Marek v Chesny Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1984

27 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Marek v Chesny Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent, 1984. 2cb86b08-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bac27d13-c6fa-4352-903b-fce400575cf3/marek-v-chesny-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

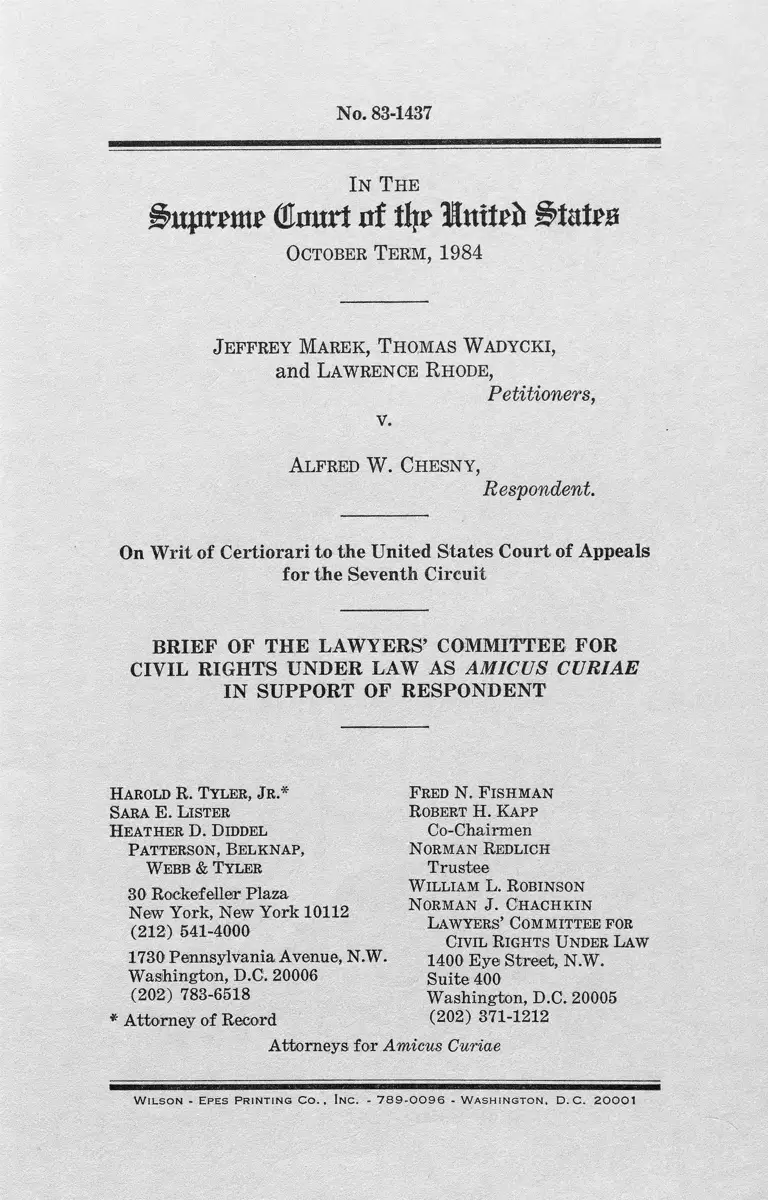

No. 83-1437

In The

(tart itf % Ittttrfo l̂ tatr#

October Term, 1984

Jeffrey Marek, Thomas Wadycki,

and Lawrence Rhode,

Petitioners,

v.

Alfred W. Chesny,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Seventh Circuit

BRIEF OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

Harold R. Tyler, Jr.*

Sara E. Lister

Heather D. Diddel

Patterson, Belknap,

Webb & Tyler

30 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, New York 10112

(212) 541-4000

1730 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 783-6518

* Attorney of Record

Fred N. F ishman

Robert H. Kapp

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

W i l s o n - Ep e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether Rule 68 requires that a prevailing party in

a civil rights action brought under 42 IJ.S.C. § 1983 be

denied attorneys’ fees for time expended on the case

after rejecting a settlement offer more favorable than

the amount subsequently recovered after trial.

(i)

QUESTION PRESENTED ------------ -------- ------------ i

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ________~ 1

STATEMENT ........... ... ....... ..... .. ............... ....... ............ 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........... ....... - ................. 4

ARGUMENT ....... ....... ........ .............. ........... - 5

I. THE “ COSTS” SPECIFIED IN RULE 68 DO

NOT INCLUDE ATTORNEYS’ FE ES.......... . 5

II. CONGRESS DID NOT INTEND FEE SHIFT

ING TO EXPAND THE DEFINITION OF

“ COSTS” IN RULE 6 8 ....... ............. ................ . 10

III. THE EXERCISE OF RIGHTS GUARANTEED

BY CONGRESS THROUGH SECTION 1983

WILL BE IMPERMISSIBLY CHILLED IF

RULE 68 COSTS ARE INTERPRETED TO

INCLUDE ATTORNEYS’ FEES ____________ 16

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CONCLUSION _ 20

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Alyeska Pipeline Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421

U.S. 240 (1975) .... ............ ........ ....... .............. . 6,7,9

Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247 (1978) _________ 16, 17

Chesny v. Marek, 547 F. Supp. 542 (N.D. 111.

1982) ; 720 F.2d 474 (7th Cir. 1983).... ... ........ 3, 19

Day v. Woodworth, 54 U.S. (13 How.) 363

(1851) ................... ........................... ...................... 7, 8

Delta Airlines v. August, 450 U.S. 346 (1981).... 6 ,13n

Dowdell v. City of Apopka, Florida, 698 F.2d 1181

(11th Cir. 1983) ____________ ___ ____ ________ 8, 16

Greenwood v. Stevenson, 88 F.R.D. 225 (D.R.I.

1980) .............. ....... ......................... ..................... . g

Hairline Creations, Inc. v. Kef alas, 664 F,2d 652

(7th Cir. 1981) .................................... ............. 8

Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S, 1 (1973) .............. .......... . 15

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978) ....... ....... . 9

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225 (1972)........... 16

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ____________ __________________ _______ 15

Pigeaud v. McLaren, 699 F.2d 401 (7th Cir. 1983).. 8

Roadway Express, Inc. v. Piper, 447 U.S. 752

(1980) ------- ------------------------------- ---- ------------... 8 ,14n

Sioux County v. National Surety Co., 276 U.S, 238

(1928) ....... ..... ................ ....... ....... .................... . g

White v. New Hampshire Department of Employ

ment, 629 F.2d 697 (1st Cir. 1980), rev’d on

other grounds, 455 U.S. 445 (1982) ...... ........... 8

Statutes:

7 U.S,C. § 210( f ) ...................... .............. . n

7 U.S.C. § 2305(a) ..... ........ ' 13n

15 U.S.C. § 15 ...................................... .................... ll,12n

15 U.S.C. § 77k (e).... ............ ........ ............. ............ n> 12n

15 U.S.C. § 7 8 i(e )............... .... ............................... 12n

15 U.S.C. §1640 (a) ........... ................. ................. . 14

17 U.S.C. § 505 ---------------------------- ----- ----- , l l n, l 2n, 13n

28 U.S.C. § 1920 ______ 4 8 9

28 U.S.C. § 1927 .. . .... ........... ................... . ’ 12n

28 U.S.C. § 2072 ............. ........................ ......... ...... ' 4

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

2:9 U.S,C. § 107 .................. .......... ..... .............. ......... lln

29 U.S.C. § 216(b ) ............................ .......... ................ 14

42 U.S.C. § 1983....................... .................. ......... ......passim

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ........ ..................................... ........... passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000a,-3 ( b ) ............ ...... ...................... . 14n

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (k) .................... ..... ......... .... . 14n

42U.S.C, § 7604....................... ....... .................... ....... 14

49 U.S.C. § 11705.... ............... ..... .......... .......... 1 On, 12n

Interstate Commerce Act, eh. 104, 24 Stat. 379

(1887) ....................... ............... ....... ..................... lOn

Rules of Civil Procedure:

Buie 11 -------------- ------- ------ ------ --------- ------ ------- .6n, lOn

Rule 1 6 ( f )____ ____ _____________ _____ ___ ____ 6n

Rule 26(g) _________________ __ ________________ 6n, lOn

Rule 30(g) _____ ________________________________6n, lOn

Rule 37 .------------------------- ---------------- ----- ---------6n, 9, lOn

Rule 41 ______ ______ ________ ____ ___ ________ 5n, lOn

Rule 54(d) --- ------- ------ ------------ --------------- --------- passim

Rule 55(b)..________ ___ ___ ______ ______________ 5n

Rule 56(g) ------------------------ --------------- ------- ----6n, 9, lOn

Rule 65 ( c ) ........... .................................. ......... ........... 5u

Rule 68 — ...... .................................... ........ ........... .passim

Rule 71A(1)______ ____________________ ________ 5n

Rule 76(c) ............. ........... ....... ......... ................ . 5n

Rules of Appellate Procedure:

Rule 38 ...... ........ ........ ................................................ 6n

Legislative Materials:

128 Cong. Ree. S4878 (daily e,d. May 11, 1982).... 18n

H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976).. 14n

S, Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976),

reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

Treatises and Articles:

Amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Proce

dure, 85 F.R.D. 521 (1980)................. .......... . i8n

Comment, Taxation of Costs in Federal Courts—

A Proposal, 25 Am. U.L. Rev. 877 (1976)....... 7n

vi

Committee on Legal Assistance, Counsel Fees in

Public Interest Litigation, 39 Rec. A.B. City

N.Y. 300 (May/June 1984) .............................. I6n

Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure,

Judicial Conference of the United States, Pre

liminary Draft of Proposed, Amendments to the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (1984) ______ lOn

McCormick, Counsel Fees and Other Expenses of

Litigation as an Element of Damages, 15 Minn.

L. Rev. 619 (1931) ......................................... . gn

Note, Costs—Problems in the Allowance of Attor

neys’ Fees in America, 21 Va. L, Rev. 920 (1935).. 9n

Note, Distribution of Legal Expenses Among Liti

gants, 49 Yale L.J. 699 (1940) ........................gn, lln

Note, The Impact of Proposed Rule 68 on Civil

Rights Litigation, 84 Colum. L. Rev. 719

( 1984) ........................................................................................................ 7n , 8

Note, The Offer of Judgment Rule in Employment

Discrimination Actions: A Fundamental Incom

patibility, 10 Golden Gate U.L. Rev. 963 (1980).. 17n

Note, Promoting the Vindication of Civil Rights

Through the Attorney’s Fees Awards Act, 80

Colum. L. Rev. 346 (1980) ____ ________ _____ 7n

Payne, Costs in Common Law Actions in the Fed

eral Courts, 21 Va. L. Rev. 397 (1935) .........._.9n, 12n

Preliminary Draft of Proposed Amendments, 98

F.R.D. 337 (1983) .................... ......................... 9

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

I n T h e

Bm rm t (Urntrt 0! tkf Hrntdt

October Term, 1984

No. 83-1437

Jeffrey Marek, Thomas Wadycki,

and Lawrence Rhode,

Petitioners,

Alfred W. Chesny,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Seventh Circuit

BRIEF OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE 1

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

(the “ Committee” ) was organized in 1963 at the re

quest of the President of the United States to involve

private attorneys in the national effort to protect the

civil rights of all Americans. The Committee has had the

assistance of well over a thousand members of the pri

vate bar in numerous cases that have addressed the

problems of minorities and the poor. As a frequent liti

1 Letters, from counsel for the parties consenting to the submis

sion of this brief have been filed with the Clerk.

2

gant in cases brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and other

remedial statutes which contain fee-shifting provisions,

the Committee will be directly affected by the decision

in this case.

The issue presented here is whether “costs” under Fed.

R. Civ. P. 68 (“Rule 68” ) include attorneys’ fees where

the statute under which the case is brought provides

that a prevailing plaintiff may receive attorneys’ fees.

Such fee-shifting statutes exist because, in each substan

tive area to which they apply, Congress has determined

that the public interest is served by awarding attorneys’

fees to successful litigants. The Committee has had first

hand experience with such fee-shifting provisions, and

with the kinds of settlement offers likely to be made in

civil rights cases. The Committee believes that the inter

pretation of Rule 68 urged by petitioners would have a

direct and harmful effect on civil rights plaintiffs and

other plaintiffs who serve as “private attorneys general”

and thus help to advance national policy. The Commit

tee files this brief in support of respondent urging af

firmance of the judgment below.

STATEMENT

Respondent Alfred W. Chesny filed suit in 1979 under

42 U.S.C. § 1983 against petitioners, police officers of

the Village of Berkley, Illinois, seeking damages because

of petitioners’ allegedly unlawful shooting of his son.

On November 5, 1981, petitioners made an offer of judg

ment under Rule 68 “ for a sum, including costs now

accrued and attorney’s fees, of ONE HUNDRED THOU

SAND ($100,000) DOLLARS.” Joint Appendix at A-17.

The respondent refused the offer and the case proceeded

to trial. On May 11, 1982, the jury returned a verdict

in favor of respondent in the amount of $60,000. Re

spondent then moved under the Civil Rights Attorney’s

3

Fees Awards Act of 1976 ( “ Fees Awards Act” ), 42

U.S.C. § 1988, for a fee award.2

The district court held that Rule 68 limited respond

ent’s fee award to the time and effort expended prior

to petitioners’ offer of judgment. Rule 68 provides that

if a plaintiff receives less after trial than the defendant’s

offer of judgment, then plaintiff “must pay the costs

incurred after the making of the offer.” The district

court interpreted “costs” under Rule 68 to include at

torneys’ fees where the statute under which the action

was brought authorizes an award of attorneys’ fees, as

part of the costs, to a prevailing party.

The Seventh Circuit, in an opinion by Judge Posner,

reversed on the ground that Rule 68 cannot be inter

preted to defeat Congress’ policy to award fees to pre

vailing plaintiffs where those plaintiffs acted as pri

vate attorneys general. It emphasized that civil rights

plaintiffs

should not be deterred from bringing good faith ac

tions to vindicate fundamental rights by the prospect

of sacrificing all claims to attorney’s fees for legal

work at the trial if they wTin, merely because on the

eve of trial they turned down what turned out to be

a more favorable settlement offer.

Chesny v. Marek, 720 F.2d 474, 479 (7th Cir. 1983).

The Seventh Circuit found that although Rule 68 was

clearly intended to encourage settlements, and thus to

conserve the resources of both the parties and the courts,

it could not have been intended to alter substantive con

2 The United States has emphasized in its amicus brief that sub

stantial attorneys’ fees were generated in this case. See e.g., Brief

of United States at 3. The size of the fee requested by respondent

after trial is irrelevant to' this Court’s determination of the issues

before it. Nothing in the record, however, suggests that the fees

requested were excessive or inconsistent with the work required to

bring the case to trial.

4

gressional policies., such as those underlying the Fees

Awards Act. The Rules Enabling Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2072,

provides that the Federal Rules “ shall not abridge, en

large or modify any substantive right.” Accordingly, the

court held that Rule 68 must be interpreted consistently

with the substantive policies of the Fees Awards Act.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Petitioners’ interpretation of Rule 68 would signifi

cantly enlarge the role and effect of settlement offers to

the serious detriment of civil rights plaintiffs. Any

claim that “ costs” under Rule 68 include attorneys’ fees

contravenes basic rules of statutory construction and legal

precedent, and critically undermines federal legislation

enacted to protect fundamental national policies.

Rule 68 provides that a party may be held responsible

for “ costs” under specified circumstances. “ Costs” are

not defined in the Federal Rules, although seven Rules

provide for their award. The courts have consistently

interpreted “costs” as used in the Rules to include those

costs set out in 28 U.S.C. § 1920 and generally awarded

to the prevailing party under the “American rule,” which

does not permit the award of attorneys’ fees. Those Fed

eral Rules which permit courts to award attorneys’ fees

as a sanction characterize such fees as “ expenses,” not

“ costs.” “Costs” should be defined consistently in all the

Federal Rules which authorize their award.

Petitioners would interpret costs under Rule 68 differ

ently depending on whether the statute under which the

action is brought provides for an award of attorneys’ fees

to a prevailing plaintiff. Petitioners argue that if such

an award is authorized by statute, the “costs” which be

come the responsibility of the prevailing plaintiff under

Rule 68 include such fees. Under this view, the goals

Congress sought to achieve with fee-shifting would be

negated by Rule 68 whenever a defendant makes an offer

5

of judgment which proves greater than the sum awarded

plaintiff after trial.

The definition of “ costs” under Rule 68 should not ex

pand or contract depending on the statutory basis for

suit. Instead, fee shifting is appropriate where author

ized by a substantive statute, even if Rule 68 may other

wise cut off the plaintiff’s reimbursement for costs. Any

other conclusion would be contrary to Congress’ intention

in providing for fee-shifting in civil rights cases, and

would have a seriously chilling effect on plaintiffs seeking

injunctive or other nonmonetary relief. Any interpreta

tion of Rule 68 that greatly increases the risks of litiga

tion to such plaintiffs provides defendants in civil rights

cases with a new and effective weapon to frustrate meri

torious actions in a manner never intended by Congress.

ARGUMENT

I. THE “COSTS” SPECIFIED IN RULE 68 DO NOT

INCLUDE ATTORNEYS’ FEES

The term “ costs” as used in the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure should be given its common meaning, and

should be interpreted consistently throughout the Rules.

Nowhere in the Rules are “costs” defined to include at

torneys’ fees within the taxable costs of litigation.3

Rule 68 uses the term “costs” in the same way as other

Rules which permit costs to be taxed to1 one party or an

3 The current RuleiS which provide for the award of costs under

certain circumstances are Rule 41(d) (Costs of Previously Dis

missed Action); Rule 54(d) (Judgments; Costs); Rule 55 (b)(1 )

(Judgment by Default) ; Rule 65(c) (Security) ; Rule 68 (Costs) ;

and Rule 71A(Z) (Costs in Condemnation Actions), which quotes

a Justice Department manual for use in condemnation suits to the

effect that “normal expenses,” including the fees of counsel ap

pointed to represent absent defendants so that quiet title may be

transferred, are to be charged to the government directly but “not

taxed as costs.” Rule 76(c) (Judgment of the District Judge on

the Appeal Under Rule 73(d) and Costs) also provides for award

of costs.

other upon the occurrence of a particular event. “ [T]he

plain language of Rule 68,” Delta Airlines v. August,

450 U.S. 346, 351 (1981), mandates that “costs” be in

terpreted in Rule 68 consistently with the other Federal

Rules.

Whenever attorneys’ fees are mentioned in the Rules

they are included as a sanction which may be invoked to

punish noncompliance with a particular rule. Attorneys’

fees are uniformly described within the Rules as an ele

ment of expenses.4 5 This treatment of attorneys’ fees is

consistent with the characterization of attorneys’ fees in

the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, and with the

American rule that the costs to be awarded to a prevail

ing party do not include attorneys’ fees.®

Moreover, such a construction is consistent with this

Court’s recent analyses of the interplay between Rules

54(d) and 68. Under Rule 54(d), a prevailing plaintiff

“presumptively” will obtain costs. Delta Airlines, 450

U.S. at 352. The “ costs” to be taxed under Rule 54(d)

do not include attorneys’ fees, which become payable

by a losing defendant only pursuant to applicable stat

ute. Alyeska Pipeline Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S.

240 (1975).6 The Court’s mandate in Delta Airlines that

4 The current Federal Rules which provide for the award of “ex

penses . .. ., including a reasonable attorney’s fee,” are Rules 11;

1 6 (f) ; 2 6 (g ); 3 0 (g ); 3 7 (a )(4 ), (b )(2 ), (c), (d) and ( g ) ; and

56(g).

5 The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure allow award o f at

torneys’ fees under Rule 38, “Damages for Delay.” The Advisory

Committee Notes to that Rule state that “ damages, attorney’s fees,

and other expenses incurred by an appellee” may be awarded if an

appeal is found to be frivolous.

6 While Rule 54(d) makes liability for costs “a normal incident

of defeat, Delta, Airlines, 450 U.S. at 352, it also provides that

courts may otherwise direct, and that exceptions to the Rule exist

where “express provision therefor is made either in a statute of the

United States or in these rules,” The flexibility of Rule 54(d) is not

found in Rule 68. Rule 68 makes no provision for the exercise of

6

7

the Federal Rules be interpreted consistently with one

another clearly requires that the taxable “ costs” under

Rule 68, as under Rule 54(d) and other Rules, exclude

attorneys’ fees.

Both Congress and the courts have treated attorneys’

fees differently from other costs and expenses of litiga

tion. Just as doctors’ fees are a major component of the

cost of medical care, so attorneys’ fees are a large part

of the costs of litigation.7 Nonetheless, the general (or

“American” ) rule is that each litigant ordinarily must

bear its own attorneys’ fees unless there is. express statu

tory authorization to the contrary. The American rule,

which is contrary to the preexisting common law policy,

was intended to equalize the burden of litigation, making

it more likely that litigants without deep pockets would

be able to assert their rights in court. With narrowly

defined exceptions,8 this Court has made clear that Con

gress alone has the authority to create and define the

situations in which a reallocation of attorneys’ fees serves

a public purpose. Alyeska Pipeline Co. v. Wilderness

Society, 421 U.S. at 260, 262 (1975).

Costs are in an altogether different category than at

torneys’ fees. This Court recognized as early as. 1851

that “the legal taxed costs are far below the real ex

penses incurred by the litigant.” Day v. Woodworth, 54

discretion by the court, nor does it indicate that the “costs” which

may be reallocated to encourage settlement should be interpreted

differently depending on the statute involved.

7 See, e.g., Note, The Impact of Proposed Rule 68 on Civil Rights

Litigation, 84 Colum. L. Rev. 719, 720 (1984) (attorneys’ fees are

“ by far the largest expense of litigation” ) ; and Comment, Taxation

of Costs in Federal Courts—A Proposal, 25 Am. U.L. Rev. 877, 881

(1976) (attorneys’ fees “are often the single, largest expense of

litigation” ) .

8 The principal exceptions involve bad faith and the existence of

“common funds.” See Note, Promoting the Vindication of Civil

Rights Through the Attorney’s Fees Awards Act, 80 Colum. L. Rev.

346,349 (1980).

8

U.S. (13 How.) 363, 372 (1851). “Costs” that were

awarded to the successful litigant did not include attor

neys’ fees. As the Court held, it was not the American

practice “ to indemnify the plaintiff for counsel-fees and

other real or supposed expenses over and above taxed

costs.” Id. at 371-72 (emphasis added). See also Sioux

County v. National Surety Co., 276 U.S. 238 (1928),

where this Court held that an attorney’s fee award au

thorized by state statute was not the same as “costs in

the ordinary sense of the traditional arbitrary and small

fees . . . allowed to counsel. . . .” Id. at 243.

The federal courts have consistently interpreted “ costs”

under Rule 68, as under the other Federal Rules, to refer

to taxable costs as those costs are defined in 28 U.S.C.

§ 1920. See White v. New Hampshire Department of

Employment, 629 F.2d 697, 702-03 (1st Cir. 1980), rev’d

on other grounds, 455 U.S. 445 (1982); Greenwood v.

Stevenson, 88 F.R.D. 225, 231-32 (D.R.I. 1980). See also

Pigeaud v. McLaren, 699 F.2d 401, 403 (7th Cir. 1983);

Note, The Impact of Proposed Rule 68 on Civil Rights

Litigation, 84 Colum. L. Rev. 719, 721 n.9 (1984). Sec

tion 1920 was enacted to standardize the treatment of

costs in federal litigation, Roadway Express, Inc. v.

Piper, 447 U.S. 752, 759-61 (1980), and constitutes the

“modern version” of the 1853 Fee Act, 10 Stat. 161,

whose “ explicit purpose . . . was to limit the award of

costs to specific itemized expenses related to the mechanics

of bringing a case before the courts.” Dowdell v. City of

Apopka, Florida, 698 F.2d 1181, 1189 n.12 (11th Cir.

1983). In Hairline Creations, Inc. v. K ef alas, 664 F,2d

652, 655 (7th Cir. 1981), the court referred to Section

1920 as the standard by which to assess costs on a Rule

54(d) motion since that Rule, like Rule 68, does not de

fine costs. Thus, the “ rule implicitly embodies the Amer

ican rule, whereby parties ordinarily cannot recover at

torneys’ fees as costs.” Id. at 655 (citation omitted).'8 9

8 The following articles, published almost contemporaneously

with the enactment of the Federal Rules in 1938, illustrate the

9

As the Court stated in Alyeska, Congress has not “re

tracted, repealed, or modified the limitations on taxable

fees contained in the 1853 statute and its successors.” 421

U.S. at 260 (footnote omitted). Those limitations are

now contained in Section 1920. By not amending that

provision to encompass attorneys’ fees, Congress has im

plicitly confirmed that, as a general rule, taxable costs

are those delineated in Section 1920. Where Congress has

deemed it appropriate to provide attorneys’ fees, it has

made “ specific and explicit provisions for the allowance

of attorneys’ fees under selected statutes granting or pro

tecting various federal rights.” Id. (citation omitted).

Similarly, this Court has referred to attorneys’ fees

that may be awarded under the Federal Rules as part of

expenses, not costs. In Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678

(1978), the Court noted that it was within the power of

an equity court to award attorneys’ fees “against a party

who shows bad faith” and that the use of such Fed

eral Rules as 37(a) (4) and 56(g) for this purpose “vin

dicates judicial authority without resort to the more

drastic sanctions available . . . and makes the prevailing

party whole for expenses caused by his. opponent’s ob

stinacy.” Id. at 689 n.14 (emphasis added).

Finally, it is significant that the Advisory Committee

of the Judicial Conference of the United States has con

sistently characterized attorneys’ fees as expenses, not

costs. The Committee’s 1983 proposal to revise Rule 68

to encourage settlements would have provided for the

shifting of costs “and expenses, including any reasonable

attorneys’ fees.” Preliminary Draft of Proposed Amend-

applicability of the American rulei that attorneys’ fees are not costs

to be shifted from one party to another unless a statute so provides.

McCormick, Counsel Fees and Other Expenses of Litigation as an

Element of Damages, 15 Minn. L. Rev. 619 (1931); Payne, Costs in

Common Law Actions in the Federal Courts, 21 Va. L. Rev. 397

(1935) ; Note, Distribution of Legal Expenses Among Litigants, 49

Yale L.J. 699 (1940) ; Note, Costs—Problems in the Allowance of

Attorneys’ Fees in America, 21 Va. L. Rev. 920 (1935),

10

ments, 98 F.R.D. 337, 362, 365 (1983) (emphasis

added).10 11 Both the original draft and a recent revision

provide expressly for awards of attorneys’ fees under

Rule 68 so that settlements will be encouraged. The Com

mittee’s draft amendments would define attorneys’ fees

as part of expenses, consistently with the long-standing

interpretation of the rest of the Rules.

II. CONGRESS DID NOT INTEND FEE-SHIFTING

STATUTES TO1 EXPAND THE DEFINITION OF

“COSTS” IN RULE 68

Both petitioners and the United States argue that Con

gress must have known in 1938, when the Federal Rules

were adopted, that costs under Rule 68 would include

attorneys’ fees because Congress had already provided that

in some circumstances attorneys’ fees could be reallocated

as part of the costs of an action. This argument is un

tenable. In none of the fee-shifting statutes that predate

the Federal Rules did Congress provide simply for the

shifting of “ costs” without clearly stating that those costs

—unlike taxable costs— included attorneys’ fees.

The pre-1938 statutes that provided for fee-shifting

served a variety of public purposes1:1 and did not use

10 The draft was subsequently withdrawn and replaced by a more

recent revision. The current draft, now under consideration by the

Advisory Committee, proposes that, costs and expenses, including

reasonable attorneys’ fees, be shifted as a sanction that may be

imposed by the court “as a means of facilitating the efficient opera

tion of the litigative process.” The Rules cited by the Committee’s

comments as applying the same principle are those Rules that spe

cifically refer to attorneys’ fees: Rule 3 7 (b )(2 ), (c) and ( d ) ;

Rules 11 and 26(g) ; Rule 56(g) ; Rule 30 (g) ; and Rule 41(a) (2).

Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure, Judicial Conference

of the United States, Preliminary Draft of Proposed Amendments

to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 12-19 (1984).

11 The Interstate Commerce Act, (the “Act” ), c. 104, '§8; 24

Stat. 379, 382 (1887), (cited by the government in its brief in

the Act’s codified version as 49 U.S.C. § 11705(d) (3) and as post-

1938) contains an early example of feei-shifting to encourage

private enforcement of safety standards for the public bene

11

identical language, or provide for uniform fee shifting if

the plaintiff prevailed. Formulations, and the amount of

discretion the courts were given in determining whether

to award any attorneys’ fees, varied with each statute.

For example, the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921,

7 U.S.C. § 210(f), states that “ [i] f the petitioner finally

prevails, he shall be allowed a reasonable attorney’s fee

to be taxed and collected as a part of the costs of the

suit.” The Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 15(a), provides that

prevailing plaintiffs “shall recover . . . the cost of suit,

including a reasonable attorney’s fee.” The Securities

Act of 1933, 15 U.S.C. § 77k (e), provides that the court

may “ require an undertaking for the payment of the

costs of such suit, including reasonable attorney’s fees”

and that if the court believes the suit or defense to have

been without merit, the prevailing party may receive

costs “ in an amount sufficient to reimburse him for the

reasonable expenses incurred by him.” These and other

statutes cited by petitioners and the United States12 sug

gest only that attorneys’ fees were considered part of

“ the cost of suit” to be shifted when Congress elected to

do so to achieve certain goals. These statutes do not,

however, indicate any congressional intention to define

fit. The Act provided that “such common carrier shall be liable

to the person . . . injured thereby for the full amount of damages

. . . together with a reasonable counsel or attorney’s fee.” Similarly,

under Section 40 of the Copyright Act of 1909, 35 Stat. 1084, now

codified at 17 U.S.C. § 505, the court in its discretion “may award”

such attorneys’ fees to a prevailing party “as part of the costs.”

Congress intended there to compensate the prevailing party for

expenses to encourage active protection of copyright, since the value

of the copyright, and hence any damage recovery, is difficult: to

measure. See Note, Distribution of Legal Expenses Among Liti

gants, 49 Yale L.J. 699, 707 (1940).

12 The Norris-LaGuardia Act, 29 U.S.C. 107(e), cited by the

United States, provides that before a temporary restraining order

may be issued, the party which has requested it must provide an

undertaking, the amount of which will be fixed by the court, suffi

cient to cover “all reasonable costs (together with a reasonable

attorney’s fee) and expense of defense against the order.”

12

“costs” under the Federal Rules to include attorneys’

fees.

If Rule 68 is interpreted as it was by the district court,

and as now urged by petitioners, the definition of “costs”

for the purpose of Rule 68 would vary with the stat

utory basis of the underlying action. It is anomalous to

define “costs” under Rule 68, but not the other Federal

Rules,1'3 differently depending on (1) whether the prevail

ing plaintiff would otherwise be entitled to attorneys’ fees

under the statute;13 14 (2) if so, whether that statute per

mitted the award of costs, “ including” attorneys’ fees, or

instead, costs “ and” attorneys’ fees, in which case Rule 68

would not apply under petitioners’ argument since fees

are not described as part of costs;15 (3) whether the fee

award statute provides for a mandatory or discretionary

award of fees ;16 and (4) whether the statute authorizes

attorneys’ fees to the prevailing party, either plaintiff or

13 The Advisory Committee’s 1938 notes to Rule 54(d), which

provided then as now for a shifting- of costs, cited an article by

Payne, Costs in Common Law Actions in the Federal Courts, 21

Va. L. Rev. 397 (1935) for an explanation of “ the present rule in

common law actions,” The article indicates that attorneys’ fees

were not considered part of the costs to be awarded.

14 For example, see 49 U.S.C. § 11705(d) (3) (mandatory award

of attorneys’ fees against carrier in violation of Interstate Com

merce Act).

15 Compare, for example, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 15

U.S.C. §78i(e) ( “ [T]he court may . . . assess reasonable costs,

including reasonable attorneys’ fees . . .” ), with 28 U.S.C. §1927

( “ [A]ny attorney . . . [engaged in vexatious litigation] may be

required by the court to satisfy personally the excess costs, ex

penses, and attorneys’ fees reasonably incurred. . .” ).

16 Compare the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 15(a) ( “ [A]ny person

who shall be injured . . . shall recover . . . the costs of suit, including

a reasonable attorney’s fee” ), with 17 U.S.C. § 505 ( “the court may

. . . award a reasonable attorney’s fee t» the prevailing party as part

of the costs” ).

13

defendant.17 Rule 68 should not be interpreted in this

varying and essentially haphazard way. Nor should it be

interpreted to disadvantage prevailing plaintiffs in civil

rights litigation who have not accepted an offer of judg

ment. There is no logical way, given a definition of costs

that varies with the cause of action, to ensure that costs

— enormously increased to include the losing defendant’s

attorney’s fee—would not be shifted to the prevailing

plaintiff in a civil rights action.18 In contrast, prevailing

plaintiffs to whom Rule 68 is equally applicable but who

are not eligible for fee-shifting would have the benefit of

the common interpretation of costs. Thus, they would be

required, at most, to pay costs as those costs are usually

defined.

17 See, for example, 17 U.S.C. § 505, cited above, and the Agri

cultural Fair Practices Act of 1967, 7 U.S.C. § 2305(a) ( “ [T]he

court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party a reasonable

attorney’s fee as part of the costs” ).

18 As Justice Rehnquist explained in Delta Airlines, 450 U.S.

at 378,

To construe Rule 68 to allow attorney’s fees to be recoverable

as costs would create a two-tier system of cost-shifting under

Rule 68. Plaintiffs in cases brought under those statutes which

award attorneys’ fees as costs and who are later confronted

with a Rule 68 offer would find themselves in a much different

and more difficult position than those plaintiffs who bring

action under statutes which do not have attorneys’ fees provi

sions.. No persuasive justification can be offered as to how such

a reading of Rule 68 would in any way further the intent of the

Rule which is to encourage settlement.

It is true that the district court in this case did not require the

plaintiff to pay the attorneys’ fees incurred by the defendants after

rejection of the settlement offer and that petitioners do not seek

that result here. Nevertheless, we believe that it will be difficult

to limit the effect of the approach urged by petitioners. Once the

mechanical operation of Rule 68 is permitted to defeat the congres

sional policy of awarding fees to prevailing plaintiffs in Section

1983 suits, every defendant in a civil rights case can be expected

to argue that the “pro-settlement” objectives, of Rule 68 should be

maximized by including defendants’, as well as plaintiffs’ , fees in

the “costs incurred” after rejection of a settlement offer.

14

Adoption of petitioners’ construction of Rule 68 would

defeat the careful congressional policies embodied in the

fee-shifting statutes. Congress has historically used fee-

shifting to encourage private citizens to enforce certain

statutes and to vindicate national policies. Fee-shifting

encourages private citizens to use their statutory rights

to obtain redress for wrongs. Such wrongs need not in

volve pecuniary damages and therefore may not result in

damage awards from which attorneys’ fees can be paid.

Although fee-shifting is an essential mechanism through

which Congress has particularly encouraged protection of

the civil rights of all Americans,19 fee awards have also

been provided by Congress in litigation involving other

areas of public concern, such as the environment (Clean

Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7604(d)) ; consumer affairs (Truth

in Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1640 ( a ) ) ; and labor matters

(Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. § 216(b)). Con

gress has differentiated among fee statutes as to the ex

tent of entitlement,2'0 thereby expressing its view that the

need for fee-shifting may vary between subject areas.

19 “The fee provisions of the civil rights laws are acutely sensitive

to the merits of an action and to antidiscrimination policy.” Road

way Express, 447 U.S. at 762. See Title II and Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000a-3 (b ) , 2000e-5 (k ),

providing in public accommodations and employment discrimination

cases that the prevailing party may receive “a reasonable attor

ney’s fee as part of the costs.” Congress has included fee-shifting

provisions in most recent civil rights legislation.

a° For example, a fee award is mandatory under the Truth in

Lending Act for a prevailing plaintiff; and is to be awarded under

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in the absence of exceptional

circumstances. The House report on the subject of fee-shifting at

the time o f the 1976 Fees Awards Act, described the variations

in some of these laws:

[T]he United States Code presently contains over fifty provi

sions for the awarding of attorney fees in particular cases.

They may be placed generally into four categories: (1) manda

tory awards only for a prevailing plaintiff; (2) mandatory

15

The inappropriateness of a construction of Rule 68

that defeats Congress’ fee-shifting provisions is shown by

examination of the purposes of those provisions. The

private citizen wrho brings suit to enforce the civil rights

laws does so not for himself alone, but as a “ ‘private

attorney general’ vindicating a policy that Congress con

sidered of the highest priority.” Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968) (footnote omit

ted). Congress has expressly acknowledged the signifi

cant role “private attorneys general” play in the enforce

ment of its policies and has long sought to encourage

individuals to fulfill this critical function by authorizing

the statutory award of attorneys’ fees. S. Rep. No.

1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 3 (1976), reprinted in 1976

U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 5908, 5910 (hereinafter

S. Rep. No. 1011). Failure to award attorneys’ fees

in such cases “would be tantamount to repealing the Act

itself by frustrating its basic purpose. . . . Without

counsel fees the grant of Federal jurisdiction is but

a[n empty] gesture. . . .” Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1, 13

(1973) (discussing award of attorneys’ fees in a Labor-

Management Reporting and Disclosure Act case).

There is, therefore, a strong and consistent congres

sional policy to authorize fee-shifting only when, and to

the extent, that Congress finds shifting to be in the pub

lic interest. To change the definition of costs in Rule 68,

as petitioners now urge, would defeat that careful con

gressional policy, inhibit the achievement of important

national goals, and substitute uncertainty and confusion. *

awards for any prevailing party; (3) discretionary awards for

a prevailing plaintiff; and (4) discretionary awards for any

prevailing party. Existing statutes allowing fees in certain

civil rights cases generally fall into the fourth category.

H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 5 (1976).

16

III. THE EXERCISE OF RIGHTS GUARANTEED BY

CONGRESS THROUGH SECTION 1983 WILL BE IM

PERMISSIBLY CHILLED IF RULE 68 COSTS ARE

INTERPRETED TO INCLUDE ATTORNEYS’ FEES

Respondents sued under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which was

derived from Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871,

17 Stat. 13, and provides a right of action “ in favor of

persons who are deprived of ‘rights, privileges or im

munities secured’ to them by the Constitution.” Carey v.

Piphus, 435 U.S. 247, 253 (1978) (citation omitted).

Section 1983 “opened the federal courts to private citi

zens, offering a uniquely federal remedy against incur

sions under claimed authority of state law upon rights

secured by the Constitution and laws of the Nation.”

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225, 239 (1972) (footnote

omitted).

The Fees Awards Act was intended by Congress to

ensure effective enforcement of Section 1983 and other

civil rights laws “by making it financially feasible to

litigate civil rights violations.” Dowdell v. City of

Apopka, Florida, 698 F.2d 1181, 1189 (1983) (citation

omitted). Congress and the courts have recognized that

civil rights litigants are often poor, and that the avail

able judicial remedies may be non-monetary (Mitchum

v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225) or an award of nominal dam

ages (Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247).21 Compensatory

damages, together with attorneys’ fees, are intended to

compensate the victim and deter violations of the civil

rights laws. Civil rights legislation manifests “heavy

reliance” on attorneys’ fees. S. Rep. No. 1011 at 3. The

important purposes of Section 1988, as well as Section

1983, would be gravely threatened if an offer of judg

ment made under Rule 68 could, without more, prevent

21 See Committee on Legal Assistance, Counsel Fees in Public

Interest Litigation, 39 Rec. A.B. City N.Y. 300 (May/June 1984),

for a recent analysis of fee awards in civil rights cases and the

policy implications of such awards.

17

courts from exercising their discretion with respect to

the award of attorneys’ fees.25

The legislative history of Section 1988 reveals con

tinued congressional concern with the enforcement of fed

eral civil rights laws, and a commitment to attorneys’

fees awards as an “ integral part of the remedy necessary

to achieve compliance” with the fundamental statutory

policies:

In many cases arising under our civil rights laws,

the citizen who must sue to enforce the law has little

or no money with which to hire a lawyer. If private

citizens are to be able to assert their civil rights,

and if those who violate the Nation’s fundamental

laws are not to proceed with impunity, then citizens

must have the opportunity to recover what it costs

them to vindicate these rights in court.

S. Rep. No. 1011 at 2.

This Court has recognized, as did the Senate Judiciary

Committee in considering fee-shifting as a remedy in

civil rights cases,22 23 that the potential liability of Section

1983 defendants for attorneys’ fees “provides additional

— and by no means inconsequential— assurance that

agents of the State will not deliberately ignore due proc

ess rights.” Carey v. Piphm, 435 U.S. at 257 n .ll.24

22 See, for example, Note, The Offer of Judgment Rule in Employ

ment Discrimination Actions: A Fundamental Incompatibility, 10

Golden Gate U.L. Rev. 963 (1980).

23 The Senate Judiciary Committee concluded in 1976, after ex

tensive hearings on the subject, that “ the effects of such fee awards

are ancillary and incident to securing compliance with these laws,

and that fee awards are an integral part of the remedies necessary

to obtain such compliance.” S. Rep. No. 1011 at 5 (emphasis

added).

24 Congress continues to recognize the importance of fee-shifting

to ensure that there will be civil rights plaintiffs. The current

Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s, Subcommittee on the

18

If petitioners’ interpretation of the interplay between

Rule 68 and Section 1988 were correct, these long-settled

policies would be defeated. Rule 68 does not permit a

court to evaluate the “value” of injunctive relief. Thus,

a civil rights plaintiff presented with an early offer of

judgment that included a realistic estimate of damages

but no nonmonetary relief would be left seriously at risk

by refusing to settle. Encouraging premature settlements

of civil rights actions would, contrary to the intent of

Congress, erode enforcement of civil rights and other

statutes.

These problems would be compounded by simple eco

nomics, A defendant with deep pockets could use his re

sources to increase the plaintiff’s litigation expenses by

expanding discovery and engaging in extensive motion

practice.25 Costs and attorneys’ fees would be incurred

by both sides. If petitioners’ view of Rule 68 prevails,

and attorneys’ fees and costs can be shifted to the plain

tiff, the defendant with deep pockets would be able

greatly to increase the plaintiff’s risks of refusing a set

Constitution, Senator Orrin Hatch, has recognized that the Fees

Awards Act was intended to’ benefit only plaintiffs:

The legislative history o f the: 1976 Fees Act pointed out clearly,

and correctly I think, the need for the dual standard: If the

persons seeking to enforce their civil rights were faced with

paying their opponents [sic] attorneys’ fees if they simply did

not win the case, the Fees Act would create a greater disincen

tive to bring these civil rights suits than the situation it

attempted to remedy.

128 Cong. Rec. S4878 (daily ed. May 11, 1982).

25 “ [D.]iscovery practices enable the party with greater financial

resources to prevail by exhausting the resources of a weaker oppo

nent.” Amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 85

F.R.D. 521, 523 (1980). (Dissent by Justices Powell, Stewart and

Rehnquist to the adoption of amendments to the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure discovery rules).

19

tlement offer.26 These risks may compel the plaintiff’s

attorney to recommend settlement even if by doing so the

plaintiff abandons an opportunity to obtain important

nonmonetary relief.

These dangers are illustrated by this case. The jury

award in this case consisted of $52,000 for the violation

of civil rights; $3,000 as punitive damages; and $5,000

for wrongful death. Pet. Brief at 4. In nonmonetary

terms, respondent was vindicated, and it is not unreason

able to believe that the jury verdict may have had a

beneficial effect on the community involved, thereby

achieving one of the congressional purposes in enacting

Sections 1983 and 1988. Although the United States has

characterized the offer of judgment here as “ obviously

reasonable” and chastized respondent for his “unreason

able failure to accept a favorable settlement,” Brief of

the United States at 3, neither the District Court nor the

Court of Appeals suggested that the refusal of the offer

was unreasonable under the circumstances. Instead, both

courts recognized that new dilemmas for civil rights at

torneys and their clients would be created if Rule 68 were

read to preclude awards of attorneys’ fees after a settle-

ment offer higher than the ultimate jury verdict. Chesny

v. Marek, 547 F. Supp. 542, 547 (N.D. 111. 1982); 720

F.2d 474, 478-79 (7th Cir. 1983).

Rule 68 should not be interpreted so as to increase the

pressures on civil rights plaintiffs and similar benefici

aries of fee-shifting statutes to settle, while leaving other

plaintiffs subject to the Rule with the lesser burden of

traditional costs. The fundamental policies behind fee-

26 The “ risks” of failing to settle, under petitioners’ interpreta

tion of Rule 68, might include the following: (1) the plaintiff would

have to bear his own attorney’s fee after the offer; (2) the public

interest attorney would be unable to obtain reimbursement for time

spent after the offer; and (3) defendant's; costs and attorney’s fees

would have to be borne by the successful plaintiff. See also n.18,

infra at p. 13.

20

shifting legislation should not be swept away by an artifi

cial construction of a rule which is merely procedural.

Congress did not intend that Rule 68 would be used to

negate basic public policies designed to protect essential

civil liberties.

CONCLUSION

The judgment below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Harold R. Tyler, Jr.*

Sara E. Lister

Heather D. D iddel

Patterson, Belknap,

Webb & Tyler

30 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, New York 10112

(212) 541-4000

1730 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 783-6518

* Attorney of Record

Fred N. F ishman

Robert H. Kapp

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae