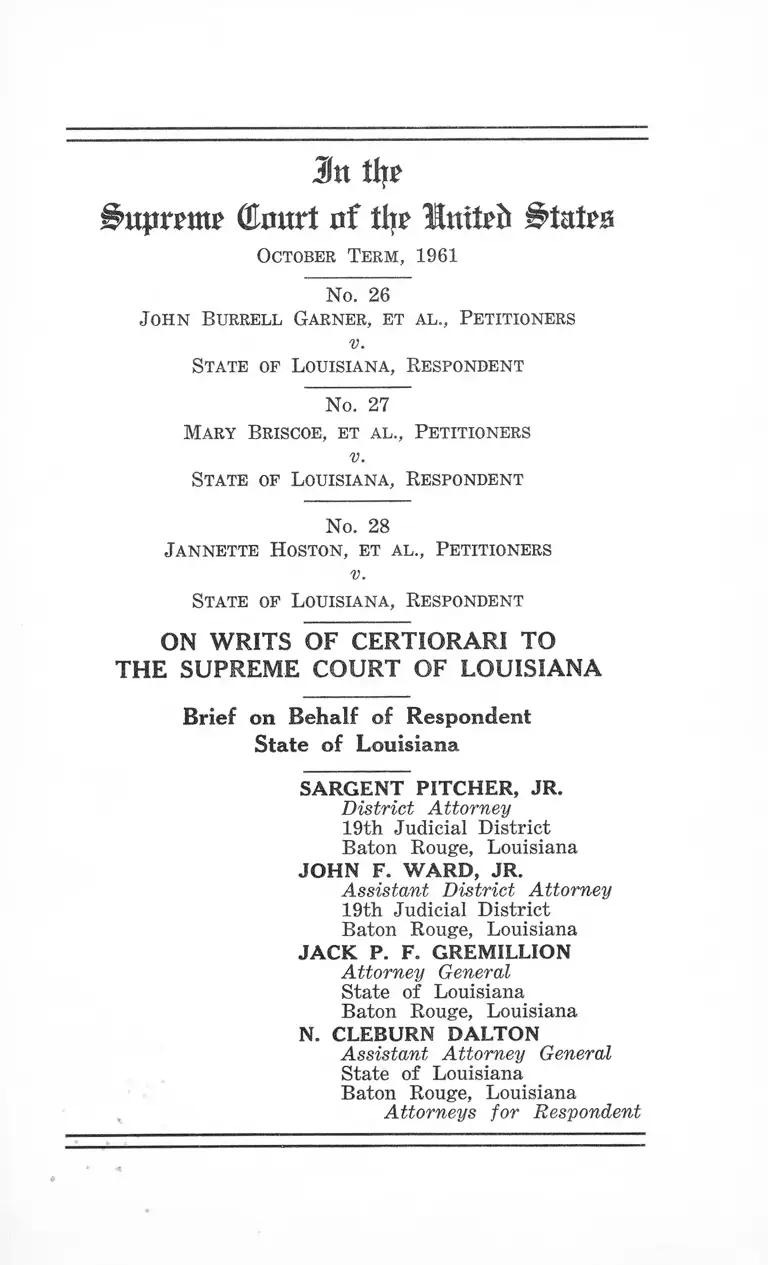

Garner v. Louisiana Brief on Behalf of Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Garner v. Louisiana Brief on Behalf of Respondent, 1961. cfafe9c7-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b9b7d0af-8947-4029-a375-3b6b24249ca6/garner-v-louisiana-brief-on-behalf-of-respondent. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Jilt tlu>

gutprem? ( to r t o f Hip Im tp fc States

Octobee Term, 1961

No. 26

J ohn Burrell Garner, et al., Petitioners

v.

State of Louisiana, Respondent

No. 27

Mary Briscoe, et al., Petitioners

v.

State of Louisiana, Respondent

No. 28

J annette Hoston, et al., Petitioners

v.

State of Louisiana, Respondent

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO

THE SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA

Brief on B ehalf of R espondent

State of Louisiana

SARGENT PITCHER, JR.

District Attorney

19th Judicial District

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

JOHN F. WARD, JR.

Assistant District Attorney

19th Judicial District

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

JACK P. F. GREMILLION

Attorney General

State of Louisiana

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

N. CLEBURN DALTON

Assistant Attorney General

State of Louisiana

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Attorneys for Respondent

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE........................... 1

ARGUMENT............................................................ 8

IN D E X P a g e

I. There was and is evidence of conduct which

would foreseeably and unreasonably dis

turb or alarm the public and this Honor

able Court should not substitute its judg

ment for that of the jury, or Trial Court,

as to whether such evidence was sufficient

to return a verdict of guilty rather than

not guilty ................................................ ..... 8

II. The statute under which petitioners were

convicted is almost identical to state stat

utes and municipal ordinances which have

been sustained throughout the nation and

as applied to these facts and circumstances

is not so vague, indefinite and uncertain as

to offend the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment............................... 40

III. These arrests and convictions do not con

stitute “state action” so as to bring them

with the prohibition of the Fourteenth

Amendment against racially discriminatory

administration of state laws..........................47

IV. The decision below does not deprive de

fendants herein of the freedom of speech

or of expression contemplated and pro

tected by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United

States ............................................................ 53

V. The facts and circumstances of the Briscoe

case do not bring it within the prohibition

of the Interstate Commerce Act.......... 55

CONCLUSION ........................................................ 63

11

TABLE OF CASES

Armstrong v. City of Tallahassee,

__ .______U.S._............__ .............................. 41

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454......... ............... 57

Burton v.l Wilmington Parking Authority, 365

U.S. 715 .,.......................................................... 50

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3.............................. 48

Davis v. Burgess, 20 nw 540, 52 Am. St. Rep.

828 ........................................................... 42

Drews et al v. State of Maryland, 167 Atlantic

2nd 341 ..................................................... 47

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336, U.S. 77, 93 L.Ed. 513,

10 ALR 2nd 608.............................................. 54

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501.................... 51, 61

Nash v. United States, 229 U.S. 373, 33 Sup. Ct.

780, 57 L.Ed. 1232.......................................... 46

Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Utility Com

mission, 301 U.S. 292...................................... 37

People v. Arko, 199 N.Y.S. 402.............................. 47

People v. Calpern, 181 ne 572................................ 47

People v. Piener, 300 N.Y. 391, 91 ne 2nd 316,

340 U.S. 315............................................. 43, 54

People v. Nixon, 161 NE 463.... ............... .............. 46

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537.......................... 50

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47, 63 L.Ed.

470, 39 Sup. Ct. 247...................................... 54

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1.......................... 48, 58

Slack v. Atlantic White Tower System, 181 Fed.

Supp. 124 ........................................................ 49

P a g e

Ill

P a g e

State v. Bessa et al, 115 La. 259, 38 So. 985....... 38

State v. Cooper, 285 NW 903, 122 ALR 727......... 42

Steel et al v. City of Tallahassee,

_________U.S.................................................... 41

Sunday Lake Iron Co. v. Wakefield, 247 U.S. 350-.. 50

Williams, v. Howard Johnson Restaurant, 268

Fed. 2nd 845.................................................... 49

United States v. Shaugnessy, 234 Fed. 2nd 715..... 37

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356....................... 50

STATUTES

Constitution of the United States, Article 4, Sec

tion 2 ............................. 53

LRS 14:103 .............................................................. 40

LRS 15:422 ...................... 38

49 USCA 316 (d) .................................................. 55

OTHER AUTHORITIES

8 Am. Jur. 834, sec. 4........................................ 45

5 Words and Phrases 767...................................... 42

Daniel H. Pollitt, Dime Store Demonstration;

Events and Legal Problems of First Sixty

Days; Duke Law Journal, No. 3, Vol. I960.. 12

Reporter Magazine, Volume 24, No. 1, January 5,

1961 issue, Page 20, The Strategy of a Sit-in

by C. Eric Lincoln.......................................... 20

Baton Rouge Morning Advocate, Vo. 35, No. 270,

271, 272, 273 and 274, March 27, 28, 29, 30

and 31, 1960 .......................................... ....... 29

Baton Rouge State Times, Vol. 118, No. 75, 76 and

77, March 28, 29 and 30, 1960....................... 30

Jtt t!|p

(Eourt of t t y ZHmtpb Blates

October Term, 1961

No. 26

J ohn Burrell Garner, et al., Petitioners

v.

State of Louisiana, Respondent

No. 27

Mary Briscoe, et al., Petitioners

v.

State of Louisiana, Respondent

No. 28

J annette Hoston, et al., Petitioners

v.

State of Louisiana, Respondent

ON W R ITS O F C ER TIO R A R I TO

TH E SU PREM E C O U RT OF LO U ISIA N A

B rief on B ehalf of R espondent

S tate of Louisiana

STA TEM EN T OF T H E CASE

On March 30, 1960, these defendants and/or

others similarly situated picketed several business

establishments in Baton Rouge in protesting the

segregation customs of the owners of those stores.

Thereafter, on that same day, these defendants

and/or others similarly situated marched, in a crowd,

2

down the main street of Baton Rouge in a “march on

the State Capitol” for the sole purpose of engaging

in a demonstration protesting the segregration cus

toms of the people of the State of Louisiana. These

demonstrations, although protected by the police de

partment of the City of Baton Rouge, were witnessed

by a great number of citizens of the City of

Baton Rouge. Tension between the two races was

high.

In the few weeks, and months, immediately pre

ceding March 28, and March 29, 1960, members of the

Negro race in other cities throughout the south had

engaged in “sit-in demonstrations”. In almost every

instance of the staging of a militant “sit-in demon

stration” violence had occurred with resulting fist

fights between members of the two races. Every

citizen of Baton Rouge, including these defendants,

were aware of these “sit-ins” and the violence which

they had caused.

Every responsible citizen of the City of Baton

Rouge was concerned over the possibility of violence,

blood shed, and mob violence facing our normally law

abiding and peaceful community.

On the evening of March 29, 1960, when it was

first learned that the “march on the capitol” demon

stration was to take place the next morning, respon

sible public officials advised law enforcement officers

not to interfere with these people if they commenced

a demonstration on the public streets of the City of

Baton Rouge either by picketing business establish

3

ments or by marching on the capitol and whether

carrying signs or not, as long as they did not block

traffic or prevent the normal use of the streets by

other persons also entitled to their use. They were

further instructed to not let any other person inter

fere with these demonstrators. Consequently, on

March 30, 1980, the demonstrators picketed and dem

onstrated the entire length of the main business

street of the City of Baton Rouge, ending their demon

stration in a mass meeting on the steps of the State

Capitol, with their right to lawfully demonstrate in this

manner at all times protected by local law enforcement

officials.

But, was this lawful manner of demonstrating

and expressing themselves sufficient?

No, the right to freely express themselves in a

place where they had a right to do so was not suf

ficient for these defendants. On March 28 and 29,

1960, these defendants had entered the respective pri

vate business establishments herein involved to force

their demonstrations on private individuals on their

own private property. (R. Hoston 7; R. Garner 6; R.

Briscoe 8)

In each of these cases, the defendants were told

in clear unmistakeable language, which could have no

other meaning under the circumstances, to cease and

desist from this unlawful activity, that is, engaging

in an “activity . . . to protest segregation” and,

“in protest of the segregation laws of the State of

Louisiana, . . . ‘sit-in’ a cafe counter seat . . . ” (R.

4

Hoston 7; R. Garner 6; R. Briscoe 8) These defend

ants were all told, in language unmistakably clear

under the circumstances, that they would not be

served food or drink at the counter at which they'

were seated but that they would be served at another

counter designated by the owner. In other words, they

were told in clear unmistakeable language that if

they were in the store for normal business purposes

they could carry out those purposes by going to the

counter pointed out to them by the manager or wait

ress involved in each particular instance, but that they

would not be served while engaging in such demon

stration in the particular area of the store at which

they were. They refused to leave the area at which

they would not be served and refused to go to the

area pointed out to them by the manager or employee

who had full legal authority to require them to go to

that particular area of the store.

If we examine pages 29 and 30 of the record in

the Hoston case, we find the manager of the store

testifying that “something unusual happened on March

28” ; that he told his waitress to “offer service at the

counter across the aisle” ; that they were “seated at

the counter reserved for white people” ; that they

were not served there and that they were “advised

that we would serve them over there” (other counter);

that they did not go over there but “continued to

sit” ; that he went to the telephone and called the

police department because “I feared that some dis

turbance might occur” . . . because it isn’t customary

for the two races to sit together and eat together

5

. . . at Kress’ . . . that this was the “custom of the

store” and that that custom was prevailing when he

got there a year and a half before. And on page 36 of

the record you have the law enforcement officers

asking them, not once, but twice, to move on, and

their refusal to do so, before they were arrested.

In the Garner case, you have the owner of Sit-

man’s Drug Store, Mr. Willis, testifying that he was

the sole owner of Sitman’s Drug Store and the sole

owner of Sitman’s Restaurant and Cafe, two separate

establishments; that although he served both Negroes

and Whites in his drug store, he served only Whites

in the cafe as a matter of personal policy and choice

to him; that this had always been his policy and

choice; that these defendants entered the cafe and

seated themselves at the counter and were told by him

that they would not be served; but the defendants

remained seated; the law enforcement officer asked

them to leave and only after they again refused to

leave were they arrested. That these defendants knew

of the policy of this private businessman on his own

private property is made clear by his answer to the

question propounded by counsel for defendant on page

32 of the record:

Q. For what reason did you refuse to serve these

defendants?

A. As a matter of policy I have never invited

colored trade, Negro trade in the restaurant,

as a matter of policy. I don’t have the facil

ities. I have facilities for only one race, the

White race, (emphasis supplied)

6

In the Briscoe case, on pages 30 and 31 of the

record, the waitress, Miss Fletcher, testified that

these defendants came in and sat down at the counter

and that she told them they would have to go to the

other side to be served. She testified further on page

31 that “they came here and said they wanted some

thing and I told them that they would have to go to

the other side to be served, and they just kept sitting

there and so we called the police and told them to come

get them.” She also testified that the police said that

“they said they would give them a chance to get up

and go or either they would have to go to jail” she

also testified as follows:

Q, And you told them you couldn’t serve them

and asked them to move, is that correct?

A. Yes sir.

Q. And when they refused to move you called the

officers?

A. Yes sir.

She also testified when questioned by the Court as

follows:

Q. As I recall your direct testimony you stated,

and if I am not correct, correct me, that

after they ordered the food you told them that

you couldn’t serve them, that they had to go

over to the other side reserved for colored

people, is that right?

A. Yes sir, that’s right.

Q. Did they go over there?

A. No sir.

7

Q. Did they refuse to go?

A. Yes sir, they just sat there . . .

Q. Was there a place reserved for colored people

in this same building?

A. Yes sir . . .

Q. Was it adequate to serve these people, was it

large enough to serve these people?

A. Yes sir.

And again when the police officer was called he

testified as follows, as shown at page 35 of the

Briscoe record:

Q. Anyway what, if anything, did you do?

A. Well, Inspector Bauer talked to one of the

group.

Q. Did you hear what was said?

A. No. And then he talked to them the second

time and then he told them that they were

under arrest . . .

Q. Did you ask them to move?

A. We did.

Q. You gave them an opportunity to get up and

leave?

A. That’s right.

Q. And did they?

A. No.

Q. Were they all together?

A. That’s right.

And again on page 37 and 38 of the record the

officer testified as follows:

8

Q. “But what I want to clear up, I think it is

fairly clear but I want to go over it again,

you requested these defendants to leave the

counter or the stools that they were sitting

on before you arrested them?

A. That’s right sir.

Q. And they refused to leave?

A. That’s right.

Q. And that’s when you made the arrest?

A. That’s right.

These defendants were then ultimately found

guilty as charged by the Court and ultimately arrived

before this Court on Writs of Certiorari.

ARGUMENT

I.

There was and is evidence of conduct which would

foreseeably and unreasonably disturb or alarm the

public and this Honorable Court should not substitute

its judgment for that of the jury, or Trial Court, as

to whether such evidence was sufficient to return a

verdict of guilty rather than not guilty.

In our Brief in Opposition to the Application for

Writs of Certiorari which was previously filed, we

discussed the various legal questions and defenses

raised by these defendants from the standpoint of

the applicable case law. In the interest of space and

time we would here re-adopt by reference each and

9

every argument submitted in our Brief in Opposition.

In addition, the concluding portion of this brief will

discuss, from the standpoint of applicable case law,

the additional points and re-worded arguments sub

mitted in defendants’ brief and the various amicus

curiae briefs filed in their behalf by the Committee

on the Bill of Rights of the Association of the Bar of

the City of New York and by the United States Gov

ernment.

At this point, respondent would attempt to put

these cases in their proper perspective from a fac

tual point of view. By argument and language, coun

sel for defendants have attempted to turn this

case into a great segregation Civil Rights matter

when in fact it really is not. THE ONLY REAL

ISSUE IN THESE THREE CASES IS WHETHER

OR NOT A NORMALLY PEACEFUL AND LAW

ABIDING COMMUNITY FACING AN EXPLOSIVE

SITUATION IN WHICH RACIAL TENSIONS ARE

AT AN ALL TIME HIGH, CAN PRESERVE THE

PEACE AND ORDER OF THE COMMUNITY BY

HAVING ITS LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS

ORDER PERSONS CREATING THE EXPLOSIVE

SITUATION TO CEASE AND DESIST FROM

SUCH ACTION AND ARREST THEM IF THEY

REFUSE TO DO' SO.

To put these cases in their proper perspective

they must be viewed in the true light of the circum

stances surrounding them. Throughout the last part

10

of 1959 and the early part of 1960, immediately pre

ceding these demonstrations, the leaders of the Negro

movement to do away with all segregation, in the

nation, whether public or private, abandoned their

previous legal mode of attack to embark upon a mili

tant campaign throughout the South to invade private

property and harass the proprietors of private business

establishments into de-segregating their facilities

whether they wanted to or not. These “sit-in demon

strations” occurred in major cities throughout the

South. In almost every instance where local law en

forcement authorities did not act quickly, violence,

to a greater or lesser degree, occurred. A rather com

plete history of this militant campaign is given in

an article in the 1960 Volume of the Duke Law Jour

nal, No. 3, from which we will trace their history.

“On February 1, 1960, four Negro students at

North Carolina A & T College in Greensboro, North

Carolina, decided to do something about this alleged

unequal treatment. They went to a dime store in an

alleged attempt to get coffee. The manager said he

could not serve them because of local custom, so they

just sat and waited. The only trouble that first day

came from the Negro help who came out of the kitchen

to tell the boys, now known on their campus as the

“Four Freshmen”, that they were doing a bad thing.

Other students from the college were shopping in the

store at the time and when the Four Freshmen re

turned to the campus 20 students volunteered to join

them for the next afternoon. “Ground rules were

drawn by the expanded group. . . . Again, Tues

11

day they were refused service. They just sat. On

Wednesday and Thursday, they returned, in greater

strength each time. The A & T students were joined

by many students from the Negro Bennett College and

also by a few students from the Women’s College of

the University of North Carolina, both located in

Greensboro. By Friday, white teenagers had begun

heckling the demonstrators. On Saturday the Wool-

worth store was jammed with Negroes and Whites.

The Negroes mostly sat, while the white boys waved

Confederate flags chanted and cursed. Around mid

afternoon the management received a bomb threat, and

the police emptied the store. When the store opened

Monday, the lunch counters were closed. Dr. Gordon

Blackwell, Chancellor of the Women’s College, pro

posed a “truce period” which was accepted to work

things out in a less inflamatory atmosphere. Thus

ended temporarily the Greensboro demonstrations;

but by that time, Negro students were demonstrating

in Winston-Salem, in Durham, in Charlotte and the

other principal North Carolina cities. The demonstra

tion in its origin was student inspired and directed.

Subsequently, organizations such as the National Stu

dent Association. The Congress of Racial Equality,

and the National Association for Advancement of

Colored People offered their guidance and sponsorship.

In some instances, the help of these organizations was

accepted; in other instances, the students desired to

go it alone.” Daniel H. Pollitt, Dime Store Demon

strations; Events and Legal Problems of First Sixty

Days; Duke Law Journal No. 3, Volume 1960. This

12

was only the beginning. And yet there was violence

on the very first attempt of these people to invade the

private property of others. As the movement increased

and became more militant, so correspondingly did the

violence increase.

Continuing with Dr. Pollitt’s rather thorough

chronological exposition of this militant campaign, we

note the following at page 319:

“. . . the demonstrations moved Northward

into Virginia and West Virginia; South into

South Carolina, Georgia and Florida; Kentucky,

Alabama, Louisiana, Arkansas and Texas. Pickets

even appeared before those stores in restaurants

in Ohio which violated the state eating accommo

dation laws by denying service to Negroes. The

Raleigh News commented that with the arrest

of demonstrators in that city, The picket line now

extends from the dime stores to the United States

Supreme Court and beyond to national and world

opinion’ ”.

It should be noted here that though the above quota

tions referred to 'picket lines that such is not the situa

tion in the present cases. In fact the right of these per

sons, and those similarly situated, to otherwise freely

express themselves in a place where they had a right

to be was affirmatively maintained by the law enforce

ment officials of the City of Baton Rouge on the day

immediately following their invasion of private prop

erty. Dr. Pollitt then goes on to cite the extremely

wide press coverage given these demonstrations in

cluding Eastern Europe and Russia. He mentions

13

the many nationally known figures who spoke out in

support of such demonstrations and whose remarks

was given widespread newspaper coverage such as

the Rev. Dr. Billy Graham, Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt,

United Auto Workers President, Walter Reuther,

Florida’s Governor Leroy Collins, and various church

and university organizations. The comments and

publicity which followed these demonstrations was

widely publicized throughout the South and increased

racial tensions in each and every community in the

South.

To briefly follow the route of these militant, well

organized demonstrations, State by State, as they

swept across the South, we again quote from Dr. Pol-

litt’s article.

ALABAM A

“The demonstrations reached Alabama on

February 25, when 35 Negro students from Ala

bama asked for service in the Montgomery

County Courthouse Snack Shop___ On Feb

ruary 27, a Negro woman was attacked by one of

the group of 25 whites who patrolled the streets

carrying miniature baseball bats inside paper-

bags. . . . On March 1, a thousand Negro stu

dents sang the National Anthem on the Capitol

steps, . . . On March 2, nine Negro students

were ordered expelled for taking part in a demon

stration, . . . On Sunday March 6, approxi

mately 800 Negroes left their churches for a

demonstration prayer meeting at the State Capi

tol grounds. A jeering mob of whites charged the

marchers, and a riot wTas narrowly averted

14

when the police separated the two groups, and

mounted deputies and fire trucks moved in to

prevent further violence. Pollitt, Duke Law Jour

nal, No. 3, Volume 1960, page 323 and 324..”

ARKANSAS

“Arkansas joined the list of Southern states

hit by demonstrations on March 10, when about

45 students from Philander Smith College en

tered a Little Rock variety store and sat down at

a white lunch counter. The incident ended with

out violence when Police Chief Gene Smith rec

ommended closing the counter.” (Note: No vio

lence but the proprietor had to give up his

rights.) Pollitt, page 325.

FLORIDA

“The demonstrations began in this state on

February 26, with a sit-in in Tallahassee. . . .

Ten days later, forty Negro youths staged a sit-

down protest at a Tampa Woolworth lunch coun

ter. The counter was closed without incident.”

(Note again the proprietor giving up his rights).

. . . “On March 4, eight ministers tried to enter

a lunchroom in Miami’s Burdine’s Department

Store, but were blocked by store employees. A

cross was burned in front of a Negro home in

Pensacola. . . . On March 12, demonstrations

reached Jacksonville. Eight Negroes sat down at

the lunch counter of a Kress’ Dime Store. The

counter was closed.” (Again the proprietor gave

up his right to conduct his normal business). . . .

“On the same day, there was near violence in Tal

lahassee. A group of Negro and white demon

strators at a Woolworth store were arrested, re

placed by another group that was arrested, and

15

by a third group that was arrested/’ (Notice the

similarity to a military battle, one assault wave

after another) . . . “Shortly after noon, a crowd

of about 125 Negroes gathered at a park across

the street from the police station and started

down the block toward the Woolworth store. Half

way there they were met by a group of white

men, turned and started back to their campus,

while the whites followed with taunts and jeers.”

(Near violence) . . . “On March 17, a group of

eight students entered the Woolworth store in St.

Augustine, the counter was closed, and when the

Negroes left, they were attacked by a group of

white men. Police called a cab to take the Negroes

away, and the Chief of Police, armed with tear

gas, ordered the crowd to disperse.” (Violence and

tear gas, armed police) Pollitt, Duke Law Journal,

Vol. 1960, pages 825 and 826.

GEORGIA

“. . . On March 10, seven Negroes took seats

in a white section of a municipal auditorium dur

ing a stage show. There was a brief verbal clash

that ended when police designated the occupied

section Negro. On March 15, approximately 200

students in Atlanta staged simultaneous sit-ins

at noon time at the lunchrooms of the State Capi

tol, the Courthouse, the City Hall, the bus sta

tions, the railway station, two office buildings

housing Federal offices, and a variety store.”

(Such an all out assault could not have been car

ried on without a complete and effective organi

zation almost military in its nature.) . . . “On

March 16, there was a “sit-in” in Savannah, and

on March 17, following a big St. Patrick’s Day

parade, there were scattered fist fights and rock

16

throwing between groups of whites and Negroes.”

(Violence once again)

NORTH CAROLINA

As North Carolina has been covered in our

initial discussion we will not go into it further

at this point.

SOUTH CAROLINA

“In this state the demonstrations began on

February 23 in the City of Rockhill when 100

Negro students from Friendship College staged

a sit-in in two variety stores. . . . On March 3,

approximately 200 Negro students marched

around in the Columbia downtown area for near

ly two hours. They were heckled by white youths

and left at the request of the city manager who

wanted to avoid “an explosive situation” . . .

On March 15, approximately 1,000 demonstra

tors from Chaflin and South Carolina State

Colleges converged at noon in Downtown Orange

burg to protest lunch counter segregation. The

police met them with tear gas and fire hoses.”

(Emphasis added). Pollitt p 331.

TENNESSEE

“Chattanooga was the scene of the first

Tennessee demonstration, when Negro high

school students staged a sit-in in the Kress store.

Rioting broke out when whites, mostly students,

began throwing flower pots, dishes, bric-a-brac,

and other merchandise in the store. One white

youth grabbed a bull whip from the store stock

and used it on a Negro. The Negroes retreated

through the streets to a Negro section of the

city, with bricks and other objects being hurled

17

by both sides. After the fighting had subsided,

white youths walked through the aisles of the

Kress and other stores, jeering at Negro custom

ers and frightening many into leaving. . . .

Seven whites were arrested, the police concen

trating on the leadership.” (Notice again that the

arrests for disturbing the peace or causing the

violence are indiscriminate as to color). . . . “The

demonstrations then spread to Nashville. A white

youth was sitting with a group of Negroes at a

dime store lunch counter when a second white

youth walked in, called him a -------------- , and

twisted his collar. The assailant then fled, but

returned five minutes later. This time, he grabbed

the sitting white youth, threw him on the floor,

and kicked him. The police then ordered every

body to leave the counter. Eleven Negroes who

refused to comply were arrested.” (It is worth

noting here that arrests were made only after

violence and requests for everyone to leave and

the only persons arrested were those who refused

to leave.) . . . “Two days later, fifty-five more

Negro students were arrested, this time for re

fusing to leave the lunch counter at the Grey

hound bus station when, the Assistant Fire Chief

asked all persons to leave the building while a

search for a bomb was made. . . . Two weeks

later, shortly after the Nashville bus station

served Negroes in the white restaurant, two

dynamite caps—but no dynamite—were found in

the washroom. Pollitt, Duke Law Journal, Vol.

1960, No. 3, pages 332-33A” (Emphasis added)

TEXAS

“The demonstrations in Texas resulted in

extremes—either of violence or of peaceful settle-

18

ment. The sit-ins began in Houston, mostly by

Negro students from Texas Southern University,

with immediate repercussions. A Negro drug

store porter was slashed by a white youth with a

knife, and three masked white men seized another

Negro, flogged him with a chain, carved the in

signia of the Ku Klux Klan on his chest and

stomach, and hanged him by his knees in an

oak tree. In the east Texas city of Marshall,

demonstrations began on March 2 7 ,.. . On March

30, . . . about 200 Negroes gathered near the

courthouse and began to sing “God Bless Ameri

ca” and similar songs. The firemen then arrived

and turned powerful streams of water into the

crowd. Hoses drenched West Houston Street,

which leads to Marshall’s two all-Negro colleges

. . . In contrast with the situations in Houston

and Marshall is that in San Antonio. Through

the intervention of the Rev. C. Don Baugh, exec

utive director of the San Antonion Council of

Churches, downtown dime stores agreed to serve

Negroes . . . In Galveston, too, lunch counters

were voluntarily integrated and Negroes started

eating beside whites without incident.” Pollitt,

p. 334,-335.

VIRGINIA

“The demonstrations began in Richmond

with a sit-in at the restaurant in Thalhimer’s

department store. Thirty-three participants were

arrested, which prompted a picket line urging a

boycott . . . The protest demonstration ran a

course similar to that in other states. Pollitt,

Duke Law Journal, 335-336.

And again to quote Dr. Pollitt a t page 336 of his

19

exposition, “ ‘the determination that underlines the

movement has been demonstrated from Alabama to

Virginia’ comments the New York Times.” “Negroes

have risked fines and jail sentences, attacks from

angry Whites, and, in at least one case, possible death

at the hands of a mob.”

The purpose in quoting from Dr. Pollitt’s ex

position is not to try to assess the blame for any

particular incident of violence in any of the com

munities in which it occurred on either the white

race or the colored race in that particular community.

The purpose is to show the very thorough campaign

that was carried on throughout the Southern states

in the brief two months prior to the incident occur

ring in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It is also to point

out that where arrests were made by the local law en

forcement officers early and quickly, no violence oc

curred, but where local law enforcement officers

stood by and allowed the demonstrations on private

property to continue, violence eventually occurred.

Another purpose in quoting these incidents is to show

that the right of these people to freely express them

selves by picketing, marching through the public

streets, marching on the courthouse, etc., freedom of

expression where they had a right to freely express

themselves, was in most cases not only not inter

fered with, but was protected. Such was the case in

Baton Rouge as shown by the statement of the case.

Again, to show the militant nature and organiza

tion of these sit-in demonstrations, we would quote

at some length from the article entitled “The Strategy

2 0

of a Sit-in” by C. Eric Lincoln in the January 5, 1961,

issue, Volume 2k No. 1 of the Reporter magazine, pages

20-23. Although the writer of the article obviously

supports these sit-in movements, his description of

such movement is certainly well worth noting. For

example, his article is broken into sections as follows:

(1), First Skirmishes; (2), Logistics and Deploy

ment; (3), All Right Lets Go; and (4), Allies and

Morale. We will quote at some length to give an idea

of the development of the sit-ins campaign as con

ducted in Atlanta.

“. . . “What came to be referred to as the ‘fall

campaign’ got under way immediately after the

re-opening of the colleges in mid-September. This

time the main sit-in targets were in the heart

of Atlanta’s shopping district. Because of its size

and its alleged ‘leadership’ in the maintenance of

segregated facilities, Rich’s became once again the

prime objective . . . By Friday, October 21,

hundreds of students had launched attacks in

co-ordinated waves. Service to anyone at eating

facilities in the stores involved had all but ended,

and sixty-one students, one white heckler, and

Dr. Martin Luther King were all in jail. Negotia

tions between the merchants and the Students-

Adult Liaison Committee were promised on the

initiative of the mayor. When the truce ended

thirty days later, no progress had been made in

settling the impasse, and on November 25, the

all out attack was resumed. By mid-December,

Christmas buying was down sixteen per cent—

almost $10 million below normal.

21

Both the Atlanta police and the merchants

have been baffled by the students’ apparent abil

ity to appear out of nowhere armed with picket

signs, and by the high degree of co-ordination

with which simultaneous attacks were mounted

against several stores at once. . . . The secret of

their easy mobility lay in the organization the

students had perfected in anticipation of an ex

tended siege.

Much of the credit for the development of

the organizational scheme belongs t o _________

who is the recognized leader of the student move

ment in Atlanta, and his immediate “general

staff” . . . its executive officer has the rather

whimsical title of “le Commandante”. The head

quarters of the movement are in the basement of

a church near the University Center, and (le

Commandante), arrives there promptly at seven

o’clock each morning and goes through a stack of

neatly typed reports covering the previous day’s

operations. On the basis of these reports, the

strategy for the day is planned. . . . Meanwhile,

the Commandante and his staff are in conference.

. . . Deputy Chief of Operations . . . will have ar

rived, as will a fellow student, . . . who serves

as field commander for the committee. . . .

Telephoned reports from Senior Intelligence Offi

cer . . . (already at his post downtown), will

describe the nature of the flow of traffic at

each potential target. . . . A large map dividing

the doivntown district into five areas is invari

ably consulted and an Area Commander is

appointed for each operational district. Assign

ments fall into three categories: pickets (called

2 2

by the students “picketeers” ), sit-ins, and a sort

of flying squad called “sit-and-runs.” The objec

tive of the sit-and-runs is simply to close lunch

counters by putting in an appearance and re

questing service. . . . By now it is nine or nine-

thirty and transportation has arrived. . . . The

Deputy Commander provides each driver with a

drivers orientation sheet outlining in detail the

route to be followed by each driver, and the

places where each of the respective groups of stu

dents are to be let out. The Area Commanders

are given final instructions concerning the syn

chronization of the attack, and the cars move off,

following different routes into the city. . . .

Meanwhile, Field Commander . . . is checking a

communications code w ith _________, or one of

the five other licensed radio operators who man

a short-wave radio set up in the church nursery.

When this has been attended to, Commander

------------- climbs into an ancient automobile

equipped with a short-wave sending and receiving

unit and heads for the downtown shopping dis

trict. He is accompanied by _________, whose

job it will be to man the mobile radio unit. . . .

Reports from the Field and Area Command

ers begin to trickle in by radio and telephone.

As the lunch hour nears, the volume of reports

will increase to one every two or three minutes.

. . . Here are two actual reports taken from the

files and approved for publication by the Secu

rity Officer:

11-26-60 11:05 A.M.

From: Captain _________

To: le Commandante

Lunch counters at Rich’s closed. Proceeded

23

to alternative objective. Counters at Wool-

worth’s also closed. Back to Rich’s for picket-

duty. Ku Klux Klan circling Rich’s in night

gowns and dunce caps. “Looking good!”

(Emphasis throughout added)

The above quoted portions from this article should be

sufficient to show that regardless of the statements of

the leaders of some of these and other movements

about “passive resistance” etc., these movements are

anything but passive. They are well organized and

well supported financially. No reasonable man can

read the examples cited by Dr. Pollitt, the militant

campaign described by Mr. Lincoln, and know of

the high degree of racial tension which exists through

out the South, without coming to the conclusion that

it is entirely foreseeable that these demonstrations

can disturb and alarm the public and result in vio

lence. Must the individual communities throughout

the South, and for that matter, the nation, wait until

violence occurs and mobs run rampant before taking-

action? Or may they profit by the experience of other

cities and protect the rights of these people when they

are demonstrating where they have a right to demon

strate and order them to cease and desist when they

are demonstrating on private property where they

have no right to do so?

Counsel for defendants and the Federal Govern

ment, in argument in their brief, object to the City

of Baton Rouge foreseeing violence in these demon

strations. But how can you read the history of these

demonstrations, the history of this militant movement

24

from the time it began some short two months before

these cases arose, and thereafter, without foreseeing

violence as a result thereof. There is only one possi

ble way to eliminate the probability of violence from

these demonstrations. And that is for the private prop

erty owner to completely relinquish his right to re

fuse admission to his property to other people for

whatever reason he might have, and particularly for

an unwanted demonstration. In the absence of his do

ing so, there are only three possible results, (1), that

these people continue to occupy seats which would

normally be used by other patrons of his business,

thereby interfering with his business and a trans

gression against his own civil rights; (2), violence,

resulting from the proprietor attempting to forceably

evict these people or other people attempting to use

the seats which these people have taken and which,

according to the proprietor, his other patrons have a

right to use; or (3), their being forceably removed

and/or arrested by local law enforcement authorities

in a proper effort to protect the rights of its citizens

and avoid violence and disorder in our community.

And furthermore, if violence is not foreseeable

as a result of these “sit-ins” “freedom rides”, etc.,

why does the Federal Government send hundreds of

Federal Marshalls into Montgomery, Alabama, Jack-

son, Mississippi, and New Orleans, Louisiana? The

Government took the position that discrimination in

bus stations and railway stations in Montgomery,

Alabama, was unlawful and it therefore called upon

the law enforcement officials of Montgomery, Ala

25

bama, to arrest any one who interfered with the

exercise of the right of the defendant to go where

he chose in such interstate facility. And when the

government felt that the Montgomery law enforce

ment officials could not cope with the situation, and

foresaw possible violence as a result thereof, the gov

ernment sent several hundred Federal Marshals to

Montgomery for the express purpose of preventing

violence. Yet, in the instant three cases, the govern

ment cites no authority, no law, no constitutional

provisions, and no case that says these defendants

have a right to demonstrate on private property or

have a right to remain on private property ofter being

told they would not be served and asked to leave.

In other words, the government felt a responsibility

to protect the rights of these Negro people under the

Interstate Commerce Act, and to prevent violence,

and it moved immediately with its law enforcement

officials to do so. Why does it not feel the same

responsibility to protect the rights of other citizens

or, at least, not oppose the protection of those rights,

and the prevention of violence, by the City of Baton

Rouge?

So then, we come to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on

the morning of March 28, 1960. For the preceding

month and a half the newspapers had been carrying

story after story of the sit-in demonstrations and

resulting violence in other cities. Headline stories of

one group of people violating the property rights of

another group of people and being supported therein

by outstanding national figures and the Federal

26

Government. Stories of people refusing to leave another

individual’s property after having been requested to do

so, the type of conduct which is, to the people in

Baton Rouge, completely unlawful and a direct affront

to their normally law abiding nature. Couple this with

already inflamed emotions and high racial tension

which has become increasingly worse since 1954. What

were responsible citizens and officials charged with

the responsibility of preserving peacefulness and law

and order in the community to do? Were they to

order the proprietors of private businesses to open

their doors to these people to permit them to come in

even though they did not wish them to do so? Should

they have arrested these proprietors if they refused

to allow these people to come in? Hardly, because

there was no legal authority for them to do so. What

then? Must they have waited until violence, fist fights,

brick throwing, etc. finally commenced? Should they

have waited until the proprietor attempted to force-

ably remove these people with its resulting violence

and possible damage to his store? And if so, who then

should they have arrested for disturbing the peace?

According to the defendants, it would be the pro

prietor. But what has the proprietor done, except

to exercise his own right to refuse admission and to

eject those who refuse to leave when requested to

do so? I cannot believe that it is the intention of this

Court to tell individual communities throughout the

nation that you may not take quick action to prevent

violence and disorder in your community by quickly

arresting persons engaging in a demonstration on

27

private property against the owner’s wishes, but must

instead wait until violence and disorder actually occur.

Such a concept turns our civilization back, not hun

dreds, but thousands, of years.

It should be noted at this point that although

the stated respondent in this matter is the State of

Louisiana, the State is not the real party at interest.

The real party at interest in all three of these cases

is the City of Baton Rouge, the community of Baton

Rouge. Disorderly conduct or mob rioting in the City

of Baton Rouge affects no one else in the State of

Louisiana. The only people concerned here with keeping

the peace, people who would desire to carry on their

normal daily activities without being subjected to

possible violence and disruption of those activities, are

the people living in the local community known as the

City of Baton Rouge. What is a local community,

whether it be located in the State of Louisiana, Idaho,

New York, California or Nevada, to do in these cir

cumstances? A local community in these circumstances

has, actually, only three choices: (1), it may sit idly

by and allow these persons to possess a portion of the

property of another of its citizens, for an unwanted

demonstration, against his wishes, until that citizen

relinquishes his own rights; (2), it may sit idly by

until that private citizen attempts to forceably eject

these persons with the resulting violence, and prob

able spreading of such violence and disorder to its

other innocent citizens; or (3), it may act quickly, for

the benefit of all of its citizens, to prevent and termi

nate such illegal demonstrations, before violence and

28

disorder occur, by ordering these persons to leave the

premises and cease and desist from such illegal dem

onstrations and then by arresting such persons if

they refuse to leave at the request of law enforcement

officials. It seems obvious to the writer that under

the circumstances and conditions so readily apparent

in these cases, so readily apparent from the record

itself, that the proper course, the more reasonable

course, the more prudent course, is to act quickly and

preserve the peace, order, and tranquility of the com

munity.

The defendants and the government, by taking

isolated answers from the testimony reflected in the

record in these three cases, make much of the con

tention that these defendants were following a nor

mal every day course of conduct in seeking service

and that there is no evidence in the record to justify

a conviction. However, we respectfully submit, that

it is impossible to read all of the testimony of the

proprietors, managers and employees of the three

places of business involved and the sworn motions

to quash in which the defendants testify and admit

that they were “engaged in an activity to protest

segregation” and that they did “in protest of the

segregation laws of the state of Louisiana, . . . on

the 29th day of March, 1960, ‘sit-in’ a cafe counter

seat . . . ”, without coming to the inescapable con

clusion that there is ample evidence in the record that

these defendants were engaged in participating in an

unwanted anl illegal demonstration on private prop

erty against the wishes of the owner and that after

29

being requested to remove themselves and cease and

desist with such demonstration, both by the owner,

manager or employee, and police officers, refused to

honor such request or obey such direction from the

local law enforcement authorities. And, as admitted

by the government on page 18 of its brief, “the deci

sion (Thompson vs. City of Louisville, S62 U.S. 199,

and others cited) does not mean that a Federal Court

may reverse a state conviction merely because, upon

re-evaluating the record, it finds that the evidence is

insufficient to support the conviction.” We respect

fully submit, that there was evidence in the records

to support these convictions and that, therefore, this f

Honorable Court should not substitute its judgment

for that of the jury or trial court, as the case may be,

as to whether or not the verdict should have been

guilty or not guilty.

Now, with the background of this militant cam

paign before us, let us look at the situation in the

one community involved, Baton Rouge, Louisiana,

during these three days of demonstrations. Of course,

the Baton Rouge newspapers had been, for the past

several weeks, printing the same stories which appear

in Dr. Pollitt’s article. The Baton Rouge morning

paper, the Morning Advocate, of Sunday, March 27,

1960, carried the following headline and story:

“NEGRO PROTESTS SPREAD — PICK

ETING, PARADES, AND RALLIES STAGED

OVER WIDE AREAS.”

30

“Mass anti-segregation demonstrations in

support of Negro lunch counter sit-downs in the

South spread across the country Saturday . . .

“Newport News, Virginia, Focal point of the

nation-wide demonstration movement which stu

dent leaders called ‘operation 26’ . . . Sit-down

protests occurred in many cities, among them

Charleston, West Virginia, and there was pick

eting in Savannah and Atlanta, Georgia — In

Atlanta, a spokesman for CORE (Congress of

Racial Equality) said 25,000 leaflets were being

distributed urging a boycott of stores with segre

gation policies . . . More than five hundred per

sons belonging to CORE and another interracial

group posted picket lines at 20 variety stores in

the downtown Los Angeles area. None of the

stores have a segregation 'policy. They were the

latest sympathy protest in the Los Angeles area

. . (Emphasis added)

On Monday morning March 28, 1960, the Morn

ing Advocate carried the headlines “CROSSES

BURNED IN DEEP SOUTH STATES; STUDENTS

STAGE DESEGREGATION DEMONSTRATIONS”

In the Baton Rouge evening paper, The State Times,

of March 28, 1960, the headlines and story were as

follows:

“CROSS BURNINGS ARE REPORTED IN

SEVERAL STATES OVER THE WEEK END.

“The ninth week of anti-segregation dem

onstrations began in the South today following

a week-end of cross burnings.

31

Hooded klansmen burned crosses in Alabama,

Georgia, Florida and South Carolina as students

in the North and west joined Negroes in their

campaign against separate lunch counter facili

ties . . . Both white and Negro students support

ing the campaign of Southern Negroes picketed

stores in State College, Pennsylvania, Iowa City,

Iowa, Los Angeles, California and Albany, New

York. . . . A special Mayor’s committee said

the Nashville incident wiped out three weeks of

work to ease racial tensions . . .

(Emphasis added)

On Tuesday, March 29, 1960, the Morning Advocate

carried the following headlines on opposite sides of

the page:

“NEGRO STUDENTS ARRESTED HERE

AFTER SIT-DOWNS; GROUP OF SEVEN

JAILED, LATER BONDED; SOUTHERN

(SOUTHERN U N I V E R S I T Y ) RALLY

THREATENS BOYCOTT”

“CHURCHES BURNED AS AFRICAN AU

THORITIES BATTLE NEGRO MOBS—DEM

ONSTRATORS FIGHT POLICE, OTHER

NEGROES.

“Great fires set by mobs raged Northeast of

Cape Town Monday night as white police battle

with Negroes and militant Negroes fought both

police and other Negros. It was the fiery, violent

climax to South Africa’s “day of mourning”.

Again, on Tuesday afternoon, March 29, 1960, the

Baton Rouge State Times carried the following head

line and story:

32

“TWO ARRESTED IN SECOND ‘SIT-

DOWN’ INCIDENT.”

Negro students from Southern University

here today continued their sit-down lunch counter

demonstrations with an invasion of Sitman’s Drug

Store at Main and North Third Street . . . ”

Then, on Wednesday morning, March 30 of 1960,

the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate carried the fol

lowing headline and sub-headline:

“THIRD STREET BOYCOTT BY NE

GROES URGED AFTER NEW SIT-DOWN

CASE. SEVEN MORE STUDENTS ARREST

ED HERE; REPORT CROSS BURNING—NE

GRO MINISTER ASKS CONGREGATION TO

CEASE SHOPPING AT EASTER SEASON”

And on Wednesday afternoon, March 30, the Baton

Rouge States Times carried the following headlines

and story:

“NEGROES MARCH D O W N T O W N ;

GRAND JURY BEGINS INQUIRY—TWO

THOUSAND DESCEND IN MASSE ON THIRD

STREET; SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY HEAD

PROMISES POSITIVE ACTION AGAINST

SOME STUDENTS”

“Some two thousand Southern University

Students marched on downtown Baton Rouge

and the State Capitol at 9 A.M. today, and nearly

five hours later the Parish Grand Jury began a

full scale investigation of a three day series of

33

Negro demonstrations here . . . and Mayor-

President Jack Christian asked citizens of the

Parish to keep away from heavily patrolled areas

and urged people to ‘let your law enforcement

agencies take care of this situation’ . . . The

students, orderly, quiet and obviously well-briefed

as to behavior marched on the State Capitol and

after picketing briefly the Greyhound Bus

station, McCrory’s, S. H. Kress & Co. and Sit-

man’s Drug Store at Third and Main . . . Dem

onstrations reached a peak today after lunch

counter sit-downs Monday and Tuesday . . .

Dr. Clark (Dr. Felton Clark, President of

Southern University) said in a prepared state

ment; “We have consistently advised students

against the course of action which a segment of

them are now taking . . .’ (Emphasis added)

Mayor-President Christian said in a state

ment; . . . If the people will refrain from coming

to the areas patrolled, it will be much easier to

handle the flow of traffic and will keep the con

gestion downtown to a minimum . . . The thing

that bothers us is that someone may do some

thing violent which of course will make it very

difficult for our present forces to handle the

situation . . . We are doing our best to prevent

any acts of violence or injury to anyone or to any

one’s property and so far we have succeeded. . .

In the midst of the morning demonstration,

City Police received a report of a bomb in Sit-

man’s Drug Store, scene of a Negro lunch

counter sit-down strike yesterday. The store was

closed by police and sidewalks made off limits

to pedestrians while a thorough search was

made.” (Emphasis added)

34

Finally, the Morning Advocate of Thursday

March 31, 1961, at a time when, as far as local

authorities knew, these demonstrations were scheduled

to continue and to spread, carried the following head

lines and stories:

“S U S P E N S I O N FOLLOWS BATON

ROUGE DEMONSTRATIONS; THE THIRD

DAY OF UNPRECEDENTED DEMONSTRA

TIONS AGAINST SEGREGATION BY NEGRO

STUDENTS HERE WEDNESDAY . . . ”

On the opposite side of the page there was the

following headline:

“HOSES BREAK UP TEXAS NEGRO

DEMONSTRATION.”

“Firemen turned streams of water into

groups of young Negroes late Wednesday to calm

a demonstration lunch counter incident.”

Is it possible to read the history of these “sit-in”

demonstrations and the content of news which the

general public in Baton Rouge was receiving prior to

and at the time of these incidents, as shown by the

preceding headlines and stories, and say that there

was not sufficient probability of violence or disorder

to justify the stopping of these demonstrations?

Neither the city of Baton Rouge, nor the State of

Louisiana for that matter, was attempting to persecute

anyone, or deprive any citizen of any of their rights,

in the action that they took in the midst of these

sit-in demonstrations which resulted in the arrests in

the present cases. To the contrary, it seems to us to

be obvious that all the law enforcement officials of the

35

City of Baton Rouge did, was to take only such action

as was absolutely necessary to preserve order, peace

and tranquility in our community, to avoid violence,

disorder and mob rioting and preserve the stable,

moderate, law abiding community which we have.

That they were not trying to deprive anyone, much

less these defendants and others similarly situated,

of any of their constitutional rights, appears obvious

from the fact that not only did the law enforcement

officials not interfere with these persons when they

were picketing or when they were demonstrating on

the public streets and marching on the State Capitol,

they actually enforced and protected their right to do

so. Only when they moved their demonstration to a

place ivhere they had no right to be for such purpose,

did law enforcement officials take any action. Further

more, there can be no doubt that a probability of

violence existed and that these defendants, being

reasonable people, should have known, and in fact

did know, of such probability. The statement by the

Mayor of Baton Rouge indicates the concern with

which public officials viewed these demonstrations

when he said “we are doing our best to prevent any

accident, violence or injury to anyone or anyone’s

property and so far we have succeeded”.

In the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate of March

31,1961, the publishers set forth a front page editorial

(which in itself indicates the concern with which

responsible citizens viewed these demonstrations) and

which we believe to be worthwhile to quote from at

length at this point.

36

“LET’S KEEP OUR HEADS”

“The good relationship between the races in

Baton Rouge is threatened by the utterance of

the ugly word ‘boycott’ a development which we

are sure most leaders in both races in the com

munity regret. This is an unnecessary and unwise

threat aimed at people . . . .

It is unfortunate that the excellent relation

ships which have prevailed should be interrupted

even slightly, as they have been, by a spread

through this city of the ‘sit-in’ demonstrations

conducted by Negro college students with much

excitement but little lasting effect in a number of

other communities. . . .

These are times that require understanding,

good will, and patience, regardless of how hard

these things may sometimes come to some among

us. The recognition and acceptance that really

count cannot be hastened or ever won by any

action that creates alarm, destroys good will or

alienates the different groups in the community.

Anyone on either side of such a controversy who

threatens or hints at mob action automatically

destroys the very thing for which he claims to

be struggling. Civilized people of all races are

revolted and offended by the thought of violence

and disorder.

Radicals on one side must realize that no

changes can be brought about by immature dem

onstrations and disorders. Radicals on the other

side must realize that changes cannot be prevented

by threat or intimidation. The great majority of

the people, who want none of all this, will con

demn both. Our society may have its imperfec

37

tions, as do all things of human design. But this

is not the way improvements will be brought

about. Time and orderly evolution can bring prog

ress. Force, can bring none.” (Emphasis added)

As will be seen from the foregoing, no matter how

many isolated sentences are taken from the testimony

in these three cases, and regardless of the argument

that these defendants were in these establishments for

normal business purposes, it is abundantly clear that

these defendants were engaged in a demonstration to

protest the segregation customs of the people of the

State of Louisiana, and invaded private property for

the sole purpose of carrying on their organized

demonstration. It is also abundantly clear that the

carrying on of such demonstrations on private property

against the owner’s wishes was the doing of an act in

such a manner as would foreseeably and unreasonably

disturb or alarm the public.

The government contends in its brief that the

Trial Court must ignore the circumstances surround

ing these cases and the fact that they were a part of a

well organized militant movement or so called pas

sive harassment; and that he must ignore the fact that

such conduct is likely to “disturb the sensibilities” and

“arouse resentment” among other members of the

public and the owner, and their agents and employees,

of the business establishments invaded. They refer

to such as taking “judicial notice” and then cite the

cases of Ohio Bell Telephone Company v. Public

Utility Commission, 301 U.S. 292; United States v.

Shaughnessy, 234 Fed. 2nd 715; and McCormick evi-

38

clence Section 32k (195k) for the proposition that

Courts can take judicial notice, especially in criminal

cases, only of obvious and incontrovertible facts. (Gov

ernment Brief pages 25 and 26) However, Louisiana’s

Courts are specifically authorized by state statute to

take judicial notice of that which the trial Judge in

these three cases took judicial notice of, if the taking of

judicial notice was necessary at all, that is, racial con

ditions prevailing in the state. LRS 15:422, originally

adopted as Act No. 2, Section 1, of 1928, provides in

part as follows:

“Section 422. Judicial notice of specific

matter.

Judicial cognizance is taken of the following

matters: One, . . . (6) the laws of nature, the

measure of time, the facts disclosed by the cal

endar, the facts of geography, the geographical

and political division of the world, the facts of

history and the political, social and racial condi

tions prevailing in this state; (emphasis supplied)

Taking judicial notice of racial conditions pre

vailing in the State has been sustained by the Louisi

ana Supreme Court and is particularly worth noting

in the case of State v. Bessa et al 115 La. 259, 38 So.

985 (1905). In this case the two defendants, Negroes,

were convicted of striking a white man with intent to

murder and were sentenced to seven years in the peni

tentiary. The defendants reserved a Bill of Exceptions

to a remark made by the District Attorney in the

peroration of his opening address to the jury. Ac

cording to the defense the prosecuting attorney had

39

said to the jury that the victim (a white man) was

to the jurors trying the case “a creole fellow brother

in blood”. According to the District Attorney he had

said to the jury “a fellow brother in blood” had been

met by two unknown riders, and assaulted . . . The

Trial Judge’s statement as to what occurred was as

follows: “In his opening address to the jury the Dis

trict Attorney referred to the prosecuting witness

as a “creole fellow in blood” . . .”

The Louisiana Supreme Court ruled as follows

on this point:

“Taking the statement of the Judge, and

assuming that the word ‘brother’ was not used

—in other words, assuming that the expression

was simply ‘fellow in blood’ and not ‘fellow

brother in blood’—the question may be asked:

Why did the District Attorney bring up the mat

ter of blood, if not to draw the color line? Here

was a jury all white, and two Negroes being tried

for striking a white man and nearly killing him.

The Court thinks it knows enough of the situation

between the whites and the Negroes in Louisiana

to knoiv that the average white man is prone

enough to be prejudiced in such a case, without

being exhorted thereto by the law officer of the

government, and that, such an appeal having

been once made, the effect thereof cannot be

counteracted by any mere cautionary words of

sober reason that may be uttered by the Judge.”

The Court then reversed the conviction on the basis

of the remark made and its having taken judicial

notice of racial conditions prevailing in the state. Con

sequently, we respectfully submit, that if knowledge

40

of the fact that these sit-in demonstrations are part

of a well organized and deliberate movement of dem

onstration against segregation customs, and knowl

edge of the tensions existing between the races in

Baton Rouge, is the taking of judicial notice, the Trial

Court Judge was amply authorized by the law of Lou

isiana to take such notice.

It is interesting to note, however, that the govern

ment then goes on to say (Government Brief, page

26) that, “of course, it is plain that petitioners con

duct was likely to disturb the sensibilities of those

members of the public who hope for the preservation

of racial segregation in restaurants and at lunch

counters. It will arouse resentment among the preju

diced. . . .”

I could not agree with the government more that

it would so “disturb the sensibilities” and “arouse re

sentment”. And certainly, if such is so “plain,” it is

just as “plain” that these demonstrations, and this

method of protesting segregation customs, could “dis

turb the sensibilities” and “arouse resentment” among

the unprejudiced, law abiding citizens, who abhor

such an invasion of private property.

II.

The sta tu te under w hich petitioners w ere convicted

is alm ost identical to sta te s tatu tes and m unicipal

ordinances w hich have been sustained throughout

the nation and as applied to these facts and circum

stances is no t so vague, indefin ite and uncerta in as

41

to o ffend the due process clause of the F ourteenth

A m endm ent.

Defendants further contend, through a rather

complicated, almost mathematical-formula-like re-ar

ranging of words, that there is no evidence that de

fendants committed any acts bringing them within

the ambit of LRS 14:103, or that, if there is such

evidence, the statute, as applied to the defendants in

these cases is so vague and indefinite as to be uncon

stitutional. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

The statute in question is almost identical to statutes

and ordinances used in almost every city and every

state in the union. Disturbing the peace, order and

tranquility of a community can consist of so many

different types of acts under so many different kinds

of circumstances that to require the state to specif

ically list and particularize each and every such act,

would require an impossibility. A very thorough dis

cussion of this proposition is made by the Appellate

Court of Florida in its opinion in the cases of Steel,

et al v. City of Tallahassee and Armstrong v. City

of Tallahassee No. 671 in which this court refused

certiorari at its October term 1960. ------------- U.S.

_________ The Court said:

“the charge and the ordinance seek to deal with

conduct similar to that embraced within the com

mon law offenses of ‘breach of the peace’ and

‘disorderly conduct’. . . . The former, breach of

peace, is somewhat more restricted and reaches

only conduct which disturbs or tends to disturb

the tranquility of the community. This would ob

42

viously include fighting, damaging of property,

threatening injury, display of firearms, loud and

boisterous language, menacing gestures in an an

gry manner, excessive noise and other conduct

which would put others in terror for their safety

or would be destructive to their reasonable com

fort. However, such clear rashness is not the ex

tent of the scope of the offense. An act of vio

lence or an act likely to produce violence is with

in its orbit, but also embraced are acts which, by

causing consternation and alarm, disturb the

peace and quiet of the community. Cases cited in

5 Words and Phrases page 767 under topic “Vio

lence”. Blackstone is quoted as saying that, be

sides the actual breach of the peace, anything

that tends to provoke or excite others to break

it is an offense of the same denomination. . . .

The term “peace” used in this connection is

said to mean the tranquility enjoyed by the citi

zens of the municipality or the community where

good order reigns among its members. This is the

natural right of all persons in political society

and any violation of that right is a breach of

the peace. Davis v. Burgess (Michigan) 20

Northwestern 540; 52 Am. St. Rep. 828. . . .

Testing the conduct of the appellants against

these expressions of the elements of the common

law offenses above discussed and the words

charged in Count 2, it seems clear that such con

duct came within the condemnation of the ordi

nance and within the offense charged in the

count. Though there was no violence actually

displayed or patently threatened or noisy tumult

made or exhibited, yet the willful, obstinate and

persistent refusal to vacate after a representative

43

of the owner and management had requested it

was an ominous threat to the tranquility of the

vicinity. Stubborn determination to hold onto the

private property of another until some distaste

ful policy of another is altered to the transgres

sor’s liking, would be greatly disturbing to the

management, other employees of the business and

all others who may be present.

In State v. Cooper, (Minnesota) 285 North

west 903, 122 ALE 727, it was held that defend

ants conduct in carrying a large banner some

three feet in length on each side of which was

printed the words “Unfair to private chauffeurs

and helpers union, Local 912” immediately in

front of a private home in an exclusively resi

dential district was held sufficient to sustain a

conviction of violation of an ordinance forbid

ding the making, aiding, countenancing or assist

ing in making any disturbance or improper diver

sion. . . . In sustaining the conviction the court

said:

“Defendants conduct was likely to arouse

anger, disturbance or violence. That there was

no outburst of violence was not due to his behav

ior but to the fortunate circumstance that he was

arrested and taken away before any trouble broke.

The defendants presence at the McMillian home

carrying this banner was likely to provoke trou

ble and breach of peace___” (Emphasis added)

This position is further strongly supported by

the case of People v. Feiner, (1950) 300 New York

391, 91 Northeastern 2nd 316, conviction affirmed at

SkO U.S. 315. In this case the defendant was convicted

44

of disorderly conduct under a statute of the State of

New York which read in part as follows:

“Any person who with intent to provoke a

breach of the peace, or whereby a breach of the

peace may be occasioned, commits any of the fol

lowing acts shall be deemed to have committed

the offense of disorderly conduct;

. . . 2. acts in such a manner as to annoy,

disturb, interfere with, obstruct, or be offensive

to others;” (Emphasis added)

In this case the defendant was addressing a group of

people on the street. (Note here that the defendant

was on a public street where he had a right to be).

Among other things, the defendant called the Mayor

a “champagne sipping bum” and President Truman

a bum, referred to the American Legion as Nazi

Gestapo Agents, and then said that the 15th Ward was

run by corrupt politicians who were operating horse

rooms. A nearby police officer, when he figured that

the crowd was “getting to the point where they

would be unruly” asked the defendant to get down

off his box. After the defendant refused three times,

the policeman arrested him and he was subsequently

charged under the above quoted ordinance. The New

York Appellate Court affirmed the defendant’s convic

tion under sub-section 2 of the statute, as quoted

above, saying that it was well settled that the judg

ment of conviction in a case such as this will be

affirmed if the evidence establishes a violation of any

of the subdivisions of the section. (Here, it was sub

section 2 which prohibits “acts in such a manner as to

45

annoy, disturb, interfere with, etc.”) The court also

said that the officer was “motivated solely by a proper

concern for the preservation of order and the pro