Defendants' Seventh and Final Revised Trial Exhibit List

Public Court Documents

February 26, 1993

32 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Defendants' Seventh and Final Revised Trial Exhibit List, 1993. 6f6c3e70-a246-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bbe5f306-f18a-4c20-ad46-2ab858923ae7/defendants-seventh-and-final-revised-trial-exhibit-list. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

|

|

WILLIAM A, O'NEILL, ET AL.

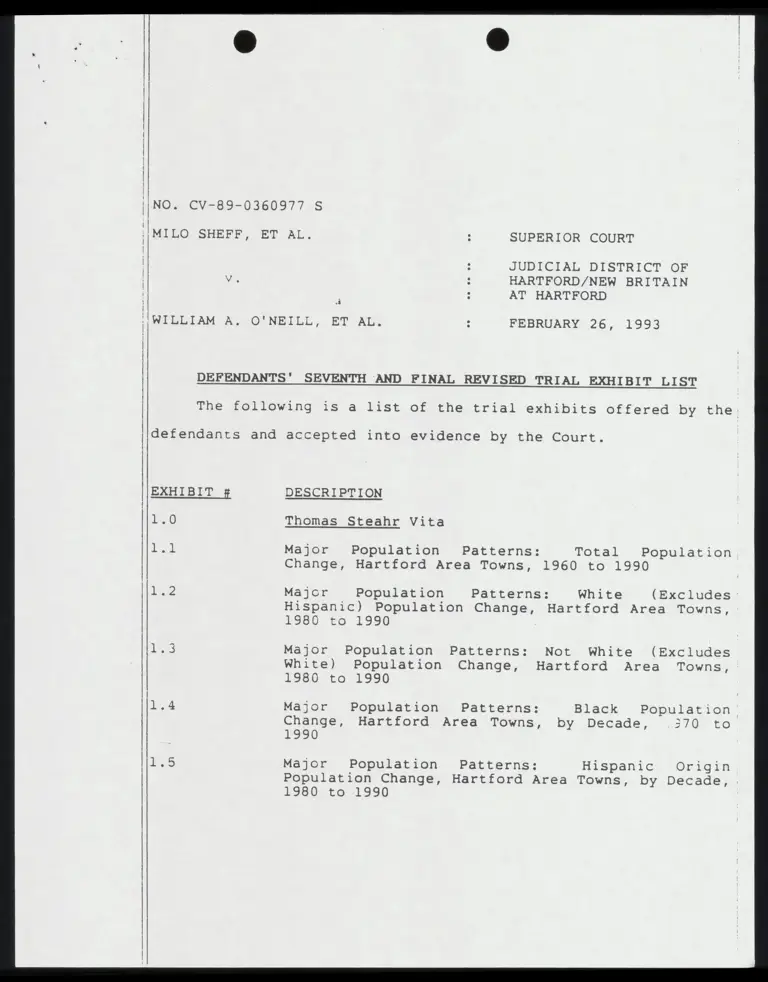

NOL. CV-89-03560977 8

{MILO SHEFF, ET AL. : SUPERIOR COURT

JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

AT HARTFORD

FEBRUARY 26, 1993

DEFENDANTS' SEVENTH AND FINAL REVISED TRIAL EXHIBIT LIST

EXHIBIT ¢

1.0

1.1

The following is a list of the trial exhibits offered by the

defendants and accepted into evidence by the Court.

DESCRIPTION

Thomas Steahr Vita

Major Population Patterns: Total Population

Change, Hartford Area Towns, 1960 to 1990

Major Population Patterns: White (Excludes

Hispanic) Population Change, Hartford Area Towns,

1880 to 1990 :

Major Population Patterns: Not White (Excludes

White) Population Change, Hartford Area Towns,

1980 to 1990

Major Population Patterns: Black Population’

Change, Hartford Area Towns, by Decade, .370 to

1990

Major Population Patterns: Hispanic Origin

Population Change, Hartford Area Towns, by Decade, .

1980 to 1990

Major Population Patterns: Asian Population

Change, Hartford Area Towns, 1980 to 1990

Major Population Patterns: Components of Change

Total Population, 1980 to 1990

Major Population Patterns: Components of Change

White .i Population, Hartford Area Towns, 1980 to

1880

Major Population Patterns: Components of Change,

Black Population, Hartford Area Towns, 1980 to:

1530 :

Major Population Patterns: Components of Change, |

Other Population, Hartford Area Towns, 1980 to

159(

Majcr Population Patterns, Ethnic Identification!

(Tables 11 and 12, Figure 10) Hartford Area Towns,

1990

Major Population Patterns, Ethnic Identification,

(Table 13, Figure 11) Hartford Area Towns, 1990

Major Population Patterns: Foreign Born

Population, Hartford Area Towns, 1990

Major Population Patterns: Total and “Black:

Population Size, Connecticut, 1900 to 1990

Lloyd Calvert Vita

Hartford Area Map

Total Enrollment - Hartford, 1881-91

Minority Enrollment - Hartford, 1981-91

Total Enrollment - 21 Suburban Districts, 1981-91

Minority Enrollment ' -. 21 Suburban Districts, |

1581-91]

Table: Total Public School Enrollment, Hartford

and 21 Suburban Districts, 1980-91

Minority Public School Enrollment, Hartford and 21

Suburban Districts, 1980-91

Black and Hispanic Enrollment, Hartford, 1981-91

Black Enrollment - 21 Suburban Districts, 1981-91

Hispanic and Asian Enrollment - 21 Suburban

Districts, 1981-91

Asian Enrollment, Hartford 1981-9.

Table: Black Public Schocl Enrollment, Hartford

and 21 Suburban School Districts, 1980-91

Table: Hispanic Public School Enrollment, Hartford

and 21 Suburban School Districts, 1980-91

Table: Asian Public School Enrollment, Hartford

and 21 Suburban Districts, 1980-91

|

Number and Percentage Change in Public School

Enrollment, Hartford versus 21 Suburban Districts,

1981-91

Number and Percentage of Public Schools Enrollees

by Minority Category in Hartford area: 1981-82

versus 1991-92

Percentage of Minority Students in Hartford Area

Districts, 1980-91

Hartford Public Schools "Early Childhood: A Plan

for Action" (1987)

Hartford Public School: Curriculum Summaries

(1988)

Annual School Report, Betances School (9991)

School Site Visit Report, Betances School (1992)

Annual School Report, Clark School (1991)

School Site Visit Report, Clark School (195)

Annual School Report, Fisher School (1991)

School Site Visit Report, Pisher School (1992)

Annual School Report, Naylor School (1991)

School Site Visit Report, Naylor School (1991)

Annual School Report, Parkville Community School

(1991)

School Site Visit Report, Parkville Community

School (1991)

Annual School Report, Wish School (1991)

School Site Visit Report, Wish School (1992)

Hartford Public Schools Stability and Mobility

Indexes 1989-90 through 1991-92 i

Hartford Elementary Schools, Class Size, 1991-92

(This exhibit may be updated at trial.)

Hartford Public Schools Metropolitan Achievement |

Tests Profiles (1992)

(No exhibit. Not offered.)

Major State Policies and Programs Affecting Public |

Education 1920-1990

Public Elementary School Class Sizes, Hartford and

West Hartford, November 1992

Update to Exhibit 12.16

Elliott Williams Vita

State Department of Education Reorganization Plan

Interdistrict Magnet Schools

Interdistrict Cooperative Grants - 1992-93

Interdistrict Cooperative Grants - 1991-92

Interdistrict Cooperative Grants - 1990-91

.4

Interdistrict Cooperative Grants - 1989-90

Interdistrict Cooperative Grants: Year End Reports

88-89, 89-90, 90-91

Connecticut's Education Agenda (Draft) (1992)

State Department of Education Activities in|

Response to Recommendations Proposed in "Crossing

the Bridge to Equality and Excellence" (Working;

Draft)

Report of the Internal Committee to Study.

Recommendations from the "Forum on Diversity:

Moving Beyond the Dialogue...Community to a Plan"

[Plaintiffs' Ex. 83] (1992)

G. Donald Ferree, Jr. Vita

Special Survey #106 - Governor's Commission on:

Quality and Integrated Education

Special Survey #128 - Survey on Integration -

June-July 1991

Special Survey #130 - Hartford Area Housing Study

Christine Rossell Vita

Hartford Metro Area Expenditure Analysis

Correlations Between Aid/Expenditures and

Indicators of Poverty

Classification of States by State Desegregation

Funding (FY 91)

Classification of States by State Legislation,

Regulation or Board Policy Statements Encouraging

or Requiring School Desegregation or School Racial

Balance (1991-92)

White No-Show Rates at Minority School in Small

and Large Area School Districts

Percent of White Parents Who Would Definitely or

Probably Withdraw Child from Public School if

Reassigned to Minority School v. Actual Percent

Loss

Percentage of White Parents Who Respond They Would

Definitely or Probably Send Child to Private

School or Move Away if Mandatorily Reassigned to.

Minority School

Total Percent Change in White Enrollment from Two

Years Before Implementaion to T+1ll in Large and

Small Area Districts Less Than 35% Minority

Total Percent Change in White Enrollment From Two

Years Before Implementation to T+1ll1l in Large and

Small Area Districts Greater Than 35% Minority

White Enrollment Change as Percent of T-4

Enrollment in Large and Small Districts Less Than

35% Minority

White Enrollment Change as Percent of T-4

Enrollment in Large and Small Districts Greater

Than 35% Minority

White Enrollment Trends in Savannah

Annual Percent White Enrollment Change in New

Castle Co., Delaware

Reanalysis of Orfield's Table 14, "The Status of

School Desegregation” (1992 report)

Pre-Desegregation Percent White (Chart)

Reanalysis of Orfield's Table 14, "The Status of

School Desegregation" (1992 report) Percentage

White Enrollment Change (Chart)

Reanalysis Of Orfield's Table 14, "The Status of

School Desegregation™ (1992 ‘report, 1988 data)

Percent White In School of Typical Black, Actual

(Chart)

Reanalysis of Orfield's Table 14 In "The Status of

School Desegregation: The Next Generation" Report,

to the National School Boards Association (1992)

Reanalysis of Orfield's Table 14, "The Status of

School Desegregation"” (1992 report, 1988 data).

Percent White in School of Typical Black, Adjusted

(chart) i

Reanalysis of Orfield's Table 14 in "The Status of |

School Desegregation: The Next Generation" Report |

to the National School Boards Association (1992)

Reanalysis of Orfield's Analysis in Equity and:

Choice Article Comparing "Most Integrated" and’

"Least Integrated" School Districts

Reanalysis of Orfield, Equity and Choice Article

Comparing "Most Integrated" and "Least Integrated" |

On Pre-Desegregation Percent White (Chart)

Reanalysis of Orfield, Equity and Choice article;

Comparing "Most Integrated" and "Least Integrated"

On Actual and Adjusted Exposure Index (Chart)

(No exhibit. Offered but offer withdrawn)

(No exhibit. Not offered)

Municipal Expenditures in Connecticut, 1980-90

(March 1992)

Budget Watch - A Guide to Connecticut's 1993 State |

Budget (September 1992)

Connecticut Municipal Budgets 1990-1991

-7-

7.10

Connecticut Municipal Budgets 1989-1990

Robert Brewer Vita

State Grants to Hartford Area School Districts:

Summary and Analysis (September 1992)

Regular Program Expenditures in Hartford Area,

1588-89, 1989-90, 1990-91, 1991-92

Analysis of Public Transportation Expenditures in

Hartford Area, 1988-89, 1989-90, 1990-91

Public Transportation Expenditures Per Pupil.

(Excludes Special Education) in Hartford Area, |

1983-84 through 1990-91 |

Special Education Transportation Expenditures Per

Pupil in Hartford Area, 1983-84 through 19¢%¢ 91 i

Total Transporation Expencitures as a Percentage

of Net Current Expenditures in Hartford Area,

1983-84 through 1990-91

Percentage of Pupils Transported in Hartford Area, |

1989-90, 1990-91 |

Analysis of Special Education Expenditures in

Hartford Area, 1988-89, 1989-90, 1990-91

Per Pupil and Percentage Analysis of Expenditures

in Hartford Area, 1979-80 through 1990-91 and:

Twelve Year Cumulative Per Pupil Expenditures

Replication of Plaintiffs' Selected District Three

Year Expenditure Summary

Five Year Composite Analysis of Library Books |

Expenditure Per Pupil and Per School in Hartford

Area, 1986-87 through 1990-91

Analysis of Library Books Expenditures Per Pupil |

and Per School in Hartford Area, 1986-87 through

1990-91

Textbooks, Library Books, Instructional Supplies.

and Equipment, Statewide Combined Total,

Expenditures Per Pupil for 1986-87 through 1990-91

Sorted by Ascending Rank

Number of Public Schools in Hartford Area in 1980

and 1992

Public: Schools in Hartford Area Closed 1981 to

1991

Public Schools in Hartford Area Closed 1971 to!

1991

Construction of Additional Space in Hartford Area

1985 to Present

State Funds for Public Education, 1985-1992

Equalization Aid 1986-1992: Analysis of

Distribution Using Wealth Based Student Quintiles

1990-91 ECS Grant: Need Pupils Analysis

Update to Exhibit 7.1 adding 1991-92 Data.

Education Cost Sharing (ECS) Grant Payments and

Total State Grant Payments (Increases and !

Decreases) for Hartford and Suburban Communities |

1990-91 through 1992-93,

Education Cost Sharing (ECS) Entitlements 1992-93

and Governor's Proposed 1993-94 (Estimates)

Douglas Rindone Vita

Socioeconomic Indicators for Hartford Area: 1980

Census

Socioeconomic Indicators for Hartford Area: 1990

Census

Student Attendance in Hartford Area: 1984-85

through 1991-92

Staff Cost Per Pupil in Hartford Area: 1984-85

through 1991-92

Total Professional Staff Per 1000 Students in

Hartford Area: 1984-85 through 1991-92

Classroom Teachers Per 1000 Students in Hartford

Area: 1984-85 through 1990-91

Support Staff Per 1000 Students in Hartford Area:

1984-85 through 1990-91

Mean Salary of Teachers and Support Staff in

Hartford Area: 1984-85 through 1990-91

Teachers' Starting Salaries (Bachelors Degree) in’

Hartford Area: 1984-85 through 1991-92

Teachers' Salary at Masters Maximum in Hartford.

Area: 1984-85 through 1991-92

Mentors, Assessors, and Cooperating Teachers in.

the Hartford Area: 1991-92

Estimated Minutes Per Week Instructional Time in

Selected Areas, Grades 2, 5, 8: Hartford and

Suburban Communities (Source: SSPs)

Selected Facilities Availability: Hartford and

Suburban Communities (Source: SSPs)

Academic Computers, 8th Grade High School Algebra,

8th Grade High School Foreign Language: Hartford

and Suburban Communities (Source: SSPs)

Staff Professional Development and Professional

Service Time: Hartford and Suburban Communities

(Source: SSPs)

Number of Students Per {1) Instructional

Specialist, (2) Counselor, Social Worker, School

Psychologist, and (3) FTE Administrator: Hartford

and Suburban Communities (Source: SSPs)

Number of Students per FTE Certified Staff and

Stability Rate (Returning Students): Hartford and

Suburban Communities (Source: SSPs)

Selected Primary Assignment Categories

(Developmental Reading, Remedial Reading, Reading

Consultant, School Psychologist, School Social

Worker) 1989, 1990, 1991: Hartford and Suburban

Commuities

Students Per Academic Computer Frequency Table,

Hartford Schools and Schools Statewide

Strategic School Profiles: Terms and Definitions

(June 1992)

Strategic School Profiles: Terms and Definitions:

Addendum (October 1992)

(No exhibit. Not offered)

Statewide Evaluation of the Priority School

District Program - A Second Trienniel Report

1987-1990

Guidelines for the Priority School District

Program September 1989

John T, Flvnn Vita

Environmental Factors Influencing Educational

Program Outcomes: A Review of Research (1992)

David Armor Vita

Chart 1: Achievement Study: Black Poverty Rates

Chart 2: Achievement Study: White Poverty Rates

Chart 3: Achievement Study: Education, Income

and Family Status: Total Population: Hartford

and 21 Suburbs

Chart 4: Achievement Study: Black Sixth Grade

Reading: Hartford and 21 Suburbs

-11-

11.10

11.11

1.12

11.13

11.14

11.15

11.16

11.17

11.18

Chart 5: Achievement

Reading: Hartford and

Chart 6: Achievement

Math: Hartford and 21

Chart 7: Achievement

Math: * Hartford and 21

Chart 8: Achievement

and Family Status:

Five Suburbs

Blacks Only:

Individual Districts

Individual Districts

Study: White Sixth Grade:

21 Suburbs

Study: Black Sixth Grade:

Suburbs

study: White Sixth Grade

Suburbs

Study: Education, Income,

Study:

Five Suburbs

Black Sixth Grade

Chart 9: Achievement

Reading: Hartford and

Chart 10; Achievement Study:

Reading: Hartford and Five Suburbs

Chart "11: Achievement study:

Reading; Six

Area

Chart 12: Achievement Study:

Reading: Six

Area

Chart .13¢

and Bilingual Rates:

Chart - 14:

Grade Reading:

Chart 15:

Grade Math:

Chart: 16:

Chart 17:

Four Year College:

Chart 18:

in Hartford Area (22)

~12

Achievement Study:

Hartford and 21 Suburbs

Achievement

Effects of Racial Isolation

Achievement Study:

Hartford and 21 Suburbs

Achievement Study;

Four Year College (Graphic):

Study; Separating

from SES Factors

Percent Entering

Hartford and]

Black Sixth Grade;

Black Sixth Grade!

in Hartford]

Black Fourth Grade

in Hartford!

Hispanic Poverty!

Hartford and 21 Suburbs |

\

|

Sixth Achievement Study: Hispanic

Hartford and 21 Suburbs

Achievement Study: Hispanic Sixth]

the |

Percent Entering

Individual Districts |

11.19

11.20

11.21

11.22

11.23

11.24

11.25

11.26

13.27

11.28

11.29

Table 1: Achievement study: Percent Entering.

Four Year College (Numerical): Individual

Districts in Hartford Area (22)

(No exhibit. Not offered)

Chart « 2: Commuity Choice Study: Percent of

Hartford Whites Choosing 21 Suburbs Versus Staying

in Hartford

Chart 3: Community Choice Study: Percent of

Hartford Blacks Choosing 21 Suburbs Versus Staying)

in Hartford

Chart 4: Community Choice Study: Percent of!

Hartford Hispanics Choosing 21 Suburbs Versus,

Staying in Hartford

Chart 5: Community Choice Study: Community

Percent Minority, Actual Versus After Community of |

Choice (Graphic): Hartford Area

|

Table 1: Community Choice Study: Community!

Percent Minority Actual Versus After Community of

Choice (Numerical): Hartford 2rea

Analysis of the Crain Project Concern Study:

Tables 1-5.

Hartford Sixth Grade Achievement -- Full sample:

Sensitivity Test for 6th Grade Reading Model]

Excluding Hartford and Predicted 6th Grade Reading]

Scores Using Model Excluding Hartford

District-Level Regression for Black Sixth Grade.

Achievement, Black Family SES, Districts with 10+:

Black Sixth Graders: Predicted and Actual Black |

Reading Scores :

Black Sixth Grade Reading Scores for Communities

with 3+ Black Sixth Graders: Actual Scores and |

Predicted Scores using a Model Excluding Hartford

-13-

11.30

11.31

12.9

District-Level Regression for Black Fouth Grade

Achievement, Black Family SES, Districts with 10+

Black Fourth Graders, Excluding South Windsor:

Predicted and Actual Black Reading Scores

Sample Correlations for Black Achievement, Black

Family SES, Racial Composition, and School

Resources for Communities with 10+ Black Sixth

Graders

State Department of Education Reports (No Erhibit)

Distribution of Non-Whites in Connecticut Public!

Schools (1966)

Preliminary Report on The Distribution of |

Minority-Group Pupils in CT Pub.Sch. 68-69

Racial Imbalance and Regionalization (1969)

A Report Providing Background Information

Concerning the Chronology & Status of Statutes.

Regs. & Process Re: Racial Imbalance in CT:

Schools, 1/84.

A Report on Racial/Ethnic Equity and Desegregation,

in Connecticut's Public Schools 1/88

Crossing the Bridge to Equity and Excellence: A

Vision of Quality & Integrated Education for CT -

Dec. 1990

Minority Students and Staff Report - 1992 and’

91-92 Updates

Connecticut's Challenge - An Agenda For

Educational Equity and Excellence 1/84

Indicators of Success: A Report of Progress in

Implementing the Goals and Objectives of Conn.'s.

Plan for Excellence; 1986-1990 and Memo from

Gerald Tirozzi

-14-

12.

12,

12.

12,

12.

12.

12.

12.

12,

12,

12.

12,

12,

12.

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Indicators of Success: A Report of Prog:ess in

Implementing the Goals and Objectives of Conn.'s

Plan for Excellence: 1991-.395

"Meeting the Challenge, Condition of Education in

Connecticut - Elementary and Secondary" State

Department of Education (1990-91)

"Challenge For Excellence" 1991-1995,

Connecticut's Comprehensive Plan for Elementary,

Secondary, Vocational, Career and Adult Education:

A Policy Plan

Questions and Answers about EERA and the CMT and!

Grade 4 Mastery Test Results Summary and

Interpretations: 1986-86

Report re: Three Perspective on the Educational!

Achievement of CT Students

Special CMT Research Report: Students at Risk:

Academically

Mastery Test Results: Summary and Interpretations.

for Grades 4, 6, 8 - 1991-92 (3 Volumes)

Connecticut Competency Examiniation for

Prospective Teachers (CONNCEPT) & Conncept

Preparations Courses

Teaching Opportunities for Paraprofessionals .

Programs (TOP)

(No exhibit. Not offered)

Dropout Prevention Program Final Evaluation Report

(1988-90)

School contruction grants manual: Procedures for

LEAs (Rev'd 89)

CT Non-public School Enrollment 10/1/91

Compensatory Education Program Evaluation Report

(1992)

-15-

Bilingual Education: State Summary of School

District Evaluation Data for 1989-90 (1992)

Review of Research on School Desegregation's

Impact on Elementary and Secondary School

Students, State Department of Education (1989)

Number of Spanish Dominant Students of the

Hartford Public Schools Who Were Reported as

Eligible for State Mandated Bilingual Education

Programs By School: 1985-86 through 1989-90

A Brief History From 1945 to Present of the Public

School Building Aid Program in Connecticut (1966)

Connecticut Mastery Test Impact Survey (1991-92)

Quality and Integrated Education: Options for.

Connecticut, State Department of Education (1989)

"Next Steps" re: Quality and Integrated:

Education: Options for Connecticut with cover:

memo from Joan Martin to Commission Members

(August 22, 1990)

Hartford Public School Reports (No Exhibit)

"Schools For Hartford', Harvard Graduate School of |

Education (1965)

Summary of Harvard Report (September, 1965)

Background and Discussion Paper on School

Racial/Ethnic Balance, April 1988

Addendum to Background and Disussion Paper on.

School Racial/Ethnic Balance, April 1990

Annual Report of Hartford's Priority School

District Grant Program 1984-85 to 1989-90

Hartford Public Schools Bilingual Education

Programs, Annual Evaluation Report 1990-91

113.7

13.10

113.11

13.12

13813

13.14

13.15

13.16

13.17

13.18

13.19

Number of Limited English Proficient Students

Eligible for a State-Mandated Bilingual Education

Program for School Year 1991-92 and Hartford

Public Schools Breakdown on School-by-School

Basis.

"Vision of Excellence," Hartford Public Schools,

Annuali Report 1991-92

Group Test Results, Hartford Public Schools:

1990-91

Comparison of City-Wide Metropolitan Achievement:

Tests Scores 1989-1990 : 1990-1991 |

Matched Scores Report of City-Wide Metropolitan:

Achievement Tests Scores 1989-1990 : 1990-1991

Bilingual Education Program Evaluation Reporting]

Form: Hartford 1989-90 i

Hartford Public Schools 1990 Metropolitan!

Achievement Test Scores, Grade 2, Reading

Hartford Public Schools 1990 Metropolitan

Achievement Test scores - Grade 9 Reading

Spanish Assessment of Basic Education (SABE) Grade

6 Average Reading NCE Scores and Explanation of:

Lower Test Scores in Upper Grades

Teachers Bargaining Unit Salary Census, Hartford

Letter from Hartford Superintendent Hernan

LaFontaine to Commissioner Gerald N. Tirozzi re:

Priority School District Program in Hartford (with

attached report) August 9, 1990 |

Vita of Robert J. Nearine

An Evaluation of the 1976-1977 Hartfcrd °roject

Concern Program: Edward F. 1Iwanicki, Robert K. |

Gable, University of Connecticut

-17-

14.5

14.6

14.9

14.10

14,11

Final Evaluation Report: 1984-85 Hartford Project

Conern Program: Edward F. Iwanicki, Robert K.

Gable, University of Connecticut

Annual School Report, Quirk Middle School (1991)

School Site Visit Report, Quirk Middle School

(1992)

Annual School Report, Weaver High School (1991)

School Site Visit Report, Weaver High School.

(1992) :

School District Profiles:

(No Exhibit)

Hartford Area, 1991-92.

1991-92 Strategic School District Profile - Avon

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Bloomfield

1991-92 Strategic School District Profile - Canton

1991-92 Strategic School District Profile - East.

Granby

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - East

Hartford

91~32 Strategic School District Profile =

Ellington

91-92 Strategic School District Profile =}

Farmington

91-92 Strategic School District Profile =

Glastonbury

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - Hartford:

91-92 Strategic school District Profile po}

Newington

81-92 Strategic School District Profile ~ Rocky |

Hill :

-18-

16.1

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - Simsbury:

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - South.

Windsor

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - Suffield

91-92 “Strategic School District Profile - Vernon

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - West

Hartford

91-92 Strategic School District Profile ne

Wethersfield

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - Windsor

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - dindsor

Locks !

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - Granby

31-92 Strategic School District Profile - East

Windsor |

91-92 Strategic School District Profile -_

Manchester |

Avon Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Roaring Brook

School !

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Avon High School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Avon Middle

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Pinegrove School

Bloomfield Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile =~ J.P. Vincent |

School :

-19-

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Metacomet School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Laurel School

91-92 Strategic School Profile =~ Carmen Arace

Middle School

91-92 “Strategic School Proiile - Bloomfield Junior

High

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Bloomfield High;

School |

Canton Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Canton High!

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Canton |

Intermediate School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Canton Elementary

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Cherry Brook:

School

East Granby Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - East Granby High

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - East Granby

Middle School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - R. Dudley Seymour

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Allgrove School

East Hartford Schools (No Exhibits)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Transitional!

Education Program

-20-

91-92 Strategic School Profile - East Hartford

Middle

91-92 Strategic School Profile - East Hartford

High

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Joseph 0. Goodwin

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Hockanum School

91-92 ' Strategic School Profile ~~ "Dr. ‘John A.

Langford School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Dr. Franklin H.

Mayberry

91-92 Strategic School Profiel - Anna E. Norris.

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Robert J. O'Brien

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Dr. Thomas SS.

O'Connell School

91-92 Strategic School Profile ~~ Governor W.M.

Pitkin School

91-92 Strategic School Profile ~ Silver Lane

School

Ellington Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Center School

91-32 Strategic School Profile ~ Crystal Lake

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Windermere School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Longview Middle

School

91-392 Strategic School Profile - Ellington High

School

Farmington Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Farmington High

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Irving A. Robbins

Middle School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Noah Wallace.

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - East Farms School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Union School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - West District

School

Glastonbury Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Gideon Wells

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Academy School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Buttonball Lane

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Hopewell School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Eastbury School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Hebron Avenue

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Naubuc School

Hartford Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - South School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Barbour School

-22-

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Batchelder School

91-92 Strategic School Profile =~ Barnard-Brown

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Ramon E. Betances

School

|

81-92 Strategic School Profile - Bukeley High

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Burns School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Ramon E. Betances.

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Clark School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Dwight School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Fisher School

91-92 Stratetic School Profile - Fox School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Dr. Michael D.

Fox Elementary School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Hartford Public

High School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Hooker School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Kennelly School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Kinsella School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - King School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Naylor School

91-92. Strategic School Profile =~ Thomas J. |

McDonough School |

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Parkville

Community |

Se

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Milner School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Rawson School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Quirk Middle

School

9]-92 Strategic School Profile - S.A.N.D.

Everywhere School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Simpson-Waverly

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Mark Twain School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Weaver High

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Webster School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - West Middle

School |

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Wish School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Burr School

Newington Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Newington High

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - John Wallce

Middle School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Martin Kellogg

Middle School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Anna Reynolds:

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Elizabeth Green

School }

91-92 Strategic School Profile - John Paterson

School

-24-

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Ruth Chaffee

School

Rocky Hill Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Dr. Oran A. Moser

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Myrtle H. Stevens

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - West Hill School

81-92 Strategic. School Profile ~ ‘Albert " D.

Griswold Jr. High

91-392 Strategic School Profile - Rocky Hill High

School

Simsbury Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Central School

91-92 (Strategic School Profile ~- Latimer Lane

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Squadron Line

School

91=92 . Strategic School Profile - - Tariffville

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Tootin' Hills

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Henry James

Memorial School

91-92 Strategic School Profile ~~ Simsbury High!

School

South Windsor Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Eli Terry School

-25-

28.5

29.0

29.1

29.4

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Timothy Edwards

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - South Windsor

High School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Orchard Hill

Schoo?

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Philip R. Smith

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Pleasant Valley

School

Suffield Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Bridge Street.

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - A. Ward Spaulding

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - McAlister Middle

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Suffield High

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Black Rock School

Vernon Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Rockville High

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile ~- Center Road!

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Lake Street

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Maple Street

School

-26-

30.10

30.41

30.12

30.13

30.14

31.0

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Northeast School

91-92 "Strategic School Profile ~~ Skinner Road

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Vernon Center

Middle

West Hartford Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Aiken School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Braeburn School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Bugbee School

91-92 Strategic School Profile ~- Charter 0ak

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Duffy School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Morley School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Norfeldt School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Webster Hill

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile ~~ Whiting Lane

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Wolcott School

91-92 Strategic School Profile =~ Conard High

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Hall High School

91-92 Strategic School Profile =~ Ring Philip

Middle

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Sedgwick Middle

School

Wethersfield Schools (No Exhibit)

-27-

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Webb Kindergarten

Center

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Emerson-Williams

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Alfred W. Hanmer

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Highcrest School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Charles Wright

School : |

91-92 Strategic School Profile ~ Silas Deane

Middle School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Wethersfield High

School

Windsor Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Clover Street

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - John PF. Kennedy

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Oliver Ellsworth

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Poquonock School

1

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Sage Park Middle

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Windsor High

School

Windsor Locks Schools (No Exhibit}

91-92 Strategic School Profile - North St. School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - South St. School

36.0

36.1

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Windsor Locks

Middle School

91-92 Strategic School Profile ~~ Windsor Locks

High School

Granby Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School District Profile

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Granby Memorial.

High School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Memorial Middle.

School |

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Frank M. Kearns |

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Kelly Lane School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Wells Road School

East Windsor Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School District Profile - East.

Windsor School District

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Broad Brook

Elementary School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - East Windsor’

Senior High School i

91-92 Strategic School Profile - East Windsor

Junior High School

91-92 Strategic School Profile East Windsor

Intermediate School

Manchester Schools (No Exhibit)

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Regional

Occupational Training Center

-29-

36,2

39

40

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Manchester High

School

81-92 Strategic: School Profile - 111ing Junior

High School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Bennett Junior

High School

91-92 Strategic School Profile Washington School

91-92 Strategic School Profile Waddell School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Verplanck School

91-92 Strategic School Profile Robertson School

S1-32 Strategic School Profile - Nathan Hale

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Martin School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Kenney School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Buckley Scnool

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Highland Park

School

91-92 Strategic School Profile - Bowers School

8/21/92 Letter from John Brittain to Carmen

Rodriguez, President, Hartford Board of Education |

"Five Million Children: A Statistical Profile of |

Our Poorest Young Citizens" National Center for ;

Children in Poverty, School of Public Health,

Columbia University

"Five Million Children 1991 Update"

State Department of Health Services Data on Infant

Mortality, Low Birthweights and Teen Births

1978-80 through 1985-87.

-30-

41

Maternal and Infant Health 1981-1988 Connecticut

Department of Health Services, Division of Health

Surveillance and Planning

CICS Drug Clients Served & UCR Drug Arrest Data,

Greater Hartford Area

Report’ of Governor Lowell P. Weicker, Jr.,

"Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward Meeting

the National Education Goals", 10/2/91

Elementary Classes By Size in Connecticut Public

Schools, CPEC (April 1990)

City and State, November 16, 1992 (Offered but not

admitted. Exception noted)

FOR THE DEFENDANTS

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL

ATTORNEY GENERAL

Zz

A 7

7 ’ / A / / A 2 7

./ 4 if j /y J a

By: A gl Ans

John R. Whelan - Juris 085112

Assistant Attorney General

110 Sherman Street

Hartford, Connecticut 06105

Tel. 566-7173

j /

By: Wa Zr Pid : 7 Vd aT nae

Martha M. Watts - Juris 406172

Assistant Attorney General

110 Sherman Street

Hartford, Connecticut 06105

Tel. 566-7173

-31-

i

7

i

¥d

hot

|

CERTIFICATION

This is to certify that on this 26th day of February, 1993 a

(copy of the foregoing was mailed to the following counsel of

record:

John Brittain, Esq. Wilfred Rodriguez, Esq.

University of Connecticut Hispanic Advocacy Project

School of Law Neighborhood Legal Services

65 Elizabeth Street : 1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, Cr 06105 Hartford, CT*' 06112

Philip Tegeler, Esq. Wesley W. Horton, Esq.

Martha Stone, Esq. Moller, Horton &

Connecticut Civil Fineberg, P.C.

Liberties Union 90 Gillett Street

32 Grand Street Hartford, CT 06105

Hartford, CT 06105

Ruben Franco, Esq. Julius L. Chambers, Esq.

Jenny Rivera, Esq. Sandra Del Valle, Esq.

Puerto Rican Legal Defense Ronald Ellis, Esq.

and Education Fund NAACP Legal Defense Fund and

99 Hudson Street Education Fund, Inc.

l4th Floor 99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013 New York, NY 10013

John A. Powell, Esq.

Helen Hershkoff, Esq.

Adam S. Cohen, Esq.

American Civil Liberties Union

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

id /

a / nd

John R. Whelan

Assistant Attorney General

JRW0442AC

-32-