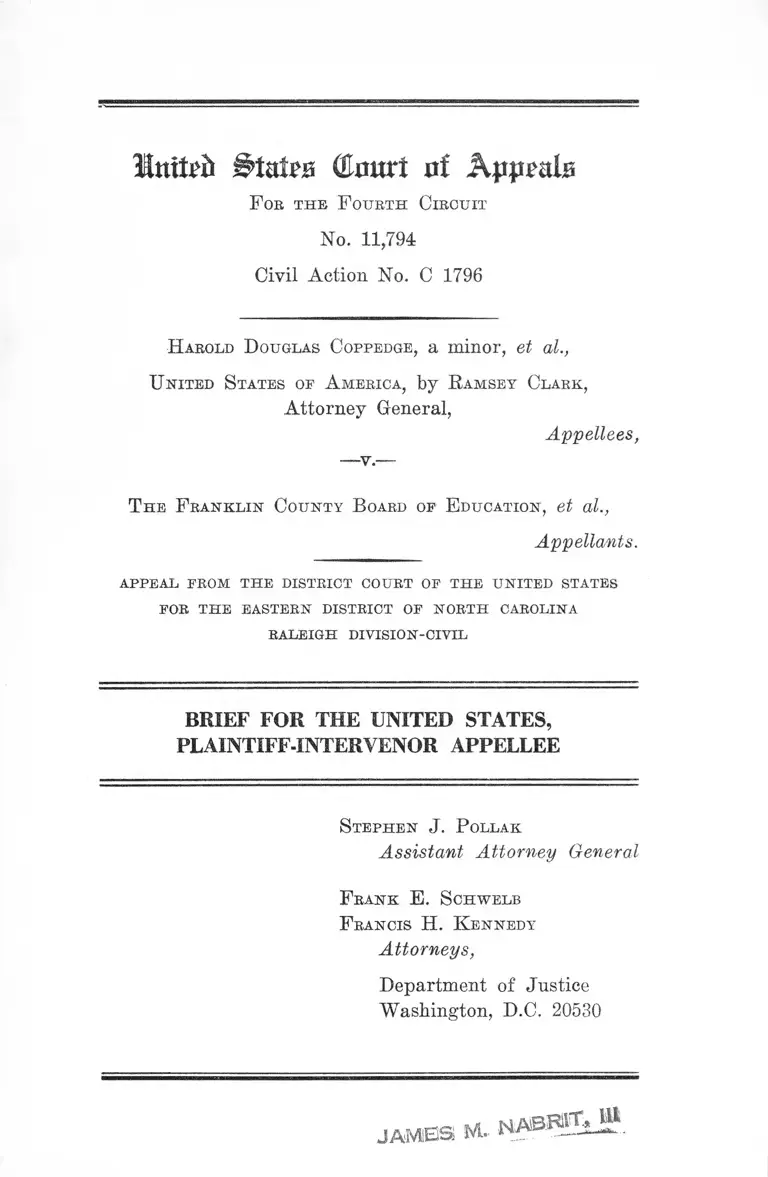

Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Education Brief for the United States

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Education Brief for the United States, 1968. be667c66-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc4e1801-29c9-4f96-b70f-bfd9e326bbc5/coppedge-v-franklin-county-board-of-education-brief-for-the-united-states. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

llmti'i) States (Emtrt of Appeals

F ob t h e F ourth Circuit

No. 11,794

Civil Action No. C 1796

Harold D ouglas C oppedge, a minor, et al.,

U nited States of A merica, by Ramsey Clark,

Attorney General,

Appellees,

—v.—

T he F ran k lin C ounty B oard of E ducation , et al.,

Appellants.

A PPE A L FROM T H E DISTRICT COURT OF T H E U N IT E D STATES

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF N O R T H CAROLINA

R A LE IG H D IV ISIO N -C IV IL

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES,

PLAINTIFF-INTERVENOR APPELLEE

S teph en J. P ollak

Assistant Attorney General

F ran k E. S chw elb

F rancis H. K ennedy

Attorneys,

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

ja m b s

I N D E X

Introductory Statement ................................................... - 1

Proceedings Below ........................................................... - 6

The Evidence........................................................................ 6

I. Defendants’ Adherence to Policies and Prac

tices Which Perpetuate a Dual System Based

on R a ce ...................................................................... 6

A. School Organization and Utilization ........... 6

B. Assignment of Staff and Faculty.........................9

C. Disparities ......................................................... - 13

D. Transportation .................................................. 17

II. Pressures Inhibiting the Exercise of Free

Choice ....................................................................... 23

A. Community Attitudes ...................................... 24

B. Acts of Intimidation........................................... 26

C. Defendants’ Attempts to Refute the Proof

of Intimidation -................................................. 31

D. The Legal Effect of Community Attitudes

and Intimidation on the Constitutionality of

the Freedom of Choice P la n .......................... 37

PAGE

Conclusion 44

11

Cases

page

Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City

County, Va., 382 F.2d 326 (4th Cir. 1967) ....11, 23, 38, 40

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) .......11,43-44

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 11,13,17

Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Education,

273 F. Supp. 282 (E.D.N.C. 1967); 12 Race Eel.

L. Eep. 230 (E.D.N.C. 1966) .............................. 1, 3, 6, 37

Corbin and United States v. County School Board of

Loudoun County, V a .,------F. Supp.------- , C.A. No.

2737 (E.D. Va., Aug. 29, 1967) .......................... 19, 20, 22

Cypress v. Newport News Gen. Hospital, 375 F.2d 648

(4th Cir. 1967) ..............................................................38, 40

Dallas Co. v. Commercial Union Assurance Co., 286

F.2d 388 (5th Cir. 1961) .............................................. 33

Darter v. Greenville Hotel Corp., 301 F.2d 70 (4th

Cir. 1962) .............................................................. .......... 24

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala. 1949),

aff’d 336 U.S. 933 (1949) .............................................. 33

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), afif’d 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir. 1967), cert. den. 387 U.S. 931 (1967) ................... 12

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S.

683 (1963) ..............................................................

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

649 (E.D. La. 1961), aff’d 368 U.S. 515 (1962) ....... 33

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir. 1966) 30

I l l

Kelly v. Altheimer, Ark. School Dist., 378 F.2d 483

(8th Cir. 1967) ..............................................9,12,16,17,19

Kelly v. Board of Education of City of Nashville,

270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959) ...................................... 39

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) ........... 22

Kiev v. County School Bd. of Augusta Co., Va., 249

F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va. 1966) .......................10,12-13, 34

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala. 1967) (three judge court) ...............8, 38

Moses v. Washington Parish, La. School Board, —*—

F. Supp.------ (C.A. No. 15973, E.D. La., October 19,

1967) ........................................................................... 9,21,22

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ........................ . 11

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ..........................9,22

Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 369

F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966) ................... 33

Teel v. Pitt County Board of Education, 272 F. Supp.

703 (E.D.N.C. 1967) ...................................................... 43

Thompson v. County School Board of Hanover County,

252 F. Supp. 546 (E.D. Va. 1966) ............................... 12

United States v. Haywood County Board of Education,

271 F. Supp. 460 (W.D. Term. 1967) .......................41-43

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

aff’d 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d on reh. en

banc 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) ....12,13,16,17, 22,40, 41

United States v. Original Knights of Ku Klux Klan,

250 F. Supp. 330 (E.D. La. 1965) (three-judge

court) ............................................................................... 24

PAGE

IV

United States v. State of Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353

(E.D. La. 1963), aff’d 380 TT.S. 145 (1965) ............... 33

Usiak v. New York Tank Barge Company, 299 F.2d 808

(2d Cir. 1962) .................................................................. 33

Vick v. County School Board of Obion County, Tenn.,

205 F. Supp. 436 (W.D. Tenn. 1962) ...................... 26, 39

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d

738 (4th Cir. 1966) .......................................................... 9

Wright v. County School Board, 252 F. Supp. 378

(E.D. Va. 1966) .............................................................. 37

PAGE

O ther A uthorities

U. S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare,

Office of Education: Revised Statement of Policies

for School Desegregation Plans Under Title .V I of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964. 45 CFR §181.54 .......40-41

Rep. U. S. Comm, on Civil Rights, Survey of Deseg

regation in the Southern and Border States,

1965-66 ........................................................................... 17,40

Rule 52a, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ............... 23

Initeii States (Umtrt nf Appeals

F ob th e F ourth C ircuit

No. 11,794

Civil Action No. C 1796

H arold D ouglas Coppedge, a m inor, et al.,

U nited S tates oe A merica, by R am sey C lark ,

Attorney General,

Appellees,

T he F ran k lin County B oard op E ducation , et al.,

Appellants.

APPE A L PROM T H E DISTRICT COURT OF T H E U N ITED STATES

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OP N O R TH CAROLINA

RALEIGH D IV ISIO N -C IV IL

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES,

PL AINTIFF-INTER YEN OR APPELLEE

Introductory Statement

Defendants, the Board of Education of Franklin County,

North Carolina and its members, appeal from a decision

of the Honorable Algernon Butler, United States District

Judge for the Eastern District of North Carolina,1 hold

ing that they had made insufficient progress in Franklin

County towards the disestablishment of a dual school sys

tem based on race, and directing them to take various

affirmative steps to assure equal educational opportunities

to all of the students in the District. The relief ordered

by the District Court included the requirement that the

1 The decision below is reported at 273 F. Supp. 282 (E.D. N.C. 1967).

2

defendants adopt and implement a plan for desegrega

tion other than so-called “ freedom of choice,” which the

Court described as illusory and a misnomer under the

existing circumstances. The thrust of defendants’ argu

ment on appeal is that the evidence is said to be insuffi

cient to sustain those of the District Court’s findings which

led that Court to hold that extensive intimidation and

community hostility to desegregation have made so-called

freedom of choice, in Franklin County, a misnomer and a

constitutionally inadequate means to achieve desegrega

tion. We disagree. We think that the District Court dis

played considerable patience for nearly two years with

defendants’ inadequate progress towards desegregation

and with a completely illusory “freedom of choice,” and

took great pains to try to make this plan work. After its

efforts failed, the District Court had no constitutional

alternative to the action which it took.

While defendants dispute the sufficiency of the evidence

to support the Court’s findings, much of the proof in the

case is uncontested. Apart from the question of intimida

tion, the entire structure of the school system has been

and is such as to keep the schools almost completely

segregated:

(1) The location of schools and grades is such that there

are pairs of schools covering grades 1-12 in four separate

areas of the county, one white2 and one Negro. Each

Negro school is within a mile or so of a white school

offering the same grades. Several of the schools have so

few students in the high school grades that their opera

tion as separate high schools is educationally indefensible.

2 For purposes of convenience, we will refer to all-white and predomi

nantly white schools simply as “white” schools, and the schools heretofore

maintained for Negroes as “Negro” schools. We recognize that, techni

cally, these schools are all “ free choice” schools, but the statistics in the

County justify our terminology.

3

In general, the system of side-by-side schools offering the

same grades is extravagant and unsound, offers no educa

tional advantage whatever, and is explicable only in racial

terms. (See pp. 6-9, infra.)

(2) In spite of the entry of the Interim Order in July,

1966, requiring non-racial assignment of new faculty mem

bers and the encouragement of faculty and staff members

already employed to cross racial lines,3 the defendants

made only minimal progress in faculty desegregation.

Staff and faculty desegregation for 1966-67 involved five

individuals of a total faculty of more than 200. The only

actual classroom teacher desegregation achieved during

that year consisted of a white lady who taught English at

an all-Negro high school for five hours per week. Nine of

the twelve schools in the system were totally unaffected by

faculty desegregation, and every school in the district re

mained—and remains today—racially identifiable by the

composition of its faculty. (See pp. 9-13, infra.)

(3) Substantial educational disparities exist between pre

dominantly white and Negro schools in Franklin County.

The summary of the evidence of disparities set forth in

the District Court’s Findings of Fact (D. App. 27A-28A),

which is based on defendants’ records and which they

cannot and do not contest, shows among other things that

the buildings and equipment in predominantly white schools

had, at the time this suit was brought, a per pupil valua

tion more than three times as great as the buildings and

equipment in the Negro schools. Negro schools have been

3 See Coppedge v. Franlclin County Board of Education, 12 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 230 (E.D. N.C. 1966), (D. App. 7-A-14-A). References to De

fendants’ Appendix are indicated herein by D. App. and page numbers.

References to Appellees’ Appendix are indicated herein by the page

number followed by the letter “a.”

4

seriously overcrowded, in terms of pupils per classroom,

pupils per teacher and acreage of site, and Negro pupils

residing near underutilized white schools have been bused

fourteen miles, each way, on a daily basis to overcrowded

Negro schools. Additions to the schools have also been

made in a manner tending to perpetuate segregation. (See

pp. 13-17, infra.)

(4) The transportation system which has been utilized

in Franklin County is unreasonable and uneconomical and

can be explained only in racial terms. While formerly white

and Negro schools in this rural county are located prac

tically side by side, their bus routes are separate and over

lapping, with the effect that two buses do on a racially

separate basis what one could do if race were ignored.

When bus routes of different schools have been combined,

this has always been done on a racial basis, so that, e.g.

one Negro elementary school shares a bus route with

another Negro school 14 miles away rather than with a

white school half a mile away. (See pp. 17-23, infra.)

It is our basic contention in this case that all of these

policies and practices are rooted in the dual system, are

educationally and administratively unsound, and serve

as devices to keep Negro students separate from white

students, to preserve all-Negro schools, and to induce

Negro students to attend them. In Franklin County, the

annual median Negro family income is $1,281, about

one-third of the white. When the policies of the school

board, in such a county, are directed to the one controlling

end of preserving the racial identities of schools, there

is little doubt that, even apart from overt intimidation,

comparatively little desegregation will result. In this case,

adherence by the defendants to these dual system policies

5

has been accompanied by extensive community hostility to

desegregation, characterized by bombings, shootings into

homes, pollution of wells, tacks in driveways, threats,

harassing telephone calls, economic coercion, and other

measures, all in a county where the Ku Klux Klan is

widely known to be powerful. No Negro has been able to

elect to attend a formerly white school with any confidence

that he would not suffer serious reprisals.

We believe that it has been and is inevitable under these

circumstances, that actual desegregation under the “ free

choice” system would be minimal, and so it has been.

During the fourth freedom of choice period conducted in

Franklin County in the spring of 1967, 45 of more than

3,100 Negro students chose desegregated schools, four

fewer than in the previous year. All of the white students

again elected to attend white schools. Had the District

Court not intervened, 1.5% of the Negro students would

have attended desegregated schools in 1967-68, while the

remaining 98.5% of the Negro students and 100% of the

white students would have attended schools still more or

less maintained for their color.4

We believe that the testimony and exhibits in this case

demonstrate why “freedom of choice” had to fail, and that

the statistical evidence shows the degree to which it has

failed. Since the Constitution requires that the dual sys

tem based on race be disestablished, the District Judge

ordered the defendants to put an end to their educationally

unsound and race-directed practices and to adopt a system

which makes educational sense and will desegregate the

schools as well. We submit that he could hardly have

ordered less.

4 In North Carolina, as a whole, in 1966-67, 15.4% of the Negro students

attended desegregated schools. In Mississippi, the corresponding figure

was 2.5% (D-App. 24A-25A.)

6

Proceedings Below

The history of the action is fully described in the Opinion

and Order of the Court below (D. App. 15A-17A).6 Since

Notice of Appeal was filed, a group of Negro parents

opposed to the District Court’s decree have moved this

Court for leave to intervene in the action. The facts sur

rounding this motion, which we oppose as an untimely

attempt to relitigate what the District Court has already

decided, are discussed in our Response thereto, filed De

cember 7, 1967.

THE EVIDENCE

I.

Defendants’ Adherence to Policies and Practices

Which Perpetuate a Dual System Based on Race.

A. School Organization and Utilization.

A study of the Franklin County school system was made

for this case by William L. Stormer, Assistant Chief of

the School Construction Section of the Division of School

Assistance, United States Office of Education. Mr. Stormer

testified in the action (1036a et seq.) and compiled a writ

ten report which is attached to his deposition (1551a et

seq.). Despite ample opportunity to do so, defendants de

clined to cross-examine Mr. Stormer on deposition or at the

trial and, for the most part, his testimony is uncontradicted.

Mr. Stormer testified, and the evidence shows, that the

schools in four areas of Franklin County (Louisburg, Bunn,

Youngsville and Gold Sand) are organized in groups and

clusters of two or three, one traditionally white and one 5

5 See 273 F. Supp. 289, 292-293 (E.D. N.C. 1967).

7

or more Negro (1040a-1041a). Every Negro school is with

in a mile or so of a predominantly white school covering

the same grades (1041a). In two other parts of the county

—Epsom and the general area of Edward Best High School

and Edward Best Elementary School—there are white

schools but no Negro schools (1041a, 1415a-1416a). Several

of the high schools in the county are very small (Epsom,

a white school, had 72 children in grades 9-12 last year),

and only one or two are large enough to mate diversified

educational opportunities available to students at a reason

able cost per pupil (217a, 1043a).

Mr. Stormer was asked whether a system in which pairs

of schools offering the same grades were located in the

same area presented any educational disadvantages, and

he listed several:

(a) A more diversified program may be offered in a

large school than in a small one, particularly in

the high school grades (1042a). For example,

Bunn (white) and Gethsemane (Negro) schools

are located within about a mile of one another.

Bunn had 229 students in grades 9-12; Geth

semane 157 students in these grades (217a). Bunn

offers the following courses which Gethsemane

does not: Geography, Advanced Trigonometry

and Algebra, Agriculture, Consumer Math, Short

hand, Spanish I and II, Physical Education and

Health II, and Chemistry. Gethsemane offers the

following courses which Bunn does not: Con

struction industry, Business Communication, and

Special Education (218a, 1044a). If the high

school grades of these schools were consolidated,

each high school student now in either school

would be able to take any of the above courses

(1045a).

8

(b) There is a substantially higher cost per pupil in

attempting to provide a diversified program to a

small school than a large one. In Mr. Stormer’s

words, “ the smaller the school, the higher the

cost per pupil for the educational program being

offered . . . Because of small total membership,

you are not able to maintain classes in certain

subject areas because . . . it becomes uneconomi

cal to offer one class for five or six or seven pupils”

(1043a).

(c) In general, it is possible to secure better utiliza

tion out of the school facilities if the plants of

two small schools are combined than if the same

grades continue to be offered in each school

(1042a).

When asked if there were any educational advantages to

this system of pairs of schools, he said he knew of none,

and that the only explanation for its existence was racial

segregation (1068a, 1095a).

The situation closely resembles that discussed by the

Court in Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267

F. Supp. 458, 472 (M.D. Ala., 1967) (three judge court),

the statewide school desegregation suit in Alabama, in the

following passage:

. . . Considerations of economy, convenience, and edu

cation have been subordinated to the policy of racial

separation; survey approvals of construction sites re

flect this policy. A striking instance of this discrim

inatory conduct is found in the Clarke County survey

conducted during the 1964-65 school year. At the time

of the survey, there were twenty-three schools in the

system attended by approximately 5800 students—

2400 white and 3400 Negro. Consolidation was clearly

9

called for; yet the survey staff sought to perpetuate

the segregated system by recommending and approv

ing that, in each of the three principal towns of the

county, two separate schools be maintained as perma

nent school installations, each covering grades 1-12.

This recommendation in each of these three towns in

Clarke County, Alabama, can be explained only in

racial terms . . .

See also Moses v. Washington Parish, La. School Board,

------ F. Supp.------- (No. 15973, E.D. La., October 19, 1967);

Cf. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865, 871 (5th Cir. 1966); Kelley v. Altheimer,

Ark School Dist., 378 F.2d 483, 486 (8th Cir. 1967).

Mr. Stormer testified that consolidation of side-by-side

schools, with the facilities of each used for some grades,

was feasible and educationally advantageous, and -would

automatically desegregate the schools (1078a-1079a, 1042a

et seq.; 1556a). He also explained the administrative con

venience of geographical zoning, which would likewise

eliminate the dual system (1074a-1079a). The District

Court’s order requires the defendants to adopt one or both

of these methods to desegregate the schools.

B. Assignment of Staff and Faculty.

Prior to the commencement of the 1966-67 school year,

all white teachers in the Franklin County system taught

at white schools, and all-Negro teachers taught at Negro

schools (D. App. 6A). On July 27, 1966, the District Court

entered an Interim Order which included a faculty provi

sion based on Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Educa

tion, 363 F.2d 738 (4th Cir. 1966). The defendants were

ordered to fill all faculty and professional staff vacancies

on a nonracial basis and to encourage transfers across

10

racial lines by present members of the faculty. The de

fendants were also required to file Objective Standards

for Employment, Assignment and Retention of Teachers6

(D. App. 8A-10A).

The District Court found, on the basis of ample evi

dence, that the defendants had failed, under the Interim

Order, to take adequate affirmative steps to accomplish

substantial staff and faculty desegregation. This failure

did not result from inadequate opportunity. Of a total

1966-67 faculty of 232 (112 white, 120 Negro), 49 (25 white,

24 Negro) were newly employed that year, and could have

been assigned to any school in the system (215a). Nor

was there a scarcity of teachers already employed who

were prepared to transfer. Five such teachers testified on

deposition, three for defendants and two for plaintiff-

intervenor, and all of them stated that they would have

been willing to cross racial lines but had not been asked

by the defendants to do so (999a-1000a; 1018a-1020a; 1216a;

1222a-1223a; 1226a-1229a). Nevertheless, nine of the twelve

schools in the system remained totally segregated with

respect to faculty (1408a-1409a). In the remaining three,

Negro librarians were assigned to each of two white

schools7 and a white librarian and white English teacher

(who taught for five hours a week) were assigned to an

all-Negro school. Except for these assignments, the only

6 A provision of these Standards, which provided that teachers would

be assigned, if possible, to the school of their choice, and which sought

to delegate to them the Board’s duty to desegregate the faculty, was

properly disapproved by the District Court as tending to perpetuate

segregation, Kier v. County School Bd. of Augusta Cty, Va., 249 F. Supp.

239, 248 (W.D. Va. 1966).

7 One of these Negro librarians at a white school became sick and the

defendants replaced her during the course of the year and was replaced

by a white woman. (1409a) This totally resegregated the faculty of a

tenth school.

11

“encouragement” given by the defendants to teachers to

cross racial lines was to notify them, orally and in writing,

that they might apply to cross racial lines (1228a-1229a).

Defendants contend (Brief, p. 40) that they could not

desegregate more during 1966-67 because only five or six

vacancies remained at the time of the Interim Order of

July 27, 1966, Even assuming that defendants had the

right to ignore Supreme Court decisions requiring deseg

regation generally, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954), and in faculty assignments in particular, Brad

ley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) and Rogers v.

Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965), until they were personally sued

and enjoined—and we cannot assent to such a proposition

-—this “inadequate time” explanation is annihilated by

what took place thereafter. Superintendent Smith testified

at the trial, on July 26, 1967, that only five teachers had

been hired to cross racial lines for 1967-68, an increase of

one over the previous year. These five included one Negro

who had testified on behalf of plaintiff-intervenor that

she would be willing to transfer and one whose husband

testified that he believed she would be willing to do so.

Apart from these two teachers, who were in effect found

for defendants by the Government, there would actually

have been a decrease in faculty desegregation for 1967-68

(1467a-1468a).

Two principal consequences flow from the defendants’

failure to accomplish significant faculty desegregation un

der the District Court’s Interim Order of July 27, 1966.

The first is that a more specific and a more comprehen

sive decree directing substantial faculty desegregation is

now required. Bowman v. County School Board of Charles

City County, Va., 382 F.2d 326, 329 (4th Cir. 1967).

Judge Butler’s order, which requires affirmative encour

12

agement of teachers to cross racial lines, the assignment

of at least two minority race teachers to each school in

the district for 1967-68, and substantial progress there

after, is a temperate but firm reflection of what the courts

have been requiring under similar circumstances. Dowell

v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971

(W.D. Okla. 1965), aff’d. 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967),

cert. den. 387 U.S. 931 (1967); Kelley v. Altheimer, Ark.

School Dist., 378 F.2d 483, 498 (8th Cir. 1967); United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 380 F.2d

385, 394 (5th Cir. 1967) (en banc), aff’g. 372 F.2d 836 (5th

Cir. 1966); Kier v. County School Board, 249 F. Supp.

239, 247 (W.D. Va. 1966). The second consequence of the

defendants’ failure to make progress on faculty desegre

gation is its bearing on the appropriateness of the “ free

choice” method of desegregation. As Judge Butzner said

in Thompson v. County School Board of Hanover County,

252 F. Supp. 546, 551 (E.D. Ya. 1966), quoting from Kier,

supra:

Freedom of choice, in other words, does not mean a

choice between a clearly delineated ‘Negro school’

(having an all-Negro faculty and staff) and a ‘white

school’ (with all-white faculty and staff). School au

thorities who have heretofore operated dual school

systems for Negroes and whites must assume the duty

of eliminating the effects of dualism before a free

dom of choice plan can be superimposed upon the

preexisting situation and approved as a final plan of

desegregation. It is not enough to open the previously

all-white schools to Negro students who desire to go

there while all-Negro schools continue to be main

tained as such. Inevitably, Negro children will be en

couraged to remain in ‘their school,’ built for Negroes

and maintained for Negroes with all-Negro teachers

13

and administrative personnel . . . This encouragement

may be subtle but it is nonetheless discriminatory. The

duty rests with the School Board to overcome the

discrimination of the past, and the long-established

image of the ‘Negro school’ can be overcome under

freedom of choice only by the presence of an integrated

faculty.

See also Judge Wisdom’s majority opinion in Jefferson,

supra, 372 F.2d at 890, wherein it was said

Freedom of choice means the maximum amount of

freedom and clearly understood choice in a bona fide

unitary system where schools are not white schools

or Negro schools—just schools.

C. Disparities.

Segregated schools are inherently unequal. Even if there

were no tangible disparities in Franklin County, the all-

Negro schools would still be inferior to the all-white schools.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). In

this case, however, the evidence—largely the defendants’

own reports to the State Department of Education—show

that reliance on presumptions and psychological damage is

unnecessary. As the District Court found (D. App. 27A-

28A), the disparities—tangible, physical, bread and butter

disparities—have been imposing.

At the time this action was started,8 all white children

and a few Negroes were attending schools at which the

school buildings and equipment were worth $913.44 per

pupil. At the Negro schools, the corresponding figure was

8 The details of the disparities are set forth in our motion to eliminate

them, which, in turn, was computed from materials filed by the defen

dants with the State Board of Education and introduced into evidence

in this case. (185a-203a) See also Mr. Stormer’s Report (1551a-1566a).

14

$285.18 per pupil. Two small Negro schools, Youngsville

Elementary and Cedar Street, were worth $93.77 and

$133.49 per pupil respectively.

At the predominantly white schools, there was a class

room for every 22.8 students. At the Negro schools, the

corresponding figure was 34.9.

Predominantly white schools had 24.9 pupils for every

acre of site. Negro schools had 94.7 pupils per every acre

of site. Riverside High School (Negro), with twice as

many students as predominantly white Louisburg High

School, has one-quarter of the acreage.

White children had nine library volumes per pupil.

Negro children had four. There was a white teacher for

every 25 white children enrolled, and there was a Negro

teacher for every 35 Negro children enrolled. Since segre

gation was the practice in North Carolina at the time these

teachers were trained, the Negro teachers had, for the

most part, attended segregated, inferior Negro schools.

All the predominantly white elementary schools are ac

credited by the State. No Negro elementary school has

accreditation. The predominantly white high schools have

all been accredited since the 1920’s. The three Negro high

schools were accredited in 1933, 1960, and 1961 respectively.

Two of the Negro schools—Youngsville Elementary and

Cedar Street—are, so Mr. Stonner testified, simply in

adequate (1061a-1062a). Cedar Street has four teachers

for seven grades (1058a). Children eat lunch in the class

room, and this lunch is shipped in by truck from all-Negro

Riverside, past predominantly white Louisburg (1434a).

The situation at Youngsville Elementary is similarly poor

(1058a, 1098a).

15

The problems are many, but the most acute is over

crowding. During 1966-67, the Franklin County Board of

Education was receiving federal assistance under the

Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1422a). There

are mobile classrooms—nicknamed “portables”—all over

the already overcrowded Negro school sites, and there is

other federal equipment (1050a-1053a, 1423a-1425a). This

federal assistance has increased the value of buildings and

equipment per pupil at the Negro schools, and has re

duced to some limited extent the number of pupils per

classroom at Negro schools (D. App. 28A).

However, even after the addition of portable classrooms,

ail of the Negro schools except Cedar Street remain over

crowded, and Cedar Street would be without its portable

(1063a). White Epsom High, on the other hand, with 72

students in grades 9 through 12, all white, is at 39.5%

of reasonable capacity (1560a). To run a high school of

that size is so expensive that teacher salaries are $350.30

per pupil in the class, compared with $188 at Bunn, $231.09

at Perry’s and $235.91 at Riverside (1566a). Neverthe

less, the Negro students living in Epsom are carried 13

miles to Riverside High School, at which students number

126.4% of capacity even with the portable. Similarly,

Negro students living near under-utilized white Youngs-

ville High travel 14 miles to Riverside, and those in the

vicinity of under-utilized and white Edward Best High

ride a similar distance to overcrowded all-Negro Perry’s

(1415a-1417a).

During 1966-67, using 25 pupils as the capacity per class

room, the Negro schools were overcrowded by a total of

392 pupils, whereas five of the predominantly white schools

—Edward Best Elementary, Edward Best High, Epsom,

Gold Sand and Louisburg High—were under-utilized by a

16

total of 492 places.9 Even if choice in Franklin County had

really been free, the defendants would still have been under

the obligation to assure approximately equal pupil-class

room ratios.10 Quite apart from the effect of intimidation

on the amount of desegregation in Frankin County, Judge

Butler’s Order directing defendants to transfer a sufficien t

number of Negro pupils to white schools for 1967-68 to

assure that a total of at least 10% attend desegregated

schools, was an appropriate response to the overcrowding

problem alone.

The existence of these uncontested disparities required

the District Court to include in its Order a strong equali

zation provision, and the Court did so (D. App. 35A-36A).

The significance of so extreme a denial of equal educa

tional opportunities, however, goes beyond that portion of

the decree, and affects the principal issue of the constitu

tional adequacy in Franklin County of desegregation under

“free choice.” In Franklin County, private sources make

major contributions to the schools, and, since white people

in the county are generally much wealthier than Negroes,

the white schools reecive most of the benefit (1400a-1401a).

Since, under freedom of choice plans, schools tend to

retain their racial identities, and formerly Negro schools

remain all-Negro for lack of white pupils electing to at

9 These statistics include the portable classrooms provided by the Fed

eral Government and located at overcrowded Negro school sites (1423a-

1425a). The only possible justification for further overcrowding the

Negro sites by locating the portables there is racial. I f the portables had

been placed where there was room for them, it would have been even

more imperative to transfer Negro pupils to white schools. The author

ities require, as did the District Court here, that any substantial additions

to existing schools be made with the “ objective of eradicating the ves

tiges of the dual system.” Jefferson, supra, 380 F. 2d at 394, Kelley,

supra, 378 F. 2d at 499.

10 See the Fifth Circuit’s Model Decree in Jefferson, 380 F. 2d at 393-

394; Kelley v. Altheimer, supra, 378 F. 2d at 499.

17

tend them,11 contributions, under such a system, are likely

to continue to go to predominantly white schools, and the

existence of inferior and sub-standard schools readily

identifiable as Negro institutions will tend to continue.

Consequently, as Judge Wisdom observed in Jefferson,

supra,

A freedom of choice plan will be ineffective if the

students cannot choose among schools that are sub

stantially equal. 372 F.2d at 891.

D. Transportation.

In Kelley v. Altheimer, Ark. School District, supra, 378

F.2d at 497, the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

said:

The Board of Education transports rural students

to and from their homes precisely as it did during

the many years it operated a segregated school sys

tem. It was inefficient and costly then. It is just as

inefficient and costly now. Running two school buses

down the same country road, one to pick up and de

liver Martin students and the other to pick up and

deliver next door neighbors attending Altheimer, is

a luxury that this impoverished school board could

not afford in the past and cannot afford now. The

difference is that, before Brown the Board had the

same right to operate segregated school buses as it

had to operate segregated schools. While we have no

authority to strike down transportation systems be

cause they are costly and inefficient, we must strike

them down if their operation serves to discourage the

desegregation of the school system.

11 United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, supra, 372

F. 2d at 889; Rep. U. S. Comm, on Civil Rights, Survey of Desegregation

in the Southern and Border States, 1965-66, p. 33.

18

The organization of the Franklin County district pur

suant to a system of side-by-side schools makes the cited

language of the Kelley case particularly applicable to the

facts at bar. In the rural areas of Franklin County, whites

and Negroes live side-by-side (1418a). Since the white and

Negro schools are also located, for practical purposes, side

by side, and since, except as indicated below, each school

has its own bus routes, substantial overlapping results

(1418a).

The feasibility and desirability of consolidating bus

routes—a step which would end unnecessary duplication—

has been recognized by the defendants by their conduct.

Since Franklin County employs high school students as

drivers, it has been necessary to provide pupils from other

schools to drive school buses, for three elementary schools

—Edward Best Elementary (white) and Cedar Street and

Youngsville Elementary (Negro). Accordingly, the bus

routes of each of these schools have been combined with

those of schools which offer high school grades. It is

in this context that the dual system orientation of the

defendants is most clearly exposed; the Negro elementary

schools have common bus routes with other Negro schools,

and the white elementary school has a common route with

white Edward Best High. The most extreme example has

been the consolidation of the routes of all-Negro Youngs

ville Elementary with those of all-Negro Riverside, four

teen miles away, rather than with all-white Youngsville

High School, half a mile away (1418a). Similarly, all-

Negro Cedar Street was combined with Riverside rather

than with predominantly white Louisburg (which is lo

cated between the two), not only for transportation of

pupils (1418a-1422a), but also with regard to the lunch

program; lunch is trucked in from Riverside past Louis

burg to Cedar Street (1434a).

19

Defendants’ transportation policy carries with it all of

the usual incidents of racial discrimination. Not only do

the Negroes attending Negro schools—98.5% of all the

Negroes—ride separate buses, but their transportation is

inferior. When suit was brought, the average load on buses

at Negro schools was 64.1, for buses at white schools 43

(D. App. 27A).12 13 Negro bus routes are longer in mileage

and time spent than those of white schools; e.g., the longest

bus route for Negro Youngsville Elementary takes 120

minutes each way, the longest for white Youngsville High

fifty-five. At all-Negro Riverside, fourteen of sixteen buses

make more than one trip per day; at predominantly white

Louisburg, none (Government’s Trial Exhibits 24 and 32:

not reproduced in appendix). Consequently, we believe

that Franklin County is a prime example of the principle,

restated by the Court in Kelley, supra, that

the school bus is a principal factor in perpetuating

school segregation in many areas of the South. 378

F.2d at 497.

Conversion to a system of nonracial geographic attendance

zones, or to school or grade consolidation, as directed by

the District Court, will, of course, not only eliminate the

irrationality and wastefulness of the present transporta

tion system, but provide meaningful opportunities for a

desegregated education as wTell.18

12 A year later the figures were 54.7 to 40.2 (D. App. 28A).

13 In Corbin and United States v. County School Board of Loudoun

County, Va., ------ F. Supp. ------ , C.A. No. 2737 (E.D. Ya. August 29,

1967), United States District Judge Oren R. Lewis ordered, among other

things, that

As soon as practicable during the 1967-68 school year, and consistent

with economy and efficiency, all transportation of pupils shall be

desegregated and, to that end, the defendants shall forthwith dis

continue the practice of limiting any particular bus route to any

particular school whenever such limitation results in unreasonable

overlapping between the routes of buses serving traditionally white

schools and those serving traditionally Negro schools.

20

In two recent decisions, District Courts in Virginia and

Louisiana have ordered the abandonment of the “ free

choice” system of desegregation even without proof of

intimidation. In Corbin and United States v. County School

Board of Loudoun County, Va., —— F. Supp. ------ , C.A.

No. 2737 (F..D. Va. August 29, 1987), the proof showed

that in Loudoun County, Negroes, who comprised about

15% of the student population, were scattered throughout

the county and, under a somewhat informal “ free choice”

system, rode long distances past predominantly white

schools to all-Negro schools. The Superintendent admitted

that most of the Negro pupils could be accommodated at

predominantly white schools close to their homes. There

was gross duplication in white and Negro bus routes.

Progress towards disestablishing dual school zones had

been halting. Judge Oren E. Lewis, accepting the Govern

ment’s argument that there was no rational non-racial

basis for continued adherence to any system, including

“free choice,” which would preserve the existence of all-

Negro schools, entered an Order which included the follow

ing provisions:

Effective for the 1967-68 school year, the defendants

shall assign all Negro elementary school students in

the system who reside outside the town limits of Lees

burg to the schools nearest their homes having the

capacity to accommodate them.

• # # # #

No later than the commencement of the 1968-69 school

year, the Loudoun County Elementary Schools shall

be operated on the basis of a system of compact, uni

tary, non-racial geographic attendance zones in which

there shall be no schools staffed or attended solely by

Negroes. Upon the completion of the new Broad Eun

21

High. School, the high schools shall be operated on a

like basis.

In Moses v. Washington Parish, La. School Board,------

F. Supp, ------ , CA No. 15973 (E.D. La. October 19, 1967),

the Court, noting the existence of some of the educational

and administrative disadvantages of the “free choice” sys

tem which are proved by the record here, ordered “the

abandonment of the so-called ‘free choice’ method of pupil

assignment for the Washington Parish school system and,

in its place, the institution of a geographical zoning plan.”

Judge Heebe traced the origins of the free choice system

and expressed the view that it was a logical interim

measure:

In the process of grade by grade desegregation, it is

not difficult to imagine the hardships inherent and

indeed the practical impossibility of requiring shifting

geographical zones for desegregated grades, while al

lowing maintenance of the segregated assignments for

grades not yet reached by the desegregation proc

ess. . . .

But the usefulness of such plans logically ended with

the end of the desegregation process. With all grades

desegregated, there is no apparent reason for the

continued use of the purely interim and temporary

free choice system.

Expounding at some length on the educational shortcom

ings of “ free choice,” including its disruption of the “first

principle of pupil assignment . . . [which] ought to be

to utilize all available classrooms and schools to accommo

date the most favorable number of students,” and on its

inherent uncertainties, as a result of which “the board

cannot make plans for the transportation of students to

22

schools,14 plan curricula, or even plan such things as lunch

allotments and schedules,” the Court found that the School

Board was adhering to “ free choice” not because of real

concern about the pupil’s volition, which had been deemed

irrelevant prior to desegregation, but rather for the pur

pose of “ shifting to both white and Negro students the

hoard’s own burden to run honestly and actually desegre

gated truly non-racial systems.” The Court concluded that

since “the implementation of the absurd system of free

choice on a permanent basis has followed closely on the

heels of the imperative to desegregate,” and since the

School Board had not shown any valid non-racial purpose

for continuing to this system, the “ free choice” plan would

be disapproved and geographic zoning ordered.

The holdings in the Corbin and Moses cases, and the

remarks of appellate courts in others,15 16 suggest that it is

at least arguable that the uncontested facts of this case,

even absent any intimidation, would make Franklin

County’s “ free choice” plan constitutionally inadequate.

We think these dual system facts important because they

illustrate the extent to which conversion to a unitary sys

tem will eliminate the administrative and educational as

well as racial burdens which Franklin County has had to

bear for so long. This Court need not decide here, how

ever, whether the Board’s “dual system” policies and prac

tices would invalidate free choice in a free and uninhib

ited atmosphere, for in Franklin County there has been

no such atmosphere. In this County, racial intimidation

has been such that “ freedom of choice” has been, in the

14 See in this connection the testimony of Thaddeus Jerome Cheek

(627a, 632a).

16 Jefferson, supra, 372 F. 2d at 889; Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14,

21 (8th Cir. 1965); Singleton v. Jackson Municip. Separate School Dist.,

355 F. 2d 865, 871 (5th Cir. 1966).

23

District Court’s words, both an illusion and a misnomer,

and the choice has not been free in the practical context

of its exercise. Bowman v. County School Board of

Charles City County, 382 F.2d 326, 327-328 (4th Cir. 1967).

n.

Pressures Inhibiting the Exercise of Free Choice.

The District Court’s decision holding unconstitutional

Franklin County’s “ free choice” plan was principally

grounded on the existence of community hostility to de

segregation and on numerous acts of violence and intimi

dation directed against Negroes seeking a desegregated

education for themselves or for their children. While

there are suggestions in defendants’ brief that the District

Court erred on the law, and that the “free choice” plan

should be allowed to stand even if choice was effectively

inhibited by intimidatory acts of third parties,16 the thrust

of their argument appears to be that the evidence was

insufficient to support Judge Butler’s findings of commu

nity hostility and intimidation.16 17 We submit that this con

tention is completely without substance. While, under Rule

52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the Court

of Appeals will sustain the District Court’s factual de

terminations, unless they are “clearly erroneous,” and will

16 See Defendants’ brief, pp. 33-34, 37.

17 Defendants also (brief, pp. 11-13) attack the sufficiency of Judge

Butler’s finding that the defendants failed, in 1965, to give parents in

still segregated grades notice of criteria for transfer to desegregated

schools. They claim that this finding is at odds with the Court’s earlier

Order of February 24, 1966. Actually, the two orders are perfectly con

sistent; compare Conclusion No. 6 of the 1966 order (D. App. 4A)

with pertinent language in the 1967 Order (D. App. 15A-16A, 19A).

Moreover, Rev. Latham, who discussed desegregation both with the

Board and with Negro leaders as a kind of informal emissary, tes

tified, after the date of the earlier order, that the criteria were not

determined until after the Negroes had applied (492a, 498a).

24

not disturb the trial court’s findings merely because it may

doubt their correctness, Darter v. Greenville Hotel Corp.,

301 F.2d 70, 72-73 (4th Cir. 1962), questions about the

scope of review appear almost academic in this case. The

intimidation proved in this record is uncontradicted, and

its volume is probably unparallelled in the history of

school desegregation litigation.18 Its effects are apparent

from the 1.5% pupil desegregation achieved on the fourth

try in Franklin County—less than one tenth of the North

Carolina average.

A. Community Attitudes.

At pages 13-14 of their brief, defendants attack as un

supported by the evidence the District Court’s finding that

there is “ marked hostility to school desegregation in Frank

lin County.” We submit that they know better. On Octo

ber 20, 1964, Mr. Clinton Fuller, one of the defendants

in this action, who wears two hats as Vice President of the

School Board and editor of the county newspaper, wrote

in a rather sympathetic Franklin Times editorial about a

large Klan rally that

The Klan has been strong in this county for many

years. By the nature of the organization, this has

been kept secret. It will undoubtedly gain strength

now following the rally (1571a).19

The Board of Education minutes of April 12, 1965, reflect

the filing of a petition with the Board, signed by 767

persons, stating that

18 A partial chronology of intimidatory incidents or events, as presented

to the trial court, is set forth at pp. 238a, et seq. of our Appendix.

19 For an illuminating discussion o f what the presence of a strong

Klan means to Negroes seeking to exercise civil rights, see United States

v. Original Knights of Ku Klux Klan, 250 F. Supp. 330 (E.D. La. 1965)

(three-judge court).

25

We, the undersigned people of Franklin County, do

hereby express our preference to forfeit Federal Aid

to the schools of said county rather than to support

integration. We suggest this be put to a vote by the

people to maintain and operate our school system by

a tax on each and every adult taxpayer (1539a).

On August 5, 1965, Mr. Fuller remarked, in a Franklin

Times editorial about school desegregation headlined

“Frustration Is The Word” , that

Most local citizens oppose integration of the schools.

We do ourselves. We don’t believe it will work (1581a).

In September of 1966, a citizens’ petition signed by 584

persons, together with other pressures, prompted the re

versal of the decision by the school board of the admin

istratively separate Franklinton unit in Franklin County

of an initial decision to agree to requests by the U. S. Office

of Education for further desegregation (854a, 1606a); the

Franklin Times of September 8, 1966 headlined the occa

sion “FRANKLINTON BOARD VOTES NO” (1602a). On

December 1, 1966, Mr. Fuller’s headline read: “FRANK

LINTON BUS USE LIFTED FOLLOWING K KK

THREAT” (1610a). Finally, on November 22, 1967, Ne

gro applicants for intervention who seek to return to all-

Negro schools, and on whose intervention defendants claim

to rely (brief, pp. 29, 35), alleged in their motion “ that

they are being forced to go to schools where they have

no friends; and that they are nervous and upset”—a posi

tion which can hardly be reconciled with the supposed

non-existence of community hostility.

Even without actual violence, this strong and highly

publicized community feeling would make freedom of

choice less than free in fact. Negroes in the county are

26

in general much poorer than white persons and are eco

nomically dependent on them,20 and poverty and depend

ence restrict the range of choice. Cf. Vick v. County School

Board of Obion County, Tenn., 205 F. Supp. 436, 440 (W.D.

Tenn. 1962). In Franklin County, however, choice has

not been inhibited simply by community attitudes. The

underlying hostility has been implemented by pervasive

acts of violence and intimidation which have jeopardized

the safety and well-being of any Negro who might seek a

desegregated education.

B. Acts of Intimidation.

Since defendants attack the sufficiency of the evidence

to support the findings of intimidation, we have found it

necessary to print in our Appendix most of the proof we

have adduced with respect thereto, so that the Court may

judge for itself. We believe that the Chronology of In

timidation (238a et seq.) provides the Court with a useful

perspective as to the obstacles Negroes seeking a deseg

regated education have had to meet, and we will only

provide a brief outline here.

The evidence of intimidation in this record begins in

1963, with a bomb threat to Eev. Dunston, NAACP leader

20 The 1960 Census, extracts from which are in the record (259a et

seq.) shows the following data for Franklin County:

% of All

White % of All

Persons Nonwhites

Category in Category in Category

Family income over $3,000 per year ........... 58.3% 13.2%

Family income over $5,000 per year ........... 29.5% 2.7%

Family income over $7,000 per year ........... 12.1% 0.7%

Persons with income over $3,000 per year —. 27.8% 4.9%

Persons residing in owner occupied units .... 63% 29%

Median Income—Families ............................ $3,507 $1,281

Median Income—Persons ............................... $1,701 $595

27

who had presented a 130-name petition for desegregation

to the School Board (274a, 412a). In 1964 an unsuccessful

attempt was made by a group of Negroes to transfer to

desegregated schools; the parents involved were promptly

warned to stay off a white man’s land (421a; 451a). In

1964, considerable publicity was given to Klan activity,

including cross burnings, rallies, and the successful in

timidation of the Chairman of the annual Christmas parade

for not putting Negroes in the back of the procession

(363a-364a, 1567a-1573a). Accordingly, in the spring of

1965, when the defendants elected to desegregate by the

“ freedom of choice” method, they knew that the Klan was

active in the county and that some opponents of deseg

regation had violent tendencies, and they might well have

anticipated just how free “ free choice” would be.

On June 8, 1965, following the defendants’ adoption of

the “ freedom of choice” plan, the Franklin Times dis

closed the names and schools of the Negroes who applied

to attend previously all-white schools (D. App. 69A-71A).21

Following the release of these names, the intimidation be

came particularly intense. There were shootings into

homes (372a, 414a, 424a-428a, 1575a, 1596a); explosions at

Negro residences, (605a; 674a; 760a-761a; 888a-890a;

1587a); well poisonings and similar incidents (398a, 569a,

629a, 886a); the scattering of nails in driveways; (411a,

499a, 567a); threatening or obscene notes (596a, 667a, 628a,.

927a, 960a, 1109a); hundreds of threatening or abusive

telephone calls (277a, 329a, 429a, 487a; 499a; 564a-565a;

884a-885a; 1278a-1279a); cross burnings (310a, 499a, 535a,

21 On other occasions, Mr. Fuller also published the addresses of some

or all families involved in desegregation, or in incidents arising there

from (426a, 721a, 1568a, 1575a, 1582a, 1584a), and he told a fellow

board member who tried to restrain him from such publication to “ mind

his own business.” (495a-496a)

28

565a, 730a, 890a); and economic reprisals of various kinds

(282a; 335a-337a; 410a-411a; 566a-567a; 691a-693a; 742a

et seq.; 907a et seq.; 1591a et seq.).

The result was, as Judge Butler found, that while 76

of approximately 3,100 Negro pupils applied to attend

previously all-white schools, and 31 were accepted, all but

six -withdrew before the close of the 1965-66 school year

(D. App. 19A).22 Several of the Negro students who did

attend desegregated schools in 1965-66 were treated un

kindly by their fellow pupils; some received threatening

and abusive notes, and one was pushed around so much

in the first few days that he dropped out of school (628a,

926a, 1589a). The same period also witnessed Klan-type

harassment of Superintendent Rogers of the Franklinton

schools, who was trying to comply with federal desegre

gation requirements, and of two white ministers, Robert

Latham and Frank Wood, who were openly trying to im

prove race relations (499a-500a, 530a-536a, 730a-731a).

It was in July, 1966, immediately following the most

recent of these events, that this case was initially scheduled

for trial. Only 23 Negroes had elected to attend deseg

regated schools for 1966-67, and both plaintiffs and the

United States were ready to present the evidence of in

timidation which we have just described and to contend

that it had made “free choice” constitutionally inadequate

in Franklin County. After discussions between the District

22 Margaret Crudup, whose testimony defendants seek to minimize

(brief, pp. 23-24), wrote a letter withdrawing her application to a white

school after her parents received the following anonymous note:

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Crudup. We hear that you are sending a child

to Youngsville School. Well we are giving you 30 days to get out

of Franklin County. Pay your landlord what you owe him if any.

Leave your crop. We are not going to warne you agane. We will

start in your family and will start with you to killing. (667a; see

also 649a, 661a)

29

Court and counsel, however, trial on the merits was post

poned, and an Interim Order was entered in which defen

dants were required to conduct a new “ freedom of choice”

period for Negroes with such safeguards against intimi

dation as could reasonably be put in a decree of this type

(D. App. 8A-14A). Following the entry of the Order,

counsel for all parties met with representative community

groups to try to make free choice work (D. App. 24A-

25A), and the plaintiffs, the ministers interested in better

race relations, and others did their best to cooperate in

all ways with the District Court’s Order (742a-744a, 912a,

1265a). A new choice period ensued, and a total of 49

Negro pupils elected to attend desegregated schools (D.

App. 19A).

The hopes that the intimidation would cease and that

choice would become free in fact did not, however, ma

terialize. Immediately after the court-ordered free choice

period, shots were fired into a Negro home, and, while the

victim of this shooting did not have children in a desegre

gated school, the Franklin Times immediately associated

the incident with school desegregation and speculated as

to its effect on the Interim Order (1212a, 1596a). Soon

after school opened, shots were fired into the home of a

Negro whose two daughters had just enrolled for the first

time at a desegregated school (822a-823a).23 Negro pupils

23 One of the more bizarre of defendants’ contentions on appeal (brief,

pp. 19-20) is that the District Court should not have considered this

incident because the Government proved it through the testimony of one

of the teenaged students instead of through the father or mother. They

suggest that if the parents had testified this would have shown that some

nonracial reason lay behind the shooting. Actually, defendants did not

call any other family member although they certainly could have done

so, and there is not one shred of evidence in the record to support defen

dants’ speculations. The reason we called the daughter rather than the

father was that she could, and did, testify to other intimidatory and

related incidents at the desegregated school, which would have been hear

say from her parents (825a et seq.).

30

continued to receive unfriendly treatment from fellow stu

dents at white schools (791a-792a; 825a; 927a-928a; 960a-

961a). The racial troubles of the Franklinton system to

which we have referred earlier were front page news, and

every Negro in the County could read in the Franklin

Times and elsewhere that intensive community pressure

had forced the Franklinton Board to capitulate to persons

hostile to desegregation (1602a), and that Mr. Rogers’

home was under guard (1600a).24 25 Within a few months

of the opening of school, both of the white clergymen

whose concern for racial equity had led them to speak out

for their convictions and to testify for the United States

had been forced out of their pulpits, one formally by a

lop-sided vote of his congregation (749a), and one by the

accumulation of race-connected pressures which impeded

his ministry and threatened his family (911a).26 Super

intendent Rogers of Franklinton also resigned after he was

subjected to civil and criminal charges and described in

the Franklin Times as the center of controversy over in

tegration (1600a), so that by the date of the 1967 trial,

all of the Government’s white witnesses at the 1966 depo

sitions had lost their jobs or resigned under pressure.

24 In an editorial about the Franklinton situation entitled “ Pressure in

a Thicket,” the Raleigh News and Observer o f September 10, 1966, pre

dicted that “ the extraordinary citizen pressure generated against the

school board is going to be evidence as to why a ‘freedom of choice’ plan

of desegregation has not worked there. It is doubtful whether any court

would believe ‘freedom of choice’ is possible where such pressure has

been demonstrated.” (1606a-1607a)

25 While defendants, (brief, pp. 21-22) consider it “ extremely unjust

for any person to even guess at the real reason” why these ministers lost

their pulpits, we submit that a reading of their depositions (each testified

twice, once before and once after the loss of his pulpit; 483a et seq., 907a

et seq.; 526a et seq., 742a et seq.) and a consideration of their racial

activities, the harassment, and the sequence of events leaves no doubt as

to why they are no longer in Franklin County. Cf. Johnson v. Branch,

364 F. 2d 177, 182 (4th Cir. 1966).

31

In the spring of 1967, Franklin County held its “ free

choice” period for 1967-68—the fourth such period in two

years. The choice period coincided with an abrupt increase

in the level of harassment. In the first week in March,

an explosion took place outside the Coppedge home; this

incident is corroborated, despite defendant’s pleas to the

court to disregard it (Brief, pp. 20-21), not only by the

Government’s witnesses (1130a, D. App., 83A, 90A) but

also, except as to details, by defendants’ witnesses (D.

App. 221A-228A). Prior to the choice period, there had

been some let-up in the number of threatening and harass

ing telephone calls to the Coppedges, but after the period

began, the number rose to a peak of perhaps seven or

eight such calls per day (1278a-1280a). These calls con

tinued throughout the year and the last as to which there is

testimony took place three days before the trial (1280a).26

The choice period which was conducted under these condi

tions resulted in 45 Negroes selecting desegregated schools

—less than 1.5% of the total and a drop of four from the

previous year (D. App. 19A).

C. Defendants5 Attempts to Refute the Proof

of Intimidation.

The melancholy history represented by our Chronology

of Intimidation is uncontradicted, and no arrests have been

made of the perpetrators of any of these acts of violence

(370a-379a, 1482a). Unable to meet the proof of unchecked

26 Assorted other incidents, during the 1966-67 school year, including

one additional shooting into a Negro home, are listed in our Chronology

of Intimidation (249a et seq.). Unfortunately, the publicized intimida

tion did not end with the entry of the decree, and the Franklin Times

of September 14, 1967, reported a new shooting into the Coppedge resi

dence under the telling headline “ SHOTS FIRED INTO HOME OF

SCHOOL SUIT PLAINTIFF.” Further shots were fired into the Cop

pedge home on Christmas Eve, 1967.

(Franklin Times, December 28,1967.)

32

intimidation directly, the defendants have attacked it from

all directions. They allege that the District Judge should

not have considered some, or any, of the evidence (brief,

pp. 17, et seq.), or should not have believed the Govern

ment’s witnesses (p. 25), or should have disregarded tes

timony because plaintiffs or the Government called the

wrong witnesses (pp. 19-21), or used the wrong kind of

evidence (p. 34). They ask this Court to find that Judge

Butler was clearly erroneous in finding a relation between

the minimal progress in desegregation and the evidence

of intimidation—he should, they say (brief, p. 28), have

attributed this meager progress to lack of federally spon

sored “free lunch” programs at white schools, even though

not a single witness mentioned this consideration, and

even though it is the policy of HEW to assure that benefits

“ follow the eligible child who has transferred under the

school desegregation program” (1427a-1428a). Finally,

defendants called witnesses of their own and claim on

appeal to have proved that nobody was afraid of the in

timidations and that the reprisals did not have any effect.27

This case being on appeal, we believe that additional

discussion of credibility and like issues is superfluous. We

do wish to comment, however, on defendants’ claim (brief,

p. 26) that “ the learned trial Judge has in his findings of

fact been unduly influenced by sensational-sounding, hear

say, newspaper articles.” First, the articles in evidence are

not hearsay. They were not introduced to prove the truth

of their contents, but rather to show the publicity given

27 Defendants say (brief, p. 30) that plaintiffs and the Government

failed to produce a single witness who was influenced by fear during the

1967 choice period. While we think it unnecessary to call numerous wit

nesses to prove that shootings and bombings intimidate, defendants’

statement is simply inexplicable in the light of the testimony of Rev.

Arthur L. Morgan (1096a-1100a) and Ossie Lynn Spivey (1127a-1133a).

33

to intimidatory incidents in Franklin County. In most

instances, the fact of a shooting or bombing or similar

event was proved by competent testimony, and the news

paper article was introduced simply to show that news of

the incident was widely disseminated and therefore likely

to influence more people. In the few instances where

newspaper articles were used without independent proof

of the incident—e.g., the two shootings into plaintiff Cop-

pedge’s home after Judge Butler’s decision—their rele

vance was to show that people in Franklin County were

reading in their newspaper of intimidatory incidents, for

such reading alone may well inhibit choice. Finally, al

most all of the “ sensational sounding” articles are from

the Franklin Times, which is edited and controlled by the

defendant Fuller. See also Usiak v. New York Tank Barge

Company, 299 F.2d 808, 810 (2d Cir. 1962).28

This brings us to what the defendants apparently con

sider to be their affirmative non-intimidation case. A num

ber of Negro parents and students testified on behalf of

the defendants to the effect that it was not fear, but rather

preference for schools with which they were familiar and

in which they or their children had friends, that led them

to return to all-Negro schools (D. App. 102A; D. App.

197A; 1163a, 1183a, 1189a). W hile many of the witnesses

had heard of some or all of the acts of violence or intimida

tion which had occurred in the county, they testified that

28 Newspapers have been admitted or used for various purposes in

assorted civil rights cases. See, e.g., Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd.

of Educ., 369 F.2d 29, 31 (4th Cir. 1966); Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp.

872, 879-881 (S.D. Ala. 1949), aff’d. 336 U.S. 933 (1949); United States

v. State of Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353, 375-376 (E.D. La. 1963); aff’d.

380 U.S. 145 (1965); Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F.

Supp. 649 (E.D. La. 1961), aff’d. 368 U.S. 515 (1962). Cf. Dallas Co.

v. Commercial Union Assurance Co., 286 F.2d 388 (5th Cir. 1961).

34

they would have returned to all-Negro schools anyway

(D. App. 100A; D. App. 1Q2A-103A; D. App. 133A-134A;

D. App. 152A). Much of this is inevitable; where, as here,

a school board, as a result of its faculty assignment and

other dual system policies, offers Negroes a choice be

tween schools identifiable as white or Negro (1175a, 1236a,

1285a), rather than between genuinely desegregated

schools, Negro pupils will inevitably be encouraged to

select the schools maintained for them. See Kiev v. County

School Board of Augusta Cty., Va., 249 F. Supp. 239, 247-

248 (W.D. Va. 1966).

The testimony adduced by defendants may support a

contention that intimidation and fear were not the only

reasons for Negroes remaining at all-Negro schools. It

could even be argued that such evidence would have sup

ported a finding (had the District Court made it) that

there were some Negroes who were so brave that the

prospects of shootings, explosions, telephone harassment,

well pollution and the rest would not make them hesitate

to elect desegregated schools for their children, although

even here several of the witnesses conceded that they had

no way of knowing if they would suffer reprisals or not,

and it is incredible that they did not care (1232a, 1236a,

1255a).29 What these witnesses could not, and did not,

show was that choice in Franklin County was free. Their

testimony does not support the contention that it was

sheer coincidence that the amount of desegregation was

low where the level of intimidation was so high. In fact,

29 Mrs. Ollie Strickland, a Negro mother, was one of those who testified

that she was not afraid, but on cross-examination acknowledged that

Negroes get along fine if they stay in their place, and that she was not

afraid because she did not plan to get out of her place (1241a). Much

of the testimony of lack of fear is most readily understandable in the

context that Negroes who chose Negro schools had nothing to be afraid

of (1252a-1253a).

35

many of the defendant’s witnesses conceded the contrary.

A few examples follow:

(a) Gladys Hayes, Negro mother, sent her children

to all-Negro Perry’s because that was where they

wanted to go, but admitted that in fact they did

not know how they would be treated at a white

school and that they were “kind of afraid to find

out” (1243a-1244a).

(b) Evelyn Harris, Negro high school honor student

who selected all-Negro Riverside school, acknowl

edged that the Klan is strong in Franklin County,

that she knew of numerous incidents of intimida

tion which happened to Negroes who elected de

segregated schools, that she attributed these in

cidents to their choice of white schools, that some

Negroes were certainly afraid to select white

schools, and that their number might well be

quite substantial (1246a-1251a). See also the simi

lar testimony of fellow student Veronica Hawkins

(1252a-1255a),

(c) Ira Bowden, white, aged 66, a neighbor of the

Coppedges who has lived in Franklin County all

his life, acknowledged that the Klan had been

strong in Franklin County for years, that it was

known to be against integration generally and

school integration in particular, and that he, like

the Negro mother Ollie Strickland, was not afraid

of the Klan simply because he was doing nothing

to offend it (1158a-1162a).

(d) Mrs. Mattie W. Crudup, Negro grandmother, testi

fied that she sent her grandchildren to all-Negro

Gethsemane voluntarily and felt that the small

number of Negro teachers and pupils at Bunn

36

was a significant factor influencing her choice; if

there were more Negro pupils and teachers at

white schools, the Negro children would feel “more

free” (1180a).

(e) Mrs. Mattie 6. C. Harris, a Negro mother with

some college training, elected Gethsemane rather

than Bunn for her children because they preferred

it, although she recognized that Bunn had a

broader curriculum and that attendance there

would have obviated a long bus ride; she had

heard of some intimidatory incidents and was

familiar with the Klan; she believed the acts of

violence happened to people with children in white

schools, and that the white community was hostile

to desegregation; in general, she would prefer

each child to attend the school nearest to his home

(1165a-1170a).

(f) Melissa Dean, Negro mother, elected to send chil

dren to all-Negro Perry’s school because she even

prefers a bad Negro school to a good white school;

she knew of several intimidatory incidents which