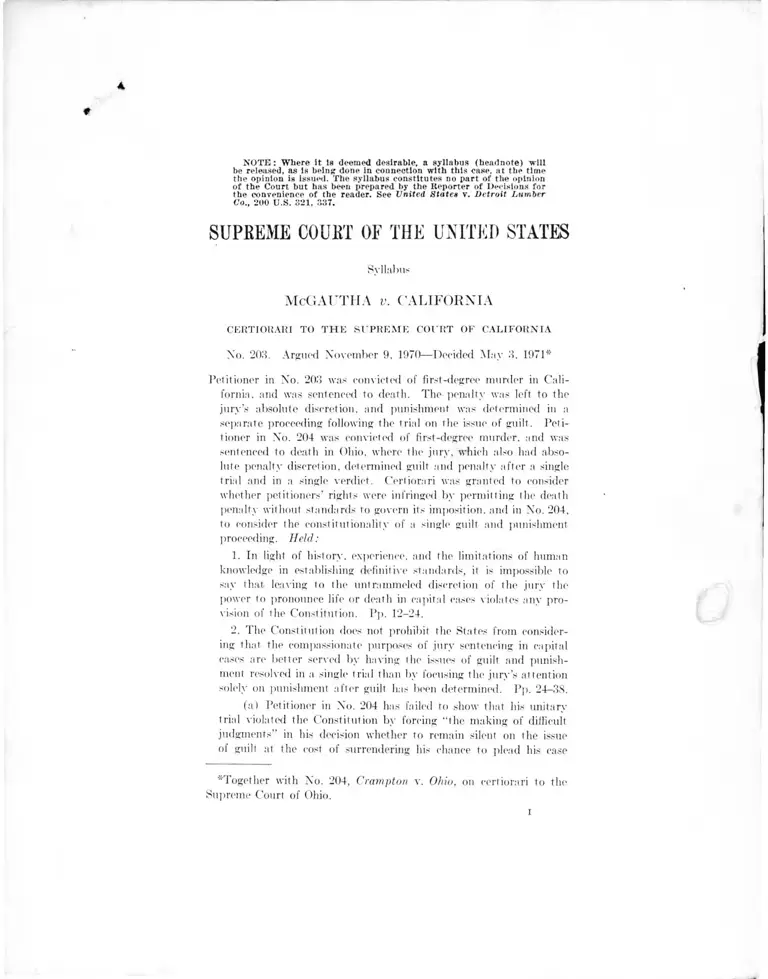

McGautha v California Opinion

Public Court Documents

November 9, 1970 - May 3, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McGautha v California Opinion, 1970. 409fe85f-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bb68fccf-4aa2-49bf-b95b-143591b51dac/mcgautha-v-california-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

NOTE: Where it is deemed desirable, a syllabus (headnote) will

be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time

the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion

of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for

the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Lumber

Co., 200 U.S. 321, 337.

SUPBEME COUKT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

No. 208. Argued November 9. 1970— Decided May 8. 1971*

Petitioner in No. 203 was convicted of first-degree murder in Cali

fornia, and was sentenced to death. The penalty was left to the

jury’s absolute discretion, and punishment was determined in a

separate proceeding following the trial on the issue of guilt. Peti

tioner in No. 204 was convicted of first-degree murder, and was

sentenced to death in Ohio, where the jury, which also had abso

lute penalty discretion, determined guilt and penalty after a single

trial and in a single verdict. Certiorari was granted to consider

whether petitioners’ rights were infringed by permitting the death

penalty without standards to govern its imposition, and in No. 204,

to consider the constitutionality of a single guilt and punishment

proceeding. Held:

1. In light of history, experience, and the limitations of human

knowledge in establishing definitive standards, it is impossible to

say that leaving to the untrammeled discretion of the jury the

power to pronounce life or death in capital cases violates any pro

vision of the Constitution. Pp. 12-24.

2. The Constitution does not prohibit the States from consider

ing that the compassionate purposes of jury sentencing in capital

cases are better served by having the issues of guilt and punish

ment resolved in a single trial than by focusing the jury’s attention

solely on punishment after guilt has been determined. Pp. 24—38.

(a) Petitioner in No. 204 has failed to show that his unitary

trial violated the Constitution by forcing "the making of difficult

judgments” in his decision whether to remain silent on the issue

of guilt at the cost of surrendering his chance to plead his case

^Together with No. 204, Crompton v. Ohio, on certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Ohio.

i

I[ McGAlJTHA v. CALIFORNIA

Syllabus

on the punishment issue. Simmons v. United States, .390 U. 8.

377. distinguished. Pp. 27-29.

(h) The policies of the privilege against self-incrimination are

not offended when a defendant in a capital case yields to the pres

sure to testify on the issue of punishment at the risk of damaging

his case on guilt. Pp. 29-34.

(c) Ohio does provide for the common-law ritual of allocution,

hut the State need not provide petitioner an opportunity to speak

to the jury free from any adverse consequences on the issue of

guilt. Pp. 34-37.

No. 203, 70 Cal. 2d 770. 452 P. 2d 050; and No. 204. IS Ohio St.

2d 1S2. 24S X. E. 2d 014. affirmed.

Harlan. J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Burger,

C. J.. and Stewart. W hite, and Black m u x , J.T., joined. Black, J.,

filed an opinion concurring in the result. D ouglas, J., filed an opin

ion dissenting in No. 204. in which Brennan and M arshall, .1,1.,

joined. Brennan , J„ filed a dissenting opinion, in which D ouglas

and M arshall. .1.1,, joined.

NOTICE : This opinion Is subject to formal revision before publication

In the preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are re*

?nested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the

Inlted States, Washington, D.C. 2<).r>43, of any typographical or other

formal errors, in order that corrections may be made before the pre

liminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 203 & 204.— October T erm, 1070

Dennis Councle McGautha,

Petitioner,

203 v.

State of California.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Cali

fornia.

James Edward Crampton,

Petitioner, On Writ of Certiorari to the

204 v. Supreme Court of Ohio.

State of Ohio.

| May 3, 10711

M r. Justice H arlan delivered the opinion of the

Court.

Petitioners McGautha and Crampton were convicted

of murder in the first degree in the courts of California

and Ohio respectively and sentenced to death pursuant to

the statutes of those States. In each case the decision

whether the defendant should live or die was left to the

absolute discretion of the jury. In McGautha’s case the

jury, in accordance with California law, determined pun

ishment in a separate proceeding following the trial on the

issue of guilt. In Crampton’s case, in accordance with

Ohio law, the jury determined guilt and punishment after

a single trial and in a single verdict. We granted certi

orari in the McGautha case limited to the question

whether petitioner’s constitutional rights were infringed

by permitting the jury to impose the death penalty with

out any governing standards. 398 U. S. 936 (1970). We

granted certiorari in the Crampton case limited to that

same question and to the further question whether the

203 <fc 204—OPINION

jury’s imposition of the death sentence in the same pro

ceeding and verdict as determined the issue of guilt was

constitutionally permissible. Ibid.1 * For the reasons

that follow, we find no constitutional infirmity in the

conviction of either petitioner, and we affirm in both

cases.

T

It will put the constitutional issues in clearer focus to

begin by setting out the course which each trial took.

A. McGautha’s Guilt Trial

McGautha and his codefendant Wilkinson were charged

with committing two armed robberies and a murder on

February 14, 1907." In accordance with California pro

cedure in capital cases, the trial was in two stages, a guilt

stage and a punishment stage.3 At the guilt trial the

2 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

1 The same two questions were included in our grant of certiorari

in Maxwell v. Bishop, 303 U. S. 907 (1968), three years ago.

After twice hearing argument in that case, see 395 U. S. 918 (1969),

we remanded the case to the District Court for consideration of

possible violations of the rule of Witherspoon v. Illinois, 301 U. S.

510 (1068). 398 U. S. 262 (1970). In taking that course we at the

same time granted certiorari in the McGautha and Crompton cases

to consider the two questions thus pretermitted in Maxwell. See id..

at 267 n. 4.

-The information also alleged that McGautha had four prior

felony convictions: felonious theft, robbery, murder without malice,

and robbery by assault. The most recent of these convictions

occurred in 1052. In a proceeding in chambers McGautha admitted

the convictions, and the jury did not learn of them at the guilt

stage of the trial.

•'‘ California Penal Code § 190.1 (West Supp. 1070) provides:

‘ 'The guilt or innocence of every person charged with an offense

for which the penalty is in the alternative death or imprisonment

for life shall first be determined, without a finding as to penalty.

If such person has been found guilty of an offense punishable by

life imprisonment or death, and has been found sane on any plea

of not guilty by reason of insanity, there shall thereupon be further

(I'.un[ qous Aq poujoj oq jou

jp:qs jjtnS jo onssi oqj jnq ‘Ajjuuod jo onssi oqj ajj oj pajauBduq

AJllf AUU U JopjU JO 'AjpiUjd JO JUSSI Jl(J 110 p.’UJ A\dll U SlljJOpjO JO

njq ill ojq joj juouiqsiund jq j osoduq joqjio put! .unf jq j ssimsip

IP’qs jjuoo oqj ‘.\jp:uod jo onssi oqj uo joipjo.i snouuuuun u qoeoj oj

•J[qi;uu si ‘Ajp.’uod jo uussi oqj JIiiia'j j ‘.unf jjqjom ; jo juius aqj pin:

‘.unf u Aq AjpuS puuoj uaoq snq juupuajop qoiq.u 11; asi:a auu up..

■Ajpjuod JO JUSS| Ol[J ouiuuojjp OJ UAMUp

oq jpjqs .unf auu 1: osuo qoiq.u ui ‘.uuf ji:q j soSjeqostp jjuoo aqj

‘u.noqs osm.'j pooif joj ‘ssjjuu .util' oiuus aqj oq |p:qs jobj jo ja u j

oqj •AJllf t! Aq pOJOJAUOJ SllAl JUlipilOJOp oqj JJ pjAlBAl SI AJllf u

ssjjuu AJllf 1: uq [p:qs jji :j jo jouj oqj ‘a j[iu2 jo i:j|d u Aq pojoi.uioo

siiAi jiiBpujjop oqj jp -jjuoj oqj oq jjrnjs jobj jo j j i j j oqj ‘.unf

1: jnoqjiAi Siujjis jjuoj aqj Aq pojoi.uioo suav juupuojop oqj j j .,

juupuojop oqj uodn oq j[uqs uosjod pins jo

oSi: aqj oj si: joojd jo itopjnq oq p ’omija aqj jo uoisstuuuoo oqj

jo ouuj oqj j 1: sjbja m jo o3u oqj jopun sba\ oijai uosjod auu uodn

‘jjAOAioq posoduu oq jou quqs Ajpmad qjuap oq p 'joipjjA jo uois

-loop jq j in poji.js .qssajdxo aq quqs poxq Ajjmiad oqj pm: ‘pojuos

-ojd oouopiAj oqj no jobj jo onssi jq j Sur.uj .unf jo jjuoo oqj jo

uoijojosip aqj 111 oq quqs q jiap jo juouiuosuduu ojq jo .vjpmad aqj

jo uoijBuiuuojop oq p -AjjBuad oqj jo uoijbSijiui jo uoijuaujSSb

in sjoBj Auu jo pin: ‘.uojsiq pm: pimojSqouq s( jui.'puojop oqj jo

•oiuijo oqj Siupiinojjns saouujsuinojio aqj jo ‘Ajpmad jo onssi aqj uo

sJjiqpoaoojd joqunj aqj ji: pojuosojd oq Auui oouopi.q.p '.upmad oqj

X,J llKlls jauj J0 j j i j j oqj pun ‘Ajpmad jo onssi oqj 110 sSttipoooojd

Ol[J UI oSpiJJJBO AJtlulG U« JOl[ pO.UOqS pUB UBUI B JOI[S

pBi[ oq aoq p[oj BqjMBijajY Aaoqqoa oqj jojjb Aqjaoqs jBqj

poyijsoj puouj piiS joiujoj syiosuijyi \\ ■BUBjouig ujy Sin

-piino.tt Xjjbjbj qioay sbav joqs y qiBoq oqj uo BUBjoiug

'SJjy qotujs aoqjo oqj ‘aoiuojsno b pouiBJjsoa Appoaoj jub

- puojop ouo opq yv -ooubjsissb spuuqsnq aoq qji.u aoq A’q

pOJBJOClO pi IB BUBJOUIg UIUlBl'lIOg A(| poiiAio ouo siqj

‘0.10JS JoqjoiiB (In p[oq uosupyiyY pm: BqjiiBpjojY mojbj

SJtioq oojqj XjqSnojj '()()[:$ jsouqu qooj pm: qooq ‘s.ijy

uo unS sxq poutBJj BqjnB*~)Oj/\r ‘paunS jopun aoiuojsno

b jdoq uosmqp yy >̂1!l|AV '•>>>pjtuu oqj jo uooujojjb oqj

ui X{jbo qooq u o j ‘sajy jo joqaBiu oqj poaojuo ‘spojsid

qjiAi pouuB ‘sjuBpuojop oqj jBqj Avoqs oj popuoj oouopiAO

VINHOdFIVO YH.L.lVO'dV'

xoixido—too -y soo

203 & 204—OPINION

chamber of his gun. Other evidence at the guilt stage

was inconclusive on the issue as to who fired the fatal

shot. The jury found both defendants guilty of two

counts of armed robbery and one count of first-degree

murder as charged.

B. McGautha’s Penalty Trial

At the penalty trial, which took place on the following

day but before the same jury, the State waived its open

ing, presented evidence of McGautha’s prior felony con

victions and sentences, see n. 2, supra, and then rested.

Y\ ilkinson testified in his own behalf, relating his un

happy childhood in Mississippi as the son of a white

father and a Negro mother, his honorable discharge from

the Army on the score of his low intelligence, his regular

attendance at church, and his good record for holding jobs

and supporting his mother and siblings up to the time he

was shot in the back in an unprovoked assault by a street

gang. Thereafter, he testified, he had difficulty obtain

ing or holding employment. About a year later he fell

in with McGautha and his companions, and when they

found themselves short of funds, one of the group sug

gested that they “knock over somebody.” This was the

first time, Wilkinson said, that he had ever had any

thoughts of committing a robbery. He admitted partici

pating in the two robberies but said he had not known

that the stores were to be held up until McGautha drew

his gun. He testified that it had been McGautha who

struck Mrs. Smetana and shot Mr. Smetana.

Wilkinson called several witnesses in his behalf. An

undercover narcotics agent testified that he had seen

the murder weapon in McGautha’s possession and had

seen McGautha demonstrating his quick draw. A min

ister with whom W ilkinson had boarded testified to

ilkinson s church attendance and good reputation. He

also stated that before trial Wilkinson had expressed his

4 McGAUTIIA v. CALIFORNIA

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 5

horror at what had liappened and requested the minister’s

prayers on his behalf. A former fellow employee testified

that Wilkinson had a good reputation and was honest

and peaceable.

McGautha also testified in his own behalf at the pen

alty hearing. He admitted that the murder weapon was

his, but testified that he and Wilkinson had traded guns,

and that it was Wilkinson who had struck Airs. Smetana

and killed her husband. McGautha testified that he

came from a broken home and that he had been wounded

during World War II. He related his employment rec

ord, medical condition, and remorse. He admitted his

criminal record, see n. 2, supra, but testified that he had

been a mere accomplice in two of those robberies and

that his prior conviction for murder had resulted from

a slaying in self-defense. McGautha also admitted to a

1964 guilty plea to a charge of carrying a concealed

weapon. He called no witnesses in his behalf.

The jury was instructed in the following language:

“ in this part of the trial the law does not forbid you

from being influenced by pity for the defendants and

you may be governed by mere sentiment and sym

pathy for the defendants in arriving at a proper

penalty in this case; however, the law does forbid

you from being governed by mere conjecture, preju

dice, public opinion or public feeling.

“ The defendants in this case have been found

guilty of the offense of murder in the first degree,

and it is now your duty to determine which of the

penalties provided by law should be imposed on

each defendant for that offense. Now in arriving

at this determination you should consider all of the

evidence received here in court presented by the

People and defendants throughout the trial before

this jury. Aou may also consider all of the evidence

of the circumstances surrounding the crime, of each

203 & 204—OPINION

defendant’s background and history, and of the

facts in aggravation or mitigation of the penalty

which have been received here in court. However,

it is not essential to your decision that you find

mitigating circumstances on the one hand or evi

dence in aggravation of the offense on the other

hand.

6 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

. . Notwithstanding facts, if any, proved in

mitigation or aggravation, in determining which

punishment shall be inflicted, you are entirely free

to act according to your own judgment, conscience,

and absolute discretion. That verdict must express

the individual opinion of each juror.

“Now, beyond prescribing the two alternative

penalties, the law itself provides no standard for the

guidance of the jury in the selection of the penalty,

but, rather, commits the whole matter of determin

ing which of the two penalties shall be fixed to the

judgment, conscience, and absolute discretion of the

jury. In the determination of that matter, if the

jury does agree, it must be unanimous as to which

of the two penalties is imposed.” App. 221-223.' 4

4 The penalty jury interrupted its deliberations to ask whether a

sentence of life imprisonment meant that there was no possibility of

parole. The trial judge responded as follows:

"A sentence of life imprisonment means that the prisoner may

be paroled at some time during his lifetime or that he may spend

the remainder of his natural life in prison. An agency known as

the Adult Authority is empowered by statute to determine if and

when a prisoner is to be paroled, and under the statute no prisoner

can be paroled unless the Adult Authority is of the opinion that the

prisoner when released will assume a proper place in society and

that his release is not contrary to the welfare of society. A prisoner

released on parole may remain on parole for the balance of his

203 & 204—OPINION

Deliberations began in the early afternoon of Au

gust 24, 1067. In response to jury requests the testimony

of Mrs. Smetana and of three other witnesses was reread.

Late in the afternoon of August 25 the jury returned

verdicts fixing Wilkinson’s punishment at life imprison

ment and McGautha’s punishment at death.

The trial judge ordered a probation report on Mc-

Gautha. Having received it. he overruled McGautha’s

mot ions for a new trial or for a modification of the penalty

verdict, and pronounced the death sentence.5 Mc-

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 7

litc and it lie violates the terms of the parole lie may be returned

to prison 1o serve the life sentence.

“ So that you will have no misunderstandings relating to a sentence

of life imprisonment, you have been informed as to the general

scheme of our parole system. You are now instructed, however,

that the matter of parole is not to be considered by you in deter

mining the punishment for either defendant, and you may not.

speculate as to if. or when, parole would or would not be granted.

It is not your function to decide now whether these men will be

suitable for parole .at some future date. So far as you are concerned,

you are to decide only whether these men shall suffer the death

penalty or whether they shall be permitted 1o remain alive. I f

upon consideration of the evidence you believe that life imprison

ment is the proper sentence, you must assume that those officials

charged with the operation of our parole system will perform their

duty in a correct and responsible manner, and that they will not

parole a defendant unless he can be safely released into society. It

would be a violation of your duty as jurors if you were to fix the

penalty at death because of a doubt that the Adult Authority will

properly carry out its responsibilities.” App. 224-225.

5 Under California law the trial judge has power to reduce ihe

penalty to life if he concludes that the jury’s verdict is not supported

by the weight of the evidence. Cal. Penal Code § 1181 (7). See

In re Anderson, 69 Cal. 2d 613, 623, 73 Cal. Rptr. 21, 28, 447 P. 2d

117, 124 (196S). The California Supreme Court, to which appeal

is automatic in capital eases. Cal. Penal Code § 1239 (b ), has no'

such power. People v. Lool:adoo, 66 Cal. 2d 307, 327, 57 Cal. Rptr..

60S, 621, 425 P. 2d 208, 221 (1967).

203 & 204—OPINION

Gautha’s conviction was unanimously affirmed by the

California Supreme Court. 70 Cal. 2d 770, 76 Cal. Rptr.

434, 452 P. 2d 650 (1069). His contention that stand

ardless jury sentencing is unconstitutional was rejected

on the authority of an earlier case, In re Anderson, 69

Cal. 2d 613, 73 Cal. Rptr. 21, 447 P. 2d 117 (1968), in

which that court had divided narrowly on the issue.

C. Crampton’s Trial

Petitioner Crampton was indicted for the murder of

his wife, Wilma Jean, purposely and with premeditated

malice. He pleaded not guilty and not guilty by reason

of insanity.6 In accordance with the Ohio practice which

he challenges, his guilt and punishment were determined

in a single unitary proceeding.

At trial the State’s case was as follows. The Cramp-

tons had been married about four months at the time of

the murder. Two months before the slaying Crampton

was allowed to leave the state mental hospital, where

he was undergoing observation and treatment for alco

holism and drug addiction, to attend the funeral of his

wife’s father. On this occasion he stole a knife from the

house of his late father-in-law and ran away. He called

the house several times and talked to his wife, greatly

upsetting her. When she pleaded with him to return to

the hospital and stated that she would have to call the

police, he threatened to kill her if she did. Wilma and

her brother nevertheless did notify the authorities, who

picked Crampton up later the same evening. There was

testimony of other threats Crampton had made on his

wife’s life, and it was revealed that about 10 days before

6 Pursuant to Ohio law, Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2945.40 (Page

1954), Crampton was committed to a state mental hospital for a

month of observation. After a hearing on the psychiatric report the

trial court determined that Crampton was competent to stand trial.

S McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 20-1— OPINION

the murder Mrs. Crampton’s fear of lier husband had

caused her to request and receive police protection.

The State’s main witness to the facts surrounding the

murder was one William Collins, a convicted felon who

had first met Crampton when they, along with Cramp-

ton’s brother Jack, were in the State Prison in Michigan.

On January 14, 1967, three days before the murder, Col

lins and Crampton met at Jack Crampton’s house in Pon

tiac, Michigan. During those three days Collins and

Crampton roamed the upper Midwest, committing a

series of petty thefts and obtaining amphetamines,

to which both were addicted, by theft and forged

prescriptions.

About nine o ’clock on the evening of January 16,

Crampton called his wife from St. Joseph, Michigan;

after the call he told Collins that he had to get back to

Toledo, where his wife was, as fast as possible. They

arrived in the early morning hours of January 17. After

Crampton had stopped by his wife’s home and sent Col

lins to the door with a purported message for her, the

two went to the home of Crampton’s mother-in-law,

which Crampton knew to be empty, to obtain some guns.

They broke in and stole a rifle, ammunition, and some

handguns, including the .45 automatic which was later

identified as the murder weapon. Crampton kept this

gun with him. He indicated to Collins that he believed

his wife was having an affair. He fired the .45 in the air,

with a remark to the effect that “a slug of that type would

do quite a bit of damage,” and said that if he found his

wife with the man he suspected he would kill them both.

That evening Crampton called his wife’s home and

learned that she was present. He quickly drove out to

the house, and told Collins, “ Leave me off right here in

front of the house and you take the car and go back to

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA (>•

203 & 204—OPINION

the parking lot and if I ’m not there by six o'clock in the

morning you’re on your own.”

About 11:20 that evening Crampton was arrested for

driving a stolen car. The murder weapon was found

between the seats of the car.

Airs. Crampton’s body was found the next morning.

She had been shot in the face at close range while she

was using the toilet. A .45 caliber shell casing was near

the body. A jacket which Crampton had stolen a few

days earlier Mas found in the living room. The coroner,

Mho examined the body at 11:30 p. m. on January 18,

testified that in his opinion death had occurred 24 hours-

earlier, plus or minus four hours.

The defense called Crampton’s mother as a witness.

She testified about Crampton’s background, including a

serious concussion received at age nine, his good grades

in junior high school, his stepfather’s jealousy of him,

his leaving home at age 14 to live with various relatives,

his enlistment in the Navy at age 17, his marriage to a

girl named Sandra, the birth of a son, a divorce, then a

remarriage to Sandra and another divorce shortly after,

and finally his marriage to Wilma. Airs. Crampton also

testified to Crampton’s drug addiction, to his brushes

with the law as a youth and as an adult, and to his

undesirable discharge from the Navy.

Crampton’s attorney also introduced into evidence a

series of hospital reports which contained further infor

mation on Crampton’s background, including his criminal

record, which Mas substantial, his court-martial convic

tion and undesirable discharge from the Navy, and

the absence of any significant employment record. They

also contained his claim that the shooting Mas accidental;

that he had been gathering up guns around the house

and had just removed the clip from an automatic M’lien

his M’ife asked to see it; that as he handed it to her

it M-ent off accidentally and killed her. All the reports

10 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—OPINION

concluded that Crampton was sane in both the legal and

the medical senses. He was diagnosed as having a socio-

pathic personality disorder, along with alcohol and drug

addiction. Crampton himself did not testify.

The jury was instructed that

“ If you find the defendant guilty of murder in

the first degree, the punishment is death, unless you

recommend mercy, in which event the punishment

is imprisonment in the penitentiary during life."

App. 70.

The jury was given no other instructions specifically

addressed to the decision whether to recommend mercy,

but was told in connection with its verdict generally:

“You must not be influenced by any consideration

of sympathy or prejudice. Tt is your duty to care

fully weigh the evidence, to decide all disputed ques

tions of fact, to apply the instructions of the court

to your findings and to render your verdict accord

ingly. In fulfilling your duty, your efforts must be

to arrive at a just verdict.

“Consider all the evidence and make your find

ing with intelligence and impartiality, and without

bias, sympathy, or prejudice, so that the State of

Ohio and the defendant will feel that their case was

fairly and impartially tried.-’ App. 71-72.

The jury deliberated for over four hours and returned a

verdict of guilty, with no recommendation for mercy.

Sentence was imposed about two weeks later. As Ohio

law requires, Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2947.05 ( Page 1954),

Crampton was informed of the verdict and asked whether

he had anything to say as to why judgment should not

be pronounced against him. He replied:

“ Please the Court, I don’t believe I received a

fair and impartial trial because the jury was preju

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 11

203 & 204—OPINION

diced by my past record and the fact I had been a

drug addict, and T just believe I didn’t receive a

fair and impartial trial. That’s all I have to say.”

This statement was found insufficient to justify not pro

nouncing sentence upon him, and the court imposed the

death sentence.7 Crampton’s appeals through the Ohio

courts were unavailing. 18 Ohio St. 2d 182, 248 X. F.

2d 614 (1969).

If

Before proceeding to a consideration of the issues be

fore us, it is important to recognize and underscore the

nature of our responsibilities in judging them. Our func

tion is not to impose on the States, ex cathedra, what

might seem to us a better system for dealing with capital

cases. Rather it is to decide whether the Federal Con

stitution proscribes the present procedures of these two

States in such cases. In assessing the validity of the con

clusions reached in this opinion, that basic factor should

be kept constantly in mind.

I ll

We consider first McGautha’s and Crampton’s com

mon claim: that the absence of standards to guide the

jury’s discretion on the punishment issue is constitution

ally intolerable. To fit their arguments within a consti

tutional frame of reference petitioners contend that to

leave the jury completely at large to impose or withhold

the death penalty as it sees fit is fundamentally lawless

and therefore violates the basic command of the Four

teenth Amendment that no State shall deprive a person

of his life without due process of law. Despite the

12 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

7 Under Ohio law, a jury’s death verdict may not be reduced as

excessive by either the trial or the appellate court. Turner v. State,

21 Ohio Law Abs. 276, 279-280 (Ct. App. 1936); State v. Klumpp,

15 Ohio Ops. 2d 461, 46S, 175 N. E. 2d 767, 775-776 (Ct. App),

appeal dismissed, 171 Ohio St. 62, 167 N. E. 2d 778 (1960).

203 & 204— OPINION

undeniable surface appeal of the proposition, we conclude

that the courts below correctly rejected it.8

A

In order to see petitioners’ claim in perspective, it is

useful to call to mind the salient features of the history

of capital punishment for homicides under the common

law in England, and subsequent statutory developments

in this country. This history reveals continual efforts,

uniformly unsuccessful, to identify before the fact those

homicides for which the slayer should die. Thus, the

laws of Alfred, echoing Exodus 21: 12-13, provided “ Let

the man who slayeth another wilfully perish by death.

Let him who slayeth another of necessity or unwillingly,

or umvilfully, as God may have sent him into his hands,

and for whom he has not lain in wait be worthy of his life

and of lawful but if he seek an asylum.” Quoted in 3 J.

Stephen, History of the Criminal Law of England 24

(1883). In the 13th century, Bracton set it down that a

8 The lower courts thus placed themselves in accord with all other

American jurisdictions which have considered the issue. See, e. g.,.

In re Ernst, 294 F. 2d 556 (CA3 1961); Florida ex rel. Thomas v.

Culver, 253 F. 2d 507 (CA5 1958); Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F. 2d

138 (CAS 196S), vacated on other grounds, 398 U. S. 262 (1970);

Sims v. Eyman, 405 F. 2d 439 (CA9 1969); Segura v. Patterson, 402

F. 2d 249 (CA10 1968) ; McCants v. State, 282 Ala. 397, 211 So. 2d

877 (1968); Baglcy v. State, 247 Ark. 113, 444 S. W. 2d 567

(1969) ; State v. Walters, 145 Conn. 60, 138 A. 2d 786 (1958),.

appeal dismissed, 358 U. S. 46 (1958); Wilson v. State, 225 So. 2d

321 (Fla. 1969); Miller v. State, 224 Ga. 627, 163 S. E. 2d 730

(196S); State v. Latham, 190 Kan. 411, 375 P. 2d 7S8 (1962):

Duisen v. State, ----- Mo. -----, 441 S. W. 2d 688 (1969); State v.

Johnson, 34 N. ,T. 212, 168 A. 2d 1, appeal dismissed, 368 U. S. 145

(1961); People v. Fitzpatrick, 61 Misc. 2d 1043, 308 N. Y. S. 2d IS

(Co. Ct. 1970); State v. Roseboro, 276 N. C. 185, 171 S. E. 2d 886

(1970) ; Hunter v. State, 222 Tenn. 672, 440 S. W. 2d 1 (1969);

State v. Kelbacli, 23 Utah 2d 231, 461 P. 2d 297 (1969); Johnson v.

Commonwealth, 208 Ya. 481, 15S S. E. 2d 725 (1968); State v..

Smith, 74 Wash. 2d 744, 446 P. 2d 571 (1968).

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 13

203 it 204—OPINION

man was responsible for all homicides except those which

happened by pure accident or inevitable necessity, al

though he did not explain the consequences of such re

sponsibility. Id., at 35. The Statute of Gloucester, 6

Edw. 1, c. 9 (1278), provided that in cases of self-defense

or misadventure the jury should neither convict nor

acquit, but should find the fact specially, so that the

King could decide whether to pardon the accused. It

appears that in time such pardons— which may not have

prevented forfeiture of goods—came to issue as of course.

3 Stephen, supra, at 36-42.

During all this time there was no clear distinction

in terminology or consequences among the various kinds

of criminal homicide. All were prima facie capital, but

all were subject to the benefit of clergy, which after 1350

came to be available to almost any man who could read.

Although originally those entitled to benefit of clergy

were simply delivered to the bishop for ecclesiastical pro

ceedings, with the possibility of degradation from orders,

incarceration, and corporal punishment for those found

guilty, during the 15th and 16th centuries the maximum

penalty for clergyable offenses became branding on the

thumb, imprisonment for not more than one year, and

forfeiture of goods. 1 Stephen, supra, at 459-464. By

the statutes of 23 Hen. 8, c. 1, 3, 4 (1531), and 1 Edw.

6, c. 12, § 10 (1547), benefit of clergy was taken away

in all cases of “murder of malice prepensed.” 1 Stephen,

supra, at 464-465; 3 Stephen, supra, at 44. During the

next century and a half, however, “malice prepense” or

“malice aforethought” came to be divorced from actual ill

will and inferred without more from the act of killing.

Correspondingly, manslaughter, which was initially re

stricted to cases of “chance medley,” came to include

homicides where the existence of adequate provocation

rebutted the inference of malice. 3 Stephen, supra,

46-73.

14 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 A: 204—OPINION

The growth of the law continued in this country, where

there was rebellion against the common-law rule im

posing a mandatory death sentence on all convicted

murderers. Thus, in 1794. Pennsylvania attempted to

reduce the rigors of the law by abolishing capital punish

ment except for “murder of the first degree,” defined to

include all “ wilful, deliberate, and premeditated” killings,

for which the death penalty remained mandatory. Pa.

Laws 1794, c. 1766. This reform was soon copied by Vir

ginia and thereafter by many other States.

This new legislative criterion for isolating crimes ap

propriately punishable by death soon proved as unsuc

cessful as the concept of “malice aforethought.” Within

a year the distinction between the degrees of murder was

practically obliterated in Pennsylvania, Sec Keedy, His

tory of the Pennsylvania Statute Creating Degrees of

Murder, 97 V. Pa, L. Rev. 769. 773-777 (1949). Other

States had similar experiences. Wochsler & Michael. A

Rationale of the Law of Homicide, 37 Colum. L. Rev. 701.

707-709 (1937). The result was characterized in this

way by Chief .Judge Cardozo, as he then was:

“ W hat we have is merely a privilege offered to the

jury to find the lesser degree when the suddenness

of the intent, the vehemence of the passion, seems

to call irresistibly for the exercise of mercy. I have

no objection to giving them this dispensing power,

but it should be given to them directly and not in

a mystifying cloud of words.” “What Medicine Can

Do For Law” (1928) in Law and Literature 70, 100

(1931).9

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 15

9 In context the emphasis is on the confusing distinction between

degrees of murder, not the desirability of jury sentencing discretion.

It may also be noted that the former New York definitions of first-

and second-degree murder were somewhat unusual. See Weehsler A

Michael, supra, 37 Colum. L. Rev., at 704 n. 13, 709 n. 26.

203 A 204—OPINION

At the same time, jurors on occasion took the law into

their own hands in cases which were “ willful, deliberate,

and premeditated" in any view of that phrase, but

which nevertheless were clearly inappropriate for the

death penalty. In such cases they simply refused to

convict of the capital offense. See Report of the Royal

Commission on Capital Punishment, 1949-1953, Cmd.

8932, HIT 27-29 (1953); Andres v. United States, 333 U. S.

740, 753 (Frankfurter, J., concurring); cf. H. Ivalven it

H. Zeisel, The American Jury 306-312 (1966).

In order to meet the problem of jury nullification,

legislatures did not try, as before, to refine further the

definition of capital homicides. Instead they adopted

the method of forthrightly granting juries the discretion

which they had been exercising in fact. See Knowlton,

Problems of Jury Discretion in Capital Cases, 101 U. Pa.

L. Rev. 1099, 1102 and n. 18 (1953); Note, The Two-

Trial System in Capital Cases, 39 N. Y. U. L. Rev. 50,

52 (1964). Tennessee was the first State to give juries

sentencing discretion in capital cases,10 Tenn. L. 1837-

1838, c. 29, but other States followed suit, as did the

Federal Government in 1897.11 Act of Jan. 15, 1897,

10 The practice of jury sentencing arose in this country during the

colonial period for cases not involving capital punishment. It has

been suggested that this was a “ reaction to harsh penalties imposed

by judges appointed and controlled by the Crown” and a result of

“ the early distrust of governmental power.” President’s Commission

on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, Task Force

Report: The Courts 26 (1967).

11 California and Ohio, the two States involved in these cases,

abolished mandatory death penalties in favor of jury discretion in

1874 and 1898. Act of Mar. 28, 1874, c. 508, Cal. Amendatory Acts

1S73-1S74, at 457; 93 Ohio Laws 223. Except for four States that

entirely abolished capital punishment in the middle of the last cen

tury, every American jurisdiction has at some time authorized jury

sentencing in capital cases. None of these statutes have provided

standards for the choice between death and life imprisonment. See

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae 128-137.

10 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—OPINION

c. 29, § 1, 29 Stat. 487. Shortly thereafter, in Winston

v. United States, 172 U. S. 303 (1899), this Court dealt

with the federal statute for the first time.'2 The Court

reversed a murder conviction in which the trial judge in

structed the jury that it should not return a recommen

dation of mercy unless it found the existence of mitigating

circumstances. The Court found this instruction to in

terfere with the scheme of the Act to commit the whole

question of capital punishment “to the judgment and the

consciences of the jury.” Id., at 313.

How far considerations of age, sex, ignorance, ill

ness or intoxication, of human passion or weak

ness, of sympathy or clemency, or the irrevocable

ness of an executed sentence of death, or an appre

hension that explanatory facts may exist which

have not been brought to light, or any other con

sideration whatever, should be allowed weight in

deciding the question whether the accused should

or should not be capitally punished, is committed

by the act of Congress to the sound discretion of

the jury, and of the jury alone.” Ibid.

This Court subsequently had occasion to pass on the

correctness of instructions to the jury with respect to

recommendations of mercy in Andres v. United States,

333 U. S. 740 (1948). The Court approved, as consistent

with the governing statute, an instruction that

“ This power [to recommend mercy] is conferred

solely upon you and in this connection the Court

cannot extend or prescribe to you any definite

rule defining the exercise of this power, but commits 12

12 Sec also Calton v. Utah, 130 U. S. S3 (1889), in which the-

Court reversed a conviction under the statutes of Utah Territory

in which the jury had not been informed of its right under the

territorial code to recommend a sentence of imprisonment for life

at hard labor instead of death.

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 17

201? A 204—OPINION

the entire matter of its exercise to your judgment.”

Id., at 743 n. 4.

The case was reversed, however, on the ground that

other instructions on the power to recommend mercy

might have been interpreted by the jury as requiring

them to return an unqualified verdict of guilty unless they

unanimously agreed that mercy should be extended. The

Court determined that the proper construction was to

require a unanimous decision to withhold mercy as well,

on the ground among others that the latter construction

was “more consonant with the general humanitarian pur

pose of the statute.” Id., at 740. The only other sig

nificant discussion of standardless jury sentencing in

capital cases in our decisions is found in Witherspoon v.

Illinois, 301 U. S. 510 (1068). In reaching its conclusion

that persons with conscientious scruples against the death

penalty could not be automatically excluded from sen

tencing juries in capital cases, the Court relied heavily

on the fact that such juries “do little' more—and must

do nothing less—than express the conscience of the com

munity on the ultimate question of life or death.” Id.,

at 510 (footnote omitted). The Court noted that “one

of the most important functions any jury can perform in

making such a selection is to maintain a link between

contemporary community values and the penal system—

a link without which the determination of punishment

could hardly reflect ‘the evolving standards of decency

that mark the progress of a maturing society.’ ” Id., at

519 n. 15. The inner quotation is from the opinion of

Mr. Chief Justice Warren for four members of the Court

in Trop v. Dulles, 356 l '. S. 86, 101 ( 195S).

In recent years academic and professional sources have

suggested that jury sentencing discretion should be

controlled by standards of some sort. The American

Law Institute first published such a recommendation in

18 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 iV 204—OPINION

1959.11 Several States have enacted new criminal codes

in the intervening 12 years, some adopting features of

the Model Penal Code.13 14 Other States have modified

their laws with respect to murder and the death penalty

in other ways.11 None of those States have followed the

Model Penal Code and adopted statutory criteria for

imposition of the death penalty. Tn recent years, chal

lenges to standardless jury sentencing have been pre

sented to many state and federal appellate courts. No

13 Model Penal Code § 201.fi (Tent. Draft No. 9, 1959). The

criteria were revised and approved by the Institute in 1962 and

now appear in §210.6 of the Proposed Official Draft of the Model

Penal Code. As revised they appear in the Appendix to this

opinion. More recently the National Commission on Reform of

Federal Criminal Laws published a Study Draft of a New Federal

Criminal Code (1970). Section 3605 contained standards virtually

identical to those o f the Model Penal Code. The statement of the

Chairman of the Commission, submitting the Study Draft for public

comment, described it as “ something more than a staff report and

something less than a commitment by the Commission or any of its

members to every aspect of the Draft.” Study Draft, tit xx. The

primary differences between the procedural provisions for capital

sentencing in the Model Penal Code and those in the Study Draft are

that the Code provides that the court and jury “ shall” take the cri

teria into account, while the Study Draft provided that they “may”

do so: and the Model Penal Code forbids imposition of the death

penalty where no aggravating circumstances are found, while the

Study Draft showed this only as an alternative provision. The latter

feature is affected by the fact that only a very few murders were

to be made capital. See id.. at 307. Tn its Final Report (1971). the

Commission recommended abolition of the death penalty for federal

crimes. An alternate version, said to represent a "substantial body

of opinion in the Commission,” id., comment to provisional §3601,

provided for retention of capital punishment for murder and treason

with procedural provisions which did not significantly differ from

those in the Study Draft.

14 See, c. (]., N. Y. Penal Law § 65.00 (1967) (criteria for judges

in deciding on probation).

' :'F . g., N. M. Stat. Ann. § 40A-29-2.1 to § 40A-29-2.2 (Supp.

1969). reducing the class of capital crimes.

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 19

203 it 204—OPINION

court has held the challenge good. See n. 8. supra. As

petitioners recognize, it requires a strong showing to upset

this settled practice of the Nation on constitutional

grounds. See Walz v. Tax Commission, 397 U. S. 664,

678 (1970); Jackman v. Rosenbaum Co., 260 U. S. 22, 31

(1922); cf. Palko v. Connecticut. 302 I ’ . S. 319, 325

(1937).

B

Petitioners seek to avoid the impact of this history by

the observation that jury sentencing discretion in capital

cases was introduced as a mechanism for dispensing

mercy—a means for dealing with the rare case in which

the death penalty was thought to be unjustified. Now,

they assert, the death penalty is imposed on far fewer than

half the defendants found guilty of capital crimes. The

state and federal legislatures which provide for jury dis

cretion in capital sentencing have, it is said, implicitly

determined that some—indeed, the greater portion—of

those guilty of capital crimes should be permitted to live.

But having made that determination, petitioners argue,

they have stopped short—the legislatures have not only

failed to provide a rational basis for distinguishing the

one group from the other, cf. Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316

U. S. 535 (1942), but they have failed even to suggest any

basis at all. Whatever the merits of providing such a

mechanism to take account of the unforeseeable case

calling for mercy, as was the original purpose, petitioners

contend the mechanism is constitutionally intolerable as

a means of selecting the extraordinary cases calling for

the death penalty, which is its present-day function.

In our view, such force as this argument has derives

largely from its generality. Those who have come to

grips with the hard task of actually attempting to draft

means of channeling capital sentencing discretion have

confirmed the lesson taught by the history recounted

above. To identify before the fact those characteristics

20 McGAIJTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—OPINION

of criminal homicides and their perpetrators which call

for the death penalty, and to express these characteristics

in language which can be fairly understood and applied

by the sentencing authority, appear to be tasks which

are beyond present human ability.

thus the British Home Office, which before the recent

abolition of capital punishment in that country had the

responsibility for selecting the cases from England and

Wales which should receive the benefit of the Royal

Prerogative of Mercy, observed:

“The difficulty of defining by any statutory pro

vision the types of murder which ought or ought

not to be punished by death may be illustrated by

reference to the many diverse considerations to which

the Home Secretary has regard in deciding whether

to recommend clemency. No simple formula can take

account of the innumerable degrees of culpability,

and no formula which fails to do so can claim to

be just or satisfy public opinion.” 1-2 Royal Com

mission on Capital Punishment, Minutes of Evi

dence 13 (1949).

The Royal Commission accepted this view, and although

it recommended a change in British practice to provide

for discretionary power in the jury to find “ extenuating

circumstances,” that term was to be left undefined;

“ [t]he decision of the jury would be within their unfet

tered discretion and in no sense governed by the prin

ciples of law.” Report of the Royal Commission on

Capital Punishment, 1949-1953, Cmd. 8932, IT 553 (b).

The Commission went on to say, in substantial con

firmation of the views of the Home Office:

“No formula is possible that would provide a

reasonable criterion for the infinite variety of cir

cumstances that may affect the gravity of the crime

of murder. Discretionary judgment on the facts of

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 21

203 & 204—OPINION

each case is the only way in which they can be

equitably distinguished. This conclusion is borne

out bv American experience: there the experiment

of degrees of murder, introduced long ago. has had

to be supplemented by giving to the courts a dis

cretion that in effect supersedes it." Id., fl 595.

The draftsmen of the Model Penal Code expressly

agreed with the conclusion of the Royal Commission that

“ the factors which determine whether the sentence of

death is the appropriate penalty in particular cases are

too complex to be compressed within the limits of a

simple formula . . . .” Report U 498, quoted in Model

Penal Code, 8 201.6, ( 'omment 3, at 71 (Tent. Draft No. 9,

1959). The draftsmen did think, however, “ that it is

within the realm of possibility to point to the main cir

cumstances of aggravation and of mitigation that should

be weighed and weighed against each other when they are

presented in a concrete case." Ibid. The circumstances

the draftsmen selected, set out in the Appendix to this

opinion, were not intended to be exclusive. The Code

provided simply that the sentencing authority should

“take into account the aggravating and mitigating cir

cumstances enumerated . . . and any other facts that

it deems relevant,” and that the court should so in

struct when the issue was submitted to the jury. Id.,

§ 210.6 (2) (Proposed Official Draft. 1962).10 The Final

lu The Model Penal Code provided that the jury should not fix

punishment at death unless it found at least one of the aggravating

circumstances and no sufficiently substantial mitigating circum

stances. Model Penal Code §210.6(2) (Proposed Official Draft

1962). As the reporter's comment recognized, there is no funda

mental distinction between this procedure and a redefinition of the

class of potentially capital murders. Model Penal Code §201.6,

Comment 3, at 71-72 (Tent. Draft No. 9, 1959). As we understand

these petitioners’ contentions, they seek standards for guiding the

sentencing authority’s discretion, not a greater strictness in the

definition of the class of cases in which the discretion exists. I f

22 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—OPINION

Report of the National Commission on Reform of

Federal Criminal Laws (1671 ) recommended entire abo

lition of the death penalty in federal cases. In a provi

sional chapter, prepared for the contingency that Con

gress might decide to retain the death penalty, the

Report contains a set of criteria virtually identical with

the aggravating and mitigating circumstances listed by

the Model Penal Code. With respect to the use to be

made of the criteria, the Report provides that: “ [i]n

deciding whether a sentence of death should be imposed,

the court and the jury, if any, may consider the miti

gating and aggravating circumstances set forth in the

subsections below.” Id., provisional §3604(1) (empha

sis added).

It is apparent that such criteria do not purport to

provide more than the most minimal control over the

sentencing authority’s exercise of discretion. They do

not purport to give an exhaustive list of the relevant

considerations or the way in which they may be affected

by the presence or absence of other circumstances. They

do not even undertake to exclude constitutionally im

permissible considerations.* 17 And, of course, they pro

vide no protection against the jury determined to decide

on whimsy or caprice. In short, they do no more than

suggest some subjects for the jury to consider during

its deliberations, and they bear witness to the intractable

nature of the problem of “ standards” which the history

of capital punishment has from the beginning reflected.

Thus they indeed caution against this Court’s under

we are mistaken in this, and petitioners contend that Ohio’s and

California’s definitions of first-degree murder are too broad, we

consider their position constitutionally untenable.

17 The issue whether a defendant is entitled to an instruction that

certain factors such as race are not to be taken into consideration

is not before us, as the juries were told not to base their decisions

on “ prejudice,” and no more specific instructions were requested.

Cf. Griffin v. California, 3S0 U. S. 009, 614-615 and n. 6 (1965).

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 23

203 & 204—OPINION

taking to establish such standards itself, or to pronounce

at large that standards in this realm are constitutionally

required.

In light of history, experience, and the present limita

tions of human knowledge, we find it quite impossible

to say that committing to the untramelled discretion of

the jury the power to pronounce life or death in capital

cases is offensive to anything in the Constitution.18 The

States are entitled to assume that jurors confronted with

the truly awesome responsibility of decreeing death

for a fellow human will act with due regard for the con

sequences of their decision and will consider a variety

of factors, many of which will have been suggested by

the evidence or by the arguments of defense counsel.

For a court to attempt to catalog the appropriate factors

in this elusive area could inhibit rather than expand the

scope of consideration, for no list of circumstances would

ever be really complete. The infinite variety of cases

and facets to each case would make general standards

either meaningless “boiler-plate" or a statement of the

obvious that no jury would need.

IV

As we noted at the outset of this opinion, McGautha’s

trial was in two stages, with the jury considering the

18 Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 3S2 U. S. 399 (19G6), does not point

to a contrary result. In Giaccio the Court held invalid on its face

a Pennsylvania statute which authorized criminal juries to assess

costs against defendants whose conduct, although not amounting to

the crime with which they were charged, was nevertheless found

to be “ reprehensible.” The Court concluded that the statute was

no more sound than one which simply made it a crime to engage

in “ reprehensible conduct” and consequently that it was unconstitu

tionally vague. The Court there stated:

“ [i]n so holding we intend to cast no doubt whatever on the

constitutionality of the settled practice of many States to leave to

juries finding defendants guilty of a crime the power to fix punish

ment within legally prescribed limits.” Id., at 405 n. 8.

24 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

20.'! & 204—OPINION

issue of guilt before the presentation of evidence and

argument on the issue of punishment. Such a proce

dure is required by the laws of California and of five

other States.1" Petitioner Crampton, whose guilt and

punishment were determined at a single trial, contends

that a procedure like California’s is compelled by the

Constitution as well.

This Court has twice had occasion to rule on separate

penalty proceedings in the context of a capital case. In

United States v. Jackson, 390 U. S. 570 (1068), we held

unconstitutional the penalty provisions of the Federal

Kidnaping Act, which we construed to mean that a de

fendant demanding a jury trial risked the death penalty

while one pleading guilty or agreeing to a bench trial

faced a maximum punishment of life imprisonment. The

Government had contended that in order to mitigate

this discrimination we should adopt an alternative con

struction, authorizing the trial judge accepting a guilty

plea or jury waiver to convene a special penalty jury

empowered to recommend the death sentence. Id., at

572. Our rejection of this contention was not based

solely on the fact that it appeared to run counter to the

language and legislative history of the Act. “ [Ejven on

the assumption that the failure of Congress to [provide

for the convening of a penalty jury] was wholly inad

vertent, it would hardly be the province of the courts to

fashion a remedy. Any attempt to do so would be fraught

with the gravest difficulties . . . .” Id., at 578-579.

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 25-

10 Cal. Penal Code § 190.1 (West Supp. 1970); Conn. Gen. Stat-

Rev. § 53a-46 (Supp. 1967); Act of Mar. 27, 1970, No. 1.33.'!, Ga.

Laws 1970, p. 949; N. Y. Penal Law §§ 125,30, 125.35 (McKinney

1967); Pa. Stat. Ann. Tit. IS, §4701 (1963); Tex. Code Crim. Proc.

Art. 3707 (2) (b) (Supp. 1970). See also ALI, Model Penal Code

§210.6(2) (Proposed Official Draft 1962); National Commission

on Reform of Federal Criminal Laws, Final Report, provisional

§ 3602 (1971); Report of the Royal Commission on Capital Punish

ment, 1949-1953, Cmd. 8932, Iff 551-595 (1953).

203 * 204—OPINION

Wo therefore declined “ to create from whole cloth a com

plex and completely novel procedure and to thrust it

upon unwilling defendants for the sole purpose of rescu

ing a statute from a charge of unconstitutionality.” Id.,

at 580. Jackson, however, did not consider the possibility

that such a procedure might be constitutionally required

in capital cases.

Substantially this result had been sought by the peti

tioner in Spencer v. Texas, 3S5 U. S. 554 (1967). Like

Crampton, Spencer had been tried in a unitary proceed

ing before a jury which fixed punishment at death. Also

like Crampton, Spencer contended that the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment required a bifur

cated trial so that evidence relevant solely to the issue

of punishment would not prejudice his case on guilt. We

rejected this contention, in the following language:

“To say that the two-stage jury trial in the English-

Connecticut style is probably the fairest, as some

commentators and courts have suggested, and with

which we might well agree were the matter before

us in a legislative or rule-making context, is a far

cry from a constitutional determination that this

method of handling the problem is compelled by tire

Fourteenth Amendment. Two-part jury trials are

rare in our jurisprudence; they have never been

compelled by this Court as a matter of constitutional

law, or even as a matter of federal procedure. With

recidivism the major problem that it is, substantial

changes in trial procedure in countless local courts

around the country would be required were this

Court to sustain the contentions made by these pe

titioners. This we are unwilling to do. To take

such a step would be quite beyond the pale of this

Court’s proper function in our federal system.” Id.„

at 567-568 (footnotes omitted).

20 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

Spencer considered the bifurcation issue in connection

with the State’s introduction of evidence of prior crimes;

we now consider the issue in connection with a de

fendant's choice whether to testify in his own behalf.

But even though this case cannot be said to be controlled

by Spencer, our opinion there provides a significant guide

to decision here.

A

Crampton’s argument for bifurcation runs as follows.

Under Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U. S. 1 (1964), and Griffin

v. California, 380 U. S. 609 (1965), he enjoyed a con

stitutional right not to be compelled to be a witness

against himself. Yet under the Ohio single-trial pro

cedure, he could remain silent on the issue of guilt only

at the cost of surrendering any chance to plead his case

on the issue of punishment. He contends that under

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

as elaborated in, e. g., Townsend v. Burke, 334 U. S.

736 (1948); Specht v. Patterson, 386 U. S. 605 (1067);

and Mempa v. Rhay, 389 I”. S. 12S (1967), he had a

right to be heard on the issue of punishment and a

right not to have his sentence fixed without the benefit

of all the relevant evidence. Therefore, he argues, the

Ohio procedure possesses the flaw we condemned in Sim

mons v. United States, 390 U. S. 377, 394 (1968); it

creates an intolerable tension between constitutional

rights. Since this tension can be largely avoided by a

bifurcated trial, petitioner contends that there is no le

gitimate state interest in putting him to the election,,

and that the single-verdict trial should be held invalid

in capital cases.

Simmons, however, dealt with a very different situation

from the one which confronted petitioner Crampton, and

not everything said in that opinion can be carried over

27

203 & 204—OPINION

to tliis case without circumspection. In Simmons we held

it unconstitutional for the Federal Government to use at

trial the defendant’s testimony given on an unsuccessful

motion to suppress evidence allegedly seized in violation

of the Fourth Amendment. We concluded that to per

mit such use created an unacceptable risk of deterring the

prosecution of marginal Fourth Amendment claims, thus

weakening the efficacy of the exclusionary rule as a sanc

tion for unlawful police behavior. This was surely an

analytically sufficient basis for decision. However, we

went on to observe that the penalty thus imposed on the

good-faith assertion of Fourth Amendment rights was

“ of a kind to which this Court has always been peculiarly

sensitive,” 390 U. S., at 393, for it involved the incrimina

tion of the defendant out of his own mouth.

A e found it not a little difficult to support this invoca

tion of the Fifth Amendment privilege. We recognized

that “ [a]s an abstract matter” the testimony might be

voluntary, and that testimony to secure a benefit from

the Government is not ipso facto “compelled” within the

meaning of the Self-Incrimination Clause. The distin

guishing feature in Simmons’ case, we said, was that “ the

‘benefit’ to be gained is that afforded by another pro

vision of the Bill of Bights.” Id., at 393-394. Thus the

only real basis for holding that Fifth Amendment policies

were involved was the colorable Fourth Amendment

claim with which we had begun.

The insubstantiality of the purely Fifth Amendment

interests involved in Simmons was illustrated last Term

by the trilogy of cases involving guilty pleas. Brady v.

United States, 397 U. S. 742 (1970); McMann v. Richard

son, 397 U. S. 759 (1970); Parker v. North Carolina, 397

U. S. 790 (1970). While in Simmons we relieved the

defendant of his “waiver” of Fifth Amendment rights

made in order to obtain a benefit to which he was ulti

mately found not constitutionally entitled, in the trilogy

28 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204— OPINION

we held the defendants bound by “waivers” of rights un

der the Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments made

in order to avoid burdens which, it was ultimately deter

mined, could not constitutionally have been imposed. In

terms solely of Fifth Amendment policies, it is apparent

that Simmons had a far weaker claim to be relieved of his

ill-advised “waiver” than did the defendants in the guilty-

plea trilogy. While we have no occasion to question

the soundness of the result in Simmons and do not do

so. to the extent that its rationale was based on a “ ten

sion” between constitutional rights and the policies be

hind them, the validity of that reasoning must now be

regarded as open to question, and it certainly cannot bo

given the broad thrust which is attributed to it by

Crampton in the present case.

The criminal process, like the rest of the legal system,

is replete with situations requiring “ the making of dif

ficult judgments” as to which course to follow. McMann

v. Richardson, 397 U. S. 759, 769 (1970). Although a

defendant may have a right, even of constitutional di

mensions, to follow whichever course he chooses, the

Constitution does not by that token always forbid re

quiring him to choose. The threshold question is

whether compelling the election impairs to an appreciable

extent any of the policies behind the rights involved.

Analysis of this case in such terms leads to the conclusion

that petitioner has failed to make out his claim of a con

stitutional violation in requiring him to undergo a unitary

trial.

B

\\ e turn first to the privilege against compelled self

incrimination. The contention is that where guilt and

punishment are to be determined by a jury at a single

trial the desire to address the jury on punishment unduly

encourages waiver of the defendant’s privilege to remain

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 29'

203 ^ 204—OPINION

silent on the issue of guilt, or, to put the matter another

way, that the single-verdict procedure unlawfully compels

the defendant to become a witness against himself on

the issue of guilt by the threat of sentencing him to death

without having heard from him. It is not contended,

nor could it be successfully, that the mere force of evi

dence is compulsion of the sort forbidden by the privilege.

See Williams v. Florida, 390 U. S. 78, 83-85 (1970).

It does no violence to the privilege that a person’s

choice to testify in his own behalf may open the door to

otherwise inadmissible evidence which is damaging to his

case. See Spencer v. Texas, 385 U. S. 554, 561 and n. 7

(1967); cf. Michelson v. United States, 335 U. S. 469

(1948). The narrow question left open is whether it

is consistent with the privilege for the State to provide

no means whereby a defendant wishing to present evi

dence or testimony on the issue of punishment may limit

the force of his evidence (and the State’s rebuttal) to

that issue. We see nothing in the history, policies, or

precedents relating to the privilege which requires such

means to be available.

So far as the history of the privilege is concerned, it

suffices to say that it sheds no light whatever on the

subject, unless indeed that which is adverse, resulting

from the contrast between the dilemma of which peti

tioner complains and the historical excesses which gave

rise to the privilege. See generally 8 J. Wigmore, Evi

dence §2250 (McNaugton rev. ed. 1961); L. Levy, Ori

gins of the Fifth Amendment (1968). Inasmuch as at

the time of framing of the Fifth Amendment and for

many years thereafter the accused in criminal cases was

not allowed to testify in his own behalf, nothing ap

proaching Crampton’s dilemma could arise.

The policies of the privilege likewise are remote sup

port for the proposition that defendants should be per

mitted to limit the effects of their evidence to the issue

30 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—OPINION

of punishment. rl'lio policies behind the privilege are

varied, and not all are implicated in any given application

of the privilege. See Murphy v. Waterfront Commission,

378 U. S. 52. 55 (1964); see generally 8 J. Wigmore,

supra, § 2251, and sources cited therein, n. 2. It can

safely be said, however, that to the extent these policies

provide any guide to decision, see McKay, Book Review,

35 X. Y. lb L. Rev. 1097, 1100-1101 (1960), the only

one affected to any appreciable degree is that of “cruelty.”

It is undeniably hard to require a defendant on trial

for his life and desirous of testifying on the issue of

punishment to make nice calculations of the effect of his

testimony on the jury’s determination of guilt. The

issue of cruelty thus arising, however, is less closely akin

to “ the cruel trilemma of self-accusation, perjury or

contempt,” Murphy v. Waterfront Commission, 378 U. S.,

at 55, than to the fundamental requirements of fairness

and decency embodied in the Due Process Clauses.

Whichever label is preferred, appraising such considera

tions is inevitably a matter of judgment as to which

individuals may differ; however, a guide to decision is

furnished by the clear validity of analogous choices with

which criminal defendants and their attorneys are quite

routinely faced.

It has long been held that a defendant who takes the

stand in his own behalf cannot then claim the privilege

against cross-examination on matters reasonably related

to the subject matter of his direct examination. See,

e. cj.. Brown v. Walker, 161 U. S. 591, 597-598 (1896);

Fitzpatrick v. United States, 178 U. S. 304, 314—31<>

(1900); Brown v. United States, 356 Y. S. 148 (1958).

It is not thought overly harsh in such situations to re

quire that the determination whether to waive the privi

lege take into account the matters which may be brought

out on cross-examination. It is also generally recognized

that a defendant who takes the stand in his own behalf

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 31

203 & 204—OPINION

may be impeached by proof of prior convictions or the

like. See Spencer v. Texas, 385 U. S. 554, 5G1 (1067) ;

cf. Michelson v. United States, 335 U. S. 409 (1948);

but cf. Luck v. United States, 348 F. 2d 763 (CADC

1065); Palumbo v. United States, 401 F. 2d 270 (CA2

1068). Again, it is not thought inconsistent with the

enlightened administration of criminal justice to require

the defendant to weigh such pros and cons in deciding

whether to testify.

Further, a defendant whose motion for acquittal at

the close of the Government’s case is denied must decide

whether to stand on his motion or put on a defense,

with the risk that in so doing he will bolster the Gov

ernment case enough for it to support a verdict of guilty.

E. g., United States v. Calderon, 348 U. S. 160, 164 and

n. 1 (1054); 2 C. Wright, Federal Practice and Procedure

S 463 (1969); cf. ABA Project on Minimum Standards

for Criminal Justice: Trial by Jury 107-10S (Tent.

Draft, 1968). But see Comment, The Motion for Ac

quittal: A Neglected Safeguard, 70 Yale L. J. 1151

(1061); cf. Cephas v. United States, 324 F. 2d 803 (CADC'

1963). Finally, only last Term in Williams v. Florida,

309 D. S. 7S (1070) , we had occasion to consider a Florida

“notice-of-alibi” rule which put the petitioner in that

case to the choice of either abandoning his alibi defense

or giving the State both an opportunity to prepare a

rebuttal and leads from which to start. We rejected the

contention that the rule unconstitutionally compelled

the defendant to incriminate himself. The pressures

which might lead the defendant to furnish this arguably

“ testimonial” and “ incriminating” information arose

simply from

“the force of historical fact beyond both his and the

State’s control and the strength of the State’s case

built on these facts. Response to that kind of pres

sure by offering evidence or testimony is not com-

32 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

203 & 204—OPINION

polled self-incrimination transgressing the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments.” Id., at 85.

e are thus constrained to reject the suggestion that a

desire to speak to one’s sentencer unlawfully compels a

defendant in a single-verdict capital case to incriminate

himself, unless there is something which serves to dis

tinguish sentencing—or at least capital sentencing—from

the situations given above. Such a distinguishing factor

can only be the peculiar poignancy of the position of a

man whose life is at stake, coupled with the imponder

ables of the decision which the jury is called upon to

make. We do not think that the fact that a defendant’s

sentence, rather than his guilt, is at issue creates a con

stitutionally sufficient difference from the sorts of situa

tions we have described. While we recognize the truth

of Mr. Justice Frankfurter’s insight in Green v. United

States, 365 U. S. 301, 304 (1961) (plurality opinion),

as to the peculiar immediacy of a personal plea by the

defendant for leniency in sentencing, it is also true that

the testimony of an accused denying the case against him

has considerably more force than counsel’s argument that

the prosecution’s case has not been proven. The relevant

differences between sentencing and determination of guilt

or innocence are not so great as to call for a differ

ence in constitutional result. Nor does the fact that

capital, as opposed to any other, sentencing is in issue

seem to us to distinguish this case. See Williams v. New

York, 337 U. S. 241, 251-252 (1949). Even in non

capital sentencing the sciences of penology, sociology, and

psychology have not advanced to the point that sentenc

ing is v holly a matter of scientific calculation from objec

tively verifiable facts.

W e conclude that the policies of the privilege against

compelled self-incrimination are not offended when a

defendant in a capital case yields to the pressure to

testify on the issue of punishment at the risk of dam

McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA 33

203 & 204—OPINION

aging his case on guilt. We therefore turn to the con

verse situation, in which a defendant remains silent on

the issue of guilt and thereby loses any opportunity to

address the jury personally on punishment.

C

It is important to identify with particularity the inter

ests which are involved. Petitioner speaks broadly of a

right of allocution. This right, of immemorial origin,

arose in a context very different from that which con

fronted petitioner Crampton.20 See generally Barrett,

Allocution (pts. 1-2), 9 Mo. L. Hev. 115, 232 (1944). It

has been preserved in its original form in Ohio and in

many other States.21 What petitioner seeks, to be sure

for purposes not wholly unrelated to those served by the

right of allocution in former times, see Green v. United

Slates, 365 U. S. 301, 304 (1961) (opinion of Frankfurter,

J.), is nevertheless a very different procedure occurring in

a radically different framework of criminal justice.

Leaving aside the term “allocution,” it also appears

that petitioner is not claiming the right simply to be

heard on the issue of punishment. This Court has not

directly determined whether or to what extent the con

cept of due process of law requires that a criminal de

fendant wishing to present evidence or argument pre-

34 McGAUTHA v. CALIFORNIA

20 For instance, the accused was not permitted to have the assist

ance of counsel, was not permitted to testify in his own behalf, was

not entitled to put on evidence in his behalf, and had almost no

possibility of review of his conviction. See, e. g.. G. Williams, The

Proof of Guilt 4-12 (3d ed., 1963); 1 .T. Stephen, A History of the-

Criminal Law of England 308-311. 350 (1883).

-'O h io Rev. Code Ann. §2947.05 (Page 1954) provides:

‘ ‘Before sentence is pronounced, the defendant must be informed

by the court of the verdict of the jury, or the finding of the court,

and asked whether he has anything to say as to why judgment should

not be pronounced against him.”

-qjSuo[ ji; suio[qojd pojtqo.1 jo siqj qjiAi piap oj uoisuooo puq