Defendants' Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Public Court Documents

July 6, 1976

41 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Defendants' Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 1976. b4b86f54-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc0b9391-69b6-4177-9807-4c98ef0048c1/defendants-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

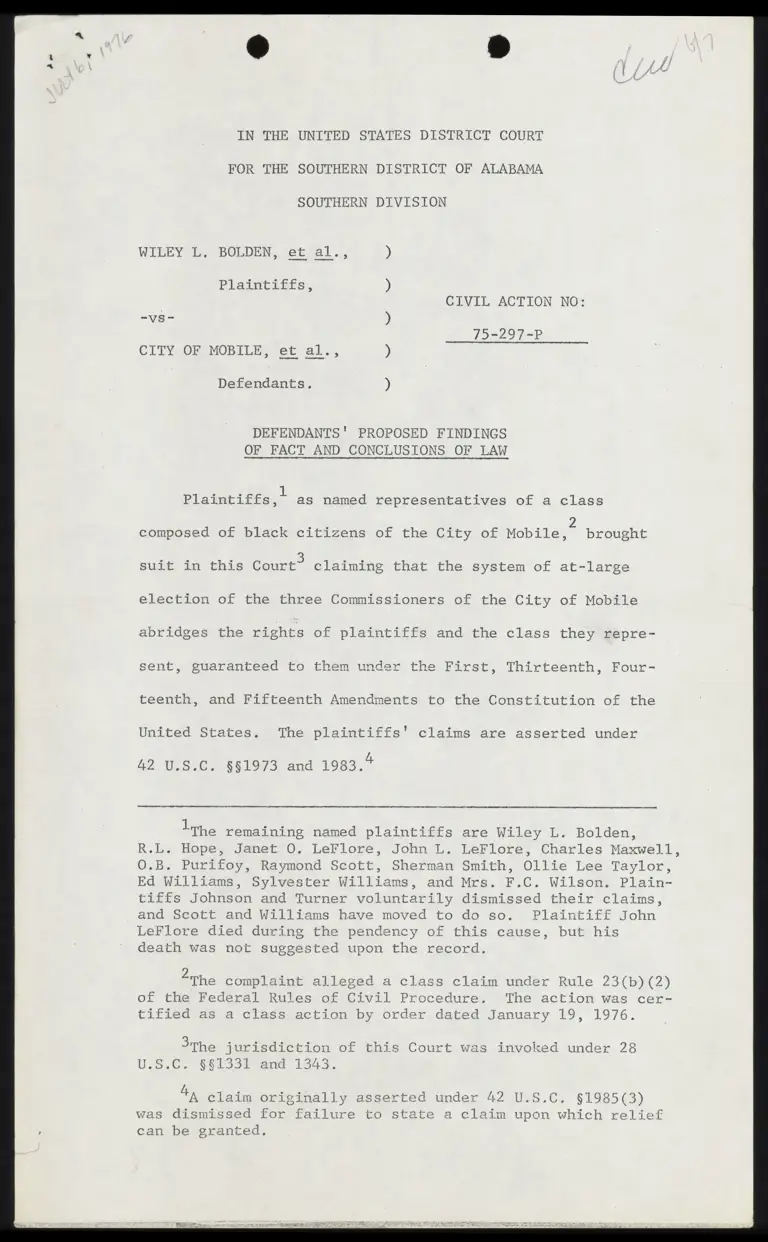

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

CIVIL ACTION NO:

-vS -

75-297-~P

CITY OF MOBILE, et al.,

N

l

gl

0

a

g

g

S

N

Nu

ll

Defendants.

DEFENDANTS' PROPOSED FINDINGS

OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

Plaintiffs, as named representatives of a class

composed of black citizens of the City of Mobile, brought

sult in this Court’ claiming that the system of at-large

election of the three Commissioners of the City of Mobile

abridges the rights of plaintiffs and the class they repre-

- sent, guaranteed to them under the First, Thirteenth, Four-

teenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States. The plaintiffs' claims are asserted under

42 U.S.C. §§1973 and 1983.2

Lhe remaining named plaintiffs are Wiley L. Bolden,

R.L. Hope, Janet O. LeFlore, John L. LeFlore, Charles Maxwell,

O.B. Purifoy, Raymond Scott, Sherman Smith, Ollie Lee Taylor,

Ed Williams, Sylvester Williams, and Mrs. F.C. Wilson. Plain-

tiffs Johnson and Turner voluntarily dismissed their claims,

and Scott and Williams have moved to do so. Plaintiff John

LeFlore died during the pendency of this cause, but his

death was not suggested upon the record.

Z oa as : : Ar

The complaint alleged a class claim under Rule 23(b) (2)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The action was cer-

tified as a class action by order dated January 19, 1976.

3The jurisdiction of this Court was invoked under 28

U.S.C. 5581331 and 1343.

Z : a ; . be A

A claim originally asserted under 42 U.S.C. §1985(3)

was dismissed for failure to state a claim upon which relief

can be granted.

> and each of the Defendants are the City of Mobile

Commissioners of the City of Mobile,® Gary A. Greenough,

Robert B. Doyle, Jr., and Lambert Mims.

Plaintiffs seek a declaratory judgment that the at-

large election of City Commissioners violates the Consti-

tution of the United States, and seek also an injunction

against any city election under the present plans’ Plain-

tiffs also seek to have defendants enjoined ''from failing

to adopt" a single-member city government plan.

he City of Mobile is sued only under 42 U.S.C. $1973.

Claims against it based upon 42 U.S.C. §1983 and 1985(3)

were dismissed by order of the Court on November 18, 1975.

® he three Commissioners are each sued in their indi-

vidual and official capacities. C. WRIGHT, LAW OF FEDERAL

COURTS §48 (1970).

’plaintiffs seek, in effect, an injunction against the

enforcement of parts of ALA.CODE tit. 37, §89 et.seq., the

present codification of Act 281 of the 1911 Alabama Legis-

lature, as amended. Specifically, the at-large feature is

contained in ALA.CODE tit. 37, §96. Mobile has been governed

by the provisions of Act 281 (as amended) since 1911.

Hartwell v. Pillans, 225 Ala. 685, 686, 145 So0.148(1949).

While Act 281 was a general act, Baumhauer v. State, 240

Ala. 10, 12, 198 S0.272(1940), it is impossible to tell

what cities other than Mobile, if any, have elected to be

governed by the statute. There are intimations that Act

281 (or at least parts of it) constitute a general law of

local application. Cf. State v. Baumhauer, 239 Ala. 476,

195 S0.869(1940). While the statute purports to be general

in nature, no Three-Judge Court need be convened because

(1) injunction is sought only against local officials, and

(2) the statute is of local impact, solely (or at least

principally) in Mobile. Bd. of Regents v. New Left Edu-

cation Project, 404 U.S. 541, 544(1972); Moody v. Flowers,

387 U.S. 97(1967). This case is much more fundamentally

"jocal' than Holt Civic Club v. City of Tuscaloosa, 525

F.2d 653 (5th Cir. 1975), where plaintiffs were a class of

all Alabama residents who lived in police jurisdictions

‘surrounding cities, where the statute was genuinely state-

wide in application, and where local officials were sued

only because they were the only officials who could enforce

the statute in the various Alabama cities.

8pefendants moved to strike this claim for relief

upon the ground that they had no power to adopt a single-

member plan, since only the state legislature has such

power. The motion was denied at that stage of the case.

I. CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

A. Necessity of Discriminatory Purpose: Shortly be-

fore the trial of this case, the United States Supreme Court

decided Washington v. Davis, U.S, , 44 U.S.1L.W. 4789

(U.S. June 7, 1976), making clear that in order for a court

to declare a statute unconstitutional by reason of its

being ''racially discriminatory', the statute must first be:

1 proved to have a racially discriminatory purpose". ——————

U.S. at , H4 4.8. L.Y, at 4792 (emphasis added). Washing-

ton v. Davis thus clarified an issue which a number of

cases-~including multi-member districting cases--had left

as "somewhat less than a seamless web'. Beer v. United

States, 0.8. , 47 L.E4.24 629, 643 n.4(1976) (dissent).

While Washington technically involved equal protection analy-

sis oily 0 the Court made quite clear that it was announcing

a broad principle of constitutional law, including the

Fifteenth Amendment as well. Writing that '"[t]he rule is

The holdings of several courts were unclear on the neces-

sity of a showing of discriminatory purpose. The Supreme Court

in Chavis v. Whitcomb, 403 U.S. 124, 149 (1971), seemed to re-

quire proof of or inatory purpose ['"purposeful', '"designed"].

See Graves v. Barnes, 378 F.Supp. 640, 665(W.D.Tex. 1974) (dissent),

opinion on remand of White v. Regestey, 412 U.8.755(1973). The

Fifth Circuit in 1974 wrote that'[i]t is unclear whether di-

lution of a group's voting power is unconstitutional only if

deliberate..." Reese v. Dallas County, Ala.,505 F.2d 879, 886

(5th Cir.1974) ,rev'd other grounds, 421 U.S.477(1975). But

the Fifth Circuit earlier had seemed to say that effect had

greater relevance than did purpose. Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485

F.2d 1297, 1304 n.16(5th Cir.1973) (en banc), aff'd sub.nom.

East Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, U.S.

(March 8, 1976) (where the Supreme Court ata that its affirm-

ance was "without approval of the constitutional views expressed

by the Court of Appeals'').

10:6 case involved the operation of the police department

of the District of Columbia, which is not a '"'state' bound by

the strictures of the Fourtee nth Amendment. However, as the

Washington Court noted, it was held shortly after Brown v.

Bd.of Educ. "that the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amend-

ment contains an equal protection component prohibiting the

United States from invidiously discriminating between indi-

viduals or groups. Bolling v, Sharpe. %7 U.8.491954)".

U.S. at , B.S. NW. st 4752

TR

# i »

the same in other contexts', Washington specifically reaf-

firmed Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52(1964), a case re-

quiring proof of discriminatory purpose where voting districts

were alleged to have been racially gerrymandered in contra-

vention of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment rights

of black plaintiffs. _ U.S. at ___, 44 U.8.L.W. at 4792.

That the rule of Washington v. Davis obtains in a multi-

member district voting dilution case has also quite recently

been recognized in the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama, in Rev. Charles H. Nevett v.

Lawrence G, Sides, et al,, C.A. 73~P~-529-8 (Order of June 11,

1976). While that case will be discussed in more detail

11 it is informative here that after Judge Pointer made infra,

specific factual findings for the defendant city, he also

added that "It may be noted that there has been no evidence

that the claimed 'dilution' was the result of any invidious

discriminatory purpose. Cf. Washington v. Davis..." Id.

Therefore, the Alabama statute attacked by plaintiffs

in the instant case is not due to be held unconstitutional

unless its enactment was motivated by a racially discrimina-

tory purpose. 12

; priefly, that case involved a suit quite similar to this

one, involving multi-member districting in the City of Fair-

field. After the District Court found for the plaintiff in

an unreported decision, the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit reversed for more specific factual

findings on the factors outlined in Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485

F.2d 1297(5th Cir.1973). Nevett v. Sides, ¥.24.

(5th Cir. June 8, 1976). On remand the District Court found

for the city the day after receipt of the mandate. Nevett

v. Sides, B.Supp, = AN.D, Ala. June 11, 1976).

129he fact that the city government statute is said to

violate 42 U.S.C. §1973(c), as well as the Constitution it-

self, does not change the result. The statute tracks the

language of the Fifteenth Amendment and is "constitutional

in nature". Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 634 n.17(5th

Cir.1975), vacated on other grounds, 0.5. 7. 47 1.54,

2d 296(1976).

Whatever may have been the dicta, or even the holdings,

of Fifth Circuit and lower court cases that pre-date Washington,

it is now certain that evidence of discriminatory effect is

relevant and admissible only for whatever light, if any, it

may cast upon purpose--the decisive issue.

B. Burden of Proof and Standing. The plaintiffs,

of course, have the burden of proof:

The plaintiff's burden is to produce

evidence to support findings that the

political processes leading to nomina-

tion and election were not equally open

to participation by the group in ques-

tion-~that its members had less oppor-

tunity than did other residents in the

district to participate in the politi-

cal processes and to elect legislators

of their choice.

White v. Rezester, 412 U.S. 755, 766(1973).

1. Plaintiffs Must be an Identifiable Segment

of the Population. As an initial matter, plaintiffs have

the burden of proving that they constitute under the pre-

sent facts an identifiable class for Fourteenth Amendment

purposes. While dilution cases such as this are most com-

monly brought by blacks, membership in the Negro race is

not talismanic; nor is the doctrine reserved exclusively

for blacks. The Supreme Court in one recent case held

that blacks as such did not constitute an identifiable

class; under the circumstances of that case blacks were

held to be not dissimilar from non-black Democrats, for

example:

[TlThe interest of the ghetto resi-

dents in certain issues did not

measurable differ from that of

other voters.

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 155(1972) (claim of dilu-

tion ''seems a mere euphemism for defeat at the polls', id.

at 153).

The Supreme Court has long suggested that the dilution

doctrine extends to political as well as racial elements of

the population, 13 and has indicated strongly that blacks

need not necessarily fare better under the Constitution

than, for example, 'union oriented workers, the university

community, or religious or ethnic groups occupying identifi-

able areas of our heterogeneous cities and urban areas'.

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 156(1971). In order to

invoke the benefit of the dilution doctrine, blacks must

prove more similarity than mere blackness. As one post-

Chavis commentator wrote:

After all, if Republicans could have

elected someone more sympathetic to

their views in the absence of a mul-

timember district, are they not suf-

fering the same harm blacks suffer...?

Certainly in the case of de facto

racial submergence, where racial in-

tent is not shown, blacks are not suf-

fering because they are black,

Carpeneti, Legislative Apportionment: Multi-member Dis-

tricts and Fair Representation, 120 U,PA.L.REV.666, 698(1972).

2. Mere Showing of Adverse Impact Has Never Met

the Burden. Even prior to the decision of the Supreme Court

in Washington v. Davis, a plaintiff could not meet his bur-

den by showing a mere adverse impact, but had to prove more:

The critical question under Chavis and

Regester is not whether the challenged

political system has a demonstrably ad-

verse effect on the political fortunes

of a particular group, but whether the

effect is invidiously discriminatory,

that is, fundamentally unfair.

LBg.e., Burns v. Richardson, 384

9 : Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 733, 739(1965).

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 630 (5th Cir. 1975), vacated

& remanded on other grounds, u.s. yoh7 L.Bd,.24

rps ——

296(1976) (per curiam) (emphasis added).

3. No Constitutional Right to a Black District.

plaintiffs have no constitutional right to a politically

safe black district. The Fifth Circuit has recently reit-

erated that the Supreme Court's pronouncements reject such

a "guaranteed district' concept:

Chavis and Regester hold explicitly that

no racial or political group has a con-

stitutional right to be represented in

the legislature in proportion to its num-

bers, so it follows that no such group is

constitutionally entitled to an apportion-

ment structure designed to maximize its

political advantages. ..Neither does any

voter or group of voters have a constitu-

tional right to be included within an

electoral district that is especially

favorable to the interests of one's own

group, or to be excluded from a district

that is dominated by some other group.

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 630 (5th Cir. 1975), vacated

& remanded on other grounds, 0.8. y 47 5.84.24

296(1976). Accord, Vollin v. Kimbel, 519 7.24 790,791

(4th Cir. 1975) (''black voters are not constitutionally en-

titled to insist that their strengh as a voting bloc be

preserved''), cert.denied, de 1976); Cherry v.

County of New Hanover, 489 F.2d 273, 274(4Lth Cir. 1973)

(blacks '""do not have a constitutional right to elect mem-

bers of their race to public office’).

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Court

in the Fairfield case, in reversing the holding of the

District Court, recently held that:

the trial court's findings may be

read as indicating that elections

must be somehow so arranged--at any

rate where there is racial bloc vot-

ing~~that black voters elect at least

some candidates of their choice re-

gardless of their percentage turnout.

This is not what the Constitution

requires.

Nevett v. Sides, F.2d ; (5th Cir.June 5, 1978),

Plaintiffs in order to prevail have always had to show,

as Wallace v. House indicates, that the system is ''fundament-

ally unfair". 515 F.2d at 630. Now, after Washington v.

Davis, they must show (1) that the system is ''fundamentally

unfair", and (2) that it was intended to be so.

C. Evidentiary Factors to be Considered in Deciding

Whether Political Process Open. Cases decided prior to

Washington developed a number of evidentiary criteria to

be considered upon the principal issue raised by White=--

whether "the political processes leading to nomination and

election" are "equally open'. White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

at 766. These criteria (being pre-Washington) relate to

effect only, and have been variously stated from time to

time and from case to case, and even from Court to Court. 1%

As formulated in Zimmer, these indicia of discrim-

inatory effect comprise "a panoply of factors'. Proof of

LA] "an aggregate of these factors' may suffice to prove effect,

L4G ommentators analyzing the Fifth Circuit's en banc

decision in Zimmer v. McKeithen have suggested that a civil

rights plaintiff may more easily prevail under the Zimmer

criteria than under the Supreme Court cases which Zimmer

purported to follow. See, e.g., Note, 87 HARV.L.REV. 1851,

1858(1974); Note, 26 ALA.L.REV, 163, 170(1973). Support is

lent to this by the pointed remark of the Supreme Court in

tutional views expressed by the Court of Appeals'. East

Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, U.S. (March Sor ———

8, 1976), aff'a Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir,

1973) (en banc).

485 F.2d at 1305; the stated factors do not include intent,

since Zimmer preceded Washington. These factors were in

Zimmer divided further into what may be termed "primary"

and "enhancing" factors. Id.

1. "Primary" Factors. The following factors from

Zimmer were h21d in that case to be indicia of dilution of

the votes of blacks [id. at 1305]:

(a). "Lack of access to the process of slat-

ing candidates";

(b). "unresponsiveness of legislators to P B

their [blacks'] particularized interests'';

c). "a tenuous state policy underlying the p y ying

reference for multi-member or at-large districting'; P 2 g 3

(d). "the existence of past discrimination

in general precludes the effective participation in the & P : p Pp

election system".

2. "Enhancing' Factors. Zimmer also says that proof

of dilution made out by a showing of the above-enumerated fac-

tors may be "enhanced by" [id. at 1305] the following factors:

(a). "the existence of large districts";

(b). "majority vote requirements’;

(¢). "anti-singleshot voting"

(d). "the lack of provision for at-large can-

didates running from particular geographical subdistricts'.

Because these factors have been explicitly followed

i>

in later (but pre-Washington) Fifth Circuit decisions,

Lyevert v. Sides, F.2d (Bth Cir: June 8, 1976);

Perry v. City of Opelousas, 515 ¥.2d 639(5th Cir. 1973);

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619(5th Cir. 1975); Turner .v.

McKeithen, 490 F.2d 191(5th Cir. 1973). Nevett was decided

EE set nt

the dav after Washineton. but contains no mention of it.

"3 () oo

<10~

they will be the basis here of factual findings on effect,

notwithstanding any differences between Zimmer and Supreme

Court pricedent 0 Thus, the findings of fact will princi-

pally follow the dictates and factors stated in both

Washington v. Davis (intent) and Zimmer v. McKeithen (indicia

of effect), keeping in mind that "unless [the Zimmer] cri-

teria in the aggregate point to dilution..., then plaintiffs

have not met their burden, and their cause must fail,

Nevett v. Sides, F.2d (5th Cir.1975),

D. Present Form of Government, 1965 Voting Rights

Act, and Act 832. Since 1911, the City Commission form of

government has obtained in Mobile, with three commissioners

required by statute to be "elected from the city at large’.

Ala. Acts No. 281(1911) [now principally codified as ALA.

CODE tit. 37, §89 et seq.]. As originally provided by

statute, the three commissioners upon their election would

elect from their number a mayor, and apportion among them-

selves the administrative tasks of the City. With some

minimal modification over the years, the commission form of

government, with its at-large feature [ALA.CODE tit. 37, §96]

has remained susbtantially unchanged.

One present feature of at least peripheral interest

in this case is Act 823 of the 1965 Alabama Legislature, en-~

acted not as an amendment to title 37, section 89 et seq.

165ee note 14 supra. The Three-Judge District Court on

the remand of White v. Regester formulated the factors in-

volved in a different and slightly less Procrustean fashion

than appeared in Zimmer and its progeny. See Graves Vv.

Barn

s, 378 F.Supp. 640, 643(W.D.Tex.1974), on remand of 2

1 th

——

White v. Regester, 412 1.8. 755(1973).

wl]

[old Act 281], but instead as a general act of local appli-

17 cation’ covering only the City of Mobile. Act 823 echoed

earlier, short-lived amendments in providing an apportion-

ment of specific tasks A WI comtastionere Act

823 assigned specific tasks to numbered commission posts

(Finance and Administration, Public Safety, and Public Works

and Services), and also provided for a scheduled rotation of

the largely ceremonial mayoralty. There had been numbered

posts since 1945. ALA.CODE tit. 37, §94.

Act 823 did not change or alter the at-large feature

here under attack.

However, because of the peripheral involvement of Act

823 in this case, some mention should be made of its re-

lationship to Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, 42

U.S.C. §1973(c). -Because plaintiffs are found herein to be

not entitled to relief under the standards of Zimmer and

other dilution cases as modified by Washington v. Davis,

177he frequent Alabama use of the so-called ''general

law of local application' is described in Adams, Legisla-

tion by Census: The Alabama Experience, 21 ALA.L.REV, 401

(1969). The .Three~-Judge Court ramifications of that prac~

tice are discussed in note 7 supra.

18 :

In 1939, Act 289 was introduced by Mr. Langan and

passed, providing for election of the Mayor for that speci-

fic office, and also providing a specific apportionment of

the tasks of administration among the two associate commis~

sioners. It was declared unconstitutional the next year

for repugnancy to legislative requirements (procedural in

nature) under the Alabama constitution. State v. Baumhauer,

239 Ala. 476, 195 So. 869(1940). Almost immediately there-

after the same basic provision was re-enacted in the general

codification of 1940, ALA.CODE tit. 37, §95(1%40). One

associate commissioner was assigned the fire, police, health,

and sewer departments, while the other was assigned parks,

docks, streets, public buildings and the city airport. The

majority of the Board of Commissioners assigned to each

associate commissioner one set of tasks. In 1945, this

procedure was abandoned. Ala. Acts No. 295(1945).

12

it is not necessary in this case that an adjudication be had

concerning the coverage of Act 823 by §5 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1945, %7 If such an adjudication were neces-

sary, of course, a Three-Judge District Court would have

been required to determine that issue. Allen v. Bd. of

Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 563(1969); United States v. Cohan,

470 F.2d 503, 505(5th Cir.1972). Whatever the current

status of Act 823 under the 1965 Voting Rights Act, no deter-

mination of the problem need be made in this case, and, in

any event, could not be made by a single judge.

Since this case can be disposed of upon the basis of

issues which can be decided by a single judge without trans-

Pact 823 was enacted shortly after passage of the 1965

Voting Rights Act, and was not at the time submitted to the

Department of Justice. On May 14, 1975, the City of Mobile

submitted to the Justice Department five statutes of the 1971

Regular Session of the Alabama Legislature for approval

under §5 of the Voting Rights Act. On July 14, 1975, the

Justice Department wrote the City to ask that Act 823, which

had been minimally amended by one of the 1971 enactments, be

submitted for approval under §5. On December 30, 1975, the

City submitted Act 823 "without prejudice to the right of

the City to continue to insist upon its position that Act

823 is not within the scope of the Civil Rights Act of

1965." On March 2, 1976, the Department of Justice inter-

posed objection to portions of Act 823, upon the rationale

that since the City was contending in this litigation that

Act 823 made the imposition by this Court of single-member

districting inappropriate, Act 823 was invalid since it

"rigidifies use of the at-large system''. On March 5, 1976,

counsel for the City wrote the Department of Justice re-

iterating the City's position that Act 823 was without the

coverage of §5, and specifically by copy inviting plaintiffs

in this action "to bring an appropriate legal action to

determine the matter, if they are disposed to contend that

it is unenforceable'. Neither plaintiffs herein nor the

Department of Justice have done so; nor has the City in-

stituted a declaratory judgment action under §5 in the

United States District Court for the District of Columbia.

No supplemental claim raising the issue has been filed in

this action. This Court of course intimates no view on the

issue of coverage of Act 823 by §5 of the 1965 Voting Rights

Act. See generally Beer v. United States, D.S. :

47 L.EE.24 629{1975).

<13=

gressing upon the jurisdiction of a Three-Judge Court, it

is appropriate for this Court to so decide the issues. MIM

v. Baxley, 420 U.S. 799, 806-07(1975) (concurring opinion);

Hagans v. LaVine, 415 U.S. 528(1974).

ITI. FINDINGS OF FACT

A. Identifiable Segment. This Court elects to pre-

dicate its decision upon the merits, and there is therefore

no reason to spend an undue amount of time upon the issue of

whether or not plaintiffs under the facts of this case con-

stitute an identifiable segment of the population. Despite

the existence of a creditable body of evidence in the record

indicating that Mobile blacks are no longer for certain

political purposes to be regarded as an identifiable seg-

ment of the population, 2S this Court, in order to reach

the merits, holds that blacks in Mobile constitute an iden-

tifiable segment of the population for Fourteenth Amendment

purposes.

Bh Purpose. Under Washington v. Davis, plaintiff must

prove that the statute involved was enacted or instituted to

further a discriminatory purpose.

The statute under attack in this Court, setting up

the at-large facet of government which still obtains in

Mobile, was passed by the Alabama legislature in 1911. ALA,

CODE tir. 37, 396,

For example, the testimony of Dr. James E. Voyles, an

expert for defendants, indicated that black/white political

scisms of the 1960's were an aberrant product of the civil

rights struggle during that period, and that black/white

scismatic voting trends have been significantly (if not yet

entirely) reduced. Similarly, the answers of the named

plaintiffs to interrogatories indicate many examples of iden-

tity of black/white views, thus reducing the number of issues

upon which the blacks have ''particularized needs'. See, e.g. bh

Answers of Plaintiffs to Defendants' Interrogatories 67-114.

. 14- »

This Court finds that neither §96 nor Act 281 as

a whole was enacted for a discriminatory purpose. In 1911,

the Negro vote played no part in elections in Mobile, as

the evidence clearly shows. Blacks had been overtly dis-

franchised prior to that time 2} a fact plaintiffs do not

dispute. Under such circumstances, any contention that the

adoption of Act 281 was racially motivated is unsupportable,

This finding, that the enactment of Act 281 had no

racial purpose, echoes similar findings in other courts deal-

ing with other Southern states. The Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit in Wallace v. House held that when the at-

large election system was first passed in Louisiana in 1898,

"there could have been no thought that the device was racially

discriminatory, because very few blacks were allowed to vote

in Louisiana during that period". 515 F.2d at 633. Judge

Wisdom made a similar observation in Taylor v. McKeilthen,

finding that prior to the 1965 Voting Rights Act,

blacks could not be elected to [public

officel-~to be blunt-~-because there

were no black voters. It is as simple

as that. Since adoption of the Louisi-

ana Constitution of 1898 and until rec-

ently, the legislature disfranchised

blacks overtly; it was never necessary

for the legislature to resort to covert

disenfranchisement [sic] of blacks by

manipulating [apparently neutral electoral

devices].

499 F.2d 893, 896(5th Cir. 1974), quoted in Wallace v. House,

515 F.2d at 633. Additionally, contemporaneous journalistic

accounts reflect other, non-racial reasons for the adoption

of Aci 281,

This finding-~that the 1911 Alabama legislature in pass-

ing Act 281 did not have a racially discriminatory pucrpose=--

should, under Washington v. Davis, end the inquiry and

21. : : . : eT

; Lhe [Alabama] Constitution of 190l1...eliminated the Negro

voter'"., M. McMILLAN, CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN ALABAMA 35 4

(1955),

“15

mandate judgment for defendants. However, since the Fifth

Circuit has not yet explicitly engrafted Washington upon

Zimmer and its progeny, and since Washington leaves some

room for admissibility of evidence of effect as it might

bear upon purpose, this Court will also make factual findings

in terms of the criteria of Zimmer.

C. Zimmer Factors. The Court herewith makes factual

findings upon each of the Zimmer criteria, for whatever

residual use they may be in dilution cases after Washington:

1. "Priwmarvy' Factors.

(a). "Lack of access to the process of slating

candidates'. Blacks in the City of Mobile have not been

deprived of access to the slating of candidates to the City

Commission; in Mobile there is no such slating. This find-

ing is parallel to the finding of Judge Pointer in the

Fairfield case “Yowever pernicious the operation of slat-

23

ing organizations might be in other cities, thev do not

exist in Mobile City elections. In fact, not only are there

22 he plaintiffs, blacks residing in the City of Fairfield,

have not demonstrated any lack of access to the process of

slating candidates for city elections; for in Fairfield there

has been no such slating'. Nevett v. Sides, F. Supp.

(N.D, Ala. June 11, 1975).

2315 Dallas City Council elections, a slating organiza-

tion styled the "Citizens Charter Association'', or C.C.A.,

"enjoyed dominance in city elections. Lipscomb v. Wise, 399

F.Supp. 782, 786(N.D.Tex.1975). A similar group, called the

"Dallas Committe for Responsible Government' or DCRG operated

in elections from that county to the state legislature.

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 766~-67(1973). In other

cases, political parties or party organizations with racial

solidarity served the same function. E.g., Turner v, J

McKeithen, 490 F. 2d 191, 195(5th Cir.1973) (one-party parish

where black vote solicited only after nomination). There is

no such monolithic political organization in Mobile City

Commission elections.

“16~

no non-partisan slating organizations for the City Com-

mission in wobtle, the elections are non-partisan and

the Democratic and Republican parties themselves do not

serve as slating organizations for the City Commission.

~All that is necessary is for a potential candidate to

qualify and to run.

A few other, more general findings concerning

Mobile political affairs may be in order in view of the

suggestion of the Supreme Court in White that these cases

call for an "intensely local appraisal...in the light of

past and present reality, political and otherwise'. 412

U.8.:at 769.

Unlike many Southern polities in which nomination

by the Democratic Party is tantamount to election, that is

not necessarily so in Mobile, even in races which (unlike

the City Commission races) are conducted on partisan tickets.

There is no longer any racial impediment of what-

ever nature to prohibit or hinder in any way a black (as

such) from registering to vote, voting, qualifying to seek

office, running for office, or being elected to office. In

sum, Mobile has an intensive, active, vigorous political

life, one which, at the present time, is as open to blacks

as to whites. As the Supreme Court wrote in Chavis:

The mere fact that one interest

group or another concerned with

the outcome of...elections has

found itself outvoted and without

legislative seats of its own pro-

vides no basis for invoking con-

stitutional remedies where, as

here, there is no indication that

this segment of the population is

o>

being denied access to the politi-

cal system.

403 B.S. at 154-53,

“17+

To whatever degree (if any) White v. Regester

differs from? and therefore controls Zimmer, this finding

alone should compel judgment for defendants. The Supreme

Court in that case wrote, as noted above, that the burden was

on plaintiffs to prove that their segment of the population

"had less opportunity than did other residents in the dis-

trict to participate in the political processes and to elect

legislators of their choice". 412 U.S. at 677. This finding

of openness under one of the Zimmer criteria seems to be,

under White, a finding of non-dilution without the necessity

of proceeding to other Zimmer factors.

(b). "Unresponsiveness of legislators to P &

[blacks'] particularized interests'. As an initial matter,

it may be noted that the evidence reflects that on many

issues of importance to citizens in Mobile there are no

"particularized interests' of blacks.

A significant segment of the proof adduced by

plaintiffs on the responsiveness issue tended to be in the

form of testimony concerning isolated instances of citizen

complaints about, for example, drainage or paving in a

particular area inhabited largely or entirely by blacks.

As Judge Pointer pointed out in the Fairfield case,

it should be noted that the in-

quiry is directed to "unrespon-

siveness', referring to a state,

condition or quality of being

unresponsive, and is not estab-

lished by isolated acts of being

unresponsive.

Nevett v. Sides, ¥.Supp. _(N.D. Mla, June 11, 1976).

This Court finds that the City of Mobile has

not, in recent years, evidenced unresponsiveness to particu-

24 ee note 14 Supra.

1 pa pA

«18

larized needs of blacks.

(i) City Services. The Court heard a con-

siderable quantity of testimony from both sides regarding

the nature and extent of various city services in the black

areas. This is not a case in which the "streets and side-

walks, sewers and public recreational facilities provided by

the town for its black citizens are clearly inferior to those

which it provides for its white citizens", Wallace v. House,

515 F.2d at 623 (emphasis added), or one in which the City has

evidenced "inexcusable neglect of black interests'. Id. In-

stead, the evidence in this case represents good faith

efforts to extend public services to both black and white.

A number of serious drainage problems exist in many sections

of Mobile, including several black areas; the City has at-

tempted and is attempting in good faith to remedy such prob-

lems inherent in a low-lying area such as Mobile. The

evidence further reflects that street paving, maintenance,

and repair and cleaning and the like-~to the extent that

those activities are conducted by the City rather than by

private developers Dn -ate performed by the City of Mobile

in a non~-discriminatory fashion. The evidence further reflects,

and this Court finds, that in several instances of unpaved

streets in black neighborhoods, the condition was due to the

fact that the cost of paving non-thoroughfare streets in

Mobile is normally assessed to abutting property owners, and

25Not all paving of streets in the City of Mobile is per-

formed by the City with City funds. A significant amount of

street construction is performed by real estate developers

in the construction of new subdivisions. There is no allega-

tion of any improper complicity between the City and such

developers with respect to such street paving.

«1Dw

that they had been unable or unwilling to be assessed for

street paving. As Judge Johnson has noted, that unwilling-

ness or inability to sustain a paving assessment does not

rise to constitutional levels:

The evidence...reflects that the

reason that a larger percentage

of the white residents are resid-

ing in houses fronting paved streets

is due to the difference in the re-

spective landowners' ability and

willingness to pay for the property

improvements. This difference in

the paving of streets and the estab-

lishment of sewerage and water lines

does not constitute racially discrim-

inatory inequality. The equal pro-

tection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States was not designed to

compel uniformity in the face of

difference.

Hadnott v. City of Prattville, 309 F.Supp. 967, 970 (M.D.

Ala. 1970).

To the extent (if at all) that a difference

in quality of city services exists, it may be in part attrib-

utable to vandalism of public property which, the evidence

shows, is significantly worse in black areas of town. To

the extent that is so, any differences in quality are not

constitutional deprivations. Beal v. Lindsey, 468 F.2d 287,

290-91(2d Cir.1972).

It is also worth noting that, to the extent

there is any inequity in the respective quality of city ser-

vices in black and white areas, plaintiffs have a direct

pin~-point remedy in a suit for equalization under Hawkins

v. Town of Shaw, Miss., 437 F.2d 1286(5th Cir.1971), aff'd

on rehearing en banc, 461 F.2d 1171(5th Cir.1972), at

least to the extent that any difference in service levels

20

was purposeful. Washington v. Davis, U.S. . hl

U.S.L.W. 4789, £793 n.12(U.8, June 7, 1976). To the extent

that any such inequity may be of significance to Mobile's

black citizens, the remedy might more appropriately be the

limited one of equalization rather than the radical one of

changing the entire form of the city government. Whitcomb

v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 160(1971); Note, 37 HARV.L.REV..

1851, 1859 n.50(1974).

(ii) Boards and Commissions. Plaintiff

has presented evidence reflecting that blacks are not re-

presented on the City's various boards and commissions in

proportion to their percentage of the population. Defendants

concede that to be so, and there has been no dispute over

that fact.

The discretionary appointments to city

boards and commissions, are as a matter of comity, either

entirely beyond federal judicial review, or very nearly so.

Mayor of Philadelphia v. Educational Equality League, 415

U.S. 605, 614-15(1974) (suit to insure bi-racial array of

city appointees); James v. Wallace, 7.24 {5th Cir.

June 21, 1976) (suit to compel Governor of Alabama to appoint

more blacks). That being so, back-door judicial relief in

the form of a finding of lack of responsiveness based on

appointments seems particularly inappropriate. There are,

in any event, several black board members, and an increase

in their number cannot be instantaneous under any form of

government. The Commissioners are "sowerless to appoint

blacks to boards and commissions until the appearance of

vacancies'. Yelverton v. Driggers, 370 F.Supp. 612, 619

25

-Z2]l~

(M.D. Ala. 1974). Additionally, the overwhelming majority

of these boards are simply irrelevant to the "particularized

needs of blacks'.

(iii) Disparity in Employment Statistics.

The city employment statistics indicate a disparity between

the percentages of white and black employed on the one hand,

and their respective percentages in the population on the

other.

The City of Mobile is limited in its

ability to employ those whom it might otherwise choose;

strictures are placed upon its hiring freedom by the fact

that the Mobile County Personnel Board (which is not a

department of the City) presents employment lists to the city

from which hiring is effected.

“To the extent that there might have been

improprieties in hiring, plaintiffs have and have had a re-

medy in this Court, in the form of lawsuits directly aimed

at remedying those violations rather than at a change in

the form of goverment, 20

Additionally, the Supreme Court has re-

cently noted in Washington that mere disproportionate

hiring by the city, without more, does not indicate a Con-

stitutional violation, = ‘U.S, ar .,44 1.8,L.¥. at

4794. That being so, it seems inappropriate to find a

constitutional violation by a back-door approach which in-

stead holds the form of government unconstitutional upon the

26 : : ;

See Allen v. City of Mobile, Civ. No. 5409-69-P(S.D.

Ala.) ; Anderson v. Mobile County Commission et al., Civ. No.

7385-72-H(8.D. Ala.).

0G

theory that there is a disparity in employment which is, in

itself, constitutional. A holding changing the form of gov-

ernment ought not to be based upon such gossamer, backward

logic.

In sum, the Court finds that there has

been no significant, general "lack of responsiveness' of the

city government in Mobile in recent years to the particularized

needs of blacks.

(c). "A tenuous state policy underlying the

reference for multi-member or at-large districting.

‘

oD

There is no clearcut state policy either for or against

multi-member districting in the State of Alabama, consid-

ered as a whole; hence, the "ambivalent state policy in

this regard must be considered as a neutral factor in our

consideration". Yelverton v. Driggers, 370 F.Supp. at 619.

Just as in Yelverton, however, it is appro-

priate to look at the state policy, as expressed by the

state legislature, with specific reference to Nobile.

A summary of each form of government obtain-

ing in the City of Mobile since prior to Alabama statehood

is attached as Appendix A. As that Appendix suggests, the

government of the City of Mobile throughout its history

for more than a century and a half has contained, at least

in part, some multi-member feature. For sixty-five years

the City Commission form of government with at-large elections

has been in effect in Mobile.

27A10ng the lines of the "intensively local appraisal

suggested in White, it may be noted that Mobile has long

been considered a political island outside the mainstream of

Alabama politics. That fact makes particularly appropriate

the consideration of the policy of the city itself regarding

these districts, in addition to that of the state as a whole.

«73.

Therefore, whatever the policy of Alabama has

been with respect to other municipalities in the state, its

manifest policy as to the City of Mobile has been, for a

significantly long period, multi-member districting.

(d)."The existence of past discrimination in

general precludes the effective participation in the election

system''. The City of Mobile in this litigation candidly ad-

mitted at the outset that, in the past, there were signifi-

cant levels of official discrimination by the City. There

is, of course, no doubt about that as Mobile's history in

this regard is similar to that of Southern cities generally.

The question, however, is not whether there was

discrimination in the city's history [admittedly there was],

but whether that discrimination today ''precludes the effec-

tive participation in the election system'.

The Court's finding is that the history of pre-

1965 discrimination does not presently preclude effective

participation in the political system. Every phase of the

processes of registration, voting, qualification, and run-

ning for a position on the City Commission 1s just as open

to blacks as to whites. Past discrimination does not ''pre-

clude effective participation' in Mobile City political

affairs, nor in, for example, legislative races where blacks

have been elected. As in the Fairfield case, '[t]lhe plain-

tiffs have not proved that past discrimination precludes the

effective participation by blacks in the election system.

Nevett v. Sides, F.Supp. (X.D. Ala, June 11,1976),

To the extent that blacks do not register, vote, or run for

ay Te

office to the same degree as whites, it is a product of

their own choice in the matter.

Virtually every Southern city or county (and

many Northern ones) has a sad history of racial discrimina-

tion; Mobile is not unusual in that respect. The concern is

with present facts; in this case we should avoid if possible

a result cintvolied by "legal standards...heavily weighted

in favor of past events'. Yelverton v. Driggers, 370

F.Supp. at 619.

(e). Summary of Findings on 'Primary'' Factors.

It is therefore seen that, for whatever value the Zimmer

criteria may be after Washington, none of the four "primary"

criteria of Zimmer are present in this case.

Ever under Zimmer, these negative findings

should mandate judgment for defendants. However, to com-

plete the record, the Court will also make findings herein

on the "enhancing' factors.

11 2. '"Enhancing'' Factors.

(a). Large Districts. The multi-member dis-

trict in this case constitutes the City of Mobile as a whole.

As Judge Pointer ruled in the Fairfield case, ''the election

district must be considered 'large', at least in a relative

sense. The district is as large as it can be''. Nevett v.

Sides, F.Supp. (N.D., Ala, June 11, 1976). The

same is obviously true in Mobile.

However, the district in Chavis which passed

constitutional muster was much larger than Mobile, contain-

ing 300,000 voters in 1964. 403 U.S. at 133, n.1l. The

two at-large counties in White v. Regester were also much

=25,.

larger, containing populations of 1,300,000 and 800,000.

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F.Supp. 704, 720(W.D.Tex.1972), aff'd

in part & reversed in part sub.nom. White v. Regester, 412

U.S. 755(1973). While Mobile is not ''large' in comparison

to those districts, it is probably large enough to be con-

sidered "large" within the meaning of this enhancing factor,

and this Court so finds.

(b). Majority Vote Requirement. Under Section

11 of Act 281, a majority vote is required for election,

(¢). Anti-Singleshot Voting Provisions. There

is in Act 281 no "anti-singleshot" voting provision; neither

is there one in its current codification [ALA.CODE tit. 37,

28

§89 et.seq.] or in Act 8523. In a sense, as Judge Pointer

29

held in the Fairfield case, the numbered-position provision

28pn "anti-singleshot' provision obtained in all city

elections in Alabama from 1951 to 1961:

A ballot commonly known or referred to as

"a single shot" shall not be counted in

any municipal election. When two or more

candidates are to be elected to the same

office, the voter must express his choice

for as many candidates as there are places

to be filled, and if he fails to do so, his

ballot, so far as that particular office is

concerned shall not be counted and recorded.

ALA.CODE tit. 37, §33(1l), repealed September 15, 1961.

29 judge Pointer held that:

(3) There is no anti-single shot voting pro-

vision since candidates run for numbered

positions. The numbered position approach

does have some of the same consequences how-

ever as an anti-single shot, multi-member

race; because a cohesive minority is unable to

concentrate its votes on a single candidate.

The numbered position approach does, however,

eliminate the problem caused when a minority

group is unable to field enough candidates

in anti-single shot, multi-member races.

Nevett v. Sides, F.Supp. at (M.D. Ala, June 11, 1976),

wll

of Act 823 [or, if Act 823 is invalid, tit. 37, §94] may

have to some extent the same result. This Court therefore

finds that, at least in part, the practical result of an

anti-singleshot provision obtains in Mobile.

(d). Lack of Residence Requirement. Act 281

does not contain any provision requiring that any commis -

sioner reside in any portion of town. If Act 823 is valid,

a residence requirement would be at a minimum anomalous

and probably even unconstitutional, as it would require that

the Commissioner in command of each particular function

(for example, Public Safety) reside in and be elected from

one particular side of town, accountable only to one third

of the population notwithstanding jurisdiction over the

entire city.

If Act 823 is not valid, on the other hand,

similar problems could likely ensue. In that event, the

majority of the Commissioners could apparently assign

whatever tasks it wanted to the third commissioner, ALA.

CODE tit. 37, §§95-96, or even perhaps no administrative

functions, leaving the district which he represents effec-

tively unrepresented in the administrative affairs of

the City. There are no apparent, explicit state law limits

upon such a practice contained in the optional commission

form of government statute. ALA.CODE tit. 37, §89 et.seq.

In sum, it appears that the enhancing factor

dealing with residence requirements is intended to be con-

sidered in cases involving city councilmen or the like

with identical duties, and is irrelevant to cases which,

like this, involve the City Commission form of government.

«27

If the factor should be deemed relevant, however, there

is none.

(e). Summary of Findings on "Enhancing Factors,'

and "Ageregate' of All Factors. There are in this case no

"srimary' factors present, but each relevant "enhancing"

factor is present, for whatever value the Zimmer factors may

have after Washington.

Even prior to Washington, under Zimmer criteria

alone, defendants would be entitled to judgment in this

case. Since none of the "primary" factors are present,

plaintiffs cannot be said to have proved an "aggregate" of

the Zimmer factors, and their claim must therefore fail on

that ground alone, even under cases formulated prior to

Washington v. Davis.

But there are also other considerations which,

for purposes of completeness of the record, merit consider-

ation.

III. DEFENSES AND OTHER PERTINENT CONSIDERATION

A. Traditional Constitutional Tolerance of Various

Forms of Local Government. It may be appropriate to note

that as a matter of constitutional law, the more "local" a

government, the greater the leeway which has been given to

it in constitutional/political cases. See, e.g., Abate v.

Mundt, 403 U.S. 182, 185(1971). The Supreme Court has been

particularly alert to avoid inflexible federal limitations

upon the form of local government:

Viable local governments may need many

innovations, numerous combinations of

old and new devices, great flexibility

in municipal arrangements to meet chang-

ing urban conditions. We see nothing in

the constitution to prevent experimentation.

28

Sailors v. Bd. of Edve., 387 0.5, 105, 110-11(1967). The

City Commission form of government was itself an experiment,

the evidence reflects; doubtless every form of local govern-

ment was once in some degree experimental. To the extent

that it is possible, cities should be allowed some measure

of freedom in their attempts to solve or mitigate govern-

mental problems. The Constitution should be flexible

enough to allow that experimentation:

Frequent intervention by the Courts in

state and local electoral schemes would

seem to run counter to the Supreme Court's

...concern for innovation and experimenta-

tion at the local level.

Note, 87 HARV.L,REV. 185, 1860(1974).

The second, third and fifth defenses raised by defend-

ants reflect this policy of comity and feduenalisng 0 as in

Mayor of Philadelphia, "[t]here are...delicate issues of

federal-state relationships underlying this case’. 415

U.S. at 615. The federalism problem is made most acute by

the fact that, if this Court were to impose single member

districts, in all probability the Court would have to

order that the very form of government be changed, from a

commission form to another and different form, such as

Mayor /Council.

B. Necessity for Change in Form of City Government

if Single-Member Districts Ordered. As enacted in 1911, as

already noted, the Commissioners of the City of Mobile ap-

portioned among themselves the duties of city government.

Technically, these federal/state relations cases do

& that

2

the federal government. Jackson, The Political Questior

Doctrine: Where Does It Stand After Powell wv. McCormack

73 1 [ + r= ETE 2 SN NA Try 7 . Vas - {HTT

O'Brien v. Brown, and Gilligan v. Morgan? 44, U.COL.1..REV,

477, 508-510(1973).

<20.

In 1965, Act 823 was passed, providing that Commissioners

be elected to specific posts for specific jobs.

As already noted, since plaintiffs have not prevailed

under either Zimmer alone or Zimmer as modified by Washington,

it has not been necessary for this Court to ask that a Three-

Judge District Court be convened to consider the validity of

Act 823. Whether or not Act 823 is valid under §5, the

Procrustean imposition of single-member districting, as al-

ready noted, would bring on absurd results caused by the

fact that liv commissioners, unlike aldermen or councilmen,

each perform different administrative functions. In order

to avoid such an anomaly, attendant on the imposition of

single-member districting upon the Commission form of govern-

ment, the Court would have to change the form of the city

government. The problem is fraught with difficulty, and

would clearly silicate against the imposition of single-

member districting as a remedy even assuming that plaintiffs

had prevailed on the merits.

C. "Swing Vote'. Testimony in this case suggests,

and this Court so finds, that blacks in Mobile not infre-

quently comprise a ''swing' vote able to decide close elec-

tions to a degree significantly beyond their percentage in

the population. While the actual effect is local in nature,

it is a phenomenon which is not uncommon in multi-member

district situations. E.g., Lipscomb v. Wise, 369 F.Supp.

782. 793(N.D.Tex.1975) (multi-member election permitted

3

- - ro : > -

Mexican/Americans "as a group to operate in a 'swing-vote

manner and give them opportunity they might not otherwise

have had"). Asone legal commentator has written:

«30

A group of voters that influences many

legislators in a small way is not in-

herently less desirable than a group

that has a large impact on one legis-

lator. Indeed, when other voters in a

district in which the blacks constitute

a minority are in a state of political

equilibrium, it may be that the black

group will wield political clout dis-

proportionately large for its numbers.

Carpeneti, Legislative Apportionment: Multi-Member Districts

and Fair Representation, 120 U.PA.L.REV. 666, 692-93(1972).

The swing vote factor is entitled to evidentiary weight in

support of multi-member districting.

D. Banzhaf Theory. Defendants also offered proof upon

the statistical propriety of the Banzhaf theory, explained

fully in Whitcomb v., Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 145 n.23(1971);

Banzhaf, One Man, ? Votes: Mathematical Analysis of Voting

Power and Effective Representation, 36 GEO.WASH.L.REV. 808

(1968) ; Banzhaf, Multi-Member Electoral Districts-~-Do They

Violate the '"One Man, One Vote' Principle, 75 YALE L.J.

1309(1966). The thrust of the theory is that if voting

power is defined as the chance that a voter will be able to

cast a decisive vote, then individual voters in multi-member

districts have more voting power than do individual voters

in single-member districts. The theory is purely a statis-

tical one, necessarily severed from the hard facts of

political life, and is separate and distinct from the find-

ing respecting the black vote as a swing vote, supra, which is

factually based upon the Mobile political experience. The

Supreme Court in Chavis declined to base its decision on

the Banzhaf theory, noting that it was ''theoretical', 403

U.S. at 145, but did not deny that the theory was entitled

to some (if not decisive) evidentary weight. This Court

“31

finds that the Banzhaf theory is entitled to be accorded

some evidentiary weight in favor of the retention of multi-

member districting in the City of Mobile.

E. City-wide Perspective. Evidence adduced by defend-

ants suggests, and this Court so finds, that the City of

Mobile has a legitimate governmental interest in having

Commissioners with a city-wide, non-parochial view of city

affairs. The evidence further suggests, and this Court so

finds, that such a city-wide perspective would be in signi-

ficant measure lost with the imposition of single-member

districting. The city-wide perspective has been found to be

a legitimate governmental interest by both courts and com-

mentators. In Lipscomb v. Wise, the District Court found

a "legitimate governmental interest' in having some city

council members with a "city-wide view on those matters

which concern the city as a whole', 399 F.Supp. at 795, and

suggested correctly that "[bjudget and services certainly

do not stop at district boundaries'. Id. at n.15. One

commentator has similarly written that:

The district-wide perspective and alle-

giance which result from representatives

being elected at-large, and which enhance

their ability to deal with district-wide

problems, would seem more useful in a

public body with responsibility only for

the district than in a state-wide legis-

lature.

Note, 87 HARV.L.REV. 1851, 1857(1974).

The desire of the City for a city-wide geographic

perspective is a factor entitled to some evidentiary weight

in this case in favor of the present form of government.

“32 -

F. Increased Polarization and Possible "Minority

Freeze-out'' Under Single Member Plan. Defendants have ad-

duced testimony, and this Court so finds, that if a single-

member plan of city government representation were adopted,

the degree of racial/political polarization would in all

likelihood at least stay at the same level, and perhaps

increase, with the result that the white majority in the

city would likely be able to elect a majority of the Commis-

sion. That, along with the fact that a single "black"

commissioner and each 'white" commissioner would likely

espouse narrow, parochial views of principal inEroRE: to

constituents of their single, racially homogeneous districts,

would cause nighly visible clashes in city government which,

inevitably, would be seen as principally racial in nature.

The probable result would be a virtual freeze-out of the

single black commissioner and his constituents. The same

problem was found by the Court in Lipscomb:

The Court is particularly concerned with

the prospect of district sectionalism

which usually occurs in an exclusive

single-member district plan. The Court

is convinced that no matter how many

single-member districts are drawn in

Dallas, black voters in all probability

would never elect more than 257 of city

council so long as the present pattern

of voting exists. With all single-

member districts and the present voting

pattern, it would be possible for a ma-

jority of council to "freeze out" this

25% and for all practical purposes ig-

nore minority interests.

399 F.Supp. at 795, n.l6(emphasis in original). The Court

has the same concern here, and finds that the significant

possibility of such a minority freeze-out is entitled to

evidentiary weight against a single-member districting plan.

«33

G. Single-Member Districting and New Constitutional

Problems. This Court finds that single-member districting

would import into Mobile city government two new and differ-

ent constitutional problems which the City has so far been

able to avoid: reapportionment and gerrymandering.

1. Reapportionment. One very significant factor

in favor of multi-member districting is that, with the ex-

ception pro tanto presented by the Banzhaf theory, multi-

member districting without a residence requirement presents

perfect numerical apportionment. Regardless of where a

voter lives, his vote will exactly equal every other vote,

even up to the end of each decade when post-census popula-

tion shifts have malapportioned most single-member districts.

Because of the notorious unwillingness of governmental bodies

in Alabama and elsewhere to apportion themselves, >t there is

a significant Hehe that a United States District Court

would ultimately be called upon to reapportion the city.

The possibility or even likelihood of that decennial necess-

ity certainly gives pause when considering whether to impose

single-member districting as a constitutional requirement.

That possibility 1s properly to be considered when deter-

mining the propriety of single-member relief.

2. Gerrymandering. A multi-member district does

not and cannot present the problem of gerrymandering of

Lnternals district lines. The imposition by this Court

3lpor the record of Alabama in that respect, see Stewart,

Reapportionment With Census Districts: The Alabama Case, 24

ALA.L.REV, 693, 694 n.6(1972).

32. ; : :

It is of course always possible for any city to attempt

to draw its perimeter so as to include or exclude certain

persons, see Gomillion wv. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339(1960), but

a multi-member district by definition has no internal district

lines.

3

of single-member districting would for the first time in

many decades introduce into Mobile the problem of gerry-

mandering. Whether ultimately brought into Federal Court

as a constitutional matter or not, see Wright v. Rockefeller,

376 U.S. 52(1964), the problem would be a significant one.

And, it is entertwined with the problem of reapportionment,

since the difficulty of political line drawing after each

decennial census inevitably suggests inaction by incumbent

officeholders.

The related problems of reapportionment and

gerrymandering have so far not been imported into the City

of Mobile. The imposition of single-member districting by

this Court would do so for the first time in recent history.

That 1s a factor of evidepiinng weight tending against the

imposition of single-member districting.

H. Flexibility of Federal Equitable Relief. Even if

the plaintiffs were to have made out a claim for equitable

relief, that would not necessarily entitle them to a change

in the form of government, or to the imposition by this

Court of single-member districts. Chavis makes clear that

the Court, upon finding for plaintiffs in a case of this

nature, ought to attempt if possible to remedy the wrong by

action less drastic than the wholesale imposition of single-

member districting:

[I]t is not at all clear that the remedy

is a single-member district system with

its lines carefully drawn to ensure rep-

resentation to sizeable racial, ethnic,

economic or religious groups and with

its own capacity for overrepresenting

parties and interests and even for per-

mitting a minority of the voters to con-

trol the legislature and government of

a state...

«35

Even if the District Court was correct

in finding unconstitutional discrimina-

tion against...[plaintiffs,] it did not

explain why it was constitutionally com-

pelled to disestablish the entire county

district and to intrude upon state policy

any more than necessary to ensure repre-

sentation of ghetto interest. The

Court entered judgment without express-

ly putting aside on supportable grounds

the...possibility that the Fourteenth

Amendment could be satisfied by a simple

requirement that some of the at-large

candidates each year must reside in

the ghetto.

Certainly, even if plaintiffs had prevailed in the

instant case, relief on less-than-a wholesale scale would

accord with the precepts of equity, encompassing '"[f]lexi-

bility rather than rigidity'. Hecht v. Bowles, 321 U.S.

32, 329-30(1944). Judge Johnson, for example, in an

analogous but pre-Washington case, upon finding for plain-

tiffs, merely ordered periodic reports to be made upon

the issues of trial (street paving, etc.), upon the ground

that the City was making good-faith efforts and "the appli-

cable legal standards are heavily weighted in favor of the

consideration of past events'. Yelverton v. Driggers, 370

F.Supp. at 619. In sum, single-member districting is not

necessarily the proper equitable remedy even if a constitu-

tional violation exists.

IV. AVAILABLE POLITICAL REMEDY

While the availability of a political remedy for

plaintiffs’ alleged wrongs by no means mandates abstention,

it is certainly worth consideration for whatever signifi-

cance it may have.

A. Legislative Remedy. The form of city government

Gn

presently obtaining in Mobile was, of course, passed by

-36=

the Alabama legislature in 1911. The record in this case

shows that under the prevailing custom in the legislature

called "legislative courtesy', that body will enact virtually

any local government provision agreed upon by the local

delegation.

The Alabama legislature is elected under a court-

ordered plan approved by the Supreme Court, from single-

member districts of near-perfect numerical apportionment,

Several of the members of the Mobile legislative delegation

are black and, plaintiffs would no doubt admit, represent

any "particularized interests' of Mobile blacks in that body.

In the course of the never-ending process of municipal gov-

ernment experimentation in Alabama and elsewhere, it does

not seem inappropriate to suggest that "relief" from a

legislatively~imposed government may well be available to

plaintiffs and their class from the legislature.

B. Abandonment. There is also available to the

citizenry of Mobile a state procedure styled "abandonment,

pursuant to which the voters can abandon the commission

form of government and return to the aldermanic system

obtaining prior to the adoption of the commission form of

government. ALA.CODE tit. 37, §120 et.seq. That abandon-

ment may be initiated by signatures of only three percent

33

Sims v. Amos, 336 F.Supp. 924(M.D.Ala.1972)(3-judge

court), aff'd, 409 U.S. 942(1973).

3% he legislature, for example, recently provided for

the City of Montgomery (which voted acceptance) a Mayor/

Council form of government to replace its Commission form.

Ala. Acts No. 618(1973). See also Robinson v. Pottinger,

512 F.2d 775(5th Cir.1975) (validity of that statute under

state law).

“37

of the registered voters of the city. Id. at §120. It may

be noted that the aldermanic form of government obtaining

in Mobile prior to 1911 had a residence requirement for

councilmen, so that a return to this form of government

would provide the very relief (residence requirement) the

imposition of which the Chavis Court said should be con-

sidered ae 0 possibly the appropriate form of relief

if plaintiff prevails in a case of this nature. 403 U.S.

at 160. Certainly the availability of this political relief

to plaintiff under state law, while not determining the re-

sult here, should be of evidentiary weight in this case.

/ YK,

[LS f) (LL Lill /

CB. ABENDALL, JR. /'

30th Floor, First National Bank Bldg.

Mobile, Alabama 36602

Attorney for Defendants

OF COUNSEL:

HAND, ARENDALL, BEDSOLE,

GREAVES & JOHNSTON

S. R. SHEPPARD//

{ L A a £x Lo

Attorney for Defendants

OF COUNSEL:

LEGAL DEPARTMENT OF THE

CITY OF MOBILE

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that I have on the (£7 day of

{¢ , 1976, served a copy of the foregoing document

7

on counsel for all parties to this proceeding, by mailing

the same by United States mail, properly addressed, and

first class postage prepaid.

A 7A / | / /

/ // , Z yy) 7 :

i

|!

APPENDIX A:

CITY OF MOBILE GOVERNANCE

[contains basic organizational statutes only]

1. 1814: [At-large]: Seven Commissioners were elec-

ted at-large for the town of Mobile; they elected a President

from their number. rot 0 Legislature of the Territory of

Mississippi, January 23, 1814. (Source: Toulmin's Digest,

r+. 780).

2. 1819 [At-large]: City of Mobile was incorporated,

governed by a Mayor and six aldermen to be elected at-large

annually. Ala. Acts No. (1819) (passed December 17,

1819). (Source: Toulmin's Digest, p. 784) (Alabama became

a state in 1819).

3. 1825 [neither at-large nor single-member districts]:

A Mayor and six aldermen were to be elected at-large, after

which they were to divide the city into three or more wards,

from each of which two or more aldermen would be elected,

not to exceed a total of nine aldermen. Ala. Acts No.

(1826) (passed January 9, 1826).

4, 1833 [no change]: The legislature provided for

election of commissioners whose only duty it would be to

divide the city into wards. No change was otherwise made

in the Zorn of government. Ala. Acts No. 68(1833).

5. 1840: The change made in 1840 cannot be located.

Apparently a form of government substantially identical

to the 1844 statutory form was adopted.

ii

6. 1844 [mixed plan]: This statute consolidated a

number of prior statutes. It provided that the city would

be governed by a Mayor and seven-member Common Council, to

be elected at-large, with a provision that one common council-

man reside in (but not be elected from) each ward. There was

also a Board of Aldermen, to consist of three members elec-

ted by the voters of each ward, or, a total of rani Seine

aldermen. Ala. Acts No. __ (1844) (January 15, 1855)

[ Source: CODE OF MOBILE (1858)].

7. 1866 [mixed]: The number of wards was increased

from seven to eight, but the form of government was not

changed. Ala. Acts Wo, (1856),

8. 1868 [At-large]: This statute provided that the

Governor was to appoint a Mayor, twenty-four aldermen, and

eight common councilmen until their successors were elected.

The statute did not limit appointments to geographic areas

and was therefore apparently an at-large form. Ala. Acts

No. (1868Y(p.4),

9. 1868 [At-large]: This repealed the earlier 1868

act. It provided that the Governor was to appoint twenty-

four aldermen and eight common councilmen who would then

assemble in convention and elect the Mayor. The statute

"under this act the Governor may explicitly provided that

appoint any inhabitant of the City of Mobile, without

reference to the ward in which he may reside." Ala. Acts

Vo. 71 (1868).

10. 1870 [At-large]: This statute repealed the former

act, declaring the former offices vacant. It provided that

the Governor would appoint the Mayor, twenty-four aldermen,

111i

and eight members of the common council, and also provided

that the Governor might appoint these officials without

reference to which ward the appointee resided in. Ala. Acts

No. 97. (1870).

11. 187% {vo change}: This repealed section 3 of the

1868 act, which appears to have been already repealed in

any event. Ala. Acts No. 148 (1871).

12. 1874 [At-large]: This statute provided that all

of the city officials wad be elected at-large, with a

requirement that the aldermen and common councilmen must be

residents of the wards for which [but not by which] they

were elected. Ala. Acts No. 365 (1874).

13. 1879 [At-large]: This statute abolished the

City of Mobile, and provided that the Governor, with the

advice and consent of the Senate, would appoint three

commissioners to liquidate the city. Ala. Acts No. 307

(1879). The same session of the legislature [Ala. Acts

No. 308 (1879)] incorporated the "Port of Mobile'. The

Port of Mobile was to be governed by eight commissioners

elected at-large, one for each ward who must reside in that

ward. The Commission would then elect a President.

14. 1886 [At-large]: This statute, re-establishing

Mobile as a city, provided a Mayor, a Board of Aldermen,

and a Board of Councilmen, all of whom were elected at-

large, [Id. at §12], although one councilman had to reside

in, but not be elected by, each ward. The Mayor, Board

of Aldermen, and Board of Councilmen met together as

"The Mayor and General Council", in which legislative

power was vested. Ala. Acts No. 152 (1866).

iv

15. 1897 [At-large]: No change significant to this

case; same form of government was retained. Ala. Acts No.

214 (15897).

16. 1901 [At-large]: No change significant to this

case; same form of government was retained. Ala. Acts No.

1039 1/2 (1902).

17. 1911 [At-large]: The Commission form of govern-

ment was established in 1911, the at-large feature of which

has been continually in effect. Ala. Acts No. 281 (1911).

18. 1940 [specific duties]: This amendment provided

that a Mayor would be elected specifically to that position,

and a division of the administrative tasks was made by sta-

tute between the two associate commissioners, one of whom

was assigned by the majority of them to each set of tasks.

ALA.CODE tit. 37, $95 (1940).

19. 1945 [numbered posts, no apportionment]: In

1945, the apportionment of administrative tasks by statute

was repealed, but numbered posts were instituted. Ala. Acts

No. 295 (1945).

20. 1965 [specific duties]: Specific duties were

assigned to specific numbered commission posts, and a sys-

tem of rotation of the mayoralty was established. Ala.

Acts No. 823 (1965).