Boynton v. Virginia Transcript of Record

Public Court Documents

March 31, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boynton v. Virginia Transcript of Record, 1960. bf529b9c-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc2462a6-fe26-4095-b0c0-6d33929fcc25/boynton-v-virginia-transcript-of-record. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

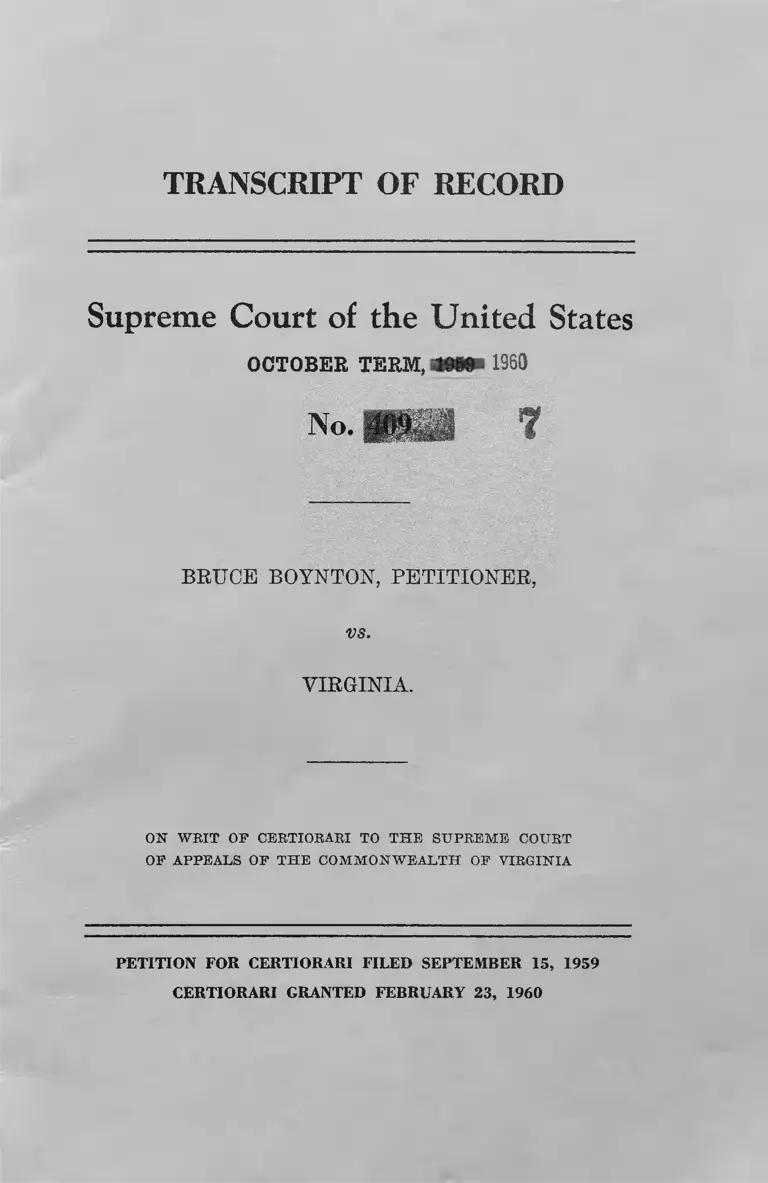

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1965

BRUCE BOYNTON, PETITIONER,

vs.

VIRGINIA.

ON W RIT OP CERTIORARI TO T H E SU PR EM E COURT

OP APPEALS OF T H E COM M ONW EALTH OF VIRGINIA

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED SEPTEMBER 15, 1959

CERTIORARI GRANTED FEBRUARY 23, 1960

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TEEM, 1959

No. 409

BRUCE BOYNTON*, PETITIONER,

vs.

VIRGINIA.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E SU PREM E COURT

OP APPEARS OP TPIE COM M ONW EALTH OP VIRGINIA

I N D E X

O riginal P r in t

Record from the Police Court of the City of Rich

mond, Commonwealth of Virginia

Warrant and certificate of conviction--------------- 1 1

Record from the Hustings Court of the City of Rich

mond ___________________________________ 3 4

Notice of tender of transcript of evidence and for

certification thereof -------------------------------- 3 4

Notice of appeal and assignments of e rro r...... .... 4 5

Motion to dismiss w arrant--------- -A --------------- 6 6

Minute entry of hearing ---------- --- ------- 7 7

Stipulation of facts and attachments ---------- 8 8

Attachment — Lease between Trailways Bus

Terminal, Inc. and Bus Terminal Restaurant

of Richmond, Inc., dated December 2, 1953- 10 9

Attachment — Transcript of trial proceedings

held in the Police Court of the City of Rich

mond, dated January 6, 1959 ---------------------- 20 19

Appearances ------------------------------------------- 20 19

R eco rd P r e s s , P r in t e r s , N e w Y o r k , N. Y ., M a r c h 31 , 196 0

11 INDEX

O riginal P r in t

Record from the Hustings Court of the City of Rich

mond-—Continued

Stipulation of facts and attachments—Continued

Attachment — Transcript of trial proceedings

held in the Police Court of the City of Rich

mond, dated January 6, 1959—Continued

Testimony of Stanley Sylvanius Rush—

direct ______________ 21 20

cross ______________ 24 21

Russell Forest Stout—

direct ______________ 30 25

cross ______________ 31 26

redirect ____________ 31 26

recross _____________ 32 26

Bruce Boynton—

direct ______________ 32 27

cross ______________ 37 30

Judgment _______________________________ 39 30

Order overruling motion to dismiss warrant and

suspending execution of sentence----------------- 40 31

Order re transcript________________________ 41 32

Certification to transcript (omitted in printing) __ 42 32

Proceedings in the Supreme Court of Appeals of

the Commonwealth of Virginia --------------------- 43 32

Order refusing writ of e rro r---------------------------- 43 32

Order staying execution and enforcement of judg

ment ___________________________________ 44 33

Clerk’s certificate (omitted) __________________ 45 33

Order allowing certiorari ------------------------------- 46 34

1

[fol. 1]

IN POLICE COURT OF THE CITY OF RICHMOND,

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

W arrant and Ce r t ific a t e of C on v ictio n

No. 26717

C o m m o n w ea lth of V ir g in ia > „ ,

City of Richmond > °~ 1 '

To A n y P olice O f f ic e r :

W h e r e a s , S ta n ley S. R u s h has this day made complaint

and information on oath, before me, the undersigned, a

Justice of the Peace of said city, that Bruce Boyington did

on the 20 day of Dee., 1958. CM-21

Unlawfully trespass upon the premises at Trailway Bus

Terminal, 9th and Broad Streets

These are, therefore, to command you, in the name of the

Commonwealth, to apprehend and bring before the Police

Court of the City of Richmond, the body of the above ac

cused, to answer the said complaint and to be further dealt

with according to law. And you are also directed to

summon

V Stanley S. Rush Address, Trailways Bus Terminal

as witnesses.

Given under my hand and seal, this 20 clay of Dec., 1958.

Amended Charge:

Jno. McKenney (Seal)

Justice of the Peace

Unlawfully did remain on the premises of the Bus Terminal

Restaurant of Richmond, Inc. after having been forbidden

to do so by S. S. Rush, Assistant Manager of the said

Bus Terminal Restaurant of Richmond, Inc., the said S. S.

Rush being then and there lawfully in charge of said prem

ises, there situate in the said City of Richmond

2

[fol. 2]

$300 bond

J. F. Me

Docket No, 7083

C o m m o n w ea lth

W arrant of A rrest

CM 21

vs.

B ruce B oyington

Salman, Alabama

Executed this, the 20 day of December, 1958 by arresting

the within named party, and by summoning the within

named witnesses to appear in Police Court, December 22,

1958.

R. F. Stout

Upon examination of the within charge, I find the accused

Con 1/6/59

Guilty

Fined $10.00 & $6.25 costs

H arold C. M aurice

Judge, Police Court

Stamp—Jan. 6,1959

3

S ta tistics

Place of birth .......... ................................................... ..... ....

A ge----- Color ..................... Sex ....... .............

Married □ Single □ Divorced □

Bead □ Write □

Occupation ....... .................. .............. .......... ............. ...........

C osts

Warrant ........... .......... ........................ ..................... $ 1.50

Trial ............................. ............... ............ .......... . 2.00

Bail ..................... ..... ..................................... ...... ....

A rrest............................ ..... ......... ............................ 1.00

Clerk, Htg. Ct. ................... ...................................... 1.25

Issuing Search War...... .................................... .....

Serving Search War............. .............. ....................

Witness Attendance ................... ............................ .50

Commonwealth Atty. ......... .............................. ......

Total Costs ....................... ......... ............... ...... $ 6.25

F ine ..................... ....................... ................. ......... 10.00

Total .............................................................. $16.25

l x P olice J u s t ic e ’s C ourt C it y of B ic h m o n d

January 6,1959

This is to certify that the within named Bruce Boynton,

was this day tried by me for the charge set forth within

this warrant, and that upon said trial he the said party

was duly convicted of the within charge, and sentenced to

pay a fine of $10.00 dollars, and costs $6.25 dollars, from

which sentence he the said party appeals to the next term

of Hustings Court.

Given under my hand this 6 day of January 1959.

H arold C. M a u r ic e , Police Justice.

4

[fol. 3]

1st t h e H u st in g s C ourt of t h e C it y of R ic h m o n d

C o m m o n w ea lth of V ie g in ia ,

v.

B eu c e B o y n to n .

T o : T. Gray Hadden, Attorney for Commonwealth.

N otice of T e n d e e of T r a n sc r ipt of E v id en ce and fob

C er t ific a t io n T h e r e o f

Yon are hereby notified that on the 8th day of April,

1959, at 9 :30 o’clock A. M., or as soon thereafter as may be

heard, in the Chambers of Honorable W. Moscoe Huntley,

Judge of Hustings Court of City of Richmond, Virginia,

the undersigned will tender the original transcript of the

evidence, reduced to writing, in the above styled cause and

respectfully ask the said Judge to certify the same as a

true copy of the evidence in the above styled cause.

Bruce Boynton, By Martin A. Martin, Of Counsel for

Appellant.

Martin A. Martin, Esquire, Clarence W. Newsome, Esq.,

118 East Leigh Street, Richmond 19, Virginia, Attorneys

for Appellant.

I accept due and timely service of the above notice.

T. Gray Hadden, Attorney for the Commonwealth.

5

[fol. 4]

I n t h e H u st in g s C ourt of t h e C it y of R ic h m o n d

[Title omitted]

To: Thomas R. Miller, Clerk of Said Court:

N otice of A ppe a l and A ssig n m e n t s of E rror— Filed

April 7, 1959

Notice of Appeal

Notice is hereby given that Bruce Boynton appeals in

this case and will apply for a writ of error and supersedeas.

Assignments of Error

The following are the errors assigned:

1. The court erred in refusing to strike the Common

wealth’s evidence and dismiss this prosecution on the

ground that the defendant was an interstate passenger

traveling in interstate commerce and the local segregation

rules and regulations of the carrier were not applicable to

defendant and were no basis for the prosecution.

2. The court erred in refusing to strike the evidence and

dismiss the prosecution in that the statute as applied in this

case discriminated against defendant on account of his race

and color and denied him the equal protection of the laws.

3. The court erred in holding that defendant violated

the statute by violating the rules and regulations of the

restaurant company since such rules and regulations denied

the defendant due process of law and the equal protection

of the laws.

4. The court erred in refusing to dismiss the prosecution

on the ground that the statute as applied unconstitutionally

attempts to regulate commerce.

[fol. 5] 5. The Court erred in refusing to dismiss the

prosecution on the ground that the statute is an unconstitu-

6

tional and unlawful delegation of state police power to the

restaurant company.

Bruce Boynton, By Martin A. Martin, Of Counsel.

April 7,1959,

Service Accepted:

T. Gray Hadden, Attorney for the Commonwealth.

[fol. 6]

I n t h e H u st in g s C ourt op t h e C it y op R ic h m o n d

[Title omitted]

M otion to D ism iss W arrant

Defendant moves the Court to dismiss the warrant issued

against him for the following reasons:

1. Defendant, on the date of the warrant, was an inter

state passenger and was in the restaurant operated by the

carrier’s lessee for the carrier’s passengers and others.

The statute as applied contravened his rights under the

Interstate Commerce Clause to the Constitution and under

the Interstate Commerce Act.

2. The said restaurant was an integral part of the bus

service for its passengers traveling in interstate commerce,

and the statute as applied to defendant in this case dis

criminates against him on account of his race and color,

and denies him the equal protection of the laws.

3. In enforcing the custom or rules and regulations of

the restaurant against this defendant on account of his

race and color, the State denies this defendant due process

of law and the equal protection of the laws under the Con

stitution of the United States.

4. The statute as applied is unconstitutional as it at

tempts to regulate the interstate commerce contrary to the

Constitution and Laws of the United States.

7

5. The statute is unconstitutional as an unlawful delega

tion of State Police Power to the restaurant company.

Bruce Boynton, Defendant, By Martin A. Martin,

Counsel.

Martin A. Martin, Esq., 118 East Leigh Street, Richmond

19, Virginia, Attorney for Defendant.

[fol. 7]

I n t h e H u stin g s C ourt of t h e C it y of R ic h m o n d

M in u t e E n tr y of H earing—February 4, 1959

Be it remembered that heretofore, to-wit; in the Police

Court of this City the defendant was convicted as charged

in the foregoing warrant, which conviction was appealed

to this Court, and at a Hustings Court held for the City

of Richmond, at the Courthouse, on the 4th day of Feb

ruary, 1959, the following order was entered:

Appeal.

C o m m o n w ea lth

vs

B ru ce B o y in g to n , Dft.

The said defendant this day appeared and was set to the

bar in the custody of the Sergeant of this City and being

arraigned pleaded not guilty to unlawfully remaining on

the premises of the Bus Terminal Restaurant of Richmond,

Inc., after having been forbidden to do so by S. S. Rush,

Assistant Manager of the Bus Terminal Restaurant of

Richmond, Inc., the said S. S. Rush being then and there

lawfully in charge of said premises, there situate in the

said City of Richmond, as charged. And with the consent

of the accused, given in person, and the concurrence of the

Court and the Attorney for the Commonwealth, the Court

proceeded to hear and determine this case without a jury.

And it being agreed to submit the case to the Court on the

stenographic record of the evidence heard in the Police Court

of this City, the Court doth continue this case to February

20, 1959, at 2 :30 P. M. to hear argument of counsel. And

thereupon the said defendant is released on continuing bail.

[fol. 8]

I n t h e H u stin g s C ourt oe t h e C ity of R ic h m o n d

[Title omitted]

S t ip u l a t io n of F acts and A t t a c h m e n t s

It is hereby stipulated and agreed by and between the

Commonwealth of Virginia and Brnce Boynton, by their

respective attorneys, as follows:

1. Stanley Sylvanius Rush, Russell Forest Stout, and

Bruce Boynton if called and sworn as witnesses would give

the same testimony which they gave at the hearing in Police

Court on January 6, 1959, a transcript of which hearing is

attached hereto and made a part hereof.

2. On December 20, 1958, the date of the offense charged

in the warrant, there was no enforced racial segregation,

by law or otherwise, in any of the facilities of the Trailways

Bus Terminal, Ninth and Broad Streets, Richmond, Vir

ginia, other than in the restaurant adjacent to said facili

ties and in the same building. The attorney for the Com

monwealth objects to the admissibility of the facts stated

in this paragraph on the grounds that they are immaterial

[fol. 9] and irrelevant to the issues of the case.

3. Attached hereto is a true and correct copy of the lease

in force and effect between Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc.,

and Bus Terminal Restaurant of Richmond, Inc., on De

cember 20, 1958, the date of the offense charged in the

warrant; and the Bus Terminal Restaurant of Richmond,

Inc., was operating under said lease at said time. The

defendant, by counsel, objects to the admissibility of the

facts stated in this paragraph on the grounds that they

are immaterial and irrelevant to the issues of the case.

Commonwealth of Virginia, By T. Gray Hadden,

Attorney for the Commonwealth.

Bruce Boynton, By Martin A. Martin, Counsel for

the Defendant.

9

[fol. 10]

A t t a c h m e n t to S t ip u l a t io n — L ease B e t w e e n T railw ays

Bus T e r m in a l , I n c ., and B us T e r m in a l R esta u ra n t of

R ic h m o n d , I n c ., D ated D ec em b er 2, 1953

This Agreement, made and entered into this 2nd day of

December, 1953, by and between Trailways Bus Terminal,

Inc., a Virginia corporation with its principal offices in the

City of Richmond, Virginia, party of the first part, herein

after called “Lessor”, and Bus Terminal Restaurant of

Richmond, Inc., a Virginia corporation with its principal

offices in Norfolk, Virginia, party of the second part, here

inafter called “Lessee”.

W l T N E S S E T H :

That Whereas, Lessor is constructing a bus station in

the City of Richmond, Virginia, on the premises located

at the Northwest corner of Broad and Ninth Streets; and

Whereas, there is contained in said bus station facilities

for the operation of a restaurant, soda fountain, and news

stand; and

Whereas, Lessee desires to lease from Lessor facilities

for the operation of the restaurant, soda fountain, and news

stand, hereinafter fully described, for the term and upon

the terms and conditions hereinafter specifically set forth;

Now, Therefore, This Agreement Witnesseth: That the

parties hereto do mutually covenant and agree as follows:

L essor’s Covenants

Lessor, in consideration of the sums to be paid by Lessee,

as hereinafter provided, and of the covenants and agree

ments herein expressed, hereby covenants and agrees with

Lessee as follows:

1. Lessor does hereby lease and demise unto Lessee sub

ject to the terms and conditions hereof, for the term and

at the rental herein provided for, space in the said Trail-

ways Bus Station, for use by Lessee as a restaurant, lunch

room, soda fountain, and news stand, which said space is

more particularly described as follows:

10

That certain space in the basement and on the ground

floor of the Trailways Bus Terminal to be constructed

at the Northwest corner of Broad and Ninth Streets

in the City of Richmond, Virginia, and is shown out

lined in red on the two diagrams hereto attached and

made a part hereof, marked Exhibit A and Exhibit B,

respectively.

2. Lessor hereby grants to Lessee for the term and at

the compensation hereinafter mentioned, and upon the cove

nants, conditions, limitations, and agreements hereinafter

contained, the sole and exclusive right, permission, license

and privilege to sell and serve in the demised space, news

papers, periodicals, magazines, books, stationery, cigars,

[fol. 11] cigarettes, tobacco, food, meals, edibles of all kind,

candy, confections, gum, soda water, soft drinks, ice cream,

fruit, popcorn, nuts, souvenirs, toys, novelties, and all other

articles and commodities, commonly sold at news stands,

cigar stands, restaurants, soda fountains, and lunch coun

ters; provided, however, that Lessee shall not operate in

or upon the demised premises any coin controlled machines

or vending machines of any kind or nature whatsoever ex

cept upon written consent of Lessor.

3. The right, permission, and license hereby granted to

Lessee by Lessor is exclusive, and Lessor shall not sell, or

grant similar permission for the sale of the same, or similar

articles by any other person, firm or corporation in any

other part of said bus station, or on any of the grounds

adjacent thereto over which Lessor has control.

4. Lessor shall keep and maintain the building in which

the Lessee’s premises are situated in good order, condition

and repair, including the painting of the interior walls of

the leased premises at such time or times as in the opinion

of the Lessor might be reasonably necessary.

5. Lessor shall furnish overhead lights, water and heat

for the demised premises; provided, however, that Lessee

shall furnish, at its own expense, electricity for the heating

of water or for any other purpose that electricity might be

used by Lessee except for overhead lights.

11

L essee’s Covenants

Lessee hereby covenants and agrees with Lessor as fol

lows :

6. Lessee shall accept, lease and use, subject to the con

ditions and for the term hereof, the leased premises as

aforesaid, and shall use said space and facilities for the

installation, maintenance and operation of a restaurant,

lunch room, soda fountain and news stand, and for no other

purpose, with the privilege to sell in the demised premises,

newspapers, periodicals, magazines, books, stationery, ci

gars, cigarettes, tobacco, confectionery, candy, popcorn,

[fol. 12] peanuts, novelties, flowers, soda water, soft drinks,

ice cream, and to sell such other articles and food stuffs

in connection with the operation of the restaurant, lunch

room, soda fountain, and news stand as are customarily

sold in the regular course of business of restaurants, lunch

rooms, soda fountains, and news stands. The prices charged

by Lessee therefor shall be just and reasonable. No obscene,

indecent, or other objectional publications, or photographs

shall be offered for sale. Beer and wine shall not be sold

on the leased premises.

7. Lessee agrees to discontinue the sale of any com

modity that may be objectionable to the Lessor, and Lessee

further agrees that it will obtain permission from Lessor

to sell any commodity not usually sold or installed in a bus

terminal concession before so doing.

8. As a basis for computing the rental due hereunder

Lessee shall furnish to Lessor on or before the fifth day of

each calendar month during the term hereof a full and

complete, true and accurate statement showing the gross

receipts of Lessee from the operation of the restaurant,

lunch room, soda fountain, and news stand herein provided

for during the preceding month.

9. Lessee agrees to pay to Lessor, at its office in the City

of Richmond, Virginia, on or before the tenth day of each

calendar month during the term hereof, as rental for the

premises demised and leased herein, and as compensation

for the right, permission, license, and privilege hereby

granted, rental computed as follows:

12

(a) The sum of $30,000.00 annually for gross receipts of

Lessee from sales of Lessee upon the leased premises up

to and including the total annual sum of $275,000.00, which

said rental shall be payable in advance at the rate of

$2,500.00 per month, on or before the fifth day of each

calendar month during the term hereof.

(b) For gross receipts of Lessee for sales made by Lessee

upon said leased premises in excess of the sum of $275,000.00

annually, Lessee shall pay unto Lessor the additional sum

of twelve per cent (12%) of all gross receipts of Lessee in

excess of said sum of $275,000.00, which said rental shall

be due and payable by Lessee within ten (10) days from the

end of each year during the term hereof. The statements

[fob 13] furnished by Lessor by Lessee under the provi

sions of paragraph 8 hereof shall be used in computing

such additional rental that might be due by Lessee to Lessor

at the end of each year of the term hereof.

The term “Gross Receipts”, as herein used shall not in

clude the receipts by Lessee from the sale of tobacco prod

ucts on the demised premises.

Lessee shall also deduct from said gross receipts all

sales taxes and federal excise taxes in the manner pre

scribed by law for the purpose of computing the rental due

Lessor.

10. Lessee shall equip the restaurant, lunch room, soda

fountain, and news stand at its own expense with the neces

sary movable fixtures and furniture and fixed equipment,

including counters, tables, chairs, kitchen equipment, soda

fountain, news stand, stoves, refrigerators and any and

all equipment which may be reasonably necessary or inci

dent to the operation of a restaurant, lunch room, soda foun

tain, or news stand. Such equipment, fixtures, and furni

ture shall be maintained and kept in first class condition,

good order and repair by Lessee at all times at Lessee’s

own expense, and Lessee shall replace such equipment, fix

tures and furniture with articles of the same kind and

equally good when necessary in the opinion of Lessor.

Lessee shall obtain the approval of Lessor as to the quality

of all the equipment, fixtures and furniture, to be installed

by Lessee upon the leased premises.

13

11. Lessee shall equip said restaurant, lunch room, soda

fountain, and news stand at its own expense with the neces

sary silver ware, china ware, glass ware, linen, kitchen

utensils, or any and all articles necessary or used in con

nection with any or all of the foregoing, and Lessee shall

maintain such equipment in good order and repair at all

times and shall renew the same when necessary.

12. All equipment, fixtures, and furniture to be installed

by Lessee upon the demised premises shall be approved

by Lessor in writing, as to the quality of any and all such

equipment, fixtures, and furniture; and if at any time during

the term hereof Lessee desires to change the location, man

ner and means of installing any equipment necessary to

connect with plumbing, heating, gas, or electric wiring

facilities contained in said bus station Lessee shall obtain

[fol. 14] prior approval in writing of Lessor before making

any such change. Such changes, installations, and connec

tions shall be at Lessee’s sole expense.

13. Lessee shall pay for all electric current and electric

power used in connection with the demised premises (ex

cept for overhead lights), shall pay for all gas used in

connection with the operation of the restaurant, lunch

room, soda fountain, and news stand by Lessee, and shall

furnish at Lessee’s own expense such facilities and ap

pliances as are used by Lessee for the heating of vmter in

connection with the use of said leased and demised prem

ises. In the event of the failure of Lessee to pay any or

all of any such charges, Lessor at its option shall have

the right to pay or advance the same in behalf of Lessee,

and in such event such payments, or advancements made

by Lessor in behalf of Lessee shall be chargeable to or

added to the rental due hereunder by Lessee to Lessor.

14. Lessee shall at all times maintain said leased facili

ties in good order, and at the expiration of the term hereof,

or upon surrender of possession of said leased premises

to Lessor by reason of default by Lessee, as herein pro

vided for, the said leased premises will be surrendered to

Lessor in the same condition as at commencement of the

term hereof, ordinary wear and tear excepted.

15. Lessee shall and does hereby assume all risk of loss

or injury to property or persons of all officers, agents and

14

employees or customers of said Lessee, or other persons

coming upon the leased premises at the instance of or with

the consent or knowledge of Lessee, and Lessee shall and

does hereby agree to indemnify and save harmless Lessor

from and for any and all claims, demands, suits, judgments,

costs or expenses on account of such loss or injury. If suit

be brought again Lessor upon any claim in respect of which

under the terms hereof Lessor is entitled to protection and

indemnity, Lessee, upon notice of such suit, shall assume

the defense thereof.

Lessee covenants that it will carry public liability insur

ance in a company or companies satisfactory to Lessor in

an amount of not less than Twenty-live Thousand Dollars

($25,000.00) to cover any or all of the foregoing, which

insurance shall run in favor of Lessee and Lessor.

[fol. 15] 16. Lessee shall not, at any time of the term

hereof, make any alteration or addition in or to the leased

premises without the prior written consent and approval of

Lessor.

17. Lessee shall not assign or sublease the premises

hereby leased, or any part thereof, or assign or transfer

any right, permission, license or privilege hereby granted

without first obtaining the written consent of the Lessor.

18. Lessee’s employees shall be neat and clean in ap

pearance, and the operation of the restaurant and the

said stands shall be in keeping with the character of service

maintained in an up-to-date, modern bus terminal. Any

employees not conducting themselves in keeping with the

requirements of this service or found to be of unsatisfactory

character shall be reported by the Lessor to the Lessee for

correction and if same is not corrected within a reasonable

time, the Lessor may request removal of or dismissal of

such unsatisfactory employees. Neither the Lessee nor its

employees shall be allowed to perform any terminal service

other than that pertaining to the operations outlined in

this contract; nor shall Lessee or its employees sell trans

portation of any kind or give information pertaining to

schedules, rates or transportation matters, but shall refer

all such inquiries to the proper agents of Lessor.

19. Lessee shall maintain and operate the restaurant

and lunch room in the demised premises in a manner so as

15

to keep a Grade A certificate therefor, and upon the failure

of Lessee to so do, Lessor may terminate this lease in the

manner described in paragraph 27 hereof; provided, how

ever, that if and in the event the restaurant and lunch room

in the demised premises shall receive a rating lower than

a Grade A certificate through no fault of Lessee, because

of conditions prevailing in said bus station, then the right

of Lessor to terminate this agreement because of such rat

ing shall not become effective until Lessor has corrected

such conditions in the bus station premises that caused

such low rating.

M utual Covenants

The parties hereto severally covenant and agree with each

other as follows:

[fol. 16] 20. This Agreement in every provision hereof

shall insure to the benefit of and be binding upon Lessor

and Lessee, and their respective heirs, successors, and as

signs. The words “Lessor” and “Lessee” wherever used

herein shall include the heirs, successors, and assigns of the

respective parties hereto.

21. In the event the station building in which the leased

premises are located is rendered wholly untenatable by fire

or otherwise, Lessor may at its option, either immediately

cancel or terminate this lease, or else, to restore or rebuild

within a reasonable time said bus station building includ

ing the premises, leased hereunder, in the same condition

at they were at the time of the commencement of the term

hereof. In the event of such cancellation and termination

of said lease by Lessor, the rental due by Lessee shall

cease on and as of the date of such termination, and in

the event the premises are rebuilt or restored, Lessee shall

not pay rent to Lessor during such term as the premises

are wholly untenantable.

22. Any notice to be given or required to be given to

the Lessee under the terms hereof shall be deemed suffi

cient if delivered or mailed to the agent of Lessee in charge

of the demised premises, and any notice given or required

to be given to Lessor shall be deemed sufficient if delivered

or mailed to Lessor addressed to the General Manager,

Trailways Bus Terminal, Inc., Richmond, Virginia.

16

23. Lessee shall pay any and all taxes of any kind or

nature whatsoever, including license for privilege taxes, that

are lawfully due and payable to any existing governmental

body arising from or in connection with the business con

ducted by Lessee on leased premises, or on the furniture,

fixtures and equipment installed therein by Lessee.

24. Lessor shall operate said bus terminal in said bus

station building in accordance with the rules and regulations

of any lawful governmental agency having jurisdiction

thereof; and it is understood by and between the parties

hereto that this Agreement and all provisions herein con

tained are subject to all valid rules and regulations of such

regulatory authorities having jurisdiction thereof during

the full term hereof. Lessee shall comply with all the ordi

nances of the City of Richmond, and the laws of the United

States and the State of Virginia in respect to the conduct

of business of Lessee on the demised premises.

[fol. 17] 25. Lessee shall not make any sales on buses

operating in and out said bus station; but sales through

the windows of said buses may be made by Lessee, pro

vided, however, that Lessee shall cease making sales

through windows of buses within thirty (30) days after

receipt of notice in writing from Lessor to terminate such

sales.

26. Lessee hereby grants to Lessor the right at any and

all times hereof to examine the books, records, cash register

accounts and vouchers of Lessee for the purpose of verify

ing the accuracy of gross receipts of Lessee as are furnished

to Lessor under the terms hereof. It is understood that

such examination or audits shall be made by Lessor at least

semi-annually during the term hereof.

27. If Lessee shall fail to pay to Lessor any sum pay

able by Lessee hereunder on or before the date when the

same shall become due, or shall fail to perform, or comply

with any covenant or condition contained herein, and such

default shall continue for a period of ten (10) days after

notice in writing from Lessor to Lessee, then and in such

event Lessor shall have and is hereby given, the right of

its election to exclude Lessee from the use of the leased

premises, and upon giving ten (10) days notice in writing

17

of such election to Lessee, all rights of Lessee to use the

leased premises, and any and all other rights of Lessee

hereunder shall then and there be terminated and Lessor

shall have the right to enter upon the demised premises;

but such termination shall not relieve Lessee from any lia

bility that might have been accrued prior to the date of

such termination.

28. Upon the termination of this Agreement, Lessee shall

promptly surrender to the Lessor possession of the prem

ises hereby leased, exclusive of stands, counters, soda foun

tain, and other equipment furnished or installed by or at

the expense of the Lessee, which are to be deemed the per

sonal property of the Lessee and may be removed by him,

provided Lessee is not in arrears in rent, and in the event

Lessee is in arrears, then Lessor may sell so much of said

personal property as is necessary to satisfy the claims for

rent. Upon the termination of the Agreement, Lessee shall

promptly remove all equipment, fixtures, and furniture in

stalled by Lessee in the demised premises, at Lessee’s sole

expense, and restore the premises to the same condition

that they were at the commencement of the terms hereof,

ordinary wear and tear excepted.

[fol. 18] 29. The term hereof shall be for the period of

five (5) years, beginning Dec 2, 1953, and ending Dec 2,

1958; provided, however, that this lease shall be auto

matically renewed for an additional term of five (5) years

unless either party hereto shall notify the other party

hereto, in writing at least ninety (90) days prior to the

expiration date of the five-year term hereof, of the desire

of such party to cancel and terminate this lease. In the

event the leased premises described in paragraph 1 hereof

are not completed and ready for occupancy by Dec 2, 1953,

then and in such event the term hereof shall begin on and

as of the date that said leased premises are completed

and are ready for occupancy and shall continue for the full

term of five (5) years thereafter.

I n W itn ess W h ereo f , th e p a r tie s h e re to h av e executed

th is in s tru m e n t on th e d ay an d y e a r f irs t above w ritten .

T railways B us T erm inal, I n c .

By / s / R . C. H o ffm an , J r.

President

18

A ttest :

/ s / R . B. S m all

Secretary

Bus T e r m in a l R esta u ra n t of

R ic h m o n d , I n c .

By /s / J. B ernard P arker

A ttest : Pres.

/ s / B ryce W agoner

Secretary

(A dd A ppr o pr ia te A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s)

[fo l. 19] S tate of N o rth C arolina

C o u n ty of W a k e , To-wit:

I, Daisy A. Harris, a notary public in and for the City

and State aforesaid do hereby certify that R. C. Hoffman,

Jr., and R. B. Small, whose names are signed to the fore

going writing bearing date on the 2nd day of December,

1953, as President and Secretary of T railw ays B us T er

m i n a l , I n c ., have acknowledged the same before me in my

City aforesaid.

Given under my hand this 7th day of January, 1954.

My commission expires on the 29th day of April, 1955.

/ s / D aisy A. H arris

Notary Public

S tate of V ir g in ia

C it y of N o r fo lk , To-wit:

I, G. A. Callahan, a notary public in and for the City and

State aforesaid do hereby certify that J. Bernard Parker

and Bryce Wagoner, whose names are signed to the fore

going writing bearing date on the 2nd day of Dec. 1953,

as President and Secretary of Bus T e r m in a l R estaurant

of R ic h m o n d , I n c . have acknowledged the same before me

in my City aforesaid.

Given under my hand this 19th day of December, 1953.

My commission expires on the 13th day of May, 1957.

/s / G. A. C allahan

Notary Public

19

[fol. 20]

A ttach m ent to S tipulation

V ir g in ia :

I n t h e P olice C ourt of t h e C ity of R ichm ond

C ity of R ichm ond

v.

B ruce B oynton

TRIAL PROCEEDINGS

January 6, 1959.

10:15 a. m.

Before Honorable Harold Maurice, Judge

A ppea ra n ces:

Charles E. Maurice, Assistant Commonwealth’s Attor

ney, For the City of Richmond.

Hill, Martin, and Olphin, Counsel for Defendant, By

Martin A. Martin.

Also present:

Walter E. Rogers, For the Bus Terminal Restaurant

Company, Incorporated.

[fo l. 21] P r o c e e d i n g s

Mr. Rogers: Your Honor, I represent the Richmond Bus

Terminal Restaurant and am appearing with the Common

wealth’s Attorney.

The Court: Bruce Boynton, on the 20th day of December,

did trespass upon the premises at the Trailways Bus Ter

minal, Ninth and Broad Streets. What is his plea?

Mr. Martin: Not guilty.

E vidence A dduced in B eh a lf of th e C ity

S tanley S ylvanius B u s h , having been sworn, in behalf

of the City testified as follows:

Direct examination.

By Mr. Rogers:

Q. Mr. Bush, you are the Assistant Manager of the Bus

Terminal Restaurant in Richmond, Incorporated, are you

not!

A. Yes, sir.

Q. That is located at the Trailways Bus Terminal here

at Ninth and Broad?

A. That’s right, sir.

Mr. Martin: Pardon me a minute. I wonder if we could

get his full name and address for the record.

[fol. 22] By Mr. Rogers:

Q. Will you state your full name and address ?

A. My name is Stanley Sylvanius Rush. I live at 2200

Mimosa Street, Richmond, Virginia.

Q. And you are Assistant Manager of the Richmond Bus

Terminal Restaurant in Richmond?

A. I am.

Q. That company leases space in the building there at

Ninth and Broad for the purpose of operating a restaurant,

does it not?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. The company that operates the restaurant is not

affiliated in any way with the bus company, is it?

A. No, sir, it is not.

Q. The bus company has no control over the operation

of the restaurant?

A. None whatsoever.

Q. What facilities do you have at the restaurant for

serving both white and colored, Mr. Rush?

A. We have a restaurant on one side for colored; we

have one restaurant for the white.

21

Q. Were yon on duty on December 22, when the defendant

Bruce Boynton came into the white portion of the restau

rant and asked to be served!

A. Yes, 1 was.

[fob 23] Q. Will you tell the Court what happened!

A. When he came in he seated himself in the white

section. He was asked to leave and go over. I explained

to him that they had a restaurant on the other side for

the colored and we would appreciate it if he would go over

there, at which time he demanded service there. I went to

him then and talked to him and tried to explain to him the

situation, at which time he refused to leave, demanded

service.

I then called the officer to come over and see if he could

get him to leave, that he was causing a disturbance there,

which the officer could, he went out and tried to explain

to him the situation and came back and told me—asked

me if I wanted a warrant for this man’s arrest and I told

him I would rather not, if he would stay out of the place

that that would be all that was necessary, which I looked

up and he had returned to the restaurant and seated himself

again. After seating, he got up and came forward towards

the end of the counter, which is part of the aisleway behind

the counter section, at which time I asked the officer to

call the magistrate, that I would issue a warrant for his

arrest for trespassing.

Q. You definitely asked him and instructed him to leave

the white portion of the restaurant and advised him he

could be served in the colored portion!

A. I did.

[fol. 24] Q. And he returned after you had instructed him

that he could not be served in the white section!

A. Yes, sir, he did.

Mr. Rogers: That is all.

Cross examination.

By Mr. Martin:

Q. Mr. Rush, I just want to be clear on this. You say

you are Assistant Manager of what!

A. Bus Terminal Restaurant Company.

22

Q. Company, Incorporated?

A. That’s right.

Q. A Virginia corporation!

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You are the Assistant Manager?

A. I am Assistant Manager.

Q. What first called your attention to this young mail

here being in the restaurant? Did one of the waitresses

call your attention to the fact?

A. I had seen him in there. At the time I was busy and

couldn’t get to him myself to explain the situation, which

everyone has been instructed to always—

Q. Just a minute. I am not asking about your instruc

tions. Who first called your attention to him being in the

restaurant?

[fol. 25] A. I saw him myself.

Q. Did a waitress later call your attention to the fact?

A. Yes.

Q. You say you have two restaurants there, one cus

tomarily used for colored people and one 'white?

A. That’s right.

Q. What is the approximate size of the colored restau

rant ?

A. I believe the seating capacity is that of about fifty.

Q. What is the area space ?

A. I don’t know that right offhand. I can give you that.

Q. About twenty-five or thirty feet?

A. No, it is more than that.

Q. This happened on a Saturday night, I believe, Decem

ber 22?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. About what time ?

A. Approximately ten-thirty.

Q. Colored restaurant was crowded at that time?

A. No. We had customers in there, but there was seating

capacity.

Q. What is the seating capacity of the white restaurant?

[fol. 26] A. That, I don’t know exactly either, I would

have to look that up.

Q. You have tables and stools at the counter in the white

restaurant ?

A. Yes, sir.

23

Q. Where was this defendant seated, at the table or stool?

A. At a stool.

Q. He was seated at a stool at the counter?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. When this waitress complained, didn’t she tell you

that he was asking for a sandwich and cup of tea?

A. She didn’t tell me what he was asking for.

Q. But he was asking for service?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You knew that he was a passenger on the Trailways

bus?

A. At that time, no.

Q. You didn’t ?

A. No.

Q. Before he was arrested, you knew he was a passenger

on the bus, didn’t you?

A. But I said at that time.

Q. Didn’t he show you a ticket? Didn’t he tell you that

[fol. 27] he was a passenger on the Trailways bus from

Washington going to Montgomery, Alabama?

A. After I had sent to the magistrate for his arrest,

then his ticket was produced.

Q. And you knew at the time the magistrate came and

you issued the warrant that he was a passenger on this bus

going from Washington to Montgomery, Alabama?

A. I said until the magistrate issued the warrant was the

ticket then produced.

Q. Did he do anything else besides ask for service there

at the restaurant and just remain there when he was asked

to leave ?

A. No, he got up and walked up and down the aisle de

manding service from the waitress and telling her that she

had better talk to me and have service right there or else

he was going to do this, that, and the other.

Q. Your restaurant is primarily or partly for the service

of the passengers on the Trailways bus ?

A. For the white on that side, colored on the other.

Q. It is for passengers on the bus, for white passengers ?

A. Not necessarily, no. We have quite a bit of business

here from local people.

24

Q. If he had been a white person, would you have refused

[fol. 28] him service, if he had been a white passenger on a

Trailways bus at that time, that particular time, would

you have refused him service?

A. Walking up and down the aisle, demanding service

immediately, I probably would have.

Q. When he was setting at the stool at the counter ask

ing for a sandwich, if he had been a white person would

you have given him service ?

Mr. Rogers: If Your Honor please, this seems to be

going afield. The testimony indicates that the restaurant

is operated entirely separate from the bus terminal and he

was asked to leave.

The Court: He can ask the question, but I do not think

it is going to be anything to connect the bus company up

with the restaurant. Go ahead.

Mr. Martin: Will you answer that question ?

A. If he had been—

By Mr. Martin:

Q. If he had been a white person seated at the counter

on a stool, would you have instructed the waitress to give

him service?

A. I said no, not necessarily.

Q. Why?

[fol. 29] A. If any passenger or any person comes in and

starts creating a disturbance, we immediately ask them to

leave.

Q. Mr. Rush, I did not ask you that question. Can’t you

answer the question that I asked you? I asked if he was

a white passenger seated at the stool, as you said he was

seated at the counter, and asked for service, would you have

given him service?

A. I said no, not necessarily.

Q. Why not?

A. Anyone that creates a disturbance I would have asked

him to leave, which he was doing at that time when he

started that. That is when he returned the second time

is when I got the warrant, not the first time.

25

Q. Why didn’t yon get a warrant charging him with

creating a disturbance if he was creating a disturbance ?

A. Because I only wanted trespassing.

Q. Why?

A. Because I had asked him to leave and he refused to

leave.

Q. So the only crime you know that he was guilty of was

trespassing?

A. That is what I took the warrant for.

Q. When this waitress came to you and told you that

he was over there, didn’t she tell you that he was asking

[fol. 30] to be served?

A. Yes.

Q. And she refused to serve him?

A. Yes.

Q. Because of his race?

A. She refused to serve him because we have a restaurant

on the other side, which she tried to explain to him.

Mr. Martin: That is all.

Mr. Rogers: No questions.

R ussell F orest S tout, having been sworn in behalf of

the City, testified as follows:

Direct examination.

By Mr. Rogers:

Q. You are the officer that made this arrest?

The Court: Let him state his name and occupation.

The Witness: Russell Forest Stout; patrolman, Rich

mond Police.

By Mr. Rogers:

Q. Officer Stout, you were on duty at the restaurant, at

the Bus Terminal, at the time of this occurrence ?

A. Yes, sir.

[fol. 31] Q. You are familiar with what took place ?

A. Yes, sir.

26

Q. Is it substantially as related by Mr. Rush.?

A. Yes, sir.

Mr. Rogers: No questions.

Cross examination.

By Mr. Martin:

Q. Did you see any disorderly conduct?

A. Not too much. He was disturbing the peace some.

Q. But just by being in there, a colored person in a white

restaurant?

A. Not necessarily that. He was raising his voice a cer

tain amount.

Q. There was no profane language nor cursing or any

thing ?

A. No, I didn’t hear any.

Q. No fighting or fussing?

A. No.

Redirect examination.

By Mr. Rogers:

Q. Was the waitress around when he was demanding

service in the restaurant?

[fol. 32] A. I wasn’t in there. He was standing up. Mr.

Rush told me that he had.

Recross examination.

By Mr. Martin:

Q. And you arrested him and put him in the patrol wagon

and took him to the station?

A. On the warrant.

Mr. Martin: Any other witness ?

Mr. Rogers: No.

27

E vidence A dduced in B eh a lf of D efendant

B ruce B oynton , th e d e fen d an t, w as sw orn , an d in h is own

b eh a lf te s tified as fo llo w s :

Direct examination.

By Mr. Martin:

Q. Will you state to the Court your name and your home

address?

A. If it please the Court, my name is Bruce Boynton, and

my home is address is 1315 Lapsley Street, Selma, Ala

bama.

Q. Are you at the present time attending school?

[fol. 33] A. Yes, sir, I am.

Q. Where?

A. I am a third-year student at Howard University,

at law school.

Q. On this particular occasion, were you traveling from

Washington, D. C., at school to your home in Selma, Ala

bama?

A. Yes, sir. I was traveling from Washington, D. C.

Q. Just answer the question. Were you traveling from

Washington, D. C., to your home in Selma, Alabama?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. By Trailways bus ?

A. Yes, by Trailway to Montgomery.

Q. Did you have a ticket entitling you to travel by Trail

way bus from Washington to Montgomery, Alabama?

A. Yes, sir, I did.

Q. Is that a stub of that ticket (exhibiting) ?

A. That is the stub.

Mr. Martin: If Your Honor please, I offer this in evi

dence.

(The ticket stub was exhibited and retained by counsel

for the defendant.)

Q. What time did you board the Trailway bus in Wash-

[fol. 34] ington?

A. I boarded the Trailways bus at eight o’clock.

28

Q. What time did you arrive in Richmond?

A. About 10:40.

Q. Why did you get oft the bus in Richmond?

A. I got oft the bus in Richmond because I was hungry

and we had a stopover of about forty minutes.

Q. Who told you about the stopover?

A. The bus driver, when he pulled the bus up to the stop

at the terminal.

Q. At the time, did you know anybody in Richmond?

A. No, no one except a couple of students, classmates of

mine.

Q. And the bus driver told you you had about a forty-

minute layover and you went in the bus station for what

purpose?

A. To get something to eat.

Q. Did you see the colored restaurant there?

A. Yes, sir, I did.

Q. What was the condition ?

A. The colored restaurant appeared to be crowded and

I proceeded to the other restaurant.

Q. Was that other restaurant crowded?

A. No, it wasn’t.

Q. There are stools at the counter?

[fol. 35] A. Yes, sir.

Q. Vacant stools?

A. Vacant.

Q. Where did you sit?

A. I took one of the vacant stools at the counter.

Q. What did you say? Just tell the Court what hap

pened.

A. Well, at the time that I sat down the waitress—one

of the waitresses on duty came up to me and asked me to

go over on the other side, that they had facilities over

there. I told the waitress that the facilities over there were

a bit crowded and also that I was an interstate passenger

and that I could eat there at that restaurant. She told me

that she had orders and it was customary not to serve me.

Whereupon I explained to her again that I was an inter

state passenger and that I had a bus to catch in about

thirty minutes, thirty or forty minutes, and that I would

like something that wouldn’t take too long to prepare.

29

Whereupon she suggested that I purchase a prepared sand

wich, sandwich that was already made. I believe they had

some several lined up to the counter there. So I ordered

one of the sandwiches and tea with cream. She didn’t

write the order, but she went away and then came back

and said that she couldn’t serve me, she had orders not

to serve me. Whereupon, I asked her to get someone who

[fol. 36] could since she had orders not to and that I was

an interstate passenger. She went away and Mr. Rush

here appeared and told me that I couldn’t be served and

suggested that I go over on the other side.

At that time I pulled out my ticket, showed it to him,

explained what that passenger was, and he asked me to

move. He made a demand for me to move and I refused.

He went away and I sat there. The next thing that hap

pened was that Officer 198 appeared and told me that I was

under arrest. I explained to him that I was an interstate

passenger also and he conferred, I believe, with Officer 66,

who I later went into the custody of this officer, and they

wrote out a warrant and I proceeded on the bus in the

custody of Officer 198 and took my things off and disem

barked from the bus.

Q. You were placed in a patrol wagon ?

A. That is right.

Q. During this entire time, was any profane language

used, any loud words, curse words, or any disorderly con

duct?

A. No. I just emphatically, I suppose, expressed my

point of view as being an interstate passenger, but not loud,

not boisterous, and I remained sitting.

Q. Did you know any other place? Have you ever been

in Richmond before?

[fol. 37] A. Not for a stop. I have passed through.

Q. Did you know any other place where you could get

anything to eat within thirty or forty minutes ?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. You say the colored restaurant was crowded at that

time?

A. That is right.

Q. And the only thing you did, as I understand, was you

saw the colored restaurant crowded, you went in the white

30

restaurant and sat at the stool and demanded service as a

passenger on the Trailway bus!

A. That is right.

Q. They refused to serve you and ultimately you wound

up being arrested f

A. Yes, sir.

Mr. Martin: That is all.

Cross examination.

By Mr. Rogers:

Q. To clear the record, both the management and the

officer asked you to leave the white portion and advised

you that you could be served in the colored portion of the

restaurant?

A. He did make a demand that I leave.

Mr. Rogers : That is all.

[fol. 38] The Court: That is all of the case ?

Mr. Martin: Yes, sir.

The Court: Find him guilty and fine him $10.00.

Mr. Martin: Rote an appeal, sir.

(Whereupon, at 10:34 a. m., the trial was concluded.)

[fol. 39]

In THE H ustings Court op t h e City of R ichm ond

Appeal.

COM M ONW EAUTH

VS

B ruce B oyington, D ft.

J udgment— February 20, 1959

The said defendant this day again appeared and was

set to the bar in the custody of the Sergeant of this City and

after maturely considering the evidence doth find the said

defendant guilty as charged and doth assess his fine at ten

dollars.

31

Whereupon it is considered by the Court that the said

Bruce Boyington pay and satisfy a fine of ten dollars and

costs. And on his motion the execution of the said sentence

is suspended during his good behavior until March 6, 1959.

[fol. 40]

I n th e H ustings Court of t h e C ity of R ichmond

[Title omitted]

Order Overruling M otion to D ism iss W arrant and

S uspend in g E xecution of S en ten ce—March 6, 1959

The said defendant this day again appeared and was set

to the bar in the custody of the Sergeant of this City and

having been found guilty of unlawful trespass, as entered

herein February 20, and execution of said sentence sus

pended to this day and the said defendant this day having

filed his motion in writing to dismiss the warrant in this

case, which motion was also made at the trial of this case

February 20, 1959 and overruled by the Court, which mo

tion the Court doth again overrule and to which action of

the Court in overruling his said motion the said defendant

notes an exception and time is given him not exceeding

sixty days in which to present his bills of exceptions.

Thereupon the said defendant moved the Court to sus

pend the execution of the sentence to allow him to appeal

to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, which motion

the Court doth grant and the execution of the said sen

tence entered herein February 20, 1959, is this day sus

pended to May 26, 1959. And thereupon the said defendant

entered into a recognizance in the sum of three hundred

dollars with Roberta B. Shores, as surety, conditioned that

if the said Bruce Boyington shall make his appearance

before this Court May 26, 1959, to abide by and perform

the judgment entered against him herein February 20,

1959, in the event the Supreme Court of Appeals should

affirm same or refuse to grant a writ of error, or if same be

granted it be afterwards dismissed, and in the meantime

keep the peace and be of good behavior and not violate any

of the laws of this Commonwealth, then the said recog

nizance to become null and void, else to remain in full force

and virtue. And thereupon the said defendant is released.

32

[fol. 41]

I n t h e H ustings Court of t h e C ity of R ichm ond

[Title omitted]

Order R e T ranscript-—A pril 8, 1959

The transcript of the evidence adduced, the objections

to evidence and other incidents in the trial was this day

signed and sealed by the Court and delivered to the Clerk

of this Court and hereby made a part of the record in this

case.

[fol. 42]

Certification to T ranscript O mitted in P r in tin g

[fol. 43]

I n t h e S u prem e Court of A ppeals of th e

C om m onw ealth of V irginia

Order R efu sin g W rit of E rror—June 19, 1959

The petition of Bruce Boynton for a writ of error and

supersedeas to a judgment rendered by the Hustings Court

of the City of Richmond on the 20th day of February, 1959,

in a prosecution by the Commonwealth against Bruce

Boyington, alias Bruce Boynton, for a misdemeanor, hav

ing been maturely considered and a transcript of the record

of the judgment aforesaid seen and inspected, the court

being of opinion that the said judgment is plainly right,

doth reject said petition and refuse said writ of error and

supersedeas, the effect of which is to affirm the judgment

of the said Hustings Court.

33

[fol. 44]

I n t h e S u prem e Court op A ppeals oe th e

C om m onw ealth op V irginia

[Title omitted]

Order S taying E xecution and E nforcem ent of J udgment

—July 24,1959

On consideration of the petition of Bruce Boynton, by

counsel, for a stay of execution herein, in order that he

may have reasonable time and opportunity to present to

the Supreme Court of the United States a petition for a

writ of certiorari to review the judgment of this court,

It Is Now Ordered that the execution and enforcement of

the judgment of this court in the above-entitled case entered

on June 19, 1959, be, and the same is hereby, stayed until

the 17th day of September, 1959, on the expiration of which

time the same may be enforced, unless the case has before

that time been docketed in the Supreme Court of the

United States, in which event enforcement thereof shall be

stayed until the final determination of the case by that

court.

The above stay, however, is not to discharge the petitioner

from custody, if in custody, or to release his bond if out on

bail.

Willis D. Miller, Justice of the Supreme Court of

Appeals of Virginia.

[fol. 45] Clerk’s Certificate to foregoing transcript (omit

ted in printing).

34

[fol. 46]

S u prem e C ourt oe th e U nited S tates

No. 409, October Term, 1959

B ruce B oynton , Petitioner,

vs.

V irg in ia .

Order A llow ing Certiorari— February 23, 1960

The petition herein for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme

Court of Appeals of the Commonwealth of Virginia is

granted.

And it is further ordered that the duly certified copy of

the transcript of the proceedings below which accompanied

the petition shall be treated as though filed in response to

such writ.

SUITE 1790

10 COLUMBUS CIRCE

O' / YORK 19,N.Y.