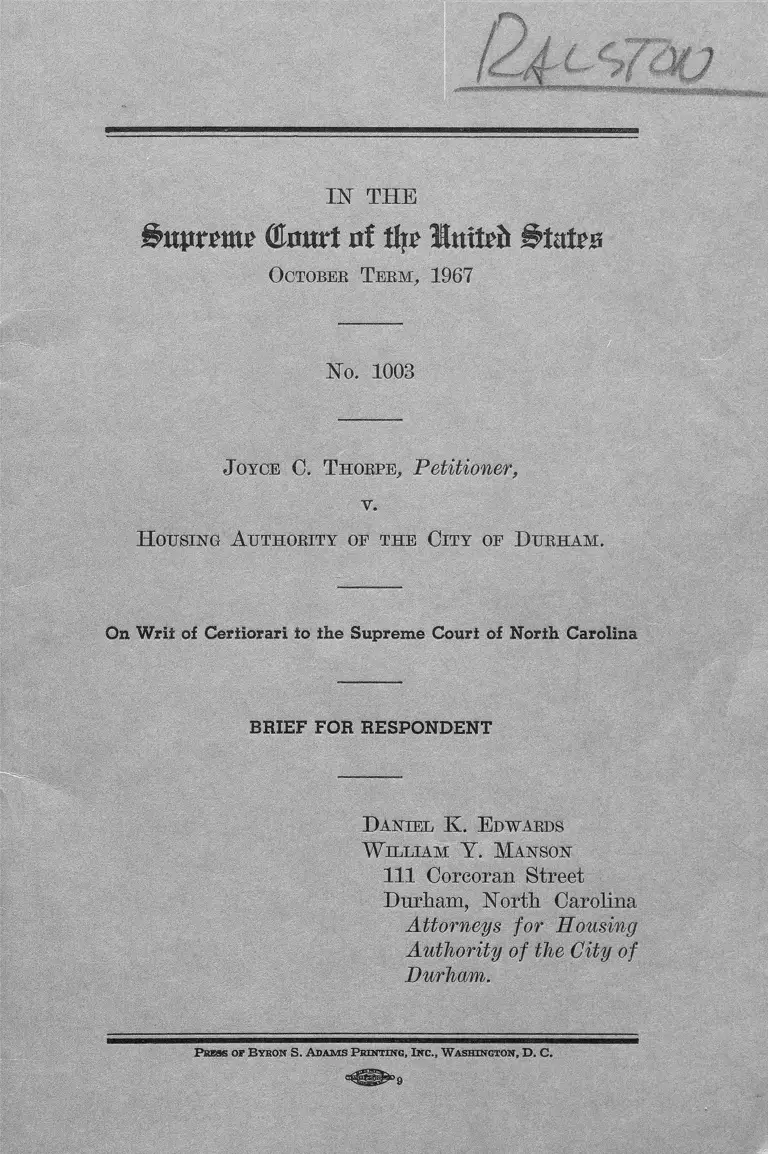

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham Brief for Respondent, 1967. 95d38e2f-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ba8dc8f9-877f-4398-917c-b0240cb77556/thorpe-v-housing-authority-of-the-city-of-durham-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Cmnri at % Inttefo

October T erm , 1967

No. 1003

J oyce C. T horpe, Petitioner,

r.

H ousing A uthority of the City of D u rh am .

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of North Carolina

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

----------

D aniel K . E dwards

W illiam Y. M anson

111 Corcoran Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Housing

Authority of the City of

Durhaml

P ress of B yron S. A d a m s P rinting, Inc., W ashington, D . C.

INDEX

Questions Presented ....................................................

Statement of Facts .............................. ......................

Summary of Argument.............................................. .

Argument

I, The Eviction Proceedings in the Court Below

Did Not Violate Constitutional Due Process^Be

cause an Aedquate Hearing Was Provided

During the Trial Below and Because the Hous

ing Authority Was Not Required to Have a

Reason Other Than the Expiration of the Term

of the Lease .......................................................

A. An Adequate Hearing was Provided by the

Trial Below ..................................................

B. The Housing Authority was not Required to

Show a Reason Other than the End of the

Term of the Lease ................................ .. • • 12

II. The Lease Entered Into hy the Petitioner and

the Housing Authority Is Not an Unconstitu

tional Method of Prescribing and Defining the

Tenant’s Right of Occupancy........................... 18

III. The Circular, Whatever It May Be, Did Not

Have Application to Events that Occurred be

fore the Issuance Date of the Circular............. 24

Conclusion

Appendix

TABLE OF CASES

Barsky v. Board of Regents, 347 US 442 .................... 18

Bell v. Maryland, 378 US 226 ....................................... 18

Bourjois v. Chapman, '301 US 183, 189; 57 S. Ot. 691,

81 L, Ed. 1027 (1937) ............................................. 8

Brand v. Chicago Housing Authority, 120 F. 2d 786,

(CCA 7, 1941) .........................................13,14,19,24

11 Index Continued

Page

Cafeteria and Restaurant Workers Union v. McEIroy,

367 US 886 ............................................................. 16

Chicago Housing Authority v. Blackman, 4 111. 2d 319,

_ 122 NE 2d i522 (1954) ......................................... 13

Chicago Housing Authority v. Ivory, 341 111, App. 282,

93 NE 2d 386 <1950)....................................... 13,14,19

Chicago Housing Authority v. Lindsey Stewart, ------

111. — (1968) ...................................................13,19

Chin Tow v. United States, 208 US 8 ........................... 12

Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority v. Simpson,

85 Ohio App. 73, 85 NE 2d 560 (1949)................ 14,19

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180

6th 'Cir. 1955) ......................................................... 13

Erie Railroad Company v. Tompkins, 304 US 6 4 ......... 18

Paris v. United States, 192 F. 2d 53 (10th Cir. 1951) . . . 15

FHA v. The Darlington, Inc., 358 US 8 4 .................... 28

Fleming v. Rhodes, 331 US 100 .................................. 28

Goldsmith v. U. S. Board of Tax Appeals, 270 US 117 16

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 US 306, 313: 85 S. Ct. 384

(19641 .................................................................... 27

Holt v. Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Au

thority, 266 F. Supp. 397 (E.D. Va., 1966)............. 13

Housing Authority v. Johnson, 261 NO 76, 134 SE 2d

121 ......................................................................... 17

Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh v. Turner,

201 Pa. Super. 62, 191 A. 2d 869 (1963) ............ 14,19

Housing Authority v. Thorpe, 271 NC 468, 157 SE 2d

147 (1967) ......................................................15,17, 20

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. MrGrath,

341 US 123............................................................. 16

Kwong Hai Chew v. Golding, 344 US 590 .................... 17

Lynch v. United States, 292 US 571, 64 S. Ct. -840, 78

L. Ed. 1434 .......................................................18,19,28

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 US 501..................................... 16

Morgan v. United States, 304 US 1 .............................. 17

Municipal Housing Authority for City of Yonkers v.

Walck, 277 App. Div. 791, 97 NTS 2d 488, (2d

Dept. 1950) ...........................................................15 19

Ng Fung Ho v. White, 259 US 276 .............................. ’ 17

Randell v. Newark Housing Authority, 384 F. 2d 1951

(CCA 3-1967) .................................................... 8

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 US 479 ..................................... 16

Index Continued m

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 US 398 16

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education, 360 US 051 16

Snowden v. Hughes, 321 US 1 ..................................... 12

Thorpe v. Housing Authority, 386 US 670 (1967)---- 8

Toreaso v. Watkins, 367 US 488 .................................. 16

Tucker v. Texas, 326 US 517 ......................................... 18

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330' US 7 5 ......... . 16

United States v. Blumenthal, 315 F. 2d 351 (3rd Cir.

1963) ....................................................................15,17

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Crunch 103, 110; 2

L, Ed. 49 (1801) ............................ 27

Walton v. City of Phoenix, 69 Ariz. 26, 208 P. 2d 309

(1949) ...................................................................14,19

Wells v. Housing Authority, 213 NO 744, 197 SE 693 17

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 US 183............................... 16

Williams v. Housing Authority of Atlanta, 223 Ga.

407,155 SE 2d 923 (1967)...................................... 15

Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness, 373

US 9 6 .....................................................................16,17

United States Housing Act of 1937, as amended (42

USC § 1401) ...........................................5,20,24,25,29

General Statutes of North Carolina §42-26(1) ......... 10

General Statutes of North Carolina § 157-1 through

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS

25

26

26, 27

27

27

§ 157-48 17, 20, 25, 29

IH THE

&uprrntr Court of ftjr Imtrii States

October Term, 1967

Ho. 1003

J oyce C. T horpe, Petitioner,

v.

H ousing A uthority op the City op Durham.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of North Carolina

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The Petitioner was a tenant under a written lease in

a housing project owned by the Respondent which was

constructed with funds borrowed from private sources

and which is supported, in part, by annual contrihu-

2

tions from the Federal Government pursuant to a

Contract with the Respondent, Housing Authority of

the City of Durham. The Housing Authority is a

corporation, organized under the Housing Authority

Law of the State of North Carolina, which empowered

it to enter into an Annual Contributions Contract with

agencies of the Federal Government. Pursuant to

the terms of the lease, the Housing Authority gave the

Petitioner notice it was not renewing the term of her

lease and instituted an eviction proceeding in the

Courts of the State after the tenant failed to vacate

at the end of the term. The Petitioner defended, con

tending that she was being evicted because she had

participated in a tenants’ organization and that she

was entitled, as a matter of law, to an administrative

hearing before the institution of the eviction proceed

ings in the State Courts. It was determined, as a

matter of fact, that the reason for her eviction wTas not

her participation in the organization of a tenants’

group.

1. Hnder these circumstances, does the due process

clause o f the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States require that the

Petitioner be given an administrative hearing prior

to the institution of an eviction proceeding against her

in the State Courts?

2. Was the eviction proceeding in the Courts of

the State of North Carolina violative of the due proc

ess clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States?

3. Was a HUD Circular, promulgated on February

7, 1967, effective to invalidate the eviction action in

the Courts of the State of North Carolina, instituted

in the State Courts on September 17, 1965?

3

STATEMENT OF FACTS

It was stipulated by the parties to this action that

the Petitioner occupied a dwelling apartment owned

by the Housing Authority of the City of Durham

pursuant to and under and by virtue of a lease which

she entered into with the Housing Authority. (A. 5).

It was also established for the purposes of this case

by stipulation that the Petitioner received the notice

of termination; that she alleged that the reason she

was being evicted was her participation in the organi

zation of the Parents’ Club; that the trial Judge could

hear and determine the cause by finding facts based

on the stipulations and any Affidavits entered into

the record; that the Executive Director of the Housing

Authority, if present and duly sworn, would testify

that whatever reason there may have been, if any,

for giving notice to Petitioner of the termination of

her lease it was not for the reason that she was elected

President of any group organized in McDougald Ter

race, and not for any other reason set forth in her

Affidavit,, and was not because of her efforts to organize

the tenants; and, further, that the Executive Director

did so testify in the hearing before the Justice of the

Peace when the case was initially heard. (A. 6 & 7).

Petitioner alleged in her Affidavit that “ On the 1st

day of September, 1965, the Housing Authority of the

City of Durham and C. S. Oldham met with Detective

Prank McRae, of the Police Department of the City

of Durham, who supplied them with certain informa

tion allegedly uncovered during the investigation of

her conduct.” (A. 9).

The trial in the Superior Court of North Carolina,

though on appeal from the Judgment of the Justice

of the Peace, was de novo, and in the absence of

4

stipulation would require the introduction of evidence

by the Housing Authority to make out its case. Pro

ceeding according to the stipulation, the Court found

for the Housing Authority, making specific findings

of fact with respect to the Petitioner’s allegation as

to the reason for the termination of her lease. (A. 21).

During the trial, the Petitioner offered no evidence

that was excluded by the Court and made no effort

to cross-examine any witness of the Housing Authority

or any official of the Housing Authority. In the

Petitioner’s Exceptions and Assignments of Error on

appeal to the Supreme Court of North Carolina, there

was no mention of any refusal by the trial Court to

admit any evidence offered by the Petitioner nor any

complaint about any refusal of the trial Court to permit

any cross-examination. (A. 25).

This Court remanded the case to the Supreme Court

of North Carolina to determine what effect, i f any,

the HUD Circular of February 7, 1967, had upon the

proceedings. The Supreme Court of North Carolina,

after hearing, held that the HUD directive, whatever

its prospective effect might be, did not invalidate the

notice of August 11, 1965, terminating Petitioner’s

lease nor the eviction proceedings instituted in the

State Courts on September 17, 1965.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Petitioner, finding nothing in the relevant leg

islation enacted by the Congress of the United States

or by the State Legislature of North Carolina that

bestows upon her a right to occupy a dwelling unit

in the housing project owned by the Respondent, other

than the right acquired by virtue of executing the

lease, has resorted to this Court, contending that it

5

should supply such legislative omission by interpre

tation of the provisions of the Constitution of the

United States. W e respectfully submit that it is the

wisest course to leave the issues stirred here with the

legislative branch which has the fiscal resources to

implement its decisions as well as the responsibility

to limit the scope of its decisions to its financial re

sources. The Constitution may permit the Congress

to provide housing for all indigent persons, but it

does not require that it be done. W e submit further

that the Constitution does not prohibit the Congress

from providing housing for some indigents without

providing it for all.

By its appropriations the Congress has, in fact,

sought to provide housing for some, but not all, of

the indigents in the country. It has not sought to

establish which of these indigents shall receive the

housing, leaving that matter to the discretion of local

agencies with the exception of certain priorities that

it established for certain categories of persons. These

categories do not affect this Petitioner.

A decision by this Court that all equally eligible

indigents have a Constitutional right of occupancy

of dwelling units in low-rent, housing projects would

nullify the purpose and effect of the United States

Housing Act of 1937, as amended, since that Act and

the appropriations supporting it cannot implement

that result.

The program of the Congress to inject into the

housing market a substantial number of low-rent

housing units should not be struck down because it

is not all-inclusive nor because the technique em

ployed is not the building and operation of housing

6

units by the Federal Government but by financial sup

port to State and local agencies conducting local

programs.

A First Amendment issue does not present itself

on this record. The record in this case does not show

that Petitioner was evicted because of the exercise

of any such Constitutional right. The opinion of the

North Carolina Supreme Court on rehearing makes

clear that it does not support the theory that a tenant

may be evicted for the exercise of such a right.

The trial Court found on competent evidence that

the Housing Authority did not notify the tenant that

her lease would not be automatically renewed for

another term because she exercised a First Amend

ment right as she asserted. Neither the trial Court

nor the State Supreme Court refused the tenant right

to present evidence nor to have the Court make findings

upon that issue. In a judicial eviction proceeding,

the North Carolina Statute does require the landlord

to affirmatively show only that the tenant is holding

over after the expiration of the term of his lease or

that he has violated some provision of the lease. As

suming, arguendo, that a tenant could defeat an evic

tion by showing the Housing Authority was motivated

by a design to prevent the exercise of a Constitutional

right, this Statute is not unconstitutional as it applies

to the Housing Authority as a landlord, since it does

not prevent the tenant from asserting or showing that

the notice, whereby the Housing Authority prevented

the automatic renewal of the term of the tenant’s lease,

was invalid and ineffectual for that reason. The Con

stitution does not place this burden of proof upon this

landlord.

7

This eviction, being through judicial process, afforded

the tenant a full judicial hearing in the trial Court

which would seem to be more impartial and constitu

tionally acceptable than a hearing by the Housing

Authority itself. The Petitioner had, therefore, full

opportunity to establish any lawful defense she wished.

During the trial of this action, the tenant did not

seek to inquire into any reasons the Housing Authority

may have had for failing to renew her lease other

than her assertion that it acted because of her organi

zational activities among the tenants. !She did raise

that issue, and the trial Court passed upon it—not by

ruling it irrelevant, but by finding against her on

the evidence. The procedures available to the tenant

in this case adequately protected her from any repri

sals for the exercise of any Constitutional rights.

The tenant has no Constitutional right to remain in

occupancy without a lease or after the expiration of

the term of the lease. The fact that the lease, by its

terms and provisions, was for thirty days’ duration

(instead of being for the lifetime of the tenant) did

not constitute a violation of the Constitution nor the

Federal or State Statutes pertaining to the Housing

Authority’s operation.

The relationship between the Petitioner and the

Housing Authority being contractual—that is, by virtue

of a lease—and the relationship between the Housing

Authority and HUD being contractual by virtue of

a written Annual Contributions Contract, the Con

stitution does not require the State Courts to give the

HUD Circular of February 7,1967, a retroactive effect

to amend these Contracts as of the date notice of termi

nation was given.

8

ARGUMENT

I.

THE EVICTION PROCEEDINGS IN THE COURT BELOW DID NOT

VIOLATE CONSTITUTIONAL DUE PROCESS BECAUSE AN

ADEQUATE HEARING WAS PROVIDED DURING THE TRIAL

BELOW AND BECAUSE THE HOUSING AUTHORITY WAS

NOT REQUIRED TO HAVE A REASON OTHER THAN THE

EXPIRATION OF THE TERM OF THE LEASE.

A . An Adequate Hearing Was Provided by the Trial Below

Justice White, in his dissenting opinion in Thorpe

v. Housing Authority, 386 US 670 (1967), stated:

“ Petitioner was afforded a full due process hearing in

the lower court and had the opportunity to explore

fully why she was evicted.” Justice Douglas, in his

concurring opinion, stated: “ Moreover, is there a con

stitutional requirement for an administrative hearing

where, as here, the tenant can have a full judicial

hearing when the Authority attempts to evict him

through judicial process? Petitioner has had a hear

ing in the State 'Courts.” In her Brief, the Petitioner

states: “ Certainly, proceedings in open court, held be

fore the governmental action at issue became effective,

might satisfy the requirements of due process. ’ ’ (Peti

tioner’s Brief, p. 43). Justice Brandeis, delivering

the opinion of the Court in Bourjois v. Chapman, 301

US 183,189, 57 iS. Ct. 691, 81 L. Ed. 1027 (1937), made

the same point.1 To like effect is Randell v. Newark

1He said: “ And neither Constitution (Constitution of the State

of Maine and the Constitution of the United States) requires

that there must be a hearing of the applicant before the Board

may exercise a judgment under the circumstances and of the

character here involved. The requirements, of due process of law

amply safeguarded by Section 2 of the Statute, which provides:

‘ Prom the refusal of said department to issue a certificate of

registration for any cosmetic preparation, appeal shall lie to the

Superior Court in the County of Kennebec or any other county

in the State from which the same was offered for registration’.”

9

Housing Authority, 384 F. 2d 1951 (OCA 3-1967),

where the Court said: “ . . . the problem of eviction of

tenants is governed by the New Jersey judicial rules

relating to proceedings between landlord and tenant-----

Under these statutes, in order for a housing authority

to enforce an eviction, they must have recourse to the

state courts. . . . Viewing thus the entire statutory

pattern, it does seem clear that the most probable in

terpretation of the statutes guarantees due process via

the necessary role the state courts play in any eviction.”

During the trial of this matter in the Superior Court,

the defendant did not quarrel with the nature nor with

the scope of the judicial inquiry, but contended only

that due process required that the Housing Authority

give the tenant notice of its reasons and a hearing

thereon before it instituted eviction proceedings—in

fact, before giving her notice of termination. This was

the theme of Petitioner’s “ Motion to Quash” in the Su

perior Court (A. p. 10). When the trial Court found

as a f act that, prior to giving her notice of the termina

tion of the lease, the Petitioner was not given a hearing

by the Housing Authority and that the Housing Au

thority gave no reason to the defendant for giving her

notice the lease was being terminated at the end of the

term, it found further that the Petitioner “ had no hear

ing other than that before the Justice of the Peace in

this eviction action and in this Court” (A. p. 22). The

Petitioner did not object or except to this, and, in her

Assignments of Error on Appeal from the Superior

Court to the Supreme Court of North Carolina, did not

object to the scope of the judicial inquiry. There was

no request that the trial Court enlarge its inquiry into

matters not acted upon by the Court in its findings of

fact nor any request for examination of any witnesses

10

that was denied. As the Court said in Bandell v.

Newark Housing Authority, supra: “ A party cannot

refuse to make any use of a system of ‘ administrative’

and ‘ judicial’ relief clearly open to him and thus

create a record on which a Federal Court can decide

that the party has been denied due process, or that

due process safeguards are lacking.”

The Petitioner’s present position—that it would have

been futile for Petitioner to have attempted to explore

the pre-eviction notice situation further during the trial

because under the eviction statute of North Carolina

the Court could not make such an exploration possible

—is not valid. In its findings the trial Court itself

found that she was having a hearing on this matter

in the course of the trial (A. p. 22). It is true, as

Petitioner asserts (Petitioner’s Brief, p. 43), that this

action was brought under North Carolina General

Statutes, Section 42-26(1), which is an action based on

a tenant’s holding over after the expiration of the

term of his lease, but that would not restrict the in

quiry. On that issue, the Housing Authority had to

show the lease and the language thereof that provided

for a term of a period of thirty days, and was auto

matically renewable unless a fifteen-day notice was

given. It would then have to show that a lawful notice

was given in order that the term of the lease not be

automatically renewed. The nature of the notice, its

language, its timing, and its motivation could be in

quired into.

There was some language in the original opinion of

the North Carolina Supreme Court in this case that

could be construed as saying the motivation was not

material, although we do not agree this construction

11

would be proper. However, on rehearing, the North

Carolina Supreme Court certainly clarified that point

by carefully considering the contention of the Peti

tioner that she had been evicted because of her organ

izational activities among the tenants and the finding

of the trial Court that she had not been evicted for

that reason—this being her sole contention about mo

tives. The Court did not consider what other and

additional inquiry or efforts at discovery the Petitioner

could have made before or during the trial since on

the record there was no issue of that sort before the

Court (A. pp. 38, 39, 40). We do not contend that, in

the case of Housing Authority leases if the purpose of

the notice of termination of the lease is to proscribe the

exercise of a constitutional right by the tenant the

notice would be effective; the notice would be invalid,

and the term of the lease and its automatic renewal

would not thereby be affected.

The Petitioner now contends, however, that “ Because

of the Court’s apparent new view that the reason for

eviction had become relevant, it should have, instead of

reaffirming, remanded the case to the trial court to

require the Authority to come forward with a reason

for its action and to give Petitioner an opportunity

to present her evidence and to have the cause tried on

the true issues.” (Petitioner’s Brief, pp. 45, 46.)

This assumes that constitutional due process requires

that whenever a Housing Authority presents its evic

tion case in Court, it must not only introduce the lease

and evidence showing that the term of the lease had

expired by reason of proper notice being given as pro

vided in the lease, but, also, to show a judicially ac

ceptable reason for its relying on the termination pro

cedures stated in the lease.

12

B. The Housing Authority Was Not Required To Show a

Reason Other Than the End of the Term of the Lease

When we agree that there are reasons for which the

Housing Authority could not terminate the Petitioner’s

lease, we are talking about reasons such as those al

leged by the Petitioner in the trial Court—to-wit, an in

fringement upon the exercise of some constitutional

right. For the most part, tenants would certainly be

aware of any deprivation of such constitutional rights

and would be able to allege that they were being re

stricted in the exercise thereof. It is not reasonably

necessary to require the Housing Authority to state

some other reason for the sole purpose of negating a

possible infringement upon the exercise of the con

stitutional right. Moreover, for the Authority to estab

lish that it had no reason other than its desire to term

inate the lease would be just as effective for this

purpose. It is not unreasonable to require the tenant

to assert what constitutional right is being violated.

(Snowden v. Hughes, 321 US 1; Chin Yow v. United

States, 208 US 8.)

Upon a rehearing, the Housing Authority, of course,

could not show that it had given the tenant a hearing

of its own prior to giving notice of termination, nor

could it show that it had stated to the tenant what its

reason, if any, was. I f these were the relevant issues,

a rehearing by the trial Court, as Justice Douglas

points out, would serve no purpose. Also, the trial

Court and the North Carolina Supreme Court had al

ready passed on the evidence relating to Petitioner’s

claim of denial of her exercise of First Amendment

rights, and on the evidence had found against her.

There was competent evidence upon which the trial

Court could make this finding of fact; and it, therefore,

13

should he sustained. Only if the trial Court had re

fused to make findings of fact on this point because

it deemed it irrelevant would a rehearing be required,

since that position would have brought this case within

the rule followed in Holt v. Richmond Redevelopment

and Housing Authority, 266 F. Supp. 397 (E.D. Ya.,

1966) and in Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis,

226 F. 2d 180 (6th Cir. 1955).

Oases decided throughout the land have recognized

and acted upon this theory. In Illinois, for example,

it is recognized that a Housing Authority cannot evict

a tenant because of an unconstitutional condition placed

upon occupancy as was the case in Chicago Housing

Authority v. Blackman, 4 111. 2d 319, 122 HE 2d o22

(1951), where the Housing Authority notified the

tenant that it was terminating the lease because of

the tenant’s failure and refusal to subscribe to a loyalty

oath. On the other hand, where no unconstitutional

condition was found, there was no prohibition against

the Housing Authority’s evicting a tenant holding a

month-to-montk tenancy under lease after giving due

notice of termination without assigning any reason

other than that the lease had terminated under its

terms. Chicago Housing Authority v. Ivory, 341 111.

App. 282, 93 HE 2d 386 (1950) ; Brand v. Chicago

Housing Authority, 120 E. 2d 786 (CCA 7,1941). This

rule in Illinois was recently applied by the Illinois Su

preme Court in Chicago Housing Authority v. Lindsey

S tew a r t , (------ 111. ------ (1968)) decided in March,

1968. In that case, Justice Klingbiel, speaking for the

Court, said: “ It is urged that due process of law pre

cludes an ‘ arbitrary’ termination of tenancies such as

this. W e cannot accept such a contention. It was a

condition of granting to defendant these benefits, at

14

public expense, that the occupancy he on a month-to-

month basis, and such are the terms upon which the

defendant took possession. There is nothing arbitrary

about requiring a public-housing tenant to vacate at the

expiration of his lease, nor does it deny due process of

law, or any other constitutional right that reasons for

doing so are not specified. (Housing Authority of the

City of Pittsburgh v. Turner, 201 Pa. Super. 62, 191 A.

2d 869.) As the Federal Court of Appeals observed in

a similar case: ‘Any property right acquired by the

plaintiffs was circumscribed by the terms and condi

tions upon which it was founded. True, as tenants, they

acquired the right of possession, but this right was lim

ited by the terms of the lease, by which such right was

obtained. By express provision thereof, either party

was entitled to cancellation on fif teen days notice to the

other. It is our opinion that this provision with refer

ence to the termination of the tenancy is valid and bind

ing upon plaintiffs in the same manner as though the

lessor had been a private person rather than a Govern

mental Agency.’ Brand v. Chicago Housing Authority

(7th Cir. 1941) 120 F. 2d 786.”

In other jurisdictions the same distinction has pre

vailed. This is easily seen by contrasting the cases

cited by Petitioner in her Brief, Page 20 thereof, with

such eases as Walton v. City of Phoenix, 69 Ariz. 26, 208

P. 2d 309 (1949) ; Chicago Housing Authority v. Ivory,

supra; Brand v. Chicago Housing Authority, supra;

Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh v. Turner,

201 Pa. Super. 62, 191 A. 2d 869 (1963); Columbus

Metropolitan Housing Authority v. Simpson, 85 Ohio

App. 73, 85 NE 2d 560 (1949), which are all in accord

with the decision of the North Carolina Supreme Court

in this ease and are, on the facts presented, directly in

15

point. To like effect are United States v. Blumenthal,

315 F. 2d 351 (3rd Cdr. 1963) ; Municipal Housing Au

thority for City of Yonkers v. Walck, 277 App. Div.

791, 97 NYS 2d 488 (2d Dept. 1950) ; Faris v. United

States, 192 F. 2d 53 (10th Cir. 1951) ; and Williams v.

Housing Authority of Altanta, 223 (la. 407, 155 SE 2d

923 (1967).

The only case cited hy the Petitioner directly sup

porting her position here is Vinson v. Greenburgh

Housing Authority,, decided by New York Supreme

Court’s Appellate Division, Second Department, on

March 11,1968, where two of the five Judges dissented.

The proposal for a rehearing, then, could he based

only on the theory that other reasons were relevant

and that the burden was upon the Housing Authority

to show them.2 Reasons other than tenant’s exercise

of the constitutional right would he relevant only if

the Court held that the tenant had a constitutional right

of occupancy, apart from the lease, that could he ended

only hy judicially approved reasons.

This, therefore, is clearly not a due process argument,

absent such a right. It is indeed pertinent to determine

“ the precise nature of the interest that has been ad

2 In Holt., the Court cites Housing Authority v. Thorpe, 271 NO

468 (1967), and said: “ There, however, the Court found as a

matter of fact that whatever may have been plaintiff’s reason for

terminating the lease, it was neither because the defendant had

engaged in efforts to organize the tenants nor because she had been

elected President of a tenants’ group. It is that factual distinc

tion which makes that decision inapplicable to the case at Bar.”

It is that factual distinction which makes the cases cited by the

Petitioner relating to the imposition of unconstitutional conditions

inapplicable ato this ease at Bar. See pages 19 and 20 of Peti

tioner’s Brief.

16

versely affected.” (Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Com

mittee v. McGrath, 341 US 123; see Petitioner’s Brief,

p. 37.) “ Due process” does not create the “ interest” ;

due process requirements arise only after a legal in

terest is found to exist. (In Willner v. Committee on

Character and Fitness, 373 US 96, it was admittance

to the Bar; in Goldsmith v. U. S. Board of Tax Ap

p e a ls 270 US 117, it was the privilege of practicing

before the Board of Tax Appeals—rights which should

be available to all qualified persons.)

In declining to renew the Petitioner’s lease, the

Housing Authority was not acting as a legislative body

nor as a judicial body nor as a regulatory board or

commission, but, rather, as a proprietor managing the

operation of a housing project. ( Cafeteria and Res

taurant Workers Union v. McFlroy, 367 US 886.)

With respect to this proprietary function, the Housing

Authority, under the State law, had no greater powers

than those of any other landlord; in fact, the Peti

tioner is contending that it had much less authority

than any other landlord. (See Marsh v. Alabama,

326 US 501.)3 The scope and nature of the Housing

Authority is private in nature and is Government

connected only by virtue of the fact that its housing

facilities are in part financed by the Federal Govern

ment, and this makes its position unlike that of the

8 As we have pointed out before, the doctrine prohibiting the

imposition of unconstitutional conditions by an agency of the

Government, even if applicable to the Housing Authority, does not

present an issue in this case. Therefore, Sherbert v. Yerner, 374

US 398; Toreaso v. Watkins, 367 US 488; Shelton v. Tucker, 364

US 479; United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 US 75; Slochower

v. Board of Higher Education, 350 US 551; and Wieman v. Upde-

graff, 344 US 183, and other cases in this category cited by Peti

tioner are not applicable.

17

Board in Willner v. Committee on Character and

Fitness, supra, where it was held that requirements

of procedural due process must be met before a State

can exclude a person from practicing law.4

Although the Housing Authority Law of the State

of North Carolina (Gr. S. 157-1 through 157-48) grants

the Housing Authority varied powers in connection

with planning, investigating and advising with mu

nicipalities in operating its housing project and in its

dealings with the Petitioner, it was not acting either

as an agent of the State or of the municipality or of

the Federal Government. It was acting pursuant to

its statutory power to ‘ ‘ prepare, carry out and operate

housing projects” (G. S. 157-9). Wells v. Housing

Authority, 213 NC 744,197 SE 693; Housing Authority

v. Johnson, 261 NO 76, 134 SE 2d 121; Housing Au

thority v. Thorpe, 271 NC 468, 157 SE 2d 147 (1967).5

4 In Morgan v. United States, 304 US 1, there was no constitu

tional issue decided, but the Court there did refer to the quasi

judicial functions of administrative agencies—in that ease, the

Secretary of Agriculture in fixing maximum rates at Kansas City

Stockyard. To like effect are the deportation eases, holding that

there must be an effective review of administrative action by reg

ular judicial branch of the Government— Ng Fung IIo v. White,

259 US 276, holding that persons about to be deported were en

titled to a judicial determination of their claims that they are

citizens o f the United States and Ewong Hcd Chew v. Golding, 344

US 590.

5 In United States v. Blumenthal, 315 P. 2d 351 (3rd Cir. 1963),

the defendant, a month-to-month lessee of business property owned

by the Federal Government in the Virgin Islands, who was dis

possessed, argued that the Government acted arbitrarily in failing

to specify in the notice to quit the reason for his decision. In

deciding against the defendant, the Court said: 1 ‘ The fact that the

plaintiff gave no reason for its notice to quit and sought to evict

the defendant while renting other similar business properties to

other tenants on a similar month-to-month basis is said to amount

18

If, then, we look to the decisions of the North Carolina

Supreme Court for authoritative construction of North

Carolina Statutes, as we must (Erie Railroad Com

pany v. Tompkins, 304 US 64; Tucker v. Texas, 326

US 517; Bell v. Maryland, 378 US 226; Barsky v.

Board of Regents, 347 US 442), the State statute does

not help the Petitioner’s argument here. The landlord

is treated as an ordinary landlord with no govern

mental powers, and the tenant is treated as an ordi

nary tenant with the usual rights of tenants, with the

possible additional right not to be penalized for exer

cising a constitutional right. (Lynch v. United States,

292 US 571, 54 8. Ct. 840, 78 L. Ed. 1434!.)

In view of this, it is not oppressive, not arbitrary,

not unjust—and not unconstitutional—in this confron

tation between Petitioner and Respondent to apply

rules generally applicable to others.

i i .

THE LEASE ENTERED INTO BY THE PETITIONER AND THE

HOUSING AUTHORITY IS NOT AN UNCONSTITUTIONAL

METHOD OF PRESCRIBING AND DEFINING THE TENANT'S

RIGHT OF OCCUPANCY.

W e come now to consider whether the month-to-

month written lease, executed by the plaintiff, violates

the Constitution when it provides that: “ The man

agement may terminate this lease by giving to the

tenant notice in writing of such termination fifteen

(15) days prior to the last day of the term.” (A.

p. 12). At the trial it was stipulated that the Peti

to discrimination against the defendant which was so arbitrary as

to deny due process of law. But the plaintiff, which is here acting

in its proprietary rather than its governmental capacity, has the

same absolute right as any other landlord to terminate a month-to-

month lease by giving appropriate notice and to recover possession

of the demised property without being required to give any reason

for its action.”

19

tioner occupied the dwelling unit “ pursuant to this

lease and under and by virtue of this lease.” (A.

p. 5). We take it that this means what it says, is

palpably true, and excludes any argument that the

Petitioner’s occupancy was by some right other than

the lease. This lease is a valid contract. Lynch v.

United States, supra; Walton v. City of Phoenix,

supra; Chicago Housing Authority v. Ivory, supra;

Brand v. Chicago Housing Authority, supra; Housing

Authority of the City of Pittsburgh v. Turner, supra;

Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority v. Simp

son, supra; Chicago Housing Authority v. Lindsey

Stewart, supra; and Municipal Housing Authority for

City of Yonkers v. Walck, supra.

The term of the lease—that it was for a term of

one month, automatically renewable unless notice of

termination was given—was an integral part of the

lease. I f the lease was invalid, then the Petitioner

had no right to occupancy of the premises, not even

squatter’s rights, since she had not there held ad

versely to the Housing Authority for the necessary

period of time. Her income eligibility to be accepted

as a tenant in the project did not give her a right of

occupancy, since all those who are so eligible are not

and cannot be accepted due to their number as con

trasted to the available dwelling units and, also, be

cause there is nothing in the program by State or

Federal Statute or Federal Eegulation that requires

the Housing Authority to construct or operate such

dwelling units to house all those who are eligible. The

statutory provisions prohibiting the continued occu

pancy by a tenant if the tenant’s income eligibility

ceases cannot be construed as meaning the tenant has

a right to occupancy so long as that eligibility con

tinues. On the other hand, the statutes creating the

program contemplated that occupancy of the dwelling

20

units be regulated by using the legal devises and

concepts normally involved in and arising from the

landlord-tenant relationship. The system produced

by both the United States Housing Act of 1937, as

amended, and the hiorth Carolina ‘ ‘ Housing Authority

Law” requires that this be done. The State statute

said, in several places, that the Housing Authority

may “ rent or lease the dwelling accommodations” (NC

Cl. S. 157-29; Housing Authority v. Thorpe, 271 NC

468, 157 S.E. 2d 147 (1967).) Language consistent

with these concepts is also contained in the Federal

statutes. Neither statute undertook to set out a form

for such lease nor prescribed the length of any term

nor the method by which the tenancy should be ended.

The Annual Contributions Contract between the

Housing Authority and the Federal Agency, in the

form which we believe to be generally applicable in

the nation, provides that a local authority shall not

permit any family to occupy a dwelling unit in any

project except pursuant to a written lease, which lease

shall contain all relevant provisions necessary to meet

the requirements of the Housing Act of 1937, as

amended, and the Annual Contributions Contract. The

local Housing Authority Management Handbook, pub

lished by the Public Housing Administration (now

Department of Housing and Urban Development),

states that: “ Whenever a family is admitted to oc

cupancy in a low-rent project, there is established a

landlord-tenant relationship with contractual obliga

tions to be fulfilled by both parties.” 6 It further

6 Part IV, Section 1, Paragraph 6a. The whole sub-paragraph

reads as follows: ‘ ‘ Whenever a family is admitted to occupancy

in a low-rent project there is established a landlord-tenant rela

tionship with contractual obligations to be fulfilled by both parties.

21

provides (Part IV, Section 1, Paragraph 6 d (l ) ) : “ It

is recommended that each local authority’s lease he

drawn on a month-to-month basis whenever possible.

This should permit any necessary evictions to be ac

complished with a minimum of delay and expense upon

the giving of a statutory notice to quit without stating

reasons for such notice.”

The HUD Circular of February 7, 1967 (App. IV,

p. 26a, Petitioner’s Brief) does not substantially change

this position. From a consideration of what that Cir

cular does not say, it is difficult to reach a logical

conclusion as to what it does say. It does not, for

example, purport to change the terms of the lease

provisions used by Housing Authorities, nor does it

purport to take away from the Housing Authority its

legal ability to evict by complying with the terms

of the lease and the pertinent provisions of the State

law relating to evictions. It does not deal with what

reasons are acceptable to HUD nor does it deal with

the reason that the term of the lease had expired as

an acceptable reason. It did not purport to change

the provisions of the Handbook above quoted. What

These obligations include many of those in standard landlord-

tenant leases, such as the provision by the landlord of designated

housing space and utilities and the payment of rent by the tenant.

But in low-rent public housing there are also the following special

obligations of a tenant to be reflected in the lease: (1) Furnish

the Local Authority, upon request, with information necessary to

determine eligibility for continued occupancy, the appropriate

rent and dwelling size required. (2) Pay an increased rent when

appropriate for its redetermined income or family composition.

(3) Transfer to a unit of appropriate size (at such time as the

Local Authority may designate) when a change in family compo- A,

sition warrants a different size dwelling. (4) Vacate if the family

becomes overincome or becomes subject to removal through vio

lation of any obligation of tenancy.”

22

HUD believes to be desirable or essential administra

tive practice by the Local Authority can be, and ap

parently is, entirely different from any legal require

ments pertaining to a judicial eviction proceeding.

This Circular certainly does not answer the question

as to what reasons must be shown, if any, by the

Housing Authority in an action in Court or an eviction

before the Housing Authority can prevail. It does

not require the Housing Authority to produce such

reasons in Court and deals only with a public rela

tions matter. Whether the phrase “ from this date”

used in the Circular was intended to refer both to

the activity of informing the tenant and to maintain

ing the records, it obviously appears in the only para

graph containing directive language.

The Petitioner (and perhaps HUD) seeks to es

tablish this document as a legal instrument, imposing

judicially enforceable duties upon local Housing Au

thorities; but cast in this role, it is fatally defective

for vagueness. Even the Petitioner’s Brief finds great

difficulty in interpretation, saying, in substance only,

that it amounts to a directive by HUD to the Courts

to apply constitutional “ due process” concepts to events

occurring before the institution of an eviction pro

ceeding in Court. By expressing a belief that a rea

son should be stated to the tenant without saying what

sort of reason would be required, it does not alter the

in-court requirements of proof in eviction proceedings,

and does not create an identifiable right enforceable by

the tenant. As the Petitioner’s Brief points out, “ The

Circular does not prohibit the use of month-to-month

leases under which the Authority may obtain a judg

ment of eviction on the sole basis of proper notice of

23

termination and without any allegation or proof of

cause.” (Petitioner’s Brief, p. 60.)7

Moreover, the Circular clearly does not say that a

Housing Authority cannot terminate at the end of

any term without cause as is provided in the lease.

Here, the tenant was well aware that the reason for

the eviction proceeding was that she was holding over

after the end of the term of her lease.

Circulars of this sort do not change the situation.

HUD might as well have issued a Circular requiring

officials of the Housing Authority to he kind and con

siderate of tenants when making demand upon the

tenants for the payment of rent. In such event, it is

doubtful that the tenant could assert, as a justification

for his nonpayment of rent, that an official of the

Housing Authority was not kind and considerate.

The use of the lease devise, a normal landlord and

tenant instrument, is a means of preventing the segre

gation of the tenants in public housing projects from

the society in which they live. The Federal Govern

ment, in establishing this program, has not provided

institutions in which all indigents may be inmates,

but has granted financial assistance to local housing

authorities organized under State law for the pur

pose of injecting into the housing rental market a

substantial number of decent low-rent dwelling units.

7 It is interesting: to note, moreover, that Petitioner’s Brief

refers to HUD’s Housing Authority Management Handbook as

being “ nonmandatory” and points to the language contained

therein— “ it is recommended” that leases be drawn on a month-

to-month basis—while on the other hand arguing that the Circular

of February 7, 1967, is mandatory even though it uses such lan

guage as “ we believe.”

24

This gives the Housing Authority no governmental

authority with respect to its tenants and no authority

greater than that possessed by any other landlord. The

interpretation and the enforcement of the lease is a

matter for the Courts. There is no Federal admin

istrative, statutory, or Constitutional requirement that

the term of such lease be for the duration of the life

time of the tenant or for the duration of his eligibility,

there being no guarantee that all members of the eligi

ble class shall have low-rent housing within a housing

authority project. As the Court said, in Brand v.

Chicago Housing Authority, supra: “ The fact that

the government selected plaintiff as the object of such

beneficence does not preclude it from determining at

a later time that the purpose of the act will be better

served by the selection of some other family of the

same or lower income class. To hold, as plaintiff

would have us do, that the mere selection of a tenant

carries with it a continuing right of tenure irrespec

tive of the terms and conditions upon which the tenancy

was founded, would not only contravene the purpose

and policy of the act, but would come near to destroy

ing it.”

i n .

THE CIRCULAR, WHATEVER IT MAY BE, DID NOT HAVE

APPLICATION TO EVENTS THAT OCCURRED BEFORE THE

ISSUANCE DATE OF THE CIRCULAR.

The relationship between the Respondent, Housing

Authority, and HUD is contractual. The United

States Housing Act of 1937, as amended, (42 USC

§ 1401, et seq.) recognizes that it was dealing in large

measure with local “ Public Housing Agencies” which,

in this case, was this Respondent, duly organized under

25

the provisions of the North Carolina “ Housing Au

thority Law. ’ ’ This State statute is its charter, giving

it powers and authorities and duties, including the

power to “ prepare, carry out and operate housing

projects” (G. S. 157-9; A. p. 13a, Petitioner’s Brief)

and to enter into contracts with the Federal Govern

ment pursuant to operating housing projects “ as the

Federal Government may require, including agree

ments that the Federal Government shall have the

right to supervise and approve the construction, main

tenance, and operation of such housing projeet. ” ( G. S.

157-23; A. p. 17a, Petitioner’s Brief.)

The United States Housing Act of 1937, as amended,

provided for the financial support of such Local Public

Housing Agency as the Housing Authority here by

entering into an Annual Contributions Contract with

such Local Agency. The Statute says: “ The Au

thority shall embody the provisions for such annual

contributions in a contract. . . .” (42 USC § 1410(a)).

Thus, HUD was to regulate matters, not by edict or

decree, but by the terms of an Agreement, some of

the provisions of which were established by require

ments of the Statute. For example, “ Every contract

for annual contributions shall provide that whenever,

in any year, the receipts of a Public Housing Agency

in connection with a low-rent housing project exceed

its expenditures (including debt service and charges)

an amount equal to such excess shall be applied or

set aside for application to purposes which in the

determination of the Authority will affect a reduction

in the amount of subsequent annual contributions.”

(42 USC § 1410(c)). It dealt with what the contract

should contain with respect to tenant selection.8

While HUD was given authority to make “ such rules

-and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the

provisions” of the statute, it could not thereby make a

rule or regulation that changed the basic concept of the

statute that the relationship between the parties (HUD

and the Housing Authority) is by contract. As we have

seen, the -State statute establishing the Housing Au

thority required obedience to HUD and its rulings

only by contract. The contract itself does not refer

to any manuals or circulars issued or to he issued by

P H A or by HUD. (See App., p. la .)

The Housing Act itself deals in considerable detail

with what the contents of the contract between HUD,

or the Federal authority, and the Local Housing Au

thority should be. It states that the contract should

provide that excess income of the Local Authority, over

and above its necessary operating expenses, should be

applied to debt service (42 USC § 1410(c)) ; that in

come limits of those eligible be approved by the Federal

authority; that admission policies be promulgated by

the Local Authority and approved by the Federal au

thority; that the Local Authority re-examine the in

842 USC § 1410(g) provides in part: “ Every contract for

annual contributions for any low-rent housing project shall pro

vide that— (1) the maximum income limits fixed by the public

housing agency shall be subject to the prior approval of the

Administration. . . . (2) the public housing agency shall adopt

and promulgate regulations establishing admission policies. . . .

(3) the public housing agency shall determine, and so certify to

the Administration, that each family in the project was admitted

in accordance with duly adopted regulations and approved in

come limits. . . . ”

27

come of tenants at least annually (42 U'SC § 1410(g) ) ;

that contracts should not he entered into with Local

Authorities that did not have certain tax exemptions

(42 US'O § 1410(h) ) ; and that the Local Authority not

be required to make payments for utilities different

from private persons and corporations (42 USC

§1410(i)). Nowhere, however, did it contain a re

quirement that the contract vest in HUD authority to

prescribe the terms and conditions of the lease to be

used by the Local Authority other than the tenant-

income feature, nor did the statute provide that HUD

by the contract should be vested with any authority

over the procedures of the Local Authority in giving

notice of termination of the term of the lease. The

Annual Contributions Contract between HUD and the

Local Authority contained no such requirements.

Even if this HUD Circular is construed to modify the

Annual Contributions Contract between HUD and the

Housing Authority and further modify the terms of

the lease between the Housing Authority and the Peti

tioner here, it does not follow that such modification

invalidated the notice by which the Petitioner was in

formed that her lease would not be renewed for another

term. These rights are property and contract rights

vested in the parties which the Petitioner seeks to have

changed ex post facto by the HUD directive. As Chief

Justice Marshall said, in United States v. Schooner

Peggy, 1 Cranch 103, 110, 2 L. Ed. 49 (1801) : “ It is

true that in mere private cases between individuals, a

Court will and ought to struggle hard against a con

struction which will, by a retrospective operation, affect

the rights of parties.. . . ” And, in Hamm v. Rock Hill,

379 US 306, 313, 85 S. Ct. 384 (1964), the Court, in

giving the reason for the retroactive rule applied in

28

that ease, quotes Chief Justice Hughes, saying: “ Pros

ecution for crimes is hut an application or enforcement

of the law, and, if the prosecution continues, the law

must continue to vivify it. ’ ’ This case at bar, of course,

is not a prosecution for a crime.

Recognizing that it has been held that the specific

prohibition of the Constitution relating to ex post facto

laws applies to statutes making acts criminal after the

fact, nevertheless this Court has recognized, as in

Lynch v. United States, supra, that contractual rights

may find protection under the prohibitions of the Fifth

Amendment. As Justice Brandeis said for the Court

in that case (Lynch v. United States, 292 US 571, 579) :

“ The Fifth Amendment commands that property be

not taken without making just compensation. Valid

contracts are property, whether the obligor be a private

individual, a municipality, a state, or the United States.

Rights against the United States arising out of a con

tract with it are protected by the Fifth Amendment.”

Here, rights have been vested by contract between

the Petitioner and the Housing Authority, by a con

tract between the Housing Authority and HUD, and

by a Judgment of the Courts of the State of North

Carolina.9

“ It is the policy of the United States to vest in the

local public housing agencies the maximum amount of

9 We are not, of course, asserting that the Congress could not by

statute change remedies available to landlords and tenants, even

after Judgment had been entered in the exercise of its general

powers to control rents in emergency situations, as was the ease

in Fleming v. Rhodes, 331 US 100, for the situation here is far

different than the one that existed in that case or in FH A v. The

Darlington, Inc., 358 US 84.

29

responsibility in tlie administration of the low-rent

housing program. . . . ” (United States Housing Act

of 1937, as amended, 42 USO § 1401.) This contem

plated implementing legislation on the State level. Ac

cordingly, the ‘ ‘ Housing Authority Law” of the State

of North Carolina provided that the very creation of a

local housing authority given by statute power to enter

into contracts with the Federal agencies would be a

matter for the consideration and determination by the

City Governing Body (G.<S. 157-4). As a preliminary

to entering into a contract with the Federal agencies,

the Housing Authority, once created, must enter into

a Cooperation Agreement with the City in which it is

located. The State statute has its own provisions gov

erning rentals and tenant selection. (G.S. 157-29.)

It is not unreasonable to say that at least one of the

reasons for this policy was to encourage localities to

participate in the program and thereby increase the

effectiveness of Federal expenditure in connection

therewith. The local control feature presumably had

a good deal to do with legislative acceptance of the

program at all levels. The concept that the occupants

of the dwelling units would be treated in the same way

as tenants in privately owned properties is not an un

reasonable feature of this concept. In view of this

policy, HUD has not undertaken by this Circular or

otherwise to ban the use of a lease in form and content

as was in effect between the Petitioner and the Housing

Authority in this case, nor has it undertaken by di

rective to state that specific reasons for terminating

the lease had to be established by the Housing Au

thority before notice of termination be given.

W e respectfully submit, therefore, that it is not un

constitutional for the State Court to construe the HUD

30

Circular of February 7, 1967, in the manner that it

did—that is to say, that the Circular, whatever its

prospective effect would be, did not act retroactively

to change the contractual relationship between the Peti

tioner and the Housing Authority as of the time the

lease was terminated, nor to render the eviction action

in the State Courts void.

CONCLUSION

We respectfully submit that the Judgment of the

State Court in this case is not oppressive to the Peti

tioner, does not deal with the Petitioner in a manner

different from other citizens, does not violate any Fed

eral law, and is not prohibited by any provision of the

Constitution, and, therefore, should be sustained.

It has not been shown to be necessary or socially

sound for this Court to endeavor to fashion special laws

for persons of Petitioner’s assumed economic status or

laws to be effective only when and where housing

shortages may exist. There is no evidence about such

matters in the record.

Respectfully submitted,

D aniel K . E dwards

W illiam Y. Manson

111 Corcoran Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Housing

Authority of the City of

Durham.

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX

Article V, Part Two, Annual Contributions Contract be

tween Local Authority and Public Housing Administration.

Sec. 501. Conveyance of Title or Delivery of Possession

in Event of Substantial Default

Upon the occurrence of a Substantial Default (as here

inafter in Sec. 506 defined) in respect to the covenants or

conditions to which the Local Authority is subject here

under, the Local Authority shall, at the option of the

PHA, either (a) convey to the PITA title to the Projects

as then, constituted if, in the determination of the PHA

(which determination shall be final and conclusive), such

conveyance of title is necessary to achieve the purposes

of the Act, or (b) deliver possession to the PHA of the

Projects as then constituted.

Sec. 502. Delivery of Possession in Event of Substantial

Breach

Upon the occurrence of a Substantial Breach (as here

inafter in Sec. 507 defined) in respect to the covenants

or conditions to which the Local Authority is subject here

under, the Local Authority shall, upon demand by the PHA,

deliver possession to the PHA of the Projects as then

constituted.

Sec. 503. Reconveyance or Redelivery

(A) If the PHA shall acquire title to or possession of

the Projects pursuant to Sec. 501 or Sec. 502, the PHA

shall reconvey or redeliver possession of the Projects, as

constituted at the time of such reconveyance or redelivery,

to the Local Authority (if it then exists) or to its suc

cessor (if a successor exists at the time of such reconvey

ance or such redelivery) as soon as practicable: (1) after

the PHA shall be satisfied that all defaults and breaches

with respect to the Projects have been cured and that the

Projects will, in order to fulfill the purposes of the Act,

thereafter be operated in accordance with the terms of

this Contract; or (2) after the termination of the obliga

tion of the PHA to make annual contributions available

unless there are any obligations or covenants of the Local

Authority to the PHA which are then in default.

(B) Upon any reconveyance or redelivery of the Proj

ects to the Local Authority the PHA shall account for

all monies which it has received or expended in connection

therewith. If during the period in which the PHA has

held title to or possession of the Projects, the PHA has

expended any of its funds in connection with development

or improvement of the Projects, the Local Authority at

the time of the reconveyance or redelivery of the Projects

shall pay to the PHA the amount of any such expenditures

with interest thereon at the PHA Loan Interest Rate to

the extent that the PHA has not theretofore been reim

bursed for such amount or interest: Provided, That if

the obligation of the PHA to make annual contributions

under this Contract has not terminated, and if any portion

of the amount which the Local Authority is obligated to

pay to the PHA upon such reconveyance or redelivery con

stitutes Development Cost, the PHA shall accept, in lieu

of payment in cash, an Advance Note or Permanent Note

for such portion.

(C) No conveyance of title and reconveyance thereof,

or delivery of possession and redelivery thereof, shall

exhaust the right to require a conveyance of title or de

livery of possession of the Projects to the PHA pursuant

to Sec. 501 or Sec. 502 upon the subsequent occurrence of

a Substantial Default or a Substantial Breach, as the case

may be.

Sec. 504. Continuance of Annual Contributions

(A) The PHA hereby determines that Sec. 501 and Sec.

503 of this Contract include provisions that are in ac

cordance with subsection (a) of Sec. 22 of the Act.

(B) Whenever the annual contributions, pursuant to

this Contract, have been pledged by the Local Authority

as security for the payment of the principal and interest

on the Bonds or other obligations issued pursuant to this

Contract, the PHA (notwithstanding any other provisions

of this Contract) shall continue to make the annual con

tributions provided in this Contract available for the Proj

ects so long as any of such Bonds or obligations remain

outstanding; and, in any event, such annual contributions

shall in each year be at least equal to an amount which,

together with such income or other funds as are actually

available from the Projects for the purpose at the time

such annual contribution is made, will suffice for the pay

ment of all installments, falling due within the next suc

ceeding twelve months, of principal and interest on the

Bonds or other obligations for which the annual contribu

tions provided for in this Contract have been pledged as

security: Provided, That in no case shall such annual

contributions be in excess of the maximum sum specified

in this Contract, nor for longer than the remainder of

the maximum period fixed by this Contract.

Sec. 505. Rights and Obligations of PHA During Tenure

Under Sec. 501 or Sec. 502

(A) During any period in which the PHA holds title

to or possession of the Projects pursuant to Sec. 501 or

Sec. 502, it shall (1) exercise diligence in the protection

of the Projects, (2) complete the development of any

Project or part thereof which is substantially completed

at the time of acquisition by the PHA of such title or

possession, as nearly as practicable in accordance with

the provisions of this Contract, and (3) operate all com

pleted Projects or parts thereof (including Projects or

parts thereof which may be completed by the PHA)

as nearly as practicable in accordance with the provisions

of this Contract, including the carrying of insurance as

described in subsections (A) and (B) of 'Sec. 305. The

4a

PHA, at its option, may complete the development of any

Project or any part thereof.

(B) During any period in which the PHA holds title

to or possession of the Projects pursuant to Sec. 501

or Sec. 502, it may, in the name of and on behalf of the

Local Authority or in its own name and on its own behalf,

exercise any or all of the rights and privileges of the Local

Authority pursuant to this Contract and perform any or

all of the obligations and responsibilities of the Local

Authority pursuant to this Contract.

(C) Neither the conveyance of title to or the delivery

of possession of the Projects by the Local Authority pur

suant to .Sec. 501 or Sec. 502, nor the acceptance of such

title or possession by the PHA, shall abrogate or affect

in any way any indebtedness of the Local Authority to

the PHA arising under this Contract, and in no event shall

any such conveyance or delivery or any such acceptance

be deemed to constitute payment or cancellation of any

such indebtedness.

Sec. 506. Definition of Substantial Default

For the purposes of this Contract a “ Substantial De

fault” is defined to be the occurrence of any of the follow

ing events:

(1) If any Project shall cease to be exempt from all

real and personal property taxes levied or imposed by

the State, city, county, or other political subdivisions, or

if the Local Authority without the approval of the PHA

shall make or agree to make any payments in lieu of taxes

in excess of those provided in the Cooperation Agreement;

or

(2) If the Local Authority shall default in the observance

of any of the provisions of Sec. 313, or if any Project shall

be acquired by any third party in any manner including

a bona-fide foreclosure under a mortgage or other lien

held by a third party; or

(3) If the Local Authority shall fail to furnish certifi

cation as to compliance with the provisions of Sec. 16 (2)

of the Act relating to the payment of prevailing salaries

and wages as required by subsection (C) of Sec. 419; or

(4) If the Local Authority shall (a) refuse or neglect

to issue and sell its Bonds in the amounts and at the time

required by this Contract, or (b) fail to maintain the low-

rent character of each Project as required by Sec. 202,

or (c) fail to prosecute diligently the reconstruction,

restoration, or repair of any Project as required by Sec.

214; and such refusal, neglect, or failure is not remedied

within three months after the FHA has notified the Local

Authority thereof; or

(5) If the Local Authority is in default in the per

formance or observance of any of the provisions of this

Contract or of the Act, which default (except for the pro

visions of Sec. 504) would have the effect of preventing

the PHA from paying or making available the annual con

tributions provided for in this Contract; or

(6) If the Local Authority shall abandon any Project,

or if the powers of the Local Authority to operate the

Projects in accordance with the provisions of this Contract

are curtailed or limited to an extent which will prevent

accomplishment of the objectives of this Contract.

Sec. 507. Definition of Substantial Breach

For the purposes of this Contract a “ Substantial Breach”

is defined to be the occurrence of any of the following

events:

(1) If the Local Authority in the development of any

Project has1 violated, or takes any action which threatens

to violate, (a) any of the provisions of Part One of this

Contract relating to the limitation on the cost for con

struction and equipment of such Project, or (b) any of

the provisions of subsection (F) of Sec. 404; or

(2) If the Local Authority, in violation of subsection

(H) of Sec. 407, has (a) at any time after the end of

the Initial Operating Period for any Project incurred any

Operating Expenditures with respect to such Project ex

cept pursuant to and in accordance with an approved

Operating Budget for such Project, or (b) during any

Fiscal Year or other budget period incurred with respect

to any Project total Operating Expenditures in excess

of the amount therefor shown in an approved Operating

Budget (including revisions thereof) governing such Fiscal

Year or other budget period; or

(3) If the Local Authority has violated any of the pro

visions of subsection (C) or (D) of (Sec. 401; or

(4) If there is a breach of any of the provisions relating

to the payment of prevailing salaries and wages which are

required by this Contract to be included in contracts of

the Local Authority in connection with the Projects; and

such breach is not remedied or appropriate action to remedy

the same initiated by the Local Authority within thirty

days after the PHA has notified the Local Authority of

such breach, or if such remedial action is not thereafter

diligently prosecuted to conclusion; or

(5) If the Local Authority shall fail to prosecute dili

gently the development of each Project as required by

subsection (B) of Sec. 102; and such failure is not remedied

within three months after the PHA has notified the Local

Authority of such failure; or

(6) If, through any action, failure to act, or fault of

the Local Authority, its officers, agents, or employees (in

cluding the Fiscal Agent), there shall be a default in the

payment of any installment of the principal of or interest

on any of the Bonds when the same shall become due

(whether at the maturity thereof or by call for redemption

or otherwise); and such default shall continue for a period

of sixty days; or

7a

(7) If there is a flagrant default or breach by the Local

Authority in the performance or observance of any term,

covenant, or condition of this Contract; or

(8) If there is any default or breach by the Local Au

thority in the performance or observance of any term,

covenant, or condition of this Contract other than the

defaults or breaches enumerated in Sec. 506 or in sub

sections (1) through (7) of this Sec. 507; and if such

default or breach has not been remedied within thirty

days (or such longer period as may be set by the PH A)

after the PHA has notified the Local Authority thereof.

Sec. 508. Other Defaults or Breaches, and Other Remedies

(A) Neither the provision of the special remedies set

forth in Sec. 501 and Sec. 502 in the event of a Substantial

Default or a Substantial Breach, as the case may be, nor

any exercise thereof, shall affect or abrogate any other

remedy which may be available to the PHA in the event

of a Substantial Default, Substantial Breach, or any other

default or breach; and the PHA may, during any period

in which it holds title to or possession of the Projects

pursuant to Sec. 501 or Sec. 502, exercise any other remedy

available to it. Neither the definition of certain defaults

or breaches as Substantial Defaults or Substantial

Breaches, nor the provision of special remedies therefor,

shall be deemed to constitute an agreement that any other

type of default or breach shall be considered insignificant

or without remedy.

(B) If the Local Authority shall at any time be in

default or breach, or taike any action which will result

in a default or breach, in the performance or observance

of any of the terms, covenants, and conditions of this

Contract, then the PHA shall have, to the fullest extent

permitted by laiw (and the Local Authority hereby confers

upon the PHA the right to all remedies both at law and

in equity which it is by law authorized to so confer) the

right (in addition to any rights or remedies in this Con