Ricks v United States of America Appeal

Public Court Documents

December 23, 1968

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ricks v United States of America Appeal, 1968. 164d196e-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b9b9b20b-ace0-4a63-8b0c-c4acbbb7f377/ricks-v-united-states-of-america-appeal. Accessed February 02, 2026.

Copied!

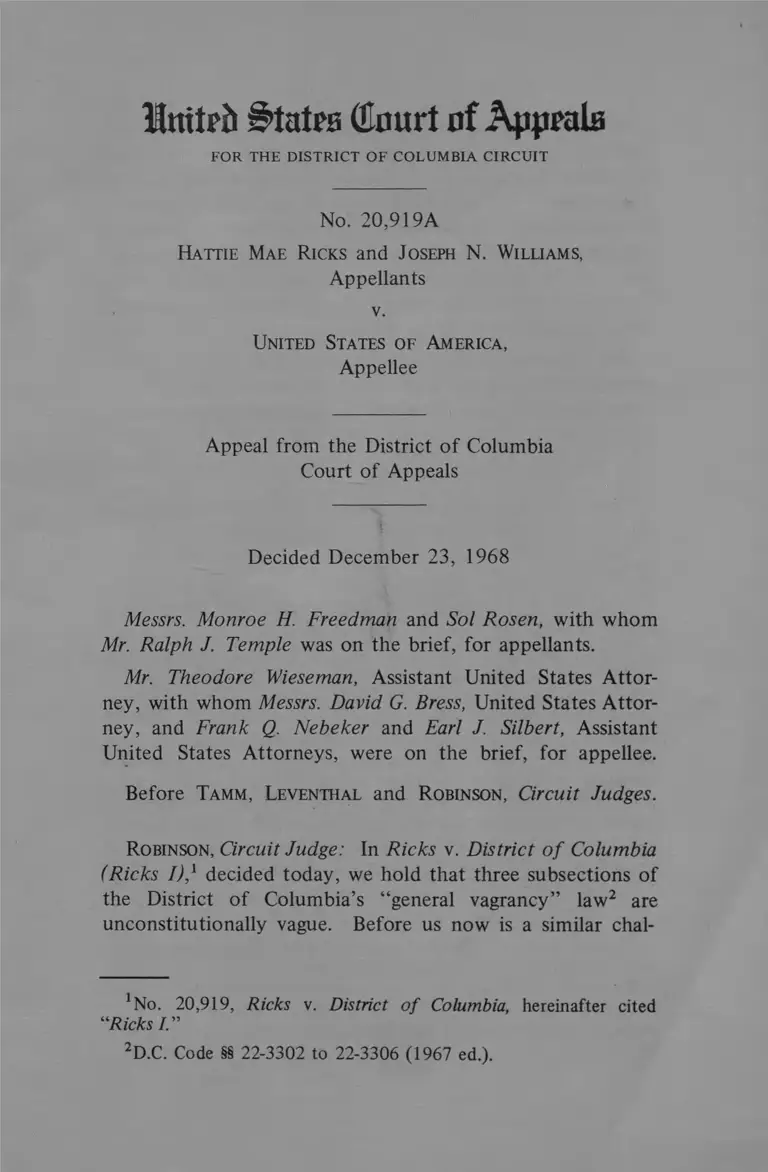

Unite S late (fnurt of Appeals

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 20,919A

Hattie Mae R icks and J oseph N. Williams,

Appellants

v.

United States of America,

Appellee

Appeal from the District of Columbia

Court of Appeals

Decided December 23, 1968

Messrs. Monroe H. Freedman and Sol Rosen, with whom

Mr. Ralph J. Temple was on the brief, for appellants.

Mr. Theodore Wieseman, Assistant United States Attor

ney, with whom Messrs. David G. Bress, United States Attor

ney, and Frank Q. Nebeker and Earl J. Silbert, Assistant

United States Attorneys, were on the brief, for appellee.

Before Tamm, Leventhal and Robinson, Circuit Judges.

Robinson, Circuit Judge: In Ricks v. District o f Columbia

(Ricks I),1 decided today, we hold that three subsections of

the District of Columbia’s “general vagrancy” law2 are

unconstitutionally vague. Before us now is a similar chal

1 No. 20,919, Ricks v. District o f Columbia, hereinafter cited

“Ricks I.”

2D.C. Code §§ 22-3302 to 22-3306 (1967 ed.).

2

lenge3 to the “narcotic vagrancy” act4 in operation in the

District. Like its Ricks I prototype, this statute sets forth

alternative definitions of a “vagrant”5—a term here involving

indispensably narcotic drug usage or past conviction of a

narcotic offense6—and makes vagrancy under its provisions a

misdemeanor.7 And like the general vagrancy enactment,8

the narcotic vagrancy law has been implemented administra

tively with police observation procedures which are pursued

before vagrancy arrests are made.9

Both appellants were subjected to a series of pre-arrest

observations, all in the 1200 block of Seventh Street, North

west, and the testimony at trial described what was seen on

each occasion. On January 6, 1966, at 11:00 p.m., appel

3D.C. Code § 33-416a (1967 ed.).

4Appellants also urge other grounds of unconstitutionality but, in

our view of the case, it is unnecessary to consider them.

SD.C. Code § 33-416a(b)( 1) (1967 ed.). And see text infra at notes

14 and 15.

6D.C. Code § 33-416a(b)(l) (1967 ed.). And see text infra at notes

14 and 15, and note 14, infra.

7D.C. Code § 33-416a(g) (1967 ed.). It is further provided that

“ [t]he court, in sentencing any person found guilty under the provi

sion of this section, may in its own discretion or upon the recom

mendation of the probation officer, impose conditions upon the

service of any such sentence. Conditions thus imposed by the court

may include submission to medical and mental examination, and

treatment by proper public health and welfare authorities; confine

ment at such place as may be designated by the Commissioners of the

District of Columbia, and such other terms and conditions as the

court may deem best for the protection of the community and the

punishment, control, and rehabilitation of the defendant.” D.C. Code

§ 33-416a(h) (1967 ed.).

8Ricks I, supra note 1, at 2.

9Narcotic vagrancy observations involve periodic police surveillance

and questioning of a suspected narcotic vagrant, and are mechanically

similar to the general vagrancy observations described in Ricks I, supra

note 1, at note 10. Two observations normally precede a narcotic

vagrancy arrest, the suspect becoming subject to arrest upon the third

observation.

3

lant Williams was on the street with two women said to be

convicted narcotic offenders. On January 13, at 11:30 p.m.,

he conversed with another female narcotic user in front of

a building. Both appellants, on January 22 at 3:20 a.m.,

crossed Seventh Street, entered a building and remained in

the hallway for 15 minutes. Needle marks were discerned

on appellant Williams’ arm each time, and one of these

marks was said to be fresh. Each time, however, question

ing by the observing officers produced an explanation for

his presence in the neighborhood and a denial that he was

using narcotics.

Observations on appellant Ricks10 began on February 21,

1966, when she sat, for short periods after midnight, in a

carry-out shop before twice leaving with different men and

later returning alone. Two days later, at 9:30 and 9:45

p.m., she stood on the street with two women reputed to

be narcotic law violators and prostitutes; within the hour,

she was on the street alone, and at 11:00 p.m. she entered

a bar. On February 24, between 4:00 and 4:45 a.m., she

got into and out of parked cars with men behind the

wheels. On March 1, at 10:50 p.m., she was on the street

for ten minutes. She had old and new needle marks on her

arm, so the testimony ran, but on all but one occasion she

denied the use of narcotics. And each time she gave expla

nations for her presence on Seventh Street, but once admit

ted to two acts of prostitution.

The arrests occurred on March 8, 1966, about 10:15 p.m.

As officers watched from across the street, appellants stood

in the 1200 block of Seventh Street, Northwest, in the

company of “a known and admitted” gambler and two

“known and convicted” narcotic violators and prostitutes.

Appellant Williams was then engaged in an argument with

one of the women who claimed that he had “sold me some

bad stuff.”11 The accuser called the officers over and

10Also the appellant in Ricks I, supra note 1.

11 In the context of the record, the reference was to an alleged sale

of narcotic drugs.

4

repeated the accusation, which was promptly denied.12

Examination revealed “fresh marks” on both appellants’

arms and, after questioning,13 each was placed under arrest.

Appellants were prosecuted on separate informations

charging vagrancy within two of the statute’s specifications:

“(b) For the purpose of this section

’l l ) The term ‘vagrant’ shall mean any person who

is a narcotic drug user14 or who has been convicted

of a narcotic offense in the District of Columbia or

elsewhere and who—

“(A) having no lawful employment or visible means

of support realized from a lawful occupation or

source, is found mingling with others in public or

loitering in any park or other public place and

fails to give a good account of himself; or . . .

“(C) wanders about in public places at late or unu

sual hours of the night, either alone or in the

company of or association with a narcotic drug

user or convicted narcotic law violator, and fails

to give a good account of himself;” 15

At a joint trial in the Court of General Sessions, appellants

moved to dismiss the informations for alleged unconstitu

tional vagueness in the statutory proscriptions. Chief Judge

Greene, noting the similarity of the general and the narcotic

vagrancy statutes, and relying upon his opinion in Ricks I ,16

was of the opinion that the latter was unconstitutional.

Considering, very properly, that he was bound by decisions

12Appellant Williams repeated this denial at trial.

13Appellant Williams responded to many of the questions. Appel

lant Ricks refused to answer any at all.

14“ [T]he term ‘narcotic drug user’ shall mean any person who

takes or otherwise uses narcotic drugs, except a person using such

narcotic drug as a result of sickness or accident or injury, and to

whom such narcotic drugs are being furnished, prescribed, or adminis

tered in good faith by a duly licensed physician in the course of his

professional practice.” D.C. Code § 33-416a(b)(2) (1967 ed.).

1SD.C. Code § 33-416a(b)( 1)(A), (C) (1967 ed.).

16District o f Columbia v. Ricks, 94 Wash.L.Rptr. 1269 (1966).

5

of the District of Columbia Court of Appeals to the con

trary,17 he denied the motions, found each appellant guilty,

and sentenced each to a term in jail. The Court of Appeals

affirmed,18 and the importance of the constitutional issues

raised led to allowance of this further appeal. Without

reaching other contentions advanced by appellants, we hold

that the statutory provisions upon which they were con

victed in this case are vague to the point that they contra

vene the Fifth Amendment, and accordingly reverse.

I

We are greeted at the outset with the Government’s pro

test that appellants lack standing to urge the unconstitu

tionality of the narcotic vagrancy statute on its face. The

Government expresses concern that appellants will be per

mitted to “attack the statute on the ground that its language

might permit it to be applied in an unconstitutional manner

to other people in hypothetical situations not involved in

the instant case.” We think it clear, however, that the

Government has misconceived appellants’ point of view. For

this reason, we deem it helpful to mark out the contours of

this litigation, to identify what is involved, and to shape the

issue we are summoned to decide.

Appellants contend that they have been arrested and con

victed for violation of two statutory subsections framed in

language too imprecise to fairly warn them of the conduct

sought to be prohibited.19 Appellants also say that the

ambiguities in these two subsections left police officers free

to charge, and judicial officers free to assess, their guilt

17See Wilson v. United States, 212 A.2d 805 (D.C.App. 1965),

rev’d on other grounds 125 U.S.App.D.C. 87, 366 F.2d 666 (1966);

Rucker v. United States, 212 A.2d 766 (D.C.App. 1965); Brooks v.

United States, 208 A.2d 726, 728 (D.C.App. 1965); Harris v. United

States, 162 A.2d 503, 505 (D.C.Mun.App. 1960); Jenkins v. United

States, 146 A.2d 444, 447 (D.C.Mun.App. 1958).

1&Ricks v. United States, 228 A.2d 316 (D.C.App. 1967).

19See discussion in text infra pt. II.

6

solely on the basis of conjecture.20 Appellants’ complaint is

addressed to the two subsections upon which their convic

tions were rested,21 and to the impact of those subsections

upon them alone.22 Their position is not camouflaged by

makeweight hypotheticals in an effort to induce us to “con

sider every conceivable situation which might possibly arise

in the application of complex and comprehensive legisla

tion,’ 23 nor do they call upon us “to anticipate a question

of constitutional law in advance of the necessity of deciding

it.”24 Appellants, in endeavoring to demonstrate their thesis,

of unconstitutional personal harm, are at liberty to resort

to the linguistic sources of their present legal difficulties.25

II

Proceeding now to the merits, and examining the two

subsections of the narcotic vagrancy law under which appel

lants were convicted, we see the substantial similarity of the

statutory proscriptions which were applied against appellants

in this case and those which in Ricks I we held to be con

stitutionally insufficient.

Subsection (A), upon which the first charge against appel

lants was laid, defines as a vagrant any unemployed narcotic

user or convicted narcotic offender26 without lawful and

20See discussion in text infra pt. II.

21 And we, of course, do not consider the validity of any other

parts of the statute.

22Thus we deem inapposite the proposition, relied on by the

Government, that “one to whom application of a statute is constitu

tional will not be heard to attack the statute on the ground that impli

edly it might be taken as applying to other persons or other situations

in which its application might be unconstitutional.” United States v

Raines, 362 U.S. 17, 21 (1960).

2i Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249, 256 (1953). See also United

States v. Raines, supra note 22, 362 U.S. at 21.

24 United States v. Raines, supra note 22, 362 U.S. at 21.

We distinguish this point from the facet of the Government’s

argument discussed in the text infra at notes 10-15.

26See note 14, supra. Both appellants had previously been con

victed of offenses against the narcotic laws.

7

“visible means of support” who “is found mingling with

others in public or loitering in any . . . public place and

fails to give a good account of himself.”27 The striking

resemblance of this subsection to the invalid Ricks I subsec

tion ( l ) 28 is apparent.

Subsection (C), the statutory predicate for the second

accusation against appellants, extends the vagrant definition

to any narcotic user or convicted narcotic offender29 who

“wanders about in public places at late or unusual hours of

the n ight. . . and fails to give a good account of himself.”30

The close likeness this subsection bears to the infirm Ricks

I subsections (8)31 is manifest.

The same fatal statutory generalities discussed in Ricks

/ —“loitering,”32 failure to give “a good account,”33 “wan

ders,” 34 and without “visible means of support”35—pervade

the enactment under scrutiny,36 without any legislative def

inition whatever. Both of the subsections involved in this

appeal incorporate at least two of them as essential elements

of the crimes of which appellants were found guilty. As

was the situation in Ricks I, there is no body of limiting

judicial construction helpful to the problems presented

here.37

27D.C. Code § 33-416a(b)(A) (1967 ed.).

28Ricks I, supra note 1, at 9-10.

29See note 14, supra.

30D.C. Code § 33-416a(b)(C) (1967 ed.).

31 Ricks I, supra note 1, at 17-18.

32Ricks I, supra note 1, at 9-12.

33Ricks I, supra note 1, at 12-15.

34Ricks I, supra note 1, at 17-18.

35Ricks I, supra note 1, at 17-18.

36Similarly “mingling with others,” even as applied to convicted

offenders, is an expression imprecise in content. Compare Lanzetta v.

New Jersey, 306 U.S. 451, 456-58 (1939). See also Bakery. United

States, 228 A.2d 323 (D.C.App. 1967).

37See Lyons v. United States, 221 A.2d 711, 712 (D.C.App.

1966) (prior knowledge that accused is narcotic user or convicted

8

Thus we cannot find in the statutory language a degree

of specificity that would enable citizens of ordinary intellect

to distinguish wrong from right, or administrators or jurists

to confidently make applications. And like the provisions

involved in Ricks I, those here in issue open the door wide

to convictions on suspicion in lieu of proof of criminality.

A vagrancy conviction is precipitated by the police record

accumulated from vagrancy observations, and the observa

tions enable the building of that record on suspicion alone.

The process is well illustrated by the testimony of the offi

cer who made the first observation of appellant Ricks. She

was selected for a vagrancy observation “ [b]ecause in my

opinion she was involved in some sort of an illegal activity”

which the witness suspected was prostitution. “ [T]he basis

for that suspicion” was that “she’s a known prostitute” and

because the officer twice saw her leave the carry-out with

different men and return shortly thereafter. Admittedly

these circumstances created no ground for a prostitution

arrest, but they “did justify . . . making an observation on

her as a vagrant.” So, as the officer further admitted, “the

reason that she was singled out from among the other peo

ple on the street derives from the fact that [the officer]

had suspicions of her regarding illegal conduct that [he] did

not have regarding other people on the street.”

Although appellants were arrested for and convicted of

narcotic vagrancy, the Government conceded at trial that at

no time were they found in the possession of narcotic drugs.

While needle marks were seen on their arms when inspected

at the observations, the evidence would not sustain the con

clusion that they connoted present, as distinguished from

possibly recent, narcotic use. The testimony discloses, too,

that if the observing officers had had reasonable cause to

believe that appellants were then in violation of the narcotic

narcotic offender is prerequisite to narcotic vagrancy arrest); Jenkins

v. United States, supra note 17, 146 A.2d at 446 (statute applies even

though defendant did not know his associates were drug users and

convicted narcotic offenders).

9

laws, they would have been arrested for such violations

rather than made the subjects of vagrancy observations.

More broadly, if there had been grounds for arrest for any

kind of criminal conduct, the arrest would have superceded

the observation. Thus, as one officer put it, when you

“suspect” a person “of some form of crime,” a narcotic

vagrancy observation is “sort of something you do instead

of making an arrest.”

A basic suspicion underlying narcotic vagrancy enforce

ment, the testimony further disclosed, is that “sometimes”

when addicts are on the streets they “may” be plotting

crime. This was vividly confirmed by the prosecutor in

colloquy with the judge at trial:

“THE COURT: . . . What are these people doing in your

view when they are loitering or mingling and failing to

give a good account of themselves? . . . What are they

doing that is harmful to the public? What is the stat

ute addressed to?

“ [THE PROSECUTOR]: They are . . . in a position where

from their way of life there is a real danger that they

will commit some other crime, not this particular crime

[narcotics vagrancy], but some other crime.

“THE COURT: So, we suspect that because of what they

are doing here, they might well engage in criminal con

duct? Is that what it comes down to?

“ [THE PROSECUTOR]: That is correct.

“THE COURT: And you think that under our system

you can have a statute which essentially proceeds on

the principle that because the police officer or prosecu

tor or a court suspects that because of presence or

activity or whatever, a person may commit an offense,

that that in itself may be made a crime?

“ [THE PROSECUTOR]: Absolutely.”

As Ricks I forecasts, we do not agree with the prosecu

tor.38 And it is evident from our exposition in Ricks I that,

unless somehow otherwise saved, we must hold that both of

the subsections underpinning appellants’ convictions fall

38Ricks I, supra note 1, at 10-12.

10

short of the constitutional dictate that criminal conduct be

defined with reasonable certainty.39

Ill

The Government would find the antidote for the ills

plaguing the narcotic vagrancy statute in the mode of its

accustomed administration. Bypassing the statutory language

in favor of its particular application to appellants, the Govern

ment endeavors to construct a more palatable decisional

context for the vagueness problem. Appellants were narcotic

users, it points out, who loitered nightly with other narcotic

users in a block where narcotic traffic was dense. It is only

in a “pocket of narcotic activity,” it asserts, that police

officers invoke the statute. These pockets are said to be

the points at which addicts congregate while awaiting a

“connection”—a contact with a peddler of narcotic drugs;

these circumstances of “sinister significance,” it is claimed,

warrant vagrancy observations and justify a “good account”

on pain of ultimate arrest. An enforcement policy so

limited as to area, subjects and purposes, the Government

urges, brings the statute in line with the Constitution.

We cannot accept this argument. To begin with, the rec

ord does not adequately sustain the Government’s factual

premises. Narcotic vagrancy enforcement, the record shows,

is stepped up in four precincts in the District of Columbia

where the police consider the incidence of vice to be particu

larly high.40 Officers specializing in the suppression of

drug traffic bear down in these sections of the city.41 The

39Ricks I, supra note 1, at 6-9.

40This is based on a belief that these precincts embrace areas

prone to illegality, but yet a belief not based on facts rising to the

dignity of probable cause. Suspect establishments thus continue to

operate, but residents of these neighborhoods who are thought to be

frequenting them are observed, arrested and convicted for vagrancy.

41 We have frequently noted that the police constantly receive

complaints of narcotic activity in certain areas of the city. See Dorsey

v. United States, 125 U.S.App.D.C. 355, 356, 372 F.2d 928, 929

(1967); Hutcherson v. United States, 120 U.S.App.D.C. 274, 281, 345

11

testimony describing the 1200 block of Seventh Street,

Northwest, made out plainly enough its unwholesome char

acteristics,42 but hardly the “pocket of narcotic activity” the

Government tries to picture.

While suspected narcotic users frequented the block, the

record is bare of evidence that sales of narcotic drugs

occurred there. While reputed narcotic users and prostitutes

were familiar characters in the testimony recounting the

observations in this case, the dealer in narcotics was totally

absent. The observations themselves—particularly those on

appellant Ricks, which smack of surveillance for prostitu

tion—are devoid of the “sinister significance” of trafficking

in drugs. While the 1200 block may have been one of the

police department’s favorite targets, there is nothing to sug

gest that it was driven home to the citizenry that conduct

unmolested in the city generally43 would become criminal in

that block by reason of concentrated narcotic vagrancy

enforcement there.

Moreover, error in the Government’s legal thesis mounts

with the Government’s increase in overstatement of pertinent

doctrine. We are not at liberty to ignore the shortcomings

of the statutory language, or rationalize its validity, simply

on the basis of the methods associated with its administra

tion. “ [A] statute attacked as vague must initially be

examined ‘on its face,’ ”44 and many times the inquiry need

F.2d 964, 971, cert, denied 382 U.S. 894 (1965); Freeman v. United

States, 116 U.S.App.D.C. 213, 214, 215, 322 F.2d 426, 427, 428

(1963).

42At the time of appellants’ arrests, the 1200 block of Seventh

Street, Northwest, was lined by two-story buildings with stores on the

street floors and rooming houses on the upper floors. In the testimony,

the block was described as “an area frequented by known and con

victed con artists, [and] known and convicted narcotic violators,”

and the rooms as “dens of vice” for “the prostitutes and the junkies

and the con artists, to perform their trades.”

43By reason of general non-enforcement of the narcotic vagrancy

statute.

44United States v. National Dairy Corp., 372 U.S. 29, 32 (1963).

12

extend but little further.45 The sine qua non of constitu

tional certainty in the definition of crime is fair warning of

the statutory prohibitions to those of ordinary intelligence-

notice of the proscribed activities which is reasonable when

gauged by common understanding and experience.46 But “it

does not follow that a readily discernible dividing line can

always be drawn, with statutes falling neatly into one of

the two categories of ‘valid’ or ‘invalid’ solely on the basis

of such an examination,”47 so that “ [i]n determining the

sufficiency of the notice a statute must of necessity be

examined in the light of the conduct with which the defend

ant is charged.”48

Thus a statute making unlawful sales at “unreasonably

low prices for the purpose of destroying competition or

eliminating a competitor” may adequately admonish that

sales made below cost with that intent fall under the ban.49

Similarly, a statutory prohibition on demonstrations “near”

a courthouse, despite its ambiguity in other contexts, may

convey an exhortation against “a demonstration within the

sight and hearing of those in the courthouse.”50 In these

illustrative situations, criminal statutes that might have been

plainer were applied to the infringing conduct of those who

should have known better, and were left none the worse off

by the lack of further elucidation. But “ [t ]his is not to say

that a bead-sight indictment can correct a blunderbuss stat

45See, e.g.. Giacco v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399, 403 (1966);

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284, 293 (1963); Lametta v. New Jersey,

supra note 36, 306 U.S. at 453-58; Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274

U.S. 445, 453-57 (1927); Connally v. General Constr. Co., 269 U.S.

385, 393-95 (1926); United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U S

81, 89 (1921).

46 Ricks I, supra note 1, at 6-8.

47 United States v. National Dairy Corp., supra note 44, 372 U S

at 32.

4SId. at 33.

49Id. at 34.

50Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559, 568-69 (1965).

13

ute, for the latter itself must be sufficiently focused to

forewarn of both its reach and coverage.”51

We have before us a blunderbuss statute without a bead-

sight enforcement policy. Since nothing in the police

department’s administrative practices gave the advance

warnings which the statute omitted, those practices could

not in any event supply the constitutional deficiencies.

Moreover, the statute before us does not afford reasonable

warning as to the activities it undertakes to make criminal.

In Lanzetta v. New Jersey,52 the Supreme Court held that

an unconstitutionally vague statute could not be saved by

definition in the indictment “ [ i] f on its face the challenged

provision is repugnant to the due process clause, specifica

tion of details of the offense intended to be charged would

not serve to validate it,”53 for “ [i]t is the statute, not the

accusation under it, that prescribes the rule to govern con

duct and warns against transgression.” 54 For similar reasons,

the narcotic vagrancy statute, so indistinct from overbreadth,

cannot be cut down to constitutional size by the unpubli

cized scope limitations which its enforcement plan espouses.55

51 United States v. National Dairy Corp., supra note 44, 372 U.S.

at 33.

52Supra note 36.

53Id. at 453.

54 Id.

ssCompare United States v. Five Gambling Devices, 346 U.S. 441

(1953), involving a statute prohibiting transportation of “any gambling

device” in interstate commerce, and requiring “every . . . dealer” in

such devices to register with the Attorney General “the addresses of

his places of business in such district” and to report to the Attorney

General all sales and deliveries of gambling devices “for the place or

places of business in the district.” Indictments against two dealers,

and a libel to forfeit five gambling machines, for violation of the regis

tration and reporting requirements failed to allege that any gambling

devices had moved in interstate commerce. Judgments dismissing the

indictments and libel were affirmed. Three justices joined in an opin

ion expressing the view that the statute, as a matter of construction,

did not sustain the indictments and libel. Id. at 442-52. Justices

14

The flow and use of narcotic drugs in the Nation’s Capital

presents a critical social problem of monumental dimensions,

and the need for effective legislative curbs is great. But as

we pointed out in Ricks I, even desirable goals “cannot be

achieved through techniques that trample on constitutional

rights.”56 In disposing of this appeal, we do not enter the

debate as to whether the narcotic vagrancy statute fulfils its

intended mission.57 What is clear to us, and what we hold,

Black and Douglas, in a concurring opinion, delineated the position

that the registration and reporting requirements were unconstitution

ally vague. “ [T]he use of the phrase ‘such district’ is bound to leave

a dealer bewildered. Does the phrase refer to the place where a dealer

is compelled to file his papers? Or does it simply force him to tell in

what ‘district’ he maintains ‘places’? If a dealer is able to solve this puz

zle, how is he to find ‘such district’? The Act gives no hint as to

where the ‘district’ is or how a person can locate it. It never

describes any ‘district.’ ” Id. at 453.

We focus on the concurring opinion primarily for what it says with

respect to an administrative effort to rectify the statutory ambiguities.

The Attorney General promulgated a regulation which clarified the

matter, but the two concurring justices deemed it inefficacious for

that purpose. “Nor can a criminal statute too vague to be constitu

tionally valid be saved by additions made to it by the Attorney Gen

eral. Of course, Congress could have prescribed that reports should

be made at reasonably accessible places designated by the Attorney

General. . . . But the Act under consideration did not do this.” Id. at

453. Moreover, the statute upon which the Attorney General drew

for authority to issue the clarifying regulation did not “support the

Attorney General’s attempt to infuse life into an Act of Congress

unenforceable for vagueness. The vital omission in this criminal stat

ute can be supplied by the legislative branch of government, not by

the Attorney General.” Id. at 453-54.

56Ricks I, supra note 1, at 22. Compare Lanzetta v. New Jersey,

supra note 36, 306 U.S. at 453-58 (statute banning gangsterism held

void for vagueness); Bolin v. State, 266 Ala. 256, 96 So.2d 582,

583-86 (1957) (statute denouncing possession of ingredients for mak

ing tear gas bombs held void for vagueness); Hanell v. Texas, 166

Tex.Cr.App. 384, 314 S.W.2d 590, 592 (1958) (statute prohibiting

possession and delivery of narcotics held void for vagueness).

57“Aside from its legal vulnerability, the law appears to have mini

mal law enforcement value, no treatment orientation and a potential

15

is that the subsections impugned in this case cannot con

tribute to that end consistently with the Constitution.

We reverse the judgment of the District of Columbia

Court of Appeals with direction to remand the case to the

District of Columbia Court of General Sessions for dismissal

of the informations.

Reversed.

for harassment of addicts dependent on their status alone. Construed

literally, the statute might forbid gatherings of narcotic addicts for

self-help in group therapy or Narcotics Anonymous meetings. Although

it allows medical or psychiatric treatment as sentencing alternatives,

these devices have not in fact been used to secure help for the addict.

We believe that any preventive aspects of the law would be better

achieved through a comprehensive drug treatment program and a more

rational application of the District’s civil commitment law to compel

known addicts to submit to treatment in appropriate cases. The

Commission therefore recommends repeal of the Narcotics Vagrancy

Act.” Report o f the President’s Comm’n on Crime in the District o f

Columbia 580 (1966).

Administrative Office, U.S. Courts - T H IE L P R E SS - Washington, D. C.