Jackson v. Georgia Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

September 9, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Georgia Brief for Petitioner, 1971. c9cba204-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bccc12ae-dd82-4e19-b8ca-0e6f99e04f22/jackson-v-georgia-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

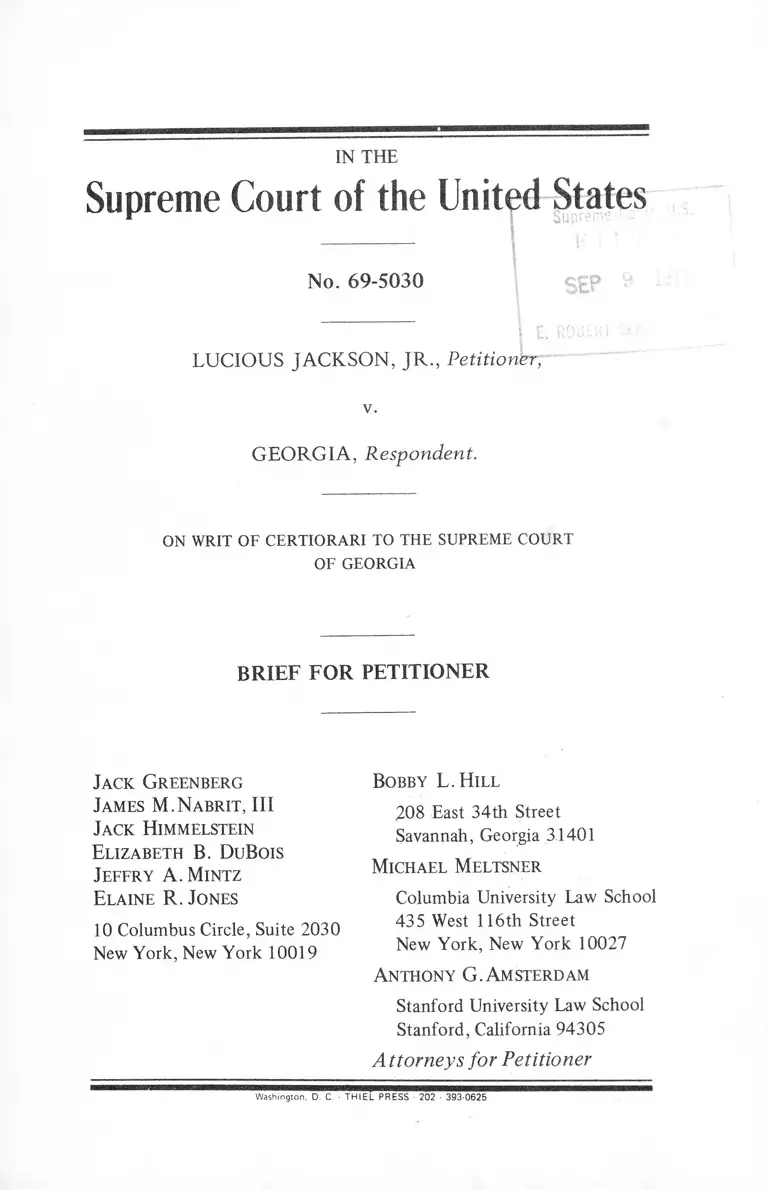

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 69-5030

LUCIOUS JACKSON, JR., Petitioner,

v.

GEORGIA, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack G reenberg

J ames M .N a b r it , III

J ack H immelstein

E lizabeth B. Du Bois

J effr y A .M intz

E laine R. J ones

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Bobby L .H ill

208 East 34th Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

M ichael M eltsner

Columbia University Law School

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

A nthony G .A m sterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

A ttorneys for Petitioner

Washington. D. C. • THIEL PRESS ■ 202 ■ 393 0625

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINION BELOW ............................................................ 1

JURISDICTION................................................................................ 1

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED . .......................................................... 2

QUESTION PRESENTED ............................................................ 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ....................................................... 2

HOW THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION WAS

PRESENTED AND DECIDED BELOW ................................... 10

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....................................................... 11

ARGUMENT:

I. The Death Penalty for Rape Violates

Contemporary Standards of Decency in

Punishment .......................................................................... 11

II. The Death Penalty for Rape Is

Unconstitutionally Excessive.................................................. 17

CONCLUSION ............................................................................... 21

Appendix A: Statutory Provisions Involved .............................. la

Appendix B: History of Punishment for Rape in Georgia . . . . . lb

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).................... 14

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1 9 6 8 )................................... 19

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) .............................. 20

O’Neil v. Vermont, 144 U.S. 323 (1892) ................................... 17

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) .............................. 17

State v. Jackson, 225 Ga. 790, 171 S.E.2d 501 (1969)............... 1

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) .......................................... 16, 17

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910).............................. 18

(i)

(it)

Constitutional and

Statutory Provisions:

Eighth Amendment, United States Constitution. 2, 10, 11, 17, 18, 19

Fourteenth Amendment, United States Constitution . . . . 2, 10, 16

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3)......................................................................... 1

Del. Code Ann. (1953), tit. 11, § 7 8 1 ............ ............................... 15

51 Del. Laws, 1957, ch. 347, p. 742 (1958) .............................. 15

D.C. Code (1967), §22-2801 ........................................................... 15

District of Columbia Court Reform and Criminal

Procedure Act of 1970, §204, 84 Stat. 473 (1970) ............... 15

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1301 ................................................................ 2

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1302 ................................................................ 2

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2302 ................................................................ 2

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2512 ................................................................ 2

Nev. Rev. Stat. (1967), §200.363 ................................................. 14

W. Va. Acts, 1965, ch. 40, p. 207 (1965) ................................... 15

W. Va. Code, §5930 (1 9 6 1 ) ........................................................... 15

MAGNA CARTA, ch. 20-22 (1215) printed in ADAMS &

STEPHENS, SELECT DOCUMENTS OF ENGLISH

CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY (1926) 42, 45 ......................... 18

Other Authorities:

Brief for Petitioner, in Aikens v. California, O.T.

1971, No. 68-5027 11,13,16

Granucci, ‘TVor Cruel and Unusual Punishments Inflicted: ”

The Original Meaning, 57 CALIF. L. REV. 839

(1969) ......................................................................................... 18

Kahn, The Death Penalty in South Africa, 18

TYDSKRIF VIR HEDENDAAGSE ROMEINS-

HOLLANDSE REG 108 (1970)................................................. 13

MURRAY, STATES’ LAWS ON RACE and COLOR

(1950) ......................................................................................... 14

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77

HARV. L. REV. 1071 (1964) ............................................ 18, 19

Patrick, The Status o f Capital Punishment: A World

Perspective, 56 J. CRIM. L., CRIM. & POL. SCI.

397 (1965).................................................................................... 13

The Manchester Guardian Weekly, August 14, 1971 .................... 20

UNITED NATIONS, DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC

AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

(ST/SOA/SD/9-10) (1968) [cited as UNITED

NATIONS] .............................................................................12, 13

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE,

BUREAU OF PRISONS, NATIONAL PRISONER

STATISTICS, Bulletin No. 45, Capital Punishment

1930-1968 (August 1969) [cited as NPS (1968)] . . . 14, 15, 16-17

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 69-5030

LUCIOUS JACKSON, JR., Petitioner,

GEORGIA, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia affirming

petitioner’s convictioiKbf rape ana sentence of death by

electrocution is repotted af!225 Ga. 790, 171 S.E.2d 501,

and appears in the Appendix [hereafter cited as A. ___ ] at

A. 112-116.

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon 28 U.S.C. §1257

(3), the petitioner having asserted below and asserting here

a deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution of the

United States.

2

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was

entered on December 4, 1969. (A. 116) A petition for

certiorari was filed on March 4, 1970, and was granted

(limited to one question) on June 28, 1971 (A. 117).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Eighth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States, which provides:

“Excessive bail shall not be required, nor exces

sive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punish

ments inflicted.”

It involves the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

It further involves Ga. Code Ann. §§26-1301, 26-1302,

27-2302, 27-2512, which are set forth in Appendix A to

this brief [hereafter cited as App. A, pp. ___ ] at App.

A. pp. la-2a infra.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty

in this case constitute cruel and unusual punishment in vio

lation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Following a one-day trial, a jury of the Superior Court

of Chatham County, Georgia, convicted Petitioner Lucious

Jackson, Jr., a twenty-one year-old Negro,1 of the rape of

a white woman, and sentenced him to die in the elecfrfc

'cEalrT TKe~rap£ occurred on October 3, 1968; the trial on

December 10, 1968. Proceedings began at about 10:00 a.m.

with the overruling of various defense motions, including a

‘ (A. 13-14.)

3

motion for a continuance made on the grounds that peti

tioner’s court-appointed counsel needed “additional time

to prepare for a case of this magnitude” (A. 16 [Tr. 3]),

and that “ further [psychiatric] examination and observation”

were required (A. 17 [Tr. 5 ]) because petitioner’s one-hour

interview with a court-appointed psychiatrist2 3 4 was “insufTi-

cient m m mere fU1 T1'1“TT1 la 1'] . M4 no substance” (A. 17

determine petitioner’s mental competence to stand trial (A.

21-22 [Tr. 16-18]); it heard the testimony of the court-

appointed psychiatrist (A. 22-31 [Tr. 18-32] )4 and pro-

2The length of petitioner’s psychiatric examination had not been

established at the time of the motion, which was based upon the fact

that the court-appointed psychiatrist had examined petitioner on '

December 2 and made his report to the court on December 3. (A.

16 [Tr. 4].) Later, the psychiatrist testified that he had examined

petitioner for “ about an hour” (A. 23, 27 [Tr. 20, 25]), a period

which he believed sufficient to determine petitioner’s competency in

the circumstances of this case (A. 28-29 [Tr. 27-28]).

3Prior to trial, petitioner’s appointed counsel had filed a motion

for a sixty-day continuance and for allowance of funds to have the

indigent petitioner examined by a defense psychiatrist. (A. 5-6.) On

November 26, the court denied any continuance (A. 7), and appointed

a named psychiatrist to examine petitioner and to submit a report

“for the use of the Court, with a copy thereof’ to the prosecutor and

defense counsel. (A. 9) The report was submitted (A. 16-17 [Tr. 4

5]) but was not introduced into the record.

4The doctor testified that he had examined petitioner for “ about

an hour” on December 2, 1968 (A. 23 [Tr. 19-20]), and did not see

him again until the day of trial (A. 27 [Tr. 26]). He agreed that his

opinions were based entirely on what he found in that hour interview

(A. 27 [Tr. 25]). Although he administered no written tests, he

found the petitioner to be of “average education or average intelligence.”

(A. 24 [Tr. 20]). He determined that petitioner was not an imbecile

or schizophrenic, but he did find that he had a sociopathic person

ality. He defined this as not “a neurotic or psychotic type of illness,’’

but as traits which are the product of environmental influences (A.

25 [Tr. 22]), and which bring an individual “in conflict with society

and other people” (A. 24 [Tr. 21]). No evidence of a need for fur

ther observation was found (A. 29 [Tr. 28]), and the doctor concluded

that petitioner had the ability to understand his situation, and was

thus competent to stand trial (A. 30-31 [Tr. 30-31]).

4

nounced petitioner competent (A. 13.) Another jury was

immediately selected to try the issues of guilt and punish

ment (A. 33-41 [Tr. 37-48]); it was death-qualified by the

exclusion of eleven veniremen who were conscientiously

ojposed 16”capital punlsfimeh'ran3^aI^TfilTTh'ey“w(5ni^

never vote to impose tKe~13eaTfrpenarty^

lessortfiFcircumstances rArTj'-BVrTE'^TlPl);5..irTie~ard

evidence (A. 42-83 [Tr. 51-119]), and returned its death

verdict shortly after 6:00 p.m. (A. 15-16.)

The prosecutrix was Mrs. Mary Rose, a physician’s wife.

(A. 42-43 [Tr. 51].) She testified that on October 3, 1968,

her husband left the house for work at 7:00 a.m. She went

back to sleep and was awakened at about 7:45 by her four-

month-old baby crying for its bottle. She arose, diapered

and fed the baby, and let it play while she had toast and

coffee. Then, at about 8:30 a.m., she took the baby into

the nursery and bathed it. (A. 43-44 [Tr. 51-53].)

While bathing the baby, she heard a noise from the dining-

or living-room area of the house. Supporting the baby in

the tub with one hand, she stepped out into the hall and

looked in the direction of the noise but saw nothing. She

supposed that it was one of her cats, so she returned, fin

ished bathing the baby, and began to dress it in its crib.

She then heard a louder and more unusual noise from the

same area. Since the baby was safe in its crib, she went to

investigate. Again she saw nothing and returned to the nur

sery. (A. 44-47 [Tr. 53-57].)

Turning for some reason toward the baby’s closet, she

suddenly saw a “young colored male” (A. 47 [Tr. 58])—

whom she identified at trial as the petitioner (A. 59 [Tr.

76])— standing in the closet. He held a half of a pair of

scissors in his hand, with the handle wrapped in a cloth.

Petitioner unsuccessfully objected to the excuse of these venire

men for cause. (A. 34, 35 [Tr. 37, 39].) The Georgia Supreme Court

subsequently held that their exclusion was proper under Witherspoon

v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968). (A. 114.)

5

(A. 47 [Tr. 58 ],)6 Mrs. Rose screamed, but before she

could do anything, petitioner crossed the room, took her

by one arm, and placed the half-scissors so that they were

“pressing against the right side of [her] . . . neck, right at

[her] . . . carotid artery.” (A. 48 [Tr. 58].) She “was

screaming and trying to get away, and . . . pushing him with

[her] . . . free arm,” but he told her that if she did not “be

quiet he was going to have to hurt [her] . . ., and the scis

sors were really pressing into [her] . . . neck.” She did

stop screaming, and he told her “ that all he wanted was

money, if [she] . . . just would give him money that he

would go away and he would not hurt [her] . . . .” (A.

48 [Tr. 59].)

She was anxious to get him out of the baby’s room as

quickly as she could. Leaving the baby in the crib, they

went first into the living-room, then the dining-room, then

back up the hall and into a bathroom, looking for money.

He asked her where the money was and, throughout this

period, he continued to hold the scissors against her neck

and to push her along. (A. 48-49 [Tr. 59-61 ].) They found

a pocketbook in the bathroom, but it had no money in it,

so he pushed her on into the bedroom, still with the scissors

against her neck. Seeing a five-dollar bill and change on a

dresser, he put the scissors down to take the money. (A.

49 [Tr. 61].)

She then grabbed the scissors. He had been holding her

left hand behind her while pushing her, and was still behind

her, holding that hand. She took the scissors in her right

hand and “ tried very hard to stab him anywhere,” but could

not reach him. While she was trying to stab him, they fell

together onto the nearby bed. She was on top with the

scissors and struggled for awhile trying to stab him. When

she failed at this because he was holding her arm, she threw

6Mrs. Rose identified the half-scissors as her own, which petitioner

apparently took from some area of the house and disassembled by

removing the nut or screw that held the halves together. (A. 56 [Tr.

72].)

6

the scissors out of his reach onto the floor. They both

struggled and fell near the scissors, and she recovered them

again. (A. 49-50 [Tr. 61-64].) “But he knocked [her] . . .

backwards on the floor, and [she] . . . was on [her] . . .

back at that point. And he was on top trying to get the

scissors from [her] . . . hand.” (A. 51 [Tr. 64].)

They continued to struggle, he trying to take the scissors

from her, she trying “to get the scissors into him anywhere

[she] . . . possibly could.” (A. 51 [Tr. 64].) She kept

her grip on the scissors, but he got her arm behind her and

began to beat her hand that was holding the scissors “very

hard against the toot of the bed. She had had a cortisone

injection “ for a tendon” in that wrist about a week before;

it was still sore from the injection; and she couldn’t hold

the scissors any longer, so she tossed them away again.

They both struggled after the scissors, and this time he got

them in his left hand. (A. 51-53 [Tr. 64-66].)

She “was on the floor, and he was on top of [her] . . . .”

He had her right arm pinned down with his left, and again

he “was holding the scissors against [the] . . . side of [her]

. . . neck.” He had her legs pinned to the floor with his

knees, and was holding her left hand in his right. He told

her if she “moved anymore he was going to hurt [her] . . .

or kill [her] . . . Then he released her left hand, pulled

her gown open down the front, unzipped his pants, and had

sexual intercourse with her, effecting penetration. (A. 53-

54 [Tr. 66-69].) She was trying to push him away with her

left hand, but “ the more [she] . . . pushed, the deeper those

scissors went into [her] . . . neck, just right . . . against the

carotid artery.” He “grabbed [her] . . . hand [that] . . .

was trying to push him away . . ,[a]nd he kept telling

[her] . . . if [she] . . . continued to struggle that he would

have to hurt [her] . . . or kill [her] . . . and just to be still

. . . [a]nd . . . the scissors just were pressing very deeply

into [her] . . . neck.” (A. 54 [Tr. 68].)

While he was on top of her, the maid arrived for work

and knocked on the back door. Mrs. Rose “had been telling

7

him that the maid was coming, hoping that this would get

him to leave.” She heard the maid knocking and told him,

but he did not believe her and did not stop. The maid then

came around to the front door; she apparently “could see

the baby screaming and the side rail down on the crib

through [the] . . . window” of the nursery; and the maid

began to shout Mrs. Rose’s name at the front door. (A. 54-

55 [Tr. 69].)

Petitioner heard the maid, got to his knees, and then

pulled Mrs. Rose to her feet by the arm, still holding the

scissors “ pressing into [her] . . . neck.” They stood by the

bedroom window, with its drawn shade, and he told her to

go and let the maid in. She did not want to do so because

“ the baby was still there” and he “still had the scissors,”

so she reached over and flipped the shade up quickly. This

startled him; he saw that the window was up and the screen

was unlocked; and he went out the window. (A. 55-56 [Tr.

71].)

Mrs. Rose then locked the screen behind him, let the

maid in, told the maid that she had been raped, and asked

her to get the baby and bring it out of the house. With the

maid carrying the baby, they went to the next-door neigh

bor’s home, where Mrs. Rose told the neighbor that she had

been raped and to phone the police. (A. 57 [Tr. 72-73].)

This was about 9:00 a.m. (A. 68-73 [Tr, 78-79, 82].) The

maid described Mrs. Rose at this time as “very upset and

hysterical” (A. 62 [Tr. 81]), and the neighbor testified that

she was “real upset and terrified” (A. 63 [Tr. 82]):

. . And her hair was all messed up. She had on

her gown and it was tom, and she had blood all on

the bottom of her gown. And she kept saying that

she’d been raped. She said, Tve been raped.’ And

she said, ‘He tried to kill me,’ said, ‘He had a knife—

or scissors to my throat,’ said, ‘I just knew he would

have killed me,’ said, ‘I was worried about the baby’.”

(A. 63-64 [Tr. 82].)

An investigating detective, who soon arrived, also found Mrs.

Rose “very upset,” with “ tears in her eyes,” “very emo

tional.” (A. 65 [Tr. 84].)

8

Despite Mrs. Rose’s ordeal—and without diminishing that

ordeal in the slightest—it is the fact that she emerged with

no physical injuries other than some bruises and abrasions.

Mention has been made that her neighbor saw blood on her

gown (A. 63-64 [Tr. 82-83]); and the investigating detective

also found blood on the bedroom floor (A. 66 [Tr. 85]).

But the record does not indicate that this was Mrs. Rose’s

blood rather than petitioner’s. To the contrary, an obstetri

cian and gynecologist who examined Mrs. Rose between

10.30 and 11:00 a.m. the same morning described the

extent of her injuries as follows:

On examination, the soft tissue—soft tissues in

the anterior of the throat were very tender on pal

pation. There was an abrasion over the right clavicle

or the right collar bone, and there were superficial

lacerations of the right forearm and the right—palm

of the right hand. There was also an abrasion on

the anterior surface of the right tibia or the right

lower leg. On pelvic examination, there was a small

amount of blood in the vagina and the coccyx or

tail bone so to speak was very tender to palpation ”

(A. 69-70 [Tr. 90-91].)

Apparently, Mrs. Rose was not hospitalized: she was back

at her house by about 2:00 p.m that afternoon, when peti

tioner was arrested in the area. (A. 66-67 [Tr. 86-87].)

Nor is this a case of rape in which any serious or long-term

psychological harm to the unfortunate victim appears.

Petitioner had apparently entered the Rose house by re

moving a perforated cardboard panel which the Roses kept

inserted in the bottom of a jalousie door to permit their

cats to go in and out freely. (A. 57-58, 83 [Tr. 73-75, 118-

119].) After he left the house following his assault on Mrs.

Rose, he fled on foot and hid in a neighbor’s garage. Between

1:30 and 2:00 p.m that afternoon, he was found in the

garage by Dr. Rose and the neighbor; the neighbor trained

a gun on petitioner; petitioner fled with the neighbor shout

ing in pursuit; he was stopped by other persons in the area

and then arrested by police. (A. 71-72 [Tr. 93-95].)

9

This is all that the evidence presented at the trial reveals

about petitioner and his offense. However, the sentencing

jury almost surely knew that, at the time of his assault up

on Mrs. Rose, petitioner was a convict who had escaped

from a Negro prisoners* 1 work 'gang j n the ' aTeaTwnere1 lie

had been "serving a three-year sentence for auto theft; and

thaTduring the three days' when he remained at large, he

in the vicinity.

These’"matfeH^wSrTe'xtensively rep or ted in newspaper arti

cles (A. 86-98 [Tr. 122-130]) introduced by petitioner7

in support of his unsuccessful motion for a change of

venue (A. 17, 18-21, 41-42 [Tr. 5, 11-16, 49-50]); and they

were known to at least one venireman, whom the court

nonetheless refused to excuse upon petitioner’s challenge

for cause. (A. 37-40 [Tr. 43-47].) Because these articles

portray a somewhat inaccurate version of the other offenses

in question, we recite below the evidence concerning them

that was presented at petitioner’s preliminary hearing on the

several charges.8 The articles also reveal that the local com

7(See A. 18-19 [Tr. 11-13].)

8On October 28, 1968, petitioner was given a preliminary hearing

on the present charge of rape and on the several other charges. The

transcript of the preliminary hearing on all charges was a part of this

record in the trial court, but does not appear to have been before the

Georgia Supreme Court and was not certified to this Court. It is cited

hereafter in this footnote as P. T r .___.

Petitioner apparently left the work gang on September 30, 1968.

He was thereafter charged with the following offenses, all in the area

of his escape:

(1) Burglary’, October 30, 1968. Late in the afternoon of Octo

ber 30, an intruder broke a screen and entered the home of a Mr.

McGregor. Subsequently, a pair of black boots were found under a

bed in the McGregor house and were identified as convict’s boots

issued to petitioner before his escape. A pair of shoes and a pocket

knife were taken from the house. Petitioner was wearing the shoes

when he was arrested on August 3; and the pocket knife was found

at the scene of a subsequent burglary with which he was charged (see

paragraph (3) infra). No one was home in the McGregor house at the

time of the entry. (P. Tr. 39-47, 58, 62-64.)

(2) Auto theft, October 1 or October 2. Late at night on Octo

ber 1 or early in the morning on October 2, a station wagon belong

10

munity was upset and angry because police officials had

failed to give any warning that an escaped convict was at

large (A. 86-87, 93 [Tr. 122, 127]; and that petitioner

was taken quickly from the area by police following his

arrest, because of an angry crowd of area residents at the

scene (A. 94, 95 [Tr. 128, 129] ).9

HOW THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION WAS

PRESENTED AND DECIDED BELOW

Paragraph 18 of Petitioner’s Amended Motion for New

Trial, filed by leave of court, contended that the death sen

tence which had been imposed upon him was a cruel and

unusual punishment forbidden by the Eighth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States. (R.

29, 31.) The motion was overruled. (R. 36.) Paragraph 6

of petitioner’s Enumeration of Errors in the Georgia Supreme 3 4 * * *

ing to a Mr. Summerall was taken from his carport. The keys had

been left in the car. Subsequently, the car was found in a church

parking lot in the vicinity. The car keys, on a clip with the keys to

the Summerall house, were found in Mrs. Rose’s home following the

assault on her. (P. Tr. 47-53.)

(3) Burglary and assault and battery, October 2. At about 3:30

a.m. on October 2, an intruder entered the home of a Mrs. Coursey

by cutting a window screen. One of Mrs. Coursey’s teenage daughters

awakened to see a figure standing over the bed in her room. She

thought that it was her mother, reached up and touched the person

on the neck, then saw that it was a colored man and began to scream.

He slapped her on the arm and told her to ‘Sh--,” but she continued

to scream and may have kicked him. He then fled from the house.

Later, the knife taken from the McGregor house (paragraph (1) supra)

was found in the Coursey house. (P. Tr. 55-63.)

(4) The rape of Mrs. Rose on October 3.

9The article at A. 94 [Tr. 128] also reports that petitioner was

struck several times, at least once by a gun butt, following his appre

hension by area residents and prior to his removal by police.

Court made the same contention.10 The Georgia Supreme

Court rejected it upon the merits. (A. 114.)

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Even more than for the crime of murder, the use of

the death penalty for the crime of rape is overwhelmingly

repudiated by contemporary standards of decency. The

retention on the statute books and the sporadic infliction

of the punishment of death for rape in the Southern States

are accounted for exclusively by racial considerations, and

do not demonstrate public acceptance of the fitness of the

penalty for this offense. Under any construction of the

Eighth Amendment which would not render it obsolete

and futile, capital punishment for rape is a cruel and unusual

punishment.

II. The Eighth Amendment forbids punishments which

are grossly excessive and disproportioned to the offense.

While rape is a serious offense, it is almost nowhere viewed

today as warranting the punishment of death except where

race is added to the balance. In the nearly universal estima

tion of civilized nations capital punishment for rape is exces

sive. It therefore violates the Eighth Amendment.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DEATH PENALTY FOR RAPE VIOLATES

CONTEMPORARY STANDARDS OF DECENCY IN

PUNISHMENT.

The Brief for Petitioner in Aikens v. California11 sets forth

the reasons why we believe that the death penalty is a cruel

and unusual punishment for any civilian crime, as that pun

10P. 1 of the Enumeration of Errors, filed August 22, 1969. [This

document is contained in, but is not paginated as a part of, the original

record filed in this Court.]

n O.T. 1971, No. 68-5027.

12

ishment is administered in the United States today. The

essence of the argument is that all objective indicators prop

erly cognizable by this Court demonstrate a clear and over

whelming repudiation of the penalty of death by this

Nation and the world. The penalty survives on the statute

books only to be—and because it is—rarely and arbitrarily

applied to pariahs whose numbers are so few and persons

so unpopular that the public and the legislatures can easily

stomach the infliction upon them of harsh penalties that

would never be tolerated if generally enforced. This sort

of rare, terroristic infliction is precisely the evil against

which the Eighth Amendment must guard, if that Amend

ment is to serve a function among the guarantees of rights

in a democratic society.

It would serve no purpose to repeat the details of that

argument here. Several considerations which underline its

application to the crime of rape, however, deserve emphasis:

(1) The nations of the world, with extraordinary

unanimity, no longer punish rape with death. A United

Nations survey of more than sixty countries, which included

mos t̂ ofTTiF'major civilized nations, found that by 1965 all

InU three countries outside the United States had ceased to

employ capTCai T8r this c rim jl2’ The three

countries retaining the death penalty for rape were China

(Taiwanj^Malawi, and the Republic of South Africa.12 13 A

Sroacfe? but less reliable study by Patrick in 1963 covered

128 countries and found nineteen outside of the United

12UNITED NATIONS, DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SO

CIAL AFFAIRS, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (ST/SOA/SD/9-10) (1968)

[hereafter cited as UNITED NATIONS], 40, 86. We put aside three

countries that punish rape capitally only if it is followed by the victim’s

death. Ibid.

13The 1960 United Nations survey (UNITED NATIONS 40) lists

four countries as retaining the death penalty for rape: China, Northern

Rhodesia, Nyasaland, and the Republic of South Africa, Nyasaland

became Malawi upon its independence in 1964. Northern Rhodesia

became Zambia, and abolished the death penalty for rape by 1965.

UNITED NATIONS 86.

13

States that authorized capital punishment for rape.14 This

figure should be reduced by at least three on account of

errors15 and one known subsequent abolition.16 17 All of the

countries correctly listed by Patrick are in Asia or Africa;

and, in any event, Patrick’s data concerning their actual use

of the death penalty suggests that almost no one in the

world is actually executed for this cnme outside of The

Uartetl StgTSTaHd SoulKTfnca:'1;' —

(2) In the United (States, the death penalty for rape is

authorized by law in sixteen States and by the federal gov

ernment.18 Since 1930, 445 men have been put to death

14Patrick, The Status o f Capital Punishment: A World Perspective,

56 J. CRIM. L., CRIM. & Pol. Sci., 397, 398-404 (1965). The coun

tries are: Afghanistan, Austrialia, Basutoland, Bechuanaland, People’s

Republic of China, Gabon, Jordan, Republic of Korea, Malagasy Re

public, People’s Republic of Mongolia, Niger, Northern Rhodesia, My-

asaland [now Malawi], Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Republic

of South Africa, Turkey, and the U.S.S.R.

15Australia and the U.S.S.R., which Patrick lists, do not authorize

the death penalty for rape according to the United Nations survey.

Turkey, which Patrick also lists, was found by the United Nations to

punish rape with death only if the rape victim dies. On the other

hand, Patrick does not list China (Taiwan), as the United Nations sur

vey does. These errors decrease Patrick’s by a total of two.

16Northern Rhodesia (now Malawi). See note 13 supra.

17Patrick provides figures for the average yearly number of execu

tions (1958-1962) for all crimes for each country except the People’s

Republics of China and Mongolia, and Sierra Leone. None of the

countries for which figures are given executed more than two men a

year for all crimes, except Basutoland (3), Korea (68), Northern Rho

desia (6.5)—which has now abolished the death penalty for rape (see

note 13, supra)-and the Republic of South Africa (100). It is known

that fewer than 10 per cent of South Africa’s 100 executions yearly

are for rape, Kahn, The Death Penalty in South Africa, 18 TYDSKRIF

VIR HENDENDAAGSE ROMEINS-HOLLANDSE REG 108, 116-117

(1970).

18Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mary

land, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada (see note 20 infra). North Carolina,

Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. See Appen

dix G to Brief for Petitioner, in Aikens v. California, supra.

14

for this crime, but only twenty during the past decade and

none since 1964.19

(3) It is instructive to consider the geography of capital

punishment for rape in this country. With the exception of

Nevada (which punishes the crime capitally only in the

event of “substantial bodily harm” 20and has not executed a

man for rape since at least 193021 ) all of the States which con

fer discretion on their juries to impose death as the penalty

for rape are Southern or border States.22 TRTs' geogfap'hit dis-

tribiTtitm ddes not seenT'accfdeTrta-lr-frr*l 954 this Court in

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), declared

racial discrimination in the public schools unconstitutional.

Here are comparative lists of all the States whose statutes

required or authorized racial segregation in the public schools

in 1954 and of those which now authorize capital punish

ment for rape:

Segregation States23

Alabama

Arizona

Arkansas

Delaware

District of Columbia

Florida

Georgia

Kansas

Death Penalty States

Alabama

Arkansas

Florida

Georgia

19UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, BUREAU OF

PRISONS, NATIONAL PRISONER STATISTICS, Bulletin No. 45,

Capital Punishment 1930-1968 (August 1969) [hereafter cited as NPS

(1968)], p. 7.

^Nev. Rev. Stat. (1967), §200.363.

21 NPS (1968) 11. The federal government has executed only two

men for rape since 1930. Id, at 10.

22See note 17, supra.

23As listed in Murray, States’ Laws on Race and Color (1950), 14

n. 47.

5

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maryland

Mississippi

Missouri

New Mexico

North Carolina

Oklahoma

South Carolina

Tennessee

Texas

Virginia

West Virginia

Wyoming

(Delaware, the District of Columbia and West

Virginia also punished rape with death until

1958, 1970, and 1965 respectively.)24

(4) The racial figures for all men executed in the United

States for the crime of rape since 1930 are as follows: 48

white, 405 Negro, 2 other.25 In Georgia, the figures are: 3

white, 58 Negro.26 These figures are also clearly not acci

dental. In Appendix B to this brief, we trace the history

of the punishment for rape in Georgia since the days of

slavery. Briefly stated, prior to the Civil War rape committed

by a white man was never regarded as sufficiently serious

to warrant a penalty greater than 20 years imprisonment.

Rape committed by a slave or a free person of color upon

a white woman was punishable by death. One year after

24Del. Code Ann. (1953), tit. 11, §781, repealed by 51 Del. Laws,

1957, ch. 347, p. 742 (1958).

D.C. Code (1967), §22-2801, repealed by District of Columbia

Court Reform and Criminal Procedure Act of 1970, §204, 84 Stat.

473, 600 (1970).

W. Va. Code, §5930 (1961), repealed by W. Va. Acts, 1965, ch.

40, p. 207 (1965).

25NPS (1968) 10.

^NPS (1968) 11.

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maryland

Mississippi

Missouri

Nevada

North Carolina

Oklahoma

South Carolina

Texas

Virginia

16

the abolition o f slavery, a facially color-blind s ta tu te was

enacted, giving juries discretion to sentence any man con

victed o f rape to either death or not m ore than 20 years

im prisonm ent. It was no t until 1960 tha t the th ird option

o f life im prisonm ent was added to these tw o alternatives.

The objects o f the alternatives have been perfectly obvious

to Georgia juries, and should be no less obvious to any

observer.

We m ake this point no t to dem onstrate a denial o f the

Equal P ro tection o f the Laws—a claim no t now before the

Court and whose vindication is im peded by considerable

d ifficu lties27—b u t to dem onstrate rather the nature and

ex ten t o f the accep tance28 which the death penalty for rape

enjoys in Georgia and in this country today. The roots o f

tha t acceptance lie in racial, no t penal, considerations; and

its ex ten t is am ply signified by Georgia’s execution o f three

white men in fo rty years for rape. During the same forty

years, the U nited States collectively have to lerated just a

little more than one white execution per year for this

offense. No single State has to lerated a fraction o f tha t

to ta l.29 Palpab ly , capital punishm ent for rape is n o t “ still

27See Brief for Petitioner, in Athens v. California, O.T. 1971, No.

68-5027, pp. 51-54.

28As in the Athens brief, supra, our argument here addresses the

question whether the death penalty for rape “is still widely accepted,”

within the meaning of Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 99 (1958) (plural

ity of opinion of Chief Justice Warren).

29Since 1930, the following American jurisdictions have executed

the following numbers of men for rape:

Federal Government

White

2

Negro

0

District of Columbia 0 3

Alabama 2 20

Arkansas 2 17

Delaware 1 3

Florida 1 35

Georgia 3 58

Kentucky 1 9

Louisiana 0 17

17

widely accepted” * 30, or accepted at all when race does not

ated and rejected; and under any standard of the Eighth

Amendment which considers “ the evolving standards of

decency that mark the progress of a maturing society,” 31

it is an unconstitutional cruel and unusual punishment.

II. THE DEATH PENALTY FOR RAPE IS

UNCONSTITUTIONALLY EXCESSIVE

The same facts regarding the manner and extent of con

temporary usage of the death penalty for rape also reflect

upon another fundamental Eighth Amendment concern.

This is the “inhibition . . . against all punishments which by

their excessive . . . severity are greatly disproportioned to

the offences charged.”313 Restraints upon excessive punish

Maryland 6 18

Mississippi 0 21

Missouri 3 7

North Carolina 4 41*

Oklahoma 0 4

South Carolina 5 37

Tennessee 5 22

Texas 13 71

Virginia 0 21

West Virginia 0 1

*and 2 “other.”

NPS (1968) 10-11.

30See note 28, supra.

31 Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 100 (1958) (plurality opinion of

Chief Justice Warren).

31aO’Neil v. Vermont, 144 U.S. 323, 337, 339-340 (1892) (Mr. Jus

tice Field, dissenting). Justices Harlan and Brewer agreed with Justice

Field that O’Neil’s sentence was excessive “in view of the character

of the offences committed.” Id. at 366, 371. The majority of the

Court declined to reach the merits of the question because it was not

properly presented and because the Eighth Amendment was not then

viewed as a restraint upon the States. Id., at 331-332. But see Rob

inson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962); Brief for Petitioner, in Aikens

v. California, supra, n. 24.

18

ment run deep in the Anglo-American tradition;32 and their

expression in the Eighth Amendment was a principal ground

of decision in Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910)

Although the cadena temporal and its accessories were visi

bly harsh and outlandish in nature, their condemnation in

Weems rests expressly upon their oppressiveness for the

crime of falsifying public records, and their consequent lack

of adaptation ot punishment to the degree of crime.” Id

at 365.33

To be sure, this constitutional concept of adaptation

does not require that the punishment fit the crime like a

glove. Neither legislatures nor courts, nor the sciences of

penology are equipped for that kind of measurement. See

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77 HARV. L.

REV. 1071, 1078-1080 (1964). However, it would ignore

the entire experience of our criminal law system to deny

that the grading of offenses by their seriousness is endemic

to it;34 and, in this context, the Eighth Amendment’s pro

32Magna Carta contains three chapters requiring that amercements

be proportioned to the measure of magnitude of offenses. MAGNA

CARTA, ch. 20-22 (1215), printed in ADAMS & STEPHENS, SELECT

DOCUMENTS OF ENGLISH CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY (1926)

42,45. These and other aspects of the English tradition are discussed

in Granucci, “Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments Inflicted:'’ The

Original Meaning, 57 CALIF. L. REV. 839, 844-847 (1969). In foot

note 36 of the Brief for Petitioner, in Aikens v. California, supra, we

explain why the additional concern of the American Framers against

barbarous punishments implies no abandonment of the traditional

English restriction upon excessive ones.

33See id. at 377:

“It is cruel in its excess of imprisonment and that which

accompanies and follows imprisonment.. It is unusual in its

character. Its punishments come under the condemnation of

the Bill of Rights, both on account of their degree and kind.

And they would have those bad attributes even if they were

found in a Federal enactment and not taken from an alien

source.”

■̂ We are aware of no jurisdiction that does not operate upon this

principle in the legislative prescription of the maximum penalties for

grades of offenses. “ Individualization” of punishment is invariably

19

hibition of cruel and unusual punishments must impose

some restriction upon a legislature’s power to proceed aber

rantly in affixing maximum penalties to grades of crime.35

The question is whether Georgia has done so here in pun

ishing rape with death. That question is answered, we think,

by the nearly universal judgments of mankind. Rape is

assuredly a serious offense, and we do not minimize its seri

ousness. But almost nowhere in the world today, except in

the American South and in South Africa, is the death penalty

inflicted for it. Other punishments for other crimes may

vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, providing no basis for

estimation of a commonly perceived relationship of fitness

between them. Death punishment for rape is, by extraor

dinary national and worldwide accord, perceived to be

excessive.

Even this might not condemn it if the States in which it

was used had some particular local situation to which it

legitimately responded. But the situation to which it in

fact responds in the American Southern States—and, once

permitted within legislatively fixed limits determined by the serious

ness of the crime. In the present case, of course, the Court is con

cerned only with the permissibility of the statutory maximum as a

maximum; and so the complexities of accounting for individualiza

tion-stressed by Professor Packer, supra, 77 HARV. L. REV., at 1080-

1081—appear to be wide of the mark. Doubtless a theoretical system

of criminal justice could be designed in which offenses were not

graded nor maximum penalties assigned to them according to their

character. And in the context of such a system, an Eighth Amend

ment might require no adaptation of crime and penalty. But that is

not the American criminal justice system or the context of the Eighth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Cf. Duncan v.

Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 149-150 n. 14 (1968).

35Even Professor Packer seems to admit this point, saying that life

imprisonment or capital punishment for trivial offenders “might be

ruled out.” Packer, supra, 77 HARV. L. REV., at 1081. He explains

this result in terms of “ decency,” not excessiveness. But there seems

to be nothing indecent about a life sentence for jaywalking, except

the indecency that arises from its perceived excessiveness.

20

again, in South Africa36—cannot be thought to justify it.37

Both the legisaltive history of the Georgia rape statute 38

and its actual use by Georgia juries39 demonstrate that

death has not been thought to be a fitting punishment for

rape in that State in the absence of racial considerations.

^ I t has recently been reported that, between 1947 and 1969, 844

rape convictions of black South Africans resulted in 121 death sen

tences, while 288 rape convictions of white South Africans resulted

in 3 death sentences. The Manchester Guardian Weekly, August 14,

1971, p. 4.

37McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964),

38See Appendix B to this brief.

39 See text at note 26 supra.

21

CONCLUSION

The death sentence imposed upon petitioner Lucious

Jackson, Jr., should be set aside as a cruel and unusual

punishment.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JACK HIMMELSTEIN

ELIZABETH B. DUBOIS

JEFFRY A. MINTZ

ELAINE R, JONES

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

BOBBY L. HILL

208 East 34th Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

MICHAEL MELTSNER

Columbia University Law

School

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law

School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioner

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

APPENDICES

Statutory Provisions:

Ga. Acts 1811, No. 503, 797-800 .................................................. lb

Ga. Acts. 1815, No. 504, printed in LAMAR, COMPILATION

OF THE LAWS OF GEORGIA, p. 800 (1821) .................... lb-2b

Ga. Acts. 1816, No. 508 § 1, printed in LAMAR, COM

PILATION OF THE LAWS OF GEORGIA, p. 804 (1821) . . 2b

Ga. Acts 1866, Nos. 209, 210, p. 151 ..................................... 4b

Ga. Acts 1866, No. 236, p. 233 4b

Ga. Acts 1960, No. 587, p. 266 6b

Ga. Acts 1963, No. 56, §2, pp. 122-123 .............................. la

Ga. Acts 1968, pp. 1249, 1299 ....................................................... 6b

Ga. Code Ann., §26-1302 (1953) ............................................... 4b, 6b

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1301 ................................................................ la

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1302 ................................................................ la

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2302 ................................................................ la

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2512 ................................................................ 2a

Ga. Crim. Code § 26-2001 2a

Ga. Crim. Code §26-3102 ................................................................. 2a-3a

Penal Code of 1811, §§ 60, 67, printed in LAMAR,

COMPILATION OF THE LAWS OF GEORGIA, pp.

551-552 (1821) ........................... lb

Penal Code of 1816, §§ 33-34, printed in LAMAR,

COMPILATION OF THE LAWS OF GEORGIA, p.

571 (1821) 2b

Penal Code §§ 4248-4250, printed in CLARK, COBB &

IRWIN, CODE OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA (1861)

824 ............................................................. 2b-3b

Penal Code for Slaves and Free Persons of Color, §§ 4704,

4708, printed in CLARK, COBB & IRWIN, CODE OF

THE STATE OF GEORGIA (1861) 9 1 8 ................................... 3b

(A-i)

(A-ii)

Other Authorities:

Humphries of Lincoln, A Bill to be entitled An Act to alter

and change the 4249th and 4250th paragraphs of the Code

of Georgia (in Custody of Georgia State Archives,

Atlanta, Georgia) .......................................................................... 5b

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of

Georgia, Commenced November 1, 1866 (1866) .................... 5b

Journal of the Senate of the State of Georgia (1866) . ............. 5b

la

APPENDIX A

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Ga. Code Ann., §26-1301

(1953 Rev, vol.)

effective prior to July 1, 1969

26-1301. (93 P.C.) Definition.—Rape is the carnal knowledge of a

female, forcibly and against her will. (Cobb, 787.)

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1302

(1970 Cum, pocket part)

effective prior to July 1, 1969

26-1302. (94 P.C.) Punishment; recommendation by jury to mercy.

The crime of rape shall be punished by death, unless the jury recom

mends mercy, in which event punishment shall be imprisonment for

life: Provided, however, the jury in all cases may fix the punish

ment by imprisonment and labor in the pentientiary for not less than

one year nor more than 20 years. (Cobb, 787. Acts 1866, p. 151;

1960, p. 266.)

Ga. Code Ann., §27-2302

(as amended by Ga. Acts, 1963,

No, 56, §2, pp. 122-123, effec

tive March 14, 1963)

effective prior to July 1, 1969

27-2302. In all capital cases, other than those of homicide, when

the verdict is guilty, with a recommendation to mercy, it shall be legal

and shall mean imprisonment for life. When the verdict is guilty with

out a recommendation to mercy it shall be legal and shall mean that

the convicted person shall be sentenced to death. However, when it

is shown that a person convicted of a capital offense without a recom

mendation to mercy had not reached his seventeenth birthday at the

time of the commission of the offense the punishment of such person

shall not be death but shall be imprisonment for life.

2a

Ga. Code Ann., §27-2512

(1953 Rev, vol.)

27-2512. Electrocution substituted for hanging; place of execution.

—All persons who shall be convicted of a capital crime and who shall

have imposed upon them the sentence of death, shall suffer such pun

ishment by electrocution instead of by hanging.

In all cases in which the defendant is sentenced to be electrocuted

it shall be the duty of the trial judge, in passing sentence, to direct

that the defendant be delivered to the Director of Corrections for

electrocution at such penal institution as may be designated by said

Director. However, no executions shall be held at the old prison

farm in Baldwin county. (Acts 1924, pp. 195, 197; Acts 1937-38,

Extra. Sess., p. 330.)

Ga. Grim. Code, §26-2001

" (1970 Rev, vol.)

(effective July 1, 1969)

26-2001. Rape.—A person commits rape when he has carnal knowl

edge of a female, forcibly and against her will. Carnal knowledge in

rape occurs when there is any penetration of the female sex organ by

the male sex organ. A person convicted of rape shall be punished by

death or by imprisonment for life, or by imprisonment for not less

than one nor more than 20 years. No conviction shall be had for

rape on the unsupported testimony of the female.

(Acts 1968, pp. 1249, 1299.)

Ga. Crim. Code, §26-3102

(1970 Rev, vol.)

(effective July 1, 1969)

26-3102. Capital offenses—jury verdict and sentence.-Where, up

on a trial by jury, a person is convicted of an offense which may be

punishable by death, a sentence of death shall not be imposed unless

the jury verdict includes a recommendation that such sentence be

imposed. Where a recommendation of death is made, the court shall

sentence the defendant to death. Where a sentence of death is not

recommended by the jury, the court shall sentence the defendant to

imprisonment as provided by law. Unless the jury trying the case

recommends the death sentence in its verdict, the court shall not

sentence the defendant to death. The provisions of this section shall

3a

not affect a sentence when the case is tried without a jury or when

the judge accepts a plea of guilty.

(Acts 1968, pp. 1249, 1335; 1969, p. 809.)

lb

APPENDIX B

HISTORY OF PUNISHMENT FOR RAPE IN GEORGIA

The Georgia Penal Code of 181 1, which expressly applied

to free white p_ersTfhT75!iry,t6""provided that rape would be

punished hv irnffiTsor^^ labor for not. less ..than

on the same date as the Penal Code, December 16, 1811, in

effect provided that slaves could be sentenced to death for

any crime at the discretion of a tribunal for slaves.3b On

November 23, 1815, the act of 1811 which established a

tribunal for the trial of slaves, was made applicable to all

offenses committed by “free persons of colour.” 4b On

lh“And be it further enacted, That the operation of this law, and

all parts thereof shall be construed to extend to free white persons

only.” Penal Code of 1811, § 67, printed in LAMAR, COMPILATION

OF THE LAWS OF GEORGIA (1821) [hereafter cited as LAMAR],

552.

2b “Be it further enacted, That if any man shall have or take carnal

knowledge of any woman by force, or against her will or consent,

every such person, his aiders or abettors, shall, upon conviction there

of, be sentenced and confined to hard labour, for and during a term

not less than seven years, nor more than sixteen.” Penal Code of

1811, § 60, LAMAR 551.

3bThe Act provided that when a complaint was made to a justice

of the peace of “any crime having been committed by any slave or

slaves” he should summon two other justices to try the case. If it

appeared to the justices that the crime should be punished by death,

a trial before a jury of “ twelve free white persons” was to be held. If

the jury returned a verdict of guilty, “ the court shall immediately

pronounce sentence of death by hanging, or such other punishment

not amounting to death . . . .” Ga. Acts of 1811. No. 503, at 797-

4b“BE it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of

the state of Georgia, in General Assembly met, and it is hereby enacted

by the authority of the same, That an act passed at Milledgeville, on

the 16th day of December, 1811, entitled An act to establish a tribunal

for the trial of salves within this state; the court therein established is

hereby made a tribunal for offences committed by free persons of

colour, to all intents and purposes, as if the words free persons of

colour had been inserted in the caption, and every section of the said

800.

2b

December 18, 1816, the penalty for rape in the Penal Code

applicable to whites was changed to imprisonment for not

/ less than two nor more than twenty years, and a section

was added punishing attempted rape by imprisonment for

not less than one nor more than five years.sb Jh a follow-

ing day, December 19, 1816, an act was passed which

eXpfSSSiy“pfOVitfifed'TtiaTfKeTpunishment of slaves and “free

persons'of colour” for the crime of rape or attempted rape

of a Free white female should be death.6b

A Code of the State of Georgia published in 1861 shows

that sometime between the years 1816 and 1861, the rape

provisions were again amended. Rape by a white person

upon a free white female remained punishable by imprison

ment for no less than two nor more than twenty years; rape

/by a white person upon a slave or free person of color was

1 made punishable “by fine and imprisonment at the discre

tion of the court;” an assault with intent to commit rape

remained punishable by one to five years imprisonment.7b

act to establish a tribunal for the trial of slaves within this state.”

Ga. Acts of 1815, No. 504, LAMAR 800.

sb“Rape shall be punished by imprisonment at hard labour in the

penitentiary, for a term not less than two years, nor longer than

twenty years, as the jury may recommend.

“An attempt to commit rape shall be punished by imprisonment

at hard labour in the penitentiary, for a term not less than one year,

nor longer than five years, as the jury may recommend.” Penal Code

of 1816, §§ 33-34, at LAMAR 571.

6b“BE it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of

the General Assembly of the state of Georgia, and it is hereby enacted

by the authority of the same, That the following shall be considered

as capital offences, when committed by a slave or free person of

colour: . . . committing a rape, or attempting it, on a free white

female; . . . every and each of these offences shall, on conviction, be

punished with death.” Ga. Acts of 1816, No. 508, § 1, at LAMAR 804.

7b“Rape is the carnal knowledge of a female, whether free or slave,

forcibly and against her will.

“Rape on a free white female shall be punished by an imprison

ment at labor in the penitentiary for a term not less than two years

nor longer than twenty years. If committed upon a slave, or free

3b

Rape upon a free white female by a slave or free person of

color remained punishable by death.8*5 However, attempted

rape upon a free white female was made punishable by

death “or such other punishment as the court may prescribe,

proportionate to the offence and calculated to prevent the

occurrence of like offences in future.” 9*5

The Georgia Constitution of 1865, enacted November 8,

1865, abolished slavery. On March 20, 1866, the rape pro

vision of the Penal Code applicable to whites10*5 was amended.

The crime of rape was reduced below a felony and made

pufusKablSTiy THTriFriofTo"exceeH^one thousand Hollars,

imprisonment not to exceed six months, whipping not to

dkceecl thirty-nine lashes, to work in a chain gang on the

public works not to exceed twelve months, and any one or

more of these punishments . . . in the discretion of the

Judge.” 11,5 This amended provision was repealed on Decem-

person of color, by fine and imprisonment, at the discretion of the

court.

“An assault with intent to commit a rape, shall be punished by an

imprisonment at labor in the penitentiary for a term not less than one

year nor longer than five years.” Penal Code §§4248-4250, printed

in CLARK, COBB & IRWIN, CODE OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA

(1861), 824.

8b“The following offences, when committed by a slave or free per

son of color, shall be punished, on conviction, with death, viz: . .. rape

upon a free white female.” Penal Code for Slaves and Free Persons of

Color, §4704, printed in id. at 918.

9b“The following offences, when commited by a slave or free person

of color, shall be punished in the discretion of the court, either by

death or such other punishment as the court may prescribe, propor- ...

donate to the offence and calculated to prevent the occurrence of

like offences in future, viz: Attempt to commit a rape upon a free

white female. . . .” Penal Code for Slaves and Free Persons of Color,

§4708, in id. at 918.

10b§4248. See note 7b supra.

llb“The General Assembly of the State of Georgia do enact, That

from and after the passage of this Act the crimes defined in the fol

lowing Sections of the Penal Code as felonies, and punishable by

imprisonment in the Penitentiary, shall henceforth be reduced below

felonies, and punished in the manner hereinafter set forth, viz: Sec

tions . . .4248 . . . .

[footnote continued]

4b

ber 11, 1866, and the prior provisions of the code relating

to punishment were reinstated.12b

On December 15, 1866, a new rape statute was enacted

which made rape punishable by death or by imprisonment

for no less than one nor more than twenty years at the dis

cretion of the jury, and which made assault with intent to

commit a rape punishable by imprisonment for no less than

one nor more than twenty years.13b

“ 5. SEC. II. That all other crimes designated in the Penal

Code punishable by fine and imprisonment, or either, shall be likewise

punishable in the manner hereinafter set forth, that is to say, the

punishment for any of the aforesaid crimes, hereafter committed, shall

be a fine not to exceed one thousand dollars, imprisonment not to

exceed six months, whipping not to exceed thirty-nine lashes, to work

in a chain gang on the public works not to exceed twelve months,

and any one or more of these punishments may be ordered in the dis

cretion of the Judge.” Ga. Acts 1866, No. 236, p. 233.

12b “SECTION I. Be it enacted, etc., That from and after the pass

age of this act, so much of the first section of an act entitled an act

to alter and amend the Penal Code of Georgia, passed March 12th,

1866, as relates to section 4248 of the Code of Georgia, be and the

same is hereby repealed, and that said section 4248 be of force as

before the passage of said act.

“ SEC. II. Repeals conflicting laws.” Ga. Acts 1866, No. 209,

P- 151.

13b“SECTION I. Be it enacted, etc., That from and immediately

after the passage of this act, the crime of rape, in this State, shall be

punished with death, unless the defendant is recommended to mercy

by the jury, in which case the punishment shall be the same as for an

assault with intent to commit a rape. An assault with intent to com

mit a rape, in this State, shall be punished by an imprisonment at hard

labor in the Penitentiary of this State, for a term not less than one

nor longer than twenty years.

“SEC. II. Repeals conflicting laws.” Ga. Acts 1866, No. 210.

p. 151.

As codified in the Code of 1933, the penalty provision reads:

“The crime of rape shall be punished with death, unless the defend

ant is recommended to mercy by the jury, in which case the punish

ment shall be for not less than one nor more than 20 years.” Ga.

Code Ann., §26-1302 (1953).

5b

The legislative history of the act passed on December 15,

1866, is not especially instructive. The bill as it was first

read in the Georgia House of Representatives provided that

all rape shall be punished with death.14b Prior to the third

reading in the House, the provision for the alternative pun

ishment of imprisonment was written into the bill, and the

bill was passed the House with this amendment on Novem

ber 26, 1866.1Sb The bill then passed the Senate without

further amendment. The Journals of both the Georgia House

of Representatives and the Georgia Senate reveal that the

Georgia legislature was not engaged in a comprehensive

reform of the Georgia penal law, but passed this bill con

cerning rape at a time when it was considering a variety of

unrelated subjects.16b

In 1960, the penalty for rape was amended to add the

alternative of life imprisonment to the already existing

14b“Sect. 1st. The General Assembly of Georgia do enact, That

from and immediately after the passage of this act, the crime of Rape

in this State shall be punished with death. An assault with intent to

commit a Rape in this State shall be punished by an imprisonment at

hard labor in the Penitentiary of this State for a term not less than

one nor longer than twenty years.

“Sect. 2d. And be it further enacted that all laws and parts of

laws militating against this Act be and the same are thereby repealed.”

Humphries of Lincoln, A Bill to be entitled An Act to alter and

change the 4249th and 4250th paragraphs of the Code of Georgia, in

custody of Georgia State Archives, Atlanta, Georgia.

15b“ . . . unless the defendant is recommended to mercy by the jury

in which case the punishment shall be the same as for an assault with

intent to commit a rape.” Ibid.

16bSee, Journal of the Senate of the State of Georgia (1866); Jour

nal of the House of Representatives of the State of Georgia, Com

menced November 1, 1866 (1866).

6b

choices.1713 In the comprehensive revision of the penal code

in 1968, the language was revised, but not its effect.186

“The crime of rape shall be punished by death, unless the jury

recommends mercy, in which event punishment shall be imprisonment

for life: Provided, however, the jury in all cases may fix the punish

ment by imprisonment and labor in the penitentiary for not less than

one year nor more than 20 years.” Ga. Acts 1960. No. 587, p. 266;

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1302 (Supp. 1970).

186 ‘A person convicted of rape shall be punished by death or by

imprisonment for life, or by imprisonment for not less than one nor

more than 20 years.” Ga. Acts 1968, pp. 1249, 1299; Ga. Code Ann.

§26-2001 (1970 Revision) (effective July 1, 1969).