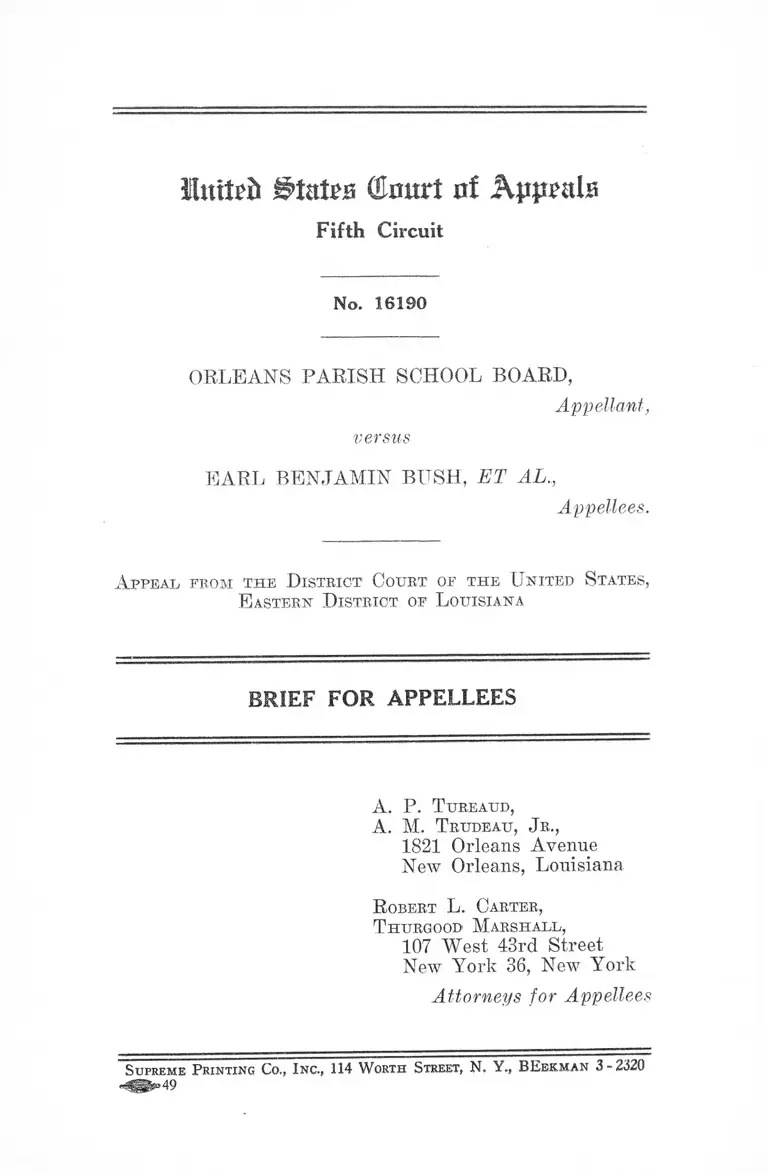

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush Brief for Appellees, 1960. 271fee69-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc6ad45e-8bcf-415c-b3c6-f2929868d155/orleans-parish-school-board-v-bush-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

lulled flutes CEnurl of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

No. 16190

ORLEANS PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

Appellant,

versus

EARL BENJAMIN BUSH, ET AL„

Appellees.

A ppeal from the District Court of the United States,

E astern D istrict of L ouisiana

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

A. P. T ureaud,

A. M. Trudeau, Jr.,

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street

New York 36, New York

Attorneys for Appellees

S upreme P rinting Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y„ BE ekm an 3-2320

States ©nurt ni Appeals

Fifth Circuit

No. 16190

----- ------- ----------o------------------ -—

Orleans Parish School B oard,

Appellant,

versus

E arl Benjamin B ush Et Al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal from the D istrict Court of the United States,

E astern D istrict of L ouisiana

-----------——---- o---------------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement

The constitutional and legal questions in this ease are

quite uncomplicated, and there is no question hut that the

concepts of law which must be applied to their determina

tion make it mandatory that the judgment of the court

below be affirmed.

Appellant seeks in its comprehensive brief to transform

the elementary questions inherent in this case into com

plex problems of formidable proportions. But the issues

are just not susceptible to treatment of that sort. All that

is involved in this case is whether the principles enunciated

by the United States Supreme Court in its two decisions

in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, and 349

IT. S. 294, are applicable to the Orleans Parish Public School

System when the equitable jurisdiction of the court below

is invoked by residents of Louisiana claiming an invasion

of rights and privileges secured under the Constitution of

the United States. That and that alone is all this case

is about.

In November, 1951, appellees had petitioned the appel

lant school board to reorganize the public schools of the

Parish so as to discontinue discrimination on account of

race (R. 44-45). This was denied (E. 45), and an appeal

was taken to the State Board of Education where it was

also denied (E. 46).

A complaint against the school board was filed in the

court below in 1952. Contrary to appellant’s assertion, an

examination of the original complaint discloses that it

raised questions concerning the constitutionality of segre

gation per se, as well as alleged a denial of constitutional

rights by virtue of the various inequalities in physical

facilities which appellant permitted to exist in respect to

its operation of segregated schools for Negro children.

Pursuant to agreement among counsel the cause was held

without further action, pending the United States Supreme

Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, supra.

After the second decision in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, and specifically on June 27, 1955, appellees appeared

before the school board and again requested that it reor

ganize the public schools on a nondiscriminatory basis

(R. 46). A further petition was filed on July 10 (R. 47).

On August 29, 1955, appellant reaffirmed its present policy

of racial segregation and appointed counsel now handling

this appeal to defend it in this case and to act as its counsel

in any suit brought by or against the Board involving segre

gation (R. 48-51). On August 18th, having heard nothing

from appellant in respect to their petitions of June 27 and

July 10, appellees filed an amended complaint (R. 19) in

the court below attacking' the constitutionality of Sec

tion 81.1 and 331 of Title 17, Louisiana Revised Statutes

3

(Acts of 1954, No. 555 and 556), as well as Section 1, Article

12 of the Constitution of Louisiana on the grounds that

these provisions were in fatal conflict with the Constitution

of the United States. Injunctive relief against enforcement

of this state policy was requested in a motion for a tem

porary injunction filed the same day (R. 16). The statutes

in question had been enacted in 1954 after the first decision

of the Supreme Court in the School Segregation Cases

(Brown v. Board of Education) and were openly designed

to circumvent and avoid compliance with that decision.

On December 2, 1955, hearing was held on appellees’

application for preliminary injunction and on all other

motions (R. 43) before a statutory district court of three

judges. On February 15,1956, that court filed a per curiam

opinion in which it stated it had found no serious constitu

tional questions presented in this case not heretofore de

cided by the United States Supreme Court in Brown.

Hence it dissolved the three-judge court and turned the

matter over to the regular district court in which cause

had been filed (R. 122-124). The latter court disposed of

the case that same day by holding racial segregation in

public schools in Orleans Parish invalid on the basis of the

Brown decision (R, 125-131), and by issuing a decree re

straining' and enjoining appellant “ from requiring and

permitting segregation of the races in any school under

their supervision, from and after such time as may be

necessary to make arrangements for admission of children

to such schools on a racially nondiscriminatorv basis with

all deliberate speed . . . ” (R. 132-133).

Appellant filed a motion for leave to file a petition for

writ of mandamus in the United States Supreme Court

attacking the ruling and decree now before this Court on

the ground that Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2281-

2284 required the questions here in issue to be disposed of

by a three-judge court. This motion was denied, 100 L. ed.

(Adv. p. 690) decided May 28, 1956. Thereupon, appel

lant brought the matter here.

4

ARGUMENT

The Judgment of the Court Below Is Clearly Cor

rect and Should Be Affirmed.

Much of appellant’s brief is taken up with exhaustive

argument on questions which are foreclosed. Appellant

seeks to reopen and relitigate here basic principles of

federal jurisdiction and constitutional law which the

United States Supreme Court has heretofore decided con

trary to appellant’s contentions. If the law is to change

with respect to federal jurisdiction, class action, procedural

requirements for litigation in the federal courts, that

change cannot be made in this forum. Yet, all of appel

lant’s argument is devoted to these questions and those in

a similar category.

The court below has given adequate answer to appel

lant’s contention that this is a suit against the state (R. 126-

127), and has cited Georgia R. Co. v. Redwine, 342 U. S.

229, and the cases there collected in Notes 14 and 15 at

page 304. In Ex parte Young, 209 U. S'. 123, the Supreme

Court reviewed and restated its position that suits to en

join state officers from acting illegally are not suits against

the state. Since that time this has become accepted as a

basic principle of law.

The long series of cases dealing with racial discrimina

tion as a denial of rights secured under the Fourteenth

Amendment have necessarily involved state officers as

defendants, see Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 469; McLaurin

v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. Yet federal

jurisdiction was found. In several eases of this kind, objec

tion was made to the exercise of federal jurisdiction on

the ground that the suit constituted a suit against the

state and one, therefore, over which federal jurisdiction

was lacking—the argument appellant makes here. These

5

objections were found to be either so frivolous or lacking

in merit that almost uniformly federal jurisdiction was

sustained without even a mention of this objection. That

issue was raised in this Court as recently as Board of

Supervisors v. Tureaud, 225 F2d 434, (1956), reversed, 226

F2d 714, vacated en lane and order in 225 F2d 434, rein

stated, 228 F2d 895, but again decision was reached without

mention of this question. And it is, of course, clear that

Brown v. Board of Education and this case are identical

in that both cases seek injunctive relief in a federal court

against the allegedly unconstitutional action of public

school officials.

In short, appellant has no support in any of the cases

decided in the past 50 years for the doctrine they have pre

sented so extensively in their brief. Indeed, appellant is

arguing for a policy which would deny jurisdiction to the

federal courts over any controversy between public officials

and residents of the same state in respect to the enforce

ment of any discriminatory state policy in violation of

rights secured under the Constitution of the United States.

Undoubtedly this is the reason the law is so universally to

the contrary.

That this is an actual controversy, that appellees are

threatened with irreparable injury and that this is proper

class action is unquestioned. To reach any other conclu

sion would be to forget that such cases as Swecitt v. Painter,

339 U. S. 629; Brown v. Board of Education, supra; Wilson

v. Board of Supervisors, 92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La. 1950),

aff’d, 340 U. S. 909, had ever been decided.

Appellant objects to the form in which the cause was

brought in that suit was filed by the “ next friend” of

infant appellees. There is no question but that this form

complies with the procedural requirements of the federal

courts. See Rule 17 of the Federal Rules of Civil Proce

dure. In this case the real parties in interest are the

children who desire to attend nonsegregated schools.

6

Under Article 108, Louisiana Code of Practice (See p. 64

and pp. 59-68 of appellant’s brief), if this action had been

brought in state courts, it would have been necessary for

it to have been brought on behalf of the children by their

tutors. But there is no such requirement in respect to fed

eral practice. Rule 17(c) provides as follows:

Infants or Incompetent Persons. Whenever an

infant or incompetent person has a representative,

such as a general guardian, committee, conservator,

or other like fiduciary, the representative may sue

or defend on behalf of the infant or incompetent

person. If an infant or incompetent person does not

have a duly appointed representative he may sue

by his next friend or by a guardian ad litem. The

court shall appoint a guardian ad litem for an infant

or incompetent person not otherwise represented in

an action or shall make such other order as it deems

proper for the protection of the infant or incompe

tent person.

Rule 17(c) above sets forth the procedural requirements

for the prosecution of suits involving minors in the federal

courts. Since this is merely a question of procedure, the

rules of the forum in which suit is brought are controlling.

See Montgomery Ward <& Co. v. Callahan, 127 F2d 32 (10th

Cir. 1942); Constantine v. Southwestern Louisiana Insti

tute, 120 F. S'upp. 417 (W. I). La. 1954). No state may

abridge or prescribe the procedural requirements which

obtain in a federal court. As it was said in Constantine

v. Southwestern Lousiana Institute, supra, at 418:

Rule 17(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Proce

dure, 28 U. S. C., provides that where an infant or

incompetent person does not have a duly appointed

representative he may sue by his next friend. This

right cannot be abridged by a State statute.

7

As was hereinabove indicated, appellees have more

than exhausted their administrative remedies. They have

made several unsuccessful appeals to appellant-board and

the superintendent of schools to conform to the require

ments of the law. Instead of taking steps to eliminate racial

discrimination in the public schools under its control, appel

lant stubbornly stood fast and employed special counsel to

defend its unconstitutional policy in any litigation brought

against it.

The statutes held unconstitutional (No, 555 and 556

of the Acts of 1954) by the court below are a part of

a plan designed by the legislature to maintain segregated

schools despite the Supreme Court decision. These Acts

and any similar legislation designed to maintain segregated

schools fall under the ban of the Brown decision. Indeed,

this case is on all fours with Brown v. Board of Education,

and its disposition, as held by the court below, is controlled

by that decision.

Beginning at page 84 of its brief, appellant seeks to

relitigate Brown v. Board of Education, supra, on the

merits. Whatever rationale impressed the Supreme Court

in reaching its decision that enforced segregation in public

schools is at variance with constitutional requirements, that

decision is now the law of the land and must be followed

and applied by inferior courts. Whether the rationale

utilized by the Court is sound or should be reconsidered is

an argument which appellant may properly address to the

United States Supreme Court but not to this forum.

8

The decision of the court below is, Ave submit, a proper

and correct application of controlling principles of law in

both their substantive and procedural aspects, and as such,

the judgment of the court beloAv should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

A. P. T ureaud,

A. M, T rudeau, Jr.,

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street

New York 36, New York

Attorneys for Appellees