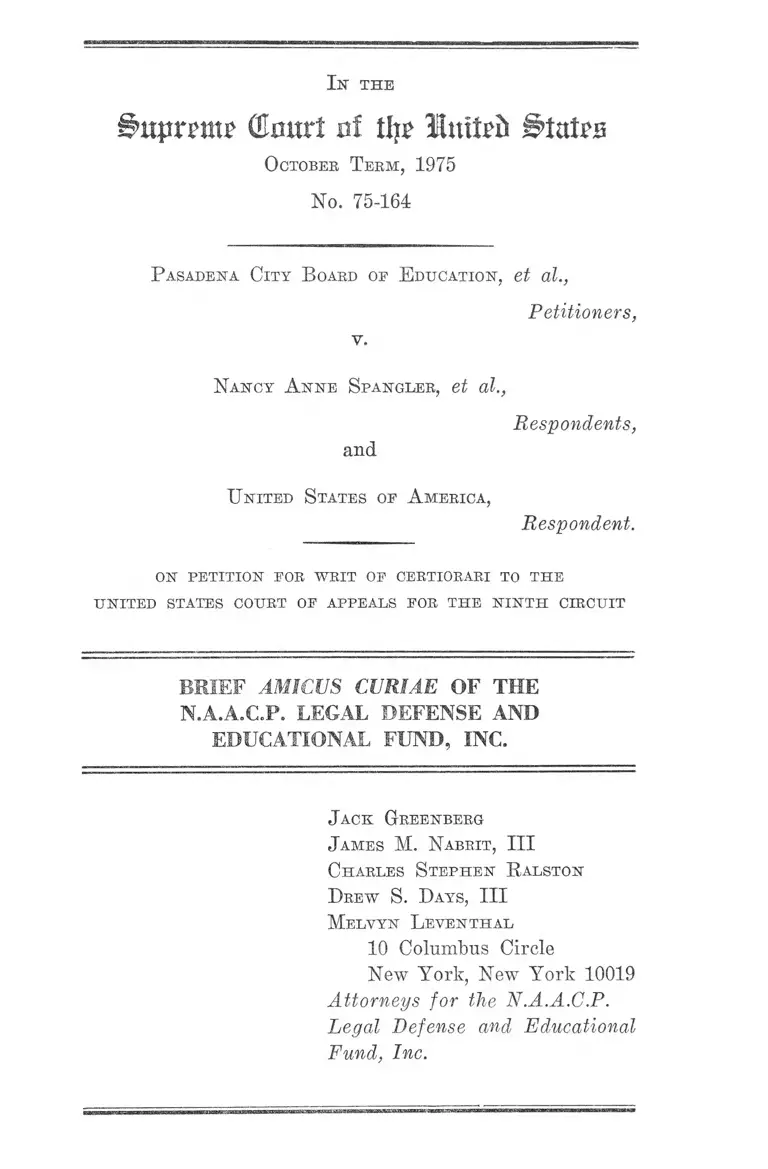

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler Brief Amicus Curiae, 1975. bc71fd93-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b9fdf636-03d7-4dee-809f-d392d2888a8d/pasadena-city-board-of-education-v-spangler-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme (Emtrt cf tl ̂ luifrii

O ctober T erm , 1975

No. 75-164

I n th e

P asadena City B oard of E ducation, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

Nancy A nne Spangler, et al.,

and

U nited States oe A merica,

Respondents,

Respondent.

on petition for writ of certiorari to the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen R alston

D rew S. D ays, III

Melvyn L eyenthal

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P.

Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of Amicus

Argument ....... ......

C onclusion .............

A ppendix A ..........

A ppendix B ....... .

PAGE

1

4

17

la

5a

T able op A uthorities

Cases

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

TT.S. 19 (1969) ............. ...... ........... .................................. 2

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 TT.S. 294 (1955) ....... 2

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 TT.S. 483 (1954) 2, 4, 5,15

Cooper y. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ................................... 2

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ..... ........................... ................... ..... 2

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) .......................................... 2

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 444 F.2d 1400

(5th Cir. 1971) ....... ........................................................... 5

Swann v. Charlotte-MecJdenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............................ ..... 2,3,5,6,14,15,17

Swann v. Charlotte-MecJdenburg Bd. of Ed. No. 1974

(W.D.N.C. July 11, 1975) .......................................... 14,16

11

PAGE

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 501 F.2d

383 ( lth. Cir. 1974) .......... - ................ .................... ........ 13

Swann v. Charlott e-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 379 F.

Supp. 1102 (W.D.N.C. 1974) ...... ........................13,14,16

Swann v. Charlott e-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 362 F.

Supp. 1223, appeal dismissed, 489 F.2d 966 (4th Cir.

1974) ........................ .......................................-.11,12,13,15

Sivann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 334 F.

Supp. 623 (W.D.N.C. 1971) ......... ................. ............. ..9,10

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 328 F.

Supp. 1346, Aff'cl 453 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972) ....... 7, 8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 311 F.

Supp. 265 (W.D.N.C. 1970) .......................................... 8

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction, 448 F,2d

770 (5th Cir. 1971) 5

In th e

i>uprmp (Eoart of tlj? iUttfpii

October T erm , 1975

No. 75-164

P asadena City B oard oe E ducation, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Nancy A nne Spangler, et al.,

and

Respondents,

U nited States oe A merica,

Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OE CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OE APPEAJLS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Interest of Amicus*

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorporated under the

laws of the State of New York to assist blacks to secure

their constitutional rights through the courts. Its charter

declares that its purposes include rendering legal aid

* Letters of Consent from counsel for the petitioners and respon

dents in this case have been filed with the clerk of the Court.

2

gratuitously to blacks suffering injustice by reason of race

who are unable, on account of poverty, to employ legal

counsel on their own behalf. The charter was approved

by a New York court, authorizing the organization to serve

as a legal aid society. The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense Fund,

Inc., is independent of other organizations and is supported

by contributions from the public. For many years its at

torneys have represented parties in this Court and the

lower courts, and it has participated as amicus curiae in

this Court and other courts.

Attorneys from the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund, Inc. litigated before this Court the land

mark case of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) which declared unconstitutional state-imposed seg

regation of the races in public education. Since Brown,

its attorneys have been actively involved in litigation de

signed to ensure that the mandate of that decision was

properly and effectively implemented by lower federal

courts. In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Edu

cation, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), a case also handled by Legal

Defense Fund attorneys, this Court attempted to provide

guidance to lower federal courts and school boards with

respect to the nature and degree of desegregation required

by Brown, nearly seventeen years after that decision be

came the law of the land.1 It was clearly this Court’s hope

that segregated school systems would proceed with the

job of converting to unitary status. Thereafter, federal

courts could turn their limited resources to other important

1 Between Brown and Swann, Legal Defense Fund attorneys

argued the following desegregation eases, among other's, before this

Court: Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ; Cooper

v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958); Griffin v. County School Board of

Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ; Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430' (1968) ; and

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U S 19

(1969).

3

matters, leaving school hoards with full authority to man

age their educational programs free of judicial interven

tion or supervision.

In this litigation, the Court is faced for the first time

with the task of construing language in Swann relating to

the circumstances under which federal court jurisdiction

over a desegregation case may appropriately be ended. In

that regard, Swann stated:

At some point, these school authorities and others like

them should have achieved full compliance with this

Court’s decision in Brown I. The systems would then

be “unitary” in the sense required by our decisions

in Green and Alexander.

It does not follow that the communities served by

such systems will remain demographically stable, for

in a growing, mobile society, few will do so. Neither

school authorities nor district courts are constitution

ally required to make year-by-year adjustments of the

racial composition of student bodies once the affirm

ative duty to desegregate has been accomplished and

racial discrimination through official action is elimi

nated from the system. This does not mean that federal

courts are without power to deal with future problems ;

but in the absence of a showing that either the school

authorities or some other agency of the State has

deliberately attempted to fix or alter demographic

patterns to affect the racial composition of the schools,

further intervention by a district court should not be

necessary. 402 U.S. 1, at 31-32'.

Based upon the extensive involvement of Fund attorneys

in school desegregation cases over the years, we submit

that this Court’s decision in Swann has been a significant,

positive force in increasing the pace and improving the

4

quality of efforts to dismantle dual systems of public edu

cation. But, meaningful changes brought about by Swann

did not happen overnight. Since 1971, lower federal courts,

with few exceptions, have been required to exercise close

and continuing supervision of various systems to ensure

that acceptable desegregation plans would be devised and

effectively implemented.

In some situations, many of which are handled by Legal

Defense Fund attorneys, court supervision is still neces

sary. This brief is being filed to bring to the Court’s

attention considerations which warrant application of a

realistic standard for determining whether lower federal

courts have properly decided to retain jurisdiction over

desegregation cases.

Argument

Almost seventeen years passed after Brown before ex

tensive compliance got underway. Given this history of

resistance it is not surprising that court efforts to secure

compliance with Swann have encountered more than a little

difficulty. In some systems, boards resisted assuming re

sponsibility for devising plans that achieved the “greatest

possible degree of desegregation;” other devised plans

that appeared on paper to have prospects for eradicating

segregation but proved ineffective. Yet others have imple

mented generally acceptable desegregation plans that have

required minor adjustments after implementation to ensure

continued effectiveness. In each case, successful desegre

gation has depended largely upon the extent to which the

lower federal courts have faithfully discharged the crucial

supervisory roles this Court defined in Swann. Where

courts have insisted that boards produce desegregation

plans that worked and worked realistically “now,” and have

required boards to make adjustments to avoid foreseeable

5

resegregation, stable desegregated systems have resulted.

Where courts have accepted “ paper compliance” and

resisted the duty to review how so-called unitary plans

operated in practice, unstable, resegregated and dislocated

systems have developed. In the former situations, courts

have been able to get out of the desegregation business;

in the latter, litigation persists. As the Fifth Circuit Court

of Appeals pointed out, “one swallow does not make a

spring.” Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 444 F.2d

1400, 1401 (5th Cir. 1971): even under the best of circum

stances, district courts should observe the operation of a

desegregation plan in practice for a few years before

declaring a system unitary.2

Here, the Pasadena City Board of Education asserts

that it has dismantled its dual system and should be freed

from further judicial supervision. Alternatively, it argues

that continuing supervision does not justify its being pro

hibited from instituting a new student assignment plan

which it regards as educationally superior to one previously

approved by court order. The respondents contend that

the Pasadena Board has not entirely satisfied the require

ments of Brown and Swann and that the proposed new

plan would resegregate, not further desegregate, the Pasa

dena system. Both the district court and the court of

appeals below have agreed that continuing supervision is

required and that the Board’s new proposal would not

advance desegregation. Presented for this Court’s reso

2 In fact, the Fifth Circuit, after Swann, established a circuit-

wide rule that district courts should retain jurisdiction of desegre

gation cases where terminal plans had been implemented for “not

less than three school years,” during which time affected school

boards must file semi-annual reports on such things as pupil and

teacher assignments, proposed construction, transportation and

student transfers. At the end of the three-year period, dismissal

may be granted only after plaintiffs have received notice and the

opportunity to be heard. Youngblood V. Board of Public Instruc

tion, 448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971).

6

lution, therefore, is the question of whether the lower

courts abused their discretion and acted contrary to Swann

by determining that continued supervision of the Pasadena

system was necessary under the circumstances.

We submit that the Court would be aided in deciding

this case by the example of the Swann case itself, where

active, close, sensitive, yet resolute, lower federal court

supervision successfully moved a dual system to the point

of stable desegregation, warranting an end to judicial

intervention. By assessing the facts which the district court

addressed in achieving compliance in Swann, this Court

may perceive the Pasadena case in a useful perspective.

On May 6, 1971, plaintiffs in Swann filed a motion for

further relief in the trial court seeking an order 1) requir

ing the defendant Board to comply with previous desegre

gation orders and 2) enjoining the Board from proceeding

with any school construction, additions, or abandonments

without judicial approval. On June 17 and 18, 1971, the

district court held hearings with respect to a Board pro

posal to alter the Charlotte-Mecklenburg desegregation

plan (the “Finger Plan” ) upheld by this Court in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971). These “partly formed proposals” involved the fol

lowing notable changes: 1) closing two formerly black

schools; 2) utilizing a formerly high school; 3) reducing

the capacity of 15 formerly black elementaries; 4) convert

ing 9 of these 15 elementaries to sixth grade centers; 5)

employing “ one-way” busing of blacks to formerly all-

white schools; 6) increasing the number of vacant class

rooms in the system; and 7) increasing the busing times

and distances particularly for black children. The Court’s

response, in its memorandum of June 22, 1971 was :

[WJhen the plan is studied in depth and its purposes

and results emerge through its statistics, it becomes

7

apparent that it seeks to raise issues which were de

cided two years ago; that it is regressive and unstable

in nature and results; that it would retreat from ap

proved arrangements and put the burdens of desegre

gation primarily upon the black race; that it would

unlawfully discriminate against black children; that

its methods are discriminatory; and that it should not

be approved. Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 328 F..Supp. 1346, at 1350 (W.D.N.C.

1971)

The court, noting that “ ‘white flight’ was advanced as the

chief reason for the board’s proposals,” concluded that it

was not a “ serious threat to the public schools of Mecklen

burg.” Id. at 1352. In response, the Board withdrew its

proposals and promised to present revised suggestions

within a few days. The revised proposals, a “feeder plan,”

envisioned the closing of one black school (Double Oaks)

and the use of two others (Villa Heights and University

Park) as sixth grade centers. In its order of .June 29, 1971,

the court found no valid, non-racial reasons for these

proposals. The court decided, however, to allow the Board

the option of implementing its feeder plan, as long as

Double Oaks was not closed and Villa Heights and Uni

versity Park were used to capacity, or of continuing to

utilize the “ Finger Plan.” In any event, the court ruled

that:

The defendants are enjoined and restrained from

operating any school for any portion of a school year

with a predominantly black student body. The move

ment of children from one place to another within the

community and the movement of children into the

community are not within the control o f the school

board. The assignment of those children to particular

8

schools is within the total control of the school board.

The defendants are therefore restrained from assign

ing a child to a school or allowing a child to go to a

school other than the one he was attending at the

start of the school year, if the cumulative result of

such assignment in any given period tends substan

tially to restore or to increase the degree of segrega

tion in either the transferor or the transferee school.3

32S F.Supp. at 1349-50.

On an appeal to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals of

this decision by the Board, the district court was unani

mously affirmed, en banc. Swann v. Charlotte-MecMenburg

Board of Education, 453 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972).

On August 27, 1971, plaintiffs filed a motion for further

relief alleging as grounds for court action as follows:

At the board meeting on April 24, 1971, the board dis

regarded its conditional transfer provision for senior

high school students and transferred all senior high

school students who had indicated a desire to transfer

to another school. This has resulted in resegregation

of West Charlotte High School, the previously all black

school, and has substantially reduced the number of

students assigned to that school for the 1971-72 school

year. Additionally, the board has permitted transfers

of students in other grades in a way which has pro

moted resegregation of schools. The board has also

failed to determine the correct addresses of students

and has thereby permitted the assignment of many

students to schools other than the ones they were to

3 This order merely restated an earlier requirement with respect

to the Board’s duty to prevent the creation of all-black or pre

dominantly black schools, approved by this Court. See 311 F.Supp.

265, 268 (W.D.N.C. 1970).

9

attend under the Board’s proposed Feeder plan. This

is [sic] further tended to resegregate the schools.

[and]

Since the Court’s June 29, 1971 order, the board has

made numerous changes in the proposed Feeder Plan

it previously submitted to the Court. The board has

not filed copies of these changes with the court or

served copies of same upon counsel for the plaintiffs,

(pp. 2-3)

After a hearing conducted on September 22, 1971 with

respect to these allegations, the court found on October 21,

1971, that “ several highly specific official actions of the

school board itself since the April, 1971 decision of the

Supreme Court have added new official pressures which

tend to restore segregation in certain schools.” 334 F.Supp.

623, at 628 (W.D.N.C. 1971). It identified these pressures

as stemming from 1) the construction program (use and

location of mobile units), 2) the under population and pro

posed closing of formerly black schools, and 3) several

recent decisions about pupil assignments and transfers.

The court pointed out that the current plan contemplated

the use of 232 mobile units, primarily at suburban schools

remote from the black community, that black schools were

being operated at considerably less than capacity, that low-

and middle-income white children were being assigned to

and wealthier white children removed from formerly black

schools and that the Board had allowed numbers of white

children to abandon and black children to return to for

merly black schools in violation of existing court orders.

Id. at 628. The court indicated moreover that:

With that history in view, it is necessary to inquire

into the board’s present plan or program for dealing

10

with foreseeable problems of re-segregation in response

to the pressures which have been mentioned in this

order. If the board has a program or policy to deal

with the results of these pressures, the schools can

nevertheless be operated in compliance with the law.

If it has no plan, many of the schools are likely to

re-segregate.

There is no such plan and no such program.

On the issue of “ resegregation” of certain formerly all

black elementaries under the feeder plan, the court pointed

out that this result was caused by the Board’s failure to

make allowance for the 1,500 westside, low-cost, principally

black housing units which were currently being completed

or occupied. It concluded:

Racial discrimination through official action has not

ended when a school board knowingly adopts a plan

likely to cause a return to segregated schools and then

refuses to guard against such resegregation.

It is therefore apparent that although the current

plan as now working should be approved, the case will

have to be kept active for a while longer. Id. at 629.

Plaintiffs’ motion for further relief was denied by the

court.

On November 7, 1972, plaintiffs filed a motion for fur

ther relief seeking an order:

. . . directing the defendants to take immediate steps

to eliminate the continued racial identity of West

Charlotte Senior High School and continued racial

discrimination with respect to professional personnel

(p. 1).

11

On April 2, 1973, plaintiffs filed a motion to add addi

tional parties defendants—new board members and white

plaintiffs in a new suit. Plaintiffs alleged that:

The Board has failed to comply with the Court order.

Several schools have now or are becoming resegre

gated because of the Board’s plan and the Board’s

failure “ to adopt and implement a continuing pro

gram . . . of assigning pupils . . . for the conscious

purpose of maintaining each school . . . in a condi

tion of desegregation.”

At a May 8, 1973 hearing, the Board proposed what the

court described as a “ ‘bare minimum’ or ‘get by’ ” group

of changes. The court suggested that it would be wise

for the Board to develop a more comprehensive revision

for 1974-75 implementation, and directed that certain

changes be made in its plan for 1973-74. On May 18, the

Board returned to court with these 1973-74 revision.

In its order of June 19, 1973, the court approved modifi

cations for the 1973-74 academic year but required the

Board to prepare by March 1, 1974 a comprehensive plan

for “pupil assignment and desegregated school operation”

to be implemented at the start of the 1974-75 school year.

Though the court found that much genuine progress was

promised by current Board proposals, it concluded that

they did “not yet satisfy the constitutional requirements

of equal protection of the laws (fairness)” and that con

tinuing jurisdiction was still required.

Of particular relevance to the issues in the Pasadena

case before the Court is the court’s analysis of the rela

tionship between pupil assignments and so-called “white

flight” within the Charlotte-Mecklenburg system:

Defendants proposed to increase the West Charlotte

studenty body by transferring to West Charlotte 180

white and 100 black students from the Statesville

12

Road (North High School) area and 350 white and

125 black students from the Devonshire (Independence

High School) area . . .

The problem with the proposal is not with its numer

ical results, but with its fairness and stability.

# # #

The sore spot may not really be the assignment to a

school eight or ten miles away (high school students

usually have to travel quite a ways to school); nor,

it is to be hoped, is it the educational shortcomings of

West Charlotte; West Charlotte is not expected to

suffer any deficiency of academic offerings nor extra

curricular activities in the future. Rather, the sore

spot with the people of Devonshire and elsewhere in

the Garinger-North-West Charlotte-Harding area is

that people in the southeast part of the county, in

cluding many who live closer to West Charlotte High

School than Devonshire, are not being required to at

tend a “black” school at any time during their high

school career (nor, as a practical matter, for more

than a year or two at any stage of their education).

I f the assignments were done in fairness instead of

in such a way that they effectively re-zone real estate

and drastically affect land values, most, but of course

not all of the valid objections would be reduced or

eliminated.

Significantly, the Pupil Assignment Study (p. 10)4

reports that “ the assignment plan has had greater

and more immediate effect on housing in Charlotte

than on the schools.”

A fair plan would not have such effects.

362 F. Supp. 1223 at 1235-36. (W.D.N.C. 1973).

4 This study was done in March, 1973 by Board staff.

13

The Board’s appeal of this June 19, 1973 district court

opinion and order was dismissed on January 15, 1974 by

the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, sitting en banc.

Sivann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg, 489 F.2d 966 (4th Cir.

1974).5

On July 10, 1974, the Board submitted to the court a

comprehensive desegregation plan for Charlotte-Mecklen

burg schools to be implemented for the 1974-75 academic

year. In approving this plan by order of July 30, 1974,

the district court remarked as follows:

Adoption of these new guidelines and policies is un

derstood as a clean break with the essentially “ reluc

tant” attitude which dominated Board actions for

many years. The new guidelines and policies appear

to reflect a growing community realization that equal

protection of laws in public education is the concern

of private citizens and local officials and is not the

private problem of courts, federal or otherwise. This

court welcomes the new guidelines and policies and

the new plan, and the declared intention of the new

Board to carry them out. If implemented according

to their stated principles, they will produce a “unitary”

(whatever that is) school system. 379 F. Supp. 1102,

1103 (W.D.N.C. 1974).

The court noted that the comprehensive plan would in

clude the following features, among others (1104-05):

1) Transfer policies and procedures for the purpose of

maintaining an integrated school system with a

stable assignment program;

B On December 10, 1973, the district court enjoined certain white

parents from prosecuting a state action which challenged the

Board’s decision to increase black participation in a program for

talented students. The Court of Appeals affirmed this ruling on

July 23, 1974. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 501 F.2d 383 (4th Cir. 1974).

14

2) Distances of bus travel have been somewhat reduced;

years of bussing for many children have been re

duced; and the burdens of bussing have been more

equally, though of course not perfectly, redistributed;

3) Monitoring procedures to prevent adverse trends in

racial make-up of schools are promised ; and

4) School location, construction and closing are to be

planned to simplify rather than, to complicate de

segregation.6

On July 11, 1975, the United States District Court for

the Western District of North Carolina closed its files on

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, Civil

No. 1974, with the following words:

Dismissal is neither usual nor correct in a case like

this where continuing injunctive or mandatory relief

has been required. Pacts and issues once decided on

their merits ought, generally, to remain decided. This

case contains many orders of continuing effect, and

could be re-opened upon proper showing that those

orders are not being observed. The court does not

anticipate any action by the defendants to justify a

re-opening; does not anticipate any motion by plain

tiffs to re-open; and does not intend lightly to grant

any such motion if made. This order intends therefore

to close the file; to leave the constitutional operation

of the schools to the Board, which assumed that bur

den after the latest election; and to express again a

deep appreciation to the Board members, community

leaders, school administrators, teachers and parents

wdio have made it possible to end this litigation. (Slip

op. at 1-2)

6 In Swann, this Court emphasized the important role that school

board decisions with respect to construction of new schools and the

closing of old ones play in determining whether a system remains

desegregated or resegregates. Id. at 20.

15

A copy of this entire “ Swan Song,” as the district court

characterized its final order, is included in Appendix A

hereto.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg experience described above

demonstrates several important points about the appro

priate nature, extent and duration of federal court super

vision of so-called “unitary” systems.7 First, even the best

desegregation plan on paper may require extensive revi

sions and modifications in practice. An entirely new plan

may be necessary where original proposals for desegrega

tion have proved unworkable and ineffective. Second, a

desegregation plan will be effective only if the school board

wants it to work.. Even in the absence of actual bad faith,

the oversight of a district court is crucial to ensure that

disregard for the segregative consequences of board conduct

will not go uncorrected. Third, plans which place the

burden of desegregation upon blacks and low- and middle-

income whites, while leaving “protectorates” of wealthier

whites untouched, have produced resistance, instability and

“white flight.” “ Fair” plans may be expected to have the

opposite effect. Fourth, the key to a successful plan, which

a court can expect with confidence to effect compliance

with Brown and Swann in the long run without judicial

supervision, is a school board that accepts affirmative con

stitutional responsibility to establish and maintain a de

segregated system. Compare the ways in which the court

described the two Charlotte-Mecklenburg boards in office

between April, 1971 and July, 1975. In passing upon the

1973 Board’s proposals for 1973-74, the court remarked:

Until now, defendants had taken no initiative whatever

in coping with problems of desegregation; their

7 Charlotte-Meeklenburg’s history is not unique. In Appendix

B, hereto, we have listed from the Legal Defense Fund’s docket 31

case's in 12 states where significant litigation occurred after Swann.

These cases have also either been dismissed or are inactive, subject

to montoring through periodic reports filed by affected school

boards.

16

actions have awaited court orders or instructions, and

have been based on minimum interpretation of what

compliance would require. 362 F.Supp. 1223, at 1236-37.

In its order dismissing the case, the court referred to the

Board now in office in the following manner:

Since early 1974, the case has been quiet. No new or

old issues have been raised by the litigants or decided

by the court. The new Board has taken a more positive

attitude toward desegregation and has at last openly

supported affirmative action to cope with recurrent

racial problems in pupil assignment. Though con

tinuing problems remain, as hangovers from previous

active discrimination, defendants are actively and in

telligently addressing these problems without court

intervention. It is time, in the tenor of the previous

order, to be “closing the suit as an active matter of

litigation . . . ”

The lesson of Charlotte-Mecklenburg then, for purposes

of this Court’s determination of the issues raised in the

Pasadena case, is that in moving a segregated school system

to unitary status:

The attitude or state of mind at the top, among the

Board of Education, is far more important than the

physical details or logistics of pupil assignment. If

that attitude or policy is negative or technical, the

children know it and feel i t ; then “ ratios” and “bussing”

assume unwanted but unavoidable significance. On the

other hand, if the top level attitude or policy is equal

treatment for all, the word gets around; hackles fall;

litigants and lawyers and courts get easier to please;

and the details of pupil assignment become less con

troversial and more commonplace.

17

And tile recurrent injury to the spirits and motivation

of the children themselves—as well as the unrest

among parents—can be alleviated. 379 F.Supp. at 1104.

In Pasadena, the petitioner school board has shown

hostility to making desegregation work, a commitment to

doing the very minimum to comply with court orders, and

a desire to replace the current plan with an approach that

offers strong possibilities for resegregating the system.

Under such circumstances, the trial and appellate courts

were correct in determining that continuing judicial super

vision of the Pasadena system was necessary and proper.

Until the Pasadena board demonstrates that it has the

commitment to make desegregation work, an appraisal

the trial court is uniquely qualified to make, Swann vali

dates an exercise of discretion which determines that

judicial supervision should continue.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decisions below should

be affirmed by this Court.

Bespectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabbit, III

Charles S tephen B alston

D rew S. D ays, III

Melvyn L eventhal

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P.

Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

APPENDICES

Appendix A

Final Order of the District Court

(Filed July 11, 1975)

l x THE

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F ob the W estern D istrict oe N orth Carolina

Charlotte Division

Civil No. 1974

J ames E. Sw ann , et al.,

—vs—

Plaintiffs,

T he Charlotte-M ecUlenbtjrg B oard oe E ducation, et al.,

Defendants.

F inal Order

(S wann Song)

On July 10, 1974, defendants filed a report covering

certain changes in the proposed 1974-75 pupil assignment

plan, and requested the court to dismiss the suit. On

July 30, 1974, the court entered an order approving the

revised plan under specified conditions, and expressing

appreciation to the Board, the Citizens Advisory Group

and the school staff people and others who had worked

to make it possible. The order closed with the comment

that, after May 1, 1975,

“ . . . assuming and believing that no action by the

court will then be required, I look forward with

la

2a

pleasure to closing the suit as an active matter of

litigation . .

Since early 1974, the case has been quiet. No new or

old issues have been raised by the litigants or decided

by the court. The new Board has taken a more positive

attitude toward desegregation and has at last openly

supported affirmative action to cope with recurrent racial

problems in pupil assignment. Though continuing prob

lems remain, as hangovers from previous active discrim

ination, defendants are actively and intelligently address

ing these problems without court intervention. It is time,

in the tenor of the previous order, to be “ closing the

suit as an active matter of litigation . .

Dismissal is neither usual nor correct in a case like

this where continuing injunctive or mandatory relief has

been required. Facts and issues once decided on their

merits ought, generally, to remain decided. This case

contains many orders of continuing effect, and could be

re-opened upon proper showing that those orders are

not being observed. The court does not anticipate any

action by the defendants to justify a re-opening; does

not anticipate any motion by plaintiffs to re-open; and

does not intend lightly to grant any such motion if made.

This order intends therefore to close the file; to leave

the constitutional operation of the schools to the Board,

which assumed that burden after the latest election; and

to express again a deep appreciation to the Board mem

bers, community leaders, school administrators, teachers

and parents who have made it possible to end this liti

gation.

The duty to comply with existing court orders respect

ing pupil assignment of course remains. So, also, does

Appendix A

3a

the duty to comply with constitutional and other legal

requirements respecting other forms of racial discrimina

tion.

Ghosts continue to walk. For example, some perennial

critics here and elsewhere are interpreting Professor James

Coleman’s latest dicta in support of the notion that courts

should abandon their duty to apply the law in urban

school segregation cases. Coleman is worried about “white

flight,” they say; school desegregation depends on Cole

man; therefore the courts should bow out; “ cessante ra~

tione, cessat ipsa lex,” they say.

The local School Board members have not followed

that siren. Perhaps it is because they realize that this

court’s orders, starting with the first order of April 23,

1969, are based, not upon the theories of statisticians,

but upon the Constitution of the United States, and be

cause they recall and are prepared to follow the law of

this case which, as to Coleman, is contained in the order

of August 3, 1970 (318 F.Supp. 786, 794, W.D.N.C. 1970),

as follows:

“ The duty to desegregate schools does not depend

upon the Coleman report, nor on any particular ra

cial proportion of students [emphasis from original],

— The essence of the Brown decision is that segrega

tion implies inferiority, reduces incentive, reduces mo

rale, reduces opportunity for association and breadth

of experience, and that the segregated education it

self is inherently unequal. The tests which show the

poor performance of segregated children are evidence

showing one result of segregation. Segregation would

not become lawful, however, if all children scored

equally on the tests.” (Emphasis added.)

Appendix A

Appendix A

I do not anticipate a revival, in the Charlotte-Mecklen-

bnrg school system, of this and other questions which

have already been exhaustively (and expensively) liti

gated and definitively answered.

With grateful appreciation to all who have made pos

sible this court’s graduation from Swann, it is therefore

Ordered:

1. That this cause be removed from the active docket.

2. That the file be closed.

This 11th day of July, 1975.

/ s / J ames B. M cM illan

James B. McMillan

United States District Judge

5a

Appendix B

A labama

Hereford v. Huntsville Board of Education, 504 F.2d 857

(5th Cir. 1974)*—Terminal desegregation plan approved

February 19, 1975.

Miller v. Board of Education of Gadsden, 482 F.2d 1234

(5th Cir. 1973)— Terminal desegregation plan ordered

September 11, 1973.

A rkansas

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock, 449 F.2d 493

(8th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 405 IT.S. 936 (1972)—Plain

tiffs entered into stipulation barring litigation over plan

in force for at least two years from June 28, 1973 and

for so long as Board abides by plan implemented for

1973-74 and for future years.

Davis v. Board of Education of North Little Rock, 449 F.2d

500 (8th Cir. 1971)—Terminal desegregation plan im

plemented in 1971-72.

Yarborough v. Hulbert-West Memphis School Dist. No. 4,

457 F.2d 333 (8th Cir. 1972)— Terminal desegregation

plan ordered February 11, 1972.

F lorida

Allen v. Board of Public Instruction of Broward County,

432 F.2d 362, cert, denied 402 U.S. 952 (1971)— Terminal

desegregation plan ordered June 21, 1971.

* Citations to the latest reported decision's in these cases are in

cluded primarily for purposes of identification.

6a

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction of Pinellas County,

431 F.2d 1377, cert, denied 402 U.S. 943 (1971)— Terminal

desegregation plan ordered January 11, 1972.

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

465 F.2d 878, cert, denied 410 U.S. 966 (1973)— Terminal

desegregation plan approved December 30, 1972.

Harvest v. Board of Public Instruction of Manatee County,

429 F.2d 414, cert, denied 402 U.S. 943 (1971)— Case

dismissed from active docket, September 15, 1973; re

porting required as to proposed new construction.

Steele v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County, 448

F.2d 767 (5th Cir. 1971)— Terminal plan ordered May

10, 1974, reinstating plan approved January 30, 1970.

Weaver v. Board of Public Instruction of Brevard County,

467 F.2d 473, cert, denied 410 U.S. 982 (1973)—Terminal

plan approved May 15, 1973.

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction of Bay County,

448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971)—Terminal plan approved

for 1971-72.

Georgia

Harrington v. Colquitt County Bd. of Education, 460

F.2d 193, cert, denied 409 U.S. 915 (1972)—Terminal

plan ordered October 27, 1972.

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County, 442

F.2d 1336 (5th Cir. 1971).

L ouisiana

Celestain v. Vermillion Parish. School Board, 364 F.Supp.

618 (W.D. La. 1972)—Terminal plan ordered December

30, 1974; case placed on inactive docket for two years.

Appendix B

7a

Gordon v. Jefferson Davis Parish School Board, 460 F.2d

1062 (5th Cir. 1972)— Terminal plan ordered for 1972-73.

M ississippi

Adams v. Rankin County Board of Education, 485 F.2d

324, 524 F.2d 928 (5th Cir. 1975).

Bell v. West Point Municipal Separate School Dist., 446

F.2d 1362 (5th Cir. 1971)—Terminal plan ordered Au

gust 31, 1971.

Franklin v. Quitman County Board of Education, 443 F.2d

909 (5th Cir. 1971).

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist., 480

F.2d 583 (5th Cir. 1973).

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist., 509

F.2d 818 (5th Cir. 1975).

N orth Carolina

Eaton v. New Hanover County Bd. of Education, 459 F.2d

684 (4th Cir. 1972)— Terminal plan ordered July 22,1971.

Wheeler v. Durham City Bd. of Education, 521 F.2d 1136

(4th Cir. 1975)— Terminal plan approved August 13,1975.

Oklahoma

Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City, 465 F.2d

1012 (10th Cir. 1972)— Terminal plan ordered February,

1972; modified in part June 3, 1974.

South Carolina

Adams v. School Dist. No. 5, Orangeburg County, 444 F.2d

99 (4th Cir. 1971)—Terminal plan ordered July 6, 1971.

Appendix B

8a

Appendix B

T ennessee

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Educ., 463 F.2d

732, cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972)— Terminal plan

implemented 1971-72.

T exas

Flax v. Potts, 464 F.2d 865, cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1007

(1972)—-Terminal plan approved August 23, 1973.

V irginia

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943, cert, denied,

406 U.S. 933 (1972).

Downing v. School Board of Chesapeake, 455 F.2d 1153

(4th Cir. 1972).

Hart v. County School Board of Arlington County, 459

F.2d 981 (4th Cir. 1972)— Terminal plan ordered August

10, 1971.

Thompson v. School Board of Newport News, 363 F. Supp.

458 (E.D. Va. 1973)— Terminal plan approved September

11, 1973.

MEILEN PRESS INC, — N. Y. C, 219