League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) v. The Attorney General of the State of Texas Supplemental Appendix to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) v. The Attorney General of the State of Texas Supplemental Appendix to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1993. 2bea7ada-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bb7251a4-da0b-49bb-a323-12bb7c031bdd/league-of-united-latin-american-citizens-lulac-v-the-attorney-general-of-the-state-of-texas-supplemental-appendix-to-the-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

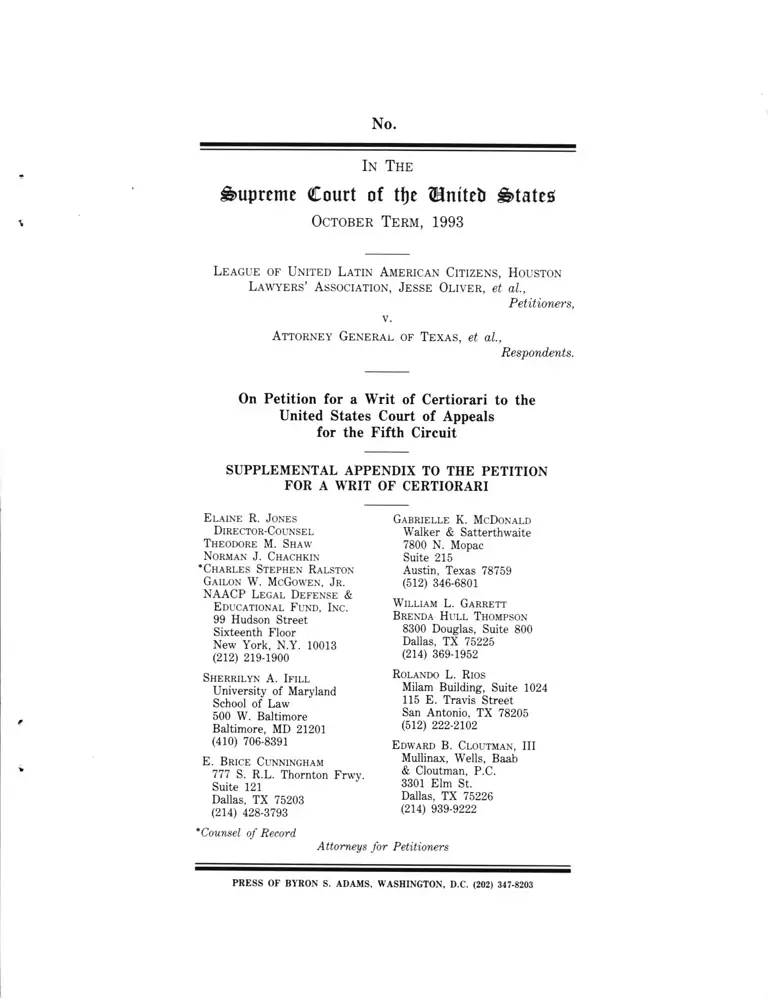

N o.

In T h e

Supreme Court of ttjc BnttctJ States

\ O c t o b e r T e r m , 1993

League of United Latin American Citizens, Houston

Lawyers’ Association, Jesse Oliver, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Attorney General of Texas, et al,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court o f Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

SUPPLEMENTAL APPENDIX TO THE PETITION

FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

* Charles Stephen Ralston

Gailon W. McGowen, Jr.

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

University of Maryland

School of Law

500 W. Baltimore

Baltimore, MD 21201

(410) 706-8391

E. Brice Cunningham

777 S. R.L. Thornton Frwy.

Suite 121

Dallas, TX 75203

(214) 428-3793

Gabrielle K. McDonald

Walker & Satterthwaite

7800 N. Mopac

Suite 215

Austin, Texas 78759

(512) 346-6801

W illiam L. Garrett

Brenda Hull Thompson

8300 Douglas, Suite 800

Dallas, TX 75225

(214) 369-1952

Rolando L. Rios

Milam Building, Suite 1024

115 E. Travis Street

San Antonio. TX 78205

(512) 222-2102

Edward B. Cloutman, III

Mullinax, WTells, Baab

& Cloutman, P.C.

3301 Elm St.

Dallas, TX 75226

(214) 939-9222

* Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Petitioners

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

The Tables included in this Supplemental Appendix to

the Petition for a Writ o f Certiorari in this case are those

referred to in the opinion o f the United States District Court

for the Western District o f Texas set out in the Appendix to

the Petition for Writ o f Certiorari at pp 487a-549a.

APPENDIX "A

Plaintiffs' & Plaintiff-Intervenors'

Statistical Analysis

**- *

RACIAL DIFFERENCES IN CANDIDATE PREFERENCES IN DISTRICT JUDGE

ELECTIONS IN HARRIS COUNTY. TEXAS

GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1980-1988

Prepared by Richard L. Bngetroa, Ph.D

I

HOMOGENEOUS PRECINCTS ------------BIVARIATE REGRESSION- WITH CONTROL FOR HISPANICS

Year Black

Candidate

(Party)

% of Non-Black

Votee

X of Black

Vot«u

CorreUt Ion

Coefficient

% of Non-Black

Votee

X of

Black Votee

Partial

Correlation

X of Black

Votee VeW'

1080 Bonner

(Deaocretlc)

38.6 06.0 0.B22 37.8 103 0.909 98.4

-J

1082 Jaaea

(Deaocretlc)

33.6 07.5 0.799 34.8 104.2 0.895 99.3

19112 Routt (W)

(Deaocretlc)

38.3 98.1 0.798 37.7 104.6 0.896 99.9

1082 Ward

(Democratic)

34.7 97.7 0.801 33.8 104.2 0.893 99.3

V-/

1084 Berry

(Deaocretlc)

34 07.3 0.883 32.8 102.7 0.922 100

1084 Jackeon

(Deaocretlc)

30.6 97.7 0.880 29.3 103.5 0.942 100.3

1084 Lee

(Deaocretlc)

36.4 07.8 0.881 33.2 103.2 0.938 100.5

N-/

1088 Berry

(Deaocretlc)

38.3 07.7 0.831

\

34.2 103 0.916 99.4

1086 Pluaaer

(Deaocretlc)

37 97.0 0.847 36 103.1 0.912 99.6

w

1088

«

Proctor

(Republican)

32.8 4.6 -0.836 53.6 1 . 1 -0.899 3.9

V

1086 Welker (W)

(Deaocretlc)

40 98.2 0.847 39.1 103.3 0.882 99.9

1088 Berry

(Deaocretlc)

32.6 97.3 0.860 31.1 103.1 0.897 99.4

1088 Fitch

(Democratic)

36.0 97.7 0.849 35.4 103.4 0.686 99.7

W

1066 Jackeon 33.4 08 0.B56 31.8 103.9 0.928 100.1

(Democratic)

PLAINTIFF'S

IwflfflU.

Ur x ]

A . .

r '

r'

li

i

- I oox i.16’0 r t o i B'9C

/*\ X OOl »26’0 6 ‘COI 9 * 2C

c o o x 2 6 0 8 ' COX L ' LC

4

\

z t o * o 86 C' 8C

(3U*-l30Ma)

jvouvds 886X

090 0 6 * 26 C ‘»C

(DI4*JDO«i»a )

jaavnid 886X

6 * 0 0 c e o 2*6C

(3I)aj3oa*a)

••T 8861

I ' A

BLACK JUDICIAL CANDIDATES IN HARRIS

YEARS 1080 - 1088

Year Election Name Outccam

1060Primary Judclml Election Alice Bonner Unopposed

James Mildrow Won

Fred Reynolds Irst

lOBOGeneral Judicial Election Alice Bonner Lost

Jamas Muldrow Lost

1082 Primary Judicial Election John James tkmppoaed

James Muldrow Unopposed

John Paavwy Unopposed

Thomas Routt Unopposed

Clark Gable Ward Unopposed

1082 General Judicial Election John James Lost

Jamas Muldrow boat

John Peevy Unopposed

TV*mas Routt Vtan

Clark Gable Hard Lost

1084 Primary Judicial Election Weldon Berry Unopposed

Carolyn D. Hobson made runoff

Freddie Jackson made runoff

Shelia J. Lee Won

Kenneth Levi Lost

Jin Muldrow Lost

1084 Rimoff Election Carolyn D. Hobson Win

Freddie Jackson Won

1064 General Election Weldon Berry hat

TEXAS

Sect lcm Notes

BOth State District Court (civil) ran as an lncimfcant

Coimty Criminal Court No. 6

County Criminal Court No. 10

80th State Dlatrlct Court

BOth County Criminal Court No.6

262nd State Dlatrlct Court (criminal court)

County Criminal Court No. 6 had bean appointed; ran aa Incumbent

246th State Dlatrlct Oourt (family law)

208th State Dlatrlct Court

281at State Dlatrlct Court (civil court)

262nd State Dlatrlct Court (criminal court)

County Criminal Court No. 6 had bean appointed, ran aa Incumbent

246th State Dlatrlct Court (faadly lam)

208th State Dlatrlct Court (criminal court)

2Blat State Dlatrlct Court (civil court

BOth State District Court (civil)

County Civil Court at lew • 3

178th State Dlatrlct Court (crhalnml)

215th State Dlatrlct Court (civil)

333rd State Dlatrlct Court (civil)

351th State Dlatrlct Oourt (criminal)

County Civil Court * 3

178th State Dlatrlct Court (criminal)

Both State Dlatrlct Oourt (civil)

IBM Primary E le ct io n

IBM R u n-off

1«M J u d ic ia l E le ct ion s

Carolyn D. Hobson Ioa t

Fraddla Jackson Lost

S t a l ls J . Laa Ioa t

Barry Haitian (D) Ikuppomad

Freddie Jackacn (D) Ioa t

Chary 1 K. I rv in (R) U n w o u d

Rsymcnd T lshar (D) Han

Bennie F itch (D) U Tc(paad

Hobacn, Carolyn (D) UhOKpcaad

S t la la L . Jackacn (D) Han

J o in Pamvy (D) lh \ | ia a 1

Matthew Pluamar, S r. (D) Uhoppoaad

Maala P roctor (R) Uhopponsd

Rsyno Ida, Frad (D)

Ttanaa H. Routt (D) Ubqp(poaad

Carl H alkar, J r . (D)

Francis N lllla n s (D) I h f p s a d

Frad Reynolds (D) Ioa t

Carl H alkar, J r . (D) Han

C arl H alkar, J r . (D) Won

Carolyn D. Hutmon (D) Han

M»tthma Pluamar S r. (D) Ioa t

B cm la F itch (D) Io a t

Raymond Flahsr (D) Ioa t

Ualdon Barry (D) Lost

County Civil Court at U u 9 3

178th Stats District Court (criminal)

213th Stmta District Court (civil)

281 Civil District

283 Civil District

County Criminal Court 9 3

Lost lo Frank 0. Molt a

County Crlmlnsl Court 9 14 vain ovsr Hls|«nlc, Angel Frags

Ocavtty Crlmlnsl Court 9 13

County Civil Court • 3

Probata 9 «

lnomfcant

Stats Family Court 246 lncimbant

133 Ststs Civil

Stats Family 9 243

lnoabant

County Criminal Court No. 11 mala It to runoff, one of flue candldeti

runnlrg for County Crlm. Ct. No. 11.

Stats Criminal Court 208 Incumbent

Ststs Criminal 83 mads It to run-off

County Criminal Court 9 4 lncuatmnt

County Crlmlivlal Court No. 11 Lost to David Mandooa In run-off;

Mandcua svantually won.

Stmts Crlmlnlsl 85 Wun against lajjps Ssllnsa

Ststs Crlmlnsl Court 183 Hun over Gmorga Godtln

County Civil Court 3 Hon over Allan Hughes

133 Ststs Civil Incumbent

County Criminal Court 13

Let to f nmir MuCorkle

Incumbent

Lost to Mark Atkinson

County Criminal Court 14 tost to Jim Barklay

281 State Civil Lost to Iouls Moors

I M S Primary Election

l H I O n n l Election

Francla HI 11 luma (D) Lout

9halU J. Lae (D) [oat

Mem la Proctor (R) [oat

Cheryl 1. Irvin [oat

IhoaM H. Routt (D) Ohcfpoaad

John W. Paavy (D) tkoppoaad

Ban Durant [oat

Bonnie Fitch Uhoppoead

Ray aond Flahar [oat

Matthew M. "l i aim Dnoppoaad

Maiden Barry □hoppoaad

BaMarly Spancer Mon

Fraddla Jackaon Hen

Bonnie Fitch [oat

Sheila J. Laa [oat

Matthew W. Pliaaaer [oat

Malden Barry [oat

Beverly Spanoer [oat

Fraddla Jackaon [oat

*a

County Criminal Court 4 lncimbant

Lout to Jaaaa R. Andaracn

Probata 1 4 tout to Bill McCulloch

State Paally Court 245 [oat to Henry Schubla

County Crlmlrml Court 3 [oat to J lamia Duncan

Stata Criminal Court 206 Incumbent

State Family Court 246 Incumbent

174th Civil Dlatrlct Court

132nd Civil Dlatrlct Court

ran agalnat Crag Glaaa

177th Criminal Dlatrlct Court

133rd Civil Dlatrlct Court

80th Civil Dlatrlct Court

333rd Civil Dlatrlct Court

213 Civil Dlatrlct Court

ran agalnat Ml run lorn

152nd Civil Dlatrlct Court ran agalnat Jack O'nall

293th Civil Dlatrlct Court ran agalnat Dan Downey

133rd Civil Dlatrlct Court ran agalnat Umar KjCorkla

80th Civil Dlatrlct Court ran agalnat HI 11 lam R. Powell

333rd Civil Dlatrlct Court ran agalnat Davia Wllaon

213 Civil Dlatrlct Court ran agalnat Cana Omahara

•

l h- 2

I

h a

i

j IMM*

(UNJO)

2*001 116* £*701 6*9£ 798* £*84 6 *Z£ j »a ) io 8861

8*2 916*-

J • | ,

S I - Z*IZ

l

i

2 / 8 *- £*7 9*0Z

(d»»)

9841

9*001 126* 9*701 1 9*9£ 119 ’ ' ' r *86 S*Z£

(e«a)

/ a | s u | i 9861

1*64 *76* l* £ 0 l 9*0£ 206*

'1 ,

S*Z6

\

6 *1 £

(uaa)

o»|Mrt 7861

2*64 176*

■ :»

2 *£0 l m

1

2C6*

'i ■ •

7*Z6 0*0£

(waa)

X a j s u j j 7861

8*2 2W - S O - 8*19 768’ * S*£

i

9*09 '

(dan)

7861

2 / 4 216*

i

1

S*00t 9*8£ S98* 1*86 Z*6£

i

(uiaa)

u u ja 0861

saiOA

>P«|9 |<> x

uo) ivi j j j J03 33JOA 34JO,\

>PO|8 jo x V « l f l - u o .1 jo *

)UO |3)JJ903

uo j m j a j j b ]

«»o ,\

V « 1 8 jo X

s o »oa

X30|8-LOf| jo x

7 (A >J "d)

o ja p ip u g ]

V « |8

j« a .i

3|ued9)H JOj )o j)u o ] m .in G oJssa lU Sa 3)O |J0A -|g S io u p a j j snoauoBcxjjoH

c

• i

S N O iiD JU lV lD ic n r jo s i s n m 4 • 1

•

1

■ M !

1 • 11

.*n i ; 1 ’ • ■ : ■ ’ , • ;

, , , . ,.v A J , Nnb D s v ^ i v a ,

* • • I

• ' 11 , < l« 1

i

•“ * 1 ' , | r i : i>, • m 'O i i!*<!: r ; i i ’ •

1• . ; C, • . : • .

V f ' ' [ i i • «Vl " v " • i i

.1.1. I M i '

ESTIMATES O r EiHNIC GROUP VQTNG IN BEXAR COUNTY DISTRICT COURT ELECTIONS:

1982 General Election

District Court #144

Barrera (Hispanic)

Slohlhandski

Tolal

District Court if 290

Delgado (Hispanic)

Berchelman

Total

1384 General Election

District Court #37

Davila (Hispanic)

Cornyn

Total

1906 General Election

District Court #265

Cisneros (Hispanic)

Peeples

Tolal

1903 General Election

District Court #73

Mireles (Hispanic)

Bowles

Tolal

District Court #225

Serraia (Hispanic)

Specia

Tolal

— ?\

Bivariate Regression Analysis

Pearson rj Estimates lor: '

Siq. |Hispanics|NonHispanics

Homogeneous Precincl Esl.

90-1007.1 9 0 - 1 0 0 7 .

Hispanic I Non-Hispanic

Are ethnic

groups

polarized?

Does

Hispanic

choice win?

- . 8 0

i

1 i

4

t YES ND

. 0000 1 7 77 24 74

83 23 i 7 6 26

' 1 0 0 ;• 1 00 1 00 . 1 00 ,

• 87

i. !

1

YES ND

. 0000 103 1 8 92 21

- 3 82 8 79

• 100 1 00 100 " 1 00

.67 ll 1

YES ND

. 0000 104 26 73 35

- 4 74 27 65

100 1 00 100 1 00

.68 '

YES ND

. 0000 95 1 2 I 88 22

5 88 ' 1 2 78

100 1 00 100 1 00

.67 YES YES

. 0000 106 35 9 3 37

- 6 6 5 ; 7 63

100 100 , 1 00 1 00

.86 ( YES ND

.0000 103 28 ! 9 1 33

- 3 72 9 67

100 100 100 1 00

HnUb r i

i » r: -

! ? - -J

:

i/»

I

I •-

ESTIMATES OF ETHNIC GROUP VOTING IN TARRAKT COUNTY ELECTIONS 1906-1908

1986 General Election

Cruet. V r r f . C rt. P i 4

Sal vent (Block)

Drago

Total

Crist, tr is t. C rt. P i f '

Slums (Block) i

Goldsmith

Total

1988 Deto Primary

P re s id e n t

Jackson (Black)

Gore ♦Simon ri. aijRouche af(ar

TolaJ

1938 General Electio^

Crict. P rs t. C rt . P i 2 .

Davis (Black)

. Dsnphinot

Total

| Partial r Repression Estimate s

Black Anglo

Hoiiiogen*

Elsck

:Ous Estimates

Anglo

Are e'hmc groups polamedv

B/A

Does Black

choice win?

.87

7 46 6 41 HO HO

93 54 94 59

too 100 100 100

-.80

15 49 11 44 HO NO

85 51 89 56

100 too 100 100

.93 ' 1

1

l) r'» :• M • ! YES YES

99 14 93 16

fOukakis 1 e6 7 84

100 100 100 100

.90 !

r-'i i J

■' r \ \ YES NO

too 42 98 50

0 58 2 50 '

100 100 100 100

r

I

/

ESTIMATES OF ETHNIC GROUP VOTING IN TARRANT CO. ELECTIONS 1982-1988

Bivariate Regression Analysis Are ethnic Does *

Pearson r Estimates for: groups polarized? Black

SlQ Blacks I wnites B/A choice win?

1982 Democratic Primary

Co. Criminal Crt. P I / .82 YES NO

Hicks (Black) .0000 87 38

Coffee 13 62 -

Total 100 100 ►

1986 Democratic Primary

Co Criminal Crt. P I / .76 YES NO

Ross .0000 57 11 -

Go I ̂ feather-* Ross-* Pounds* Cl ark 43 89 » - •

Total 100 100 • **

1986 General Election . . .

Crlm. Dtst. Crt. P I 4 -.63 - . •

Salvant (Black) - R 0000 3 55 YES YES

Drago 97 45

Total -100 100 - - ■

- -

Crlm. D lst Crt P I /

'lO*01 • L -

Stums (Black) - R .0000 9 57 YES NO - 7

Goldsmith - D 91 43 *

Total

1988 General Election

100 100 ! > ::.

Criminal D ist C rt P i 2 .62 YES NO r ;

C. Davis(Black)- D .0000 103 40 —

Dauphlnot - R -3 60 . .

Total 100 100

Source: Numbers are from analyses Conducted by Delbert Teecel, Department of urban Studies,

Univ of Texas at Arlington

f .

Z i 1 .. r i

1 s::i.iUT

• '"A * '

; _ i l l s ' ^

v

ESTIMATES OFETK.'^C C-r^U? VOTCG I.T TTUVIS COU:7P/ ELECTIONS: iOCG

,

Pw ii-J r

s s ;

IvliKipl* Regression E.rt.

H ifp w iic s . l Anglo

H-'h'iOg^lil-OUS f fc d liC li

Hispfrnics | Anglo ,

A is ethnic gioups

polarized? .

Do*:S HlSprliiO

choice win?

• S20 D « n P r im a ry ! : i

0 ;s i / i c t Court' / V < J .* c VES NO

Gsi:« Jo (Hispanic) .0000 03 3-1 00' r i•j %

l&Cown ‘ 7 00 14 63

Toij-J 100 1 1 100' 100 100 "

County C o u r t^ t-Z o c ,S4 1 VES NO

•iwci? (Hispw«io) .0000 Vj 33 Oij J • » ‘ •

M.::iips ; 5 07 10 63

lo lr j 100 . 100 100 100

C ounty C o u rT ^ f- /.*? vO \/cc• L *J NO

C'-.Mio iHi;p:-i^cj .0000 7 7 14 63 16

Kc.*«n*rdy (£i xclc)+Hu^hcS 23 46 '•->1 h%/i 04 1

lo it i 100 100 100 100

i •

I

• I

1 9 0 0 D em P r i m a r y

D is tr ic t Court * 3 4 5

Gall ii du (Hispanic)

McCovn

Total

County C o u rt-o t-L o v

Garcia (Hispanic)

Phillips

Total

County C o u rt-o t-L o v ■*7

Castro ( Hispanic) ,9Q

Kennedy (Black)♦Hughes ,00()0

Total y

GRQOP YOTNG IN TRAYIS C0UN1rY DISTRICT COURT ELECTIONS- f'onn

Bivariate

Pearion r

3ig

Regression Analysis

Estimates) for: •

HispanicslMon-Hispanics

1 !t

Homogeneous Precinct Fsf

90-"t 0075 j 90- 100

Hispanic | Hon-Hiananic

Ar e ethnic

groups

polarized?

Does

Hispanic

choice vln?

• 8/6

.0000

e'o

.0000

101 i 36' ■ B6 37- 1 I 64 14 63

100

oo

100 100

100 ! 36 ,90 ■r 7

0 1 64 10 63

100 : ioo 100 1 00

76 , : 16

2 d , 86 37 84

100 " 100 100 10 0

i . t

HH

YES

YE:

YES

NO

H O

NO

if,i,

y-TT“---- - . fl,

f < ."LAiNTifr'S

j: l SXH I3IT

U

PLAIN

TIFF'S

EXH

IBIT

: . , t. .1.-.. « «• «'i . ; n « > 1 I ̂| m •

ESTIMATES OF ETHNIC GITOUP VOTING IK .lEFFEnSOKCOUNTY E lE tV lfrR S 1972-1980

1972 D e m o cra tic P r in v y

•a * . r . , re t. t, r t. 2

Fre emon (Black)

MilrelUTre/r.ei.eleibold+PsInui

Toi*J

1972 D t n o c r t l i c Runoff

2 *. r ., re t. / , n . 2

freeman (Block)

Tremen

ToioJ

1974 D tn o c r a l ic Prim ary

J. «. r . , re t. 2, r t. 2

Freeman (Black)

KarrsKnowles

ToloJ

, 1974 D e m o c ra tic R unoff

J. e. r ., re t. 2, n . 2

Freeman (Block)

Knowles

Toiol

1978 D e m o c ra tic Prim ary

C e im ty C o u rt mt tee", 2 / 2

Davis' (Block)

Slles'-sManes

Toiol

1982 D e m o c ra tic Prim ary

j . e. r ., re t. t, r t. 2

Connon (Block)

hECasselltMcCoJI

Total

1986 D e m o c ra tic Prim ary

/ *. r , re t. tf rt. 2

Roberts (Block)

Robins onefvEGinnis «Davis -efvllle

Toiol

1988 D e m o c ra tic Prim ary

rneeit/ent

'•Jockson (Block)

ioreaSimon+L oRouche -tHort-rOi

Toiol

Pertialr • Regression Estitnues 1 li Homogeneous Estio'isies Are t'hnic groups polsnied? Does Week

Block Anglo Block Anplo B/A choice win?

.70 1 ; • 1

-----1-----------------1------

YES NO

70 25 : 75 26

30 75 25 74

too 100 f| 100 100

66

65

l1

39 92 40

YES NO

15 62 8 60

100 too 100 100

.75

83 26 89 ',tr a J

YES NO

17 74 11 75

100 100 100 100

.72

93 - 41 95 42

YES NO

7 59 5 50 ’

100 100 100 100

.97

e« 10 93 13

YES NO

16 90 7 87

100 100 100 100

.97

53 7 51 6

VES NO

47 93 49 94

100 100 100 100

.93

47 2 40 3

HO NO

r 53 98 60 97

100 100 100 100

.97

101 6 96 7

YES YES

ik ok is -1 94 4 93

100 100 100 100

.. A -

tO

-L

••'I.'

.1 1.

I I

j l -II. i t .‘III. i. ,I K i i-i.-r uil. | I i

ESTIMATES OFi ETHNIC G R O U P VOTING IN JEFFERSON 'COUNTY ELiECTIp^S'“l9V2-19B0

I I *' l •

i-l 1 'll

Partial r

Multiple Regression Analysis

Estimates lor:

Black

Homogeneous Precincts

90-100V. |90-100%

Black

Are elhmc

groups polarired'?

Ooos

Black

".980 Democratic Primary

P r e s i d e n t , .97

1 1 , ‘. . 1

l lit

j YES YESJackson (Block) .0000 101 6 I’ 96

< 4

7

Gore* Simon* LaRouche*Harw Dukakis-. -1 94 93 . i

Total l 100 100 'lOO ■! hoo |

,

*»

l . * ' i ' r* t f i • i

1

> 1

• j a.

1 l •. (l *1 •

i . J

*.f i'Th - . «

PLA

IN

TIFF'S

EXHIBIT

U

-O

iL

I I

?C;

‘ ■ ' •U ' ' i / ' | » • / . . .

ESTIMATES OF ETTIKIC CnOUP YOTWG IN LUDDOCK COUNTY ELECTIONS: 1986 -198$

l

i'i

i.i

Tvtihlr

1986 GenermJ Election

Supnene C t. P/. -4 .95/79

Gonceler (Hispenic)

8nes (White)

ToitJ

1988 General Election

S txpm rt* C t. P /. 3 .93/.e8

GonreJez (Hitpenic)

Howel!♦Scholr (While)

ToteJ

R*piessionEstim*(es lor

Titponict Bleck Anglo Comb.Mrj*

99

1

100

94

6

100

90

10

100

90

10

100

35

65

100

37

63

100

97

3

100

93

7

100

Hohiopeiitous Estimates

Anplp Comb.Mn.*

39 '

61

100

40

60

100

91

9

100

f-9

11

100

Are eihnic proups p o lic e d

Numbers.in these columns were derived from bivwinie enelyj «s, ell olhera from mukiveriele w .elyses.

. Comb. Mn/Anplo

VE‘

VES

Are H.sp t Blecl. p o e t C om b.M n

cohesive

VES

YES

choice v.-in?

NO

NO

muie>

l

' L

■ I • ) b.-;; i. . . j - .11 • • , ’Y i;. i c i .< .1 .

!i ' 1 1 1 •• •' I * j i i • I Hum i|n

ESTIMATES OF ETHNIC GROUP VOTNG IN LUBBOCK COUNTY GENERAL ELECTIONS: 119HB -1908

Bivariala Rpnfoction Anaiuci* n _____ •’ » _ .. — — — -------

1.1

. r i'

Pearson r

Stq,

1906 General Election

Supreme Cl. PL 4 .96

Gonzalez (Hispanic) .0000

Bales

Total

1988 General Election

S u p n m t Cl. PI. 3 .94

Gonzalez (Hispanic) .0000

HowelUScholz

Total

Bivariale Regression Analysis

Estimates lor

Anglo |Comb Mir

..i, It.

. i

Multiple Regression Analysis

Partial r-H/B Estimates lor

i ?ig H/B Anglo| Hispqnic 1 Black

1

, .9 5 /7 9 i •

' it ■ 1

35 97 .oopo/.qpoo 35 99 90 39 91

65 3 ;t'ii' 65 : t 10 61 9

100 100 100 1QQ 100 1Q0 100

.9 3 /8 8

1 Pis. •I 1 i».l

37 93 .0 0 0 0 /0 0 0 0 37 9 4 ' 90 40 89

63 7 i*j. . ■ >. 63 § 10 60 1)100 100 (0 0 100 100 1()0 100

. i . i

1 •• . i 1 J .

1 ■{K>. . > J

» • 4.

Homogeneous Precincti

90-100% I 80-100%

Anglo | Comb Min

Are ethnic

groups polarized?

Comb. Mm/Anglo

Are Hisp

A Black

cohesive?

Does

Comb. Min.

choice win?

YES

YES

YES

YES

NO

NO

- A -

I )

ESTIMATES OF ETHNIC GROUP VOTNG IN

1986 Ocm Primary

Cl. Ciim. App. PL 1

Martina/ (Hispanic)

DiaUDuncan+Reagan

Total

S u p rtm * Cl. PI. 4

Gonzalaz (Hispanic)

Ivy+GibsontHumphreys

Total

1986 Dam Runoll

S u p rtm t Cl. PI. 4

Gonzalaz (Hispanic)

Gibson

Total

Cl. C r/m . App. PI. |

Martinez (Hispanic)

Duncan

Total

J; I! i . t ii> ' I i I I -ir IVI

•! . . I . I.. ,1.1

. 11! ! . j ■ ii. :.

LUBBOCK COUNTlI PRIMARY

I II

I

Bivariate Regression Analysis

Pearson r| Estimates lor

Siq. | Anglo |Comb. Mir

Multi

Partial r- H/B

Siq.'H/B::

>le Regression Analysis

Estimates lor

Anqlo| Hispanic | Black

Homogeneous Precinct*

90-100% I 80-100%

Anglo | Comb. Mm.

Are ethnic

groups polarized?

Comb. Min/Anqlo

Are Hisp.

& Black

cohesive?

Does

Comb Mm.

choice win?

.97

16

.98 /80

1

l f .. t 1 YES YES YES.0000 98 .0000/.0000 15 108 61 22 79

84 2 85 •a 39 78 21

100 100 100 10(j 100 100 100

.93

36

.9 5 /56 YES YES NO

.0000 97 .0000 /0015 35 106 86 41 89

64 3 65 -6 14 59 11

100 100 100 100 100 100 100

.87

36

.7 8 /66 YES YES YES.0000 97 .0000 /0002 36 97 96 46 94

64 3 64 3 4 54 6

.93

100 100 100 100 100 100 100

24

.8B/.77 YES YES NO

.0000 103 0000 /0000 24 105 98 32 95

76 -3 76 -5 2 68 5

100 100 100 1001 100 100 100

- 3 r

1 *•'

II •'

i.H •

» r

; ii

] i . .

• i.

■’O K : . I I : .

I’m • i k ;

, i i i

i. ;.l> M .

. I

I. .

ESTIMATES OF ETHNIC GROUP VOTNG IN ECTOR C O U \’TY PRIMARY ELECTIONS: 1986

Btvariale Regression Analysis

Pearson r| Estimates lor

Sin- 1 Anqlo |Comb. Min

Multi

Partial r- M/B

Siq -H/B

>le Regression Analysis

Estimates lor

Angloj Hispanic | Black

Homogeneous Precinct:

90 1007. 1 80 1007.

Anglo 1 Comb Min

Are ethnic

groups polarized?

Comb Min/Anqlo

AreHisp

A Black

cohesivo?

Does

Comb Mm

choice win?

1986 Dem. Primary

Supreme Cl. PI. 4 .80 .46 /71 YES NO NO

Gonzalez (Hispanic) .0000 11 53 03 8 1 /0 0 0 2 13 42 65 14 50

Ivy .Gibson*Humphreys 89 47 87 58 35 86 50

Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

Cl. Cilm. App. PI. 1 .78 .5 0 /6 2 YES YES YES

Marline/ (Hispanic) .0000 15 74 .0178 /0019 15 68 81 19 68

DiaU Duncan* Reagan 85 2t> ' 85 32 ‘‘ 19 81 32

Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

I I i

* ■.

I

•i l

( I.

m

;■ . i ' • . i : l* ‘ • j ;;l ■ i 'i n i ,

- i • : Irj • } | '• • • • -I.- I

. i : i i , •. i.

ESTIMATES OF ETHNIC GROUP VOTN(a IN MIDLAND COUNTY ELECTIONS: 1986

Bivariate Regression Analysis Homogeneous Precinct Esl ' Are ethnic Does

Pearson | Estimates lor;. 90-100% 90-100% groups Comb Min.

Siq. Ahqlo | i Comb Min. Anqlo •Comb Min. . polarized? choice win?

1986 General Election

Supreme Cl. PI. 4 ' .96

j i 1i1

1. 1 |i

YES ND

Gonzalez (Hispanic) .0000 25 , 9Q 132 89 I

Bales 75 1 0 '68 1 1

Tolal 100 100 1 po 1 00

1986 General Election

JP PI 1 .96 YES hO

Walson (Black) .0000 .1 9 9 1 l 26 90

Jobe. 81 ■ |9 7.4 , 1 6 ., 1

Tolal 100 100 1 00 1 00

1988 General Election

Supreme Cl. PI. 3 .89

I

YES ND

Gonzalez .0006 34 85 37 9 1

HowelUScholz 66 1 5 63 9

Tolal 100 1 00 1 00 1 00

1 *1 ~ O VL

*c

o

ES1IMATES O F ETHNIC GnOUP VOTHG IH M ID LA N D COUNTY ELECTIONS: 190 6 -1 9 8 8

Begitsrion Analysij

P t ir s o i. i l E i'im t-lis for

Sin. | Anglo ICoir.b M i.

M iliipb i Rcgiession Analysis

f *>ti>jr-H'B| i E s t im iit r loi

Sig -H‘B | Alible. | Hispsr.io | EjIk I;

Hoiiiog-ni

90-100a

Anglo

OUS Piet IfiCIS

I 60-100 *>

| Cofi'ib. M il.

Are ethnic

groups polarize!?

Comb l»1n?Anglo

An Hisp

8-Blsck

cohesive?

Does

Comb. Mn.

choice will?

198b G e n tru Election

SvpneMte Ct. FI. 4 96 .86? 99 ! YES YES NO

Gooi h itr (Hispanic) .0000 24 •41) .0000? 0000 ! 24 106 78 23 86

BWfcj 76 19 76 -5 2> 72 15

TolfcJ 109 100 1100 100 100 100 100

198b General Election i * i

j f f i t .96 87/81 i: YES YES NO

VVuson (Black) .0000 17 91 0000? 0000 17 106 79 21 85

Jobe 03 9 183 -6 21 79 15

loiaj 100 100 1100 100 luO 100 100

1988 General Election

S u p rerte Ct. FI. J 96 84/.32 YES YES NO

Gonit-ltr .0000 34 91 0000/ 0000 34 99 06 37 86

Hovscll+Sclidz 66 9 66 1 14 63 14

JoiaJ 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

i

I

) r'

APPENDIX "B

Plaintiffs' Re-Evaluation of

Defendants' Statistical Analysis

DALLAS COUNTY

PLAINTIFFS' RE-EVALUATION OF DR. TAEBEL'S REPORTS

Page # of

Taebel

Exhibit -

Judicial

Year

Elections

Did Whites & Blacks

Race - - Vote. Differently?

With Black Candidates:

Did BlackChoice

Win?

General Elections:

District Court:

.1 1980 191st Dist Ct Yes No

21 1984 Cr. Dist. 2 Yes No

37 " 1984 - 301st Dist Ct Yes No

69 - - - 1986 256th Dist Ct Yes No

73 1984 195th Dist Ct. Yes No

89 1988 95th Dist Ct Yes No

County: court at Law: r ; • ----- -

17 1982 £0 .. Cr.. 6 Yes NO

Justice-.of--the Peace: Courtr:iJone

Appellate. Court : Hone .•=

Primary Elections:

District Court:

81 1988 ..Cr. Dist 2 [RP] No -- Yes

County Court at Law: - ...... ;.

*13 1982 Co. Cr. 6 [RP] Yes No

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court: None

1

Judicial Elections Without Black Candidates:

General Elections:

District Court:

5 1980 95th Dist Ct Yes No

9 1982 191st Dist Ct Yes No

25 1984 Cr. Dist 3 Yes No

33 1984 162nd Dist ct Yes No

77 1986 298tg Dist ct Yes.... No

County Court at Law:

Justice of the-.Peace'Court: None ' '

Appellate-Court:

65 i. ,6— 1986.-__ S-Ct. 4 Yes . . -- No

85 1988 S Ct 3 Yes Yes

Primary Elections:

District Court: None

County -Court Cat rLawreNone

Justice of the :Peace Court: None

Appellate Court •

•

29 1984 Ct Cr App [DP] Yes No

41 1986 S. Ct. 4 [DP] Yes Yes

45 1986 Ct Cr App [DP] Yes Yes

4 9 1986 S Ct. 4 [DP-RO] No Yes

53 1986 Ct Cr Ap[DP-RO] Yes Yes

Non-Judicial Elections With Black Candidates: None

2

Non-Judicial Elections Without Black Candidates:

57 1986 Lt Gov Yes Yes

61 1986 Atty Gen Yes No

Judicial Elections with Black Candidates

JudicialElections without Black Candidates

Non-Judicial

Elections with Black Candidates

» Non-Judicial

Elections without Black Candidates

SCORECARD

Whites/Blacks BlackVote Differently Choice Win

8 of 9 1 o f 9

i r o f 12 5 of 12-

r _ a. a t a\ 0 of 0 .- - -

2 of 2 1 of 2

3

BEXAR COUNTY

Page f of Did Whites Did Hisp

Taebel & Hisps. ChoiceExhibit . Year Race ... .Vote .Differently? win?

Judicial Elections With Hisp. Candidates:

General Elections:

PLAINTIFFS' RE-EVALUATION OF DR. TAEBEL'S REPORTS

District Court: -- ... -- - r:~

5 1980 187st Dist Ct Yes ‘ Yes

15 1982 144th Dist Ct Yes No

16 1982 290th Dist Ct Yes No

18 1984 . 37th Dist.Ct Yes. No

19 1986 . 285th Dist .Ct.. Yes. No

25 1988 73rd Dist Ct Yes No

26 1988 '225th Dist Ct Yes No

County Court'at Law:

20 1986 •

4JUOU "Yes No

27 ' 1988 Co. C t 2 ' ~y I k Yes

Justice of the Peace'Court: None "- .

Appellate Court:

4 1980 Ct App Yes Yes

28 1988 Ct App Yes NO

Primary

District

2

Elections:

Court:

... 1980 131 Dist-Ct[DP] Yes No

3 , 198 0 187 Dist Ct[DP] Yes No

1

7 1982 285 Dist Ct[DP] Yes No

9 1982 285 Dist Ct[DP] Yes Yes

10 1982 288 Dist Ct[DP] Yes Yes

11 1982 289 Dist Ct[DP] Yes No

12 1982 290 Dist Ct[DP] Yes Yes

17 1984 37 1Dist Ct [DP] Yes Yes

22 1986 150 Dist Ct[RP] Yes No

1980 187 Dist Ct[DP] No No

1980 131 Dist Ct[DP] Yes No

County Court at Lawj . , x » • . i •

13 1982 Co. Cr. 3 [DP] Yes No

14 1982 Co. Ct. 4 [DP] Yes No

23 1988 Co. Ct. 2 [DP] Yes Yes

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court.:

1 . 1980 Ct App [DP] Yes— . — _ ?es

6 .... 1382 Ct App [DP-RO] Yes No

8 L - 1~9 8 2 jCt. App [DP] Yes - - No

24 .1988 Ct App [DP] Yes No

Judicial Elections Without Hisp. Candidates:

General Elections: :

District .Court:

County Court at Law:

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate Court:

2

District Court:

County Court at Law:

21 1986 Co. Ct. 5 [DP] Yes Yes

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate Court: ___

Kon-Judicial Elections With Hisp. Candidates: None

Non-Judicial Elections Without Hisp. Candidates: None

Primary Elections:

Judicial Elections with Hisp. Candidates

JudicialElections without

Hisp. Candidates

Non-Judicial Elections with

Hisp. Candidates

Non-Judicial

Elections without

Hisp. Candidates

SCORECARD

Whites/Hisps. Vote Differently

28 O f 2 9

1 O f 1

- 0 o f 0 —

0 of 0

Hisp.

Choice Win

9 of 29

1 of 1

0 of 0

0 of 0

3

PLAINTIFFS1 RE-EVALUATION OF DR. TAEBEL'S REPORTS

TARRANT COUNTY

Page # of

TaebelExhibit

Judicial

Did Whites

& BlacksYear Race Vote Differently?

Elections With Black Candidates:

Did Black

ChoiceWin?

General Elections:

District Court:

29 1986 Cr. Dist . _ 1 Yes No

33 1986 Cr. Dist . 4 Yes Yes

57 1988 Cr. Dist . 2 Yes No

County Court at Law: None

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court:: None --- . . . --------- —

Primary "Elections:-

District Court: None

County-Court at Law:" :

1 - 1982 -^Co. Cr. 1 I DP] Yes . No

37 ■ 1986 - Co. Cr. 6 TDP] Yes No

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court: None

Judicial Elections Without Black Candidates:

General Elections:----- .....

District Court:

13 1982 233rd Dist Ct Yes Yes

1

17 1982 297th Dist Ct Yes Yes

21 1986 233rd Dist Ct Yes No

25 1986 325th Dist Ct Yes Yes

61 1988 17th Dist Ct Yes No

County Court at Lav:

9 1982 Co. Cr. 4 Yes Yes

Justice of the Peace Court: None - ■ -

Appellate Court:

49 198 6 S. Ct. 4 Yes Yes

65 198 8 S. Ct. 3 Yes Yes

Primary Elections:

District Court: None __ _

Countv Court at Law:

5 1982 Co. Cr. 4 [DP]t Yes Yes

Justice of the Peace Court: None -

Appellate Court:

41 1986 Ct.Cr.App. [DP] Yes Yes

49 1986 S. Ct. 4 [DP] Yes Yes

Non-Judicial Elections With Black Candidates: None

Non-Judicial Elections Without Black Candidates:

'45 1986 Atty Gen Yes No

2

Judicial Elections with

Black Candidates

SCORECARD

Whites/Blacks Black

Vote Differently Choice Win

5 of 5 1 of 5

Judicial

Elections withoutBlack Candidates .— l_. li of 11 8 of 11

Non-Judicial

Elections with Black Candidates 0 of 0 0 of 0

Non-Judicial" — _ .

Elections without

Black Candidates 1 of 1 0 of 1

3

PLAINTIFFS1 RE-EVALUATION OF DR. TAEBFL'S REPORTS

TRAVIS COUNTY

Page # of Did Whites Did Hisp

Taebel . . . & Hisps. ChoiceExhibit Year Race Vote Differently? Win?

Judicial Elections With Hisp. Candidates;

General Elections:

District Court:

County Court at Law:

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate 'Court:

29 1986 S Ct 4 No Yes

45 1988 S Ct 3 • • No Yes

Primary Elections:

District Court: . - . - -

- - -

37 1988 345 Di'St £t{DP] Yes No

- - “ t . v <, e rCounty Court at Lav:

33 1988 Co. Ct. 1~[DP]‘'y^s No

41 1988 Co. Ct. 7”[DP] 'Yes No

Justice of the :Peace Court:

Appellate Court :

-1 1984 Ct Cr A [DP] Yes No

9 1986 Ct cr A [DP] Yes No

21 1986 S Ct 4 [DP] No Ye-

25 1986 S Ct 4 [DP-RO] No Ye:

1

Judicial Elections Without Hisp. Candidates:

General Elections:

District'Court:

County Court at Law:

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate Court:

49 ” * "1988 "5 Ct 4 No Yes

Primary Elections:

District Court: - ---

County Court at Law:

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate -Court:_______

Non-Judicial Elections With Hisp. Candidates:

5 1984 St Sen 14 No Yes

13 1986 Atty Gen No • Yes

1984 St Sen [DP-RO] Yes Yes

1984 St Sen [DP] Yes Yes

Non-Judicial Elections Without Hiso. Candidates:

17 1986 Lt Gov No Yes

2

SCORECARD

Hisp.Choice WinWhites/Hisps.

Vote Differently

Judicial Elections withHisp. Candidates 5 of 9

JudicialElections withoutHisp. Candidates 0 of 1

Non-Judiciai Elections withHisp. Candidates 2 of 4

Non-Judicial

Elections- without-'-Hisp. Candidates 0 of 1

4 Of 9

1 Of 1

4 Of 4

1 of 1

3

PLAINTIFFS' RE-EVALUATION OF DR. TAEBEL'S REPORTS

JEFFERSON COUNTY

Page # of

TaebelExhibit Year Race

Did Whites

& BlacksVote Differently?

Did Black

ChoiceWin?

Judicial Elections With Black Candidates:

General Elections:

District Court: None

County Court at Law: None

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court: None

Primary Elections: r'~

District Court: None

County...Court at Law: N o n e _______ ... _________

Justice -of t h e Peace Court: None

Appellate Court: None

Judicial Elections Without Black Candidates: "r.v-.

General Elections:

District Court: None

County Court at Law: None

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court:

10 1986 S. Ct. 1 No Yes

17 . ,--1986 _ S. Ct. # 4 No Yes

1

District Court: None

County Court at Law: None

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court:

Primary Elections:

7 1986 Ct.Cr.App. [DP] Yes No

13 1986 S. Ct. 4 [DP] Yes Yes

Non-Judicial Elections With Black Candidates:

1 .. -1982- St.Rep 22 Yes Yes

4 : - - -198 4 "• -"■St:Rep 22 ” :iYes Yes

Non-Judicial Elections Without Black Candidates:

19 1986 Gov. Yes Yes

22 1986 Atty Gen NO Yes

SCORECARD

Whites/Blacks BlackVote:Oifferently Choice Win

Judicial... ^

Elections withBlack Candidates ____ .. 0 of 0 . 0 of 0

JudicialElections withoutBlack Candidates 2 of 4 3 of 4

Non-Judici’al~'Elections withBlack Candidates 2 of 2 2 of 2

Non-Judicial

Elections withoutBlack Candidates - 1 of 2 -- 2 of 2

2

PLAINTIFFS' RE-EVALUATION OF DR. TAEBEL'S REPORTS

LUBBOCK COUNTY

Page # of

Taebel

Exhibit Year Race

Did Whites

6 Minorities Vote Differently?

Did MinorityChoiceWin?

Judicial Elections With Minority Candidates

General Elections:' ' ”‘

District Court: None

County Court at Law: None

Justiceof the Peace Court:. None

Appellate Court:

17 1986 S. Ct. # 4 Yes

25 ~19'88' S . Cfc. # 3*' *" ' Yes

Primary Elections: _ ' ' _ _ _ Z Z Z

District Court: None

County Court at Law: None r-.

Justice of the Peace Court: None ic 3,

V rv .-.r TV

Appellate Court: None

No

No

Judicial Elections Without Minority Candidates:

General-Elections:

District Court:-None - - -- ■

County,.Court at Law:

1 • - * 1 9 8 2 ' • o U Ct. 1 Yes No

9 " "'1986 Co. Ct. 2 Yes No

1

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court:

2 1 1988 Ct. Cr. App. Yes No

Primary Elections: •

District Court: None

County Court at Lav:

1 ^1982~ ' Co. Ct. 1 [DP] No Yes

Justice of the Peace Court: None

Appellate Court: None

Non-Judicial-Elections With Minority Candidates:

1 3 1986 Atty Gen Yes No

Non-Judicial Elections Without Minority Candidates: None

SCORECARD

Whites/Minorities Minority

Vote Differently Choice Win

Judicialr----- . Elections with Minority Candidates

JudicialElections without

Minority Candidates

Non-Judicial

Elections with Minority Candidates

Non-Judicial

Elections without Minority Candidates

2 of 2

3 Of 4

1 of 1

0 Of 0

0 of 2

1 Of 4

0 of 1

0 of 0

2

PLAINTIFFS1 RE-EVALUATION OF DR. TAEBEL'S REPORTS

ECTOR COUNTY

Page # of Did Whites Did MinorityTaebel & Minorities Choice

Exhibit Year Race Vote Differently? Win?

Judicial Elections With Minority Candidates;

General Elections:

District Court:

County'Court at Law:

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate Court:

21 1986 S Ct 4 Yes No

37 1988 S Ct 3 Yes No

Primary Elections:

District Court: --

County Court at Law:

Justice of—“the Peace Court:-----------

Appellate Court:

Judicial Elections Without Minority Candidates:

General Elections:

District Court:

.5 1980 161 Dist Ct Yes No

County Court at Law:

9 1982 Co Jud No Yes

13 1982 Co Ct Law No Yes

1

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate Court:

29 1988 S Ct 4 Yes No

33 1988 Ct App Yes No

Primary Elections:

District Court:

County Court at Law:

Justice of-the-Peace--Court:

Appellate Court:

Non-Judicial Elections With Minority Candidates:

17 1986 Atty Gen Yes No

Non-Judicial Elections Without Minority Candidates:

1 1980 RR Com Yes No

25 1986 Lt Gov Yes No

2

SCORECARD

Whites/Minorities

Vote Differently Minority

Choice Win

Judicial Elections with Minority Candidates . 2 Of. 2 0 of .2

JudicialElections without Minority Candidates 3 Of 5 2 of 5

Non-Judicial Elections with * Minority Candidates 1 of 1 0 of 1

Non-Judicial

Elections without - -- Minority Candidates 2 of 2 0 O f 2

. ? . - . v w . ' 1

3

PLAINTIFFS' RE-EVALUATION OF DR. TAEBEL'S REPORTS

MIDLAND COUNTY

Page I of

Taebel

Exhibit Year Race

Did Whites ---

& Minorities Vote Differently?

Did MinorityChoiceWin?

Judicial Elections With Minority Candidates:

General Elections:

District Court:

County Court at Law:

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate Court:

25 1986 S Ct 4 Yes ... No

29 1988 S Ct 3 Yes No

Primary Elections:

District Court: -------- ----

County Court-^ t Law:

Justice of the Peace Court:

Appellate Court:

9 1986 Ct Cr App [DP] “No"-. ;r- No

21 1986 S Ct 4 [DP] 'No ' - - — = -=No

Judicial Elections Without Minority Candidates:

General Elections:

District Court: -

1 1980 142 Dist Ct No Yes

County Court at Law: ~ •

1