Miller v. Johnson Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 21, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miller v. Johnson Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1995. f4010ab2-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bb694764-1fcd-43e1-a831-b26f40b78124/miller-v-johnson-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

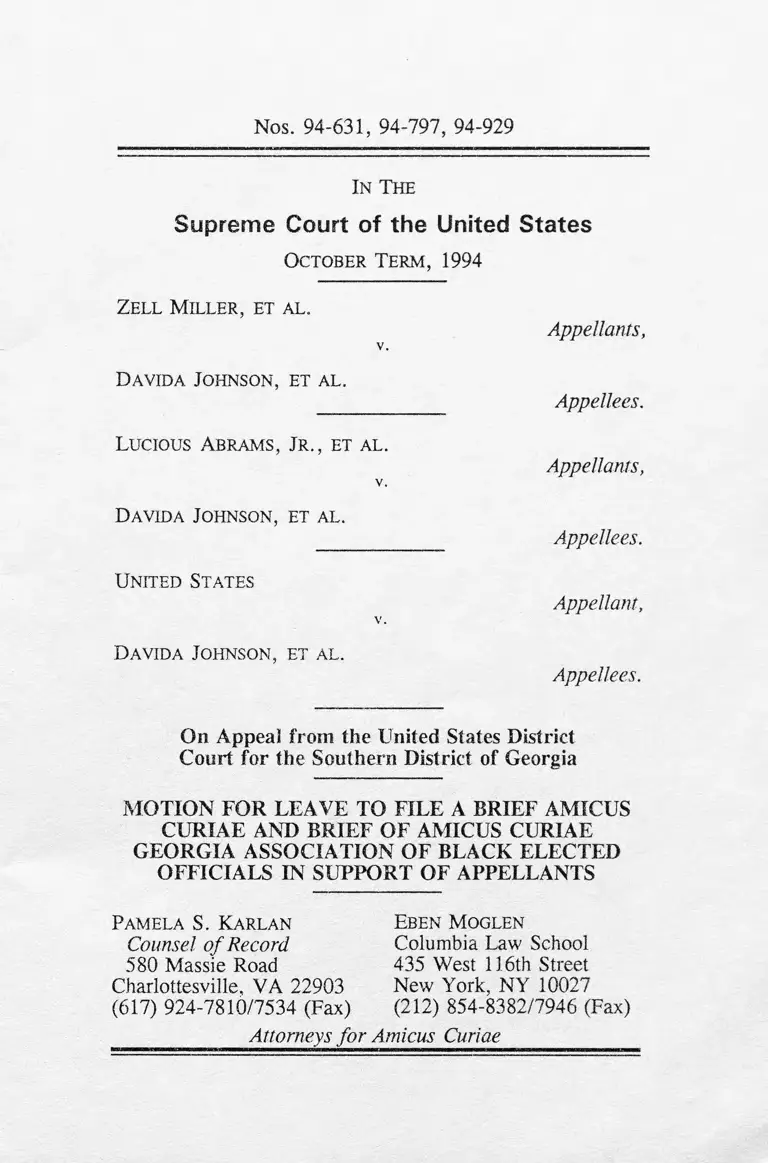

Nos. 94-631, 94-797, 94-929

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1994

Zell M iller, et al.

Appellants,

Davida Johnson, et al.

Appellees.

Lucious Abrams, Jr ., et al .

Appellants,

V.

Davida Johnson, et al.

___________ Appellees.

United States

Appellant,

V.

Davida Johnson, et al .

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Georgia

M OTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE AND BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

GEORGIA ASSOCIATION OF BLACK ELECTED

OFFICIALS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

Pamela S. Karlan

Counsel o f Record

580 Massie Road

Charlottesville, VA 22903

(617) 924-7810/7534 (Fax)

Eben Moglen

Columbia Law School

435 West 116th Street

New York, NY 10027

(212) 854-8382/7946 (Fax)

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Nos. 94-631, 94-797, 94-929

IN The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1994

Zell Miller, et al.

V .

Appellants,

Davida Johnson, et al.

Appellees.

Lucious Abrams, Jr. et al.

V.

Appellants,

Davida Johnson, et al.

Appellees.

United States

V.

Appellant,

Davida Johnson, et al.

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Georgia

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE BY THE

GEORGIA ASSOCIATION OF BLACK ELECTED

OFFICIALS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

The Georgia Association of Black Elected Officials

("GABEO") hereby moves for leave to file a brief amicus

curiae in the above-captioned cases.

GABEO is an organization of African Americans elected

to public office in Georgia at the congressional, state, and

local levels. GABEO is approximately 25 years old and has

2

more than 700 members. Its basic purposes are to promote

excellence in public officials and inclusiveness in

government. Throughout its history GABEO has supported

the adoption of non-dilutive methods of election that ensure

the full participation of all persons in the political and

electoral processes.

GABEO has obtained the consent of counsel for the

appellants in all three cases. Letters reflecting that consent

have been filed with the Clerk of the Court. Counsel for

appellees have refused to give their consent; however, they

have informed counsel for GABEO that they will not oppose

GABEO’s motion for leave to file its brief.

GABEO’s members and the constituents they

represent may be directly affected by the decision of the

Court in these cases. Its brief presents several important

issues that have not been fully addressed by the parties.

First, GABEO’s brief explains why the broad reading of this

Court’s decision in Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2618 (1993),

offered by the court below runs afoul of the equal protection

component of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment — an argument not addressed, to our knowledge,

by any of the parties. Second, GABEO’s brief approaches

both the question of appellees’ standing and the differences

between race consciousness in the districting process and race

consciousness in other governmental decisionmaking from a

different perspective than that taken by the parties.

WHEREFORE, GABEO moves that the Court permit

the filing of its brief.

Respectfully submitted,

Pamela S. Karlan

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

Georgia Association of Black

Elected Officials

Dated: February 21, 1995

1

T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s

Page

Table of Contents ..................................................... i

Table of Authorities .................................................. ii

Interest of Amicus C u r ia e ....................................... 1

Summary of Argument . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Argument

I. Shaw v. Reno Identified a Narrow Class of

Exceptional Cases in Which Federal Judicial

Intervention into the Political Processes

of Redistricting Is Justified ........................... 5

II. The Differences Between Apportionment and

Other Governmental Decisions Show Why

Race Can Legitimately Be Taken Into

Account in Drawing District Lines . . . . . . 12

III. Shaw v. Reno Must Be Read Narrowly

to Avoid Denying African Americans

the Equal Protection of the Laws

Guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment . . . . 18

Conclusion .......................................................... 21

T a b l e o f A u t h o r it ie s

Pages

Cases

Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984) ............... 3, 10

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) .................. 6, 14

Busbee v. Smith, 549 F. Supp. 494 (D.D.C.

1982), a jf’d, 459 U.S. 1166 ( 1 9 8 3 ) .................. 6

City o f Richmond v. J.A, Croson Co., 488 U.S.

469 (1989) 14

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986) . . . . 2 passim

Dickinson v. Indiana State Election B d.,

817 F. Supp. 737 (S.D. Ind. 1992) ............... 17

Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 500 U.S.

616 (1991) 21

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973) . . 9, 13

Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075 (1993) . . . . 5

Hays v. Louisiana, 862 F. Supp. 119 (W.D.

La. 1994) (3-judge court), probable juris.

noted, Nos. 94-558 and 94-627 21

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) 4, 18-19, 21

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647 (1994) . 2, 5

11

Ill

Johnson v. Miller, 864 F. Supp. 1354 (S.D.

Ga. 1994) (3-judge court) ................................ .. 7

Ex parte Levitt, 302 U.S. 633 (1937) . . . . . . . 10

Lujan v. Defenders o f Wildlife, 112 S. Ct.

2130 (1992)................................................. .. 3, 9

LULAC v. Clements, 999 F.2d 831 (5th Cir) (en

banc), cert, denied, 114 S Ct 878 (1994) . . . 17

Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, 497 U.S.

547 (1990) 13

Pope v. Blue, 809 F. Supp. 392 (W .D.N.C.)

3-judge court), aff’d, 113 S.Ct. 30 (1992) . . . 18

Regents o f the Univ. o f Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S.

265 (1978) 14

Rutan v. Republican Party o f Illinois, 497 U.S.

62 (1990) 12

Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C.

1994) (3-judge court) . .................... 18

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993) . . . . . . 2 passim

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) . . . 5, 8

United States v. Richardson, 418 U.S.

166 (1974) ................................................. 3, 10-11

Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S.Ct. 1149 (1993) . . 5

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) . . . 2, 15

Wygant v. Jackson Board ofEduc., 476 U.S.

267 (1986) . . . . . . . -------. . . . . . . . . . 14, 15

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions

U.S. Const., amend. V ....................... 4, 20-21

U.S. Const., amend. XIV ................................... 20

Civil Rights Act of 1964 (codified as amended

in scattered sections of 42 U.S.C. (1988)) . . . 16

Civil Rights Act of 1991 (to be codified in

scattered sections of 42 U.S.C.) ..................... 16

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,

(codified in 42 U.S.C. § 2000e (1988) . . . . 16

Fair Housing Act of 1968 (codified as amended at

42 U.S.C. § 3601 et seq. (1988)) . ............... 16

Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 (to be

codified at 42 U.S.C. § 3601 et seq.) ............ 16

Voting Rights Act of 1965, (codified as amended

at 42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq. (1988)) . . . . . . 16

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982 (codified

at 42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq. (1988)) ............... 16

iv

V

Other Materials

T. Alexander Aleinikoff & Samuel Issacharoff,

Race and Redistricting: Drawing

Constitutional Lines After Shaw v.

Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 588 (1993) . . . . . . 13

Pamela S. Karlan, The Rights To Vote: Some

Realism About Formalism, 71 Tex. L. Rev.

1705 (1993) .......................................................... .. 13

Pamela S. Karlan, Undoing the Right Thing:

Single Member Offices and the Voting Rights

Act, 77 Va. L. Rev. 1 (1991) ........................... 15

Richard H. Pildes & Richard G. Niemi,

Expressive Harms, "Bizarre Districts,"

and Voting Rights: Evaluating Election-District

Appearances After Shaw v. Reno, 92 Mich.

L. Rev. 483 (1993) ............................. .. 20

Antonin Scalia, The Doctrine o f Standing as

an Essential Element o f the Separation o f

Powers, 17 Suffolk U.L. Rev. 881 (1983) . . 10

S. Rep. No. 92-415, p. 10 (1971)) . . . . . . . . 16

Nos. 94-631, 94-797, 94-929

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1994

Zell Miller, et al.

Appellants,

V.

Davida Johnson, et al.

___________ Appellees.

Lucious Abrams, Jr. et al.

Appellants,

V.

Davida Johnson, et al.

Appellees.

United States

Appellant,

V.

Davida Johnson, et al.

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Georgia

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE GEORGIA

ASSOCIATION OF BLACK ELECTED OFFICIALS

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

I n t e r e s t o f A m ic u s C u r ia e

The Georgia Association of Black Elected Officials

("GABEO") is an organization of African Americans elected

to public office in Georgia at the congressional, state, and

local levels. GABEO is approximately 25 years old and has

2

more than 700 members. Its basic purposes are to promote

excellence in public officials and inclusiveness in

government. Throughout its history GABEO has supported

the adoption of non-dilutive methods of election that ensure

the full participation of all persons in the political and

electoral processes.

S u m m a r y o f A r g u m e n t

This Court has long accepted the proposition that

redistricting inevitably takes into account the competing

claims of political, ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups.

See, e.g., Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647 (1994);

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993); Davis v. Bandemer,

478 U.S. 109 (1986); Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124

(1971). What distinguished the post-1990 round of

reapportionment from its predecessors was not the sudden

emergence of race consciousness but rather the unprecedented

integration of Southern congressional delegations. This

integration was achieved wholly by the state and federal

political branches, without the need for direct judicial

intervention.

Nothing in this Court’s decision in Shaw was intended

to reverse this development or to give the lower courts a

warrant to upset the results of the political process of

redistricting, especially when that process has neither denied

nor diluted any individual’s right to vote. Shaw should be

read narrowly -- to permit lawsuits challenging the creation

of majority-nonwhite districts only when the shape of such

districts represents a clear deviation from the kind of districts

the state has drawn for other politically cohesive groups and

threatens either to exacerbate racial bloc voting or to deny

members of the racial minority within a district fair

3

representation. The Court should also take this opportunity

to make clear that Shaw did not suspend the normal rules for

standing: a plaintiff who alleges nothing more than a

generally available claim that the government has not

complied with the Constitution cannot bring suit. See Lujan

v. Defenders o f Wildlife, 112 S. Ct. 2130 (1992); Allen v.

Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984); United States v. Richardson,

418 U.S. 166 (1974).

Shaw did not hold that all race-conscious districting was

either impermissible or subject to heightened scrutiny. The

Court should take this opportunity to reiterate that

proposition. Districting differs from other governmental

activity in four critical respects that explain why race-

consciousness here cannot be subjected to the same type of

strict scrutiny accorded other race-conscious action.

First, the very purpose of apportionment is to treat

voters as members of groups; thus the usual alternative to

group-based treatment — individualized decisionmaking — is

unavailable.

Second, unlike most other contexts, there are no

objective, neutral, or merit-based criteria that provide

judicially discoverable and manageable standards for selecting

particular district lines.

Third, given decennial reapportionment and the

inherently partisan and subjective nature of the process, an

individual voter has no settled, legally cognizable expectation

of being placed in any particular district.

Fourth, as Shaw’s statement about the inevitable

awareness of race in American politics implicitly recognizes,

racial affiliation often describes politically cohesive

communities of interest. In contemporary America, it may

4

be impossible fairly to represent ostensibly "political"

interests if ethnicity is ignored* Race often serves as a

shorthand or organizing principle for political communities.

Given the intertwining of race and politics, a rule that treats

all race-conscious districting with suspicion would raise

serious questions of administrability: it would demand that

federal courts artificially distinguish between race-based and

political motivations.

Moreover, such a radical expansion of Shaw would raise

a serious constitutional question. Decisions like the one

below and in parallel cases from Texas and Louisiana make

it more difficult for black voters to secure advantageous

districts than for other voters to do so. Requiring regularity

of boundaries for majority-nonwhite districts but not for

majority-white districts constrains the options available to

racial minorities in ways that other groups’ options are not

constrained. This approach turns the Fourteenth Amendment

on its head, making the Amendment’s original intended

beneficiaries — black Americans — the only group whose

political aspirations are stringently limited by considerations

of compactness and regularity of district boundaries. As

such, it would run afoul of this Court’s decision in Hunter v.

Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969), and the equal protection

component of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment.

5

A r g u m e n t

I. Shaw v. Reno Identified a Narrow Class of

Exceptional Cases in Which Federal Judicial

Intervention into the Political Processes of

Redistricting Is Justified

This Court’s decision in Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816

(1993), should be understood in the context of the other

voting rights cases of the 1992 Term. That same Term, this

Court unanimously declined to strike down two other state

apportionments, despite the fact that both processes were

explicitly race-conscious and despite the fact that, in Ohio,

the legislature explicitly and intentionally drew district

boundaries to create majority-black constituencies. See

Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075 (1993); Voinovich v.

Quilter, 113 S.Ct. 1149 (1993). Moreover, Shaw was

decided against the backdrop of this Court’s repeated

holdings that "the power to influence the political process is

not limited to winning elections," Davis v. Bandemer, 478

U.S. 109, 132 (1986); see also Thornburg v. Gingles, 478

U.S. 30, 99 (1986) (O’Connor, J., concurring in the

judgment); Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 153 (1971).

And subsequent to Shaw, this Court once again recognized

that "society’s racial and ethnic cleavages sometimes

necessitate majority-minority districts." Johnson v.

DeGrandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647, 2661 (1994).

The 1990 round of reapportionment reflected the

increased ability of minority voters to "pull, haul, and trade,"

Johnson, 114 S.Ct. at 2661, in the intensely partisan world

of redistricting. Some of the bargaining and horsetrading

was purely internal to state legislatures, where representatives

of the black community now sit in unprecedented numbers.

Sometimes the minority community gained additional

6

leverage from the national political consensus that extended

and amended the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and required

federal preclearance for states like Georgia with a history of

excluding black voters from the redistricting process. See

Busbee v. Smith, 549 F. Supp. 494 (D.D.C. 1982)

(recounting the overt racism in Georgia’s post-1980

congressional reapportionment), aff’d, 459 U.S. 1166 (1983).

The results of the 1990 reapportionment are more than

impressive: for the first time since Reconstruction, the

legislative delegations of Southern states are racially

integrated. More significantly, this long-desired, and long-

resisted, integration was accomplished by the state and

federal political branches, without the need for judicial

intervention. The 1982 amendments and extension of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the post-1990 state legislative

and federal executive responses, reflected "an aroused

popular conscience that sear[ed] the conscience of the

people’s representatives" Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 270

(1962) (Frankfurter, J., dissenting), to make full integration

of the American political process a reality.

This Court’s decision in Shaw was not intended to

reverse, and should not have the effect of reversing, this

salutary development. In Shaw, this Court clearly refused to

hold that this race-consciousness rendered all districting

subject to heightened judicial scrutiny. See Shaw, 113 S.Ct.

at 2824. Rather, it identified three circumstances under

which heightened scrutiny of race-conscious districting is

warranted.

First, and most importantly, Shaw limited judicial

intervention to cases where the challenged district is

"dramatically irregular," id. at 2820, "unusually shaped,"

id ., "extremely irregular on its face," id. at 2824, created

"without regard for traditional districting principles," id.,

"bizarre," id. at 2825, "irrational," id. at 2829, and designed

7

to "separate voters into different districts on the basis of

race," id. at 2828. These repeated references were not

surplus verbiage. Rather, they were intended to convey the

message that black voters were entitled to the same benefits

and opportunities in the political process that all other

"political, religious, ethnic, racial, occupational, and

socioeconomic groups," Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. at 146

(O’Connor, J., concurring in the judgment), have

traditionally enjoyed. If farmers, for example, or Irish-

Americans, or Republicans, or the partisans of a particular

aspirant for office have been able to create districts for

themselves, then black voters should not be denied the same

openings. Thus, Shaw required that challenged majority-

black districts be viewed in context: are they decidedly more

irregular than districts that have been drawn for other

identifiable voting blocs, both in the past and

contemporaneously? As Judge Edmondson’s dissent below

points out, the Georgia Eleventh Congressional District does

not run afoul of this standard: its size is "not particularly

noteworthy"; the length of its borders is "not distinctive"; its

respect for political boundaries "places the Eleventh at the

average for the State’s ten other congressional districts"; and

its use of "land bridges" is reminiscent of previously drawn

majority-white districts within the state. Johnson v. Miller,

864 F. Supp. 1354, 1396 (S.D. Ga. 1994). Using one

commonly employed measure of compactness, the district is

more regular than forty-six other congressional districts. Id.

at 1397. Under these circumstances, the Georgia Eleventh

Congressional District does not fall within the narrow class

of districts subject to heightened scrutiny.

Second, Shaw justified intervention when there was a

concrete danger that a district’s shape would communicate to

elected representatives that "their primary obligation is to

represent only the members of [the majority racial] group,

rather than their constituency as a whole." Shaw, 113 S.Ct.

8

at 2827. This danger must be proved, rather than simply

asserted or presumed:

"the power to influence the political process is not

limited to winning elections. An individual or a

group of individuals who votes for a losing

candidate is usually deemed to be adequately

represented by the winning candidate and to have as

much opportunity to influence that candidate as

other voters in the district. We cannot presume in

such a situation, without actual proof to the

contrary, that the candidate elected will entirely

ignore the interests of those voters. This is true

even in a safe district where the losing group loses

election after election."

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. at 132 (opinion of White, J.);

see also Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 99 (O’Connor,

J., concurring in the judgment); Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403

U.S. 124 (1971). In a case where the plaintiffs do not allege

either that they have been denied the right to vote or that

their votes have been diluted on account of race, they should

be held to the standard for proving that they have not been

adequately represented that was delineated by the Davis

plurality. No proof was offered in this case to suggest that

Representative McKinney has not represented all her

constituents fairly or that the political interests of the

plaintiffs in this case have been "entirely ignorefd]."

Third, Shaw suggested intervention might be appropriate

if districting practices were shown to be "balkaniz[ing]," id.

at 2832, that is, if the districting process "segregate^]"

voters on the basis of race, id. at 2824, and thereby threatens

to "exacerbate ... patterns of racial bloc voting," id. at

2827. Again, however, this Court’s decisions make clear

that polarization cannot simply be assumed; it must be

9

proved. Cf. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 46. Nothing in the record

in this case provides any basis for concluding that the

contours of the Georgia Eleventh Congressional District have

increased the level of racial bloc voting within its territory or

have exacerbated racial polarization.

Nothing in Shaw suggests this Court intended to give

disappointed aspirants for office, citizens across the state, or

individuals who simply disagree with the outcome of the

political process of districting a roving warrant to spend the

remainder of the decade challenging the decennial

reapportionment. Clearly, this Court did not intend to leave

states "trapped between the competing hazards of liability to

minorities if affirmative action is not taken to remedy

apparent ... discrimination and liability to nonminorities if

affirmative action is taken." Wygant v. Jackson Board o f

Educ., 476 U.S. 267, 291 (1986) (O’Connor, J., concurring

in part and concurring in the judgment). The Court was well

aware that the Voting Rights Act’s various prohibitions on

racial vote dilution require states to take race into account in

the districting process; it was also realistic enough to

recognize that legislators would take race into account in any

event. See Shaw, 113 S.Ct. at 2826. Nor did this Court

intend to smuggle in, through the back door, stringent

constraints on the partisan aspects of redistricting which this

Court had realistically accepted in Gaffney v. Cummings, 412

U.S. 735 (1973), and Davis v. Bandemer.

Moreover, a broad reading of Shaw would seriously

subvert this Court’s standing doctrine. This Court has

repeatedly held that standing is not conferred by "a generally

available grievance about government — claiming only harm

to [the plaintiffs’] and every citizen’s interest in proper

application of the Constitution and laws, and seeking relief

that no more directly and tangibly benefits [them] than it

does the public at large." Lujan v. Defenders o f Wildlife, 112

10

S. Ct. 2130, 2143 (1992).1 As Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S.

737, 754 (1984), explained, standing requires more than a

"shared individuated right to a Government that obeys the

Constitution."

Read broadly, Shaw would essentially overrule this

Court’s decision in United States v. Richardson, 418 U.S.

166, 176-77 (1974). There, the Court held that a plaintiff

who claimed that he could not "properly fulfill his obligations

as a member of the electorate in voting for candidates

seeking national office" without detailed information about

the CIA’s budget lacked standing to challenge a statute which

relieved the CIA of the obligation to make such disclosures.

Richardson’s complaint, like the claims of the plaintiffs in

Johnson and the other post-Shaw cases, "is plainly

undifferentiated and ’common to all members of the public.’”

Of particular salience to this case, Richardson recognized,

relying on Ex parte Levitt, 302 U.S. 633 (1937), that "if [the

plaintiffs] allegations were true, they made out an arguable

violation of an explicit prohibition of the Constitution. Yet,"

the Court concluded, "even this was held insufficient to

support standing because, whatever Levitt’s injury, it was

one he shared with ’all members of the public.’"

Richardson, 418 U.S. at 178. Richardson's analysis can be

translated directly into the context of this case:

It can be argued that if [appellees are] not permitted

to litigate this issue, no one can do so. In a very

real sense, the absence of any particular individual

or class to litigate these claims gives support to the

See also Antonin Scalia, The Doctrine o f Standing as an

Essential Element o f the Separation o f Powers, 17 Suffolk U.L. Rev. 881,

881-82 (1983) ("[Cjourts need to accord greater weight than they have in

recent times to the traditional requirement that the plaintiffs alleged injury

be a particularized one, which sets him apart from the citizenry at large.").

11

argument that the subject matter is committed to the

surveillance of Congress, and ultimately to the

political process. Any other conclusion would

mean that the Founding Fathers intended to set up

something in the nature of an Athenian democracy

or a New England town meeting to oversee the

conduct of the [reapportionment process] by means

of lawsuits in federal courts. The Constitution

created a representative Government with the

representatives directly responsible to their

constituents that the Constitution does not

afford a judicial remedy does not, of course,

completely disable the citizen who is not satisfied

with the "ground rules" established by the Congress

[in amending and extending the Voting Rights Act]

... Lack of standing within the narrow confines of

Art. Ill jurisdiction does not impair the right to

assert his views in the political forum or at the

polls.

Richardson, 418 U.S. at 179. To confer citizen standing

whenever a single individual disapproves of the outcome of

the redistricting process — without requiring that the plaintiff

allege and prove the specific injuries Shaw identified —

would plunge the Court far further into the political thicket

than any of its previous forays. Cf. Davis v. Bandemer, 478

U.S. at 153 (O’Connor, J., concurring in the judgment)

(criticizing the plurality opinion because under its reasoning

voters would be able to challenge apportionments if they

lived outside the contested district or, indeed, outside the

state).

Accordingly, the Court should take this case as an

opportunity to reiterate the limited intervention authorized by

Shaw and to instruct the lower courts to permit lawsuits

challenging majority-nonwhite districts in the absence of any

12

claim of denial or dilution of the right to vote only when such

districts both represent a clear departure from the state’s

normal districting practices and threaten either to exacerbate

racial bloc voting within the challenged districts or to deny

members of the numerical racial minority within the district

fair and adequate representation and only when the plaintiffs

can point to a concrete and particularized injury that they

have suffered as a result of creation of the challenged

districts.

II. The Differences Between Apportionment and

Other Governmental Decisions Show Why Race

Can Legitimately Be Taken Into Account in

Drawing District Lines

Shaw recognized that "redistricting differs from other

state decisionmaking in that the legislature always is aware

of race when it draws district lines, just as it is aware of age,

economic status, religious and political persuasion, and a

variety of other demographic factors.” Shaw, 113 S.Ct. at

2826 (emphasis in original). In fact, the differences between

redistricting and other governmental decisionmaking go

beyond the legislature’s mere awareness of race. These

differences explain why race-conscious districting cannot be

subjected to the same type of strict scrutiny accorded other

race-conscious action.

It is not just with regard to race that different rules apply

in the redistricting arena. In Rutan v. Republican Party o f

Illinois, 497 U.S. 62, 74 (1990), for example, this Court

invoked the general principle that governmental distinctions

among individuals based on their political affiliation are

subject to heightened scrutiny; it held that "[ujnless ...

patronage practices are narrowly tailored to further vital

government interests, we must conclude that they

13

impermissibly encroach on First Amendment freedoms."

Nonetheless, the Court has repeatedly upheld intentional

political gerrymanders -- which by definition assign

individuals to districts on the basis of political affiliation -

without requiring any special justification. See, e .g ., Davis

v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986); Gaffney v. Cummings,

412 U.S. 735 (1973).

The rationale for the different treatment of redistricting

lies in the fact that the very purpose of apportionment is to

treat voters as members of groups and to choose which of

their group characteristics should be used to aggregate them

for the purpose of electing representatives. See T. Alexander

Aleinikoff & Samuel Issacharoff, Race and Redistricting:

Drawing Constitutional Lines After Shaw v. Reno, 92 Mich.

L. Rev. 588, 600-01 (1993); Pamela S. Karlan, The Rights

To Vote: Some Realism About Formalism, 71 Tex. L. Rev.

1705, 1712-13 (1993). Thus, apportionment decisions

virtually never treat citizens as individuals.2 Instead,

apportionments rely on a series of gross, if politically astute,

generalizations about the likely voting behavior of

demographically identifiable groups.

By contrast, other sorts of government decisionmaking

begin from "the simple command that the Government must

treat citizens as individuals, not as simply components of a

racial, religious, sexual or national class." Metro

Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, 497 U.S. 547, 602 (1990)

(O’Connor, J. dissenting) (internal quotation marks omitted;

Incumbent legislators, their relatives, and major campaign

contributors sometimes form an exception to this general rule, and these

exceptions can often account for irregularities in district shape. See Brief of

Appellants Abrams et al. (describing how several distinctive geographic

features of the Eleventh District reflect legislators’ desires to place

themselves or family members within particular congressional districts).

14

emphasis in original). In City o f Richmond v. J.A. Croson

Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989), for example, the alternative to

racial set-asides was awarding contracts to the individual with

the lowest competitive bid. In Wygant v. Jackson Board o f

Educ., 476 U.S. 267 (1986), the alternative to using race in

deciding which teachers should be laid off was reliance on

individual seniority. In Regents o f the Univ. o f Cal. v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), the alternative to rigid race

conscious admission to medical school was resort to test

scores, prior academic performance, and individual promise

within the profession. The Court’s analysis rested on two

premises: first, that reliance on race can derogate from

objective, race-neutral, individualized selection criteria, and,

second, that race-conscious treatment may unnecessarily

trammel the interests of individual citizens whose legitimate

expectations have been foiled.

Neither of these principles operates with the same force

on apportionment decisions. First, "[t]he key concept to

grasp [about reapportionment] is that there are no neutral

lines for legislative districts." Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S.

at 129 n. 10 (opinion of White, J.).3 There may be a set of

"[traditional districting principles," Shaw, 113 S.Ct. at 2824

— ranging from such easily measurable criteria as equality of

population and contiguity through such inherently subjective

criteria as respect for communities of interest and "political

fairness." But beyond equipopulosity, there are few

"judicially discoverable and manageable standards," Baker v.

Carr, 369 U.S. at 217, for deciding the relative weight of

these interests with regard to where particular district lines

should be placed. The tradeoff among protection of

incumbents (with its attendant benefits to a state from

Quoting Robert G. Dixon, Jr., Fair Criteria and Procedures

fo r Establishing Legislative Districts 7-8, in Representation and Redistricting

Issue (EL Grofman, A. Lijphart, R. McKay, & H. Scarrow eds. 1982).

15

legislative seniority), geographic compactness, and partisan

concerns — to give just one example — is a "political question

in the truest sense of the word." Davis v. Bandemer, 478

U.S. at 145 (O’Connor, J., concurring in the judgment).

Moreover, given decennial reapportionment and the

overtly partisan nature of the redistricting process, voters

simply have no "settled expectations," Wygant, 476 U.S. at

283-84 (opinion of Powell, J.), about the contours of the

district in which they will find themselves. Georgia gained

a congressional seat between 1980 and 1990, and uneven

growth of population within the state required further

adjustments of 1980 district lines. Thus, no voter had any

legally cognizable right to be placed in any particular district.

Since the votes of the plaintiffs in this case and the other

post-Shaw litigation were neither denied nor diluted, none of

their expectations about the voting process were in any way

impaired.

Not only is this Court’s concern about objective

standards not relevant in the redistricting context, but the

second premise of its affirmative action jurisprudence — that

race-conscious behavior distinctively disadvantages the

interests of white citizens — is also inapposite. "Traditional

districting principles" have always focused on "the competing

claims of political, religious, ethnic, racial, occupational, and

socioeconomic groups." Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. at

146 (O’Connor, J., concurring in the judgment) (emphasis

added). In the districting process, members of racially-

defined groups occupy a position similar to many other

politically cohesive groups such as "union oriented workers,

the university community, religious or ethnic groups

occupying identifiable areas of our heterogeneous cities and

urban areas." Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. at 155.. Such

practices as the ethnically balanced ticket are a mainstay of

American political history. See Pamela S. Karlan, Undoing

16

the Right Thing: Single Member Offices and the Voting Rights

Act, 77 Va. L. Rev. 1, 35-36 (1991).

As long as all citizens are able to vote and no

identifiable group’s votes are diluted, the traditional values

of descriptive representation and an ethnically diverse cast of

elected officials serves a variety of important values. Fair

representation of racially defined interests is critical to the

functioning of the political process. This insight underlies

this Court’s racial vote dilution jurisprudence, which

recognizes that individuals’ policy preferences may often be

correlated with, and sometimes even caused by, their racial

identity. Much modem legislation is concerned with issues

of racial discrimination,4 and members of racial minority

groups may be specially concerned with these issues. "The

exclusion of minorities from effective participation in the

bureaucracy not only promotes ignorance of minority

problems in that particular community, but also creates

mistrust, alienation, and all too often hostility toward the

entire process of government." Wygant, 476 U.S. at 290

(O’Connor, J. concurring) (quoting S. Rep. No. 92-415, p.

10 (1971)). Shaw sought to balance the danger to the

perceived legitimacy of government from race-conscious

redistricting against the danger to the perceived legitimacy of

4 See, e.g. , Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78

Stat. 214 (codified as amended in scattered sections of 42 U.S.C. (1988));

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437 (codified as

amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq. (1988)); Fair Housing Act of 1968,

Pub. L. No. 93-284, 82 Stat. 81 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 3601

et seq. (1988)); Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No.

92-261, 86 Stat. 103 (codified in scattered sections of 42 U.S.C. §

2000e(1988); Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L. No. 97-205,

96 Stat. 131 (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq. (1988)); Fair Housing

Amendments Act of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-430, 102 Stat. 1619 (to be

codified at 42 U.S.C. § 3601 et seq.); Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L.

No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071 (to be codified in scattered sections of 42

U.S.C.).

17

government posed by lily-white legislative delegations from

racially diverse jurisdictions. The decision in this case and

in its companion lawsuits from Texas and Louisiana stems

from the lamentable blindness of the district courts to the

latter danger.

Finally, in contemporary America, it may be impossible

fairly to represent ostensibly "political" interests if ethnicity

is ignored. In the real world race often serves as a shorthand

or organizing principle for political communities of interest.

Consider, for example, blacks in Marion County, Indiana.

In Whitcomb v. Chavis, residents of inner-city Indianapolis

challenged the state’s use of multi-member state legislative

districts, claiming that the scheme produced unconstitutional

racial vote dilution. This Court disagreed: black voters lost

not because they were black, but because they were

Democrats: "The voting power of ghetto residents may have

been ’cancelled out’ as the District Court held, but this seems

a mere euphemism for political defeat at the polls." 403

U.S. at 151. In Davis v. Bandemer, black residents of inner-

city Indianapolis again challenged the Indiana scheme and

again lost because their overwhelming support of Democratic

candidates showed that it was politics, not race, that caused

their exclusion. 478 U.S. at 118 n. 8. But in response to a

post-Gingles challenge under section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act to the very districts upheld in Davis, the state agreed to

abandon its multimember scheme and create several majority-

black single-member districts. See Dickinson v. Indiana

State Election Bd., 817 F. Supp. 737 (S.D. Ind. 1992)

(recounting the history of the section 2 litigation).

This overlapping of racial and political affiliations is a

commonplace in contemporary politics. See also LULAC v.

Clements, 999 F.2d 831, 850-55 (5th Cir) (en. banc)

(determining that black candidates for judicial office lost

because they were Democrats, not because they were black),

18

cert, denied, 114 S Ct 878 (1994). The decision by the

unsuccessful Republican plaintiffs in a political

gerrymandering challenge to North Carolina’s congressional

reapportionment, Pope v. Blue, 809 F. Supp. 392

(W .D.N.C.) (three-judge court), aff'd, 113 S.Ct. 30 (1992),

to recast themselves as plaintiff-intervenors in Shaw v. Hunt,

861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994) (three-judge court), is

another pointed illustration of this reality.

Given the intertwining of race and politics, an expansive

rule that treats all race-conscious districting with suspicion

raises serious questions of administrability. Suppose, for

example, that Democrats had controlled the Indiana

reapportionment process and that they had drawn districts

that had advantaged Democrats, including the

overwhelmingly black Democratic community of inner-city

Indianapolis, and that white suburban Republicans challenged

the plan. Would the level of judicial scrutiny depend on a

federal court’s ability to disentangle the political and racial

aspects of the legislature’s decision? Would plans that favor

black Democrats be accorded more searching scrutiny than

plans that advantaged white Democrats? Such as result

would, we suggest in the next section, raise serious

constitutional questions.

III. Shaw v. Reno Must Be Read Narrowly to Avoid

Denying African Americans the Equal

Protection of the Laws Guaranteed by the Fifth

Amendment

In Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969), this Court

struck down a provision of the Akron City Charter that

provided that:

"Any ordinance enacted by the Council of The

City of Akron which regulates the use, sale,

19

advertisement, transfer, listing assignment, lease,

sublease or financing of real property of any kind

or of any interest therein on the basis of race,

color, religion, national origin or ancestry must

first be approved by a majority of the electors

voting on the question at a regular or general

election before said ordinance shall be effective."

Akron City Charter § 137. The Court explained that the

fatal weakness in the ordinance was that it "drew a

distinction between those groups who sought the law’s

protection against racial, religious, or ancestral

discriminations" and those involved in "the pursuit of other

ends." 393 U.S. at 390. The "reality" of such a provision,

the Court explained, is that "the law’s impact falls on the

minority" because they are more likely to "benefit from laws

barring racial, religious, or ancestral discriminations ...."

Id. at 391. Section 137 involved impermissible

discrimination on the basis of race, the Court concluded,

because "the State may no more disadvantage any particular

group by making it more difficult to enact legislation in its

behalf than it may dilute any person’s vote or give any group

a smaller representation than another of comparable size."

Id. at 393.

Suppose a state were to pass a statute declaring that "any

group of voters shall be entitled to petition the legislature to

draw a congressional district in which members of the group

form a majority of the electorate: Provided, That if the

primary common characteristic of the group is the race or

color of its members, the group shall be entitled to constitute

the majority in a district only if it can persuade the

legislature to draw a district with a dispersion score of .40 or

20

above or a perimeter score of 3 0 or above. "5 Such a statute

would clearly run afoul of Hunter, because it would treat

voters who politically affiliate along racial lines differently

from voters who choose to affiliate along other shared

characteristics, and would make it more difficult for them to

secure favorable apportionment plans. And although the

hypothetical statute might be race-neutral on its face, this

Court would surely conclude that in reality it would burden

black voters more heavily, since racial bloc voting and their

shared interest in governmental policies to combat racial

discrimination make them especially likely to seek race

conscious apportionments that provide them with majority-

black districts. Such a hypothetical law, like the provision in

Hunter, would make it more difficult for black voters than

for other groups to enact favorable apportionment legislation,

since it would constrain their available options in ways that

other groups’ options were not constrained.6 To uphold

such an ordinance would turn the Fourteenth Amendment on

its head, making the Amendment’s original intended

beneficiaries — black Americans — the only group whose

political aspirations are stringently limited by considerations

of compactness and regularity of district boundaries.

If that hypothetical statute would violate the Fourteenth

Amendment - as clearly it would - then a similar federal

judicially created rule would also run afoul of the

Constitution. Federal courts are bound by the equal

protection component of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

For descriptions of these technical terms for measuring

compactness, see Richard H. Pildes & Richard G. Niemi, Expressive Harms,

"Bizarre Districts," and Voting Rights: Evaluating Election-District

Appearances After Shaw v. Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 483, 553-56 (1993).

Just as clearly, a statute that provided that “a majority-white

district may be any shape but a majority-black district must be regular in its

boundaries," would clearly violate the equal protection clause.

21

Amendment. Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 500 U.S.

614, 616 (1991). Thus, the federal courts cannot place

unique barrier in the path of black voters’ seeking legislative

plans of their choice.

If Shaw is read narrowly, it certainly does not conflict

with the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection.

Under such a reading, the Constitution simply requires

heightened scrutiny for race-conscious districting when the

outcome of the process is districts that are never drawn for

other groups. But if Shaw is read broadly, as the courts

below have shown themselves prone to do, such a reading

poses serious equal protection problems. To render districts

suspect when they are drawn at the behest of the black

community -- when farmers, Republicans, incumbents,

"North Louisiana English-Scotch-Irish," Hays v. Louisiana,

862 F. Supp. 119 (W.D. La. 1994) (three-judge court),

probable juris, noted, Nos. 94-558 and 94-627, can obtain

equivalently shaped districts — poses precisely the equal

protection threat identified in Hunter. This Court should

make clear that black voters are entitled to an equal

opportunity to participate in the redistricting process and to

benefit from the kind of traditional districting practices,

including the drawing of oddly shaped districts, that all other

political groups enjoy.

C o n c l u s io n

The decision of the district court represents both an

incorrect reading of this Court’s opinion in Shaw v. Reno and

an unwarranted federal judicial intrusion into the political

process. Accordingly, this Court should reverse the

judgment of the court below and remand the case with

directions to dismiss the plaintiffs’ complaint.

22

Respectfully submitted,

Pamela S. Karlan

Counsel o f Record

580 Massie Road

Charlottesville, VA 22903

(804) 924-7810/7536 (Fax)

Eben Moglen

Columbia Law School

435 West 116th Street

New York, NY 10027

(212) 854-8382/7946 (Fax)

Attorneys fo r Amicus Curiae

... ^ V ...