Shields v Midtown Bowling Lanes Transcript

Public Court Documents

October 29, 1965

324 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shields v Midtown Bowling Lanes Transcript, 1965. 58ddfc35-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bb7c4e4f-aeab-47fc-a20c-6f533f5d569e/shields-v-midtown-bowling-lanes-transcript. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

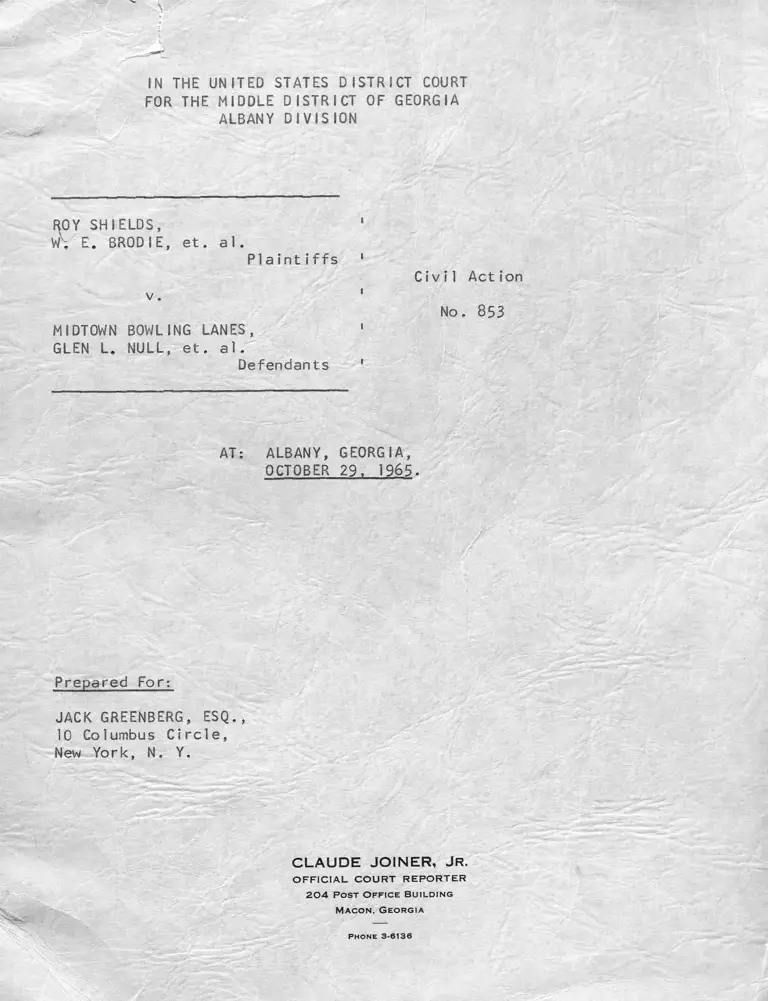

IN THE UNITED STATES D ISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ALBANY DIVISION

ROY SHIELDS, '

W; E . BRODIE, e t . a l .

P l a i n t ! f f s 1

C i v i l Act ion

v. 1

No. 853

MIDTOWN BOWLING LANES, '

GLEN L, NULL, e t . a l .

Defendants 1

AT: ALBANY, GEORGIA,

OCTOBER 29, 1965.

Prepared For:

JACK GREENBERG, ESQ.,

10 Columbus C i r c l e ,

New York, N. Y.

C L A U D E JO IN E R , JR.

O F F IC IA L C O U R T R E PO R TE R

2 0 4 P o st O ffic e Bu il d in g

Ma c o n , G e orgia

P h o n e 3 -6136

INDEX TO PROCEEDINGS

WITNESS or PROCEEDING

Preltm tnary

PLAINTIFF DEfENDAN'

GLEN L . NULL 7 256

284 301

299

302

DAVID M. MOORE 45 55

CHARLES E. WILLIAMS 56 68

310

MRS. LINDA WEINTRAUB 72 78

LAWRENCE WEINTRAUB 84 87

SGT. LUCIUS H. SMITH. JR. 88 102

108

312

WM. F . NOBLE 111 116

WM. EDW. BRODIE 121 125

JAMES S . PARRY 132 142

146 149

303 308

ROY SHIELDS. JR. 151 154

W. M. HUMBER 166 161

183

MRS. LORENE REBER 201 187

223 220

HOWARD HENDLY 241 228

254

GLEN L . NULL 284 256

299 301

302

A

couftl

l

302

5!

53

82

316

304

190

197

200

227

243

255

302

INDEX TO PROCEEDINGS

iigas.i-

'JEITNESS or PROCEEDING PLAINTIFF DEFENDANT COURT

JAMES S . PARRY - re ca lle d 303 308 30k

CHARLES E. WILLIAMS - re ca lle d 310

SGT. LUCIUS H. SMITH, JR. - re ca lle d 312 316

DEFENDANTS* MOTION 317

■ -

BRIEFS DUE 319

* * * * * * * * * * *

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE HIDOLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ALBANY DIVISION

ROY SHIELDS, J R ., W. E. BRODIE, '

WESLEY JONES S- WILLIAM NOBLE,

P la in t i f f * *

CtvM Action

v . 1

No. 853

MIDTOWN BOWLING LANES, *

an unincorporated a sso c ia t io n ,

GLEN L . NULL, doing business '

as Midtown Bowling Lanes,

HOWARD HENDLEY 6- JOHN DOE, •

_____________________Defendants

B e f o r _e

HONORABLE J . ROBERT ELLIOTT,

United States D is t r ic t Judge

At: Albany, Georgia,

fifrOBER 33...13&U

A p p e a r a n c e s :

For P la in t i f f s : MR. C. B. KING,

MR. DENNIS E . ROBERTS,

P. 0 . Box 102*1,

Albany, Georgia.

MR. H. P. BURT,

MR. DONALD D. RENTZ,

P. 0 . Box 525,

Albany, Georgia.

R e p o r t e d B v

CLAUDE JOINER, J R .,

O f f ic ia l Reporter, U. S . Court,

Middle D is t r ic t o f Georgia,

P. 0 . Box 9*». Macon. 6a.

1

A kBM Y^ M PM IA . S lift At, M, OCTOBER 29. 1965.

THE COURT * A ll r ig h t , we have set for hearing at

th is time C iv i l Action No. 853* Roy S h ie ld s , J r . e t . a l .

versus Midtown Bowling Lanes. I have, o f course,

reviewed the p lead ings, we've had a p r e - t r ia l conference,

I have reviewed the pleadings and the p re - t r ia l order

again ju s t before coming into the courtroom. So, I

know o f no need for any p re lim inary or opening statement

by counsel. So, un less counsel for one or both sid es

fee l that some p re lim inary statement w i l l be of some

va lu e , I suggest you proceed immediately to the c a llin g

o f your f i r s t w itn e ss , M r.King.

MR. KING: If Your Honor p le a se s , in advance

o f doljjg th a t , I n o tice th is morning that an amendment

was f i le d to the answer by the Defendants In th is

p a rt ic u la r case , and I Inquire o f opposing counsdl

whether or not Mr. Null is here. I wanted to put him

on as the f i r s t w itness for the P la in t i f f . I am advised

that he Is not here and I th ink that i t becomes very

important that I be able to do t h is .

TH£ COURT: W ell, you have your c l ie n t s here,

don't you?

MR. KING: Yes, I do but I'm thinking in terms

o f the method o f presenting the evidence.

v

MR. RENTZ: Your Honor, we talked w ith our c l ie n t ,

Mr. Null la s t night and the la s t we hear from him^fte

Prelim lnary 2

Mr. Rentz:

would be here at 8 :2 0 . I see somebody coming In rig h t

now. He was supposed to be here, four Honor. We made

a phone c a l l Just a few minutes ago, Your Honor, and he

was not at h is p lace of business and was not at hts home,

so I presume that he 's on the way.

HR. KING: I might say during the Interim , I f I

may Your Honor, that I would lik e to In th is case

Introduce Hr. Roberts to the Court and move that he

be admitted for purposes of p a rt ic ip a t in g In th is

p a rt ic u la r case .

THE COURT: A ll r ig h t , I ' l l a llow that but may I

make a suggestion, Hr. King?

Hr. King: Yes s i r .

THE COURT: Every time we have a case In th is

court we go through that routine . Why don't you get

Hr. Roberts admitted to the Bar o f the S tate of Georgia,

so that he can go on and p ra c tice law without going

through th is routine every time? Why don't you have

himeimltted to the Bar; so he w i l l then be e l ig ib le for

admission to p ra c tice in th is Court. I f he 's going to

l iv e here and be associated w ith you a l l o f the time,

whydon't you go ahead and do th a t, so we won't have

to go through that routine? I t ' s a l l r ig h t w ith me to

go through the routine everytlme but I t seems to me to b®

PrelIm lnary 3

The Court:

rather se n se le ss , when a l l he's got to do to become a

member o f the Bar o f th is Court Is to become a memberf

o f the Bar of Georgia and then make a p p lica tio n .

HR. KING: I might Ind icate to the Court that

th is Is what he in d ica tes that he contemplates. Of

course , he hasn't been here much over a year, as Your

Honor knows.

I might Ind icate to the Court whfile w e're w a itin g ,

Your Honor, that I have present here one w itn e ss , whom

I assume I should advise the Court Is in the courtroom.

I a n t ic ip a te , s i r , that other w itnesses w i l l be here

during the proceeding o f th is t r i a l . I might give

th e ir names to the Court, If the Court requires I t .

THE COURT: Is e ith e r side going to ask for the

ru le to be Invoked?

MR. BURT: Yes, Your Honor, we would lik e to

Invoke the ru le .

THE COURT: A l I r lg h t , le t ' s have both s id es c a l l

the names of a l l w itnesses so that everybody w i l l be

advised.

MR. KING: I f Your Honor p leases , the P la in t i f f s

propose to use the follow ing w itnesses In the presentation

o f th e ir case : Mr. and Mrs. W elntraubs, Mr. C h arlie

W illiam s, Mr. Jim P arry , Mr. Dave Moore, Sgt. Smith.

Preliminary

Mr. King:

I b e lieve those are a l l . asid e from the P la in t i f f s

them selves, Your Honor.

MR. RENTZ: Your Honor, the only w itnesses that

we plan to use , other than Hr. Null and Mr. Hendly, who

are defendants In the case , Is Mr. B i l l y Humber and Mrs.

Reber at th is tim e, Your Honor. I be lieve Mr. Humber

Is In court aid Mr. Hendly and Mr. Null are here.

THE COURT: A ll r ig h t , now a l l w itnesses in the

case w il l remain outside u n t il your names are c a lle d .

That w i l l not apply to you, Mr. Humber; you're an

o f f ic e r of the Court and we have to have you here.

MR. BURT: Your Honor p lease , I no tice the l i s t

o f w itnesses that he 's ju s t stated for the P la in t i f f

and I be lieve a l l but one of them riere never indicated

on the answer tothe in te rro g a to rie s . Our 5$h interroga

tory says "State names, addresses, occupation, jo b , t i t l e

or capacity o f any persons who you believe have knowledge

or information pertain ing to the circum stances of the

Incidents alleged In the oomplalnt; s ta te insofar as

you know the nature o f such knowledge or inform ation";

and In h u rrie d ly looking through, I don't be lieve that

the f i r s t four names that he Just read out were answered

o r given to us iatdour In te rro g a to r le s were deemed to be

continuing.

k

Preliminary 5

THE COURT: Why was th a t, H r.K ing? Why d id n 't

ytu t e l l them about these people?

MR. KING: I may ind icate to the Court that

most o f the names that I be lieve that we have were

discovered as a re su lt of d iscovery proceedings in it ia te d

by the P la in t i f f s them selves, when they took the deposi

tion of one o f the Defendants, more s p e c i f ic a l ly , Hr.

N u ll, i be lieve that he indicated that Mr. W illiam s

was h is employee and i be lieve in the second instance.

Your Honor, that the w itnesses or the other w itnesses

have nothing to do with what is a lleged in the complaint,

the instances alleged In the complaint.

MR. RENTZ: Your Honor, I f they don't have any

thing to do with the instances a lleged in the com plaint,

1 wonder why they are being ca lle d as w itn esses.

THE COURT: W e ll, we w i l l Just have to evaluate

each w itness as he appears. Now, I don't want to get

into any h assle during the course o f the t r ia l of the

case about whether any w itness has been In the courtroom

during the t r ia l of the case . I'm n o tify in g counsel

for both s id es th a t, I f i t appears when a w itness has

been put on the stand that the w itness has been in the

courtroom during the t r i a l of the case , I'm not going

to allow the w itness to t e s t i f y . I'm n o tify in g counsel

for both s id es to that e f fe c t . New, i t ' s up to you to

Preltm lnary 6

The Court:

keep your w itnesses out o f the courtroom. I don't know

who the w itnesses are and the Marshal doesn't know who

the w itnesses are and, I f It appears that any w itness

has been In the courtroom, I don't care whether you

d id n 't a n t ic ip a te -- Mr. King, are you lis te n in g to me?

MR. KING: I apologize to the Court.

THE COURT: A ll r ig h t , you should. I'm addressing

you.

MR. KING: I'm very , very so rry , Your Honor.

THE COURT: If i t appears during the course of

the t r ia l o f the case that any w itness has been In the

courtroom, It doesn't make any d iffe ren ce to the Court

whether It was not an tic ip ated that the w itness would

be used, I f he 's been In the courtroom, he 's not going

to be allowed to t e s t if y during the t r ia l of the case .

We've run Into th is every once in a w h ile In these cases

and 1 don't want there to be any question about I t .

A ll r ig h t , c a l l your f i r s t w itn ess, Mr. King.

MR. RENTZ: Your Honor, we have Mr. Hendley and

Mr. Null at the ta b le , who are p a rt ie s to the case.

THE COURT: A ll r ig h t .

MR. KING: I f Your Honorpleases, the P la in t i f f

c a l ls Mr. N u ll.

GLEN L. NULL 7

party Defendant, ca lle d as adverse party

by P la in t i f f , being duly sworn, t e s t if ie d

CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. KING:

Q Mr. N u ll, would you sta te your f u l l name for the

record, plftese s i r ?

A Glen L. N u ll.

Q You are the owner or p roprietor o f the Midtown

Bowling Lanes, is that co rre c t , s i r ?

A T h at's r ig h t , s i r .

Q And where is that located, s i r ?

A 1200 West Broad.

Q That Is in Albany, Georgia, I b e lieve?

A Albany, Georgia.

VL- ' -'T'1 * -

Q Now Mr. N u ll, how long have you been in business

there?

A At that location I'v e been there s in ce August *42.

Q Since August o f '42?

A Yes.

Q Then, you were there during the e a r ly spring o f 196$,

Is n 't that true?

A T h at's r ig h t .

Q I c a l l your a tte n tio n , s i r , to the date A pril 25,

1965 and ask you whether or not you have any independent

re c o lle c t io n o f that date?

A I do.

Null - adverse 8

Q You do? Th is was the o ccasio n , was it not, when

persons e th n ic a lly Id en tified as Negro presented themselves

for purposes of bowling at your lanes and were refused ,

Is n 't th is true?

A They were refused for the reason that the lanes

were taken up by an a sso c ia tio n .

Q The lanes were taken up by an a sso c ia tio n ; what

a sso c ia tio n ?

A Ladies Albany Bowling A sso cia tio n .

Q The Ladies Albany Bowling A sso ciatio n?

A Yes.

Q Now, when you say that they were taken up, is

th is what you to ld them when they presented themselves?

A They d id n 't present themselves to me at a l l .

Q Oh, I see. Then, you don't have any independent

or personal re co lle c t io n o f th is occurrence, do you?

A Only what 1 was to ld afterw ards.

Q By whom and what were you to ld ?

A Mr. Hendly to ld me he had some v is i t o r s .

Q He had some v is i t o r s ?

A R ight.

Q What e lse did he te l 1 you?

A That was I t .

Q That he had some v is i t o r s ?

A Yes.

Null - adverse

Q And he ch aracterized these v is i t o r s e th n ic a lly ,

d id n 't he?

A I d id n 't understand the question.

Q I say , he ch aracterized the v is i t o r s to which he

made referene e th n ic a lly , d id he not?

A He ju s t sa id he had some v is i t o r s ; th a t 's a l l .

Q I see. W ell, Is n 't that a b it odd that he would

mention to you that he had v is i t o r s ?

A No.

Q In other words, every time some person who is not

a member of an asso cia tio n comes into your bowling lan es,

th is announcement is made?

A It could be made on account of the Ladles AssocIa

t lo n , because they had the a lle y s reserved for that date.

Q I see. Now, what time was th is that you were

advised by Mr. Hendly?

A That was In the evening.

Q In the evening?

A Yes.

Q How long had they reserved the lanes?

A A ll day.

Q A ll day?

A And a l l n ig ht.

Q A ll day and a l l n ight?

A U n til about 11 o 'c lo c k , I guess, was about th e ir

la s t schedule.

Null - adverse 10

Q I see. As a matter o f fa c t , when Negroes present

themselves at the Mfdtown Bowling Lanes, a l l o f the lanes are

reserved , are they not, th ey 're autom atica lly reserved, are

they not?

A When Negroes present themselves?

Q Yes, for purposes o f playing or bowling at your

lanes?

A No, Negroes have bowled there.

Q Yes, and the only circum stances under which

Negroes have been permitted to bowl there Is that It has

balm an a sso c ia t io n , an a sso c ia tio n sponsored a c t iv it y ;

is n 't that true?

A R ight.

Q Where you r e a l ly don't have any contro l over ( t ,

Is n 't that true?

A Control over the asso c ia tio n ?

Q Control over the e th n ic id e n tify o f the persons

who p lay or bowl In asso c ia tio n a c t iv it y ?

A W e ll, once they take o ver, I do not bother them

at a l l .

Q R ight; as a m atterof f a c t , they take over and

those are the only circum stances under which you have had

an occasion to observe and knowing o f a Negro bowling in

your bowling lan es, is n 't that true?

A No

Null - adverse 11

Q A ll r ig h t ; then, asid e from the re la tio n sh ip that

you've estab lish ed between yo u rse lf and Or. Turner, the

p s y c h ia t r is t , you say that there are p atien ts o f h is -

A T h at's co rre ct.

Q - that you turn the lanes over to him for there-

p eu tic values that are derived to h is p a tie n ts ; is n 't that

true?

A We allow them to bowl w ith th e ir p a tie n ts , r ig h t .

Q R ig h t, and I say that th is is a sort of re la t io n

ship estab lished between yo u rse lf and th e Doctor and he is

using theu bowling lanes for therapeutic purposes; is n 't

that true?

A T h at's tru e .

Q And that is the only other circumstanos under which

you have ever seen a Negro and you've known of a Negro

bowling in your bowling lanes?

A T h at's r ig h t.

Q Now, t e l l u s , Mr. N u ll, how many lanes do you

have in Midtown Bowling Lanes?

A How many names?

Q Lanes, s i r ?

A Oh, lanes? 2k.

Q 2k\ i t ' s a rather large bowling a l le y , is It not?

A I t ' s the largest In Albany.

Q W ell, as a matter o f f a c t , I t ' s about the larg est

Null - adverse 12

In the perim eter o f about 80 to 100 m iles o f Albany, Is n 't

that true?

A They have larger ones In A tlan ta , Columbus and Macon.

Q V/e 11, do you know the d istance - I would simply ask

the Court to take Ju d ic ia l n o tice o f the d istan ces o f Macon

from Albany, Columbus from Albany and A tlan ta , a l l being

more than 80 m iles c e r ta in ly from Albany. I sh a ll move

the Court to take Ju d ic ia l n o tice o f th a t, s i r .

THE COURTt W ell, I don't know whether I can or

not. I know how fa r Colujmbus Is but 1 don't know how

fa r the others a re . I know Columbus Is 90 m iles but I

don't know how fa r Macon Is and I don't know how far

Atlanta I s . I know A tlanta Is fa rth er from Albany than

Columbus Is and that would be more than 90 m ile s , but Im

not sure about Macon because I'v e never made that t r ip

as I r e c a l l .

_______ & Mr, King: You know how far Macon i s from here,

don't you, s i r ?

THE COURT: Oh w e ll , how v it a l Is that an^tay as

to how fa r Maoon Is? I ' l l presume I t ' s more than 80

m iles.

MR. KING: A ll r ig h t , s i r .

Q T h is Is a f a c i l i t y that Is sanctioned by the

American Bowling Congress, ts it not?

A R ight.

Null - adverse 13

Q Now, you have q u ite a number o f servicemen and

se rv ice personnel that are holders o f American Bowling

Congress membership card s, Is that co rrect?

A I don't have them. The A ssociation might have them.

I don't know nothing about th a t.

Q Oh, you don't know anything about It but you do

know that there are q u ite a number o f m ilita ry people who

use your f a c i l i t i e s , Is n 't that true?

A Not over 10 per cent.

Q Not over 10 per cen t, I see. Now, based on your

p rio r testim ony, Hr. N u ll, that Is w ith reference to the

only or the admitted only two conditions under which you

have had Negroes bowl in your lan es, what you're saying,

s i r , Is it not, Is that Negroes who present them selves,

not f a l l in g w ith in these two c la sse s are not permitted to

bowl; is n 't that true?

V .'V ;

A I have never been approached that I know of

outsid e o f these cases that you mentioned.

Q In other words, these are p e cu lia r? You sa id

outside o f these cases that I mentioned?

A R ight.

Q Now, what cases doyou make reference to?

A The date you were speaking o f?

Q Yes; in other words, you've read the complaint

against you and o th ers , haven't you?

Null - adverse lif

A Yes s i r , I have.

Q And when you say "these cases" you make reference

to a l l o f the Instances that are referred to In the complaint

Is that what you're ta lk in g about?

A These two Incidents of A pril and Hay.

Q R ig h t, w ith in the complaint?

A R ight.

Q In other words, these are p ecu lia r and Iso lated

Instances; Is that what you're saying?

A T h at's the words you put to I t . I don't know

whether th e re 's anything p e cu lia r about It or not.

Q In other words, any Negro presenting him self at

th is juncture may bowl at your lane, who Is otherwise

q u a lIf led?

A No.

MR. BURTi Now, I f Your Honor p lease , as I under

stand the question . I f a Negro presents h im self now; is

that the question or on these cases?

MR. KING: I d id n 't pronounce the word N-e-g-r-o

q u ite as you d id , s i r .

THE COURT: Mr. King, le t ' s don't s ta r t the t r ia l

of the case w ith that sort o f argument. We've had enough

o f th a t, In the other t r i a l . L e t 's don't get o ff Into

that morass again. L e t 's t ry th is case without a lo t o f

side Issues If we can. le t 's Just t ry the law su it.

Nu11 - adverse 15

THE COURT: Read that la s t question , w i l l you,

Mr. Jo iner?

THE REPORTER: "In other words, any Negro presenting

him self at th is Juncture may bowl at your lanes who Is

otherwise q u a lif ie d ?"

THE COURT: "At t h is juncture?" I Interpret

that to mean at th is time. A ll r ig h t , w hat's the answer

to that question?

_______ A The W itness: I w ouldn't say that they cou ld , no.

We haven't had any bowl th ere , so I don't see why we should

so long as th is - as long as I know, they haven't bowled

there and we haven't been presented -

_______ £L M r.KInc: In other words, you -

MR. BURT: Just a minute! I f Your Honor p lease ,

I want to Interpose an o b jectio n . They have alleged

two incidents on which th ey 're pred icating th e ir com

p la in t and he Is now saying I f someone presents h im self

at th is ju n ctu re , which I assume means at th is time; and

we say that Is not a proper question for th is Court.

What he may do today and what he did on these occasions -

what they a lleg e Is what we're defending ag a in st.

THE COURT: W ell, as I In terpret h is answer, he

doesn't know what he would do u n t il the occasion arose.

That's the way I In terpret h is answer. Is that what you

mean?

ZNull - adverse 16

A The W itness: Yes, Your Honor.

_______ ft Mr. King: So, on the two occasions - w e ll , t e l l

me th is - s t r ik e that - Your p o licy p resen tly Is not that o f

allow ing Negroes to bowl, is n 't that true?

A We have no p o lic y .

Q What's that?

A We have no p o licy o f d iscrim in atio n .

Q You have no p o licy o f d iscrim in atio n ?

A We've never had one.

Q You've never had one?

A No.

Q T h is Is to say a Negro presenting h im self w i l l be

permitted to bowl, i f he 's otherw ise q u a lif ie d ?

A We ju s t don't have a p o licy saying who can bowl and

who c a n 't .

Q Oh, I see; you make i t up a r b i t r a r i ly , is that

true?

A If a man presents h im self in the rig h t manner,

they've never been re jected .

Q In a rig h t manner?

A Yes, i f he 's in condition to come into the p lace to

bowl -

Q Oh, I see.

THE COURTs Let him f in is h h is answer; le t him

f in is h h is answer.

Null - adverse 17

HR. BURT: Go ahead, Hr. N u ll, I f you want to

f in is h your answer.

A The W itness: As long as he can present him self In

a gentlemanly cond ition , h e 's allowed to bowl as far as we

have gone. I don't know anything about anything that might

be.

Q Then, It Is your p o licy or It Is the p o licy and

was a t a l l times the p o lic y ,th a t Is re levant to th is case ,

to allow anybody to bowl who presented themselves as gentlemen?

A No, we've never had any outside -

Q W e ll, ju s t answer that question; the answer to

that question Is "no"?

A No.

Q That Is not your p o licy ?

A Our p o licy has not been to cut anyone o f f . I f

they come In there and we know them, we le t them bowl.

Q If you know them, you le t them In and bowl and,

I f you don't know them, you cut them o f f , Is that rig h t?

A No, th a t 's not r ig h t .

Q W ell, which Is I t ?

A I f we know th ey 're In condition to bowl, we let

them bowl.

Q I f you know th ey 're In condition to bowl?

A R ight.

Q Now, when you say "cond itio n", Is race a condition?

Null - adverse 18

A No, I d lc h 't say “ race".

Q It I s n ' t , huh? C a llin g your attention to the

P la in t i f f s , you a re n 't suggesting that they were In no

condition to bowl at the time that they presented them selves,

are you?

A They d id n 't present themselves to me; I don't know.

Q You don't know?

A No.

Q You say that none o f them presented themselves to you?

A No.

Q There was no occasion that Negroes presented

themselves to you for bowling?

A Are you ta lk ing about these two events?

f | . % - ■ *, - ■

Q I'm ta lk in g about events taking p lace between the

time of th is action or between the dates set out in th is

p a rt ic u la r complaint against you?

A No, I was never at the counter when they came in .

Q You never were what?

A I never was at the counter when they came in .

Q I d id n 't ask you whether you were at the counter,

s i r ; I ask you c a te g o ric a lly -

A T h at's the only p lace they could req u ire or ask

for a lane, would be at the control counter.

Q Now, what you're saying is t h is , Is I t not, s i r ,

that these are the only two times that Negroes have been

Null - adverse 19

turned away?

A As fa r as I know. I don't know o f any other

occas ton.

Q And when did yju find out about these o ccasio n s,

each o f these occasions in question?

A That evening before we closed up.

Q On the p a rt ic u la r evenings which are involved?

A Yes s i r .

Q Well now, what did you mean then e a r l ie r when you

sa id that th is was not unusual for Mr. Hendly to t e l l you

that there were some v is i t o r s ; he to ld you what kind of

v i s i t o r s , d id n 't he? D idn't he?

A Yes, he said there were some Negroes.

Q Negroes? W ell, why d id n 't you say th a t, In the

f i r s t p lace , s i r ? S ir ?

A Did you ask me what kind? I d id n 't know that

you wanted It d istin g u ish ed .

Q The question was, what did he say?

THE COURT: W ell, he 's answered I t . He t e s t if ie d

to that now; so , le t ' s don't go back over I t .

_______ Mr. King: Now, c a ll in g your attention to the

evening o f the 20th, th is is May, 1965, is n 't It true that

there were a group o f Negroes who presented themselves to you

in the presence o f one of your employees?

A No s I r .

Null - adverse 20

Q At or about 9:30 P. H.7

A No s i r , not to me.

Q Now, Is n 't It tru e , Hr. N u ll, that In the bowling

lanes or the bowling a l le y that you have an eating f a c i l i t y

there?

A We have a beverage counter.

Q You have a beverage counter?

A Yes.

MR. KING: 1 would Interrupt the court for purpose

o f Ind icating that a w itness has come In . (Witness

sequestered) . . .

THE COURTS L e t 's go ahead, Mr. King) le t ' s move

along.

Q Mr. Kino: A ll r ig h t , you say that you have a

leverage counter} I c a l l your attention to some seven months

ago during A pril and May} Is n 't I t true that you had a coffee

shop?

A No, we never ca lle d It a coffee shop.

Q You never cal led It a coffee shop?

A I never set a name for It as a coffee shop.

Q W ell, I s n 't I t true that you had a sign on the

outsid e of your business?

A There was a sign out there that was there before

1 came there . I had nothing to do w ith tha t .

Q Hew long have you been at that s i t e , s i r , at the

Null - adverse 21

Midtown Bowling Lanes?

A August 1, 1962.

Q 1962?

A Yes.

Q In other words, you've been there for over three,

going on four years; Is that co rre ct?

A L i t t le over three years, r ig h t .

Q Now, when did you move the sign that says "Coffee

Shop"?

A It was taken down several months ago.

Q Yes, s in ce th is l it ig a t io n s ta rte d , w asn't I t ?

A Oh yes.

Q What's that?

A R ight.

Q But you le t It stay there for v ir t u a l ly three years

before you decided to move ( t , d id n 't you?

A I never paid any attention to It being there

because It was not my sign .

Q Oh, I see . W ell, i f th a t 's the case , the bowling

pin was not your sign e ith e r , was I t ?

A The bowling p in?

Q Yes, the large neon bowling p in?

A Yes, that belongs to the bowling a l le y .

Q That belongs to the Bowling A lley?

A Yes.

Null - adverse 22

Q W ell, wasn't th is appended to I t ?

A No s i r .

Q It c e r ta in ly Is not attached to the build ing any

more than that sign was?

A No, I t was on a post by I t s e l f ; It was.

Q R ight. W ell, so was the Coffee Shop s ig n , wasn't I t ?

A The Coffee Sign what?

Q The Coffee Shop sign was outside?

A It was on a post by ( s e lf .

Q Yes, and the bowling p in?

A Was a lso separated. They were not together.

Q And the Midtown Bowling Lanes, when you bought the

p la ce , you bought the name as w e ll , Is that r ig h t7

A That name was on the butldlng but I don't run my

business under Midtown Lanes.

Q W e ll, th a t's the way I t ' s l is te d In the d ire c to ry .

Is n 't It ?

A Yes, been lis te d that way for the past year.

Q Past year?

A Yes.

Q I t ' s been lis te d that way the whole time you've

been there, has i t not?

A No, It was under Centennial Lanes.

Q W ell, you've never changed that name o ff o f the

s id e o f your b u ild in g , have you? d

Null - adverse 23

A No, never have.

Q W ell, why d id n 't you change it ?

A Why d id n 't I change I t ? Why d id n 't I change I t ?

Q Yes, you sa id that you w eren't aware of the

Coffee Shop sign?

A That sign belonged to Foremost D a ir ie s .

Q I see; and you had them move It a fte r th is action

was brought, is n 't that true?

A Because we did not serve any of th e ir Ice cream

outside o f package.

Q But that was notice to people that food was being

served In s id e , Is n 't that true?

A I don't th ink so .

Q You don't th ink so?

A No.

Q Now, le t ' s go back to the time p rio r to and

Immediately a fte r th is action was ft led: You were serving

bacon and eggs out th ere , w eren't you?

A Bacon and eggs?

Q Yes; w eren't you?

A When?

Q Immediately before th is action was f i le d and even

a fte r It was f i le d ?

A We had bacon and eggs, hamburger s and hot-dogs.

Q R ight; as a matter o f f a c t , at the lunch area there

Null - adverse 2k

you had p ic tu re s o f the orders and the kind o f orders that

you served th ere , d ldn'tyou?

A I d id n 't put up any p ictu re s or anything pertain ing

to lunch.

Q You are saying that there were no signs ind icating

tiat food was served there?

A There was a sign up there something about chicken

dinner or something lik e th a t, that wasput th e re , I don't

know when; was put there long before I ever went on the

property.

Q And what kind o f condiments did you use, condiments,

s a lt and pepper; you used a l l o f those, d id n 't you? S a lt and

pepper?

A They were on the counter.

Q W e ll, you bought them, d id n 't you?

A Yes s i r .

Q Catsup? Catsup?

A Yes.

Q Mustard?

A No.

Q No mustard?

A No.

Q Any other sauces?

A No.

Q You used salad d ressin g , d id n 't you?

Null - adverse 25

No.

You d id n 't use salad d ressin g?

No.

You made your own mayonnaise to go In your sa lad s?

No, we purchased th a t.

You purchased It a lready made?

From the A. S- P. S tore .

You purchased your mayonnaise a lready made?

Mayonnaise?

Whatever mayonnaise you used on your sa lad s; did

I t yo u rse lf or you bought I t ?

We bought I t .

You bought i t ; what kind did you use?

W ell, whatever they sold at the A. & P. Store .

I see . What other kinds? I t a l ia n , Thousand Island?

Mayonnaise?

Yes?

No.

What's that?

I wouldn't know whether they call It that or not.

Any other? Did you serve orange ju ic e ?

Yes, th a t 's a beverage.

Yes, I sa id you served orange J u ic e , d id n 't you?

A Orange Ju ic e .

Yes, and you served beer?

Null - adverse 26

A R ight.

Q Name md the brands of beer you served?

A C arlin g , Bud, S c h lf t z , M i l le r 's , Blue Ribbon.

Q And you served coffee?

A R Ight.

Q And tea?

A R ight.

Q You sa id "yes"?

A Yes.

Q As a matter of fa c t , you had and you s t i l l have, do

you not, a counter and tab les w ith seats that go to them?

A They're there .

Q What's th at?

A They are there .

Q And they were up In use u n t l l Juried la te ly following

the f i l in g o f th is a ct io n , Is n 't that true?

A I f they wanted to s i t a t a ta b le , they would

come to the counter and get what they wanted and s i t at ta b le .

Q But you do admit that a l l o f the th ings that you've

enumerated were served by your lunch counter p rio r to the

f i l in g o f th is actio n ? Is n 't that true?

A At the lunch counter.

Q Now, I ask you, s i r , t e l l me about the bowling

lanesj do you have p it s ?

A Have what?

Null - adverse 27

Q P it s ? That I s , depressions In the flo o r where

seats are arranged In areas around the bowling a c t iv i t ie s ,

each bowling a c t iv it y or each lane?

A We have a se ttee .

Q A se tte e , how many people doe« It acoommodate?

A About f iv e to each lane.

Q F ive to each lane, and that does not Include the

two seats at the •

A - score ta b le .

Q - at the score ta b le ; A ll r ig h t , that would be

then f iv e times 25 lan es, Is that co rrect?

A T h at's co rre ct.

Q Ind the two seats at each o f the 25 lanes at the

scoring tab le?

A 2k lanes.

Q 2k, I'm so rry , s i r . A ll r ig h t , and back beyond

th a t , we have sp ectato rs' s e a ts , Is n 't that true*/

A There 's a row of sp ectato rs' seats across the

butId lng .

Q R ight. As a matter o f fa c t , there are several

rows, Is that co rre ct?

A No, one row.

Q W e ll, how many rows were there Immediately p rio r

to thb f i l in g of th is actio n ?

A One row Is a l l th a t 's ever been set In th ere .

Null - adverse 28

Q How many seats are there?

A How many seats acro ss that bu ild ing ?

Q Right?

A 1 wouldn't know unless there would be about -

they s i t In secdttons, probably 7or 8 In a se c tio n .

Q And how many sectio n s are there?q

A Maybe 10 or 12; 1 don't know e x a ctly .

Q Maybe 10 or 12; so, your rough estim ate would be

between 80 and 90 o f those, Is that co rre ct?

A T h at's r ig h t .

Q Now, in com petitive bowling there are q u ite a

number o f people who congregate for purposes o f observing

bowling a c t iv i t ie s ; is n 't that true?

A U su a lly th e ir fam ily .

Q Their fa m ilie s come to see them bowl?

A That would be about a l l that would be present,

yes, some o f those come In .

Q You don't have any re s tra in t on people coming in

to observe or sp ectate , doyou?

A No, we've never made any.

Q 1 see. Now, t e l l me one th ing , s i r s Is n 't It

true that your d ecision to subdue or change the eating

f a c i l i t y from a lunch oounter or lunchroom, or whatever

you want to c a l l I t , to a • what did you c a l l I t - beverage?

A Beverage oounter.

ANull - adverse 29

Q - beverage counter was because o f the f i l in g o f

th is s u it?

A No s i r , not e x a ctly .

Q Not exa ctly?

A T h at's not the case . It was a losing proposition

and th a t 's why It was taken out.

i

Q So then, for my e d if ic a t io n , w i l l you ind icate to

me whether or not your in i t ia l response was "not e x a ctly ?

D idn't you say that?

A No, we took I t out because it was a losing proposi-

tio n .

Q And these people who used the lunch-oounter, It

was there for purposes o f your bowlers and th e ir fa m ilie s ,

Is that r ig h t?

A It was there for th e ir accommodation.

Q Yesj you did say "yes"?

A For th e ir accommodation, r ig h t .

Q Now, would you in d ica te for the year 1964 the

gross Intake o f the lunch counter?

A There 's a s l ip over th ere . I don't have it here.

HR. RENTZt Did you say '64?

Yes.

I t ' s in the in te rro g a to rie s .

Then, I th ink w e 'll be ab le to s t ip u la te .

HR.KING:

HR. RENTZ:

HR. KING:

HR. RENTZ: W e'll s t ip u la te that the income was

Null - adverse 30

Hr. Rentz:

whatever Is re flec te d In the answers to the interroga

to r ie s , In our answers to your In te rro g ato rie s .

MR. KING: The fig u re was $14,115. The gross

for 1963 was $15,749.

_______ £ Now, how much does the counter p resen tly spend on

beverages per annum?

A I would have to look at those. ( F i le handed to

W tness by Hr. Rentz) . . . In December, *64, for beer we

spent $362.96.

Q And on orange Ju ice ?

A $58.50.

Q Coffee?

A That would come under A. &- P. and that was $31.36.

Q And other beverages, what would you say you spent

asid e from those enumerated?

A W ell, m ilk Is a l l we have under other beverages.

Q What Is th at?

A M ilk would have been the only other beverage that

we would have had. That was $9.02 that month.

Q The tea w asn't figured In that coffee th ere , was I t ?

A The tea was figured In the A. 6- P. co ffe e , $31.36.

Q Now, back to the bowling lan es: you have tourna

ments out at the bowling lan es, don't you, that Is the Hidtown?

A A ll league playmlght be ca lle d tournaments; th a t's

every n ig ht.

Null - adverse 31

Q Sweeps?

A Sweeps? What do you c a l l a sweep?

Q W e ll, scratch sweepers, is that what you c a l l them?

A We have had them.

Q W ill you defilne what a scrap sweeper is ?

A S c ra (c i>weeper? T h at's something where the

In d iv id u a ls get up and bowl against each o th er.

Q Where in d iv id u a ls get up and bowl against each

o th er, is that co rrect?

A Yes, th a t 's r ig h t .

Q How frequently do you have them, s i r ?

A We haven't had any for some time.

Q When did you la st have them?

A Last what?

Q When did you la s t have a scratch sweeper?

A I wouldn't know the date, probably back tin A p r il .

Q Back In A p ril?

A More than l ik e ly ; (don't know.

1 ;f , • . - • ■ s . ' . ■ .£

Q What's that?

A Could have been in A p r il .

Q W ell, w ith in 3 or 4 months?

A Yes.

Q C e rta in ly you've had one since the f i l in g o f th is

a ct io n , haven't you?

A Had one sin ce when?

Null - adverse 32

!! Q The f i l in g of th is actio n ?

A Yes.

I! Q Do you remember the date on which 1 took your

depo sitio n , Mr. N u ll?

A The date that you took it ?

Q Yes. i c a l l your attention to the date on which

your deposition was taken -

THE COURTs T e ll him what date It was; t e l l him,

you remember I took your deposition on a ce rta in date.

_______ £ Mr. K ina: you remember I took your deposition

on October 9 , 1965?

A Yes.

i Q Over at the County courthouse?

A Yes.

Q Do you remember when 1 asked youthe following

questions: Page 29: " I ask you, s i r , dtd you ever hold any

scra tch sweepers'1 and your response was "There's been some

scra tch sweepers held in Albany but not In our house. We

don't hold them a t a l l . "

Now, do you remember th at?

A W ell, 1 d id n 't promote a scratch sweeper. Th is

was promoted by the a s s is ta n t out th ere , which I d id n 't know

about.

Q But that Is your testim ony, Is n 't I t ?

A Right.

Null - adverse 33

Q I d id n 't askyou who sponsored i t ; you spoke for your

bowling a l le y out th ere , d id n 't you?

A No, I spoke for m yself. You asked me i f I ever

sponsored i t .

Q Now, you made the d is t in c t io n o f th is kind o f

refinement in your own mind in answering that question , s i r ?

A O idn't you ask me i f 1 sponsored one2

Q 1 s p e d if ic a lly sa id "you"?

A 1 did because I never signed any s l ip s for any.

Q I see. 2How far did you go in school, s i r ?

A How fa r did 1 go in school?

Q Yes?

A I went through high school.

Q A ll r ig h t , you know th e re 's a c o lle c t iv e "you" and

a sin g u lar "you", don't you? S ir ?

A f ig h t .

Q Now, you d id n 't go through the so p h isticated mental

process o f d istin g u ish in g between the c o lle c t iv e "you" and

the s in g u lar "you", did you, In answering th is question?

A No, I ju s t answered that I d id n 't sponsor i t .

I d id n 't put I t on. In fa c t , that was it } I d id n 't know

nothing about what went on about i t .

Q But, d id n 't you In the answer presume to answer

for the whole house, when you sa id "theredhas been some

scratch sweepers held in Albany but not in our house"?

Null - adverse

A We w eren't holding them In our house; no, we're

not holding any in our house.

Q But you were holding them, you admit -

A We d id , p rio r .

Q P rio r to the f i l in g o f th is action and even a fte r

the f i l in g o f th is actio n ?

A That? No, we haven't had a sweeper In our house,

as I to ld you, s in ce back In probably A p r il , sometime In

th ere , probably .

Q Now, p rio r to the f i l in g o f th is s u it , you sent

out announcements o f these co n tests , d idn'tyou?

A 1 d id n 't send those announcements out. What

announcements ever went out went out through our a s s is ta n t .

Q Went out through your a s s is ta n t?

A Yes, that promoted i t .

Q Now, th is a s s is ta n t is your agent, is he not?

A Yes.

Q You sa id "yes"?

A R ight.

Q Now, when 1 asked you whether you sent them out,

s i r , I'm a lso speaking for your agent. Then, your testimony

is that Hidtown Bowling Lanes did send out announcements

of th is com petitive a c t iv it y being held at Midtown, is n 't

that true?

A The sweeper, r ig h t .

3k

Null - adverse 35

Q Yes?

A R ight.

Q And It was sent a l l over the area ; that I s , w ith in

an area of roughly 100 or so m iles of here, Is n 't that true?

A I don't know where they were sent to .

Q You don't know where they were sent?

A Because I did not send them. My name was not on

the sweeper or the f ly e r of any kind.

Q But Midtown's name was on the f ly e r , wasn't It ?

A R ight.

Q And they Invited people to come to Midtown?

A It was an announcement.

Q Yes, but wasn't that an In v ita tio n to people?

A T h at's what the f ly e r would have been fo r , for

promotion o f the sweeper.

Q Which was held at Midtown?

Q Right.

Q Now, you know, as a matter o f fa c t , that teams from

F lo rid a have come to your p lace and bowled, haven't they?

A Teams?

Q Yes, bowling teams have come to your bowling a lle y

and bowled from F lo r id a , Is n 't that true?

A A sweeper Is not set up as teams. I t ' s In d iv id u a ls .

Q W ell, I'm not speaking In term of sweepers at th is

p o in t, s i r . There have been teams, bowling teams, from F lo rid a

Null - adverse 36

that have bowled In /our p lace?

HR. BURT: I f Your Honor p le a ses , I think we

ought to lim it th is to the time of the action under

which they are proceeding which came Into being la s t

summer and begin back In Ju ly of 196k rather than go

back over a period o f years.

A The W itness: I don't th ink so.

MR. KING: A ll r ig h t , I f Your Honor p leases ,

I w i l l rephrase the question.

_______ Q C e rta in ly It has been the p reva ilin g p o licy of

your Lanes to In v ite and allow teams from F lo rid a to part I c l*

pate in bowling there; is n 't that true?

A We've had teams £rom around Georgia but I don't

know o f any teams coming from F lo r id a .

Q You don't deny that there have been teams from

F lo rid a ?

A I'v e never recognized any teams from F lo r id a .

Q But then, of course, your agent might have In your

absence, Is that co rrect?

A W ell, I wou ld n 't say so because I don't know about

I t .

Q You don't know?

A No.

Q Now, who Is your agent who sent out these sweepers,

that Is no tice o f sweepers?

Null - adverse 37

A Herman Kramer.

Q Herman who?

A Kramer.

Q Is th is Mr. Kramer here?

A No s I r .

Q How long has Mr. Kramer been with you?

A About one year.

Q About one year?

A Yes.

Q Who was your agent or the person that served the

function that Mr. Kramer now serves before Mr. Kramer was so

delegated that re s p o n s ib ility ?

A W e ll, Mr. Hendley was on there for a w h ile for

him, fo r Kramer.

Q You know Mr. Dave Mooee, don't you?

A Dave Moore ?

Q Yes?

A No.

Q You don't know him?

A 1 don't know the name, no.

Q Do you know the manager or operator o f Parkway

Lanes down at T a lla h a sse e , F lo rid a ?

A I do not.

Q You do not?

A No.

Null - adverse 38

Q As a matter o f f a c t , you hold your doors open to

people from everywhere, Is that co rre ct; that I s , to come and

bowl?

A No.

Q That I s , whether they are from w ith in the State of

Georgia or without the State o f Georgia?

A No, we don't s o l i c i t anything but our lo ca l bowlers

here.

Q You don't s o l i c i t anything but your lo ca l bowlers;

I see. As a matter of f a c t , that was the amendment that

you f i le d th is morning, wasn't i t ? You changed your answer

18 to read that you only hold yo urse lf out to serve local

bowlers In Albany, Ga. area at a l l tim es, is that co rrect?

A T h at's r ig h t .

Q Now, I c a l l your attention to la s t week and ask

you whether or not you are aware that there was a regional

meeting of Nobles In Albany?

A I don't know -

Q S h rln ers?

A Oh, I know the Shrlners were here, yes.

Q R ight, and you know that they had a regional meeting

here, to ta lin g some 6ip000, is n 't that true?

A I don't know how many they had. I know that they

had a meeting here and had a parade here.

Q R ight; you read the paper, d id n 't you?

Nall - adverse 39

A Yes.

THE COURT: He says he knows they were here and

had a parade. Go ahead.

MR. KING: I was asking him about q u an tity , Your

Honor.

0 You know that there were thousands who were supposed

> %• . •••

to have been here , don't you?

I don't know what th e ir p a rt ic ip a t io n was at a l l .

Old you meet any from out of s ta te ?

No, I did not.

You did not?

No.

Were you at your bowling a lle y ?

Yes s i r .

You were there a l l week or during the e n tire period

were here?

I was.

You d id n 't screen them, did you?

I wouldn't know. I wouldn't know i f any o f them

in there because I d id n 't see anybody but local

You d id n 't exclude anybody who came there during

th is period, did youl?

MR. BURT: Your Honor p lease , I would lik e to

Intercede here to make an o b jectio n . We're going over

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

A

Q

that they

A

Q

A

ever come

people.

Q

Null • adverse ko

Mr. Burt:

something that happened la s t week. They a lleg e here

the incidents that th ey 're re ly in g on and we can go on

and on and on. We would lik e to lim it the examination

to what he says happened on these two o ccasio n s, p lus

what h is p o licy was at that time.

THE COURT: W e ll, I t ' s a lready been gone over now.

MR. BURT: But he seemed to be going over it

continuously.

THE COURT: Go ahead, go ahead.

Mr. King: As a matter o f fa c t , your bowling

lanes welcomed the Shriners who were here from a l l o ver,

d id n 't you?

A We give them an ad.

Q You gave them an ad?

A R ight.

Q W ell, you went beyond th at? What do you mean, you

gave them an ad?

A They come In and asked for a donation.

Q A donation? So, you could run i t in th e ir -

A Local people come in and asked me for th a t.

Q For an ad in th e ir program?

A Yes.

Q I see . What did the ad say?

A I don't know what the ad sa id .

Null - adverse 41

Q You d id n 't bother about It ?

A No.

Q But you did put an ad In th e ir lo ca l -

A I g ive them a donation of $15.

Q W ell, there was, as a matter o f f a c t , an ad In th ere ,

wasn't there?

A I d on 't know i f they had It In there or not.

I d id n 't see i t .

THE COURT: You gave them a donation of $15.00,

you say; was that your answer?

The W itness: T h at's r ig h t . T

_______ £ Mr. King: You did pay th is $15.00; a l l r ig h t ,

now what e lse did you do In order to cooperate w ith the

Shriners being here?

A T h at's a l l 1 know o f .

Q T h at's a l l you know?

A R ight.

Q 1 submit to you what has been id e n tif ie d as P -1

and ask you whether or not that is a v a lid representation

of what the front portion o f Midtown, the bowling house

that you operate, looks lik e ?

A R ight.

Q I ask you, s i r , to take note o f what Is exh ib ited

on the face or the front o f your bowling house In terms of

bunting? W ill you t e l l me what that I s , s i r ?

A

Null - adverse 42

I t must be something that they have there . They

put I t up. I d id n 't know that they were going to put anything

l ik e that up. I ju s t give them an ad.

Q But you were aware that It was th ere , w eren't you?

A 1 saw It there.

Q Yes?

A Afterw ards, a fte r they had put It up; 1 d id n 't see

It before

Q And what does It say , s i r ?

A 1 never read I t , 9 don't know.

Q W ill you Ind icate what I t says on th ere , s i r ?

A 1 co u ld n 't t e l l you. 1 don't know what th e ir

le t te rs stand for

Q W ell, those are -

A It says "Welcome".

Q It says "Welcome", Is n 't that true?

A R ight.

Q 1 see . Now, 1 ask you, s i r , to Id d ntlfy what

has been Id en tif ied as P-2 MND ask you whether or not that

Is not an accurate representation and v a lid representation

o f what your build ing looks l ik e from the angle that that

photograph was taken?

A T h at's the b u ild in g .

Q It Is the bu ild ing?

A Right.

Q And I c a l l your attention s p e c if ic a l ly - s t r ik e

th is - Th is p ictu re was obviously taken during the time that

the Nobles were here) Is that true?

A It could have been, yes.

Q W e ll, I c a l l your attention to that same bunting?

A Yes, th a t 's r ig h t .

Q You would agree that th a t 's true?

A I would agree It could have been taken then.

Q Now, I c a l l your attention to the le f t part o f -

THE COURT: Just put the p ictu re in evidence and

It w i l l be in evidence for me to see. There 's no use

reviewing w ith him a l l o f the d e ta ils that the p ictu re

shows; Ju st le t him look at It and then put it In evidence.

HR. KING: There were s p e c if ic questions, Your

Honor.

THE COURT: A ll r ig h t , ask him any question that

you want to but don't have him go over the d e ta ils and

put Into the record what he sees in the p ictu re and a l l

o f th a t. The p ictu re I t s e l f is the best evidence o f

what It shows.

HR. KING: A ll r ig h t , Your Honor.

_______ 51 I c a l l your attention to the rig h t portion o f the

p lctiju re and what appears to be a parking lo t ; is that the

Null - adverse i»3

parking lo t o f the Hldtown Bowling Lanes?

A Oh yes, that goes w ith i t .

Null - adverse

Q That goes w ith it and, o f course, people using

the bowling lan es, i t ' s there for th e ir use; Is that co rre ct?

A R ight.

Q As a matter of f a c t , people a lso park over in the

tot Immediately across In front o f the p la ce , Is n 't that

true?

A They park on the s t r e e t , across the stS reet and In

the to t.

Q I ask you, s i r , whether or not you re c a ll on or

about Hay 30 Negroes coming to your establishm ent and

presenting themselves for purpose o f se rv ice at your lunch

counter?

HR. RENTZt What date was th a t, Counsel? I d id n 't

hear that d ate , p lease s i r .

HR. KING: The 20th, I b e lie v e .

HR. BURT: You sa id 30th.

_______ £ Hr. King: W ell, I re tra c t the e rro r there

o f 30th I f 1 sa id that - the 20th?

A 1 never saw anyone.

Q You never saw anyone?

A At the counter.

Q Who was your counter g ir l at that time?

A H rs. Reber.

Q H rs. Reber? Did she have any occasion to t e l l

that Negroes presented themselves?

Null - adverse 45

A Never to ld me anything about any o f them being

th ere .

Q You do admit that you are In your bowling house

every evening, a ren 't you?

A Yes, 'most every evening.

Q No fu rth er questions.

THE COURT: You may go down.

HR. KING: P la in t i f f c a l l s Hr. Oave Moore.

DAVID H. MOORE

w itness ca lle d by the P la in t i f f s , being

f i r s t duly sworn, t e s t if ie d on

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY HR. ROBERTS:

Q Hr. Moore, would you p lease sta te your name for

the record , s i r ?

A David H. Moore.

Q And where are you from, Hr. Moore?

A T a lla h a sse e , F lo r id a .

Q What Is your occupa t Ion?

A Manager, President and General Manager o f Parkway

Bowl.

Q Parkway what?

A Parkway Bowl.

Q And that Is a bowling establishm ent In Ta llah assee

F lo rid a ?

Moore - d ire c t 46

A Yes.

' Q Have you been a bowler yo urse lf p erso n ally for a

long tim e, for a protracted period o f time?

A 3 o r 4 years.

Q Does Parkway, your estab lishm ent, hold tournament

co n tests , sweeps and events o f that nature7

A Yes.

Q Do you p u b lic ize these events? W e ll, le t me put

It th is way: Have you on any occasion sent out f ly e rs

announcing these events?

MR. BURT: Now, Your Honor p lease , we don't see

the relevancy o f what h is bowling a l le y may have to do

w ith respect to Midtown Bowling Lanes and we object to

going Into th is as ir re le v a n t .

MR. ROBERTS: I Ju st wanted to e s ta b lish that It is

the custom.

MR. BURT: W e ll, the custom has nothing to do

with our Midtown Bowling Lanes.

MR. ROBERTS: In the bowling business.

THE COURT: Mr. Roberts, the defendant, Mr. N u ll,

has stated that on the occasions referred to , that h is

establishm ent sent out f ly e r s , n o tices about, I be lieve

what you c a l l , scratch something; so , i t ' s what he did

and not what thealcustom is .

MR. ROBERTS: I withdraw I t .

Moore - direct; 47

_______ SL Mr. Roberts: Okay, have you ever at your e sta b lish *

ment received any no tices from Mldtown Bowling Lanes announc

ing tournaments, co n tests , sweepers and the lik e ?

A Yes.

THE COURT: Now, le t ' s bo more s p e c if ic now

about th a t. That was about a t r ip le question . L e t 's

break It down and see what It was.

MR. ROBERTS: When you say t r ip le question , you

mean tournaments, contests and sweepers.

THE COURT: W ell, yes, le t ' s see what It was.

Q Mr. Roberts: Have you ever received any -

THE COURT: Just ask him what h e 's received .

Q Mr. Roberts: Okay, w i l l you t e l l the Court what

announcements you'be received?

A In the la s t what tlmd pdrlod.

Q Say the la st year?

THE COURT: From Midtown Bowling Lanes?

A The W itness: The only one I can remember receiv ing

Is a scratch sweeper and match game f ly e r .

Q Just one f ly e r ?

A One f ly e r about two d iffe re n t events.

Q One f ly e r announcing two d iffe re n t events?

A Yes.

Q On two d iffe re n t dates?

A The same date.

Moore - d ire c t U8

Q Do you of your own knowledge know that any patrons

o f your establishm ent have gone up to Midtown Bowling Lanes

In Albany, Georgia, to p a rt ic ip a te in events up there?

A Yes s i r .

Q Were those pairtIcipants resid ents o f the State of

F lo r id a , to the best of your knowledge?

A Yes s i r .

Q Do you know the owner o f Midtown Bowling Lanes,

Albany, Georgia? Would that be Mr. G. L . N u ll?

A Yes.

Q Have you known him for a period o f time?

A Eight years.

Q Do you know him w e ll?

A No, not p e rso n a lly . I'v e met him on 2 or 3 o ccasio ns.

Q What were the occasions in which you met Mr. N u ll?

A I th ink the la s t time I ta lked to Mr. N u ll, I was

tn h is establishm ent promoting a tournament which was going

to be held tn my establishm ent.

Q Now, a l l o f the questions that I'v e asked you

about Midtown Bowling Lanes, I assume that a l l o f your

answers have been predicated on the fact that Mldtown Bowling

Lanes are located in Albany, Georgia, owned and operates by

Mr. Glen L. N ull} is that correct?q

A Yes.

Q What kind of equipment do you have in your house?

MR. BURT: Your Honor p lease , we ob ject to that

as having no relevance here, what kind o f equipment

they have.

_______ £ Mr. Roberts: Do you know what kind of equipment -

I ' l l withdraw that - Do you know what kind o f equipment Mr.

Null has?

MR. BURT* I would make the same ob jection as

to what kind o f equipment Mr. Null has would not shed

any lig h t on reoovery under the C iv i l R ights Act.

THE COURTt Yes, I don't see how that would help

us at a l l .

MR. KING: I f Your Honor p le a se s , the theory on

which our case Is predicated Is tw o-fold . We submit that

th is question has relevancy under the section o f the Act

which re la te s to sporting events, amusements and a c t iv it y

o f that s o r t . I f , o f course, the Court has an a ttitu d e

which precludes th is testimony being e l ic i t e d and as

being Inadm issib le , we would request In that event that

under Rule A3(c) that we be permitted to put on a showing

o f what th is s itu a tio n In fact i s .

THE COURT: W e ll, 1 have a lready indicated my

view prev io usly in ru ling on the In terro g ato ries and

requests fo r adm ission, I th in k . I t ' s my view that

whatever kind o f equipment they've got in the bowling

a lle y Is not o f a ss ista n ce In determination of the Issue

Moore - d ire c t k9

Moore - d ire c t 50

The Court:

ra ised here. So, I susta in the o b jectio n to that and

I o verru le your motion to add to the record or go into

i t at a l l . I don't see how ft could help us at a l l .

MR. KING: May I make one or ask one question ,

Your Honor?

THE COURT: Yes.

MR. KING: Then, Is the Court ru lin g , as a

matter o f law, that the question purportingto show,

that is a question ca lcu la ted to e l i c i t information

bearing upon a demonstration o f equipment which moves

In In te rsta te commerce in th is a c t io n , the Court Is

ru lin g , as a matter o f law, it would have no relevancy

tn th is actio n .

THE COURT: That's my view.

MR. KING: And th a t 's the ru lin g of the Court.

THE COURT: I'm ru lin g , I have Ju st ruled that

your question about what kind o f equipment he has in

the bowling a l le y is not pertinent to the issue as I

see It and I exclude the evidence thereto .

MR.KING: Thank you veryk in d ly . Your Honor.

_______ 2 Mr. Roberts: Then, F lo rid a bowlers shave attended

Mfdtown Bowling Lanes, Albany, Georgia and p artic ip ated In

tournaments?

MR. BURT: We ob ject to that as being a leading

question . He has a lready asked him -

Moore - d ire c t 51

THE COURT: I don't remember him saying anything

about p a rt ic ip a t in g In tournaments. I don't remember

what the exact language o f your previous question was,

but Idon't re c a ll the use of your word "tournament", and

I th ink I t ' s going to be pertinent to find out how he

knows about these things he's te s t ify in g about anyway,

as to whether he knows th is or whether th is is Jusfi some

thing that somebody to ld him. I presume that w i l l be

brought out la t e r . Suppose we find out about that

rig h t now, so we won't be wasting time tf i t is hearsay.

BY THE COURT x

Q You sa id something about some people from F lo rid a

having come up here and bowled at Midtown Bowling Lanes:

did you see them?

A No s i r .

Q You d id n 't see them?

A No s i r , Id ld n 't come up w ith them.

Q You d id n 't come w ith them?

A No.

Q Are you ju s t reporting something that somebody

to ld you, is that i t ? In other words. Is that the basis

o f your inform ation, thftt you were simply to ld that they

came up here, or what is the b asis o f your information?

A W ell, you would be r ig h t . A ll I would have would

be what they to ld me.

Moore - d ire c t 52

BY MR. ROBERTS:

_______ 0 Mr. Roberts: Let me ask ond fu rth er question along

th is lin e and I ' l l c le a r th is up: Did you or did you not pay

a team fee - I don't know enough about bowling to know the

co rrect name - but did you or did you not pay some kind of a

team fee for a team from Partway Lanes to bowl at Mtdtown?

A When you say me or when you say did I , are you

re fe rrin g to e ith e r me or Parkway Bowl?

Q I'm ta lk in g about the a l le y which you own?

A No s I r .

Q N either you nor the a lle y ?

A N o sir.

Q When you sa id to me - have you sa id to me that no

team from Parkway has bowled at Midtown?

THE COURT: W e ll, he 's indicated that I t ' s a l l

hearsay. He's Indicated that a l l o f h is testimony is

based on hearsay about that fact) so , that would not be

ad m issib le .

MR. KING: About what. Your Honor?

THE COURT: H is testimony about people having

come up here from F lo r id a . He says th a t 's based on

hearsay, so that would not be ad m issib le .

_______ 2 Mr. Roberts: Were there any trophies or p rize s

won by any o f the F lo rid a bowlers at Midtown to your knowledge?

THE COURT! Here again , le t ' s fin d out whether

he 's te s t ify in g about something that he saw or knows

Moore - d ire c t 53

The Court:

about p erso n a lly or whether I t ' s Just something that

somebodyto Id him, because w e're ju s t wasting time If

i t ' s ju s t something that somebody to ld him.

MR. ROBERTS: W e ll, as a matter o f fa c t , Your Honor,

I don't know.

THE COURT: W e ll, ask him that f i r s t . L e t 's

don't waste time on hearsay and then have to ru le it

o ut. L e t 's find out. As a matter o f f a c t , it seems

to me that you should have known that before you put him

on the stand. He's your w itn ess.

BY THE COURT:

Q Now, that question he Just asked you, Mr. W itness,

h e 's asking you about some trophy or something: Do you have

a»y personal Inform ation, did you see any trophy awarded or

do you know o f your own knowledge that any trophy was awarded

in the nature that he 's ta lk in g about?

A No s i r . The day we are In reference to was not a

trophy date anyway. It was s t r i c t l y a cash day. As to

whether any one In quedstion won any cash or no t, I'm not

real p o s it iv e .

Q You don't know?

A I'm not su re . The only thing In regards to th e ir

being here, I saw them before they le f t and a fte r they

returned

Moore - d ire c t 54

Q And they to ld you they had been up here?

A And they to ld me they had been In Albany, th a t 's

r ig h t , s i r , s t r i c t l y th a t.

BY MR. ROBERTS:

Q W ill you s ta te the names o f the people who to ld

you before they were leaving for Midtown Bowling Lanes and

the people who came back and sa id they had Ju st returned from

Mfdtown Bowling Lanes; w i l l you g ive me th e ir names or as

many names as you can remember?

MR. BURT: I f Your Honor p lease , I o b ject to

that as being hearsay, as to what somebodytold him, who

It was; we o b ject to ItZ

THE COURT: Yes, I'm not going Into th at. What

they to ld him Is not ad m issib le , so It doesn't make any

d iffe ren ce whether th e ir names were John Smith or Paul

Jones. He can 't t e s t if y about what they to ld him.

Mr. Roberts, th is man Is your w itness and you're

putting him on the stand now and apparently using hlfa

for d iscovery purposes, your own w itn ess. Apparently,

you d id n 't Interview him aw a l l before you put him on

the stand. I don't want to take th is co u rt's time for

you to put a w itness on, your w itn e ss , and use him fo r

d iscovery purposes during the t r ia l o f the case . Ask

him, go ahead and ask him any question that he can answer

w ith in h is personal knowledge but le t ' s dont waste time

on hdarsay.

Moore - d ire c t - cross 55

MR. KING: Excuse me ju s t a minute, Your Honor

e e . No fu rth er questions.

CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. BURTS:

Q Mr. Moore, you say you've been in the bowlIng

business how long?

A 3 to k years.

Q There In T a llah assee?

A No s 1 r .

Q Pardon me?

A Not e x c lu s iv e ly .

Q W e ll, how long have you been continuously managing -

A Two years in T a llah assee .

Q Two years and during th is time you only have reco l-

lectiton o f one f ly e r coming from Midtownto you, Is that r ig h t?

Was that your testimony?

A No s i r , I th ink we sa id that was In the past year.

Q In the past year you have re co lle c t io n o f only one

f ly e r , is that r ig h t?

A D efin ite re co lle c t io n o f one.

Q Do you have any copy o f that f ly e r w ith you?

A Not w ith me, no.

Q Do you have i t at your p lace o f business?

A T h is 1 wouldn't know) I wouldn't say for sure ; i t ' s

p o ss ib le .

Moore - cross 56

MR. BURT: Your Honor p lease , we do move to

exclude any testimony on the ground o f hearsay as to

p artIc ip a tio n g .

THE COURT: W e ll, I'v e a lready indicated that

th a t 's not adm issib le and I am not going to consider

anything that he has t e s t if ie d to based on hearsay.

A lt r ig h t , you may go down.

The W itness: May I be excused?

THE COURT: Yes, you're excused, as fa r as the

Court is concerned.

MR. BURT: I t ' s a i l r ig h t .

THE COURT: A ll r ig h t , you're excused.

C H m is_^ w j.LL ,L^ i$ ,

w itness ca lle d by the P la in t i f f s ,

duly sworn, t e s t if ie d on

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR.KING:

Q Would you sta te your f u l l name for the record , s i r ?

A Charles Eugene W l1llam s.

Q Where doyou l iv e , Mr. W illiam s?

A 806-C Odom.

Q That Is in Albany, Georgia, Dougherty County,

Georgia, Is that r ig h t?

A T h at's r ig h t .

Wi l l lams - d irect 57

Q Hr. W illiam s, I ask you whether or not you have any

Independent re co lle c t io n as to where you were working for

the la s t four years?

A W ell, the la s t four years, approximately the la s t

four years I'v e worked to Hldtown Bowling Lanes for three

years and went back and worked about 7 months and q u it .

Q When did you q u it?

A About 3 i months ago.

Q About three months and a h a lf ago?

A Yes.

Q Now, do you know the P la in t i f f here, Mr. N u ll?

A Yes s i r .

Q Do you know the gentleman there next to him?

A Yes s i r .

Q Those were the persons under whose supervision

you worked?

A Yes s i r .

Q What sp e c if lea l1y were your duties at Midtown Bowling

Lanes, Mr. W iliam s?

A Pin chaser.

Q You were a pin chaser?

A Yes.

Q What are the d uties o f a pin chaser?

A W ell, I f something go wrong w ith the machinery,

I do the best I can on the b a lls and getting the p ins up

Wi l l lams - d ire c t 58

or the b a lls or something l ik e th a t.

Q Does th is confine you g en era lly to any given area

o f the bowling house?

A What you mean by that?

Q Does I t mean that you are required to stay at any

given area o f ghe bowling house or bowling lanesi that I s ,

your employment( where Is your work ca rried out?

A It ca rr ie d out?

Q I say , where is i t ca rried oni where did you do

your work. In what part o f Hldtown Bowling Lanes?

A W e ll, I do I t In the back and the front what a l l

they want me to do up front and d iffe re n t things l ik e th a t.

Q Then, were there other chores or d u ties you had

asid e from taking care of the machinery?

A W e ll, I clean up or something up fro n t, you know

clean up fro n t.

Q I ask you, s i r , what, t f anything, besides the

bowling a lle y s did Hldtown have?

A W ell, I don't q u ite catch on there .

Q Did 5hey serve food? They served food at Hldtown

d id n 't they?

A Oh yes s i r .

HR. BURT: Now, you're g iving him a leading

question , "they servdd food, d id n 't they?" We ob ject

to him leading h is own w itn ess, Your Honor.

Will lams - direct 59

THE COURT: Yes, don't lead him.

HR. KING: I ' l l rephrase I t , Your Honor, very

happy to .

_______ £ Did they or did they not serve food at Midtown?

A Yes s i r .

Q Would you In d ica te , I f you know, what foods were

In fa ct served?

A W ell, hamburgers, hot-dogs and cold d rin k s.

Q Drinks,you sa id ?

A T h at's r ig h t .

Q Orange ju ic e ?

A No orange Ju ic e .

Q No oringe Ju ice ?

A 2 I don't know; I don't know. Probably, I don't know.

Q I ask you whether or not they were operating th is

lunch-counter at the time that you le f t ?

A Yes s i r , I th ink they was.

Q Did you ever have an occasion to use the lunch

counter In terms o f getting food from It ?

A Yes s i r .

THE COURT: What was the answer?

HR. KING: He answered In the a ff irm a tiv e , Your

Honor.

THE COURT: In other words, you ate there at the

lunch-counter?

A The W itn o ss : I bought food from the lunch oounter.

Q Mr. King: Are you making a d is t in c t io n between

what the Judge asked you and what you say - that I s , the

Judge asked you - In other words, you ate there and you

said that you bought food there?

A Yes.

Q Now, did you a c tu a lly s i t up at the tab le?

AOh, no s i r .

Q What Is your Id en tity ? What race do you belong to?

A Negro race .

Q You belong to the Negro race?

A Yes.

Q Did you over the period that you were there ever

see a Negro served at that lunch oountex?

A No s i r .

Q Do you know o f any Negroes presenting themselves

for se rv ice there?

A Wel l , Ju st once in tournament; they d id n 't go to

the snack bar.

MR. BURT: What is that?

_______ £L Mr. King: You sa id once In a tournament and

what happened?

A They d idn 't - one or two bowled out there in

tournament.

Q Do you know whether or not they tr ie d to get se rv ice

Williams • dlrect j 60

Will lams - diredt 61

at the counter?

A No s i r .

Q I ask you whether or not you knew the p o licy of

the lunch counter as regards the se rv ic in g o f Negroes food

at the counter; did you know what the p o licy was?

A No s i r .

Q Did you ever hear Mr. Null or any o f your other

supervisors -

THE COURT: Don't lead him now* Mr. King; don't

lead him; he 's your w itn ess. Frame your question In such

a manner as not to lead him.

_______ fit Mr, M.n.fli

To your knowledge, has Mr. Null or any of your

employers indicated whether se rv ice would be given to Negroes

there?

A No s i r , I a in 't heard them.

Q You never heard them say?

A My Job was Ju st to do my Job and leave. 1 w asn't

there and I a in 't never heard them say nothing.

Q I ask youwhether you have or have not ever seen

Negroes turned away from the lunch counter?

A W ell, they d id n 't q u ite make I t to thelunch oounter.

Q What happened?

A W e ll, they asked them to leave.

Q "They" who?

A The man at that desk asked them to leave; someone

asked them to leave

WIU?ams - d Irect 62

Q Did you or did you not see them go In the d ire ctio n

o f the lunch counter?

A No s i r , because when I be walking toward the

counter, someone meet them about half-way to the counter

and ask them to leave; so a l l df them leave.

Q How many times have you seen th is take p lace?

A About once o r tw ice .

Q W e ll, has It been more than once?

A Once.

Q What's th at?

A Once as fa r as I can see. I d id n 't see but once

but I would be coming from the front and I do n 't know what

happened.

Q You have seen other Negroes leaving the front

portion?

A Yes s i r .

Q Aside from the one Instance that you know about,

on other occasions you've seen Negroes leaving the front

entrance?

A Yes s i r .

Q That I s , from what portion would they be leaving?

A What you mean?

Q W ell, you ta lk about the counter; where Is the

counter located? On the Inside where Is the oounter located?

A I t ' s located In th is p o sitio n as you come In the

door ( In d ic a t in g ) .

+

Q

A

Will lams - direct 63

As you come In the door you would be facing I t ?

T hat's r ig h t .

Q Where did you always see or where, I f any, did you

see or at what p lace rather on the occasions that you've

mentioned that you saw Negroes ldavlng, asid e from the one

Instance, where did you see them leaving from?

A Leaving from the desk-1 Ike going back out.

Q Going back o utsid e?

A Yes.

Q Had you seen them beyond the desk?

A Yes s i r , on the s id e , there on the s id e l ik e ,

standing on the s id e l ik e .