Campbell v. Department of the Navy Commander Petition for In Banc Hearing

Public Court Documents

January 25, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Campbell v. Department of the Navy Commander Petition for In Banc Hearing, 1990. d9eb31ac-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bae1cf6c-e4d9-46e6-9d57-a80c3086bb50/campbell-v-department-of-the-navy-commander-petition-for-in-banc-hearing. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

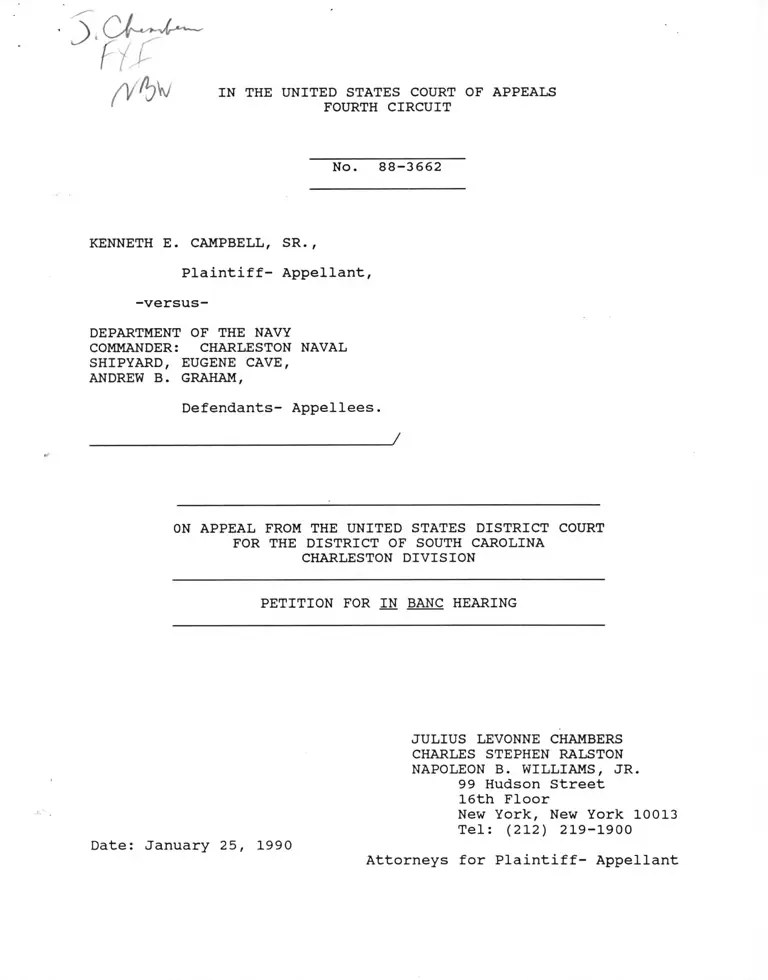

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOURTH CIRCUIT

'hf

No. 88-3662

KENNETH E. CAMPBELL, SR.,

Plaintiff- Appellant,

-versus-

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY

COMMANDER: CHARLESTON NAVAL

SHIPYARD, EUGENE CAVE,

ANDREW B. GRAHAM,

Defendants- Appellees.

/

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

CHARLESTON DIVISION

PETITION FOR IN BANC HEARING

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Tel: (212) 219-1900

Date: January 25, 1990

Attorneys for Plaintiff- Appellant

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 88-3662

KENNETH E. CAMPBELL, SR.,

Plaintiff- Appellant,

-versus-

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY

COMMANDER: CHARLESTON NAVAL

SHIPYARD, EUGENE CAVE,

ANDREW B. GRAHAM,

Defendants- Appellees.

/

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

CHARLESTON DIVISION

PETITION FOR IN BANC HEARING

PETITION FOR REHEARING PURSUANT TO RULE 40

OF THE FEDERAL RULES OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE

AND LOCAL RULE 35 WITH A SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING IN BANC

Appellant- plaintiff Kenneth E. Campbell herein requests

rehearing of his appeal from the federal district court below with

a suggestion for a rehearing in banc.

The petition for an in banc rehearing is based upon counsel's

judgment that the per curiam decision by the panel in this appeal

fails to consider applicable legal principles, overlooks material

facts, conflicts with decisions of the Supreme Court in Brandon v.

Holt. 469 U.S. 464 (1985); Zipes v. Trans World Airlines. Inc.. 455

U.S. 385 (1982), is inconsistent with the legislative history of

Congressional statutes authorizing suits against the United States

as well as 28 U.S.C.§ 1653, and contravenes Rules 8(a), 15(c), and

25(d) of the Fed. R. Civ. P.

The request for rehearing is made pursuant to Rule 40 of the

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. Appellant's suggestion for

rehearing in banc is made pursuant to Local Rule 35 of this Court.

The panel affirmed the district court's judgment dismissing

the action, on the ground on stare decisis. The per curiam opinion

held that the panel was bound by a July 27, 1989 decision of

another panel of this Court in Gardner v. Gartman. 880 F.2d 797

(4th Cir. 1989).

The Court in Gardner v. Gartman. supra, held that 42 U.S.C.§

2000e-16(c) requires the head of a federal department to be named

as defendant in a suit under 42 U.S.C.§ 2000e-16(c), and that

amendments, under Rule 15(c), Fed. R. Civ. P., substituting the

head of the department for the department as the defendant must be

denied if not made within thirty days after plaintiff's receipt of

the final notice of discharge.

Accordingly, the panel held, it was precluded by stare decisis

from considering appellant's argument herein that "Congress did not

intend for actions to be dismissed merely because a plaintiff sues

a federal agency or department rather than the head of the

2

department".

For the same reason, the panel said, it was unable to consider

appellant's other argument that he had not sued the wrong defendant

within the meaning of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, but

rather had sued the right defendant although misdescribing the

defendant sued.

The panel stated that it had no authority to overturn Gardner

v. Gartman. supra. and that "(o)nly an en banc court can overturn

a panel holding".

REASONS FOR GRANTING REHEARING IN BANC

A. Failure to Consider Legislative History

The courts which have decided cases of this type have based

their decisions upon a literal, or plain meaning, reading of 42

U .S .C .§ 2000e-16(c) and not upon any examination of the legislative

history of either 42 U;.S.C.§ 2000e-16(c) or of similar statutes

waiving sovereign immunity. The panel which heard this appeal also

decided the case without consideration of this issue.

Many of the employment discrimination cases against the United

States are litigated pro se and, perhaps for that reason do not

present arguments based upon legislative history or present any of

the other types of arguments raised herein by appellant in this

appeal.

Similarly, to the best of appellant's knowledge, none of the

arguments raised in this appeal has been presented in any of other

employment discrimination cases, with the exception, of course, of

the argument based upon the Supreme Court's decision in Zipes v.

3

Trans World Airlines. Inc.. 455 U.S. 385 (1982) that the 30 day

time period for filing an employment suit under 42 U.S.C.§ 2000e-

5(e) is not jurisdictional and therefore is waivable.

Because the principal arguments made upon this appeal are new,

and were not considered by the panel or any other court, appellant

has filed this petition for rehearing in banc.

There are several major strands to appellant's argument.

First, appellant has shown, in his brief on appeal, that the

legislative history of 42 U.S.C.§ 2000e-16(c) reveals no evidence

of any Congressional intention to deny federal employees a federal

judicial remedy for employment discrimination based upon the

employee's failure to name, in his or her complaint, the proper

federal entity or official as a defendant. See. Report of the

House Committee on Education and Labor, HR Rep. No. 92-238, June

2, 1971, and Report of the Senate Labor Committee. See. S Rep. No.

92-415 (1971).

Instead the legislative history shows a great concern in

Congress with the fact that federal employees encountered

inordinate legal difficulties and technicalities in suing the

federal government.

Particular concern was expressed by the Congress over the fact

that aggrieved employees did not have easy access to the courts,

and that they "must overcome a U.S. Government defense of sovereign

immunity ..." S. Rep. No. 92-415, p. 16. See. also House Rep. No.

92-238, p .2 5.

In enacting 42 U .S .C .§2000e-16(c) in 1972, Congress acted to

4

rectify conditions in which it found that "federal employees ...

face legal obstacles in obtaining meaningful remedies". S Rep. No.

92-415, p. 25.

The second strand of appellant's argument is based upon

subsequent Congressional action in the enactment of other

legislation permitting suits by federal employees against the

United States for employment discrimination or permitting suits

generally against the United States by waiving sovereign immunity.

Such action is evidenced in the Administrative Procedure Act,

5 U .S .C .§ 702 et sea; the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of

1967 ("ADEA"), 29 U.S.C. 621 et seq; and the Rehabilitation Act of

1973, 29 U.S.C. 794a, as amended.

In each case, as appellant tried to show in his brief,

Congress took care to make sure that the federal judicial remedy

was not unavailing simply because of plaintiff's choice of the

United States or a federal official or federal department or

federal agency as the defendant.

With respect to the Administrative Procedure Act, 5

U.S.C. 702, Congress amended the section in 1976 to provide that:

An action ... stating a claim that an agency or an

officer or employee thereof acted or failed to act

in an official capacity or under color of legal

authority shall not be dismissed nor relief therein

denied on the ground that it is against the United

States ...

Simultaneously, Congress enacted 703 of Title 5, U.S.C., to

provide that:

If no special statutory review proceeding is

5

applicable, the action for judicial review may be

brought against the United States, the agency by its

official title, or the appropriate officer.

The purposes of these two enactments are made clear in the

legislative history. For example, the House Report states that:

. . . the bill would simplify technical complexities

concerning the naming of the party defendant in

actions challenging Federal administrative action

... to permit the plaintiff to name the United

States, the agency or the appropriate officer as

defendant. This will eliminate technical problems

arising from plaintiff's failure to name the proper

Government officer as defendant. HR Rep. 94-1656,

Sept. 22, 1976, at p. 1.

The Committee report goes on to state, in unequivocal terms,

that the statutes are:

intended to eliminate technical problems arising

from a plaintiff's failure to name the proper

Government officer as a defendant. The first

clause of the new sentence is intended to preserve

specific provisions regarding the naming of parties

which have been or may in the future be established

by Congress. Such provisions may be part of a fully

developed review procedure or may be provisions

which are even more narrowly directed only to the

required naming of a particular defendant where such

requirement has intended consequences such as the

restriction of venue or service of process. An

example of the latter is 16 U.S.C. 831c(b), which

displays an intent that litigation involving actions

of the Tennessee Valley Authority be brought against

that agency only in its own name. See National

Resources Council v. Tennessee Valley Authority. 459

F .2d 255 (2d Cir. 1972). HR Rep. 94-1656, at p. 3.

Perhaps, the most explicit sections of the Report occur on

page 18 where the Committee says that:

The size and complexity of the Federal

Government, coupled with the intricate and technical

law concerning official capacity and parties

defendant, has given rise to numerous cases in which

a plaintiff's claim has been dismissed because the

wrong defendant was named or served.

6

Nor is the current practice of naming the head

of an agency as defendant always an accurate

description of the actual parties involved in a

dispute. Rather, this practice often leads to delay

and technical deficiencies in suits for judicial

review.

The unsatisfactory state of the law of parties

defendant has been recognized for some time and

several attempts have been made by Congress to cure

the deficiencies.

Despite these attempts, problems persist

involving parties defendant in actions for judicial

review. In the committee's view the ends of justice

are not served when government attorneys advance

high technical rules in order to prevent a

determination on the merits of what may be just

claims.

When an instrumentality of the United States is

the real defendant, the plaintiff should have the

option of naming as defendant the United States, the

agency by its official title, appropriate officers,

or any combination of them. The outcome of the case

should not turn on the plaintiff's choice.... HR

Rep at p .18.

This legislative history, which has not been evaluated or

considered by the panel or any other court, demonstrates that

Congress never intended for suits against the United States to be

lost because of technicalities such as whether the plaintiff sued

the United States in the name of an agency, department, or

official. Moreover, the Administrative Conference of the United

States supported the result. See, HR Rep. 94-1656, Exhibit A, at

p. 23. See, also S Rep. No. 94-996, June 26, 1976.

Despite the existence of such legislative history, the federal

courts have, up to now, failed to consider the impact of this

history in determining Congressional intent in applying 42 U.S.C.§

2000e-16(c). Rather, the courts which decide these cases do so

on the basis of a literal, mechanistic reading of the statute with

no attempts whatsoever to ascertain the underlying legislative

7

history and purpose.

B . Inconsistencies With Other Federal Statutes

Their literal interpretation of 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16(c),

however, has led to a paradox. For while the federal statute for

race discrimination claims, i.e., 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16(c), is

interpreted literally, the courts have simultaneously failed to

interprete the federal statutes for age discrimination and

disability discrimination literally.

The reason for the inconsistency is because neither the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 ("ADEA"), 29 U.S.C. 621

et sea, nor the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. 794a, as

amended, specifies that a particular federal official or entity

%should be named as the defendant in a suit brought under the

statute.

The courts have nonetheless interpreted the statutes to

require naming the agency or department head as the defendant.

They have justified this interpretation on the ground that Congress

undoubtedly must have intended the procedural requirements in the

statutes to be the same as those in suits under 42 U.S.C.§2000e-

16(c). For cases involving the ADEA see. Romain v. Shear. 799 F.2d

1416 (9th Cir. 1986); Ellis v. U.S. Postal Service. 784 F.2d 835

(7th Cir. 1986) ; contra; Shostak v. U.S. Postal Service. 655

F.Supp. 764 (D. Me. 1987) . For the Rehabilitation Act, see

McGuiness v. United States Postal Service. 744 F.2d 1318 (7th Cir.

8

1984) .

Thus, the literal interpretation of 42 U.S.C.§ 2000e-16(c)

has led into a vicious circle with a pernicious result. The panel

in this appeal confessed that it was unable to go back to square

one with a fresh analysis of the applicable arguments because of

the precedential force of another panel's decision in Gardner v.

Gartman. supra. Only an in banc court, the panel held, could, at

this juncture, freely consider all of the arguments.

C. Suits Against the Sovereign

Although the above is perhaps the strongest argument presented

in appellant's brief, appellants raised additional arguments in the

brief which also have not been passed upon by a court. The most

important of these arguments is appellant's cbntention that a

distinction must be drawn between suits against the wrong defendant

and suits against a defendant who is afproper defendant but who is

misdescribed.

The suit in Schiavone v. Fortune. 477 U.S. 21 (1986), upon

which the panel in Gardner v. Gartman. supra, based its decision,

is an example of the former while suits by federal employees

against the United States as sovereign are examples of the latter.

The nature of this distinction was spelled out in appellant's

brief and therefore does not need to be repeated here. The

distinction is illustrated in Judge Posner's decision in Maxey v.

Thompson. 680 F.2d 524, 526 (7th Cir. 1982), and, to a similar

extent, in the Third Circuit's decision in Cervase v. Office of

Federal Register. 580 F.2d 1166, 1171 (3rd Cir. 1978).

9

The distinction requires the courts, in the context of federal

employment suits, to recognize realistically that such suits are,

in truth, suits against the sovereign, and that the fictional

distinctions that are employed in injunctive suits pursuant to the

doctrine of Ex Parte Young. 209 U.S. 123 (1908), see also Larson

v. Domestic Foreign Corp.. 337 U.S. 682 (1949), have no place in

employment suits for damages or injuries.

Such a realistic appraisal is exactly what the Supreme Court

made in Brandon v. Holt. 469 U.S. 464 (1985) where it treated a

suit for compensatory damages against a defendant municipal police

official as being, in reality, a suit commenced against the

municipality. No amendment substituting a party defendant was

necessary for the Supreme Court to give recognition to this

underlying reality.

Indeed, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure achieves the same

end by insuring that suits brought against named governmental

officials for official wrongdoing, are not dismissed on the ground

that the person named defendant has ceased to hold the office and

has been replaced by someone newly appointed or elected.

Similarly, Rule 25(d), Fed. R. Civ. P. accomplishes the same

purpose. It provides for automatic substitution in such cases,

recognizing that although the suit may be styled as one against a

certain person in his or her official capacity, it is

neverthelesss, in law and in fact, a suit against the sovereign

and therefore can be maintained despite the occurrence of either

a vacancy in the position or a replacement of the official.

10

Such considerations suggest that to the extent the panel in

this case or in Gardner v. Gartman. supra. assumed that the holding

in Schiavone v. Fortune, supra. was applicable to suits in which

a sovereign government is sued by naming an agency, or department,

or official, as a defendant, then, to that extent, Rule 15(c), Fed.

R. Civ. P., was misapplied, resting as it were upon an erroneous

assumption concerning the nature of suits against the sovereign.

CONCLUSION

Since the guestions raised in this petition have not been

considered by the Court, appellant requests rehearing in banc for

the reasons stated above.

Respectfully submitted,

Dated: January 25, 1990

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Tel: (212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiff- Appellant

11

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned member of the bar of the Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit affirms that two copies of the within

appellant's petition for rehearing in banc appendix were served

upon the defendant herein by mailing said copies this 25th day of

January, 1990 to Vinton D. Lide and John H. Douglas, assistant

United States Attorney, at the address 145 King Street, suite 409,

Charleston, South Carolina, 29402.

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

12