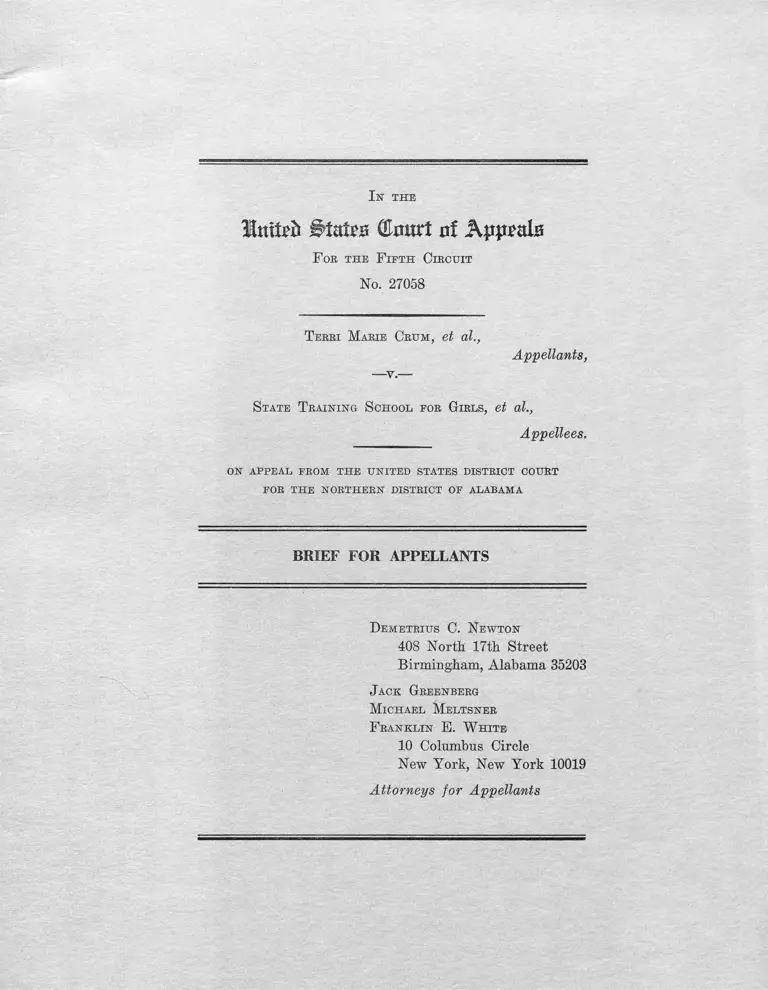

Crum v. State Training School for Girls Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 17, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Crum v. State Training School for Girls Brief for Appellants, 1969. d2982faf-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc0fba19-dbb7-4423-a641-d959fba3d032/crum-v-state-training-school-for-girls-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

H & m tib (Enurt 0! Appeal#

F or t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 27058

T e r r i M a r ie C r u m , et al.,

Appellants,

S t a te T r a in in g S c h o o l fo r G ir l s , et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

D e m e t r iu s C. N e w t o n

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

J a c k Gr e e n b e r g

M ic h a e l M e l t s n e r

F r a n k l in E. W h it e

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Mae

Preliminary Statement. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Statement Of The Case

1. The Pleadings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

2. The Evidence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

3. The Initial Decision of the District Court . 7

4. Appellees' Desegregation Plans . . . . . . . 8

5. The Final Order of the District Court. . . . 10

Specifications of Error. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Argument

I. The Court Erred In Dismissing The

Honorable G. Ross Bell And The

Juvenile And Domestic Relations H

Court Of Jefferson County, Alabama . . . .

II. The Court Erred In Failing To Require

The Alabama Industrial School For

Negro Children To Submit A Desegregation 14

Plan Simultaneously With The Other

Defendant Schools. . . . . . . . . . . . .

III. The Court Erred In Approving The

Desegregation Plans Of The Alabama

Boys Industrial School And The

State Training School for Girls,

Which Plans Fail Adequately To

Insure That The State's Unconstitutional

Policy Of Maintaining Racially Segregated

Facilities, Student Bodies, And Faculties

Will Entirely And Effectively Be

Terminated . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Conclusion 25

Certificate of Service 26

Adams v. Matthews, __ _F. 2d

No.26501 (August 20, 1968)

Archie v. Alabama Institute for the Deaf

and Blind, 395 F. 2d 765, 767 (1968)

Board of Managers v. George 377 F.2d 7 22

228 (8th Cir. 1967)

TABLE OF CASES

Boston v. Rippy 285F. 2d 43 (5th Cir.1960) 22

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 14

483 (1954)

PAGE

22

16

Bush v. Leach, 22F. 2d 296 (2nd Cir.1927)

Caddo Parish School Board v. United States,

389 U.S. 840 (1967)

13

22

Edward v. Sard, 250 F. Supp. 977, 979 (1966)

Fields v. Mutual Ben. Life Ins. Co., 93F. 2d

559 (4th Cir. 1938)

George v. Board of Managers, 377F. 2d 228

(8th Cir.1967), cert, denied Oct. 9, 1967 L. Ed)

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963)

Graves v. Walton County Board of Education,

___F. 2d No.26452 (Sept. 28, 1968)

Green v . County School. Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430, 442.

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964)

Hewitt v. Charles R. McCormick Lumber Co.,

22F. 2d 925 (2nd Cir.1927)

Houston Independent School District v. Ross,

282 F .2d 95 (5th Cir.i960)

21

14

22

17

16,22

22

14

22

Johnson v. Virginia 373 U.S. 61, 10 L. Ed.

2d 199(1963)

Shultz v. Manufacturers Trading Trust Co.,

103 F. 2d 771 (2nd Cir. 1939) 13

State Board of Public Welfare v. Myers

224 Md. 167A. 2d 764

Singleton v. Board of Commissioners,

356 F. 2d 771, 772 (1966)

Street and Smith Publications, Inc.

v. Spikes 107F.2d 755 (5th Cir.1939)

United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, 372F. 2d 836

Washington v. Lee, 263F. Supp. 327

(MD Ala.1966) , af f ' d U.S.___

88 S.Ct. 457 (1968)

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526

STATUTES INVOLVED

Code of Alabama, 1940, Title 52

Recompiled 1958

Section 570

Section 590

Section 613 (1)

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 27058

TERRI MARIE CRUM , et al.,

Appellants

- v -

STATE TRAINING SCHOOL FOR GIRLS et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Preliminary Statement

This is an appeal from orders of the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama

(Hon. Clarence W. Allgood) entered August 2, 1968, and

October 4, 1968. The August 2, 1968 order granted the

motion to dismiss as to defendants G. Ross Bell and the

Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court of Jefferson County,

and failed to require desegregation of the Alabama Industrial

School for Negro Children for another year. The order of October

4, 1968 approved plans for desegregation of the Alabama Boys

Industrial School and the State Training School for Girls, which

fails

appellants' contend/to insure that the State's unconstitutional

policy of maintaining racially segregated facilities, student

•i-bodies and faculties will entirely and effectively be terminated.

Statement of the Case

1. The Pleadings

Appellants filed May 31,1967 a class action seeking to

_2_yenjoin the maintenance pursuant to state law, of separate

facilities for the races at three schools operated by the

State of Alabama for delinquent children - - The Alabama Boys

Industrial School, the State Training School for Girls, and The

Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children. The complaint

also alleged that plaintiffs at the Alabama Institute for Negro

Children are injured by " inferior and unequal facilities, treatment

and training provided them by the school to which they are

_i_/

assigned. " (A. 5)

1 / Appellants filed notice of appeal, October 22, 1968, and a

a timely amended notice was filed October 23, 1968 (A.51)

2 / The Alabama Statutes creating and governing the operations

of the three Institutes are at Code of Alabama, Tit. 52

§ 570-613. Section 570 provides for the establishment of

" a correctional and educational institution . . . for

delinquent white girls . . . " ; Section 590 provides that

the Alabama Boys Industrial School " Shall receive, care and

provide for the welfare of white boys . . . " ; Section 613 (1)

establishes the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children.

3../ The pre-fix " A " refers to pages of the Appendix to

Appellants' brief.

2

The Institutions, their Superintendents and Boards of

Trustees, the Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court of

4a /

Jefferson County and Judge G. Ross Bell were named defendants.

On July 10, 1967 Paul J. Hooton, moved to dismiss himself

and other members of the Board of Trustees of the Alabama Boys

Industrial School. On July 17, 1967 the Juvenile and Domestic

Relations Court of Jefferson County and the Hon. G. Ross Bell

moved to be dismissed as defendants. The District Court August

23, 1967 entered an order taking these matters under advisement

pending the decision of the Supreme Court in Washington v. Lee,

4b_/

263 F. Supp. 327 ( M.D. Ala. 1966) (A. 29) Appellants moved

for summary judgement May 14, 1968, immediately after the

United States Supreme Court __ U.S. __ 88 S. ct.457, (1967)

affirmed the District Court decree in Washington v. Lee

declaring segregation of the races in prisons and jails

unconstitutional.

A hearing was held before the Hon. Clarence W. Allgood

July 26, 1968.

4a / Judge Bell has authority under Alabama law to commit

delinquent children to state training schools.

-.4b/ Washington v . Lee involved the desegregation of prisons

and jails in Alabama.

3

The Evidence

Testimonial evidence given by the Superintendents of the

three defendant Schools, disclosed the following:

Children between the ages of 12 and 18 are committed to

the three defendant institutions by the juvenile courts of

the state of Alabama after a finding by the judge of the Juvenile

jurisdiction that such children are delinquent. (A - TR. 3,39,66).

White boys from any of Alabama's 67 counties are sent to the

Alabama Boys Industrial School (A - TR 35); white girls are

sent to State Training School (A - TR 16); Negro boys and girls

are sent to the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children

(A - TR 63)o At the time of the hearing there were no staff

members of the opposite race in two of the schools, (State

Training School for Girls, (A - TR 11) and Alabama Industrial

School for Negro Children (A - TR 63)Jl and presumably none in

the third (Alabama Boys Industrial School).

The State Training School for Girls

The school has facilities for 78 girls? (A - TR 4) , and at the

time of the hearing had exactly that number (A - TR 3). The

Superintendent testified that a cottage was then in the process

of being renovated which would make room for 20 more girls after

October 1st 1968 (A - TR 19). There are a number of cottages in

which each girl has an individual private room (A - TR 6 ). The

girls share bathroom facilities, recreational facilities, and all

2 .

4

the students eat together ( A - TR 6 ).

The school provides academic schooling up to the 9th grade.

For older girls a program is available for the high school

equivalency diploma (A - TR 8 ). The School receives psychiatric

consultation from the State Department of Education (A - TR 7);

a reading program is made available under the University of

Alabama Language Development Center (A - TR 16); medical care,

dental care, recreation and work programs are also provided

(A - TR 4). The girls are kept a minimum of 16 months and the

school therefore keeps other girls on waiting lists for admission

after the court has found them delinquent (A- TR 5). The

rehabilitation rate is good, and the Superintendent feels the

school " really has something to offer . . . 11 (A- TR 7) .

Mrs. Weiss; the Superintendent, received a Masters degree from

Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio and has been in

social work for 34 years (A - TR 12).

The Alabama Boys Industrial School

This school had, at the time of the hearing an enrollment of

200 boys, with a capacity for 214 (A - TR 36). The average length

of stay for a boy is 10 months (A - TR 37). Mr. Carr testified

that he would rather have a shorter period of stay than have the

boys wait for admission in jail (A - TR 37). The School offers

academic programs for the 1st through the 10th grade. Academic

achievement is stressed, he indicated, in both the academic and

vocational programs (A - TR 38), despite the fact that most of

5

the children have sub-normal intelligence (the average I.Q is 89)

(A - TR 43). The school has a bus which they use to take the

students to cultural events; there is also a school band, and

a school newspaper. (A - TR 44). Mr. John Carr,Superintendent

of the Alabama Boys Industrial School, has a Masters Degree in

Social Work from Columbia University in New York.

The Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children

In contrast to the other two schools, the Alabama Industrial

School for Negro children, enrolls both boys and girls. At the

time of the hearing, the school had an enrollment of 460— -106

girls and 357 boys, in a school with a capacity of only 300

students (A - TR 47-48). Unlike the white schools, the enrollments

of which were at or under capacity, the Negro school was and is

"bursting at the seams." The program at the school is essentially

a work program (A — TR 52). The school raises cucumbers,

5 /

and sold $13,000 worth in 1967 (A - TR. 47). There is a canning

plant on the campus (A - TR 50). Academics are not stressed:

many of the children have never been to school before (A - TR 50),

and textbooks are not donated by the state but must be purchased

from the school’s already inadequate budget (A - TR 51).

5 / Mr. Carr testified that the farming was necessary

to support the school: " My money is scarce and if it

wasn't for us farming out there, you see, we would be

up against it . ..." (A - TR 56).

6

Boys and girls live in separate dormitories, all of which

have double beds. All 106 girls live in a single building, which

was built to house 80 students (A - TR 61).

There are 14 teachers for 460 students (A ~ TR 62). One group

goes to school for six days while the other group is out farming,

and the groups then alternate (A - TR 62). This school, in contrast

to the white institutions, does not have a single welfare worker

(A - TR 64)

Mr. E.B. Holloway, Superintendent of the School was the Farm

Director of the school prior to being promoted to Superintendent

(A - TR 46) .

3• The Initial Decision of the District Court

On August 2, 1968, the Court entered an opinion and order.

In its opinion the Court denied the motion of defendant Paul B.

Hooten to dismiss the suit as to members of the Board of Trustees

of the Alabama Boys Industrial School (A. 38); granted the motion

to dismiss of Judge G. Ross Bell and the Juvenile and Domestic

Relations Court of Jefferson County (A. 38); and denied plaintiffs'

motion for a summary judgment. Regarding the challenged Alabama

Statutes, the Court found that :

/t/o the extent that Sections 570, 590, 613(1)

of Title 52 Code of Alabama 1940, Recompiled

1958, require segregation of juveniles to

white schools or Negro Schools based solely

upon the race of the individual; to the extent

that the statute's require commitment to segregated

facilities; to the extent that the statutes require

maintenance of segregated facilities, they are clearly

unconstitutional. Board of Managers of Arkansas Training

7 -

School for Bovs v. George, 377 F. 2d 228

(8th Cir. 1967). (A. 38-39).

The Court ordered the State Training School for Girls and

the Alabama Boys Industrial School J to submit a plan within

60 days after the date of the decree, and stated that the :

proposed plan or Iplans to be submitted by

the defendants provide for some practicable

or feasible method of selecting and designating

the school to which those juveniles committed

by the juvenile court judges will be sent.

(A.39) .

The Court, noting the over-crowded condition of the

Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, it's co

educational status, and (without benefit of testimony to

this effect) the fact that some of the children in the

school were sex offenders (A. 40), declined to require

the school to submit a plan with the other defendant insti

tutions. It was allowed, instead, a yeear in which to file

such a plan. (A. 40). Although a year has passed, no such

plan has been submitted.

4. Appellees' Desegregation Plans

The Alabama Boys Industrial School filed their plan

September 30, 1968 (A. 42-45). The plan provides in

essence that the school will:

1) Accept Negro students from 29 of the 67 counties

in the state, such counties being located in the

northern part of the state.

8

2) Notify the 67 juvenile court judges that no boy

is to be brought to the school for admission until

approval has been received from the institution.

3) Admit 4 Negro students at a time of approxi —

n.ately the same age and size, who would all be

assigned to the same cottage at the end of a 12

day orientation period.

4) Accept (after some undesignated period thereafter)

cwo Negro students per orientation period.

5) Report to the Court every 90 days on their

progress.

6 ) Fill future vacancies on the staff with the

persons possessing the best qualifications regard

less of race, color or creed.

The State Training School for Girls filed with the

Court December 4, 1968 a copy of their Board Minutes,

which included in essence the following desegregation

plan (A. 47-48) :

1) Applications of Negro students would be accepted

on the same basis as applications of white students.

2) The Juvenile Court Judges will be kept informed

of space and progress.

3) Applications for staff vacancies would be considered

without regard to race (one Negro teacher has been

employed).

9

4) The program will be reviewed by the Board of

Trustees once a year.

5. The Final. Order of the District Court

On October 4, 1968 the District Court approved

the plans of two defendant schools (A. 50). Appellants

filed an amended Notice of Appeal on October 23, 1968.

Specifications of Error

The Court below erred in:

1) Dismissing Judge G. Ross Bell and the Juvenile

and Domestic Relations Court of Jefferson County

as defendants?

2) Failing to require the Alabama Industrial School

for Negro Children to submit a desegregation

plan simultaneously with the other defendant

schools; and

3) Approving the desegregation plans of the

Alabama Boys Industrial School and the State

Training School for Girls, which plans fail

to insure that the State's unconstitu

tional policy of maintaining racially segregated

facilities, student bodies and faculties will

entirely and effectively be terminated.

10

ARGUMENT

I .

The Court Erred In Dismissing Judge

G. Ross Bell And The Juvenile And

Domestic Relations Court of Jefferson

County As Defendants.

The Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court and Judge

G. Ross Bell were properly named as Defendants in the

original complaint, and are proper parties in this appeal.

The complaint alleged, and indeed, the Alabama statutes

Vprovide, that boys and girls may not be admitted to the

Industrial Schools except by commitment of a Juvenile

Court, and that such courts must assign delinquent children

to certain schools on the basis of race. There can be no

doubt but that plaintiffs are thus denied their constitu-

tional right to be free of state-imposed segregation.

The District Court so found in the opinion below (A. 39).

It is now a truism that segregation in

any state-owned and operated institutions

violates the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. As the Supreme

Court recently put it: "It is no longer

open to question that a state may not

constitutiona1 ly require segregation of

public facilities," Johnson v. Virginia,

373 U.S. 61, 62 (1963)(courtroom). Dawson

v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,

220 F.2d 386 (4th Cir.), affirmed 350 U.S.

877 (1955) (beaches and bathhouses);

6/ Code of Alabama, Vol. 12, Tit. 52, Sec. 573, Sec. 590,

and Sec. 613(4).

11

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 u.S. 526 (1963)

(parks and playgrounds). Washington v. Lee,

263 F. Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966) affd. ____

U • S. _____ , 88 S. Ct. 45 7 (1968) . George v.

Board of Managers, No. 18536, decided May 23,

1967 (8th Cir.) (reform schools).

Under Alabama law only the Juvenile Court through its

judges has the power to commit delinquent juveniles to the

Industrial Schools named in the complaint. Since appellants'

complaint seeks to enjoin the assignment of children to, and

the maintenance of, these schools on the basis of race, it

follows that relief can appropriately be sought against the

court and its judges. Indeed, to be effective any order must

run against judges who make the actual assignment. The trans

cript of the hearing below is replete with statements by all

three Superintendents of the defendant schools which acknow

ledge the control of the Juvenile Courts and their judges over

the enrollment in the various schools.

For example, Mrs. Weiss, Superintendent of the State

Training School for Girls stated: "Well, of course, I can't

take a girl unless the judge commits her." (A-TR 24), "The

girl goes under the judge's authority and I am, to a certain

extent under the judge’s authority. . ." (A-Tr 25) Mr. Carr

of the Boys Industrial School stated, "We always accepted any

boy. We don't make the choice, the judge commits the boy."

(A-TR 39). Mr. Holloway of the Negro Industrial School

stated, "[W]hen the judge wants to send somebody [h]e says,

12

296 (2nd Cir. 1927); Hewitt v. Charles R. McCormick Lumber

Co./ 22 F.2d 925 (2nd Cir. 1927) ; Fields v . Mutual Ben. Life

Ins. Co., 93 F.2d 559 (4th Cir. 1938); Street and Smith

Publications, Inc, v. Spikes, 107 F.2d 755 (5th Cir. 1939).

It was necessary for appellants to see the proposed plans

of the defendant institutions before they were in a position to

decide if an appeal were necessary at all. Had the plans

submitted satisfied the standards and criteria previously laid

down by this court for the dismantling of segregated school

systems, an appeal might have been unnecessary.

If this court accepts the position of Appellants regarding

the unacceptability of the desegregation plans approved, it is

imperative that further plans incorporate the Court and Judges

responsible for making the assignments to the training schools.

II.

The Court Erred In Failing To

Require The Alabama Industrial

School to Submit a Desegregation

Plan Simultaneously With The

Other Defendant Schools.

Under Brown v . Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

— t -7---------- --------------------------

and subsequent decisions, it is clear that a state may not

U Johnson v . State of Virginia, 373 U.S. 61, 10 L.ed.

2nd 199 (1963).

14

constitutionally require the segregation of public facilities.

Singleton v. Board of Commissioners of State Institutions,356 F.2d

771, 772 (5th Cir. 1966) held that reformatories fell within the

principle of Brown:

" Twelve years ago, in Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka . . . , the Supreme

Court effectively foreclosed the question

of whether a state may maintain racially

segregated schools. The principle extends

to all institutions controlled or operated

by the state. "

Similarly in State Board of Public Welfare v. Robert Myers, 224 Md

246, 167 A. 2d. 764, the Court of Appeals citing Brown, ordered

the desegregation of Maryland training schools. Arkansas training

schools were ordered to desegregate their facilities in Board of

Managers v. George,377 F.2d 228 (8th Cir.1967) cert.denied ___ U.S.

______1 0/9/67 -

The District Court in this case found that the operation of

separate training schools for Negro and white children violated

the guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.(A.

39 ). Yet it ordered only two of the three institutions to submit

desegregation plans within 60 days of the order. The third school,

the Alabama Institute for Negro Children was given a full year

more to continue as a segregated institution , (A. 40 ) in clear

contravention of the rights of the plaintiff-appellants herein.

As the United States Supreme Court stated in Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U.S. 525, 531-530 (1963):

" The rights here asserted are, like all such

rights; they are not merely hopes to some future

enjoyment of some formalistic constitutional

promise. The basic guarantees of our Constitution

are warrants for the here and now and, unless

15

there is an overwhelmingly compelling reason,

they are to be promptly fulfilled . . . "

There is no suggestion in this record of an

" overwhelmingly compelling ’’ reason to delay desegregation

of all the reform schools in Alabama, indeed, there are

compelling reasons for requiring simultaneously the

desegregation of all three schools. The defendant institutions

in this case constitute the only reform schools for delinquent

children in the State of Alabama. But for the unconstitutional

requirement of the Alabama Statutes that such children be

assigned to schools according to their race, there would be

only one distinction required, that is to separate boys and

girls in so far as possible for administrative and disciplinary

reasons.

The system is therefore unitary in nature and should be

treated as such in an attempt to dismantle the unconstitutional

dual classification by race.

On May 27, 1958 the Supreme Court of the United States

rendered an opinion in Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430, 442, in which it held that

school boards are now required " to convert promptly to a

system without a 'white' school and 'Negro'school, but

just schools. "

In Adams v. Matthews , ____ F . 2d ______ , No.26501

(August 20, 1968) the Fifth Circuit applied Green in

another public school desegregation case and crystallized its

16

rule as follows:

If in a school district there are still

all-Negro schools, or only a small fraction

of Negroes in white schools, or no substantial

integration of facilities and school activities

then, as a matter of law, the existing plans

fail to meet constitutional standards as

established in Green. (Emphasis added.)

In Graves v. Walton County Board of Education, _______ F. 2d__

No. 26452 (Sept. 28, 1968), the Court reaffirmed its earlier

ruling that any plan which would permit a single all-Negro

school is prima facie unconstitutional;

In its opinion of August 20, 1968, this Court

noted that under Green (and other cases), a

plan that provides for an all-Negro school

is unconstitutional.

It added that the all-Negro schools in this circuit;

Are put on notice that they must be integrated

or abandoned by the commencement of the next

school year. . .

Appellants are, of course, aware that State correctional

institutions present some special considerations. Yet the

United States Supreme Court recently affirmed a three-judge

Federal Court order requiring immediate desegregation for the

educational programs and youth centers of Alabama prisons and

jails. Washington v. Lee, 263 F. Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala., 1966)

aff'd ___ U.S. , 88 S. Ct. 457 (1968). There is no

meaningful distinction between the youth centers involved in

Washington v. Lee, supra and the training schools in this case.

Despite the fact that the court below stated that the Washington

v . Lee case was controlling in the instant suit, it failed to

order immediate desegregation of any of these educational

institutions.

17

The overcrowded condition of the Alabama Industrial

School (163 over capacity) (A-TR H-S ) would logically be in

centive to require simultaneous desegregation of the three

schools, with a view toward alleviating that very condition

by sending some children to the other schools which are now

at or under-capacity in enrollment (A-TR 3,19,36). Otherwise,

the full burden of overcrowded and inferior facilities will

be carried by Negro students.

Approval of desegregation plans of the two white

institution without consideration of the future of the Negro

school is therefore unwarranted by the facts, unconstitutional

hy standards laid down in the Green and subsequent decisions,

and totally ineffective in dismantling the prohibited dual

system.

III.

The Court Erred in Approving The

Desegregation Plans of the Alabama

Boys Industrial School and the State

Training School for Girls, Which

Plans Fail Adequately to Insure That

The States' Unconstitutional Policy

of Maintaining Racially Segregated

Facilities. Student Bodies, and

Faculties Will Entirely and Effectively

Be Terminated.

The desegregation plan submitted by the State Training

School for Girls provides nothing more than general statements

that it will in the future accept students and hire new faculty

members on a non-discriminatory basis (A. 46-47).

18

proposesThe plan offered by the Boys Industrial School

to take Negro students only from a limited part of the State

(29 northern counties, in a total of 67 counties) ;; to require

the courts to, in effect, ask permission of the school before

sending Negro students to its School: to assign the Negro

students so enrolled to the same dormitory in groups of four,

and to reduce the number of Negro students being enrolled by

half after some unspecified period of time. (A. 43-45). The

oniy plan for faculty integration is a statement that future

vacancies will be filed regardless of race, color or creed

(A. 45).

Appellants contend that these plans fail to adequately

insure that the States' unconstitutional policy of maintaining

racially segregated facilities, student bodies and facilities

will entirely and effectively be terminated.

These plans fail first, as was discussed at pages 14-17,

xr̂ frei, because they are not part of a uniform plan including

the Alabama Industrial School for Negro children.

The plans fail in addition in lack of specifity as

follows:

1. No dates are given for the achievement of complete

desegregation of the Schools.

2. in the case of the Girls' School, the agreement to

comply with the Court s order is too general to serve as a

guideline for future administrative conduct.

19

3. The Boys' School plan proposes to perpetuate the

prohibited discrimination by taking only limited numbers of

Negro applicants, and decreasing rather than increasing the

number at a time left to the Schools discretion to chose,

4. No specific procedures for accomplishing the ends

stated in both plans are included.

5. No provision is made for the immediate transfer of

students from one school to another.

6 . They continue, instead of eliminating segregation

in dormitories.

The District Court below took several preliminary matters

connected with this case under advisement pending the decision

of the Supreme Court in the case of Washington v. Lee, 263

F. Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966), which the court considered

controlling (A. 29). The Supreme Court, per curiam,-" upheld

the three-judge District Court decree which declared specified

Alabama statutes unconstitutional to the extent that they

required segregation of the races in Alabama prisons and jails.

In that decision, the Court recognized the special circumstance

involved m desegregation of correctional institutions, stating

the association between men in correctional

institutions is closed and more f raught with

physical danger and psychological pressures

than is almost any other kind of association

between human beings.

U.S. ___88 S.Ct. 457 (1968).8/

The Court, therefore, ordered desegregation of the penal

facilities of the State of Alabama at different rates of time,

the longest period being one year for total desegregation for

maximum security adult facilities:

The several honor farms, the educational

the youth c e n t e r 1 «

in the state system must be desegregated

immediately. All facilities in the minimum

and medium security institutions. . . must be

completely desegregated within six months. As

to the maximum security institutions. . . the

Court will expect complete and total desegregation

• . . within a period of one year. (Emphasis added.)

It has now been over a year since the District Court

ordered two of the defendant schools in this case to desegregate

their schools. These schools clearly fall within a parallel

classification of the Lee case as educational programs and Youth

Centers. Their complete and total desegregation should therefore

have been accomplished immediately, and the District Court erred

in approving plans which accomplished less than that required

by the Lee decision.

Unjustifiable delay perpetuates the prohibited segregation.

As the united States District Court for the District of Columbia

stated in another case challenging discrimination in

re forma tone s :

Since full racial integration is invariably

a desirable goal, racial discrimination may be

seen as any unjustifiable delay in achieving

this goal.

The District Court's acceptance of the plans in question

reflects that court's failure to grasp the settled principle

2/ Edward v. Sard, 250 F. Supp. 977, 979 (1966).

21

that schemes which technically approve desegregation but

retain the school system in its dual form must be struck down.

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963); Griffin v.

County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964);

Boston v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960); Houston Independent

School District v . Ross, 282 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1960); United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836,

affirmed with modifications on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385,

cert, denied sub nom Caddo Parish School Board v. United States,

389 U.S. 840 (1967); Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430, 441.

This principle is equally applicable to state correctional,

institutions as it is to Public Schools. Singleton v . Board of

Commissioners, 356 F.2d 771, 772 (1966); Board of Managers v.

George, supra; Washington v. Lee, supra.

The plans of both boys' and the girls' industrial schools

fail to provide for satisfactory faculty as well as student

desegregation. This difficulty was encountered in the desegrega

tion plans of another special school system in Alabama, for deaf

and blind children. The Court there stated clearly what would

be required of such plans regarding faculty:

This Court's Jefferson parish decision, makes

it clear that teaching staffs must be integrated

without waiting for the filling of future

vacancies on a non-racial basis. Every effort

must be made by this institution to comply with

this requirement in Jefferson in the same manner

as is required of public schools.1 0/

10/ Archie v . Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind,

395 F.2d 765, 767 (1968).

22

The only feasible method by which the dual reform school

system in the State of Alabama can desegregate its operations

as required by Lee, Jefferson and Green is by adoption of a

unitary plan for the assignment of children pursuant to non-

racial geographic zones and/or pairing of schools. There are,

for example 106 girls at the Alabama School (A-TR. 47) who

might be moved to the State Training School for Girls, and the

Alabama Boys and Alabama School for Negro children might then

be paired-one, to take all boys from age 12-15 and the other

16-21, or paired geographically. Present staff, both

professional and non-professional could be shared between the

schools, thus achieving integration of the faculty.

Appellants are mindful that desegregation may cause a

number of administrative problems at these schools. But the

complaint in this case was filed on May 31, 1967 and appellees

[the Alabama Boys' Industrial School and the State Training

School for Girls] were ordered to bring in a plan on August 2,

1968. Appellees have been given adequate notice that

reorganization of the segregated schools is a constitutional

imperative.

Appellants there fore respectfully submit that this case

be remanded to the district court with directions that the

appellee schools be directed to file promptly and serve upon

opposing counsel:

23

1. A plan for the complete integration of all three

schools which plan shall be implemented no later

than September 1969. The plan shall provide for

the integration of classrooms, dormitories,

athletic programs and all other activities and

services at each school. It shall provide for

the assignment of students by region or sex, or

both. No school may enroll only students of the

same race.

2. A plan for the complete integration of faculty.

Which plan shall provide for the immediate

reassignment of teachers and other service

personnel in such manner that the ratio of Negro

teachers at each site will be approximately the

same as the ratio throughout the system.

3. periodic reports to that Court on the progress

of the plan.

24

Conclusion

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons it is respectfully

submitted that the orders of the lower court be vacated and

that the case be remanded with instructions that appellees be

required to modify their plans in the respects outlined herein

and in any other manner deemed necessary by this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

FRANKLIN E. WHITE

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

DEMETRIUS NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Appellants

25

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that three (3) copies of the foregoing

Brief for Appellants have been served this 17th day of

January 1969, by air mail, postage prepaid to counsel for Appellees

as follows:

MacDonald Gallion Philip H. Smith

Attorney General Special Assistant Attorney

General

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

Robert P. Bradley

State Office Building

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

26