DeRonde v. University of California Regents Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. DeRonde v. University of California Regents Brief Amicus Curiae, 1980. e41b37a8-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bb1418ab-0f78-4101-a302-bc70b6938f47/deronde-v-university-of-california-regents-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

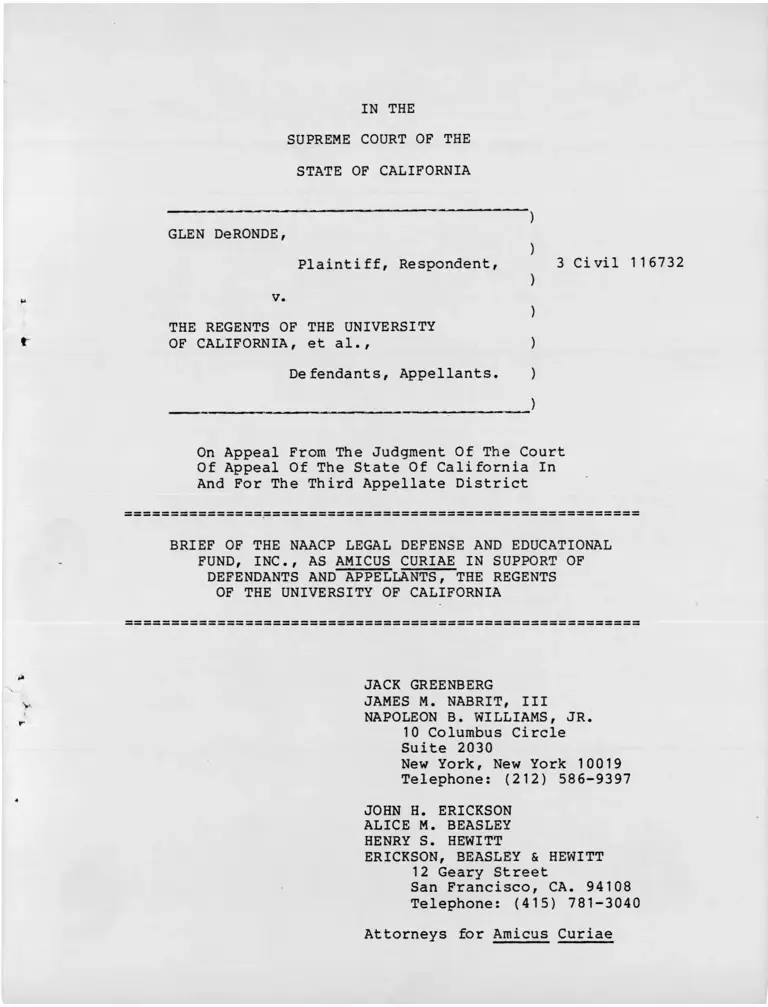

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

r

GLEN DeRONDE,

)

)

Plaintiff, Respondent,

)

v.

)

THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF CALIFORNIA, et al., )

3 Civil 116732

Defendants, Appellants. )

)

On Appeal From The Judgment Of The Court

Of Appeal Of The State Of California In

And For The Third Appellate District

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

DEFENDANTS AND APPELLANTS, THE REGENTS

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

V

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Telephone: (212) 586-9397

JOHN H. ERICKSON

ALICE M. BEASLEY

HENRY S. HEWITT

ERICKSON, BEASLEY & HEWITT

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, CA. 94108

Telephone: (415) 781-3040

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............................. m

STATEMENT OF FACT ................................. 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............. 4

ARGUMENT .......................................... 4

I. THE JUDGMENT BELOW SHOULD BE VACATED

AND THE ACTION DISMISSED BECAUSE OF

MOOTNESS .................................. 5

II. THE UNIVERSITY'S REMEDIAL USE OF RACE

CONSCIOUS ADMISSIONS CRITERIA IS A

PERMISSIBLE MEANS FOR ELIMINATING THE

EFFECTS OF PRIOR DISCRIMINATION ......... 7

A. Applicable Legal Standards .......... 7

B. History of Official Discrimination

Against Blacks and Other

Minorities ........................... 1 1

C. Compliance With the Price

Standards ............................ 22

III. THE LAW SCHOOL'S USE OF RACE CONSCIOUS

ADMISSIONS CRITERIA IS A LEGITIMATE

MEANS TO FURTHER IMPORTANT AND COMPELLING

INTERESTS OF THE STATE ................... 2 6

CONCLUSION ........................................ 33

Page

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Associated General Contractors of Massachusetts,

Inc. v. Altshuler, 490 F .2d 9 (1st Cir.

1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957

(1974) ..... 77777."................................................... 1 5

Bakke v. Regents of the University of

California, 18 Cal.3d 34 (1976) ............. 6,26

Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 94 (N.D.

Cal. 1 969) ................................... 1 2

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

("I 954) ........................................ 2, 1 3, 1 4,

1 5

Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215 (D.

D.C. 1 976) ................................... 1 2

Consol. Etc. Corp. v. United A. Etc. Workers,

27 Cal.2d 859 (1 946) ........................ 5

Crawford v. Board of Education, 17 Cal.3d

280, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d

28 ( 1 976) .................................... 1 2

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 ( 1 974) ........ 5

Gay Law Students Assn. v. Pacific Telephone

& Telegraph Co., 24 Cal.3d 458, 156

Cal. Rptr. 1 4, 595 P.2d 592 ( 1 979) ......... 28

Green v. County School of Board of New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1 968) ............ 14

Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S. 1215

(1971) ....................................... 18

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District,

59 Cal.2d 876, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382

P. 2d 878 ( 1 963) (en banc) ................... 12

Page

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School

District, 339 F. Supp. 1315 (N.D. Cal.

1971) vacated and remanded, 500 F .2d

349 (9th Cir. 1 974 ) ......................... 12, 1 8,1 9

- i i -

Page

Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701 (D.C.

Cir. 1 974) ................................... 12

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, 413

U.S. 1 89 ( 1 973) ............................. 1 5

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 ( 1 954) .............. 1 6

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145

( 1 965) ....................................... 1 4

People ex rel. Lynch v. San Diego Unified School

District, 19 Cal. App.3d 252, 96 Cal.

Rptr. 658 (Ct. App. 1971) cert, denied

405 U.S. 1 016 ( 1 972) ........ '. . ............. 12

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

U.S. 637 ( 1 950) ............................. 2

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) ........ 13,14,15

NAACP v. San Bernardino City Unified School

District, 17 Cal.3d 311, 130 Cal.

Rptr. 744, 551 P. 2d 48 ( 1 976) ............... 1 2

Paul v. Milk Depots, Inc., 62 Cal.2d 129

( 1 964) ....................................... 5,6

Pena v. Superior Court, 50 Cal. App.3rd 694,

123 Cal. Rptr. 500 (Ct. App. 1 975) ......... 1 2

People v.. Riles, 343 F. Supp. 1306 (N.D.

Cal. 1972), affirmed, 502 F.2d 963

(9th Cir. 1 974) .............................. 1 1

People v. San Diego Unified School District,

19 Cal. App.3d 252, 96 Cal. Rptr. 658

(Ct. App. 1971) ............................. 11

Price v. Civil Service Commission of Sacramento

County, Cal.3d , 161 Cal. Rptr.

475, 604 P. 2d 1365 (1 980) ............... 2, 7,8,9, 10, 17,

23,24,25,26,27,

28,29,31,32,33

Regents of the University of California v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) ................. 2,26,30,31

- iii -

San Antonio Ind. School District v. Rodriquez,

411 U.S. 1 ( 1 973) ........................... 28

Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal.3d 584, 96 Cal. Rptr.

601 , 487 P. 2d 1 241 ( 1 971 ) ................... 28

Santa Barbara School District v. Superior

Court, 13 Cal.3rd 315, 118 Cal. Rptr.

637, 530 P.2d 605 ( 1 975) (en banc) ......... 12

Soria v. Oxnard School District Board of

Trustees, 386 F. Supp. 539 (C.D. Cal. 1974),

on remand from 488 F .2d 577 (9th Cir. 1973),

cert, denied 416 U.S. 95 ( 1 974) ............. 1 2

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education,

311 F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1 970) .......... 1 1

Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1 947) ............... 1 4

United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO v.

Weber, 443 U.S. 1 93 ( 1 979) .................. 26

Wysinger v. Crookshank, 82 Cal. 588,

23 P. 54 ( 1 890) ............................. 1 7

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions

Constitution of the United StatesArt. VI, § 2 ................................. 14

Fourteenth Amendment ........................

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e .................. 9

Constitution of the State of California

Article I, section 7 ........................ 10,15

General School Law of California, § 1662

at 14 (1 880) ................................. 17

Page

- i v -

Page

1860 c. 329, § 8 .................................. 17

1 863 c. 159, § 68 17

1 885 c. 1 17, 1662 ................................ 17

1893 c. 193, §1 662 ................................ 17

1921 c. 685, § 1 ................................... 17

1947 c. 737, § 1 ................................... 17

Sacramento County Civil Service Commission

Rule 7.10 .................................... 9,10

Books

I. Hendrick, The Education of Non-Whites in

California, 1849-1970 (1977) ... ............ 12,17

C. Wollenberg, All Deliberate Speed, Segregation

and Exclusion in California Schools,

1855-1 9*7 5 ~( 1 97 6 ) .... . . . . .'.7 .7 .7 . 7.......... 12,17

Other Authorities

California Legislature, Assembly Permanent

Subcom. on Post Secondary Education, Unequal

Access to College (1975) .................... 13,18,22,32

California Assembly Concurrent Resolution

No. 1 51 , 1 974 ............................... 1 9,21,32

California Legislature, Joint Committee on

Higher Education, The Challenge of Achieve-

ment: A Report on Public and Privace

Higher Education in California 77

(1 969) ....................................... 2 0 , 2 2

v

Page

California Legislature, Joint Committee on the

Master Plan for Higher Education, Report

No. 33,37 ( 1 973) ............................ 21

California Coordinating Council for Higher

Education, J. Kitano & D. Miller, An

Assessment of Educational Opportunity

Programs in California Higher Education(1 970) ....................................... 23

California Postsecondary Education Commis

sion, Planning for Postsecondarv Education

in California: A'Five "Year Plan Update,

1 977-1 978, 32-34 ( 1 977)“. .. . .7777777777..... 20

California State Department of Education,

Racial and Ethnic Survey of California

Public Schools, for Fall T963" "(1 967)

Fall 1968'"(1969) and Fall 1970 (1971) ...... 16,18

Center for National Policy Review, Trends

in .Black School Segregation, 12970-1974, Vol. I

( 1 977) and Trends in His'panic Segregation.

1 970-19 7 4, voTV 'll (1977) ............ 7777... 16

Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots,

Violence in the City; 49 et seq., (1965) ___ 13,18

HEW's Directory of Public Elementary and

Secondary Schools in Selected Districts,

Enrollment and Staff By Racial/Ethnic

Groups, for Fall 1968 (1970) Fall 1970

(T972), and Fall 1972 (.1974 ) 777777777...... 16

22 Cal. Dept, of Justice, Opinions of the

Atty. Gen., Opinion 6735a (January

23, 1 930) at 931-932 ........................ 1 7

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical

Statistics of the United States, Colonial

Times to 1970,'Pa~rt 1, 25 (1 976) ......... . 16

U.S. Bureau of Census, 1970 Census of Popula

tion, Series PC (2)-2A State of Birth337“ 61 (1 973) ................................ 16

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current_Population

Reports, Series P-23, No. 46; The Social

and Economic Status of the Black

Population in the United States, 1972 at

(1973) --- ...----77.'.';.... .............. 16

vi

Page

Bureau of the Census' Statistical Abstract

of the United States, 1976, p. 133 (1976) ... 16

United States Civil Rights Commission, Mexican-

American Education Study Reports

I-VI (1 971-1974) ............................ 13, 18

VI1

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

GLEN DeRONDE, )

Plaintiff, Respondent, ) 3 Civil 116732

v.

)THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF CALIFORNIA, et al., )

Defendants, Appellants. )

)

On Appeal From The Judgment Of The Court

Of Appeal Of The State Of California In

And For The Third Appellate District

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

DEFENDANTS AND APPELLANTS, THE REGENTS

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

1. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a nonprofit corporation established under the laws

of the State of New York.

It was formed to assist black persons in securing their

constitutional and other civil rights by prosecuting and

defending lawsuits. Its charter declares that its purposes

include rendering legal services gratuitiously to Negroes

suffering injustice by reason of racial discrimination. For

many years, attorneys for the Legal Defense Fund have

represented black persons seeking to achieve equal oppor

tunity in public education, e.g., Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954); McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents,

339 U.S. 637 (1950). As part of this representation, attor

neys for the Legal Defense Fund filed an amicus curiae brief

for consideration by the Supreme Court of the United States

in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S.

265 (1978).

The Legal Defense Fund believes that its litigation

experience in the fields of discrimination, public education,

and affirmative action may be of assistance to the Court in

the present case. This amicus curiae brief is filed pursuant

to the Court’s order of April 28, 1980. It supports the

position of the defendants in this action.

STATEMENT OF FACT

For the purposes of this brief, amicus curiae accept the

facts as stated by the Court of Appeal below. Because that

court held that the admissions criteria of the School of Law

of the University of California at Davis contravened article I,

section 7 of the California Constitution, but did not violate

federal requirements as set forth in Regents of University of

California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), the scope of this o f ’

amicus curiae brief is limited to the narrow question of whether

the implementation of the University's admissions criteria con-

2

stitutes a violation of California State law, as determined

by article I, section 7 of the State Constitution.

In making its decision below, the Court of Appeal

ignored the history of discrimination against minorities

committed by educational institutions of the State of Califor

nia. Because this history is relevant for understanding the

remedial purposes of the Law School's affirmative action

program, we have endeavored in this brief to set forth

judicially cognizable facts concerning the nature and extent

of prior discrimination against minorities in California.

These facts, we contend, demonstrate that the Law School's use

of race conscious admissions criteria is reasonable and

permissible under the State Constitution. Furthermore, they

show that the lower court erred when it held that this

Court's recent decision in Price v. Civil Service Commission

of Sacramento County, _ __ Cal.3d ___, 161 Cal. Rptr. 475, 604

P.2d 1365 (1980), was inapplicable to the facts of this case.

Finally, it is submitted that these facts evidence

the existence of a parallelism between historical practices

in California of racial discrimination against minorities

and similar historical practices across the nation of racial

discrimination against minorities. Thus, the facts show

that there is no basis in reason for interpreting the equal

protection guarantees of the California Constitution to

be more restrictive than the federal equal protection clause

of the remedial use of race conscious affirmative action

programs for minorities.

3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Several reasons exist for vacating the judgment below

and dismissing the action.

First, plaintiff's graduation from law school deprives

the Court of any substantial reasons for deciding the merits

of this case and requires instead that the lower court's

judgment be vacated and the action dismissed for mootness.

Second, the race conscious admissions policy of the

School of Law of the University of California is, under

California law, a reasonable means for discharging the

State's duty to eradicate the lingering, injurious conse

quences of racial discrimination.

Third, the Law School's remedial use of race conscious

admissions criteria represents a legitimate attempt, based

upon judicial, executive, and legislative findings, to

satisfy lawful governmental and educational purposes.

ARGUMENT

I. THE JUDGMENT BELOW SHOULD BE VACATED AND

THE ACTION DISMISSED BECAUSE OF MOOTNESS

The judgment entered below should be vacated and the

action dismissed on grounds of mootness. Plaintiff prayed

for an order declaring his entitlement to admission to the

School of Law at the University of California at Davis, and

for an injunction ordering defendants to admit him to the

4

School of Law. The complaint, however, failed to include aVclaim for damages.

At trial, plaintiff testified that following his rejec

tion for admission by the defendant School of Law, he intended

to enroll at the University of San Diego School of Law (R.T.,

p. 17). He duly enrolled in the San Diego School of Law and

2/

subsequently graduated from there.

In light of plaintiff's graduation from law school

the action has become moot and should be dismissed. See

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974). It has been the

consistent holding of this Court that the state courts of

California are not to be used for the purpose of addressing

moot questions or deciding abstract propositions. Consol.

Etc. Corp. v. United A. Etc. Workers, 27 Cal.2d 859, 863

(1946). This principle was affirmed in Paul v. Milk Depots,

1/ At the conclusion of the trial, plaintiff moved to

amend his complaint to include a claim for damages. The

motion was denied on the ground that plaintiff had acted

unwarrantedly in delaying the filing of his claim for

damages. The court also denied the motion on the ground that

plaintiff had, in fact, suffered no damages. The Court of

Appeal below found that the trial court had not abused its

discretion in denying the motion on these grounds.

2/ During his enrollment at the University of San Diego

School of Law, plaintiff applied for transfer to the School

of Law of the University of California at Davis for enroll

ment there during his second year. However, he subsequently

withdrew the application before it had been considered by the

Law School (C.T. Vol. II, pp. 49-54).

5

I_nc. , 62 Cal. 2d 1 29 (1964), where an action raising the issue

of the power of the California Department of Agriculture to

fix minimum prices was ordered dismissed after the plaintiff

had lost its license to do business. The Court stated there

that

It is settled that "the duty of this Court,

as of every other judicial tribunal, is to

decide actual controversies by a judgment

which can be carried into effect, and not

to give opinions upon moot questions or

abstract propositions, or to declare prin

ciples or rules of law which cannot affect

the matter in issue in the case before it."

Paul v. Milk Depots, Inc., supra, 62 Cal.2d at 132. The

principle stated in Paul, supra, is equally applicable to the

facts of the present case.

Moreover, there are no special circumstances present

here which would support making an exception to this general

rule. While it is possible that the issue raised here by the

plaintiff may be recurrent, there is no need to decide the

facts of this particular case since the issue is not one

which will necessarily evade judicial review as a result of

mootness. See this Court's opinion in Bakke v. Regents of

the University of California, 18 Cal.3d 34 (1976). Thus,

there is no reason here to make an exception to the general

rule requiring the dismissal of moot actions.

6

II. THE UNIVERSITY'S REMEDIAL USE OF RACE CONSCIOUS

ADMISSIONS CRITERIA IS A PERMISSIBLE MEANS FOR

ELIMINATING THE EFFECTS JOF PRIOR DISCRIMINATION _

A . Applicable Legal Standards

In Price v. Civil Service Commission of Sacramento

County, ___ Cal.3d ___, 161 Cal. Rptr. 475, 604 P.2d 1365

(1980), this Court set forth the legal principles, as deter

mined by State law, governing the validity of remedial, race

conscious, affirmative action programs. It held that public

agencies of the State of California may, consistently with

the laws of California and the United States, voluntarily

adopt race conscious, affirmative action programs, including

the use of goals and timetables, for the purpose of alleviat

ing underrepresentation of minorities caused by past dis

criminatory practices of the State.

The decision in Price, supra, supports the validity

of affirmative action programs involving the use of admis

sions criteria which permit universities to give favorable

consideration to an applicant's status as a member of a

minority group in determining the applicant's eligibility of

admission. Under the Court's rationale in Price v. Civil

Service Commission of Sacramento County, supra, the use by

admissions officers of race conscious admissions criteria

is proper if used for the purpose of reducing the under

representation of minorities in higher education which exists

by virtue of the injurious effects of racial discrimination.

The decision in Price, supra, is therefore an adequate basis

7

for sustaining the Law School's use of its race conscious

admissions criteria.

In Price, supra, the Sacramento County Civil Service

Commission conducted in 1974 an extensive investigation of

the county's past hiring practices. the investigation showed

that the traditional civil service selection procedures,

including the use of alleged objective written examinations,

operated to discriminate against minorities. The Commission

found, and the Court in Price affirmed, that the County's

written civil service examinations frequently bore little or

no relationship to the requirements of the employment posi-

tions for which the examinations were allegedly designed.

As a result of the County's discriminatory practices,

members of minority groups were substantially underrep

resented in the workforce of Sacramento County. To counter

the effects of the discrimintory practices, the Commission

adopted a regulation which required that adjustments be made

in the disproportionate representation of minority personnel

in the County's employment caused by prior discriminatory

employment practices.

As part of its implementation of the regulation, the Com

mission announced that it would require, where appropriate,

public agencies of the county to hire minority persons on a

preferential basis from an eligible list. The Commission

further provided that any program of preferential hiring for

minorities adopted by a public agency in pursuance to the regula

tion must terminate in any job classification once a fair

8

approximation of minority representation, consistent with the

pupulation mix of the County of Sacremento, existed in the

3/

classi fication.

When the Commission sought to compel compliance with

its rules by the County's district attorney's office, the

latter commenced an action in the trial court below to

declare the Commission's rules and procedures to be in

violation of local, state, and federal laws. This Court

rejected the challenge. It held that the preferential hiring

program satisfied the requirements of local law, California's

statutes, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.S. § 2000e, and the Constitutions of Califor

nia and the United States. In upholding the Commission's

actions, the Court said:

Inasmuch as the Commission after a duly

authorized investigation ... determined

that it had grounds to suspect that the

County's past competitive examinations

had had a racially discriminatory effect

and that such examinations were not job-

related, we have no doubt that the Com

mission's enforcement authority empowered

it to take action to remedy the situation.

Under these circumstances, the promulgation

of an affirmative action plan, directed spe

cifically at ameliorating minority under

representation which is found to have re

sulted from the County's own discriminatory

employment practices, falls within the

authority of the Commission.

3/ Rule 7.10 of the Sacramento County Civil Service Com

mission. Rule 7.10 also provided, the Court noted, for

"'continuing oversight' ... so as to enable the Commission

to guarantee that the order ... will not impose undue bur

dens on ... interested parties". Price, supra, 604 P.2d at

1381. See also Rule 7.10(f) of the Sacramento County

Civil Service Commission.

9

Price, supra, 604 P.2d at 1372. In subsequent parts of its

opinion, the Court specifically noted that the equal protec

tion clause of the Constitution of the State of California

was not a bar to the adoption of affirmative action plans

promulgated in accordance with Rule 7.10. Price, supra, 604

P.2d at 1382, 1383.

This Court's decision in Price conclusively determined that

the equal protection provisions of the California State Con

stitution does not prohibit a public agency's use of a race

conscious affirmative action program to alleviate an under

representation of minority groups attributable to prior dis

crimination by public agencies of the State. The Court

recognized, however, that in attempting to design remedies to

eliminate the consequences of prior discrimination and to

correct an imbalance in minority representation, it would be

necessary to afford the State sufficient latitude to take

into account the present condition of minorities in the

State. In addressing itself to this problem, the Court

stated that:

Our past decisions construing Artitle I,

section 7, subdivision (a) reflect this

Court's recognition of the importance of

interpreting the provision in light of

the realities of the continuing problems

faced by minorities today. 4/

4/ Article I, section 7 of the California State Consti

tution reads as follows:

10

604 P.2d at 1382. It is submitted that the Law School's use

of race conscious admissions criteria is addresssed to the

"realties of continuing problems faced by minorities" today

in California, and that it is specifically designed to reduce

the extent of the underrepresentation of blacks, and other

minorities, caused by prior discrimination. The truth of

this assertion is borne out by the history in California of

extensive discrimination against minorities in the field of

public education. What follows constitutes a cursory review

of that history.

B. History of Official Discrimination Against Blacks

and Othe Minorities_______________________________

The history of racial discrimination against blacks and

other minorities in the public schools in California has been

well documented. See e.g., Spangler v. Pasadena City Board

of Education, 311 F. supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970). People v.

San Diego Unified School District, 19 Cal. App.3d 252, 96

Cal. Rptr. 658 (Ct. App. 1971); People v. Riles, 343 F. Supp.

1306 (N.D. Cal. 1972), affirmed, 502 F.2d 963 (9th Cir.

4/ cont'd.

(a) A person may not be deprived of life,

liberty, or property, without due pro

process of law or denied equal protection

of the laws.

(b) A citizen or class of citizens may not be

granted privileges or immunities not

granted on the same terms to all citizens.

Privileges or immunities granted by the

Legislature may be altered or revoked.

11

1974); Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701, 704 n.19 (D.C.

Cir. 1974); Soria v. Oxnard School District Board of Trustees,

386 F. Supp. 539 (C.D. Cal. 1974), on remand from 488 F .2d

577 (9th Cir. 1973), cert, denied 416 U.S. 95 (1974);

Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 94 (N.D. Cal. 1969); Brown

Vv. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215, 1223, (D. D.C. 1976).

In addition to judicial decisions evidencing the exis

tence in the State of wide-spread practices of official acts

of discrimination against minorities, there exists a consider

able body of the literature which also attests to the

pervasiveness of racial discrimination in California's

public schools. See, e.g., C. Wollenberg, All Deliberate

Speed, Segregation and Exclusion in California Schools,

1855-1975 (1976); I. Hendrick, The Education of Non-Whites in

California, 1849-1970 (1977). Thus, there is abundant

authority establishing the state-wide scope of racial

discrimination and showing the devastating impact of segrega

tion and discrimination upon the lives of minority group

5/ Also see Crawford v. Board of Education, 17 Cal.3d 280,

1*30 Cal. Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d 28 (1 976); People ex rel.

Lynch v. San Diego Unified School District, 19 Cal. App.3d

252, 96 Cal. Rptr. 658 (Ct. App. 1971), cert. denied 405

U.S. 1016 (1972); Jackson v. Pasadena City School District,

59 Cal. 2d 876, 31 CalT"Rptr.' "6'0'6,.J8'2"p"'.T3"878( 1 963)-----

(en banc); Pena v. Superior Court, 50 Cal. App.3rd 694,

123 Cal. Rptr. 500 (Gt. App. 1975); NAACP v. San Bernardino

City Unified School District, 17 Cal.3rd 31 1 , 130 Cal.

Rptr. 744, 551 P.2d 48 (9176); Santa Barbara School District

v. Superior Court, 13 Cal.3rd 315, 319, 118 Cal. Rptr. 637,

530 P. 2d 605 (T975) (en banc). See also Johnson v. San

Francisco Unified School District, 339 F. Supp. 1315 (N.D.

Cal. 1971), vacated and remanded, 500 F.2d 349 (9th Cir. 1974).

12

members. Moreover, these authorities, and others, show

that, as a result of school segregation, minority students

have suffered severe educational deprivations. See Governor's

Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, Violence in the City;

49 et seq. , ( 1 965); California Legislature, Assembly Per

manent Subcom. on Post Secondary Education, Unequal Access to

y — --------------------------------------

College (1975). The evidence shows that the impact

of segregation and discrimination has been particularly

harmful for the minority- students who are preparating for

enrollment in institutions of higher education. They are, in

several respects, hampered by their education in a segregated

»

environment.

In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), The

Supreme Court noted that primary and secondary education is a

"principal instrument in ... preparing (the child) ... for

later professional training." 347 U.S. at 493. Moreover,

the Supreme Court, in its decision in Brown v. Board of

Education, made elaborate findings of the far-reaching

effects which segregated education had upon the educational

and mental development of minority school children. For

example, with respect to minority children in grade and

high school, it found that:

To separate them from others of similar

age and qualifications solely because

of their race generates a feeling of

6/ Also, United States Civil Rights Commission, Mexican-

American Education Study Reports I-VI (1971-1974).

13

inferiority as to their status in the com

munity that may affect their hearts and minds

in a way unlikely ever to be undone....

347 U.S. at 494. Accordingly, it concluded

"Segregation of white and colored children

in public schools has a detrimental effect

upon the colored children. "Id̂ . 7/

The State has a duty to alleviate the effects of its own

discrimination. Under federal law, the public agency respon

sible for discrimination has the "primary responsibility" for

remedying it. Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 281 (1977).

8/

This is, of course, also the rule under State law. The

duty is to "eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past

as well as bar like discriminatory effects in the future."

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965). The

scope of the duty extends to the elimination of the vestiges

of past discrimination "root and branch." Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 438 (1968).

In assessing the extent of a State's obligation to

eliminate the consequences of past discrimination, public

officials, including public officials of California, must

realize that "discriminatory student assignment policies can

themselves manifest and breed other inequalities . . ."

7/ For some of the literature of the effects of school

segregation on minority students, see footnote 11, in Brown v.

Board of Education, supra.

8/ Under the Supremacy clause of the United States Con

stitution, Art. VI, § 2, the policy of a federal constitu

tional or statutory provision is "the prevailing policy

in every state." Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386, 392 (1947).

14

Milliken v. Bradley, supra, 433 U.S. at 283. As the Supreme

Court noted in the Denver school desegregation case, "common

sense dictates the conclusion that racially inspired school

board actions have an impact beyond the particular schools

that are the subjects of those actions." Keyes v. School

District No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189, 203 (1973). In par

ticular, the existence of discrimination and segregation at

the primary and secondary levels affects the availability

of educational opportunities at the higher educational level.

Brown v. Board of Education, supra, 347 U.S. a5 493.

Ascertaining the full extent of the effects of unlawful

discrimination, however, is not always a simple task.

There are many complexities in the situation. This is

especially true when the task is to redress the effects of

educational deprivations in primary and secondary schooling.

Because of the difficulties and the need to devise remedies

to existinguish the advise effects of unlawful discrimination,

the courts have recognized that "the discretionary power of

public authorities to remedy past discrimination is even

broader than that of the judicial branch." Associated General

Contractors of Massachusetts, Inc, v. Altshuler, 490 F .2d 9,

17 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974).

The pervasiveness of the effects in California of for

mer conditions of segregation and discrimination in the public

schools warrants the adoption of state-wide measures to redress

the continuing educational deprivation of minority students.

15

For example, in 1972, approximately three-quarters of the

black students in the elementary and secondary public schools

of California attended schools which were 50-100% black,

2 /Chicano, Asian or Indian." Moreover, substantial num

bers of black students, and other minority students, attended

schools in districts previously found to have been in viola-

^O/

tion of federal or state laws prohibiting school segregation.

Additionally, it should be noted, that a considerable portion

of the black students in California eligible for enrollment

in the University of California probably received a substan

tial part of their education in schools in Southern states

11/where conditions of d^ jure segregation existed. This fact

9/ Forty percent of the black students attended schools

which were 95-100% minority. Bureau of the Census' Satisti-

cal Abstract of the United States, 1976, p. 133 (1976); HEW's

Directory of Public Elementary and Secondary Schools in

Selected Districts, Enrollment and Staff By Racial/Ethnic

Groups, Fall 1968 (1T7fl77"F a rT~r?7Trm 7 2 )7 'and"~FafTT97?

(1974). Also California State Department of Education,

Racial and Ethnic Survey of California Public Schools,

for Fall 1'966 ( V967)T Fall Tf66'(1'969) and' YaTl T575" (1971);

Center for National Policy Review, Trends in Black School

Segregation, 1970-1974, Vol. I (1977) and Trends in Hispanic

Segregation, 19/0—1974, Vol. II (1977).

10/ See cases cited in footnote 5 and text accompanying same.

Also see Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1954); and HEW's

Directory of Public Elementary and Secondary Schools in

Selected Districts, Enrollment and Staff by Racial/Ethnic

Groups, Fall 1970, supra.

11/ According to Census reports, 42% of California's black

population was born in the South. See U. S. Bureau of Census,

1970 Census of Population, Series PC (2)-2A, State of Birth,

55, 61 (1973). Also, U. S. Bureau of the Census, Current

Population Reports, Series P-23, No. 46; The Social and

Economic Status of the Black Population in the United States,

1972 at 12 (1973); U. S. Bureau of the Census, Historical

Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1^70,

Part 1, 25 (1976).

16

is important in view of this Court's statement in Price

that article I, section 7 of the California Constitution

must be construed "in light of the realities of the continuing

problems faced by minorities today," Price, 604 P.2d at 1382.

The history of discrimination and segregation which11/has characterized the public schools of California justi

fies the adoption by this Law School, and other schools of

the University of California, of admissions criteria which

consider race as one of the factors requiring competitive 11/evaluation in the determination of eligibility for admission.

Indeed, an examination of the groups denominated by the Law

School as the minority groups whose members are entitled to

have their race taken into account for the purpose of admis

sion, shows that discrimination and segregation were practiced11/in the public schools against each group listed.

12/ At one time, California law specifically provided for

the maintenance of separate schools for blacks. 1860 Cal.

Stats., c. 329, § 8 ; 1863 Cal. Stats., c. 159, § 6 8, but

in 1880 the statute was repealed. General School Law of

California § 1662 at 14 (1880). The repeal, however, did

not end the practice of segregation and discrimination

against black students. See Wysinger v. Crookshank, 82

Cal. 588, 23 P. 54 (1890); I. Hendrick, supra, at 78-80,

98-100. The repeal of statutes permitting separate schools

for other minorities, however, did not occur until 1947. See

1947 Cal. Stats., c. 737, § 1.

13/ In other contexts, this Court has noted that "state

policy strongly favors the adoption of ... voluntary

affirmative action plans." Price, supra, 604 P.2d at 1372.

14/ Separate schools were once maintained for the various

racial groups. See 1885 Cal. Stats., c. 117 § 1662 (Chinese);

1893 Cal. Stats., c. 193, § 1662 (Indiana); 1921 Cal. Stats.,

c. 685, § 1 (Japanese); Mexican American were regarded as

Indians. 22 Cal. Dept, of Justice, Opinions of the Atty.

Gen. Opinions 6735a, (January 23, 1930) at 931-932.

17

Governmental bodies of the State of California have

confirmed the existence of past discrimination in the school

system and the denial of equal educational opportunities to

minorities in institutions of higher education. See e.g.,

Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, supra;

California Legislature, Assembly Permanent Subcommittee on15/

Postsecondary Education, Unequal Access to College, supra.

Furthermore, the California State Department of Education has

found that

despite efforts to implement the policies

of the State Board of Education and the

progress made by the Department of Education,

the task of eliminating segregation and pro

viding equal educational opportunities remains

formidable.

California State Department of Education, Racial and Ethnic

Survey of California's Public Schools, Fall 1966, iii (1967).

The failure of the State initially to make energetic

efforts to elininate the adverse consequences of prior dis

crimination was singled out by Justice Douglas in Guey v.16/

Heung Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S. 1215 (1971). He noted,

14/ cont'd.

The Law School's admissions program defined minorities as

"Native American, Black, Filipino, Asian, and Chicano."

15/ See also U. S. Civil Rights Commission, Mexican American

Education Study, Reports I-VI (1917-1974) and cases cited in

footnote 5 and text accompanying same.

16/ The district court's order in Johnson v. San Francisco

Unified School District, 339 F. Supp. 1315 (N.D. Cal. 1971)

was vacated by the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and

the action was remanded to the district court to determine if

the school board had acted with a discriminatory purpose. 559

F.2d 349 (9th Cir. 1974).

18

in a memorandum opinion denying an application by Americans

of Chinese ancestry for a stay of a district court order

reassigning pupils of Chinese ancestry in order to reduce

racial imbalance in certain schools in California, that the

district court had made

findings that plainly indicated the force

of the old polcy has persisted: "(T)he

school board ... had drawn school attend

ance lines, year ater year, knowing that

the lines maintain or heighten racial

imbalance." And further, that no evidence

has been tendered to show that since Brown I

"the San Francisco school authorities had

ever changed any school attendance line

for the purpose of reducing or eliminating

racial imbalance." 404 U.S. at 1216, quoting

from Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School

District, 339 F. Supp. 1315, 1319 (N.D. Cal.

1971).

In recent years, however, there has been accumulating

evidence of the State's interest in carrying out its consti

tutional function of eliminating the vestiges of discrimina

tion. A resolution has been enacted by the Legislature of

the State requiring the adoption, by educational authorities,

of steps to "overcom(e) .. ethnic ... underrepresentation in

the makeup of the student bodies of institutions of public

higher education." California Assembly Concurring Resolution

No. 151, 1974 Cal. Stats., Res. c. 209. Even prior to this

time the State had, acting through the University of California

in 1964-65, the California State University of Colleges in

1966-67, and the California Community Colleges in 1969-1970,

19

instituted undergraduate "Equal Opportunity programs" to

increase opportunities for socio-economically disadvantaged

students. Experience, however, was later to show that these

programs were not sufficient to provide for equal educational

opportunities for minority students in higher education. See

e.g., California Legislature, Joint Com. on Higher Education,

The Challenge of Achievement; A Report on Public and Private

Higher Education in California 77 ( 1 969); California Post-

secondary Education Commission, Planning for Postsecondarv .

Education in California; A Five Year Plan Update, 1977-1972,

32-34 (1977). In light of this failure, the University of

California turned to the adoption of affirmative actions

programs. California Postsecondary Education Commission,

supra, 43-34.

The California Legislature has clearly perceived that a

connection exists between the quality of education made

available in the primary and secondary schools of the State

and the ability of graduates of those schools to obtain

admission to institutions of higher education. In a report by

one of its committees, of the Legislature found that:

(E)quality of opportunity in post-secondary

education is still a goal rather than a

reality. Economic and social conditions and

early schooling must be significantly improved

before equal opportunity can be realized. But

there is much that can be done by and through

higher education.

17/

17/ These programs provided assistance in the areas of re

cruitment, tutoring, financial aid, etc. California Post

secondary Education Commission, supra, 32-34.

20

California Legislature, Joint Committee on the Master Plan

for Higher Education, Report 33, 37 (1973). Following thi

report, the Legislature adopted Assembly Concurrent Resolu

tion No. 151 (1974). This Resolution provides, in part,

as follows:

"WHEREAS, The Legislature recognizes

that certain groups, as characterized by

sex, ethnic, or economic background, are

underrepresented in our institutions of

public higher education as compared to the

proportion of these groups among recent

California high school graduates; and

"WHEREAS, It is the intent of the

Legislature that such underrepresentation

be eliminated by providing additional

student spaces rather than by rejecting

any qualified student; and

"WHEREAS, It is the intent of the

Legislature to commit the resources to

implement this policy; and

"WHEREAS, It is the intent of the

Legislature that institutions of public

higher education shall consider the fol

lowing methods for fulfilling this policy;

(a) Affirmative efforts to search

out and contact qualified students.

(b) Experimentation to discover

alternate means of evaluating student

potential.

(c) Augmented student financial

assistance programs.

(d) Improved counseling for dis

advantaged students;

now, therefore, be it

"Resolved_by_ the Assembly of the State

of California, the Senate thereof con

curring, That the Regents of the Uni

versity of California, the Trustees of

the California State University of Col

leges, and the Board of Governors of

the California Community Colleges are

hereby requested to prepare a plan that

will provide for addressing and over

coming, by 1980, ethnic, economic, and

sexual underrepresentation in the make

up of the student bodies of institu

tions of public higher education as com

pared to the general ethnic, economic,

and sexual composition of recent Califor

nia high school graduates ..."

Following the adoption of this Resolution, it was noted

by one of the Committees of the Legislature that

"In adopting Assembly Concurrent Resolution 151 (1954),

the Legislature acknowledged that additional effort

by colleges and universities is necessary to over

come underrepresentaion of ethnic minorities and the poor. 18/

California Legislature, Assembly Permanent Subcom. On Post

secondary Education, supra, Unequal Access To College 1 (1975).

C . Compliance With The Price Standards

This review of the history of discrimination in Califor

nia and the State's response to it demonstrates several

points. First, it shows that there is ample proof that

discrimination in California against minorities has been

continuous and systematic in the field of public education.

Second, it establishes that discrimination against minorities

in primary and secondary education has caused minority

students to suffer educational deprivation at these levels

18/ The Report of the Joint Committee on the Master Plan

for Higher Education, supra, at 38, had recommended that:

Each segment of California public higher

education shall strive to approximate by

1980 the general ethnic, sexual, and eco

nomic composition of the recent California

high school graduates.

22

and in higher education. Third, it shows the reasona

bleness of efforts to eradicate vestiges of discrimination by

adopting race conscious policies in higher education.

Fourth, it shows that the Law School's use of a race conscious

admissions criteria is in consonance with State policy as

defined by the Legislature and required by the courts. There

is therefore, in view of this history and the conformity of

the Law School's action to State policy, an adequate basis

for this Court to find that the Law School's adoption of a

remedial, race conscious admissions program is in compliance

with the Court's decision in Price v. Civil Service Commission

of Sacramento County, supra.

It was conceded below that admission to the Law School

of the University of California at Davis is governed by

a variety of different criteria. The criteria determining

admissions included the use of the following factors: (1 ) the

predicted first year academic grades (PFYA) based upon the

college grade point average and the score of the Law School

Admissions Test (LSAT); (2) growth, maturity, and commitment

to law study; (3) previously existing factors, such as

temporary handicaps and changes in school environment, which

19/

I V The California Coordinating Council for Higher Education,

subsequently renamed the California Postsecondary Education

Commission, found that: "(0)ne of the most serious blocks

to participation in higher education for minority students

occurs in the secondary educational system." California

Coordinating Council for Higher Education, H. Kitano & D.

Miller, An Assessment of Educational Opportunity Programs

in California Higher Education (1970)' at ~3.

23

adversely affected grades; (4) evidence other than grades and

LSAT scores which indicate ability and motivation; (5) ethnic

20/

minority status, and (6 ) economic disadvantage. No

quotas were applied by the Law School with respect to its

admissions criteria. Ethnic minority status was merely one

of the factors which admissions officers could take into

account.

Testimony offered at trial by Professor Edward L.

Barrett, who was the founding Dean of the Davis Law School,

established that it was necessary to give consideration to

ethnic minority status in the Law School's admissions criteria.

Such consideration was necessary, he testified, (1) to insure

that the legal profession in California encompassed a "reason

able cross section of society" (R. T., p. 155); (2) to

obtain a class in the law school that "reflects, to a signifi

cant degree, the community at large (C. T. Vol. I, p. 71);

and (3) to insure that the Law School would not "exclude

from the legal profession, under the current circumstances,

the greatest bulk of the minority applicants" (R. T., p.

157). Professor Barrett testified emphatically that without

the use of race conscious criteria, minority students

"would not get into the law school and they would not get

into the legal profession". (R. T., p. 157).

On these facts, this Court's decision in Price, supra, is

determinative. The proof of discrimination against minorities

20/ See footnote 14, supra.

24

in the field of public education is overwhelming. Indeed, it

is confirmed by the findings of virtually every agency of

State government which has considered the problem. Under

these circumstances, Price requires that California's

constitutional and statutory laws not be used to prohibit or

frustrate reasonable application of race conscious criteria

to remedy underrepresentation of minorities substantially

caused by official acts in California of racial discrimination.

This holding in Price is clear and unequivocal. Examining

the underlying need for affirmative action programs, this

Court noted in Price, supra, that:

Only in the last quarter century ... have

we undertaken a serious and concerted effort

to eliminate the pervasive discrimination

long endured by minorities in our society ...

We have found that affirmative steps are at

time necessary to overcome the legacy of past

degredation of minorities and to bring minor

ities into full membership in American society.

One such instance of that essential affir

mative action is the correction of an em

ployer's past discriminatory employment prac

tice by a race-conscious ... program ...

Price, supra, 604 P.2d at 1383. Given this declaration by the

Court, it is clear that the holding of Price is applicable in

the field of higher education and that therefore the lower

court erred in refusing to apply Price to the facts of this

case. On this ground alone, the judgment below should be

vacated and the action dismissed.

This result is especially necessary since the Law School's

use of its race conscious admissions criteria does not unnecessarily

25

trammel upon the interests of white applicants for

admission. The record shows that the Law School has made

every effort to insure that all qualified applicants are

given an individual assessment of their worth, quality, and

potential contribution. Furthermore, as Professor Barrett's

testimony establishes, the Law School's use of the special

admissions criteria will terminate once there is no longer an

underrepresentation of minorities in the Law School (R. T.

pp. 154-157). The application of Price, supra, is, under

these circumstances, clear. There can be no doubt that the

requirements set forth in Price for sustaining the use of

race conscious criteria are satisfied. Accordingly, the

decision of the Law School to employ its admissions criteria

to lessen the effects upon minority students of prior dis

crimination committed against them must be sustained.

11/

III. THE LAW SCHOOL'S USE OF RACE CONSCIOUS

ADMISSIONS CRITERIA IS A LEGITIMATE MEANS

TO FURTHER IMPORTANT AND COMPELLING

INTERESTS OF THE STATE

The vice of the holding below was the assumption by the

court of appeal that the Law School's admissions program, while

concededly validly under the Fourteenth Amendment's equal pro

tection clause, see Regents of the University o f California

21/ The avoidance of an affirmative action plan which

unnecessarily trammels upon the interests of whites is

one of the requirements for validity suggested in United

Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 1 93, 20"8 (1 979) .

26

v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), was invalid under the State Con

stitution's equal protection provision. This assumption,

however, was in direct contradiction with this Court's asser

tion in Price, supra, that there is

... no authority which suggests that the

California equal protection clause should

be interpreted to place greater restric

tions on bona fide affirmative action

programs than are imposed by the Four

teenth Amendment. To the contrary, our

past decisions construing Article I, sec

tion 7, subdivision (a) reflect this Court's

recognition of the importance of interpret

ing the provision in light of the realities

of the continuing problems faced by

minorities today.

Price v. Civil Service Commission of Sacramento County,

supra, 604 p.2d 1382. Consequently, there was no basis for

the court of appeal to conclude that proof of prior discrimi

nation by the agency erecting the affirmative action program

was an indispensable requirement under state law for the

validity of the program.

While the State's equal protection clause must generally

be construed to protect the same basic rights and privileges

as those protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, it must,

nevertheless, be conceded, as this Court has recognized, that

there are times when

... the state equal protection guarantee

embodied in Article I, section 7, subdivi

sion -*(a) of the California Constitution

does provide safeguards separate and dis-

27

tinct from those afforded by the Four

teenth Amendment, ..." 22/

Price, supra, 604 P.2d at 1382.

Although initially this, might appear to be inconsistent

with this Court's aforementioned statement in Price, supra,

as well as inconsistent with this Court's earlier declaration

that "We have construed these provisions as 'substantially

and equivalent' of the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment to the federal Constitution", Serrano v.

Priest, 5 Cal.3d 584, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601, 487 P.2d 1241, n.11

(1971), the conflict is apparent only. With respect to the

allowable scope of governmental programs providing for

remedial use of race conscious criteria, the conflict may be

resolved by recognizing that California's enforcement of its

equal protection guarantee will diverge from the requirements

of the federal equal protection clause only when conditions

and circumstances relevant to both differ substantially in

the State of California from those which exist nationally.

Compare, for example, Serrano v. Priest, supra, with San

Antonio Ind. School District v. Rodriquez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973).

Also see Price, supra, 604 P.2d at 1376.

22/ See, e.g. , Gay Law Students Assn, v. Pacific Tele

phone & Teleqraph_Co., 24 Cal.3d 458, 469, 1?6 Cal. Rptr.

14, 595 P.’fd (1*979). Compare Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal.3d

584, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601 , 487 P. 2d 1241 (1971*)* with San Antonio

Ind. School District v. Rodriquez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973).

28

This Court applied the essence of this principle in

Price, supra. The plaintiff there argued that the Commis

sion's affirmative action provisions violated both Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act and local laws prohibiting dis

crimination. After rejecting the plaintiff's argument that

the defendant's actions contravened Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act, the Court in Price similarly rejected the plain

tiff's assertion that the affirmative action program violated

local antidiscrimination laws. In explaining its actions the

Court stated that:

Although the United States Supreme

Court's interpretation of the antidis

crimination provisions of Title VII does

not, of course, necessarily determine the

appropriate interpretation of the anti-

discrimination provisions of the Sacramento

County Charter or the FEPA, we believe tht

those provisions should similarly not be

interpreted to bar all such race-conscious

affirmatie action plans. First, the

relevant provisions of both the country

charter and the FRPA arose out of the same

historical context as the federal Civil

Rights Act and were intended to achieve

the same general objectives as the anti-

discrimination prohibitions contained

in the federal law.

Price, supra, 604 P.2d at 1376.

The same analysis is, of course, applicable to alleged

differences in treatment of affirmative action programs by

the State and federal constitutional provisions for equal

protection. Both equal protection clauses arose out of the

same historical context and both, in dealing with discrimina

tion against blacks, are concerned with the same historical

29

problems. Moreover, both must confront the same obstacles

existing today in society to creating equal opportunity for

minorities.

The court below found that the Law School's race conscious

affirmative action program did not violate criteria set forth

in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, supra.

The Law School's program does not employ either quotas or

goals. Race is treated as only one of a series of competing

factors bearing upon eligibility for admission. Obviously

therefore, the program is in strict compliance with Justice

23/

Powell' opinion in Bakke.

Justice Powell upheld in Bakke, supra, affirmative

action programs which met the criteria stated in his opinion,

because they enabled a university to select "students who

will contribute the most to the 'robust exchange of ideas.'"

438 U.S. at 313. This purpose was important, he held,

because it "invoke(d) a countervailing constitutional interest,

that of the First Amendment." Id_. at 313. Ultimately,

therefore he upheld the power of universities to apply race

conscious criteria for the purpose of diversifying its

student body because a university's diversification of

its student population "is of paramount importance in the

fulfillment of its mission." Id.

23/ See Justice Powell's opinion in Bakke at 438 U.S.

311-319.

30

California's interest in promoting diversity of its

student body is, under the State Constitution, equally

compelling. It seeks also to further First Amendment

goals in the education of its young. This interest is under

state law no less important than the interest recognized

in Justice Powell's opinion in Bakke under the Fourteenth

Amendment. In view of the identity of interests, this

Court's decision in Price, supra, requires lower courts to

permit public bodies of California, such as the Law School,

to employ, under State law, race conscious admissions criteria

to the same extent as permitted under federal law.

Also in Bakke, the joint opinion by Justices Brennan,

White, Marshall, and Blackmun, held that a public university

can adopt a race conscious admissions program whenever "there

is a sound basis for concluding that minority underrepresenta

tion is substantial and chronic, and that the handicap of

past discrimination is impeding access of minorities to ...

(s)chool." Bakke, 438 U.S. 363. Under this standard, race

conscious remedies may be utilized by a State irrespective of

whether the need for the program is generated by discrimina

tion committed by the State or by society at large. _Id. at

369.

Justices Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun recognized,

under the Fourteenth Amendment, a federally protected interest

in curing chronic minority underrepresentation caused by

societal discrimination. Their protection of this interest

31

was based upon an assessment of the national experience

with respect to racial discrimination. There is no reason why

California, given its similar experience, should afford less

recognition and protection to this interest than the federal

government. California's undisputed interest in ameliorating

chronic underrepresentation of minorities, at least in the

• field of higher education, is demonstrated by its enactment

*

of Assembly Concurrent Resolution 151, supra. Thus, there is

no basis in fact or law for concluding that California's

interest under its State Constitution in allowing the use of

race conscious programs to cure chronic underrepresentation

of minorities, is less than that under the federal Constitu

tion. See Price, supra, 604 P.2d at 1382, 1383.

In conclusion, it is submutted that the allowable scope

of race conscious programs under the California State Con

stitution is at least co-extensive with that permitted under

the Fourteenth Amendment. This Court should therefore

hold that the Law School's admissions program is valid and

that it constitutes a reasonable means for implementating the

< California Legislature's policy, based on its finding that

minorities "are underrepresented in institutions of public

higher education", to increase the number of minority students

in higher education. Assembly Legislature, Assembly Permanent

Subcom. on Postsecondary Education, supra.

To uphold, under these circumstances, the validity of

a university's admissions program which merely vindicates

32

official State policy would only confirm the correctness of

this Court's previous assertion that "affirmative steps

are at times necessary to overcome the legacy of the past

degradation of minorities and to bring minorities into full

membership in American society." Price, supra, 604 P.2d

1 365.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons indicated herein the judgment of the

Court of Appeal should be vacated and the action dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENbY rG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030New York, New York 10019

Telephone: (212) 586-9397

JOHN H. ERICKSON

ALICE M. BEASLEY

HENRY S. HEWITT

ERICKSON, BEASLEY & HEWITT

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, CA. 94108

Telephone: (415) 781-3040

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

33

A

I