Villarreal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Pinstripe, Inc. En Banc Brief for Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

March 24, 2016

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Villarreal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Pinstripe, Inc. En Banc Brief for Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant, 2016. 19c98c10-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ba8aa856-a1d6-4e3d-84c7-856851f4ee0a/villarreal-v-rj-reynolds-tobacco-company-pinstripe-inc-en-banc-brief-for-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

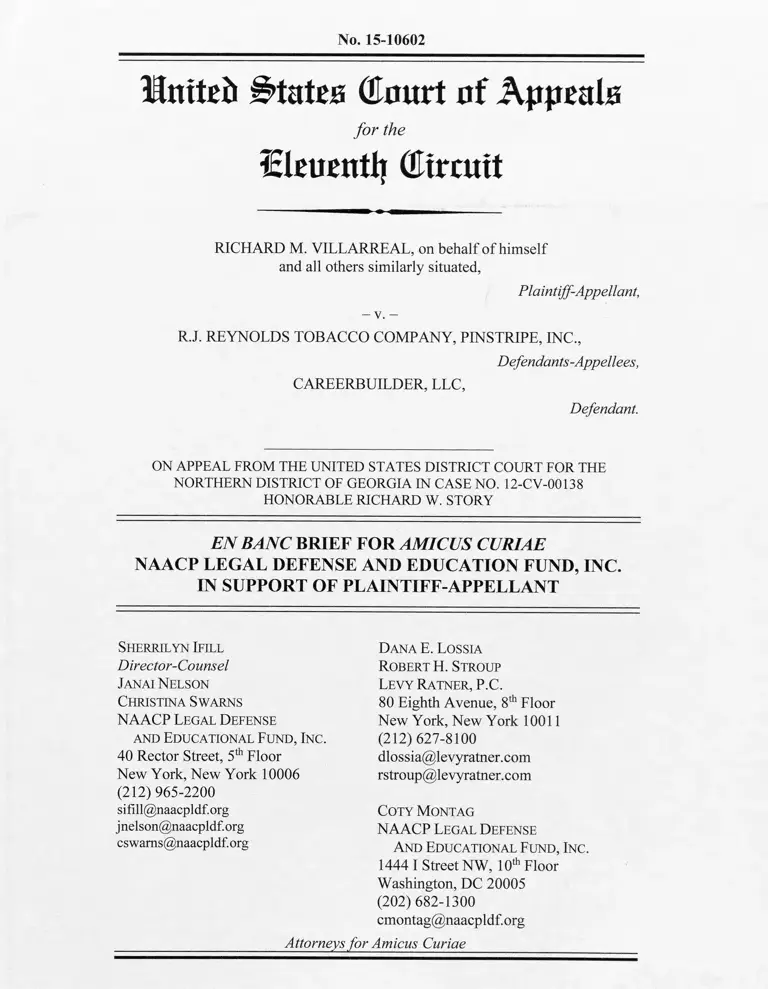

No. 15-10602

United States (Court of Appeals

fo r the

iEleuentlj (Circuit

RICHARD M. VILLARREAL, on behalf of himself

and all others similarly situated,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

— v. —

R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY, PINSTRIPE, INC.,

Defendants-Appellees,

CAREERBUILDER, LLC,

Defendant.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA IN CASE NO. 12-CV-00138

HONORABLE RICHARD W. STORY

EN BANC BRIEF FOR AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

Sherrilyn Ifill

Director-Counsel

Janai N elson

Christina S warns

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund , In c .

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, New York 10006

(212) 965-2200

sifill@naacpldf.org

jnelson@naacpldf.org

cswams@naacpldf.org

Dana E. Lossia

Robert H. Stroup

Levy Ratner , P.C.

80 Eighth Avenue, 8th Floor

New York, New York 10011

(212) 627-8100

dlossia@levyratner.com

rstroup@levyratner.com

Coty M ontag

NAACP Legal Defense

And Educational Fund, In c .

1444 I Street NW, 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

cmontag@naacpldf.org

Attorneys fo r Amicus Curiae

mailto:sifill@naacpldf.org

mailto:jnelson@naacpldf.org

mailto:cswams@naacpldf.org

mailto:dlossia@levyratner.com

mailto:rstroup@levyratner.com

mailto:cmontag@naacpldf.org

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS and

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The following is a complete list of persons and entities who, to the best of

Amiens Curiae the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.’s

knowledge, have an interest in the outcome of this case, pursuant to

Eleventh Circuit Rule 26.1 -1:

1. AARP - Amicus curiae in support of Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M.

Villarreal

2. Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP - Law firm for amicus curiae

Chamber of Commerce of the United States

3. Almond, John J. - Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

4. Altshuler Berzon, LLP - Law firm for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M.

Villarreal

5. Beightol, Scott - Former Attorney for Defendant-Appellee Pinstripe, Inc.

6. Benson, Paul - Former Attorney for Defendant-Appellee Pinstripe, Inc.

7. Berger & Montague, P.C. - Law firm for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M.

Villarreal

8. British American Tobacco p.l.c, (BTI) - A publicly traded company

with ownership interest in Brown & Williamson Holdings, Inc., the

Page C-l of 9

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, etal., No. 15-10602

indirect holder of more than 10% of the stock of Reynolds American

Inc., parent company of Defendant-Appellee R.J. Reynolds Tobacco

Company

9. Brown & Williamson Holdings, Inc. - Private company and holder of

more than 10% of the stock of Reyn olds American Inc., parent company

of Defendant-Appellee R J. Reynolds Tobacco Company

10. Brasoski, Donna J., attorney for amicus curiae U.S. Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

11. Campbell, R. Scott - Former Attorney for Defendant-Appellee Pinstripe, Inc.

12. CareerBuilder, LLC - Private company and former Defendant

13. Carson, Shanon J. - Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

14. Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America- Amicus curiae

in support of Defendants-Appellees R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and

Pinstripe, Inc.

15. Chen, Z.W. Julius - Attorney for amicus curiae Chamber of Commerce

of the United States

16. Cielo, Inc. - Name under which Defendant-Appellee Pinstripe, Inc.

now operates

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al., No. 15-10602

Page C-2 of 9

17. Dick, Anthony J. - Attorney for Defendants-Appellees R.J. Reynolds

Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

18. Dreiband, Eric S. - Attorney for Defendants-Appellees R.J. Reynolds

Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

19. Eber, Michael L. - Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

20. Equal Employment Advisory Council - Amicus curiae in support of

Defendants-Appellees R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

21. Finberg, James M. - Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

22. Girouard, Mark J. - Attorney for amicus curiae Retail Litigation Center, Inc.

23. Goldstein, Jennifer S. - Attorney for amicus curiae U.S. Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

24. Greenberg Traurig, LLP - Former law firm for Defendant-Appellee

Pinstripe, Inc.

25. Hunt, Hyland - Attorney for amicus curiae Chamber of Commerce of the

United States

26. Ifill, Sherrilyn - Attorney for amicus curiae the NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

27. Johnson, Mark T. - Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al., No. 15-10602

Page C-3 of 9

28. Jones Day - Law firm for Defendants-Appellees R.J. Reynolds Tobacco

Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

29. Kohrman, Daniel B. - Attorney for amicus curiae AARP

30. Leasure, Amy Beth. - Attorney for amicus curiae Equal Employment

Advisory Council

31. Levy Ratner, P.C. - Law firm for amicus curiae the NAACP Legal Defense

and Education Fund, Inc.

32. Livingston, Donald - Attorney for amicus curiae Chamber of Commerce of

the United States

33. Lopez, P. David - General Counsel for amicus curiae U.S. Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission

34. Lossia, Dana E. - Attorney for amicus curiae the NAACP Legal Defense

and Education Fund, Inc.

35. Marshall, Alison B. - Attorney for Defendants-Appellees R.J. Reynolds

Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

36. McArthur, Nikki L. - Attorney for Defendants-Appellees R.J. Reynolds

Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

37. McCann, Laurie - Attorney for amicus curiae AARP

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al., No. 15-10602

Page C-4 of 9

38. McClain, Sherron T. - Former attorney for Defendants-Appellees R.J.

Reynolds Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

39. Michael Best & Friedrich LLP - Former law firm for Defendant-Appellee

Pinstripe, Inc.

40. Montag, Coty - Attorney for amicus curiae the NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

41. NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. - Amicus curiae in

support of Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

42. Nelson, Janai - Attorney for amicus curiae the NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

43. Nilan Johnson Lewis PA - Law firm for amicus curiae Retail Litigation

Center, Inc.

44. NT Lakis, LLP - Law firm for amicus curiae Equal Employment Advisory

Council

45. Pinstripe Holdings, LLC - Private company and parent corporation of

Pinstripe, Inc., now operating as Cielo, Inc.

46. Pinstripe, Inc. - Private company and Defendant-Appellee, now operating as

Cielo, Inc.

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et a t, No. 15-10602

Page C-5 of 9

47. Pitts, P. Casey - Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

48. Postman, Warren - Attorney for amicus curiae Chamber of Commerce of the

United States

49. Retail Litigation Center, Inc. - Amicus curiae in support of Defendants-

Appellees R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

50. Reynolds American Inc. (RAI) - Publicly held company and parent

company of Defendant-Appellee R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company

51. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company - Private company and

Defendant- Appellee

52. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Holdings, Inc.- Private company and

parent company of Defendant R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company

53. Rogers & Hardin LLP - Law firm for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M.

Villarreal

54. Schalman-Bergen, Sarah R. - Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M.

Villarreal

55. Schmitt, Joseph G. - Attorney for amicus curiae Retail Litigation

Center, Inc.

56. Schneider, Todd M. - Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, etal., No. 15-10602

Page C-6 of 9

57. Schneider Wallace Cottrel Brayton Konecky, LLP - Law firm for Plaintiff-

Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

58. Seyfarth Shaw LLP - Law firm for former Defendant CareerBuilder, Inc.

59. Smith, Dara - Attorney for amicus curiae AARP

60. Smith, Frederick T. - Attorney for former Defendant CareerBuilder, LLC

61. Story, Richard W. - Trial Judge, U.S. District Court for the Northern District

of Georgia

62. Stroup, Robert H. - Attorney for amicus curiae the NAACP Legal Defense

and Education Fund, Inc.

63. Sudbury, Deborah A. - Attorney for Defendants-Appellees R.J. Reynolds

Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

64. Swams, Christina - Director of Litigation for amicus curiae the NAACP

Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.

65. Todd, Kate Comerford - Attorney for amicus curiae Chamber of Commerce

of the United States

66. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission - Amicus curiae in

support of Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal

67. Vann, Rae T. - Attorney for amicus curiae Equal Employment Advisory

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al., No. 15-10602

Page C-7 of 9

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al., No. 15-10602

Council

68. Villarreal, Richard M. - Plaintiff-Appellant

69. Wheeler, Carolyn L. - Attorney for amicus curiae U.S. Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

70. White, Deborah R. - Attorney for amicus curiae Retail Litigation Center, Inc.

71. Wojdowki, Haley A. - Attorney for Defendants- Appellees R.J. Reynolds

Tobacco Company and Pinstripe, Inc.

Dated: March 24, 2016 /s/ Christina Swams

Christina Swams

Director of Litigation

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

Page C-8 of 9

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al., No. 15-10602

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. Rules 26.1 and 29(c), Amicus Curiae the

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. discloses the following:

1. The NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. has no parent

corporations and no subsidiary corporations.

2. No publicly held company owns 10% or more stock in the NAACP

Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.

Dated: March 24, 2016 /s/ Christina Swarns_______

Christina Swams

Director of Litigation

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

Page C-9 of 9

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CITATIONS..............................................................................................ii

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE............................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES...................................................................................2

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS...................................................................................2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT..................................................................................... 2

ARGUMENT..................... 4

I. The Reeb Standard for Evaluating Equitable Tolling Claims Effectively

Combats Unlawful Employment Discrimination...................................................4

A. The Remedial Purposes of the ADEA and Title VII Strongly Support

Reaffirming the Reeb Standard........................................................................ 7

B. This Court Should Not Depart From Its Forty-Year History of Applying

the Reeb Standard.............................................................................................. 9

1. The Equitable Tolling Standard Ensures that Plaintiffs’ Obligations Are

Not Triggered Before There Is Reason to Believe that Discrimination

Occurred................................. 9

2. The Reeb Standard Should Apply Here to Equitably Toll Mr. Villarreal’s

Claims................................................................................................................12

II. Departure from the Reeb Standard Would Undermine Congressional Intent,

Burden Job Seekers And Employers, And Swamp the EEOC With Speculative

Claims..................................................................................................................... -15

CONCLUSION.............................................................................................................20

i

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases P a g e(s)

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975)............................................................................................. 1,5

Arce v. Garcia,

434 F.3d 1254 (11th Cir. 2006)................................................................................7

Ashcroft v. Iqbal,

556 U.S. 662 (2009).................................................................................................15

BellAtl. Corp. v. Twombly,

550 U.S. 544 (2007)..."..............................................................................................15

Blankenship v. Ralston Purina Co.,

62 F.R.D. 35 (N.D. Ga. 1973)...................................................................................7

Bond v. Dep't o f the Air Force,

202 Fed. Appx. 391 (11th Cir. Ga. 2006).............................................................12

Bond v. Roche,

2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 1684 (M.D. Ga. Jan. 9, 2006)........................................ 12

Bast: v. Fed. Express Corp.,

372 F.3d 1233 (11th Cir. 2004)...................................................................... 11, 12

Brotherhood o f Locomotive Engineers & Trainmen Gen. Comm, o f

Adjustment CSXTransp. N. Lines v. CSXTransp., Inc.,

522 F.3d 1190 (11th Cir. 2008)............................................ ................................ 10

Calhoun v. Ala. Alcoholic Beverage Control Bd.,

705 F.2d 422 (11th Cir. 1983).................... ...................................... ........... ........14

Cocke v. Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc.,

817 F.2d 1559 (11th Cir. 1987).............................................................................14

Farley v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co.,

197 F.3d 1322 (11th Cir. 1999)...............................................................................7

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

495 F.2d 398 (5th Cir. 1974), rev ’d on other grounds, 424 U.S. 747

(1976)..........................................................................................................................8

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424(1971)................................................................................................... 1

Hargett v. Valley Fed. Sav. Bank,

60 F.3d 754 (11th Cir. 1995)..................................................................................14

Hill v. Metro. Atlanta Rapid Transit Auth.,

841 F.2d 1533 (11th Cir. 1988).............................. 14

In t’l Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324(1977).............. 5

Jones v. Dillard’s, Inc.,

331 F.3d 1259 (11th Cir. 2003).................................................................. 9, 14, 16

Lewis v. City o f Chicago,

560 U.S. 205 (2010)......................................................................................... 1

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973).........................................................................................6

Nelson v. U.S. Steel Corp.,

709 F.2d 675 (11th Cir. 1983).......................................... .................................... 14

Reeb v. Economic Opportunity Atlanta, Inc.,

516 F.2d 924 (5th Cir. 1975)..........................................................................passim

Ricci v’. DeStefano,

557 U.S. 557 (2009).........................................................................................1

Ross v. Buckeye Cellulose Corp.,

980 F.2d 648 (11th Cir. 1993) cert, denied, 513 U.S. 814, 115 S. Ct. 69,

130 L. Ed. 2d 24 (1994)................................................................................... passim

Sturniolo v. Sheaffer, Eaton, Inc.,

15 F.3d 1023 (11th Cir. 1994).................................................................... 9, 14, 16

Turlington v. Atlanta Gas Light Co.,

135 F.3d 1428 (11th Cir. 1998)................................................................. ...........14

iii

Woodford v. Kinney Shoe Corp.,

369 F. Supp. 911 (N.D. Ga. 1973)............................................................................8

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, Inc.,

455 U.S. 385, 102 S. Ct. 1127 (1982)...................................................................... 7

Statutes

Age Discrimination in Employment Act, 29 U.S.C. §621 et seq.....................passim

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq..............passim

O th er A u th o r ities

Charge Statistics, FY 1997 - FY 2015, EEOC, available at

http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/.......................................................................................4

Ortman, et ah, An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States,

Current Population Reports, P25-1140, U.S. Census Bureau, 2014,

available at ww.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-l 140.pdf................................... 4

Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2016, available at:

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/defmition/american_english/futile....... 18

Villarreal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.,

2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 30018 (N.D. Ga. Mar. 6, 2013)..............................passim

IV

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE1

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is a non

profit legal organization that, for more than seven decades, has fought to achieve

racial justice and ensure that America fulfills its promise of equality for all. Since

1964, LDF has worked ceaselessly to enforce Title VII of the Civil Rights Act,

litigating on behalf of individual plaintiffs and plaintiff classes against private and

public employers to challenge discriminatory employment practices in such cases

as Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), and Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). LDF’s victories in these cases were ultimately

codified in the Civil Rights Act of 1991. More recently, LDF has served as

counsel of record or amicus curiae in a range of employment discrimination cases

brought under Title VII in the United States Supreme Court and the lower courts.

See, e.g., Lewis v. City o f Chicago, 560 U.S. 205 (2010); Ricci v. DeStefano, 557

U.S. 557 (2009).

Given its expertise in employment discrimination matters, LDF believes its

perspective will assist this Court in resolving the issues presented by this case,

particularly with respect to the Eleventh Circuit’s equitable tolling standard.

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al., No. 15-10602

1 LDF certifies that no party or party’s counsel authored this brief in whole or in

part, or contributed money that was intended to fund the briefs preparation or

submission, and further certifies that no person, other than LDF and its members,

contributed money intended to prepare or submit this brief. Fed. R. App.

P.29(c)(5). Both parties have consented to the filing of LDF’s brief.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Whether this Court should continue to apply the equitable tolling

standard set out in Reeb v. Economic Opportunity Atlanta, Inc., 516 F.2d 924

(5th Cir. 1975), and repeatedly reaffirmed by this Court, in which the EEOC

charge-filing deadline is tolled while the charging party did not know and could

not reasonably have learned that he had been a vi ctim of unlawful discrimination.

2. Whether, under that standard, Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M.

Villarreal adequately pleaded a claim for equitable tolling by alleging facts which

establish that a reasonably prudent person could not have become aware of the

basis for his charge until less than one month before the charge was filed.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Amicus curiae the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.

incorporates by reference the “Statement of the Case” contained in the En Banc

Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant Richard M. Villarreal.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Employment discrimination against older workers and workers of color

remains entrenched within the American labor market, in spite of Congress’s

intention to eradicate such forms of invidious discrimination through the enactment

of federal anti-discrimination laws. The procedural rules governing the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act, 29 U.S.C. §621 et seq. (“ADEA”), (ADEA)

2

and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq. (“Title

VII”) should not be contorted to provide protection to employers whose secret and

unlawful hiring preferences are undermining Congressional purposes. As this

Court recognized more than forty years ago in Reeb v. Economic Opportunity

Atlanta, Inc., 516 F.2d 924 (5th Cir. 1975), until such secret preferences became

apparent, or should become apparent, to reasonably prudent employees and

applicants, the statute of limitation for bringing a charge of discrimination should

be equitably tolled. This tolling standard, which has been consistently reaffirmed

by this Court for decades, is the only means by which to effectively combat

employment discrimination.

Departure from the Reeb standard would undermine Congressional intent by

improperly burdening job seekers with diligence requirements - before they have

even a mere suspicion of discrimination - that are certain to prove futile. It would

also place unwelcome burdens upon employers, who would experience an increase

in requests for application, hiring, promotion and retention data. And, it would

drain the already limited resources of the EEOC by prompting unsuccessful job

applicants to seek to preserve their rights by filing speculative claims, before any

facts supporting a charge of discrimination have become apparent.

3

Where, as here, the plaintiff had no reason to believe discrimination had

occurred until shortly before the filing of his charge, this Court should - as it has

for decades - apply the Reeb standard and grant equitable tolling,

ARGUMENT

I. THE REEB STANDARD FOR EVALUATING EQUITABLE

TOLLING CLAIMS EFFECTIVELY COMBATS UNLAWFUL

EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION.

Employment discrimination continues to be a deep-rooted problem for the

American economy and for individual workers and job-seekers. Discriminatory

policies and practices by employers distort the functioning of the labor market,

depriving American industry of the most qualified workforce, while

simultaneously inflicting direct economic harm upon innocent men, women, and

families. In particular, race and age discrimination in the workplace remain

disconcertingly prevalent. In 2015, more than 31,000 charges of race

discrimination and more than 20,000 charges of age discrimination were filed with

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). See Charge Statistics,

FY 1997 - FY 2015, EEOC, available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/

statistics/enforcement/charges.cfm (last visited March 24, 2016). In the next

several decades, the older population of the United States is expected to become

more racially and ethnically diverse. See Ortman, et al., An Aging Nation: The

Older Population in the United States, Current Population Reports, P25-1140. U.S.

4

http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/

Census Bureau, Washington, DC. 2014, available at www.census.gov/prod/

2014pubs/p25-l 140.pdf (last accessed on March 24, 2016). Experience and

history dictate that these older workers of color will face multiple dimensions of

disadvantage based on both age and race stereotypes. As a result, these workers, as

well as the American economy and labor force, will need the strong protections of

the federal anti-discrimination laws.

In enacting the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, 29 U.S.C. §621 et

seq. (“ADEA”), Congress noted that “older workers find themselves disadvantaged

in their efforts . . . especially to regain employment when displaced from jobs” and

“the incidence of unemployment, especially long-term unemployment. . . is,

relative to the younger ages, high among older workers; their numbers are great

and growing; and their employment problems grave.” 29 U.S.C. § 621(a).

Likewise, Congress enacted Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §

2000e, et seq. (“Title VII”) in order to “remove barriers that have operated in the

past to favor an identifiable group of white employees over other employees.’”

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417 (1975) (quoting Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429-30 (1971)). In enacting Title VII, Congress was

intent upon “eradicating discrimination throughout the economy.” Albemarle, 422

U.S. at 421. See also In t’l Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 364

(1977) (couching primary objective of Title VII as “to achieve equal employment

5

http://www.census.gov/prod/

opportunity and to remove the barriers that have operated to favor white male

employees over other employees”) (citing Griggs, 401 U.S. at 427; Albemarle, 422

U.S. at 416). In order to achieve this goal, Title VII not only prohibits

discriminatory employment practices that are express and direct, but also those that

are subtle and indirect. See McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 801

(1973) (“Title VII tolerates no racial discrimination, subtle or otherwise.”).

As employers attempt to evade liability under the ADEA and Title VII, the

discriminatory hiring preferences confronting older workers - and particularly

older workers of color - often take the form of subtle or indirect “secret

preferences” that are unknown to the applicants and employees whose

opportunities they constrain. For this reason, in Reeb v. Economic Opportunity

Atlanta, Inc., the court recognized that the deadline for fding a charge of

discrimination with the EEOC is equitably tolled until a plaintiff knows or

reasonably should have known the facts necessary to support a claim of

discrimination. 516 F.2d 924, 931 (5th Cir. 1975). The equitable tolling standard

set forth in Reeb, which has been followed by this Circuit in employment

discrimination cases for more than forty (40) years, is a critical vehicle for

ensuring that secret and unlawful hiring preferences are not shielded from legal

challenge by the procedural rules governing the federal anti-discrimination

statutes.

6

A. THE REMEDIAL PURPOSES OF THE ADEA AND TITLE VII

STRONGLY SUPPORT REAFFIRM ING THE REEB STANDARD.

Courts in this Circuit “look to the relevant statute for guidance in

determining whether equitable tolling is appropriate in a given situation.” Arce v.

Garcia, 434 F.3d 1254, 1261 (11th Cir. 2006); see also Zipes v. Trans World

Airlines, Inc., 455 U.S. 385, 398, 102 S. C't. 1127, 1135 (1982) (in applying

charge-filing deadlines, courts must “honor the remedial purpose of the legislation

as a whole”). In enacting the ADEA, Congress sought “to promote employment of

older persons based on their ability rather than age.” 29 U.S.C. §621 (b). “In any

action brought to enforce [the ADEA] the court shall have jurisdiction to grant

such legal or equitable relief as may be appropriate to effectuate the purposes of

this Act.” 29 U.S.C. §626(b). See also Farley v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., 197

F.3d 1322, 1338 (11th Cir. 1999) (“The central purpose of [the ADEA] is to ‘make

the plaintiff ‘whole,’ to restore the plaintiff to the economic position the plaintiff

would have occupied but for the illegal discrimination of the employer.’”)

(quoting Castle v. Sangamo Weston, Inc., 837 F.2d 1550, 1561 (11th Cir. 1988));

Woodv. Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 725 F. Supp. 1244, 1251 (N.D. Ga. 1989)

(“Defendant’s hyper-technical reading of the 180 day rule does not comport with

the quintessentially remedial purpose of the ADEA.”); Blankenship v. Ralston

Purina Co., 62 F.R.D. 35, 38 (N.D. Ga. 1973) (“Since Congress clearly defined its

policy as remedial with respect to such social problems, the courts have generally

7

looked to the Congressional intent behind the law rather than to procedural

restrictions which might impair the law’s effectiveness.”)

“The [ADEA] is remedial and humanitarian in its nature as is Title VII.

Courts construing Title VII’s procedural limitations have been extremely reluctant

to allow technicalities to bar claims brought under that statute.” Woodford v.

Kinney Shoe Corp., 369 F. Supp. 911 (N.D. Ga. 1973). “In fact, courts confronted

with procedural ambiguities in Title VII’s statutory framework have with virtual

unanimity resolved them in favor of the complaining party.” Id., citing Sanchez v.

Standard Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d 455 (5th Cir. 1970); see also Franks v. Bowman

Transp. Co., 495 F.2d 398, 404 (5th Cir. 1974), rev’d on other grounds, 424 U.S.

747 (1976) (“Congress did not intend to condition a claimant’s right to sue under

Title VII on fortuitous circumstances or events beyond his control which are not

spelled out in the statute.”)

In fashioning a standard for equitable tolling that is consistent with

Congressional intent, this Court has rightly considered the particular context of

employment discrimination, and, in particular, situations where “[sjecret

preferences in hiring and even more subtle means of illegal discriminati on, because

of their very nature, are unlikely to be readily apparent to the individual

discriminated against.” Reeb, 516 F.2d at 931. Accordingly, the standard set forth

in Reeb is the only tolling rule that gives proper effect to the remedial purposes

served by Title VII and the ADEA.

B. THIS COURT SHOULD NOT DEPART FROM ITS FORTY-

YEAR HISTORY OF APPLYING THE REEB STANDARD.

1. The Equitable Tolling Standard Ensures that Plaintiffs’

Obligations Are Not Triggered Before There Is Reason to Believe

That Discrimination Occurred.

Since 1975, this Court has held that the limitations period in employment

discrimination cases is properly tolled “until the facts which would support a cause

of action are apparent or should be apparent to a person with a reasonably prudent

regard for his rights.” Reeb, 516 F.2d at 930. Thus, in Jones v. Dillard’s, Inc., 331

F,3d 1259, 1267 (11th Cir. 2003), this Court held that an employee who had only a

“mere suspicion” of age discrimination was not obligated to take legal action,

because she lacked sufficient factual basis to make out a prima facie case of

unlawful conduct. It was only once she became aware that her employer had hired

a younger worker to fill her former position that she was in a position to make out

a claim; it was the receipt of this information that triggered her obligation to make

a timely complaint to the EEOC. Id. at 1268; see also Sturniolo v. Sheaffer, Eaton,

Inc., 15 F.3d 1023, 1026 (11th Cir. 1994).

For decades, the law of this Circuit has held that an applicant for

employment does not need to file a charge - or take any other step - where, as

here, there was “no reason to believe” discrimination had occurred. Ross v.

9

Buckeye Cellulose Corp., 980 F.2d 648 (11th Cir. 1993) cert, denied, 513 U.S.

814, 115 S. Ct. 69, 130 L. Ed. 2d 24 (1994). It is only once facts that would

support a cause of action are apparent or should be apparent to a person with a

reasonably prudent regard for his rights that the obligations of due diligence are

triggered. Id. at 660, citing Reeb, 516 F.2d at 931,2 3

In arguing that Mr. Villarreal’s claims should not be equitably tolled, the

panel dissent fails to cite a single Eleventh Circuit employment discrimination case

in which the plaintiff had “no reason to believe” he was the victim of

discrimination. Ross, 980 F.2d at 660; Villarreal, 806 F.3d at 1311-16. Instead, to

reach his conclusion that the facts here do not support use of this “extraordinary”

remedy, Judge Vinson relies upon cases that are either outside the employment

discrimination context or cases involving employees who already believed, based

on facts already in their possession, that discrimination had occurred. 3 Villarreal,

2 This Court has applied this distinction even outside the context of employment

discrimination claims. See, e.g., Brotherhood o f Locomotive Engineers &

Trainmen Gen. Comm, o f Adjustment CSX Transp. N. Lines v. CSX Transp., Inc.,

522 F.3d 1190, 1197 (11th Cir. 2008) (“‘[F]or statute of limitations purposes[,] a

plaintiffs ignorance of his legal rights and his ignorance of the fact of his injury or

its cause should [not] receive identical treatment.’ The determinative fact is

whether the plaintiff had knowledge of the harm incurred.”) (quoting United

States v. Kubrick, 444 U.S. I l l , 122, 62 L. Ed. 2d 259, 100 S. Ct. 352 (1979)).

3 Among the five unpublished employment discrimination cases cited by the panel

dissent, not a single case involves a situation in which an applicant or employee

was found to have had “no reason to believe” that employment discrimination had

10

806 F.3d at 1311-16. For example, in Ross, 980 F.2d at 660, this Court found that

the plaintiffs - far from having no suspicion of employment discrimination -

alleged race discrimination in “numerous confrontations” with the employer over

roughly a decade. In such a case, where the facts that would support a charge

already were already “apparent” to the potential plaintiffs, it was appropriate to

require evidence of diligence and of extraordinary circumstances before granting a

request for equitable tolling.

The Ross court itself took care to draw this distinction, noting that “[i]n

order for equitable tolling to be justified in this case, the facts must show that, in

the period more than 180 days prior to filing their complaints with the EEOC,

appellants had no reason to believe that they were victims o f unlawful

discrim inationR oss, 980 F.2d at 660 (emphasis added).

Likewise, Bost v. Fed. Express Corp., 372 F.3d 1233, 1242 (11th Cir. 2004),

which was relied upon by the panel dissent for the proposition that equitable tolling

“is an extraordinary remedy which should be extended only sparingly,” also

concerns a situation in which “the facts which would support a cause of action”

occurred. Ross, 980 F.2d at 660; Villarreal, 806 F.3d at 1312 n. 10. Rather, all

were cases in which the plaintiffs already strongly believed they had been victims

of discrimination based upon facts in their possession, but who failed, without

good cause, to act within required timeframes. Id. Those cases are therefore not

relevant to the circumstances of the instant case.

11

were already very much apparent to the plaintiffs, who had already filed a charge

of discrimination but were seeking to toll the 90-day period to file suit after

receiving their right-to-sue letter from the EEOC. The circumstances in Bost are

entirely different from those presented here, where Mr. Villarreal had “no reason to

believe” that age discrimination had occurred. Ross, 980 F.2d at 660.

The District Court below made the same error in relying primarily upon

Bondv. Roche, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 1684 (M.D. Ga. Jan. 9, 2006). In that case,

as this Court later held, the plaintiff “reasonably should have known” before the

expiration of the charge-filing period “that he might have a discrimination claim.”

Bondv. D ep'tofthe Air Force, 202 Fed. Appx. 391 (11th Cir. Ga. 2006)

(unpublished) (emphasis added). As discussed below, in this case, Mr. Villarreal

could not reasonably have known that he might have a discrimination claim, and

he properly pled his lack of knowledge.

2. The Reeb Standard Should Apply Here to Equitably Toll Mr.

Villarreal’s Claims.

Plaintiff applied for a Territory Manager position at RJ Reynolds by

personally uploading his resume to the company website. App. Vol. II, Dkt. No.

61-1, at 5 TflO. RJ Reynolds’s job posting did not specify a preference for

candidates who were “2-3 years out of college,” nor did it notify applicants that

those with “8-10 years” of prior sales experience need not apply. App. Vol. I, Dkt.

12

No. 1, at 7 115 & Exh. A; App. Vol. II, Dkt. No. 61-1, at 7 f 14 & Exh. A.

However, unbeknownst to Mr. Villarreal, these preferences were included in the

“Resume Review Guidelines” that RJ Reynolds provided to its recruiting services.

App. Vol. I, Dkt. No. 1, at 7 115 & Exh. A; App. Vol. II, Dkt. No. 61-1, at 6-7 114

& Exh. A. The guidelines instructed the recruiting services to “stay away from”

various applicants, including those who had been “in sales for 8-10 years.” App.

Vol. I, Dkt. No. 1, at 7 115 & Exh. A; App. Vol. II, Dkt. No. 61-1, at 7 114 & Exh.

A. Thus, as a direct result of the employer’s “secretpreferences” in hiring, when

Mr. Villarreal was not contacted about the position, he accepted it as a matter of

course. He had “no reason to believe” - or even suspect - unlawful discrimination,

because RJ Reynolds never told the applicants what standards it was applying.4

Ross, 980 F.2d at 660.

In every equitable tolling case decided by this Court, the Reeb standard was

applied when the plaintiff had “no reason to believe” that employment

4 There is reason to believe that RJ Reynolds kept this preference secret by design:

it received thousands of applications from individuals who did not meet its profile

of an ideal candidate, and yet it took no steps to clarify its “ideal candidate” in its

vacancy notice or to alert prospective applicants who did not meet its secret

qualifications (e.g., those with lengthier sales histories) that they need not apply.

App. Vol. I, Dkt. No. 1, at 12 f25; App. Vol. II, Dkt. No. 61-1, at 11 |24. To the

contrary, Mr. Villarreal received an email from RJ Reynolds in 2010 soliciting

applications for Territory Manager positions, even though the company was not

looking for 52-year old applicants and never had been. See Villarreal v. RJ.

Reynolds Tobacco Co., 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 30018, *4 (N.D. Ga. Mar. 6, 2013).

13

discrimination had occurred. See, e.g., Jones, 331 F.3d at 1268; Turlington v.

Atlanta Gas Light Co., 135 F.3d 1428, 1435 (11th Cir. 1998); Hargett v. Valley

Fed. Sav. Bank, 60 F.3d 754, 765 (11th Cir. 1995); Sturniolo, 15 F.3d at 1025;

Ross, 980 F.2d at 660; Hill v. Metro. Atlanta Rapid Transit Auth., 841 F.2d 1533,

1545 (11th Cir. 1988); Cocke v. Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc., 817 F.2d 1559, 1561

(11th Cir. 1987); Nelson v. U.S. Steel Corp., 709 F.2d 675, 611 n.3 (11th Cir.

1983); see also Calhoun v. Ala. Alcoholic Beverage Control Bd., 705 F.2d 422,

425 (11th Cir. 1983). Accordingly, because Mr. Villarreal properly pled that he

had no reason to believe that employment discrimination had occurred until shortly

before his charge was filed, Villarreal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., 2013 U.S.

Dist. LEXIS 30018, *7 (N.D. Ga. Mar. 6, 2013), he had no obligation to plead

additional facts concerning diligence.

The District Court below erred in holding that Mr. Villarreal was required to

plead the facts that “alerted Plaintiff to his discrimination claim [and] how he

learned those facts.” Villarreal, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 30018, *20. Rather, at

most and as explained by the panel majority, “[a]t this early stage, Mr. Villarreal is

simply required to ‘plead the applicability of the doctrine.’” Villarreal, 806 F.3d at

1303 (quoting Oshiver v. Levin, Fishbein, Sedran & Berman, 38 F.3d 1380, 1391

(3d Cir. 1994)). Even if Mr. Villarreal were required to plead more specific facts

about when and how the facts supporting his charge became apparent to him -

14

which Eleventh Circuit precedent does not require him to do - he should have been

granted permission to amend his complaint to explain that in April 2010, attorneys

from Altshuler Berzon LLP contacted him and informed him, for the first time, that

RJ Reynolds had used the discriminatory Resume Review Guidelines when

screening his November 2007 application. App, Vol. II, Dkt. No. 61-1, at 12-13

^[29-30. These factual allegations would plainly meet and exceed the pleading

standards of Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662 (2009), and Bell Atl. Corp. v.

Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007).

II. DEPARTURE FROM THE REEB STANDARD WOULD

UNDERMINE CONGRESSIONAL INTENT, BURDEN JOB

SEEKERS AND EMPLOYERS, AND SWAMP THE EEOC WITH

SPECULATIVE CLAIMS.

The Reeb standard - applied consistently by courts in this Circuit for more

than forty years - has effectuated the Congressional purposes in enacting the

ADEA and Title VII while also limiting the burdens upon employers, applicants,

and the EEOC. As discussed below, the instant case demonstrates how a

modification to the current rule would have negative consequences both for

businesses and job seekers.

Mr. Villarreal applied for the position of Territory Manager at RJ Reynolds

but received no response from the company. See Villarreal, 2013 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 30018, *2-3. The lack of response from an uninterested employer is a

common experience for virtually anyone who has ever been in search of work,

15

including those who are well-qualified for the positions they seek. Even if Mr.

Villarreal had inquired about “whether his application had been reviewed,” as the

dissent suggests he should have done, Villarreal, 806 F.3d at 1292, and even if RJ

Reynolds had acknowledged that it had reviewed his application, the legally

relevant facts would have remained the same: Mr. Villarreal would have “no

reason to believe” that he was the victim of unlawful discrimination. Ross, 980

F.2d at 660.

Likewise, if Mr. Villarreal had inquired about the status of his application

and been informed, as he was in 2010, 2011 and 2012, that the company intended

to pursue other candidates, Villarreal, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 30018, *4, he would

still have had “no reason to believe” that his application was rejected on account of

age discrimination. Ross, 980 F.2d at 660. See also Jones, 331 F.3d at 1267

(plaintiffs claims were equitable tolled when she had a “mere suspicion” of

discrimination). Even if Mr. Villarreal had, for some reason, strongly suspected

age discrimination - although he had no basis for such a suspicion - he would not

have had sufficient information upon which to state a cause of action. Id. at 1266

(“Sturniolo[, 15 F.3d at 1026] teaches that [plaintiffs] suspicion, without more, is

insufficient to establish pretext.”).

This Circuit does not require unwarranted or unprompted investigations on

the part of applicants who have no reason to suspect that they have been

16

discriminated against. Such a standard, which would first require applicants to

inquire whether their applications have been received or to ask whether they have

been rejected for the job, would be entirely impractical. Even with these facts, an

applicant would have insufficient information to pursue a claim of discrimination.

If an applicant was no longer able to rely on the Circuit’s equitable tolling standard

and was required to take action on entirely speculative claims, he would be

required - for each of the perhaps dozens or scores of position for which he applies

and is rejected (or hears nothing) - to endeavor to obtain the following information

from the employer: (1) the demographic characteristics of fellow applicants, both

successful and unsuccessful, and (2) the internal procedures and criteria used in the

employer’s hiring process in order to support a viable claim of employment

discrimination. These efforts would be required even in circumstances where the

applicant has no reason to suspect discrimination. Otherwise, the applicant, who

may later learn facts that would support a prima facie case of employment

discrimination, would have forfeited his claim.

Such efforts at diligence would, as recognized by the majority, be futile.

Villarreal, 806 F.3d at 1305. Prospective employers have no legal obligation, and

no incentive, to provide such information, and they would certainly refuse to do so.

Employers who are actually motivated by “secret preferences,” Reeb, 516 F.2d at

31, would be even more likely to deny applicants access to evidence sufficient to

17

make out a prima facie case of age discrimination. Requiring applicants to seek

such information from employers is pointless.5

Without the equitable tolling standard, applicants who have no reason to

suspect employment discrimination would be required, in order to protect their

rights to obtain relief for later-discovered discrimination, to: (1) make impractical,

and perhaps costly, efforts to gather information to prove a phantom claim, which

would undoubtedly alienate prospective employers, or, even more absurdly, to (2)

file a speculative charge of discrimination with the EEOC to avoid the running of

the statute of limitations for the phantom claim. Under the diligence scheme

suggested by the panel dissent, this would be the only way for such applicants to

protect their rights.

Such a framework would likely have damaging ripple effects throughout the

economy. Employers would find themselves receiving additional requests for data

and other information from applicants. Employers who opted not to respond to

such requests, or who responded by refusing to provide the requested information,

would fear opening their businesses up to possibly unwarranted, negative

5 The Oxford English Dictionary defines “futile” as “Incapable of producing any

useful result; pointless.” Oxford University Press, 2016, available at:

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/defmition/american_english/futile.

18

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/defmition/american_english/futile

inferences. Employers who did respond to such requests would do so at

considerable expense of money, time, and human resources.

Applicants themselves would spend time and resources on the unproductive

task of requesting information, rather than devoting their efforts to seeking

employment. Alternately, applicants who opted not to engage in futile fact-

gathering efforts and instead filed premature and unsupported charges of

discrimination, would significantly burden the EEOC’s already limited resources.

Moreover, this scheme would harm the Congressional purpose of eradicating age

discrimination, because once the premature and unsupported charges of

discrimination were dismissed by the EEOC, applicants who later became aware of

facts supporting a charge of unlawful age discrimination would likely be time

barred - by the 90-day period in which to bring suit - from raising supportable and

meritorious claims.

The absurdity of this result demonstrates the wisdom of the Circuit’s current,

long-standing framework for evaluating claims of equitable tolling in employment

discrimination cases, in which diligence is required only after the facts that would

support a charge of discrimination are apparent or should have become apparent to

a potential plaintiff with a reasonably prudent regard for his rights. Reeb, 516 F.2d

at 931.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the district court’s decision should be

REVERSED.

Respectfully submitted,

/s/Christina Swarns

March 24, 2016

By: CHRISTINA SWARNS

Director of Litigation

SHERR1LYNIFILL

Director-Counsel

LANAI NELSON NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

(212) 965-2200

COTY MONT AG

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 I Street NW, 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

DANA E. LOSSIA

ROBERT H. STROUP

LEVY RATNER, P.C.

80 Eighth Avenue Floor 8

New York, New York 10011

(212) 627-8100

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

20

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

This brief complies with the type-volume limitation of Fed. R. App. P.

32(a)(7)(B) because it contains 4,680 words, excluding the parts of the brief

exempted by Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B)(iii) and 11th Cir. R. 32-4.

This brief complies with the typeface requirements of Fed. R. App. 32(a)(5)

and the type style requirements of Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(6) because it has been

prepared in a proportionally spaced typeface in 14-point Times New Roman font,

in text and footnotes, using Microsoft Word 2013.

March 24, 2016 /s/ Christina Swams_______________

Christina Swams

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al., No. 15-10602

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on March 24, 2016,1 electronically filed the foregoing

brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund in Support of Plaintiff-

Appellant with the Clerk of Court for United States Court of Appeals for the

Eleventh Circuit by using the Court’s CM/ECF electronic filing system, and that

all participants in the case are registered CM/ECF users and service will be

accomplished by the Court’s CM/ECF system.

March 24, 2016 /s/ Christina Swarns___________ _

Christina Swams

Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al, No. 15-10602

$

C O U N S E L PRESS

The Appellate Experts

460 WEST 34TH STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10001

(212) 685-9800; (716) 852-9800; (800) 4-APPEAL

www.counselpress.com

(264914)

http://www.counselpress.com