Clark v. Boynton Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. Boynton Brief for Appellees, 1966. 6c9ea096-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bc8afe4d-1f5d-41af-bc58-35f1dd3e373e/clark-v-boynton-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

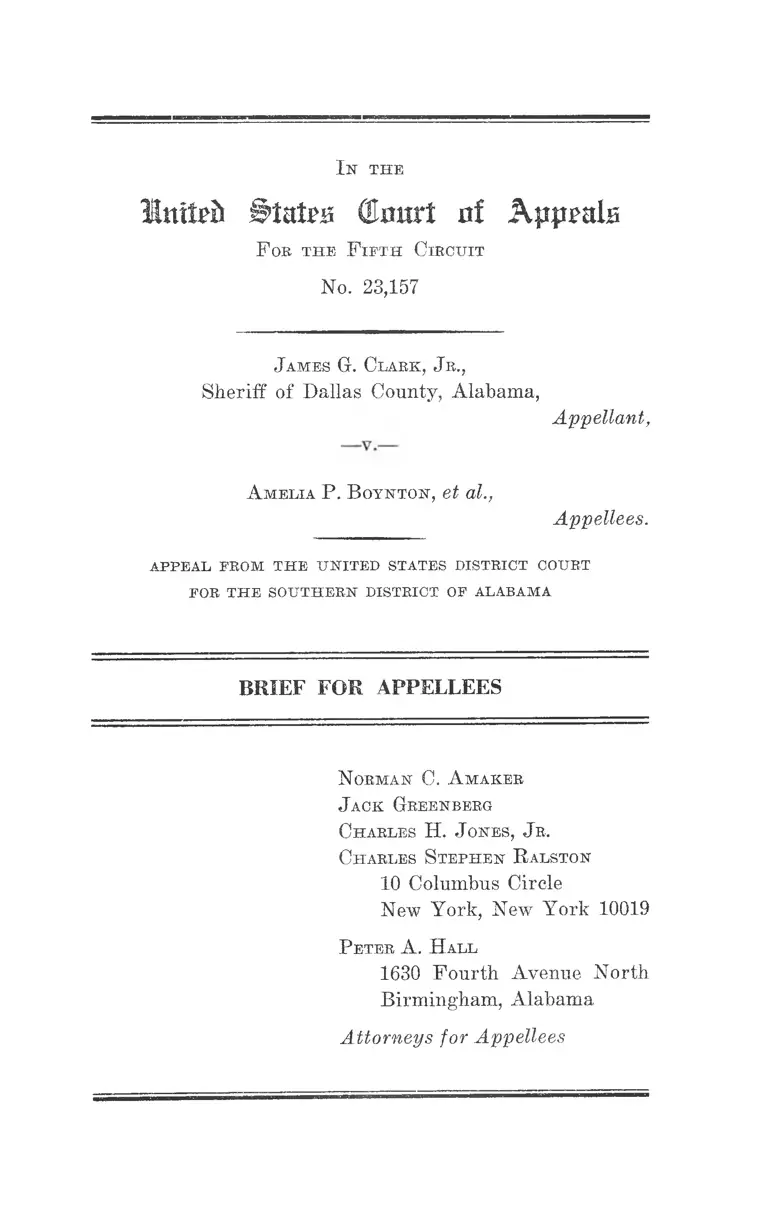

I n the

United i>taten (Emtrt of Appeals

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 23,157

J ames G. Clark, J r.,

Sheriff of Dallas County, Alabama,

Appellant,

A melia P. B oynton, et al.,

Appellees.

A P P E A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IST R IC T COU RT

FO R T H E S O U T H E R N D IS T R IC T O F ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

N orman C. A maker

J ack Greenberg

Charles H . J ones, J r .

Charles S tephen R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Appellees

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ................. ................................ 1

A rgument—

I. The Order of the District Court Was Sufficiently

Specific to Support the Contempt Citation ..... 11

II. The District Court Had the Power to Punish

Appellant for Contempt of Court Without Sub

mitting the Issues to a Jury ...............— ....... 13

A. There is no constitutional right to trial by

jury in criminal contempt cases ........... ...... 14

B. The Federal statutes giving the right to trial

by jury in criminal contempt cases are not

applicable to the present case ..................... 15

Conclusion .................................................................................. 20

Table of Cases

Alabama v. Allen, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3385-64, 10 R.

Eel. L.Rep. 234 (1965) ....... ........... ...... ................... 2

Alabama v. Boynton, S.D. Ala. C.A. No. 3560-65 (1965) 2

Bevel v. Mallory, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3714-65 (1965) .... 2

Brown v. United States, 359 U.S. 41 (1959) ..... ........ 14

Cooper v. Alabama, 353 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) .... . 2

Dallas County v. Student Non-Violent Coordinating

Committee, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3388-64, 10 R.Rel.

L.Rep. 234 (1965) 2

11

PAGE

King v. Baker, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3572-65 (1965) ...... 2

Lewis v. Clark, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3386-64 (1964) __ 2

McCann v. New York Stock Exchange, 80 F.2d 211

(2nd Cir. 1935) ........................... ....................... ...... 13

Moore v. United States, 150 F.2d 323 (10th Cir. 1945) 14

Rapp v. United States, 146 F.2d 548 (9th Cir. 1944) .... 14

United States v. Atkins, 210 F.Supp. 441, rev’d, 323

F.2d 733 (5th Cir. 1963) see also, 10 R.Rel. L.Rep.

209 (1965) ........... .................. ................ .................. 2

United States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. 681 (1964) ...... 14,18-19

United States v. Clark, 10 R.Rel. L.Rep. 236 (S.D.

Ala., C.A. No. 3438-64, 1965) ___________ ......2, 3, 4, 8

United States v. Dallas Comity, S.D. Ala., C.A. No.

3064-63 (1963) .......................... ................. .............. . 2

United States v. McLeod, C.A. No. 3188-63 (1963) .... 2

Williams v. Wallace, 240 F.Supp. 100 (M.D. Ala.

1965) .......................... ................................................. 2, 3

Federal Statutes-.

18 U.S.C. §401 ....... ......

18 U.S.C. §402 ............

18 U.S.C. §3691 .............

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) ........

28 U.S.C. §1343(4) ..... .

42 U.S.C. §1971 (a) ___

42 U.S.C. §1971(b) .......

42 U.S.C. §1971 (c) ........

42 U.S.C. §§1975-1975(e)

42 U.S.C. §1981 ..............

.............. ..15,18

... .............. 19

................ 19

............... ...3,15

..................3,15

...4,16,17,18,19

...4,16,17,18,19

15,16,17,18,19

............. 15

......... ........ 3

PAGE

iii

42 U.S.C. §1983 .......................... ....................... 3,15,17,19

42 U.S.C. §1995 .................... ......................11,15,16,18,19

Civil Eights Act of 1957, Public Law 85-315 (71 Stat.

638) ...... ■............... ...... ....................................... .15,16,19

Fed. E. Civ. Proc., Rules 18, 20, 23 .......................... . 3

Fed. E. Civ. Proc., Rule 65 ....................................... . 12

Other Authorities:

7 Moore, Fed. Practice, 1636-40 ........... .......... .......... 12

103 Cong. Rec. 8471, 8472-73 (6/6/57) (85th Cong. 1st

Sess.) (Remarks of Sen. Ervin) ....... .................... 17

103 Cong. Rec. 8468 (6/6/57) (85th Cong., 1st Sess.)

(Remarks of Sen. Robertson) ......................... ........ 17

103 Cong. Rec. 9187 (6/14/57) (85th Cong., 1st Sess.)

(Remarks of Rept. Keeney) ................... ................16-17

I s r t h e

Intfrft Btdtm (Eourt at A p p a ls

F ob the F ieth Cibcuit

No. 23,157

J ames G. Clark, J r.,

Sheriff of Dallas Comity, Alabama,

Appellant,

—v.—

A melia P. B oynton, et al.,

Appellees.

A P P E A L PR O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IS T R IC T COU RT

FO R T H E S O U T H E R N D IS T R IC T OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement of the Case

Appellees make the following additions to the statement

of the case by appellant, directed to those particulars

that the appellees believe should be brought to the atten

tion of the court.

The present case is but one of a number arising out

of the occurrences in Selma, Alabama, from 1963 through

1965. During this period efforts were made by Negro

citizens of Selma to register and vote and to achieve

equality of political and social rights with white residents.

Their efforts were aided by other citizens concerned with

the equal rights of citizens and were supported by litiga-

2

tion brought by themselves and by the United States

Government.1 It was demonstrated in much of this litiga

tion that the opposition to the achievement of equal voting-

rights by Negro citizens was led by the appellant, James

G. Clark, Jr., the sheriff of Dallas County. See the findings

of fact in United States v. Clark, 10 R.Rel, L.Rep. 236

(S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3438-64,1965), and Williams v. Wallace,

240 F.Supp. 100, 103-05 (M.D. Ala. 1965).2

1 Affirmative suits brought by private citizens in addition to the present

one included: Lewis v. Clark, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3386-64 (1964); Wil

liams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M.D. Ala. 1965) ; King v. Baker,

S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3572-65 (1965); Bevel v. Mallory, S.D. Ala., C.A.

No. 3714-65.

In addition, various criminal prosecutions and civil injunctions brought

by Dallas County and Selma officials were removed to the Federal Court:

Alabama v. Allen, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3385-64, 10 R.Rel. L.Rep. 234

(1965); Alabama v. Boynton, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3560-65; Cooper v.

Alabama, 353 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965); Dallas County v. Student Non-

Violent Coordinating Committee, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3388-64, 10 R.Rel.

L.Rep. 234 (1965).

The following suits were filed by the Federal Government: United

States v. Atkins, 210 F. Supp. 441, rev’d, 323 F.2d 733 (5th Cir. 1963),

see also, 10 R.Rel. L.Rep. 209 (1965); United States v. Clark, S.D. Ala.,

C.A. No. 3438-64, 10 R.Rel. L.Rep. 236 (1965); United States v. Dallas

County, S.D. Ala., C.A. No. 3064-63; United States v. McLeod, C.A.

No. 3188-63 (1963).

2 In his findings of fact, Judge Johnson, of the Middle District of

Alabama, stated:

The evidence in this case reflects that, particularly as to Selma,

Dallas County, Alabama, an almost continuous pattern of conduct

has existed on the part of defendant Sheriff Clark, his deputies, and

his auxiliary deputies known as “possemen” of harassment, intimida

tion, coercion, threatening conduct, and, sometimes, brutal mistreat

ment toward these plaintiffs and other members of their class who

were engaged in their demonstrations for the purpose of encouraging

Negroes to attempt to register to vote and to protest discriminatory

voter registration practices in Alabama. This harassment, intimida

tion and brutal treatment has ranged from mass arrests without just

cause to forced marches for several miles into the countryside, with

the sheriff’s deputies and members of his posse herding the Negro

demonstrators at a rapid pace through the use of electrical shocking

devices (designed for use on cattle) and night sticks to prod them

along. 240 F. Supp. at 104.

3

The present action was begun by appellee Amelia P.

Boynton, a Selma Negro businesswoman and official of the

Dallas County Voters’ League, a local organization of

Selma residents which spearheaded the drive to achieve

voting and other civil rights for Negroes in Dallas County,3

and others because of actions taken by appellant designed

to intimidate and harass Negro citizens seeking to register

to vote (E. 1-7). The action was brought on behalf of

three classes of plaintiffs.4 The first class consisted of,

“Negro citizens of the United States who are residents of

the State of Alabama, Dallas County, who are entitled to

vote and who have been arrested, . . . harassed, [and]

intimidated, . . . in their attempt to register to vote”

(E. 2). The second class was Negro citizens of the United

States and residents of Dallas County who sought to vouch

for persons seeking to register to vote in accordance with

the then prevailing Alabama law, and who had been simi

larly harassed (E. 2).

The third class consisted of, “Citizens of the United

States who have been similarly arrested, prosecuted,

harassed, intimidated, threatened and coerced in their

attempt to exercise their rights of freedom of speech and

assembly designed to persuade voting registrars in Dallas

County, Alabama to comply with the Constitution and laws

of the United States guaranteeing the right to vote to all

citizens” (E. 2-3).

Jurisdiction was based on 28 U.S.C. §§1343(3) and (4).

The basic cause of action asserted was that established by

42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983, since appellees were seeking

the redress of the deprivation of the rights to register to

3 See findings of fact in United States v. Clark, 10 R.Rel. L.Rep. 236,

237, and Williams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100, 103.

4 The joinder of claims and parties and the bringing of the suit as a

class action were authorized under Fed. R. Civ. Proe., Rules 18, 20, and 23.

4

vote and to vote as guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution and 42 U.S.C. §§1971(a) and (b),

and the right to freedom of speech and assembly as guar

anteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution of the United States. Injunctive relief was

sought on behalf of the three classes of plaintiffs against

appellant Clark and other named defendants to enjoin

them from continuing their harassment and intimidation

of the plaintiffs in the exercise of the rights urged respec

tively by the members of the three classes.

The complaint was filed on Januray 22, 1965 (R. 36),

together with motions for a temporary restraining order

(R. 34) and for preliminary injunction (R. 44). Both mo

tions requested that defendants be restrained from further

interfering with and harassing the plaintiffs in the exercise

of their constitutionally protected rights (R. 35, 44). An

affidavit in support of the allegations of the complaint and

in support of the two motions were filed with the complaint

(R. 7-11). The day before the suit was filed, telegrams

were sent to each of the named defendants notifying them

that the attorneys for the plaintiffs would appear before

the District Court to seek a temporary restraining order

(R. 31-34). Attorneys for the defendants appeared at that

hearing and submitted counter-affidavits to the court (R.

37).

On the morning of January 23, 1965, the District Judge

issued his order, designated a temporary restraining order,

making findings of fact based on the affidavits and counter

affidavits submitted to him and also on the testimony

heard by him in a prior hearing in United States v. Jam.es

G. Clark, Jr., supra (R. 37). Testimony had been pre

sented in that case for more than six days, ending on

December 22, 1964, and concerned many of the same issues

raised in the present case (Ibid.). The Judge also relied on

5

“matters of public record and common knowledge” (Ibid.).

On the basis of its findings, the Court issued its order

protecting all three classes of plaintiffs; as to the third

class in particular the Court ordered that:

Those interested in encouraging others to register

to vote have the right peaceably to assemble outside

the court house, but shall not do so in such a way as

to interfere with lawful business expected to be trans

acted in the court house. Such persons also have a right

to peaceably assemble without molestation, and will

be permitted to do so; but violence, either by those

so assembled or officers entitled to surveillance over

such assemblages, or on the part of outsiders, will not

be tolerated at such assemblage.

Not only are such assemblages entitled to occur,

but those so assembled are entitled to have lawful

protection in such assemblage.

This order in no wise is intended to interfere with

the legal enforcement of the laws of the State of Ala

bama, Dallas County, or the City of Selma. But under

the guise of enforcement there shall be no intimidation,

harassment or the like, of the citizens of Dallas County

legitimately attempting to register to vote, nor of

those legally attempting to aid others in registering

to vote or encouraging them to register to vote (ft.

40-41).

Subsequently, on January 27, 1965, the plaintiffs moved

for additional relief and for an order to show cause against

appellant because of further activities of the appellant in

alleged violation of the court’s order (It. 46-58). Again,

this motion was supported by sworn affidavits (ft. 58-76).

On January 30, 1965, the District Court amended its Order

of January 23, 1965, to clarify the question of how many

6

persons could remain in line for registration (R. 97). That

order again protected the rights of persons who wished

to encourage others to register to vote to assemble peace

ably at the courthouse {ibid.). Subsequently, the defend

ants moved to dismiss the complaint (R. 99-104).

On February 11, 1965, plaintiffs filed a motion supple

mental to their motion for additional relief and order to

show cause (R. 104-107). This motion alleged the events

of February 10, 1965, which formed the basis of the con

tempt judgment herein appealed. Briefly, the allegations

were that on February 10, a group of Negro children and

teenagers peacefully assembled before the Dallas County

Courthouse carrying signs urging full and equal voting

rights for Negroes (R. 105). Appellant Clark, exercising

his authority as sheriff and with a group of 15 to 20 of his

deputies, surrounded the teenagers and led them through

the streets of Selma {ibid.). They forced the demonstrators

to take a march of nearly 2% miles out into the country at

a fast pace, walking and running (R. 104-105). It was

alleged that:

The action of the sheriff in this [sic] arresting, harass

ing and intimidating members of the class protected

by the order of this court, places him and his subordi

nates in willful and open contempt of this court’s in

junctive order of January 23, 1965, as modified on

January 30, 1965 (R. 106).

The court was asked to find appellant in contempt of its

order and punish him by fine or imprisonment, or both

(R. 107).

The motion was supported by sworn affidavits (R. 107-

112). The appellant opposed the motion on the grounds

that its allegations were untrue and that the office of the

defendant as sheriff of Dallas County insulated him from

7

interference by the federal courts in the performance of

his duty (R. 113). On March 25, 1965, the District Court,

in response to the motion for further relief, ordered:

That the defendant, James G. Clark, Jr., Sheriff of

Dallas County, Alabama, immediately appear before

this court on April 26, 1965, at 9:30 o’clock a.m., in

Selma, Alabama, and show cause why he should not

be held in contempt of this court and punished there

fore by fine or imprisonment, or both (E. 115).

On April 2, 1965, defendants petitioned the court, on the

basis of allegations concerning allegedly improper con

duct of plaintiffs and members of their classes, to:

issue a supplemental decree or order amending the

previous temporary restraining order and amendments

thereto by setting forth specifically what [plaintiffs]

may not do in order that the law enforcement officials

of the City of Selma and Dallas County, Alabama,

can have better knowledge of what they are charged

with enforcing and what acts of the Complainants

they are enjoined from enforcing (R. 121).

Further amendments to the order of January 23, as

amended on January 30, were asked for by the defendants

(R. 122). On the same day, April 2, 1965, in response to

this petition, the District Court issued an order further

amending its order of January 23, 1965, as amended Janu

ary 30,1965, restricting the areas in Selma in which demon

strations could take place (R. 127-29).

A hearing was held on the order to show cause on April

26 and 27, and on May 17 and 18, 1965 (R. 153). Extensive

testimony was introduced as to the various incidents cited

in the motions for further relief and for order to show

cause which plaintiffs claimed constituted contempt of the

court’s order, but the court based its contempt finding only

on the incident of February 10, 1966 (R. 134-35).

The primary testimony on this incident was given by two

of the Negro students who participated in the demonstra

tions on that day. Miss Sallie Bett Rodgers testified that

she went to the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma at

about 2 o’clock in the afternoon “to encourage my parents

and other people that were residents of Dallas County, to

encourage them to register to vote” (R. 155). She testi

fied that approximately 200 persons stayed in front of the

courthouse for about 45 minutes (R. 155-56). A number of

people carried signs with such slogans as “Let my father

vote” (R. 155). At the end of the 45 minutes, Miss Rodgers

heard a voice giving an order of “Left Face” (R. 156). The

line then began to move down the street and children in

the group began to run {ibid.). During the run, which she

estimated as six or eight miles (R. 157), she saw one officer

beat a boy with a stick {ibid.). She testified that the age of

the boy was about 12 {ibid.). The group was made to run

out of the City of Selma into the country and Miss Rodgers

observed persons in the march fall out of line and lay beside

the road (R. 158). The officers conducting the inarch

traveled in automobiles and would change shifts so that

some would walk while others would ride (R. 159). Some

of the officers cursed at the marchers and cattle prods were

used to make the children continue moving {ibid.).5 Miss

Rodgers testified that the march ended when the students

ran into some houses a number of miles outside of Selma

(R. 166).

The second student to testify was Miss Letha Mae Stover.

She testified that she assembled at the courthouse with a

6 Cf. the court’s findings in United States v. Clark, 10 R.R.L.R. 236, 238:

“The four Negro students were arrested, and electric cattle prods were

used on at least one, and possibly two, of them by Sheriff Clark.”

9

sign stating “One man, one vote” (R. 171), and that while

on the forced march she was cattle prodded by one of the

officers about three times (R. 173-75). Finally she became

exhausted and dropped off beside the road (R. 175). One

of the officers punched her in the back with a billy club and

told her to get up and go on {ibid.). She replied that “he

would have to kill me, because I could not” {ibid.). She

stayed by the side of the road until a car came along and

took her back to Selma {ibid.).

Additional testimony about this incident was supplied by

Mr. Joseph M. Avignone, a special agent with the Federal

Bureau of Investigation. Mr. Avignone testified that he

observed appellant Clark at the courthouse on the occasion

of the student demonstration (R. 182-83). He also saw and

recognized sheriff’s deputies and members of the sheriff’s

posse (R. 185). During the forced march itself, Mr. Avig

none was in an automobile following and observing it

(R. 183, 185). He saw appellant Clark in an automobile

going along with the march and observed sheriff’s officers

using cattle prods on marchers (R. 185-86). He testified

that the length of the march was approximately two to two

and one-half miles out into the country (R. 186). Mr.

Avignone heard over his car radio two statements on the

sheriff’s office radio band, one saying that the children could

leave the line anytime they wanted to and the other tell

ing the deputies “not to use the prod so much” (R. 187).

In response to the testimony of these three witnesses the

attorney for appellant testified that the sheriff had asked

him whether it would be in violation of the judge’s injunc

tion to march the teenagers out on the edge of the town

and turn them loose (R. 192). He advised the appellant

that he thought it would not be in violation of the injunc

tion and it would be a good idea and “could relieve some

of their steam” (R. 193). The attorney was asked on cross-

10

examination whether the appellant asked him if it would

be a violation of the injunction to use cattle prods on the

children during the march. He testified that cattle prods

were not mentioned and that he had given no advice as to

that (R. 194).

On September 2, 1965, the District Judge issued his find

ings of fact and judgment on the contempt citation (R. 130).

He found that: (1) the plaintiffs stated that their purpose

in being at the courthouse was either to register to vote

or to encourage others to register to vote, and that these

purposes were protected by the Court’s order (R. 133-134);

(2) on February 10, 1965, the teenagers and children as

sembled at the courthouse with signs urging equal voting

rights for Negroes (ibid.); (3) the demonstrators were not

disorderly (ibid.); (4) the appellant took the group on a

forced march during which they were forced to run or walk

at a brisk pace for over four miles (ibid.); (5) during the

march members of the group were struck with cattle prods

(ibid.). The court found that this action in:

harassing, and intimidating members of the class pro

tected by the January 23, 1965, order of the court

places him in direct contempt of the following portion

of that order:

“This order in nowise is intended to interfere with

the legal enforcement of the laws of the State of

Alabama, Dallas County, or the City of Selma.

But under the guise of enforcement there shall be

no intimidation, harassment or the like, of the citi

zens of Dallas County legitimately attempting to

register to vote, nor of those legally attempting to

aid others in registering to vote or encouraging

them to register to vote.” (Emphasis added by the

Court) (R. 134-35).

11

The appellant was ordered to pay a fine in the amount of

$1,500 (R. 135).

Subsequently, on September 10,1965, the appellant moved

for a trial de novo and for a jury trial on the basis of 42

U.S.C. §1995 (R. 136-39). These motions were denied on

September 15, 1965 (R. 144), and notice of appeal was sub

sequently filed (R. 145).

A R G U M E N T

I.

T h e O rd e r o f th e D is tr ic t C o u rt W as Suffic ien tly

S pecific to S u p p o r t th e C o n te m p t C ita tion .

One of the errors specified by the appellant was that

“The Court’s Order of January 23, 1965, and the amend

ments thereto were couched in such loose language that

they were insufficient to support a contempt proceedings

(sic) against this Defendant-Appellant James Gf. Clark,

Jr.” (R. 146). The record, however, does not support this

contention. The order of the District Court clearly stated

that the members of the plaintiffs’ class “have a right to

peaceably assemble without molestation, and will be per

mitted to do so” (R. 41). Also it was stated that:

[U] rider the guise of enforcement there shall he no

intimidation, harassment or the like, of the citizens of

Dallas County . . . nor of those legally attempting to

aid others in registering to vote or encouraging them

to register to vote (ibid.).

Thus, appellant was enjoined from molesting, harassing or

intimidating members of the class of persons encouraging

others to register to vote. Clearly, the actions of the ap-

12

pellant in taking the school children on the forced march

could have been found, as the District Court did, to be

precisely such an harassment or intimidation as he had

been enjoined from perpetrating. Indeed, it would be hard

to conceive of any other purpose for the action. In addition,

the use of cattle prods and clubs to force the students to

continue at a run or brisk walk was the kind of violence

and molestation that the order was intended to protect

them against.6

6 Although the appellant has not raised the question, it is clear that the

order of the district court was in force on February 10, 1965, the day of

the actions complained of. The order was issued January 23rd and re

newed on January 30, 1965. I t was designated as a temporary restraining

order and, therefore, it could be said that it had expired under the terms

of Rule 65(b). There are two reasons, however, why there was no expira

tion. (1) Although the order was called a temporary restraining order,

it was, in reality, a preliminary injunction, since it was issued after a

hearing at which affidavits and counter affidavits were presented and at

which both parties were heard. See, 7 Moore, Fed. Practice, at 1636-40.

(2) Even considering the order as a temporary restraining order, Rule 65

states that a temporary restraining order:

shall expire by its terms within such time after entry, not to exceed

10 days, as the court fixes, unless within the time so fixed the order,

for good cause shown, is extended for a like period or unless the

party against whom the order is directed consents that it may he

extended for a longer period. (Emphasis added.)

Although the record does not show that the appellant expressly consented

to the order’s extension, it is clear that there was an implied consent and

that all parties considered the order to be fully in force during the entire

period here in question. Thus, on April 2, 1965, the appellant filed a peti

tion requesting an amendment to the order of January 23rd and the court,

on the same day, granted the motion in part and amended the order so as

to restrict the areas of Selma in which demonstrations could take place

(R. 117-123, 127-130).

13

II.

The District Court Had the Power to Punish Appellant

for Contempt of Court Without Submitting the Issues

to a Jury.

The major portion, of the appellant’s brief concerns it

self with demonstrating that the proceeding below was one

for criminal contempt. Appellees do not contest this. The

motion for order to show cause made by the appellees on

February 12, 1965, prayed:

That this court enter an order requiring defendants

to immediately appear before this court, not later than

February 15, 1965 and show cause why they, and each

of them, should not be held in contempt of this court

and punished therefore by fine and imprisonment, or

both (E. 106-07).

The order to show cause issued by the court on March

25, 1965, stated that the defendant should appear before the

court on April 26, 1965, and “show cause why he should

not be held in contempt of this court and punished therefore

by fine and imprisonment or both” (E. 115). Further, the

order of the court finding the appellant in contempt and

imposing a fine was punitive in nature, arising from ap

pellant’s past actions.

The fact that the contempt action was prosecuted by the

appellees rather than by the United States Attorney did

not alter its status as a criminal contempt proceeding.

Although ordinarily a criminal contempt proceeding is

brought by the federal authorities at the instance of the

court, it is possible for the private parties themselves to

prosecute such an action. See McCann v. New York Stock

Exchange, 80 F. 2d 211 (2nd Cir. 1935) per Learned

14

Hand, J. The only issue raised by such a proceeding is

whether a defendant had sufficient notice of the fact that

the proceeding was criminal in nature. Here, appellant re

ceived such notice from the appellees’ motion and the

court’s order to show cause. Also, the fact that appellant

had such notice is demonstrated by the fact that he has

contended at all points in the proceedings, both at trial and

here, that it was criminal in nature.

Appellees’ contention, therefore, is that although this

was an action for criminal contempt, the District Court,

sitting by itself, clearly had the power to punish the

appellant, and that the appellant did not have, either

under the Constitution or statutes of the United States, a

right to a trial by jury on the issues presented.

A. T h e re is n o co n stitu tio n a l r ig h t to tr ia l by ju r y in

crim in a l c o n te m p t cases.

The recent case of United States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. 681

(1964), established clearly that there is no constitutional

right to trial by jury for one charged with criminal con

tempt. The only question possibly left unanswered by that

case was that there might be some limitations on the punish

ment that could be imposed by a court sitting without a

jury. Assuming for the moment that the majority opin

ion in Barnett may be so interpreted, appellees contend

that the $1,500 fine imposed here was well within the

bounds of any such limitation. See, Brown v. United States,

359 U.S. 41, 52 (1959) (15 month imprisonment upheld) ;

Moore v. United States, 150 F. 2d 323 (10th Cir. 1945)

($5,000 fine upheld); Rapp v. United States, 146 F. 2d 548

(9th Cir. 1944) ($1,500 fine upheld).

The Barnett decision thus makes clear that the appellant

here may prevail only if the statutes of the United States

15

required the District Court to convene a jury. There is no

such statutory requirement; rather the district court was

acting within the scope of the general equity power con

ferred by 28 U.S.C. §1343, 42 U.S.C. §1983, and 18 U.S.C.

§401.

B. T h e F edera l s ta tu tes g iv in g th e r ig h t to tr ia l by ju r y in

crim in a l c o n te m p t cases are n o t applicable to th e p resen t

case.

Appellant’s main contention is that 42 U.S.C. §1995 gave

him the right to a trial de novo by jury on the criminal

contempt citation and that the court’s denial of his motion

for such a trial was, therefore, in error. However, it is

clear that 42 U.S.C. §1995 is not a statute of general ap

plication to all criminal contempt cases. Rather, it applies

only to cases brought by the Federal Government pursuant

to 42 U.S.C. §1971 (c). Therefore, it has no application in a

suit, such as the present one, brought by private persons

relying on 42 U.S.C. §1983.

Section 1995 was added to Title 42 of the United States

Code as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Thus, in the

language, “In all cases of criminal contempt arising under

the provisions of this Act,” the words “this Act” refers only

to Public Law 85-315, the Civil Rights Act of 1957 (71 Stat.

638). (See Annotation to 42 U.S.C. §1995 in United States

Code Annotated, and Federal Code Annotated). An ex

amination of the 1957 Civil Rights Act shows that §1995

has reference only to suits brought under 42 U.S.C. §1971,7

7 28 U.S.C. §1343(4) was also added by the 1957 Civil Rights Act.

However, this section only provides an additional jurisdictional base in

the district courts for civil rights eases, particularly the category of voting

rights cases established by 42 U.S.C. §1971(c). As will be shown in the

text, infra, the class in whose behalf the contempt citation was issued

based their claim on 42 U.S.C. §1983 and 28 U.S.C. §1343(3). The 1957

Civil Rights Act also enacted 42 U.S.C. §§1975-1975e, which established

16

and specifically under subsection (c), which gives the At

torney General of the United States the power to institute

civil actions or other proceedings, including an applica

tion for permanent or temporary injunction, in order to

prevent acts which would deprive any person of any right

or privilege secured by subsection (a) or (b) of Section

1971.

That the proper construction of §1995 is that it serves as

a limitation on the power of the Federal District Court

to punish for contempt only in suits brought on behalf of

the Federal Government under §1971 (c) is demonstrated

by the legislative history of the Act. A central concern of

members of Congress was that the 1957 Act might be used

as a vehicle by the Federal Government to punish, by sum

mary proceedings for contempt, actions which would other

wise be in violation of the existing criminal laws of the

United States. Therefore, they wished to provide the pro

tections that attach in normal criminal proceedings where

citations for contempt of injunctions obtained by the

Federal Government were sought. It is clear that there

was no intention to limit the traditional power of a court

of equity sitting in a case brought by private parties, as

here.8

the United States Commission on Civil Rights and added and amended

other miscellaneous provisions of the United States Code which are not

at issue here.

8 The discussion in Congress of §1995, which was introduced as an

amendment to the original bill, focused entirely on the problem of possible

abuses of power by the Federal Government acting as a plaintiff in an

action brought under 42 U.S.C., §1971. Representative Keeney of Illinois

introduced an amendment which was similar in purpose to the one finally

adopted as §1995, and in support of his amendment, he stated:

The plaintiff under this measure is the government of the United

States of America. The prosecutor is the Attorney General of the

United States of America . . . And before whom is the measure heard?

Before a Federal judge . . . The plaintiff is the United States; the

prosecutor is the United States; and the judge is the United States.

But just to make sure, as sure as it can be, that the accused will he-

17

The complaint here was filed by private parties represent

ing three classes of plaintiffs: persons seeking to register

to vote; persons seeking to vouch for registrants; and per

sons seeking to exercise their rights of free speech and as

sembly. The suit was brought under 42 U.S.C. §1983, which

states:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, or usage of any State or

Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citi

zen of the United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution

and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an ac

tion at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding

for redress.

As to the first two classes of plaintiffs, the rights claimed

to be deprived were those established by the Fifteenth

Amendment to the Constitution and elaborated by 42 U.S.C.

§§1971(a) and (b) (enacted pursuant to Congress’ enforce

ment powers under Section 2 of the Amendment), which

provide that all citizens shall have the right to vote with

out distinction on the basis of race and color and the right

to be free of intimidation, threats or coercion in the exercise

of the right to vote.9

come a convicted defendant, they proceed to strip him of his right to

a trial by a jury of his equals or his peers. 103 Cong. Rec. 9187 (85th

Congress, 1st Sess., June 14, 1957).

See also the Remarks of Senator Robertson of Virginia, id. at 8468 (June

6, 1957) and Senator Ervin of North Carolina, id. at 8471, 8472-73 (June

6, 1957).

9 I t is clear that §§1971 (a) and (b) only set out in greater detail the

rights established by the Fifteenth Amendment, and do not in and of

themselves give the right to bring suit. Voting suits may be brought only

under §1971 (c), and that section gives such authority only to the At

torney General of the United States.

18

The third class of plaintiffs, on the other hand, claimed

solely that they were deprived, under color of law, of rights

secured by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution, i.e., the rights to freedom of speech and as

sembly, Thus, in no way did they assert the deprivation of

rights secured by either the Fifteenth Amendment or

§1971.10

And, of course, the contempt citation at issue here was

granted on behalf not of the first two classes of plaintiffs,

but rather on behalf of members of this third class. That

is, the appellant was found in contempt because he had

violated that portion of the court’s order which enjoined

him from intimidating or harassing “those legally . . . en

couraging [others] to register to vote.” Since §1995 thus

did not apply, the District Court possessed the power in

herent in a court of equity and as provided in 18 U.S.C.

§401, which states in part:

A court of the United States shall have power to pun

ish by fine or imprisonment, at its discretion, such

contempt of its authority, and none other, as . . .

(3) Disobedience or resistance to its lawful writ, proc

ess, order, rule, decree or command.

Similarly, the limitations in §1995 on the fine that may

be imposed also did not apply (see, supra, Part 11(A)).

And under the provisions of 18 U.S.C. §401, as the Court

stated in The United States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. 681 at 692:

10 The jurisdictional basis for the action on behalf of the third class

was, therefore, 28 U.S.C. §1343(3), which states, in part, that the district

courts have jurisdiction of actions:

To redress the deprivation, under color of any State law, statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom or usage, of any right, privilege, or

immunity secured by the Constitution of the United States . . . .

19

It has always been the law of the land, both state and

federal, that the courts—except where specifically pre

cluded by statute—have the power to proceed sum

marily in contempt matters.11

In summation, appellees contend that: 42 U.S.C. §1995

applies only to suits brought under the Civil Eights Act

of 1957, i.e., to suits brought by the Attorney General of

the United States pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1971 (c). The suit

herein was brought by private parties under 42 U.S.C.

§1983, although the first two classes of plaintiffs claimed

the deprivation of rights protected by the Fifteenth Amend

ment and 42 U.S.C. §1971 (a) and (b). Even if it were as

sumed, for the sake of argument, that the appellant might

have had a right to a trial de novo by a jury if he had

been found in contempt of that portion of the trial court’s

order that protected the first two classes of plaintiffs, he

would not have such a right with regard to the contempt

citation that actually issued. This result must follow since:

(1) the right to a jury does not attach under §1995 until

after a finding of contempt in a case arising from the 1957

Act; and (2) the finding of contempt here was on behalf

of plaintiffs claiming the rights of free speech and as

sembly, and not rights arising under that Act.

11 Appellant did not raise at trial nor has he raised here the question

of the applicability of 18 U.S.C. §§402 and 3691, which also provided for

jury trial of criminal contempts under certain circumstances. Since Sec

tion 3691 requires that the plaintiff demand a trial by jury and since no

demand was made, it is clear that appellant has waived any possible

rights he might have under that section. (Section 3691 has no provision

for a request for a trial de novo by a jury after conviction by the court,

as does 42 U.S.C. §1995.) However, even if such a demand had been

made, it is clear that the above sections would have no application. They

are limited to the situations where the act cited as a contempt of the court’s

order also constitutes a criminal offense under any act of Congress or

under the law of the state in which the act was done or committed. Neither

the plaintiff nor the appellant claims that the act committed would consti

tute such a crime. The facts in this case do not establish that there was

the commission of such a crime.

20

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment below should

be affirm ed.

Respectfully submitted,

N orman C. A makeb

J ack Greenberg

Charles H. J ones, J r.

Charles S tephen Ralston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Appellees

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C . * * ® * - 2 ">