in the Army; throughout their period

of service in their national Guard units; and at sum

mer encampments.

Initially, a person without prior military service

who enlists in the national Guard must serve on ac

tive duty with the regular Army for a minimum of

four months. 10 XT.S.C. 511(d). During this period, the

guardsman receives his Basic Combat Training

(“BCT”) and Advanced Individual Training

(“AIT”), both of which are taken with regular Army

recruits. The guardsman’s training at this stage of his

enlistment is governed by regular Army regulations

and administered by regular Army personnel.

Prior to 1971, this initial training was the same for

both regular Army and National Guard recruits. In

that year, however, the Army began to give National

Guard recruits 16 hours of additional special civil dis

turbance control training. This special training was

initiated in recognition of the fact that Guard units

2 See Army Subject Schedule 19-6, “Control of Civil Dis

turbances,” dated August 9, 1972, a copy of which has been

lodged with the Court.

11

are more likely to be called to suppress civil disturb

ances than are regular Army units.3

Individuals with prior military service may enter

the National Guard without undergoing the active

duty required of enlistees without prior service. 10

U.S.C. 510(b)(2). If such persons completed their

regular service without having received civil dis

turbance training, Army regulations require that they

receive eight hours of individual civil disturbance

training before they participate in the National

Guard’s own training program.4

Most of the training a guardsman receives after his

integration into a National Guard unit is conducted

by Guard personnel. While each unit of the National

Guard must assemble for drill and instruction at least

48 times a year (32 U.S.C. 502(a)(1)) and may not

receive credit for a drill unless “the training is of

the type prescribed by the Secretary concerned” (32

U.S.C. 502(d) (3)), the basic decisions with respect to

allocation of training times are made by the State

Adjutants General. Thus, for example, the Army

requires that whenever a National Guard unit is

assigned a new civil disturbance mission, it must use

the earliest available weekend drills to conduct civil

disturbance training; similarly, all units wdth civil

disturbance missions are required to conduct annual

3 See paragraph 3c, Appendix XXY, Aux F to “deserve En

listment Program of 1963,” a copy of which has been lodged in the

Court.

4 Paragraph 4a, Appendix XV, Aux F to “Training in Civil

Disturbance Control Operations,” a copy of which has been lodged

in the Court.

12

civil disturbance refresher training. In both eases, the

training must follow federal standards. The com

mander of the unit, however, is given discretion, with

in certain limits, to vary the hours devoted to any

particular subject (e.g., riot control formations).5

Finally, guardsmen receive training during the sum

mer encampments which all Guard units must par

ticipate in for at least 15 days each year. 32 U.S.C.

502(a)(2). Since the annual summer camp training

is devoted primarily to maintaining the Guard’s com

bat readiness for its national defense role, civil dis

turbance training is not conducted at such times unless

specifically authorized by the Continental Army

Command.6

C. EXILES PER TA IN IN G TO T H E USE OE FORCE

Closely related to the civil disturbance control train

ing which guardsmen receive are the “use of force”

rules to which they are subject when in an operational

or mobilized status. When the Guard is involved in

civil disturbance control while in federal status, the

Army’s use-of-force rules govern. More frequently,

the Guard is in state status when it is called on to

perform eivil disturbance control duties. In such cir

cumstances it is subject to the state’s use-of-force

regulations. While the National Guards of all states,

including Ohio, have now voluntarily adopted the fed

eral standards as their own, the Ohio rules at the time

5 See, e.g., paragraphs 2a(2), 3a and 3b, Appendix XV Affix F'

to “Training in Civil Disturbance Control Operations,” note 4,

supra.

6 See paragraph 3c, Appendix XV Anx F to “Training in Civil

Disturbance Control Operations,” note 4, supra.

13

of the Kent State incident (i.e., May 1970) were sub

stantially different from the federal rules and quite

different from what they are today.

1. Army Use-of-Force Rules

Since March 1968, Army rules have strictly limited

the use of force in civil disturbance control operations

to the minimum necessary to accomplish the mission.7

The current rules, which are set forth in-Appendix

A, infra, pp. 29-40, provide detailed limitations on

the use of deadly force. Such force is authorized only

where (App. A, infra, p. 31) :

(1) Lesser means have been exhausted or are

unavailable; and

(2) The risk of death or serious bodily harm

to innocent persons is not significantly increased

by its use; and

(3) The purpose of its use is one or more of

the following:

(a) Self-defense to avoid death or serious

bodily harm * * *;

(b) Prevention of a crime which involves a

substantial risk of death or serious bodily harm

(for example, setting fire to an inhabited dwell

ing or sniping), including the defense of other

persons;

(c) Prevention of the destruction of public

utilities or similar property vital to public

health or safety; or

(d) Detention or prevention of the escape

of persons who have committed or attempted

7 See Field Manual 19-15, “Civil Disturbances and Disasters,”

dated March 25, 1968, a copy of which has been lodged in the

Court.

497-1S5— 73------ 3

14

to commit one of the serious offenses referred

to in (a), (b), and (c) above.

The rules further provide with respect to the use

of live ammunition (App. A, infra, pp. 32-33) :

Task force commanders are authorized to

have live ammunition issued to personnel under

their command. Individual soldiers will be in

structed, however, that they may not load their

weapons * * * except when authorized by an

officer or, provided they are not under the di

rect control and supervision of an officer, when

the circumstances would justify their use of

deadly force * * *. Retention of control by an

officer over the loading of weapons until such

time as the need for such action is clearly

established is of critical importance in pre

venting the unjustified use of deadly force.

Whenever possible, command and control ar

rangements should be specifically designed to

facilitate such careful control of deadly

weapons.

The rules also provide several other safeguards re

lating to the use of force and the control of crowds.

See generally App. A, infra, pp. 29-40.

2. Ohio Use-of-Force Buies

The use-of-force rules of the Ohio Rational Guard

that were in effect during May 1970 differed substan

tially from those of the Army. See App. B, infra, pp.

41-45. The Ohio rules did state that only the mini

mum force necessary should be used. However, they

further provided (App. B, infra, p. 44) that “ [i]n any

instance where human life is endangered by the fore-

15

ible, violent actions of a rioter, or when rioters to

whom the Riot Act has been read cannot be dispersed

by any other reasonable means, then shooting is justi

fied” (emphasis added). Furthermore, contrary to

the Army rules, the Ohio directive specified that

guardsmen were to carry loaded rifles. See App. B,

infra, p. 43.

In December 1970, following the shootings at Kent

State, the Ohio National Guard issued a new opera

tions plan which adopted the Army use-of-force rules

verbatim.8

II. RESPONDENTS' CLAIM— THAT THE TRAINING, WEAPONS,

AND ORDERS OF THE OHIO NATIONAL GUARD DEPRIVE OR

THREATEN TO DEPRIVE THEM OF CONSTITUTIONAL

RIGHTS— IS NOT JUSTICIABLE

Respondents seek a judicial inquiry into and a ju

dicial determination of the adequacy of the current

training practices and policies of the Ohio National

Guard. For reasons which are discussed below (see

pp. 20-28, infra), we believe that respondents do not

have standing to litigate those issues. But we further

believe that the kind of judicial involvement in and

supervision of military affairs which respondents’

complaint would require is beyond the proper sphere

of judicial action.

8 See Appendix 2 to Annex C to Oplan Act, a copy of'which

has been lodged in the Court. By directive dated June 28, 1972,

a copy of which has also been lodged in the Court, the Ohio Ad

jutant General in effect incorporated all the amendments made

to the Army rules up to that date and added further protective

rules.

16

The court below construed respondents’ complaint

as alleging that the training, weapons, and orders of

the Ohio National Guard “make inevitable the use of

[unnecessary] fatal force in suppressing civilian dis

orders * * *” (italics omitted; Pet. App. 18). The court

assumed that appropriate injunctive relief could be

fashioned if respondents’ claims were upheld. But the

fashioning of any injunctive relief would require the

district court itself to determine the training, weapons,

and orders appropriate for civil disturbance control.

This is not the kind of determination that courts are

equipped to make or are expected to make under our

system of allocation of governmental powers; it is a

matter which requires the technical skills and infor

mation that the military authorities possess, and which

they alone are qualified to decide.

The extent of judicial intervention in military af

fairs which would be likely to result if this suit could

be maintained is illustrated by the relief which re

spondents request—that future use of the Ohio Na

tional Guard for the control of civil disturbances on

the Kent State campus be enjoined until the Guard

has been “ competently trained in techniques of civil

ian disorder control, * * * provided with the best

available non-lethal equipment for use in civilian dis

order control, * * * instructed not to use deadly force

except in the case of actual self-defense or upon per

sons who have actually used or threatened the use of

deadly force and * * * ordered not to carry live ammuni

tion loaded in their guns when engaged in such control of

civilian disorders * * *” (App. 11). Respondents thus

17

seek, and the court of appeals apparently has author

ized, “ a 'broad-scale investigation, conducted by [re

spondents] as private parties armed with the subpoena

power of a federal district court and the power of

cross-examination, to probe into the [National Guard’s

civil disturbance control techniques] * * * with the dis

trict court determining at the conclusion of that investi

gation the extent to which those [techniques] may or

may not be appropriate * * Laird v. Tatum, 408

U.S. 1, 14. Such judicial control of the National

Guard’s training, weapons and orders constitutes a

“forbidden judicial intrusion into the administrative

domain. ” Arrow Transportation Go. v. Southern R. Co.,

372 U.S. 658,670.

Furthermore, the broad-scale investigation required

by respondents’ complaint, as construed by the court

of appeals, lacks the specificity required for adjudica

tion. Respondents challenge not merely particular

rules or activities but the general propriety of the

Guard’s training, weapons, and orders with respect to

civil disorders. Justiciability requires “that clear con

creteness provided when a question emerges precisely

framed and necessary for decision * * United

States v. Fruehauf, 365 U.S. 146, 157. Respondents,

however, seek the kind of comprehensive review ap

propriate to a legislative committee; this is a task for

which the judiciary is ill-suited. The courts should not

be asked to function “as virtually continuing moni

tors of the wisdom and soundness of Executive ac

tion * * Laird v. Tatum, supra, 408 U.S. at 15.

18

These considerations concerning the proper alloca

tion of judicial and executive responsibilities are

especially telling in the instant case. The inquiries

in which respondents would involve the judiciary—

such as whether the Ohio Guard has been “compe

tently trained in techniques of civilian disorder con

trol” and “provided with the best available nonlethal

equipment for use in civilian disorder control”—call

for the kind of specialized knowledge and skills that

the judiciary does not possess. For example, what

standards is the district court to apply in determin

ing whether members of the Ohio National Guard

have been “competently trained?” Is the court to

attempt to evaluate the adequacy of the instruction,

the caliber of the instructors, and the sufficiency of

the examination and evaluation made upon completion

of the training? Presumably the military authorities

have selected what they consider “the best available”

equipment for use in civilian disorder control; is the

district court to make its own independent evaluation,

on the basis of possibly conflicting expert testimony,

whether there are other kinds or brands of equipment

that would be better? Is the district court’s role in

this inquiry to be the traditional one of reviewing the

propriety of administrative action—to determine

whether it is arbitrary and capricious—or is the court

expected to decide these questions de novo, as if it

were the military authorities prescribing the Guard

training? Either standard of inquiry would be inap

propriate ; the determination of the proper way in

which to prepare members of the National Guard

19

for the performance of their military duties must be

made by the military. Cf. McAbee v. Martinez, 291 F.

Supp. 77 (D. Md.). As this Court noted in Orloff v.

Willoughby, 345 U.S. 83, 93-94:

* * * [JJudges are not given the task of run

ning the Army. * * * Orderly government re

quires that the judiciary be as scrupulous not

to interfere with legitimate Army matters as

the Army must be scrupulous not to intervene

in judicial matters.

Moreover, respondents seek not only judicial con

trol of the training of the National Guard, but also

judicial prescription of the precise way in which the

Guard should operate when dealing with civilian dis

orders. Thus, respondents seek an injunction prohibit

ing the Guard from using “ deadly force except in

the case of actual self-defense or upon persons who

have actually threatened the use of deadly force.”

That kind of an injunction, however, would be singu

larly inappropriate as a device for controlling the

operations of the National Guard, and could result

in the very kind of bloodshed and loss of life that

the respondents apparently are seeking to prevent.

The determination whether to use force, in what

circumstances and in what amount, can be made only

in the light of the actual civilian disturbance as it

exists, and not in advance in a theoretical context.

The decisions with respect to the appropriate tech

niques to be employed to control civil disturbances

must be made on the spot, in the light of the actual

situation facing the troops, and with the benefit of the

accumulated experience in dealing with this sensitive

20

problem that only the military authorities, and not

the courts, can possibly possess.

The use of an injunction to control this aspect of

the National Guard’s activities would be particularly

ill-advised. Commanders at the scene of a civil dis

order might be reluctant to use their best military

judgment with respect to what is the most suitable

method of dealing with the situation if there was

lurking in the background the possibility that a court

subsequently would conclude that their actions went

beyond what the injunction permits and therefore

constituted contempt. The military authorities can

not properly perform their duties within the con

straint of a judicial order telling them how to op

erate—-an order necessarily made without knowledge

of the specific facts with which the military will be

confronted when they are called on to act. For the

Guard to carry out its responsibility for maintaining

civil order, it must retain operational flexibility. The

occasions when plans to deal with civil disturbances

must be put into effect are always full of stress and

unpredictability. The authority to improvise or re

formulate plans as necessity requires is essential in

such circumstances. Judicially imposed limitations

would seriously interfere with the Guard’s ability to

control disorders.

III. RESPONDENTS HAVE NO STANDING TO M AINTAIN THIS

SHIT

In order to have standing to challenge the pro

priety of current National Guard practices and

21

policies, respondents must demonstrate “a personal

stake in the outcome of the controversy.” Baker v.

Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 204-.9 There must be “a logical

nexus between the status asserted and the claim

sought to be adjudicated * * *” (Blast v. Cohen, 392

U.S. 83, 102), which can be established only by a show

ing of “specific present objective harm or a threat of

specific future harm.” Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1, 14.

See, also, Linda B, S. v. Bichard 1)., Ido. 71-6078,

decided March 5, 1973; Moose Lodge No. 107 v. Irvis,

407 U.S. 163, 166-167; Sierra Glut) v. Morton, 405

U.S. 727, 731-732.

Respondents attempt to meet this requirement of “a

personal stake” by alleging that as a consequence of

the Guard’s activities at Kent State during May

1970, they are presently intimidated from exercising

their “rights of lawful assembly, speech and associa

tion” (Br. 3) and are threatened with future “dep

rivations of life and liberty without due process of

law” (ibid.). But as we shall show, these putative

injuries are remote and hypothetical; “on this record

the respondents have not presented a case for resolu

tion by the courts.” Laird v. Tatum, supra, 408 U.S. at

15.

9 This requirement of “a personal stake” is not simply im

posed as a device for exercising judicial restraint. The juris

diction of Article I I I courts rests upon the existence of a

genuine case or controversy, and standing is necessary to ensure

“that concrete adverseness” (Baker v. Carr, supra, 369 U.S. at

204) which is the prerequisite of a case or controversy in the

constitutional sense. See Linda, R. S. v. Richard D., No. 71-6078,.

decided March 5,1973 (slip op., p. 3).

497- 185— 73- 4

22

A. RESPONDENTS HAVE NOT ID EN T IFIED A SU F F IC IE N T THREAT OF

SPEC IFIC FU TU RE H A R M TO JU S T IF Y IN V O K IN G T H E JU D IC IA L

PROCESS

Respondents claim (Br. 22-26) that the “rules, pro

cedures and operating methods followed by the Ohio

National Guard” (Br. 2) subject them to a continuing

threat of future deprivations of their constitutional

rights. But their claim of future harm is wholly specu

lative. Respondents base their claim upon the single

incident at Kent State in May 1970, and ignore the

substantial revisions that have since been made in

Guard policy which eliminate much of the source of

their concern.

1. The single incident at Kent State in May 1970 does

not pose a sufficient threat of repetition to warrant

judicial intervention.

Whether respondents have standing to maintain this

suit depends, in the first instance, not upon the ser

iousness but upon the likelihood of the asserted pros

pective injury. I t is the imminence and probability of

harm that provides the concreteness necessary to estab

lish a case or controversy appropriate for judicial

resolution. Of. Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497. A litigant

has no standing to complain about threatened injury

that is remote or speculative. See Ex parte Levitt, 302

U.S. 633, 634.

We are not unmindful of those decisions cited by

respondents which have indicated, following this

Court’s opinion in Hague v. G.I.O., 307 U.S. 496,

that courts may appropriately provide “ injunctive

or declaratory relief based on claims that police or

23

other agencies of state or local government were en

gaging or had engaged in deprivations of constitu

tionally secured rights” (Br. 17). See, e.g., Lewis v.

Kugler, 446 F. 2d 1343 (HA. 3) ; Schnett v. City of

Chicago, 407 F. 2d 1084 (C.A. 7) ; Gomez v. Layton,

394 F. 2d 764 (C.A. D.C.). However, as the Second Cir

cuit has pointed out, “ [t]he very statement of [the

facts] of these eases shows their inapplicability to a

situation involving a single although grave failure by

the police to discharge their responsibilities, followed

by speedy criticism and the taking of corrective

measures * * Belknap v. Leary, 427 F. 2d 496,

499 (C.A. 2).10

In Hague itself, city authorities had, over a long

period of time, directed an active and pervasive pro

gram of harassment against the plaintiffs, and had

10 Belknap was an action under 42 U.S.C. 1983 to restrain

New York City police from failing to accord anti-war pro

testers protection against physical assaults by counter-protesters

at future demonstrations. Plaintiffs pointed to one previous

demonstration where authorities were allegedly negligent in

failing to protect them from such assaults. The court con

trasted this single dereliction by police, which it concluded was

an inadequate basis to justify injunctive relief, with the facts

in cases like 0ottonreader v. Johnson, 252 F. Supp. 492 (M.D.

Ala.) and Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F. 2d 197 (C.A. 4), upon

both of which respondents rely. The court noted (427 F. 2d at

499) that in Cottonreader “the defendants, including the Mayor

and Chief of Police, over a period of months had themselves

intimidated and harassed the plaintiffs as well as permitting other

citizens to intimidate, threaten and assault them,” and that

Lankford involved “an instance of large scale police violation

of the Fourth Amendment which * * * ‘on a smaller scale has

routinely attended efforts to apprehend persons accused of seri

ous crime’ ” {ibid.) .

24

expressed their intent to continue such activities in

definitely. In the present ease, on the other hand, there

is no allegation of a continuing policy and practice of

interfering with the exercise and enjoyment of con

stitutional rights. Standing is predicated solely upon

a single, although momentous, tragic incident. But

that event, by itself, does not pose a sufficient “ threat

of specific future harm. ’ ’11

Since respondents’ claim of future injury is wholly

speculative, even as students at Kent State they have

no greater standing to challenge the propriety of cur

rent National Guard training, weapons, and orders

than do any other residents of Ohio. And mere status

as a resident does not confer standing to sue. Of.

Tileston v. Tillman, 318 IT.S. 44.12

2. Respondents have no standing for the further rea

son that the National Guard practices and policies on

which their case is based no longer exist

In Belknap v. Leary, supra, the Second Circuit, in

addition to pointing out that only a single incident of

11 Respondents’ allegation of past injury does not confer

standing here. This case does not involve an inquiry into the

adequacy of the training or the propriety of the weapons and

orders of the National Guard units involved in the shootings at

Kent State. Cf. Scheuer v. Rhodes, petition for a writ of cer

tiorari pending, No. 72-914. Respondents instead seek an in

vestigation into current practices and policies and request

prospective relief. Past injury is irrelevant to a “personal

stake” in the granting of prospective relief, in the absence of

a showing that recurrence of the injury is likely.

12 Respondents do not allege standing as taxpayers, but

since this case does not involve the spending power such an

allegation would in any event be unavailing. Flast v. Cohen,

392 U.S. 83.

25

unlawful police action had been alleged, emphasized

(427 F. 2d at 499) that corrective measures were taken

by the city shortly after the incident giving rise to the

litigation occurred. Similarly, in Laird v. Tatum,

supra, this Court noted (408 U.S. at 8) that “the

Army’s review of the needs of its domestic intelligence

activities has indeed been a continuing one and. * * *

those activities have since been significantly reduced.”

Thus in both eases the existence of recently introduced

corrective measures was a significant factor supporting

the conclusion that judicial intervention was unwar

ranted.

In this case, also, there have been significant changes

in official policies and practices (see pp. 12-15

supra), and these changes further illustrate the specu

lative nature of respondents’ allegations of future

harm. For example, respondents assert (Br. 4):

The conditions alleged to be casually related to

the deprivations include failure adequately to

provide Ohio National Guard troops with spe

cialized civil disorder training or with adequate

equipment to respond to civilian disorders with

non-deadly force, causing troops to carry live

bullets in their guns and failing to properly in

struct troops as to the legal limits on their use

of deadly force.

According to respondents (Br. 2-3), because there

has been “a continuation of the same rules, proce

dures and operating methods followed by the Ohio

National Guard, [there is] * * * a substantial threat

of repetition of similar acts * * * [in the future].” Re

spondents, however, ignore the substantial changes

26

that have been made in the policies and practices that

they condemn.

As indicated above (p. 10, supra), mandatory “spe

cialized civil disorder training” has since 1971 been

required for all new National Guard enlistees; the

training is given by regular Army personnel while

the guardsman is serving his initial tour of active

duty. This training includes separate instruction in

such subjects as “stress training,” “campus and open

area operation,” “riot control agents and munitions,”

and “individual responsibilities and standards of con

duct.” 13 After his initial training, the guardsman re

ceives regular refresher courses in civilian disorder

training. See pp. 11-12, supra.

Respondents have stressed the Ohio National

Guard’s policies with respect to the use of force. But

this is the area where the most dramatic changes in

state policy have occurred. At the time of the Kent

State shootings, the Ohio National Guard’s operations

plan provided that “when rioters to whom the Riot

Act has been read cannot be dispersed by any other rea

sonable means, then shooting is justified,” and that dur

ing riot control duty “ [rjifles will be carried with a

round in the chamber in a safe position.” See p. 15,

supra. Neither of these directives is in effect today. As

we have shown (p. 15, supra), Ohio has adopted ver

batim the regular Army’s use-of-force rules, which

prohibit the carrying of loaded weapons and carefully

delineate and restrict the situations where use of dead

ly force may be employed.

13 See Army Subject Schedule 19-6, note 2, supra.

27

In view of these changes in state practice and policy,

there is no basis for any substantial claim that the

conditions that gave rise to the Kent State shootings

are likely to be repeated. For this reason respondents’

claim lacks the adverseness and immediacy that is

necessary before courts may properly act.

B . r e s p o n d e n t s ’ SUGGESTION o r a “ c h i l l i n g ” e f f e c t o n t h e ir

FIR ST A M EN D M EN T RIGHTS IS IN SU BSTA N TIA L

Respondents suggest that they are presently suffer

ing injury because the practices and policies of the

Ohio National Guard intimidate them in the exercise

of their First Amendment rights.14 This ‘‘chilling

effect argument typically is made where, as in Laird

v. Tatum, supra, the executive activity allegedly giving

rise to the putative chill is ongoing and not merely

potential. Here, of course, there is no ongoing event

or program which respondents will inevitably con

front; they allege merely that such an event {i.e., the

recalling of the National Guard to the Kent State

campus) may occur at some unspecified time in the

future. Thus any “chilling” effect stems only from

present fears of uncertain harm at some indefinite time

in the future. Since, as we have shown, respondents can

not show a threat of specific future harm here, a fortiori

any claim of present First Amendment deprivation must

fall as well.

This case has strong overtones because it arises out

of a great national tragedy. I t involves, however, an

area which is particularly inappropriate for judicial

14 While respondents do not here expressly assert a “chilling”

effect, that claim appears to be implicit in their contentions

when viewed as a whole. See, e.g., App. 6; Br. 2-3.

28

supervision and control: the operations of the mili

tary. I t is our position that courts should not inter

vene in this sensitive area unless the plaintiffs have

clearly shown that they are likely to undergo specific

injury from the practices they challenge. Cf Laird v.

Tatum, supra. The respondents have not made such a

showing.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the court

of appeals should be reversed, with directions that the

complaint be dismissed.

Respectfully submitted.

E rwin R . Griswold,

Solicitor General,

H arlington W ood, Jr.,

Assistant Attorney General.

R obert E . K opp,

J oseph B . S cott,

Attorney

R obert W . B erry,

General Counsel.

R . K enly W ebster,

Deputy General Counsel.

W illiam C. W ooldridge,

J ames S. Carey,

Attorneys,

Department of the Army.

M arch 1973.

APPENDIX A

Paragraphs 4-11, 4—12, and 5-9 of Army Field

Manual 19-15, “ Civil Disturbances,” dated March 22,

1972, provide:

4-11. General.

a. Operations by Federal forces will not be author

ized until the President is advised by the highest offi

cials of the State that the situation cannot be con

trolled with the non-Federal resources available. The

task force commander’s mission is to help restore law

and order and to help maintain it until such time as

State and local forces can control the situation with

out Federal assistance. In performing this mission, the

task force commander may find it necessary to partici

pate actively not only in quelling the disturbance but

also in helping to detain those responsible for it. Task

force commanders are authorized and directed to pro

vide such active participation, subject to the restraints

on the use of force set forth herein.

1). The primary rule which governs the actions of

Federal forces in assisting State and local authorities

to restore law and order is that a task force com

mander must at all. times use only the minimum force

required to accomplish his mission. This paramount

principle should control both the selection of appro

priate operational techniques and tactics and the

choice of options for arming the troops (para 5-9).

Pursuant to this principle, the use of deadly force;

i.e., live ammunition or any other type of physical

force likely to cause death or serious bodily harm, is

authorized only under extreme circumstances where

(m

30

certain specific criteria are met (para 4-126). To em

phasize limitations on use of firepower and to restrict

automatic fire, commanders will insure that rifles with

only a safe or semiautomatic selection capability, or

rifles modified to have only a safe or semiautomatic

selection capability, will be used as the basic weapon

for troops in a civil disturbance area.

c. All personnel, prior to participation in civil dis

turbance operations, will be briefed as to—

(1) The specific mission of the unit.

(2) Rules governing the application of force as they

apply to the specific situation.

(3) A psychological orientation on the local situa

tion, specifically addressing types of abuse which mili

tary personnel may be expected to receive and the

proper response to these types of abuse.

4-12. Use of Noncleadly and Deadly Force.

a. Task force commanders are authorized to use

nondeadly force to control the disturbance, to prevent

crimes, and to apprehend or detain persons who have

committed crimes; but the degree of force used must

be no greater than that reasonably necessary under

the circumstances. The use of deadly force, however,

in effect invokes the power of summary execution

and can therefore be justified only by extreme neces

sity. Accordingly, its use is not authorized for the

purpose of preventing activities which do not pose a

significant risk of death or serious bodily harm (e.g.,

curfew violations or looting). I f a mission cannot

be accomplished 'without the use of deadly force, but

deadly force is not permitted under the guidelines

authorizing its use, accomplishment of the mission

must be delayed until sufficient nondeadly force can

be brought to bear. The commander should report

the situation and seek instructions from higher au

31

thority. All the requirements of b, below, must be

met in every case in which deadly force is employed.

b. The use of deadly force is authorized only where

all three of the following circumstances are present:

(1) Lesser means have been exhausted or are un

available; and

(2) The risk of death or serious bodily harm to

innocent persons is not significantly increased by its

use; and

(3) The purpose of its use is one or more of the

following:

(a) Self-defense to avoid death or serious bodily

harm (c, below);

(&) Prevention of a crime which involves a sub

stantial risk of death or serious bodily harm (for ex

ample, setting fire to an inhabited dwelling or snip

ing) , including the defense of other persons;

(c) Prevention of the destruction of public utilities

or similar property vital to public health or safety; or

(d) Detention or prevention of the escape of per

sons who have committed or attempted to commit

one of the serious offenses referred to in (a), (b),

and (c) above.

c. Every soldier has the right under the law to

use reasonably necessary force to defend himself

against violent and dangerous personal attack. The

limitations described in this paragraph are not in

tended to infringe this right but to prevent the unau

thorized or indiscriminate firing of weapons and

the unauthorized or indiscriminate use of other types

of deadly force.

d. In addition, the following policies regarding the

use of deadly force will be observed:

(1) When firing ammunition, the marksman should,

if possible, aim to wound rather than to kill.

32

(2) When possible, the use of deadly force should

be preceded by a clear warning to the individual or

group that use of such force is contemplated or immi

nent.

(3) Warning shots are not to be employed. Such

firing constitutes a hazard to innocent persons and

can create the mistaken impression on the part of citi

zens or fellow law enforcement personnel that sniping

is widespread.

(4) Even when its use is authorized pursuant to

Ik above, deadly force must be employed only with

great selectivity and precision against the particular

threat which justifies its use. For example, the receipt

of sniper fire—however deadly—from an unknown

location can never justify “returning the fire” against

any or all persons who may be visible on the street

or in nearby buildings. Such an indiscriminate re

sponse is far too likely to result in casualties among

innocent bystanders or fellow law enforcement per

sonnel; the appropriate response is to take cover and

attempt to locate the source of the fire so that the

threat can be neutralized in accordance with e, below.

e. Task force commanders are authorized to have

live ammunition issued to personnel under their com

mand. Individual soldiers will be instructed, however,

that they may not load their weapons (place a round

in the chamber) except when authorized by an officer

or, provided they are not under the direct control and

supervision of an officer, when the circumstances

would justify their use of deadly force pursuant to b,

above. Retention of control by an officer over the load

ing of weapons until such time as the need for such

action is clearly established is of critical importance in

preventing the unjustified use of deadly force. When

ever possible, command and control arrangements

33

should be specifically designed to facilitate such care

ful control of deadly weapons.

/. The presence of loaded weapons in tense situa

tions may invite the application of deadly force in re

sponse to provocations which while subject to censure,

are not sufficient to justify its use; and it increases the

hazard that the improper discharge of a weapon by

one or more individuals will lead others to a reflex

response on the mistaken assumption that an order to

fire has been given. Officers should be clearly in

structed, therefore, that they have a personal obliga

tion to withhold permission for loading until circum

stances indicate a high probability that deadly force

will be imminently necessary and justified pursuant to

the criteria set forth in b, above. Strong command

supervision must be exercised to assure that the load

ing of weapons is not authorized in a routine, prema

ture, or blanket manner.

g. Task force commanders should at all times exer

cise positive control over the use of weapons. The in

dividual soldier will be instructed that he may not

fire his weapon except when authorized by an officer,

or provided he is not under the direct control and

supervision of an officer, when the circumstances,

would justify his use of deadly force pursuant to b,

above. He must not only be thoroughly acquainted

with the prerequisites for the use of deadly force,

therefore, but he must also realize that whenever his

unit is operating under the immediate command and

control of an officer, that commander will determine

whether the firing of live ammunition is necessary.

h. Task force commanders may at their discretion

delegate the authority to authorize the use of deadly

force, provided that such delegation is not inconsistent

with this paragraph and that the person to whom such

497—1Su— 73------- 2

34

delegation is made understands the constraints upon

the use of deadly force set forth in b, above.

* * * * *

5-9. Techniques for Crowd Control.

There are numerous techniques designed to provide

the commander with flexibility of action in accom

plishing crowd control. He must select a combination

of techniques which will produce the desired results

within the framework of the selected crowd control

option. The most common techniques appropriate for

military usage are discussed below:

a. Observation. This consists of the deployment of

individuals or teams to the periphery of a crowd for

the purpose of monitoring its activity. I t includes

gathering information on crowd size, location, mood,

and reporting on the developing situation. This tech

nique includes posting individuals on strategic roof

tops and other high terrain overlooking the crowd.

This latter measure provides additional security to con

trol force personnel should they be committed to other

crowd control operations. Such a team may be com

posed of an expert marksman, a radio operator, and

an observer equipped with binoculars. Care must be

taken to assure that committed control forces are

aware of the locations of such teams to preclude their

being mistaken for sniper elements.

b. Communication of Interest and Intent. In certain

situations effective communication with crowd and

mob leaders and participants may enable the com

mander to control the situation without resort to more

severe actions. When planned and organized demon

strations, marches or rallies within the disturbed area

are announced, the control force commander in co

ordination with local authorities should meet with

organizers of the activity in order to communicate the

35

interest of the control forces. The following matters,

as appropriate, should be discussed:

(1) Parade or demonstration permits.

(2) Location of demonstration and routes of march.

(3) Time limits for the activity.

(4) Provision of marshals by activity organizers.

(5) Prevention of violence.

(6) Safety of all concerned.

The task force commander and local authorities

should also communicate to the activity organizers

their intent to cope with violence, unlawful actions

and violations of restrictions imposed on the activity.

I t is intended that, by this communication between

activity organizers and control force personnel, the

demonstration, rally or parade will occur without in

cident through the mutual cooperation of all con

cerned. The intentions of control forces will not be

effective if delivered as an ultimatum. A limited, be

grudging dialogue with activity organizers reduces the

opportunity for authorities to learn the plans of the

demonstrators. I t must be remembered that, if this

communication is not effected, the activity organizers

might well hold the demonstration in defiance of local

authorities, thereby creating a potential for violence

that might not have existed if this technique had been

employed.

c. Selection of Force Options.

(1) The commitment of Federal military forces

must be viewed as a drastic last resort. Their role,

therefore, should never be greater than is absolutely

necessary under the particular circumstances which

prevail. This does not mean, however, that the number

of troops employed should be minimized. To the con

trary, the degree of force required to control a dis

turbance is frequently inversely proportionate to the

number of available personnel. Doubts concerning the

36

number of troops required, therefore, should normally

be resolved in favor of large numbers since the pres

ence of such large numbers may prevent the develop

ment of situations in which the use of deadly force is

necessary. A large reserve of troops should be main

tained during civil disturbance operations. The knowl

edge that a large reserve force is available builds mo

rale among military and law enforcement personnel and

contributes toward preventing overreaction to pro

vocative acts by disorderly persons.

(2) In selecting an operational approach to a civil

disturbance situation, the commander and his staff

must adhere scrupulously to the “minimum necessary

force” principle ; for example, riot control formations

or riot control agents should not be used if saturation

of the area with manpower would suffice.

(3) Every effort should be made to avoid appearing

as an alien invading force and to present the image

of a restrained and well-disciplined force whose sole

purpose is to assist in restoration of law and order

with a minimum loss of life and property and due

respect for those citizens whose involvement may be

purely accidental. Further, while riot control person

nel should be visible, tactics or force concentrations

which might tend to excite rather than to calm should

l)e avoided where possible.

(4) The measures described in (a) through (g),

below, may be applied in any order as deemed ap

propriate by the responsible commander so long as

their application is consonant with paragraph 4-12,

and otherwise in keeping with the situation as it exists.

(a) Proclamation. A public proclamation is con

sidered an excellent medium to make known to a crowd

the intentions of the control force commander. In

some instances, such a proclamation makes further

action unnecessary. A proclamation puts the popula

37

tion on. notice that the situation demands extraordi

nary military measures, prepares the people to accept

military presence, tends to inspire respect from law

less elements and supports law-abiding elements, gives

psychological aid to the military forces attempting to

restore order, and indicates to all concerned the

gravity with which the situation is viewed.

(&) Show of force. A show of force is effective in

various situations in civil disturbance control opera

tions. When a crowd has assembled in an area, march

ing a well-equipped, highly-disciplined control force

into view may he all the force that is needed to per

suade them to disperse and retire peaceably to their

homes. When persons are scattered throughout the

disturbance area in small groups, a show of force may

take the form of motor marches of troops throughout

the area, saturation patrolling, and the manning of

static posts, or similar measures.

(c) Employment of riot control formations. Riot

control formations are used to disperse massed mobs

which do not react to orders of the control force

instructing them to disperse and retire peaceably to

their homes. The employment of such formations is

part of the show of force and has a strong psycho

logical effect on any crowd. While the use of fixed

bayonets can add considerably to this effect, the dan

ger of intentional or accidental injury to nonviolent

participants or fellow law enforcement personnel

precludes such use in situations where troops are in

contact with a nonviolent crowd.

(d) Employment of water. Water from a firehose

may be effective in moving small groups on a narrow

front such as a street or in defending a barricade or

roadblock. Personnel applying water should be pro

tected by riflemen and in some instances by shields.

38

In tlie use of water, the factors discussed below should

be considered.

1. Water may be employed as a flat trajectory

weapon utilizing pressure, or as a high trajectory

weapon employing water as rainfall. The latter is

highly effective during cold weather.

2. The use of a large water tank (750 to 1,000 gal

lons) and a powerful water pump mounted on a truck

with a high pressure hose and nozzle capable of

searching and traversing will enable troops to employ

water as they advance. By having at least two such

water trucks, one can be held in reserve for use when

required.

5. In using water, as with other measures of force,

certain restraints must be applied. Using water on

innocent bystanders such as women and children

should be avoided; avenues of escape must be pro

vided; and the more severe use, flat trajectory appli

cation, should be used only when necessary.

4. Since the fire departments normally are asso

ciated with lifesaving practices rather than main

tenance of law and order, consideration should be

given to maintaining this image of the fire depart

ments through the use of other than fire department

equipment when using water for riot control and

crowd dispersal.

(e) Employment of riot control agents. Riot con

trol agents are extremely useful in civil disturbance

control operations because they offer a humane and

effective method of reducing resistance and lessen

the requirements for the application of more severe

measures of force. Task force commanders are au

thorized to delegate the authority to use riot control

agents and other forms of nondeadly force at their

discretion.

39

(/) Fire by selected marksmen. Fire by selected

marksmen may be necessary under certain circum

stances. Marksmen should be preselected and desig

nated in each squad. Selected marksmen should be

specifically trained and thoroughly instructed. They

may be placed on vehicles, in buildings, or elsewhere

as required.

(g) Full firepower. The most severe measure of

force that can be applied by troops is that of available

unit firepower with the intent of producing exten

sive casualties. This extreme measure would be used

as a last resort only after all other measures have

failed or obviously would be impractical, and the

consequence of failure to completey subdue the riot

would be imminent overthrow of the government, con

tinued mass casualties, or similar grievous conditions.

I t has never been used by Federal troops in this cen

tury. See primary rule for use of force and restric

tion on use of automatic fire in paragraph 4-11&.

. (5) The normal reflex action of the well-trained

combat soldier to sniper fire is to respond with an

overwhelming mass of fire power. In a civil dis

turbance situation, this tactic endangers innocent

people more than snipers. The preferred tactic is to

enter the building from which the fire originates.

Darkening the street in order to gain protection from

sniper fire is counterproductive. The following gen

eral approach should be emphasized in dealing with

snipers:

(a) Surround the building in which the sniper is

concealed and gain access, using armored vehicles if

necessary and available.

(&) Illuminate the area during darkness.

(c) Employ agent OS initially, if feasible, rather

than small arms fire. If CS is not successful, then

use well-aimed fire by expert marksmen. The number

40

of rounds should be kept to a minimum to reduce the

hazard to innocent persons.

(6) Consistent with the controlling principle that

he must use only the minimum force necessary to ac

complish his mission, the commander may select any

one of the following options for arming his troops:

Bayonet Ammunition

scabbard Bayonet magazine clip Chamber

A t sling

A t port.

At port.

At port.

At port.

1 See (4)(c) above.

2 See paragraph 4—12f and g.

Rifles, if capable of automatic fire, must be modified to prevent automatic operation.

Troops may be armed with riot baton in lieu of rifles.

While each of the above options represents an esca

lation in the level of force, they are not sequential in

the sense that a commander must initially select the

first option, or proceed from one to another in any

particular order. So long as the option selected is

appropriate considering the existing threat, the mini-

ramn necessary force principle is not violated.

On belt................ In scabbard_______ In pouch or be lt... Empty.

On belt--------------- In scabbard........ In pouch or be lt... Empty.

On belt--------------- Fixed i ---------------- In pouch or be lt... Empty.

On belt............... Fixed i ---------------- In weapon1 2_ Empty.

On belt--------------- Fixed i ---------------- In weapon2.Round Chambered.

A P P E N D IX B

As of May 1970, Ohio use-of-force rules, Annex P to

OPLAN 2, provided:

1. Purpose: To provide commanders with informa

tion which must be disseminated to National Guard

troops engaged in civil disturbances immediately prior

to their employment. The information contained in

paragraph 4 through 8 of this Annex will be read ver

batim to troops by an officer of the unit.

2. Situation Briefing: In each instance when Na

tional Guard troops are to be employed, the com

mander will advise all troops of the following:

a. General situation.

b. Units to be employed and the command struc

ture.

c. Passes, badges or other identification means to

be honored permitting non-military personnel in the

area.

d. Officers and key NCO’s will maintain a record

(by journal, log or diary) of orders or directives re

ceived and issued, resulting actions and any unusual

incidents. Entries should include time, date and names.

3. Mission: The commander will state the mission of

the organization and the portion for which his unit is

responsible or the manner in which the company will

be employed in carrying out the overall mission.

4. Individual Responsibility: As a member of this

unit and the Ohio National Guard, you have a most

serious and demanding individual responsibility. You

are about to serve on one of the most difficult and un

pleasant tasks that a soldier may be assigned. lie-

(41)

42

gardless of the actions and taunts of the rioters, you

must remain the well-disciplined soldier. In short, you

must look like a soldier, act like a soldier and remain

fair and impartial under all circumstances.

5. Relationship With Civil Population: Our purpose

is to restore and preserve peace among fellow citizens

most of whom are friendly, but who will tolerate mili

tary control only to the extent necessary as the result

of this emergency. When you display fairness and im

partiality, scrupulously protect life and property, and

exercise soldierly restraint under all conditions, you

merit the respect and secure the cooperation of the

civilian population. The temptation to use high handed

methods may be great, but you must remain calm and