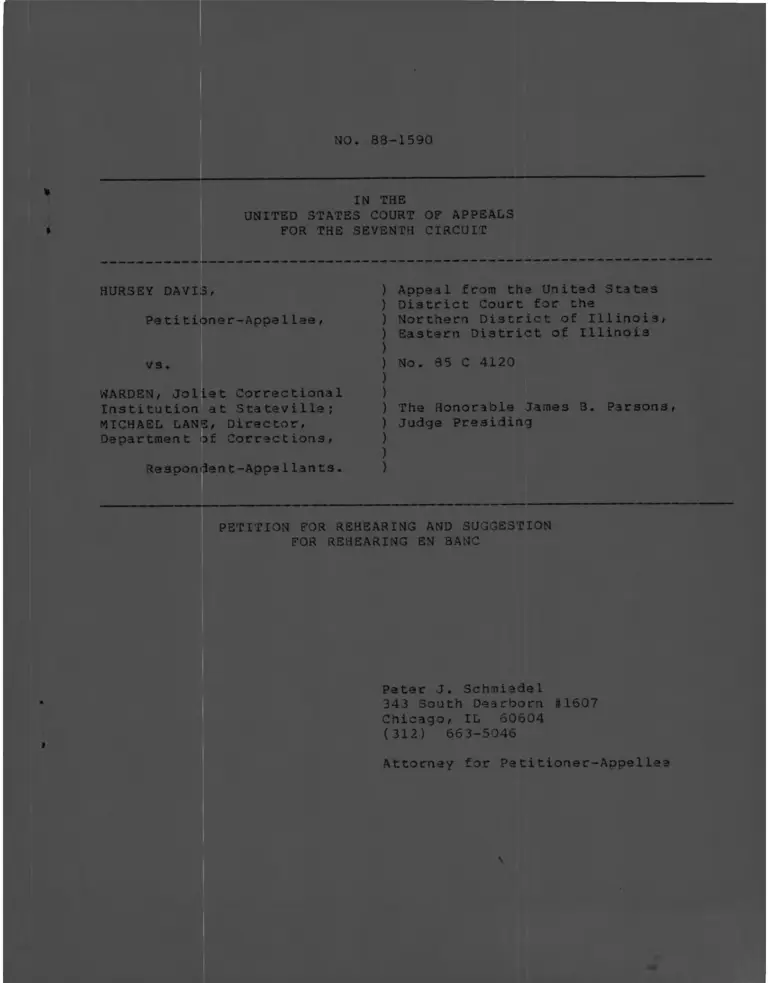

Davis v. Warden Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

February 15, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Warden Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion Rehearing En Banc, 1989. c4ea9e46-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bb00feee-f9fd-4e93-ae4c-954a175bfdc7/davis-v-warden-petition-for-rehearing-and-suggestion-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

HURSEY DAVIS,

Pe ti tioner-Appe1lae,

V 3 .

WARDEN, Joliet Correctiona1

Institution at Stateville;

MICHAEL LANE, Director,

Department of Corrections,

Respondent-Appellants.

) Appeal from the United States

) District Court for the

) Northern District of Illinois,

) Eastern District of Illinois

)

) No. 85 C 4120

)

)

) The Honorable James B. Parsons,

) Judge Presiding

)

)

)

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC

Peter J. Schmiadel

343 South Dearborn #1507

Chicago, IL 60504

(312) 663-5046

Attorney for Petitioner-Appellee

NO. 88-1590

*

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

* FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

HURSEY DAVIS,

Petitioner-Appallee,

V 3 .

WARDEN, Joliet Correctional

Institution at Stateville;

MICHAEL LANE, Director,

Department of Corrections,

Respondent-Appellants.

) Appeal from the United States

) District Court for the

) Northern District of Illinois,

) Eastern District of Illinois

)

) No. 85 C 4120

)

)

) The Honorable James B. Parsons,

) Judge Presiding

)

)

)

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC

Peter J. Schmiadel

343 South Dearborn #1507

Chicago, IL 60504

(312) 663-5046

Attorney for Petitioner-Appellee

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities»

Argumen t...........

i i

1

*

I.

REHEARING SHOULD BE GRANTED BECAUSE THE MAJORITY

OPINION PLACES A BURDEN OF PROOF ON THE PETITIONER-

APPELLEE IN THIS SIXTH AMENDMENT 'FAIR CROSS SECTION*

CASE WHICH IS IN CONFLICT WITH PRIOR SUPREME SOURT

DECISIONS AND THE DECISIONS OF OTHER CIRCUIT COURT OF

APPEALS, INCLUDING BATSON VS. KENTUCKY, 106 S.CT 1712

(1986); AVERY vs. GEORGIA,~T55 U.S. &9l (1953); DUREN

vs. MISSOURI; 439 U.S. 357 91979)............... 1

CONCLUSION

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

GASES

Alexander vs. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 ( 1971)............... 5

Avery vs. Georgia, 345 U.S. 891 (1953)..................... 4,6,9,10

Ba tson vs. Ken tucky , 106 S.Ct. 17112 ( 1986)................ 5,6,7,9

Castanda vs. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1976).................. 5

Davis vs. Zant, 721 F.2d 14778 ( 11th Cir.)

cert, denied 471 U.S. 1143 (1983).......................... 5

Duren vs. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979).................... 4,6

Taylor vs. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1979).................. 1,3

Teague vs. Lane, 820 F.2d 832 (7th Cir. 1987)

cert, granted 99 L.ed 2d 268 ( 1988......................... 1

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs vs. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 [1981)'.'.'............... 7..................... 6

Turner vs. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 ( 1969)..................... 2,5

Whitus vs. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967).................... 5

ii

REHEARING SHOULD BE GRANTED BECAUSE THE MAJORITY

OPINION PLACES A BURDEN OF PROOF ON THE PETITIONER

APPELLEE IN THIS 6th AMENDMENT 'FAIR CROSS SECTION'

CASE WHICH IS IN CONFLICT WITH PRIOR SUPREME COURT

DECISIONS AND THE DECISONS OF OTHER CIRCUIT COURT OF

APPEALS, INCLUDING BATSON V. KENTUCKY, 106 S.CT. 1712

(1986); AVERY V. GEORGIA, 345 U.S. 891 (1953); DUREN

V. MISSOURI, 439 U.S. 357 (1979).

I.

The Petitioner, Hursey Davis, a Black man, attacked his

state court conviction in this Federal habeas corpus case on

the grounds that the venire from which he had to select his

petit jury did not represent a fair cross section of Cook

County, the community from which the jurors were summoned. In

his case Mr. Davis established that although Blacks comprised a

significant portion of the county's population (25.6%) none of

the 40 jurors summoned to his courtroom in the overwhelmingly

white suburbs of Des Plaines were Black. Mr. Davis found this

obvious and significant underrepresentation to be offensive to

Sixth Amendment mandates that he be given "a fair possibility

for obtaining a jury constituting a representative cross sec

tion of the community." See Taylor vs. Louisiana, 419 U.S.

522, 529 (1975); Teague vs. Lane, 820 F.2d 832, 837 (7th Cir.

1987) cert, granted 99 L.Ed.2d 268 (1988).* Upon seeing the

all white venire, counsel for Mr. Davis at his criminal trial

both requested on evidentiary hearing and supplied the trial

judge with an explanation for the all white venire; i.e. he was

aware from another case recently heard in the same suburban

*0f course in Mr. Davis' case the possibility oil selecting

a petit jury with even one Black person, let alone a jury that

actually approximated the community, was zero.

1

courthouse that a "convenience" factor was employed to direct

jurors to court cites near their homes, and because the nor

thern suburbs and north-west side of Chicago were overwhelming

white and that many of the 40 venira-persons came from these

areas, it appeared to him that this mechanism was utilized in

Mr. Davis' case. Davis' counsel requested the judge to inquire

as to whether the convenience mechanism was employed in Mr.

Davis' case, the judge refused.* (Tr. Doc. 21, Appendix B, p.

230)

Following the filing of his habeas petition Mr. Davis

discovered from the jury commissioner responsible for the

selection procedure in effect at the time of his trial that

throughout the relevant period convenience factors were

employed in urging jurors to volunteer to serve in suburban

courthouses near their homes, including Des Plaines. As part

of his motion for summary judgment in his habeas case Mr. Davis

also supplied statiscal evidence demonstrating that it was

virtually impossible to select 40 persons at random from Cook

★ ★County and have no Blacks included.

In its decision the majority Panel in this case (See Davis

* In his post trial motion counsel for Davis supplied the

trial judge with the transcript of the case he referred to pre

trial. The transcript demonstrated that in that case

convenience factors were utilized to direct jurors to Des

Plaines. The judge in that case granted a new trial to the

Defendant, finding the procedure unconstitutional.

**Petitioner's stati sties were based on comparing the

total population of Cook County which is 25.6% Black with the

makeup of Petitioner's venire, which contained no Blacks out of

40. This methodology has been specifically approved by the

Supreme Court. See Turner vs. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1969)

2

v 3. Warden , 88-1590 slip opinion (2-1-89) Judge Flaum

dissenting, hereinafter Davis) recognized that the Petitioner's

right to select from a venire that represented a fair cross

section of the Cook County community was "an essential

component of the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial." Davis

p. 4-5 quoting Taylor vs. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 696 (sic),

528 (1975). The Panel's decision then went on to accept

Petitioner's argument that the relevant community in Mr. Davis'

case was the whole of Cook County. Davis slip opinion p. 12,

14.

In its discussion of the appropriate comparative community

for fair cross section purposes the Panel also explicitly

recognized that the convenience/vo1untear system employed by

the jury commissioner throughout 1981, the year of Mr. Davis'

trial, impermissably narrowed "the geographic scope from which

the jury list is drawn." Davis p. 15. The panel reasoned that

because the Supreme Court's 6th Amendment decisions are

designed to increase minority participation a "narrow

definition of community could undermine the policy of

inclusivaness underlying the Sixth Amendment..." and "when

prospective jurors choose to serve near their homes they do not

consider the broader policy of inclusiveness critical to the

sixth amendment." Davis p.19.

After accepting Petitioner's arguments that the relevant

community was the whole of Cook County and that the convenience

factors which were admittedly employed by the jury commissioner

3

unconstitutionally narrowed the definition of community for

Sixth Amendment purposes the Panel went on to analyze whether

Petitioner's evidence discharged his obligation under Duren vs.

Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979) to establish a prima facie viola

tion of the Sixth Amendment's fair cross section requirement.

Duren set out a three pronged test for determining whether

a Defendant established a prima facie violation of the Sixth

Amendment. The Panel's decision held that the Peitioner had

successfully demonstrated that Blacks were a distinctive group

in Cook County and that a 25.5% disparity between the number of

Blacks in Cook County and the number on Petitioner's venire

(0%) demonstrated that Blacks were in fact underrepresented on

Petitioner's venire. Davis p. 5/ 21.

The Panel ruled however the Petitioner failed to prove

that the jury selection system actually caused the

underrepresentation of Blacks in his case because the jury

commissioner couldn't recall ultilizing it in Petitioner's

•ff # 9case and because Petitioner did not prove that any of the 40

jurors actually volunteered. In imposing this quantum of proof

on Petitioner for purposes of establishing a prima facie case

the Panel's decision is at odds with the entirety of Supreme

Court precedent in the area and other circuits as well. See

e.g. Duren v s. Missouri/ supra/ Avery vs. Georg ia t 345 U.S.

*In fact the jury commissioner would have no way of

knowing the name of any case to which he assigned jurors/

because jurors were assigned by judge and courthouse not by

case name. In any event the jury commissioner testified that

the convenience/volunteer system was employed throughout the

entire time relevant to Petitioner's case. (Covelli dep. p.ll)

4

891 (1953) Alexander vs. Louisiana/ 405 U.S. 625 (1971)/

Castaneda vs. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1976) Batson vs. Kentucky,

106 S. Ct. 1712 (1986); Turner vs. Fouche, 396 U.S. 3 46 (1969);

Whitus v s. Georgia; 385 U.S. 545 (1967) See also Davis vs.

Za n t, 721 F. 2d 1478 (11th Cir.) cert, denied 471 U.S. 1143

(1983).

These prior Supreme Court decisions, in both the equal

protection area and the Sixth Amendment "fair cross section"

area make it clear that once a Defendant has demonstrated, as

Mr. Davis has here, that a distinctive group in the community

is significantly underrepresented on his venire, it is only

incumbent upon the Defendant to establish that a racially non

neutral selection procedure was in place that could account for

the unconstitutional underrepresentation. Not even in equal

protection cases, where a Defendant must also establish an

intent factor(unnecessary under the Sixth Amendment), has the

Supreme Court ever required the Defendant as part of his prima

facie case to prove that the racially non-neutral selection

mechanism .actually caused the underrepresentation in his

specific case. The majority opinion, by nonetheless requiring

this additional showing in order to establish a prima facie

case deviates dramatically from prior Supreme Court precedent.

5

Ba taon/ Avery/ Duren.

In cases involving challenges to the venire the Supreme

Court has recognized, most recently in Batson, 106 S. Ct. at

1722, that it ha3:

...found a prima facie case on proof that members of

the Defendant's race were substantially underrepre

sented on the venire from which his jury was drawn,

and that the venire was selected under a practice

providing the oppor tun i ty _to discriminate, citing

W h i tus vs. Georgia, 385 U.S. at 552, Ca s ta ne da v s.

Pa r t i da 4430 U.S. at 494; Washington vs. Davis 426

US., at 241; Alexander vs. Louisiana, 405 U.S. at

629-631. (emphasis addedl

And, as early as 1953, in Avery vs. Georgia, 345 U.S. 891

(1953) the Supreme Court found that where Blacks comprised 5%

of the eligible jury li3t the fact that there were no Blacks on

a venire of 60 was not acceptable and established a prima facie

case, where the procedure employed to select the venire pro

vided an opportunity to discriminate. In Ave ry the Court

specifically rejected the argument, essentially adopted by the

Panel in Davis, that the Defendant failed to establish a prima

facie case because he had:

...failed to prove some particular act of discrimina

tion by some particular officer responsible for the

selection of the jury. Avery, 345 U.S. at 562.

★

*It should be noted initially that the burden of esta

blishing a prima facie case is not and should not be an onerous

one. See cf. Texas Department of Community Affairs vs Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 (1981) Batson supra. The analytic purpose of the

prima facie case is not to require a party to conclusively

prove the proposition at issue but rather to merely raise on

inference of discriminatory impact or purposes that shifts the

burden to the state to produce a constitutional explanation.

It's not the same burden a party has in ultimately proving

discrimination once an explanation has been supplied that suf

ficiently rebuts the discriminatory inference. Texas etc. vs.

Burdine.

6

Once the underrepresentation had been shown, for the pur

poses of establishing a prima facie case, all that was neces

sary was the opportunity to discriminate.

Significantly, the Panel's decision in the instant case

accepts Petitioner's argument that the "convenience" system

provided such an opportunity, but instead of shifting the

obligation to the state to explain how the underrepresentation

may have occurred constitutionally the Panel's decision places

an additional burden on the Petitioner of proving the flawed

mechanism (the "convenience" system) actually caused the demon-

strated underrepresentation. (Slip opinion p.22) This addi

tional burden is wholly inconsistent with prior Supreme Court

precedent.

In reaching this conclusion the Panel ignores the fact

that in Ba tson the Supreme Court has already held that a suffi-

* Under t"he ra’tXo n aTe of the iljo r i ty' s ife’cTsion Tn tTHe

instant case the Defendant in the leading Sixth Amendment

Supreme Court case, Duren vs. Missouri would have lost. In

Duren the Petitioner attacked the exclusion of women from his

venire. He demonstrated that while women comprised 54% of the

community there were only 5 women on his 53 person venire.

Defendant further established that Missouri had in place an

eligibility exemption that allowed women to exempt themselves

from jury duty and that this procedure was utilized in previous

cases. The Supreme Court found this evidence to be a suffi

cient prima facie violation of the Sixth Amendment's fair cross

section requirement. The Petitioner was not required to show

that any particular women utilized the exemption or if they had

not exempted themselves, they would have been on his venire.

The majority's decision in Mr. Davis' case unlike the Court in

Duren requires the Petitioner to point to a particular juror

who actually volunteered. Moreover, the majority panel's deci

sion is particulary unfair, given the fact, as noted in Judge

Flaum's dissent, slip opinion p.29, that Davis' counsel re

quested the state court judge ask the members of the venire if

they volunteered to serve in the Des Plaines courthouse and the

judge refused to do so.

7

cient prima facie showing was established by producing evidence

in the defendant's own case that Blacks were underrepresented

and the venire was selected under a practice "providing an

opportunity for discrimination." Ba tson, 106 S. Ct. at 1722.

The Court explained further that:

This combination of factors raises the necessary

inference of purposeful discrimination because the

Court has declined to attribute to chance the absence

of black citizens on a particular jury array where

the selection mechanism is subject to abuse. Ba tson,

106 S. Ct. 1722

The majority in Mr. Davis' case/ unlike the Supreme Court

in Batson, willingly attributes "to chance" the wholesale ex

clusion of Blacks from the venire because of the mere possibi

lity that resort to some other data base would ultimately

undercut the Petitioner's statistical showing.

In this regard the majority complains that the Peti

tioner's statistics (which demonstrated the chance of randomly

selecting 40 white jurors from Cook County where 25.6% of the

population was Black was seven in one million) were not relia

ble because the Petitioner used the whole county population to

make his comparison instead of just the adult population, which

the majority opinion holds was more appropriate. The majority

opinion speculates that perhaps the Petitioner's statistics

were "overinclusive" because it may be that non-racial factors

such as age would have reduced the percentage of Blacks from

25.6% of the whole population to some lesser proportion of

those eligible to vote. (Slip opinion p. 23) However, even

assuming that resort to comparing those eligible to vote would

B

reduce the proportion of Blacks downward from 25.6% to even as

low as 5% of the adult population, excluding 80% (4 out of 5)

of the Black population (unquestionably not the case) the

failure to have any Blacks out of 40 would still not be ex

plained in random terms, and would therefore still support the

inference that a racially non-neutral device caused the under

representation. (See Avery)

Certainly, the underrepresentation of Blacks in combina

tion with the statistical evidence, the representation of Da

vis' trial counsel that he was aware that convenience factors

were used in a previous case in the same courthouse, the fact

that a substantial number of jurors actually came from the

white suburbs surrounding the Des Plaines courthouse, and the

testimony of the jury commissioner that his practice was to ask

jurors to serve near their homes was a sufficent prima facie

showing. See Ba tson.

Moreover, even if the dramatic underrepresentation of

Blacks on Petitioner's venire would be explained by comparing

only the adult population of Cook County then it was incumbent

upon the state to provide that possible, though far fetched,

explanation. The state had every opportunity before Judge

Parsons to rebut Petitioner's evidence by providing the infor

mation on the comparative number of Blacks to whites who were

eligible to vote. This they did not do, however, and for good

reason. The comparative numbers undoubtedly would have been

fairly approximate to the county as a whole and at best would

9

have reduced the statistical showing from seven in one million

to some other infinitesimal possibility.

In 1953, the total absence of Blacks from the Defendant's

60 person venire in Avery, where Blacks comprised a mere 5% of

those eligible for jury service, caused Justice Frankfurter in

his concurring opinion to comment:

The stark resulting phenomenon here was that ... no

Negro got onto the panel of 60 jurors from which

Avery's jury was selected. The mind of justice as

well as its eyes, would have to be blind to attribute

such an occurrence to chance.

The same holds true some 36 years later.

II.

Aside from the purported statistical failure in

Petitioner's case the majority opinion also blames Petitioner's

trial counsel for failing to conclusively establish that the

volunteer system was actually employed in Petitioner's case.

This holding is particularly unfair given the facts of the

case.

The trial judge in Petitioner's case was faced with the

"stark resulting phenomenon" (See Avery, 345 U.S. at 564) of

zero Blacks out of 40. Petititioner's trial counsel, upon

seeing the venire not only objected, he moved to dismiss the

array or for a hearing to determine how this obvious underre

presentation occurred. Moreover, counsel supplied the court

with an explanation for the underrepresentation (the "conveni

ence" system) and informed the judge he was aware of its use

10

Counsel even wentfrom another case from the same courthouse.

further and read into the record the names of the communities

in which the members of Mr. Davis' venire resided, demonstrat

ing that many came from the predominantly white northwest side

of Chicago and 10 northern suburbs.** Counsel then asked the

judge to determine if anyone volunteered. The state objected

and trial judge refused to inquire.

The majority holds it cannot fault a state trial judge

with a "full docket" for failing to inquire based on this

showing.•k k k However, it would have taken less than a

*The majority faults counsel for not instantly providing

the name of the other case. Counsel's representation as an

officer of the court was entitled to be credited, however. In

fact counsel ultimately supplied the name of the other case,

and a transcript demonstrating, as he had stated, that

convenience factors were used.

* *Inexplicably, the majority opinion states the record

contains "no information regarding the residen es of the

members of the venire" and sugests counsel should hive made an

offer of proof. Davis p.26 ftnt 14. But this it; precisely

what counsel did! He stated that the jury cards showed the

jurors r^si_deci in "Des Plaines, Mt. Prospect, Winnetka,

Glenview, Skokie, Palatine, Schiller Park, WilmetteJJ Brookfield

and mostly from the northwest side of Chicago " Is the

majority stating he should have gone further and ha re read the

street addresses into the record? If so what more would this

have added? (slip opinion p. 25) Also, it may be more than

geography that caused whites to volunteer for jury duty in the

overwhelmingly white suburbs. Perhaps white j irors from

Chicago were more "comfortable" in going to a white suburb than

a racially diverse neighborhood such as 26th Stree ;. Reading

the residences of jurors would not explain this pherimenon. The

fact remains there was only one way to find out if anyone

volunteered and that was to ask.

***There's absolutely no evidence concerning th||s docket of

the trial Judge in Davis and the majority's conlfclusion is

wholly speculative. However, full or not, Sixth Amendment

gaurantees may not be abrogated because it may be time con

suming to insure a fair trial.

11

minute to determine if anyone had actually volunteered. A

general question to the whole venire (e.g. "Those who

volunteered or were asked to volunteer to come here please

raise your hands?") would have resolved the issue. The failure

of the judge to make this simple inquiry foreclosed forever the

ability to demonstrate that anyone volunteered. The jury cards

did not reflect this information, and according to the jury

commissioner's deposition there was no way to tell who

volunteered from any panel of jurors. There was only one way

to find out; ask, and to this the state objected and the state

judge upheld the objection and refused to inquire.

Supreme Court precedent has never required as the majority

Panel does here, that for purposes of establishing a prima

facie case a Defendant after demonstrating a significant

underrepresentation and pointing to a selection procedure that

would account for the underrepresentation, to go further and

prove a particular juror was actually affected by it. But even

assuming that this unprecadent burden was correctly placed on

the Petitioner in this case, to hold Mr. Davis responsible for

failing to supply the missing link (a juror who actually

volunteered) that the majority holds was critical to his case,

when his trial counsel attempted to secure this very

information and by the actions of the state court judge and

state's attorney was prevented from establishing this point,

simply is not fair.

12

Conclusion

If a venire representing a fair cross section of the

community is truly an essential component of a fair trial then

it is a requirement that must be vigilently enforced. Unfor

tunately the majority's opinion in this case while recognizing

the importance of the requirement in principle effectively

precludes the provision's enforcement by holding that the

state need not bother to explain the absence of Blacks from a

jury venire and trial judges are not required to inquire until

after the defendant has explained away every conceivable legi

timate explanation for the underrepresentation. This burden is

in conflict with all prior Supreme Court decisions and

therefore Rehearing or Rehearing en banc should be granted and

the judgment reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Dated: February 15, 1989

PETER J. SCHMIEDEL

343 S. Dearborn #1607

Chicago, IL 60604

(312) 663-5046

Attorney for Petitioner-Appellee

13