Sweatt v. Painter Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 17, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sweatt v. Painter Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1950. 623f489d-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc808f93-764c-438a-b174-7a1cef86e044/sweatt-v-painter-motion-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

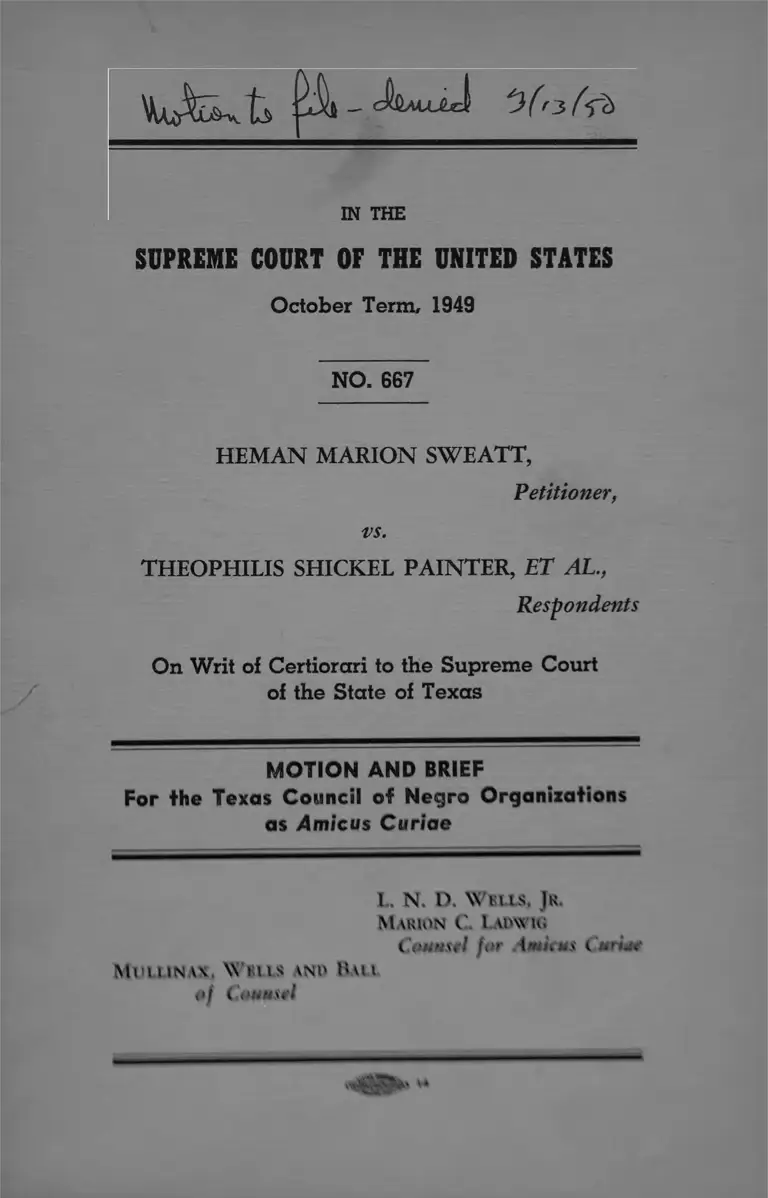

SUPREM E CO U RT OF THE U N ITED S T A T E S

October Term, 1949

NO. 667

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

Petitioner,

vs.

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER, ET AL.,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Texas

MOTION AND BRIEF

For the Texas Council of Negro Organizations

as Amicus Curiae

1 . N. D. W ells. Jr.

Marion C. Ladwu;

Counsel for Aotiius Curue

MlU l IN W. Win IS ANO IVvi l

of Ct»t*usel

* V*

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae.......................... 1

Brief for the Texas Council of Negro Organizations as Amicus

Curiae .......................................... 5

Opinions Below and Jurisdiction......................................... 5

Statement of the Case ................................................................ 5

Summary of Argument ....................... 7

Argument .......................................... 8

1. Education .............................................. 12

2. Politics :................................................................................... 18

3. Other Areas of Crumbling Segregation Barriers...... 19

Conclusion .................................................................................................. 22

APPENDIX

A. List of State-Wide Affiliates of the Texas Council of Negro

Organizations .......... 25

B. Consent of Petitioner for Filing Amicus Curiae Brief ........ 27

C. Report of First Negro Student to Enter the Medical School,

University of Texas ............................................................................ 28

D. Report of First Negro Student to Enter the Law School,

University of Oklahoma ................................................................... 29

E. Report of First Negro Student to Enter the Medical School,

University of Arkansas ................. 31

F. Excerpt from The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. X IX ,

No. 1, Winter, 1950 ........................................................ 33

G. Article Printed in The Dallas Morning News, Negro attack

on Segregation, February 2, 1950 ............... 36

H. Report on Interracial Activities, Texas Methodist Student

Movement, Rev. Paul Deats .......................................................... 40

(i)

CASES CITED

PAGE

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 US 45 .......................................................... 18

Nixon v. Condon, 286 US 73 ............................................................... 18

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 US 536 .......................................................... 18

Oyama v. California, 332 US 633 ........................................................ 22

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 US 537 ........................................... .7, 8, 18, 22

Smith t*. Allwright, 321 US 6 4 9 ............................................................ 18

West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, 300 US 379 ........................................ 22

OTHER AUTHORITIES CITED

PAGE

Allen. J. S., The Negro Question in the United States, New

York, 1936 ____________________________________________ 11

The Crisis, Vol. 57, No. 1 ("Southern College Teachers Repu

diate Jim Crow”) _______________________________________ 17

The Daily Texan. Jan. 10, 1950 ......................... ................................ 17

The Dallas Morning News, Feb. 2, 1950 ............... ...........................19

13 Federal Register 4311, July 26, 1948 _____________________20

Fraiier, F. Franklin, The Negro in the United States, Macmil

lan. New York. 1949 _________________________________ 9s, 11

5 See<\\ Negro Problem." Encyclopaedia of the So

cial S d tK tt X I .............................. ........1__________________ 4 i i

rice: "a.\ F "... Race Traits and Tendencies of die Nrer-cm

Negros New York. tSdT..................... ............................................ 11

cv— .a oc Negro VAscarocv, Y e l XIX . Ncv 1. Rt’inrser. i4Sl__ I?

Y . tX, Swuhtwi M ilisCis Knffe. New Y«ek 1SMI_____ a

-sex'. . x*nr. c s s •: :d Fa.-ov. v V .v c '.■-•ansc* - s s .

» ......... ................................. ............ 9

v - „V -\* N x - v idiC', New Y -cs . .AX : :

vsnnns c- Amt'.'K*.* TYtarnwac New Tax. x ™.

New Yrck Times. Sqpmfcer Tic ___________________ Id

The Oklahoma D kiX Tan. 15, 1948 ........................ ..... ................ >s

The Oklahoma Daily, Nov. 10, 1949 .................................................

The Oklahoma Daily, Dec. 16, 1949 .................................................

Oklahoma Statute, House Bill No. 405, 1949 .................................

Page, T. N., The Negro, The Southerners’ Problem, New York,

1904 .......................................................................................................

The Postal Bulletin, Sept. 20, 1949 ("Procedure relative to fair

employment practices” ) .............................................................. .

Proceedings, Texas State Federation of Labor, 50th Conven

tion, 1948, Fort Worth, Texas, June 21-June 24......................

San Antonio Register, April 9, 1948 ...................................................

Simpkins, B. F., The South, Old and New, Knopf, New York,

1947 ............................................. .................................................. 8, 9,

The Southern Patriot, New Orleans, La., Vol. 7, No. 8, Oct.,

1949 ......................................................................................................

Stone, A. H., Studies in the American Race Problem, New

York, 1908 .........................................................................................

Strong, D. S., The Rise of Negro Voting in Texas, 1948 Amer.

Pol. Sci., Rev. 42 ..............................................................................

Thomas, W . H., The American Negro, New York, 1901.............

Thompson, Charles H., "Separate But Not Equal,” Southwest

Review, Southern Methodist Univ. Press, Dallas, 1948,

Vol. X X X III, No. 2 ...................................................................16,

14

14

13

11

20

20

19

10

15

11

18

11

17

IN THE

SUPREM E COURT OF THE UNITED S T A T E S

October Term, 1949

NO. 667

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

Petitioner,

vs.

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER, ET AL.,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Texas

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AS AMICUS CURIAE

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

The undersigned, as counsel for and on behalf of the

Texas Council of Negro Organizations, respectfully move

that this Honorable Court grant them leave to file the ac

companying brief as amicus curiae. The Texas Council of

Negro Organizations is made up of forty-five state-wide

organizations, fraternal, political, religious, educational, or

social,' and has as its principal purposes "to serve as a clear

ing house of information and opinion on Negro life and

interracial affairs in Texas, to sensitize the Negro people

of Texas to the rights and responsibilities of worthy citizen

ship in a democratic society of free men, and to make au

thorized representation of social, economic, political and

educational issues affecting the well-being of the Negro

people of Texas.”

Current social and economic data, relevant to this Court’s

determination of the reasonableness of the classification at

issue, is available, and has not been brought to the atten

tion of the Court by either the parties to this cause or other

amici curiae. In order that such data will be available to the

Court, the Texas Council of Negro Organizations respect

fully requests leave to file the accompanying brief.

The Council makes this request, believing that the de

cision by this Court in the case at bar will largely influence

the rate of progress which millions of American Negro

citizens will make in achieving their aspirations of first-

class citizenship through equality of educational oppor

tunity, and being cognizant of the fact that the decision

herein will determine the right of members of affiliated or

ganizations and their sons and daughters to attain the edu

cational advantages to which they believe themselves en

titled as citizens of the United States.

Consent of the attorney for petitioner to the filing of 1

1 A list of the constituent organizations is set forth in Appen

dix A.

2

this brief has been obtained.2 Consent of the attorney for

respondent was requested on December 22, 1949, but no

reply to such request has as yet been received. W e are to

day submitting copies of this motion and brief to attorney

for respondent and renewing our previous request that he

consent to the filing. Such consent, when received, will be

promptly submitted to the Court. In the event such consent

is not received, we respectfully pray that leave to file this

brief be granted notwithstanding. Cf U. S. Supreme Court

MULLINAX, WELLS AND BALL

of Counsel

1716 Jackson Street

Dallas, Texas.

February 17, 1950

STATE OF TEXAS )

COUNTY OF DALLAS J

Before me, the undersigned authority, on this day ap

peared L. N. D. Wells, Jr., who being duly sworn, deposed

and said that on this 17th day of February, 1950, copies

of this motion and the attached brief were served by reg

Rule 27, par. 9 (c).

Marion C. Ladwig

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

3

istered mail, return receipt requested, upon the Honorable

Price Daniel, Attorney General of Texas, Capitol Building,

Austin, Texas, counsel for respondent herein, and upon the

Honorable Thurgood Marshall, 20 West 40th Street, New

York 18, New York, counsel for petitioner. 2

2 A copy of petitioner’s consent is appended hereto as Appen

dix B.

Su san Gates M orrow

Notary Public in and for

Dallas County, Texas

4

IN THE

SUPREM E COURT OF THE UNITED S T A T E S

October Term, 1949

NO. 667

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

Petitioner,

vs.

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER, ET AL.,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Texas

BRIEF FOR THE

TEXAS COUNCIL OF NEGRO ORGANIZATIONS

as Amicus Curiae

OPINIONS BELOW AND JURISDICTION

The opinions below and jurisdictional statements are set

out in full in the brief for the petitioner.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The petitioner, Heman Marion Sweatt, upon applying

for admission to the University of Texas Law School ap-

5

proximately four years ago, was denied admission solely

because of his race (R 445). Sweatt then brought a man

damus action in a State District Court to compel the State

University to admit him as a qualified student. This relief

was denied in three separate hearings in the District Court,

and also by the Texas Court of Civil Appeals, and the Su

preme Court of Texas; each of these courts holding that

denial of admission to State University graduate schools to

Negro citizens was not violative of the Negro citizen’s

rights to equal protection of the laws nor of his rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States, so long as "separate but substantially

equivalent” educational facilities were afforded on a basis

of race segregation.

That the Texas Courts erred in holding that the educa

tional facilities offered petitioner were "substantially

equivalent” to those afforded non-Negro citizens is plain

from this record. Inasmuch as this point is so apparent from

the undisputed facts of this case, and is fully briefed by

petitioner and by the amicus curiae, the American Jewish

Committee, we will not burden the Court with a restate

ment of argument on this point.

W e shall limit our argument to the following point:

6

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The "sep a ra te but equa l" doctrine of Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 US 537, (upholding state racia l seg

regation statutes) now has no justification when

applied to public education on the un iversity

graduate level, and should be rejected as a v io

lation of the "equa l p ro tection " clause ©f the

Fourteenth Am endm ent to the United States C on

stitution.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 US 537, decided fifty-four years

ago, held a state statute requiring segregation of the Negro

race to be a reasonable exercise of the state’s police power,

and justified to preserve the "public peace and good order.”

That case was erroneously decided in 1896, based on the

then prevailing popular and scientific misconception that

the Negro race was inferior, and that a commingling of

the "superior” white race with the "inferior” Negro race

would lead to public disorder. More than fifty years of

learning and experience have demonstrated that no reason

able justification exists for classification (at least for pur

poses of public education at the graduate level) on the

basis of race. Racial segregation in the circumstances dis

closed by the record in this case has now been proved un

necessary for the maintenance of public peace and good

order. Experience in the fields of education, politics, mili

tary service, religion, labor and business has demonstrated

that racial segregation in graduate public education is not

necessary or justified to preserve the public welfare.

7

ARGUMENT

When, in 1896, this Court held in Plessy v. Ferguson that

a state statute requiring segregation of Negro citizens did

not transgress constitutional limitations, the decision was

placed on the sole ground that racial segregation was justi

fied to preserve the public peace and good order. Even in

that day, and in that very case, it was recognized that:

. . every exercise of the police power must be

reasonable, and extend only to such laws as are

enacted in good faith for the promotion of the

public good, and not for the annoyance or op-

-pression of a particular class.” (163 US 537 at

550.)

The Supreme Court of 1896, laboring under the social

pressures of irrational race prejudice too commonly ac

cepted by the public at that time, and misled by the "scien

tific” misconceptions of such distinguished scholars as

Charles Darwin, Francis Galton, Thomas Carlyle, and

Cesare Lombroso, all of whom affirmed the doctrine of

Negro inferiority,' held it to be a reasonable exercise of the

states’ police power to require racial segregation in intra

state travel.

That Court was functioning in a climate of race preju

dice; indeed. Mr. Justice Harlan, in his dissent vr. tear <erv

case, points up the fact chat the rraorvo decrstct- rased

on the proportion that race nrerc.vv.ce teg-ardsai 'ns

the supreme law of the lard At that tv.tv . re s r o a s s cc

' Cl, 1. If, Ttif SnA 4Nki 4mI N<(w, OhmS, New

Y.'. v. Cha.xet W .Y . racvxv V. A v . Vs

- VS esv

sociology and anthropology were in their infancy. The

strong glare of the light of fifty years’ experience had not

yet demonstrated the extent to which the theory that the

Negro was inferior to other races was wholly fallacious.

The Negroes’ opportunity to prove how fallacious such

theories were, was everywhere blocked. No opportunity ex

isted to prove ability to improve occupational status.3 Fifty-

seven percent of the Negro race was illiterate in 1890; no

Negroes voted in the South.4 The Negroes of that day were

commonly regarded as unfit to perform the functions of

citizenship.5 As a recent scholar reports:6

"During the period when 'white supremacy’ was

being established in the South there was continual

racial conflict. Sometimes there was conflict be

tween individual whites and Negroes; at other

times racial conflict took the form of organized

violence. During Reconstruction the Negroes met

the organized violence of the whites with some

type of collective action on their part and the

racial conflict developed into race riots. But grad

ually the organized resistance of the Negroes de

creased and individual Negroes became the vic

3 Cf. Harris and Spero, "Negro Problem,” Encyclopaedia of the

Social Sciences XI, p. 339.

4 Simpkins, op. cit., p. 406.

5 Senator Vardaman spoke what was too commonly accepted

in his day when he stated: ". . . it matters not what his (the

Negro’s) advertised mental and moral qualifications may he. I am

just as much opposed to Booker Washington as a voter, with alt

his Anglo-Saxon re-enforcements, as I am to the cocoanut headed,

chocolate-colored, typical little coon, Andy Dotson, who blacks my

shoes every morning. Neither is fit to perform the supreme tunc

tion of citizenship.” (Lewinson, Paul, Race, Class and I'aiiy, pp.

84-85, Oxford University Press, 1932.)

6 Frazier, E. Franklin, The Negro in the United States, pp. 159-

160, Macmillan, New York, 1949.

9

tims of the organized violence of the whites. A

rough indication of this type of violence is pro

vided in the statistics on Negroes lynched in the

South. Lynchings in the South increased rapidly

from 1882, the first year for which statistics are

available, up to 1890 and then showed a sharp

rise in the early nineties when the white South

began to legalize the subordinate status of the

Negro. (See Diagram I.) Although the majority

of the Negro victims were lynched for homicide,

the avowed justification for lynching was the

raping of white women. In over 10 percent of the

cases the alleged cause for lynching Negroes in

cluded insulting white persons, robbery and theft,

and a host of minor offenses. It appears that the

lynching of Negroes was essentially an informal

type of 'justice’ designed to 'keep the Negro in

his place.’ Community sanction for this type of

’justice’ was based upon the general belief that

the Negro was a subhuman species and the fear

that the Negro would get 'out of hand.' Lynch

ing has been one of the fruits of the crusade to

establish 'white supremacy.’ "

hi stem me Negroes unfortunate status at the time of

■Sun i i r t a s / # was,, is reported by Simpkins:'

rererr o f rece of p n lk io l and social etfoaLrr-

r me a L ssa o n a i re debacle. me Negroes' si ma

nor was- naeec utmeemmate reward me and e£

me Nmeesnm Cmcrrv . . The feemme of wmre

smrrmniBcy jg rae E xd eccrriecer- — t—S - r r r o ^ e :

me AawBfacant treed of eyuairty. Ftesc aegtnnencs

roGCsmrng me alleged r e g a b o ef me ace for

m r :- emerc -sremed re re eottfanned a xs own

m errai weaknesses! x '*e tr-. ndustr-m inet-

~cr«£ie--. mine ax- ill leu. m .'

r\rru<mr~ if rrac oa exx-ased r x Nevcce as m e r u t ’

mu srngjit tr user ’w-r.ee ssrptsmac ’ on me nests n *

rvr. oc. 3-.

31

scientific fact.8 But the fallacy of these views is now too

apparent to require exposition. A comparison of the popu

lar and scientific appraisal of the Negro as made in the

works cited in footnote 8 with the data and conclusions of

more modern scholars 9 demonstrates not only the tremen

dous strides made in the social sciences, but the utter fallacy

of the attitudes which were extant at the time Plessy v.

Ferguson was decided.

W e submit that what the beliefs and attitudes of 1896

led the Court to hold to be a reasonable exercise of the

police power for the public good, today, five and one-half

decades later, in the light of the knowledge and experience

of 1950, is demonstrably unreasonable and unrelated to the

public welfare.

But not only have modern social scientists exploded the

myth of white supremacy, the Texans’ everyday experiences

daily demonstrate that despite compulsory segregation laws

of the type held reasonably necessary to the public safer,

in 1896, segregation in Texas and the South is rapidly be

s Hoffman, F. L., Race Traits and Tendencies of tbe American

Negro (New York), 1897; Thomas, W . H., Tbe American Negro

(New York, 1901); Stone, A. H., Studies in the American Race

Problem (New York), 1908); Page, T. N., Tbe Negro, Tbe South

erners’ Problem (New York, 1904); Murphy, Problems of tbe

Present South (New York, 1909).

9 Myrdal, Gunnar, An American Dilemma (two volumes, New

York, 1944); Harris and Spero, ''Negro Problem,” Encyclopaedia

of the Social Sciences, XI, pp. 335-55; Allen, J. S., The Negro

Question in the United States (New York, 1936); Frazier, F..

Franklin, The Negro in the United Stales (New York, 1949).

coming as outmoded as the popular and scientific views

which two generations ago sought to justify it.

Particularly in the last four years, since the Second World

W ar, rapid strides have been made in interracial activities.

A few typical examples are here presented.10 *

1.

Education

Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas have had recent experi

ence with Negroes attending graduate schools of their re

spective state universities on an equal and unsegregated

basis. In September, 1949, Herman A. Barnett, a Negro

from Lockhart, Texas, was admitted to the University of

Texas Medical School." Barnett is presently obtaining all

the advantages of non-segregated education; his laboratory

partners are white students. Barnett is fully accepted by his

To the extent possible, we have attempted to present the

current fact and opinion with respect to racial segregation in this

area from standard works or acknowledged experts in the field.

Due to the rapid advances, and the fact that much of such material

is so recent as not to have yet been authoritatively published, we

have in several instances presented affidavits from those with

knowledge of the facts. These are included in the Appendix hereto.

W e note that the Attorney General of Texas, in his brief on behalf

of respondents, likewise has appended to his brief in opposition

to granting the writ certain reports, poll results, and other data

with respect to the current situation.

' 1 Barnett is technically enrolled in the Texas State University

for Negroes at Houston under a contract with the University of

Texas covering graduate instruction not offered by the Houston

institution.

12

professors and fellow students, and has pursued his studies

without incident.12

And in Oklahoma, Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, the plaintiff

in Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, 322 US 631, is now attending the University of Ok

lahoma Law School. The semblance of segregation was at

first maintained by "Reserved for Colored” signs placed

beside the Negro student’s desk. But even this gesture to

ward legislative insistence on segregation 13 has not de

terred white students from acceptance of Mrs. Sipuel Fisher

and other Negroes as any other members of the class. Those

who hold to the philosophy on which Plessy v. Ferguson

was based may be shocked to learn that Negroes at Okla

homa today eat and study with white students, are housed

on the University campus, and are accepted by fellow stu

dents without incident; indeed, that the "Reserved for Col

ored” signs posted by the Law School have been removed

by white students.14

Mrs. Sipuel Fisher’s experience is not an isolated one.

About fifty other Negro students entered various schools

of the University at the same time, the summer term, 1949.

Student reaction to this phenomenon has been good. By

12 See Barnett’s report attached hereto as Apuendix C, p. 28,

infra.

is See Oklahoma statute, House Bill No. 405, approved by

Governor on June 9, 1949, amending 70 O.S. 1941, Sec. 455-7.

i4 See Mrs. Sipuel Fisher’s report attached hereto as Appendix

D, pp. 29, 30, infra.

13

November, 1949, when 22 Negro students were enrolled for

the fall semester, majoring in varied subjects ranging from

pharmacy and zoology to social work and school admin

istration,’5 a great majority of the students indicated ap

proval. The November 10, 1949, issue of The Oklahoma

Daily, page 2, the student newspaper serving the University

of Oklahoma, reports as follows:

"Seventy-six percent of the students and faculty

members are in favor of removal of segregation

on the campus. This is the result of a poll taken

by the Equal Education Committee. A total of

1,092 persons were interviewed. Every school in

the university was contacted. Allowing for a wide

margin of error, it can be stated that a majority

are in favor of removing the 'reserved for col

ored’ srgrrs . _

rdirncai commenr in me Oklahoma student paper is like-

vise n d c i r i e ar u.w me sn cerr body reacts to the "proc-

-em ar segregation. A eac ecircriai :r. T be Oklahoma

— •mt namriv pracfiemci v m scstacm oc h e end of "Em

’v n - kuanuna. ror:i~es :r N eg ri jr .o e rr - a r m s ~~-

iru Tism iret u :cns: issues a: me same ic - i , . - n r '

ir. rnilwatei. ar Oklahoma A. and M. College, five Ne

groes were enrolled at the fall 1949 semester. Investigation * 16 17

’5 The Oklahoma Daily, Dec. 16, 1949, p. 2.

16 During the pendency of the Sipucl case, a student poll taken

at the University indicated only 43.6 percent of the students fav

ored admission of Negroes. (The Oklahoma Daily, Jan. 13, 1948,

p. 1.)

17 The Oklahoma Daily, December 16, 1949, p. 2.

14

by one of the undersigned disclosed that no segregation is

there enforced, even in the seating arrangement of the

classes, despite the requirement of the Oklahoma statute

cited in footnote 13, supra.

The admission of Negroes to Oklahoma graduate schools

has significantly pointed up the rapid change of attitudes

not only of white students, but also of the townspeople.

Previously, the University City of Norman, Oklahoma, had

considered it an unwritten law that no Negro could remain

in the city after dark.18 Today Mrs. Sipuel Fisher has been

invited, along with other students, to have dinner in the

homes of white families in Norman.19

Similar experience is shown in Arkansas. Edith M. Irby

was the first Negro student to enter the School of Medicine

of Arkansas University. She reports that from the day of

her admission, September 27, 1948, the white students were

friendly, and at no time have given any indication that thev

resent her presence, despite the fact that she pursues her

course of study on a completely non-segregated basis. Miss

Irby’s report, appended hereto as Appendix E, p. 31, infra,

indicates a wholesome and naturally friendly relationship

with white fellow-students.

18 The Southern Patriot, New Orleans, La., Vol. 7, No. 8. Oc

tober, 1949.

19 See Appendix D, p. 30, infra.

15

Similar experience * 21 in Kentucky, Maryland, West Vir

ginia, Virginia, North Carolina, as well as cited examples

of unsegregated military experiences in the South, and other

specific experience in Texas, led a recent writer in a lead

ing southern journal to conclude:

"As far as I have been able to ascertain in the past

ten or more years, there has not come to public

attention a single instance of the elimination of

segregation in the South which has been attended

by any untoward results . . . These examples are

sufficient . . . to demonstrate that whenever and

wherever the leaders in any community decide

that segregation is to be eliminated and are will

ing to stand by their decision, no untoward con

sequences occur.”22

The same author recites examples in Texas of Negro and

white nurses being trained in the same classes without in

cident, of a Negro attending a technological school in

Texas for four years, but then receiving his degree from

the Negro college at Prairie View "because of some appre

hension over legal technicalities which might invalidate his

degree."23 Further, this same author reports that:

After the i ts: Sweatt trial a Negro student from

Camt-urs me xaam examples in other southern semes recked

i t 'S n o t Pragiess in the EHminarion of Discrimination H-.cber

i J a.-srt.-ia in the United States”, Id ] asertus} <-* A-C*v E emratim

1 at c (Reprinted in part as Appendix F, p. 55 ft. hrrra.)

Z1 Thompson. Charles H., "Separate But Not Equal”.

■a>est Reiicu Southern Methodist Unix. Press, Dallas. Yol.

X X X III, No. 2, pp. 105-112.

Ibid., p. 111.

16

one of the Negro colleges in Austin went over to

the University of Texas to borrow a book from

the library, and as he was waiting in line to have

his book charged, a number of students came up

and congratulated him, thinking that he was

Sweatt who had been admitted to the University.”

The author concludes:

"It is interesting and instructive to note that the

reaction of students is much more progressive and

constructive than that of their elders. In several

instances in southern universities where student

polls have been taken, only a few students were

seriously opposed to having Negro classmates.

Most of them were either favorable or indif

ferent.”24

The justification for this conclusion insofar as the Uni

versity of Texas student body is concerned appears in the

latest student poll taken there in March, 1948, at which time

61.5 percent of the women students and 54.9 percent of the

men students were in favor of Negroes attending not only

the Law School, but also other graduate schools.25

24 Ibid., p. 111.

z s The Daily Texan, Jan. 10, 1950, p. 1, col. 5. Cf. "Southern

College Teachers Repudiate Jim Crow”, The Crisis, Vol. 57, No. 1,

p. 25 ff., reporting a recent poll of 15,000 southern college teach

ers by the Southern Conference Educational Fund, Inc., in which

of the 3,375 who replied, 70 percent favored immediate admission

of Negro students to graduate and professional schools without

segregation.

17

2.

Politics

Mr. Justice Harlan, dissenting in Plessy v. Ferguson, re

ferred to "racial prejudice” as "the supreme law of the

land.” Insofar as political participation was concerned, this

was all too true at the time of that decision; indeed, sub

stantially so until after this Court’s decision in Smith v.

Alluright. 321 US 649 (1944).26 Even after that decision,

effort was made in parts of the South, notably South Car

olina and a few other southern states, to devise methods of

avoiding its effect; but as is aptly demonstrated in V. O.

Key’s scholarly Southern Politics,27 "the response of the

South to the Allwright decision is more significant for what

has not occurred than for the means that have been devised

to circumvent the Constitution.” Certainly, that is true in

Texas. Despite dire predictions of "trouble” should the

Negro be enfranchised in Texas, 75,000 Negroes voted in

the 1946 Texas Democratic primary without incident.28

The Negroes’ political activity is not today limited to the

casting of a ballot. The conservative Dallas Morning News,

26 This Court’s decisions in Nixon v. Herndon, 273 US 536

(1927), and Nixon v. Condon, 286 US 73 (1932), and Grovey v.

Townsend, 295 US 45 (1935), had resulted in some Negro voting

in general elections. Key, V. O., Jr., Southern Politics, Knopf, New

York, 1949, pp. 619 ff.

27 Ibid., p. 643.

28 D. S. Strong, "The Rise of Negro Voting in Texas”, Ameri

can Political Science Review, 42, (1948), pp. 510-22.

18

which on frequent occasion views with editorial alarm the

loosening of traditional race segregation patterns, in an

article by its chief political writer within the past few

weeks, reported on the effort of the Texas Negro to break

down segregation, as follows:29

"One victory is already won. That is on the politi

cal front . . . Today, Negroes not only vote in

the Texas Democratic primaries; they also par

ticipate in precinct, county and state conventions.

They sit with whites. Segregation has been wiped

out at Democratic conventions.”

Further indication of Negro political participation with

out incident of any kind is seen in the April, 1948, election

of a Negro business man, G. J. Sutton, to the Board of

Trustees of the San Antonio Junior College District.30 This

Negro leader had been sponsored by the interracial Organ

ized Voters League, which though predominantly white,

is headed by an equal number of Anglo, Latin, and Negro-

Americans.

3.

Other Areas of Crumbling Segregation Barriers

W e have demonstrated that integration of the races is

already occurring in Texas to some degree, and that in the

fields of education and politics such integration has not

29 Dallas Morning News, February 2, 1950, Sec, 111, p. 4, The

entire article is reprinted infra as Appendix C», pp. 59, IT.

30 San Antonio Register, April 9, I948, p I

been attended by any untoward result. The same is true in

other fields of social, religious and economic integration.

Texas Labor has recently taken a strong stand against

segregation. The Texas Scare Federation of Labor, ALL, at

its I94S convention, unanimously resolved:

T e a t ir be mandatory upon each city seeking and

acntrr.-g future conventions of the Texas State

Fereranctt of Labor to provide for a suitable

meed ag or conversion ha?'; where there shall be

r c f-s.---- r-arbor between race, color, or creed

r t ieaturx and servicing future delegates to Fed

eration conventions . . -”31

Toe Texas State Industrial Union Council, CIO, follows

the same practice.

And in everyday business life the Negro in Texas in 1950

daily rubs shoulders with Anglo and Latin-Americans in

Texas. The President’s executive order 9980 governing fair

employment practices within the federal establishment ef

fectively prohibits "discrimination because of race, color,

religion, or national origin” in federal employment in

Texas as well as throughout the nation.32 Pursuant thereto,

Negroes work with whites in the federal service. In Dallas,

Houston, and other Texas cities, Negro mail carriers and

clerks work with whites.33 Negro police protect life and

31 Proceedings, Texas State Federation of Labor, 50th Conven

tion, 1948, Fort Worth, Texas, June 21-June 24, pp. 210-211.

32 13 Federal Register 4311, July 26, 1948.

33 Cf. order of the Postmaster General, "Procedure relative to

fair employment practices”, The Postal Bulletin, Sept. 20, 1949.

20

property in many Texas cities. And in the United States Air

Force, which has large installations in Texas, integration

of the races has been effectively accomplished. For example,

at the Lackland Base at San Antonio, Texas, where some

26,000 Air Force personnel are stationed, the New York

Times reports:34

"All the recruits at vast Lackland Base here, the

largest in the whole Air Force, live, eat and study

as a body and the grouping together of Negro

and white personnel has not caused any incidents.

" 'The integration of the base was accomplished

with complete harmony,’ General Lawrence {M a

jor General Charles W . Lawrence, Commanding

General of the Indoctrination Division of the

Air Force Training Command} stated, 'Order

went through to completely end segregation

among trainees on a certain date and when that

date arrived the segregation ended. No un

pleasant incidents resulted, and the white boys

and the Negro boys in the training are getting

on well together.’ ”

Lackland Air Base is not an isolated example. At many mili

tary establishments throughout the state, the same condi

tions prevail.

Finally, religious groups are making great strides in in

tegration of religious activities of Negro and white Texans.

As an example of such strides, the Executive Secretary of

the Texas Methodist Student Movement, in a report ap

pended hereto,35 relates in detail the activities of over fifty

local campus groups in the field of interracial religious

activity. *

*4 New York Times, September 18, 1949, p. 53, Sec. L.

as Report of Rev. Paul Deats, Jr., Appendix H, p. 40, infra.

21

CONCLUSION

First-class citizenship for Negroes is an impossibility

until this Court recognizes that the rule of Plessy v. Fergu

son is an anachronism which cannot stand before the Four

teenth Amendment.

Despite the facts that the rule of that case has necessarily

magnified the social inertia and the prejudice which is the

patrim ony of many white Texans, and that under the rule

of that case normal and natural associations of free peoples

have been declared unlawful, great strides in racial integra

tion are now evident.

The social patterns in Texas and the South today are a

far cry from the conditions which brought forth Plessy i .

Fergustm. Now, cot only have social scientists scotched the

—vhi of white supremacy, but Texans in everyday contacts

recDsmze ~ar the Negro is entitled to a place of dignity in

a e v e r —a - If cte Constitution does not, as Mr. Justice

M trrcv st-tgescsi _c his concurring opinion in O w * . t

CaerT/KBsk.3* ' render irrational as a justification for dis-

crimtaaDon those factors which reflect racial animosity,"

the social scientist and the daily experiences of Texans have

done so.

W e are confident that this Court will consider the "rea

sonableness” of the exercise of Texas’ police power in the

light of current economic and sociological conditions.36 37

36 332 US 633 at 663.

37 Cf. West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, 300 US 379.

22

There appearing no reasonable basis for enforced segre

gation on the basis of race at the graduate school level; and

to the contrary, it appearing that such segregation deprives

Negroes of basic rights guaranteed by the Constitution, we

petitioner’s right to full and unsegregated educational op

portunity should be reversed. The record in this case, the

judgment of social scientists, and the daily experience of

Texans make it quite apparent that Texans are prepared

for such a decision.

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

M ullinax , W ells and B all

of Counsel,

1716 Jackson Street

Dallas, Texas

February 17, 1950

respectfully submit that the Texas Court’s denial of the

28

APPENDIX A

List of State-Wide Affiliates of the Texas Council of

Negro Organizations

Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Texas.

Baptist Ministers Conference of the B. M. & E. Conven

tion.

Baptist Missionary and Educational Convention of Texas.

Colored Teachers State Association of Texas.

Democratic Progressive Voters League of Texas.

Free and Accepted Masons of Texas.

Gulf State Dental Association.

Grand Court Order of Calanthe, Jurisdiction of Texas.

Grand Lodge, Knights of Pythias, Jurisdiction of Texas.

Heroines of Jericho, Texas Jurisdiction.

Independent Funeral Directors Association of Texas.

Lacy Kirk Williams Ministers’ Institute.

Lone Star Medical Association.

National Boule, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority (Texas Ju

risdiction) .

National Council, Knights of Peter Claver (Texas Jurisdic

tion).

Negro Agricultural Workers’ Association of Texas.

Order of the Eastern Star (Free and Accepted Masons of

Texas).

Southwest Bar Association, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Ar

kansas and Louisiana, (Texas Jurisdiction).

Southwestern Athletic Conference.

State Beauticians Association of Texas.

State Congress of Parent-Teachers Association of Texas.

State Sunday School and B. T. U. Congress, B. M. & E.

Convention of Texas.

Texas Baptist State Sunday School and B. T. U. Congress,

Texas Baptist Convention.

25

Texas Association of Colored Graduate Nurses.

Texas Baptist Convention.

Texas Baptist State Ministers’ Institute.

Texas Commission on Democracy in Education.

Texas Commission on Participation of Negroes in Local,

State and Federal Agencies.

Texas Conference of NAACP Branches of Texas.

Texas Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs.

Texas Federation of Colored Girls.

Texas Negro Barbers Association.

Texas Negro Burial Association.

Texas Negro Chamber of Commerce.

Texas Negro Press Association.

Texas State Association, IBPOE.

Texas State Congress of Federated Civic and Social Clubs.

Texas Youth Conference, NAACP.

Texas Veterans Counsellors-Coordinators Association.

The Insurance Association of Texas.

The Texas Church Ushers Convention.

Women’s Auxiliary, B. M. & E. Convention of Texas.

Women’s Auxiliary, Gulf State Dental Association.

Women’s Auxiliary, Lone Star Medical Association.

Women’s Auxiliary, Texas Baptist Convention.

26

APPENDIX B

Consent of Petitioner for Filing

Amicus Curiae Brief

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NO. 667

The undersigned, as counsel for the Petitioner herein,

does hereby give this written consent to the Texas Council

of Negro Organizations, to file a brief as amicus curiae

in the above numbered and entitled cause, in accordance

with Rule 27, subdivision 9, of the rules of this court.

Consent for Filing

Amicus Curiae Brief

/s / W. J. Durham

W. J. Durham

Counsel for Petitioner

27

APPENDIX C

STATE OF TEXAS \

COUNTY OF GALVESTON \ AFFIDAVIT

I am Herman A. Barnett, a Negro from Lockhart, Texas,

I am now a medical student at the University of Texas

Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas. Even though I am

the only Negro student enrolled in this medical school,

I have had no unpleasant experiences during any of my

contacts with either the other students or the faculty.

From the very first day I was accepted as just another

student. I met most of the members of the freshman class

during the first day of orientation. Also on the first day,

several of the students invited me to work with them as

a laboratory partner, and one of the upper classmen invited

me out to his home to participate with several other fresh

men in a study group which he was leading.

Because of the way in which I have been received by the

personnel of the University of Texas Medical School, I

am able to devote all my time and energy to the study of

medicine without any fear of ill-will or rebuke.

/s/ Herman A. B arnett

Sworn to and subscribed before me this 14th day of Feb

ruary. 1950. in the city of Galveston, Texas.

/s Thomas D. Armstrong

T homas D. Armstrong

Notary Public in and for

Galveston County. Texas

Report of the First Negro Student to Enter the

Medical School, University of Texas

28

APPENDIX D

STATE OF OKLAHOMA )

COUNTY OF GRADY $ AFFIDAVIT

My name is Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher. I was the plaintiff

in the Sipuel v. Oklahoma University case, and am now a

student in the School of Law at the University of Okla

homa.

After the Oklahoma Legislature passed a law allowing

Negroes to attend, on a segregated basis, certain Oklahoma

institutions of higher learning, about 50 other Negro stu

dents and I entered the University at Norman in June, 1949.

I was the only one to enroll in the law school.

In spite of the provisions in the state statutes that we

be provided separate classrooms and instructors, I attended

classes with all the other entering freshmen. The semblance

of segregation was maintained by "Reserved for Colored”

signs placed beside my desk. These signs did not keep my

classmates from coming back to talk with me and exchang

ing class notes. Gradually, the students took down the signs.

From the first, my classmates were friendly. Now I am

accepted as any other member of the class.

The only source of embarrassment, both to me and my

classmates, has been the requirement of segregation. In

spite of this requirement, however, we study together in

the library, and on the lawn under the trees, have "bull

sessions” in the halls and on the steps of the law school,

and use the same drinking fountains and rest rooms. There

Report of First Negro Student to Enter the

Law School, University of Oklahoma

29

is no segregation whatever in our class meetings and activi

ties. This fall the summer freshmen endeavored to get me

elected as class treasurer, but the fall freshmen outnum

bered us and took all the class offices. I lost by about 10

votes.

The other Negro students and I eat in the Union "Jug”

at a table reserved for us at the back. All during the day,

other students either sit at our table or pull their tables near

ours in order that we can talk while having coffee.

Not only am I accepted in the School of Law, but I have

been treated very kindly by white families in Norman wrho

have invited other Negro students and me to their homes

for dinner.

I am happy finally to be enrolled in the State Univer

sity, both because it is a good school and because it is

located near my home, consequently less expensive for me

to attend.

Ada Lois S ipu el Fish er

Sworn to and subscribed before me this 17th day o f Feb

ruary. 1950. in the city of Chickasha. Oklahoma.

Oklahoma.

Bertha C Fletcher

Notary Public

30

APPENDIX E

TO WHOM IT M AY CONCERN:

Being the first Negro student admitted to the School of

Medicine of Arkansas University, the other students seem

to have gone out of their way to make me feel that I am

welcomed. On the very first day, September 27, 1948, all

three of the white girls and about a third of the white boys

who also were entering as freshmen, made it a special point

to meet me. I remember the seating arrangement at our

very first class: one of the white boys was sitting to my

left, and one of the girls to my right. From then on, I

have had no fear that the students would resent my pres

ence.

Here at the Medical School, we have had no problem

with the matter of segregation, like my friend, Jackie Shrop

shire, had when he entered the Law School at the University

in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Here there was no attempt to

"fence in” my desk, as they did his for the first few days,

before his fellow students tore down the railing.

Since we do not have any study halls in the Medical

School, we usually study in each other’s apartments. The

three other girls, all residents of Arkansas, have become

very close friends of mine. Several of the fellows and I

often during the day go to one of the girl’s apartment near

the school to discuss and study our lessons. About every

other evening, after classes, (wo of the girls and I go by

the grocery store, and take food to my apartment or to

Report of First Negro Student to Enter the

Medical School, University of Arkansas

*t I • t I

one of theirs, where we prepare our evening meal before

studying together late into the night.

At noon, those of us who take our lunches eat together

in one of the rooms at the school. Oftentimes, after classes,

I go with several of the students to "drive-in” cafes to eat.

I have met so many fine people, here in Little Rock and

at the Merical School, that I have been having a good time.

Not a single person has been unkind to me.

/ s / Edith M. Irby

Edith M. Irby

Subscribed and sworn to before me, in the City of Little

Rock, Arkansas, on February 10, 1950.

{Seal}

/s / Anna J ean Jones

Notary Public

32

APPENDIX F

Excerpt from the Journal of Negro Education

Vol. X IX , No. 1, Page 4, Winter, 1950

EDITORIAL COMMENT

SOME PROGRESS IN THE ELIMINATION OF

DISCRIMINATION IN HIGHER EDUCATION

IN THE UNITED STATES

Elimination of Secregation at the University Level

in the South

Probably the most encouraging step which has been taken

in this area has been the admission of Negroes to several

Southern state-supported graduate and professional schools

which hitherto excluded them because of their race. And

what is more important, there has not been reported a

single untoward incident of any kind as a result of the

change. Prior to the school year 1947-48, only two state-

supported universities in the South had admitted a Negro

student for more than 50 years. The law school of the

University of Maryland admitted a Negro student in 1935,

and around ten years ago the State University of West

Virginia began to admit Negro students to its graduate

and professional curricula. In each case the experiment

proved successful beyond anyone’s expectations, and Ne

groes have since become a normal part of the student popu

lation.

More recently, state-suported universities in five Southern

states have admitted Negroes to various schools and col

leges. (1) The University of Arkansas in 1947-48 admitted

a Negro to its law school on a segregated basis. The next

38

year the University admitted a Negro girl to its medical

school on a non-segregated basis, and eliminated the seg

regation initially imposed in the law school. (2) The Uni

versity of Delaware announced in 1948 that it had revised

its policies so as to permit the admission of Negro students

to any curricula available at the University which were not

available at the Negro college at Dover. A dozen or more

Negroes attended the University last summer and several

are at present enrolled. (3) The University of Oklahoma,

under a directive of the Board of Regents, admitted a Ne

gro student on a segregated basis to its graduate school in

1948. A little later Negro students were enrolled in some

of the professional schools on a non-segregated basis. (The

case of the student admitted on a segregated basis is now

before the U. S. Supreme Court to determine the consti

tutional validity of the practice.)7 (4) The University of

Kentucky admitted Negro students to its graduate school

last year for the first time, enrolled a sizeable number in

its summer session, and has several enrolled at the present

time. (5) The University of Texas this year admitted a

Negro to its medical school courses at Galveston, but re

quired him to register as a student in the Texas State Uni

versity for Negroes in Houston.

The instances cited here all involve state-supported uni

versities in the South which hitherto had excluded Negroes.

In all, state universities in some seven Southern and border

states now admit Negro students to various schools and

colleges within their university organizations. It might be

noted in passing that some of the privately-controlled uni

versities and colleges in Missouri, North Carolina, Virginia

7 See: McLaurin v. Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, et al.

34

and the District of Columbia also admit Negroes; thus

increasing the number of states in this category to ten and

the District of Columbia. In addition to the fact that the

number of such instances is increasing, the important point

to be noted here is not why these institutions have changed

their admission policies and practices, but rather that, hav

ing changed them, none of the dire predictions which were

made before-hand has materialized. As a professor at the

University of Kentucky observed:8 "University of Kentucky

tried Plan A this summer. Worked out O.K. as far as I

learned. The sky did not fall, neither did any of the build

ings fall down, nor did any of the students get contami

nated.”

Speaking of the attitudes of professors in Southern uni

versities and colleges, attention is called to a poll which

has just been completed by the Southern Conference Edu

cational Fund and printed in this number of the Journal.9

More than two-thirds (68% ) of the teachers in state and

privately supported white higher institutions in the South

favor the immediate abolition of segregation on the gradu

ate and professional level. And, I might add, that the atti

tudes of white students in these institutions are even more

favorable.

* * aee-rivr. / •/. •»* c-.rzs.r x i <A the Journal.

APPENDIX G

NEGRO ATTACK ON SEGREGATION

By Allen Duckworth

Last year, in speaking to Negro graduates of the new

state university at Houston, the late Beauford H. Jester

said:

"Heaven is not reached in a single bound.”

Yet, as far as the Texas Negro may be from Heaven, he

has taken some long bounds in the last six years. These

bounds have been longer than the average Negro, or the

average white, probably realizes.

The effort of the Texas Negro to break down segrega

tion can be divided into three phases— political equality,

educational equality and social equality.

Strong support bv legal talent from the East, especially

through the National Association for Advancement of Col

ored People, is behind the 5-pronged campaign.

One victor' already is w on. That is on the political front.

Until 1944, the Negro in the South was classed with

Republican politics. It w as Abraham Lincoln, the Republi

can, who gave the Negro his freedom. By tradition, the

Democratic party of the South was the party of the w-hite

man. And the Democratic primary elections were limited

to whites.

Article Printed in The Dallas Morning News

February 2, 1950

36

The United States Supreme Court, controlled by Roose

velt appointees, ruled in 1944 that Negroes must be ad

mitted to Democratic primaries. That reversed the Negro

political fealty in Dixie. For he was not unappreciative

of what the Democratic party under Roosevelt was doing.

Had not the Democratic party done what the Republicans

had merely talked about? This appreciation was evident

shortly after the Supreme Court ruling. Dallas Negroes

raised money for the Roosevelt-Truman Texas campaign.

Today, Negroes not only vote in Texas Democratic

primaries; they also participate in precinct, county and

state conventions. They sit with whites. Segregation has

been wiped out at Democratic conventions. Conservative

delegates from Dallas and several other counties were

kicked out of the convention at Fort Worth in September,

1948. As the conservatives walked out, they saw dozens

of Negroes filing in to take the seats they had just vacated.

The Negro had come a long way. It couldn’t have happened

four years before.

Two years after the Negro won political equality, he

turned to educational equality.

Heman Marion Sweatt entered as the main figure on that

scene. Sweatt wanted to enroll in the University of Texas

law school. When denied that right. Sweatt sued.

D ucact Jm t Moy G A xthef o f Austin held that the State

of Texai ~ ( ! ) p iov;de separate but equal ‘A -/t‘ionai

rp p T iM itirt nr (T) urotov

set for v'tutet

. ® v.*«- - y *-,/} ettabl.-

* jecar.sz.-t :v ‘ Homton Tf><- miHM

sity is now a going concern, with more than 2,000 Negroes

studying there.

In order to meet requirements for Sweatt, the university

set up a temporary and separate law school near the Capitol

grounds in Austin.

Sweatt did not enroll at either the Houston university'

nor at the branch law school at Austin.

His reason became obvious in later trials and appeals

of his lawsuit.

Atty. Gen. Price Daniel attempted to show in the court

room ihar it was not the purpose of Sweatt and his attor

neys (from the National Association for Advancement of

Colored People) to get Sweatt an education alone. They

wanted Sweatt in a white university. Daniel argued. The

Daniel atcurrent was u rce ii in Swean's own testimony.

said tie w o d d r e t errer a separate school for

\ t g i m . com Anagh it m p r tie adjudged equal to the

— - Uk v h w t of Texas law school.

T don't tie_eve m segregation." Sweatt said.

Ttie N e t t : irttgatioc or. education is tied closely to the

third tdase : : toe XAACP campaign— the drive for soda:

ecuahr*. as witness Sweatt'> own statement on segregation.

latest on the inrlsegiegation suits involves not politics,

rot education, hut recreation. Negroes now are demanding

ecrau fjk-.htirs a: state parks. The legal argument of the

Negroes > re .vg ' red b\ the State Parks Board. The hoard

SS

has ordered state parks closed this year unless means can

be found to accommodate Negroes.

Just how a state park could give Negroes "equal” accom

modations is a puzzle. For instance, along the Frio River

in Garner State Park, whites now camp, swim and fish.

A Negro could argue that it would not be "equal” for him

to camp upstream. No matter where you put the Negro

in Garner Park, he could claim that he did not an equal

view of the mountains, or of the river, nor did he have

the same access to the recreation centers, such as the dance

terrace.

Negroes also are shooting for equality on the municipal

golf links at Houston. They want equal rights in golfing.

The NAACP lawyers follow a smart path. They believe

they can make segregation too expensive. By potshotting

on specialized schools, they are bringing the cost of segre

gation to the front. For instance, if they decide to demand

enrollment of a single Negro for a course in mining, the

University of Texas might have to admit that Negro at

the El Paso branch or build an entirely separate plant for

him. In order to set up a segregated mining school, the

Negro lawyers estimate, the university would have to spend

S5J0OO.OOO. And that’s a lot of dollars for one student.

The Supreme Court of the United States is due to hear

S-*ezrt case arguments in a few days. The NAACP is bank-

:r_g or. tbtt dec;t:or.. h h the key to their fight against

ve§pegpt>:x. of fc'.y 'end ;r. Texas awl the South.

Here a the statement of the NAACP itself: "When and

if the Sweatt case h won, from that moment on segregation

will begin to crumble/’

39

APPENDIX H

TEXAS METHODIST STUDENT MOVEMENT

2403 Guadalupe Street

Austin, Texas

February 12, 1950

Report on Interracial A cthities

The Texas Methodist Student Movement, with contacts

in over fifty local campus groups, has been interested in

interracial work for several years. This is partly due to a

real concern e c the part of white students and leaders for

the cdhgrocs welfare of students in Negro colleges. It is

also a tescvTGse :o the actkwi of the last General Conference

o' The V-otoecLts: Church, calling on Methodists to work

.vv»a.-h :m ; ...-o.o,ar.oo of segregation in their church meet

ings.

This work has been most evident in the annual Thanks-

C ' ng Conferences held by the movement, beginning in

Denton in 1944, when one of the leaders was a Negro

minister and educator. In 1945 the conference was held

in Corsicana, again with one Negro speaker and this time

with four or five Negro students attending sessions and

eating with the white students. Since this time, provisions

have been made for each conference to be held interra-

cially; however, no Negro delegates attended the 1946 con

ference at Hillsboro. The 1947 conference was held in Aus

tin, with over twenty Negro delegates from two colleges

in attendance. Some students were housed interracially. all

delegates ate together in a public "white” cafeteria, and

sessions were held in the campus church. In 1948 one Negro

speaker and three Negro students attended the conference

40

in College Station. The 1949 conference, held in Mineral

Wells, included fourteen Negro students and faculty mem

bers, plus an outstanding Negro speaker. This conference

was fed in a public dining room.

There have been several smaller institutes (week-end

training schools) held in the last few years on an inter

racial basis. Students have indicated their interest in hold

ing interracial conferences by setting aside §150 of their

state benevolent budget of §2200 to help with expenses

of Negro delegates.

The South Central Regional Leadership Training Con

ference for Methodist students has been held for several

years on an interracial basis; it has been invited to hold

its Tune. 1950, session in Dallas on the same basis.

Tor at least a decade in Austin there has been a coopera

tive provrHtr involving students from Samuel Houston and

Tilionoo fNegro Colleges) and from the University of

Text* "Y and church groups. Events have included the

errta.' R aa Reisskua Sunday observance (often with an

in errah ii rhncr . supper and evening meetings for dis

tinguished Negro and white visitors, and leadership pro

jects. The Presbyterian student group at the University of

Texas organized and met with a similar group at Tillotson.

Negro students and townspeople have been welcomed at

white church services and concerts for a number of years.

/s/ Paul D eats, J r,

Executive Secretary

41